Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Sps Nuguid Vs CA

Enviado por

Paolo Antonio Escalona0 notas0% acharam este documento útil (0 voto)

38 visualizações6 páginasProperty Case

Título original

Sps Nuguid vs CA

Direitos autorais

© © All Rights Reserved

Formatos disponíveis

PDF, TXT ou leia online no Scribd

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoProperty Case

Direitos autorais:

© All Rights Reserved

Formatos disponíveis

Baixe no formato PDF, TXT ou leia online no Scribd

0 notas0% acharam este documento útil (0 voto)

38 visualizações6 páginasSps Nuguid Vs CA

Enviado por

Paolo Antonio EscalonaProperty Case

Direitos autorais:

© All Rights Reserved

Formatos disponíveis

Baixe no formato PDF, TXT ou leia online no Scribd

Você está na página 1de 6

[G.R. No. 151815.

February 23, 2005]

SPOUSES JUAN NUGUID AND ERLINDA T. NUGUID, petitioners, vs. HON. COURT OF APPEALS AND

PEDRO P. PECSON, respondents.

D E C I S I O N

QUISUMBING, J.:

This is a petition for review on certiorari of the Decision

[1]

dated May 21, 2001, of the Court of

Appeals in CA-G.R. CV No. 64295, which modified the Order dated July 31, 1998 of the Regional Trial

Court (RTC) of Quezon City, Branch 101 in Civil Case No. Q-41470. The trial court ordered the

defendants, among them petitioner herein Juan Nuguid, to pay respondent herein Pedro P. Pecson, the

sum of P1,344,000 as reimbursement of unrealized income for the period beginning November 22, 1993

to December 1997. The appellate court, however, reduced the trial courts award in favor of Pecson

from the said P1,344,000 to P280,000. Equally assailed by the petitioners is the appellate

courts Resolution

[2]

dated January 10, 2002, denying the motion for reconsideration.

It may be recalled that relatedly in our Decision dated May 26, 1995, in G.R. No. 115814,

entitled Pecson v. Court of Appeals, we set aside the decision of the Court of Appeals in CA-G.R. SP No.

32679 and the Order dated November 15, 1993, of the RTC of Quezon City, Branch 101 and remanded

the case to the trial court for the determination of the current market value of the four-door two-storey

apartment building on the 256-square meter commercial lot.

The antecedent facts in this case are as follows:

Pedro P. Pecson owned a commercial lot located at 27 Kamias Road, Quezon City, on which he built

a four-door two-storey apartment building. For failure to pay realty taxes, the lot was sold at public

auction by the City Treasurer of Quezon City to Mamerto Nepomuceno, who in turn sold it for P103,000

to the spouses Juan and Erlinda Nuguid.

Pecson challenged the validity of the auction sale before the RTC of Quezon City in Civil Case No. Q-

41470. In its Decision,

[3]

dated February 8, 1989, the RTC upheld the spouses title but declared that the

four-door two-storey apartment building was not included in the auction sale.

[4]

This was

affirmed in toto by the Court of Appeals and thereafter by this Court, in its Decision

[5]

dated May 25,

1993, in G.R. No. 105360 entitled Pecson v. Court of Appeals.

On June 23, 1993, by virtue of the Entry of Judgment of the aforesaid decision in G.R. No. 105360,

the Nuguids became the uncontested owners of the 256-square meter commercial lot.

As a result, the Nuguid spouses moved for delivery of possession of the lot and the apartment

building.

In its Order

[6]

of November 15, 1993, the trial court, relying upon Article 546

[7]

of the Civil Code,

ruled that the Spouses Nuguid were to reimburse Pecson for his construction cost of P53,000, following

which, the spouses Nuguid were entitled to immediate issuance of a writ of possession over the lot and

improvements. In the same order the RTC also directed Pecson to pay the same amount of monthly

rentals to the Nuguids as paid by the tenants occupying the apartment units or P21,000 per month from

June 23, 1993, and allowed the offset of the amount of P53,000 due from the Nuguids against the

amount of rents collected by Pecson from June 23, 1993 to September 23, 1993 from the tenants of the

apartment.

[8]

Pecson duly moved for reconsideration, but on November 8, 1993, the RTC issued a Writ of

Possession,

[9]

directing the deputy sheriff to put the spouses Nuguid in possession of the subject

property with all the improvements thereon and to eject all the occupants therein.

Aggrieved, Pecson then filed a special civil action for certiorari and prohibition docketed as CA-G.R.

SP No. 32679 with the Court of Appeals.

In its decision of June 7, 1994, the appellate court, relying upon Article 448

[10]

of the Civil Code,

affirmed the order of payment of construction costs but rendered the issue of possession moot on

appeal, thus:

WHEREFORE, while it appears that private respondents [spouses Nuguid] have not yet indemnified

petitioner [Pecson] with the cost of the improvements, since Annex I shows that the Deputy Sheriff has

enforced the Writ of Possession and the premises have been turned over to the possession of private

respondents, the quest of petitioner that he be restored in possession of the premises is rendered moot

and academic, although it is but fair and just that private respondents pay petitioner the construction

cost of P53,000.00; and that petitioner be ordered to account for any and all fruits of the improvements

received by him starting on June 23, 1993, with the amount of P53,000.00 to be offset therefrom.

IT IS SO ORDERED.

[11]

[Underscoring supplied.]

Frustrated by this turn of events, Pecson filed a petition for review docketed as G.R. No. 115814

before this Court.

On May 26, 1995, the Court handed down the decision in G.R. No 115814, to wit:

WHEREFORE, the decision of the Court of Appeals in CA-G.R. SP No. 32679 and the Order of 15

November 1993 of the Regional Trial Court, Branch 101, Quezon City in Civil Case No. Q-41470 are

hereby SET ASIDE.

The case is hereby remanded to the trial court for it to determine the current market value of the

apartment building on the lot. For this purpose, the parties shall be allowed to adduce evidence on the

current market value of the apartment building. The value so determined shall be forthwith paid by the

private respondents [Spouses Juan and Erlinda Nuguid] to the petitioner [Pedro Pecson] otherwise the

petitioner shall be restored to the possession of the apartment building until payment of the required

indemnity.

No costs.

SO ORDERED.

[12]

[Emphasis supplied.]

In so ruling, this Court pointed out that: (1) Article 448 of the Civil Code is not apposite to the case

at bar where the owner of the land is the builder, sower, or planter who then later lost ownership of the

land by sale, but may, however, be applied by analogy; (2) the current market value of the

improvements should be made as the basis of reimbursement; (3) Pecson was entitled to retain

ownership of the building and, necessarily, the income therefrom; (4) the Court of Appeals erred not

only in upholding the trial courts determination of the indemnity, but also in ordering Pecson to

account for the rentals of the apartment building from June 23, 1993 to September 23, 1993.

On the basis of this Courts decision in G.R. No. 115814, Pecson filed a Motion to Restore

Possession and a Motion to Render Accounting, praying respectively for restoration of his possession

over the subject 256-square meter commercial lot and for the spouses Nuguid to be directed to render

an accounting under oath, of the income derived from the subject four-door apartment from November

22, 1993 until possession of the same was restored to him.

In an Order

[13]

dated January 26, 1996, the RTC denied the Motion to Restore Possession to the

plaintiff averring that the current market value of the building should first be determined. Pending the

said determination, the resolution of the Motion for Accounting was likewise held in abeyance.

With the submission of the parties assessment and the reports of the subject realty, and the

reports of the Quezon City Assessor, as well as the members of the duly constituted assessment

committee, the trial court issued the following Order

[14]

dated October 7, 1997, to wit:

On November 21, 1996, the parties manifested that they have arrived at a compromise agreement that

the value of the said improvement/building is P400,000.00 The Court notes that the plaintiff has already

receivedP300,000.00. However, when defendant was ready to pay the balance of P100,000.00, the

plaintiff now insists that there should be a rental to be paid by defendants. Whether or not this should

be paid by defendants, incident is hereby scheduled for hearing on November 12, 1997 at 8:30 a.m.

Meantime, defendants are directed to pay plaintiff the balance of P100,000.00.

SO ORDERED.

[15]

On December 1997, after paying the said P100,000 balance to Pedro Pecson the

spouses Nuguid prayed for the closure and termination of the case, as well as the cancellation of the

notice of lis pendens on the title of the property on the ground that Pedro Pecsons claim for rentals was

devoid of factual and legal bases.

[16]

After conducting a hearing, the lower court issued an Order dated July 31, 1998, directing the

spouses to pay the sum of P1,344,000 as reimbursement of the unrealized income of Pecson for the

period beginning November 22, 1993 up to December 1997. The sum was based on the computation

of P28,000/month rentals of the four-door apartment, thus:

The Court finds plaintiffs motion valid and meritorious. The decision of the Supreme Court in the

aforesaid case [Pecson vs. Court of Appeals, 244 SCRA 407] which set aside the Order of this Court of

November 15, 1993 has in effect upheld plaintiffs right of possession of the building for as long as he is

not fully paid the value thereof. It follows, as declared by the Supreme Court in said decision that the

plaintiff is entitled to the income derived therefrom, thus

. . .

Records show that the plaintiff was dispossessed of the premises on November 22, 1993 and that he

was fully paid the value of his building in December 1997. Therefore, he is entitled to the income

thereof beginning onNovember 22, 1993, the time he was dispossessed, up to the time of said full

payment, in December 1997, or a total of 48 months.

The only question left is the determination of income of the four units of apartments per month. But as

correctly pointed out by plaintiff, the defendants have themselves submitted their affidavits attesting

that the income derived from three of the four units of the apartment building is P21,000.00 or

P7,000.00 each per month, or P28,000.00 per month for the whole four units. Hence, at P28,000.00 per

month, multiplied by 48 months, plaintiff is entitled to be paid by defendants the amount of

P1,344,000.00.

[17]

The Nuguid spouses filed a motion for reconsideration but this was denied for lack of merit.

[18]

The Nuguid couple then appealed the trial courts ruling to the Court of Appeals, their action

docketed as CA-G.R. CV No. 64295.

In the Court of Appeals, the order appealed from in CA-G.R. CV No. 64295, was modified. The CA

reduced the rentals from P1,344,000 to P280,000 in favor of the appellee.

[19]

The said amount

represents accrued rentals from the determination of the current market value on January 31,

1997

[20]

until its full payment on December 12, 1997.

Hence, petitioners state the sole assignment of error now before us as follows:

THE COURT OF APPEALS ERRED IN HOLDING PETITIONERS LIABLE TO PAY RENT OVER AND ABOVE THE

CURRENT MARKET VALUE OF THE IMPROVEMENT WHEN SUCH WAS NOT PROVIDED FOR IN THE

DISPOSITIVE PORTION OF THE SUPREME COURTS RULING IN G.R. No. 115814.

Petitioners call our attention to the fact that after reaching an agreed price of P400,000 for the

improvements, they only made a partial payment of P300,000. Thus, they contend that their failure to

pay the full price for the improvements will, at most, entitle respondent to be restored to possession,

but not to collect any rentals. Petitioners insist that this is the proper interpretation of the dispositive

portion of the decision in G.R. No. 115814, which states in part that [t]he value so determined shall be

forthwith paid by the private respondents [Spouses Juan and Erlinda Nuguid] to the petitioner [Pedro

Pecson] otherwise the petitioner shall be restored to the possession of the apartment building until

payment of the required indemnity.

[21]

Now herein respondent, Pecson, disagrees with herein petitioners contention. He argues that

petitioners are wrong in claiming that inasmuch as his claim for rentals was not determined in the

dispositive portion of the decision in G.R. No. 115814, it could not be the subject of execution. He

points out that in moving for an accounting, all he asked was that the value of the fruits of the property

during the period he was dispossessed be accounted for, since this Court explicitly recognized in G.R.

No. 115814, he was entitled to the property. He points out that this Court ruled that [t]he petitioner

[Pecson] not having been so paid, he was entitled to retain ownership of the building and, necessarily,

the income therefrom.

[22]

In other words, says respondent, accounting was necessary. For accordingly,

he was entitled to rental income from the property. This should be given effect. The Court could have

very well specifically included rent (as fruit or income of the property), but could not have done so at the

time the Court pronounced judgment because its value had yet to be determined, according to

him. Additionally, he faults the appellate court for modifying the order of the RTC, thus defeating his

right as a builder in good faith entitled to rental from the period of his dispossession to full payment of

the price of his improvements, which spans from November 22, 1993 to December 1997, or a period of

more than four years.

It is not disputed that the construction of the four-door two-storey apartment, subject of this

dispute, was undertaken at the time when Pecson was still the owner of the lot. When the Nuguids

became the uncontested owner of the lot on June 23, 1993, by virtue of entry of judgment of the

Courts decision, dated May 25, 1993, in G.R. No. 105360, the apartment building was already in

existence and occupied by tenants. In its decision dated May 26, 1995 in G.R. No. 115814, the Court

declared the rights and obligations of the litigants in accordance with Articles 448 and 546 of the Civil

Code. These provisions of the Code are directly applicable to the instant case.

Under Article 448, the landowner is given the option, either to appropriate the improvement as his

own upon payment of the proper amount of indemnity or to sell the land to the possessor in good

faith. Relatedly, Article 546 provides that a builder in good faith is entitled to full reimbursement for all

the necessary and useful expenses incurred; it also gives him right of retention until full reimbursement

is made.

While the law aims to concentrate in one person the ownership of the land and the improvements

thereon in view of the impracticability of creating a state of forced co-ownership,

[23]

it guards against

unjust enrichment insofar as the good-faith builders improvements are concerned. The right of

retention is considered as one of the measures devised by the law for the protection of builders in good

faith. Its object is to guarantee full and prompt reimbursement as it permits the actual possessor to

remain in possession while he has not been reimbursed (by the person who defeated him in the case for

possession of the property) for those necessary expenses and useful improvements made by him on the

thing possessed.

[24]

Accordingly, a builder in good faith cannot be compelled to pay rentals during the

period of retention

[25]

nor be disturbed in his possession by ordering him to vacate. In addition, as in

this case, the owner of the land is prohibited from offsetting or compensating the necessary and useful

expenses with the fruits received by the builder-possessor in good faith. Otherwise, the security

provided by law would be impaired. This is so because the right to the expenses and the right to the

fruits both pertain to the possessor, making compensation juridically impossible; and one cannot be

used to reduce the other.

[26]

As we earlier held, since petitioners opted to appropriate the improvement for themselves as early

as June 1993, when they applied for a writ of execution despite knowledge that the auction sale did not

include the apartment building, they could not benefit from the lots improvement, until they

reimbursed the improver in full, based on the current market value of the property.

Despite the Courts recognition of Pecsons right of ownership over the apartment building, the

petitioners still insisted on dispossessing Pecson by filing for a Writ of Possession to cover both the lot

and the building. Clearly, this resulted in a violation of respondents right of retention. Worse,

petitioners took advantage of the situation to benefit from the highly valued, income-yielding, four-unit

apartment building by collecting rentals thereon, before they paid for the cost of the apartment

building. It was only four years later that they finally paid its full value to the respondent.

Petitioners interpretation of our holding in G.R. No. 115814 has neither factual nor legal basis. The

decision of May 26, 1995, should be construed in connection with the legal principles which form the

basis of the decision, guided by the precept that judgments are to have a reasonable intendment to do

justice and avoid wrong.

[27]

The text of the decision in G.R. No. 115814 expressly exempted Pecson from liability to pay rentals,

for we found that the Court of Appeals erred not only in upholding the trial courts determination of the

indemnity, but also in ordering him to account for the rentals of the apartment building from June 23,

1993 to September 23, 1993, the period from entry of judgment untilPecsons dispossession. As pointed

out by Pecson, the dispositive portion of our decision in G.R. No. 115814 need not specifically include

the income derived from the improvement in order to entitle him, as a builder in good faith, to such

income. The right of retention, which entitles the builder in good faith to the possession as well as the

income derived therefrom, is already provided for under Article 546 of the Civil Code.

Given the circumstances of the instant case where the builder in good faith has been clearly denied

his right of retention for almost half a decade, we find that the increased award of rentals by

the RTC was reasonable and equitable. The petitioners had reaped all the benefits from the

improvement introduced by the respondent during said period, without paying any amount to the latter

as reimbursement for his construction costs and expenses. They should account and pay for such

benefits.

We need not belabor now the appellate courts recognition of herein respondents entitlement to

rentals from the date of the determination of the current market value until its full

payment. Respondent is clearly entitled to payment by virtue of his right of retention over the said

improvement.

WHEREFORE, the instant petition is DENIED for lack of merit. The Decision dated May 21, 2001 of

the Court of Appeals in CA-G.R. CV No. 64295 is SET ASIDE and the Order dated July 31, 1998, of the

Regional Trial Court, Branch 101, Quezon City, in Civil Case No. Q-41470 ordering the herein petitioners,

Spouses Juan and Erlinda Nuguid, to account for the rental income of the four-door two-storey

apartment building from November 1993 until December 1997, in the amount of P1,344,000, computed

on the basis of Twenty-eight Thousand (P28,000.00) pesos monthly, for a period of 48 months, is hereby

REINSTATED. Until fully paid, said amount of rentals should bear the legal rate of interest set at six

percent (6%) per annum computed from the date of RTC judgment. If any portion thereof shall

thereafter remain unpaid, despite notice of finality of this Courts judgment, said remaining unpaid

amount shall bear the rate of interest set at twelve percent (12%) per annum computed from the date

of said notice. Costs against petitioners.

SO ORDERED.

Davide, Jr., C.J., (Chairman), Ynares-Santiago, Carpio, and Azcuna, JJ., concur.

Você também pode gostar

- Patent Laws of the Republic of Hawaii and Rules of Practice in the Patent OfficeNo EverandPatent Laws of the Republic of Hawaii and Rules of Practice in the Patent OfficeAinda não há avaliações

- Property. Nuguid V Ca. Full CaseDocumento7 páginasProperty. Nuguid V Ca. Full CaseAnonymous XduaVMAinda não há avaliações

- Nuguid vs. Court of AppealsDocumento5 páginasNuguid vs. Court of AppealsMj BrionesAinda não há avaliações

- Pecson Vs Court of Appeals 61 SCAD 385Documento6 páginasPecson Vs Court of Appeals 61 SCAD 385lailani murilloAinda não há avaliações

- Pecson vs. CA G.R. No. 115814 May 29, 1995Documento8 páginasPecson vs. CA G.R. No. 115814 May 29, 1995lassenAinda não há avaliações

- Supreme CourtDocumento38 páginasSupreme CourtClaire RoxasAinda não há avaliações

- Property Case - Accession - Pecson V CADocumento4 páginasProperty Case - Accession - Pecson V CAJoyceAinda não há avaliações

- PECSON v. CADocumento8 páginasPECSON v. CAValerie PinoteAinda não há avaliações

- Supreme Court: Republic of The Philippines Manila First DivisionDocumento5 páginasSupreme Court: Republic of The Philippines Manila First DivisionSiobhan RobinAinda não há avaliações

- Pedro Pecson v. Court of Appeals and Spouses Nuguid (G.R. No. 115814 May 26, 1995)Documento6 páginasPedro Pecson v. Court of Appeals and Spouses Nuguid (G.R. No. 115814 May 26, 1995)King KingAinda não há avaliações

- G.R. No. 115814Documento5 páginasG.R. No. 115814Stud McKenzeeAinda não há avaliações

- Spouses Nuguid Vs CA DigestDocumento3 páginasSpouses Nuguid Vs CA DigestLeo TumaganAinda não há avaliações

- G.R. No. 151815 February 23, 2005 Spouses Juan Nuguid and Erlinda T. Nuguid, Petitioners, Hon. Court of Appeals and Pedro P. Pecson, RespondentsDocumento1 páginaG.R. No. 151815 February 23, 2005 Spouses Juan Nuguid and Erlinda T. Nuguid, Petitioners, Hon. Court of Appeals and Pedro P. Pecson, RespondentsGieann BustamanteAinda não há avaliações

- Spouses Juan Nuguid and Erlinda TDocumento2 páginasSpouses Juan Nuguid and Erlinda TClaire CabigaoAinda não há avaliações

- Nuguid vs. CADocumento2 páginasNuguid vs. CATEtchie TorreAinda não há avaliações

- Spouses Juan Nuguid and Erlinda TDocumento2 páginasSpouses Juan Nuguid and Erlinda TJohn Paul Pagala AbatAinda não há avaliações

- Paculdo v. Regalado, 345 SCRA 134 (2000)Documento4 páginasPaculdo v. Regalado, 345 SCRA 134 (2000)Fides DamascoAinda não há avaliações

- G.R. No. 109125 Asuncion vs. CADocumento9 páginasG.R. No. 109125 Asuncion vs. CASta Maria JamesAinda não há avaliações

- GR No 123855 Paculdo Vs RegaladoDocumento6 páginasGR No 123855 Paculdo Vs RegaladoAnabelle Talao-UrbanoAinda não há avaliações

- Ang Yu Asuncion V The Hon Court of Appeals, 238 SCRA 602 (1994)Documento9 páginasAng Yu Asuncion V The Hon Court of Appeals, 238 SCRA 602 (1994)Ryan Paul AquinoAinda não há avaliações

- Manaloto Vs VelosoDocumento9 páginasManaloto Vs VelosoJerick Christian P DagdaganAinda não há avaliações

- ObliDocumento43 páginasObliSugar RiAinda não há avaliações

- Capistrano vs. LimcuadoDocumento14 páginasCapistrano vs. LimcuadoRon Ico RamosAinda não há avaliações

- Central Bank vs. BicharaDocumento10 páginasCentral Bank vs. BicharaXsche XscheAinda não há avaliações

- Paculdo V CADocumento5 páginasPaculdo V CAMADEE VILLANUEVAAinda não há avaliações

- Credit Transactions CasesDocumento364 páginasCredit Transactions CasesJaniceAinda não há avaliações

- Ang Yu Asuncion Vs CADocumento3 páginasAng Yu Asuncion Vs CAmonjekatreenaAinda não há avaliações

- Asuncion vs. CADocumento6 páginasAsuncion vs. CAKennex de DiosAinda não há avaliações

- Asuncion v. CADocumento9 páginasAsuncion v. CAEmail DumpAinda não há avaliações

- Batch 4Documento86 páginasBatch 4Rae DarAinda não há avaliações

- Catungal V HaoDocumento6 páginasCatungal V Haocmv mendozaAinda não há avaliações

- Capistrano vs. Limcuando, GR 152413, February 13, 2009, 579 SCRA 176Documento7 páginasCapistrano vs. Limcuando, GR 152413, February 13, 2009, 579 SCRA 176Marianne Shen PetillaAinda não há avaliações

- Manaloto Vs VelosoDocumento11 páginasManaloto Vs VelosoLorelei B RecuencoAinda não há avaliações

- G.R. No. 197329 September 8, 2014 National Power Corporation, Petitioner, LUIS SAMAR and MAGDALENA SAMAR, RespondentsDocumento46 páginasG.R. No. 197329 September 8, 2014 National Power Corporation, Petitioner, LUIS SAMAR and MAGDALENA SAMAR, RespondentsFCAinda não há avaliações

- City of Cebu V Dedamo GR 142971Documento6 páginasCity of Cebu V Dedamo GR 142971MelgenAinda não há avaliações

- Obli Con CasesDocumento567 páginasObli Con CasesVeron Gem DalumbarAinda não há avaliações

- The City of Cebu, Petitioner, vs. Spouses Apolonio and Blasa DEDAMO, Respondents. DecisionDocumento6 páginasThe City of Cebu, Petitioner, vs. Spouses Apolonio and Blasa DEDAMO, Respondents. DecisionJoanne LontokAinda não há avaliações

- YuliengcoDocumento7 páginasYuliengcoabbiemedinaAinda não há avaliações

- G.R. No. 146364 June 3, 2004 COLITO T. PAJUYO, Petitioner, Court of Appeals and Eddie Guevarra, RespondentsDocumento77 páginasG.R. No. 146364 June 3, 2004 COLITO T. PAJUYO, Petitioner, Court of Appeals and Eddie Guevarra, Respondentsjack fackageAinda não há avaliações

- Manaloto Vs VelosoDocumento11 páginasManaloto Vs VelosocessyJDAinda não há avaliações

- 47 - Dizon V CaDocumento6 páginas47 - Dizon V CaRaven DizonAinda não há avaliações

- Pecson Vs CADocumento4 páginasPecson Vs CAmanilyn09Ainda não há avaliações

- Paculdo V Regalado 2Documento7 páginasPaculdo V Regalado 2Joshua TanAinda não há avaliações

- 30 G.R. No. 147405 April 25, 2006 Platinum Plans Phil. Inc Vs CucuecoDocumento6 páginas30 G.R. No. 147405 April 25, 2006 Platinum Plans Phil. Inc Vs CucuecorodolfoverdidajrAinda não há avaliações

- Terana Vs de SagunDocumento10 páginasTerana Vs de SagunOmar Nasseef BakongAinda não há avaliações

- Palattao vs. CoDocumento8 páginasPalattao vs. CoRhea CalabinesAinda não há avaliações

- G.R. No. 123855 November 20, 2000 NEREO J. PACULDO, Petitioner, BONIFACIO C. REGALADO, RespondentDocumento18 páginasG.R. No. 123855 November 20, 2000 NEREO J. PACULDO, Petitioner, BONIFACIO C. REGALADO, RespondentMichaela GarciaAinda não há avaliações

- Cases 1156-1162Documento120 páginasCases 1156-1162Dawn BarondaAinda não há avaliações

- Pajuyo v. CADocumento24 páginasPajuyo v. CAElla MarceloAinda não há avaliações

- G.R. No. 148568Documento10 páginasG.R. No. 148568Demi Lynn YapAinda não há avaliações

- G.R. No. 123855 November 20, 2000 Nereo J. PACULDO, Petitioner, BONIFACIO C. REGALADO, RespondentDocumento4 páginasG.R. No. 123855 November 20, 2000 Nereo J. PACULDO, Petitioner, BONIFACIO C. REGALADO, RespondentCleofe SobiacoAinda não há avaliações

- GR No L39378 Ayson Simon Vs AdamosDocumento3 páginasGR No L39378 Ayson Simon Vs AdamosAnabelle Talao-UrbanoAinda não há avaliações

- Petitioner vs. vs. Respondents Barbers Molina & Tamargo Benjamin C ReyesDocumento8 páginasPetitioner vs. vs. Respondents Barbers Molina & Tamargo Benjamin C ReyesTintin SumawayAinda não há avaliações

- PHILIPPINE NATIONAL OIL COMPANY, Petitioner vs. LEONILO A. MAGLASANG and OSCAR S. MAGLASANGDocumento4 páginasPHILIPPINE NATIONAL OIL COMPANY, Petitioner vs. LEONILO A. MAGLASANG and OSCAR S. MAGLASANGBOT1 BOT1Ainda não há avaliações

- Dizon vs. Court of Appeals (302 SCRA 288)Documento3 páginasDizon vs. Court of Appeals (302 SCRA 288)goma21Ainda não há avaliações

- 1963 Constantino - v. - Aquino20211129 11 1eghcghDocumento7 páginas1963 Constantino - v. - Aquino20211129 11 1eghcghMeryl Cayla C. GuintuAinda não há avaliações

- CITY of CEBU Vs Sps DedamoDocumento6 páginasCITY of CEBU Vs Sps DedamoKatrina BudlongAinda não há avaliações

- Marilag v. MartinezDocumento6 páginasMarilag v. MartinezCar L MinaAinda não há avaliações

- Hi-Yield Realty Inc Vs CA - 138978 - September 12, 2002 - J. Corona - Third DivisionDocumento8 páginasHi-Yield Realty Inc Vs CA - 138978 - September 12, 2002 - J. Corona - Third DivisionQueenie BoadoAinda não há avaliações

- Pecson Vs CADocumento3 páginasPecson Vs CASophiaFrancescaEspinosaAinda não há avaliações

- JLT Agro Vs BalansangDocumento16 páginasJLT Agro Vs BalansangPaolo Antonio EscalonaAinda não há avaliações

- Austria Vs ReyesDocumento7 páginasAustria Vs ReyesPaolo Antonio EscalonaAinda não há avaliações

- Natural Deductions DocumentDocumento3 páginasNatural Deductions DocumentPaolo Antonio EscalonaAinda não há avaliações

- MT DoctrinesDocumento8 páginasMT DoctrinesPaolo Antonio EscalonaAinda não há avaliações

- MIAA Vs PasayDocumento39 páginasMIAA Vs PasayPaolo Antonio EscalonaAinda não há avaliações

- Pepsi Cola Bottling Co. Vs Municipality of Tanauan LeyteDocumento13 páginasPepsi Cola Bottling Co. Vs Municipality of Tanauan LeytePaolo Antonio EscalonaAinda não há avaliações

- Philippine Commercial and Industrial Bank Vs EscolinDocumento4 páginasPhilippine Commercial and Industrial Bank Vs EscolinPaolo Antonio EscalonaAinda não há avaliações

- IV. Transfer and NegotiationDocumento62 páginasIV. Transfer and NegotiationPaolo Antonio EscalonaAinda não há avaliações

- RA 9189 Overseas Absentee Voting Act 2003Documento15 páginasRA 9189 Overseas Absentee Voting Act 2003Paolo Antonio EscalonaAinda não há avaliações

- Pelizloy Realty Corporation Vs The Province of BenguetDocumento11 páginasPelizloy Realty Corporation Vs The Province of BenguetPaolo Antonio EscalonaAinda não há avaliações

- Judicial Affidavit SampleDocumento3 páginasJudicial Affidavit SamplePaolo Antonio EscalonaAinda não há avaliações

- Election Law Doctrines I-VII (Midterms)Documento16 páginasElection Law Doctrines I-VII (Midterms)Paolo Antonio EscalonaAinda não há avaliações

- CIR Vs SM Prime HoldingsDocumento17 páginasCIR Vs SM Prime HoldingsPaolo Antonio EscalonaAinda não há avaliações

- III. Parties (Articles and Cases)Documento9 páginasIII. Parties (Articles and Cases)Paolo Antonio EscalonaAinda não há avaliações

- Judicial Affidavit RuleDocumento4 páginasJudicial Affidavit RuleCaroline DulayAinda não há avaliações

- Nirc PDFDocumento160 páginasNirc PDFCharlie Magne G. Santiaguel100% (3)

- Nego OutlineDocumento12 páginasNego OutlineEdwardArribaAinda não há avaliações

- EO 157 Local Absentee Voting ActDocumento2 páginasEO 157 Local Absentee Voting ActPaolo Antonio EscalonaAinda não há avaliações

- RA 8189 Voter's Registration Act of 1996Documento19 páginasRA 8189 Voter's Registration Act of 1996Paolo Antonio EscalonaAinda não há avaliações

- COMELEC Resolution 9485 Voting of PWDDocumento18 páginasCOMELEC Resolution 9485 Voting of PWDPaolo Antonio EscalonaAinda não há avaliações

- Yra Vs AbanoDocumento4 páginasYra Vs AbanoPaolo Antonio EscalonaAinda não há avaliações

- People Vs CorralDocumento5 páginasPeople Vs CorralAr Yan SebAinda não há avaliações

- Vera Vs FernandezDocumento6 páginasVera Vs FernandezPaolo Antonio EscalonaAinda não há avaliações

- Compiled Case Digest-Cabuchan (v2)Documento29 páginasCompiled Case Digest-Cabuchan (v2)Paolo Antonio EscalonaAinda não há avaliações

- Lutz Vs AranetaDocumento4 páginasLutz Vs AranetaMarlanSaculsanAinda não há avaliações

- I. Introduction CasesDocumento31 páginasI. Introduction CasesPaolo Antonio EscalonaAinda não há avaliações

- Domingo Vs Garlitos PDFDocumento4 páginasDomingo Vs Garlitos PDFPaolo Antonio EscalonaAinda não há avaliações

- Punsalan Vs ManilaDocumento4 páginasPunsalan Vs ManilaPaolo Antonio EscalonaAinda não há avaliações

- EDITED Torts Case Digest 1Documento40 páginasEDITED Torts Case Digest 1Paolo Antonio EscalonaAinda não há avaliações

- CPC Paper 1Documento24 páginasCPC Paper 1tarundaburAinda não há avaliações

- 1997 Rules of Civil ProcedureDocumento20 páginas1997 Rules of Civil ProcedureMikhail TignoAinda não há avaliações

- Const Tutorial 6 - Human RightsDocumento19 páginasConst Tutorial 6 - Human Rightspearlyang_20067859Ainda não há avaliações

- Khan Law OutlineDocumento105 páginasKhan Law OutlineTybAinda não há avaliações

- Rule 117 CasesDocumento63 páginasRule 117 CasesPre PacionelaAinda não há avaliações

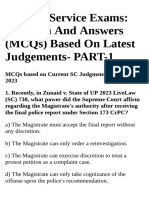

- Judicial Service Exams Question and Answers MCQs Based On LatDocumento20 páginasJudicial Service Exams Question and Answers MCQs Based On LatPragya BansalAinda não há avaliações

- New Mexico Governors 1656-1661Documento1 páginaNew Mexico Governors 1656-1661hansiensAinda não há avaliações

- Torts ! Outline - SMUDocumento30 páginasTorts ! Outline - SMUVape NationAinda não há avaliações

- Sabello Vs DECSDocumento5 páginasSabello Vs DECSJezen Esther PatiAinda não há avaliações

- 164935-2010-Masangkay v. People PDFDocumento13 páginas164935-2010-Masangkay v. People PDFWazzupAinda não há avaliações

- Agenda: Board of County CommissionersDocumento6 páginasAgenda: Board of County CommissionersMichael AllenAinda não há avaliações

- Georg V Holy Trinity CollegeDocumento18 páginasGeorg V Holy Trinity CollegeGlen VillanuevaAinda não há avaliações

- Gutierrez Hermanos vs. Engracio Orense, G.R. No. L-9188, 28 Phil. 571, December 4, 1914Documento2 páginasGutierrez Hermanos vs. Engracio Orense, G.R. No. L-9188, 28 Phil. 571, December 4, 1914Rodel OrtezaAinda não há avaliações

- Case Review Stephen Kalong NingkanDocumento13 páginasCase Review Stephen Kalong NingkanKyriosHaiqalAinda não há avaliações

- Motion For Stay Pending AppealDocumento3 páginasMotion For Stay Pending AppealJim MorrisAinda não há avaliações

- Charles Manson DNA RulingDocumento1 páginaCharles Manson DNA RulingLeigh EganAinda não há avaliações

- 20 Fidelity Savings and Mortgage Bank vs. Hon. Pedro CenzonDocumento8 páginas20 Fidelity Savings and Mortgage Bank vs. Hon. Pedro Cenzonrachelle baggaoAinda não há avaliações

- Lee Ah Tee V Ong Tiow PhengDocumento2 páginasLee Ah Tee V Ong Tiow PhengNur AliahAinda não há avaliações

- Peole V FabonDocumento3 páginasPeole V FabonCelestino LawAinda não há avaliações

- CASE DIGEST Remigio Quiqui Et Al Vs Hon Alejandro R Boncarlos Et AlDocumento2 páginasCASE DIGEST Remigio Quiqui Et Al Vs Hon Alejandro R Boncarlos Et AlEvangelyn Egusquiza100% (1)

- Civil ProcedureDocumento27 páginasCivil ProcedureSharalyn RamirezAinda não há avaliações

- Nego Cases DigestedDocumento82 páginasNego Cases DigestedMark AnthonyAinda não há avaliações

- Spouses Bacolor Vs Banco FilipinoDocumento1 páginaSpouses Bacolor Vs Banco FilipinoiwanttoeatAinda não há avaliações

- MR and MNTDocumento5 páginasMR and MNTAnonymous ku7POqvKAinda não há avaliações

- Chuidian v. Sandiganbayan Case DigestDocumento2 páginasChuidian v. Sandiganbayan Case Digestalbemart100% (2)

- In Re A Bankruptcy Notice. (No. 171 of 1934.Documento6 páginasIn Re A Bankruptcy Notice. (No. 171 of 1934.fikriz89Ainda não há avaliações

- Antonio v. GeronimoDocumento21 páginasAntonio v. Geronimofaye wongAinda não há avaliações

- Comprehensive Syllabus-Based Reviewer in Rem IiDocumento144 páginasComprehensive Syllabus-Based Reviewer in Rem IiKareem Ledesma Alsula88% (8)

- Duer v. Bensussen Deutsch & Associates Et. Al.Documento16 páginasDuer v. Bensussen Deutsch & Associates Et. Al.PriorSmartAinda não há avaliações

- Insular Drug Co. vs. National Bank: Camus & Delgado For Appellant. Franco & Reinoso For AppelleeDocumento4 páginasInsular Drug Co. vs. National Bank: Camus & Delgado For Appellant. Franco & Reinoso For AppelleeJoannah SalamatAinda não há avaliações