Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Insurance Cases 1

Enviado por

Leogen Tomulto0 notas0% acharam este documento útil (0 voto)

66 visualizações11 páginas1st batch of cases

Direitos autorais

© © All Rights Reserved

Formatos disponíveis

DOCX, PDF, TXT ou leia online no Scribd

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documento1st batch of cases

Direitos autorais:

© All Rights Reserved

Formatos disponíveis

Baixe no formato DOCX, PDF, TXT ou leia online no Scribd

0 notas0% acharam este documento útil (0 voto)

66 visualizações11 páginasInsurance Cases 1

Enviado por

Leogen Tomulto1st batch of cases

Direitos autorais:

© All Rights Reserved

Formatos disponíveis

Baixe no formato DOCX, PDF, TXT ou leia online no Scribd

Você está na página 1de 11

1.

Loadmasters VS Glodel Brokerage

MENDOZA, J .:

This is a petition for review on certiorari under Rule 45 of the Revised Rules of Court assailing the August 24, 2007 Decision

[1]

of

the Court of Appeals (CA) in CA-G.R. CV No. 82822, entitled R&B Insurance Corporation v. Glodel Brokerage Corporation and

Loadmasters Customs Services, Inc., which held petitioner Loadmasters Customs Services, Inc. (Loadmasters) liable to respondent

Glodel Brokerage Corporation (Glodel) in the amount of P1,896,789.62 representing the insurance indemnity which R&B Insurance

Corporation (R&B Insurance) paid to the insured-consignee, Columbia Wire and Cable Corporation (Columbia).

THE FACTS:

On August 28, 2001, R&B Insurance issued Marine Policy No. MN-00105/2001 in favor of Columbia to insure the shipment of

132 bundles of electric copper cathodes against All Risks. On August 28, 2001, the cargoes were shipped on board the vessel

Richard Rey from Isabela, Leyte, to Pier 10, North Harbor, Manila. They arrived on the same date.

Columbia engaged the services of Glodel for the release and withdrawal of the cargoes from the pier and the subsequent

delivery to its warehouses/plants. Glodel, in turn, engaged the services of Loadmasters for the use of its delivery trucks to transport the

cargoes to Columbias warehouses/plants in Bulacan and Valenzuela City.

The goods were loaded on board twelve (12) trucks owned by Loadmasters, driven by its employed drivers and accompanied

by its employed truck helpers. Six (6) truckloads of copper cathodes were to be delivered to Balagtas, Bulacan, while the other six (6)

truckloads were destined for Lawang Bato, Valenzuela City. The cargoes in six truckloads for Lawang Bato were duly delivered

in Columbias warehouses there. Of the six (6) trucks en route to Balagtas, Bulacan, however, only five (5) reached the

destination. One (1) truck, loaded with 11 bundles or 232 pieces of copper cathodes, failed to deliver its cargo.

Later on, the said truck, an Isuzu with Plate No. NSD-117, was recovered but without the copper cathodes. Because of this

incident, Columbia filed with R&B Insurance a claim for insurance indemnity in the amount of P1,903,335.39. After the requisite

investigation and adjustment, R&B Insurance paid Columbia the amount of P1,896,789.62 as insurance indemnity.

R&B Insurance, thereafter, filed a complaint for damages against both Loadmasters and Glodel before the Regional Trial

Court, Branch 14, Manila (RTC), docketed as Civil Case No. 02-103040. It sought reimbursement of the amount it had paid

to Columbia for the loss of the subject cargo. It claimed that it had been subrogated to the right of the consignee to recover from the

party/parties who may be held legally liable for the loss.

[2]

On November 19, 2003, the RTC rendered a decision

[3]

holding Glodel liable for damages for the loss of the subject cargo and

dismissing Loadmasters counterclaim for damages and attorneys fees against R&B Insurance. The dispositive portion of the decision

reads:

WHEREFORE, all premises considered, the plaintiff having established by preponderance of evidence its

claims against defendant Glodel Brokerage Corporation, judgment is hereby rendered ordering the latter:

1. To pay plaintiff R&B Insurance Corporation the sum of P1,896,789.62 as actual and

compensatory damages, with interest from the date of complaint until fully paid;

2. To pay plaintiff R&B Insurance Corporation the amount equivalent to 10% of the principal

amount recovered as and for attorneys fees plus P1,500.00 per appearance in Court;

3. To pay plaintiff R&B Insurance Corporation the sum of P22,427.18 as litigation expenses.

WHEREAS, the defendant Loadmasters Customs Services, Inc.s counterclaim for damages and attorneys

fees against plaintiff are hereby dismissed.

With costs against defendant Glodel Brokerage Corporation.

SO ORDERED.

[4]

Both R&B Insurance and Glodel appealed the RTC decision to the CA.

On August 24, 2007, the CA rendered the assailed decision which reads in part:

Considering that appellee is an agent of appellant Glodel, whatever liability the latter owes to appellant R&B

Insurance Corporation as insurance indemnity must likewise be the amount it shall be paid by appellee Loadmasters.

WHEREFORE, the foregoing considered, the appeal is PARTLY GRANTED in that the appellee

Loadmasters is likewise held liable to appellant Glodel in the amount ofP1,896,789.62 representing the insurance

indemnity appellant Glodel has been held liable to appellant R&B Insurance Corporation.

Appellant Glodels appeal to absolve it from any liability is herein DISMISSED.

SO ORDERED.

[5]

Hence, Loadmasters filed the present petition for review on certiorari before this Court presenting the following

ISSUES

1. Can Petitioner Loadmasters be held liable to Respondent Glodel in spite of the fact that the latter

respondent Glodel did not file a cross-claim against it (Loadmasters)?

2. Under the set of facts established and undisputed in the case, can petitioner Loadmasters be legally

considered as an Agent of respondent Glodel?

[6]

To totally exculpate itself from responsibility for the lost goods, Loadmasters argues that it cannot be considered an agent of

Glodel because it never represented the latter in its dealings with the consignee. At any rate, it further contends that Glodel has no

recourse against it for its (Glodels) failure to file a cross-claim pursuant to Section 2, Rule 9 of the 1997 Rules of Civil Procedure.

Glodel, in its Comment,

[7]

counters that Loadmasters is liable to it under its cross-claim because the latter was grossly negligent

in the transportation of the subject cargo. With respect to Loadmasters claim that it is already estopped from filing a cross-claim, Glodel

insists that it can still do so even for the first time on appeal because there is no rule that provides otherwise. Finally, Glodel argues

that its relationship with Loadmasters is that of Charter wherein the transporter (Loadmasters) is only hired for the specifi c job of

delivering the merchandise. Thus, the diligence required in this case is merely ordinary diligence or that of a good father of the family,

not the extraordinary diligence required of common carriers.

R&B Insurance, for its part, claims that Glodel is deemed to have interposed a cross-claim against Loadmasters because it was

not prevented from presenting evidence to prove its position even without amending its Answer. As to the relationship between

Loadmasters and Glodel, it contends that a contract of agency existed between the two corporations.

[8]

Subrogation is the substitution of one person in the place of another with reference to a lawful claim or right, so that he who is

substituted succeeds to the rights of the other in relation to a debt or claim, including its remedies or securities.

[9]

Doubtless, R&B

Insurance is subrogated to the rights of the insured to the extent of the amount it paid the consignee under the marine insurance, as

provided under Article 2207 of the Civil Code, which reads:

ART. 2207. If the plaintiffs property has been insured, and he has received indemnity from the insurance

company for the injury or loss arising out of the wrong or breach of contract complained of, the insurance company

shall be subrogated to the rights of the insured against the wrong-doer or the person who has violated the contract. If

the amount paid by the insurance company does not fully cover the injury or loss, the aggrieved party shall be entitled

to recover the deficiency from the person causing the loss or injury.

As subrogee of the rights and interest of the consignee, R&B Insurance has the right to seek reimbursement from either

Loadmasters or Glodel or both for breach of contract and/or tort.

The issue now is who, between Glodel and Loadmasters, is liable to pay R&B Insurance for the amount of the indemnity it paid

Columbia.

At the outset, it is well to resolve the issue of whether Loadmasters and Glodel are common carriers to determine their liability for

the loss of the subject cargo. Under Article 1732 of the Civil Code, common carriers are persons, corporations, firms, or associations

engaged in the business of carrying or transporting passenger or goods, or both by land, water or air for compensation, offering their

services to the public.

Based on the aforecited definition, Loadmasters is a common carrier because it is engaged in the business of transporting

goods by land, through its trucking service. It is acommon carrier as distinguished from a private carrier wherein the carriage is

generally undertaken by special agreement and it does not hold itself out to carry goods for the general public.

[10]

The distinction is

significant in the sense that the rights and obligations of the parties to a contract of private carriage are governed principally by their

stipulations, not by the law on common carriers.

[11]

In the present case, there is no indication that the undertaking in the contract between Loadmasters and Glodel was private in

character. There is no showing that Loadmasters solely and exclusively rendered services to Glodel.

In fact, Loadmasters admitted that it is a common carrier.

[12]

In the same vein, Glodel is also considered a common carrier within the context of Article 1732. In its Memorandum,

[13]

it

states that it is a corporation duly organized and existing under the laws of the Republic of the Philippines and is engaged in the

business of customs brokering. It cannot be considered otherwise because as held by this Court in Schmitz Transport & Brokerage

Corporation v. Transport Venture, Inc.,

[14]

a customs broker is also regarded as a common carrier, the transportation of goods being an

integral part of its business.

Loadmasters and Glodel, being both common carriers, are mandated from the nature of their business and for reasons of

public policy, to observe the extraordinary diligence in the vigilance over the goods transported by them according to all the

circumstances of such case, as required by Article 1733 of the Civil Code. When the Court speaks of extraordinary diligence, it is that

extreme measure of care and caution which persons of unusual prudence and circumspection observe for securing and preserving their

own property or rights.

[15]

This exacting standard imposed on common carriers in a contract of carriage of goods is intended to tilt the

scales in favor of the shipper who is at the mercy of the common carrier once the goods have been lodged for shipment.

[16]

Thus, in

case of loss of the goods, the common carrier is presumed to have been at fault or to have acted negligently.

[17]

This presumption of

fault or negligence, however, may be rebutted by proof that the common carrier has observed extraordinary diligence over the goods.

With respect to the time frame of this extraordinary responsibility, the Civil Code provides that the exercise of extraordinary

diligence lasts from the time the goods are unconditionally placed in the possession of, and received by, the carrier for transportation

until the same are delivered, actually or constructively, by the carrier to the consignee, or to the person who has a right t o receive

them.

[18]

Premises considered, the Court is of the view that both Loadmasters and Glodel are jointly and severally liable to R & B

Insurance for the loss of the subject cargo. Under Article 2194 of the New Civil Code, the responsibility of two or more persons who

are liable for a quasi-delict is solidary.

Loadmasters claim that it was never privy to the contract entered into by Glodel with the consignee Columbia or R&B

Insurance as subrogee, is not a valid defense. It may not have a direct contractual relation with Columbia, but it is liable for tort under

the provisions of Article 2176 of the Civil Code on quasi-delicts which expressly provide:

ART. 2176. Whoever by act or omission causes damage to another, there being fault or negligence, is

obliged to pay for the damage done. Such fault or negligence, if there is no pre-existing contractual relation between

the parties, is called a quasi-delict and is governed by the provisions of this Chapter.

Pertinent is the ruling enunciated in the case of Mindanao Terminal and Brokerage Service, Inc. v. Phoenix Assurance

Company of New York,/McGee & Co., Inc.

[19]

where this Court held that a tort may arise despite the absence of a contractual

relationship, to wit:

We agree with the Court of Appeals that the complaint filed by Phoenix and McGee against Mindanao

Terminal, from which the present case has arisen, states a cause of action. The present action is based on quasi-

delict, arising from the negligent and careless loading and stowing of the cargoes belonging to Del Monte Produce.

Even assuming that both Phoenix and McGee have only been subrogated in the rights of Del Monte Produce, who is

not a party to the contract of service between Mindanao Terminal and Del Monte, still the insurance carriers may

have a cause of action in light of the Courts consistent ruling that the act that breaks the contract may be also a

tort. In fine, a liability for tort may arise even under a contract, where tort is that which breaches the contract. In the

present case, Phoenix and McGee are not suing for damages for injuries arising from the breach of the

contract of service but from the alleged negligent manner by which Mindanao Terminal handled the cargoes

belonging to Del Monte Produce. Despite the absence of contractual relationship between Del Monte Produce and

Mindanao Terminal, the allegation of negligence on the part of the defendant should be sufficient to establish a cause

of action arising from quasi-delict. [Emphases supplied]

In connection therewith, Article 2180 provides:

ART. 2180. The obligation imposed by Article 2176 is demandable not only for ones own acts or omissions,

but also for those of persons for whom one is responsible.

x x x x

Employers shall be liable for the damages caused by their employees and household helpers acting within

the scope of their assigned tasks, even though the former are not engaged in any business or industry.

It is not disputed that the subject cargo was lost while in the custody of Loadmasters whose employees (truck driver and

helper) were instrumental in the hijacking or robbery of the shipment. As employer, Loadmasters should be made answerable for the

damages caused by its employees who acted within the scope of their assigned task of delivering the goods safely to the warehouse.

Whenever an employees negligence causes damage or injury to another, there instantly arises a presumption juris

tantum that the employer failed to exercise diligentissimi patris families in the selection (culpa in eligiendo) or supervision (culpa in

vigilando) of its employees.

[20]

To avoid liability for a quasi-delict committed by its employee, an employer must overcome the

presumption by presenting convincing proof that he exercised the care and diligence of a good father of a family in the selection and

supervision of his employee.

[21]

In this regard, Loadmasters failed.

Glodel is also liable because of its failure to exercise extraordinary diligence. It failed to ensure that Loadmasters would fully

comply with the undertaking to safely transport the subject cargo to the designated destination. It should have been more prudent in

entrusting the goods to Loadmasters by taking precautionary measures, such as providing escorts to accompany the trucks in

delivering the cargoes. Glodel should, therefore, be held liable with Loadmasters. Its defense of force majeure is unavailing.

At this juncture, the Court clarifies that there exists no principal-agent relationship between Glodel and Loadmasters, as

erroneously found by the CA. Article 1868 of the Civil Code provides: By the contract of agency a person binds himself to render some

service or to do something in representation or on behalf of another, with the consent or authority of the latter. The elements of a

contract of agency are: (1) consent, express or implied, of the parties to establish the relationship; (2) the object is the execution of a

juridical act in relation to a third person; (3) the agent acts as a representative and not for himself; (4) the agent acts within t he scope of

his authority.

[22]

Accordingly, there can be no contract of agency between the parties. Loadmasters never represented Glodel. Neither was it

ever authorized to make such representation. It is a settled rule that the basis for agency is representation, that is, the agent acts for

and on behalf of the principal on matters within the scope of his authority and said acts have the same legal effect as if they were

personally executed by the principal. On the part of the principal, there must be an actual intention to appoint or an intention naturally

inferable from his words or actions, while on the part of the agent, there must be an intention to accept the appointment and act on

it.

[23]

Such mutual intent is not obtaining in this case.

What then is the extent of the respective liabilities of Loadmasters and Glodel? Each wrongdoer is liable for the total damage

suffered by R&B Insurance. Where there are several causes for the resulting damages, a party is not relieved from liability, even

partially. It is sufficient that the negligence of a party is an efficient cause without which the damage would not have resulted. It is no

defense to one of the concurrent tortfeasors that the damage would not have resulted from his negligence alone, without the negligence

or wrongful acts of the other concurrent tortfeasor. As stated in the case of Far Eastern Shipping v. Court of Appeals,

[24]

X x x. Where several causes producing an injury are concurrent and each is an efficient cause without which

the injury would not have happened, the injury may be attributed to all or any of the causes and recovery may be had

against any or all of the responsible persons although under the circumstances of the case, it may appear that one of

them was more culpable, and that the duty owed by them to the injured person was not the same. No actor's

negligence ceases to be a proximate cause merely because it does not exceed the negligence of other actors. Each

wrongdoer is responsible for the entire result and is liable as though his acts were the sole cause of the injury.

There is no contribution between joint tortfeasors whose liability is solidary since both of them are liable for

the total damage. Where the concurrent or successive negligent acts or omissions of two or more persons, although

acting independently, are in combination the direct and proximate cause of a single injury to a third person, it is

impossible to determine in what proportion each contributed to the injury and either of them is responsible for the

whole injury. Where their concurring negligence resulted in injury or damage to a third party, they become joint

tortfeasors and are solidarily liable for the resulting damage under Article 2194 of the Civil Code. [Emphasis supplied]

The Court now resolves the issue of whether Glodel can collect from Loadmasters, it having failed to file a cross-claim against

the latter.

Undoubtedly, Glodel has a definite cause of action against Loadmasters for breach of contract of service as the latter is

primarily liable for the loss of the subject cargo. In this case, however, it cannot succeed in seeking judicial sanction against

Loadmasters because the records disclose that it did not properly interpose a cross-claim against the latter. Glodel did not even pray

that Loadmasters be liable for any and all claims that it may be adjudged liable in favor of R&B Insurance. Under the Rules, a

compulsory counterclaim, or a cross-claim, not set up shall be barred.

[25]

Thus, a cross-claim cannot be set up for the first time on

appeal.

For the consequence, Glodel has no one to blame but itself. The Court cannot come to its aid on equitable

grounds. Equity, which has been aptly described as a justice outside legality, is applied only in the absence of, and never against,

statutory law or judicial rules of procedure.

[26]

The Court cannot be a lawyer and take the cudgels for a party who has been at fault or

negligent.

WHEREFORE, the petition is PARTIALLY GRANTED. The August 24, 2007 Decision of the Court of Appeals

is MODIFIED to read as follows:

WHEREFORE, judgment is rendered declaring petitioner Loadmasters Customs Services, Inc. and

respondent Glodel Brokerage Corporation jointly and severally liable to respondent R&B Insurance Corporation for

the insurance indemnity it paid to consignee Columbia Wire & Cable Corporation and ordering both parties to pay,

jointly and severally, R&B Insurance Corporation a] the amount of P1,896,789.62 representing the insurance

indemnity; b] the amount equivalent to ten (10%) percent thereof for attorneys fees; and c] the amount of P22,427.18

for litigation expenses.

The cross-claim belatedly prayed for by respondent Glodel Brokerage Corporation against petitioner

Loadmasters Customs Services, Inc. is DENIED.

SO ORDERED

2. Danzas Corporation VS Abrogar

CORONA, J .:

Petitioner Danzas Corporation, through its agent, petitioner All Transport Network brings to us this petition for review on

certiorari

[1]

questioning the decision

[2]

and resolution

[3]

of the Court of Appeals which affirmed two orders issued by the Regional Trial

Court, Makati City, Branch 150.

[4]

The facts of the case follow.

[5]

On February 22, 1994, petitioner Danzas took a shipment of nine packages of ICS watches for transport to Manila. The

consignee, International Freeport Traders, Inc. (IFTI) secured Marine Risk Note No. 0000342 from private respondent Seaboard.

On March 2, 1994, the Korean Airlines plane carrying the goods arrived in Manila and discharged the goods to the custody of

private respondent Philippine Skylanders, Inc. for safekeeping. On withdrawal of the shipment from private respondent Skylanders

warehouse, IFTI noted that one package containing 475 watches was shortlanded while the remaining eight were found to have

sustained tears on sides and the retape of flaps. On further examination and inventory of the cartons, it was discovered that 176 Guess

watches were missing. Private respondent Seaboard, as insurer, paid the losses to IFTI.

On February 23, 1995, Seaboard, invoking its right of subrogation, filed a complaint against Skylanders, petitioner and its

authorized representative, petitioner All Transport Network, Inc. (ATN), praying for actual damages in the amount of P612,904.97 plus

legal interest, attorneys fees and cost of suit. Petitioners impleaded Korean Airlines (KAL) as third-party defendant.

While the case was pending, IFTIs treasurer, Mary Eileen Gozon accepted the proposal of KAL to settle consignees claim by

paying the amount of US $522.20. On May 8, 1996, Felipe Acebedo, IFTIs representative received a check from KAL and

correspondingly signed a release form.

On July 2, 1996, petitioners filed a motion to dismiss the case on the ground that private respondent Seaboards demand had

been paid or otherwise extinguished by KAL.

On December 9, 1996, the trial court issued an order denying the motion to dismiss. Petitioners, private respondent

Skylanders and KAL filed separate motions for reconsideration. Prior to the resolution of these motions, the trial court allowed private

respondent Skylanders to present evidence in a preliminary hearing on November 14, 1997, after which the court set a date to hear the

presentation of rebuttal evidence.

On December 5, 1997, petitioners filed a manifestation and motion for reconsideration of the order of the trial court dated

November 14, 1997, questioning the propriety of the preliminary hearing.

On February 18, 1998, the trial court issued an order denying: (1) the motion for reconsideration of the December 9, 1996

order filed by petitioners, private respondent Skylanders and KAL; (2) the motion to dismiss filed by Skylanders and (3) petitioners

motion for reconsideration of the November 14, 1997 order.

On April 6, 1998, petitioners filed in the Court of Appeals a special civil action for certiorari under Rule 65 of the Rules of

Court. On March 5, 1999, the CA dismissed the petition.

[6]

Petitioners filed

[7]

a motion for reconsideration but this was denied.

[8]

Hence, this petition.

Petitioners principal contention is that private respondents right of subrogation was extinguished when IFTI received payment

from KAL in settlement of its obligation. They also claim that public respondent committed grave abuse of discretion by refusing to

dismiss the case on that ground. Finally, they claim that, by granting private respondent Skylanders a preliminary hearing on an

affirmative defense other than one of the grounds stated in Section 1, Rule 16 of the 1997 Rules of Civil Procedure, public

respondent committed another grave abuse of discretion.

For its part, private respondent Seaboard argues that the payment made by the tortfeasor did not relieve it of liability because

at the time of payment, its (Seaboards) suit against petitioners was already ongoing. It also insists that because the assailed order was

interlocutory, it was not a proper subject for certiorari.

[9]

Private respondent Skylanders likewise contends that the order denying dismissal cannot be the subject of certiorari in the

absence of grave abuse of discretion. It also defends the trial courts order granting a preliminary hearing, saying that, assuming the

trial court had erroneously granted such a hearing, such error was merely one of judgment and not of jurisdiction as to merit

certiorari.

[10]

The petition has no merit.

It is true that the doctrine in Manila Mahogany Manufacturing Corporation v. Court of Appeals

[11]

remains the controlling

doctrine on the issue of whether the tortfeasor, by settling with the insured, defeats the right to subrogation of the insurer. According

to Manila Mahogany:

Since the insurer can be subrogated to only such rights as the insured may have, should the insured, after

receiving payment from the insurer, release the wrongdoer who caused the loss, the insurer loses his rights against

the latter. But in such a case, the insurer will be entitled to recover from the insured whatever it has paid to the latter,

unless the release was made with the consent of the insurer.

This is buttressed by a later decision, Pan Malayan Insurance Corporation v. Court of Appeals,

[12]

in which we cited a number

of exceptions to the rule laid down in Article 2207 of the Civil Code.

[13]

Under the first of these exceptions, if the assured by his own act

releases the wrongdoer or third party liable for the loss or damage from liability, the insurers right of subrogation is defeated.

However, certain factual differences pointed out by private respondent Seaboard render this doctrine inapplicable. In Manila

Mahogany, the tortfeasor San Miguel Corporation paid the insured without knowing that the insurer had already made such payment.

KAL was not similarly situated, being fully aware of the prior payment made by the insurer to the consignee. Private respondent

Seaboard asserts that, being in bad faith, KAL should bear the consequences of its actions.

[14]

While Manila Mahogany is silent on whether the existence of good faith or bad faith on the tortfeasors part affects the insurers

right of subrogation, there exists a wealth of U.S. jurisprudence holding that whenever the wrongdoer settles with the insured without

the consent of the insurer and with knowledge of the insurers payment and right of subrogation, such right is not defeated by the

settlement.

[15]

Because this doctrine is actually consistent with the facts of Mahogany and helps fill a slight gap left by our ruling in that

case, we adopt it now. The trial court correctly refused to dismiss the case. In that respect, therefore, the trial court did not commit

grave abuse of discretion which would justify certiorari.

We likewise find that no grave abuse of discretion was committed by public respondent when it granted private respondent

Skylanders motion for a preliminary hearing.

In California and Hawaiian Sugar Company v. Pioneer Insurance and Surety Corporation,

[16]

we held that a preliminary hearing

was not mandatory but was rather subject to the discretion of the trial court. We found in that instance that the trial court had committed

grave abuse of discretion in refusing the partys motion for a preliminary hearing on the ground that the case was premature, not having

been submitted for arbitration. A preliminary hearing could have settled the entire case, thereby helping decongest the dockets. It was

therefore the refusal to allow the most efficient and expeditious process which we condemned.

In the instant case, we are not convinced that public respondents act of allowing a preliminary hearing constituted grave abuse of

discretion.

In Land Bank of the Philippines v. the Court of Appeals

[17]

we discussed the meaning of grave abuse of discretion:

Grave abuse of discretion implies such capricious and whimsical exercise of judgment as is equivalent to lack of

jurisdiction or, in other words, where the power is exercised in an arbitrary manner by reason of passion, prejudice, or

personal hostility, and it must be so patent or gross as to amount to an evasion of a positive duty or to a virtual refusal

to perform the duty enjoined or to act at all in contemplation of law.

The special civil action for certiorari is a remedy designed for the correction of errors of jurisdiction

and not errors of judgment. The raison detre for the rule is when a court exercises its jurisdiction, an error

committed while so engaged does not deprive it of the jurisdiction being exercised when the error is committed. If it

did, every error committed by a court would deprive it of its jurisdiction and every erroneous judgment would be a void

judgment. In such a scenario, the administration of justice would not survive. Hence, where the issue or question

involved affects the wisdom or legal soundness of the decisionnot the jurisdiction of the court to render

said decisionthe same is beyond the province of a special civil action for certiorari. (emphasis supplied)

Public respondents order granting the preliminary hearing does not at all fit the description above. At worst, it was an error in

judgment which is beyond the domain of certiorari.

WHEREFORE, in view of the foregoing, the petition is hereby DENIED. The decision and resolution of the Court of Appeals

areAFFIRMED.

Costs against petitioners.

SO ORDERED.

3. Vector Shipping VS American Home Assurance

BERSAMIN, J .:

Subrogation under Article 2207 of the Civil Code gives rise to a cause of action created by law. For purposes of the law on the

prescription of actions, the period of limitation is ten years.

The Case

Vector Shipping Corporation (Vector) and Francisco Soriano appeal the decision promulgated on July 22, 2003,

1

whereby the Court of

Appeals (CA) held them jointly and severally liable to pay P7,455,421.08 to American Home Assurance Company (respondent) as and

by way of actual damages on the basis of respondent being the subrogee of its insured Caltex Philippines, Inc. (Caltex).

Antecedents

Vector was the operator of the motor tanker M/T Vector, while Soriano was the registered owner of the M/T Vector. Respondent is a

domestic insurance corporation.

2

On September 30, 1987, Caltex entered into a contract of affreightment

3

with Vector for the transport of Caltexs petroleum cargo

through the M/T Vector. Caltex insured the petroleum cargo with respondent for P7,455,421.08 under Marine Open Policy No. 34-5093-

6.

4

In the evening of December 20, 1987, the M/T Vector and the M/V Doa Paz, the latter a vessel owned and operated by Sulpicio

Lines, Inc., collided in the open sea near Dumali Point in Tablas Strait, located between the Provinces of Marinduque and Ori ental

Mindoro. The collision led to the sinking of both vessels. The entire petroleum cargo of Caltex on board the M/T Vector perished.

5

On

July 12, 1988, respondent indemnified Caltex for the loss of the petroleum cargo in the full amount of P7,455,421.08.

6

On March 5, 1992, respondent filed a complaint against Vector, Soriano, and Sulpicio Lines, Inc. to recover the full amount of

P7,455,421.08 it paid to Caltex (Civil Case No. 92-620).

7

The case was raffled to Branch 145 of the Regional Trial Court (RTC) in

Makati City.

On December 10, 1997, the RTC issued a resolution dismissing Civil Case No. 92-620 on the following grounds:cralavvonlinelawlibrary

This action is upon a quasi-delict and as such must be commenced within four

4

years from the day they may be brought. [Art. 1145 in

relation to Art. 1150, Civil Code] From the day [the action] may be brought means from the day the quasi-delict occurred. [Capuno v.

Pepsi Cola, 13 SCRA 663]

The tort complained of in this case occurred on 20 December 1987. The action arising therefrom would under the law prescribe, unless

interrupted, on 20 December 1991.

When the case was filed against defendants Vector Shipping and Francisco Soriano on 5 March 1992, the action not having been

interrupted, had already prescribed.

Under the same situation, the cross-claim of Sulpicio Lines against Vector Shipping and Francisco Soriano filed on 25 June 1992 had

likewise prescribed.

The letter of demand upon defendant Sulpicio Lines allegedly on 6 November 1991 did not interrupt the [tolling] of the prescriptive

period since there is no evidence that it was actually received by the addressee. Under such circumstances, the action against Sulpicio

Lines had likewise prescribed.

Even assuming that such written extra-judicial demand was received and the prescriptive period interrupted in accordance with Art.

1155, Civil Code, it was only for the 10-day period within which Sulpicio Lines was required to settle its obligation. After that period

lapsed, the prescriptive period started again. A new 4-year period to file action was not created by the extra-judicial demand; it merely

suspended and extended the period for 10 days, which in this case meant that the action should be commenced by 30 December 1991,

rather than 20 December 1991.

Thus, when the complaint against Sulpicio Lines was filed on 5 March 1992, the action had prescribed.

PREMISES CONSIDERED, the complaint of American Home Assurance Company and the cross-claim of Sulpicio Lines against Vector

Shipping Corporation and Francisco Soriano are DISMISSED.

Without costs.

SO ORDERED.

8

Respondent appealed to the CA, which promulgated its assailed decision on July 22, 2003 reversing the RTC.

9

Although thereby

absolving Sulpicio Lines, Inc. of any liability to respondent, the CA held Vector and Soriano jointly and severally liable to respondent for

the reimbursement of the amount of P7,455,421.08 paid to Caltex, explaining:cralavvonlinelawlibrary

x x x x

The resolution of this case is primarily anchored on the determination of what kind of relationship existed between Caltex and M/V Dona

Paz and between Caltex and M/T Vector for purposes of applying the laws on prescription. The Civil Code expressly provides for the

number of years before the extinctive prescription s[e]ts in depending on the relationship that governs the parties.

x x x x

After a careful perusal of the factual milieu and the evidence adduced by the parties, We are constrained to rule that the relationship

that

existed between Caltex and M/V Dona Paz is that of a quasi-delict while that between Caltex and M/T Vector is culpa

contractual based on a Contract of Affreightment or a charter party.

x x x x

On the other hand, the claim of appellant against M/T Vector is anchored on a breach of contract of affreightment. The appellant

averred that M/T Vector committed such act for having misrepresented to the appellant that said vessel is seaworthy when in fact it is

not. The contract was executed between Caltex and M/T Vector on September 30, 1987 for the latter to transport thousands of barrels

of different petroleum products. UnderArticle 1144 of the New Civil Code, actions based on written contract must be brought within 10

years from the time the right of action accrued. A passenger of a ship, or his heirs, can bring an action based on culpa contractual

within a period of 10 years because the ticket issued for the transportation is by itself a complete written contract (Peralta de Guerrero

vs. Madrigal Shipping Co., L 12951, November 17, 1959). Viewed with reference to the statute of limitations, an action against a

carrier, whether of goods or of passengers, for injury resulting from a breach of contract for safe carriage is one on contract, and not in

tort, and is therefore, in the absence of a specific statute relating to such actions governed by the statute fixing the peri od within which

actions for breach of contract must be brought (53 C.J .S. 1002 citing Southern Pac. R. Co. of Mexico vs. Gonzales 61 P. 2d 377, 48

Ariz. 260, 106 A.L.R. 1012).

Considering that We have already concluded that the prescriptive periods for filing action against M/V Doa Paz based on quasi delict

and M/T Vector based on breach of contract have not yet expired, are We in a position to decide the appeal on its merit.

We say yes.

x x x x

Article 2207 of the Civil Code on subrogation is explicit that if the plaintiffs property has been insured, and he has received indemnity

from the insurance company for the injury or loss arising out of the wrong or breach of contract complained of, the insurance company

should be subrogated to the rights of the insured against the wrongdoer or the person who has violated the contract. Undoubtedly, the

herein appellant has the rights of a subrogee to recover from M/T Vector what it has paid by way of indemnity to Caltex.

WHEREFORE, foregoing premises considered, the decision dated December 10, 1997 of the RTC of Makati City, Branch 145 is hereby

REVERSED. Accordingly, the defendant-appellees Vector Shipping Corporation and Francisco Soriano are held jointly and severally

liable to the plaintiff-appellant American Home Assurance Company for the payment of P7,455,421.08 as and by way of actual

damages.

SO ORDERED.

10

Respondent sought the partial reconsideration of the decision of the CA, contending that Sulpicio Lines, Inc. should also be held jointly

liable with Vector and Soriano for the actual damages awarded.

11

On their part, however, Vector and Soriano immediately appealed to

the Court on September 12, 2003.

12

Thus, on October 1, 2003, the CA held in abeyance its action on respondents partial motion for

reconsideration pursuant to its internal rules until the Court has resolved this appeal.

13

Issues

The main issue is whether this action of respondent was already barred by prescription for bringing it only on March 5, 1992. A related

issue concerns the proper determination of the nature of the cause of action as arising either from a quasi-delict or a breach of contract.

The Court will not pass upon whether or not Sulpicio Lines, Inc. should also be held jointly liable with Vector and Soriano for the actual

damages claimed.

Ruling

The petition lacks merit.

Vector and Soriano posit that the RTC correctly dismissed respondents complaint on the ground of prescription. They insist that this

action was premised on a quasi-delict or upon an injury to the rights of the plaintiff, which, pursuant to Article 1146 of the Civil Code,

must be instituted within four years from the time the cause of action accrued; that because respondents cause of action accrued on

December 20, 1987, the date of the collision, respondent had only four years, or until December 20, 1991, within which to bring its

action, but its complaint was filed only on March 5, 1992, thereby rendering its action already barred for being commenced beyond the

four-year prescriptive period;

14

and that there was no showing that respondent had made extrajudicial written demands upon them for

the reimbursement of the insurance proceeds as to interrupt the running of the prescriptive period.

15

We concur with the CAs ruling that respondents action did not yet prescribe. The legal provision governing this case was not Article

1146 of the Civil Code,

16

but Article 1144 of the Civil Code, which states:cralavvonlinelawlibrary

Article 1144. The following actions must be brought within ten years from the time the cause of action accrues:cralavvonlinelawlibrary

(1) Upon a written contract;chanroblesvirtualawlibrary

(2) Upon an obligation created by law;chanroblesvirtualawlibrary

(3) Upon a judgment.

We need to clarify, however, that we cannot adopt the CAs characterization of the cause of action as based on the contract of

affreightment between Caltex and Vector, with the breach of contract being the failure of Vector to make the M/T Vector seaworthy, as

to make this action come under Article 1144 (1), supra. Instead, we find and hold that that the present action was not upon a written

contract, but upon an obligation created by law. Hence, it came under Article 1144 (2) of the Civil Code. This is because the

subrogation of respondent to the rights of Caltex as the insured was by virtue of the express provision of law embodied in Article 2207

of the Civil Code, to wit:cralavvonlinelawlibrary

Article 2207. If the plaintiffs property has been insured, and he has received indemnity from the insurance company for the injury or

loss arising out of the wrong or breach of contract complained of, the insurance company shall be subrogated to the rights of the

insured against the wrongdoer or the person who has violated the contract. If the amount paid by the insurance company does

not fully cover the injury or loss, the aggrieved party shall be entitled to recover the deficiency from the person causing the loss or

injury. (Emphasis supplied)

The juridical situation arising under Article 2207 of the Civil Code is well explained in Pan Malayan Insurance Corporation v. Court of

Appeals,

17

as follows:cralavvonlinelawlibrary

Article 2207 of the Civil Code is founded on the well-settled principle of subrogation. If the insured property is destroyed or damaged

through the fault or negligence of a party other than the assured, then the insurer, upon payment to the assured, will be subrogated to

the rights of the assured to recover from the wrongdoer to the extent that the insurer has been obligated to pay. Payment by the

insurer to the assured operates as an equitable assignment to the former of all remedies which the latter may have against

the third party whose negligence or wrongful act caused the loss. The right of subrogation is not dependent upon, nor does it

grow out of, any privity of contract or upon written assignment of claim. It accrues simply upon payment of the insurance

claim by the insurer[Compania Maritima v. Insurance Company of North America, G.R. No. L-18965, October 30, 1964, 12 SCRA

213; Firemans Fund Insurance Company v. Jamilla & Company, Inc., G.R. No. L-27427, April 7, 1976, 70 SCRA 323].

18

Verily, the contract of affreightment that Caltex and Vector entered into did not give rise to the legal obligation of Vector and Soriano to

pay the demand for reimbursement by respondent because it concerned only the agreement for the transport of Caltexs petroleum

cargo. As the Court has aptly put it in Pan Malayan Insurance Corporation v. Court of Appeals, supra, respondents right of subrogation

pursuant to Article 2207, supra, was not dependent upon, nor d[id] it grow out of, any privity of contract or upon written assignment of

claim [but] accrue[d] simply upon payment of the insurance claim by the insurer.

Considering that the cause of action accrued as of the time respondent actually indemnified Caltex in the amount of P7,455,421.08 on

July 12, 1988,

19

the action was not yet barred by the time of the filing of its complaint on March 5, 1992,

20

which was well within the 10-

year period prescribed by Article 1144 of the Civil Code.

The insistence by Vector and Soriano that the running of the prescriptive period was not interrupted because of the failure of

respondent to serve any extrajudicial demand was rendered inconsequential by our foregoing finding that respondents cause of action

was not based on a quasi-delict that prescribed in four years from the date of the collision on December 20, 1987, as the RTC

misappreciated, but on an obligation created by law, for which the law fixed a longer prescriptive period of ten years from the accrual of

the action.

Still, Vector and Soriano assert that respondent had no right of subrogation to begin with, because the complaint did not all ege that

respondent had actually paid Caltex for the loss of the cargo. They further assert that the subrogation receipt submitted by respondent

was inadmissible for not being properly identified by Ricardo C. Ongpauco, respondents witness, who, although supposed to identify

the subrogation receipt based on his affidavit, was not called to testify in court; and that respondent presented only one witness in the

person of Teresita Espiritu, who identified Marine Open Policy No. 34-5093-6 issued by respondent to Caltex.

21

We disagree with petitioners assertions. It is undeniable that respondent preponderantly established its right of subrogation. Its Exhibit

C was Marine Open Policy No. 34-5093-6 that it had issued to Caltex to insure the petroleum cargo against marine peril.

22

Its Exhibit D

was the formal written claim of Caltex for the payment of the insurance coverage of P7,455,421.08 coursed through respondents

adjuster.

23

Its Exhibits E to H were marine documents relating to the perished cargo on board the M/V Vector that were processed for

the purpose of verifying the insurance claim of Caltex.

24

Its Exhibit I was the subrogation receipt dated July 12, 1988 showing that

respondent paid Caltex P7,455,421.00 as the full settlement of Caltexs claim under Marine Open Policy No. 34-5093-6.

25

All these

exhibits were unquestionably duly presented, marked, and admitted during the trial.

26

Specifically, Exhibit C was admitted as an

authentic copy of Marine Open Policy No. 34-5093-6, while Exhibits D, E, F, G, H and I, inclusive, were admitted as parts of the

testimony of respondents witness Efren Villanueva, the manager for the adjustment service of the Manila Adjusters and Surveyors

Company.

27

Consistent with the pertinent law and jurisprudence, therefore, Exhibit I was already enough by itself to prove the payment of

P7,455,421.00 as the full settlement of Caltexs claim.

28

The payment made to Caltex as the insured being thereby duly documented,

respondent became subrogated as a matter of course pursuant to Article 2207 of the Civil Code. In legal contemplation, subrogation is

the substitution of another person in the place of the creditor, to whose rights he succeeds in relation to the debt; and is independent

of any mere contractual relations between the parties to be affected by it, and is broad enough to cover every instance in which one

party is required to pay a debt for which another is primarily answerable, and which in equity and conscience ought to be discharged by

the latter.

29

Lastly, Vector and Soriano argue that Caltex waived and abandoned its claim by not setting up a cross-claim against them in Civil Case

No. 18735, the suit that Sulpicio Lines, Inc. had brought to claim damages for the loss of the M/V Doa Paz from them, Oriental

Assurance Company (as insurer of the M/T Vector), and Caltex; that such failure to set up its cross-claim on the part of Caltex, the real

party in interest who had suffered the loss, left respondent without any better right than Caltex, its insured, to recover anything from

them, and forever barred Caltex from asserting any claim against them for the loss of the cargo; and that respondent was similarly

barred from asserting its present claim due to its being merely the successor-in-interest of Caltex.

The argument of Vector and Soriano would have substance and merit had Civil Case No. 18735 and this case involved the same

parties and litigated the same rights and obligations. But the two actions were separate from and independent of each other. Civil Case

No. 18735 was instituted by Sulpicio Lines, Inc. to recover damages for the loss of its M/V Doa Paz. In contrast, this action was

brought by respondent to recover from Vector and Soriano whatever it had paid to Caltex under its marine insurance policy on the basis

of its right of subrogation. With the clear variance between the two actions, the failure to set up the cross-claim against them in Civil

Case No. 18735 is no reason to bar this action.

WHEREFORE, the Court DENIES the petition for review on certiorari; AFFIRMS the decision promulgated on July 22, 2003;

and ORDERS petitioners to pay the costs of suit.

SO ORDERED.

Você também pode gostar

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (119)

- Texas Real Estate Sales Exam 4e PDFDocumento287 páginasTexas Real Estate Sales Exam 4e PDFفهد محمد سليمان النمر100% (2)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- Due Diligence Closing ChecklistDocumento6 páginasDue Diligence Closing Checklistklg.consultant2366Ainda não há avaliações

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- 22 June 2012 Review On Risk Based Capital Framework For Insurers in Singapore RBC2 ReviewDocumento33 páginas22 June 2012 Review On Risk Based Capital Framework For Insurers in Singapore RBC2 ReviewKotchapornJirapadchayaropAinda não há avaliações

- Basic legal forms captionsDocumento44 páginasBasic legal forms captionsDan ChowAinda não há avaliações

- Change of Beneficiary LetterDocumento1 páginaChange of Beneficiary LetterRocketLawyer100% (1)

- Annex B-1 RR 11-2018 Sworn Statement of Declaration of Gross Sales and ReceiptsDocumento1 páginaAnnex B-1 RR 11-2018 Sworn Statement of Declaration of Gross Sales and ReceiptsEliza Corpuz Gadon89% (19)

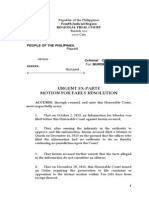

- Philippines Murder Case MotionDocumento2 páginasPhilippines Murder Case MotionMark Agustin100% (6)

- Quiz - iCPADocumento33 páginasQuiz - iCPAGizelle TaguasAinda não há avaliações

- 14 Reinsurance PDFDocumento28 páginas14 Reinsurance PDFHalfani MoshiAinda não há avaliações

- Insurance Contract Interpretation; False Declaration Forfeits BenefitsDocumento2 páginasInsurance Contract Interpretation; False Declaration Forfeits BenefitsdyosaAinda não há avaliações

- Astros Sale ContractDocumento135 páginasAstros Sale ContractHouston ChronicleAinda não há avaliações

- Relationship Marketing Case AnalysisDocumento15 páginasRelationship Marketing Case AnalysisAshish JhaAinda não há avaliações

- Labor Law-Q&ADocumento8 páginasLabor Law-Q&AAldin Lucena AparecioAinda não há avaliações

- METROBANK vs. CABILZO: ALTERED CHECK RECOVERYDocumento9 páginasMETROBANK vs. CABILZO: ALTERED CHECK RECOVERYMichael RentozaAinda não há avaliações

- A.C. No. 6422 August 28, 2007Documento4 páginasA.C. No. 6422 August 28, 2007Leogen TomultoAinda não há avaliações

- Ben ShapiroDocumento11 páginasBen ShapiroLeogen Tomulto100% (1)

- GR 225669 2022Documento14 páginasGR 225669 2022Leogen TomultoAinda não há avaliações

- G.R. No. 164961 June 30, 2014Documento15 páginasG.R. No. 164961 June 30, 2014Leogen TomultoAinda não há avaliações

- Torrent Downloaded FromDocumento1 páginaTorrent Downloaded FromAhmad RonyAinda não há avaliações

- Rules on legal inheritanceDocumento2 páginasRules on legal inheritanceyurets929Ainda não há avaliações

- A.C. No. 6422 August 28, 2007Documento4 páginasA.C. No. 6422 August 28, 2007Leogen TomultoAinda não há avaliações

- Cruz Vs CaDocumento5 páginasCruz Vs CaLeogen TomultoAinda não há avaliações

- Articles of Partnership SampleDocumento3 páginasArticles of Partnership SampleLeogen TomultoAinda não há avaliações

- NUGUID v. CARIÑODocumento3 páginasNUGUID v. CARIÑOLeogen TomultoAinda não há avaliações

- Juris On - Change of Date (Formal Amendment)Documento4 páginasJuris On - Change of Date (Formal Amendment)Leogen TomultoAinda não há avaliações

- Primary Responsibilities of A Human Resource ManagerDocumento2 páginasPrimary Responsibilities of A Human Resource ManagerLeogen TomultoAinda não há avaliações

- Rebusquillo v. DomingoDocumento6 páginasRebusquillo v. DomingoLeogen TomultoAinda não há avaliações

- Rebusquillo v. DomingoDocumento6 páginasRebusquillo v. DomingoLeogen TomultoAinda não há avaliações

- Cruz Vs CaDocumento5 páginasCruz Vs CaLeogen TomultoAinda não há avaliações

- RR 18-01Documento7 páginasRR 18-01JvsticeNickAinda não há avaliações

- People Vs SungaDocumento15 páginasPeople Vs SungaLeogen TomultoAinda não há avaliações

- Revenue Regulations 02-03Documento22 páginasRevenue Regulations 02-03Anonymous HIBt2h6z7Ainda não há avaliações

- 3 RR 6-2001 PDFDocumento17 páginas3 RR 6-2001 PDFJoyceAinda não há avaliações

- JurisDocumento2 páginasJurisLeogen TomultoAinda não há avaliações

- People Vs SungaDocumento15 páginasPeople Vs SungaLeogen TomultoAinda não há avaliações

- People Vs SungaDocumento15 páginasPeople Vs SungaLeogen TomultoAinda não há avaliações

- ADMINISTRATIVE CIRCULAR NO. 4 September 22, 1988Documento3 páginasADMINISTRATIVE CIRCULAR NO. 4 September 22, 1988Leogen TomultoAinda não há avaliações

- Republic of The Philippines, Local Civil Registrar of Cauayan, PetitionersDocumento4 páginasRepublic of The Philippines, Local Civil Registrar of Cauayan, PetitionersLeogen Tomulto100% (1)

- Drilon v. CaDocumento13 páginasDrilon v. CaLeogen TomultoAinda não há avaliações

- Roxas and Co Vs CA and DarDocumento69 páginasRoxas and Co Vs CA and DarChaAinda não há avaliações

- COMELEC ruling on 2010 Barangay elections in Lanao del NorteDocumento8 páginasCOMELEC ruling on 2010 Barangay elections in Lanao del NorteCyber QuestAinda não há avaliações

- 1993 General Insurance Insurance (Prudential Margin)Documento23 páginas1993 General Insurance Insurance (Prudential Margin)Heru SusmonoAinda não há avaliações

- 34 - 136931-1982-Arce - v. - Capital - Insurance - Surety - Co. - Inc.20210701-13-1c2latsDocumento4 páginas34 - 136931-1982-Arce - v. - Capital - Insurance - Surety - Co. - Inc.20210701-13-1c2latsLilian FloresAinda não há avaliações

- GSIS property dispute caseDocumento16 páginasGSIS property dispute caseheyoooAinda não há avaliações

- Questionnaire: Understanding The Consumer'S Preference For Life Insurance ProductDocumento3 páginasQuestionnaire: Understanding The Consumer'S Preference For Life Insurance Productsoumya dubeyAinda não há avaliações

- Car PolilcyDocumento2 páginasCar PolilcyHARI KRISHAN PALAinda não há avaliações

- 2Documento3 páginas2Ruth TenajerosAinda não há avaliações

- Fa180400125 Documents Released PDFDocumento75 páginasFa180400125 Documents Released PDFDilawer singhAinda não há avaliações

- Insurance Policy Dispute Over Alleged MisrepresentationDocumento9 páginasInsurance Policy Dispute Over Alleged Misrepresentationbenjo2001Ainda não há avaliações

- GSBA 524 HW 1 Excel Data Analysis RecommendationDocumento9 páginasGSBA 524 HW 1 Excel Data Analysis RecommendationSheraz AsifAinda não há avaliações

- JLGDocumento6 páginasJLGomprakashrnrAinda não há avaliações

- Indian Contract Act 1872Documento7 páginasIndian Contract Act 1872Aman KambojAinda não há avaliações

- Go Dang 22Documento1 páginaGo Dang 22api-3741515Ainda não há avaliações

- Stock Market Represents Pulse of Economic LifeDocumento23 páginasStock Market Represents Pulse of Economic LifedanielAinda não há avaliações

- CCL Purchase Order for 11KV Power CablesDocumento22 páginasCCL Purchase Order for 11KV Power Cablesokman17Ainda não há avaliações

- Course 3.3: What You Should KnowDocumento18 páginasCourse 3.3: What You Should KnowGeorgios MilitsisAinda não há avaliações

- Customers' perception of insuranceDocumento48 páginasCustomers' perception of insuranceYogendraAinda não há avaliações

- BCBG Max AzriaDocumento25 páginasBCBG Max AzriaZerohedgeAinda não há avaliações

- Irda Ic 33 Model Test 4-EnglishDocumento7 páginasIrda Ic 33 Model Test 4-EnglishPraveen ChaturvediAinda não há avaliações

- As of December 2, 2010: MHA Handbook v3.0 1Documento170 páginasAs of December 2, 2010: MHA Handbook v3.0 1jadlao8000dAinda não há avaliações