Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Constipation in Old Age

Enviado por

Levan Lomidze0 notas0% acharam este documento útil (0 voto)

71 visualizações14 páginasThe prevalence of constipation increases with age. However, con- stipation is not a physiological consequence of normal ageing. Indeed, the aetiology of constipation in older people is often multifactorial with co-morbid diseases, impaired mobility, reduced dietary fibre intake and prescription medications contributing significantly to constipation in many instances. A detailed clinical history and physical examination including digital rectal exami- nation is usually sufficient to uncover the causes of constipation in older people; more specialized tests of anorectal physiology and colonic transit are rarely required. The scientific evidence base from which to develop specific treatment recommendations for constipation in older people is, for the most part, slim. Con- stipation can be complicated by faecal impaction and inconti- nence, particularly in frail older people with reduced mobility and cognitive impairment; preventative strategies are important in those at risk.

Título original

Constipation in old age

Direitos autorais

© © All Rights Reserved

Formatos disponíveis

PDF, TXT ou leia online no Scribd

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoThe prevalence of constipation increases with age. However, con- stipation is not a physiological consequence of normal ageing. Indeed, the aetiology of constipation in older people is often multifactorial with co-morbid diseases, impaired mobility, reduced dietary fibre intake and prescription medications contributing significantly to constipation in many instances. A detailed clinical history and physical examination including digital rectal exami- nation is usually sufficient to uncover the causes of constipation in older people; more specialized tests of anorectal physiology and colonic transit are rarely required. The scientific evidence base from which to develop specific treatment recommendations for constipation in older people is, for the most part, slim. Con- stipation can be complicated by faecal impaction and inconti- nence, particularly in frail older people with reduced mobility and cognitive impairment; preventative strategies are important in those at risk.

Direitos autorais:

© All Rights Reserved

Formatos disponíveis

Baixe no formato PDF, TXT ou leia online no Scribd

0 notas0% acharam este documento útil (0 voto)

71 visualizações14 páginasConstipation in Old Age

Enviado por

Levan LomidzeThe prevalence of constipation increases with age. However, con- stipation is not a physiological consequence of normal ageing. Indeed, the aetiology of constipation in older people is often multifactorial with co-morbid diseases, impaired mobility, reduced dietary fibre intake and prescription medications contributing significantly to constipation in many instances. A detailed clinical history and physical examination including digital rectal exami- nation is usually sufficient to uncover the causes of constipation in older people; more specialized tests of anorectal physiology and colonic transit are rarely required. The scientific evidence base from which to develop specific treatment recommendations for constipation in older people is, for the most part, slim. Con- stipation can be complicated by faecal impaction and inconti- nence, particularly in frail older people with reduced mobility and cognitive impairment; preventative strategies are important in those at risk.

Direitos autorais:

© All Rights Reserved

Formatos disponíveis

Baixe no formato PDF, TXT ou leia online no Scribd

Você está na página 1de 14

8

Constipation in old age

Paul Gallagher, MB, MRCPI, Research Fellow

*

, Denis OMahony, MD, FRCPI,

Consultant Geriatrician and Senior Lecturer in Medicine

1

Department of Geriatric Medicine, Cork University Hospital, Wilton, Cork, Ireland

Keywords:

constipation

ageing

clinical assessment

laxatives

faecal impaction

The prevalence of constipation increases with age. However, con-

stipation is not a physiological consequence of normal ageing.

Indeed, the aetiology of constipation in older people is often

multifactorial with co-morbid diseases, impaired mobility, reduced

dietary bre intake and prescription medications contributing

signicantly to constipation in many instances. A detailed clinical

history and physical examination including digital rectal exami-

nation is usually sufcient to uncover the causes of constipation in

older people; more specialized tests of anorectal physiology and

colonic transit are rarely required. The scientic evidence base

from which to develop specic treatment recommendations for

constipation in older people is, for the most part, slim. Con-

stipation can be complicated by faecal impaction and inconti-

nence, particularly in frail older people with reduced mobility and

cognitive impairment; preventative strategies are important in

those at risk.

2009 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Introduction

Constipation is a common, but subjective, symptom with numerous denitions ranging from

a simple quantitative assessment of defaecation frequency to explicit diagnostic criteria. As more than

90% of people in the Western world have between three defaecations per day and three per week [1],

many clinicians dene constipation as a reduction in defaecation frequency to fewer than three per

week [2]. However, there are difculties with an entirely quantitative denition of constipation, as

many patients tend to underestimate their stool frequency [3]. Furthermore, patients perceptions of

* Corresponding author. Tel.: 353 21 4922396; fax: 353 21 4922829.

E-mail addresses: pfgallagher77@eircom.net (P. Gallagher), denis.omahony@hse.ie (D. OMahony).

1

Tel.: 353 21 4922396; fax: 353 21 4922829.

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

Best Practice & Research Clinical

Gastroenterology

1521-6918/$ see front matter 2009 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

doi:10.1016/j.bpg.2009.09.001

Best Practice & Research Clinical Gastroenterology 23 (2009) 875887

constipation do not always relate to stool frequency but chiey pertain to qualitative symptoms such as

abdominal bloating, hard or lumpy stools, prolonged or difcult defaecation, need for manual

manoeuvres to pass stool and sensations of incomplete evacuation [4].

Diagnostic criteria attempt to standardize the denition of chronic constipation. The most widely

used are the consensus-derived Rome criteria which require a patient to have experienced at least two

of the following symptoms during the preceding three months: (i) straining during 25% of defae-

cations; (ii) lumpy or hard stools in 25% of defaecations; (iii) sensation of incomplete evacuation for

25% of defaecations; (iv) sensation of anorectal obstruction/blockage for 25% of defaecations; (v)

manual manoeuvres to facilitate 25% of defaecations (digital manipulations, pelvic oor support); (vi)

fewer than three defaecations per week [5]. In addition, the patient should have insufcient criteria for

irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and should rarely have loose stools without the use of laxatives [5]. The

criteria are applied to the previous three months, but patients must be symptomatic for at least six

months prior to diagnosis [6].

The Rome criteria are useful in research trials and as a guideline for diagnosis. However, epide-

miological studies show great disparity between the prevalence of self-reported and criteria-dened

constipation suggesting that everyday clinical application of these criteria may be restrictive [68]. In

practice, chronic constipation might be diagnosed in any patient experiencing consistent difculty

with defaecation, especially if associated with abdominal discomfort, straining at stool, and feelings of

incomplete evacuation. In frail, older patients who may be unable to communicate subjective symp-

toms because of cognitive impairment, objective assessment of stool frequency and consistency is

helpful.

The estimated prevalence of chronic constipation amongst adults of all ages ranges from 2% to 27%,

with most estimates clustering around 15%, and a female to male preponderance of 2.2:1 [9]. The

prevalence of constipation increases with age, particularly after the age of 65 years [9,10]. Between 30%

and 40% of community-dwelling older adults [1113] and over 50% of nursing home residents expe-

rience chronic constipation [14]. Between 50% and 74% of nursing home residents use laxatives daily

[4,15,16]. One study reported a 7% incidence of newly diagnosed constipation during the rst three

months of nursing home admission [17]. Chronic constipation is a signicant healthcare problem in

older people and impacts negatively on quality of life [18].

Aetiology

Some age-related changes in anorectal physiology have been described, but these are rarely the sole

cause of constipation in older people. Increased rectal compliance and impaired rectal sensation can

require larger stool volumes to trigger the defaecatory urge, with resultant difculty in evacuation of

small stools. Resting anal sphincter pressure can decline with age and may predispose to faecal

incontinence [19,20]. There is conicting evidence regarding age-related changes in colonic motility

and myoelectric activity [2123]. In general, constipation should not be regarded as a physiological

consequence of normal ageing. Indeed, most healthy older people have normal bowel function [24].

As in the general population, constipation in older people can be classied as primary (idiopathic or

functional) or secondary (iatrogenic or consequent to organic disease), the latter being more common

in older people. Primary constipation can be sub-classied into three pathophysiological groups:

normal transit constipation, slow transit constipation and disordered defaecation. However, there is

considerable overlap between these groups in terms of symptoms and prevalence, thus making it

difcult to distinguish between pathophysiological subtypes on the basis of history alone [25]. Patients

with normal transit constipation usually perceive difculty with defaecation and complain of hard

stools, abdominal pain and bloating, but stool frequency and transit time are normal [3]. Normal transit

constipation frequently overlaps with IBS, the main difference between these conditions being the

predominance of abdominal pain or discomfort in IBS.

Patients with slow transit constipation have protracted movement of faeces through the colon and

rectum with resultant symptoms of infrequent defaecation, bloating and abdominal discomfort [26].

Slowtransit can produce small, hard stools that may not cause sufcient rectal distension to trigger the

defaecatory urge [27]. This is often compounded by a higher threshold of rectal pressure required to

trigger defaecation [28]. Idiopathic slow transit constipation most commonly occurs in young women,

P. Gallagher, D. OMahony / Best Practice & Research Clinical Gastroenterology 23 (2009) 875887 876

often beginning at puberty [29]. In some, it may be due to a low bre diet causing low stool bulk and

reduced luminal distension; these patients may respond to increased dietary bre [30]. In others, there

is a primary abnormality in colonic motility that may be caused by reduced numbers of high-amplitude

peristaltic contractions which propel stool through the colon [31], defective cholinergic or adrenergic

neurotransmission [32], diminished gastrocolic reex activity [33] or, uncoordinated rectosigmoid

motor activity in the distal colon which impedes normal transit [25]. Patients with severe idiopathic

slow transit constipation often have a poor response to bre and laxatives.

Patients with disordered defaecation (outlet constipation) cannot adequately empty the rectum

during defaecation [34]. Normal defaecation requires coordinated relaxation of the external anal

sphincter and puborectalis muscles, contraction of the abdominal wall muscles and inhibition of

colonic segmenting activity. Those with functionally disordered defaecation have paradoxical

contraction of the external anal sphincter and puborectalis muscles during defaecationwhich results in

incomplete emptying of the rectum [34]. These patients often strain at stool and sometimes apply

perineal or vaginal pressure during defaecation in an effort to empty the rectum. This functional

disorder may be amenable to biofeedback therapy. Other causes of outlet constipation include

anatomic problems such as rectal wall prolapse, rectocoele or solitary rectal ulcer which can impede

the passage of stool, and prolonged avoidance of defaecation because of the pain associated with an

anal ssure, abscess, perianal thrombosis, or even the passage of a large, hard stool [25]. Childbirth, and

excessive straining at stool over years, can cause perineal laxity and sacral nerve injury with resultant

reduction in rectal sensation and subsequent incontinence [35].

Secondary causes of constipation in older people include pathological conditions (Table 1) and

medications (Table 2). Autonomic neuropathies associated with diabetes, Parkinsons disease, and

paraneoplastic syndromes can delay colonic transit as can medications such as opioids and those with

anticholinergic properties. Other contributory factors to the higher prevalence of constipation in older

people include poor dietary bre and caloric intake, immobility, weak abdominal and pelvic muscles

and cognitive impairment.

Complications of constipation in older people

The major complications of constipation in older people are faecal impaction and faecal inconti-

nence. Faecal impaction refers to accumulation of hardened faeces in the rectum or colon. The faecal

mass can cause diminished rectal sensation and resultant faecal incontinence [36]. Liquid stools from

the proximal colon can bypass the impacted stool causing paradoxical diarrhoea. Liquefaction of the

outer surface of an impacted faecal mass can also cause diarrhoea; this may be mediated by increased

rectal mucus production in response to an indurated faecal mass. In severe cases, faecal impaction can

cause intestinal obstruction or even colonic (stercoral) ulceration. Faecal impaction can cause delirium

and urinary retention with associated risk of urinary tract infection. Risk factors for faecal impaction

include prolonged immobility, cognitive impairment, spinal cord disorders and colonic neuromuscular

disorders. Unfortunately, faecal impaction is often overlooked in older people, although the diagnosis

can usually be made by digital rectal examination. Enemas and laxatives are used to treat faecal

impaction though manual disimpaction is sometimes necessary [37,38]. Prevention of faecal impaction

is important in those at risk: dietary measures, regular toileting and prophyllactic laxatives are usually

required [38]. Other complications of constipation in older people are related to excessive straining

which can contribute to haemorrhoids, anal ssures and rectal prolapse. Excessive straining can affect

the cerebral and coronary circulations with resultant syncope or cardiac ischaemia.

Clinical evaluation

History and physical examination

It is essential to perform a thorough medical history in older patients complaining of constipation.

The clinician should enquire specically about (i) the patients perceptions of normal bowel habit; (ii)

onset and duration of symptoms; (iii) defaecation frequency; (iv) colour, size and volume of stool; (v)

rectal bleeding or pain; (vi) weight loss; (vii) straining with passage of stool; (viii) abdominal pain or

P. Gallagher, D. OMahony / Best Practice & Research Clinical Gastroenterology 23 (2009) 875887 877

bloating; (ix) faecal soiling or diarrhoea and (x) need for digital manipulation during defaecation.

Careful attention should be paid to the identication of organic and iatrogenic causes of constipation

including prescription medications and over-the-counter preparations such as antihistamines, opiates

(codeine, loperamide, diphenoxylate), iron supplements, and aluminium-based antacids. Difculties

with chewing, swallowing, diet and mobility should be identied. Screening tests for cognitive func-

tion, depression and anxiety may also uncover contributing factors.

A complete physical examination can identify systemic causes of constipation e.g. metabolic or

neuromuscular disorders. The mouth should be inspected for poor dentition or oral lesions which can

interfere with dietary intake. The abdomen should be examined for distension, pain, tenderness,

masses, hernias and bowel sounds. Acute or subacute bowel obstruction and ileus should be outruled.

All older patients presenting with constipation should have a rectal examination. The perianal area

should be inspected for excoriation, skin tags, haemorrhoids, stulas, ssures, anocutaneous reex and

rectal prolapse during straining. The perineum should be observed at rest and while the patient is

bearing down to determine the extent of perineal descent, usually between 1.0 cmand 3.5 cm. Reduced

perineal descent may indicate an inability to relax the pelvic-oor muscles during defaecation.

Table 1

Medical disorders that can cause constipation.

Endocrine or metabolic disorders

Addisons Disease

Diabetes Mellitus

Hypercalcaemia

Hypocalcaemia

Hypokalaemia

Hypermagnesaemia

Hyperparathyroidism

Hypoparathyroidism

Hypothyroidism

Uraemia

Gastrointestinal disorders

Colorectal carcinoma

Extrinsic colonic

compression (e.g. from a tumour)

Diverticular disease

Colonic stricture

(inammatory, diverticular, ischaemic, radiotherapy)

Rectal prolapse

Rectocoele

Volvulus

Megacolon

Megarectum

Haemorrhoids

Anal ssure

Neurological disorders

Autonomic neuropathy

Parkinsons disease

Cerebrovascular disease

Multiple sclerosis

Dementia

Spinal cord lesion

Guillain-Barre Syndrome

Myopathic Disorders

Amyloidosis

Dermatomyositis

Systemic sclerosis

Psychogenic disorders

Anxiety

Depression

Somatization

P. Gallagher, D. OMahony / Best Practice & Research Clinical Gastroenterology 23 (2009) 875887 878

Excessive perineal descent (belowthe level of the ischial tuberosities or >3.5 cm) may indicate perineal

laxity, which could be contributing to outlet constipation.

Anal sphincter tone should be assessed at rest and during anal squeeze. Difculty inserting the

nger into the anal canal may suggest elevated anal sphincter pressure or an anal stricture. A lax anal

sphincter may be due to trauma or a neurological disorder. Anal canal pain or reex anal spasm may

indicate an anal ssure or abscess. Rectal examination can identify masses and faecal impaction,

though the presence of an empty rectal vault does not exclude the possibility of a higher stool

impaction in the rectumor sigmoid colon. Stool, if present, should be characterized for consistency and

assessed for occult blood. A defect in the anterior wall of the rectum might be suggestive of a rec-

tocoele. Tenderness on palpation of the posterior rectal wall could indicate puborectalis muscle spasm.

Investigation

Older patients presenting with constipation should have basic laboratory testing including a full

blood count to exclude anaemia, thyroid function tests to exclude hypothyroidism, and serum glucose,

calcium and electrolytes to exclude the relevant metabolic disorders [39,40]. However, evidence to

support routine laboratory testing in patients of any age with chronic, uncomplicated constipation is

lacking [41]. Similarly, there is a lack of evidence to support the use of radiography in the routine

evaluation of older patients with constipation, though plain abdominal radiography is often helpful

when there is a clinical suspicion of high stool impaction, megacolon or bowel obstruction. As in other

age groups, the search for intrinsic lesions of the colon by endoscopy should be guided by the nature

and duration of the history and the presence or absence of red ag features suggestive of organic

disease e.g. a recent change in bowel habit, rectal bleeding, iron deciency anaemia or unintentional

weight loss [39]. Routine colonoscopy for patients with chronic, uncomplicated constipation in the

absence of these features is not recommended [42].

More specialized tests of colonic transit or pelvic oor function should only be considered for older

patients with severe, intractable constipation who do not have a secondary cause of constipation or in

whom an adequate trial of high-bre diet and laxatives is unsuccessful [43]. In older patients with

symptoms and signs suggestive of a defaecatory disorder, anorectal manometry and balloon expulsion

tests shouldonly be consideredif theyare going toaffect management decisions. Anorectal manometry is

performed by inserting a pressure-sensitive catheter through the anal canal to measure rectal sensation,

rectal compliance, anorectal reexes and sphincter pressures [43]. In the balloon expulsion test, a latex

balloonis inserted into the rectumandlledwithwater or air; failure to expel the balloonwithin1 min is

suggestive of a defaecatory disorder [43]. If the results of anal manometry or balloon expulsion tests are

equivocal, or if there is a clinical suspicion of a structural rectal abnormality that hinders defaecation,

defaecography or pelvic magnetic resonance imaging can be used to assess the functional anatomy

Table 2

Drugs associated with constipation in older people.

Commonly implicated

Antacids (aluminium or calcium-containing)

Anticholinergics (e.g. oxybutinin, tolterodine, trospium chloride)

Antidepressants (tricyclic antidepressants, monoamine oxidase inhibitors)

Antihistamines with antimuscarinic properties (diphenhydramine, chlorpheniramine)

Antispasmodics (e.g. hyoscine, dicyclomine, propantheline)

Calcium channel blockers

Calcium supplements

Diuretics

Neuroleptics with antimuscarinic properties e.g. chlorpromazine, triuoperazine

Opiate analgesics

Oral iron

Less commonly implicated

Anticonvulsants

Antiparkinsonian drugs (bromocriptine, amantadine, levodopa, pramipexole)

Non-steroidal anti-inammatory drugs

P. Gallagher, D. OMahony / Best Practice & Research Clinical Gastroenterology 23 (2009) 875887 879

during defaecation [43,44]. In older patients with refractory primary constipation without signs and

symptoms of a defaecatorydisorder, colonic transit time canbe assessed, thoughthis is of limitedvalue as

specic interventions, apart from colectomy, are unavailable. The simplest method to measure colonic

transit involves ingestion of a capsule containing radio-opaque markers followed by a plain abdominal

radiograph 5 days later. If more than 20% of the markers remain, colonic transit is delayed [45].

Management

The aims of treatment are to relieve symptoms, to restore normal bowel habit i.e. the passage of

a soft, formed stool at least three times a week without straining, and to improve quality of life with

minimal adverse effects. This can be achieved in most older patients with dietary and behavioural

modications and judicious use of laxatives and enemas. Specialized treatments such as biofeedback

for patients with defaecatory disorders and subtotal colectomy for those with severe slow transit

constipation are rarely required. Medications that cause constipation should be replaced with

appropriate alternatives where possible e.g. a calcium antagonist could be replaced with an angio-

tensin converting enzyme inhibitor to treat hypertension; a tricyclic antidepressant could be replaced

with a selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitor to treat depression. If a constipating medication cannot

be discontinued (e.g. opioid for severe chronic pain or antiparkinsonian drugs), then a prophylactic

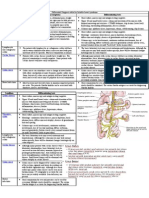

laxative should be considered. An algorithmfor the assessment and initial management of constipation

in older adults is presented in Fig. 1. However, it must be emphasized that the evidence base supporting

these recommendations in older people is lacking.

Dietary and behavioural modications

It is generally recommended that dietary bre should be increased to 2025 g per day in most older

patients with constipation. The best way to add bre is by making subtle and gradual changes to the

diet with foods that are high in residual bre e.g. bran and other whole grains, fruits, vegetables or nuts.

Fibre increases stool bulk and plasticity, which causes colonic distension and promotes stool

propulsion. The effect of increasing dietary bre is not immediate: patients should observe a gradual

increase in bowel movement frequency over some weeks. Bloating and atulence can occur, but

usually resolve with continued use. Faecal impaction should be treated before increasing dietary bre.

Fibre supplementation should be avoided inpatients with idiopathic megacolon, megarectumor bowel

obstruction as these patients actually require a bre-restricted diet with regular laxatives or enemas to

minimise the risks of faecal retention and impaction [46].

Older patients with chronic constipation are often advised to increase their uid intake. However,

there is no scientic evidence to support this advice and caution is required when increasing uids in

older patients with renal or cardiac failure [47]. Similarly, regular exercise is frequently recommended

for management of constipation, though there is insufcient evidence to support this [48]. Nonethe-

less, exercise should be encouraged for all older people as it is associated with a wide range of health

benets. It is important to establish a routine that promotes normal bowel function in older patients

with constipation. This should take advantage of the gastrocolic reex, which, for most individuals, is

most pronounced after breakfast or supper. The need to respond as soon as possible to the urge to

defaecate must be emphasized. It is also important to ensure that older people have privacy and

adequate time for bowel movements.

Responses to dietary and behavioural modications should be measured using a stool diary or

scoring systems such as the Bristol Stool Scale [49]. Patients with normal transit constipation usually

have a good response to a therapeutic trial of dietary bre. Those with a poor response to dietary bre

may have slow transit constipation or a defaecatory disorder and should receive a therapeutic trial of

laxatives.

Laxatives

Laxatives are amongst the most commonly used medicines in the general population [50]. However,

the evidence base supporting their use, particularly in older people, is often poor [51]. A systematic

P. Gallagher, D. OMahony / Best Practice & Research Clinical Gastroenterology 23 (2009) 875887 880

review of randomized controlled trials evaluating treatments for constipation prior to 2005 concluded

that there is little evidence to support the use of many laxatives in patients with chronic constipation

with the exception of lactulose and polyethylene glycol, which were found to be effective at improving

stool frequency and consistency (Table 3) [39]. These recommendations did not include lubiprostone,

which was approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration in 2006. Laxatives can be

Fig. 1. Assessment and management of the older patient with constipation.

P. Gallagher, D. OMahony / Best Practice & Research Clinical Gastroenterology 23 (2009) 875887 881

classied into bulking agents, osmotic laxatives, stimulant laxatives, stool softeners, and chloride

channel activators.

Bulk-forming laxatives (bre supplements)

The principal bulk-forming laxatives are psyllium (ispaghula), bran, methylcellulose and calcium

polycarbophil. These hydrophilic agents absorb water fromthe intestinal lumen thereby softening stool

consistency and increasing stool bulk. They take several days to have an effect. They are most effective

in patients with normal transit constipation; the majority of patients with slow transit constipation or

disordered defaecation will have a poor response [52].

Bulk-forming laxatives are generally not required in older people unless bre cannot be increased in

the diet. Adequate uid intake must be maintained when taking bulking agents to avoid mechanical

obstruction; this may require supervision in frail patients. Other adverse effects include bloating,

atulence and abdominal pain which are more common with psyllium (attributed to bacterial

degradation of natural bre) than with methylcellulose (a semisynthetic bre) and polycarbophil (an

entirely synthetic polymer of acrylic acid) [53]. These adverse effects may limit tolerability in older

people. Bulk-forming laxatives can interfere with absorption of several commonly-prescribed medi-

cations in older people including warfarin, digoxin, aspirin, iron and calcium. The ACG chronic

constipation task force concluded that there was Grade B evidence to support the use of psyllium, bran

and methylcellulose in the treatment of constipation [39].

Osmotic laxatives

Osmotic laxatives (polyethylene glycol, lactulose, sorbitol and saline laxatives) increase the amount

of water in the large bowel, either by osmotic secretion of water into the intestinal lumen or by

retaining the uid they were administered with. This results in a softer stool and improved peristalsis.

Polyethylene glycol

Polyethylene glycol (PEG) is a non-absorbable, iso-osmotic laxative that binds water molecules. It is

not metabolised by colonic bacteria. It generally has an effect within 2448 h. Many well-designed,

randomized, controlled studies have demonstrated the sustained and positive effect of PEG in treating

chronic constipation [5461] though only a minority included a proportion of patients aged 65 years

[54,55,60]. An open-label trial found PEG to be superior to lactulose for increasing stool frequency and

reducing straining [62]. PEGis also effective in the treatment of faecal impaction at a dose of 100 g in 1 L

of water per day for up to three days [37]. Adverse effects of PEG include nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea at

high doses, atulence, abdominal cramps and rarely, pulmonary oedema, the precise mechanism of

Table 3

American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) graded recommendations for treatments of chronic constipation [39].

Grade Support Evidence Agents

A Evidence from 2 level I trials

without conicting evidence

from other level 1 trials

Level 1: RCTs with p < 0.05, adequate

sample size; appropriate

methodology (high-quality)

Polyethylene glycol (PEG)

Lactulose

B Evidence from a single

level 1 trial

or 2 level 2 trials

with conicting evidence

from other level 1 trials

or 2 level 2 trials

Level 2: RCTs with p > 0.05, or inadequate

sample size, or inappropriate

methodology (intermediate quality)

Psyllium

Bran

Methylcellulose

Polycarbophil

Magnesium hydroxide

Stimulant laxatives

C Recommendations based

on level 35 evidence

Level 3: non-RCTs

with contemporaneous controls

Level 4: non-RCTs

with historical controls

Level 5: case series

Herbal supplements

Alternative treatments

Lubricants

Combination Laxatives

RCT Randomized controlled trial.

P. Gallagher, D. OMahony / Best Practice & Research Clinical Gastroenterology 23 (2009) 875887 882

which is unclear [63]. It is thought that the osmotic properties of PEG can induce pulmonary oedema

when aspirated into the lungs [63]. PEG should therefore be used with caution in older patients at risk

of aspiration. No clinically signicant drug interactions with PEG have been reported.

Lactulose

Lactulose is a non-absorbable synthetic dissacharide which is metabolised by colonic bacteria into

lactic acid and other organic acids which are then absorbed by the colonic mucosa. The osmotic effect

of lactulose usually occurs after 4872 h and results in increased colonic peristalsis. Adverse effects

include bloating and atulence [53]. A study of 47 nursing home residents (mean age 84 years) found

that lactulose was superior to placebo in terms of increasing stool frequency and reducing the prev-

alence of faecal impaction [64]. The lactulose group needed fewer enemas than the control group and

no adverse clinical or laboratory effects were noted [64]. An open-label, parallel study that compared

lactulose, psylliumand placebo suggested that both laxatives were equally effective in the treatment of

constipation [65].

Sorbitol

Sorbitol is a non-absorbable, hyperosmolar sugar alcohol. Sorbitol and lactulose were shown to be

equally effective in treating constipation in a small sample of 30 men aged 6586 years [66].

Saline laxatives (magnesium salts)

No randomized, placebo controlled trials have been conducted with magnesium products in

patients of any age with chronic constipation. Saline laxatives are therefore not recommended for

treatment of chronic constipation in older people. Adverse effects of magnesium include atulence,

abdominal cramps and magnesium toxicity [53]. Hypermagnesaemia may cause paralytic ileus which

in itself can cause constipation. Magnesium can interfere with absorption of certain drugs including

digoxin, chlorpromazine, tetracylcines and isoniazid.

Stimulant laxatives

Stimulant laxatives stimulate the myenteric nerve plexus thereby causing rhythmic muscle

contractions and increasing intestinal motility. They also increase secretion of water into the bowel.

Their laxative effect is dose-dependent with inhibition of sodium and water absorption at low doses

and promotion of sodium and water inux into the colonic lumen at high doses. The most widely used

stimulant agents are senna and bisacodyl, which are approved for treatment of occasional constipation

and usually taken at bedtime. Onset of action typically occurs within 612 h but can be longer in older

patients. Stimulant laxatives have a less favourable adverse effect prole than other laxatives and can

cause cramping, abdominal pain, diarrhoea, electrolyte imbalance, and rarely, hepatotoxicity [53].

Chronic use can cause melanosis coli, a benign, brown-black pigmentation of the colonic mucosa which

is of no clinical signicance and is reversible with discontinued use [67]. The ACG task force concluded

that there is insufcient evidence to make a recommendation regarding the effectiveness of stimulant

laxatives in patients with chronic constipation [39]. Sodium picosulphate should be used with caution

in older patients, particlulary those with renal impairment or cardiac failure, because of the risk of

electrolyte disturbance [53].

Stool softeners and emollients

Stool softeners are ionic agents that moisten the stool through a detergent action. Available agents

are docusate sodium and docusate calcium, and though commonly used in hospitalized patients,

especially after childbirth or surgery, and in the management of haemorrhoids or anal ssure, there is

insufcient evidence to support their use in patients with chronic constipation [39]. Data suggest that

stool softeners may be inferior to psyllium in patients with chronic constipation [68]. Liquid parafn is

no longer recommended as it may cause anal seepage and irritation after prolonged use, reduced

absorption of fat-soluble vitamins, and lipoid pneumonia if aspirated [53].

P. Gallagher, D. OMahony / Best Practice & Research Clinical Gastroenterology 23 (2009) 875887 883

Chloride channel activators

Lubiprostone is bicyclic fatty acid that works by activatingtype-2 chloride channels on intestinal

epithelial cells thereby increasing uid secretion from the colon and enhancing stool passage [69]. It

has recently (2006) been approved for long-termtreatment of chronic constipation in adults, including

those aged 65 years. The most common adverse effects of lubiprostone are nausea and headaches

[69]. Patients should take lubiprostone with food to reduce the potential for nausea.

Other agents

Tegaserod has been removed from the market because of an associated increased risk of cardio-

vascular events. High-quality data supporting the use of prucalopride, loxiglumide, nizatidine,

colchicine, misoprostol and herbal supplements are not available for patients with chronic constipation

[39]. Therefore, these agents are not recommended for use.

Enemas and suppositories

Enemas play an important role in the management and prevention of faecal impaction among those

at risk [38]. Lubricant suppositories (glycerin) can help to initiate defaecation. In one study, adminis-

tration of daily lactulose with a glycerin suppository and a once-weekly tap water enema was shown to

be successful in achieving complete rectal emptying and preventing incontinence related to impaction

in institutionalized older patients [70]. Similar results were achieved with a combination of a laxative

and a suppository in patients with stroke [71]. However, sodium-phosphate enemas can cause

signicant electrolyte imbalance in vulnerable older patients e.g. those with renal impairment and

cardiac disease [72]. The antegrade continent enema involves placing a conduit into the appendix,

caecostomy or colon to permit regular instillation of enemas [73]. This approach is taken rarely in

patients with intractable slow transit constipation.

Biofeedback (pelvic oor retraining)

Biofeedback is used to treat anorectal dysfunction and is performed with anorectal electromyog-

raphy or a manometry catheter [74]. Patients receive visual and/or auditory feedback during simulated

evacuation of a balloon or silicon-lled articial stool and are trained to coordinate pelvic oor

relaxation with abdominal manoeuvres to facilitate defaecation. A recent meta-analysis of studies

comparing biofeedback to other treatments for defaecatory disorders suggested that biofeedback

conferred a six-fold increase in the odds of treatment success [74]. However, high-quality evidence of

its effectiveness in older adults is lacking and it is unsuitable for those with cognitive impairment.

Surgery

A subtotal colectomy and ileorectostomy should only be considered for older patients with severe

intractable constipation that is not due to anorectal dysfunction and in whom all conventional ther-

apies have failed. Potential complications after such surgery include small bowel obstruction, recurrent

constipation, diarrhoea and incontinence. Rectal surgery should be considered in those with func-

tionally signicant rectocoeles or signicant rectal prolapse in whom conservative measures have

failed.

Summary

Constipation is a signicant healthcare problem in older people. Secondary causes of constipation

are common and can usually be identied by careful clinical history and physical examination.

Constipating medications should be replaced with appropriate alternatives where possible. A regular

toileting schedule that takes advantage of the gastrocolic reex should be encouraged and older people

should have adequate privacy and time to toilet. Dietary bre should be increased where possible.

P. Gallagher, D. OMahony / Best Practice & Research Clinical Gastroenterology 23 (2009) 875887 884

Judicious use of laxatives is necessary in older people when general measures to treat constipation are

unsuccessful. Polyethylene glycol and lactulose are generally safe and well tolerated. Stimulant laxa-

tives and enemas should be for short-term use only. Preventative strategies are important for older

people at risk of faecal impaction. Specialized treatments such as biofeedback for defaecatory disorders

and surgery for those with severe slow transit constipation are rarely required in older people.

Conict of interest statement

None

Acknowledgements

No sources of funding were used to assist in the preparation of this manuscript. The authors have no

conicts of interest to declare.

References

[1] Connell AM, Hilton C, Irvine G, et al. Variation of bowel habit in two population samples. BMJ 1965;2:10959.

[2] Herz MJ, Kahan E, Zalevski S, et al. Constipation: a different entity for patient and doctors. Fam Pract 1996;13:1569.

*[3] Ashraf W, Park F, Lof J, et al. An examination of the reliability of reported stool frequency in the diagnosis of idiopathic

constipation. Am J Gastroenterol 1996;91:2632.

[4] Heaton KW, Radvan J, Cripps H, et al. Defecation frequency and timing, and stool form in the general population

a prospective study. Gut 1992;33:81824.

[5] Longstreth GF, Thompson WG, Chey WD, et al. Functional bowel disorders. Gastroenterology 2006;130:148091.

[6] Pare P, Ferrazzi S, Thompson WG, et al. An epidemiological survey of constipation in Canada: denitions, rates, demo-

graphics, and predictors of health care seeking. Am J Gastroenterol 2001;96:31307.

[7] Garrigues V, Galvez C, Ortiz V, et al. Prevalence of constipation: agreement among several criteria and evaluation of the

diagnostic accuracy of qualifying symptoms and self-reported denition in a population-based survey in Spain. Am J

Epidemiol 2004;159:5206.

[8] Talley NJ. Denitions, epidemiology, and impact of chronic constipation. Rev Gastroenterol Disord 2004;4:S310.

*[9] Higgins PD, Johanson JF. Epidemiology of constipation in North America: a systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol 2004;

99:7509.

[10] Johanson JF, Sonnenberg A, Koch TR. Clinical epidemiology of chronic constipation. J Clin Gastroenterol 1989;11:52536.

Practice points

Detailed clinical history, physical examination, rectal examination and medication revieware

usually sufcient to identify the cause of constipation in older patients.

Constipating medications should be replaced with appropriate alternatives where possible.

Dietary and lifestyle interventions have general health benets for older patients, but

evidence of their impact on constipation is lacking.

In most cases, a regular toileting schedule, a therapeutic trial of dietary bre, and simple

osmotic laxatives are effective.

Treatment with other laxatives in this age group is not supported by clinical trial evidence.

Faecal impaction should be prevented in those at risk.

Clinicians should be aware of the risks of long-term laxative and enema use in older people.

Research agenda

More older people with chronic constipation should be enrolled into clinical trials designed

to evaluate specic therapeutic interventions.

P. Gallagher, D. OMahony / Best Practice & Research Clinical Gastroenterology 23 (2009) 875887 885

[11] Talley NJ, Fleming KC, Evans JM, et al. Constipation in an elderly community: a study of prevalence and potential risk

factors. Am J Gastroenterol 1996;91:1925.

[12] Sonnenberg A, Kock TR. Epidemiology of constipation in the United States. Dis Colon Rectum 1989;32(1):18.

[13] Campbell AJ, Busby WJ, Horwath CC. Factors associated with constipation in a community based sample of people aged

70 years and over. J Epidemiol Community Health 1993;47:236.

[14] Philips C, Polakoff D, Maue SK, et al. Assessment of constipation in long termcare patients. J Am Dir Assoc 2001;2(4):149

54.

*[15] Monane M, Avorn J, Beers MH, et al. Anticholinergic drug use and bowel function in nursing home patients. Arch Intern

Med 1993;153:6338.

[16] Hosia-Randell H, Suominen M, Muurinene S, et al. Use of laxatives among older nursing home residents in Helsinki,

Finland. Drugs Aging 2007;24(2):14754.

[17] Robson KM, Kiely DK, Lembo T. Development of constipation in nursing home residents. Dis Colon Rectum 2000;43:940

3.

[18] OKeefe EA, Talley NJ, Zinsmeister AR, et al. Bowel disorders impair functional status and quality of life in the elderly:

a population-based study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 1995;50:M1849.

[19] McHugh SM, Diamant NE. Effect of age, gender and parity on anal canal pressures. Contribution of impaired anal

sphincter function to faecal incontinence. Dig Dis Sci 1987;21:72636.

[20] Bannister JJ, Abouzekry L, Read NW. Effect of ageing on anorectal function. Gut 1987;28:3537.

[21] Madsen JL. Effects of gender, age and body mass index on gastrointestinal transit times. Dig Dis Sci 1992;37:154853.

[22] Brogna A, Ferrara R, Bucceri AM, et al. Inuence of aging on gastrointestinal transit time. An ultrasonographic and

radiologic study. Invest Radiol 1999;34:3579.

[23] Loening-Baucke V, Anuras S. Sigmoidal and rectal motility in healthy elderly. J Am Geriatr Soc 1984;32:88791.

[24] Harari D, Gurwitz JH, Avorn J, et al. Bowel habit in relation to age and gender: ndings fromthe National Health Interview

Survey and clinical implications. Arch Intern Med 1996;156:31520.

[25] Mertz H, Naliboff B, Mayer E. Physiology of refractory constipation. Am J Gastroenterol 1999;94:60915.

[26] Stivland T, Camilleri M, Vassallo M, et al. Scintigraphic measurement of regional gut transit in idiopathic constipation.

Gastroenterology 1991;101:10715.

[27] Bannister JJ, Davison P, Timms JM, et al. Effect of stool size and consistency on defecation. Gut 1987;28:124650.

[28] Lanfranchi GA, Bazzocchi G, Brignola C, et al. Different patterns of intestinal transit time and anorectal motility in painful

and painless chronic constipation. Gut 1984;25:13527.

[29] Preston DM, Lennard-Jones JE. Severe chronic constipation of young women: idiopathic slow transit constipation. Gut

1986;27:418.

[30] Cummings JH, Bingham SA, Heaton KW, et al. Faecal weight, colon cancer risk, and dietary intake of non-starch poly-

saccharides (dietary ber). Gastroenterology 1992;103:17839.

[31] Herve S, Savoye G, Bahbahani A, et al. Results of 24-h manometric recording of colonic motor activity with endoluminal

instillation of bisacodyl in patients with severe chronic slow transit constipation. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2004;16:

397402.

[32] Sjolund K, Fasth S, Ekman R, et al. Neuropeptides in idiopathic chronic constipation (slow transit constipation). Neu-

rogastroenterol Motil 1997;9:14350.

[33] Bassotti G, Imbimbo BP, Betti C, et al. Impaired colonic motor response to eating in patients with slow-transit con-

stipation. Am J Gastroenterol 1992;87:5048.

[34] Rao SS, Welcher KD, Leistikow JS. Obstructive defecation: a failure of rectoanal coordination. Am J Gastroenterol 1998;93:

104250.

[35] Harewood GC, Coulie B, Camilleri M, et al. Descending perineum syndrome: audit of clinical and laboratory features and

outcome of pelvic oor retraining. Am J Gastroenterol 1999;94:12630.

[36] Read NW, Abouzekry L. Why do patients with faecal impaction have faecal incontinence? Gut 1986;27:2837.

[37] Culbert P, Gillett H, Ferguson A. Highly effective new oral therapy for faecal impaction. Br J Gen Pract 1998;48:1599600.

*[38] Wrenn K. Faecal impaction. N Engl J Med 1989;321:65862.

*[39] American College of Gastroenterology Chronic Constipation Task Force. An evidence-based approach to the management

of chronic constipation in North America. Am J Gastroenterol 2005;100:S14.

*[40] Locke III GR, Pemberton JH, Philips SE. American Gastroenterological Association medical position statement: guidelines

on constipation. Gastroenterology 2000;119(6):17616.

*[41] Rao SS, Ozturk R, Laine L. Clinical utility of diagnostic tests for constipation in adults: a systematic review. Am J Gas-

troenterol 2005;100:160515.

[42] ASGE guideline: guideline on the use of endoscopy in the management of constipation. Gastrointest Endosc 2005;26(2):

199201.

[43] Diamant NE, Kamm MA, Wald A, et al. AGA technical review on anorectal testing techniques. Gastroenterology 1999;116:

73560.

[44] Fletcher JG, Busse RF, Reiderer SJ, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of anatomic and dynamic defects of the pelvic oor

in defecatory disorders. Am J Gastroenterol 2003;98(2):399411.

[45] Metcalf AM, Philips SF, Zinsmeister AR, et al. Simplied assessment of segmental colonic transit. Gastroenterology 1987;

92(1):407.

[46] Gattuso JM, Kamm MA. Clinical features of idiopathic megarectum and idiopathic megacolon. Gut 1997;41:939.

[47] Lindeman RD, Romero LJ, Liang HC, et al. Do elderly persons need to be encouraged to drink more uids? J Gerontol A Biol

Sci Med Sci 2000;55(7):M3615.

[48] Meshkinpour H, Selod S, Movahedi H, et al. Effects of regular exercise in management of chronic idiopathic constipation.

Dig Dis Sci 1998;43:237983.

[49] Lewis SJ, Heaton KW. Stool form scale as a useful guide to intestinal transit time. Scand J Gastroenterol 1997;32(9):9204.

[50] Prescription cost analysis. England 2006 [online]. Available from URL: http://www.ic.nhs.uk/webles/publications/

pca2006/PCA_2006.pdf. [Accessed 2009 Apr 15.

P. Gallagher, D. OMahony / Best Practice & Research Clinical Gastroenterology 23 (2009) 875887 886

*[51] Jones MP, Talley NJ, Nuyts G, et al. Lack of objective evidence of efcacy of laxatives in chronic constipation. Dig Dis Sci

2002;47:222230.

[52] Voderholzer WA, Schatke W, Muhldorfer BE, et al. Clinical response to dietary ber treatment of chronic constipation. Am

J Gastroenterol 1997;92(1):958.

*[53] Xing JH, Soffer E. Adverse effects of laxatives. Dis Colon Rectum 2001;44:12019.

[54] Corazziari E, Badiali D, Bazzocchi G, et al. Long term efcacy, safety, and tolerability of low daily doses of isosmotic

polyethylene glycol electrolyte balanced solution (PMF-100) in the treatment of functional chronic constipation. Gut

2000;46:5226.

[55] Andorsky RI, Goldner F. Colonic lavage solution (polyehtylene glycol electrolyte lavage solution) as a treatment for

chronic constipation: a double blind, placebo-controlled study. Am J Gastroenterol 1990;85:2615.

[56] Cleveland MV, Flavin DP, Ruben RA, et al. New polyethylene glycol laxative for treatment of constipation in adults:

a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. South Med Assoc J 2001;94:47881.

[57] Corazziari E, Badiali D, Habib FI, et al. Small volume isosmotic polyethylene glycol electrolyte balanced solution (PMF-

100) in treatment of chronic nonorganic constipation. Dig Dis Sci 1996;41:163642.

[58] DiPalma JA, DeRidder PH, Orlando RC, et al. A randomised, placebo-controlled, multicenter study of the safety and

efcacy of a new polyethylene glycol laxative. Am J Gastroenterol 2000;95:44650.

[59] Freedman MD, Schwartz HJ, Roby R, et al. Tolerance and efcacy of polyethylene glycol 3350/electrolyte solution versus

lactulose in relieving opiate inducted constipation: a double-blind placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Pharmacol 1997;37:

9047.

[60] Chaussade S, Minic M. Comparison of efcacy and safety of two different polyethylene glycol-based laxatives in the

treatment of constipation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2003;17:16572.

[61] Dipalma JA, Cleveland MB, McGowan J, et al. A randomized, multicentre, placebo-controlled trial of polyethylene glycol

laxative for chronic treatment of chronic constipation. Am J Gastroenterol 2007;102(7):143641.

[62] Attar A, Lemann M, Ferguson A, et al. Comparison of a low dose polyethylene glycol electrolyte solution with lactulose for

treatment of chronic constipation. Gut 1999;44(2):22630.

[63] Marschall HU, Bartels F. Life-threatening complications of nasogastric administration of polyethylene glycol-electrolyte

solutions (Golytely) for bowel cleansing. Gastrointest Endosc 1998;47(5):40810.

[64] Sanders JF. Lactulose syrup assessed in a double blind study of elderly constipated patients. J Am Geriatr Soc 1978;26:

2369.

[65] Rouse M, Chapman N, Mahapatra M, et al. An open, randomised, parallel group study of lactulose versus ispaghula in the

treatment of chronic constipation in adults. Br J Clin Pract 1991;45:2830.

[66] Lederle FA, Busch DL, Mattox KM, et al. Cost-effective treatment of constipation in the elderly: a randomised double-

blind comparison of sorbitol and lactulose. Am J Med 1990;89:597601.

[67] van Gorkom BA, de Vries EG, Karrenbeld A, et al. Anthranoid laxatives and their potential carcinogenic effects. Aliment

Pharmacol Ther 1999;13:44352.

[68] McRorie JW, Dagy BP, Morel JG, et al. Psyllium is superior to docusate sodium for treatment of chronic constipation.

Aliment Pharmacol Ther 1998;12(5):4917.

[69] Johanson JF, Morton D, Geenen J, et al. Multicentre, 4-week, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of

lubiprostone, a locally acting type-2 chloride channel activator, in patients with chronic constipation. Am J Gastroenterol

2008;103(1):1707.

[70] Chassagne P, Jego A, Gloc P, et al. Does treatment of constipation improve faecal incontinence in institutionalized elderly

patients? Age Ageing 2000;29:15964.

[71] Harari D, Norton C, Lockwood L, et al. Treatment of constipation and faecal incontinence in stroke patients: randomized

controlled trial. Stroke 2004;35:254955.

[72] Mendoza J, Lejido J, Rubio S, et al. Systematic review: the adverse effects of sodium phosphate enemas. Aliment Phar-

macol Ther 2007;26:920.

[73] Lees NP, Hodson P, Hill J, et al. Long-term results of the antegrade continent enema procedure for constipation in adults.

Colorectal Dis 2004;6:3628.

[74] Koh CE, Young CJ, Young JM, et al. Systematic review of randomized controlled trials of the effectiveness of biofeedback

for pelvic oor dysfunction. Br J Surg 2008;95(9):107987.

P. Gallagher, D. OMahony / Best Practice & Research Clinical Gastroenterology 23 (2009) 875887 887

Reproducedwith permission of thecopyright owner. Further reproductionprohibited without permission.

Você também pode gostar

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (895)

- QLD Nursing EB10Documento74 páginasQLD Nursing EB10Levan LomidzeAinda não há avaliações

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5794)

- FLESH AND THE POWER IT HOLDS OFFICIAL by Death @ PDFDocumento19 páginasFLESH AND THE POWER IT HOLDS OFFICIAL by Death @ PDFLevan LomidzeAinda não há avaliações

- Flesh and The Power It Holds Official by DeathDocumento19 páginasFlesh and The Power It Holds Official by DeathLevan LomidzeAinda não há avaliações

- s14 - Combination Switch DiagramDocumento1 páginas14 - Combination Switch DiagramLevan LomidzeAinda não há avaliações

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- S15 - S13 ECU PinoutDocumento5 páginasS15 - S13 ECU PinoutLevan Lomidze100% (1)

- Care With Git PTDocumento16 páginasCare With Git PTHafidz Ma'rufAinda não há avaliações

- Hemorrhoids: Disclosure: No AffiliationDocumento13 páginasHemorrhoids: Disclosure: No AffiliationLhea Marie TrinidadAinda não há avaliações

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (400)

- LacerationsDocumento2 páginasLacerationsGoldyAinda não há avaliações

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- Colorectal Cancer Surgical OptionsDocumento52 páginasColorectal Cancer Surgical OptionsParish BudionoAinda não há avaliações

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- 060516how To Administer An EnemaDocumento3 páginas060516how To Administer An EnemaAmelia Arnis100% (1)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- BDS Medication Administration Curriculum Section V 2011 1Documento19 páginasBDS Medication Administration Curriculum Section V 2011 1TINJU123456Ainda não há avaliações

- User Manual Geratherm RapidDocumento1 páginaUser Manual Geratherm RapidDiana IleaAinda não há avaliações

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- Differential DiagnosisDocumento1 páginaDifferential Diagnosisririz b100% (1)

- VGO 411 Veterinary GynaecologyDocumento191 páginasVGO 411 Veterinary GynaecologyChandan PatilAinda não há avaliações

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (266)

- HEMORRHOID (Case Study)Documento45 páginasHEMORRHOID (Case Study)enny92% (24)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (345)

- Sample Nursing Care Plan For Patient With SchistosomiasisDocumento6 páginasSample Nursing Care Plan For Patient With SchistosomiasisAbigail Brillantes100% (2)

- The Prostate Is A Common Site of Carcinoma. It: Abdomen and PelvisDocumento62 páginasThe Prostate Is A Common Site of Carcinoma. It: Abdomen and PelvissrisakthiAinda não há avaliações

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2259)

- 2 Dr. Sareena GilvazDocumento39 páginas2 Dr. Sareena GilvazAiswarya ThomasAinda não há avaliações

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- Ozone TherapyDocumento24 páginasOzone TherapyDadoBabylobas100% (2)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- ENEMADocumento4 páginasENEMAangelaAinda não há avaliações

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- Anal Rectal DiseasesDocumento45 páginasAnal Rectal DiseasesAdhya TiaraAinda não há avaliações

- Hirschprung DiseaseDocumento61 páginasHirschprung DiseaseAdditi Satyal100% (1)

- LIPPNCOTT Vital Signs Height Weight Chapter 016Documento72 páginasLIPPNCOTT Vital Signs Height Weight Chapter 016Sara SabraAinda não há avaliações

- Constipation in ChildhoodDocumento10 páginasConstipation in Childhoodadkhiatul muslihatinAinda não há avaliações

- Case Presentation HemorrhoidDocumento20 páginasCase Presentation HemorrhoidawalrmdhnAinda não há avaliações

- Friedmacher2013Classification and Diagnostic Criteria of Hirschprung DiseaseDocumento18 páginasFriedmacher2013Classification and Diagnostic Criteria of Hirschprung DiseaseMelchizedek M. SantanderAinda não há avaliações

- Funda QuizDocumento7 páginasFunda QuizRea MontallaAinda não há avaliações

- ThemometerDocumento1 páginaThemometerapi-270688627Ainda não há avaliações

- Assessment of The Anus, Rectum and ProstateDocumento7 páginasAssessment of The Anus, Rectum and ProstateCristine SyAinda não há avaliações

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (121)

- Artigo Enema AyurvedaDocumento5 páginasArtigo Enema AyurvedaPauloAinda não há avaliações

- Digital Rectal Examination: Dr. Arley Sadra Telussa, SpuDocumento22 páginasDigital Rectal Examination: Dr. Arley Sadra Telussa, SpuDiana MarcusAinda não há avaliações

- Botox in Anal SpincterDocumento9 páginasBotox in Anal SpincteriwanbaongAinda não há avaliações

- Total Mesorectal Excision (Tme)Documento19 páginasTotal Mesorectal Excision (Tme)Mehtab JameelAinda não há avaliações

- Cancer Confidential Ebook Keith Scott MumbyDocumento23 páginasCancer Confidential Ebook Keith Scott MumbyAjnira Laurie Bloom100% (4)

- Abc Abuso 1 PDFDocumento6 páginasAbc Abuso 1 PDFMDMAinda não há avaliações