Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

The Book of Zambasta A Khotanese Poem On Buddhism (Review by Wayman)

Enviado por

TamehMTítulo original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

The Book of Zambasta A Khotanese Poem On Buddhism (Review by Wayman)

Enviado por

TamehMDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

The Book of Zambasta: A Khotanese Poem on Buddhism. by R. E.

Emmerick

Review by: Alex Wayman

The Journal of Asian Studies, Vol. 29, No. 1 (Nov., 1969), pp. 151-152

Published by: Association for Asian Studies

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2942534 .

Accessed: 12/08/2013 01:47

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

.

Association for Asian Studies is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The

Journal of Asian Studies.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 188.118.81.215 on Mon, 12 Aug 2013 01:47:11 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

BOOK REVIEWS 151

estimates for China in the I960's, project on

to that disjointed land the concepts of a closely

administered Western-type nation state for

which such aggregates would be meaningful.

For China, each time a nation-wide aggregate

is used, it needs to be asked how far it is, in

fact, meaningful. In some sectors a national

aggregate may be significant. In others-and

the reviewer would argue that national income

in the 1960's is among them-it is misleading

in that it gives rise to assumptions about an

integrated national economy that does not exist

except in certain sectors.

Some years ago a defector from the People's

Republic attended a conference on contempo-

rary China. Asked his opinion of the discus-

sion, he replied that it was like a blind man

feeling an elephant. However this was meant,

it could be taken as a compliment, since with

the developed sense of touch of the blind,

much could be known of the animal being

examined: certainly the fact that it was an

elephant. The techniques for the most part

used in the volume under review would chart

the changes in weight and volume of the crea-

ture, but fail to reveal if it was an elephant or

a rhinoceros.

AUDREY DONNITHORNE

The Australian National University

The Book of Zambasta: A Khotanese Poem

on Buddhism. EDITED AND TRANSLATED BY

R. E. EMMERICK. London: Oxford Uni-

versity Press, I968, XXii, 455 pp. Appen-

dixes, $20.75.

The

Book

of Zambasta (named after the

official Ysambasta who sponsored the work) is

the longest single poem to survive in the east

Iranian language called Khotanese. Of course,

Dr. Emmerick is indebted to previous labors

on this text, especially by E. Leumann and H.

W. Bailey, which he duly acknowledges. At

the same time, his edition and translation con-

stitutes a significant personal accomplishment

on a treacherous work. His admirable control

over the Khotanese language is shown by his

simultaneous

Saka

Grammatical Studies

(I968) which appeared as Volume XX in the

same London Oriental Series in which the pres-

ent work is Volume XXI.

Dr. Emmerick has avoided no pains to

collect every extant folio so that his text, which

is printed facing the English, will be as com-

plete as possible. Even so, there are frequent

gaps, often reducing the English version to a

string of phrases with intervening dots; and

only about half of the longest chapter (No.

XXIV) is extant. His critical apparatus is

principally devoted to the folio numbers (In-

troduction, pp. xi-xix) and variant fragments

(Appendix I, pp. 424-436) and so signaling

the folio numbers in the margins of the pub-

lished text. His metrical information is on the

separate page xxi as well as in Appendix 2

(pp.

437-453)

devoted to the Mailjusrinairdt-

mydvatdrasfitra. In each of the twenty-four

chapters, he numbers both the Khotanese

verses and their English renditions, so students

of the Khotanese language should find this to

be an ideal reader.

The fragmentary nature of the text accen-

tuates the translation difficulty. But the fact

that it is a Buddhist text seems almost inci-

dental to the treatment, since there are only

meager notes to the translation, namely those

contained in the valuable introductory para-

graph to each chapter, the Arapacana Syllabary

of Appendix 3 (pp. 454-455), and some rare

footnotes. There is no index at all, which if

constructed, would have facilitated consulta-

tion of the translation of the Buddhist work.

Still, Dr. Emmerick has succeeded in render-

ing a sufficient amount of the text with a high

level of translation to enable the reader to get

a fair idea of the contents of the work.

Although Dr. Emmerick's force of scholar-

ship was directed more to the text than to the

translation, the work should interest Buddhist

specialists. It sheds much light on the char-

acter of Khotanese Buddhism. It is significant

that this work is devoted to the mythological,

devotional, and miraculous side of Mahayana

Buddhism, with wholesale drawing on previ-

ous sources, especially from both the Ratnak-

iita and the Avatamsaka type of scriptures.

There is scarce evidence of philosophical sub-

tlety; rather the work is aimed at popularizing

Buddhism. The cult of the Future Buddha

Maitreya (Chapter XXIII, pp. 301-341) is pres-

ent as pure devotion and, incidentally, con-

tains a charming description of the jewels of

the Universal Emperor (pp. 3II-33). The

popular emphasis does not prevent the appear-

This content downloaded from 188.118.81.215 on Mon, 12 Aug 2013 01:47:11 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

152 JOURNAL OF ASIAN STUDIES

ance of some intriguing doctrinal points, such

as the manner of subdividing each of the six

perfections (pdran2itz) by the other perfec-

tions (pp.

I55, I57)

of the Bodhisattva. I sup-

pose that monks in the Khotan region would

still study more abstruse tresatises in the

authoritative Sanskrit language, just as cen-

turies later the Mongolian lamas would study

the sacred scriptures in the Tibetan language

rather than in their own Mongolian language

even when works were translated therein, as

the late Dilowa Gegen Hutukhtu once told

me.

The Sanskrit background of the work is not

lost to Dr. Emmerick, who again and again

renders the Khotanese by equivalent Sanskrit

terms rather than by English expressions. So

in Chapter X, p. 15: "He realizes the Suira-

rgamasamcdhdna and the

vairopama-experi-

ence, the ten upayas, the four vaisadradyas, the

eighteen dvenikadharmas. This is the un-

shared j[iana. So many are its dnus'amsas."

Such Sanskrit terms are useful for Buddhist

specialists, yet in their untranslated form they

give the impression that the translator never

intended his work to be read by persons

limited to the English language! In some cases,

this sticking to the Sanskrit term reduces the

clarity and even cogency of a sentence, as in

his use of the term samjiin as though this were

untranslatable (whereas, as the French Budd-

hologists long ago recognized, it means an

'idea' or a 'notion'), thus in Chapter IV, p. 8i:

"Therefore is there no manifestation of form

there: because one has had no meditation on

form. The vijildna has meditated without

samjini. It has not even the samriad of form."

Here the Khotanese (p. 8o) vifidni

kaste

asamini should mean "One has meditated with

perception (vijiidna) (but) not with an idea

(samnjfd)." And so also: "One has not even

the idea of form."

There are some other spots which are de-

batable, but there is no doubting the fine level

of attainment. The whole work appears to be

a kind of tour de force by a young scholar

whose promise is being proven, who should be

recognized as a solid specialist in Khotanese

studies. If in his haste to establish this point he

failed to equip his book with a full table of

contents and an index and thereby reduced

the usefulness, one should still give him credit

for the good accomplishment and look for-

ward to other works by him that are sure to

come.

ALEX WAYMAN

Columbia University

Survey of the Sino-Soviet Dispute. BY JOHN

GITTINGS. New York: Oxford University

Press, I968, XiX, 4IO

pp.

Appendixes, In-

dex. $I I.75.

The study under review is designed, as the

author suggests, to throw light on the origins

and development of the Chinese-Soviet dis-

pute by "extracting, refining and interpreting"

the articles and statements exchanged between

China and the Soviet Union between I963 and

I967. The polemics in I963 ceased to be

couched in "esoteric language" and both sides

began to indulge in an open dialogue about

their differences. The author has compiled a

careful and useful collection of annotated and

shortened versions of the documents, provid-

ing an indispensable reference book for those

who are concerned with the subject.

It may be argued that documents of this

nature are inadequate for an understanding

of the dispute between China and the Soviet

Union, and particularly so for this volume be-

cause after I963 the statements were often

"distorted and partial" in the open debate.

The materials appearing in this volume are

much more instructive and revealing than one

might have thought, because the language is

vivid and extreme about what we already

know, making it more interesting, but much

softer and less clear about issues that are still

obscure to us. For the most part, the extracts

reveal the sharply divergent views of China

and the Soviet Union on practically every ma-

jor issue, including the Vietnam War and the

Cultural Revolution. Each accuses the other of

making "a lie," "a distortion," or "an error."

On the other hand, both sides tend to be silent

on the I956-I957 period, especially on the na-

ture of their cooperation or discord over bloc

policy. The true circumstances of Chou En-

lai's trip to Warsaw early in I957, for example,

remain very unclear. Edgar Snow, for one,

suggests in The Other Side of the River that

Moscow shared its leadership with China in

bloc affairs because Khrushchev needed

China's backing to consolidate his power posi-

This content downloaded from 188.118.81.215 on Mon, 12 Aug 2013 01:47:11 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Você também pode gostar

- Mark Scheme (Final) January 2020Documento16 páginasMark Scheme (Final) January 2020aqib ameerAinda não há avaliações

- Fundamentals of Biochemical Engineering Dutta Solution ManualDocumento6 páginasFundamentals of Biochemical Engineering Dutta Solution Manualhimanshu18% (22)

- Jack Pumpkinhead of Oz - L. Frank BaumDocumento68 páginasJack Pumpkinhead of Oz - L. Frank BaumbobbyejayneAinda não há avaliações

- Did The Buddha Impart An Esoteric Teaching (Clearscan)Documento18 páginasDid The Buddha Impart An Esoteric Teaching (Clearscan)Guhyaprajñāmitra30% (1)

- John Irwin - The True Chronology of Aśokan PillarsDocumento20 páginasJohn Irwin - The True Chronology of Aśokan PillarsManas100% (1)

- BROWN, The Creation Myth of The Rig VedaDocumento15 páginasBROWN, The Creation Myth of The Rig VedaCarolyn Hardy100% (1)

- Eyewitness Bloody Sunday PDFDocumento2 páginasEyewitness Bloody Sunday PDFKatie0% (1)

- ENVSOCTY 1HA3 - Lecture 01 - Introduction & Course Overview - Skeletal NotesDocumento28 páginasENVSOCTY 1HA3 - Lecture 01 - Introduction & Course Overview - Skeletal NotesluxsunAinda não há avaliações

- Old Tibetan Studies: Dedicated To The Memory of R.E. EmmerickDocumento256 páginasOld Tibetan Studies: Dedicated To The Memory of R.E. Emmerickdvdpritzker100% (2)

- A Record of Buddhistic Kingdoms: Being an account by the Chinese monk Fa-hsien of travels in India and Ceylon (A.D. 399-414) in search of the Buddhist books of disciplineNo EverandA Record of Buddhistic Kingdoms: Being an account by the Chinese monk Fa-hsien of travels in India and Ceylon (A.D. 399-414) in search of the Buddhist books of disciplineAinda não há avaliações

- Tracing The Sources of The Book of Zambasta: The Case of The Yak A Painter Simile and The KāśyapaparivartaDocumento7 páginasTracing The Sources of The Book of Zambasta: The Case of The Yak A Painter Simile and The KāśyapaparivartasemstsamAinda não há avaliações

- GuodianDocumento34 páginasGuodianllywiwr100% (1)

- Victor H. Mair - Three Brief Essays Concerning Chinese TocharistanDocumento38 páginasVictor H. Mair - Three Brief Essays Concerning Chinese TocharistanTommaso CiminoAinda não há avaliações

- Paekche Yamato 016Documento13 páginasPaekche Yamato 016HeianYiAinda não há avaliações

- Leaving Footprints in the Taiga: Luck, Spirits and Ambivalence among the Siberian Orochen Reindeer Herders and HuntersNo EverandLeaving Footprints in the Taiga: Luck, Spirits and Ambivalence among the Siberian Orochen Reindeer Herders and HuntersAinda não há avaliações

- Imagining Harmony: Poetry, Empathy, and Community in Mid-Tokugawa Confucianism and NativismNo EverandImagining Harmony: Poetry, Empathy, and Community in Mid-Tokugawa Confucianism and NativismAinda não há avaliações

- Niti and Vairagya Satakas, Bhartrahari, 282p, Vedic Literature, English (1933)Documento283 páginasNiti and Vairagya Satakas, Bhartrahari, 282p, Vedic Literature, English (1933)pkmakAinda não há avaliações

- Princeton Library of Asian TranslationsNo EverandPrinceton Library of Asian TranslationsNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (67)

- Coomaraswamy A Yakshi Bust From BharhutDocumento4 páginasCoomaraswamy A Yakshi Bust From BharhutRoberto E. GarcíaAinda não há avaliações

- DR - Jan MeulenbeldDocumento7 páginasDR - Jan MeulenbeldManoj SankaranarayanaAinda não há avaliações

- The Origin of Himalayan StudiesDocumento13 páginasThe Origin of Himalayan StudiesRk TamangAinda não há avaliações

- White Bones Red Rot Black SnakesDocumento556 páginasWhite Bones Red Rot Black SnakessujatoAinda não há avaliações

- Creel, Herrlee Glessner - Studies in Early Chinese Culture, First Series (1938)Documento300 páginasCreel, Herrlee Glessner - Studies in Early Chinese Culture, First Series (1938)Victor BashkeevAinda não há avaliações

- Trirashmi Caves As Per GazetteerDocumento144 páginasTrirashmi Caves As Per GazetteerAtul BhosekarAinda não há avaliações

- The Broken World of Sacrifice - An Essay in Ancient Indian Ritual - Heesterman Reviewed - JamisonDocumento7 páginasThe Broken World of Sacrifice - An Essay in Ancient Indian Ritual - Heesterman Reviewed - Jamisonhonestwolfers100% (2)

- Yazdani Ajanta Plate Pt. 2Documento112 páginasYazdani Ajanta Plate Pt. 2Roberto E. García100% (2)

- Biography - Mahasi SayadawDocumento150 páginasBiography - Mahasi Sayadawtravelboots100% (1)

- Max Muller PaperDocumento13 páginasMax Muller PaperAashay PatelAinda não há avaliações

- AklujkarAshok The Early History Sanskrit Supreme LanguageDocumento33 páginasAklujkarAshok The Early History Sanskrit Supreme LanguageAshay NaikAinda não há avaliações

- Dependent Origination-Its Elaboration in Early Sarvastivadin Abhidharma Text - Collett CoxDocumento23 páginasDependent Origination-Its Elaboration in Early Sarvastivadin Abhidharma Text - Collett CoxDaisung Ildo HanAinda não há avaliações

- Article-How People MoveDocumento22 páginasArticle-How People MoveCik BedahAinda não há avaliações

- The Complete Poems of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow by Longfellow, Henry Wadsworth, 1807-1882Documento1.071 páginasThe Complete Poems of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow by Longfellow, Henry Wadsworth, 1807-1882Gutenberg.org100% (1)

- Paranavitana 1960 PDFDocumento28 páginasParanavitana 1960 PDFBhikkhu KesaraAinda não há avaliações

- The Mystique of Transmission: On an Early Chan History and Its ContextsNo EverandThe Mystique of Transmission: On an Early Chan History and Its ContextsAinda não há avaliações

- 'Beacons in The Dark': Painted Murals of Amitābha's Western Pure Land at Dunhuang.Documento39 páginas'Beacons in The Dark': Painted Murals of Amitābha's Western Pure Land at Dunhuang.Freddie MatthewsAinda não há avaliações

- Classic of History (Part 1 & 2: The Book of Thang & The Books of Yü)No EverandClassic of History (Part 1 & 2: The Book of Thang & The Books of Yü)Ainda não há avaliações

- ‘This Culture of Ours’: Intellectual Transitions in T’ang and Sung ChinaNo Everand‘This Culture of Ours’: Intellectual Transitions in T’ang and Sung ChinaAinda não há avaliações

- Michael Broido - The Jonangpas On Madhyamaka, A SketchDocumento7 páginasMichael Broido - The Jonangpas On Madhyamaka, A Sketchthewitness3Ainda não há avaliações

- Bagh Cave PaintingsDocumento14 páginasBagh Cave Paintingsayeeta5099Ainda não há avaliações

- Subjectivity in ʿAttār, Persian Sufism, and European MysticismNo EverandSubjectivity in ʿAttār, Persian Sufism, and European MysticismAinda não há avaliações

- Lorimer - 1951 - Stars and Constellations in Homer and HesiodDocumento17 páginasLorimer - 1951 - Stars and Constellations in Homer and HesiodmilosmouAinda não há avaliações

- 8771 0 JatakaDocumento27 páginas8771 0 JatakaVirgoMoreAinda não há avaliações

- The Song of the Nibelungs (Medieval Literature Classic): Epic Poem, Translated into Rhymed English Verse in the Metre of the OriginalNo EverandThe Song of the Nibelungs (Medieval Literature Classic): Epic Poem, Translated into Rhymed English Verse in the Metre of the OriginalAinda não há avaliações

- Ratna Karas AntiDocumento11 páginasRatna Karas AntiAnonymous hcACjq8Ainda não há avaliações

- Ancient History of Central Asia-Kushan Period PDFDocumento49 páginasAncient History of Central Asia-Kushan Period PDFplast_adesh100% (3)

- CharyapadaDocumento19 páginasCharyapadaMamun Rashid100% (1)

- A Sixth-Century Fragment of the Letters of Pliny the Younger A Study of Six Leaves of an Uncial Manuscript Preserved in the Pierpont Morgan Library New YorkNo EverandA Sixth-Century Fragment of the Letters of Pliny the Younger A Study of Six Leaves of an Uncial Manuscript Preserved in the Pierpont Morgan Library New YorkAinda não há avaliações

- Damon-Narrative and MimesisDocumento24 páginasDamon-Narrative and Mimesisjoan_paezAinda não há avaliações

- The Impact of Buddhism on Chinese Material CultureNo EverandThe Impact of Buddhism on Chinese Material CultureNota: 5 de 5 estrelas5/5 (1)

- Maps of Ancient Buddhist IndiaDocumento40 páginasMaps of Ancient Buddhist IndiaSameera Weerakoon100% (2)

- The Myth of Inanna and Bilulu (JNES 12, 1953) 160-188Documento34 páginasThe Myth of Inanna and Bilulu (JNES 12, 1953) 160-188nedflandersAinda não há avaliações

- Akbar Great Mogul 100 S Mitu of TDocumento554 páginasAkbar Great Mogul 100 S Mitu of TShikhin GargAinda não há avaliações

- Of Bliss: The Paradise of The Buddha of Measureless LightDocumento35 páginasOf Bliss: The Paradise of The Buddha of Measureless LightTodd Brown100% (2)

- Danish Kings and The Jomsvikings in The Greatest Saga of Óláfr TryggvasonDocumento105 páginasDanish Kings and The Jomsvikings in The Greatest Saga of Óláfr TryggvasonMihai SarbuAinda não há avaliações

- Stories Behind The SculpturesDocumento20 páginasStories Behind The SculpturesRahul GabdaAinda não há avaliações

- Stirrup As A Revoluntionary DeviceDocumento8 páginasStirrup As A Revoluntionary DevicejoeAinda não há avaliações

- Indian Kavya Poetry On The Far Side of The Himalayas - Translation, Transmission, Adaptation, Originality - Dan MartinDocumento53 páginasIndian Kavya Poetry On The Far Side of The Himalayas - Translation, Transmission, Adaptation, Originality - Dan Martinindology2Ainda não há avaliações

- (Greater India Series) Giuseppe Tucci-Travels of Tibetan Pilgrims in The Swat Valley-Greater India Society (1940)Documento91 páginas(Greater India Series) Giuseppe Tucci-Travels of Tibetan Pilgrims in The Swat Valley-Greater India Society (1940)nyomchen100% (1)

- Life of Brian Hugh Ton HodgsonDocumento206 páginasLife of Brian Hugh Ton HodgsonLuka MarcianoAinda não há avaliações

- Philosophy: Eastern versus Western Philosophy ExplainedNo EverandPhilosophy: Eastern versus Western Philosophy ExplainedNota: 5 de 5 estrelas5/5 (2)

- Writng Systems PDFDocumento10 páginasWritng Systems PDFTamehMAinda não há avaliações

- Daniels BrightDocumento5 páginasDaniels BrightLemon BarfAinda não há avaliações

- Miscellanea Iranica (Schwartz)Documento7 páginasMiscellanea Iranica (Schwartz)TamehMAinda não há avaliações

- Daniels BrightDocumento5 páginasDaniels BrightLemon BarfAinda não há avaliações

- Religious Diversity Among Sogdian Merchants (Grenet)Documento17 páginasReligious Diversity Among Sogdian Merchants (Grenet)TamehMAinda não há avaliações

- Essays On The Practice of Magic in Antiquity (Review by Miller)Documento3 páginasEssays On The Practice of Magic in Antiquity (Review by Miller)TamehMAinda não há avaliações

- Sanskrit Names of Drugs in Kuchean (Woolner)Documento17 páginasSanskrit Names of Drugs in Kuchean (Woolner)TamehMAinda não há avaliações

- A Khotanese Love Story (Review by Degener)Documento3 páginasA Khotanese Love Story (Review by Degener)TamehMAinda não há avaliações

- Apcr MCR 3Documento13 páginasApcr MCR 3metteoroAinda não há avaliações

- Radio Protection ChallengesDocumento31 páginasRadio Protection ChallengesJackssonAinda não há avaliações

- How To Effectively CommunicateDocumento44 páginasHow To Effectively CommunicatetaapAinda não há avaliações

- Comparative Analysis Betwee Fast Restaurats & Five Star Hotels RestaurantsDocumento54 páginasComparative Analysis Betwee Fast Restaurats & Five Star Hotels RestaurantsAman RajputAinda não há avaliações

- What Is ForexDocumento8 páginasWhat Is ForexnurzuriatyAinda não há avaliações

- Learn JQuery - Learn JQuery - Event Handlers Cheatsheet - CodecademyDocumento2 páginasLearn JQuery - Learn JQuery - Event Handlers Cheatsheet - Codecademyilias ahmedAinda não há avaliações

- Phonetic Sounds (Vowel Sounds and Consonant Sounds)Documento48 páginasPhonetic Sounds (Vowel Sounds and Consonant Sounds)Jayson Donor Zabala100% (1)

- Laser 1Documento22 páginasLaser 1Mantu KumarAinda não há avaliações

- How To Access Proquest: Off-CampusDocumento9 páginasHow To Access Proquest: Off-CampusZav D. NiroAinda não há avaliações

- Bunescu-Chilimciuc Rodica Perspective Teoretice Despre Identitatea Social Theoretic Perspectives On Social IdentityDocumento5 páginasBunescu-Chilimciuc Rodica Perspective Teoretice Despre Identitatea Social Theoretic Perspectives On Social Identityandreea popaAinda não há avaliações

- I. Title: "REPAINTING: Streetlight Caution Signs"Documento5 páginasI. Title: "REPAINTING: Streetlight Caution Signs"Ziegfred AlmonteAinda não há avaliações

- Modern State and Contemporaray Global GovernanceDocumento34 páginasModern State and Contemporaray Global GovernancePhoebe BuffayAinda não há avaliações

- Project Procurement Management: 1 WWW - Cahyo.web - Id IT Project Management, Third Edition Chapter 12Documento28 páginasProject Procurement Management: 1 WWW - Cahyo.web - Id IT Project Management, Third Edition Chapter 12cahyodAinda não há avaliações

- Basilio, Paul Adrian Ventura R-123 NOVEMBER 23, 2011Documento1 páginaBasilio, Paul Adrian Ventura R-123 NOVEMBER 23, 2011Sealtiel1020Ainda não há avaliações

- SOCI 223 Traditional Ghanaian Social Institutions: Session 1 - Overview of The CourseDocumento11 páginasSOCI 223 Traditional Ghanaian Social Institutions: Session 1 - Overview of The CourseMonicaAinda não há avaliações

- Africanas Journal Volume 3 No. 2Documento102 páginasAfricanas Journal Volume 3 No. 2Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary100% (2)

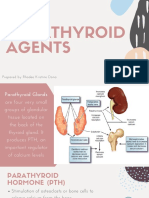

- Parathyroid Agents PDFDocumento32 páginasParathyroid Agents PDFRhodee Kristine DoñaAinda não há avaliações

- S.I.M. InnovaDocumento51 páginasS.I.M. InnovaPauline Karen ConcepcionAinda não há avaliações

- HotsDocumento74 páginasHotsgecko195Ainda não há avaliações

- Investigative Project Group 8Documento7 páginasInvestigative Project Group 8Riordan MoraldeAinda não há avaliações

- Assignment 1 TVM, Bonds StockDocumento2 páginasAssignment 1 TVM, Bonds StockMuhammad Ali SamarAinda não há avaliações

- GMAT2111 General Mathematics Long Quiz 2Documento2 páginasGMAT2111 General Mathematics Long Quiz 2Mike Danielle AdaureAinda não há avaliações

- Incremental Analysis 2Documento12 páginasIncremental Analysis 2enter_sas100% (1)

- Program PlanningDocumento24 páginasProgram Planningkylexian1Ainda não há avaliações

- Letters of ComplaintDocumento3 páginasLetters of ComplaintMercedes Jimenez RomanAinda não há avaliações