Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Construction Law - Demand Guarantees and The Fraud Defence.20140602.124611

Enviado por

motioncase560 notas0% acharam este documento útil (0 voto)

31 visualizações5 páginasGuardrisk issued Two construction guarantees (on demand guarantees) in favour of Kentz. Brokrew was obliged to secure "an irrevocable, on demand bank guarantee or a demand guarantee from a recognised financial institution" for proper performance. Brokrew experienced severe financial difficulties which impacted on its ability to perform its obligations under the construction contract.

Descrição original:

Título original

Construction Law - Demand Guarantees and the Fraud Defence.20140602.124611

Direitos autorais

© © All Rights Reserved

Formatos disponíveis

PDF, TXT ou leia online no Scribd

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoGuardrisk issued Two construction guarantees (on demand guarantees) in favour of Kentz. Brokrew was obliged to secure "an irrevocable, on demand bank guarantee or a demand guarantee from a recognised financial institution" for proper performance. Brokrew experienced severe financial difficulties which impacted on its ability to perform its obligations under the construction contract.

Direitos autorais:

© All Rights Reserved

Formatos disponíveis

Baixe no formato PDF, TXT ou leia online no Scribd

0 notas0% acharam este documento útil (0 voto)

31 visualizações5 páginasConstruction Law - Demand Guarantees and The Fraud Defence.20140602.124611

Enviado por

motioncase56Guardrisk issued Two construction guarantees (on demand guarantees) in favour of Kentz. Brokrew was obliged to secure "an irrevocable, on demand bank guarantee or a demand guarantee from a recognised financial institution" for proper performance. Brokrew experienced severe financial difficulties which impacted on its ability to perform its obligations under the construction contract.

Direitos autorais:

© All Rights Reserved

Formatos disponíveis

Baixe no formato PDF, TXT ou leia online no Scribd

Você está na página 1de 5

Construction Law - Demand Guarantees and the

Construction Law - Demand Guarantees and the Fraud Defence

Guardrisk Insurance Company Ltd v Kentz (Pty) Ltd

The law underlying the avoidance by a Guarantor of its obligations to make payment to a

beneficiary under a demand guarantee is clarified and reaffirmed by the most recent ruling by

the Supreme Court of Appeal in the case of Guardrisk Insurance Company Ltd vz Kentz (Pty)

Ltd.

Two construction guarantees (on demand guarantees) were issued by Guardrisk in favour of

Kentz, at the behest of Brokrew Industrial (Pty) Ltd (Brokrew) Kentz was one of the

contractors involved in the construction of a new power generation plant, the Medupi Power

Station, for Eskom.

During September 2008, Kentz entered into a construction contract with Brokrew relating to

the supply of ducting at Medupi. Brokrew was obliged to secure an irrevocable, on demand

bank guarantee or a demand guarantee from a recognised financial institution for proper

performance. This guarantee was referred to as the performance guarantee.

Kentz had paid Brokrew an amount of R17 million after an advance payment guarantee had

been issued by Guardrisk and submitted to Kentz to facilitate commencement of the works

by Brokrew, under the contract.

Brokrew experienced severe financial difficulties which impacted on its ability to perform its

obligations under the construction contract. By 31 January 2010, Brokrew's liabilities

exceeded its assets by more than R44 million. On 5 March 2010, Brokrew advised Kentz that

unless the terms of the contract were renegotiated, it would not be in a position to perform its

obligations in terms thereof.

On 24 February 2010 Kentz addressed a letter to Brokrew, confirming that Brokrew clearly

had the intention not to continue with performance of its obligations under the Contract, had

the intention to abandon the Contract and admitted to have become insolvent. In the

alternative, that Brokrew had, by its conduct, repudiated the contract which entitled Kentz to

accept same and cancel the Contract. Brokrew was placed on terms to perform its

obligations under the Contract. Later, on 9 March 2010, Kentz addressed a further letter to

Brokrew cancelling the Contract with immediate effect.

On 11 March 2010 Brokrew's attorneys addressed a letter to Kentz, in which it disputed

Kentz's entitlement to cancel the contract, recorded its contention that Kentz thereby

repudiated the contract and accepted Kentz's repudiation of the contract whereupon it

purported to cancel the contract. It also alleged that Kentz's call on the guarantees was

fraudulent given the latter's knowledge that it was not entitled to cancel the contract.

Prior to the hearing of the matter in the High Court, Brokrew was finally liquidated. The High

Court found that the evidence had failed to establish that Kentz, in making demand for

payment under the guarantees, had acted fraudulently. It further found that Guardrisk was

obliged to make payment in terms of the guarantees and accordingly granted judgment in

favour of Kentz.

The essential difference between the two types of bonds namely on demand or call bonds

on the one hand and conditional bonds on the other was described by Brand JA in Minister

of Transport and Public Works, Western Cape & another v Zanbuild Construction (Pty) Ltd &

another as follows:

[A] claimant under a conditional bond is required at least to allege and depending on

the terms of the bond sometimes also to establish liability on the part of the contractor for

the same amount. An "on demand" bond, also referred to as a "call bond", on the other hand,

requires no allegation of liability on the part of the contractor under the construction

contracts. All that is required for payment is a demand by the claimant, stated to be on the

basis of the event specified in the bond.

The Court found that the terms of the guarantees are clear and unambiguous. They create

an obligation on the part of Guardrisk to pay Kentz on the happening of a specified event. It

was recorded in the guarantees that, notwithstanding the reference in its wording to the

construction contract, the liability of Guardrisk as principal is absolute and unconditional, and

should not be construed to create an accessory or collateral obligation. The guarantees go

further and specifically state that Guardrisk may not delay payment in terms of the

guarantees by reason of a dispute between the contractor and the employer. The purpose of

the guarantees was to protect Kentz in the event that Brokrew could not perform its

obligations in terms of the construction contract.

In Lombard Insurance Co Ltd v Landmark Holdings (Pty) Ltd & others, the Court described a

guarantee very similar to the performance guarantee in this matter as:

not unlike irrevocable letters of credit issued by banks and used in international trade, the

essential feature of which is the establishment of a contractual obligation on the part of a

bank to pay the beneficiary (seller). This obligation is wholly independent of the underlying

contract of sale and assures the seller of payment of the purchase price before he or she

parts with the goods being sold. Whatever disputes may subsequently arise between buyer

and seller is of no moment insofar as the bank's obligation is concerned. The bank's liability

to the seller is to honour the credit. The bank undertakes to pay provided only that the

conditions specified in the credit are met.

The court found that the guarantees in this matter were unconditional and must be paid

according to their terms. It confirmed our legal position that the only basis upon which

Guardrisk can escape liability is to show proof of fraud on the part of Kentz.

Guardrisk also argued that each of the guarantees relied upon by Kentz requires that Kentz

state that the amount claimed was payable to it in terms of the contract and that the Brokrew

was in breach of its obligations under the contract. Guardrisk argued that the statements by

Kentz in each of its demands to Guardrisk, to the effect that the amount claimed was payable

to Kentz in terms of the construction contract with Brokrew, were material, knowingly false

and constituted a fraud on both Kentz and Brokrew.

The legal position regarding the fraud exception is that where a beneficiary who makes a call

on a guarantee does so with knowledge that it is not entitled to payment, our courts will step

in to protect a guarantor and decline enforcement of the guarantee in question. This fraud

exception only applies where:

the seller, for the purpose of drawing on the credit, fraudulently presents to the

confirming bank documents that contain, expressly or by implication, material representations

of fact that to his (the seller's) knowledge are untrue.

Furthermore, the party alleging and relying on such exception bears the onus of proving it.

That onus is to be discharged on a balance of probabilities, and will not lightly be inferred. In

the matter of Loomcraft Fabrics CC v Nedbank Ltd & another it was pointed out that in order

to succeed in respect of the fraud exception, a party had to prove that the beneficiary

presented the bills (documents) to the bank knowing that they contained material

misrepresentations of fact upon which the bank would rely and which they knew were untrue.

Mere error, misunderstanding or oversight, however unreasonable, would not amount to

fraud. Nor was it enough to show that the beneficiary's contentions were incorrect. A party

had to go further and show that the beneficiary knew it to be incorrect and that the contention

was advanced in bad faith.

The remarks made by Lord Denning MR in Edward Owen Engineering Ltd v Barclays Bank

International Ltd to the effect that performance guarantees are virtually promissory notes

payable on demand and very similar to letters of credit was relevant. In that case, Lord

Denning added:

A bank which gives a performance guarantee must honour that guarantee according to its

terms. It is not concerned in the least with the relations between the supplier and the

customer; nor with the question whether the supplier has performed his contracted obligation

or not; nor with the question whether the supplier is in default or not. The bank must pay

according to its guarantee, on demand if so stipulated, without proof or conditions. The only

exception is when there is a clear fraud of which the bank has notice.

Guardrisk contended that the demands under the guarantees were fraudulent as Kentz had

not given Brokrew adequate notice within which to remedy the breaches alleged by it. It was

argued that Kentz had terminated the Contract prematurely and unlawfully.

It was common cause that during March 2010, Brokrew had informed Kentz that unless the

terms of the building contract were renegotiated, it could not perform its obligations in terms

of the building contract. The Contract included a clause which states that the employer shall

be entitled to terminate the contract if Brokrew:

abandons the Works or otherwise plainly demonstrates the intention not to continue

performance of his obligations under the Contract . . . the Employer may, on notice to the

Contractor, terminate the contract immediately.

The Court found that Brokrew had clearly demonstrated its intention not to continue

performing its contractual obligations and Kentz was entitled to cancel the building contract

immediately, having reserved its rights in that regard previously.

The Court found that Guardrisk did not establish the fraud exception. In fact, what it sought to

do is to have this Court determine the rights and obligations of the parties in relation to the

construction agreement, which on the authorities, the Court was precluded from doing. The

finding by the High Court that the appellants had not discharged the onus resting on them to

establish fraud on the part of Kentz cannot be faulted. I agree with the reasoning of the high

court that:

The evidence before court clearly demonstrates that Kentz held the view that it was entitled

to lawfully pursue its claims under the guarantees. The mere fact that it pressed its claims

knowing that Brokrew held a contrary view about the cancellation with which it disagreed is

not fraudulent.

As already pointed out, a valid demand on an unconditional performance guarantee creates

an obligation on Guardrisk to make payment in accordance with the terms of the guarantee.

Mindful of that principle, the guarantor nevertheless urged the Court to have regard to the

decision of the majority in Dormell Properties 282 CC v Renasa Insurance Co Ltd & others

NNO. It was submitted that the principles of practicality enunciated by the majority in that

decision ought to be applied to the present matter and the issues concerning the rights and

obligations of the parties to the construction contract should be determined as all the parties

are before the Court and the disputes between Kentz and Brokrew have been crystallised

and are capable of determination.

Our Courts, in a long line of cases, have strictly applied the principle that a bank faced with a

valid demand in respect of a performance guarantee, is obliged to pay the beneficiary without

investigation of the contractual position between the beneficiary and the principal debtor. One

of the main reasons why Courts are ordinarily reluctant to entertain the underlying contractual

disputes between an employer and a contractor when faced with a demand based on an on

demand or unconditional performance guarantee, is because of the principle that to do so

would undermine the efficacy of such guarantees. The Supreme Court of Appeal in

Loomcraft referred to the fact that the autonomous nature of the obligation owed by the bank

to the beneficiary under a letter of credit has been stressed by courts both in South Africa

and overseas. The learned Judge referred to a number of authorities, both local and English

to illustrate this point. Similarly, the Supreme Court of Appeal in Lombard Insurance,

confirmed that the obligation on the part of the bank to make payment on a performance

guarantee is independent of the underlying contract and whatever disputes may arise

between the buyer and the seller are irrelevant as far as the bank's obligation is concerned.

This principle is based on sound reason. The very purpose of the guarantee is so that the

beneficiary can call up the guarantee without having to wait for the final determination of its

rights in terms of accessory obligations. To find otherwise, would involve an unjustified

paradigm shift and defeat the commercial purpose of performance guarantees.

For these reasons, the appeal was dismissed with costs.

Hendrik Markram B.(Eng) Civil; LLB

Director Markram Inc Attorneys

012 346 1278

083 675 3458

Você também pode gostar

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5794)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (344)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (399)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2259)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (120)

- 02 ChapDocumento41 páginas02 ChapTanner Womble100% (1)

- Chapter 22 Current LiabilitiesDocumento17 páginasChapter 22 Current Liabilitiesnoryn40% (5)

- FDIC v. Byrne, JR., 1st Cir. (1994)Documento19 páginasFDIC v. Byrne, JR., 1st Cir. (1994)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- Suzuki Schedules and StatementDocumento788 páginasSuzuki Schedules and StatementChapter 11 DocketsAinda não há avaliações

- Microinsurance - Executive Summary (English)Documento4 páginasMicroinsurance - Executive Summary (English)IPS Sri LankaAinda não há avaliações

- Canons of Trade Law Canonum de Ius ProventumDocumento198 páginasCanons of Trade Law Canonum de Ius Proventummragsilverman33% (3)

- Business Intelligence Framework For PharmaceuticalDocumento16 páginasBusiness Intelligence Framework For PharmaceuticalJaydeep Adhikari100% (13)

- Guaranty & Suretyship DigestsDocumento7 páginasGuaranty & Suretyship Digestsviva_33Ainda não há avaliações

- Case List SectransDocumento1 páginaCase List SectransMyla RodrigoAinda não há avaliações

- Actuary MagazineDocumento32 páginasActuary MagazineanuiscoolAinda não há avaliações

- A Strong Sales Contract Is Key To Your BusinessDocumento12 páginasA Strong Sales Contract Is Key To Your BusinessArnstein & Lehr LLPAinda não há avaliações

- Formation of ContractsDocumento6 páginasFormation of ContractsAdan Ceballos MiovichAinda não há avaliações

- 2019 Membership Info - GlobalDocumento14 páginas2019 Membership Info - GlobalhuihudsonAinda não há avaliações

- Phil - American Life Vs GramajeDocumento9 páginasPhil - American Life Vs GramajeMaricel Caranto FriasAinda não há avaliações

- LifeInsRetirementValuation M05 LifeValuation 181205Documento83 páginasLifeInsRetirementValuation M05 LifeValuation 181205Jeff JonesAinda não há avaliações

- Health Fnancing Mapping - Pusjak PDKDocumento9 páginasHealth Fnancing Mapping - Pusjak PDKRatu MartiningsihAinda não há avaliações

- Group 1 Crowd Fin InclusionDocumento48 páginasGroup 1 Crowd Fin InclusionSusu AlmondAinda não há avaliações

- QS To Broker - PT MAZO ARMADA PASIFIK (PUTRI HARBOUR)Documento3 páginasQS To Broker - PT MAZO ARMADA PASIFIK (PUTRI HARBOUR)AKHMAD SHOQI ALBIAinda não há avaliações

- Orange Book Handbook: Powers of AttorneyDocumento7 páginasOrange Book Handbook: Powers of AttorneycleincoloradoAinda não há avaliações

- Customer Expectation Through Marketing ResearchDocumento49 páginasCustomer Expectation Through Marketing ResearchMonal Deshmukh100% (2)

- ICICI BankDocumento3 páginasICICI BankRam LalAinda não há avaliações

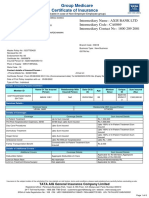

- Group Medicare Certificate of InsuranceDocumento8 páginasGroup Medicare Certificate of InsuranceArindam senAinda não há avaliações

- Vishal Cargo Movers & Packers: QuotationDocumento1 páginaVishal Cargo Movers & Packers: QuotationAnki PackersAinda não há avaliações

- IRDAI (Registration of Corporate Agents) Regulations 2015 PDFDocumento39 páginasIRDAI (Registration of Corporate Agents) Regulations 2015 PDFManju HassijaAinda não há avaliações

- HDFCLife SanchayPlus ProductBrochureDocumento16 páginasHDFCLife SanchayPlus ProductBrochurecrAzY cHandhUrUAinda não há avaliações

- Project On Investment Planning and FundraisingDocumento85 páginasProject On Investment Planning and FundraisingVikram Vrm0% (1)

- Broker/Shipper Transportation AgreementDocumento7 páginasBroker/Shipper Transportation AgreementgreencoffeeassociationAinda não há avaliações

- Income Tax Guide FY 2023-24Documento11 páginasIncome Tax Guide FY 2023-24akshay yadavAinda não há avaliações

- Group 5 - APM Project ReportDocumento20 páginasGroup 5 - APM Project ReportHema BhargaviAinda não há avaliações

- Theories of Regulation: Some Reflections On The: Statutory Supervision of Insurance Companies in Anglo-American CountriesDocumento22 páginasTheories of Regulation: Some Reflections On The: Statutory Supervision of Insurance Companies in Anglo-American CountriesreliaAinda não há avaliações