Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

C39796516enc 001

Enviado por

Madhu KumarDescrição original:

Título original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

C39796516enc 001

Enviado por

Madhu KumarDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

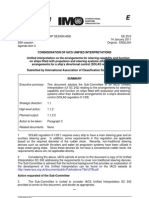

EUROPEAN

COMMISSION

DIRECTORATE-

GENERAL

TRANSPORT

TRANSPORT RESEARCH

APAS

MARI TI ME TRANSPORT

VII 38

Structure and organization

of maritime transport

Mercer Management Consulting Lloyd's Mari t i me

I nf ormat i on Services

The information contained in this publication does not necessarily reflect either the position or

the views of the European Commission

A great deal of additional information on the European Union is available on the Internet. It can be

accessed through the Europa server (http://europa.eu.int)

Cataloguing data can be found at the end of this publication

Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities, 1996

ISBN 92-827-7990-4

ECSC-EC-EAEC, Brussels Luxembourg, 1996

Printed in Belgium

Contents

it t u . . Mfft^TtmrnrriMff immirtrnirrTnrffiinTil'"''"' " " * -

Annexes:

Introduction

Flagging Out of EU-Owned Vessels

"Sub-Standard" or "High Risk" Vessels

Impact of Flagging Out and of High Risk Vessels on the EU Economy

Impact of Industry Structure, Corporate Strategies and Government Policy

Conclusions and Recommendations

Flag Definitions

Profile of Selected Open Registries

Profile of Selected EU Fleets

"One-Dimensional" Evidence of High Risk Vessels

Output from the Regression Model on High Risk Vessels

Estimation of EU Shipping Industry Turnover

EU Owned and Flagged Fleet Tables

Page

5-10

11-102

103-179

181-212

213-239

241-253

255-256

257-274

275-289

291-298

299-315

317-319

321-328

Introduction

Introduction: Objectives of the Study

The following objectives are at the basis of this study

DG VII wants to understand better:

- The different aspects of flagging out and its consequences

- The impact of "sub-standard vessels" on the EU maritime economy

- The organisation and structure of EU and non-EU shipping companies

Improved understanding of the competitive position of the EU fleet

What are the requirements for an attractive EU register?

What policy initiatives should DG VII pursue?

What research priorities need to be pursued under the 4th Framework Programme?

oo

Introduction: Project Activities

The Study Team completed an extensive series of analyses and investigations:

An in-depth analysis on the extent of flagging out by European owners

Research on cost factors involved in using Open Registries (direct market research and leverage of other DG

VII work undertaken by the Team)

Survey of 20 shipowners on flag selection criteria and actual flagging practices

Detailed statistical research into the correlation between Open Registries and various flag/vessel/owner

characteristics, on the basis of large vessel-specific databases and using sophisticated statistical modelling

approaches

Survey of definitions used for "substandard vessel" through expert interviews with key industry participants

Detailed modelling of the impact of crew cost and corporate tax on the EU maritime economy

In-depth review of major trends in the liner shipping industry

Introduction: Contents of the Report

This report provides details on a variety of analyses undertaken

Section A

Flagging Out

Section

Sub-standard Vessels, their

Deployment and Impact

Section C

Organisation and Structure of Liner

Shipping Sector and Companies

p

Quantify (lagging out

-Degree

-Correlation between

registers and ship

types/sizes

Assess (dis-)advantages

of non-EU flags

Determine flag selection

criteria of shipowners

1

Establish parameters for the

definition of "sub-standard

vessel"

- Detailed regression modelling

Assess correlation between

high-risk vessels and vessel

characteristics

Assess comparative EU

performance

Evaluate impact of high-risk

vessels on EU maritime

economy

Conclusion s and

Recommendations

Industry structure

Financial performance

Partnerships

EU competitive position

Key drivers of fleet growth

Cos! structures

CO

o

Executive Summary

Overall Conclusions

The degree of flagging out of EU owned vessels is significant and has accelerated over the last decade

EU owners have sought to take advantage of crew cost and corporate tax advantages under Open Registries

The financial performance of the shipping industry is poor, putting pressure on owners to seek cost savings

- Most major (liner) operators in Europe, Asia and North America have, or are planning to, flag(ged) vessels to

Open Registries

The average safety record of the EU owned fleet is certainly not better than the world average, and probably

worse

- In addition, there is significant variation around the mean, i.e., some EU owned fleets are certainly much

worse than the world average

In particular, there is evidence that the safety record of the EU owned fleet that has flagged out is worse than

that of the EU flagged fleet

Specific Conclusions and Recommendations

The Chapter on "Conclusions and Recommendations" (pages to ) is a self-contained chapter providing

details of the conclusions and specific recommendations

Flagging Out

of EU - Owned Vessels

lp> Quantification

(Dis) Advantages of Open Registries

ro

Flag Definitions

' - %* - >" " =- -

Administration

carried uut in an EU

state

or

Representation in an

EU parliament

EU Flags

Austria

Belgium

Denmark

France

- French Guiana

- Guadelope

- Martinique

- Reunion

Finland

Germany

Azores

Madeira

Canary Islands

Greece

Ireland

Italy

Luxembourg

Netherlands

Portugal

Spain

Sweden

UK

Second Register

Laws and Labour

codes apply as for

1st register

Flag of host nation

flown

No size or type

restrictions

DIS

GISO)

- ' . ; .

Affiliated Flags

EU state as a

signatory at the IMO

(May fly own or host

nation flag)

Faeroes, Greenland,

French Antarctic Terr.,

French Polynesia,

Kerguelen Is., Mayotte,

New Caledonia.Sl. Pierre,

Wallis and Futuna, Netherlands

Antilles, Macao, British Virgin

Is., Cayman Is., Channel Is., Isle

of Man, British Indian Ocean

Terr., Anguilla, Bermuda,

Falkland Is., Gibraltor, Hong

Kong, St. Helena,

Turks and Caicos, Monserrat,

Norwegian Antarctic Terr.

(1) noi split out from German Register due to lack of Information from GIS

Flagging Out: Definitions and Scope

The "Owned Fleet" consists of those vessels owned by European "parent owners" (termed "owner"), i.e.

"nationals" of one of the 15 member states of the EU

- The "parent owner" of a vessel is defined as the controlling interest behind that vessel

The "Registered Flagged Fleet" consists of those vessels registered under the relevant state flags, regardless

of the nationality of the parent owner (short: Flagged Fleet)

The analysis comprises all seaborne cargo vessels (the Merchant fleet) over 100 gt and consists of six

categories:

- Liquid bulk - General cargo

- Dry bulk - Ro/Ro

- Container - Other dry cargo

The affiliated countries are defined as countries with an EU state as a signatory at the IMO

0)

EU Owned Fleets 15 Countries

Number of Vessels Million of dwt

16000 400

Other Flags

Affiliated Flag

International Secondary

Registers (DIS)

EU Flags

300

C

O

200

100

Other Flags

Affiliated Flags

International Secondary

Registers (DIS)

EU Flags

1985 1994 1985 1994

Note: GIS Is not split out from the German Register in the Lloyds Database and hence is not shown separately

Source: LMIS database, Team analysis

Flag

Q EU & second Registers

Other Flags

Flagging Out: EU Owned Fleets

1985

12464

232

1994

11426 vessels

259 million dwt

While total tonnage under EU ownership has increased over the last decade, the degree of flagging out has also increased

substantially

The vessel count under EU ownership has decreased by 8% (1,039 units) between 1985 and 1994, but the

aggregate tonnage has increased by 12% (27 million dwt)

- EU owned fleet:

- As a result, the average size of the EU owned vessel has increased from 18,600 dwt to 22,600 dwt. This

contrasts with the average size of a vessel in the world fleet increasing from 16,200 dwt to 17,200 dwt

only

The EU-owned vessels flagged out are larger than the EU flagged ones (27,500 dwt vs. 18,500 dwt)

The flag composition of the EU fleet has changed dramatically

- EU owners registered nearly 47% of vessels in 1994 under non-EU flags (ie. 'other flags') vs. only 28%

in 1985

- In tonnage terms 56% of EU owned tonnage was registered under non-EU flags in 1994 vs. 38% in 1985

0)

This compares to "world fleet flagging out":

1985

12%

31%

1994

19% by vessel numbers

45% by dwt tonnage

Note: (1) Vessels registered under Open Registries, as defined by the ITF

Oi

CD

EU and Affiliated Flagged Fleets

Percentage Change 1985 1994

Vessel Numbers

EU Flags

Affiliated Flags

1985

8,936

798

1994

6068

793

Total

Total

9,734 6,861

DWT (millions)

EU Flags

Affiliated Flags

1985

149

15

1994

104

26

DWT (millions)

EU Flags

Affiliated Flags

Total

164 130

Vessel Numbers

40

EU Flags _

3

2/

c

Affiliated Flags

Total 30%

30%

20

21%

20 40 60 80

1 %

73%

Note: See annex "EU Owned and Flagged Fleet Tables", tables 1 & 2 lor further details

Source: LMIS, 1995

Flagging Out: The EU Registered Flagged Fleets 1985-1994

The EU Flagged Fleets have declined substantially over the last decade

The EU registered flag vessel count has declined by 2,873 vessels or 30%, the corresponding tonnage drop has been

34 million dwt or 21%

- The average vessel size under EU flag has increased from 16,800 dwt in 1985 to 19,400 dwt in 1994

The EU flagged fleet has contracted from 8,936 vessels in 1985 to 6,068 by 1994, representing a 32% fall. Deadweight

tonnage has been reduced by 30% to 104 million dwt over the same time period

- The average size of an EU vessel in 1994 is 17,600 dwt vs. 16,700 dwt in 1985

The vessel count under affiliated flagged fleets has declined only marginally, but tonnage capacity has increased by

73% to 26.4 million dwt

- This has been caused by the establishment of new registries such as Netherlands Antilles and a doubling of

tonnage in the Gibraltar and Bermudan flags, arising from an influx of larger sized vessels

00

Age Profile of EU Fleets

.

EU Registered Flag Vessels:

EU Owned Vessels:

Japan

Taiwan

South Korea

USA

Norway

NIS

World Fleet

1985

16

17

9

13

14

24

20

-

14

1994

r

21

19

9

13

16

28

29

13

17

Difference

+5

+2

0

0

+2

+4

+9

N/A

+3

Source: LMIS, 1995

Flagging Out: Age Profile of EU Fleets

The average age of the EU flagged and owned fleet has increased markedly (particularly the age of the flagged fleet)

The EU owned fleet has increased its age profile by 2 years over the past decade to

19 years, whilst the EU registered fleet has increased by five years to 21 years

In contrast the world fleet age profile has increased by 3 years to 17 years

It appears that EU owners have reinvested less in new tonnage than owners in

other geographical areas (particularly those in Asia)

CO

ro

o

Flagging Out of EU Fleets

Percentage of Vessels Flagged Out

0

Dry Bulk

General Cargo

Container

Liquid Bulk

RoRo

% 25/

1 | ,

EU Owned Fleet

50%

54%

47%

44%

29%

75%

68%

100%

Source: LMIS, 1995

Flagging Out: Vessel Types

Two-thirds of the EU dry bulk fleet is flagged out

EU owners have flagged out 68% of their bulk vessels

EU owners flagged out over half (54%) of their general cargo vessels and a large proportion (44%) of

their liquid bulk vessels

Vessels which operate under relatively stringent safety regulations (eg. Ro-Ros) are generally not

flagged out

ro

ro

ro

Change in EU Owned Fleets, 19851994

By DWT (millions)

Composition of EU Owned Fleet, 1994

By DWT

232

dvrt 14.4

.6

2T

259

40.7 <

6 . 4

1 2.6

A \

1.7

,003 OOI +0.03 tO.3 ' J

0.7

0.9

1.5 Hf

t

IS

LL O)

O

3

UJ

i

=D

C

LO

>,

)

^

01

c

2

LL

CJ)

O

!

C

)

OJ

D)

3

O

X l

3

_J

ra

c

I/)

3

<

>>

C

ro

i

O)

ID

10

XI

C

ra

4J

OJ

TJ

c

ra

C

u.

E

5)

OJ

K

ra

E

c

0J

Q

c

O)

T)

OJ

3

to

<u

OJ

IS

O)

3

111

" g " , .

F i

r r 'o

al

Aus,na

2% Spain 1% / ^ 0.2%

Netherlands \ 2 % / / ^ ^ Ireland

0.1%

Lux emb our g

0. 004%

Denmark

5%

Ger many

7%

Gr eece

4 8 %

Sour ce: LMI S V essel dat ab ase, 1995

Flagging out: Change in the EU owned fleets

The EU owned fleet increased by 12% in total dwt between 1985 and 1994

Over the past decade the Greek owned fleet increased by 40.7 million dwt,

more than accounting for the total increase in dwt of all EU owned fleets

Other significant increases were in the Swedish (6.4 million dwt) and Danish

(3.5 million dwt) owned fleets

These increases were offset by major decreases in the UK (-14.4 million dwt),

Spanish (-6.6 million dwt) and Italian (-2.6 million dwt) owned fleets

In 1994 the Greek owned fleet accounted for almost half of EU owned tonnage

r\j

ro

Change in EU Owned Fleets, 19851994

By Number of Vessels

Composition of EU Owned Fleets, 1994

By Number of Vessels

12.464

u

373 | |

372 | _ J_

94 +36 +28 .9 *

+4 *3

+ 3

11.426

4 25 .

12

ZZ

i l l 1 1

11

s

i I f

u ^ in E

I I I I l ' ' I

(/)

s

i

a.

E

a i I I II

(

5 I <*

I

< 13 S

3

3

LU

3

LU

Ireland 0.7%

Portugal 0.7% | Austrti

Finland 2%

Belgium

Spain 3%

France

Luxemburg 0.1%

Sweden 4%

Netherlands 6%

Denmark 7%

Italy 7%

Germany 14%

Source: LMIS Vessel Database, 1995

Flagging Out: Change in the EU Owned Fleets

The German and UK fleets have lost most vessels over the last decade. The 1994 EU fleet is fairly concentrated

ro

01

Between 1985 and 1994, the Spanish, German and UK fleets suffered a net loss of 372, 331 and 373 vessels

respectively. This combined loss accounts for 88% of the loss of the EU owned fleet over the same period.

The EU fleet is fairly concentrated with the top five EU owned fleets representing 8,953 vessels, some 78% of the fleet.

The Greek owned fleet (3647 vessels) accounts for over a third of the EU fleet. The UK accounts for 18% (1,991 vessels)

of the EU fleet and Germany for 14% (1,632 vessels).

- With 9,746 vessels, the same five EU country owners in 1985 accounted for 77% of the EU owned fleet. Greece

represented 30% of the fleet, followed by UK 19% and Germany 15%.

ro

CD

Change in EU Flagged Fleets, 19851994

By DWT (millions)

Composition of EU Flagged Fleet, 1994

By DWT

Sweden Portugal

2%

Luxembourg Finland

2 %

i n

5 %

Austria

2%! / /

3 %

Netherlands

3%.

Ireland

0.2%

Belgium

0. 1%

104

3.7 dwt

Germany

6%

2.9

0.04 O.04

r

l4

z

O

> E

j5>

c

$

(

3

UJ

C

ra

c

I

ra

3

e

o

.

ra

c

Q

"D

C

ro

ra

(

<

en

c

O

E

O

o

c

LL

S

S >

U.

?

CT)

S

3

UJ

Denmark

7%

Italy

9%

Source: LMIS Vessel database, 1995

Flagging out: Change in the EU flagged fleets

The EU flagged fleet decreased by 30% in total dwt between 1985 and 1994

ro

-NI

The UK, Finnish and Spanish flagged fleets account for 83% of this loss

Only the French, Greek and Luxembourg flagged fleets increased their

registered dead weight tonnage over the period

In 1994, Greek flagged tonnage accounted for 57% of total EU flagged tonnage

ro

oo

Change in EU Flagged Fleets, 19851994

By Number of Vessels

Composition of EU Flagged Fleets, 1994

By Number of Vessels

8936

124 111 .9 5 . 4 0 .1 2

_l2S

2 6066

zz

zz

'S "> >

s

l i

O)

I

3

UJ

1

3 a

I

f f

" I

I

E

'JS>

1

2

(

LL

(S

m

c

i

ra

S

O)

1

r

<

l

S.

3

UJ

Ireland 1.1% Belgium 0.7%

Portugal 1.5%

France 3%

Finland 3%

Spain 5%

Sweden 5%

Nelherlands 8%

UK 9%

Denmark

10%

Luxembourg 0.7%

Austria 0.5%

Greece

26%

Germany

12%

Note: Denmark Includes DIS (423 vessels)

Source: LMIS Vessel database, 1995

Flagging Out: Change in the EU Flagged Fleets

Several EU flags have lost large numbers of vessels over the last decade

The drop in EU flagged fleets is far more pronounced than in the EU owned fleets

In particular the German, Greek, UK and Spanish registers have lost over 400 vessels each

The EU flagged fleet is slightly less concentrated than the EU owned fleet: the top-six

registers account for 78% of the fleet

ro

co

o

Flag Composition of the Major EU Owned Fleets

1985

1994

% of Vessel

Numbers

100%

75%

50%

25%

% of Vessel

Numbers

100%

75% -

50%-

25% -

0%

Greece UK Germany Italy Denmark Greece UK Germany Italy Denmark

Other Flags E2D Affiliated Flags EU Rags Other Flags I V/ I Afflllaled Flags RSS1 International Secondary Registers I I EU Rags

EU flags

Affiliated flags

2nd Registers

Other flags

58%

y

4 1 % V 76%

1% " 17% # 1 %

'

96%

1%

41% 42% ' * 3 % ^: i - - ; . i

81%

6%

13%

40%

1%

-

59%

24%

16%

.' .

60%

44%

2%

* ' , m

54%

87%

1%

-

12%

19%

20%

50%

11%

Source: LMIS, 1995

Flagging Out: Flag Composition of the Major EU Owned Fleets

In 1985, the top five national owners flagged 61% of their fleets under EU flags. This proportion fell to 44% by 1994.

There is a noticeable contrast between the countries: UK, Greek and German owners tend to flag-out, while Danish

owners opt for the DIS and Italian owners generally remain with the national flag

The German fleet shows the greatest swing (some 24% of the fleet) from EU to non-EU flagging over the ten year period.

- This assumes that 198 East German vessels were not part of the German flag in 1985

In contrast, at least 87% of the Italian fleet remains with the national flag, only 5% less than in 1985

By 1994, 415 vessels (50%) of the Danish owned fleet are flagged under the Danish second register, the Danish

International Ship Register

ro

Analysis of EU owners "Other Flags"

DWT, 1994

Breakdown by Nationality of EU Owners Breakdown by Major NonEU Flag Used

88

1985

146

1994

J

EU Owned

Tonnage Flagged

outside the EU

Spain 1.5 (2)

Belgium 1.7% (2)

My 1.6% (2]

Roland 16% (2)

Franc 2.2% (3)

Denmark 37% <S) \

SwwJen 6 OX (6]

Ner*rUnd I 5% (2>

Ira. Pwi. Aust 0 4% (2)

/

146 Million DWT

(1994)

Greece

46 6% (68)

Manhal laiand 1.2% (2)

11.3% (2)

NIS1.4%(2) \ * ' '

St Vincent 2.4% (3) '

Singapore 36% (6>

Ohara 4 2% (5)

Bahamai

11.0% (16)

Malta

116%(17)

Ubaria 24 4 (36)

Cyprus IB.4% (28)

Panama

16 2% (27)

146 Million DWT

(1994)

Note: ( ) number DWT. Ire, Port, Aust = Ireland, Portugal and Austria

Source: LMIS, 1995

Flagging out: Use of "Other Flags"

In terms of DWT, Greece, UK and Germany account for 80% of the EU owned fleet which has been flagged out

Of the 146 million dwt flagged to vessels in non-EU or affiliate countries, 47%

(68 million dwt) is owned by Greek interests, 23% (38 million dwt) by UK owners

and 17% (11 million dwt) to German shipowners

The Liberian flag represents 24% of flagged out tonnage (36 million dwt). The

Cypriot (28 million dwt) and Panamanian (27 million dwt) flags in second and

third place, have market shares of 19% and 18% respectively

Analysis of EU owners' "Other Flags"

Number of Vessels, 1994

Breakdown by Nationality of EU Owner Breakdown by Major nonEU Flag Used

3523

195

Franca 2 0% (106)

Italy 2 0 \ ( 106)

Spam 2 0% (106)

Sweden 2 4% (128)

Denmark 3 9% (211)

Netherlands 4 0% (214)

5311

1994

J

EU Owned

Vessels Flagged

outside the EU

Germ any

16 6% (662)

Belgium 1 8% (97)

'. Port.Ausi 1 0% (49)

Finland 0 9% (46)

Singapore 2 l%(114)

Hondrus3 6%(192)

5311 Vessels

(1994)

Greece

40 8% (2166)

51 Vincent 5 1% (276

Antigua 6 6% (369)

Others 6 9% (411)

Baliamas 9 4% (504

Malta 10 2% (547)

PnlNpinet 1 2% (65)

Cyprus 22 0% (1163)

Panama

20 6% (1104)

Liberia

10 2%

(546)

5311 Vessels

(1994)

Nole: ( ) = number of vessels. Ire, Port, Aust = Ireland, Portugal and Austria

Source: LMIS, 1995

Flagging out: Use of "other flags"

In terms of vessel numbers Greece, UK and Germany account for 80% of the EU owned fleet which has been flagged out.

Five Open Registries have taken in 85% of the EU's flagged out vessels

Greece accounts for 41% (2168 vessels) of the 5311 vessels flagged to non-EU or

affiliated countries, followed by UK 23% (1,200 vessels), Germany 17% (882 vessels)

In terms of fleet percentages flagged out, the UK is the highest at 60%, followed by

Greece 51%, Belgium 57% and Germany 54%. In contrast, Italy is the lowest at 12%,

followed by Finland 21 and then Ireland 22%

The EU owned vessels are flagged out to 68 different flags, with the top ten flags

(Cyprus, Panama, Liberia, Malta, Bahamas, Antigua, St Vincent, Honduras, Singapore

and the Philippines) accounting for 4,900 vessels, representing over 90% of the flagged

out vessels

Open registries account for 5,000 (94%) of the flagged out vessels

en

Patterns of Flag Choice by Germany, Greek and UK Owners

European-Owned Vessels

Flagged to "other" flags

Selected European-Owned Vessels Flagged to the six major non-EU flags

(all open registers)

5311

Bahamas

Ger many

Cyprus

1985 1994

H J ^

Anti gua

Panama

3537 Vessel s

Mal ta

3537 Vessel s

Key

I I = German, Greek and UK vessels registered In Antigua,

Bahamas, Cyprus, Liberia, Malla and Panama

K V s N = Other European-owned vessels flagged outside Europe

Source: LMIS 1995

Flagging Out: Patterns of Flag Choice

Vessels owned by German, Greek and UK interests account for 64% of the EU owned fleet and their flagging out to the six

major Open Registries accounts for nearly 70% of all EU owners flagging out

The proportion of total Europe flagging-out accounted for by these three European fleets has remained fairly constant at

just under 70%

- Greek owners account for half of the 3561 vessels

The Cypriot flag has the most European-owned vessels from this sample (1063 or 30%), followed by Panama (932 or

26%)

The next few pages show for this sub-set of 3 EU owned countries and 6 Open Registries:

- Correlation between EU ownership and Open Registries

- The age profile of the sample

- The vessel size profile of the sample

- The vessel type characteristics of the sample

-^ 1

Largest European-Owned Fleets under Open Registry

In Vessel Numbers, 1994 Compared with 1985

Owner Nationality

Greece

UK

Germany

Totals

Cyprus

804

(+382)

27

(0)

232

(+159)

1063

(+541)

Panama

416

(-77)

480

(+45)

36

(-159)

932

(-191)

Liberia

129

(-51)

180

(-224)

127

(+69)

436

(-206)

Malta

439

(+324)

30

(+15)

28

(+24)

497

(+363)

Antigua

_

348

(+347)

348

(+347)

Bahamas

115

(+115)

134

(+113)

12

(+12)

261

(+240)

Total

1,903

(+693)

851

(-51)

783

(+453)

3,537

(+1,094)

Note: 804 = Current number of vessels In the flag

(+382) = Change in vessel numbers since 1985

Flagging Out: Largest European-Owned Fleets in Open Registries

Flagging out activity is increasing. Most European-owned fleets have flagged out to multiple Open Registries, but there are

"patterns of preference"

Net new additions to the six Open Registries (1,094 vessels) account for 31% of today's European

"contribution" to these six Open Registries

Two major traditional Open Registries (Panama and Liberia) are losing share to four relative newcomers

Liberia is the only flag used in a major fashion (i.e. over 100 vessels) by all three countries. However, the

Greek and UK use is decreasing over the ten year period.

There are some patterns of preference:

- The Greek and German owners show a preference for the Cypriot flag (1036 vessels)

- UK owners for the Bahamian flag (134 vessels)

- The Greeks are also increasingly using the Maltese flag (439 vessels)

- The Germans like the Antiguan flag (348 vessels)

CD

o

Age Profile of Largest European-Owned Fleets under Open Registers

In Years, 1994 compared with 1985

Owner Nationality

Greece

UK

Germany

EU Average

Antigua

^

12

(N/A)

12

(N/A)

Bahamas

17

(0)

15

(+5)

13

(0)

16

(+3)

Cyprus

19

(+1)

19

(+4)

14

(0)

18

(+2)

Liberia

17

(+5)

15

(+6)

10

(0)

14

(+4)

Malta

20

(-1)

19

(+3)

17

(-19)

19

(0)

Panama

21

(+2)

18

(+3)

19

(+4)

19

(+3)

Note: All figures in years

14 = Current average age of the flag

(+11) = Change in flag average age since 1985

N/A = Not applicable

Flagging Out: Age Profile of Largest European Fleets under Open Registry

Most of the non-EU flags are younger than the average age of the EU flag fleet (21 years). There is considerable variation of

average ages between owner country / Open Registry combinations

The German-owned Liberian-flagged vessels are the youngest fleet (10 years), followed by the German-owned Antiguan-

flagged vessels (12 years) and Bahamian flagged vessels (13 years). These three owner-registry combinations have not

increased their average age over the past ten years, suggesting a heavy influx of relatively new vessels. The UK vessels

flagged to the Bahamas register average between 14-15 years, with a five year increase in average age, since 1985.

The older flags include Panama (average age 18-21 years) utilised by the Greek and UK owners respectively, and the

Cyprus flag used by the Greek (19 years) and German (14 years) owners. The Maltese flag, used extensively by Greek

owners has an average age of 20 years, compared to 21 years in 1985.

ro

Vessel Size Profile of Largest European-Owned Fleets, under Open Registry

In thousand dwt, 1994 compared with 1985

Owner Nationality

Greece

UK

Germany

Antigua

^

4

N/A

Bahamas

45

(-41)

20

(-24)

8

(0)

Cyprus

30

(+13)

33

(+24)

9

(-D

Liberia

81

(+21)

64

(-14)

35

(-23)

Malta

34

(+18)

22

(+3)

9

(+8)

Panama

20

(+1)

31

(+14)

39

(+24)

Note: All figures in (000's) dwt

31 = Current average dwt per vessel in the flag

(+5) Average dwt change per vessel since 185

N/A = Not applicable

Flagging Out: Analysis of the major non-EU flags by vessel size

Average vessel sizes vary considerably by European owner / Open Registry combination

The Greek owned fleet comprises of significantly larger vessels than in 1985 and this is reflected in higher average vessel

sizes in the Open Registries used by Greek owners. In comparison, the Greek-owned Liberian-flagged fleet has increased

vessel size by 35 %; this is the result of an influx of liquid bulk vessels.

In contrast, the average size of the UK-owned, Bahamas-flagged fleet has fallen by 55%, due to a large movement of

relatively small general cargo vessels into the flag.

The Liberian flag shows smaller vessels for the German and UK owned fleets. This may be due to the scrapping of the

larger liquid bulk vessels. The UK-owned Panamanian-flagged fleet has seen an influx of liquid bulk vessels as a result of

which the average vessel size has almost doubled.

5

Vessel Type Profile of Largest EuropeanOwned Fleets under Open Registry

1994

fr.Vdfrt'

Mi',

Owner

Nationality

. y * , :

il.

. ' ; " *

Antigua

> , .

Bahamaa Cyprus Liberia

&tf

l a - V:

Malta

I

') ;

rf 'h^,

Panama

f <to.T

JM .< ,'

Greece

Germany

UK

General Cargo Dry Bulk

General Cargo General Cargo

Dry Bulk Dry Bulk General Cargo

Liquid Bulk General Cargo

General Cargo General Cargo Liquid Bulk Liquid Bulk Liquid Bulk

Flagging Out: Vessel Type Profile of Largest European-Owned Fleets under Open Registry

There are some patterns of correlation between vessel types and Open Registries

There are some easily identifiable correlations:

- The Antiguan, Bahamian and Panamanian flags generally comprise of general cargo vessels

- The Liberian flag is characterised by liquid bulk vessels

- Cypriot and Maltese flags have both general cargo and dry bulk vessels

The Liberian and Panamanian flags used by UK and Greek owners have seen a change in vessel type profile, with liquid

bulk vessels increasing in importance and a corresponding decline in general cargo and, to a lesser degree, dry bulk

vessels.

UK owners have increasingly used the Bahamian flag for general cargo vessels at the expense of dry and liquid bulk

vessels.

Dry bulk vessels have shown marked gains in the Greek-owned Maltese and Cypriot flags, whilst in the German-owned

Cypriot-flagged fleet their share has doubled since 1985.

In terms of absolute vessel numbers, container vessels on average represent less than 5 % of each owned fleet.

Therefore, container vessels do not appear as a major type of flagged out vessels.

- Nevertheless, the German owned fleet utilises the above flags for container vessels. For example, the German

owned Antigua flagged vessels account for 31 container vessels, Cyprus 43 and Liberia 21.

- In contrast, the Greek owned Cypriot fleet represents just 10 container vessels and the Liberian flag, one.

r n

O)

Flagging Out: Summary

While total tonnage under EU ownership has increased over the last decade, the degree of

flagging out has also increased substantially

- In 1994, EU owners registered nearly 47% of vessels under non-EU flags vs. only 28% in

1985 (In tonnage terms 56% and 38% respectively)

- Proportionately, EU owners have registered a greater share of their fleet under Open

Registries than owners in the rest of the world

The average age of the EU owned fleet is higher than the world average (19 years vs. 17), and

the average age of EU flagged vessels is even higher (21 years)

A significant portion of all vessel types and sizes are flagged out, and in particular, more than

two-thirds of the EU-owned dry bulk fleet is flagged out

The UK, Spain and Germany have seen the largest decreases in their owned fleets. Greece,

the UK and Germany have experienced the largest decreases in their flag registered fleets

A total of 5,311 EU-owned vessels, representing 146 million dwt, are currently flagged to non-

EU or EU affiliated flags

- Greece, the UK and Germany account for 80 percent of the vessel count as well as tonnage

- Open Registries (Cyrus, Panama, Malta, Liberia, the Bahamas and Antigua) account for 72

percent of this vessel count and 85 percent of the tonnage

Most European-owned fleets have flagged out to multiple Open Registries, but there are

"patterns of preference"

Flagging Out

of EU - Owned Vessels

Quantification

1^ (Dis) Advantages of Open Registries

Open Registries: Introduction

This section presents an overview of the differences between Open Registries and EU Flags, and in particular:

Quantifies the size and growth of Open Registries

Quantifies EU owners' use of Open Registries

Reviews the advantages of Open Registries, and highlights, in particular, the potential for important crew cost and

corporate tax savings

Presents the result of direct market research with shipowners on:

- Flag selection criteria

- Actual use of flags

- Comparisons between EU Flags and Open Registries

- The "mechanics" of choosing a flag

- Crewing practices

The Appendix contains further details on the three largest Open Registries (Liberia, Panama and Cyprus), and on

selected second registers in the EU and Norway

CD

o

Vessel

numbers

es

5000

300

3000

2000

1000

U MI

na M

11 7

H M

" a Sa. i t a

I H I I i i i l l l l f l l

Total: 15,515 vessels

19% of vessels in world fleet

45% of world fleet dwt

(up from 31% in 1985)

BOO

700

600

500

0 -

3O0

200 -

100

0

749

470

123

To

f I

3

5

3

47 40

i . i

If

f

Total: 1,502 vessels

2% of vessels in world fleet

7% of world fleet dwt

(up from 0.25% in 1985)

Notes: (1) Defined by International Transport Workers Federation

( ) = country of affiliation

Source: Lloyds Register data all vessel types at December 31st 1994

Open Registries: Types of Registers

Open Registries and Second Registers in Europe comprise over half of world fleet tonnage

National Registers treat a shipping company in the same way as any other business in that country.

International or Open Registries are set up with the objective of offering shipowners internationally competitive terms and

to provide fee income to the country of registry. There are two types:

- Flags of Convenience (FOC) are defined in the Donaldson reporf

1)

as "registers where the State does not have the

capability of supervising the safety of its ships or does not do so effectively".

- Second Registers - copy FOCs in so far as they have considerable freedom for manning purposes but they target

mostly nationally owned vessels. They are accountable to an effective Maritime Authority and are liable to varying

degrees of tax.

The ITF maintains a list of what it considers Open Registries (FOCs); this list currently comprises 22 Registers

Forty-five percent of the world fleet's tonnage (dwt) is in Open Registries

- Only 18% of vessels in the world fleet, because smaller coastal vessels are less often flagged out

Seven percent of the world fleet's tonnage (dwt) is under a Second Register in Europe

- Again, typically larger vessels

Source: (1) Report of Lord Donaldson inquiry, May 1994

CTI

sr

) fleg etrlef *

12,000

10,000

8,000

Vtt

number o

000

4,000

2,000

8,234 205.0

11,287

292.8

300

250

200

DWT

1 5 0

(millone)

100

50

1985 1994

m

1994 Statu*

9Si&1994 Status pf theTop Fh/ Open Registri e

> Five Open Registries

7,000

S

6,0001 '

5,000

V M

4

'

number

3,000

2,000

1,000

O

97.1

I

::

if

946

3

39.3

!:

s

35.4

PH

: ,

26.2

100

90

80

70

60

DWT

50 (mlllons)

40

30

20

MO

o

Panama Liberia Cyprus Bahamas Malta

CAGR 4% 4%

% All Open

Registries

98% 91%

l ~| Vessel numbers DWT

Source: LMIS. 1995 all vessel types

Open Registries: Growth of Open Registries

The Open Registry fleet is still very concentrated, but new competitors are emerging

In 1994, the top-five Open Registries accounted for 91% of all vessels under Open Registry, down from 98% in 1985

Since 1985, the top five Open Registries by dwt (Bahamas, Cyprus, Liberia, Malta and Panama) have grown at an annual

rate of 4% in vessel count and dwt)

- These five flags represent 14% of the world fleet vessels and 42% of dwt

- They have generally been in existence for more than 30 years

A series of newer Open Registries have come into existence since the 1980's

- Collectively, they now account for 9% of the tonnage under Open Registry

Open Registries accounted for 3,200 vessels (26%) of the 1985 EU owned fleet, this increased to 5,000 vessels (44%) of

the 1994 fleet. Cyprus, Panama, Liberia and Malta are the most utilised flags, representing 3,380 EU owned vessels by

1994

The Greek fleet has 58% of its fleet (2,109 vessels) represented by Open Registries, followed by Germany (53%, 860

vessels), UK (53%, 1,060 vessels) and Belgium (47%, 80 vessels). Countries with the lowest percentage of owner's

fleets flagged to Open Registries are Italy (10%, 82 vessels), Denmark (18%, 151 vessels) and Ireland (19%, 12 vessels)

en

co

994 Ranking of the Open Registries

By number of EU owned vessels

Number of vessels in Open Registries Percentage of Open Registry owned by EU interests

Cyprus

Panama

Malta

j **

Liberia

Bahamas

Antigua

St. Vincent

Honduras

Neth. Antilles

Vanatu

Canary Island

Bermuda

Gibraltar

Lebanon

Belize

Sri Lanka

Tuvalu

Myanmar

Marshall Island

Cayman Island

Mauritius

Cook Island

1183

C

.

1104|

1 ' I

547 C

546 C

5041

369 C

276 C

192 C

105 C

34

301

261

24|

15|

141

11

7

6|

6

5

2

0

1 1 ! 1

^| 76%

Z125%

ZJ36%

ZI 48%

58%

|35%

Z]24%

| ! 1M

12/%

Iur.

141%

j ' f i v .

|11%

I 8%

ZI 38%

| t . ! . " .

| 9%

18%

Z] 25%

Z]18%

0%

1 1 1 I

1400 1200 1000 800 600 400 200 20% 40% 60% 80% 100%

Note: Percentage of fleet refers to cargo carrying fleet

Source: LMIS, 1995

Open Registries: EU Ownership

The five most popular Open Registries have attracted over 500 EU-owned vessels each. The proportion of the Open Registry

represented by EU interests varies considerably

en

en

Cyprus (1183 vessels) and Panama (1104) have, in fact, attracted over 1000 vessels

each

EU interests account for the majority of the Open Registries of Cyprus, Malta and

Antigua

The largest proportion of an Open Registry used by EU shipowners is Gibraltar (98%)

followed by the Canary Islands (90%) and the Netherlands Antilles (88%)

en

CD

Open Registries: EU Owner Distribution

Greece, the UK and Germany provide the bulk of EU owned vessels under Open Registry. For each of these countries,

between 5060% of the owned fleet is under Open Registry

EU Owned Fleet

Greece

UK

Germany

Netherlands

Denmark

Spain

Sweden

France

Italy

Belgium

Finland

Portugal

Austria

Ireland

Luxem bourg

2109

2500 2000

1994 Degree of Flagging to the Open Registries

1060

B60

251

151

130

101

'* m&m

tttty.:r=.. I '* > ^t?vj> '< ~\ se

r^i^:'s. iile Mmm ^m^i^j^iA

53

^wmM^^m^^^

mi

18

KKai &^^ Mfl i Si a

34

82

80

46

19

13

12

0

23

a^iiZtLI^S

bit*Ji.iJA4A4iS

26

rmho

$wmm lv:

:

.5'ta^l&.i'i

J

Jj

47

" " * &

21

ktmw&mm*

mm*

^ _ _ 19

1500 1000 500 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60%

j | Number of vessels in Open Registries { | % of Fleet In Open Registries

Open Registries: Advantages of using Open Registries

There are several advantages to Open Registries:

Anonymity of Ownership:

- This may enable the shipowner to escape tax liabilities in the country of establishment.

- Potential to avoid responsibility for failure to observe laws relating to safety, environmental protection and labour

conditions.

Economic Factors:

- Utilisation of non-nationals and perhaps lesser known classification societies.

- Freedom to repair vessels anywhere, without being tied to national shipyards.

Political Factors:

- Ability to trade world-wide without any restrictions imposed by the flag state, e.g. by-pass trade embargoes.

- Avoidance of overseas discrimination against vessels trading under certain flags, e.g. Taiwanese operators vessels

invariably flagging out since Taiwan is only recognised as a state by a small number of countries.

- Freedom from requisition in time of conflict.

Vessel registration is low cost, simple and can generally be completed within one day.

The traditional FOCs are accepted by the international lending institutions and the insurance industry does not weight

premiums by flag.

In conjunction with ship registration, many of the FOC states offer attractive corporate jurisdictions including:

- No Government intervention

- Easy transfer of capital

- Tax free environment

- Free circulation of the US dollar

en

vi

en

CD

Open Registries: FlagSensitive Costs

Crew cost and corporate tax are the most flagsensitive cost categories

Ship operating cost

ICrew cost

Maintenance & Repairs

Stores & Supplies

Lubricating oil

Insurance

Drydocking accrual

Ship management

Capital cost

Voyage cost

Fuel cost

Port dues

Canal dues

Light dues

Tug & pilotage costs

Administration &

management

Sales & commission

General management

Corporate taxes

oM;H3elatd

^ Flexibility ^f

..

bfr'" ji

Crew size, net wages, taxes, social charges, effective working days

Country regulation, age of the vessel

Engine type, ratio port/sea days, crew size

Engine type, maintenance and repair policy

Age, type of the vessel, purchase cost

Classification rules, maintenance and repair policy

Headcount: personnel, recruitment, legal, training, engineering, etc.

Purchase cost, interest rate, terms of the loan

Engine type, speed, # miles

Size/Dimension

Size/Dimension

Size/Dimension

Size/Dimension

Wages, taxes, social charges

Wages, taxes, social charges

Legislation

Note: (1) Requires change in shipowner strategy

Open Registries: Summary of Crew Cost Differences for Ten Vessel Types

Crew cost differences between selected EU flags and lower-cost Open Registry vessels range from $0.1 to $1.2 million per

annum, or +22% to +333% over the lower-cost Open Registry

Crew Cost Gap

EU Flags

Lower cost

Open Registry

(non ITF)

Annual Cost

Difference <*>

(in '000 $)

A

Cost Index m

Tankers

Suezmax (140 000 dwt)

Product tanker (40 000 dwt)

Bulkers

Cape Size (150 000dwt)

Panamax (65 000 dwt)

Handy-size (28 000 dwt)

Container

Large (4 000 TEU)

Line - Haul (2 700 TEU)

Deepsea Feeder (1 500 TEU)

General Cargo

Breakbulk (15 000dwt)

Ro-Ro (6 000 dwt)

Italy

Italy

Italy

Italy

UK

Neth.

Germany

Germany

Germany

Italy

Greece

Greece

Greece

Greece

Greece

Denmark

France

Greece

Greece

Greece

Panama

Panama

Panama

Cyprus

Panama

Panama

Panama

Panama

Cyprus

Panama

1 228

1 192

865

794

472

630

1 144

1 144

1221

587

185

179

155

149

144

380

1 124

91

88

82

368%

370%

313%

304%

227%

279%

433%

433%

383%

265%

140%

141%

138%

137%

139%

208%

427%

126%

122%

123%

(1) Against lower-cost Open Registry

en

eo

O)

Open Registries: Drivers of Crew Cost Differences

Differences in number of people on board, nationality of crew and officers, number of days worked, gross wages, social charges

and travel cost differences in crew cost

Example for Suezmax Tanker (140,000 dwt)

Italy

Crew Costs. 1993

Greece Liberia

()

Panama

(2)

Number of Officers Required

Number of Seamen Reauired

14.1

26.6

11.5

21.2

10.8

21.2

10.2

207

European Officer Gross Wage (per Month)

NonEuropean Officer Gross Wage (per Month)

European Seaman Gross Wage (per Month)

NonEuroDean Seaman Gross Waae (Der Month

$2.717

$1,584

$2.041

$521

$2,152

$521

$1,828

$368

Overtime fin % of Gross Wage)

Leave (in % of Gross Wage)

26%

63%

Social Chames naid by emDlover fin % of Gross Waa. 39%

33%

31%

8%

9%

36%

2%

10%

24%

2%

$3.6201 Total Travel Cost (Officers plus Seameni

$4.799 $2.945 5.Q35

Total Cost per Officer

Total Cost per Seaman

$7.209

$4.449

$3.785

$977

$3.424

$977

$2,611

$735

$38.197 I Total Crew Cost per month $140.519 $53.591 $50.346

$1,256 | Total Crew Cost per dav

$1520 $1.762 $1.655

Note : (1) 'Higher F0C means minimum ILO and ITF conditions are met or exceeded (wages, accommodation, etc.)

(2) 'Lower FOC means ILO and ITF standards are not necessarily respected

Sources : Interviews with manning agencies, shipowners, shipowner associations, seafarer unions; Mercer analysis

Open Registries: Corporate Tax Rates

The percentage of corporate tax levied on pre-tax profit of maritime enterprises varies considerably across countries

? Country ^ U ^ ,

Austria

Belgium

Denmark

Finland

France

Germany

Greece

Ireland

Italy

Luxembourg

Netherlands

Portugal

Spain

Sweden

UK

Cyprus

Liberia

Panama

% Tax on Profit

34.0%

39.0%

25.0%

34.0%

33.3%

27.0%

0.0%

10.0%

52.2%

33.3%

35.0%

10.8%

35.0%

28.0%

33.0%

0.0%

0.0%

0.0%

Comments r

Ordinary corporate rate

Ordinary corporate rate

If paid in the current accounting year

Ordinary corporate rate

Ordinary corporate rate

For international trade operations

Rate specific to shipping operation

Ordinary corporate rate

Ordinary corporate rate

Rate specific to shipping operation

Plus $6900 if profit > $138 000

Rate specific to shipping operation

Ordinary corporate rate

Ordinary corporate rate

Ordinary corporate rate

Rate specific to international shipping operation

Rate specific to international shipping operation

Rate specific to international shipping operation

CD

CD

Open Registries: Tonnage Tax Systems

Some countries, such as Greece, Cyprus, Liberia and Panama, have adopted a system of tonnage tax. This is a tax based on the

Gross Registered Tonnage or the Net Registered Tonnage of each vessel

fflaWfu&u&SMMGreece

Tax on Gross Registered Tonnage (GRT)

For each GRT:

Up to 10 000 GRT

Between 10 000 and 20 000

Between 20 000 and 40 000

Between 40 000 and 80 000

In excess of 80 000

$1.2

$1.1

$1.0

$0.9

$0.8

This figure is then multiplied by the relevant factor:

Age of the vessel:

Up to 4 years

Between 5 and 9 years

Between 10 and 19 years

Between 20 and 29 years

Over 30 years

0.911

1.634

1.599

1.544

1.170

I

. i , ' i r ;.'

'MmMKmii &wx* &fMamm

Tax on Gross Registered Tonnage (GRT)

For each GRT:

Up to 1 600 GRT $0.26

Between 1 600 and 10 000 $0.16

Between 10 000 and 50 000 $0.06

In excess of 50 000 $0.04

This figure is then multiplied by the relevant factor:

Age of the vessel:

Up to 10 years 0.75

Between 11 and 20 years 1.00

Over 20 years 1 30

tmmmmm^ SVA-. ). ;V, ,

Tax on Net Registered Tonnage (NRT)

$0.40 for each NRT, plus an annual tax of $1 800

i^^^fc:;.Panama : fr ^ ^ I j f c

Tax on Gross Registered Tonnage (GRT)

$0.10 for each GRT, plus an annual tax of $3 500

Open Registries: Summary of Corporate Tax Gap for Ten Vessel Types

Corporate tax differences between the selected EU flag and lower cost FOC vessels range up to $960,000 per annum.

Tankers

Suezmax (140 000 dwt)

Product tanker (40 000 dwt)

Bulkers

Cape Size (150000dwt)

Panamax (65 000 dwt)

Handysize (28 000 dwt)

Container

Large (4 000 TEU)

Line Haul (2 700 TEU)

Deepsea Feeder (1 500 TEU)

General Cargo

Breakbulk (15 000 dwt)

RoRo (6 000 dwt)

EU Flags

Italy

Italy

Italy

Italy

UK

Neth.

Germany

Germany

Germany

Italy

Greece

Greece

Greece

Greece

Greece

Denmark

France

Greece

Greece

Greece

Lower cost

FO

(non ITF)

Panama

Panama

Panama

Cyprus

Panama

Panama

Panama

Panama

Cyprus

Panama

Corporate Tax Gap

A

958.2

494.4

709.1

439.3

202.8

782.1

372.0

253.3

168.1

308.9

Annual Cost

Difference <

1

>

iin '000 $)

i

107.1

38.8

119.5

58.8

27.2

752.8

460.6

29.3

16.3

4.6

(1) Against lowercost FOC

CD

2

7%# i ,

Rag

Cyprus

Liberia

Panama

DIS

NIS

Isle of Mar

=

Registration Costs for an Aframax Tanker

Ownership

Registration in

Relevant Country

$250ID

$1,525(2)

$500 p.a.

1

Initial Annual Fee

Registration

Fee

$6,080 $6,450

$2,500 $12,475

$6,500 $8,365

$81,5300) $7

(6

53

$24,020) $16,084)

$788

,

Other Fees

$40 p.a.

$1,767

$100

Note: (1) Company has a presumed share capital of under $5,000

(2) Foreign maritime entity

(3) Based on secondhand vessel price of $20 million

(4) Combined Maritime Directorate and NIS fees.

(5) It Is assumed the vessel has 27 crew, secondhand value of $20m; 100,000 dwt; 51,000 grt; 25,500 nrt; 1986 year of build

Open Registries: Flag Registration Costs

Registration fees are low in comparison to the value of a vessel

en

Registration fees do not appear to be a primary criteria in choosing a flag

- E.g., the Isle of Man Registry has a one-off registration fee of $788, but has only attracted 117 vessels.

Liberia has a low, fixed registration fee and a relatively high annual fee compared to other Open Registries,

determined on a tonnage basis.

- Cyprus and Panama's initial and annual fees are both determined on the basis of weight and, for an

Aframax tanker, are about 50% below those of Liberia.

The second registers such as DIS and NIS have significantly higher registration fees.

Age Limits and Classification Requirements

Flag

Cyprus

Liberia

Panama

DIS

NIS

Isle of Man

Age limitations of vessels

17, can be increased to 23 years

subject to certain conditions!

1

)

20 years, but can be increased on a

case-by-case basis

None, but over 20 years a special

inspection is required

None*

None*

None*

Nominated Classification Societies

IACS members and the Greek, Romanian

and Cypriot classification societies

IACS members

IACS members and others including

Portuguese, Greek and Yugoslav

classification societies

ABS, BV, GL, DnV, LR, NKK

ABS, BV, GL, DnV, LR

ABS, BV, GL, DnV, LR

Note: (1) Cyprus unlike Liberia or Panama does not use independent surveyors for the vessel inspection prior to registration.

* No age restrictions, "provided the technical standard of the vessel is acceptable*.

IACS (International Association of Classification Societies) membership includes: American Bureau of Shipping (ABS), Bureau Veritas (BV), China Classification Society,

Den Norske Veritas (DnV), Germanischer Lloyd (QL), Korean Register, Nippon Kaiji Kyokai, (NKK), Polish Register, Italian Register, Russian Register.

Open Registries: Age Limits and Classification Requirements

Age Limits and Classification requirements differ by flag

Classification societies can be broadly divided into three:

- The top six: ABS, BV, GL, DnV, LR and NKK are generally perceived as industry leaders, and are often nominated

as only acceptable shortlist by European flag state authorities

- Other members of IACS are regulated by an internal code of ethics and work practices

- Other classification societies e.g., the Greek or former Yugoslav classification societies.

Most OECD National flag registers and the European second registers (e.g. DIS, Isle of Man) use the top six classification

societies. Open Registries generally require IACS membership, plus the option of using "other" classification societies.

- For example the Cyprus flag (with a high proportion of Greek owners) can use the Greek, Cypriot or Romanian

societies.

Survey and repair costs are dependent on the individual vessel, however classification societies do have different

interpretations of convention requirements. Survey costs can be substantial (up to $15,000) as can the repair

requirements.

Most Registries require additional surveys beyond a certain age, but there is no consistent approach

CD

vl

CD

CO

Open Registries: Shipowner Interviews

We interviewed 20 decision makers in Ship Owning/Managing Organisations with

the following characteristics:

EU based companies

Significant fleet size (more than 10 vessels)

Significant proportion flagged out (generally more than 30% of vessels)

Company

Louis-Dreyfus & Cle

Baum & Co.

Dohle Peler

Schulte Bernard

Thien & Heyenga

Transocean Ship management

Cominos Enterprises

Eastern Med. Maritime

Golden Union Shipping

Good Faith Shipping Co.

Naftomar Shipping

Unlmar Maritime Services

Poseidon Scheepvaartbedrijf

Shell Tankers BV

ICB Shipping

BP

Holbud Ship Management

P&O Bulk Shipping

Shell Tankers

Stephenson Clarke Shipping Ltd

Country

France

Germany

Germany

Germany

Germany

Germany

Greece

Greece

Greece

Greece

Greece

Greece

Netherlands

Netherlands

Sweden

UK

UK

UK

UK

UK

Respondent

Assi. Fleet Manager

Chartering Manager

Registration Manager

Fleet Manager

Director

Inspector

Chartering Manager

Operations Manager

Director

Commercial Manager

Fleet Manager

Head ol Insurance

Broker

Fleet Supply Manager

Marine Sup. Ini.

Marine Super. Int.

Operations Director

Group Manager

Project Economist

Managing Director

Total

Fleet Size % Flagged Out Vessel Types

22

21

21

24

20

40

21

27

25

33

30

26

30

15

14

12

20

11

26

13

4SI

95%

100%

100%

100%

100%

100%

86%

96%

12%

100%

100%

100%

33%

33%

93%

92%

100%

100%

64%

46%

Average 82%

Dry Bulk

Dry Bulk, Container

Container, Dry Bulk

Container, Tanker

Container, Tanker

Tanker, Dry Bulk, Gen. Cargo, Container

Gen. Cargo, Dry Bulk

Dry Bulk, Tanker

Dry Bulk

Gen-Cargo, Dry Bulk Tanker

Tanker

Dry Bulk

Dry Bulk, Container

Tanker

Tanker

Tanker

Dry Bulk

Dry Bulk

Tanker

Gen. Cargo

Owner or Manager

Owner

Manager

Manager

Manager

Owner

Owner

Owner/Manager

Manager

Owner/Manager

Owner/Manager

Manager (part ol Owner Group)

Manager

Manager

Owner

Owner

Owner

Manager

Owner/Manager

Owner

Owner

Note: The sample is broadly representative ot the EU Owned Fleet in terms ol owner nationality, but is not designed to be a statistically representative sample of shipowner segments

due to the small overall sample size

Open Registries: Interview Sample

The flags used by the sample are a good reflection of the full EU fleet

Interview Sample Fleet

Not Flagged Out

18%

451 Vessels

EU Flags

France 4% .^eO

e

/

GIS 12%

UK 15%

Netherlands

36%

% of vessels

41

Greece 32%

NonEU Flags

Bermuda 3% t

n e r

s 6%

Kerguelen 3% LJ

Hong Kong 4% A T \ \

Isle of Man 5%

^ v Panama 24%

_^ | % of vessels

Liberia I Z l \ I

12% \ y Z I \ / Cyprus 17%

Antiga 12% *

Malta 16%

Source: LMIS Vessel Database, 1994

CD

CO

o

Open Registries: Interview Sample

Dry Bulk and Container Vessels are represented more heavily in the sample than in the full EU fleet

Vessel Types

Interview Sample EU Fleet

General Cargo

13%

Container

14%

Tankers

29%

General

Cargo

55%

Tankers

24%

Dry Bulk 17%

Container 4%

Dry Bulk 44%

Source: LMIS Vessel Database, 1994

Open Registries: Use of Flags

Owners use multiple registries for their vessels but Cyprus, Liberia and Panama are the most popular

Open Registries

EU Flags

No. of Owners

Cyprus [

Liberia

Panama

Antigua

Malta

Bahamas

Hong Kong

Kerguelen

St. Vincent &

Grenadines

Singapore

Isle of Man

Others

Source: Shipow ner/l

6 | _

Manager

4 |

3|

3|

3|

41

2|

21

21

21

Interviews

No. of Vessels

| 52

Z l

4 2

! >''

H

4

1 13

Z U io

|3

I

3

117

~^\22

^ ] 44

~]53

No. of Owners

GIS 4 |

Greece 3 [

UK 3

Netherlands 2

France 2

Italy 11

Sweden 1

No. of Vessels

10

26

|12

3

1

]1

30

- v i

ro

Number and Concentration of Flags Used

5

4-

3-

fJumbers of

Owners

2.

1-

0-

2

- h

5

-+-

5

- h

4

2 2

-t- - h H

1 2 3 4 5 6

Number of Flags Used

70

T

60 --

50- -

Average % 40

of Vessels

for each

Owner

30

20 --

10 -

0

64.1%

2 1 . 5 %

8.9%

,

3

3 %

, 1- 3 % 0. 9%

| |

+

1st

Flag

2nd

Flag

3rd

Flag

4th

Flag

5th

Flag

6th

Flag

Average Number of Flags Used = 3.25

Open Registries: Number and Concentration of Flags Used

Owners/Managers use a mixture of flags for their fleet but generally have a 'preferred flag'

Ship owners/managers use, on average, over three different flags for their fleet

A 'preferred' flag is used for the majority (64%) of the fleet with other flags being used as

alternatives

German owners are more diverse in their use of flags than other nationalities:

- 4.6 flags/owner versus 2.9 for other nationalities

Flags other than the preferred flag are used for historic reasons or in special circumstances:

- Owner's insistence

- Charterer's request

- Trading region reasons

- Building Subsidy requirements

-si

si

Flags Used by Different Nationalities

Number of Vessels

Open Registries EU Flags

Owner Countries/'

Germany

Greece

UK

Netherlands

France

Sweden

Total 90

WMy^AVW^/4

36

14

3

8

61

58

58

44

44 43

17

17 13

11

11

10

m/

1&&AP

</*

O7 OV OW>W

5

5

1

1

2

4

1

2

3

1

2

3

3

3

2

2

1

1

Open Registries EU Flags

Number of Owners

Owner Countries / <?

wm-

Germany

Greece

UK

Netherlands

France

Sweden

Total

Open Registries: Flags Used

Clear patterns of flag usage are evident among different nationalities

Panama, Cyprus and Liberia are used heavily by almost all nationalities

Greek owners/managers make little use of Liberia but heavy use of

Malta in addition to Panama and Cyprus

- Reputedly cheaper than Panama or Cyprus

- No political problems due to status as independent state

UK owners/managers make little use of Cyprus but frequently use Isle

of Man, Hong Kong and Bermuda

- These three flags allow the Red Ensign (UK flag) to be flown

German owners/managers favour Antigua in addition due to:

- Local flag registry office in Germany

- Ability to use national crew licences

->l

CD

Open Registries: Flag Selection Criteria

When unprompted, cost issues are the key criteria in flag selection, closely followed by union considerations and efficiency

and location of the flag registry

Total Number of Mentions

Unprompted Factors 0

Overall Costs

Crew Costs

Union Considerations

Efficiency/Location of Flag Registry

Owners Choice

Minimum number of Hags

Annual Registration Fees

Customers'/Charterers' Prelerence

Political Factors

Availability ol Crew

National Consciousness ('Flying the Flag')

Banks/Underwriter's Agreement

Others

- t - - 1 ..1

14

14

14

12

12

|2

12

12

13

13

13

Key:

] Factors not in prompted list

Source: Interviews with EU Shipowners/Managers

Open Registries: Flag Selection Criteria

When prompted, issues relating to crew cost and corporate tax are by far the most important criteria in flag selection

Importance Rating (1-5 scale)*

Prompted Factors 0

Crew costs

Tax and Other Financial Factors

Political Factors

Costs of Compliance

Annual Registration Fees

Union Considerations

Customers'/Charterers' Preference

Corporate Confidentiality

National Consciousness ('Flying lhe Flag')

Building Subsidies

Maintenance & Safety Requirements

Off-Shore Management

Operating Subsidies

Trading Region of World

Choice of Classification Society

' Mean Score ot Respondents weighted by number of vessels

Respondents rated each tactor on a 1-5 scale where 1 is less important and 5 is most important

- J

-si

>l

co

Comparison of Prompted and Unprompted Responses

Importance

Rating

Scale (1-5)

Number of

Mentions

Key: [ J Prompted Factors | | Unprompted Factors

Open Registries: Flag Selection Criteria

Unprompted and prompted responses are largely consistent, with the exception of corporate tax

Costs, particularly crew costs, are the key factors in both prompted and

unprompted responses

There are fewer unprompted mentions of corporation tax as a key criteria

than the corresponding prompted importance rating:

- Possibly included in Overall costs' category of unprompted responses

Union consideration given more emphasis in unprompted responses

Efficiency and location of flag registry, together with minimising

administration by reducing the number of flags used, are important

considerations that are not in the prompted list

For managers, the view of the owner is important and may, in some cases,

override the manager's own opinion

CO

00

o

Open Registries: Vessel Characteristics

There appear to be no general relationships between vessel characteristics and flag selection

Ship owners and managers did not suggest a relationship between vessel characteristics (type, size,

age, etc.) and their choice of Open Registry

Additionally, no criteria based on vessel characteristics were identified as influencing the decision of

whether to flag a vessel to an Open Registry or EU flag

Some Open Registries (e.g. Cyprus, Bahamas) restrict the age of vessels than can be registered. Thus

the age of a vessel may actually influence the choice of Open Registry in certain circumstances

Open Registries: Nationality Differences in Flag Selection

There are some differences in flag selection by owners/managers in various EU countries, but these do not override the

general conclusions

By Nationality of Owner/Manager

. ' ' . " " . ' ' . ' . . ' . . " , " I

1

! .

Cost is the key issue (all factors are taken together)

Worldwide recognition of flag is important

For ship managers, owner input is a critical factor in

the flagging decision

l l i i i Wfe,Qe^?|l i Ji i ^^

Trading region is an important factor

Efficiency and location of registry taken into account

Generally consider more factors than other

nationalities

^TWUSS'SI

4l?feifiiifc

;

*

fSBET. :

Bae ' '"

Red ensign on vessels is important (available with

UK, Bermuda, Gibraltar, IOM, HK flags)

Aim to minimise bureaucracy and paperwork

$$Othr*(

Wanting to fly national flag is still a factor, although

overridden by cost considerations

Availability/requirements for subsidies a key

determinant

CD

CD

ro

Rating of Open Registries

Panama

Cyprus

Antiga

Liberia

Malta

Top 5 Prompted and Unprompted Criteria

~.

wners,

ing Fit

8

4

+ +

+ +

+ +

+ +

+ +

Tax Level

m

* ,

+ *'

~

+ +

+

^

iM

_ _

Very good

Good

Neutral

Poor

Very poor

Source: Shipowner/Manager Interviews, based on qualitative Interpretation of benefits and drawback of Individual flags

Open Registries: Rating of Open Registries

The Top 5 open Registries (Panama, Cyprus, Antigua, Liberia and Malta) are rated very similarly by Owners/Managers

Overall, few differences between the top 5 Open Registries

Specific differences:

- Panama has very low annual costs

- Cyprus has significant political problems with Turkey

but balanced by good union recognition

00

Open Registries: Comments on Open Registries

Specific comments on Open Registries include:

___

y

~

Negative ! .

Cyprus

Liberia

Panama

Antigua

Malta

Positive

;* :

Well organised and efficient "more than just a

mailbox"

Good international reputation

Efficient administration

Privileges in Panama Canal

Can use second flag at same time

Local office in Germany

Can use national licences for crew

Independent state with no political problems

No local office in Germany

Problems with Turkey

Will not register vessels over 17 years old

High registration fees but offset by lower tax

Frequent inspections required

Surveys required every year

Special crew licences required

Higher port charges than other Open

Registries

Will not register out of class vessels

Source: Shipowner/Manager Interviews

CD

cn

CD

CD

Rating of EU Flags

%$* Union

Rcognition

Greece

i e r s

Inf Flag

JciP

Cstq

K

wj . . . ;;i'/!'<'* . i

^Tax Level r

mm

\':

t Politicare

r,.'Factofs I.

+ + + +

Germany

(International

Register)

4 + = + + =

a

UK

Netherlands

France

3

2

2

+ +

+ +

+ +

M m

't , ' "

+ +

+ +

+ +

WBBSM ESiMll

++

+

=

Very good

Good

Neutral

Poor

Very poor

Source: Shipowner/Manager Interviewe, based on qualitative interpretation of benefits and drawback of specific flags

Open Registries: Rating of EU Flags

EU flags are considered to be significantly less attractive than Open Registries in the areas of crew costs, tax levels and

annual costs

Between EU flags there is greater differentiation than between Open Registries

Greece stands out as the most attractive EU flag, particularly due to

competitive crewing costs and favourable tax treatment for shipping companies

based on a tonnage tax rather than a corporate tax rate

The German International Register is viewed as favourable in terms of crewing

costs but this is offset by union recognition issues

UK, Netherlands and France are viewed as similar and considered to be

expensive for all factors; Netherlands particularly so for annual costs

00

--

00

CD

Open Registries: Comments on EU Flags

While EU flags are seen to be expensive, they do provide some secondary benefits

Netherlands

Greece

UK

Germany

(International Register)

France

MMU

[Positive W f t

Building & operating subsidies available

Often the charterer's or owner's preference

Discount repairs in Greece

Lower insurance costs than Open Registries

Union approval

Able to fly UK flag

Building subsidies available

Crewing flexibility

Good safety record

Very expensive

Lack of availability of Greek officers

Expensive for all factors (crew, annual fees,

certification etc.)

Bureaucratic and inflexible in interpretation of

maintenance ol safety requirements

ITF threatening to classify as FOC

More expensive than Open Registries

Expensive

Open Registries: International Secondary Registers

International Secondary Registers are unlikely to be used by non-nationals in preference to a traditional Open Registry

GIS is considered to be the same as the full German flag by German

companies but with commercially viable costs

International secondary registers viewed as not applicable or not available

to non-nationals

Few advantages perceived of ISR's over traditional Open Registries, except

the ability to fly the national flag - rarely an important factor, particularly for

non-nationals

Viewed as more expensive than traditional Open Registries

CD

CD

CD

O

Decision Process

Who manages

decision process?

> V . :

Managing Director

Finance Director

Operations Manager

Fleet Manager

Other

' : : M^f ^.^ r

' Shipowners!?

'

0%

0%

0%

17%

] S3*

BIB^KSPP]

78%

8%

8%

8%

0%

Who signsoff the

decision?