Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Yergin 1991

Enviado por

am1liDireitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Yergin 1991

Enviado por

am1liDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

DANIEL YERGIN

THE

PRIZE

THE EPIC QUEST

FO R 0 I L, M 0 N E Y,

AND POWER

A TOUCHSTONE BOOK

Published by Simon & Schuster

New York London Toronto Sydney Tokyo Singapore

Prologue

WINSTO!'l CHURCHILL CHANGED hismind almost overnight. Until thesummer

of I9II, the young Churchi1l, Home Secretary, was one of the leaders of the

"economists," the members of the British Cabinetcritical of the increased mil-

itaryspending that wasbeingpromoted by some to keep ahead in the Anglo-

German naval race. That competition had become the mostrancorous element

in the growing antagonism between the twonations. aut Churchill argued em-

phatically that war with Germany wasnot inevitable, that Germany's intentions

were not necessarily aggressive. The money would be better spent, he insisted,

on domestic social programs than on extrabattleships.

Then on July I, I9II, Kaiser Wilhelm sent a German naval vessel, the

Panther, steaming into the harbor at Agadir, on the Atlantic coast of Morocco.

His aimwas to check French influence in Africa and carve out a position for

Germany. While the Pantuer was onlya gunboat and Agadir wasa port city of

only secondary importance, the arrival of the shipignited a severe international

crisis. The buildup of the German Armywas already causing unease among its

European neighbors; nowGermany, initsdrive forits"placeinthesun,"seemed

to be directly challenging France and Britain's global positions. For several

weeks, war fear gripped Europe. By the end of July, however, the tension had

eased-as Churchill declared, "the bully is climbing down." But the crisis had

transformed Churchill's outlook. Contrary to his earlier assessment of German

intentions, he was nowconvinced that Germany sought hegemony and would

exert its military muscle to gain it. War, he now concluded, was virtually in-

evitable, only a matter of time.

Appointed FirstLordof the Admiralty immediately afterAgadir, Churchill

vowed to doeverything hecould to prepareBritain militarily for theinescapable

dayof reckoning. His charge was to ensure that the Royal Navy, the symbol

II

andvery embodiment ofBritain'simperial power,was readytomeettheGerman

challenge on thehigh seas. Oneof themostimportant andcontentious questions

he faced was seemingly technical in nature, but would in fact havevast impli-

cations for the twentieth century. The issue waswhether to convert the British

Navy to oil for itspowersource, in placeof coal,which was the traditional fuel.

Many thought that sucha conversion waspure folly, for it meant that the Navy

couldnolongerrelyonsafe,secureWelsh coal,but ratherwould haveto depend

on distant and insecure oil supplies fromPersia, as Iran was then known. "To

commit the Navy irrevocably to oil was indeed 'to take arms against a sea of

troubles,' " said Churchill. But the strategic benefits-greater speedand more

efficient use of manpower-were so obvious to himthat he did not dally. He

decided that Britain would have to base its "naval supremacy upon oil" and,

thereupon, committed himself, with all his driving energy and enthusiasm, to

achieving that objective.

There was no choice-in Churchill's words, "Mastery itselfwas the prize

of the venture."!

Withthat, Churchill, ontheeveofWorld WarI, hadcaptured a fundamental

truth, andone applicable not onlyto the conflagration that followed, but to the

manydecades ahead. For oil has meant mastery throughout the twentieth cen-

tury. And that quest for mastery is what this bookis about.

At the beginning of the 1990s-almost eighty years after Churchill made

the commitment to petroleum,after twoWorldWarsanda longColdWar, and

in what was supposed to be the beginning of a new, more peaceful era-oil

onceagainbecamethe focus of global conflict. On August 2, 1990, yet another

of the century's dictators, Saddam Hussein of Iraq, invaded the neighboring

country of Kuwait. Hisgoalwasnot only conquest of a sovereign state, but also

the capture of its riches. The prize was enormous. If successful, Iraq would

becomethe world's leadingoil power, and it would dominate both the Arab

worldand the Persian Gulf, where the bulkof the planet'soil reserves is con-

centrated. Its newstrengthand wealthand control of oil would force the rest

oftheworldtopaycourtto theambitions of SaddamHussein. Withtheresources

of Kuwait, it would be able to make itselfinto a formidable nuclear weapons

state and, perhaps, evenmove down the roadtoward becoming a superpower.

The result would be a dramatic shift in the intemational balance of power. In

short, mastery itselfwasonce more the prize.

But the stakeswereso obviously largethat the invasion of Kuwait wasnot

accepted by the rest of the world as a fait accompli, as Saddam Hussein had

expected. It was not received withthe passivity that had met Hitler's militari-

zationof the Rhineland andMussolini's assault onEthiopia. Instead,the United

Nations instituted an embargo against Iraq, and many nations of the Westem

and Arab worlds dramatically mustered military force to defend neighboring

Saudi Arabiaagainst Iraqand to resist Saddam Hussein's ambitions. There was

noprecedent foreitherthecooperation between theUnitedStatesandtheSoviet

Unionor for the rapidand massive deployment of forces into the region. Over

the previous several years, it hadbecome almost fashionable to saythat oil was

no longer "important." Indeed, in the springof 1990, just a few months before

the Iraqi invasion, the senior officers of America's Central Command, which

12

would be the linchpin of the U.S. mobilization, found themselves lectured to

the effect that oil had lost its strategic significance. But the invasion of Kuwait

stripped away the illusion. In early 1991, when peaceful means failed to secure

an Iraqi withdrawal from Kuwait, a coalition of thirty-three nations, led bythe

UnitedStates, destroyed Iraq's offensive capability in a five-week air war and

one hundredhours of groundbattle, which forced Iraq out of Kuwait. At the

endof the twentieth century, oil wasstill central to security, prosperity, andthe

verynature of civilization.

Though the modemhistory of oil begins inthe latter halfof the nineteenth

century, it is the twentieth century that has beencompletely transformed bythe

adventof petroleum. In particular, three great themesunderlie the storyof oil.

The first is the rise and development of capitalism and modem business. (I'

Oil is the world's biggest and mostpervasive business, the greatest of the great

industries that aroseinthe last decades of the nineteenth century. Standard Oil,

which thoroughly dominated the American petroleum industry by the end of

that century, was among the world's veryfirst and largest multinational enter-

prises. The expansion of the business in the twentieth century-encompassing

everything from wildcat drillers, smooth-talking promoters, and domineering

entrepreneurs to great corporate bureaucracies and state-owned companies-

embodies the twentieth-century evolution of business, of corporate strategy, of

technological change andmarketdevelopment, andindeedof bothnational and

intemational economies. Throughout the history of oil, deals have been done

and momentous decisions have been made-among men, companies, and na-

tions-sometimes with great calculation andsometimes almost byaccident. No

other business sostarkly andextremely defines the meaning of riskandreward-

and the profoundimpactof chance and fate.

As we look toward the twenty-first century, it is clear that mastery will

certainly comeas much from a computer chip as from a barrel of oil. Yet the

petroleumindustry continues to haveenormous impact. Of the top twenty com-

paniesintheFortune500,seven areoilcompanies. Untilsome altemative source

of energy is found, oil will stillhavefar-reaching effects on the global economy;

majorpricemovements canfuel economic growth or, contrarily, driveinflation

and kick off recessions. Today, oil is the only commodity whose doings and

controversies are to be foundregularly not onlyon the business pagebut also

on the front page. And, as in the past, it is a massive generatorof wealth-for

individuals, companies, and entire nations. In the words of one tycoon, "Oil is

almost like money."!

The second themeis that of oil as a commodity intimately intertwined with

national strategies andglobal politics andpower. The battlefields of World War

I established the importance of petroleumasan element of national power when

the intemal combustion machine overtook the horse and the coal-powered lo-

comotive. Petroleum was central to the course and outcome of World War II

inboththe Far East andEurope. TheJapanese attacked Pearl Harborto protect

theirflank astheygrabbed forthepetroleumresources of theEastIndies. Among

Hitler's most important strategic objectives in the invasion of the Soviet Union

was the captureof the oil fields in the Caucasus. But America's predominance

in oil proved decisive, and by the end of the war German and Japanese fuel

13

tanks wereempty. In the ColdWar years, the battle for control of oil between

international companies anddeveloping countries wasa majorpart of the great

drama of deeolonization and emergent nationalism. The Suez Crisis of 195

6,

which trulymarkedthe end of the road for the old European imperial powers,

was as muchabout oil as about anything else. "Oil power" loomed verylarge

in the 1970s, catapulting states heretofore peripheral to international politics

into positions of great wealth and influence, and creating a deep crisis of con-

fidence in the industrial nations that hadbasedtheir economic growth uponoil.

And oil was at the heart of the first post-Cold War crisis of the 1990

s-Iraq's

invasion of Kuwait.

Yet oil has also proved that it can be fool's gold. The Shah of Iran was

granted his most fervent wish, oil wealth, and it destroyed him. Oil built up

Mexico's economy, onlytoundermine it. TheSoviet Union-the world's second-

largest exporter-squandered its enormous oil earnings in the 1970S and 19

80s

in a military buildup and a series of useless and, in some cases, disastrous

international adventures. And the UnitedStates, once the world's largest pro-

ducerandstillits largest consumer, mustimporthalfof itsoilsupply, weakening

its overall strategic position andadding greatly to an already burdensome trade

deficit-a precarious position for a great power.

Withthe endof theColdWar, a newworld orderistaking shape.Economic

competition, regional struggles, andethnicrivalries mayreplace ideology as the

focus of international-and national-conflict, aided and abetted by the pro-

liferation of modern weaponry. But whatever the evolution of this newinter-

national order, oil will remain the strategic commodity, critical to national'

strategies and international politics.

A third theme in the history of oil illuminates how ours has become a

"Hydrocarbon Society" and we, in the language of anthropologists, "Hydro-

carbon Man." In its first decades, the oil business provided an industrializing

worldwitha productcalledby the made-up nameof "kerosene" andknown as

the "new light," which pushed back the night and extended the working day.

At the end of the nineteenth century, John D. Rockefeller had become the

richest man the United States, mostly from the sale of kerosene. Gasoline

was then only an almost useless by-product, which sometimes managed to be

sold for as much as two cents a gallon, and, when it could not be sold at all,

was run out into rivers at night. But just as the invention of the incandescent

lightbulbseemedto signal theobsolescence of theoilindustry, a neweraopened

withthe development of the internal combustion engine powered by gasoline.

The oil industry had a newmarket, and a newcivilization was born.

In the twentieth century, oil, supplemented by natural gas, toppled King

Coal from his throne as the power source for the industrial world. Oil also

became the basis of the great postwar suburbanization movement that trans-

formed both the contemporary landscape and our modern way of life. Today,

we are so dependent on oil, andoil is so embedded in our daily doings, that we

hardly stoptocomprehend itspervasive significance. It isoil that makes possible

where we live, howwe live, how we commute to work, howwe travel-even

where we conduct our courtships. It is the lifeblood of suburban communities.

14

Oil (and natural gas) are the essential components in the fertilizer on which

world agriculture depends; oil makes it possible to transport food to the totally

non-self-sufficient megacities of the world. Oil also provides the plastics and

chemicals that are the bricks and mortar of contemporary civilization, a civili-

zationthat would collapse if the world's oil wells suddenly went dry.

For most of this century, growing reliance on petroleum was almost uni-

versally celebrated as a good, a symbol of human progress. But nolonger. With

the rise of the environmental movement, the basic tenets of industrial society

are being challenged; and the oil industry in all its dimensions is at the top of

the list to be scrutinized, criticized, and opposed. Efforts are mounting around

the world to curtail the combustion of all fossil fuels-oil, coal, and natural

gas-because of the resultant smog and air pollution, acid rain, and ozone

depletion, and because of the specterof climate change. Oil, which is so central

a feature of the world as we know it, is nowaccused of fueling environmental

degradation; and the oil industry, proud of its technological prowess and its

contribution to shaping the modern world, finds itself on the defensive, charged

with being a threat to present and future generations.

Yet Hydrocarbon Manshows littleinclination to give up hiscars, his sub-

urbanhome,andwhathetakestobe not onlytheconveniences but theessentials

of his wayof life. The peoples of the developing world give no indication that

theywant to denythemselves the benefits of an oil-powered economy, whatever

the environmental questions. And any notion of scaling back the world's con-

sumption of oilwill be influenced bytheextraordinary population growth ahead.

In the 1990s, the world's population is expected to grow byone billion people-

20percent more people at the end of thisdecade than at the beginning-with

most of the world's people demanding the "right" to consume. The global

environmental agendas of the industrial world will be measured against the

magnitude of that growth. In the meantime, the stagehas been set for one of

the great and intractable clashes of the 1990s between, on the one hand, the

powerful and increasing support for greater environmental protection and, on

the other, a commitment to economic growth and the benefits of Hydrocarbon

Society, and apprehensions about energy security.

These, then, are the three themes that animate the story that unfolds in

these pages. The canvas is global. The story is a chronicle of epic events that

havetouched all our lives. It concerns itselfbothwith the powerful, impersonal

forces of economics and technology and with the strategies and cunning of

businessmen and politicians. Populating its pages are the tycoons andentrepre-

neurs of the industry-Rockefeller, of course, but also Henri Deterding, Cal-

ouste Gulbenkian, J. Paul Getty, Armand Hammer, T. Boone Pickens, and

many others. Yet no less important to the storyare the likes of Churchill, Adolf

Hitler, Joseph Stalin, Ibn Saud, Mohammed Mossadegh, Dwight Eisenhower,

Anthony Eden, Henry Kissinger, George Bush, and Saddam Hussein.

The twentieth century rightly deserves the title "the century of oil." Yet

for all its conflict andcomplexity, there hasoften been a "oneness" to the story

of oil, a contemporary feel even to events that happened long agoand, simul-

taneously, profound echoes of the past in recent events. At one and the same

15

time, this is a storyof individual people, of powerful economic forces, of tech-.

nological change, of political struggles, of international conflict and, indeed, of

epicchange. It isthe author'shopethat thisexploration of theeconomic, social,

political, andstrategic consequences of our world's reliance onoilwill illuminate

the past, enableus better to understand the present, andhelpto anticipate the

future.

p

A R T I

16

THE

FOUNDERS

Você também pode gostar

- 1 Old Stuff On OilDocumento14 páginas1 Old Stuff On OiljoecerfAinda não há avaliações

- A Century of War 9107Documento3 páginasA Century of War 9107Yasir ZohaAinda não há avaliações

- William Engdahl - A Century of WarDocumento157 páginasWilliam Engdahl - A Century of Wargrzes1Ainda não há avaliações

- Benjamin Freedman Speaks - A Jewish Defector Warns AmericaDocumento32 páginasBenjamin Freedman Speaks - A Jewish Defector Warns AmericaKeith Knight100% (1)

- David S. Painter (2012), "Oil and The American Century", The Journal of American History, Vol. 99, No. 1, Pp. 24-39. DOI:10.1093/jahist/jas073.Documento16 páginasDavid S. Painter (2012), "Oil and The American Century", The Journal of American History, Vol. 99, No. 1, Pp. 24-39. DOI:10.1093/jahist/jas073.Trep100% (1)

- Gulf War of 1990 1991 Maria Joaquina PerezDocumento15 páginasGulf War of 1990 1991 Maria Joaquina PerezJoaca PerezAinda não há avaliações

- Sinking Globalization Author(s) : Niall Ferguson Source: Foreign Affairs, Vol. 84, No. 2 (Mar. - Apr., 2005), Pp. 64-77 Published By: Council On Foreign Relations Accessed: 17-02-2019 13:08 UTCDocumento15 páginasSinking Globalization Author(s) : Niall Ferguson Source: Foreign Affairs, Vol. 84, No. 2 (Mar. - Apr., 2005), Pp. 64-77 Published By: Council On Foreign Relations Accessed: 17-02-2019 13:08 UTCJANICE RHEA P. CABACUNGANAinda não há avaliações

- The US Invasion of IraqDocumento8 páginasThe US Invasion of Iraqq1p0Ainda não há avaliações

- 2 - Porch - Wars of Empire (2000)Documento229 páginas2 - Porch - Wars of Empire (2000)Paul Nieto100% (10)

- Gulf WarDocumento24 páginasGulf WarkyanglisondraAinda não há avaliações

- Managing Strains in The Coalition What To Do About Saddam Pub193Documento30 páginasManaging Strains in The Coalition What To Do About Saddam Pub193scparcoAinda não há avaliações

- Let Justice Be Done Part 2Documento174 páginasLet Justice Be Done Part 2Heidi100% (1)

- Black Gold Hot Gold - Marshall Smith - BrojonDocumento30 páginasBlack Gold Hot Gold - Marshall Smith - BrojonIonut Dobrinescu100% (2)

- Americas Chance of Peace Duncan Aikman Blair Bolles 1939 166pgs POL - SMLDocumento166 páginasAmericas Chance of Peace Duncan Aikman Blair Bolles 1939 166pgs POL - SMLThe Rabbithole WikiAinda não há avaliações

- Contribution and Sacrifice of The Greek NavyDocumento11 páginasContribution and Sacrifice of The Greek NavysdorieasAinda não há avaliações

- A Century of War Anglo-American Oil Politics and The New World OrderDocumento314 páginasA Century of War Anglo-American Oil Politics and The New World OrderKevin White100% (1)

- A Century of War by William EngdahlDocumento314 páginasA Century of War by William Engdahllincoln-6-echo100% (1)

- Unit-13 The Gulf WarDocumento12 páginasUnit-13 The Gulf WarMayank MishraAinda não há avaliações

- 100 Year of IrDocumento15 páginas100 Year of IrIsmail M HassaniAinda não há avaliações

- Dean Ing - Systemic ShockDocumento166 páginasDean Ing - Systemic ShockRahul GabdaAinda não há avaliações

- Workers Vanguard No 37 - 1 February 1974Documento12 páginasWorkers Vanguard No 37 - 1 February 1974Workers VanguardAinda não há avaliações

- Reasearch Paper - OilDocumento18 páginasReasearch Paper - OilAmr Abou HusseinAinda não há avaliações

- This Is A Transcript of The Podcast FromDocumento3 páginasThis Is A Transcript of The Podcast FromZaina ImamAinda não há avaliações

- Sinking Globalization Foreign AffairsDocumento14 páginasSinking Globalization Foreign AffairsJose ZepedaAinda não há avaliações

- Our View On Global Investment Markets:: January 2014 - The ShoeDocumento11 páginasOur View On Global Investment Markets:: January 2014 - The ShoeZerohedgeAinda não há avaliações

- Armshaw (2007) - Coal, Gold and Nationalism An Evaluation of Keynes' 'The Economic Consequences of The Peace'Documento23 páginasArmshaw (2007) - Coal, Gold and Nationalism An Evaluation of Keynes' 'The Economic Consequences of The Peace'Patrick ArmshawAinda não há avaliações

- Search for Security: Saudi Arabian Oil and American Foreign PolicyNo EverandSearch for Security: Saudi Arabian Oil and American Foreign PolicyAinda não há avaliações

- How Did Oil Come To Run Our WorldDocumento8 páginasHow Did Oil Come To Run Our WorldRaji Rafiu BoyeAinda não há avaliações

- Hunting The German Shark; The American Navy In The Underseas War [Illustrated Edition]No EverandHunting The German Shark; The American Navy In The Underseas War [Illustrated Edition]Nota: 3 de 5 estrelas3/5 (1)

- Amerika NovijeDocumento17 páginasAmerika Novijeradoslav micicAinda não há avaliações

- Destructive Creation: American Business and the Winning of World War IINo EverandDestructive Creation: American Business and the Winning of World War IINota: 5 de 5 estrelas5/5 (1)

- The 1973 Oil Crisis and AfterDocumento25 páginasThe 1973 Oil Crisis and AfterConsueloRojasAinda não há avaliações

- The Assessment and Importance of Oil Depletion: by C.J.CampbellDocumento29 páginasThe Assessment and Importance of Oil Depletion: by C.J.CampbellLibya TripoliAinda não há avaliações

- Coleman - We Fight For Oil - A History of US Petroleum Wars (2008)Documento226 páginasColeman - We Fight For Oil - A History of US Petroleum Wars (2008)tonyoneton100% (5)

- Cleveland C.J. (Ed.) - Encyclopedia of Energy Volume 6 (2004, Elsevier) PDFDocumento675 páginasCleveland C.J. (Ed.) - Encyclopedia of Energy Volume 6 (2004, Elsevier) PDFfelipe95007Ainda não há avaliações

- The German Fleet: Being The Companion Volume to "The Fleets At War" and "From Heligoland To Keeling IslandNo EverandThe German Fleet: Being The Companion Volume to "The Fleets At War" and "From Heligoland To Keeling IslandAinda não há avaliações

- History Essay Rough Draft MarchDocumento2 páginasHistory Essay Rough Draft MarchMalek AhmedAinda não há avaliações

- Outside the Box: How Globalization Changed from Moving Stuff to Spreading IdeasNo EverandOutside the Box: How Globalization Changed from Moving Stuff to Spreading IdeasNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (4)

- The Persian Gulf: Mike BlakleyDocumento20 páginasThe Persian Gulf: Mike BlakleyDolly YapAinda não há avaliações

- From the Dreadnought to Scapa Flow: Volume IV: 1917, Year of CrisisNo EverandFrom the Dreadnought to Scapa Flow: Volume IV: 1917, Year of CrisisNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (2)

- WCP UNIT 5Documento13 páginasWCP UNIT 5santhoshraja vAinda não há avaliações

- HilfskreuzerDocumento21 páginasHilfskreuzerSusi Memey100% (2)

- AbioticoilDocumento12 páginasAbioticoilXR500Final100% (3)

- On The Brink: We Take Pacifism Very Seriously! But We Must Get Our ArtilleryDocumento18 páginasOn The Brink: We Take Pacifism Very Seriously! But We Must Get Our ArtillerydelAinda não há avaliações

- IR PresentationDocumento26 páginasIR PresentationSmrithika RongaliAinda não há avaliações

- Russia Proves /'peak Oil/' Is A Misleading Zionist ScamDocumento7 páginasRussia Proves /'peak Oil/' Is A Misleading Zionist ScamTyrone Drummond100% (5)

- Bubble in the Sun: The Florida Boom of the 1920s and How It Brought on the Great DepressionNo EverandBubble in the Sun: The Florida Boom of the 1920s and How It Brought on the Great DepressionNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (22)

- Rise of Integrated International Oil CompaniesDocumento1 páginaRise of Integrated International Oil CompaniesMichelle VaLencia RAinda não há avaliações

- United States and The New Great Game in Central AsiaDocumento9 páginasUnited States and The New Great Game in Central AsiaQulb- E- AbbasAinda não há avaliações

- Land of Promise: An Economic History of the United StatesNo EverandLand of Promise: An Economic History of the United StatesNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (11)

- The War After The War by Marcosson, Isaac Frederick, 1876-1961Documento86 páginasThe War After The War by Marcosson, Isaac Frederick, 1876-1961Gutenberg.orgAinda não há avaliações

- Guardians of the Gulf: A History of America's Expanding Role in the Persion Gulf, 1883-1992No EverandGuardians of the Gulf: A History of America's Expanding Role in the Persion Gulf, 1883-1992Ainda não há avaliações

- The End of The Oil AgeDocumento9 páginasThe End of The Oil Agepranks onlyAinda não há avaliações

- 3.7.C - Third Wave WarDocumento16 páginas3.7.C - Third Wave Warjjamppong09Ainda não há avaliações

- Continuous-Time Fourier Series ProblemsDocumento7 páginasContinuous-Time Fourier Series Problemsam1liAinda não há avaliações

- Desinging Analog ChipsDocumento242 páginasDesinging Analog ChipsRyan Sullenberger100% (12)

- Pcbdesigner PDFDocumento70 páginasPcbdesigner PDFam1liAinda não há avaliações

- SedraSmith6e Appendix GDocumento4 páginasSedraSmith6e Appendix Gam1liAinda não há avaliações

- HP Simple SaveDocumento14 páginasHP Simple SaveWe Wan WangAinda não há avaliações

- bq27520 g4Documento34 páginasbq27520 g4am1liAinda não há avaliações

- Theory and Implementation of Impedance Track™ Battery Fuel-Gauging Algorithm in bq2750x FamilyDocumento11 páginasTheory and Implementation of Impedance Track™ Battery Fuel-Gauging Algorithm in bq2750x Familyanon_643612655Ainda não há avaliações

- 82801eb 82801er Serial Ata ManualDocumento59 páginas82801eb 82801er Serial Ata Manualam1liAinda não há avaliações

- Butterworth Filter Design Solutions ExplainedDocumento11 páginasButterworth Filter Design Solutions Explainedam1liAinda não há avaliações

- Feedback Example: The Inverted Pendulum: Recommended ProblemsDocumento10 páginasFeedback Example: The Inverted Pendulum: Recommended Problemsam1liAinda não há avaliações

- The Art & Science of Protective Relaying - C. Russell Mason - GEDocumento357 páginasThe Art & Science of Protective Relaying - C. Russell Mason - GEAasim MallickAinda não há avaliações

- Agarwal A., Lang J. - Foundations of Analog and Digital Electronic Circuits - Supplemental Sections and Examples - 2005Documento136 páginasAgarwal A., Lang J. - Foundations of Analog and Digital Electronic Circuits - Supplemental Sections and Examples - 2005შაქრო ტრუბეცკოიAinda não há avaliações

- 14Documento23 páginas14am1liAinda não há avaliações

- EMC Design Guide For PCBDocumento78 páginasEMC Design Guide For PCBFaruq AhmedAinda não há avaliações

- FSW Dat-Sw en 5214-5984-22 v0700pdfDocumento32 páginasFSW Dat-Sw en 5214-5984-22 v0700pdfam1liAinda não há avaliações

- L21 f07Documento30 páginasL21 f07am1liAinda não há avaliações

- U17518EJ1V0IF00Documento3 páginasU17518EJ1V0IF00am1liAinda não há avaliações

- Features Description: LT3085 Adjustable 500ma Single Resistor Low Dropout RegulatorDocumento28 páginasFeatures Description: LT3085 Adjustable 500ma Single Resistor Low Dropout Regulatoram1liAinda não há avaliações

- Er100/200 & Pubpol 184/284 Energy and SocietyDocumento47 páginasEr100/200 & Pubpol 184/284 Energy and Societyam1liAinda não há avaliações

- 18 038 RSGHBHC1 S01 2TDocumento12 páginas18 038 RSGHBHC1 S01 2Tam1liAinda não há avaliações

- HW7 f10Documento2 páginasHW7 f10am1liAinda não há avaliações

- AN2799 Application Note: Measuring Mains Power Consumption With The STM32x and STPM01Documento14 páginasAN2799 Application Note: Measuring Mains Power Consumption With The STM32x and STPM01am1liAinda não há avaliações

- PCB DesignerDocumento70 páginasPCB Designeram1liAinda não há avaliações

- Ua709 TiDocumento6 páginasUa709 TiMauro Ferreira De LimaAinda não há avaliações

- 2003 AllochrtDocumento1 página2003 Allochrtam1liAinda não há avaliações

- Midterm Exam Statistics: - ADC ConvertersDocumento30 páginasMidterm Exam Statistics: - ADC Convertersam1liAinda não há avaliações

- Fourier Transform RefDocumento3 páginasFourier Transform RefcustomerxAinda não há avaliações

- Filters (Continued)Documento36 páginasFilters (Continued)am1liAinda não há avaliações

- Midterm Exam Statistics: - ADC ConvertersDocumento30 páginasMidterm Exam Statistics: - ADC Convertersam1liAinda não há avaliações

- Once in his Orient: Le Corbusier and the intoxication of colourDocumento4 páginasOnce in his Orient: Le Corbusier and the intoxication of coloursurajAinda não há avaliações

- Bhojpuri PDFDocumento15 páginasBhojpuri PDFbestmadeeasy50% (2)

- Module 3 - Risk Based Inspection (RBI) Based On API and ASMEDocumento4 páginasModule 3 - Risk Based Inspection (RBI) Based On API and ASMEAgustin A.Ainda não há avaliações

- List/Status of 655 Projects Upto 5.00 MW Capacity As On TodayDocumento45 páginasList/Status of 655 Projects Upto 5.00 MW Capacity As On Todayganvaqqqzz21Ainda não há avaliações

- Surgical Orthodontics Library DissertationDocumento5 páginasSurgical Orthodontics Library DissertationNAVEEN ROY100% (2)

- Marylebone Construction UpdateDocumento2 páginasMarylebone Construction UpdatePedro SousaAinda não há avaliações

- G11SLM10.1 Oral Com Final For StudentDocumento24 páginasG11SLM10.1 Oral Com Final For StudentCharijoy FriasAinda não há avaliações

- Ds 1Documento8 páginasDs 1michaelcoAinda não há avaliações

- Amazfit Bip 5 Manual enDocumento30 páginasAmazfit Bip 5 Manual enJohn WalesAinda não há avaliações

- Effectiveness of Laundry Detergents and Bars in Removing Common StainsDocumento9 páginasEffectiveness of Laundry Detergents and Bars in Removing Common StainsCloudy ClaudAinda não há avaliações

- Unit 6 Lesson 3 Congruent Vs SimilarDocumento7 páginasUnit 6 Lesson 3 Congruent Vs Similar012 Ni Putu Devi AgustinaAinda não há avaliações

- Basic Principles of Social Stratification - Sociology 11 - A SY 2009-10Documento9 páginasBasic Principles of Social Stratification - Sociology 11 - A SY 2009-10Ryan Shimojima67% (3)

- Oxfordhb 9780199731763 e 13Documento44 páginasOxfordhb 9780199731763 e 13florinaAinda não há avaliações

- Identification Guide To The Deep-Sea Cartilaginous Fishes of The Indian OceanDocumento80 páginasIdentification Guide To The Deep-Sea Cartilaginous Fishes of The Indian OceancavrisAinda não há avaliações

- Trinity R&P Keyboards Syllabus From 2018Documento54 páginasTrinity R&P Keyboards Syllabus From 2018VickyAinda não há avaliações

- Hospitality Marketing Management PDFDocumento642 páginasHospitality Marketing Management PDFMuhamad Armawaddin100% (6)

- Piramal Annual ReportDocumento390 páginasPiramal Annual ReportTotmolAinda não há avaliações

- Coasts Case Studies PDFDocumento13 páginasCoasts Case Studies PDFMelanie HarveyAinda não há avaliações

- Surah Al A'araf (7:74) - People of ThamudDocumento2 páginasSurah Al A'araf (7:74) - People of ThamudMuhammad Awais TahirAinda não há avaliações

- Bondor MultiDocumento8 páginasBondor MultiPria UtamaAinda não há avaliações

- A Christmas Carol AdaptationDocumento9 páginasA Christmas Carol AdaptationTockington Manor SchoolAinda não há avaliações

- IB Diploma Maths / Math / Mathematics IB DP HL, SL Portfolio TaskDocumento1 páginaIB Diploma Maths / Math / Mathematics IB DP HL, SL Portfolio TaskDerek Chan100% (1)

- Mariam Kairuz property dispute caseDocumento7 páginasMariam Kairuz property dispute caseReginald Matt Aquino SantiagoAinda não há avaliações

- Schematic Electric System Cat D8T Vol1Documento33 páginasSchematic Electric System Cat D8T Vol1Andaru Gunawan100% (1)

- Review 6em 2022Documento16 páginasReview 6em 2022ChaoukiAinda não há avaliações

- Operative ObstetricsDocumento6 páginasOperative ObstetricsGrasya ZackieAinda não há avaliações

- The Scavenger's Handbook v1 SmallerDocumento33 páginasThe Scavenger's Handbook v1 SmallerBeto TAinda não há avaliações

- Official Website of the Department of Homeland Security STEM OPT ExtensionDocumento1 páginaOfficial Website of the Department of Homeland Security STEM OPT ExtensionTanishq SankaAinda não há avaliações

- Analyzing Transactions To Start A BusinessDocumento22 páginasAnalyzing Transactions To Start A BusinessPaula MabulukAinda não há avaliações

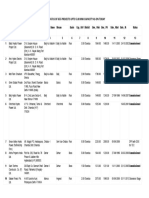

- Exp Mun Feb-15 (Excel)Documento7.510 páginasExp Mun Feb-15 (Excel)Vivek DomadiaAinda não há avaliações

![Hunting The German Shark; The American Navy In The Underseas War [Illustrated Edition]](https://imgv2-2-f.scribdassets.com/img/word_document/259891153/149x198/d1f33f3f94/1617227774?v=1)