Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Cases

Enviado por

Kristine Jean Santiago Bacala0 notas0% acharam este documento útil (0 voto)

30 visualizações88 páginasphilosophy of law

cases

Direitos autorais

© © All Rights Reserved

Formatos disponíveis

PDF, TXT ou leia online no Scribd

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentophilosophy of law

cases

Direitos autorais:

© All Rights Reserved

Formatos disponíveis

Baixe no formato PDF, TXT ou leia online no Scribd

0 notas0% acharam este documento útil (0 voto)

30 visualizações88 páginasCases

Enviado por

Kristine Jean Santiago Bacalaphilosophy of law

cases

Direitos autorais:

© All Rights Reserved

Formatos disponíveis

Baixe no formato PDF, TXT ou leia online no Scribd

Você está na página 1de 88

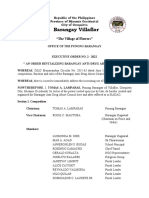

EN BANC

[G.R. No. 95887. December 29, 1995.]

MAY AMOLO, represented by her parents MR. & MRS. ISAIAS

AMOLO, REDFORD ALSADO, JOEBERT ALSADO, & RUDYARD

ALSADO represented by their parents MR. & MRS. ABELARDO

ALSADO, NESIA ALSADO, REU ALSADO and LILIBETH ALSADO,

represented by their parents MR. & MRS. ROLANDO ALSADO,

SUZETTE NAPOLES, represented by her parents ISMAILITO NAPOLES

and OPHELIA NAPOLES, JESICA CARMELOTES, represented by her

parents MR. & MRS. SERGIO CARMELOTES, BABY JEAN MACAPAS,

represented by her parents MR. & MRS. TORIBIO MACAPAS,

GERALDINE ALSADO, represented by her parents MR. & MRS. JOEL

ALSADO, RAQUEL DEMOTOR, and LEAH DEMOTOR, represented by

their parents MR. & MRS. LEONARDO DEMOTOR, JURELL VILLA and

MELONY VILLA represented by their parents MR. & MRS.

JOVENIANO VILLA, JONELL HOPE MAHINAY, MARY GRACE

MAHINAY, and MAGDALENE MAHINAY, represented by their parents

MR. & MRS. FELIX MAHINAY, JONALYN ANTIOLA and JERWIN

ANTIOLA represented by their parents FELIPE ANTIOLA and ANECITA

ANTIOLA, MARIA CONCEPCION CABUYAO, represented by her

parents WENIFREDO CABUYAO and ESTRELLITA CABUYAO, NOEMI

TURNO represented by her parents MANUEL TURNO and VEVENCIA

TURNO, SOLOMON PALATULON, SALMERO PALATULON and

ROSALINA PALATULON, represented by their parents MARTILLANO

PALATULON and CARMILA PALATULON, petitioners, vs. THE DIVISION

SUPERINTENDENT OF SCHOOLS OF CEBU, and ANTONIO A.

SANGUTAN, respondents.

Felino M. Ganal for petitioners.

The Solicitor General for respondents.

SYLLABUS

1. POLITICAL LAW; STATE; RESPONSIBILITY TO INCULCATE VALUES OF PATRIOTISM AND

NATIONALISM; SHOULD NOT INTRUDE INTO OTHER FUNDAMENTAL RIGHTS. The State possesses

what the Solicitor General describes as the responsibility "to inculcate in the minds of the youth the values

of patriotism and nationalism and to encourage their involvement in public and civic affairs." The teaching

of these values ranks at the very apex of education's "high responsibility" of shaping up the minds of the

youth in those principles which would mold them into responsible and productive members of our society.

However, the government's interest in molding the young into patriotic and civic spirited citizens is "not

totally free from a balancing process" when it intrudes into other fundamental rights such as those

specifically protected by the Free Exercise Clause, the constitutional right to education and the unassailable

interest of parents to guide the religious upbringing of their children in accordance with the dictates of their

conscience and their sincere religious beliefs. Recognizing these values, Justice Carolina Grio-Aquino, the

writer of the original opinion, underscored that a generation of Filipinos which cuts its teeth on the Bill of

Rights would find abhorrent the idea that one may be compelled, on pain of expulsion, to salute the flag,

sing the national anthem and recite the patriotic pledge during a flag ceremony. "This coercion of

conscience has no place in a free society." CAaSHI

2. CONSTITUTIONAL LAW; BILL OF RIGHTS; FREEDOM OF RELIGION; A PREFERRED FREEDOM AND

SHOULD BE SEEN AS THE RULE NOT THE EXCEPTION. The State's contentions are therefore,

unacceptable, for no less fundamental than the right to take part is the right to stand apart. In the context

of the instant case, the freedom of religion enshrined in the Constitution should be seen as the rule, not the

exception. To view the constitutional guarantee in the manner suggested by the petitioners would be to

denigrate the status of a preferred freedom and to relegate it to the level of an abstract principle devoid of

any substance and meaning in the lives of those for whom the protection is addressed.

3. ID.; ID.; ID.; ESSENCE IS FREEDOM FROM CONFORMITY TO RELIGIOUS DOGMA. As to the

contention that the exemption accorded by our decision benefits a privileged few, it is enough to re-

emphasize that "the constitutional protection of religious freedom terminated disabilities, it did not create

new privileges. It gave religious equality, not civil immunity." The essence of the free exercise clause is

freedom from conformity to religious dogma, not freedom from conformity to law because of religious

dogma.

4. ID.; ID.; ID.; FLAG CEREMONY REQUIREMENT; MAY OFFEND GOVERNMENT NEUTRALITY IF IT

UNDULY BURDENS RIGHT. The suggestion implicit in the State's pleadings to the effect that the flag

ceremony requirement would be equally and evenly applied to all citizens regardless of sect or religion and

does not thereby discriminate against any particular sect or denomination escapes the fact that "[a]

regulation, neutral on its face, may in its application, nonetheless offend the constitutional requirement for

governmental neutrality if it unduly burdens the free exercise of religion. cCaEDA

5. POLITICAL LAW; STATE; CLEAR AND PRESENT DANGER RULE; ONLY GROUND WHERE REGULATION

AFFECTING CONSTITUTIONAL RIGHTS MAY BE ABRIDGED; NO CLEAR AND PRESENT DANGER IN

REFUSAL TO SALUTE FLAG AND RECITE PLEDGE. Where the governmental interest clearly appears to

be unrelated to the suppression of an idea, a religious doctrine or practice or an expression or form of

expression, this Court will not find it difficult to sustain a regulation. However, regulations involving this area

are generally held against the most exacting standards, and the zone of protection accorded by the

Constitution cannot be violated, except upon a showing of a clear and present danger of a substantive evil

which the state has a right to protect. Stated differently, in the case of a regulation which appears to

abridge a right to which the fundamental law accords high significance it is the regulation, not the act (or

refusal to act), which is the exception and which requires the court's strictest scrutiny. In the case at bench,

the government has not shown that refusal to do the acts of conformity exacted by the assailed orders,

which respondents point out attained legislative cachet in the Administrative Code of 1987, would pose a

clear and present danger of a danger so serious and imminent, that it would prompt legitimate State

intervention.

6. CONSTITUTIONAL LAW; BILL OF RIGHTS; FREEDOM OF RELIGION; FLAG IS A RELIGIOUS SYMBOL.

While the very concept of ordered liberty precludes this Court from allowing every individual to

subjectively define his own standards on matters of conformity in which society, as a whole has important

interests, the records of the case and the long history of flag salute cases abundantly supports the religious

quality of the claims adduced by the members of the sect Jehovah's Witnesses. Their treatment of flag as a

religious symbol is well-founded and well-documented and is based on grounds of religious principle. The

message conveyed by their refusal to participate in the flag ceremony is religious, shared by the entire

community of Jehovah's Witnesses and is intimately related to their theocratic beliefs and convictions. The

subsequent expulsion of members of the sect on the basis of the regulations assailed in the original

petitions was therefore clearly directed against religious practice. It is obvious that the assailed orders and

memoranda would gravely endanger the free exercise of the religious beliefs of the members of the sect

and their minor children.

7. ID.; ID.; ID.; REFUSAL TO PARTICIPATE IN THE FLAG SALUTE CEREMONY HARDLY CONSTITUTES A

DANGER SO GRAVE AND IMMINENT TO WARRANT STATE INTERVENTION. To the extent to which

members of the Jehovah's Witnesses sect assiduously pursue their belief in the flag's religious symbolic

meaning, the State cannot, without thereby transgressing constitutionally protected boundaries, impose the

contrary view on the pretext of sustaining a policy designed to foster the supposedly far-reaching goal of

instilling patriotism among the youth. While conceding to the idea adverted to by the Solicitor General

that certain methods of religious expression may be prohibited to serve legitimate societal purposes,

refusal to participate in the flag ceremony hardly constitutes a form of religious expression so offensive and

noxious as to prompt legitimate State intervention. It is worth repeating that the absence of a demonstrable

danger of a kind which the State is empowered to protect militates against the extreme disciplinary

methods undertaken by school authorities in trying to enforce regulations designed to compel attendance

in flag ceremonies. Refusal of the children to participate in the flag salute ceremony would not interfere with

or deny the rights of other school children to do so. It bears repeating that their absence from the

ceremony hardly constitutes a danger so grave and imminent as to warrant the state's intervention.'

8. ID.; ID.; ID.; ID.; TEST IN O'BRIEN CASE APPLIES ONLY IF THE STATE REGULATION IS NOT RELATED

TO COMMUNICATIVE CONDUCT. The respondents' insistence on the validity of the actions taken by

the government on the basis of their averment that "a government regulation of expressive conduct is

sufficiently justified if it is within the constitutional power of the government (and) furthers an important and

substantial government interest" misses the whole point of the test devised by the United States Supreme

Court in O'Brien, cited by respondent, because the Court therein was emphatic in stating that "the

government interest (should be) unrelated to the suppression of free expression." We have already stated

that the interest in regulation in the case at bench was clearly related to the suppression of an expression

directly connected with the freedom of religion and that respondents have not shown to our satisfaction

that the restriction was prompted by a compelling interest in public order which the state has a right to

protect. Moreover, if we were to refer (as respondents did by referring to the test in O'Brien) to the

standards devised by the US Supreme Court in determining the validity or extent of restrictive regulations

impinging on the freedoms of the mind, then the O'Brien standard is hardly appropriate because the

standard devised in O'Brien only applies if the State's regulation is not related to communicative conduct. If

a relationship exists, a more demanding standard is applied. ITScAE

MENDOZA, J., concurring:

1. POLITICAL LAW; STATE; FLAG SALUTE; NO COMPELLING REASON FOR RESORTING TO COERCION.

In determining the validity of compulsory flag salute, we must determine which of these polar principles

exerts a greater pull. But unlike the refusal to pay taxes or to submit to compulsory vaccination, the refusal

to salute the flag threatens no such dire consequences to the life or health of the State. Consequently, there

is no compelling reason for resorting to compulsion or coercion to achieve the purpose for which flag salute

is instituted. On the other hand, compelling flag salute cannot be likened to compelling members of a

religious sect to bow down before a graven image. It trivializes great principles to assimilate compulsory

flag salute to a form of command to worship strange idols not only because the flag is not a religious

symbol but also because the salute required involves nothing more than standing at attention or placing

one's right hand over the right breast as the National Anthem is played and of raising the right hand as the

pledge of allegiance to the flag is recited. In sum compulsory flag salute violates the Constitution not

because the aim of the exercise is doubtful but because the means employed for accomplishing it is not

permitted. Legitimate ends cannot be pursued by methods which violate fundamental freedoms when the

ends may be achieved by rational ones.

2. ID.; ID.; WITHOUT POWER TO COMPEL SALUTE TO THE FLAG. It is noteworthy that while the

Constitution provides for the national flag, it does not give the State the power to compel a salute to the

flag. DIHETS

3. CONSTITUTIONAL LAW; BILL OF RIGHTS; FREEDOM OF RELIGION; FLAG, NOT AN IMAGE BUT A

SECULAR SYMBOL. The flag is not an image but a secular symbol. To regard it otherwise because a

religious minority regards it so would be to put in question many regulations that the State may

constitutionally enact or measures which it may adopt to promote civic virtues which the Constitution itself

enjoins the State to promote.

R E S O L U T I O N

KAPUNAN, J p:

The State moves for a reconsideration of our decision dated March 1, 1993 granting private respondents'

petition for certiorari and prohibition and annulling the expulsion orders issued by the public respondents

therein on the ground that the said decision created an exemption in favor of the members of the religious

sect, the Jehovah's Witnesses, in violation of the "Establishment Clause" of the Constitution. The Solicitor

General, on behalf of the public respondent, furthermore contends that:

The accommodation by this Honorable Court to a demand for special

treatment in favor of a minority sect even on the basis of a claim of religious

freedom may be criticized as granting preference to the religious beliefs of

said sect in violation of the "non-establishment guarantee" provision of the

Constitution. Surely, the decision of the Court constitutes a special favor

which immunizes religious believers such as Jehovah's Witnesses to the law

and the DECS rules and regulations by interposing the claim that the

conduct required by law and the rules and regulation (sic) are violative of

their religious beliefs. The decision therefore is susceptible to the very

criticism that the grant of exemption is a violation of the non-

establishment" provision of the Constitution.

Furthermore, to grant an exemption to a specific religious minority poses a

risk of collision course with the "equal protection of the laws" clause in

respect of the non-exempt, and, in public schools, a collision course with

the "non-establishment guarantee." cdtai

Additionally the public respondent insists that this Court adopt a "neutral stance" by reverting to its holding

in Gerona declaring the flag as being devoid of any religious significance. He stresses that the issue here is

not curtailment of religious belief but regulation of the exercise of religious belief. Finally, he maintains that

the State's interests in the case at bench are constitutional and legal obligations to implement the law and

the constitutional mandate to inculcate in the youth patriotism and nationalism and to encourage their

involvement in public and civic affairs, referring to the test devised by the United States Supreme Court in

U.S. vs. O'Brien. 1

II

All the petitioners in the original case 2 were minor schoolchildren, and members of the sect, Jehovah's

Witnesses (assisted by their parents) who were expelled from their classes by various public school

authorities in Cebu for refusing to salute the flag, sing the national anthem and recite the patriotic pledge

as required by Republic Act No. 1265 of July 11, 1955 and by Department Order No. 8, dated July 21,

1955 issued by the Department of Education. Aimed primarily at private educational institutions which did

not observe the flag ceremony exercises, Republic Act No. 1265 penalizes all educational institutions for

failure or refusal to observe the flag ceremony with public censure on first offense and cancellation of the

recognition or permit on second offense.

The implementing regulations issued by the Department of Education thereafter detailed the manner of

observance of the same. Immediately pursuant to these orders, school officials in Masbate expelled children

belonging to the sect of the Jehovah's Witnesses from school for failing or refusing to comply with the flag

ceremony requirement. Sustaining these expulsion orders, this Court in the 1959 case of Gerona vs.

Secretary of Education 3 held that:

The flag is not an image but a symbol of the Republic of the Philippines, an emblem of national sovereignty,

of national unity and cohesion and of freedom and liberty which it and the Constitution guarantee and

protect. Considering the complete separation of church and state in our system of government, the flag is

utterly devoid of any religious significance. Saluting the flag consequently does not involve any religious

ceremony. . . . .

After all, the determination of whether a certain ritual is or is not a religious ceremony must rest with the

courts. It cannot be left to a religious group or sect, much less to a follower of said group or sect; otherwise,

there would be confusion and misunderstanding for there might be as many interpretations and meanings

to be given to a certain ritual or ceremony as there are religious groups or sects or followers.

Upholding religious freedom as a fundamental right deserving the "highest priority and amplest protection

among human rights," this Court, in Ebralinag vs Division Superintendent of Schools of Cebu 4 re-examined

our over two decades-old decision in Gerona and reversed expulsion orders made by the public

respondents therein as violative of both the free exercise of religion clause and the right of citizens to

education under the 1987 Constitution. 5

From our decision of March 1, 1993, the public respondents filed a motion for reconsideration on grounds

hereinabove stated. After a careful study of the grounds adduced in the government's Motion For

Reconsideration of our original decision, however, we find no cogent reason to disturb our earlier ruling.

The religious convictions and beliefs of the members of the religious sect, the Jehovah's Witnesses are

widely known and are equally widely disseminated in numerous books, magazines, brochures and leaflets

distributed by their members in their house to house distribution efforts and in many public places. Their

refusal to render obeisance to any form or symbol which smacks of idolatry is based on their sincere belief

in the biblical injunction found in Exodus 20:4, 5, against worshipping forms or idols other than God

himself. The basic assumption in their universal refusal to salute the flags of the countries in which they are

found is that such a salute constitutes an act of religious devotion forbidden by God's law. This assumption,

while "bizarre" to others is firmly anchored in several biblical passages. 6

And yet, while members of Jehovah's Witnesses, on the basis of religious convictions, refuse to perform an

act (or acts) which they consider proscribed by the Bible, they contend that such refusal should not be taken

to indicate disrespect for the symbols of the country or evidence that they are wanting in patriotism and

nationalism. They point out that as citizens, they have an excellent record as law abiding members of

society even if they do not demonstrate their refusal to conform to the assailed orders by overt acts of

conformity. On the contrary, they aver that they show their respect through less demonstrative methods

manifesting their allegiance, by their simple obedience to the country's laws, 7 by not engaging in anti-

government activities of any kind, 8 and by paying their taxes and dues to society a self-sufficient members

of the community. 9 While they refuse to salute the flag, they are willing to stand quietly and peacefully at

attention, hands on their side, in order not to disrupt the ceremony or disturb those who believe differently.

10

The religious beliefs, practices and convictions of the member of the sect as a minority are bound to be

seen by others as odd and different and at divergence with the complex requirements of contemporary

societies, particularly those societies which require certain practices as manifestations of loyalty and

patriotic behavior. Against those who believe that coerced loyalty and unity are mere shadows of patriotism,

the tendency to exact "a hydraulic insistence on conformity to majoritarian standards," 11 is seductive to

the bureaucratic mindset as a shortcut to patriotism.

No doubt, the State possesses what the Solicitor General describes as the responsibility "to inculcate in the

minds of the youth the values of patriotism and nationalism and to encourage the involvement in public and

civic affairs." The teaching of these values ranks at the very apex of education's "high responsibility" of

shaping up the minds of the youth in those principles which would mold them into responsible and

productive members of our society. However, the government's interest in molding the young into patriotic

and civic spirited citizens is "not totally free from a balancing process" 12 when it intrudes into other

fundamental rights such as those specifically protected by the Free Exercise Clause, the constitutional right

to education and the unassailable interest of parents to guide the religious upbringing of their children in

accordance with the dictates of their conscience and their sincere religious beliefs. 13 Recognizing these

values, Justice Carolina Grio-Aquino, the writer of the original opinion, underscored that a generation of

Filipinos which cuts its teeth on the Bill of Rights would find abhorrent the idea that one may be compelled,

on pain of expulsion, to salute the flag, sing the national anthem and recite the patriotic pledge during a

flag ceremony. 14 "This coercion of conscience has no place in a free society." 15

The State's contentions are therefore, unacceptable, for no less fundamental than the right to take part is

the right to stand apart. 16 In the context of the instant case, the freedom of religion enshrined in the

Constitution should be seen as the rule, not the exception.. To view the constitutional guarantee in the

manner suggested by the petitioners would be to denigrate the status of a preferred freedom and to

relegate it to the level of an abstract principle devoid of any substance and meaning in the lives of those for

whom the protection is addressed. As to the contention that the exemption accorded by our decision

benefits a privileged few, it is enough to re-emphasize that "the constitutional protection of religious

freedom terminated disabilities, it did not create new privileges. It gave religious equality, not civil

immunity." 17 The essence of the free exercise clause is freedom from conformity to religious dogma, not

freedom from conformity to law because of religious dogma. 18 Moreover, the suggestion implicit in the

State's pleadings to the effect that the flag ceremony requirement would be equally and evenly applied to

all Citizens regardless of sect or religion and does not thereby discriminate against any particular sect or

denomination escapes the fact that "[a] regulation, neutral on its face, may in its application, nonetheless

offend the constitutional requirement for governmental neutrality if it unduly burdens the free exercise of

religion." 19

III

The ostensible interest shown by petitioners in preserving the flag as the symbol of the nation appears to

be integrally related to petitioner's disagreement with the message conveyed by the refusal of members of

the Jehovah's Witness sect to salute the flag or participate actively in flag ceremonies on religious grounds.

20 Where the governmental interest clearly appears to be unrelated to the suppression of an idea, a

religious doctrine or practice or an expression or form of expression, this Court will not find it difficult to

sustain a regulation. However, regulations involving this area are generally held against the most exacting

standards, and the zone of protection accorded by the Constitution cannot be violated, except upon a

showing of a clear and present danger of a substantive evil which the state has a right to protect. 21 Stated

differently, in the case of a regulation which appears to abridge a right to which the fundamental law

accords high significance it is the regulation, not the act (or refusal to act), which is the exception and which

requires the court's strictest scrutiny. In the case at bench, the government has not shown that refusal to do

the acts of conformity exacted by the assailed orders, which respondents point out attained legislative

cachet in the Administrative Code of 1987, would pose a clear and present danger of a danger so serious

and imminent, that it would prompt legitimate State intervention.

In a case involving the Flag Protection Act of 1989, the U.S. Supreme Court held that the "State's asserted

interest in preserving the flag as a symbol of nationhood and national unity was an interest related to the

suppression of free expression . . . because the State's concern with protecting the flag's symbolic meaning

is implicated only when a person's treatment of the flag communicates some message." 22 While the very

concept of ordered liberty precludes this Court from allowing every individual to subjectively define his own

standards on matters of conformity in which society, as a whole has important interests, the records of the

case and the long history of flag salute cases abundantly supports the religious quality of the claims

adduced by the members of the sect Jehovah's Witnesses. Their treatment of flag as a religious symbol is

well-founded and well-documented and is based on grounds religious principle. The message conveyed by

their refusal to participate in the flag ceremony is religious, shared by the entire community of Jehovah's

Witnesses and is intimately related to their theocratic beliefs and convictions. The subsequent expulsion of

members of the sect on the basis of the regulations assailed in the original petitions was therefore clearly

directed against religious practice. It is obvious that the assailed orders and memoranda would gravely

endanger the free exercise of the religious beliefs of the members of the sect and their minor children. LLjur

Furthermore, the view that the flag is not a religious but a neutral, secular symbol expresses a majoritarian

view intended to stifle the expression of the belief that an act of saluting the flag might sometimes be to

some individuals so offensive as to be worth their giving up another constitutional right the right to

education. Individuals or groups of individuals get from a symbol the meaning they put to it. 23 Compelling

members of a religious sect to believe otherwise on the pain of denying minor children the right to an

education is a futile and unconscionable detour towards instilling virtues of loyalty and patriotism which are

best instilled and communicated by painstaking and non-coercive methods. Coerced loyalties, after all, only

serve to inspire the opposite. The methods utilized to impose them breed resentment and dissent. Those

who attempt to coerce uniformity of sentiment soon find out that the only path towards achieving unity is

by way of suppressing dissent. 24 In the end, such attempts only find the "unanimity of the graveyard." 25

To the extent to which members of the Jehovah's Witnesses sect assiduously pursue their belief in the flag's

religious symbolic meaning, the State cannot, without thereby transgressing constitutionally protected

boundaries, impose the contrary view on the pretext of sustaining a policy designed to foster the

supposedly far-reaching goal of instilling patriotism among the youth. While conceding to the idea

adverted to by the Solicitor General that certain methods of religious expression may be prohibited 26 to

serve legitimate societal purposes, refusal to participate in the flag ceremony hardly constitutes a form of

religious expression so offensive and noxious as to prompt legitimate State intervention. It is worth

repeating that the absence of a demonstrable danger of a kind which the State is empowered to protect

militates against the extreme disciplinary methods undertaken by school authorities in trying to enforce

regulations designed to compel attendance in flag ceremonies. Refusal of the children to participate in the

flag salute ceremony would not interfere with or deny the rights of other school children to do so. It bears

repeating that their absence from the ceremony hardly constitutes a danger so grave and imminent as to

warrant the state's intervention.

Finally, the respondents' insistence on the validity of the actions taken by the government on the basis of

their averment that "a government regulation of expressive conduct is sufficiently justified if it is within the

constitutional power of the government (and) furthers an important and substantial government interest" 27

misses the whole point of the test devised by the United States Supreme Court in O'Brien, cited by

respondent, because the Court therein was emphatic in stating that "the government interest (should be)

unrelated to the suppression of free expression." We have already stated that the interest in regulation in

the case at bench was clearly related to the suppression of an expression directly connected with the

freedom of religion and that respondents have not shown to our satisfaction that the restriction was

prompted by a compelling interest in public order which the state has a right to protect. Moreover, if we

were to refer (as respondents did by referring to the test in O'Brien) to the standards devised by the US

Supreme Court in determining the validity or extent of restrictive regulations impinging on the freedoms of

the mind, then the O'Brien standard is hardly appropriate because the standard devised in O'Brien only

applies if the State's regulation is not related to communicative conduct. If a relationship exists, a more

demanding standard is applied. 28

The responsibility of inculcating the values of patriotism, nationalism, good citizenship, and moral

uprightness is a responsibility shared by the State with parents and other societal institutions such as

religious sects and denominations. The manner in which such values are demonstrated in a plural society

occurs in ways so variable that government cannot make claims to the exclusivity of its methods of

inculcating patriotism so all-encompassing in scope as to leave no room for appropriate parental or

religious influences. Provided that those influences do not pose a clear and present danger of a substantive

evil to society and its institutions, expressions of diverse beliefs, no matter how upsetting they may seem to

the majority, are the price we pay for the freedoms we enjoy.

WHEREFORE, premises considered, the instant Motion is hereby DENIED.

SO ORDERED.

Narvasa, C.J., Regalado, Davide, Jr., Romero, Bellosillo, Melo, Puno, Vitug, Francisco, and Hermosisima,

Jr., JJ., concur.

Mendoza, J., see concurring opinion.

Padilla, J., I reiterate my Separate Opinion in G.R. No. 95770 (Ebralinag vs. The Division Superintendent of

Schools of Cebu), 1 March 1993, 219 SCRA 276.

Panganiban, J., took no part.

Separate Opinions

MENDOZA, J., concurring:

The value of the national flag as a symbol of national unity is not in question in this case. The issue rather is

whether it is permissible to compel children in the Nation's schools to salute the flag as a means of

promoting nationhood considering that their refusal to do so is grounded on a religious belief.

Compulsory flag salute lies in a continuum, at one end of which is the obligation to pay taxes and, at the

other, a compulsion to bow down before a graven image. Members of a religious sect cannot refuse to pay

taxes, 1 render military service, 2 submit to vaccination 3 or give their children elementary school education

4 on the ground of conscience. But public school children may not be compelled to attend religious

instruction 5 or recite prayers or join in bible reading before the opening of classes in such schools. 6

In determining the validity of compulsory flag salute, we must determine which of these polar principles

exerts a greater pull. The imposition of taxes is justified because, unless support for the government can be

exacted, the existence of the State itself may well be endangered. The compulsory vaccination of children is

justified because unless the State can compel compliance with vaccination program there is danger that a

disease will spread. But unlike the refusal to pay taxes or to submit to compulsory vaccination, the refusal to

salute the flag threatens no such dire consequences to the life or health of the State. Consequently, there is

no compelling reason for resorting to compulsion or coercion to achieve the purpose for which flag salute is

instituted.

Indeed schools are not like army camps where the value of discipline justifies requiring a salute to the flag.

Schools are places where diversity and spontaneity are valued as much as personal discipline is. They are

places for the nurturing of ideals and values, not through compulsion or coercion but through persuasion,

because thought control is a negation of the very values which the educational system seeks to promote.

Persuasion and not persecution is the means for winning the allegiance of free men. That is why the

Constitution provides that the development of moral character and the cultivation of civic spirit are to be

pursued through education that includes a study of the Constitution, an appreciation of the role of national

heroes in historical development, teaching the rights and duties of citizenship and, at the option of parents

and guardians, religious instruction to be taught by instructors designated by religious authorities of the

religion to which they belong. It is noteworthy that while the Constitution provides for the national flag, 7 it

does not give the State the power to compel a salute to the flag. dctai

On the other hand, compelling flag salute cannot be likened to compelling members of a religious sect to

bow down before a graven image. The flag is not an image but a secular symbol. To regard it otherwise

because a religious minority regards it so would be to put in question many regulations that the State may

constitutionally enact or measures which it may adopt to promote civic virtues which the Constitution itself

enjoins the State to promote. 8

It trivializes great principles to assimilate compulsory flag salute to a form of command to worship strange

idols not only because the flag is not a religious symbol but also because the salute required involves

nothing more than standing at attention or placing one's right hand over the right breast as the National

Anthem is played and of raising the right hand as the following pledge is recited:

Ako'y nanunumpang magtatapat sa watawat ng Pilipinas at sa Republikang

kanyang kinakatawan isang bansang nasa kalinga ng Dios buo at hindi

mahahati, na may kalayaan at katarungan para sa lahat.

(I pledge allegiance to the flag and to the nation for which it stands one

nation under God indivisible, with liberty and justice for all.)

In sum, compulsory flag salute violates the Constitution not because the aim of the exercise is doubtful but

because the means employed for accomplishing it is not permitted. Legitimate ends cannot be pursued by

methods which violate fundamental freedoms when the ends may be achieved by rational ones.

For this reason I join in holding that compulsory flag salute is unconstitutional.

Footnotes

1. "To this end," the motion states, "a government regulation of expressive religious conduct which

debases the constitutional mandate for citizenship training is justifiable. As succinctly outlined

in one U.S. case:

A government regulation of expressive conduct is sufficiently justified if it is within the Constitutional

power of this government; it furthers an important or substantial governmental interest; if the

governmental interest is unrelated to the suppression of free expression and if the incidental

restriction on alleged First Amendment freedom is greater than is essential to the furtherance

of that interest.( United States v. O'Brien, 391 U.S. 367)"

2. G.R. No. 95770 and G.R. No. 95887, March 1, 1993, 219 SCRA 256 (1993).

3. 106 Phil. 2 (1959).

4. Supra, note 2.

5. Id. at 272-273 (1993).

6. See, for e.g. Daniel 3:1-30.

7. Rollo, p. 8.

8. Id.

9. Id.

10. Rollo, p. 10.

11. State of Wisconsin v. Yoder, 40 LW 4476 (1972).

12. Id.

13. Id., See also, Pierce v. Society of Sisters, 268 U.S. 510, 534 (1925).

14. Ebralinag, supra at 270.

15. Id. at 275, Cruz J. (Concurring).

16. L. TRIBE, GOD SAVE THIS HONORABLE COURT: HOW THE CHOICE OF SUPREME COURT

JUSTICES SHAPES OUR HISTORY, 31(1985).

17. See supra note 15, citing Justice Frankfurter.

18. Id.

19. Sherbert v. Verner, 374 U.S. 398 (1963).

20. For instance, the Motion for Reconsideration characterizes the practices and observations of the sect

as "bizarre," Rollo, p. 229, "seditious" Id., p. 240 and "anti-social" Id. (italics supplied). In

making these points, the Motion makes this tongue-in-cheek observation: "Because of their

religious conviction that they "are not part of this world, and being allegedly concerned

"about the adverse effect that the world's influence can have on our children," the Jehovah's

Witnesses ask that their children . . . be exempted from participating in almost all school

activities and social function (sic) which, as they pointed out below are contrary to Bible (sic)

principles. "Id. The statement, "not part of this world" was deliberately taken out of context.

Here is what the paragraph from the sect's manual says:

As one might expect, this view of the future also had a significant effect on the first Christians. It caused

them to be a distinctive people, separate from the world. As the historian E.G. Hardy noted in

his book Christianity and the Roman Government: "The Christians were strangers and pilgrims

in the world around them; their citizenship was in heaven; the kingdom to which they looked

was not part of this world. The consequent want of interest in public affairs came thus from the

outset to be a noticeable feature in Christianity. Annex "B", p. 7.

21. West Virginia v. Barnette, 319 US 624 at 339 (1942).

22. U.S. v. Eichman, 496 US 310, 313; 110 L ed 2d 287 (1990).

23. Supra, note 4.

24. Id., at 640.

25. Id., at 641. "Recognizing that the right to differ is the centerpiece of our First Amendment . . . a

government cannot mandate by fiat a feeling of unity in its citizens. Therefore, that very same

government cannot carve out a symbol of unity and prescribe a set of approved messages to

be associated with that symbol when it cannot mandate the status or feeling the symbol

purports to represent." See, Texas v. Johnson, 491 US 397 at 400 (1989).

26. Raising the "Children of God" caper, the Solicitor General's brief states:

How about the children of God, also known as Future Visions of Family which engages in free love and

sex sharing among its members by way of obedience to the biblical injunction "to love your

neighbor and love yourself " as interpreted by its founder, Moses David Berg, through his

writings entitled "The Law of Love" and "Growing in Faith." Despite the crusades of Cardinal

Sin and the Aquino government, this self-styled sex cult has gain (sic) foothold and spread in

numbers in this country, offering free sex, cutely termed as "flirty fishing to win people for the

Lord." Will this Honorable Court also recognize and allow their communal free love and sex

orgies to continue unabated as part of their religious belief and protected by their

constitutional right of freedom of religion, thereby sideswiping the present Government's

program to prevent the spread of venereal diseases and the dreaded AIDS through the use of

condoms?" Rollo, p. 245.

27. Supra, note 1.

28. Referring to the test devised in O'Brien the U.S. Supreme Court in Texas v. Johnson, supra, held: "We

must first determine whether Johnson's burning of the flag constituted expressive conduct

permitting him to invoke the First Amendment in challenging his conviction. If his conduct was

expressive, we next decide whether the State's regulation is related to the suppression of free

expression. If the state's regulation is not related to expression, then the less stringent

standard we announced in United States vs. O'Brien for regulations of noncommunicative

conduct controls. If it is then we are outside O'Brien's test, and we must ask whether this

interest justifies Johnson's conviction under a more demanding standard. Id. at 403.

MENDOZA, J., concurring:

1. United States v. Lee, 455 U.S. 25 (1982).

2. Gillette v. United States, 401 U.S. 437 (1971); Hamilton v. Regents of the University of California, 293

U.S. 245 (1934). Cf. People v. Lagman and People v. Sosa, 66 Phil. 13 (1938).

3. Jacobson v. Massachusetts, 197 U.S. 11 (1904); People v. Abad Lopez, 62 Phil. 835 (1936); Lorenzo v.

Director, 50 Phil. 595 (1927).

4. Wisconsin v. Yoder, 406 U.S. 205 (1972), PHIL. CONST., Art. XIV, 2 (2) provides that "elementary

education is compulsory for all children of school age."

5. Art. XIV, 3(3) only provides "for optional religious instruction on public elementary and high

education is compulsory for all children of school age."

6. Engel v. Vitale, 307 U.S. 421 (1962); Abington School Dist. v. Schempp, 374 U.S. 203 (1963); cf.

Wallace v. Jaffree, 472 U.S. 38 (1985).

7. CONST., Art. XVI, 1.

8. See Art. II, 13; Art. XIV, 3 (2).

2012 CD Technologies Asia, Inc. Click here for our Disclaimer and Copyright Notice

Facts:

The petitioners in both (consolidated) cases were expelled from their classes by the

public school authorities in Cebu for refusing to salute the flag, sing the national anthem and

recite the patriotic pledge as required by Republic Act No. 1265

(An Act making flag

ceremony compulsory in all educational institutions)

of July 11, 1955 , and by Department

Order No. 8

(Rules and Regulations for Conducting the Flag Ceremony in All Educational

Institutions)

dated July 21, 1955 of the Department of Education, Culture and Sports (DECS)

making the flag ceremony compulsory in all educational institutions.

Jehovah's Witnesses admitted that they taught their children not to salute the flag,

sing the national anthem, and recite the patriotic pledge for they believe that those are

"acts of worship" or "religious devotion" which they "cannot conscientiously give to anyone

or anything except God". They consider the flag as an image or idol representing the State.

They think the action of the local authorities in compelling the flag salute and pledge

transcends constitutional limitations on the State's power and invades the sphere of the

intellect and spirit which the Constitution protect against official control..

Issue:

Whether or not school children who are members or a religious sect may be expelled

from school for disobedience of R.A. No. 1265 and Department Order No. 8

Held:

No.

Religious freedom is a fundamental right which is entitled to the highest

priority and the amplest protection among human rights, for it involves the

relationship of man to his Creator

The sole justification for a prior restraint or limitation on the exercise of religious

freedom is the existence of a grave and present danger of a character both grave and

imminent, of a serious evil to public safety, public morals, public health or any other

legitimate public interest, that the State has a right (and duty) to prevent." Absent such a

threat to public safety, the expulsion of the petitioners from the schools is not justified.

(Teehankee)

The petitioners further contend that while they do not take part in the compulsory

flag ceremony, they do not engage in "external acts" or behavior that would offend their

countrymen who believe in expressing their love of country through the observance of the

flag ceremony. They quietly stand at attention during the flag ceremony to show their

respect for the right of those who choose to participate in the solemn proceedings. Since

they do not engage in disruptive behavior, there is no warrant for their expulsion.

EN BANC

[A.M. No. P-02-1651. June 22, 2006.]

(formerly OCA I.P.I. No. 00-1021-P)

ALEJANDRO ESTRADA, complainant, vs. SOLEDAD S. ESCRITOR,

respondent.

R E S O L U T I O N

PUNO, J p:

While man is finite, he seeks and subscribes to the Infinite. Respondent Soledad Escritor once again stands

before the Court invoking her religious freedom and her Jehovah God in a bid to save her family united

without the benefit of legal marriage and livelihood. The State, on the other hand, seeks to wield its

power to regulate her behavior and protect its interest in marriage and family and the integrity of the courts

where respondent is an employee. How the Court will tilt the scales of justice in the case at bar will decide

not only the fate of respondent Escritor but of other believers coming to Court bearing grievances on their

free exercise of religion. This case comes to us from our remand to the Office of the Court Administrator on

August 4, 2003. 1

I. THE PAST PROCEEDINGS

In a sworn-letter complaint dated July 27, 2000, complainant Alejandro Estrada requested Judge Jose F.

Caoibes, Jr., presiding judge of Branch 253, Regional Trial Court of Las Pias City, for an investigation of

respondent Soledad Escritor, court interpreter in said court, for living with a man not her husband, and

having borne a child within this live-in arrangement. Estrada believes that Escritor is committing an immoral

act that tarnishes the image of the court, thus she should not be allowed to remain employed therein as it

might appear that the court condones her act. 2 Consequently, respondent was charged with committing

"disgraceful and immoral conduct" under Book V, Title I, Chapter VI, Sec. 46(b)(5) of the Revised

Administrative Code. 3

Respondent Escritor testified that when she entered the judiciary in 1999, she was already a widow, her

husband having died in 1998. 4 She admitted that she started living with Luciano Quilapio, Jr. without the

benefit of marriage more than twenty years ago when her husband was still alive but living with another

woman. She also admitted that she and Quilapio have a son. 5 But as a member of the religious sect known

as the Jehovah's Witnesses and the Watch Tower and Bible Tract Society, respondent asserted that their

conjugal arrangement is in conformity with their religious beliefs and has the approval of her congregation.

6 In fact, after ten years of living together, she executed on July 28, 1991, a "Declaration of Pledging

Faithfulness." 7

For Jehovah's Witnesses, the Declaration allows members of the congregation who have been abandoned

by their spouses to enter into marital relations. The Declaration thus makes the resulting union moral and

binding within the congregation all over the world except in countries where divorce is allowed. As laid out

by the tenets of their faith, the Jehovah's congregation requires that at the time the declarations are

executed, the couple cannot secure the civil authorities' approval of the marital relationship because of

legal impediments. Only couples who have been baptized and in good standing may execute the

Declaration, which requires the approval of the elders of the congregation. As a matter of practice, the

marital status of the declarants and their respective spouses' commission of adultery are investigated before

the declarations are executed. 8 Escritor and Quilapio's declarations were executed in the usual and

approved form prescribed by the Jehovah's Witnesses, 9 approved by elders of the congregation where

the declarations were executed, 10 and recorded in the Watch Tower Central Office. 11

Moreover, the Jehovah's congregation believes that once all legal impediments for the couple are lifted,

the validity of the declarations ceases, and the couple should legalize their union. In Escritor's case,

although she was widowed in 1998, thereby lifting the legal impediment to marry on her part, her mate was

still not capacitated to remarry. Thus, their declarations remained valid. 12 In sum, therefore, insofar as the

congregation is concerned, there is nothing immoral about the conjugal arrangement between Escritor and

Quilapio and they remain members in good standing in the congregation.

By invoking the religious beliefs, practices and moral standards of her congregation, in asserting that her

conjugal arrangement does not constitute disgraceful and immoral conduct for which she should be held

administratively liable, 13 the Court had to determine the contours of religious freedom under Article III,

Section 5 of the Constitution, which provides, viz:

Sec. 5. No law shall be made respecting an establishment of religion, or

prohibiting the free exercise thereof. The free exercise and enjoyment of

religious profession and worship, without discrimination or preference, shall

forever be allowed. No religious test shall be required for the exercise of

civil or political rights.

A. RULING

In our decision dated August 4, 2003, after a long and arduous scrutiny into the origins and development of

the religion clauses in the United States (U.S.) and the Philippines, we held that in resolving claims involving

religious freedom (1) benevolent neutrality or accommodation, whether mandatory or permissive, is the

spirit, intent and framework underlying the religion clauses in our Constitution; and (2) in deciding

respondent's plea of exemption based on the Free Exercise Clause (from the law with which she is

administratively charged), it is the compelling state interest test, the strictest test, which must be applied.

14

Notwithstanding the above rulings, the Court could not, at that time, rule definitively on the ultimate issue

of whether respondent was to be held administratively liable for there was need to give the State the

opportunity to adduce evidence that it has a more "compelling interest" to defeat the claim of the

respondent to religious freedom. Thus, in the decision dated August 4, 2003, we remanded the

complaint to the Ofce of the Court Administrator (OCA), and ordered the Ofce of the Solicitor

General (OSG) to intervene in the case so it can:

(a) examine the sincerity and centrality of respondent's claimed

religious belief and practice;

(b) present evidence on the state's "compelling interest" to override

respondent's religious belief and practice; and

(c) show that the means the state adopts in pursuing its interest is the

least restrictive to respondent's religious freedom. 15

It bears stressing, therefore, that the residual issues of the case pertained NOT TO WHAT APPROACH THIS

COURT SHOULD TAKE IN CONSTRUING THE RELIGION CLAUSES, NOR TO THE PROPER TEST

APPLICABLE IN DETERMINING CLAIMS OF EXEMPTION BASED ON FREEDOM OF RELIGION. These

issues have already been ruled upon prior to the remand, and constitute "the law of the case" insofar

as they resolved the issues of which framework and test are to be applied in this case, and no motion

for its reconsideration having been led. 16 The only task that the Court is left to do is to determine

whether the evidence adduced by the State proves its more compelling interest. This issue involves a pure

question of fact.

B. LAW OF THE CASE

Mr. Justice Carpio's insistence, in his dissent, in attacking the ruling of this case interpreting the religious

clauses of the Constitution, made more than two years ago, is misplaced to say the least. Since neither the

complainant, respondent nor the government has filed a motion for reconsideration assailing this ruling, the

same has attained finality and constitutes the law of the case. Any attempt to reopen this final ruling

constitutes a crass contravention of elementary rules of procedure. Worse, insofar as it would overturn the

parties' right to rely upon our interpretation which has long attained finality, it also runs counter to

substantive due process.

Be that as it may, even assuming that there were no procedural and substantive infirmities in Mr. Justice

Carpio's belated attempts to disturb settled issues, and that he had timely presented his arguments, the

results would still be the same.

We review the highlights of our decision dated August 4, 2003.

1. OLD WORLD ANTECEDENTS

In our August 4, 2003 decision, we made a painstaking review of Old World antecedents of the religion

clauses, because "one cannot understand, much less intelligently criticize the approaches of the courts and

the political branches to religious freedom in the recent past in the United States without a deep

appreciation of the roots of these controversies in the ancient and medieval world and in the American

experience." 17 We delved into the conception of religion from primitive times, when it started out as the

state itself, when the authority and power of the state were ascribed to God. 18 Then, religion developed

on its own and became superior to the state, 19 its subordinate, 20 and even becoming an engine of state

policy. 21

We ascertained two salient features in the review of religious history: First, with minor exceptions, the

history of church-state relationships was characterized by persecution, oppression, hatred, bloodshed, and

war, all in the name of the God of Love and of the Prince of Peace. Second, likewise with minor exceptions,

this history witnessed the unscrupulous use of religion by secular powers to promote secular purposes and

policies, and the willing acceptance of that role by the vanguards of religion in exchange for the favors and

mundane benefits conferred by ambitious princes and emperors in exchange for religion's invaluable

service. This was the context in which the unique experiment of the principle of religious freedom and

separation of church and state saw its birth in American constitutional democracy and in human history. 22

Strictly speaking, the American experiment of freedom and separation was not translated in the First

Amendment. That experiment had been launched four years earlier, when the founders of the republic

carefully withheld from the new national government any power to deal with religion. As James Madison

said, the national government had no "jurisdiction" over religion or any "shadow of right to intermeddle"

with it. 23

The omission of an express guaranty of religious freedom and other natural rights, however, nearly

prevented the ratification of the Constitution. The restriction had to be made explicit with the adoption of

the religion clauses in the First Amendment as they are worded to this day. Thus, the First Amendment did

not take away or abridge any power of the national government; its intent was to make express the absence

of power. 24 It commands, in two parts (with the first part usually referred to as the Establishment Clause

and the second part, the Free Exercise Clause), viz:

Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion or

prohibiting the free exercise thereof. 25

The Establishment and Free Exercise Clauses, it should be noted, were not designed to serve contradictory

purposes. They have a single goal to promote freedom of individual religious beliefs and practices. In

simplest terms, the Free Exercise Clause prohibits government from inhibiting religious beliefs with

penalties for religious beliefs and practice, while the Establishment Clause prohibits government from

inhibiting religious belief with rewards for religious beliefs and practices. In other words, the two religion

clauses were intended to deny government the power to use either the carrot or the stick to influence

individual religious beliefs and practices. 26

In sum, a review of the Old World antecedents of religion shows the movement of establishment of religion

as an engine to promote state interests, to the principle of non-establishment to allow the free exercise of

religion. DICSaH

2. RELIGION CLAUSES IN THE U.S. CONTEXT

The Court then turned to the religion clauses' interpretation and construction in the United States, not

because we are bound by their interpretation, but because the U.S. religion clauses are the precursors to

the Philippine religion clauses, although we have significantly departed from the U.S. interpretation as will

be discussed later on.

At the outset, it is worth noting that American jurisprudence in this area has been volatile and fraught with

inconsistencies whether within a Court decision or across decisions. For while there is widespread

agreement regarding the value of the First Amendment religion clauses, there is an equally broad

disagreement as to what these clauses specifically require, permit and forbid. No agreement has been

reached by those who have studied the religion clauses as regards its exact meaning and the paucity of

records in the U.S. Congress renders it difficult to ascertain its meaning. 27

U.S. history has produced two identifiably different, even opposing, strains of jurisprudence on the religion

clauses. First is the standard of separation, which may take the form of either (a) strict separation or (b)

the tamer version of strict neutrality or separation, or what Mr. Justice Carpio refers to as the second

theory of governmental neutrality. Although the latter form is not as hostile to religion as the former, both

are anchored on the Jeffersonian premise that a "wall of separation" must exist between the state and the

Church to protect the state from the church. 28 Both protect the principle of church-state separation with a

rigid reading of the principle. On the other hand, the second standard, the benevolent neutrality or

accommodation, is buttressed by the view that the wall of separation is meant to protect the church from

the state. A brief review of each theory is in order.

a. Strict Separation and Strict Neutrality/Separation

The Strict Separationist believes that the Establishment Clause was meant to protect the state from the

church, and the state's hostility towards religion allows no interaction between the two. According to this

Jeffersonian view, an absolute barrier to formal interdependence of religion and state needs to be erected.

Religious institutions could not receive aid, whether direct or indirect, from the state. Nor could the state

adjust its secular programs to alleviate burdens the programs placed on believers. 29 Only the complete

separation of religion from politics would eliminate the formal influence of religious institutions and provide

for a free choice among political views, thus a strict "wall of separation" is necessary. 30

Strict separation faces difficulties, however, as it is deeply embedded in American history and

contemporary practice that enormous amounts of aid, both direct and indirect, flow to religion from

government in return for huge amounts of mostly indirect aid from religion. 31 For example, less than

twenty-four hours after Congress adopted the First Amendment's prohibition on laws respecting an

establishment of religion, Congress decided to express its thanks to God Almighty for the many blessings

enjoyed by the nation with a resolution in favor of a presidential proclamation declaring a national day of

Thanksgiving and Prayer. 32 Thus, strict separationists are caught in an awkward position of claiming a

constitutional principle that has never existed and is never likely to. 33

The tamer version of the strict separationist view, the strict neutrality or separationist view, (or, the

governmental neutrality theory) finds basis in Everson v. Board of Education, 34 where the Court

declared that Jefferson's "wall of separation" encapsulated the meaning of the First Amendment. However,

unlike the strict separationists, the strict neutrality view believes that the "wall of separation" does not

require the state to be their adversary. Rather, the state must be neutral in its relations with groups of

religious believers and non-believers. "State power is no more to be used so as to handicap religions than it

is to favor them." 35 The strict neutrality approach is not hostile to religion, but it is strict in holding that

religion may not be used as a basis for classification for purposes of governmental action, whether the

action confers rights or privileges or imposes duties or obligations. Only secular criteria may be the basis of

government action. It does not permit, much less require, accommodation of secular programs to religious

belief. 36

The problem with the strict neutrality approach, however, is if applied in interpreting the Establishment

Clause, it could lead to a de facto voiding of religious expression in the Free Exercise Clause. As pointed

out by Justice Goldberg in his concurring opinion in Abington School District v. Schempp, 37 strict

neutrality could lead to "a brooding and pervasive devotion to the secular and a passive, or even active,

hostility to the religious" which is prohibited by the Constitution. 38 Professor Laurence Tribe commented

in his authoritative treatise, viz:

To most observers. . . strict neutrality has seemed incompatible with the

very idea of a free exercise clause. The Framers, whatever specific

applications they may have intended, clearly envisioned religion as

something special; they enacted that vision into law by guaranteeing the

free exercise of religion but not, say, of philosophy or science. The strict

neutrality approach all but erases this distinction. Thus it is not surprising

that the [U.S.] Supreme Court has rejected strict neutrality, permitting and

sometimes mandating religious classifications. 39

Thus, the dilemma of the separationist approach, whether in the form of strict separation or strict

neutrality, is that while the Jeffersonian wall of separation "captures the spirit of the American ideal of

church-state separation," in real life, church and state are not and cannot be totally separate. This is all the

more true in contemporary times when both the government and religion are growing and expanding their

spheres of involvement and activity, resulting in the intersection of government and religion at many points.

40

b. Benevolent Neutrality/Accommodation

The theory of benevolent neutrality or accommodation is premised on a different view of the "wall of

separation," associated with Williams, founder of the Rhode Island colony. Unlike the Jeffersonian wall that

is meant to protect the state from the church, the wall is meant to protect the church from the state. 41 This

doctrine was expressed in Zorach v. Clauson, 42 which held, viz:

The First Amendment, however, does not say that in every and all respects

there shall be a separation of Church and State. Rather, it studiously defines

the manner, the specific ways, in which there shall be no concert or union or

dependency one or the other. That is the common sense of the matter.

Otherwise, the state and religion would be aliens to each other hostile,

suspicious, and even unfriendly. Churches could not be required to pay

even property taxes. Municipalities would not be permitted to render

police or fire protection to religious groups. Policemen who helped

parishioners into their places of worship would violate the Constitution.

Prayers in our legislative halls; the appeals to the Almighty in the messages

of the Chief Executive; the proclamations making Thanksgiving Day a

holiday; "so help me God" in our courtroom oaths these and all other

references to the Almighty that run through our laws, our public rituals, our

ceremonies would be flouting the First Amendment. A fastidious atheist or

agnostic could even object to the supplication with which the Court opens

each session: "God save the United States and this Honorable Court."

xxx xxx xxx

We are a religious people whose institutions presuppose a Supreme Being.

We guarantee the freedom to worship as one chooses. . . When the state

encourages religious instruction or cooperates with religious authorities by

adjusting the schedule of public events, it follows the best of our traditions.

For it then respects the religious nature of our people and accommodates

the public service to their spiritual needs. To hold that it may not would be

to find in the Constitution a requirement that the government show a

callous indifference to religious groups. . . But we find no constitutional

requirement which makes it necessary for government to be hostile to

religion and to throw its weight against efforts to widen their effective

scope of religious influence. 43

Benevolent neutrality recognizes that religion plays an important role in the public life of the United States

as shown by many traditional government practices which, to strict neutrality, pose Establishment Clause

questions. Among these are the inscription of "In God We Trust" on American currency; the recognition of

America as "one nation under God" in the official pledge of allegiance to the flag; the Supreme Court's

time-honored practice of opening oral argument with the invocation "God save the United States and this

Honorable Court"; and the practice of Congress and every state legislature of paying a chaplain, usually of

a particular Protestant denomination, to lead representatives in prayer. These practices clearly show the

preference for one theological viewpoint the existence of and potential for intervention by a god over

the contrary theological viewpoint of atheism. Church and government agencies also cooperate in the

building of low-cost housing and in other forms of poor relief, in the treatment of alcoholism and drug

addiction, in foreign aid and other government activities with strong moral dimension. 44

Examples of accommodations in American jurisprudence also abound, including, but not limited to the U.S.

Court declaring the following acts as constitutional: a state hiring a Presbyterian minister to lead the

legislature in daily prayers, 45 or requiring employers to pay workers compensation when the resulting

inconsistency between work and Sabbath leads to discharge; 46 for government to give money to

religiously-affiliated organizations to teach adolescents about proper sexual behavior; 47 or to provide

religious school pupils with books; 48 or bus rides to religious schools; 49 or with cash to pay for state-

mandated standardized tests. 50

(1) Legislative Acts and the Free Exercise Clause

As with the other rights under the Constitution, the rights embodied in the Religion clauses are invoked in

relation to governmental action, almost invariably in the form of legislative acts.

Generally speaking, a legislative act that purposely aids or inhibits religion will be challenged as

unconstitutional, either because it violates the Free Exercise Clause or the Establishment Clause or both.

This is true whether one subscribes to the separationist approach or the benevolent neutrality or

accommodationist approach.

But the more difficult religion cases involve legislative acts which have a secular purpose and general

applicability, but may incidentally or inadvertently aid or burden religious exercise. Though the government

action is not religiously motivated, these laws have a "burdensome effect" on religious exercise.

The benevolent neutrality theory believes that with respect to these governmental actions,

accommodation of religion may be allowed, not to promote the government's favored form of religion, but

to allow individuals and groups to exercise their religion without hindrance. The purpose of

accommodations is to remove a burden on, or facilitate the exercise of, a person's or institution's religion.

As Justice Brennan explained, the "government [may] take religion into account . . . to exempt, when

possible, from generally applicable governmental regulation individuals whose religious beliefs and

practices would otherwise thereby be infringed, or to create without state involvement an atmosphere in

which voluntary religious exercise may flourish." 51 In the ideal world, the legislature would recognize the

religions and their practices and would consider them, when practical, in enacting laws of general

application. But when the legislature fails to do so, religions that are threatened and burdened may turn to

the courts for protection. 52

Thus, what is sought under the theory of accommodation is not a declaration of unconstitutionality of a

facially neutral law, but an exemption from its application or its "burdensome effect," whether by the

legislature or the courts. 53 Most of the free exercise claims brought to the U.S. Court are for exemption,

not invalidation of the facially neutral law that has a "burdensome" effect. 54

(2) Free Exercise Jurisprudence: Sherbert, Yoder and Smith

The pinnacle of free exercise protection and the theory of accommodation in the U.S. blossomed in the

case of Sherbert v. Verner, 55 which ruled that state regulation that indirectly restrains or punishes

religious belief or conduct must be subjected to strict scrutiny under the Free Exercise Clause. 56 According

to Sherbert, when a law of general application infringes religious exercise, albeit incidentally, the state

interest sought to be promoted must be so paramount and compelling as to override the free exercise

claim. Otherwise, the Court itself will carve out the exemption.

In this case, Sherbert, a Seventh Day Adventist, claimed unemployment compensation under the law as her

employment was terminated for refusal to work on Saturdays on religious grounds. Her claim was denied.

She sought recourse in the Supreme Court. In laying down the standard for determining whether the denial

of benefits could withstand constitutional scrutiny, the Court ruled, viz:

Plainly enough, appellee's conscientious objection to Saturday work

constitutes no conduct prompted by religious principles of a kind within the

reach of state legislation. If, therefore, the decision of the South Carolina

Supreme Court is to withstand appellant's constitutional challenge, it must

be either because her disqualication as a beneciary represents no

infringement by the State of her constitutional right of free exercise,

or because any incidental burden on the free exercise of appellant's

religion may be justied by a "compelling state interest in the

regulation of a subject within the State's constitutional power to

regulate. . . ." 57 (emphasis supplied)

The Court stressed that in the area of religious liberty, it is basic that it is not sufcient to merely

show a rational relationship of the substantial infringement to the religious right and a colorable

state interest. "(I)n this highly sensitive constitutional area, '[o]nly the gravest abuses, endangering

paramount interests, give occasion for permissible limitation.'" 58 The Court found that there was no such

compelling state interest to override Sherbert's religious liberty. It added that even if the state could show

that Sherbert's exemption would pose serious detrimental effects to the unemployment compensation fund

and scheduling of work, it was incumbent upon the state to show that no alternative means of regulations

would address such detrimental effects without infringing religious liberty. The state, however, did not

discharge this burden. The Court thus carved out for Sherbert an exemption from the Saturday work

requirement that caused her disqualification from claiming the unemployment benefits. The Court reasoned

that upholding the denial of Sherbert's benefits would force her to choose between receiving benefits and

following her religion. This choice placed "the same kind of burden upon the free exercise of religion as

would a fine imposed against (her) for her Saturday worship." This germinal case of Sherbert firmly

established the exemption doctrine, 59 viz:

It is certain that not every conscience can be accommodated by all the laws of the land; but when general

laws conict with scruples of conscience, exemptions ought to be granted unless some "compelling

state interest" intervenes. ESTCDA

Thus, Sherbert and subsequent cases held that when government action burdens, even inadvertently, a

sincerely held religious belief or practice, the state must justify the burden by demonstrating that the law

embodies a compelling interest, that no less restrictive alternative exists, and that a religious exemption

would impair the state's ability to effectuate its compelling interest. As in other instances of state action

affecting fundamental rights, negative impacts on those rights demand the highest level of judicial scrutiny.

After Sherbert, this strict scrutiny balancing test resulted in court-mandated religious exemptions from

facially-neutral laws of general application whenever unjustified burdens were found. 60

Then, in the 1972 case of Wisconsin v. Yoder, 61 the U.S. Court again ruled that religious exemption was in

order, notwithstanding that the law of general application had a criminal penalty. Using heightened

scrutiny, the Court overturned the conviction of Amish parents for violating Wisconsin compulsory school-

attendance laws. The Court, in effect, granted exemption from a neutral, criminal statute that punished

religiously motivated conduct. Chief Justice Burger, writing for the majority, held, viz:

It follows that in order for Wisconsin to compel school attendance beyond

the eighth grade against a claim that such attendance interferes with the

practice of a legitimate religious belief, it must appear either that the

State does not deny the free exercise of religious belief by its

requirement, or that there is a state interest of sufcient magnitude to

override the interest claiming protection under the Free Exercise

Clause. Long before there was general acknowledgement of the need for

universal education, the Religion Clauses had specially and firmly fixed the

right of free exercise of religious beliefs, and buttressing this fundamental

right was an equally firm, even if less explicit, prohibition against the

establishment of any religion. The values underlying these two provisions

relating to religion have been zealously protected, sometimes even at the

expense of other interests of admittedly high social importance. . .

The essence of all that has been said and written on the subject is that only

those interests of the highest order and those not otherwise served