Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Leadership Development For Construction SMES

Enviado por

absoluto_1Descrição original:

Título original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Leadership Development For Construction SMES

Enviado por

absoluto_1Direitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Proceedings EPOC 2012 Conference

1

Working Paper Proceedings

Engineering Project Organizations Conference

Rheden, The Netherlands

July 10-12, 2012

Leadership Development for Construction SMES

George Ofori and Shamas-ur-Rehman Toor

Proceedings Editors

Amy Javernick-Will, University of Colorado and Ashwin Mahalingam, IIT-Madras

Copyright belongs to the authors. All rights reserved. Please contact authors for citation details.

Proceedings EPOC 2012 Conference

2

LEADERSHIP DEVELOPMENT FOR CONSTRUCTION SMEs

George Ofori

1

and Shamas-ur-Rehman Toor

2

ABSTRACT

Construction firms face considerable problems and risks. Thus, there is a high rate of

mortality among such firms. On the other hand, in each country, these companies undertake the

projects which are required to provide a basis for economic growth and development, and

enhancement of the quality of life of the populace. Small and medium-sized construction

enterprises (SMEs) undertake the large number of projects dispersed throughout the country.

They form the bulk, by number, of companies in each industry, and offer operational flexibility

to the larger firms in their role as sub-contractors. Therefore, in many countries, there are

programmes to support the development of construction SMEs. The main components of these

programmes are financial assistance schemes, initiatives to support the acquisition of equipment,

and training. With regard to training, the concentration has been on imparting managerial and

technical skills. However, there is a consensus that there is a difference between management

and leadership, and that the entrepreneur must combine skills in both management and

leadership. It is important for the owners of construction companies to be good leaders. Thus,

their leadership capabilities should be enhanced.

A study on leadership development in the construction industry in Singapore is reported.

The study was based on 45 interviews with a total of 49 senior leaders of the industry. The

findings from this study forms the basis of a discussion of possible courses of action in

leadership development for construction SMEs.

KEYWORDS: Leadership development, small and medium-sized enterprises, construction

INTRODUCTION

Need for Leadership in Management of Construction SMEs

The construction industry is usually described as being one of the most risky business

arenas. Small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) face particularly harsh business

environments. Examples of the risks (Toor and Ofori, 2008a) are those which are inherent in

construction activity such as lack of job continuity owing to the project-based nature of the

industry. Another group of risks concern the deficiencies in individual construction industries

themselves. Finally, there are several risks in the operating environment of the industries such as

difficulties in access to finance.

Today, the construction SME faces even more risks and challenges. First, the

beneficiaries and other stakeholders of projects are more knowledgeable, better organised and

have more exacting demands. Second, in all countries, more regulations are being introduced in

efforts to address environmental, health and safety and other concerns. Third, there is greater

competition from the larger number of enterprises in the industry offering the same services.

Fourth, the business partners of these firms also have greater expectations as they seek to

1

Professor, National University of Singapore, Singapore, bdgofori@nus.edu.sg.

2

Senior Manager, Islamic Development Bank, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, shamastoor@isdb. xxx.

Proceedings EPOC 2012 Conference

3

enhance their own competitiveness and project performance. Fifth, the firms must cope with a

situation in which there is greater stress on professionalism and transparency.

At the same time, construction offers several opportunities to SMEs, as evinced by the

large number of such companies in each country, giving the industry a typically pyramidal

structure. Moreover, help is available to companies to enable them to take advantage of the

opportunities and address the challenges and risks. There is greater understanding of the industry

and increasing maturity in policy development. There is also better awareness of the nature and

needs of construction SMEs. This has led to the development of more appropriate and better-

focused policies, programmes and initiatives for SME development, including training

programmes. Today, these firms have access to more, better and more user-friendly tools and

techniques, many of which are computer-based. In business, in the difficult operating

environment, there is greater tendency towards solidarity among businesses and their leaders to

foster their common interests.

There is the need for the SME entrepreneur to be more aware and able to inspire their

employees, clients and partners in order to attain greater joint performance. They should also be

strategic in orientation, better able to deal with risk and uncertainty, and adept at participating in

alliances and partnerships. In short, the SME entrepreneur, especially today, must be a leader.

Objectives of Research

The study addresses the following questions: What is leadership? Is there a difference

between leadership and management? How relevant is leadership to an SME in construction?

Who is a good SME construction leader? How can construction SME leaders be developed?

From a discussion based on the key works in the literature, the nature of leadership is

explained. Leadership is distinguished from management, while drawing out the

complementarities. What it means to be a leader in construction, and what it takes to succeed as a

leader of an SME in construction are discussed. A portion of a field study on authentic leadership

development in Singapore is presented. The final part of the paper is devoted to a consideration

of how construction SME leaders can be developed.

Leadership and management

There have been efforts to differentiate leadership from management (Zaleznik, 1977;

Bennis and Nanus, 1985). Mintzberg (1990) studied how managers spent their time and which

tasks they performed. He concluded that managers carry out the traditional functions of planning,

organising, co-ordinating and controlling. They perform ten related roles, which are in three

main categories: (i) interpersonal roles (figurehead, leader and liaison roles); (ii) informational

roles (monitor, disseminator and spokesperson roles); and (iii) decisional roles (entrepreneur,

disturbance handler, negotiator and resource allocator roles). Thus, leadership is one of the

functions of a manager.

As Toor and Ofori (2008a) argue, leadership is long-term, visionary, and purpose-

oriented, and seeks to attain innovation and change, while management is short-term, narrow,

and task-focused, and aspires to achieve control and stability. Similarly, leaders and managers

undertake different functions, apply different conceptualizations and approaches to work,

exercise different problem-solving approaches, and exhibit different behaviours owing to their

Proceedings EPOC 2012 Conference

4

different motivations. However, especially in the construction industry, emphasis on managerial

functionalism blurs the boundaries between management and leadership (Chan, 2008).

LEADERSHIP: A REVIEW

What is Leadership?

There is still a debate on the nature of leadership. Indeed, there is no consensus on a

definition. Some more recent definitions include that of Chemers (1997, p. 1) who believed that:

Leadership is a process of social influence in which one person is able to enlist the aid and

support of others in the accomplishment of a common task. Vroom and Jago (2007, p. 18)

defined leadership as: A process of motivating people to work together collaboratively to

accomplish great things.

The study of leadership in the context of business organizations started in the early

twentieth century, from the classical management period when leader and follower

characteristics were differentiated (Taylor, 1911). Various models of leadership have been

proposed by researchers since then. For example, contingency theories were championed by

those who started thinking about leadership in relation to situation (Fiedler, 1967). Each

leadership approach and theory is criticised. For example, criticisms of contingency theory relate

to its conceptual and methodological weaknesses (Yukl, 2002; Vroom and Jago, 2007). A

notable observation is that the the new models do not displace, but co-exist with the older ones.

The new models include collaborative leadership, which Ibarra and Hansen (2011) define as:

the capacity to engage people and groups outside ones formal control and inspire

them to work toward common goals despite differences in convictions, cultural values,

and operating norms .

Authentic Leadership

The above section shows that there are many models of leadership, each of which has its

own importance. The current study was undertaken on authentic leadership development in

Singapore. Recent research shows that authenticity is fundamental to good leadership (Avolio

and Gardner, 2005). In social psychology, authenticity is the unobstructed operation of ones

true, or core, self in ones daily enterprise (George, 2003). Walumbwa et al. (2008) define

authenticity of leadership as a pattern of leader behaviour that draws upon and promotes both

positive psychological capacities and a positive ethical climate, to foster greater self-awareness,

an internalized moral perspective, balanced processing of information, and relational

transparency on the part of leaders working with followers, fostering positive self development

(p. 94). To George (2003), authentic leaders have a sense of purpose, practise solid values, lead

with heart, and establish connected relationships. Such leaders empower others. They are

consistent and self-disciplined and never compromise on their principles. This definition was

adopted in the study in Singapore.

Leadership in Construction

How relevant is leadership to construction? Many studies, in industrialised nations

(Kangari, 1988; Russell, 1991; Abidali and Harris, 1995; Kale and Arditi, 1999; Arditi et al.,

Proceedings EPOC 2012 Conference

5

2000; Koksal and Arditi, 2004) and developing countries (Jannadi, 1997; Enshassi et al., 2006)

show that business failures are common in construction. A wide range of reasons are cited for

these failures. For example, Davidson and Maguire (2003) found the top ten reasons for

contractor failure to include: growing too fast, obtaining work in a new geographic region,

increase in the sizes of single jobs, obtaining new types of work, high employee turnover,

inadequate capitalization, poor estimating, poor accounting systems, and poor cash flow.

The reasons cited by Koksal and Arditi (2004) for organisational failures in construction

included insufficient capital, lack of business knowledge, fraud, lack of managerial experience,

lack of line experience, lack of commitment, poor working habits, over expansion and

environmental problems such as weaknesses in the industry, the impact of various disasters,

poor growth prospects, and high interest rates. Thus, there is still a lack of appreciation, among

researchers of the dangers of ineffectiveness of leaders in the construction industry.

There is greater need for leadership in construction in the developing countries. First,

there are more reports of severe project performance deficiencies such as cost and time overruns,

poor quality, technical defects, poor durability, and inadequate attention to safety and

environmental issues (Ofori, 2012). Second, there is even greater implication of poor

performance (for long-term national socio-economic development and sustainability). Finally,

the clients, end purchasers, users and other stakeholders of the construction industry have little or

no knowledge of any of the aspects of construction.

What is the status of knowledge on leadership in construction? Toor and Ofori (2008b)

reviewed works on leadership in the construction management literature and observed that

empirical works on the effectiveness and performance of construction leaders appeared in the

1980s (Bresnen, 1986; Bryman et al., 1987). In the 1990s, the focus moved onto leadership style,

attributes, and behaviours of leaders of projects (Dulaimi and Langford, 1999; Rowlinson et al.,

1993). However, Toor and Ofori (2008b) argue that leadership research in construction has relied

on old frameworks and empirical work based on quantitative analyses. Chan (2008) also

observes that the understanding of leadership in construction is primitive as it depends on

managerial functionalism.

An increase in interest in leadership in construction is evident. New research centres, and

international networks on leadership in construction have been set up. Toor and Ofori (2008b)

proposed a research agenda for leadership in construction. McCaffer (2008) called for a

concerted effort by researchers around the globe, noting: What is needed is a global research

institute concentrating on leadership development in construction (p. 306).

Leadership Development

There has been a long debate on whether leaders are born or can be developed through

structured educational and/or training programmes. This born or made debate is still ongoing.

However, there appears to be a consensus that whereas certain traits (which are considered in

some contexts to be desirable in leaders) may be endowed, one can develop at least some of the

attributes and capabilities of leaders through appropriate structured interventions. Thus, there

have been attempts to study how leaders develop, in order to help formulate these interventions.

Rothstein et al. (1990) suggest that a leaders personal history, trigger events, experiences at

work, and personal and organisational factors may be potential antecedents to their emergence as

leaders and their effectiveness in this role.

Proceedings EPOC 2012 Conference

6

Avolio (2007) noted that leadership can be better understood by researching when, where

and how it is activated and how it makes a difference in team performance and process

effectiveness. Luthans and Avolio (2003), in their initial conceptualisation of authentic

leadership development, stress the need to construct taxonomies of trigger events that promote

positive leadership development. The study of leadership development is still new.

SMES IN CONSTRUCTION AND THEIR DEVELOPMENT

Importance of Construction SMEs

SMEs are defined in several ways. The main distinguishing feature is size, as determined

by number of employees, paid up capital or turnover. The categorisation differs from one sector

to another. In this paper, the construction SME is defined in terms of its financial holding which

determines the size (in terms of value) of the projects it can undertake. In Singapore, the firms in

the bottom two of the six-group categorization of registered contractors are usually considered to

be SMEs (details of this registration system can be found at http://www.bca.gov.sg). This

classification is adopted in this paper.

In construction, the SME is critical in the structure of the industry. The projects which

have to be undertaken by these firms are dispersed geographically throughout each country.

These projects are disparate in nature. This makes consolidation impossible and/or unnecessary.

For example, during its life, each built item generates a stream of repair and maintenance work,

most of which are in small packages. The variety of specialisations in construction facilitates

corporate autonomy and thus, the presence of such firms. The existence of SMEs facilitates the

flexible employment approaches which main contractors adopt in order to obviate the business

instability which is one of the effects of the project-based nature of construction.

Programmes to develop construction SMEs have been introduced in countries at all levels

of development, and especially in developing nations (Ofori, 1991). United Nations Centre for

Human Settlements (1996) undertook a comprehensive study of such programmes; Shakantu

(2012) presents a good recent review. The most comprehensive programmes in these regards

include the training of the entrepreneur and the firms personnel; the provision of financial

assistance such as access to soft loans; and the provision of plant-hire facilities. Other elements

of such programmes include the offering of extension facilities in supervision; assistance in

estimating and tendering for projects; and provision of project opportunities during an initial

period after training. On many national contractor development programmes, the package of

assistance offered depends on the needs of the target beneficiary SME. Mentoring is one of the

arrangements. The SME entrepreneur is placed under the tutelage of an established contractor.

The training and even mentoring, focuses on the development of technical and managerial

expertise. The enhancement of leadership skills is not among the desired outcomes.

FIELD STUDY

Research Method

Data Collection

Interviews formed the primary source of data collection in the study. Interviewing has

been a popular way of data collection, as it enables a rich perspective of processes giving rise to

Proceedings EPOC 2012 Conference

7

leadership development to be captured (Conger 1998; Egri and Herman 2000). A peer

nomination (snowball sampling) process was adopted for interviewee selection. In the first phase

of the study, five past or current presidents of professional organizations and trade associations

in Singapores construction industry were interviewed considering that they were authentic

leaders in their respective areas as they were elected by their own peers. These leaders were

asked to nominate professionals who they thought were close to the definition of authentic

leaders proposed by George (2003) (see above); these were then interviewed. This helped to

reduce social desirability and personal bias. Nominations continued to be sought until most of

the persons nominated were among those who had already been interviewed. A total of 45

interviews were held with 49 authentic leaders in the construction industry affiliated to

developers, design firms, contractors and administrators.

A typical interview was designed to be one-hour long. With the interviewees consent,

each interview was recorded with a digital recorder and note-taking by two persons. An

independent person transcribed the audiotape recording of the interviews.

The questions asked during the interviews which are reported on here as the answers are

relevant to SMEs included: (i) the interviewees leadership philosophy; (ii) the influence of

significant individuals and events on their leadership development; (iii) key turning points in

their leadership development; (iv) the personal and professional challenges they had faced; (v)

their ambitions and aspirations as leaders; (vi) their approach to developing followers; (vii) what

they wanted to achieve as leaders; and (viii) the legacy they hoped to leave behind. Some

interviewees provided documents which were useful in data analysis such as curriculum vitae,

articles they had written, company brochures, and presentations on firms philosophy and values.

Data Analysis

In this qualitative research study, an initial coding scheme was constructed. However,

after analysis of a few interviews, the coding scheme matured into lower order, middle order, and

higher order categories as the axial coding was carried out. Open coding was performed, starting

with transcriptions of interviews: (i) to ask questions about the data; and (ii) to compare various

concepts across the cases. In this process, concepts were identified and their properties and

dimensions were discovered in the data. Microanalysis was carried out to code the meaning

found in words or groups of words (Strauss and Corbin, 1998). It was performed by giving

different incidents a conceptual label, by grouping together similar conceptual labels under a

common conceptual category, and then developing each category in terms of its properties, sub-

properties, and dimensions.

The latest version of NVivo

TM

(NVivo7) was used in the data analysis in this research.

Nvivo7 aided the data analysis in many ways: facilitating the management of the data; and

allowing text or discourse to be edited, visually coded, contextually annotated, hyperlinked to

other texts or multimedia data, and searched according to parameters specified by the user.

FIELD STUDY RESULTS

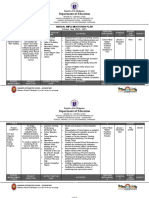

Table 1 shows the profile of the 49 interviewees. It indicates that the interviewees were

mostly chief executive officers, managing partners, general managers, and directors of various

construction-related organizations including developers, architects, engineers, contractors, and

quantity surveyors in Singapore.

Proceedings EPOC 2012 Conference

8

Table 1 Demographic details of interviewees

Attribute Range/Properties No. of Cases

Gender

Male 42

Female 7

Age Group

30-40 9

40-50 14

50-60 23

60-70 3

Company Size

20-50 Employees 2

50-100 Employees 2

100-150 Employees 2

150-200 Employees 2

200-300 Employees 13

300-500 Employees 11

500-1000 Employees 14

>1000 Employees 3

Company Type

Architects 8

Consultants (Engineers, Designers) 9

Contractors 7

Developers 11

Quantity Surveyors 7

Architects + Engineers 4

Others 3

Education

PhD 3

Post-graduate Degree 18

Graduate Degree 27

Polytechnic Graduate 1

Experience as a Leader

5-10 Years 5

10-15 Years 12

15-20 Years 12

20-25 Years 15

25-30 Years 5

Experience in the Industry

5-10 Years 3

10-15 Years 4

15-20 Years 6

20-25 Years 12

25-30 Years 10

30-35 Years 12

35-40 Years 2

Position in the

Organization

Manager and senior manager 7

General/Deputy General Manager 2

Director/Executive Director 20

Managing Director 2

CEO/Deputy CEO 10

Managing partner 2

President/Vice President 4

Chairman/Group Chairman 2

Proceedings EPOC 2012 Conference

9

The Interviews

The interviews focused on stories and narratives of the leaders about how they developed

as leaders. From the analysis, the incidents and events were placed into four phases: preparation

for leadership (events, incidents, and experiences during childhood and early adolescence);

polishing and practising of leadership (events, incidents, and experiences during adulthood);

performing leadership (events, incidents, and experiences when respondents realised success as

performing leaders); and passing leadership (events, incidents, and experiences when leaders

were passing the reigns of leadership to the next generation). This paper covers polishing and

practising of leadership. Specifically, it considers aspects of the answers to the question: Can

you remember a single most important event, incident or turning point that transformed you as a

person and inspired your leadership style? The paper focuses on the development of leadership

through direct mentoring and indirect acquisition of leadership skills from the leaders boss or

bosses and others in the construction industry over time.

Learning from seniors, bosses, and mentors

Apart from the interviewees who were running family companies, the interviewees

consistently identified bosses, mentors, and coaches as persons who had played pivotal roles at

various stages of their careers through mentorship, guidance, coaching, and direction. A senior

director in a consulting firm observed:

I had a good mentor, an architect. He was the executive director of the firm. He was a

very loyal executive. He mentored me, and the training was very, very good. We

embarked on many huge projects together at that time.

The CEO of a large contractor firm was also appreciative of his mentor. He noted: So

far I have come across one very major mentor who saw it as his personal duty to mentor me; he

volunteered to mentor me. A Vice President in a developers firm also identified her boss as

having had a great influence on her. She said:

My former boss in my previous company is the one who inspired me...He was very

down to earth. He was a very warm person, and a very different one.

A senior manager also praised his boss for the mentoring he provided:

My boss actually changed me. I learnt how he dealt with time, leadership and

management. He had great problem-solving skills. To me, as a young engineer, that

really affected me deeply.

One Director of a multi-disciplinary firm, an architect by profession, noted that two of

her bosses had influenced her. One of them: Really managed to motivate his staff although he

was very quiet. I learnt a bit from him in focusing, and dealing with people. Of the other boss,

she said:

I admired him as a leader. He was very approachable. He scolds us when we dont go

and see him. He never blames you when you have a problem. He challenged us, asked us

to try new things. He managed to remove fear. ..He is very different from other people.

He didnt act as a civil servant. And he rewarded people; he did not punish people.

A senior manager noted:

Proceedings EPOC 2012 Conference

10

It was [through] learning with my boss. He actually changed me. I learnt how he dealt

with time, leadership and management. He had great problem solving skills. as a

young engineer, that really affected me deeply.

The Managing Partner of a QS firm learned a great deal from the senior partner of the

firm he worked with in the UK. He advised him to put the company first, and taught him to learn

to make hard decisions, and not to expect everyone to agree with him.

The CEO of an engineering consultancy firm noted: I believe we can always learn from

all people, including cleaners, security guards and site workers.

Mentoring as a Leaders Responsibility

The leaders interviewed had much to share with their followers. They had all reached the

top by dint of hard work. This made them useful potential mentors. The CEO of a design firm, a

woman, shared the actions to address initial difficulties in business, not only as a woman, but

also, in trying to break into the established order:

Getting projects was a problem in the beginningI could not get government projects

as I had no record then. They told me that I had to prove myself to get government

contracts. So I went to the private sector and built up my record; initially, I helped many

people without charging them any money. Now I tell people that one should be very

well prepared to take risks in business. But there is satisfaction in seeing the company

grow.

Even those interviewees who became leaders in their own family firms considered

themselves to have worked hard towards their position; they rose as they proved themselves from

humble positions in the organisations. As the CEO of a large developers firm observed, Things

dont get handed down to anybody on a platter. That sort of leadership doesnt really work in the

market we are in.

The study showed that leaders come in many forms. For example, whereas a Deputy

General Manager of a foreign-owned firm declared that: Sometimes I am too forceful and

overbearing, at the other end of the spectrum, a Director in an architects firm stated: Nobody

works under me; they work with me. However, most of the leaders considered mentoring a

responsibility of all senior personnel. The Director of projects of a developers firm observed:

As you grow older, mentoring is an important part of your life. And dont begrudge the guy.

After all, somebody has mentored you. He went on: You grew from the ranks; dont forget the

people. Be grateful when people point out your faults to you.

The Managing Partner of a QS firm listed his three greatest desires:

First, I want to make sure that all my people are given a chance to do well. Second, I

want them to know that I really appreciate what they are doing. Finally, I really want to

know each of them as a person, but I know I can never do that. There is not enough time.

That is the greatest shame.

The Director of Projects of a developers firm declared that what he dearly wanted to

achieve was to mentor the followers in the second and third tiers of the hierarchy to take over

from him. He was developing a succession plan to enable the unit of the company to continue

Proceedings EPOC 2012 Conference

11

after him. The Chairman of a QS firm noted: Others must grow with me. If you only think about

yourself you will not get far. His firm puts much effort into human capital development. He

added: People make the business so you must build up the people first. The Chairman of a

group of construction firms related the definition of management which a top businessman: To

seek talent, to nurture talent, to utilise talent and to retain talent.

How is mentoring to be done? One CEO of an engineering consultancy firm noted:

I believe we will have followers when we share the same objective. They can see you

are working hard to achieve these objectives. Communication is very important. And

you have to speak their language. We always talk using our own language. That may

not be understood by our target audience. you have to be fair to everyone, and give

them a chance to participate and be heard.

Finally, on the role of the leader as a mentor, the Director of Projects of a developers

company noted:

In the construction industry, leadership is required at many levels. The person sitting at

the pinnacle should be able to play a strong facilitating role, to allow various leaders to

grow around him, and [he should] provide mentorship.

The Followers Responsibility to Learn

On the other hand, there is the onus on the follower to learn, and not only from the

persons direct boss(es). A Deputy General Manager of a foreign-owned firm suggested: In

professional life, you meet many people who are smarter than you. So, you learn from them. A

Director in an architects firm observed: Everyone is born equal. It is a matter of exposing

yourself to opportunities. Dont be compartmentalised in your position, or be limited by your

dreams. The Chairman of a group of construction firms noted that: Most leaders are well

prepared. They are very creative and versatile. They are waiting for an opportunity. When it

strikes, they come up.

The Chairman of a group of construction firms noted that leadership is not embodied in

any one person. You have to learn a little from each of them. He added that: Leadership is

made up of character, and character from the principles one believes in. therefore, teaching such

basics in primary school would be most useful.

ISSUES OF VALIDITY AND RELIABILITY

What was done to ensure validity and reliability of this qualitative research study?

Various suggestions of appropriate strategies and methods of good practice are discussed in the

literature (see, for example, Bryman, 2004; Elliott, 2005; Corbin and Strauss, 2008). Care was

taken in the research towards this end. Two methodological examples are now outlined.

How credible are the stories and narratives of the interviewees? Kempsters (2006)

concept of internal triangulation for enhancing the reliability of information collected was

adopted in the research. The responses of each interviewee during various stages of the particular

interview when the interviewee talked about the respondents early life, leadership philosophy,

challenges and failures, aspirations and intended legacies were compared. All the interviewees

remained consistent in their responses throughout the interviews. The contents of the interviews

Proceedings EPOC 2012 Conference

12

were also, loosely, related to each other to check for consistencies. Moreover, factual

information provided on events was verified.

Theoretical sampling was adopted in the study in seeking to collect data from places,

people, and events that will maximize the opportunities to develop concepts in terms of their

properties and dimensions, uncover variations, and identify relationships between concepts

(Corbin and Strauss, 2008). In the analysis of the first phase of interviews, some trends and

issues related to leadership development and influence were seen to be emerging. In the

subsequent interviews, questions related to such trends and issues were emphasized. This process

went on until nothing new was occurring within the data and most of the major categories had

reached the stage of saturation.

How was researcher bias avoided in the study? As discussed above, the selection of

interviewees was undertaken in a structured manner, based on the determinants of authenticity of

leaders. The note-taking by two persons, which was checked with audio recording, eliminated

bias in the researchers.

POSSIBLE ACTION

Some possible actions are discussed in this section. How can SME leaders develop their

leadership abilities and those of their subordinates? The study shows that analyses of the

professional and leadership development of recognized leaders in the particular industries can

help. There is the need for a national agenda on leadership development for the construction

industry in each country. This should be a joint activity by government, industry and the tertiary

academic institutions. In each country, it will be necessary to undertake action research

(involving industry in problem formulation and review) on leadership development in the context

of the particular country and the construction industry. This research should focus on the needs

of SMEs, considering their importance in the construction industry. In such studies, the

researchers should work closely with industry to develop and test theories of leadership and their

relevance to construction firms; and to develop practices facilitating the leadership development

of practitioners.

The involvement of acclaimed leaders of the industry in the development of the

leadership capabilities of SME entrepreneurs should be explored. For example, structured

mentoring programmes would be helpful. These should be adopted by all the larger construction

firms in the industry. They can take the form of:

mentoring, on aspects including leadership, by main contractors of their subcontracting

entrepreneurs on the job

training of SME entrepreneurs by management consultants using recognised

interventions

structured review of the performance of the subcontractors at the end of each project to

determine areas for improvement

provision of incentives and support schemes to foster the mentoring and training

programmes.

There should be ways and means of formalising and duly recognising such mentorships.

For example, they could be administered by the statutory agencies which register professionals,

which set the criteria for, and drive, continuing professional development.

Proceedings EPOC 2012 Conference

13

CONCLUSION

Leadership, as a field, continues to grow and develop, and perhaps it will never stop

evolving as it is psychological, social and cultural in its functioning. Leadership is important to

the SME for many reasons. First, the entrepreneur sets the vision for the company; this is a key

function of a leader. Second, the entrepreneur is close to all aspects of the business, and should

motivate people in all the areas of the firms operations. Third, the entrepreneur is directly

involved with the customers and partners of the company. Finally, the personal performance of

the entrepreneur can have a major impact on the business. In the construction industry,

leadership is critically needed. The individual practitioner should operate as a leader, and should

seek to develop leadership skills. In this way, organisations will comprise individuals with a

clear understanding, and keen sense, of leadership and how leaders function, what they need, and

the factors which contribute to their success. The construction SMEs, which usually have small

numbers of personnel, would benefit from such developments.

REFERENCES

Abidali, A.F. and Harris, F., A methodology predicting failure in the construction industry.

Construction Management and Economics, 13(3), 189-196, 1995.

Arditi, D., Koksal, A. and Kale, S., Business failures in the construction industry. Engineering,

Construction and Architectural Management, Vol. 7, No. 2, pp. 120-132, 2000.

Avolio, B.J., and Gardner, W.L., Authentic leadership development: Getting to the root of

positive forms of leadership. The Leadership Quarterly, 16(3), 315-338, 2005.

Avolio, B.J., Promoting more integrative strategies for leadership theory building. American

Psychologist, 62, 25-33, 2007.

Bennis, W. G., and Nanus, B., Leaders: The strategies for taking charge, New York: Harper and

Row, 1985.

Bresnen, M.J., The leader orientation of construction site managers, Const. Eng. & Mgmt.,

Vol. 112(3), pp. 370-86, 1986.

Bryman, A., Qualitative research on leadership: A critical but appreciative review. The

Leadership Quarterly, 15(6), 729-69, 2004.

Bryman, A., Bresnen, M., Ford, J., Beardsworth, A. and Keil, T., Leader orientation and

organizational transience: an investigation using Fiedlers LPC scale, Journal of

Occupational Psychology, Vol. 60(1), pp. 13-19, 1987.

Chan, P., Leaders in UK construction: the importance of leadership as an emergent process,

Construction Information Quarterly, Vol. 10(2), pp. 53-58, 2008.

Chemers, M.M. (1997) An Integrative Theory of Leadership. Mahwah, NJ: Earlbaum.

Conger, J.A., Qualitative research as the cornerstone methodology for understanding

leadership. The Leadership Quarterly, 9(1), 107-121, 1998.

Corbin, J.M. and Strauss, A.L., Basics of Qualitative Research, London: Sage Publications,

2008.

Davidson, R.A. and Maguire, M. G. Ten most common causes of construction contractor

failures. Journal of Construction Accounting and Taxation, January/February, 35-37, 2003.

Dulaimi, M. and Langford, D.A., Job behaviour of construction project managers: Determinants

and assessment, J. of Const. Eng. & Mgmt., Vol. 125(4), pp. 256-64, 1999.

Proceedings EPOC 2012 Conference

14

Egri, C. P., and Herman, S., Leadership in the North American environmental sector: Values,

leadership styles, and contexts of environmental leaders and their organizations. Academy

of Management Journal, 43, 571604, 2000.

Elliot, J., Using narrative in social research: Qualitative and quantitative approaches. London:

Sage, 2005.

Enshassi, A., Hallaq, K., and Mohamed, S., Causes of contractors business failure in

developing countries: The case of Palestine. Journal of Construction in Developing

Countries, 11(2), 1-14, 2006.

Fiedler, F.E., A Theory of Leadership Effectiveness. McGraw-Hill, New York, 1967.

George, B., Authentic Leadership: Rediscovering the Secrets to Creating Lasting Value, San

Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 2003.

George, B. and Sims, P., True North: Discover your authentic leadership. San Francisco, CA:

Wiley, 2007.

Ibarra, H. and Hansen, M.T., Are you a collaborative leader? Harvard Business Review, Vol.

89, Issue 7/8, pp. 68-74, 2011.

Jannadi, M.O., Reasons for construction business failures in Saudi Arabia. Project

Management Journal, 28(2), 32-36, 1997.

Kale, S. and Arditi, D., Age-dependent business failures in the US construction industry,

Construction Management and Economics, 17(4), 493-503, 1999.

Kangari, R., Business failure in construction industry, Journal of Construction Engineering

and Management, 114(2), 172-190, 1988.

Koksal, A. and Arditi, D., Predicting construction company decline, Journal of Construction

Engineering and Management, 130(6), 799-807, 2004.

Kempster, S., Leadership learning through lived experience: A process of apprenticeship?

Journal of Management and Organization, 12(1), 4-22, 2006.

Luthans, F. and Avolio, B.J., Authentic leadership development. In K.S. Cameron, J.E. Dutton,

and R.E. Quinn (Eds.) Positive Organizational Scholarship: Foundations of a new

discipline. Berrett-Koehler, San Francisco, CA, pp. 241-258, 2003.

McCaffer, R., Editorial, Engineering Const. & Arch. Mgmt., Vol. 15(4), 2008.

Mintzberg, H., The manager's job: folklore and fact, Harv. Bus. Rev., Mar-Apr., 172-5, 1990.

Ofori, G., Improving the performance of contractors in developing countries: A review of

programmes and approaches. Construction Management and Economics, 9, 19-38, 1991.

Ofori, G., The construction industries in developing countries. In Ofori, G. (Ed.) New

Perspectives on Construction in Developing Countries. Abingdon: Spon, pp. 1-16, 2012.

Rothstein, H.R., Schmidt, F.L., Erwin, F.W., Owens, W.A., and Sparks, C.R., Biographical data

in employment selection: Can validities be made generalizable? Journal of Applied

Psychology, 75, 175-184, 1990.

Rowlinson, S., Ho, K.K. and Ph-Hung, Y., Leadership style of construction managers in Hong

Kong, Const. Mgmt. & Econs., Vol. 11(6), pp. 455-65, 1993.

Russell, J.S., Doll, N., Orner, K. and Sullivan, G. Leading with heart in the construction

industry: preparing level 5 leaders at UWMadison, Paper presented at Center for Project

Leadership Forum, New York, 2006.

Shakantu, W., Contractor development. In Ofori, G. (Ed.) New Perspectives on Construction

in Developing Countries. Abingdon: Sage, pp. 253-281, 2012.

Strauss, A., and Corbin, J., Basics of qualitative research: Grounded theory procedures and

techniques, Newbury Park, CA: Sage, 1990.

Proceedings EPOC 2012 Conference

15

Taylor, F.W., Principles of Scientific Management. Harper, New York, 1911.

Toor, S. R. and Ofori, G., Leadership vs. Management: How they are different, and why!

Journal of Leadership and Management in Engineering, 8(2), 61-71, 2008a.

Toor, S. R. and Ofori, G., Taking leadership research into future: A review of empirical studies

and new directions for research, Eng., Const. & Arch. Mgmt., Vol. 15(4), pp. 352-371,

2008b.

United Nations Centre for Human Settlements, Policies and Measures for Small-Contractor

Development in the Construction Industry. HS/375/95E, Nairobi, 1996.

Vroom, V.H. and Jago, A.G., The role of situation in leadership. American Psychologist, 62,

17-24, 2007.

Walumbwa, F.O., Avolio, B.J., Gardner, W.L., Wernsing, T. and Peterson, S.J., Authentic

leadership: development and validation of a theory-based measure, Journal of Mgmt., Vol.

34(1), pp. 89-126, 2008.

Yukl, G., Leadership in Organizations, 5th Edn., Upper Saddle Creek, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 2002.

Zaleznik, A., Managers and leaders: Are they different? Harvard Business Review, Vol. 55(3),

67-78, 1977.

Você também pode gostar

- The Future Path of SMEs: How to Grow in the New Global EconomyNo EverandThe Future Path of SMEs: How to Grow in the New Global EconomyAinda não há avaliações

- 15 1259 Nader Nada Innovation and Knowledge Management Practices in Turkish SmesDocumento18 páginas15 1259 Nader Nada Innovation and Knowledge Management Practices in Turkish SmesMuhammed AydınAinda não há avaliações

- 外文原文-2017aiet- 20174223079061 -Benson Emediong MondayDocumento12 páginas外文原文-2017aiet- 20174223079061 -Benson Emediong MondayEmediong BensonAinda não há avaliações

- Harnessing KnowledgeDocumento14 páginasHarnessing KnowledgeHina SaadAinda não há avaliações

- The Role of HRM in Leadership Development, Talent Retention, Knowledge Management, and Employee EngagementDocumento20 páginasThe Role of HRM in Leadership Development, Talent Retention, Knowledge Management, and Employee EngagementAnonymous VvPU8jG44Ainda não há avaliações

- Importance of Leadership in AdministrationDocumento10 páginasImportance of Leadership in AdministrationYasminAinda não há avaliações

- IJEIM2018 ScaringellaDocumento24 páginasIJEIM2018 ScaringellaAequiraAinda não há avaliações

- Leadership Styles in Project Management: January 2016Documento11 páginasLeadership Styles in Project Management: January 2016EDEN2203Ainda não há avaliações

- Entrepreneurial Management and Leadership (Eml) : Workbook / Study GuideDocumento40 páginasEntrepreneurial Management and Leadership (Eml) : Workbook / Study GuideOmar Dennaoui100% (1)

- How To Apply Responsible Leadership Theory in PracticeDocumento21 páginasHow To Apply Responsible Leadership Theory in PracticeSaniya FayazAinda não há avaliações

- Entrepreneurship Education and Research Emerging TDocumento13 páginasEntrepreneurship Education and Research Emerging TImran MushtaqAinda não há avaliações

- Group 1 Leadership - Proposal 1Documento36 páginasGroup 1 Leadership - Proposal 1Azura RavenclawAinda não há avaliações

- Transformational Vs TransactionalDocumento4 páginasTransformational Vs TransactionalZul100% (2)

- Chapter 1Documento11 páginasChapter 1Ahmad AriefAinda não há avaliações

- The Ambidextrous OrganizationDocumento10 páginasThe Ambidextrous OrganizationKewin KusterAinda não há avaliações

- Business ExcellenceDocumento19 páginasBusiness ExcellenceKule89Ainda não há avaliações

- Management Development and OrganizationalDocumento10 páginasManagement Development and OrganizationalFendri PranantaAinda não há avaliações

- The Evolutionary Model of Corporate Entrepreneurship: A Case Study of Samsung Creative-LabDocumento23 páginasThe Evolutionary Model of Corporate Entrepreneurship: A Case Study of Samsung Creative-LabAdarsh BhandariAinda não há avaliações

- 2011 Schilo Entrepreneurial Orientation and PerformanceDocumento6 páginas2011 Schilo Entrepreneurial Orientation and Performancechiraz ben salemAinda não há avaliações

- The Impact of Leadership Style On Employee Job Satisfaction: September 2014Documento21 páginasThe Impact of Leadership Style On Employee Job Satisfaction: September 2014Mohammad Ali DhamrahAinda não há avaliações

- Rae2012 PDFDocumento17 páginasRae2012 PDFValter EliasAinda não há avaliações

- Leveraging The Differences: A Case of Reverse MentoringDocumento16 páginasLeveraging The Differences: A Case of Reverse MentoringJAMUNA SHREE PASUPATHIAinda não há avaliações

- Leveraging The Differences: A Case of Reverse MentoringDocumento16 páginasLeveraging The Differences: A Case of Reverse MentoringAanya SinhaAinda não há avaliações

- Authentic Leadership in Construction IndustryDocumento11 páginasAuthentic Leadership in Construction Industryabsoluto_1100% (1)

- Leadership Challenges of Today's Managers - Overview of Approaches and A Study in RomaniaDocumento6 páginasLeadership Challenges of Today's Managers - Overview of Approaches and A Study in RomaniaFlori MarcociAinda não há avaliações

- 21st Century Leadership Michael LorzDocumento16 páginas21st Century Leadership Michael LorzRakesh KumarAinda não há avaliações

- Ay Lee Chapter 1Documento9 páginasAy Lee Chapter 1banjosegun99Ainda não há avaliações

- Contentserver AspDocumento16 páginasContentserver Aspapi-267826685Ainda não há avaliações

- El - Creative (Ukm It)Documento13 páginasEl - Creative (Ukm It)No Limit ClubAinda não há avaliações

- Essential Competencies For The Supervisors of Oil and Gas Industrial CompaniesDocumento8 páginasEssential Competencies For The Supervisors of Oil and Gas Industrial CompaniesHadi JamshidiAinda não há avaliações

- The Effects of Leadership Styles On Employee Performance - Case Study: Istanbul - Turkey Sme'sDocumento9 páginasThe Effects of Leadership Styles On Employee Performance - Case Study: Istanbul - Turkey Sme'sPaper PublicationsAinda não há avaliações

- 1.2-Competencias Del Emprendedor - Rezaeizadeh2016Documento39 páginas1.2-Competencias Del Emprendedor - Rezaeizadeh2016steve guachamin v:Ainda não há avaliações

- Critical Success Factors For KM ImplementationDocumento8 páginasCritical Success Factors For KM Implementationsagar58Ainda não há avaliações

- Responsible Leadership, Stakeholder Engagement, and The Emergence of Social CapitalDocumento15 páginasResponsible Leadership, Stakeholder Engagement, and The Emergence of Social CapitalMichael OkwaraAinda não há avaliações

- Business Development Capability: Insights From The Biotechnology IndustryDocumento16 páginasBusiness Development Capability: Insights From The Biotechnology IndustryDiana CadahingAinda não há avaliações

- Challenges in Knowledge Management InsigDocumento19 páginasChallenges in Knowledge Management InsigMitchum BaneyAinda não há avaliações

- Leadership in The Construction Industry 2008Documento24 páginasLeadership in The Construction Industry 2008Gishan SanjeewaAinda não há avaliações

- A Comparison of Personal Entrepreneurial Competences Between Entrepreneurs and Ceos in Service SectorDocumento15 páginasA Comparison of Personal Entrepreneurial Competences Between Entrepreneurs and Ceos in Service SectorRaluca NegruAinda não há avaliações

- Responsible LeadershipDocumento3 páginasResponsible LeadershipusmanrehmatAinda não há avaliações

- CE Challenge For Educators Kuratko 2018Documento19 páginasCE Challenge For Educators Kuratko 2018Rendika NugrahaAinda não há avaliações

- IJREISSDr PadmaMisraPaperDocumento10 páginasIJREISSDr PadmaMisraPaperAustine livinusAinda não há avaliações

- Corporate EntrepreneurshipDocumento37 páginasCorporate EntrepreneurshipAman deepAinda não há avaliações

- Theory X and Theory Y Type Leadership Behavior and Its Impact On Organizational Performance: Small BusinessDocumento9 páginasTheory X and Theory Y Type Leadership Behavior and Its Impact On Organizational Performance: Small BusinessYeidy AcostaAinda não há avaliações

- Principle of ManagementDocumento144 páginasPrinciple of Management5071 NithishAinda não há avaliações

- A Case Study of Xiaomi: Design Management Capability in EntrepreneurshipDocumento14 páginasA Case Study of Xiaomi: Design Management Capability in EntrepreneurshiporokAinda não há avaliações

- 10 1108 - Ijebr 07 2021 0528Documento25 páginas10 1108 - Ijebr 07 2021 0528nishita.shastriAinda não há avaliações

- Sustainability and The Need For Change Organizational Change and Transformational VisionDocumento13 páginasSustainability and The Need For Change Organizational Change and Transformational VisionanamariaonicescuAinda não há avaliações

- Entrepreneurial Mindset of Information and Communication Technology FirmsDocumento21 páginasEntrepreneurial Mindset of Information and Communication Technology FirmsSiti Zalina Mat HussinAinda não há avaliações

- Age Research VariableDocumento7 páginasAge Research VariableMae Irish Joy EspinosaAinda não há avaliações

- Admsci 08 00018 v2 PDFDocumento15 páginasAdmsci 08 00018 v2 PDFconteeAinda não há avaliações

- فعالية القيادة الاستراتيجيةDocumento14 páginasفعالية القيادة الاستراتيجيةnour zolfakarAinda não há avaliações

- Entrepreneurship and The Strategic Transformation of Medium and Small EnterprisesDocumento5 páginasEntrepreneurship and The Strategic Transformation of Medium and Small EnterprisesKlara KlaraAinda não há avaliações

- Strategy As Evolution With Design: The Foundations of Dynamic Capabilities and The Role of Managers in The Economic SystemDocumento22 páginasStrategy As Evolution With Design: The Foundations of Dynamic Capabilities and The Role of Managers in The Economic SystemThiagoAinda não há avaliações

- 329-Article Text-605-1-10-20210819Documento18 páginas329-Article Text-605-1-10-20210819AnupAinda não há avaliações

- 1 s2.0 S095965261933553X MainDocumento14 páginas1 s2.0 S095965261933553X MainmadesriAinda não há avaliações

- Corporate Entrepreneurship and Entrepreneurial Orientation: The Impact On Managing Capabilities For InnovationDocumento7 páginasCorporate Entrepreneurship and Entrepreneurial Orientation: The Impact On Managing Capabilities For InnovationMauroAinda não há avaliações

- 2013 - Leadership and Risk-Taking Propensity Among Entrepreneurs in MsiaDocumento9 páginas2013 - Leadership and Risk-Taking Propensity Among Entrepreneurs in MsiajajaikamaruddinAinda não há avaliações

- G 13 9 Strategic Leadership Effectiveness-With-Cover-Page-V2Documento15 páginasG 13 9 Strategic Leadership Effectiveness-With-Cover-Page-V2Ayesha Shareef (Anshoo)Ainda não há avaliações

- Obafemi Awolowo: Leadership in Perspective: BS4S16 Leadership & Management TheoriesDocumento32 páginasObafemi Awolowo: Leadership in Perspective: BS4S16 Leadership & Management Theoriesjohn stone100% (1)

- The Reality of Corporate Social Responsibility in Small and Medium EnterprisesDocumento4 páginasThe Reality of Corporate Social Responsibility in Small and Medium EnterprisesInternational Jpurnal Of Technical Research And ApplicationsAinda não há avaliações

- Buildings Department Practice Note For Registered Contractors 29Documento3 páginasBuildings Department Practice Note For Registered Contractors 29absoluto_1Ainda não há avaliações

- APP002Documento19 páginasAPP002absoluto_1Ainda não há avaliações

- Factors Affecting Cost Performance of Construction in IndiaDocumento84 páginasFactors Affecting Cost Performance of Construction in Indiaabsoluto_1Ainda não há avaliações

- Authentic Leadership in Construction IndustryDocumento11 páginasAuthentic Leadership in Construction Industryabsoluto_1100% (1)

- Step Kelley DavisDocumento21 páginasStep Kelley Davisapi-626701108Ainda não há avaliações

- 102 2019 0 BDocumento22 páginas102 2019 0 BMatome100% (2)

- Mike Abed: Sales Director, Software DivisionDocumento1 páginaMike Abed: Sales Director, Software DivisionAndres DussanAinda não há avaliações

- Psychosocial Support PlanDocumento2 páginasPsychosocial Support PlanGwendolyn Lalamonan AnganaAinda não há avaliações

- © 2007 The Mcgraw-Hill Companies, Inc. All Rights ReservedDocumento38 páginas© 2007 The Mcgraw-Hill Companies, Inc. All Rights Reservedbly789Ainda não há avaliações

- Teachers Observing Teachers - A Professional Development Tool For Every SchoolDocumento5 páginasTeachers Observing Teachers - A Professional Development Tool For Every SchoolRubens ViegasAinda não há avaliações

- The Role of A Leader in Contemporary Organizations: Dorota BalcerzykDocumento15 páginasThe Role of A Leader in Contemporary Organizations: Dorota BalcerzykALALADE VICTOR aAinda não há avaliações

- Ifx Final EvaluationDocumento7 páginasIfx Final Evaluationapi-284751376Ainda não há avaliações

- 7-Lessons To Building Coaching PracticeDocumento12 páginas7-Lessons To Building Coaching PracticeAlex Maric Dragas100% (1)

- Institute For Tourism, Travel and Culture B.A. (Hons) Tourism Studies Industry Placement 2Documento7 páginasInstitute For Tourism, Travel and Culture B.A. (Hons) Tourism Studies Industry Placement 2JosefBaldacchinoAinda não há avaliações

- On The Role of Emotional Intelligence in OrganizationsDocumento20 páginasOn The Role of Emotional Intelligence in OrganizationsDontNagAinda não há avaliações

- Remote Manager Survival Guide 2023Documento60 páginasRemote Manager Survival Guide 2023Cristina Bianca LeãoAinda não há avaliações

- Capstone LogDocumento4 páginasCapstone Logapi-574512330Ainda não há avaliações

- CLC ProposalDocumento10 páginasCLC Proposalapi-479963734Ainda não há avaliações

- Writing 1.2Documento7 páginasWriting 1.2Nam NguyễnAinda não há avaliações

- Tutorial Letter 103/0/2023Documento41 páginasTutorial Letter 103/0/2023MishumoAinda não há avaliações

- Assessing Law Firm 2010Documento17 páginasAssessing Law Firm 2010zzwayAinda não há avaliações

- Business Plan 2017 - 2019: Kalamunda Senior High SchoolDocumento28 páginasBusiness Plan 2017 - 2019: Kalamunda Senior High SchoolAxel CabornayAinda não há avaliações

- The Automotive Engineering Business and IndustryDocumento9 páginasThe Automotive Engineering Business and Industryapi-251200366Ainda não há avaliações

- Emsd Pgde Lesson FourDocumento10 páginasEmsd Pgde Lesson FourCharleneAinda não há avaliações

- Master Teachers Actual Target Setting For SY 2022 2023Documento7 páginasMaster Teachers Actual Target Setting For SY 2022 2023mhine dy100% (2)

- Teacher Self-Efficacy Profiles-Determinants, Outcomes, and Generalizability Across Teaching LevelDocumento18 páginasTeacher Self-Efficacy Profiles-Determinants, Outcomes, and Generalizability Across Teaching LevelMichelle PajueloAinda não há avaliações

- 3D CreativeDocumento70 páginas3D Creativebeebake100% (6)

- Rich With GratitudeDocumento63 páginasRich With Gratitudeselva100% (1)

- Department of Education: Annual Implementation PlanDocumento14 páginasDepartment of Education: Annual Implementation PlanRoy Bautista Manguyot100% (3)

- S6 - 2 - FIDIC GAMA Conference - J Rachmund - Bridging The Gap - PresentationDocumento15 páginasS6 - 2 - FIDIC GAMA Conference - J Rachmund - Bridging The Gap - PresentationDiadieAinda não há avaliações

- The Learning Zone ModelDocumento6 páginasThe Learning Zone ModelShosho NasraweAinda não há avaliações

- Alumni Dissertation Award Penn StateDocumento8 páginasAlumni Dissertation Award Penn StateCustomWrittenPaperSingapore100% (1)

- The Girl BrandDocumento48 páginasThe Girl BrandMoses MaiAinda não há avaliações

- Kelchtermans and Deketelaere 2016 The Emotional Dimension in Becoming A TeacherDocumento33 páginasKelchtermans and Deketelaere 2016 The Emotional Dimension in Becoming A TeacherJaime UlloaAinda não há avaliações