Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Pjbabefshe

Enviado por

simphiwe80430 notas0% acharam este documento útil (0 voto)

19 visualizações7 páginasExcellence

Título original

pjbabefshe

Direitos autorais

© © All Rights Reserved

Formatos disponíveis

PDF, TXT ou leia online no Scribd

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoExcellence

Direitos autorais:

© All Rights Reserved

Formatos disponíveis

Baixe no formato PDF, TXT ou leia online no Scribd

0 notas0% acharam este documento útil (0 voto)

19 visualizações7 páginasPjbabefshe

Enviado por

simphiwe8043Excellence

Direitos autorais:

© All Rights Reserved

Formatos disponíveis

Baixe no formato PDF, TXT ou leia online no Scribd

Você está na página 1de 7

The Australian Business Excellence Framework:

A Framework For Small Horticultural Enterprises

Peter Bryar

Research Student

Centre for Management Quality Research

RMIT University

Bundoora West Campus

PO Box 71

BUNDOORA VIC 3083 Australia

Tel: + 61 3 9925 7695

Fax: + 61 3 9925 7696

Email: Peter.Bryar@rmit.edu.au

Abstract

The Australian Business Excellence Framework was first introduced in 1987, in order to help Australian

enterprises meet the challenges of the global market. Since that time it has undergone regular update and

re-development. The framework is an organisational tool which operationalises proven principles and

focuses on seven critical success categories. It provides the means of introducing business improvement

methodologies across all aspects of an enterprise.

It was thought that the excellence framework may provide a useful vehicle for small horticultural

enterprises to focus on their business fundamentals.

Key Words and Phrases

Australian Business Excellence Framework (ABEF), Small Horticultural Enterprises (SHE)

Introduction

Many small horticultural enterprises are

searching for ways of improving what they do.

Although Australian horticulturalists are

amongst the most efficient in the world they are

still searching for productivity and process

improvement gains. More often than not the

improvement focus has been towards breeding

more productive plant varieties, better soil

management, the introduction of sustainable

agricultural practices, improved mechanisation

and the development and more efficient use of

farm chemicals. However, there has been little

focus on the business itself. It was thought that

the excellence framework may provide a useful

vehicle for these enterprises to focus on their

business fundamentals.

This paper firstly reviews the categories of

assessment within the framework in the context

of small businesses. It then considers the

application of the framework against three case

study small horticultural enterprises.

The three case study enterprises became

interested in this study following third party

quality certification. Now that they felt

comfortable with their efforts towards

improving their operational processes, they had

expressed interest in dealing with other aspects

of their business, particularly those that which

might lead to improved bottom line

performance. They were also interested in

comparing their business management functions

with small businesses in other sectors without

going through a formal benchmarking process.

The final part of the paper is an assessment of

small business characteristics and whether the

framework takes these into account.

Research Method

A case study approach using qualitative methods

was applied to this research. The excellence

framework was explained to the proprietor of

each of the selected third party certified case

study enterprises. This was followed by a

structured discussion designed to determine the

relevance and application of the framework to

their own organisation.

Business Excellence In Australia

The ABEF is designed to help businesses

explore their own organisational beliefs and

strategies, to look for linkages and measurable

activity, and to test results for long-term success.

The framework links to similar models around

the world and contains all of the requirements of

the 2000 ISO 9000 series standards.

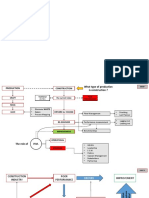

The seven categories of the model, as shown in

figure 1, can be applied to all organisations

irrespective of size. Organisations can use the

framework to assess themselves and build those

results into their strategic planning processes.

Figure 1 The Australian Business Excellence

Framework

Category 1 - Leadership and I nnovation. This

category explores how leadership uses the

principles underpinning the framework. It

examines how management practice and

behaviour are linked to those principles and how

their application has become a part of daily life.

Category 2 Strategy and Planning Process.

This category explores the way the organisation

develops its strategies and plans, and how it

deploys them.

Category 3 Data, I nformation and

Knowledge. This category examines how the

organisation obtains and uses data, information

and knowledge to support decision-making at all

levels of the enterprise.

Category 4 People. This category explores the

way in which all people are encouraged and

enabled to make a personally satisfying

contribution to the achievement of the

organisations goals.

Category 5 Customer and Market Focus.

This category addresses the way in which the

organisation analyses its customers and markets,

and how it reflects the needs of its current and

future external customers in all its activities.

Category 6 Processes, Products and Services.

This category examines the processes the

organisation uses to supply quality products and

services to its customers, and the processes used

to improve those products and services.

Category 7 Business Results. The intent of

this category is to demonstrate the performance

of the organisation to date and, by using

appropriate measures, to envision its success

into the future. It provides an opportunity to

pull together the strands of the holistic

management described in the first six categories

and to illustrate how management initiatives are

contributing to demonstrably superior

performance and the achievement of the

organisations purpose, vision and goals.

The excellence framework covers the elements

of total quality and is consistent with

international models like the Malcolm Baldridge

National Quality Awards and the European

Quality Awards.

The management system can be scored out of

1000 points. Scores are only one of the factors

taken into account in determining whether an

applicant will be recognised for a level of

business excellence.

At this time none of the three case study

enterprises had expressed a desire to apply for

an award. When informed that many other

organisations used the process for self-

assessment against the framework, they felt that

it might be worthwhile for them to review their

relative scores if only to determine the areas of

weaknesses in their businesses and to plan for

potential improvements. Even at this early stage

they felt that all the categories of the framework

were relevant to their business.

Applying The Australian Business

Excellence Framework To SHE

To be eligible for the small enterprise section,

organisations must directly employ between 7

and 100 full-time staff. A business with less

than 7 employees may still be eligible but would

need to provide grounds for exemption from this

requirement. The organisation must be fully

autonomous and exercise the full range of

management responsibilities appropriate to its

operations. Clearly the majority of businesses

like the case study enterprises will have

difficulty in meeting this criterion as they

generally employ, on a full-time basis, one or

two people (often husband in the paddock and

wife in the packing shed) and a few casuals

during harvest / packing operations only.

The Administrative Process of

Application

The administrative process of application was

perceived to be somewhat daunting by the case

study enterprises:

Having no prior knowledge of the awards

they did not know where to start.

They were not aware that the Australian

Quality Council (AQC) managed the

process and could assist them with their

application. In fact they were not aware

that the AQC actually existed.

Once the relevant information was obtained,

enterprises were then expected to self-

assess against the framework. Before doing

so, businesses must have attended an

awards information seminar.

The written application form is then

completed ensuring that each question is

answered. Any additional information is

attached and referenced.

The case study enterprises had not heard of the

excellence framework but when explained to

them, they felt somewhat positive towards the

objectives of the awards. However, they

thought that the costs, time and resource

requirement associated with the process as being

prohibitive. The actual construction of the

written application was also a concern for them

English is often a second language for many

horticulturalists in Victoria. Whilst still

remaining fairly positive towards the awards

they felt that the framework was probably more

suited to organisations with a larger

infrastructure and perhaps those operating

within the traditional manufacturing or service

industries.

Their final anxiety related to what they would

get out of the awards process as a business.

Recognition (self or public) was of little concern

to them and now that they had third party

certified food safety and quality systems in

place, they thought it was difficult enough

putting the time in to manage that system let

alone tackle another.

Nonetheless they were prepared to look at the

framework from a passive perspective observe

and discuss the potential application of the

model to their business without becoming more

formally involved and seeking the recognition

through the awards process.

The Case Study Enterprises

A description of the three case study small

horticultural enterprises follows:

1. A strawberry grower and packer whose

market is primarily linked into a major

supermarket chain. The husband works

full-time in the business and handles the

field- work (soil preparation and crop

maintenance) and employs up to 4 casuals

for picking and planting purposes. The

spouse manages the packing operation and

employs up to 3 casuals during harvest

operations only.

2. A stone fruit grower and packer whose

produce is primarily marketed through

agents. The husband works full-time in the

business and manages all the field-work

except harvest. Up to 10 casual pickers

may be employed during the short harvest

period. The spouse manages the packing

shed operations and employs up to 3 casuals

during harvest operations only.

3. A cherry grower whose produce is marketed

through an agent / packing shed operation.

The husband works in the field on a full-

time basis. The spouse and up to five

casuals pick and pack the mature fruit

during the short harvest season.

Interestingly, the casuals employed with all the

three case study enterprises were regular

seasonal workers who had had a long-term

involvement with the business.

Applying The Self-Assessment Tool

The seven categories of the excellence

framework were then applied to the each of the

case study enterprises by reviewing the set

criteria and comparing them with the way the

business currently operates. The following

observations were made on some of the major

aspects of the framework:

Category 1: Leadership and I nnovation

The case study enterprises had no business

strategy or strategic direction whatsoever.

Planning was based purely on past practice and

on agreements made with their principal

customers. Indicators of success were based on

market prices and the end-of-season tally. There

was some knowledge of the cost of production,

particularly in relation to casual labour and

resources such as fuel, farm chemicals,

packaging etc. However, little attention was

paid to the cost of their own efforts in fact it

was stated that if they really knew how much

they earned for their own work, they wouldnt

do it.

Innovation and operational improvements

tended to be industry rather than enterprise

driven. In one case however, the process of

external certification had stimulated a total re-

think of the business operations and a number of

quality improvements had been implemented.

The enterprise values and ethics in use were

closely related to that of the family itself and

were effectively dispersed throughout the

business. High employee (and employer)

loyalty was evident. This was probably related

to the fact that the casual workers had had a

long-term relationship with the business and

would not necessarily be the case if the casual

employees were itinerant. Leadership

throughout the business was strong and workers

were empowered.

Category 2: Strategy and Planning Processes

The enterprises had a good understanding of the

produce they grew and the specific market

environment however much lesser knowledge of

the greater industry itself (produce line or fruit

and vegetable industries in total). As a result

they could respond very quickly to problems in

the field and their own changing market

conditions.

When it came to prices for harvested produce,

they were predominantly price-takers rather than

price-makers. Even in poor markets the only

choice that the case study enterprises had was to

accept market prices or risk losing established

relationships.

With one exception, there was little thought

about seeking alternative markets or value-

adding produce.

Category 3: Data, I nformation and Knowledge

In this area the case study enterprises had strong

knowledge of what was happening within their

organisations. Enterprises had demonstrated

that they had the ability to respond very quickly

to changing farm conditions and those employed

within the business (whether on a full-time or

part-time basis), were likely to be multi-skilled

having been trained on-the-job. Although

specific measuring and statistical techniques

were not used, each business was closely

observed from within and out-of-the-norm on-

farm situations could be generally managed so

as to minimise risk to the operation. With the

exception of farm chemical application, daily

harvested produce quantities (seasonal only) and

distribution details (seasonal only for

identification and traceability purposes), little or

no other data is collected and analysed.

There was little knowledge of market activities

and there was a generally belief that they could

not influence the market, in fact, they believed

that the market had a strong influence on them.

There were many instances to indicate that they

were vulnerable to slumps in the market. One

case study business was considering leaving the

fresh produce market and participating in the

processed market only. This was not surprising

as this enterprise had strong links into and could

directly influence the processed fruit market.

Category 4: People

This category demonstrated the strengths that

underpin small businesses in general. The three

case study enterprises had strong people

relationships within. Employee loyalty and

mutual respect was high.

Although training was generally limited to on-

the-job and did not necessarily relate to the

wider aspects of people development,

employees were generally well equipped to

handle their work. It was interesting to note the

progressive transformation from on-the-job and

demonstrative practices through coaching and

counselling to empowerment of the employee.

In many ways employees were able to realise

their own potential whilst supporting

organisational goals and objectives.

The opportunity for timely feedback was also

ever present as the potential for internal

communication was excellent. All employees

were encouraged and enabled to make a

personally satisfying contribution, fully well

knowing how their job and task performance

impacted on the business as a whole.

Perhaps the only weakness in this area relates to

occupational health and safety and well-being

where formal processes and structures are

generally not in place and no formal policies and

procedures exist. There is however a positive

move towards providing a safer physical work

environment and a genuine concern for the well-

being of employees

Category 5: Customer and Market Focus

The case study enterprises tended to have long-

standing customer-supplier relationships within

their market. Although there was often close

liaison between the customer and themselves the

relationship was generally driven by the

customer (in most cases a major retail chain)

who determined what quantities of harvested

produce were to be delivered, when they were to

be delivered and at what price. All case study

enterprises had experienced the cancellation of

orders (often after the packaging of produce in

customer specific packaging) as well as

substantial increases in ordered quantities and

had to respond quickly to customer

requirements. The customer-supplier

relationship is very much one-sided in the

favour of the retailers.

Although the enterprises worked to produce

specifications there was often disagreement on

the physical application of it. On several

occasions produce was rejected because it was

deemed to have failed to meet the specification

only to be accepted a day or two later. These

inconsistencies have been and are continually

the subject of discussions between the supplier

(the SHE) and the customer (the retailer)

Category 6: Processes, Products and Services

The three case study enterprises all had third

party certified quality / food safety systems in

place and these were developed and

implemented at the request of the customer

(major retail chain and market agents). The

systems themselves supported innovation and

change and the process of continuous

improvement however this was not the focus

within the case study enterprises. The primary

reasons for implementation were to meet the

demands of the customer organisation and to

manage the quality and food safety of the

produce. Often the continuous improvement

activity was put aside so that the enterprise

could focus on the day-to-day operational

activities. Little, if any time, was devoted to

reflection, analysis or improvement activities.

Category 7: Business Results

The three case study enterprises did not

demonstrate any strengths in this area. The

intent of this category is to demonstrate the

performance of the organisation to date and, by

using appropriate measures, to envision its

success into the future. In this case no definitive

key performance indicators are used and there is

no formal benchmarking within the industry.

Although each business was able to demonstrate

that they had deployed improvements

discovered during the development and

implementation phases of their quality / food

safety system, there did not appear to be other

opportunities taken to think about improvements

within their own business let alone within the

industry itself. With the exception of planning

the number of trees or seedlings to be planted,

all three case study enterprises indicated that

measuring performance and planning for the

future, more than one season ahead, just did not

happen. As long as production levels (and

prices) were as good as or better than previous

years they tended to be satisfied that their

operations were effective.

Small Business Characteristics Does

The ABEF Take These Into Account?

Hewitt in the article titled Business excellence:

does it work for small companies (1997, pp. 80-

81) suggests that small businesses demonstrate a

number of characteristics that differentiate them

from large organisations. Some typical small

business strengths are that they:

1. have the ability to respond very quickly to

changing market conditions;

2. waste little time on non-core business

activities;

3. tend to have high employee loyalty;

4. reflect the commitment of the small

business owner;

5. are likely to deploy improvements quickly

and therefore gain rapid benefit;

6. are usually very closely in touch with

customers;

7. have the potential for excellent internal

communication;

8. have people who are likely to be multi-

skilled;

9. training is likely to be very focussed on

skills needed to achieve targets;

10. people will usually be aware of how their

job impacts on the business as a whole.

Hewitt (1997, p. 81) also suggests that there are

a number of small business risk areas including:

1. they are highly vulnerable to slumps in

markets;

2. funding investment is more critical;

3. cashflow is critical;

4. they may not have time to look at the

outside world;

5. they may have difficulties in getting good

suppliers;

6. they may be operating an inappropriate

quality management system because of

customer pressure to be certified (to ISO

9000);

7. there is little time available to think about

improvement;

8. training budgets are likely to be limited and

wider aspects of people development will

probably not be addressed.

When one reviews the two lists it is clear that

these strengths are entwined within the

excellence framework (see Table I).

It therefore appears that the Australian Business

Excellence Framework holds itself as a

potentially useful tool for small horticultural

enterprises (and small businesses alike) to self-

assess and provide the means for business

improvement.

ABEF

Category

Small

Business

Strengths

Small

Business

Risk Areas

1. Leadership &

Innovation

4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 4, 7, 8

2. Strategy &

Planning

Process

1, 7, 8, 10 4, 5

3. Data,

Information &

Knowledge

1, 2, 7, 9 1, 2, 3, 6, 8

4. People 3, 4, 7, 8, 9, 10 8

5. Customer &

Market Focus

1, 6, 7 4, 5, 6

6. Processes,

Products &

Services

1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 7,

10

4, 5

7. Business

Results

7 1, 2, 3, 7

Table I: Linking the ABEF with Small Business

Characteristics

Conclusion

Small businesses, including small horticultural

enterprises, can use the Australian Business

Excellence Framework as a useful tool for

business improvement. This, however, is

unlikely due to:

The perceived excessive costs associated

with the program. Small businesses alike

will find it difficult to fund such an activity

to the levels required.

The process associated with the

development of the application, submission

and post-submission activities. Many small

horticultural enterprises will have

difficulties in understanding the process and

in writing the required submission.

The perception that the time, effort and

costs associated will not lead to a

commensurate improvement. There is

much resource investment required when

undertaking this process. Small

horticultural enterprises question, in a

similar vein to food safety and quality

system certification, what will they get out

of it.

The distinct impression that framework is

for larger enterprises. It is perceived that

larger enterprises can afford to put the time,

effort and required resources into such a

process.

Nonetheless, the excellence framework can be

used informally as a self-assessment tool.

Although there is still some apprehension with

regards to the case study enterprises, they

havent written off the next step a more formal

attempt at self-assessment.

Acknowledgement

The author acknowledges the support of

Computing Devices Canada, a General Electrics

Company, in the conduct of this research.

References

1. Australian Business Excellence Awards

Application Guidelines 2000, (2000)

Australian Quality Council

2. The Australian Business Excellence

Framework, (1999) Australian Quality Council

3. Hewitt, S. (1997) Business excellence: does

it work for small companies? in The TQM

Magazine, Vol. 9, No. 1, pp. 76-82

Autobiographical Notes

Peter Bryar is an organisational development

practitioner who works principally with small

horticultural enterprises. After completing a

Masters of Business and Masters of Applied

Science on a part-time basis, Peter decided to

pursue further studies full-time and attempt to

link his passion for learning and his curiosity

relating to how small businesses operate.

Peter is undertaking doctoral studies at RMIT

Universitys Centre for Management Quality

Research. His thesis is titled Supply Chain

Quality Improvement: The Case of Small

Horticultural Enterprises and looks at how

small fruit and vegetable growing enterprises

develop, implement and maintain their food

safety and quality management systems.

Você também pode gostar

- MetasetupDocumento1 páginaMetasetupsimphiwe8043Ainda não há avaliações

- Mental ModelsDocumento2 páginasMental ModelsVineet KamatAinda não há avaliações

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (890)

- Root Cause Analysis PresentationDocumento37 páginasRoot Cause Analysis PresentationucheonixAinda não há avaliações

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- ACB System Installation ManualDocumento12 páginasACB System Installation ManualAngAinda não há avaliações

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (399)

- Post Training ActivitiesDocumento67 páginasPost Training Activitiessimphiwe8043Ainda não há avaliações

- E-Commerce Business ModelDocumento40 páginasE-Commerce Business ModelNisa Noor MohdAinda não há avaliações

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5794)

- 0005 PURE GYM A4 New Property Flyer V21Documento2 páginas0005 PURE GYM A4 New Property Flyer V21simphiwe8043Ainda não há avaliações

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- Cmt1 Sample ADocumento41 páginasCmt1 Sample AsankarjvAinda não há avaliações

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- Iodsa Gai Handout 2012Documento11 páginasIodsa Gai Handout 2012simphiwe8043Ainda não há avaliações

- Ten 2815Documento112 páginasTen 2815simphiwe8043100% (1)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- CIMA Qualification and SyllabusDocumento50 páginasCIMA Qualification and SyllabusMoyce M MotlhabaneAinda não há avaliações

- Full Text 01Documento25 páginasFull Text 01simphiwe8043Ainda não há avaliações

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- NewyorkDocumento31 páginasNewyorksimphiwe8043Ainda não há avaliações

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- Accenture Global Agenda CEO Briefing 2014 Competing Digital WorldDocumento44 páginasAccenture Global Agenda CEO Briefing 2014 Competing Digital Worldsimphiwe8043Ainda não há avaliações

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2219)

- The Principles of Scientific ManagementDocumento155 páginasThe Principles of Scientific Managementsimphiwe8043Ainda não há avaliações

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- TQM Excellence ModelDocumento3 páginasTQM Excellence Modelodang rizki100% (2)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (344)

- Employee Satisfaction Survey PresentationDocumento36 páginasEmployee Satisfaction Survey Presentationsimphiwe8043Ainda não há avaliações

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (265)

- TQM Excellence ModelDocumento3 páginasTQM Excellence Modelodang rizki100% (2)

- Mental ModelsDocumento2 páginasMental ModelsVineet KamatAinda não há avaliações

- SA Tender BulletinDocumento168 páginasSA Tender Bulletinsimphiwe8043Ainda não há avaliações

- Workforce of The Future EbookDocumento27 páginasWorkforce of The Future Ebooksimphiwe8043Ainda não há avaliações

- TQM Excellence ModelDocumento3 páginasTQM Excellence Modelodang rizki100% (2)

- Liquor AuditDocumento4 páginasLiquor Auditsimphiwe8043Ainda não há avaliações

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- GE's toolkit fosters retail innovationDocumento27 páginasGE's toolkit fosters retail innovationsimphiwe8043Ainda não há avaliações

- BSC Kaplan-Norton PDFDocumento14 páginasBSC Kaplan-Norton PDFShahrir AhmadAinda não há avaliações

- Zimele - Community FundDocumento1 páginaZimele - Community Fundsimphiwe8043Ainda não há avaliações

- Lean Dashboard v3.4 TEMPLATE PollienizerDocumento37 páginasLean Dashboard v3.4 TEMPLATE Pollienizersimphiwe8043Ainda não há avaliações

- A 20whole 20new 20mindDocumento1 páginaA 20whole 20new 20mindMuhammad HamayunAinda não há avaliações

- 2013 Silver Programme FullDocumento6 páginas2013 Silver Programme Fullsimphiwe8043Ainda não há avaliações

- Zero Trust Readiness Assessment: BenefitsDocumento3 páginasZero Trust Readiness Assessment: BenefitsLuis Barreto100% (1)

- Internship Report On Recruitment and Retention Process of Hup Lun BD LTDDocumento42 páginasInternship Report On Recruitment and Retention Process of Hup Lun BD LTDTonmoy Kabiraj100% (1)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (119)

- SABSA MATRIX ASSETS BUSINESS DECISIONS CONTEXTDocumento1 páginaSABSA MATRIX ASSETS BUSINESS DECISIONS CONTEXTEli_HuxAinda não há avaliações

- Assignment#03: Comsats University IslamabadDocumento3 páginasAssignment#03: Comsats University IslamabadAli Adnan AsgharAinda não há avaliações

- Master Tile Internship UOGDocumento54 páginasMaster Tile Internship UOGAhsanAinda não há avaliações

- AcumaticaERP InvMgmtDocumento247 páginasAcumaticaERP InvMgmtcrudbugAinda não há avaliações

- Chap3 Outline Guide (Amra & Benelifa)Documento14 páginasChap3 Outline Guide (Amra & Benelifa)CSJAinda não há avaliações

- 5 KRAs of ISADocumento169 páginas5 KRAs of ISAJohn Wesley Calagui100% (2)

- Introduction I. The Possible Alternative Strategies and The Most Appropriate Future Strategy 1.1Documento2 páginasIntroduction I. The Possible Alternative Strategies and The Most Appropriate Future Strategy 1.1Monina AmanoAinda não há avaliações

- PMP® Exam Simulation #1Documento70 páginasPMP® Exam Simulation #1keight_NAinda não há avaliações

- JIT FinalDocumento10 páginasJIT FinalMarie Antoinette HolandaAinda não há avaliações

- Integrating Lean & Six SigmaDocumento6 páginasIntegrating Lean & Six SigmapandaprasadAinda não há avaliações

- 08 Hands On Activity 222 ARG DelacruzDocumento6 páginas08 Hands On Activity 222 ARG DelacruzFrancis CaminaAinda não há avaliações

- Embracing: Low-Code DevelopmentDocumento8 páginasEmbracing: Low-Code DevelopmentMridul HakeemAinda não há avaliações

- Project Management: Strategic IssuesDocumento14 páginasProject Management: Strategic Issuesrenos73Ainda não há avaliações

- Standard Costing and Flexible Budget 10Documento5 páginasStandard Costing and Flexible Budget 10Lhorene Hope DueñasAinda não há avaliações

- MS Unit Ii & Unit IiiDocumento52 páginasMS Unit Ii & Unit Iiimba departmentAinda não há avaliações

- A1 DIKAR Model in ICT Strategic PlanningDocumento3 páginasA1 DIKAR Model in ICT Strategic PlanningBadder Danbad67% (3)

- MAS Printable LectureDocumento17 páginasMAS Printable LectureNiña Mae NarcisoAinda não há avaliações

- Ratnakar Vithoba Gaikwad 2019Documento5 páginasRatnakar Vithoba Gaikwad 2019Ratnakar GaikwadAinda não há avaliações

- Chapter 3 Income Measurement and ReportingDocumento13 páginasChapter 3 Income Measurement and ReportingPrakashAinda não há avaliações

- 08 - Chapter 1 PDFDocumento52 páginas08 - Chapter 1 PDFDivyam NarnawareAinda não há avaliações

- C TSCM52 65 Sample QuestionsDocumento4 páginasC TSCM52 65 Sample Questionsolecosas4273Ainda não há avaliações

- Undifferentiated Marketing Differentiated Marketing Concentrated Targeting Customized MarketingDocumento5 páginasUndifferentiated Marketing Differentiated Marketing Concentrated Targeting Customized MarketingTekletsadik TeketelAinda não há avaliações

- MIS Implementation Challenges and Sucess Case - MSC ThesisDocumento67 páginasMIS Implementation Challenges and Sucess Case - MSC Thesisbassa741100% (1)

- Robbins mgmt15 PPT 09Documento31 páginasRobbins mgmt15 PPT 0920211211018 DHANI AKSAN ARASYADAinda não há avaliações

- Customer-Driven Marketing StrategyDocumento43 páginasCustomer-Driven Marketing Strategymira chehabAinda não há avaliações

- 2013 State of Devops ReportDocumento12 páginas2013 State of Devops ReportJMassapinaAinda não há avaliações

- Strategic Decision Making ProcessDocumento34 páginasStrategic Decision Making ProcessArpita PatelAinda não há avaliações

- CV Laurentiu ManglutescuDocumento5 páginasCV Laurentiu ManglutescuManglutescu LaurentiuAinda não há avaliações