Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Young in Art

Enviado por

vasilikiserDireitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Young in Art

Enviado por

vasilikiserDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

a developmental look at child art

Young in Art

Craig Roland 1990, 2006

www.artjunction.org

Introduction

As a result of the child study movement in the early 1900s, it is generally recognized

that children progress through certain stages of development in their art making. Each

stage may be identified by certain characteristics that show up repeatedly in their artwork.

These stages have been linked to chronological age (particularly from 18 months to 6

years). However, a number of factors (both internal and external) affect a childs artistic

development. Thus, to expect that a particular child at a certain age should be at a certain

stage of development is inappropriate.

A number of theoretical models have been offered over the years to explain childrens

artistic development.While these models may vary (e.g., in the number of proposed

stages), they all propose a similar pattern of developmentone of progressing from scrib-

bling to realistic representation. Other generalizations that may be made include:

Socioeconomic factors seem to have little influence on the earliest stages. For

example, all children begin drawing by scribbling. Moreover, girls and boys tend to

draw alike at the early ages.

Childrens drawings typically show greater development than paintings because

crayons, markers, and pencils are easier to control than paint and a brush.

Considerable overlap exists between stages. Two stages may be represented in one

work and a child may regress to a previous stage before advancing to the next stage.

It is unlikely that a child will reach the later stages without adult support or

instruction. In other words, development in art is not universal and is dependent

on the environment in which a child grows up and is educated.

The following account suggests that there are four stages of childrens artistic develop-

ment: scribbling, pre-symbolism, symbolism, and realism. It is based on the popular view

that the desired end state of this progression is graphical realism. However, this should

not be taken to mean that the drawings that children typically do in earlier stages are

inferior or less desirable to those accomplished in later stages. On the contrary, some of

the more aesthetically pleasing works often are produced by children just beginning to

discover the joys of mark making.

1

Art Begins with Scribbling

All young children take great pleasure in moving a

crayon or pencil across a surface and leaving a mark.

This form of mark making or scribbling represents

childrens first self-initiated encounters with art.

Children typically begin scribbling around one-and-a-

half years of age. Most observers of child art believe

that children engage in scribbling not to draw a picture

of something; rather they do so for the pure enjoyment

of moving their arms and making marks on a surface.

Recently, however, a few researchers have challenged

this traditional view by showing that young children do

occasionally experiment with representation even

though their scribbles may not contain any recognizable

forms. This new perspective suggests that childrens

earliest mark-making activities may be more complex

than previously thought.

When children first start scribbling they usually

dont realize they can make the marks do what

they want. They often scribble in a random fash-

ion by swinging their arms back and forth across

the drawing surface (fig. 1 & 2). The lines they

make may actually go off the paper. They may

even look away from the page as they work.

But, it doesnt take long for children to recognize

the relationship between their movements and the

marks on the paper. As this discovery unfolds,

children begin to control their scribbles by vary-

ing their motions and by repeating certain lines

that give them particular pleasure. Longitudinal

marks in one or more directions may result.

Circular patterns and geometric shapes begin to

appear as childrens perceptual and motor abilities

increase (fig. 3). Lines are combined with shapes

to form various patterns and designs. Letter-

forms, especially those in the childs name, may

show up among the marks on the page (fig. 4).

Figure 1: Random scribble

Figure 2: Random Scribble

It is unfortunate that the very word " scribble" has

negative connotations for adults.

- Viktor Lowenfeld

2

As children gain control of the marks on the page,

they start to name their scribbles and engage in

imaginative play when drawing. A child may an-

nounce what he or she is going to draw before

beginning or may look at the marks on the page

afterwards and say, This is mommy. On another

day, the child may look at the same drawing and

say, This is my dog. To the adult, these drawings

may be neither recognizable nor remarkably dif-

ferent from early scribbles done by the child.Yet,

to the child making them, these seemingly

unreadable marks now have meaning.

Figure 3: Controlled scribble

Figure 4: Controlled scribble

The Teachers and Parents Role

For most youngsters, scribbling is intrinsically reward-

ing in itself, and thus no special motivation is needed.

Perhaps the best contribution that the teacher or parent

can make is to offer children the proper materials and

the encouragement to engage in scribbling.

In selecting appropriate art materials,it is important to

provide scribblers with a medium that enables them to

easily gain control of their marks. Tools such as crayons,

non-toxic markers, ballpoint pens, and pencils work

well.Watercolor paints, on the other hand, are difficult

for young children to control and should be avoided.

Tempera paint can be used provided it is a fairly thick

consistency so that it doesnt run down the page.

Color does not play a particularly important role in

scribbling. The colors offered should be few in number

and provide good contrast with the paper used. A dark

crayon, marker, or pencil is recommended along with

white or manila paper (12 by 18 inches).With tempera

paint, provide a large fairly absorbent sheet of paper

(18 by 24 inches) along with bristle brushes (one-half

inch in width). Children can work on the floor or any

other horizontal surface when scribbling.

Talking With Scribblers

When talking with the beginning scribbler, simply com-

ment on the childs movements when scribbling. For

instance, notice how fast the childs arm is moving or

how big the childs movements are. As the child gains

control of scribbling, comment on the variety of move-

ments and different marks the child has made. For

instance, notice the number of circles the child has

made or the nice lines going around the page.

As the child starts naming his or her scribbles, listen to

the childs comments and use the meanings offered by

the child as a source for dialogue. For instance, if the

child says, This is daddy, ask questions like Is your

daddy tall? Does he pick you up? Where do you go with

your daddy? If the child says, Im running, ask ques-

tions like Do you like to run on the playground? or

Where are you running? Encouraging the child to ver-

balize his or her thoughts, feelings and experiences

independently shows the child that you value what he

or she has done. This sort of thoughtful praise will help

children to be enthusiastic and imaginative in their

future art encounters.

3

Pre-Symbolism: The Figure

Emerges

Around three to four years of age, children begin

to combine the circle with one or more lines in order

to represent a human figure. These figures typically

start out looking like tadpoles (fig. 5) or head-

feet symbols (fig. 6). It is not uncommon for chil-

drens first representations of the figure to be highly

unrealistic or to be missing a neck, body, arms, fingers,

feet, or toes. Children may, in fact, draw two tadpole-

like forms to show their mother and father without

making visible distinctions between the two figures.

Several theories have been proposed to explain the tadpole phenomenon and

the reasons why young children tend to draw unrealistic or incomplete human

forms. Some experts suggest that children omit bodily features because of a lack

of knowledge about the different parts of the human body and how they are

organized. Others argue that children dont look at what they are drawing;

instead, they look at the abstract shapes already in their repertoire and discover

that these forms can be combined in various ways to symbolize objects in the

world. Still others believe that children are simply being selective and drawing

only those parts necessary to make their figures recognizable as human forms. It

is important for teachers and parents to consider, from a diagnostic standpoint,

that a child whom omits certain features when drawing a person may do so quite

unintentionally; and, thus, caution should be exercised when interpreting a

childs drawing as a reflection of personality or intellectual growth.

Figure 5: A family portrait consisting of several tadpole figures

Figure 6: Head-feet symbols

4

From an educational standpoint, teachers should also

consider that experiences designed to extend childrens

awareness of their own body parts often result in more

compete representations of the figures they draw. For

instance, children who depict figures without arms or

hands might be given the opportunity to play catch

with a ball and then to draw a picture of themselves

playing catch. Children will likely include arms and

hands in their drawings since these parts are required to

engage in this activity. Just asking children to draw such

an experience is usually not enough. They need to

become actively engaged in the activity being depicted

in order to develop a personal awareness of the details

involved.

Variations in the Figure

Children, four and five years of age, will experiment

with various ways of drawing the figure and may depict

the figure quite differently each time they draw.

Sometimes, they create figures quite unique to the per-

son or the experience being depicted. For instance, a

four year-old boy depicted a person walking in figure

7. Notice that the child has drawn this person with

greatly over exaggerated feet to symbolize walking. The

four year-old who drew the picture of her family

shown in figure 8 has added whiskers and long arms on

her daddy to express the feeling of being picked up

and hugged by her father. She has drawn her mother

with a body and legs, but no arms; and has shown her

brother and herself as two heads without bodies. Such

drawings tend to describe more how children of this

age think or feel about the things around them rather

than what they actually see when

they look.

If the continued omission of parts in a child' s drawing of

figures proves disturbing, stimulate his consciousness of the

omitted part through play and discussion.

- David Mendelowitz

Figure 7: Walking figure

Figure 8: A family portrait

There is considerable evidence to

suggest that children who draw fig-

ures without bodies, arms or legs

are certainly capable of identifying

these parts when asked to do so,

but the idea of creating a realistic

likeness of a person has not yet

occurred to them or occupied their

interest (Winner, 1982). Such a

concern doesnt typically show up

until the age of seven or eight.

5

Art and Self-image

The sensitive self-portrait shown in Figure 9 was drawn

by a four-and-a-half year old boy and is typical of the

kind of drawings done by children at this stage. The

head is drawn larger because of its importance to the

child (its where eating and talking goes on) and the

subject of the drawing is the child himself. Through the

act of drawing or painting, a child may explore several

self-possibilities before arriving at a satisfying self-

image. In this way, art plays a crucial role in the self-

defining process.

When planning for drawing and painting activities,

teachers should consider that four and five-year olds

tend to be egocentric in nature; and, thus, motivational

topics which enable these children to express

something about their emerging concepts of

self are particularly beneficial. Talking with the

children about their personal experiences such

as those associated with family, school, friends,

and pets will often provide ideal starting points

for their art encounters to begin. Topics that

include I or my help the child to identify

with the subject matter suggested. For instance,

appropriate drawing and painting themes for

children at this age include I am going to

school, My family and I am playing with

my friends.

The Young Childs Concept of Space

As young children become increasing aware of the

world around them, the many objects that make up

their environment will begin to appear in their draw-

ings. These objects are seldom drawn in relationship to

one another in position or size. Nor are they organized

on the page the way in which they are related spatially

in the world. Instead, objects will typically appear to

float on the page in the drawings and paintings done

by children of preschool age (fig. 10). This type of spa-

tial organization may appear to an adult as incorrect in

that it doesnt follow the Western tradition of repre-

senting three-dimensional space by the use of linear

perspective. Instead of considering this as a defect in

childrens artwork, one might appreciate their honesty

in arranging the forms on the page and their capacity

for creating balanced two-dimensional compositions

(Winner, 1982). Besides, if one looks at the artwork of

other cultures or that of many contemporary artists, it

can readily be seen that there is no right or wrong way

to portray space in a drawing (Lowenfeld, 1975).

At this age it is particularly important that any motivation or

any subject matter be related directly to the child himself.

- Viktor Lowenfeld

Figure 9: A self portrait

Figure 10: I am playing on the playground.

6

The Age of Symbolism

By the age of five or six, most children have devel-

oped a repertoire of graphic equivalents or symbols for

the things in their environment including a house, a

tree, a person, and so on. These symbols are highly

individualized since they result from childrens concep-

tual understanding rather than observation of the world

around them. For example, each childs symbol for a

person will be quite different from any other childs as

shown in Figures 11 and 12.

The symbols that children, five and six years old, draw

for a person usually have a clearly differentiated head

and trunk with arms and legs placed in the appropriate

locations. Details such as clothing, hands,

feet, fingers, nose, and teeth may also

receive the attention of individual chil-

dren. As previously mentioned, the omis-

sion of details in a childs drawing is no

cause for immediate concern. The child

may simply neglect to include a certain

feature due to its lack of importance in

the activity being drawn.

Once a child has established a definite symbol (or

schema) for a person, it will be repeated again and

again without much variation unless a particular expe-

rience causes the child to modify the concepts involved

(fig. 13). For instance, a child may exaggerate, change

or embellish certain parts of a person symbol in order

to reveal something unique or special about a particular

person or activity being depicted. Also, experiences

that stimulate childrens awareness of the various

actions and functions of the human figure will often

lead to changes in the way they symbolize a person and

to greater flexibility in their future depictions of peo-

ple. For instance, children at this age especially enjoy

and benefit from motivational topics involving sports

and story-telling activities.

When a normal child makes a connection between image

and idea, assigning meaning ot a drawn shape, the shape

becomes a symbol.

- Al Hurwitz & Michael Day

Figure 11: A family portrait

Figure 12: A family portrait

7

The Introduction of the Baseline

One of the more noticeable changes that occur in the

drawings of children around the age of five or six

involves the introduction of the baseline to organize

objects in space (Fig. 14). No longer do objects appear

to float all over the page as seen in childrens earlier

attempts at representation. Children are now aware of

relationships between the objects that they create and

they recognize that these objects have a definite place

on the ground.

Initially, children will line up people, houses and trees

along the bottom edge of the paper. They soon realize,

however, that a line drawn across the paper can serve as

a ground, a floor or any base upon which people and

objects rest. Later on, multiple baselines may be

drawn with objects lined up on each of them (fig. 15).

The inclusion of two or more baselines in a drawing

sometimes occurs when a child wishes to portray dis-

tance in his or her drawing. This graphic solution to

representing three-dimensional space can also be found

in adult art from many cultures and times.

As childrens understanding of the world becomes

more complex they feel the need to represent spatial

relationships more authentically. Accordingly, the base-

line eventually disappears in the drawings of older chil-

dren and the space below the baseline takes on the

meaning of a ground plane (fig. 21).

Figure 13: A figure schema

Figure 14: A typical baseline drawing

Figure 15: The use of two baselines to arrange things in space

8

Special Visual Effects

In addition to the invention of the base line, children

come up with a number of other ingenious ways to

depict space in their drawings. One of these involves

showing events that occur over time within one draw-

ing or a sequence of drawings (Fig.16). These space-

and-time representations, as they are called

(Lowenfeld, 1975), result from childrens growing con-

cern for telling stories and for showing action in their

artwork. Interest in creating visual narratives usually

starts around the age of five and then grows stronger as

children get older (Wilson & Wilson, 1982).

Another special type of drawing that children begin

making around the age of five or six is the X-ray

drawing in which an object appears transparent or has

a cutaway provided so that one can see inside (fig. 17).

Typically, this type of drawing is done whenever the

inside of something is of greater importance than the

outside. For instance, children will often use the X-ray

technique to show the inside of their houses, their

school, or their family car. Figure 18 shows an insightful

X-ray representation by a five-year-old boy of

his family and mother whom was pregnant at

the time. Note the inclusion of the umbilical

cord connecting the baby with its mother. This

is an excellent illustration of how children use

their active knowledge of a subject when

drawing a picture of it.

Figure 16: Michael Jordan in action

Figure 17: A look inside a mole hole

Figure 18: A family portrait showing an expectant mother

9

Childrens Art and Cultural Images

With all the visual materials available to American children today in the form of

photographs, book illustrations, comics, television, movies, video games, and web

sites, it seems only natural that they will borrow from these cultural sources in

creating their own artwork (Wilson & Wilson, 1982). Children as young as four

may include culturally-derived imagery in their drawings, but the influence of the

popular media is most noticeable among older children. Indeed, one will find a

number of aspiring comic-book artists in a typical fifth-grade classroom as well as

other children with a keen interest in drawing sports heroes, rock stars, fashion

figures, airplanes, space vehicles, and sports cars.

While many children simply copy their favorite super heroes and comic-book

characters, some also invent their own characters and narrative plots (fig. 19). In

doing so, these children frequently turn to television, movies and comic books

for their models. They draw figures that run, leap and fly across several frames;

zoom-in for a close-up of their heroine; and show perspective and dimensionality

in ways that children a generation ago couldnt do. Rather than discourage such

creative activity, teachers and parents should take full advantage of childrens fas-

cination with popular culture and use it to develop their drawing abilities beyond

the most basic level.

Figure 19: A nine-year old drew this action scene pitting several

Disney characters with creatures of his own invention

10

This new concern for making their pictures look right in terms

of detail and proportion leads to a crisis for many older children.

In trying to draw realistically, childrens efforts often fall short of

their expectations and they quickly become disappointed. Some

search for adult-like skills by copying illustrations in books and

magazines. More often, however, children become increasingly

critical of their graphic abilities and begin to show a reluctance to

engage in drawing activities as they grow older. Given the

increased emphasis on realism among children during their

preadolescent years, art instruction that focuses on visual

description and observational techniques can be particularly ben-

eficial at this age. Indeed, most children are quite capable of

attaining the realistic quality they so desire in their artwork (fig.

20). But, only if they receive the proper instruction that enables

them to develop the competencies required to do so.

The Crisis of Realism

By the age of nine or ten, many children exhibit

greater visual awareness of the things around them. As a

result, they become increasingly conscious of details

and proportion in what they are drawing. They typically

include body parts such as lips, fingernails, hairstyles,

and joints in their drawings of people. They also show

more interest than before in drawing people in action

poses and in costumes.

Figure 20: A portrait of a classmate by a twelve-year-old.

11

The Representation of Three-

Dimensional Space

While young children become engrossed in the

meanings and actions of subjects as they draw

them, older children tend to be more concern-

ed with whether their pictures resemble what it is they

are drawing. This interest in visual description typically

emerges around the age of eight or nine as children

begin to adopt their culture's conventions for represent-

ing a three-dimensional scene on a two-dimensional sur-

face (Winner, 1982). No longer are objects placed side

by side on a baseline as seen in younger children's draw-

ings. Now children attempt to arrange the things they

draw in relation to one another on the page with a

ground plane (fig. 21). In doing so, they begin to

show how the position of a viewer influences the image

drawn. They begin to draw objects that overlap one

another and that diminish in size. They also begin to use

diagonals to show perespective, or the recession of

planes in space (fig. 22).

Figure 22: Barnyard drawing by a twelve-year-old who used perspective, overlap,and

diminishing size to show depth

Figure 21: Backyard drawing by a ten-year-old using a ground plane

As children's readiness and interest in show-

ing depth in their pictures becomes appar-

ent, having them study the ways in which

various adult artists use overlap, diminishing

size and linear perspective within their

works might be helpful. But, children need

to understand that the use of these pictorial

devices is only one way of organizing space

and that many artists today have abandoned

such conventions in favor of developing

more personal and expressive ways of seeing

and making art.

The closer the child approaches adolescence, the more he

loses the strong subjective relationship to the world of

symbols.

- Viktor Lowenfeld

12

Older children are just beginning to discover the possibilities

of visual metaphor and that images can convey meanings

beyond the object depicted. In order to deepen this under-

standing and prevent children's concern for realism from

dampening their creative spirit, the teacher should introduce

themes that deal with the expression of certain emotions or

concepts through visual metaphor. For instance, children might

be asked to imagine themselves as an animal or an inanimate

object and to represent themselves as such in a drawing or

painting.

Visual Metaphor and Expressive Imagery

Many older children continue to draw and paint symbolically in

spite of the increased concern for realism in their artwork.

Indeed, children's emerging capacity for abstract thought

enables them to begin conceiving of images as visual

metaphors.When children draw or paint metaphorically, they

are using images to suggest an idea or emotion beyond the spe-

cific object depicted (fig. 23). For instance, older children are

able to recognize that a picture of an isolated tree suggests

loneliness and despair, or that a stag overlooking a range of

mountains suggests nobility. The ability to use images

metaphorically, depends on being able to entertain two levels

of symbolization at once. The artist must decide which object

best represents the concept or emotion and which lines,

shapes, and colors best represent the object (Smith, 1983).

Figure 23: A nine-year-old uses visual metaphor to

express certain feelings for his sister

13

Summary

When one charts the graphic development of children as they progress from pre-

school to the upper elementary school grades, at least four distinct stages or shifts can be

observed. First, children begin to scribble at about one or two years of age. Second, rep-

resentational shapes and figures emerge around the age of three or four. Third, children

develop and use graphic symbols for representing the things they encounter in their envi-

ronment. Lastly, around the age of nine or ten, children strive toward optical realism in

their drawings. It is important to note that these changes don't occur abruptly; rather,

they are often marked by small sub-stages or points in which children may exhibit charac-

teristics of two stages in one drawing.

Of course, what children seem to do naturally and what they are capable of doing are

entirely different matters. It is likely that teachers will find that students within their

classrooms are at varied points in their graphic development since some have had abun-

dant prior experiences with art, whereas others, may have had limited creative opportuni-

ties. Thus, teachers should avoid the temptation to place children at a particular stage sim-

ply because of their age or grade level.

Of greater concern to teachers and parents should be the lost of expressiveness and origi-

nality which seems to occur in children's drawings as they grow older. If one uses "real-

ism" as a criterion for judging the work of children, then they seem to improve with age

and experience. But, the drawings of upper-elementary school children typically appear

more conventional and rigid; and, therefore, less striking to the adult eye than those of

preschool children. Teachers and parents should also be concerned with the lost of interest

in drawing activities among students in the upper-elementary grades. Indeed, many older

children become so critical of their work that they simply stop drawing all together. How

might adults prevent such declines from occurring? While there are no easy answers to

this question, the following suggestions offer a few possibilities.

First, expose children in the upper elementary grades to various artists whom exhibit

both realistic and imaginative approaches to drawing. Encourage them to see that draw-

ings are not meant to be photographs and that the act of drawing enables them to show

their own special way of seeing the world.

Second, provide older children with opportunities to engage in both descriptive and

imaginative approaches to drawing. Show that you value the diversity of approaches and

the variety of ideas that children exhibit in their work.

Third, make the development of drawing abilities a priority in your classroom and home.

Provide children with opportunities to draw often and give them the assistance and the

encouragement they require.

14

Bibliography

Books

Hurwitz, A. & Day. M. (2007). Children and Their Art. New York: Hoarcourt Brace

Jovanvich.

Lowenfled,V. & Brittain,W. L. (1975). Creative and Mental Growth. New York: Macmillan.

Smith, N. (1983). Experience and Art:Teaching Children to Paint. New York: Teacher's College

Press.

Wilson, M. & Wilson, B. (1982). Teaching Children to Draw. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-

Hall.

Winner, E. (1982). Invented Worlds. Cambridge: Harvard University Press

Related Web Sites

Childhoods Past: Children's art of the twentieth century

www.nga.gov.au/Derham/default.htm

An exceptional on-line collection of children's artwork from the National Gallery of

Australia.

Defining Child Art

www.deakin.edu.au/education/visarts/child_art.htm

An essay on child art illustrated with Quicktime images.

Web Archive of Children's Art

childart.indstate.edu

An extensive database containing digitally copied artwork made by children, sponsored

by Indiana State University.

Drawing Development in Children Timeline

www.learningdesign.com/Portfolio/DrawDev/kiddrawing.html

An illustrated timeline of children's artistic development.

15

Você também pode gostar

- Email: You've Got (Too Much) Mail! 38 Do's and Don'ts to Tame Your InboxNo EverandEmail: You've Got (Too Much) Mail! 38 Do's and Don'ts to Tame Your InboxAinda não há avaliações

- Drawing Development in ChildrenDocumento2 páginasDrawing Development in Childrensixprinciples0% (1)

- Stages of Artistic DevelopmentDocumento14 páginasStages of Artistic Developmentapi-243035768Ainda não há avaliações

- Schematic StageDocumento3 páginasSchematic StageORUETU JOELAinda não há avaliações

- Stages of Art NotebookDocumento7 páginasStages of Art Notebookapi-216183591100% (1)

- Art 441 Lesson Plan 1 - Distorted Self-Portrait AssessmentsDocumento2 páginasArt 441 Lesson Plan 1 - Distorted Self-Portrait Assessmentsapi-259890775Ainda não há avaliações

- Art Curriculum OutcomesDocumento52 páginasArt Curriculum OutcomesMilena MilenkovicAinda não há avaliações

- Catching Them at It - Assessment in The Early Years PDFDocumento113 páginasCatching Them at It - Assessment in The Early Years PDFJessa Mae AndresAinda não há avaliações

- Lesson Plan: Step 1: Curriculum ConnectionsDocumento5 páginasLesson Plan: Step 1: Curriculum Connectionsapi-390378000100% (1)

- AEPS PsychometricPropertiesDocumento10 páginasAEPS PsychometricPropertiesLavinia GabrianAinda não há avaliações

- Art: The Basis of Education: Dedicated To Acharya Nandalal Bose and Acharya Binod Behari MukherjeeDocumento181 páginasArt: The Basis of Education: Dedicated To Acharya Nandalal Bose and Acharya Binod Behari Mukherjeeanto.a.fAinda não há avaliações

- Objectives Development Learning cc5Documento2 páginasObjectives Development Learning cc5api-282128005Ainda não há avaliações

- Mini Thematic Unit - Pre-KindergartenDocumento36 páginasMini Thematic Unit - Pre-Kindergartenapi-257946648Ainda não há avaliações

- Jars Snack Time Lesson PlanDocumento3 páginasJars Snack Time Lesson Planapi-316463966100% (1)

- Lesson Plan For Emergent Literacy Lesson-2 1Documento3 páginasLesson Plan For Emergent Literacy Lesson-2 1api-349028589Ainda não há avaliações

- Lesson Plan Educ390 BlambertsonDocumento5 páginasLesson Plan Educ390 Blambertsonapi-257409767Ainda não há avaliações

- No Prep Lesson Plans For Teachers & SLP's : The Grouchy LadybugDocumento12 páginasNo Prep Lesson Plans For Teachers & SLP's : The Grouchy LadybugVijay VenkatAinda não há avaliações

- PicturebookextensionDocumento2 páginasPicturebookextensionapi-555545246Ainda não há avaliações

- Pre Self Assessment Preschool Teaching PracticesDocumento4 páginasPre Self Assessment Preschool Teaching Practicesapi-497850938Ainda não há avaliações

- Lesson Plan What I Like About MeDocumento6 páginasLesson Plan What I Like About Meapi-307141452Ainda não há avaliações

- Pre-K Student Assessment ReportDocumento1 páginaPre-K Student Assessment ReportakwhatleyAinda não há avaliações

- Stone Soup Read Aloud Lesson PlanDocumento4 páginasStone Soup Read Aloud Lesson Planapi-346175167Ainda não há avaliações

- Leaflet DyslexiaDocumento12 páginasLeaflet DyslexiaTengku Azniza Raja ArifAinda não há avaliações

- Individual Investigation of A Learning Theory Aboriginal PedagogyDocumento12 páginasIndividual Investigation of A Learning Theory Aboriginal Pedagogyapi-249749598Ainda não há avaliações

- Psychology Science Assessing Creativity TestDocumento11 páginasPsychology Science Assessing Creativity TestSenthil KumarAinda não há avaliações

- Visual PerceptionDocumento1 páginaVisual Perceptionapi-81941124Ainda não há avaliações

- Nursery 2 - How We Express OurselvesDocumento3 páginasNursery 2 - How We Express Ourselvesapi-293410057Ainda não há avaliações

- If You Give A Moose A MuffinDocumento25 páginasIf You Give A Moose A Muffinapi-373177666Ainda não há avaliações

- Activity Planner 2 - 5 Year Old 1Documento4 páginasActivity Planner 2 - 5 Year Old 1api-451063936Ainda não há avaliações

- The Things We Are Day 2Documento4 páginasThe Things We Are Day 2api-361050686Ainda não há avaliações

- Lisa Mcguire Final Research Project Week 5Documento11 páginasLisa Mcguire Final Research Project Week 5Lisa McGuireAinda não há avaliações

- Concept and Principle of Child DevelopmentDocumento16 páginasConcept and Principle of Child Developmentmomu100% (1)

- Educational Effects of The Tools of The Mind CurriculumDocumento15 páginasEducational Effects of The Tools of The Mind Curriculummari.cottin2831Ainda não há avaliações

- Storytelling in EducationDocumento4 páginasStorytelling in EducationMel Rv Barricade100% (1)

- Art Research Paper - FinalDocumento6 páginasArt Research Paper - Finalapi-334868903Ainda não há avaliações

- Art Integration Lesson PlanDocumento6 páginasArt Integration Lesson Planapi-332854373Ainda não há avaliações

- Doodles: These Shapes Are Found in All The Letters of The Alphabet. Practising Them Will Help Your HandwritingDocumento3 páginasDoodles: These Shapes Are Found in All The Letters of The Alphabet. Practising Them Will Help Your HandwritingappleAinda não há avaliações

- David Crystal 2010 (Pp. 204-217)Documento14 páginasDavid Crystal 2010 (Pp. 204-217)Manuel JossiasAinda não há avaliações

- Curriculum NightDocumento5 páginasCurriculum Nightapi-567631728Ainda não há avaliações

- Weekly Lesson Plan Grade: Kindergarten Teacher: Mrs. Cartagena School: in The Middle of Nowhere Elementary School Dates: - Math Standards/ObjectivesDocumento2 páginasWeekly Lesson Plan Grade: Kindergarten Teacher: Mrs. Cartagena School: in The Middle of Nowhere Elementary School Dates: - Math Standards/Objectivesesmeralda0385Ainda não há avaliações

- Integrated Lesson HowardDocumento5 páginasIntegrated Lesson Howardapi-491154766Ainda não há avaliações

- Tiny Seed LessonDocumento7 páginasTiny Seed Lessonapi-350548244Ainda não há avaliações

- Literacy Lesson Plan FinalDocumento5 páginasLiteracy Lesson Plan Finalapi-355668742Ainda não há avaliações

- Practice Writing The Vocabulary WordsDocumento3 páginasPractice Writing The Vocabulary WordsLaura BocsaAinda não há avaliações

- History of DyslexiaDocumento14 páginasHistory of Dyslexiateacher sabirAinda não há avaliações

- Baierl Task Analysis and Chaining ProjectDocumento15 páginasBaierl Task Analysis and Chaining Projectapi-354321926Ainda não há avaliações

- The Stages: Object PermanenceDocumento2 páginasThe Stages: Object PermanencereghanAinda não há avaliações

- THEORY OF MIND - How To Work It Step by StepDocumento8 páginasTHEORY OF MIND - How To Work It Step by Step4gen_1Ainda não há avaliações

- Sorting Lesson PlanDocumento4 páginasSorting Lesson Planapi-267077176Ainda não há avaliações

- Read-Aloud Lesson 2Documento3 páginasRead-Aloud Lesson 2api-437989808Ainda não há avaliações

- AAC Technologies For Young Children PDFDocumento18 páginasAAC Technologies For Young Children PDFDayna DamianiAinda não há avaliações

- Ap Drawing SyllabusDocumento10 páginasAp Drawing Syllabusapi-260690009Ainda não há avaliações

- Playbased LearningDocumento12 páginasPlaybased Learningapi-285170086Ainda não há avaliações

- Developmental Stages of DrawingDocumento2 páginasDevelopmental Stages of Drawingapi-261703455Ainda não há avaliações

- Lesson Plan - Drawing Farm AnimalsDocumento2 páginasLesson Plan - Drawing Farm Animalsapi-272883536Ainda não há avaliações

- Erikson's Stages of DevelopmentDocumento17 páginasErikson's Stages of DevelopmentKhiem AmbidAinda não há avaliações

- Fiveness in KinderDocumento6 páginasFiveness in Kinderapi-286053236Ainda não há avaliações

- What Shall We Do Next?: A Creative Play and Story Guide for Parents, Grandparents and Carers of Preschool ChildrenNo EverandWhat Shall We Do Next?: A Creative Play and Story Guide for Parents, Grandparents and Carers of Preschool ChildrenAinda não há avaliações

- Images and Identity: Educating Citizenship through Visual ArtsNo EverandImages and Identity: Educating Citizenship through Visual ArtsRachel MasonAinda não há avaliações

- Ηλιας Βενεζης Το Νουμερο 31328Documento1 páginaΗλιας Βενεζης Το Νουμερο 31328vasilikiserAinda não há avaliações

- Overcoming agoraphobia: A self-help manualDocumento41 páginasOvercoming agoraphobia: A self-help manualvasilikiserAinda não há avaliações

- Carol of The Bells: Diminuendo CrescendoDocumento1 páginaCarol of The Bells: Diminuendo CrescendovasilikiserAinda não há avaliações

- Ultimate Guitar Chord ChartDocumento7 páginasUltimate Guitar Chord Chartanon-663427100% (71)

- Game of Thrones Easy Piano PDFDocumento3 páginasGame of Thrones Easy Piano PDFvasilikiserAinda não há avaliações

- Relationships InventoryDocumento13 páginasRelationships InventoryvasilikiserAinda não há avaliações

- FF3024 DL Scale Worksheets PDFDocumento20 páginasFF3024 DL Scale Worksheets PDFvasilikiserAinda não há avaliações

- Carol of The Bells PDFDocumento1 páginaCarol of The Bells PDFvasilikiserAinda não há avaliações

- Raven S IQ TestDocumento67 páginasRaven S IQ TestvasilikiserAinda não há avaliações

- Conflict Resolution Ορισμός 1Documento2 páginasConflict Resolution Ορισμός 1vasilikiserAinda não há avaliações

- StressDocumento11 páginasStressAnonymous KITquh5Ainda não há avaliações

- Overcoming Agoraphobia A Self Help M A N U A L: Karina Lovell (19 9 9)Documento39 páginasOvercoming Agoraphobia A Self Help M A N U A L: Karina Lovell (19 9 9)vasilikiserAinda não há avaliações

- The Psychoneuroimmunologic Impact of Indo-Tibetan Meditative and Yogic PracticesDocumento9 páginasThe Psychoneuroimmunologic Impact of Indo-Tibetan Meditative and Yogic PracticesvasilikiserAinda não há avaliações

- A Client's Guide To Schema TherapyDocumento13 páginasA Client's Guide To Schema Therapyvasilikiser100% (2)

- Test OCDDocumento7 páginasTest OCDvasilikiserAinda não há avaliações

- The Oxford Happiness QuestionnaireDocumento1 páginaThe Oxford Happiness QuestionnairevasilikiserAinda não há avaliações

- 4 Adult Children of AlcoholicsDocumento2 páginas4 Adult Children of Alcoholicsvasilikiser100% (4)

- Anger ManagementDocumento2 páginasAnger ManagementvasilikiserAinda não há avaliações

- Philippine Higher Education Landscape and ReformsDocumento41 páginasPhilippine Higher Education Landscape and Reformsjayric atayanAinda não há avaliações

- KUST faculty positionsDocumento2 páginasKUST faculty positionsmrsanaullahkhanAinda não há avaliações

- DLL CNFDocumento2 páginasDLL CNFMARIA VICTORIA VELASCOAinda não há avaliações

- The Professional Pricing Society (PPS) Brings Pricing Expertise To BerlinDocumento2 páginasThe Professional Pricing Society (PPS) Brings Pricing Expertise To BerlinMary Joy Dela MasaAinda não há avaliações

- Chris Peck CV Hard Copy VersionDocumento6 páginasChris Peck CV Hard Copy VersionChris PeckAinda não há avaliações

- Patterns Grade 1Documento4 páginasPatterns Grade 1kkgreubelAinda não há avaliações

- The Virtual Professor: A New Model in Higher Education: Randall Valentine, Ph.D. Robert Bennett, PH.DDocumento5 páginasThe Virtual Professor: A New Model in Higher Education: Randall Valentine, Ph.D. Robert Bennett, PH.DStephanie RiadyAinda não há avaliações

- Kodansha Kanji Usage GuideDocumento2 páginasKodansha Kanji Usage GuideJohn JillAinda não há avaliações

- Effects of part-time jobs on ACLC GAS 11 studentsDocumento8 páginasEffects of part-time jobs on ACLC GAS 11 studentsMercy Custodio BragaAinda não há avaliações

- Fea Tool Final ProductDocumento8 páginasFea Tool Final Productapi-463548515Ainda não há avaliações

- Bullying An Act Among of Peer Pressure AmongDocumento26 páginasBullying An Act Among of Peer Pressure Amongsuma deluxeAinda não há avaliações

- Providing Performance Feedback To Teachers: A Review: Mary Catherine Scheeler, Kathy L. Ruhl, & James K. McafeeDocumento12 páginasProviding Performance Feedback To Teachers: A Review: Mary Catherine Scheeler, Kathy L. Ruhl, & James K. Mcafeenatalia_rivas_fAinda não há avaliações

- HPSSSB Himachal Pradesh Recruitment 2012Documento8 páginasHPSSSB Himachal Pradesh Recruitment 2012govtjobsdaily100% (1)

- PH.D GuidelineDocumento97 páginasPH.D GuidelineBiswajit MansinghAinda não há avaliações

- Philippine Women's University OJT CourseDocumento4 páginasPhilippine Women's University OJT CourseVinz Navarroza EspinedaAinda não há avaliações

- Securing Children's Rights: Childreach International Strategy 2013-16Documento13 páginasSecuring Children's Rights: Childreach International Strategy 2013-16Childreach InternationalAinda não há avaliações

- Lesson 1 Plus Quick Training GuideDocumento14 páginasLesson 1 Plus Quick Training GuideMuhammad SirojammuniroAinda não há avaliações

- RP Assignment BriefDocumento3 páginasRP Assignment BriefishmeetvigAinda não há avaliações

- TLE Inset Training MatrixDocumento2 páginasTLE Inset Training MatrixJo Ann Katherine Valledor100% (2)

- Emergency Nurse OrientationDocumento3 páginasEmergency Nurse Orientationani mulyaniAinda não há avaliações

- Emcee Script For Closing ProgramDocumento3 páginasEmcee Script For Closing ProgramKRISTLE MAE FRANCISCOAinda não há avaliações

- Brittany Bowery Resume 2014Documento2 páginasBrittany Bowery Resume 2014api-250607203Ainda não há avaliações

- Study Skills BookletDocumento38 páginasStudy Skills BookletCybeleAinda não há avaliações

- NED University Master's in Supply Chain ManagementDocumento35 páginasNED University Master's in Supply Chain Managementshoaib2769504Ainda não há avaliações

- Ncert Books Free Downloads (PDF) For Upsc - Cbse Exam - Byju'sDocumento6 páginasNcert Books Free Downloads (PDF) For Upsc - Cbse Exam - Byju'sAbhinavkumar PatelAinda não há avaliações

- Near Jobless Growth in IndiaDocumento3 páginasNear Jobless Growth in IndiaRitesh KumarAinda não há avaliações

- Data Mining For Small Student Data Set - Knowledge Management System For Higher Education TeachersDocumento11 páginasData Mining For Small Student Data Set - Knowledge Management System For Higher Education TeachersRachel Torres AlegadoAinda não há avaliações

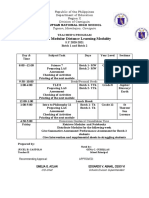

- Teachers Program Printed Modular Learning ModalityDocumento2 páginasTeachers Program Printed Modular Learning ModalityCastolo Bayucot JvjcAinda não há avaliações

- Senior PPG Q1-M3 For PrintingDocumento22 páginasSenior PPG Q1-M3 For PrintingChapz Pacz78% (9)

- WORKBOOK in ENG 6 - 2 PDFDocumento212 páginasWORKBOOK in ENG 6 - 2 PDFAnabelle Dasmarinas100% (2)