Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Research Paper With in Text Citations

Enviado por

api-254664546Título original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Research Paper With in Text Citations

Enviado por

api-254664546Direitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Running head: Adolescent Acne 1

Adolescent Acne

Jocelyn Vazquez

PED 105- 201 Integrated Health and Physical Education

Running head: Adolescent Acne 2

Abstract

Acne vulgaris is a common skin disorder of the sebaceous follicles. There are a number

of different reasons as to what triggers acne. Other factors such as diet have been

associated with the cause, but not proven. Acne can continue into adulthood, with

damaging effects on self-esteem. The purpose of the research paper is to inform readers

on the importance of smart, dietary choices and how it can prevent physical and

emotional damage to an adolescent.

Running head: Adolescent Acne 3

The adolescent years are a time of physical, psychological, and social changes

(Hedden, Davidson, & Smith, 2008). During this time, the adolescent begins to form a

sense of identity. Self- esteem plays a major role during this transition. It is during this

period of identity formation that positive or negative influences upon self-esteem can

cause long-term effects. Acne is a prime example of a negative influence with which

adolescents are often faced. By eating healthy foods and consuming adequate amounts of

water, a teenager is less likely to have severe acne.

Acne is a disorder of the sebaceous glands and hair follicles (Hedden, Davidson,

& Smith, 2008). Acne appears when the follicles become congested with excess oil

(Hedden, Davidson, & Smith, 2008). There are different forms of acne such as white and

blackheads to nodules or cysts (Gazella, 2007). Pimples occur when bacteria grow on the

skin resulting in the non-inflammatory and inflammatory lesions. The exact cause is

indistinguishable, but it is believed to result from a combination of different factors such

as genetics, hormones, stress, hygiene and diet (Gazella, 2007).

The connection between diet and acne is still debatable (Williams, Dellavalle, &

Garner, 2012). According to The American Academy of Dermatology acne is not related

to diet. However, it also mentions that if a person feels that certain foods flare the acne,

and then they should avoid eating that type of food. Other studies have concluded that

diet does play a role in acne formation.

Many studies have shown that dairy products can irritate or cause acne. Studies

have shown that high milk consumption aggravates by increasing the insulin/IGF-1

signaling (Kumari & Thappa, 2013). Occurrence of acne as part of various syndromes

associated with insulin resistance also provides evidence in favor of correlation between

Running head: Adolescent Acne 4

IGF-1 and acne. Recent studies have shown that higher levels of serum insulin-like

growth factor-I (IGF-I) correlate with overproduction of sebum and acne (Kumari &

Thappa, 2013). A 2006 Harvard study found that girls who drank two or more glasses of

milk daily had about a 20% higher risk of acne than those who had less than a glass a

week (Shaffer, 2013). It is important to determine dietary acne triggers, which usually

vary from each person.

Sugars glucose is the bodys basic energy source and is present in the blood.

According to Science World (2003) glucose comes from digestion of carbohydrate

containing foods in the small intestine. Starchy foods and sugary foods contain glucose.

Once the glucose is digested, it moves rapidly from the intestines into the blood. As the

blood glucose level rises the pancreas creates a hormone called insulin (Science World,

2003). If blood glucose levels are rapidly rising after consuming high GI foods, then large

quantities of insulin are constantly being released into the blood.

The over-production of insulin is believed to affect many other hormones, some

of which are connected to acne. For example, high levels of insulin may cause androgens

(the male hormones) to become more active in both males and females (Moyer, 1999).

Androgens are known regulators of sebum production (Moyer, 1999). Insulin can also

promote growth of keratin in skin cells, which can cause the follicles to become blocked.

With a blocked duct the excess oily sebum cannot escape onto the skin surface, as it

should. It builds up in the duct and skin and bacteria grows rapidly in the duct using the

sebum as food. This is infection and leads to redness and swelling called inflammation.

Running head: Adolescent Acne 5

In a 2007 study, Australian researchers found that people who followed a low-

glycemic index diet had a 22% decrease in acne lesions, compared with a control group

that ate more high-GI foods (Shafer, 2013). Scientists suspect that raised insulin levels

from the carbs may trigger a release of hormones that inflame follicles and increase oil

production. When people eat simple carbohydrates, the pancreas secretes insulin, a

hormone that helps muscle cells absorb sugar. Insulin also stimulates the skin to produce

sebum. The consumption of simple-carbohydrate foods may be harmful to the skin.

Doctors also suspect that sodium can also cause acne. The iodine found in table

salt and some seafood may worsen acne breakouts. Its best to stick to low sodium

versions of packaged foods, and keep your overall salt consumption below 1,500 mg a

day (Shafer, 2013).

Food allergies can also cause acne. Food allergens that can contribute to acne

include refined carbohydrates, nuts, and chocolate (Gazella, 2007). It may be the milk

and sugar in chocolate that causes acne, not the chocolate itself. All forms of refined

carbohydrates, especially soda, have been shown to contribute to acne. Foods such as

bread, chips, processed flour, and food that contain trans and hydrogenated fats are likely

to cause acne (Gazella, 2007).

A diet that contains organic vegetables, fresh fish, and low-fat, high- fiber foods

will help control acne (Mann, 2007). Its also best to drink eight, 8-ounce glasses of water

daily in order to stay hydrated.

Dietary supplements are available to provide anti-acne nutrients and help balance

a healthful diet. Some important anti-acne nutrients are zinc, flaxseed and borage oil, and

vitamins A, B6, and C. Vitamins C and A are important for healthy looking skin (Siegel-

Running head: Adolescent Acne 6

Maier, 2000). Vitamin C is used to produce collagen and elastin. Vitamin A enables to

the skin to eliminate waste from sweat and oil glands. Natural sources rich in these

vitamins include broccoli, kale, spinach, bananas, carrots, and tomatoes. Protein

nourishes the skin with amino acids that help the skin to heal and renew itself.

The B vitamins are also important to maintain skin health. B-6 is very helpful to

young women who experience premenstrual acne flare-ups, since it helps to prevent

water retention. The best sources for B vitamins are cereals and whole grains.

Its best to avoid or limit refined carbohydrates, foods high in saturated fats,

excessive amounts of iodized salt and, shellfish due to their iodine content. It's not a good

idea to mega-dose with vitamin supplements either. Many teens try to clear their skin by

taking large amounts of vitamin A or the B vitamins. Unfortunately, not only can this

aggravate acne, it can also harm the body. By taking a general once-a-day multivitamin

and eating a well balanced diet, will help make sure that you're getting all the nutrients

needed for healthy looking skin.

According to Biotech Business Week (2008), Almost 85 percent of teens

experience acne at some point during their adolescent years. A recent survey found that

nearly 40 percent of teens avoided going to school because they were embarrassed by

acne (Barone, 1996). Almost a third indicated that their acne prevented them from

making friends (Barone, 1996). Unfortunately the skin condition can cause feelings of

anger, depression and frustration. By making the proper dietary choices, it is less likely

for a teenager to have severe acne.

Running head: Adolescent Acne 7

References:

Acne vulgaris; new talking acne with your teen campaign offers advice to moms on how

to help kids start the school year with clearer skin. (2008). Biotech Business Week, , 1468.

Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/236197093?accountid=10071

Barone, P. (1996). Psychological effects of acne on adults, teens can prove to be

devastating. Dermatology Times, 17(9), S6.

Gazella, K. A. (2007). prescription for clear skin. Better Nutrition, 69(10), 46.

Hedden, S. L., Davidson, S., & Smith, C. B. (2008). Cause and effect: The relationship

between acne and self-esteem in the adolescent years. The Journal for Nurse

Practitioners, 4(8), 595-600. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.nurpra.2008.01.021

Kumari, R., & Thappa, D. (2013). Role of insulin resistance and diet in acne. Indian

Journal of Dermatology, Venereology and Leprology, 79(3), 291-9.

doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.4103/0378-6323.110753

Mann, N., & Smith, R. (2007). SPOTTING THE PROBLEM--DOES DIET PLAY A

ROLE IN ACNE? (cover story). Nutridate, 18(2), 1-4.

Moyer, P. (1999). Androgen excess known to cause male, as well as female, acne.

Dermatology Times, 20(11), 42.

Shaffer, A. (2013). Problem Solved! Adult Acne. Prevention, 65(8), 56.

Siegel-Maier, K. (2000). The `secrets' of all-natural pimple protection. Better Nutrition,

62(1), 64.

Running head: Adolescent Acne 8

Williams, H. C., Dellavalle, R. P., & Garner, S. (2012). Acne vulgaris. The Lancet,

379(9813), 361-72. Retrieved from

http://search.proquest.com/docview/920097495?accountid=10071

ZITS: DIET. (2003). Science World, 59(9/10), 30.

Você também pode gostar

- PQ Inventory Jocelyn Vazquez Fall 2014Documento1 páginaPQ Inventory Jocelyn Vazquez Fall 2014api-254664546Ainda não há avaliações

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- Education:: 8359 Ocean Gateway, Easton, MD 21601Documento1 páginaEducation:: 8359 Ocean Gateway, Easton, MD 21601api-254664546Ainda não há avaliações

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5794)

- Graphic OrganizerDocumento4 páginasGraphic Organizerapi-254664546Ainda não há avaliações

- Lab Report EnzymesDocumento7 páginasLab Report Enzymesapi-254664546Ainda não há avaliações

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (400)

- PQ Inventory Jocelyn Vazquez Fall 2014Documento2 páginasPQ Inventory Jocelyn Vazquez Fall 2014api-254664546Ainda não há avaliações

- Speaker FormDocumento2 páginasSpeaker Formapi-254664546Ainda não há avaliações

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- AcneDocumento13 páginasAcneapi-254664546Ainda não há avaliações

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- Ball ScrambleDocumento3 páginasBall Scrambleapi-254664546Ainda não há avaliações

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (895)

- Brochure - ILLUCO Dermatoscope IDS-1100Documento2 páginasBrochure - ILLUCO Dermatoscope IDS-1100Ibnu MajahAinda não há avaliações

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- Dando Watertec 12.8 (Dando Drilling Indonesia)Documento2 páginasDando Watertec 12.8 (Dando Drilling Indonesia)Dando Drilling IndonesiaAinda não há avaliações

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- Thorley Amended Complaint (Signed)Documento13 páginasThorley Amended Complaint (Signed)Heather ClemenceauAinda não há avaliações

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- MPERSDocumento1 páginaMPERSKen ChiaAinda não há avaliações

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (266)

- RMP ContractDocumento181 páginasRMP ContractHillary AmistosoAinda não há avaliações

- Metallurgical Test Report: NAS Mexico SA de CV Privada Andres Guajardo No. 360 Apodaca, N.L., C.P. 66600 MexicoDocumento1 páginaMetallurgical Test Report: NAS Mexico SA de CV Privada Andres Guajardo No. 360 Apodaca, N.L., C.P. 66600 MexicoEmigdio MartinezAinda não há avaliações

- OM Hospital NEFTDocumento1 páginaOM Hospital NEFTMahendra DahiyaAinda não há avaliações

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- Plumbing Breakup M 01Documento29 páginasPlumbing Breakup M 01Nicholas SmithAinda não há avaliações

- MCQ Homework: PeriodonticsDocumento4 páginasMCQ Homework: Periodonticsفراس الموسويAinda não há avaliações

- BUERGER's Inavasc IV Bandung 8 Nov 2013Documento37 páginasBUERGER's Inavasc IV Bandung 8 Nov 2013Deviruchi GamingAinda não há avaliações

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (345)

- Tetra Pak Training CatalogueDocumento342 páginasTetra Pak Training CatalogueElif UsluAinda não há avaliações

- 21 05 20 Montgomery AssocDocumento1 página21 05 20 Montgomery AssocmbamgmAinda não há avaliações

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2259)

- Tcu Module Pe1 Lesson 1Documento7 páginasTcu Module Pe1 Lesson 1Remerata, ArcelynAinda não há avaliações

- Legg Calve Perthes Disease: SynonymsDocumento35 páginasLegg Calve Perthes Disease: SynonymsAsad ChaudharyAinda não há avaliações

- Beckhoff Service Tool - USB StickDocumento7 páginasBeckhoff Service Tool - USB StickGustavo VélizAinda não há avaliações

- Aplikasi Metode Geomagnet Dalam Eksplorasi Panas BumiDocumento10 páginasAplikasi Metode Geomagnet Dalam Eksplorasi Panas Bumijalu sri nugrahaAinda não há avaliações

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- An Energy Saving Guide For Plastic Injection Molding MachinesDocumento16 páginasAn Energy Saving Guide For Plastic Injection Molding MachinesStefania LadinoAinda não há avaliações

- Практичне 25. Щодений раціонDocumento3 páginasПрактичне 25. Щодений раціонAnnaAnnaAinda não há avaliações

- Metabolism of Carbohydrates and LipidsDocumento7 páginasMetabolism of Carbohydrates and LipidsKhazel CasimiroAinda não há avaliações

- E10b MERCHANT NAVY CODE OF CONDUCTDocumento1 páginaE10b MERCHANT NAVY CODE OF CONDUCTssabih75Ainda não há avaliações

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (121)

- 2020 Q2 CushWake Jakarta IndustrialDocumento2 páginas2020 Q2 CushWake Jakarta IndustrialCookiesAinda não há avaliações

- Argumentative Essay Research PaperDocumento5 páginasArgumentative Essay Research PaperJadAinda não há avaliações

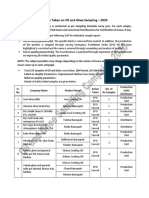

- Action Taken On Oil and Ghee Sampling - 2020Documento2 páginasAction Taken On Oil and Ghee Sampling - 2020Khalil BhattiAinda não há avaliações

- E-Kabin - O Series - Monoblock Enclosure - ENGDocumento12 páginasE-Kabin - O Series - Monoblock Enclosure - ENGCatalina CocoşAinda não há avaliações

- TM - 1 1520 237 10 - CHG 10Documento841 páginasTM - 1 1520 237 10 - CHG 10johnharmuAinda não há avaliações

- Roto Fix 32 Service ManualDocumento31 páginasRoto Fix 32 Service Manualperla_canto_150% (2)

- Buss 37 ZemaljaDocumento50 páginasBuss 37 ZemaljaOlga KovacevicAinda não há avaliações

- Tiếng AnhDocumento250 páginasTiếng AnhĐinh TrangAinda não há avaliações

- Aromatic Electrophilic SubstitutionDocumento71 páginasAromatic Electrophilic SubstitutionsridharancAinda não há avaliações

- Bitumen BasicsDocumento25 páginasBitumen BasicsMILON KUMAR HOREAinda não há avaliações