Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Cadences

Enviado por

PeterAndrews0 notas0% acharam este documento útil (0 voto)

225 visualizações9 páginascadences

Título original

cadences

Direitos autorais

© © All Rights Reserved

Formatos disponíveis

TXT, PDF, TXT ou leia online no Scribd

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentocadences

Direitos autorais:

© All Rights Reserved

Formatos disponíveis

Baixe no formato TXT, PDF, TXT ou leia online no Scribd

0 notas0% acharam este documento útil (0 voto)

225 visualizações9 páginasCadences

Enviado por

PeterAndrewscadences

Direitos autorais:

© All Rights Reserved

Formatos disponíveis

Baixe no formato TXT, PDF, TXT ou leia online no Scribd

Você está na página 1de 9

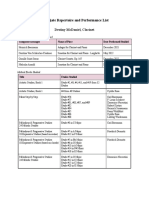

Cadence (music)

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Perfect authentic cadence (V-I with roots in the bass and tonic in the highest v

oice of the final chord): ii-V-I progression in C, four-part harmony (Benward &

Saker 2003, p.90.). About this sound Play (helpinfo)

In Western musical theory, a cadence (Latin cadentia, "a falling") is, "a melodi

c or harmonic configuration that creates a sense of repose or resolution [finali

ty or pause]."[1] A harmonic cadence is a progression of (at least) two chords t

hat concludes a phrase, section, or piece of music.[2] A rhythmic cadence is a c

haracteristic rhythmic pattern that indicates the end of a phrase.[3] Cadences g

ive phrases a distinctive ending that can, for example, indicate whether the pie

ce is to continue or has concluded. An analogy may be made with punctuation.[4]

Weaker cadences act as "commas" that indicate a pause or momentary rest, while a

stronger cadence acts as a "period" that signals the end of the phrase or sente

nce. A cadence is labeled more or less "weak" or "strong" depending on its sense

of finality. While cadences are usually classified by specific chord or melodic

progressions, the use of such progressions does not necessarily constitute a ca

dencethere must be a sense of closure, as at the end of a phrase. Harmonic rhythm

plays an important part in determining where a cadence occurs.

Cadences are strong indicators of the tonic or central pitch of a passage or pie

ce.[1] Edward Lowinsky thought that the cadence was the "cradle of tonality."[5]

Contents

1 Classification of cadences in common practice tonality with examples

1.1 Authentic cadence

1.2 Half cadence

1.3 Plagal cadence

1.4 Interrupted (or Deceptive) cadence

1.5 Inverted cadence

1.6 Upper leading-tone cadence

1.7 Rhythmic classifications

2 Cadences in medieval and Renaissance polyphony

3 Classical cadential trill

4 Jazz

5 Popular music

6 Rhythmic cadence

7 See also

8 References

Classification of cadences in common practice tonality with examples

PAC (VI progression in C About this sound Play (helpinfo))

IAC (VI progression in C About this sound Play (helpinfo))

Evaded cadence (VV42I6 progression in C About this sound Play (helpinfo))

In music of the common practice period, cadences are divided into four types acc

ording to their harmonic progression: authentic, plagal, half, and deceptive. Ty

pically, phrases end on authentic or half cadences, and the terms plagal and dec

eptive refer to motion that avoids or follows a phrase-ending cadence. Each cade

nce can be described using the Roman numeral system of naming chords:

Authentic cadence

Authentic (also closed, standard or perfect) cadence: V to I (or VI). A seven

th above the root is often added to create V7. The The Harvard Concise Dictionar

y of Music and Musicians says, "This cadence is a microcosm of the tonal system,

and is the most direct means of establishing a pitch as tonic. It is virtually

obligatory as the final structural cadence of a tonal work."[1] The phrase perfe

ct cadence is sometimes used as a synonym for authentic cadence, but can also ha

ve a more precise meaning depending on the chord voicing:

Beethoven Piano Sonata, Op. 13 perfect authentic cadence.[6] About this soun

d Play (helpinfo)

Perfect authentic cadence (PAC): The chords are in root position; that i

s, the roots of both chords are in the bass, and the tonic (the same pitch as ro

ot of the final chord) is in the highest voice of the final chord. A PAC is a pr

ogression from V to I in major keys, and V to i in minor keys. This is generally

the strongest type of cadence and often found at structurally defining moments.

[7] "This strong cadence achieves complete harmonic and melodic closure."[8]

Imperfect authentic cadence (IAC), best divided into three separate cate

gories:

1. Root position IAC: similar to a PAC, but the highest voice is not

the tonic ("do" or the root of the tonic chord).

2. Inverted IAC: similar to a PAC, but one or both chords is inverte

d.

3. Leading tone IAC: the V chord is replaced with the viio/subV chor

d (but the cadence still ends on I).

Evaded cadence: V4

2 to I6

.[9] Because the seventh must fall step wise, it forces the cadence to r

esolve to the less stable first inversion chord. Usually to achieve this a root

position V changes to a V4

2 right before resolution, thereby "evading" the cadence.

Half cadence

Half cadence (IV progression in C major About this sound Play (helpinfo))

Phrygian half cadence (iv6iv6V progression in c minor About this sound Play (helpinf

o))

Phrygian cadence (voice-leading) on E[1] About this sound Play (helpinfo)

Lydian cadence (voice-leading) on E[1] About this sound Play (helpinfo))

Burgundian cadence on G[10] About this sound Play (helpinfo))

Phrygian cadence in Bach's Schau Lieber Gott Chorale.[11] About this sound Play

(helpinfo)

Half cadence ("'Imperfect Cadence'" or semicadence): any cadence ending on V

, whether preceded by V of V, ii, vi, IV, or Ior any other chord. Because it soun

ds incomplete or suspended, the half cadence is considered a weak cadence that c

alls for continuation.[12]

Phrygian half-cadence: a half cadence from iv6 to V in minor, so named b

ecause the semitonal motion in the bass (flat sixth degree to fifth degree) rese

mbles the semitone heard in the iiI of the ancient (15th century) cadence in the

Phrygian mode. Due to its being a survival from modal Renaissance harmony this c

adence gives an archaic sound, especially when preceded by v (v-iv6-V).[13] A ch

aracteristic gesture in Baroque music, the Phrygian cadence often concluded a sl

ow movement immediately followed by a faster one.[14] With the addition of motio

n in the upper part to the sixth degree, it becomes the Landini cadence.[1]

Lydian cadence: The Lydian half-cadence is similar to the Phrygian-half,

involving iv6-V in the minor, the difference is that in the Lydian-half, the wh

ole iv6 is raised by 1/2 step in other words, the Phrygian-half begins with the

first chord built on scale degree P4 and the Lydian-half is built on the scale d

egree 4+ (augmented 4th).[citation needed] The Phrygian cadence ends with the mo

vement from iv6 ? V of bass (3rd of the chord/scale degree 6m) down by semi-tone

? bass (the root of the chord/scale degree P5), fifth (scale degree P1) up by w

hole-tone ? fifth (scale degree 2M), and the root (scale degree P4) up by whole-

step ? octave (scale degree P1/P8); the Lydian half-cadence ends with the moveme

nt from a iv6 (raised by half step) ? V of bass (3rd of the chord/scale degree 6

M) down by whole-tone ? bass (the root of the chord/scale degree P5), fifth (sca

le degree 1+) up by half-step ? fifth (scale degree 2M), and the root (scale deg

ree 4+) up by half-step ? octave (scale degree P1/P8).

Burgundian cadences: Became popular in Burgundian music. Note the parall

el fourths between the upper voices.[10]

Plagal cadence

Plagal cadence (IV-I progression in C About this sound Play (helpinfo))

Plagal cadence: IV to I, also known as the "Amen Cadence" because of its fre

quent setting to the text "Amen" in hymns. William Caplin disputes the existence

of plagal cadences in music of the classical era: "An examination of the classi

cal repertory reveals that such a cadence rarely exists. [...] Inasmuch as the p

rogression IV-I cannot confirm a tonality (it lacks any leading-tone resolution)

, it cannot articulate formal closure [...]. Rather, this progression is normall

y part of a tonic prolongation serving a variety of formal functions not, howeve

r a cadential one. Most examples of plagal cadences given in textbooks actually

represent a postcadential codetta function: that is, the IV-I progression follow

s an authentic cadence but does not itself create genuine cadential closure."[15

] It may be noticed that the plagal cadence, "leaves open the possibility of int

erpretation as V-I-V" rather than I-IV-I.[12] The term "minor plagal cadence" is

used to refer to the iv-I progression. Sometimes a combination of major and min

or plagal cadence is used (IV-iv-I); for a progression with similar sonorities,

see backdoor progression.

Interrupted (or Deceptive) cadence

Deceptive cadence (V-vi progression in C About this sound Play (helpinfo)).

Deceptive cadence in Mozart's Sonata in C Major, K. 330, second movement.[12] Ab

out this sound Play (helpinfo)

Interrupted cadence: V to any chord other than I (typically some form of sub

mediant harmony). The most important irregular resolution,[16] most commonly V7-

vi (or V7-bVI) in major or V7-VI in minor.[16][17] This is considered a weak cad

ence because of the "hanging" (suspended) feel it invokes. One of the most famou

s examples is in the coda of the Passacaglia and Fugue in C minor, BWV 582 by Jo

hann Sebastian Bach: Bach repeats a chord sequence ending with V over and over,

leading the listener to expect resolution to Ionly to be thrown off completely wi

th a fermata on a striking, D-flat major chord in first inversion (?IIthe Neapoli

tan chord). After a pregnant pause, the "real" ending commences. At the beginnin

g of the final movement of Gustav Mahler's 9th Symphony, the listener hears a st

ring of many deceptive cadences progressing from V to IV6.

Inverted cadence

An inverted cadence (also called a medial cadence) inverts the last chord. It ma

y be restricted only to the perfect and imperfect cadence, or only to the perfec

t cadence, or it apply to cadences of all types.[18] To distinguish them from th

is form, the other, more common forms of cadences listed above are known as "rad

ical cadences."[19]

Upper leading-tone cadence

Cadence featuring an upper leading tone from a well known 16th-century lamentati

on, the debate over which was documented in Rome c.1540.[20] About this sound Pl

ay upper-leading tone trill (helpinfo) About this sound Play diatonic trill (helpi

nfo)

For example, in the image (right), the final three written notes in the upper vo

ice are B-C-D, in which case a trill on C produces D. However, convention implie

d a C?, and a cadential trill of a whole tone on the second to last note produce

s D?/E?, the upper leading-tone of D?. Presumably the debate was over whether to

use C?-D? or C?-D for the trill.

Rhythmic classifications

Cadences can also be classified by their rhythmic position. A "metrically accent

ed cadence" occurs on a strong position, typically the downbeat of a measure. A

"metrically unaccented cadence" occurs in a metrically weak position, for instan

ce, after a long appoggiatura. Metrically accented cadences are considered stron

ger and are generally of greater structural significance. In the past the terms

"masculine" and "feminine" were sometimes used to describe rhythmically "strong"

or "weak" cadences, but this terminology is no longer acceptable to some.[21] S

usan McClary has written extensively on the gendered terminology of music and mu

sic theory in her book Feminine Endings.[22]

Metrically unaccented cadence (IV64-V7-I progression in C About this sound Play

(helpinfo)). Final chord postponed to fall on a weak beat.[23]

Bar-line shift's effect on metric accent: first two lines vs. second two lines[2

4] About this sound Play (helpinfo).

Likewise, cadences can be classified as either transient (a pause, like a comma

in a sentence, that implies the piece will continue after a brief lift in the vo

ice) or terminal (more conclusive, like a period, that implies the sentence is d

one).[citation needed] Most transient cadences are half cadences (which stop mom

entarily on a dominant chord), though IAC or deceptive cadences are also usually

transient, as well as Phrygian cadences. Terminal cadences are usually PAC or s

ometimes plagal cadences.

Cadences in medieval and Renaissance polyphony

Clausula vera cadence from Lassus's Beatus homo, mm. 3435[25] About this sound Pl

ay (helpinfo)). Note the half step in one voice and the whole step in the other.

Three voice clausula vera from Palestrina's Magnificat Secundi Toni: Deposuit po

tentes, mm. 2728[25] About this sound Play (helpinfo).

Medieval and Renaissance cadences are based upon dyads rather than chords. The f

irst theoretical mention of cadences comes from Guido of Arezzo's description of

the occursus in his Micrologus, where he uses the term to mean where the two li

nes of a two-part polyphonic phrase end in a unison.

A clausula or clausula vera ("true close") is a dyadic or intervallic, rather th

an chordal or harmonic, cadence. In a clausula vera two voices approach an octav

e or unison through stepwise motion.[25] This is also in contrary motion. In thr

ee voices the third voice often adds a falling fifth creating a cadence similar

to the authentic cadence in tonal music.[25]

According to Carl Dahlhaus, "as late as the 13th century the half step was exper

ienced as a problematic interval not easily understood, as the irrational remain

der between the perfect fourth and the ditone:

\textstyle{{{4 \over 3} \over \left ({9 \over 8} \right )^2} = {256 \over 24

3} }\,\![26]

In a melodic half step, listeners of the time perceived no tendency of the lower

tone toward the upper, or the upper toward the lower. The second tone was not t

he 'goal' of the first. Instead, musicians avoided the half step in clausulas be

cause, to their ears, it lacked clarity as an interval. Beginning in the 13th ce

ntury cadences begin to require motion in one voice by half step and the other a

whole step in contrary motion. In the 14th century, an ornamentation of this, w

ith an escape tone, became known as the Landini cadence, after the composer, who

used them prodigiously.

Renaissance plagal cadence About this sound Play (helpinfo)).

Clausula vera for comparison About this sound Play (helpinfo)).

A plagal cadence was found occasionally as an interior cadence, with the lower v

oice in two-part writing moving up a perfect fifth or down a perfect fourth.[27]

A pause in one voice may also be used as a weak interior cadence.[27]

Pause as weak interior cadence from Lassus's Qui vult venire post me, mm. 35 Abou

t this sound Play (helpinfo).

In counterpoint an evaded cadence is one where one of the voices in a suspension

does not resolve as expected, and the voices together resolved to a consonance

other than an octave or unison[28] (a perfect fifth, a sixth, or a third).

Classical cadential trill

In the Classical period, composers often drew out the authentic cadences at the

ends of sections; the cadence's dominant chord might take up a measure or two, e

specially if it contained the resolution of a suspension remaining from the chor

d preceding the dominant. During these two measures, the solo instrument (in a c

oncerto) often played a trill on the supertonic (the fifth of the dominant chord

); although supertonic and subtonic trills had been common in the Baroque era, t

hey usually lasted only a half measure (e.g., the subtonic trill in the final ca

dence from Bach's Wachet auf, ruft uns die Stimme, BWV 140).About this sound Pla

y (helpinfo) Extended cadential trills were by far most frequent in Mozart's musi

c, and although they were also found in early Romantic music, their use was rest

ricted chiefly to piano concerti (and to a lesser extent, violin concerti) becau

se they were most easily played and most effective on the piano and violin; the

cadential trill and resolution would be generally followed by an orchestral coda

. Because the music generally became louder and more dramatic leading up to it,

a cadence was used for climactic effect, and was often embellished by Romantic c

omposers. Later on in the Romantic era, however, other dramatic virtuosic moveme

nts were often used to close sections instead.

Jazz

"'Backdoor' ii-V" in C: ii-?VII7-I About this sound Play (helpinfo)

Ascending diminished seventh chord half-step cadence on C.[29] About this sound

Play (helpinfo)

Descending diminished seventh chord half-step cadence on C.[29] About this sound

Play (helpinfo)

In jazz a cadence is often referred to as a turnaround, chord progressions that

lead back and resolve to the tonic. These include the ii-V-I turnaround and its

variation the backdoor progression, though all turnarounds may be used at any po

int and not solely before the tonic.

Half-step cadences are "common in jazz"[30] if not "clich."[31] For example, the

ascending diminished seventh chord half-step cadence, whichusing a secondary dimi

nished seventh chordcreates momentum between two chords a major second apart (wit

h the diminished seventh in between).[29] The descending diminished seventh chor

d half-step cadence is assisted by two common tones.[29]

Popular music

Popular music uses the cadences of the common practice period and jazz, with the

same or different voice leading. Popular cadences with borrowed chord progressi

ons include the backdoor progression, ?II-I, ?III-I, and ?VI-I.[32]

Rhythmic cadence

Rhythmic cadence at the end of the first phrase from Bach's Brandenburg Concerto

no. 3 in G Major, BMV 1048, I, m. 12. About this sound Play (helpinfo) with pitch

es or About this sound Play (helpinfo) with unpitched percussion.

Rhythmic cadences often feature a final note longer than the prevailing note val

ues and this often follows a characteristic rhythmic pattern repeated at the end

of the phrase,[3] both demonstrated in the Bach example pictured.

See also

Andalusian cadence

Approach chord

Cadenza

Corelli cadence

Drum cadence

English cadence

Kadans

Lament bass

List of Caribbean music genres: Cadence-lypso & Cadence rampa

Picardy third

V-IV-I turnaround

?VII-V7 cadence

References

Don Michael Randel (1999). The Harvard Concise Dictionary of Music and Music

ians, p.105. ISBN 0-674-00084-6.

Benward & Saker (2003). Music: In Theory and Practice, Vol. I, p.359. Sevent

h Edition. ISBN 978-0-07-294262-0.

Benward & Saker (2003). p.91.

Benward & Saker (2003). p.89.

Judd, Cristle Collins (1998). "Introduction: Analyzing Early Music", Tonal S

tructures of Early Music,[page needed]. (ed. Judd). New York: Garland Publishing

. ISBN 0-8153-2388-3.

White, John D. (1976). The Analysis of Music, p.34. ISBN 0-13-033233-X.

Thomas Benjamin, Johann Sebastian Bach (2003). The Craft of Tonal Counterpoi

nt, p.284. ISBN 0-415-94391-4.

Caplin, William E. (2000). Classical Form: A Theory of Formal Functions for

the Instrumental Music of Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven, p.51. ISBN 0-19-514399-X

.

Darcy and Hepokoski (2006). Elements of Sonata Theory: Norms, Types, and Def

ormations in the Late-Eighteenth-Century Sonata, p.. ISBN 0-19-514640-9. "the un

expected motion of a cadential dominant chord to a I6 (instead of the normativel

y cadential I)"

White (1976), p.129-130.

White (1976), p.38.

Jonas, Oswald (1982). Introduction to the Theory of Heinrich Schenker (1934:

Das Wesen des musikalischen Kunstwerks: Eine Einfhrung in Die Lehre Heinrich Sch

enkers), p.24. Trans. John Rothgeb. ISBN 0-582-28227-6.

Finn Egeland Hansen (2006). Layers of musical meaning, p.208. ISBN 87-635-04

24-3.

Randel, Don Michael (2003). The Harvard Dictionary of Music, p.130. ISBN 0-6

74-01163-5.

Caplin, William E. (1998). Classical Form: A Theory of Formal Functions for

the Instrumental Music of Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven. Oxford University Press.

pp. 4345. ISBN 0-19-510480-3.

Foote, Arthur (2007). Modern Harmony in its Theory and Practice, p.93. ISBN

1-4067-3814-X.

Owen, Harold (2000). Music Theory Resource Book, p.132. ISBN 0-19-511539-2.

Kennedy, Michael, ed. (2004). The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Music, p.116.

ISBN 0-19-860884-5.

"Medial cadence." Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online. Oxford University

Press. Web. 23 Jul. 2013.

Berger, Karol (1987). Musica Ficta: Theories of Accidental Inflections in Vo

cal Polyphony from Marchetto da Padova to Gioseffo Zarlino, p.148. Cambridge and

New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-54338-X.

Society for Music Theory (1996-06-06). "Guidelines for Nonsexist Language".

Western Michigan University. Retrieved 2008-07-19.

McClary, Susan (2002). Feminism and Music. University of Minnesota Press. IS

BN 0-8166-4189-7.

Apel, Willi (1970). Harvard Dictionary of Music. cited in McClary, Susan (20

02). Feminine Endings: Music, Gender, and Sexuality, p.9. ISBN 0-8166-4189-7.

Newman, William S. (1995). Beethoven on Beethoven: Playing His Piano Music H

is Way, p.170-71. ISBN 0-393-30719-0.

Benward & Saker (2009). Music in Theory and Practice: Volume II, p.13. Eight

h Edition. ISBN 978-0-07-310188-0.

Dahlhaus, Carl (1990). Studies in the Origin of Harmonic Tonality. trans. Ro

bert O. Gjerdingen. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-09135-8.

Benward & Saker (2009), p.14.

Schubert, Peter (1999). Modal Counterpoint, Renaissance Style, p.132. ISBN 0

-19-510912-0.

Richard Lawn, Jeffrey L. Hellmer (1996). Jazz: Theory and Practice, p.97-98.

ISBN 978-0-88284-722-1.

Norman Carey (Spring, 2002). Untitled review: Harmonic Experience by W. A. M

athieu, p.125. Music Theory Spectrum, Vol. 24, No. 1, pp. 121134.

Mathieu, quoted ibid.

Romeo, Sheila (1999). Complete Rock Keyboard Method: Mastering Rock Keyboard

, p.43. ISBN 0-88284-982-4.

[show]

v

t

e

Cadences

[show]

v

t

e

Chord progressions (list)

[show]

v

t

e

Consonance and dissonance

[show]

v

t

e

Harmony

[show]

v

t

e

Melody

[hide]

v

t

e

Tonality

Cadence

Circle of fifths

Consonance and dissonance

Diatonic scale

Diatonic function

Figured bass

Just intonation

Key

Major and minor

Modulation

Neotonality

Ostinato

Parallel key

Polytonality

Progressive tonality

Schenkerian analysis

Sonata form

Tonicization

Voice leading

Categories:

Cadences

Navigation menu

Create account

Log in

Article

Talk

Read

Edit

View history

Main page

Contents

Featured content

Current events

Random article

Donate to Wikipedia

Wikimedia Shop

Interaction

Help

About Wikipedia

Community portal

Recent changes

Contact page

Tools

Print/export

Languages

Catal

Cetina

Dansk

Deutsch

Espaol

Esperanto

Franais

Italiano

?????

Nederlands

???

Norsk bokml

Norsk nynorsk

Polski

Portugus

Romna

???????

?????? / srpski

Suomi

Svenska

??????????

??

Edit links

This page was last modified on 18 March 2014 at 19:28.

Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License;

additional terms may apply. By using this site, you agree to the Terms of Use a

nd Privacy Policy.

Wikipedia is a registered trademark of the Wikimedia Foundation, Inc., a non-

profit organization.

Privacy policy

About Wikipedia

Disclaimers

Contact Wikipedia

Developers

Mobile view

Wikimedia Foundation

Powered by MediaWiki

Você também pode gostar

- Modalogy: Scales, Modes & Chords: The Primordial Building Blocks of MusicNo EverandModalogy: Scales, Modes & Chords: The Primordial Building Blocks of MusicNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (6)

- Elements of Music (Continued) : MelodyDocumento33 páginasElements of Music (Continued) : MelodyJindred Jinx Nikko Condesa100% (1)

- Harmony to All: For Professionals and Non-Professional MusiciansNo EverandHarmony to All: For Professionals and Non-Professional MusiciansAinda não há avaliações

- Anatomy of A Melody Part 1Documento3 páginasAnatomy of A Melody Part 1jim4703100% (2)

- Tritone interval guideDocumento10 páginasTritone interval guideYero RuAinda não há avaliações

- Harmonic Circles 1Documento4 páginasHarmonic Circles 1Fabián GallinaAinda não há avaliações

- Mathematical Connections Between Music and the BrainDocumento9 páginasMathematical Connections Between Music and the BrainAhyessa Castillo100% (1)

- Lesson 1 Ideniftying ModulationsDocumento9 páginasLesson 1 Ideniftying ModulationsGarethEvans100% (2)

- Hybrid 5 and 4 Part HarmonyDocumento19 páginasHybrid 5 and 4 Part HarmonyC MorzahtAinda não há avaliações

- Keyboard Lessons: Essential Tips and Techniques to Play Keyboard Chords and ScalesNo EverandKeyboard Lessons: Essential Tips and Techniques to Play Keyboard Chords and ScalesAinda não há avaliações

- Theme and Motif in MusicDocumento9 páginasTheme and Motif in MusicMax ZimmermanAinda não há avaliações

- Haye Hinrichsen Entropy Based Tuning of Musical InstrumentsDocumento13 páginasHaye Hinrichsen Entropy Based Tuning of Musical InstrumentsMiguel100% (1)

- Introduction To Music Theory: Inversions of ChordsDocumento3 páginasIntroduction To Music Theory: Inversions of Chordsnaveenmanuel8879Ainda não há avaliações

- Polychord - WikipediaDocumento3 páginasPolychord - WikipediaJohn EnglandAinda não há avaliações

- Tonal Counterpoint InterludeDocumento14 páginasTonal Counterpoint InterludeJanFrancoGlanc100% (1)

- See William Caplin's Classical Form or Analyzing Classical Form, For More DetailsDocumento1 páginaSee William Caplin's Classical Form or Analyzing Classical Form, For More Detailshjkfdshjk fdshjfsdhjksdfAinda não há avaliações

- 4 Part HarmonyDocumento13 páginas4 Part HarmonyRothy CasimeroAinda não há avaliações

- Melodic ConsonanceDocumento18 páginasMelodic ConsonanceCoie8t100% (2)

- Compound IntervalsDocumento5 páginasCompound IntervalsKamila NajlaaAinda não há avaliações

- Contrasted A Chords: Dominant SeventhDocumento6 páginasContrasted A Chords: Dominant SeventhNeven KockovicAinda não há avaliações

- Study Guide For Part-Writing: Vocal Ranges & PlacementDocumento2 páginasStudy Guide For Part-Writing: Vocal Ranges & PlacementLisa Verchereau100% (1)

- The Bass Player's Companion: A G Uide To S Ound, C Oncepts, and T Echnique For The E Lectric BassDocumento55 páginasThe Bass Player's Companion: A G Uide To S Ound, C Oncepts, and T Echnique For The E Lectric BassBassman BronAinda não há avaliações

- Music and mathematics: the mathematical relationships underlying musical scales and harmonyDocumento7 páginasMusic and mathematics: the mathematical relationships underlying musical scales and harmonyblurrmieAinda não há avaliações

- Tertian harmony explainedDocumento7 páginasTertian harmony explainedLeandro Espino MaurtuaAinda não há avaliações

- Root Position Triads by FifthDocumento5 páginasRoot Position Triads by Fifthapi-302635768Ainda não há avaliações

- Harmonic Progressions I Cadential and Prolongational Progressions PDFDocumento6 páginasHarmonic Progressions I Cadential and Prolongational Progressions PDFAlejandroPerdomoAinda não há avaliações

- Polytonality PDFDocumento10 páginasPolytonality PDFFrancesco Torazzo100% (1)

- Quartal Harmony PDFDocumento3 páginasQuartal Harmony PDFRosa victoria paredes wong100% (1)

- Modal Schemas - Open Music TheoryDocumento7 páginasModal Schemas - Open Music TheoryJasmineOchoaAinda não há avaliações

- 1) Harmonic RhythmDocumento1 página1) Harmonic RhythmNickAinda não há avaliações

- What Is HarmonyDocumento1 páginaWhat Is HarmonyerikAinda não há avaliações

- On Variation and Melodic Improvisation inDocumento3 páginasOn Variation and Melodic Improvisation in3426211Ainda não há avaliações

- Notes On History and Theory of Classicalmusic Abstract Art MusicDocumento72 páginasNotes On History and Theory of Classicalmusic Abstract Art MusicAurora SeasonAinda não há avaliações

- Tagg-Harmony Handout PDFDocumento45 páginasTagg-Harmony Handout PDFIgor DornellesAinda não há avaliações

- Introduction To Advance Pentatonic LessonsDocumento4 páginasIntroduction To Advance Pentatonic LessonsLovely GreenAinda não há avaliações

- Who Works Where [and Who Cares?]: A Manager's Guide to the New World of WorkNo EverandWho Works Where [and Who Cares?]: A Manager's Guide to the New World of WorkAinda não há avaliações

- Music Analysis - TANGO NEUVODocumento2 páginasMusic Analysis - TANGO NEUVOjoshup7Ainda não há avaliações

- MotiveDocumento3 páginasMotiveCharlene Leong100% (1)

- Sheet Music (Two Guitars, an Old Piano) Hank and Elvis and MeNo EverandSheet Music (Two Guitars, an Old Piano) Hank and Elvis and MeAinda não há avaliações

- Advanced Chromatic Harmonies IIDocumento5 páginasAdvanced Chromatic Harmonies IIRakotonirainy Mihaja DamienAinda não há avaliações

- Secondary Dominants Preparatory ExercisesDocumento3 páginasSecondary Dominants Preparatory ExercisesFavio Rodriguez Insaurralde100% (1)

- The Workbook: Volume 2 - Further Steps: Visual Tools for Musicians, #3No EverandThe Workbook: Volume 2 - Further Steps: Visual Tools for Musicians, #3Ainda não há avaliações

- Give Your Worship: How To Write Christian Songs In 1 Hour Without Forcing InspirationNo EverandGive Your Worship: How To Write Christian Songs In 1 Hour Without Forcing InspirationAinda não há avaliações

- Chromatic Mediant - WikipediaDocumento7 páginasChromatic Mediant - WikipediaRoberto Ortega100% (1)

- Perfect FourthDocumento5 páginasPerfect FourthAnElysianAinda não há avaliações

- Tagg's Harmony Hand OutDocumento45 páginasTagg's Harmony Hand OutMarkWWWWAinda não há avaliações

- How To Create Tension With Climbing ScalesDocumento5 páginasHow To Create Tension With Climbing ScalesMatia Campora100% (1)

- Theory & Practise Book WMDocumento18 páginasTheory & Practise Book WMJaume Vilaseca0% (1)

- Circle of Fourths/Fifths Explained by L DMELLODocumento4 páginasCircle of Fourths/Fifths Explained by L DMELLOLorenzo Marvello100% (1)

- Theory Basics - 12 Chromatic Tones PDFDocumento2 páginasTheory Basics - 12 Chromatic Tones PDFPramod Govind SalunkheAinda não há avaliações

- Using Binary Numbers in Music: Vi Hart Music Department Stony Brook University Stony Brook, NY, USADocumento4 páginasUsing Binary Numbers in Music: Vi Hart Music Department Stony Brook University Stony Brook, NY, USANEmanja Djordjevic100% (1)

- Augmented sixth chord explainedDocumento9 páginasAugmented sixth chord explainedMayara JulianAinda não há avaliações

- Coltrane's Pancultural PhilosophyDocumento5 páginasColtrane's Pancultural PhilosophyGabriel Sonof Ishmael100% (2)

- Chord How It's Formed ResolutionDocumento4 páginasChord How It's Formed ResolutionDaniel AgiusAinda não há avaliações

- 3 Melodic MinorDocumento13 páginas3 Melodic Minorgg ggg100% (1)

- The CAGED System: A Fretboard FrameworkDocumento21 páginasThe CAGED System: A Fretboard FrameworkAlfa Kim007Ainda não há avaliações

- The Jazz Guitarist's Handbook: An In-Depth Guide to Chord Symbols Book 1: The Jazz Guitarist's Handbook, #1No EverandThe Jazz Guitarist's Handbook: An In-Depth Guide to Chord Symbols Book 1: The Jazz Guitarist's Handbook, #1Ainda não há avaliações

- Basic Harmonization GuideDocumento41 páginasBasic Harmonization Guidefaser04Ainda não há avaliações

- Anger - The Modern Enharmonic Scale As The Basis of The Chromatic Element in MusicDocumento62 páginasAnger - The Modern Enharmonic Scale As The Basis of The Chromatic Element in MusicGregory MooreAinda não há avaliações

- BRITINEY SPEARS 4 AGAINST 3 4 Dotted 8ths Eqauls 3 Quarter Notes - Full ScoreDocumento2 páginasBRITINEY SPEARS 4 AGAINST 3 4 Dotted 8ths Eqauls 3 Quarter Notes - Full ScorePeterAndrewsAinda não há avaliações

- Hip Hop - TrailDocumento2 páginasHip Hop - TrailPeterAndrewsAinda não há avaliações

- Hip Hop - Full ScoreDocumento2 páginasHip Hop - Full ScorePeterAndrewsAinda não há avaliações

- Top 24 Film Composer Pitfalls and SolutionsDocumento5 páginasTop 24 Film Composer Pitfalls and SolutionsSuganthan HarmlessAinda não há avaliações

- Hip Hop - TimeDocumento2 páginasHip Hop - TimePeterAndrewsAinda não há avaliações

- TakadimiDocumento24 páginasTakadimikewlboy24100% (5)

- Hip Hop - Full Score4Documento2 páginasHip Hop - Full Score4PeterAndrewsAinda não há avaliações

- Hip Hop - Full Score 1Documento2 páginasHip Hop - Full Score 1PeterAndrewsAinda não há avaliações

- Advanced Notation 1: LnlonmmmDocumento1 páginaAdvanced Notation 1: LnlonmmmPeterAndrewsAinda não há avaliações

- Fantom GDocumento1 páginaFantom GPeterAndrewsAinda não há avaliações

- Aldwell Counerpoint 2nd Species1Documento1 páginaAldwell Counerpoint 2nd Species1PeterAndrewsAinda não há avaliações

- Aldwell Counerpoint 2nd Species1Documento1 páginaAldwell Counerpoint 2nd Species1PeterAndrewsAinda não há avaliações

- Aldwell Counerpoint 2nd Species1 - Full ScoreDocumento1 páginaAldwell Counerpoint 2nd Species1 - Full ScorePeterAndrewsAinda não há avaliações

- Aldwell Counerpoint 2nd Species1 - Full ScoreDocumento1 páginaAldwell Counerpoint 2nd Species1 - Full ScorePeterAndrewsAinda não há avaliações

- Keyboard shortcuts for notation softwareDocumento7 páginasKeyboard shortcuts for notation softwaretrumpet5347Ainda não há avaliações

- Aldwell Counerpoint 2nd Species1 - Full ScoreDocumento1 páginaAldwell Counerpoint 2nd Species1 - Full ScorePeterAndrewsAinda não há avaliações

- Kitsons Counterpoint My ExercisesDocumento2 páginasKitsons Counterpoint My ExercisesPeterAndrewsAinda não há avaliações

- Viola Music Sheet NotationDocumento2 páginasViola Music Sheet NotationChris FunkAinda não há avaliações

- Groove Lesson - SALSA The Verse PDFDocumento1 páginaGroove Lesson - SALSA The Verse PDFThomas MaxwellAinda não há avaliações

- Chord Tones For Modes of The Major ScaleDocumento1 páginaChord Tones For Modes of The Major ScaleJared BerrimanAinda não há avaliações

- Charles Wuorinen Simple Composition Longman 1979Documento171 páginasCharles Wuorinen Simple Composition Longman 1979Cayetana Ig100% (1)

- Bassoon Passodoble Allegro by OsórioDocumento3 páginasBassoon Passodoble Allegro by OsórioRomeu SilvaAinda não há avaliações

- AT8 ManualDocumento95 páginasAT8 Manualfede6790Ainda não há avaliações

- Repertoire 1Documento3 páginasRepertoire 1api-584384396Ainda não há avaliações

- 01 - Balan Harmonie NégativeDocumento10 páginas01 - Balan Harmonie NégativePierre Fargeton100% (1)

- Counterpoint - GroveDocumento33 páginasCounterpoint - GroveLucas CompletoAinda não há avaliações

- How To Practice Jazz Scales The Right WayDocumento11 páginasHow To Practice Jazz Scales The Right Wayblancofrank545100% (3)

- Harmony Modern (Sintesis)Documento3 páginasHarmony Modern (Sintesis)adebuyaAinda não há avaliações

- Schutz PaperDocumento8 páginasSchutz PaperJack BreslinAinda não há avaliações

- Abrsm PiaAbrsm Piano Grade 2 No Grade 2 2011 2012 PDFDocumento14 páginasAbrsm PiaAbrsm Piano Grade 2 No Grade 2 2011 2012 PDFΝΙΚΟΛΑΟΣ ΚΟΦΙΝΑΚΗΣ0% (1)

- How To Use The CAGED System To Play A Solo PDFDocumento7 páginasHow To Use The CAGED System To Play A Solo PDFBevanChrizAinda não há avaliações

- Yamaha Qy10 OmDocumento153 páginasYamaha Qy10 Omjorrit wAinda não há avaliações

- Intro To Music Class Notes (WORD)Documento11 páginasIntro To Music Class Notes (WORD)audbal600Ainda não há avaliações

- Music Theory Worksheet 19 Major ScaleDocumento1 páginaMusic Theory Worksheet 19 Major ScalesaxgoldieAinda não há avaliações

- Arranging For Strings, Part 3Documento5 páginasArranging For Strings, Part 3MassimoDiscepoliAinda não há avaliações

- Carlos Santana - Flor Dluna Moonflower PDFDocumento18 páginasCarlos Santana - Flor Dluna Moonflower PDFRoy Rodriguez100% (1)

- Horsley Nathan Chad PDFDocumento142 páginasHorsley Nathan Chad PDFSebastianCamiloLeonRamirezAinda não há avaliações

- MIDI Arranging Syllabus Music 205 2010Documento3 páginasMIDI Arranging Syllabus Music 205 2010zerraAinda não há avaliações

- T3TP 2018 Grade 3 Test Paper UncompletedDocumento6 páginasT3TP 2018 Grade 3 Test Paper Uncompletedelleanor.pasztorAinda não há avaliações

- Rebuffa - Baroque GuitarDocumento2 páginasRebuffa - Baroque GuitarDavidMackorAinda não há avaliações

- Module 5 - Teaching Music To Elementary GradesDocumento8 páginasModule 5 - Teaching Music To Elementary GradesMarkhill Veran TiosanAinda não há avaliações

- Searby M 6293Documento8 páginasSearby M 6293pinorosAinda não há avaliações

- Unit 3: Melody and HarmonyDocumento6 páginasUnit 3: Melody and HarmonyieslasencinasmusicaAinda não há avaliações

- Year 9 Fusion Song writing bookletDocumento24 páginasYear 9 Fusion Song writing bookletAmaresh UmasankarAinda não há avaliações

- Jeremy Siskind - Playing Solo Jazz PianoDocumento43 páginasJeremy Siskind - Playing Solo Jazz PianoRodrigo Bartsch100% (4)

- Rhythm Changes Solo StudyDocumento4 páginasRhythm Changes Solo StudyPete SklaroffAinda não há avaliações

- French Spectral MusicDocumento35 páginasFrench Spectral MusiccdschAinda não há avaliações

- Gypsy Guitar PDFDocumento8 páginasGypsy Guitar PDFСергей Фиалковский100% (1)

![Who Works Where [and Who Cares?]: A Manager's Guide to the New World of Work](https://imgv2-2-f.scribdassets.com/img/word_document/221082993/149x198/082adcf045/1630520718?v=1)