Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Nicomachean Ethics: Book 2, Chapter 1

Enviado por

OanaMaria92Título original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Nicomachean Ethics: Book 2, Chapter 1

Enviado por

OanaMaria92Direitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Nicomachean Ethics

Book 2, Chapter 1

VIRTUE, then, being of two kinds, intellectual and moral, intellectual virtue in the main owes both its

birth and its growth to teaching (for which reason it requires exerience and time!, while moral virtue

comes about as a result of habit, whence also its name (ethike! is one that is formed b" a slight

variation from the word ethos (habit!# $rom this it is also lain that none of the moral virtues arises in

us b" nature% for nothing that exists b" nature can form a habit contrar" to its nature# $or instance the

stone which b" nature moves downwards cannot be habituated to move uwards, not even if one tries

to train it b" throwing it u ten thousand times% nor can fire be habituated to move downwards, nor can

an"thing else that b" nature behaves in one wa" be trained to behave in another# &either b" nature,

then, nor contrar" to nature do the virtues arise in us% rather we are adated b" nature to receive them,

and are made erfect b" habit#

'gain, of all the things that come to us b" nature we first acquire the otentialit" and later exhibit the

activit" (this is lain in the case of the senses% for it was not b" often seeing or often hearing that we

got these senses, but on the contrar" we had them before we used them, and did not come to have

them b" using them!% but the virtues we get b" first exercising them, as also haens in the case of the

arts as well# $or the things we have to learn before we can do them, we learn b" doing them, e#g# men

become builders b" building and l"rela"ers b" la"ing the l"re% so too we become (ust b" doing (ust

acts, temerate b" doing temerate acts, brave b" doing brave acts#

This is confirmed b" what haens in states% for legislators make the citi)ens good b" forming habits

in them, and this is the wish of ever" legislator, and those who do not effect it miss their mark, and it

is in this that a good constitution differs from a bad one#

'gain, it is from the same causes and b" the same means that ever" virtue is both roduced and

destro"ed, and similarl" ever" art% for it is from la"ing the l"re that both good and bad l"re*la"ers

are roduced# 'nd the corresonding statement is true of builders and of all the rest% men will be good

or bad builders as a result of building well or badl"# $or if this were not so, there would have been no

need of a teacher, but all men would have been born good or bad at their craft# This, then, is the case

with the virtues also% b" doing the acts that we do in our transactions with other men we become (ust

or un(ust, and b" doing the acts that we do in the resence of danger, and being habituated to feel fear

or confidence, we become brave or cowardl"# The same is true of aetites and feelings of anger%

some men become temerate and good*temered, others self*indulgent and irascible, b" behaving in

one wa" or the other in the aroriate circumstances# Thus, in one word, states of character arise out

of like activities# This is wh" the activities we exhibit must be of a certain kind% it is because the states

of character corresond to the differences between these# It makes no small difference, then, whether

we form habits of one kind or of another from our ver" "outh% it makes a ver" great difference, or

rather all the difference#

Book 2, Chapter 2

+ince, then, the resent inquir" does not aim at theoretical knowledge like the others (for we are

inquiring not in order to know what virtue is, but in order to become good, since otherwise our inquir"

would have been of no use!, we must examine the nature of actions, namel" how we ought to do them%

for these determine also the nature of the states of character that are roduced, as we have said# &ow,

that we must act according to the right rule is a common rincile and must be assumed ** it will be

discussed later, i#e# both what the right rule is, and how it is related to the other virtues# ,ut this must

be agreed uon beforehand, that the whole account of matters of conduct must be given in outline and

not recisel", as we said at the ver" beginning that the accounts we demand must be in accordance

with the sub(ect*matter% matters concerned with conduct and questions of what is good for us have no

fixit", an" more than matters of health# The general account being of this nature, the account of

articular cases is "et more lacking in exactness% for the" do not fall under an" art or recet but the

agents themselves must in each case consider what is aroriate to the occasion, as haens also in

the art of medicine or of navigation#

,ut though our resent account is of this nature we must give what hel we can# $irst, then, let us

consider this, that it is the nature of such things to be destro"ed b" defect and excess, as we see in the

case of strength and of health (for to gain light on things imercetible we must use the evidence of

sensible things!% both excessive and defective exercise destro"s the strength, and similarl" drink or

food which is above or below a certain amount destro"s the health, while that which is roortionate

both roduces and increases and reserves it# +o too is it, then, in the case of temerance and courage

and the other virtues# $or the man who flies from and fears ever"thing and does not stand his ground

against an"thing becomes a coward, and the man who fears nothing at all but goes to meet ever"

danger becomes rash% and similarl" the man who indulges in ever" leasure and abstains from none

becomes self*indulgent, while the man who shuns ever" leasure, as boors do, becomes in a wa"

insensible% temerance and courage, then, are destro"ed b" excess and defect, and reserved b" the

mean#

,ut not onl" are the sources and causes of their origination and growth the same as those of their

destruction, but also the shere of their actuali)ation will be the same% for this is also true of the things

which are more evident to sense, e#g# of strength% it is roduced b" taking much food and undergoing

much exertion, and it is the strong man that will be most able to do these things# +o too is it with the

virtues% b" abstaining from leasures we become temerate, and it is when we have become so that we

are most able to abstain from them% and similarl" too in the case of courage% for b" being habituated to

desise things that are terrible and to stand our ground against them we become brave, and it is when

we have become so that we shall be most able to stand our ground against them#

Book 2, Chapter 3

-e must take as a sign of states of character the leasure or ain that ensues on acts% for the man who

abstains from bodil" leasures and delights in this ver" fact is temerate, while the man who is

anno"ed at it is self*indulgent, and he who stands his ground against things that are terrible and

delights in this or at least is not ained is brave, while the man who is ained is a coward# $or moral

excellence is concerned with leasures and ains% it is on account of the leasure that we do bad

things, and on account of the ain that we abstain from noble ones# .ence we ought to have been

brought u in a articular wa" from our ver" "outh, as /lato sa"s, so as both to delight in and to be

ained b" the things that we ought% for this is the right education#

'gain, if the virtues are concerned with actions and assions, and ever" assion and ever" action is

accomanied b" leasure and ain, for this reason also virtue will be concerned with leasures and

ains# This is indicated also b" the fact that unishment is inflicted b" these means% for it is a kind of

cure, and it is the nature of cures to be effected b" contraries#

'gain, as we said but latel", ever" state of soul has a nature relative to and concerned with the kind of

things b" which it tends to be made worse or better% but it is b" reason of leasures and ains that men

become bad, b" ursuing and avoiding these ** either the leasures and ains the" ought not or when

the" ought not or as the" ought not, or b" going wrong in one of the other similar wa"s that ma" be

distinguished# .ence men even define the virtues as certain states of imassivit" and rest% not well,

however, because the" seak absolutel", and do not sa" 0as one ought0 and 0as one ought not0 and 0when

one ought or ought not0, and the other things that ma" be added# -e assume, then, that this kind of

excellence tends to do what is best with regard to leasures and ains, and vice does the contrar"#

The following facts also ma" show us that virtue and vice are concerned with these same things# There

being three ob(ects of choice and three of avoidance, the noble, the advantageous, the leasant, and

their contraries, the base, the in(urious, the ainful, about all of these the good man tends to go right

and the bad man to go wrong, and eseciall" about leasure% for this is common to the animals, and

also it accomanies all ob(ects of choice% for even the noble and the advantageous aear leasant#

'gain, it has grown u with us all from our infanc"% this is wh" it is difficult to rub off this assion,

engrained as it is in our life# 'nd we measure even our actions, some of us more and others less, b" the

rule of leasure and ain# $or this reason, then, our whole inquir" must be about these% for to feel

delight and ain rightl" or wrongl" has no small effect on our actions#

'gain, it is harder to fight with leasure than with anger, to use .eraclitus0 hrase0, but both art and

virtue are alwa"s concerned with what is harder% for even the good is better when it is harder#

Therefore for this reason also the whole concern both of virtue and of olitical science is with

leasures and ains% for the man who uses these well will be good, he who uses them badl" bad#

That virtue, then, is concerned with leasures and ains, and that b" the acts from which it arises it is

both increased and, if the" are done differentl", destro"ed, and that the acts from which it arose are

those in which it actuali)es itself ** let this be taken as said#

Você também pode gostar

- Understanding Authority For Effective Leadership - Buddy HarrisonDocumento103 páginasUnderstanding Authority For Effective Leadership - Buddy HarrisonLia Souza100% (2)

- Standard Patent License Agreement: ConfidentialDocumento9 páginasStandard Patent License Agreement: ConfidentialAnonymous LUf2MY7dAinda não há avaliações

- Incident Summary Report: Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission 8535 Northlake BLVD West Palm Beach, FLDocumento5 páginasIncident Summary Report: Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission 8535 Northlake BLVD West Palm Beach, FLAlexandra RodriguezAinda não há avaliações

- Chapter 1: The Great QuestionsDocumento7 páginasChapter 1: The Great QuestionsMikaela Victoria LopezAinda não há avaliações

- 19 - Ethics in Business ExamsDocumento40 páginas19 - Ethics in Business ExamsMěrĭem Amǡ100% (16)

- Accept Their Oath 4Documento20 páginasAccept Their Oath 4varg12184315100% (2)

- Aristotle - RhetoricDocumento100 páginasAristotle - RhetoricJogesh SinghAinda não há avaliações

- Soti Hui Maa Ki Chudai Sex Story 2 - KamukKissaDocumento11 páginasSoti Hui Maa Ki Chudai Sex Story 2 - KamukKissadavidAinda não há avaliações

- Kazuhiro Hasegawa Vs KitamuraDocumento5 páginasKazuhiro Hasegawa Vs KitamuraMi-young Sun100% (2)

- Module 3 GMRCDocumento7 páginasModule 3 GMRCLyra Nathalia Juanillo79% (19)

- Astrida Neimanis Bodies of Water Posthuman Feminist PhenomenologyDocumento33 páginasAstrida Neimanis Bodies of Water Posthuman Feminist Phenomenologyh3ftyAinda não há avaliações

- Position Paper Dti CaseDocumento11 páginasPosition Paper Dti Casemacebailey100% (3)

- Fast Cars and Bad Girls - Deborah Paes de BarrosDocumento32 páginasFast Cars and Bad Girls - Deborah Paes de BarrosMonique Comin LosinaAinda não há avaliações

- 3rd QUARTERLY EXAM IN CESC (Exam Edited)Documento8 páginas3rd QUARTERLY EXAM IN CESC (Exam Edited)Vinlax ArguillesAinda não há avaliações

- Hedonism and StoicismDocumento3 páginasHedonism and StoicismEbert JaranillaAinda não há avaliações

- 8435 All Circumstances of Life Offer Opportunities To Mature ....Documento4 páginas8435 All Circumstances of Life Offer Opportunities To Mature ....Marianne ZipfAinda não há avaliações

- Classics MitDocumento2 páginasClassics Mit001Ainda não há avaliações

- Rhetoric: by Aristotle Written 350 B.C.E Translated by W. Rhys RobertsDocumento9 páginasRhetoric: by Aristotle Written 350 B.C.E Translated by W. Rhys RobertsBeatrice RaduAinda não há avaliações

- Moral Absolutes Must Be Learned: TypesDocumento7 páginasMoral Absolutes Must Be Learned: TypesasaadAinda não há avaliações

- 6-Self-Reflection and Action - OdtDocumento8 páginas6-Self-Reflection and Action - Odtk1balionAinda não há avaliações

- Rights: Thomas Hobbes (1588-1679)Documento11 páginasRights: Thomas Hobbes (1588-1679)Timmy Tran100% (1)

- Virtue Is The Mean Between The Extreme VicesDocumento4 páginasVirtue Is The Mean Between The Extreme VicesbittedAinda não há avaliações

- Moral DiversityDocumento19 páginasMoral DiversityMano ManioAinda não há avaliações

- Conduct: by Maurice FredalDocumento2 páginasConduct: by Maurice Fredalxenocid3rAinda não há avaliações

- Personality Theories: An Introduction: Dr. C. George BoereeDocumento4 páginasPersonality Theories: An Introduction: Dr. C. George BoereeBenitez GheroldAinda não há avaliações

- Adab Al-Suluk - A Treatise On Spiritual WayfaringDocumento6 páginasAdab Al-Suluk - A Treatise On Spiritual Wayfaringrm_pi5282100% (1)

- Is Life A Gift?Documento2 páginasIs Life A Gift?Yousuf M Islam100% (1)

- Ayer, A. J., Los Problemas Del Conocimiento, Eudeba, Buenos Aires, 1985Documento17 páginasAyer, A. J., Los Problemas Del Conocimiento, Eudeba, Buenos Aires, 1985danielgonzreyesAinda não há avaliações

- HANDOUT - Kant, Deontological EthicsDocumento13 páginasHANDOUT - Kant, Deontological EthicsabbenayAinda não há avaliações

- Authority: By: George S. ArundaleDocumento8 páginasAuthority: By: George S. Arundalexenocid3rAinda não há avaliações

- What Would Aristotle and Kant DoDocumento6 páginasWhat Would Aristotle and Kant DoHannahAinda não há avaliações

- Unit 1 - Nature and Scope of EthicsDocumento10 páginasUnit 1 - Nature and Scope of EthicsVarun NehruAinda não há avaliações

- Mirrors IntroDocumento3 páginasMirrors IntroVictor B. MamaniAinda não há avaliações

- The Power of Believing PDFDocumento4 páginasThe Power of Believing PDFJoannaAllen0% (1)

- Clobbering Biblical Gay Bashing PrintableDocumento9 páginasClobbering Biblical Gay Bashing PrintableKimberly Parton BolinAinda não há avaliações

- Early Modern PeriodDocumento5 páginasEarly Modern PeriodHarris AcobaAinda não há avaliações

- 7 Deadly SinsDocumento10 páginas7 Deadly SinsjoshkrebsAinda não há avaliações

- 10 Principles For Peace of MindDocumento3 páginas10 Principles For Peace of MindNitinKumarAinda não há avaliações

- The Structure of Desire and Recognition:: Self-Consciousness and Self-ConstitutionDocumento32 páginasThe Structure of Desire and Recognition:: Self-Consciousness and Self-ConstitutionTiffany DavisAinda não há avaliações

- Morals and BehaviourDocumento53 páginasMorals and Behaviourhip18Ainda não há avaliações

- The Power of WordsDocumento5 páginasThe Power of WordsJOSEPHMUTISOAinda não há avaliações

- NERO200 Document 1Documento3 páginasNERO200 Document 1Angga HadianAinda não há avaliações

- Dan Sperber The Guru EffectDocumento10 páginasDan Sperber The Guru EffectisabeluskaAinda não há avaliações

- Logical DescriptionDocumento23 páginasLogical DescriptionCedric ZhouAinda não há avaliações

- Swinburne 2008-MoralityDocumento13 páginasSwinburne 2008-MoralitydlaracoceraAinda não há avaliações

- What Really Matters?: Lesson 2Documento8 páginasWhat Really Matters?: Lesson 2michel.dawAinda não há avaliações

- Sexuality in IslamDocumento100 páginasSexuality in IslamRadulescu MarianAinda não há avaliações

- As You Sow, So Shall You ReapDocumento6 páginasAs You Sow, So Shall You ReapAnu PomAinda não há avaliações

- Same God in All Incarnations and Same Soul in All Living BeingsDocumento4 páginasSame God in All Incarnations and Same Soul in All Living Beingsklewis210Ainda não há avaliações

- EE195 Doc 5Documento5 páginasEE195 Doc 5lou mallariAinda não há avaliações

- Week 1-Mt Lesson Gec 8 EthicsDocumento6 páginasWeek 1-Mt Lesson Gec 8 EthicsBenBhadzAidaniOmboyAinda não há avaliações

- Moral Community and Animal - Sapontzis RightsDocumento8 páginasMoral Community and Animal - Sapontzis RightsTommy ChoiAinda não há avaliações

- Basic Problems of Human and Their SolutionsDocumento8 páginasBasic Problems of Human and Their Solutionssweetkanwal61Ainda não há avaliações

- HO Features of A's Moral TheoryDocumento3 páginasHO Features of A's Moral TheoryReza KhajeAinda não há avaliações

- Human FreedomDocumento17 páginasHuman FreedombenreddingtonAinda não há avaliações

- jurnAL 1966Documento9 páginasjurnAL 1966Siti afifah SahasikaAinda não há avaliações

- SuttasangahaDocumento28 páginasSuttasangahaThan PhyoAinda não há avaliações

- Clark Forklift SM 709 Gen2 c15c 35cmay 2001 Service ManualDocumento22 páginasClark Forklift SM 709 Gen2 c15c 35cmay 2001 Service Manualjohnathanfoster080802obr100% (24)

- Identify The Main Features of Risk-Seeking BehaviourDocumento9 páginasIdentify The Main Features of Risk-Seeking BehaviourFrances Abigail BubanAinda não há avaliações

- Note 7 Me MralDocumento8 páginasNote 7 Me MralAl MahdiAinda não há avaliações

- CPE347 Diagram 9Documento6 páginasCPE347 Diagram 9Zuhad Mahya HisbullahAinda não há avaliações

- A Note On Standards: A Short Essay Concerning Rights, Purpose, and MoralityDocumento8 páginasA Note On Standards: A Short Essay Concerning Rights, Purpose, and MoralityChris SchwarzAinda não há avaliações

- Ethics - Midterm Notes 1Documento3 páginasEthics - Midterm Notes 1johncarlo ramosAinda não há avaliações

- 5 Right ReasonDocumento4 páginas5 Right ReasonPatricia Mae ParungaoAinda não há avaliações

- Part 16 in Reality, Who Are We?Documento8 páginasPart 16 in Reality, Who Are We?ralph_knowlesAinda não há avaliações

- Read The Text BelowDocumento3 páginasRead The Text Belowdela_delasAinda não há avaliações

- Aristotle - Voluntary and Involuntary ActionDocumento3 páginasAristotle - Voluntary and Involuntary ActionTalena WingfieldAinda não há avaliações

- DefinitionsDocumento38 páginasDefinitionsa_shakoorAinda não há avaliações

- 3 RISC + PipelinesDocumento55 páginas3 RISC + PipelinesOanaMaria92Ainda não há avaliações

- Risk Short IntroductionDocumento3 páginasRisk Short IntroductionOanaMaria92Ainda não há avaliações

- HousesDocumento1 páginaHousesOanaMaria92Ainda não há avaliações

- Distinguishing Between An Establishment-An Economic Unit at A Single Location-And A Firm or Company-A Business Organization Consisting of One or More Domestic Establishments Under Common OwnershipDocumento4 páginasDistinguishing Between An Establishment-An Economic Unit at A Single Location-And A Firm or Company-A Business Organization Consisting of One or More Domestic Establishments Under Common OwnershipOanaMaria92Ainda não há avaliações

- Evaluation Results - TipsEvaluation Issue 14, Fact SheetDocumento4 páginasEvaluation Results - TipsEvaluation Issue 14, Fact SheetOanaMaria92Ainda não há avaliações

- Budget TheoryyDocumento18 páginasBudget TheoryyOanaMaria92Ainda não há avaliações

- Summary of Current Theories Explaining Domestic Violence: Patriarchal TheoryDocumento3 páginasSummary of Current Theories Explaining Domestic Violence: Patriarchal TheoryOanaMaria92Ainda não há avaliações

- FilmeDocumento1 páginaFilmeOanaMaria92Ainda não há avaliações

- Trasaturi FundamentalismDocumento1 páginaTrasaturi FundamentalismOanaMaria92Ainda não há avaliações

- FATE - Tianxia - Arcana For The Deck of Fate (Blue)Documento4 páginasFATE - Tianxia - Arcana For The Deck of Fate (Blue)Sylvain DurandAinda não há avaliações

- Marcos Vs Sandiganbayan October 6, 1998Documento9 páginasMarcos Vs Sandiganbayan October 6, 1998khoire12Ainda não há avaliações

- The Interface Between Competition Law & Intellectual PropertyDocumento25 páginasThe Interface Between Competition Law & Intellectual PropertymanpritkaurAinda não há avaliações

- Simple Red and Beige Vintage Illustration History Report PresentationDocumento16 páginasSimple Red and Beige Vintage Illustration History Report Presentationangelicasuzane.larcenaAinda não há avaliações

- PLM OJT Evaluation FormDocumento5 páginasPLM OJT Evaluation FormAyee GarciaAinda não há avaliações

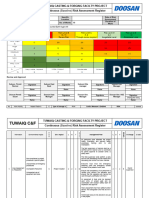

- RA 18 (Well Bore Using Excavator Mounted Earth Auger Drill) 2Documento8 páginasRA 18 (Well Bore Using Excavator Mounted Earth Auger Drill) 2abdulthahseen007Ainda não há avaliações

- Ogl 321 Mod 2 PaperDocumento7 páginasOgl 321 Mod 2 Paperapi-661006801Ainda não há avaliações

- Token Gestures: The Effects of The Voucher Scheme On Asylum Seekers and Organisations in The UKDocumento25 páginasToken Gestures: The Effects of The Voucher Scheme On Asylum Seekers and Organisations in The UKOxfamAinda não há avaliações

- Jdocs Framework v6 Final ArtworkDocumento65 páginasJdocs Framework v6 Final ArtworkRGAinda não há avaliações

- 01 Philosophy of IBFDocumento46 páginas01 Philosophy of IBFamirahAinda não há avaliações

- Vedanta QuotationDocumento16 páginasVedanta QuotationImran BaigAinda não há avaliações

- R V Maclean 2019 NUCJ 02Documento17 páginasR V Maclean 2019 NUCJ 02NunatsiaqNewsAinda não há avaliações

- Conflict ResolutionDocumento1 páginaConflict ResolutionpRiNcE DuDhAtRaAinda não há avaliações

- HISTORYDocumento3 páginasHISTORYJayson Alvarez MagnayeAinda não há avaliações

- Criminological Theory Context and Consequences 6th Edition Lilly Test BankDocumento25 páginasCriminological Theory Context and Consequences 6th Edition Lilly Test BankMrRogerAndersonMDdbkj100% (60)

- Compilation of Circular-Rules-Order On LeaveDocumento9 páginasCompilation of Circular-Rules-Order On Leaverijin00cAinda não há avaliações

- Update: Diagnostic Statistical Manual Mental DisordersDocumento30 páginasUpdate: Diagnostic Statistical Manual Mental DisordersraudahAinda não há avaliações

- North Wrongdoing and ForgivenessDocumento11 páginasNorth Wrongdoing and ForgivenessKhang Vi NguyenAinda não há avaliações

- Instructor Syllabus/ Course Outline: Page 1 of 5Documento5 páginasInstructor Syllabus/ Course Outline: Page 1 of 5Jordan SperanzoAinda não há avaliações

- 2.10. Yu Tek & Co. v. Gonzales, 29 Phil. 384 (1915)Documento3 páginas2.10. Yu Tek & Co. v. Gonzales, 29 Phil. 384 (1915)Winnie Ann Daquil LomosadAinda não há avaliações