Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

An Investigation Into Whether The Finances of Premiershup Football Are Affecting The Competitiveness of The Sport

Enviado por

Sam Barnes0 notas0% acharam este documento útil (0 voto)

36 visualizações12 páginasExtended Project 2013, on the impact of the finances of premiership football on the competitiveness of the sport and the ethics behind this.

Título original

An Investigation into whether the finances of premiershup football are affecting the competitiveness of the sport

Direitos autorais

© © All Rights Reserved

Formatos disponíveis

DOCX, PDF, TXT ou leia online no Scribd

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoExtended Project 2013, on the impact of the finances of premiership football on the competitiveness of the sport and the ethics behind this.

Direitos autorais:

© All Rights Reserved

Formatos disponíveis

Baixe no formato DOCX, PDF, TXT ou leia online no Scribd

0 notas0% acharam este documento útil (0 voto)

36 visualizações12 páginasAn Investigation Into Whether The Finances of Premiershup Football Are Affecting The Competitiveness of The Sport

Enviado por

Sam BarnesExtended Project 2013, on the impact of the finances of premiership football on the competitiveness of the sport and the ethics behind this.

Direitos autorais:

© All Rights Reserved

Formatos disponíveis

Baixe no formato DOCX, PDF, TXT ou leia online no Scribd

Você está na página 1de 12

For richer or for poorer- Are the vast

finances of English football detrimental to

the game as a competition and are clubs

using their wealth in an ethical way?

An investigation into the effect of the financial wealth of football clubs in the

English game. This report will question how far the use of wealth by clubs is

fair and ethical and what effect this is having on the competitive element of

football, with a focus on the clubs of the English Premiership.

October 2011-March 2012

Sam Barnes- 8408

For richer or for poorer- Are the vast finances of Englishfootball detrimental to the

game as a competition and are clubs using their wealth in an ethical way?

An investigation into the effect of the financial wealth of football clubs in the English

game. This report will question how far the use of wealth by clubs is fair and ethical

and what effect this is having on the competitive element of football, with a focus on

the clubs of the English Premiership.

Introduction

Arguably, in England, football is unique. It is unique in the way that it dominates the sporting world, the

way it affects the lives of so many people and in the level of media coverage it receives. In the opinion of

many, football is glamorous and as the popular phrase goes, football is the beautiful game. For some of the

sports followers, the amounts of money involved in football are a reflection of the sports popularity and

importance. They suggest that there must be a good reason why the richest 20 football clubs in the world

have combined revenue of 3.9 billion

1

. However, not everyone agrees with this interpretation. To others,

the finances of football are crippling the game by destroying its competitive element and making the top

levels of the sport into the plaything of the rich; a game where success can be bought for the correct price.

Indeed, in a random opportunistic survey of 30 people, 20 agreed that the Premiership is becoming repetitive

with the same teams having the most success year after year. Whether this is as a direct result of the

Premierships finances remains to be seen, but it appears that the public believe that there is an issue. As

Campbell wrote in Dead Cert:

The widening wealth gap in the premiership is reducing Englands top league into an

increasingly unequal and uncompetitive struggle between small, rich elite clubs and others.

2

- Campbell, the Guardian, 2004.

To any fan of the sport, this is very worrying. In the opinion of most, the idea of football being reduced to a

financial competition is against the nature of sport. In addition, the same people argue that the wage bills

paid out by the largest clubs are morally wrong. They argue that the wages that are paid are unethical,

excessively large and that money could be put too much better use, possibly by distributing it amongst

football clubs in the local community.

The ethical framework that this report will use has two key approaches. These are the ones that best suit the

issue at hand, and are most applicable to this report. The first is the Utilitarian approach to ethics of J.

Bentham, who promoted the idea that an action should bring the greatest happiness possible to the greatest

number of people. The second is J.S Mills version of Utilitarianism, in which an ethical action is one that

protects the common good; this may link into the role of clubs in the community. Mill also maintains that

the quality of happiness is important- bringing intense happiness to few is better than bringing mild

happiness to many. The opinion of the public is that the finances of the game currently satisfy a small elite

number. Those who maintain this viewpoint claim that clubs are not doing enough to help the general

community, or the lower levels of football. According to the public, it therefore follows that Premiership

clubs are using their money in an unethical way.

This report will focus partly on the ethics of footballs finances and will investigate the problems outlined

above by answering the following question: How far is the use of money by Premiership clubs fair and

ethical? This will link into the other section of the report which will focus on the effect of football finances

on the competitive element of the sport, by investigating the question: Are the finances of football causing

results in the English Premiership to be more and more predictable, and if so, to what degree?

1

(Deloitte, 2009)

2

(Campbell, 2004)

1 The origin of todays football finances and the development of financial imbalance

To understand why the money in football may be an issue, an understanding of the origin of todays wealth

is necessary. In the early 1880s football became more popular and the income from entrance fees assisted

many football clubs in their attempts to be self-sufficient.

3

This newfound revenue culminated in a meeting

of the Football Association in 1885, which led to the approval of wage payment to players. In effect, football

had become professional sport.

4

Nevertheless, the Football Association (The FA) became displeased when

they discovered that some clubs were making a profit from this. Therefore, in 1912 the FA implemented a

rule that banned the payment of directors and limited the value of shares

5

. The idea behind this was to

maintain a fair balance between clubs by limiting the ability of the wealthier clubs to buy in the best players.

This is in stark contrast to the free market situation we have in place today.

The professional game continued to grow in popularity up until the First World War when the conscription

of players, managers, and ground staff stunted its expansion. After the war, the popularity of football

continued to increase, which led to a further rise in attendances.

6

Club directors took this opportunity to

increase ticket prices.

7

With larger industrialised cities such as Manchester and Liverpool having more

football supporters than ever before, a small financial divide began to appear between the clubs in these

large cities and clubs in other parts of the country.

Later in the century, televised football became more common and as the amount of football being shown on

television increased, members of the public became more interested in football and started to attend matches

themselves.

8

These people became regular spectators, and the increased attendances caused the financial

turnover of these clubs to increase.

9

As a result, the financial gap increased between the larger clubs shown

on the television, and the smaller clubs who were not.

10

However, at this time, there was no link between a

clubs finances and the success of the club.

11

Removal of the maximum wage

In 1957, a professional footballer by the

name of Jimmy Hill had begun a

campaign for the 20 maximum wage

limit to be removed.

12

At the time, 20

was near the average for a British

worker, but Hill believed that he and the

professionals deserved more. In 1961,

the FA finally succumbed to his

campaign and the maximum wage limit

was removed. Soon after, the salaries of

Hills fellow footballers increased

fivefold, but ironically, Hill himself did

not benefit as injury forced his early

retirement soon after the removal of the

maximum wage.

13

3

(Platts & Smith, 2010)

4

Ibid

5

Ibid

6

Ibid

7

Ibid

8

(King, 2002)

9

(Platts & Smith, 2010)

10

Ibid

11

Ibid

12

(White, 2004)

13

(White, 2004)

1961

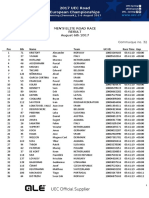

Fig. 1- The average salary of a top-flight footballer since 1961.

As figure one

14

shows, the average salary of a top-flight footballer in England has increased dramatically

over the last 5 decades. The bottom left of the graph represents 1961 and the removal of the maximum wage.

The graph continues through to 2010 by which time the average weekly wage has increased to nearly

36,000. This is a dramatic increase and many think that this has had a detrimental effect on the sport.

Sky Sports and televised football

Although this report does not deal with the direct effect of televised football, an understanding of the money

involved is vital as it allows the origin of the majority of the sports wealth to be seen. Indeed, most

premiership clubs make the majority of their turnover from broadcasting and media.

15

The broadcasting of football has developed over time, with the industry becoming increasingly larger

throughout. After occasional one-off broadcasts of football, the cult BBC highlights show Match of the

Day began in 1964, and it was one of the first programmes showing televised football on a regular basis.

16

In 1983, the sport was regularly broadcast live for the first time. The broadcasters only showed ten games

per season, and this cost the contract holders BBC and ITV a comparatively paltry 2.6 million per year for

the rights to show these games.

17

Three years later, British Satellite Broadcasting (BSkyB) was created in

1986 and this threatened the dominance of the two main terrestrial channels. This led to televised football

entering its second key stage. After high-stake negotiation s between opposing corporations, ITV secured a

four-year contract valued at an increased price of 0.61 million per match.

18

This contract ran for four years

up until 1992, when the amounts of money involved increased dramatically.

BBC and BSkyB eventually struck a deal, in which BSkyB would broadcast live matches via Sky Sports,

and the BBC would show highlights later on in the day. BSkyBs contract was for 60 matches a season,

each with a fee of 0.71 million, meaning that the contract had a total worth 42.8 million.

19

From this point

onwards and up until the present day, BSkyB has owned the vast majority of live premiership football. In

2009, BSkyB paid 1billion for four out of six packages of live premiership football, and with another

package already in their possession Sky Sports had the rights to 115 live games per year from 2010-2013.

Realistically, BSkyB monopolised live premiership football. This multi-million pound deal meant that

premiership clubs were now receiving more revenue from broadcasting than ever before. Sections two and

three will deal with how this money is used, and what impact this is having on the competitive side of

football.

2 Premiership clubs and the community- to what extent are clubs ethical in their use of wealth?

The combined turnover of the Premiership clubs totalled 2.1 billion in the season of 2010-11

20

. Despite this

large sum, many people feel that not enough of this money is reinvested back into the communities that

surround Premiership clubs. As a member of the public said:

To say that these clubs earn millions of pounds a year from match tickets which we the public

buy, why dont they do more for us?

- Comment of survey participant 23, 2012.

This is an opinion that appears to be a popular one among the public. Indeed, in a random, opportunistic

survey of 30 people, 28 believe that clubs should make more of an effort to share their wealth in the wider

community. In fact, the quote from survey participant 23 appears to be representative of the opinion of

14

Figure one is taken from (Intelligence, 2011)

15

(D.Conn, 2011)

16

(English football on television, 2011)

17

(Baimbridge, Cameron, & Dawson, 1996)

18

Ibid

19

Ibid

20

(D.Conn, 2011)

many. That is the idea that Premiership football clubs, with their turnovers reaching millions of pounds

21

, do

not do enough to help their surrounding community. One community football club replicates this view. In

particular, they feel too reliant on sponsorship from local businesses, and suggest that financial help from

Premiership clubs in the form of lump sums would be extremely useful.

However, the views from the public and the views of that community club do not triangulate well with other

sources. Representatives of Premiership clubs, articles in the media, and the Premier Leagues Creating

Chances report seem to suggest that Premiership clubs, and their players, do more for charity and the

community than the work of which the public are aware. An article in Third Sector, an independent website

issues affecting voluntary work, claims that every Premiership club now has a charitable foundation and one

or more charity that they work with. The article praises the work of clubs, and supports the argument that

Premiership clubs do more charitable work than the public recognises. As one corporate representative said:

Every (Premiership) club experiences the same things we do, in that their projects are not

given the coverage that they deserve. But thats not why we do it.

22

Simon Taylor, head of social responsibility at Chelsea, 2010.

In 2008, the Premier League set up the Premier League Professional Footballers Association community

fund. This empowers individual clubs to meet the needs of their local community in key areas such as

community cohesion, education and sport participation.

23

The initiative claims to have organised the

spending of 12.9 million over 3 years, and created 249 jobs along the way. This is impressive, so it is

interesting when contrasted against the results of the survey, in which the vast majority of participants are of

the opinion that football clubs do not do enough in the community.

One example of the work carried out by clubs is that done by Chelsea FC. In July 2010, they launched the

Chelsea Foundation, an independent charity that works in the community to bring sport to youngsters.

Chelsea also contributes to other charities; in 2011, Chelsea FCinvested1.5 million, and their social

responsibility investment was 5.6 million. When it is considered that in the season of 2010/11, Chelsea

had losses of 78 million, this is a substantial investment. There is a strong argument that the work of

Chelsea is very ethical- their work aims to help the common good by bringing communities together, and

because of their work, happiness is brought to those affected. Both of those are qualities of Utilitarian

actions and the use of football as a social tool triangulates with the thoughts of the Minster for Sport, who

said:

Football is the fabric of society, and goes deeper than what happens on the pitch...the

work of clubs brings communities closer together, and changes peoples lives for the

better

24

-Gerry Sutcliffe, Minster for Sport, 2009.

Clubs also do work to help charities that are not as well established. Birmingham City FC is notable in their

work which smaller, local causes. They work with Wasp Hills autism unit whose premises are adjacent to

their training ground.

25

This is a good example of a club working within the community and bringing

happiness to people, which again, is Utilitarian. In addition, more clubs than Birmingham and Chelsea that

work with charities; every single club in the Premiership has at least one programme of their own, aside

from any collaborative initiatives run by the Premier League itself.

26

When compared against the ethical

framework set out in the introduction, the clubs are being utilitarian- their actions are helping the common

good, and in doing so are bringing happiness.

21

(D.Conn, 2011)

22

(Willgoss, 2010)

23

(Premier League, 2008)

24

Ibid

25

Ibid

26

Ibid

However, critics claim that the investment behind these initiatives is insufficient when compared against the

turnovers of the clubs. Indeed, although the 5.6 million

27

spent by Chelsea on its social responsibility

investment may appear to be significant when shown as a proportion of losses, it only amounts to 2.6% of

the annual turnover.

28

Additionally, this investment of 5.6 million is only 3.2% of the wage bill that

Chelsea pays out per year.

29

Because of these figures, the argument triangulates well with both primary and

secondary data, which means that this argument has more weight. Additionally, what appeared to be very

utilitarian before now appears to be less ethical. Chelsea spends thirty one times as much on player wages,

than on helping the majority in the community. Only a minority is helped, so this is not in conjunction with

the philosophy of utilitarianism.

So far Chelsea has been singled out, but this pattern is maintained throughout the clubs of the premiership.

Although over three years the clubs spent 111.6 million on charitable events, this amounts to only 3% of

their combined turnover.

30

In stark contrast to this, in 2010/11 the teams of the Premiership spent on average

75.9% of their turnover on paying their wage bills.

31

In fact, Manchester City and Blackpool both spent

more money paying wages than they turned over that year. This supports the surveys findings, which

suggest that football clubs spend too much on their paying their players and not enough on supporting

charity work. This is far from utilitarian. In focussing on their players, they are helping the elite few as

opposed to the wider community.

Despite this, another part of J.S. Mills theory implies that paying the wages of players is actually ethical.

Once the players have been paid, they then go on to provide entertainment to thousands of fans a week. In

turn, this brings intense happiness to the supporters affected. J.S. Mills theory is that the quality of

happiness is paramount. As many supporters quote feelings of religious euphoria on match days,

32

it

follows that by paying apparently disproportionately large wages, the clubs of the Premiership are actually

ethical in their actions.

Although the financial figures appear to be rather damning of the charity work carried out, some say that the

work is sufficient. They argue that the quality, not the quantity of the community work is important. Again,

this is the ethical theory of J.S. Mill. Although the actual magnitude of the investment may not look too

impressive, the way that the money is used brings desirable results. This brings happiness to the community,

which in turn makes the work of the clubs ethical. Indeed, the focus of the work by Premier League clubs is

on those who need it most. One example of this is the Kickz programme, which is a joint enterprise of all the

clubs, and is the focus of the work by Premiership clubs:

The aim of the Kickz programme is to target some of the most disadvantaged areas

of the country in order to create safer, stronger, more respectful communities through

the development of young peoples potential

33

- Paul Cullen, Safety Co-ordinator, Manchester City Council

This is in accordance with the statistics on the subject. Seventy five per cent of the Kickz programme

focuses on the 30% most deprived communities, with an third of their work affecting the 5% most deprived

youngsters in the country.

34

In addition to providing sport, Kickz also holds Be safe weapon workshops.

According to Creating chances, this has caused a 50% fall in crime at certain Kickz projects. This supports

the view that the quality of the work is there, despite the investments being small in comparison to the wage

bills that are paid out. In addition, it follows that lower crime rates mean a happier community, so the

argument that clubs are using their wealth in a utilitarian way appears to be well supported. However, these

27

(Premier League, 2008)

28

(D.Conn, 2011)

29

Ibid

30

(Willgoss, 2010)

31

(Premier League Club Accounts, 2010)

32

(Baimbridge, Cameron, & Dawson, 1996)

33

(Premier League, 2008)

34

Ibid

statistics should be viewed critically. The Creating chances report was created by the Premier League, so

exaggerated and manipulated statistics are likely.

The above statistics appear, at first glance, to support the work of the Kickz programme in helping the most

deprived communities. However, to provide a balanced argument, the inverse of these statistics need

analysing. Creating chances claims that crime rates have fallen by 50% at some Kickz areas, which leaves

us open to try and interpret what is meant by some. It could well be the case that crime rate has not fallen

at all in many areas.

Despite this ambiguity, the work with Kickz and the other charities previously mentioned shows that clubs

appear to be making an effort to bring communities together. However, while the work of Kickz, Help a

London child and the numerous other charities have been effective in helping those desperately in need, the

work of clubs to help causes in less deprived areas appear to be limited. In the Creating chances report,

there was a definite focus on helping the disadvantaged, but little emphasis is put on supporting established

local football clubs. One such club is Southwell City FC, who despite having 32 teams for age groups

between under 7s and veterans, is still very reliant on sponsorship from local businesses. As one of the

managers said:

We rely far too much on the good nature of local businesses for our sponsorship. If they

decided they could no longer afford it, wed be in serious trouble

-Southwell City FC youth team manager, 2012.

The strong triangulation between this, the thoughts of other grassroots clubs, and the apparent lack of

funding for grassroots clubs in the creating chances report strongly suggests that clubs are focussing the

majority of their money on the disadvantaged. Ethically this is utilitarian, yet clubs in communities that are

not receiving the funding feel that they should be getting help. In addition, if grassroots clubs were to

receive funding, there would be widespread happiness. This would also be very ethical, and therefore the

lack of funding for grassroots clubs is a limitation of the work of Premiership clubs. Indeed, a method

through which grassroots clubs had access to financial backing from Premiership clubs would be ethical.

3 Are the finances of football, particularly wage bills, causing results to become increasingly

predictable?

Sport is a contest between opposing teams or players, a contest where the winner is decided by the skill,

determination and application of the participants. The appeal of football is that anything can happen. In any

match, a more skilful and organised team can be beaten by a less skilful team. This may be down to an

element of luck, an individual piece of brilliant skill or a poor decision by the officials.

35

In a survey, the

unpredictable nature is what the public like most about the sport. This triangulates well with a report by

Baimbridge et al., which found cup upsets and surprising results to be a large factor

36

in the attraction of the

public to football.

However, there is a fear that football is becoming increasingly predictable. With an increasing differential

between the turnovers of clubs, there is a fear that a correlation is appearing between the wage bills and

turnovers of those at the top of the league, and the wage bills and turnovers of those struggling at the bottom.

This had led to a growing trepidation among supporters that the Premier League is becoming more

predictable. They suggest that top quality players, united in one team, then go on to outclass the opposition

and win the league.

37

Effectively, this would make the league unbalanced, and consequently more

predictable. Therefore, because Baimbridge et al. proved that surprise results are a factor in the sports

support; this would suggest that the finances have been detrimental. This is supported by the Independent

European Sport Review, which said:

35

(Baimbridge, Cameron, & Dawson, 1996)

36

Ibid

37

(Campbell, 2004)

Fig. 2- Turnover vs. final league position (2010-11 Season)

There is currently a direct link between the financial budget of a club and its financial

wealth...rich clubs are currently too able to buy success -J.L. Arnaut, 2006.

This section will analyse the results of the 2010/11 season and determine whether the size of the turnovers

and the wage bills of each individual club had any bearing on their success at the end of the season.

The above graph focuses on the English premier league, and appears to show that the fear of many football

fans is becoming a reality. In this graph, the final league position is given a relative value, and the turnover

is given in millions.

38

The net turnover acts as a gauge of how much money is involved in the club as a

whole- this gives the best reflection of the relative wealth of a club. The relative finishing position acts as a

measure of success. By combining the turnovers and the relative finishing position, it could be seen if the

overall financial powers of a club were having an effect on their success, as Jose Luis Arnaut suggests.

The correlation, shown by the black trend line, suggests that the higher the turnover of a club the higher they

finish in the league- they are more successful. Therefore, lower turnovers result in less success. However,

there are the odd anomalies- West Ham United appeared to greatly underachieve, finishing bottom of the

league despite having the tenth highest turnover. In addition, West Bromwich Albion slightly overachieved,

ending the season mid-table regardless of their low turnover. However, the above graph strongly suggests

that there is a link between financial strength and success. Despite this, figure 2only demonstrates a

correlation- other factors may well have a part to play in the success of a team.

The Effect of a Clubs Wage Bill on their Success

39

Another factor that may have an effect on the success of a team is the clubs wage bill. This has risen

dramatically since the removal of the maximum wage limit in 1961, so much so that the current average

wage of a premiership footballer stands at 1,460,000 per year

40

. Allowing for the inflation of 1755%

41

since 1961, the monthly pay of a premiership footballer has increased by an equivalent of 20,000.

38

(Premier League Club Accounts, 2010)

39

Data for figure 2 came from (Premier League Club Accounts, 2010)

40

(Sawyer, 2010)

41

(This is Money, 2012)

0

50

100

150

200

250

300

350

400

450

A

r

s

e

n

a

l

M

a

n

c

h

e

s

t

e

r

U

t

d

C

h

e

l

s

e

a

L

i

v

e

r

p

o

o

l

M

a

n

c

h

e

s

t

e

r

C

i

t

y

T

o

t

t

e

n

h

a

m

A

s

t

o

n

V

i

l

l

a

E

v

e

r

t

o

n

F

u

l

h

a

m

W

e

s

t

H

a

m

U

n

i

t

e

d

S

u

n

d

e

r

l

a

n

d

B

o

l

t

o

n

W

a

n

d

e

r

e

r

s

W

o

l

v

e

s

S

t

o

k

e

C

i

t

y

B

l

a

c

k

b

u

r

n

R

o

v

e

r

s

B

i

r

m

i

n

g

h

a

m

c

i

t

y

N

e

w

c

a

s

t

l

e

U

t

d

W

i

g

a

n

A

t

h

l

e

t

i

c

W

e

s

t

B

r

o

m

i

c

h

A

l

b

i

o

n

B

l

a

c

k

p

o

o

l

T

e

a

m

Turnover m's

Relative final league

position

Linear (Relative final

league position)

Generally, the more skilful the footballer the more they are paid. To prove this point, a footballer playing in

League 2, the fourth tier of English football earns on average 65,000 per year.

42

In comparison to the salary

of a Premiership football, the gulf between the two wages is massive. The annual salaries of footballers in

the two leagues directly above League 2, the Championship and League 1, are 250,000 and 80,000

respectively.

43

This demonstrates that the higher the standard of football, the more a footballer is paid.

The general opinion of the public is that these high wages, which are reportedly in the most successful clubs,

are detrimental to the competitive element of the sport. The majority believe that clubs with larger wage bills

are more successful. Notably, even those who claimed to have very little knowledge of football seemed

confident in that idea. This argument is repeated in the Independent European Sport Review of 2006, which

states:

There is no doubt that football has been in financial crisis for many years now. This

financial crisis is directly linked to the massive wage inflation of recent years, which

can only be detrimental to the sport

- Jos Luis Arnaut, 2006.

44

This graph

45

was created in the same way as the one comparing turnover with the success of a team, but with

the annual wage bill replacing annual turnover. The black line of best fit demonstrates that a lower wage bill

causes a team to perform at a lower level, and more significantly the higher the wage bill of a club the better

that they perform. Again, there is an anomaly at West Ham United, which suggests that financial power does

not always mean success, and conversely West Bromwich Albion appear to have overachieved in relation to

their wage bill. Despite these anomalies, there is a clear pattern demonstrated in the graph. The significance

of this is that it supports the popular opinion that football is becoming increasingly predictable and less and

less competitive.

42

(Platts & Smith, 2010)

43

Ibid

44

(Arnaut, 2006)

45

Data for figure 3 was taken from (Premier League Club Accounts, 2010)

Fig. 3- Wage bill vs. League position (2010-11)

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

140

160

180

200

C

h

e

l

s

e

a

M

a

n

c

h

e

s

t

e

r

C

i

t

y

M

a

n

c

h

e

s

t

e

r

U

t

d

L

i

v

e

r

p

o

o

l

A

r

s

e

n

a

l

A

s

t

o

n

V

i

l

l

a

T

o

t

t

e

n

h

a

m

E

v

e

r

t

o

n

S

u

n

d

e

r

l

a

n

d

W

e

s

t

H

a

m

U

n

i

t

e

d

F

u

l

h

a

m

N

e

w

c

a

s

t

l

e

U

t

d

B

l

a

c

k

b

u

r

n

R

o

v

e

r

s

B

o

l

t

o

n

W

a

n

d

e

r

e

r

s

S

t

o

k

e

C

i

t

y

W

i

g

a

n

A

t

h

l

e

t

i

c

B

i

r

m

i

n

g

h

a

m

c

i

t

y

W

o

l

v

e

s

W

e

s

t

B

r

o

m

i

c

h

A

l

b

i

o

n

B

l

a

c

k

p

o

o

l

Wage bill m

Relative final league position

Linear (Relative final league

position)

0

50

100

150

200

250

300

350

400

450

C

h

e

l

s

e

a

M

a

n

c

h

e

s

t

e

r

C

i

t

y

M

a

n

c

h

e

s

t

e

r

U

t

d

L

i

v

e

r

p

o

o

l

A

r

s

e

n

a

l

A

s

t

o

n

V

i

l

l

a

T

o

t

t

e

n

h

a

m

E

v

e

r

t

o

n

S

u

n

d

e

r

l

a

n

d

W

e

s

t

H

a

m

U

n

i

t

e

d

F

u

l

h

a

m

N

e

w

c

a

s

t

l

e

U

t

d

B

l

a

c

k

b

u

r

n

R

o

v

e

r

s

B

o

l

t

o

n

W

a

n

d

e

r

e

r

s

S

t

o

k

e

C

i

t

y

W

i

g

a

n

A

t

h

l

e

t

i

c

B

i

r

m

i

n

g

h

a

m

c

i

t

y

W

o

l

v

e

s

W

e

s

t

B

r

o

m

i

c

h

A

l

b

i

o

n

B

l

a

c

k

p

o

o

l

Wage bill m

Turnover m

However, some may argue that the graph only provides data on one year of the Premiership, and that in

other years a team with less wealth may have been successful. A look at the results of years gone by

however shows that the above graph is no anomaly- in the 19 years of the premiership the winning team has

always been one of the five richest clubs in the league.

46

Manchester United has won the title 12 times,

Chelsea and Arsenal have both been champions 3 times, and Blackburn Rovers won their solitary title back

in 1995

47

. Blackburn won their title following the introduction of an extremely wealthy new chairman

named Jack Walker in 1991, who pumped millions of pounds into the club which at the time was

languishing low in the Second Division.

48

This data strongly triangulates with the view of the public, the vast majority of who believe that increased

wage bills result in better results. It also replicates the findings of the Independent European Sport review.

Consequently, the results of Figure 3 have a significant amount of weight.

Is there a correlation between wage bills and turnovers?

All the evidence in this section strongly suggests that increased financial power leads to increased success.

However, it could be the case that clubs with large turnovers have comparatively small wage bills and yet be

successful. This would imply that another factor, other than the payment of the best quality players, is the

cause of their success as a club. Therefore, that would suggest that the wage bill of a club is irrelevant-

instead of purchasing and paying high quality players, the money could be used in different ways.

Consequently, this would imply that there is no correlation between financial strength and success.

49

However, Figure 4 suggests that this is not the case. There is a good correlation between turnover and wage

bill. The only clubs who spent less than 65% of their turnover on wages are Arsenal with 29%, Fulham with

63%, Liverpool with 64%, Manchester United with 46% and Tottenham with 56%.

50

This means that 15 out

of the 20 premiership clubs spent 65% or more of their turnover paying wages. This triangulates strongly

with the findings of Figure 3, which suggested that a high wage bills means increased success. It follows that

clubs will be inclined to spend as much as they can afford on paying wages. This provides an explanation for

the findings of Figure 4.

46

(Platts & Smith, 2010)

47

(P.Edwards, 2012)

48

(BBC, 2000)

49

Data for figure 4 came from (Premier League Club Accounts, 2010)

50

(Premier League Club Accounts, 2010)

Fig. 4- Wage bill vs. Turnover (2010-11)

Conclusion

There is conflicting evidence, but the overall balance suggests that Premiership clubs are far more ethical in

their use of money than the public believe. Despite the lack of public awareness, clubs are doing a

substantial amount of community work. When the lack of secondary sources on the subject is considered, it

follows that a lack of media coverage is the reason for this. Although there is a strong argument that the

amounts of money involved are not large when compared against wage bills, the quality of community work

is high, with good success rates in creating jobs and bringing happiness. Therefore, the work is ethical.

Some may claim that the statistics in the Premier Leagues Creating Chances report may have been

manipulated to make the work look more successful than it actually is. However, after triangulating the data,

statistics in the Creating Chances report are shown to be reflected in the opinions of project participants.

The participants say that the work is very beneficial, and that the community is a happier place

51

as a

result. This means the statistics in Creating chances are reliable, and support the clubs community work.

In addition, the majority of charity work focuses on the disadvantaged. This reflects the findings of the

discussion group with Southwell City FC and also the findings of Creating Chances, in which work with

established grassroots clubs is not mentioned. However, under utilitarianism help is to be given to those who

need it most. In addition, Southwell City is only one club, so the value of the evidence is limited.

Despite being ethical in their use of money in the community, the wage bills that are paid out by Premiership

clubs have found to be unethical. Figures 2 and 3 both clearly show that the higher the turnover and the

higher the wage bill, the more successful a club is. Furthermore, these findings strongly triangulate with

public opinion, media articles, and reflect the findings of the Independent European Sport Review. This

means that the findings of figures 2 and 3 have significant weight. In addition, figure 4 disproves the

suggestion that a large turnover is independent of a large wage bill. The importance of this is that wage bills

are shown to be a factor in the success of a team- not only must a club have a large turnover, it also needs a

large wage bill in order to be successful.

However, is this actually detrimental to the game? The public think so- 80% think the Premiership is

becoming less interesting because the same teams keep on winning. When it is considered that Baimbridge

et al. found shock results to be a key attraction of fans to the sport, the negative effect is evident.

In summary, after assessing the above arguments, the balance of the evidence strongly suggests that the

finances of football are detrimental to the sport. The richest teams are much more likely to be more

successful, and according to the public and journal articles, this is deemed detrimental. In conjunction with

the ethical framework, this is also unethical and unfair. The competitive balance is disrupted, and the richest

clubs are winning more often, which is bringing less happiness to the public. A survey reflected this point;

the majority felt that the Premiership was becoming less interesting, and a larger majority felt that the money

was damaging the sport. As for charity work, the balance of the evidence suggests that the use of money is

ethical, but the public are generally unaware of this.

In short, the findings of this report are as follows:

1. There are positive correlations between both high turnovers and large wage bills with successful

performance. These correlations have been found to be detrimental to the publics perception of

football.

2. Premiership clubs do more charity work than the public believe, with the majority of this work

focussing on the disadvantaged. This has been found to be ethical under the ethical framework of

Utilitarianism, and a lack of media coverage means that the public undervalues and are unaware of

the charity work of clubs.

51

(Willgoss, 2010)

Bibliography

Arnaut, J. L. (2006). Independant European Sport Review.

Baimbridge, M., Cameron, S., & Dawson, P. (1996). Satellite television and the demand for football: A

whole new ball game? Oxford: Blackwell.

BBC. (2000, August 18). Jack Walker, Blackburn chairman dies. Retrieved January 8th, 2012, from BBC

SPORT: http://news.bbc.co.uk/sport1/hi/football/885534.stm

Campbell. (2004, November 7). 'Dead cert'. Retrieved October 20, 2011, from The Observer:

http://www.guardian.co.uk/football/2004/nov/07/newsstory.sport15?INTCMP=SRCH

D.Conn. (2011, May 19). In sickness and in wealth: A guide to the accounts of England's top clubs. The

Guardian .

Deloitte. (2009). The Football Money League. Sport Business Group.

Google documents (2010, July). Accounts spreadsheet. Retrieved October 15, 2011, from Google

documents:

https://docs.google.com/spreadsheet/ccc?key=0AonYZs4MzlZbdDRHR3Bmd2ZLb0JJUHBBOUNJcHJqN0

E&hl=en#gid=0

Intelligence, S. (2011). Average wages since 1961. Retrieved January 2012, 23, from Sporting intelligence:

http://www.sportingintelligence.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/01/Ave-wk-wage-since-61.jpg

King. (2002). The end of the terraces. Continuum International Publishing Group .

Maximum wage history. (2008, August). Retrieved November 13, 2011, from Wikipedia:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maximum_wage#History

P.Edwards. (2012, January). Premiership history. Retrieved January 8 2012 from Paul Edwards'

premiership football site: http://www.pedwards.co.uk/history.htm

Platts, C., & Smith, A. (2010). Money money money- The development of financial inequalities in English

professional football. London: Routledge.

Premier League (2010, August). League table 2010/11. Retrieved December 5th, 2011, from The Barclays

Premier League Offical: http://www.premierleague.com/en-gb/matchday/league-table.html?season=2010-

2011&month=DECEMBER&timelineView=played&toDate=1323014400000&tableView=CURRENT_ST

ANDINGS

Premier League (20, November 2011). PLFPA. Retrieved January 29, 2012, from Premier League:

http://www.premierleague.com/en-gb/creating-chances/2011-12/plpfa-community-fund.html

Premier League. (2008). Creating chances. London: The FA.

Sawyer, P. (2010, May). Premiership Footballers are the Poor Men of sport. Retrieved November 2011,

from The Telegraph: - http://www.telegraph.co.uk/sport/football/news/7530789/Premiership-stars-are-poor-

men-of-sport.html

This is Money. (2012). Inflation calculatorhttp://www.thisismoney.co.uk/money/bills/article-

1633409/Historic-inflation-calculator-value-money-changed-1900.html.

Wikipedia (2011, November 14th). English football on television. Retrieved November 30th, 2011, from

Wikipedia: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/English_football_on_television

Unknown. (2011, August). Premier League Club Accounts. Retrieved October 21, 2011, from Google Docs:

https://docs.google.com/spreadsheet/ccc?key=0AonYZs4MzlZbdDRHR3Bmd2ZLb0JJUHBBOUNJcHJqN0

E&hl=en#gid=0

White, J. (2004, January 7). Hill never benefited from a maximum wage. Retrieved November 14, 2011,

from Daily Telegraph: http://www.telegraph.co.uk/sport/columnists/jimwhite/2371348/The-Sporting-Week-

Hill-never-benefited-from-end-of-maximum-wage.html

Willgoss, G. (2010, August). How much do Premiership clubs give to charity? Retrieved January 27, 2012,

from Third Sector: http://www.thirdsector.co.uk/news/1022132

Você também pode gostar

- Resp QuotientDocumento6 páginasResp QuotientSam BarnesAinda não há avaliações

- Boast 10 - Compartment SyndromeDocumento1 páginaBoast 10 - Compartment SyndromeSam BarnesAinda não há avaliações

- Boast 2 - Spinal ClearanceDocumento1 páginaBoast 2 - Spinal ClearanceSam BarnesAinda não há avaliações

- Boast 1 - Fragility Hip Fractures PDFDocumento1 páginaBoast 1 - Fragility Hip Fractures PDFSam BarnesAinda não há avaliações

- MGD - Inhibiting Bacteria TranscriptionDocumento1 páginaMGD - Inhibiting Bacteria TranscriptionSam BarnesAinda não há avaliações

- Gate Control TheoryDocumento3 páginasGate Control TheorySam BarnesAinda não há avaliações

- Boast 8 - Traumatic Spinal Cord InjuryDocumento1 páginaBoast 8 - Traumatic Spinal Cord InjurySam BarnesAinda não há avaliações

- BMAT Section1-Past-Paper-2011 PDFDocumento32 páginasBMAT Section1-Past-Paper-2011 PDFKerry-Ann WilliamsAinda não há avaliações

- He Pat OlogyDocumento18 páginasHe Pat OlogySam BarnesAinda não há avaliações

- More Upper Neuro QuestionsDocumento1 páginaMore Upper Neuro QuestionsSam BarnesAinda não há avaliações

- Past Paper 2011 Section 3Documento4 páginasPast Paper 2011 Section 3hirajavaid246Ainda não há avaliações

- PPE RevisionDocumento2 páginasPPE RevisionSam BarnesAinda não há avaliações

- Bucs 2016 Full ResultsDocumento51 páginasBucs 2016 Full ResultsSam BarnesAinda não há avaliações

- Introduction To Liddle's Syndrome: Sam Barnes and Rusyai Zalynda RamliDocumento6 páginasIntroduction To Liddle's Syndrome: Sam Barnes and Rusyai Zalynda RamliSam BarnesAinda não há avaliações

- How To Write An Effective Personal StatementDocumento2 páginasHow To Write An Effective Personal StatementSam BarnesAinda não há avaliações

- BMAT Section 1Documento24 páginasBMAT Section 1JisunAinda não há avaliações

- Stacey's MomDocumento4 páginasStacey's MomSam BarnesAinda não há avaliações

- 99502-Tsa Oxford Section 1 2009Documento32 páginas99502-Tsa Oxford Section 1 2009Liviu NeaguAinda não há avaliações

- Baby Research AnalysisDocumento3 páginasBaby Research AnalysisSam BarnesAinda não há avaliações

- Calculating Entropy, Enthalpy Change and Solubilty Product of The Dissolution of Potassium BitartrateDocumento14 páginasCalculating Entropy, Enthalpy Change and Solubilty Product of The Dissolution of Potassium BitartrateSam BarnesAinda não há avaliações

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (400)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (266)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (344)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (121)

- The Hockey News Season Preview 2016-17Documento68 páginasThe Hockey News Season Preview 2016-17Aakash Banthia0% (1)

- IPL 2012 Full Schedule (Download Now) : DAY Date Match Time Team Team Venue WinnerDocumento6 páginasIPL 2012 Full Schedule (Download Now) : DAY Date Match Time Team Team Venue WinnerKewal RochwaniAinda não há avaliações

- Calendar of Events: Canada, Usa Head To 2003 Fifa Women'S World CupDocumento4 páginasCalendar of Events: Canada, Usa Head To 2003 Fifa Women'S World CupBlue LouAinda não há avaliações

- Atl DenDocumento11 páginasAtl DenCebadillaMantecona100% (1)

- Ronaldo InterviewDocumento2 páginasRonaldo InterviewAnastasia BurakevichAinda não há avaliações

- Mapendekezo Ya Majina Ya Watakaotunukiwa Vyeti Vya Maadhimisho Ya Miaka 50 Tanzania Kujiunga Na FifaDocumento7 páginasMapendekezo Ya Majina Ya Watakaotunukiwa Vyeti Vya Maadhimisho Ya Miaka 50 Tanzania Kujiunga Na FifaOthman MichuziAinda não há avaliações

- 2018 FIFA World Cup - WikipediaDocumento27 páginas2018 FIFA World Cup - WikipediacrampingpaulAinda não há avaliações

- RelatorioDocumento42 páginasRelatorioArthur PessanhaAinda não há avaliações

- Candidatxs Primarias PSUV 2015Documento32 páginasCandidatxs Primarias PSUV 2015Victor Hugo MajanoAinda não há avaliações

- Team Cologne: Modern Data Analysis and Scouting in The DFBDocumento4 páginasTeam Cologne: Modern Data Analysis and Scouting in The DFBapi-237441903Ainda não há avaliações

- Labour MPsDocumento57 páginasLabour MPsZoe Soy WalkerAinda não há avaliações

- World Cup 2011Documento3 páginasWorld Cup 2011mcasundeepAinda não há avaliações

- 4-3-3 GuardiolaDocumento4 páginas4-3-3 Guardiolaapi-8360539550% (2)

- Leadership Lessons From Jose MourinhoDocumento19 páginasLeadership Lessons From Jose MourinhoPallavi SharmaAinda não há avaliações

- Highest Rated Gold Right Midfielders FIFA 14 Career Mode Players - FUTWIZDocumento2 páginasHighest Rated Gold Right Midfielders FIFA 14 Career Mode Players - FUTWIZfelixsssAinda não há avaliações

- Concacaf News: Calendar of EventsDocumento4 páginasConcacaf News: Calendar of EventsBlue LouAinda não há avaliações

- Pavel Nedved BiographyDocumento4 páginasPavel Nedved BiographyRomadhon Al ZamyAinda não há avaliações

- Sat Q RooDocumento5 páginasSat Q RooPedro MentadoAinda não há avaliações

- Laws of Cricket (Urdu)Documento106 páginasLaws of Cricket (Urdu)Kashf51280% (25)

- Interactive Doha City MapDocumento1 páginaInteractive Doha City MapFairuzAinda não há avaliações

- Soka Magazine: March - April 2017Documento80 páginasSoka Magazine: March - April 2017Soka.co.keAinda não há avaliações

- Зонная оборона. Итальянский путь PDFDocumento119 páginasЗонная оборона. Итальянский путь PDFVolodymyr Nesterchuk100% (2)

- 29 10 KvoteDocumento2 páginas29 10 KvoteDjordje MitrovicAinda não há avaliações

- 11 Physical Education Keynotes Ch11Documento2 páginas11 Physical Education Keynotes Ch11subhamAinda não há avaliações

- Prince Ali Al Hussein Manifesto FIFA PRESIDENCYDocumento13 páginasPrince Ali Al Hussein Manifesto FIFA PRESIDENCYjadwongscribdAinda não há avaliações

- Clasificación Linea MEDocumento4 páginasClasificación Linea MEOwneatorAinda não há avaliações

- Wonderkid For Football Manager 2012...Documento9 páginasWonderkid For Football Manager 2012...bpromoteAinda não há avaliações

- Pariloto - Lista Meciuri 19.04.2011Documento1 páginaPariloto - Lista Meciuri 19.04.2011alex_ami_1Ainda não há avaliações

- International Match CalendarDocumento5 páginasInternational Match Calendartetei-5Ainda não há avaliações

- Jürgen Klopp - WikipediaDocumento28 páginasJürgen Klopp - Wikipedia01tttAinda não há avaliações