Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

The Economics of Magazine Publishing

Enviado por

federicosanchezDescrição original:

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

The Economics of Magazine Publishing

Enviado por

federicosanchezDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

The economics of magazine publishing John Klingel The economics of magazine A simplified approach to magazine economics in general can

help you see how relationships exist within and affect individual publications When I was in the book club business, one of my primary professional mentors told me the secret of success. To be successful at running a business, you must know two things: the economics of your product and the economics of the methods of marketing your product. When I first started working for magazines, I tried to use this advice. I had a good understanding of direct mail economics from my experiences with book clubs and continuity offers. I also had a strong background in financial analysis, having majored in accounting and economics in college and having worked in controllers' departments at McGraw-Hill and Xerox. But, even with this background, I had an extremely difficult time understanding magazine economics. Magazine economics are extremely complex. (Actually, I should say publication economics, because I mean to include newsletters, newspapers and other publications.) In fact, I don't know of any business that has more complex economics. What follows is an attempt to simplify these complex economics, to make them easier to understand, and perhaps to give you a different perspective on the world of publishing. I believe that if you can simplify and make general observations, it becomes easier to see how these complex economic relationships exist within individual publications. The major difference between publications and most other products is that there are two major streams of revenue: revenue from sales of the product and advertising revenue. Most products have only one revenue stream--from sales of the product. The economic formula can be stated as follows: Profit (or loss) from circulation plus advertising profit equals total profit (or loss). (Not all publications have two streams of revenue, of course. Controlled circulation publications rely solely on advertising income. Newsletters rely solely on subscription revenue. Most magazines, however, are a mixture of the two.) Every publication tends to have an economic formula that is slightly different or, in some cases, extremely different from that of other publications. Publishers of magazines that are primarily supported by ad profits tend to give away their publications or charge very little for them. In these types of situations, circulation can lose money, and the overall magazine can still be profitable--and in the case of many controlled publications, extremely profitable. The marginal profit on advertising is very high, whereas the marginal profit from the publishing product is extremely low. For every additional dollar of advertising, there are relatively low direct or incremental costs. Ad commissions might be 15percent, and there

are additional printing and postage costs, and perhaps some editorial costs if a constant ad: edit ratio is being maintained. But, in general, the incremental costs of advertising are extremely low. If ad costs average 20 percent of revenue for a publication, the mark-up could be described as 500 percent. Contrast that mark-up to subscription sales where a $12 subscription might carry printing, postage and fulfillment costs of $8. Here we have a 50 percent mark-up--and for many publications, that's a lot. I'm familiar with publications that charge$12 and have service costs of $18, and a publication that charges $27 and costs $23 to fulfill. In publishing, we don't usually think in terms of mark-up, but I think it's an interesting way to demonstrate some of the economic factors involved. When I was in the direct mail product world, we had a rule of thumb that in order to make money, you had to have a three to one ratio of price to cost; for a low priced product ($20 or under), the ratio had to be five to one. In a book club I worked with, we printed books in high volume for $.20 and sold them for $2. That's how you make money in direct mail. Magazines are certainly not the only product with two or multiple streams of revenue--after all, many products have by-products and other sources of revenue. But in magazine economics, the two streams of revenue tend to fight each other. In other words, you can't have your cake and eat it too. As I shall show later, a magazine that can sell additional ad volume by increasing circulation will gain increased ad profit, while circulation profit will normally decline. The incremental ad profit tends to be greater than the incremental circulation loss, so a magazine tends to maximize profit through circulation growth. But there are limits, as we shall see.

1.

Advertising economics

Advertising economics may seem fairly simple at first glance, but that's because most publications tend to consider advertising economics only in terms of their own publication and not in terms of the industry in total. Thinking of the industry as a whole, we can say that, in general, advertising is characterized by extremely high competition. We compete not only with other publications, but also with all other channels of marketing--including personal sales, telephone, TV, radio, direct mail, catalogs, point-of-purchase, newspapers, the yellow pages and other directories. Two basic factors affect ad prices: the CPM factor and the out-of-pocket factor. In the classic "Madison Avenue" world, advertising sales are theoretically based on the relative cost to reach a target audience. If the target audience is upscale managerial and professional males, for example, advertisers can compare the audience profiles for Business Week, Fortune, Forbes, Inc., Venture, Personal Computing Illustrated, Time, Newsweek,

Scientific American, Discover, and a great many other magazines, and then compare the different costs of reaching a thousand people in the target market. In this type of situation, a magazine must be priced competitively with others that offer similar audience profiles. But, if CPM remains fixed for competitive purposes, a magazine can increase profit by increasing circulation as shown in Illustration 1. In some ad markets, the scenario shown in Illustration 1 might work. However, as circulation increases, there are downward pressures on CPM because of competition from other media (TV, radio, newspapers), the out-of-pocket factor, and audience deterioration. As magazines go beyond the 1.0 million mark, the audience profile tends to become less defined, more mass market, and more competitive with other mass market media such as TV. The out-of-pocket factor also comes into play, to some extent, because paying $100,000 or more for a page of advertising is going to make even the big spenders think twice. So, in a narrow range of circulation growth, CPM can probably be held constant as total price is increased. But if there are large increases in circulation, CPM will probably be forced down. The price curve looks something like that shown in Illustration 2.

2.

Circulation

In some markets, CPM is irrelevant and the out-of-pocket is totally dominant. Take, for example, a magazine with 50,000 circulation, no other publications competing in the market, a CPM of $50 and an extremely unsophisticated ad market. The out-of-pocket cost for an ad page is $2,500. In such an unsophisticated market, advertisers don't know how to calculate CPM and don't even relate to the concept. Instead, they budget X number of dollars for advertising. If our hypothetical magazine increases circulation, it will continue to receive the same amount of ad dollars and can price itself out of the ad market if it raises price too much. Only once have I encountered a pure out-of-pocket market. In most cases, ad price sensitivity is a result of both the CPM factor and the out-of-pocket factor. In any given ad market, it is important to try to identify the extent to which the two factors operate. One of the best economic formulas for a magazine is to hold circulation constant and steadily increase the CPM. In a market where the out-of-pocket factor is relatively strong, rapid and dramatic growth usually forces us to lower the CPM. Again, what I've described here is a simplified analysis in order to clarify an understanding of the complexities in the advertising market.

3.

Circulation economics

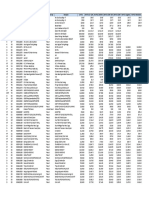

It is primarily circulation economics that make publishing economics so complex, and there are two primary reasons why: 1. Profitability occurs over time, and 2. there are many ways to reach the market. Most products that are sold via direct response share the same economics. They lose money on the initial order and make money on repeat or follow-up sales. Catalogs lose money on the first sale and make money on sales to their house list of known buyers; book clubs can lose money on people who buy one to three books and make all their profit from a small percentage of people who buy five or more books. (There's an old observation in direct marketing that 80 percent of the profits come from 20 percent of the customers.) With magazines, we tend to lose money on sub acquisition and make money on renewals. A direct mail campaign to cold names might net 2 percent response and a cost of $20 a sub, whereas a renewal direct mail campaign (more than one effort) might garner a 50 percent response at a cost of $2 a sub. This means that to calculate profit or loss on subscription sales, we have to measure income and costs over a number of years. The technique of measuring profitability over time is called source evaluation, and the period of time is usually five or six years. There are many different ways to reach our markets, although some publications can't use all of the available marketing channels. There are insert cards, direct mail, Christmas gifts, newsstand, various types of agents, and so on. The acquisition costs of various sources are different--some sources are very expensive and some are not. All sources have some limit on the volume of subs that can be obtained. Using source evaluation, the sources for a magazine can be analyzed to determine the volume available and the cost of obtaining subs from that source. If a magazine grows, it must turn to increasingly more expensive and less profitable sources. Profit per subscriber will also decrease because of market saturation. As market penetration increases, additional or incremental costs to acquire subscribers will increase. Illustration 3 shows the sources for a hypothetical Magazine X. Each source has been analyzed over five years, taking into account the different economic factors for each source (acquisition costs, bad debt and renewal rates). The sources have then been ranked from least expensive to most expensive. (The assumptions used for this analysis and further explanation of the techniques used to rank the sources can be found in the July 1981 issue of FOLIO:.) If a magazine carried no advertising, it would use the first four sources, as they are the only profitable sources over five years. The magazine would have a very small circulation, simply because there wouldn't be any more sources that could be used economically. A

magazine that produced advertising profit of $5 per net paid unit could afford to buy sources down to paid space, and a magazine with an ad profit over $19 per net paid unit could afford to use all the sources. In the absence of advertising, a magazine would maximize profit by acquiring every subscriber that was profitable overtime. Sources that lost money in the first year would be acquired if, over a period of time, the profits from renewals more than offset the first year loss. Without advertising, a magazine would tend to be very small because, for most magazines, very few sources make money on subscription income alone. What confuses the situation in actual practice is that most magazines don't assign product costs when they analyze circulation profit. Often, I have heard circulation people claim that all their sources are profitable. When you don't assign a cost of goods sold to a product's revenue stream, it's relatively easy to make the source look profitable. Another extremely important economic factor is that subscribers, like unsophisticated advertisers, tend to buy total price--not price per copy. If a direct mail piece describing a monthly magazine for $12 is tested against an identical direct mail piece for a bi-monthly (6x) frequency at $12, the response will be almost identical. The consumer tends to react to total price ($12) and doesn't calculate that the per copy price is $1 versus $2. This phenomenon has been tested innumerous situations and appears to be an almost universal fact of life in subscription marketing. In addition to the above, there doesn't appear to be any significant difference in the renewal rates of monthlies and bimonthlies. Hence, the higher production cost incurred with frequency increases has to be entirely supported by increases in ad sales. The subscriber won't pay for the extra issues. This may be frustrating for publishers and editors of bimonthlies, but it is a fact of publishing life. Subscription volume is typically very price sensitive. There are a few publications that have relatively low price sensitivity, but the more normal or common price elasticity is unitary. A 10 percent increase in price will result in a 10 percent decline in volume. Another way of stating this is that revenue at all prices remains relatively constant. The value of raising price is that there will be fewer copies to print and more profit from lower costs. Without advertising considerations, a magazine attempting to maximize profit would use relatively few sources, be high-priced, have low frequency, and spend very little on the product (i.e., low numbers of pages, inexpensive paper, no four-color). Not only does this describe the economic formula that is usually called for when there's no advertising, it describes the economics of newsletters. To me a newsletter is just a magazine with a different economic formula (high price, low volume, low cost of printing and no ad income). To maximize long-term subscription profit, a magazine should acquire every subscriber or utilize any source where the subscription revenue over time (five to six years) is greater

than the incremental or additional costs that are incurred in acquiring, renewing and servicing the subscriber over time. Illustration 4 is a six-year P & L for a direct mail campaign pulling 3.5 percent response. In this case, the source being analyzed makes a profit after Year Two, but the profits in Years Three through Six are not enough to offset the losses in Years One and Two. In the absence of advertising, there would be no reason to acquire subs from this source because the initial investment in sub acquisition would not be recovered in the foreseeable future. In economic terms, the incremental cost per additional subscriber increases as circulation grows. At some point, the additional costs of acquiring subs will equal the incremental or additional revenue. Beyond that point, each additional sub that's acquired reduces profit. The circulation level that maximizes circulation profit is the point where incremental revenue equals incremental cost. It is difficult to find the point where the circulation level maximizes profit because profitability occurs over time. But through testing and good data from our fulfillment companies, we can come very close to finding the optimum circulation level using source evaluation and computer modeling. Note how circulation economics that tend to lead to low circulation and low frequency are in opposition to advertising economics, which usually call for high circ and high frequency. A magazine can easily find itself in a position where it pays to acquire circulation that has incremental costs that exceed the incremental subscription revenue and loses money. If the incremental revenue from advertising exceeds the incremental costs of growth (the net loss associated with the additional subs), overall magazine profits will be increased. In other words, we can trade off circulation profits for advertising profits. Many large consumer magazines have pushed and stretched their rate bases to maximize ad profits. In the short run, this strategy has paid off handsomely for many publications. But for long-term stability, this strategy was very dangerous. When ad sales decline, these publications usually can't improve circulation economics by raising price, or their rate base will drop. Unfortunately, the best time to lower rate bases is in a strong ad market. Another bad strategy has been the tendency to push rate bases and raise subscription prices. What happens in this situation is that the best sources (newsstand sales, direct mail, inserts and renewals) decline in volume because of normal price elasticity. To maintain rate base, circulation people turn to short-term subscriptions or agents or sweepstakes or some other solution. Usually these short-term solutions lead to declining demographics, lower audience quality and an increase in future circulation costs. Like most American businesses, publishing tends to pay lip service to long-term planning and then make short-term decisions.

In general, most people who run publishing companies don't have a very good understanding of magazine economics, particularly circulation economics. The most common road to the top is through advertising sales. And if a magazine's major source of profit is advertising, it makes sense to promote the ad people. However, this tends to leave top management weak in knowledge of circulation economics, and hence weak in knowledge of how to find the best mix of advertising and circulation economics. It's important for a magazine to define its economic formula. Circulation pricing, the choice of which sources to use, and many other matters hinge on the overall economics of the publication. If a magazine can't sell much advertising and must live off circ income, it may find that it shouldn't use some sources. Putting copies on airlines is a marketing strategy that only applies to magazines that are rate-base or advertising-income-oriented. A ratebase publication often finds that lower sub prices are more profitable because higher circulation and hence more ad dollars can be obtained. Certain agent sources might make greater economic sense to a rate-base-oriented magazine than to a magazine that doesn't carry very much advertising. Finding the circulation level that maximizes profit is extremely difficult. The complexity stems from the fact that there are so many variables to juggle. In addition to the variables affecting circulation and advertising, we have printing economics and other variables that affect product quality. The primary tool we use to search for the elusive point of maximum profit and to get a "handle" on our magazine's economics is the computer model. A secondary tool that also helps us learn more about a publication's economics is the source evaluator. Most publishers should be familiar with these tools and know how to use them. If you want to maximize your publication's profits, you have to have a solid knowledge of your publication's economics.

4.

The economics of controlled circulation

Where most consumer publications use size of audience as a major ad selling tool, trade magazines typically sell audience quality. Often, their economic formula is to obtain a very specific audience that represents a high value to the advertiser (i.e., the 20 percent of a market that spends 80 percent of the dollars in the market) and then charge a high CPM. The ad CPM for most trade magazines is above $50, compared to under $20 for most large consumer magazines. If a magazine is trying to obtain a very specific demographic profile, paid circulation is difficult to use. A paid magazine has little control over who pays for a subscription--hence it is harder to control the demographics. In addition, a trade magazine often seeks a very

high market penetration of a total market or high penetration of specific demographic units within a market. A paid circulation magazine cannot, in most circumstances, obtain more than a 20 percent market penetration--and in almost all cases cannot exceed 40 percent. If the goal needed to sell advertising is 80 percent of a market, paid circ is not going to obtain the necessary circulation. The other factor in trade markets is the limited number of sources available to sell subs. In most trade markets, there are only a few direct mail lists. What few are available are typically low response compiled lists. Trade magazines usually can't rent other magazine lists or trade with competitors. They don't have agent sources like PCH, and newsstand distribution is usually out of the question. If a trade magazine wants paid circ, it typically has to use a small universe with low response and mail the same people repeatedly. What this translates to in most cases is extremely high acquisition costs: Acquisition costs are so high that it is less costly to give the magazine away than to charge for it. This is also true for many consumer magazines. As a general rule, however, consumer publications can't sell the concept of controlled circulation to their advertisers. For most trade publications, the CPM factor is relatively unimportant; out-of-pocket dollars is the prime factor. Trade advertisers are often selling very expensive products, and their ad budgets are typically low relative to sales. In many trade markets, magazines have virtual monopolies, or at worst they are oligarchies and all the competitors maintain high CPMs. I've had the unfortunate experience to work on a trade publication in a three-book field when the lead book kept its CPM very low. But in general, trade publication economics rely on high ad prices, low circulation and highly controlled editorial and production costs. In the absence of competition, a trade magazine has no incentive to raise circulation and will produce just enough readers to sell advertising. Circulation marketing goals in the trade magazine field are primarily oriented toward audience quality--as opposed to the primary goal of consumer magazines, which is to produce numbers. The ad sales strategy of a trade publication is also oriented toward quality and how ads will reach primary decision makers. As a general observation, trade magazine ad people tend to sell "smarter," know their audience in more detail, and are better trained than consumer ad salespeople. COPYRIGHT 1988 Copyright by Media Central Inc., A PRIMEDIA Company. All rights reserved. COPYRIGHT 2008 Gale, Cengage Learning

Você também pode gostar

- 9155fxa 1010Documento8 páginas9155fxa 1010federicosanchezAinda não há avaliações

- Eaton 9135 Ups PDFDocumento4 páginasEaton 9135 Ups PDFfedericosanchezAinda não há avaliações

- Eaton Powerware 9395 225 1000 Kva PDFDocumento12 páginasEaton Powerware 9395 225 1000 Kva PDFfedericosanchezAinda não há avaliações

- Eaton Powerware Blade UpsDocumento2 páginasEaton Powerware Blade UpsfedericosanchezAinda não há avaliações

- Eaton Powerware 9646 BladeDocumento2 páginasEaton Powerware 9646 BladefedericosanchezAinda não há avaliações

- Eaton 9390Documento12 páginasEaton 9390andreisraelAinda não há avaliações

- Eaton Powerware 5115Documento4 páginasEaton Powerware 5115federicosanchezAinda não há avaliações

- Eaton 9PHD Heavy Duty UPSDocumento2 páginasEaton 9PHD Heavy Duty UPSGilQuintanaAinda não há avaliações

- Delta Ultron H Series 15 30 KvaDocumento2 páginasDelta Ultron H Series 15 30 Kvafedericosanchez0% (1)

- UpsDocumento2 páginasUpsOae FlorinAinda não há avaliações

- Delta Amplon Gaia Series 5 11 KvaDocumento2 páginasDelta Amplon Gaia Series 5 11 KvafedericosanchezAinda não há avaliações

- 9130 Datasheet Rev D Low PDFDocumento2 páginas9130 Datasheet Rev D Low PDFRonald Victor Galarza HermitañoAinda não há avaliações

- Chloride Power Lan Green 5 7 KvaDocumento2 páginasChloride Power Lan Green 5 7 Kvafedericosanchez50% (2)

- Bicker Iups 301 eDocumento1 páginaBicker Iups 301 efedericosanchezAinda não há avaliações

- Aros FlexusDocumento8 páginasAros FlexusfedericosanchezAinda não há avaliações

- Delta Modulon NH Plus Series 20 120 KvaDocumento2 páginasDelta Modulon NH Plus Series 20 120 KvafedericosanchezAinda não há avaliações

- Delta Modulon NH Series 20 80 KvaDocumento2 páginasDelta Modulon NH Series 20 80 KvafedericosanchezAinda não há avaliações

- Aros ST Sentry MultistandardDocumento6 páginasAros ST Sentry MultistandardfedericosanchezAinda não há avaliações

- Bently Nevada 3500 15Documento6 páginasBently Nevada 3500 15federicosanchezAinda não há avaliações

- Puls Sl5300Documento2 páginasPuls Sl5300federicosanchezAinda não há avaliações

- Liebert: Performance Power Protection For PC's and Offi Ce EquipmentDocumento2 páginasLiebert: Performance Power Protection For PC's and Offi Ce EquipmentfedericosanchezAinda não há avaliações

- Quick Guide IEC V2 27 02 14Documento3 páginasQuick Guide IEC V2 27 02 14federicosanchezAinda não há avaliações

- Riello Multi Sentry MCT MST PDFDocumento6 páginasRiello Multi Sentry MCT MST PDFfedericosanchezAinda não há avaliações

- Pyramid DSP Series: TESID Innovation and Creativity Reward 2005Documento2 páginasPyramid DSP Series: TESID Innovation and Creativity Reward 2005federicosanchezAinda não há avaliações

- 9130 Datasheet Rev D Low PDFDocumento2 páginas9130 Datasheet Rev D Low PDFRonald Victor Galarza HermitañoAinda não há avaliações

- Riello Sentinel Power SPT SPWDocumento4 páginasRiello Sentinel Power SPT SPWfedericosanchezAinda não há avaliações

- Sola Hevi Duty Sdu 500Documento2 páginasSola Hevi Duty Sdu 500federicosanchezAinda não há avaliações

- Apc 989001088261 1260021862PL - PhilipsHealthcareDocumento1.173 páginasApc 989001088261 1260021862PL - PhilipsHealthcarefedericosanchezAinda não há avaliações

- Uninterruptible Power Systems: SDU Series, Direct Current Uninterruptible Power Supply (DC UPS) SystemDocumento4 páginasUninterruptible Power Systems: SDU Series, Direct Current Uninterruptible Power Supply (DC UPS) SystemfedericosanchezAinda não há avaliações

- Highly Reliable Protection For IT and Critical Industrial ApplicationsDocumento4 páginasHighly Reliable Protection For IT and Critical Industrial ApplicationsfedericosanchezAinda não há avaliações

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (895)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5794)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (266)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (400)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (345)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2259)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (121)

- Asher - Bacteria, Inc.Documento48 páginasAsher - Bacteria, Inc.Iyemhetep100% (1)

- Basa BasaDocumento4 páginasBasa Basamarilou sorianoAinda não há avaliações

- Primer Viaje en Torno Del Globo Written by Antonio Pigafetta. It Was Originally Published in The Year of 1536Documento2 páginasPrimer Viaje en Torno Del Globo Written by Antonio Pigafetta. It Was Originally Published in The Year of 1536Bean BeanAinda não há avaliações

- Educational Metamorphosis Journal Vol 2 No 1Documento150 páginasEducational Metamorphosis Journal Vol 2 No 1Nau RichoAinda não há avaliações

- Photosynthesis 9700 CieDocumento8 páginasPhotosynthesis 9700 CietrinhcloverAinda não há avaliações

- 11 Chemistry NcertSolutions Chapter 2 ExercisesDocumento54 páginas11 Chemistry NcertSolutions Chapter 2 ExercisesGeeteshGuptaAinda não há avaliações

- Reflection (The We Entrepreneur)Documento2 páginasReflection (The We Entrepreneur)Marklein DumangengAinda não há avaliações

- Oscar Characterization TemplateDocumento3 páginasOscar Characterization Templatemqs786Ainda não há avaliações

- Grenade FINAL (Esl Song Activities)Documento4 páginasGrenade FINAL (Esl Song Activities)Ti LeeAinda não há avaliações

- Case StudyDocumento3 páginasCase StudyAnqi Liu50% (2)

- F07 hw07Documento2 páginasF07 hw07rahulAinda não há avaliações

- Sample Opposition To Motion To Alter or Amend Judgment in United States District CourtDocumento3 páginasSample Opposition To Motion To Alter or Amend Judgment in United States District CourtStan BurmanAinda não há avaliações

- Monograph SeismicSafetyDocumento63 páginasMonograph SeismicSafetyAlket DhamiAinda não há avaliações

- Canine HyperlipidaemiaDocumento11 páginasCanine Hyperlipidaemiaheidy acostaAinda não há avaliações

- Journal of Cleaner Production: Kamalakanta Muduli, Kannan Govindan, Akhilesh Barve, Yong GengDocumento10 páginasJournal of Cleaner Production: Kamalakanta Muduli, Kannan Govindan, Akhilesh Barve, Yong GengAnass CHERRAFIAinda não há avaliações

- Sally Mann Hold Still - A Memoir With Photographs (PDFDrive)Documento470 páginasSally Mann Hold Still - A Memoir With Photographs (PDFDrive)danitawea100% (1)

- Natural Language Processing Projects: Build Next-Generation NLP Applications Using AI TechniquesDocumento327 páginasNatural Language Processing Projects: Build Next-Generation NLP Applications Using AI TechniquesAnna BananaAinda não há avaliações

- Adult Consensual SpankingDocumento21 páginasAdult Consensual Spankingswl156% (9)

- Sample Marketing Plan HondaDocumento14 páginasSample Marketing Plan HondaSaqib AliAinda não há avaliações

- Computer Literacy Skills and Self-Efficacy Among Grade-12 - Computer System Servicing (CSS) StudentsDocumento25 páginasComputer Literacy Skills and Self-Efficacy Among Grade-12 - Computer System Servicing (CSS) StudentsNiwre Gumangan AguiwasAinda não há avaliações

- Sandra Lippert Law Definitions and CodificationDocumento14 páginasSandra Lippert Law Definitions and CodificationЛукас МаноянAinda não há avaliações

- Reimprinting: ©michael Carroll NLP AcademyDocumento7 páginasReimprinting: ©michael Carroll NLP AcademyJonathanAinda não há avaliações

- Lee Gwan Cheung Resume WeeblyDocumento1 páginaLee Gwan Cheung Resume Weeblyapi-445443446Ainda não há avaliações

- Heart Rate Variability - Wikipedia PDFDocumento30 páginasHeart Rate Variability - Wikipedia PDFLevon HovhannisyanAinda não há avaliações

- Capital Structure: Meaning and Theories Presented by Namrata Deb 1 PGDBMDocumento20 páginasCapital Structure: Meaning and Theories Presented by Namrata Deb 1 PGDBMDhiraj SharmaAinda não há avaliações

- Dispeller of Obstacles PDFDocumento276 páginasDispeller of Obstacles PDFLie Christin Wijaya100% (4)

- Position Paper Guns Dont Kill People Final DraftDocumento6 páginasPosition Paper Guns Dont Kill People Final Draftapi-273319954Ainda não há avaliações

- Avatar Legends The Roleplaying Game 1 12Documento12 páginasAvatar Legends The Roleplaying Game 1 12azeaze0% (1)

- Top Websites Ranking - Most Visited Websites in May 2023 - SimilarwebDocumento3 páginasTop Websites Ranking - Most Visited Websites in May 2023 - SimilarwebmullahAinda não há avaliações

- δ (n) = u (n) - u (n-3) = 1 ,n=0Documento37 páginasδ (n) = u (n) - u (n-3) = 1 ,n=0roberttheivadasAinda não há avaliações