Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Teoria Si Practica Textului

Enviado por

Claudia-Andreea DascaluDescrição original:

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Teoria Si Practica Textului

Enviado por

Claudia-Andreea DascaluDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

1.

Bernard Malamud The Magic Barrel + The Theme of the Three Caskets

2. Alice Walker Nineteen Fift!Fi"e

#. $amond Car"er What We Talk A%out When We Talk A%out &o"e

'. $ichard Ford $ock ()rings

*. Mukher+ee Bharati The Management of ,rief

-. &ee (mith . Bernard Malamud /ntensi"e Care .

0 Tim 12Brien The Things The Carried

3 (herman Ale4ie This /s What /t Means to (a 5hoeni4 Ari6ona

7 (andra Cisneros . 8unot 9ia6 The :ouse on Mango (treet . Fiesta 173;

1

1

Bernard Malamud

Bernard Malamud

The Magic Barrel

Not long ago there lived in uptown New York, in a

small, almost meager room, though crowded with

books, Leo Finkle, a rabbinical student in the

Yeshivah University. Finkle, after six years of study,

was to be ordained in une and had been advised by

an ac!uaintance that he might find it easier to win

himself a congregation if he were married. "ince he

had no present prospects of marriage, after two

tormented days of turning it over in his mind, he

called in #inye "al$man, a marriage broker whose

two%line advertisement he had read in the Forward.

&he matchmaker appeared one night out of the

dark fourth%floor hallway of the graystone rooming

house where Finkle lived, grasping a black, strapped

portfolio that had been worn thin with use. "al$man,

who had been long in the business, was of slight but

dignified build, wearing an old hat, and an overcoat

too short and tight for him. 'e smelled frankly of

fish, which he loved to eat, and although he was

missing a few teeth, his presence was not

displeasing, because of an amiable manner curiously

contrasted with mournful eyes. 'is voice, his lips,

his wisp of beard, his bony fingers were animated,

but give him a moment of repose and his mild blue

eyes revealed a depth of sadness, a characteristic

that put Leo a little at ease although the situation,

for him, was inherently tense.

'e at once informed "al$man why he had asked

him to come, explaining that his home was in

(leveland, and that but for his parents, who had

married comparatively late in life, he was alone in

the world. 'e had for six years devoted himself

almost entirely to his studies, as a result of which,

understandably, he had found himself without time

for a social life and the company of young women.

&herefore he thought it the better part of trial and

error ) of embarrassing fumbling ) to call in an

experienced person to advise him on these matters.

'e remarked in passing that the function of the

marriage broker was ancient and honorable, highly

approved in the ewish community, because it made

practical the necessary without hindering *oy.

+oreover, his own parents had been brought

together by a matchmaker. &hey had made, if not a

financially profitable marriage ) since neither had

possessed any worldly goods to speak of ) at least a

successful one in the sense of their everlasting

devotion to each other. "al$man listened in

embarrassed surprise, sensing a sort of apology.

Later, however, he experienced a glow of pride in his

work, an emotion that had left him years ago, and he

heartily approved of Finkle.

&he two went to their business. Leo had led

"al$man to the only clear place in the room, a table

near a window that overlooked the lamp%lit city. 'e

seated himself at the matchmaker,s side but facing

him, attempting by an act of will to suppress the

unpleasant tickle in his throat. "al$man eagerly

unstrapped his portfolio and removed a loose rubber

band from a thin packet of much%handled cards. -s

he flipped through them, a gesture and sound that

physically hurt Leo, the student pretended not to see

and ga$ed steadfastly out the window. -lthough it

was still February, winter was on its last legs, signs

of which he had for the first time in years begun to

notice. 'e now observed the round white moon,

moving high in the sky through a cloud menagerie,

and watched with half%open mouth as it penetrated a

huge hen, and dropped out of her like an egg laying

itself. "al$man, though pretending through eye%

glasses he had *ust slipped on, to be engaged in

scanning the writing on the cards, stole occasional

glances at the young man,s distinguished face,

noting with pleasure the long, severe scholar,s nose,

brown eyes heavy with learning, sensitive yet ascetic

lips, and a certain, almost hollow !uality of the dark

cheeks. 'e ga$ed around at shelves upon shelves of

books and let out a soft, contented sigh.

.hen Leo,s eyes fell upon the cards, he counted

six spread out in "al$man,s hand.

/"o few01 he asked in disappointment.

/You wouldn,t believe me how much cards 2 got in

my office,1 "al$man replied. /&he drawers are

already filled to the top, so 2 keep them now in a

barrel, but is every girl good for a new rabbi01

Leo blushed at this, regretting all he had revealed

of himself in a curriculum vitae he had sent to

"al$man. 'e had thought it best to ac!uaint him

with his strict standards and specifications, but in

having done so, felt he had told the marriage broker

more than was absolutely necessary.

'e hesitantly in!uired, /3o you keep photographs

of your clients on file01

/First comes family, amount of dowry, also what

kind of promises,1 "al$man replied, unbuttoning his

tight coat and settling himself in the chair. /-fter

comes pictures, rabbi.1

/(all me +r. Finkle. 2,m not yet a rabbi.1

2

"al$man said he would, but instead called him

doctor, which he changed to rabbi when Leo was not

listening too attentively.

"al$man ad*usted his horn%rimmed spectacles,

gently cleared his throat and read in an eager voice

the contents of the top card4

/"ophie #. &wenty%four years. .idow one year. No

children. 5ducated high school and two years

college. Father promises eight thousand dollars. 'as

wonderful wholesale business. -lso real estate. 6n

the mother,s side comes teachers, also one actor.

.ell known on "econd -venue.1

Leo ga$ed up in surprise. /3id you say a widow01

/- widow don,t mean spoiled, rabbi. "he lived with

her husband maybe four months. 'e was a sick boy

she made a mistake to marry him.1

/+arrying a widow has never entered my mind.1

/&his is because you have no experience. - widow,

especially if she is young and healthy like this girl, is

a wonderful person to marry. "he will be thankful to

you the rest of her life. 7elieve me, if 2 was looking

now for a bride, 2 would marry a widow.1

Leo reflected, then shook his head.

"al$man hunched his shoulders in an almost

imperceptible gesture of disappointment. 'e placed

the card down on the wooden table and began to

read another4

/Lily '. 'igh school teacher. 8egular. Not a

substitute. 'as savings and new 3odge car. Lived in

#aris one year. Father is successful dentist thirty%five

years. 2nterested in professional man. .ell

-mericani$ed family. .onderful opportunity.1

/2 knew her personally,1 said "al$man. /2 wish you

could see this girl. "he is a doll. -lso very intelligent.

-ll day you could talk to her about books and

theyater and what not. "he also knows current

events.1

/2 don,t believe you mentioned her age01

/'er age01 "al$man said, raising his brows. /'er

age is thirty%two years.1

/Leo said after a while, /2,m afraid that seems a

little too old.

"al$man let out a laugh. /"o how old are you,

rabbi01

/&wenty%seven.1

/"o what is the difference, tell me, between

twenty%seven and thirty%two0 +y own wife is seven

years older than me. "o what did 2 suffer0 ) Nothing.

2f 8othschild,s daughter wants to marry you, would

you say on account her age, no01

/Yes,1 Leo said dryly.

"al$man shook off the no in the eyes. /Five years

don,t mean a thing. 2 give you my word that when

you will live with her for one week you will forget her

age. .hat does it mean five years ) that she lived

more and knows more than somebody who is

younger0 6n this girl, 9od bless her, years are not

wasted. 5ach one that it comes makes better the

bargain.1

/.hat sub*ect does she teach in high school01

/Languages. 2f you heard the way she speaks

French, you will think it is music. 2 am in the

business twenty%five years, and 2 recommend her

with my whole heart. 7elieve me, 2 know what 2,m

talking, rabbi.1

/.hat,s on the next card01 Leo said abruptly.

"al$man reluctantly turned up the third card4

/8uth :. Nineteen years. 'onor student. Father

offers thirteen thousand cash to the right

bridegroom. 'e is a medical doctor. "tomach

specialist with marvelous practice. 7rother in law

owns garment business. #articular people.1

"al$man looked as if he had read his trump card.

/3id you say nineteen01 Leo asked with interest.

/6n the dot.1

/2s she attractive01 'e blushed. /#retty01

"al$man kissed his finger tips. /- little doll. 6n

this 2 give you my word. Let me call the father

tonight and you will see what means pretty.1

7ut Leo was troubled. /You,re sure she,s that

young01

/&his 2 am positive. &he father will show you the

birth certificate.1

/-re you positive there isn,t something wrong with

her01 Leo insisted.

/.ho says there is wrong01

/2 don,t understand why an -merican girl her age

should go to a marriage broker.1

- smile spread over "al$man,s face.

/"o for the same reason you went, she comes.1

Leo flushed. /2 am passed for time.1

"al$man, reali$ing he had been tactless, !uickly

explained. /&he father came, not her. 'e wants she

should have the best, so he looks around himself.

.hen we will locate the right boy he will introduce

him and encourage. &his makes a better marriage

than if a young girl without experience takes for

herself. 2 don,t have to tell you this.1

/7ut don,t you think this young girl believes in

love01 Leo spoke uneasily.

"al$man was about was about to guffaw but caught

himself and said soberly, /Love comes with the right

person, not before.1

Leo parted dry lips but did not speak. Noticing that

"al$man had snatched a glance at the next card, he

cleverly asked, /'ow is her health01

/#erfect,1 "al$man said, breathing with difficulty.

/6f course, she is a little lame on her right foot from

an auto accident that it happened to her when she

was twelve years, but nobody notices on account she

is so brilliant and also beautiful.1

Leo got up heavily and went to the window. 'e felt

curiously bitter and upbraided himself for having

called in the marriage broker. Finally, he shook his

head.

/.hy not01 "al$man persisted, the pitch of his

voice rising.

/7ecause 2 detest stomach specialists.1

/"o what do you care what is his business0 -fter

you marry her do you need him0 .ho says he must

come every Friday night in your house01

-shamed of the way the talk was going, Leo

dismissed "al$man, who went home with heavy,

melancholy eyes.

&hough he had felt only relief at the marriage

broker,s departure, Leo was in low spirits the next

day. 'e explained it as rising from "al$man,s failure

to produce a suitable bride for him. 'e did not care

for his type of clientele. 7ut when Leo found himself

hesitating whether to seek out another matchmaker,

one more polished than #inye, he wondered if it

could be ) protestations to the contrary, and

3

although he honored his father and mother ) that he

did not, in essence, care for the matchmaking

institution0 &his thought he !uickly put out of mind

yet found himself still upset. -ll day he ran around

the woods ) missed an important appointment,

forgot to give out his laundry, walked out of a

7roadway cafeteria without paying and had to run

back with the ticket in his hand; had even not

recogni$ed his landlady in the street when she

passed with a friend and courteously called out, /-

good evening to you, 3octor Finkle.1 7y nightfall,

however, he had regained sufficient calm to sink his

nose into a book and there found peace from his

thoughts.

-lmost at once there came a knock on the door.

7efore Leo could say enter, "al$man, commercial

cupid, was standing in the room. 'is face was gray

and meager, his expression hungry, and he looked as

if he would expire on his feet. Yet the marriage

broker managed, by some trick of the muscles to

display a broad smile.

/"o good evening. 2 am invited01

Leo nodded, disturbed to see him again, yet

unwilling to ask the man to leave.

7eaming still, "al$man laid his portfolio on the

table. /8abbi, 2 got for you tonight good news.1

/2,ve asked you not to call me rabbi. 2,m still a

student.1

/Your worries are finished. 2 have for you a first%

class bride.1

/Leave me in peace concerning this sub*ect.1 Leo

pretended lack of interest.

/&he world will dance at your wedding.1

/#lease, +r. "al$man, no more.1

/7ut first must come back my strength,1 "al$man

said weakly. 'e fumbled with the portfolio straps

and took out of the leather case an oily paper bag,

from which he extracted a hard, seeded roll and a

small, smoked white fish. .ith a !uick emotion of

his hand he stripped the fish out of its skin and

began ravenously to chew. /-ll day in a rush,1 he

muttered.

Leo watched him eat.

/- sliced tomato you have maybe01 "al$man

hesitantly in!uired.

/No.1

&he marriage broker shut his eyes and ate. .hen

he had finished he carefully cleaned up the crumbs

and rolled up the remains of the fish, in the paper

bag. 'is spectacled eyes roamed the room until he

discovered, amid some piles of books, a one%burner

gas stove. Lifting his hat he humbly asked, /- glass

of tea you got, rabbi01

(onscience%stricken, Leo rose and brewed the tea.

'e served it with a chunk of lemon and two cubes of

lump sugar, delighting "al$man.

-fter he had drunk his tea, "al$man,s strength and

good spirits were restored.

/"o tell me rabbi,1 he said amiably, /you

considered some more the three clients 2 mentioned

yesterday01

/&here was no need to consider.1

/.hy not01

/None of them suits me.1

/.hat then suits you01

Leo let it pass because he could give only a

confused answer.

.ithout waiting for a reply, "al$man asked, /You

remember this girl 2 talked to you ) the high school

teacher01

/-ge thirty%two01

7ut surprisingly, "al$man,s face lit in a smile. /-ge

twenty%nine.1

Leo shot him a look. /8educed from thirty%two01

/- mistake,1 "al$man avowed. /2 talked today with

the dentist. 'e took me to his safety deposit box and

showed me the birth certificate. "he was twenty%nine

years last -ugust. &hey made her a party in the

mountains where she went for her vacation. .hen

her father spoke to me the first time 2 forgot to write

the age and 2 told you thirty%two, but now 2

remember this was a different client, a widow.1

/&he same one you told me about0 2 thought she

was twenty%four01

/- different. -m 2 responsible that the world is

filled with widows01

/No, but 2,m not interested in them, nor for that

matter, in school teachers.1

"al$man pulled his clasped hand to his breast.

Looking at the ceiling he devoutly exclaimed,

/Yiddishe kinder, what can 2 say to somebody that he

is not interested in high school teachers0 "o what

then you are interested01

Leo flushed but controlled himself.

/2n what else will you be interested,1 "al$man

went on, /if you not interested in this fine girl that

she speaks four languages and has personally in the

bank ten thousand dollars0 -lso her father

guarantees further twelve thousand. -lso she has a

new car, wonderful clothes, talks on all sub*ects, and

she will give you a first%class home and children.

'ow near do we come in our life to paradise01

2f she,s so wonderful, why wasn,t she married ten

years ago01

/.hy01 said "al$man with a heavy laugh. / ) .hy0

7ecause she is partikiler. &his is why. "he wants the

best.1

Leo was silent, amused at how he had entangled

himself. 7ut "al$man had arouse his interest in Lily

'., and he began seriously to consider calling on her.

.hen the marriage broker observed how intently

Leo,s mind was at work on the facts he had supplied,

he felt certain they would soon come to an

agreement.

Late "aturday afternoon, conscious of "al$man,

Leo Finkle walked with Lily 'irschorn along

8iverside 3rive. 'e walked briskly and erectly,

wearing with distinction the black fedora he had that

morning taken with trepidation out of the dusty hat

box on his closet shelf, and the heavy black "aturday

coat he had throughly whisked clean. Leo also owned

a walking stick, a present from a distant relative, but

!uickly put temptation aside and did not use it. Lily,

petite and not unpretty, had on something signifying

the approach of spring. "he was au courant,

animatedly, with all sorts of sub*ects, and he

weighed her words and found her surprisingly sound

) score another for "al$man, whom he uneasily

sensed to be somewhere around, hiding perhaps

high in a tree along the street, flashing the lady

signals with a pocket mirror; or perhaps a cloven%

hoofed #an, piping nuptial ditties as he danced his

invisible way before them, strewing wild buds on the

walk and purple grapes in their path, symboli$ing

4

fruit of a union, though there was of course still

none.

Lily startled Leo by remarking, /2 was thinking of

+r. "al$man, a curious figure, wouldn,t you say01

Not certain what to answer, he nodded.

"he bravely went on, blushing, /2 for one am

grateful for his introducing us. -ren,t you01

'e courteously replied, /2 am.1

/2 mean,1 she said with a little laugh ) and it was

all in good taste, to at least gave the effect of being

not in bad ) 1do you mind that we came together

so01

'e was not displeased with her honesty,

recogni$ing that she meant to set the relationship

aright, and understanding that it took a certain

amount of experience in life, and courage, to want to

do it !uite that way. 6ne had to have some sort of

past to make that kind of beginning.

'e said that he did not mind. "al$man,s function

was traditional and honorable ) valuable for what it

might achieve, which, he pointed out, was fre!uently

nothing.

Lily agreed with a sigh. &hey walked on for a while

and she said after a long silence, again with a

nervous laugh, /.ould you mind if 2 asked you

something a little bit personal0 Frankly, 2 find the

sub*ect fascinating.1 -lthough Leo shrugged, she

went on half embarrassedly, /'ow was it that you

came to your calling0 2 mean was it a sudden

passionate inspiration01

Leo, after a time, slowly replied, /2 was always

interested in the Law.1

/You saw revealed in it the presence of the

'ighest01

'e nodded and changed the sub*ect. /2 understand

that you spent a little time in #aris, +iss

'irschorn01

/6h, did +r. "al$man tell you, 8abbi Finkle01 Leo

winced but she went on, /2t was ages ago and almost

forgotten. 2 remember 2 had to return for my sister,s

wedding.1

-nd Lily would not be put off. /.hen,1 she asked

in a trembly voice, /did you become enamored of

9od01

'e stared at her. &hen it came to him that she was

talking not about Leo Finkle, but of a total stranger,

some mystical figure, perhaps even passionate

prophet that "al$man had dreamed up for her ) no

relation to the living or dead. Leo trembled with rage

and weakness. &he trickster had obviously sold her a

bill of goods, *ust as he had him, who,d expected to

become ac!uainted with a young lady of twenty%

nine, only to behold, the moment he laid eyes upon

her strained and anxious face, a woman past thirty%

five and aging rapidly. 6nly his self control had kept

him this long in her presence.

/2 am not,1 he said gravely, /a talented religious

person.1 and in seeking words to go on, found

himself possessed by shame and fear. /2 think,1 he

said in a strained manner, /that 2 came to 9od not

because 2 love 'im, but because 2 did not.1

&his confession he spoke harshly because its

unexpectedness shook him.

Lily wilted. Leo saw a profusion of loaves of bread

go flying like ducks high over his head, not unlike

the winged loaves by which he had counted himself

to sleep last night. +ercifully, then, it snowed, which

he would not put past "al$man,s machinations.

'e was infuriated with the marriage broker and

swore he would throw him out of the room the

minute he reappeared. 7ut "al$man did not come

that night, and when Leo,s anger had subsided, an

unaccountable despair grew in its place. -t first he

thought this was caused by his disappointment in

Lily, but before long it became evident that he had

involved himself with "al$man without a true

knowledge of his own intent. 'e gradually reali$ed )

with an emptiness that sei$ed him with six hands )

that he had called in the broker to find him a bride

because he was incapable of doing it himself. &his

terrifying insight he had derived as a result of his

meeting and conversation with Lily 'irschorn. 'er

probing !uestions had somehow irritated him into

revealing ) to himself more than her ) the true

nature of his relationship to 9od, and from that it

had come upon him, with shocking force, that apart

from his parents, he had never loved anyone. 6r

perhaps it went the other way, that he did not love

9od so well as he might, because he had not loved

man. 2t seemed to Leo that his whole life stood

starkly revealed and he saw himself for the first time

as he truly was ) unloved and loveless. &his bitter

but somehow not fully unexpected revelation

brought him to a point to panic, controlled only by

extraordinary effort. 'e covered his face with his

hands and cried.

&he week that followed was the worst of his life.

'e did not eat and lost weight. 'is beard darkened

and grew ragged. 'e stopped attending seminars

and almost never opened a book. 'e seriously

considered leaving the Yeshiva, although he was

deeply troubled at the thought of the loss of all his

years of study ) saw them like pages torn from a

book, strewn over the city ) and at the devastating

effect of this decision upon his parents. 7ut he had

lived without knowledge of himself, and never in the

Five 7ooks and all the (ommentaries ) mea culpa )

had the truth been revealed to him. 'e did not know

where to turn, and in all this desolating loneliness

there was no to whom, although he often thought of

Lily but not once could bring himself to go

downstairs and make the call. 'e became touchy

and irritable, especially with his landlady, who asked

him all manner of personal !uestions; on the other

hand sensing his own disagreeableness, he waylaid

her on the stairs and apologi$ed ab*ectly, until

mortified, she ran from him. 6ut of this, however, he

drew the consolation that he was a ew and that a

ew suffered. 7ut generally, as the long and terrible

week drew to a close, he regained his composure and

some idea of purpose in life to go on as planned.

-lthough he was imperfect, the ideal was not. -s for

his !uest of a bride, the thought of continuing

afflicted him with anxiety and heartburn, yet

perhaps with this new knowledge of himself he

would be more successful than in the past. #erhaps

love would now come to him and a bride to that love.

-nd for this sanctified seeking who needed a

"al$man0

&he marriage broker, a skeleton with haunted

eyes, returned that very night. 'e looked, withal, the

5

picture of frustrated expectancy ) as if he had

steadfastly waited the week at +iss Lily 'irschorn,s

side for a telephone call that never came.

(asually coughing, "al$man came immediately to

the point4 /"o how did you like her01

Leo,s anger rose and he could not refrain from

chiding the matchmaker4 /.hy did you lie to me,

"al$man01

"al$man,s pale face went dead white, the world

had snowed on him.

/3id you not state that she was twenty%nine0, Leo

insisted.

/2 give you my word ) 1

/"he was thirty%five, if a day. -t least thirty%five.1

/6f this don,t be too sure. 'er father told me ) 1

/Never mind. &he worst of it was that you lied to

her.1

/'ow did 2 lie to her, tell me01

/You told her things abut me that weren,t true.

You made out to be more, conse!uently less than 2

am. "he had in mind a totally different person, a sort

of semi%mystical .onder 8abbi.1

/-ll 2 said, you was a religious man.1

/2 can imagine.1

"al$man sighed. /&his is my weakness that 2 have,1

he confessed. /+y wife says to me 2 shouldn,t be a

salesman, but when 2 have two fine people that they

would be wonderful to be married, 2 am so happy

that 2 talk too much.1 'e smiled wanly. /&his is why

"al$man is a poor man.1

Leo,s anger left him. /.ell, "al$man, 2,m afraid

that,s all.1

&he marriage broker fastened hungry eyes on him.

/You don,t want any more a bride01

/2 do,1 said Leo, /but 2 have decided to seek her in

a different way. 2 am no longer interested in an

arranged marriage. &o be frank, 2 now admit the

necessity of premarital love. &hat is, 2 want to be in

love with the one 2 marry.1

/Love01 said "al$man, astounded. -fter a moment

he remarked /For us, our love is our life, not for the

ladies. 2n the ghetto they ) 1

/2 know, 2 know,1 said Leo. /2,ve thought of it

often. Love, 2 have said to myself, should be a by%

product of living and worship rather than its own

end. Yet for myself 2 find it necessary to establish the

level of my need and fulfill it.1

"al$man shrugged but answered, /Listen, rabbi, if

you want love, this 2 can find for you also. 2 have

such beautiful clients that you will love them the

minute your eyes will see them.1

Leo smiled unhappily. /2,m afraid you don,t

understand.1

7ut "al$man hastily unstrapped his portfolio and

withdrew a manila packet from it.

/#ictures,1 he said, !uickly laying the envelope on

the table.

Leo called after him to take the pictures away, but

as if on the wings of the wind, "al$man had

disappeared.

+arch came. Leo had returned to his regular

routine. -lthough he felt not !uite himself yet )

lacked energy ) he was making plans for a more

active social life. 6f course it would cost something,

but he was an expert in cutting corners; and when

there were no corners left he would make circles

rounder. -ll the while "al$man,s pictures had lain on

the table, gathering dust. 6ccasionally as Leo sat

studying, or en*oying a cup of tea, his eyes fell on the

manila envelope, but he never opened it.

&he days went by and no social life to speak of

developed with a member of the opposite sex ) it

was difficult, given the circumstances of his

situation. 6ne morning Leo toiled up the stairs to his

room and stared out the window at the city.

-lthough the day was bright his view of it was dark.

For some time he watched the people in the street

below hurrying along and then turned with a heavy

heart to his little room. 6n the table was the packet.

.ith a sudden relentless gesture he tore it open. For

a half%hour he stood by the table in a state of

excitement, examining the photographs of the ladies

"al$man had included. Finally, with a deep sigh he

put them down. &here were six, of varying degree of

attractiveness, but look at them along enough and

they all became Lily 'irschorn4 all past their prime,

all starved behind bright smiles, not a true

personality in the lot. Life, despite their frantic

yoohooings, had passed them by; they were pictures

in a brief case that stank of fish. -fter a while,

however, as Leo attempted to return the

photographs into the envelope, he found in it

another, a snapshot of the type taken by a machine

for a !uarter. 'e ga$ed at it a moment and let out a

cry.

'er face deeply moved him. .hy, he could at first

not say. 2t gave him the impression of youth ) spring

flowers, yet age ) a sense of having been used to the

bone, wasted; this came from the eyes, which were

hauntingly familiar, yet absolutely strange. 'e had a

vivid impression that he had met her before, but try

as he might he could not place her although he could

almost recall her name, as he had read it in her own

handwriting. No, this couldn,t be; he would have

remembered her. 2t was not, he affirmed, that she

had an extraordinary beauty ) no, though her face

was attractive enough; it was that something about

her moved him. Feature for feature, even some of the

ladies of the photographs could do better; but she

lapsed forth to this heart ) had lived, or wanted to )

more than *ust wanted, perhaps regretted how she

had lived ) had somehow deeply suffered4 it could be

seen in the depths of those reluctant eyes, and from

the way the light enclosed and shone from her, and

within her, opening realms of possibility4 this was

her own. 'er he desired. 'is head ached and eyes

narrowed with the intensity of his ga$ing, then as if

an obscure fog had blown up in the mind, he

experienced fear of her and was aware that he had

received an impression, somehow, of evil. 'e

shuddered, saying softly, it is thus with us all. Leo

brewed some tea in a small pot and sat sipping it

without sugar, to calm himself. 7ut before he had

finished drinking, again with excitement he

examined the face and found it good4 good for Leo

Finkle. 6nly such a one could understand him and

help him seek whatever he was seeking. "he might,

perhaps, love him. 'ow she had happened to be

among the discards in "al$man,s barrel he could

never guess, but he knew he must urgently go find

her.

Leo rushed downstairs, grabbed up the 7ronx

telephone book, and searched for "al$man,s home

6

address. 'e was not listed, nor was his office.

Neither was he in the +anhattan book. 7ut Leo

remembered having written down the address on a

slip of paper after he had read "al$man,s

advertisement in the /personals1 column of the

Forward. 'e ran up to his room and tore through his

papers, without luck. 2t was exasperating. ust when

he needed the matchmaker he was nowhere to be

found. Fortunately Leo remembered to look in his

wallet. &here on a card he found his name written

and a 7ronx address. No phone number was listed,

the reason ) Leo now recalled ) he had originally

communicated with "al$man by letter. 'e got on his

coat, put a hat on over his skull cap and hurried to

the subway station. -ll the way to the far end of the

7ronx he sat on the edge of his seat. 'e was more

than once tempted to take out the picture and see if

the girl,s face was as he remembered it, but he

refrained, allowing the snapshot to remain in his

inside coat pocket, content to have her so close.

.hen the train pulled into the station he was waiting

at the door and bolted out. 'e !uickly located the

street "al$man had advertised.

&he building he sought was less than a block from

the subway, but it was not an office building, nor

even a loft, nor a store in which one could rent office

space. 2t was a very old tenement house. Leo found

"al$man,s name in pencil on a soiled tag under the

bell and climbed three dark flights to his apartment.

.hen he knocked, the door was opened by a think,

asthmatic, gray%haired woman in felt slippers.

/Yes01 she said, expecting nothing. "he listened

without listening. 'e could have sworn he had seen

her, too, before but knew it was an illusion.

/"al$man ) does he live here0 #inye "al$man,1 he

said, /the matchmaker01

"he stared at him a long minute. /6f course.1

'e felt embarrassed. /2s he in01

/No.1 'er mouth, thought left open, offered

nothing more.

/&he matter is urgent. (an you tell me where his

office is01

/2n the air.1 "he pointed upward.

/You mean he has no office01 Leo asked.

/2n his socks.1

'e peered into the apartment. 2t was sunless and

dingy, one large room divided by a half%open curtain,

beyond which he could see a sagging metal bed. &he

near side of the room was crowded with rickety

chairs, old bureaus, a three%legged table, racks of

cooking utensils, and all the apparatus of a kitchen.

7ut there was no sign of "al$man or his magic barrel,

probably also a figment of the imagination. -n odor

of frying fish made weak to the knees.

/.here is he01 he insisted. /2,ve got to see your

husband.1

-t length she answered, /"o who knows where he

is0 5very time he thinks a new thought he runs to a

different place. 9o home, he will find you.1

/&ell him Leo Finkle.1

"he gave no sign she had heard.

'e walked downstairs, depressed.

7ut "al$man, breathless, stood waiting at his door.

Leo was astounded and over*oyed. /'ow did you

get here before me01

/2 rushed.1

/(ome inside.1

&hey entered. Leo fixed tea, and a sardine

sandwich for "al$man. -s they were drinking he

reached behind him for the packet of pictures and

handed them to the marriage broker.

"al$man put down his glass and said expectantly,

/You found somebody you like01

/Not among these.1

&he marriage broker turned away.

/'ere is the one 2 want.1 Leo held forth the

snapshot.

"al$man slipped on his glasses and took the

picture into his trembling hand. 'e turned ghastly

and let out a groan.

/.hat,s the matter01 cried Leo.

/5xcuse me. .as an accident this picture. "he isn,t

for you01

"al$man frantically shoved the manila packet into

his portfolio. 'e thrust the snapshot into his pocket

and fled down the stairs.

Leo, after momentary paralysis, gave chase and

cornered the marriage broker in the vestibule. &he

landlady made hysterical out cries but neither of

them listened.

/9ive me back the picture, "al$man.1

/No.1 &he pain in his eyes was terrible.

/&ell me who she is then.1

/&his 2 can,t tell you. 5xcuse me.1

'e made to depart, but Leo, forgetting himself,

sei$ed the matchmaker by his tight coat and shook

him fren$iedly.

/#lease,1 sighed "al$man. /#lease.1

Leo ashamedly let him go. /&ell me who she is,1 he

begged. /2t,s very important to me to know.1

/"he is not for you. "he is a wild one ) wild,

without shame. &his is not a bride for a rabbi.1

/.hat do you mean wild01

/Like an animal. Like a dog. For her to be poor was

a sin. &his is why to me she is dead now.1

/2n 9od,s name, what do you mean01

/'er 2 can,t introduce to you,1 "al$man cried.

/.hy are you so excited01

/.hy, he asks,1 "al$man said, bursting into tear.

/&his is my baby, my "tella, she should burn in hell.1

Leo hurried up to bed and hid under the covers.

Under the covers he thought his life through.

-lthough he soon fell asleep he could not sleep her

out of his mind. 'e woke, beating his breast. &hough

he prayed to be rid of her, his prayers went

unanswered. &hrough days of torment he endlessly

struggled not to love her; fearing success, he escaped

it. 'e then concluded to convert her to goodness,

himself to 9od. &he idea alternately nauseated and

exalted him.

'e perhaps did not know that he had come to a

final decision until he encountered "al$man in a

7roadway cafeteria. 'e was sitting alone at a rear

table, sucking the bony remains of a fish. &he

marriage broker appeared haggard, and transparent

to the point of vanishing.

"al$man looked up at first without recogni$ing

him. Leo had grown a pointed beard and his eyes

were weighted with wisdom.

/"al$man,1 he said, /love has at last come to my

heart.1

7

/.ho can love from a picture01 mocked the

marriage broker.

/2t is not impossible.1

/2f you can love her, then you can love anybody.

Let me show you some new clients that they *ust sent

me their photographs. 6ne is a little doll.1

/ust her 2 want,1 Leo murmured.

/3on,t be a fool, doctor 3on,t bother with her.1

/#ut me in touch with her, "al$man,1 Leo said

humbly. /#erhaps 2 can be of service.1

"al$man had stopped eating and Leo understood

with emotion that it was now arranged.

Leaving the cafeteria, he was, however, afflicted by

a tormenting suspicion that "al$man had planned it

all to happen this way.

Leo was informed by better that she would meet

him on a certain corner, and she was there one

spring night, waiting under a street lamp. 'e

appeared carrying a small bou!uet of violets and

rosebuds. "tella stood by the lamp post, smoking.

"he wore white with red shoes, which fitted his

expectations, although in a troubled moment he had

imagined the dress red, and only the shoes white.

"he waited uneasily and shyly. From afar he saw that

her eyes ) clearly her father,s ) were filled with

desperate innocence. 'e pictured, in her, his own

redemption. <iolins and lit candles revolved in the

sky. Leo ran forward with flowers out%thrust.

-round the corner, "al$man, leaning against a

wall, chanted prayers for the dead.

=>?@

On The Magic Barrel

Introduction

7ernard +alamudAs short story, B&he +agic 7arrel,B

was first published in the Partisan Review in =>?C,

and reprinted in =>?@ in +alamudAs first volume of

short fiction. &his tale of a rabbinical studentAs

misadventures with a marriage broker was !uite well

received in the =>?Ds, and +alamudAs collection of

short stories,The Magic Barrel, won the National

7ook -ward for fiction in =>?>.

-s +alamud attained a reputation as a respected

novelist in the =>EDs and =>FDs, his short stories

were widely anthologi$ed and attracted considerable

attention from literary students and scholars.

- writer in the ewish%-merican tradition, +alamud

wrote stories that explore issues and themes central

to the ewish community. - love story with a

surprising outcome, B&he +agic 7arrelB traces a

young manAs struggle to come to terms with his

identity and poses the religious !uestion of how

peopleGews and othersG may come to love 9od. 2s

human love, the story asks, a necessary first step to

loving 9od0 +alamudAs B&he +agic 7arrelB is a story

remarkable for its economy, using *ust a few strokes

to create compelling and complex characters.

The Magic Barrel Summary | Detailed

Summary

6n a cold day in February, Leo Finkle, a HF%year%old

rabbinical student at New YorkAs Yeshivah

University, is sitting in his small apartment

regretting the fact that he decided to call in a

matchmaker to help him find a wife. 'owever,

Finkle knows that he needs to find a wife if he wants

to get an appointment as a rabbi after he graduates,

so he patiently waits for #inye "al$man to arrive and,

hopefully, arrange a suitable match for him.

#inye "al$man arrives and cuts a not displeasing

figure with his dignified air and wi$ened looks.

'owever, he is also missing teeth and he smells

distinctly of fish, which he eats constantly, so he is

not entirely pleasant either. 'owever, more

importantly, he carries a binder holding pictures of

eligible ewish women with him, and Finkle hopes

that it holds a woman for him.

&o explain himself, Finkle tells "al$man that he is a

student too wrapped up in his studies to have a

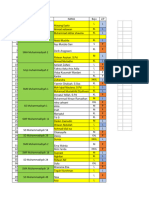

Corey Fischer and Max G. Moore star in Traelin!

"e#ish Theatre$s %roduction o& 2 x Malamud' The

"e#(ird ) The Ma!ic Barrel

*

proper social life and, but for his parents in

(leveland, he is !uite alone. &hus, with few female

prospects in his life, he has called in a marriage

broker, which Finkle considers a very honored

position in the ewish community, to make

Bpractical the necessary without hindering the *oy.B

IHJ "al$man, of course, is !uite pleased with the kind

words that Finkle offers him, and "al$man opens his

binder to offer pictures and descriptions of some

women that are looking to marry.

Unfortunately, Finkle looks at the pictures, hears

"al$manAs descriptions and decides that none of

these women is for him. 6ne is too old, one is a

widow, anotherAs father is a stomach specialist and

none of them really entices Finkle. 6f course,

"al$man argues and tells him that these are all fine

women who would make him very happy, but Finkle

disapproves of all of them and, in frustration, sends

"al$man away.

&he next day, Leo Finkle is pondering his decision

not to see any of the women that "al$man offered

and wonders whether he made the right choice.

'owever, "al$man appears at his door that very

same night and says that Lily 'irschorn, a KH%year%

old woman that he mentioned the previous day, is

actually only H> and, therefore, not too old for

Finkle. 6f course, Finkle is immediately suspicious

and suspects that "al$man is lying in order to make

him meet the woman, but Finkle decides to pay her a

visit anyway.

Leo Finkle and Lily 'irschornAs evening together is

unfortuntely, a disaster. Not only is Lily at least K?

years old, but also she seems to have an idea that

Finkle is some sort of eminently holy man who can

see into the mind of 9od. &hough Finkle is

comfortable with her at first, Lily turns the

conversation to FinkleAs studies with a clear

expectation that he will help her see into his

understanding of divine truths. 6bviously, "al$man

built up Finkle as some sort of mystic or prophet,

and Finkle cannot provide her with any of the

answers that she is looking for. 2n fact, when Lily

asks Finkle why he learned to love 9od, Finkle hears

himself say, B2 came to 9od not because 2 loved 'im,

but because 2 did not.B I=HJ &his is not the answer

Lily is looking for and the evening ends in

disappointment for both of them.

&he next day, Leo Finkle is furious at "al$man for

lying to both him and Lily. 'owever, the more Finkle

thinks about it, the more he reali$es that he is

furious at himself. -fter all, he should be able to

meet women on his own, but his complete inability

to have a real social life and his total ineptitude with

women has forced him to speak with a marriage

broker in order to find a wife. 'owever, the thing

that really angers Finkle is the reali$ation that he is

studying to be a rabbi because he does not love 9od,

which he only came to understand when he was

speaking with Lily 'irschorn. Furthermore, Finkle

has never loved anybody, except for his parents, and

no one has ever loved him. &hus, he finds himself

unloved, loveless and very, very lonely.

6ver the next two weeks, Finkle neglects his studies

and neglects to take care of his self as he begins to do

some serious soul%searching. &hough he considers

dropping out of the Yeshivah, he does finally

determine that he should continue his studies and

finish school, as planned. 'owever, he still needs to

find a wife, but he is not going to use "al$man to do

it for him.

&he night that Finkle decides he does not needs

"al$man, the matchmaker himself appears with a

new batch of photographs. 6f course, "al$man first

asks about Lily, but Finkle accuses "al$man of lying

to both him and Lily. "al$man apologi$es profusely

and offers explanations, but Finkle tells him that he

is in search of love, not a convenient marriage

partner. 6f course, "al$man offers him an envelope

of photos to look at, but Finkle wants nothing to do

with it. 'owever, before Finkle can give the photos

back to him, "al$man rushes out the door.

&he month turns to +arch and Finkle makes plans

to have a real social life so that he can fall in love.

'owever, it never materiali$es and Finkle reali$es

that he is simply not in a situation that allows him to

go out and meet women. -fter all, he is a poor

university student who studies diligently and he has

neither the time nor the funds to spend on evenings

out. &hus, as he comes to grips with his plight, he

opens "al$manAs envelope of pictures.

-s Finkle looks through the pictures, he reali$es that

there is nobody in there who interests him. &hey are

all tired old women who are past their prime, *ust

like Lily 'irschorn, and Finkle, frustrated, puts the

pictures back into the envelope. 'owever, as Finkle

puts the pictures back in, a small picture that he had

not noticed falls out.

.hen Finkle sees the picture, he reali$es that he has

found the woman he is looking for. "he is young,

beautiful and alive in a way that he cannot describe.

&hough she looks familiar, Finkle knows that he

would have remembered meeting such a woman

and, therefore, they must have never met. 'owever,

he knows that he must meet this mystery woman

and he immediately runs out to talk to "al$man.

.hen Finkle arrives at "al$manAs home, his wife

informs Finkle that her husband is out. 'owever,

Finkle leaves a message telling "al$man to come

over. &hen, surprisingly, "al$man is waiting at

FinkleAs door when he returns.

-fter Finkle provides "al$man with tea and a sardine

sandwich, he shows "al$man the picture and says

that he wants to meet that particular woman.

'owever, "al$man is shocked and refuses, though he

does not explain why at first. .hen Finkle presses

"al$man to let him meet the woman that "al$man

says that the picture is of his daughter "tella, and she

is dead to him and she should rot in hell.

-fter "al$man leaves, Finkle is so shocked by the

revelation that he hides in bed, trying to get "tella

+

out of his mind. Unfortunately, he cannot. For days,

he is tortured with longing for her, though he tries to

beat his feelings down and forget the image of the

woman he loves. 'owever, instead of destroying his

feelings, he decides that it is up to him to convert her

to goodness and bring her back to 9od. &hus, when

Finkle meets "al$man in a cafeteria in the 7ronx, he

convinces "al$man to arrange a meeting and let him

try to help "tella.

Finally, the night arrives that Finkle is to finally

meet "tella. &hey are to meet on a corner under a

streetlight and Finkle brings a bou!uet of flowers for

her. &hen, when Finkle sees her in person, he runs

toward this shy, yet confident woman that he has

loved since he saw her picture. 'owever, *ust around

the corner, #inye "al$man chants prayers for the

dead.

Characters

Leo Finkle

Leo Finkle has spent the last six years studying to

become a rabbi at New York,s Yeshivah University.

7ecause he believes that he will have a better chance

of getting employment with a congregation if he is

married, Leo consults a professional matchmaker.

Leo is a cold person; he comes to reali$e that /he did

not love 9od so well as he might, because he had not

loved man.1 .hen Finkle falls in love with "al$man,s

daughter, "tella, the rabbinical student must

confront his own emotional failings.

Lily Hirschorn

Lily 'irschorn is introduced to Leo Finkle, the

rabbinical student, by #inye "al$man, the

matchmaker. "he is a schoolteacher, comes from a

good family, converses on many topics, and Leo

considers her /not unpretty.1 2t soon becomes clear,

however, that the match between them will not

work.

Pinye Salzman

Leo consults #inye "al$man, who is a professional

matchmaker. "al$man is an elderly man who lives in

great poverty. 'e is unkempt in appearance and

smells of fish. .hile "al$man works to bring couples

together, Leo has reason to believe that the

matchmaker, or /commercial cupid,1 is occasionally

dishonest about the age and financial status of his

clients. "al$man seems greatly dismayed when Leo

falls in love with "tella. Yet Leo begins to suspect

that #inye, whom he thinks of as a /trickster,1 had

/planned it all to happen this way.1

Stella Salzman

"tella "al$man is the daughter of #inye "al$man, the

matchmaker. "al$man has disowned his daughter,

evidently because she has committed some grave act

of disobedience. .hen Leo, who has fallen in love

with "tella, asks her father where he might find her,

the matchmaker replies4 /"he is a wild one G wild,

without shame. &his is not a bride for a rabbi.1 .hen

he finally meets "tella she is smoking, leaning

against a lamp post in the classic stance of the

prostitute, but Leo believes he sees in her eyes /a

desperate innocence.1

Themes

Identity

+alamud,s Leo Finkle is a character trying to figure

out who he really is. 'aving spent the last six years

of his life deep in study for ordination as a rabbi, he

is an isolated and passionless man, disconnected

from human emotion. .hen Lily 'irschorn asks

him how he came to discover his calling as a rabbi,

Leo responds with embarrassment4 /2 am not a

talented religious person. . . . 2 think . . . that 2 came

to 9od, not because 2 loved him, but because 2 did

not.1 2n other words, Leo hopes that by becoming a

rabbi he might learn to love himself and the people

around him. Leo is in despair after his conversation

with Lily because /. . . he saw himself for the first

time as he truly was G unloved and loveless.1

-s he reali$es the truth about himself, he becomes

desperate to change. Leo determines to reform

himself and renew his life. Leo continues to search

for a bride, but without the matchmaker,s help4 /. . .

he regained his composure and some idea of purpose

in life4 to go on as planned. -lthough he was

imperfect, the ideal was not.1 &he ideal, in this case,

is love. Leo comes to believe that through love G the

love he feels when he first sees the photograph of

"tella "al$man G he may begin his life anew, and

forge an identity based on something more positive.

.hen at last he meets "tella he

/pictured, in her, his own redemption.1 &hat

redemption, the story,s ending leads us to hope, will

be Leo,s discovery through "tella of an identity based

on love.

God and Religion

(entral to +alamud,s /&he +agic 7arrel1 is the idea

that to love 9od, one must love man first. Finkle is

uncomfortable with Lily,s !uestions because they

make him reali$e /the true nature of his relationship

to 9od.1 'e comes to reali$e /that he did not love

9od as well as he might, because he had not loved

man.1 2n spite of the $eal with which he has pursued

his rabbinical studies, Leo,s approach to 9od, as the

narrative reveals, is one of cold, analytical

formalism. Unable fully to love 9od,s creatures, Leo

Finkle cannot fully love 9od.

6nce again, the agent of change in Leo,s life seems to

be "tella "al$man. &he text strongly implies that by

loving "tella, by believing in her, Leo will be able to

come to 9od. ust before his meeting with "tella,

Leo /concluded to convert her to goodness, him to

1,

9od.1 &o love "tella, it seems, will be Leo,s true

ordination, his true rite of passage to the love of 9od.

Toics !or Further Study

.hen did ewish people settle in large

numbers in New York (ity0 3escribe the

ewish communities in New York (ity or in

another large -merican city. 2n what way

can /&he +agic 7arrel1 be read as a story

about the descendants of immigrants0

2n chapter twenty of the 7ook of 5xodus in

the 7ible, +oses sets forth the &en

(ommandments to the 2sraelites. 3o the

characters in /&he +agic 7arrel1 follow the

(ommandments0 .hat does this say about

them0

.hat does the story suggest about the

relation between love and self%knowledge0

.hat must Leo Finkle learn about himself

before he is truly able to love0

Style

Point o! "ie#

#oint of view is a term that describes who tells a

story, or through whose eyes we see the events of a

narrative. &he point of view in +alamud,s /&he

+agic 7arrel1 is third person limited. 2n the third

person limited point of view, the narrator is not a

character in the story, but someone outside of it who

refers to the characters as /he,1 /she,1 and /they.1

&his outside narrator, however, is not omniscient,

but is limited to the perceptions of one of the

characters in the story. &he narrator of the story

views the events of the story through the eyes of Leo

Finkle even though it is not Leo telling the story.

Sym$olism

"ymbolism is a literary device that uses an action, a

person, a thing, or an image to stand for something

else. 2n +alamud,s /&he +agic 7arrel1 the coming of

spring plays an important symbolic role. &he story

begins in February, /when winter was on its last

legs,1 and ends /one spring night1 as Leo approaches

"tella "al$man under a street lamp. &he story,s

progression from winter to spring is an effective

symbol for the emotional rebirth that Leo undergoes

as he struggles to grow as a human being.

Idiom

2diom may be defined as a speciali$ed vocabulary

used by a particular group, or a manner of

expression peculiar to a given people. 2n other

words, different groups of people speak in different

ways. .hile the narrator and most of the characters

in /&he +agic 7arrel1 speak standard 5nglish, #inye

"al$man, the matchmaker, speaks Yiddish. .ritten

in 'ebrew characters and based on the grammar of

medieval 9erman, Yiddish was the common

language of many 5uropean ewish communities. -

8ussian ew at the turn of the century I+alamud,s

father, for exampleJ might read the &orah in

'ebrew, speak to his gentile neighbors in 8ussian,

and conduct the affairs of his business and

household in Yiddish.

"ince .orld .ar 22, Yiddish has become less

prevalent in 5urope and in the immigrant ewish

communities of North -merica. 2n another

generation, it may totally die out. +any of

+alamud,s characters, however, still use the idiom.

.hen "al$man asks Leo, /- glass tea you got,

rabbi01; when he exclaims, /what can 2 say to

somebody that he is not interested in school

teachers01; and when he laments, /&his is my baby,

my "tella, she should burn in hell,1 the reader hears

an idiomatic version of 5nglish seasoned with the

cadences of Yiddish speech.

Historical Conte%t

+alamud,s /&he +agic 7arrel1 was first published

by the Partisan Review in =>?C and reprinted as the

title story in +alamud,s first volume of short fiction

in =>?@. &he period between those two dates was an

eventful time in -merican history. 2n =>?C the

United "tates "upreme (ourt unanimously re*ected

the concept of segregation in the case of Brown v.

Board of Education, which found that the practice of

maintaining separate classrooms or separate schools

for black and white students was unconstitutional.

2n the same year "enator oseph +c(arthy was

censured by the "enate for having un*ustly accused

hundreds of -mericans of being communists. 2n

=>?F the "oviet Union launched "putnik, the first

satellite to successfully orbit the earth, sparking

concern that the "oviets would take control of space.

.hile the text of /&he +agic 7arrel1 is almost

entirely free of topical or historical references that

might allow readers to place the events of the story

at a particular date, one detail establishes Leo,s

encounter with "al$man as taking place roughly at

the time of the story,s publication in the mid%fifties.

Finkle is about to complete his six%year course of

study to become a rabbi at New York (ity,s Yeshivah

University. Yeshivah, in 'ebrew, means a place of

study. Yeshivah University is the oldest and most

distinguished ewish institution of higher learning

in the United "tates. .hile its history goes back to

=@@E, the school was not named Yeshivah until =>C?,

when its charter was revised. -t the end of the

traditional six years of study to become a rabbi, then,

Leo would probably be considering marriage

sometime early in the =>?Ds.

7y consulting a professional matchmaker to find a

bride, Leo is acting more like his immigrant

grandparents than an -merican ew of the =>?Ds. 2n

Yiddish, the secular language of many 5uropean and

-merican ewish communities, the word for

/matchmaker1 is shadchen Ipronounced shod%hunJ.

7efore the seventeenth century, the shadchen was a

highly respected person, responsible for the

11

perpetuation of the ewish people through arranged

marriages. -s 5uropean ewish communities grew

larger and as modern secular notions of romantic

love became pervasive, professional matchmakers

became less scrupulous in their dealings and were

fre!uently the ob*ects of satire and derision. 2ndeed

a wealth of humor at the expense of

the shadchen developed during the nineteenth and

twentieth centuries; representative is the remark of

the Yiddish writer "holom -leichem I=@?>%=>=EJ,

who !uipped that the shadchen was best defined as

/a dealer in livestock.1

8egardless, the shadchen tradition survived ewish

immigration to the United "tates. 2n his history of

ewish immigrant life on New York (ity,s lower east

side, World of our Fathers, 2rving 'owe describes

the typicalshadchen as similar to +alamud,s #inye

"al$man4 /-ffecting an ecclesiastic bearing, the

matchmaker wore a somber black suit with a half%

frock effect, a silk yarmule IskullcapJ, a full beard.1

&he matchmaker, according to 'owe, /customarily

received ? percent of the dowry in addition to a flat

fee, neither one nor both enough to make him rich.1

#inye "al$man is in many ways, then, a stereotypical

figure who has stepped from the world of ewish oral

humor into the pages of +alamud,s story. Leo, in

seeking the shadchen!s help in the =>?Ds, reveals

himself not only as a formal, but as a very old

fashioned young man.

Critical &'er'ie#

.hen +alamud,s /&he +agic 7arrel1 first appeared

in Partisan Review in =>?C, it provided a colorful

glimpse into the world of -merican ews. Fours

years later, after his second novel, The "ssistant, had

been enthusiastically received, +alamud reprinted

/&he +agic 7arrel1 as the title story in a collection of

his short fiction. &he collection sold well, and was

praised by reviewers for its honesty, irony, and acute

perception of the moral dilemmas of -merican ews.

2t won the National 7ook -ward for fiction in =>?>.

7etween the publication of the collection in =>?@ and

his death in =>@E, 7ernard +alamud became one of

-merica,s most respected writers of fiction,

publishing six more novels and numerous collections

of short fiction. +alamud,s writing has been the

sub*ect of critical debate for three decades. .riting

in =>EE, "idney 8ichman examines the emotional

sterility of the protagonist Leo Finkle. -ccording to

8ichman, /. . . Finkle knows the word but not the

spirit; and he makes it clear that in a secret part of

his heart he knows it.1

&heodore (. +iller, in =>FH, compares /&he +agic

7arrel1 to 'awthorne,s The #carlet $etter, pointing

out that both stories explore /the love of the minister

and the whore.1 Unlike 'awthorne,s minister,

-rthur 3immesdale, however, +alamud,s rabbinical

student, Finkle, /comes to accept "tella for the

reason that he accepts universal guilt.1 +iller also

contends that "al$man has arranged the love affair

between Leo and "tella because he wishes /to initiate

Leo Finkle into the existential nature of love.1 .hen

at the end of the story "al$man says %addish, the

traditional ewish prayer for the dead, he is

/commemorating the death of the old Leo who was

incapable of love. 7ut he is also celebrating Leo,s

birth into a new life.1

7oth 8ichard 8eynolds and 7ates 'offer offer

interpretations of /&he +agic 7arrel1 based on

specific ewish religious traditions. 8eynolds,s focus

is on the role of %addish, maintaining that "al$man

hopes that Leo will bring "tella, /the prodigal

daughter,1 back to a moral life. 2n that case, reciting

the %addish is particularly appropriate given the

ancient prayer,s emphasis on resurrection. 'offer

compares the five%part structure of the story to the

&orah Ithe first five books of the 6ld &estament, the

sacred text of udaismJ and claims that Leo has

broken a ma*ority of the ten commandments.

Finally (armen (ramer maintains that Leo,s story is

a *ourney of emotional maturity. 8ather, /&he +agic

7arrel1 chronicles the rabbinical student,s

/-mericani$ation,1 his gradual assimilation into

-merican culture. (ramer asserts that Finkle

/possesses few of the typical -merican traits G

decisiveness, emotionality, action%orientation G but

he melts into the -merican pot by the end of

7ernard +alamud,s polished piece of writing. . . .1

Comare ( Contrast

)*+,s- 3ecades of immigration from

5astern and .estern 5urope have led to a

considerable ewish population in the

United "tates. "trong and vibrant ewish

communities thrive in many -merican

cities. Yet discrimination against the ewish

people exists.

)**,s- &hrough intermarriage and

assimilation, many people in the ewish

community believe that ewish culture is

endangered. Unfortunately, discrimination

still exists in the United "tates, but many

groups fight misinformation and

discrimination against ews.

)*+,s- &he ewish matchmaker, also

known as the /shadchen,1 performs a vital

function within the community. -rranged

marriage, although losing popularity among

ewish families, is still a viable option for

young ewish men and women of age.

)**,s- +atchmaking is considered an

anti!uated tradition. 2t is mainly used in

orthodox ewish communities, as other

networking opportunities allow ewish men

and women to meet and find possible

marriage partners.

12

Criticism

Freud invoes the conce&t of reaction formation' a

thing consumed (or almost consumed) *y its o&&osite.

The third caset and the third daughter have *een

transformed into the &ri+es. Yet, says Freud, lead

seems dull as com&ared to gold and silver ,ust as

-ordelia lavishes no &raise on her father and then

dies. "ccording to Freud, her death.all death.is the

underlying wager of such inter&retive choices. To

return to its mythic origins, #haes&eare/s story

harens *ac to the *ifurcation of woman as the

goddess of love and the goddess of death. -ordelia

and that leaden caset a&&ear to *e what man

desires most' the unconditional love of a woman (his

mother), *ut they are *oth im*ued with the

destruction that mother earth *rings. -ordelia/s

death thus is not her own0 it is the dream image of

$ear/s own death0 1the silent 2oddess of 3eath, will

tae him into her arms.1

TH. TH.M. &F TH. THR.. C/S0.TS

I

&wo scenes from "hakespeare, one from a comedy and

the other from a tragedy, have lately given me occasion

for posing and solving a small problem.

&he first of these scenes is the suitorsA choice between

the three caskets in The Merchant of <enice. &he fair and

wise #ortia is bound at her fatherAs bidding to take as

her husband only that one of her suitors who chooses

the right casket from among the three before him. &he

three caskets are of gold, silver and lead4 the right

casket is the one that contains her portrait. &wo

suitors have already departed unsuccessful4 they have

chosen gold and silver. 7assanio, the third, decides in

favour of lead; thereby he wins the bride, whose

affection was already his before the trial of fortune.

5ach of the suitors gives reasons for his choice in a

speech in which he praises the metal he prefers and

depreciates the other two. &he most difficult task thus

falls to the share of the fortunate third suitor; what he

finds to say in glorification of lead as against gold and

silver is little and has a forced ring. 2f in psycho%analytic

practice we were confronted with such a speech, we

should suspect that there were concealed motives

behind the unsatisfying reasons produced.

"hakespeare did not himself invent this oracle of the

choice of a casket; he took it from a tale in the 9esra

fiomanorum,

=

in which a girl has to make the same

choice to win the 5mperorAs son.

H

'ere too the third

metal, lead, is the bringer of fortune. 2t is not hard to

guess that we have here an ancient theme, which

re!uires to be interpreted, accounted for and traced

back to its origin. - first con*ecture as to the meaning

of this choice between gold, silver and lead is !uickly

confirmed by a statement of "tuck%enAs,

K

who has made

a study of the same material over a wide field. 'e

writes4 B&he identity of #ortiaAs three suitors is clear

from their choice4 the #rince of +orocco chooses the

gold casketGhe is the sun; the #rince of -rragon

chooses the silver casketGhe is the moon; 7assanio

chooses the leaden casketGhe is the star youth.B 2n

support of this explanation he cites an episode from the

5sto nian folk%epic B:alewipoeg,B in which the three

suitors appear undisguisedly as the sun, moon and star

youths Ithe last being Bthe #ole%starAs eldest boyBJ and

once again the bride falls to the lot of the third.

&hus our little problem has led us to an astral mythL

&he only pity is that with this explanation we are not at

the end of the matter. &he !uestion is not exhausted,

for we do not share the belief of some investigators that

myths were read in the heavens and brought down to

earth; we are more inclined to *udge with 6tto 8ank

C

that they were pro*ected on to the heavens after having

arisen elsewhere under purely human conditions. 2t is

in this human content that our interest lies.

Let us look once more at our material. 2n the

5stonian epic, *ust as in the tale from the 2esta

8omanorum, the sub*ect is a girl choosing between the

three suitors; in the scene from The +erchant of <enice

the sub*ect is apparently the same, but at the same time

something appears in it that is in the nature of an

inversion of the theme4 a man chooses between threeG

caskets. 2f what we were concerned with were a dream, it

would occur to us at once that caskets are also

women, symbols of what is essential in woman, and

therefore of a woman herselfG like coffers, boxes, cases,

baskets, and so on.

?

2f we boldly assume that there are

symbolic substitutions of the same kind in myths as

well, then the casket scene in The +erchant of <enice

really becomes the inversion we suspected. .ith a

wave of the wand, as though we were in a fairy tale,

we have stripped the astral garment from our theme;

and now we see that the theme is a human one, a

manAs choice between three women.

&his same content, however, is to be found in another

scene of "hakespeareAs, in one of his most powerfully

moving dramas; not the choice of a bride this time, yet

linked by many hidden similarities to the choice of the

casket in &he +erchant of <enice. &he old :ing Lear

resolves to divide his kingdom while he is still alive

among his three daughters, in proportion to the amount

of love that each of them expresses for him. &he two elder

ones, 9oneril and 8egan, exhaust themselves in

asseverations and laudations of their love for him; the

third, (ordelia, refuses to do so. 'e should have

recogni$ed the unassuming, speechless love of his third

daughter and rewarded it, but he does not recogni$e

it. 'e disowns (ordelia, and divides the kingdom

between the other two, to his own and the general ruin.

2s not this once more the scene of a choice between

three women, of whom the youngest is the best, the most

excellent one0

&here will at once occur to us other scenes from

myths, fairy tales and literature, with the same

situation as their content. &he shepherd #aris has to

choose between three goddesses, of whom he declares

the third to be the most beautiful. (inderella, again, is a

youngest daughter, who is preferred by the prince to her

two elder sisters. #syche, in -puleiusAs story, is the

youngest and fairest of three sisters. #syche is, on the

one hand, revered as -phrodite in human form; on the

other, she is treated by that goddess as (inderella was

13

treated by her stepmother and is set the task of

sorting a heap of mixed seeds, which she accomplishes

with the help of small creatures Idoves in the case of

(inderella, ants in the case of #sycheJ.

E

-nyone who

cared to make a wider survey of the material would

undoubtedly discover other versions of the same theme

preserving the same essential features.

Let us be content with (ordelia, -phrodite, (inderella

and #syche. 2n all the stories the three women, of whom

the third is the most excellent one, must surely be

regarded as in some way alike if they are represented

as sisters. I.e must not be led astray by the fact that

LearAs choice is between three daughters; this may

mean nothing more than that he has to be represented

as an old man. -n old man cannot very well choose

between three women in any other way. &hus they

become his daughters.J

7ut who are these three sisters and why must the

choice fall on the third0 2f we could answer this !uestion,

we should be in possession of the interpretation we are

seeking. .e have once already made use of an

application of psycho%analytic techni!ue, when we

explained the three caskets symbolically as three

women. 2f we have the courage to proceed in the same

way, we shall be setting foot on a path which will lead

us first to something unexpected and

incomprehensible, but which will perhaps, by a

devious route, bring us to a goal.

2t must strike us that this excellent third woman has

in several instances certain peculiar !ualities besides

her beauty. &hey are !ualities that seem to be tending

towards some kind of unity; we must certainly not

expect to find them e!ually well marked in every

example. (ordelia makes herself unrecogni$able,

inconspicuous like lead, she remains dumb, she Bloves

and is silent.B

F

(inderella hides so that she cannot be

found. .e may perhaps be allowed to e!uate

concealment and dumbness. &hese would of course be

only two instances out of the five we have picked out.

7ut there is an intimation of the same thing to be

found, curiously enough, in two other cases. .e have

decided to compare (ordelia, with her obstinate

refusal, to lead. 2n 7assanioAs short speech while he

is choosing the casket, he says of lead Iwithout in any

way leading up to the remarkJ4

&hy paleness

@

moves me more than elo!uence.

&hat is to say4 B&hy plainness moves me more than the

blatant nature of the other two.B 9old and silver are

BloudB; lead is dumbG in fact like (ordelia, who

Bloves and is silent.B

>

2n the ancient 9reek accounts of the udgement of

#aris, nothing is said of any such reticence on the part

of -phrodite. 5ach of the three goddesses speaks to the

youth and tries to win him by promises. 7ut, oddly

enough, in a !uite modern handling of the same scene

this characteristic of the third one which has struck us

makes its appearance again. 2n the libretto of 6ffenbachAs

$a Belle 4elene, #aris, after telling of the solicitations of

the other two goddesses, describes -phroditeAs

behaviour in this competition tor the beauty%pri$e4

La troisieme, ah5 la troisieme . . .

$a troisieme ne dit rien.

5ie eut le prix tout de meme . . .

=D

2f we decide to regard the peculiarities of our Bthird

oneB as concentrated in her Bdumbness,B then psycho%

analysis will tell us that in dreams dumbness is a

common representation of death.

==

+ore than ten years ago a highly intelligent man told me

a dream which he wanted to use as evidence of the

telepathic nature of dreams. 2n it he saw an absent

friend from whom he had received no news for a very

long time, and reproached him energetically for his

silence. &he friend made no reply. 2t afterwards turned

out that he had met his death by suicide at about the

time of the dream. Let us leave the problem of telepathy

on one side4

=H

there seems, however, not to be any

doubt that here the dumbness in the dream

represented death. 'iding and being unfindableGa

thing which confronts the prince in the fairy tale of

(inderella three times, is another unmistakable

symbol of death in dreams; so, too, is a marked pallor,

of which the BpalenessB of the lead in one reading of

"hakespeareAs text is a reminder.

=K

2t would be very much

easier for us to transpose these interpretations from the

language of dreams to be mode of expression used in