Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Putting The Common European Framework of Reference To Good Use

Enviado por

Justin OwensDescrição original:

Título original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Putting The Common European Framework of Reference To Good Use

Enviado por

Justin OwensDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Language Teaching

http://journals.cambridge.org/LTA

Additional services for Language Teaching:

Email alerts: Click here

Subscriptions: Click here

Commercial reprints: Click here

Terms of use : Click here

Putting the Common European Framework of Reference to

good use

Brian North

Language Teaching / Volume 47 / Issue 02 / April 2014, pp 228 - 249

DOI: 10.1017/S0261444811000206, Published online: 19 April 2011

Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S0261444811000206

How to cite this article:

Brian North (2014). Putting the Common European Framework of Reference to good use .

Language Teaching, 47, pp 228-249 doi:10.1017/S0261444811000206

Request Permissions : Click here

Downloaded from http://journals.cambridge.org/LTA, IP address: 79.143.86.44 on 26 Jun 2014

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 26 Jun 2014 IP address: 79.143.86.44

Lang. Teach. (2014), 47.2, 228249 c

Cambridge University Press 2011

doi:10.1017/S0261444811000206 First published online 19 April 2011

Plenary Speeches

Putting the Common European Framework of Reference to

good use

Brian North EAQUALS; Eurocentres Foundation, Switzerland

bnorth@eaquals.org; bjnorth@eurocentres.com

This paper recapitulates the aims of the CEFR and highlights three aspects of good practice in

exploiting it: rstly, taking as a starting point the real-world language ability that is the aim of

all modern language learners; secondly, the exploitation of good descriptors as transparent

learning objectives in order to involve and empower the learners; and thirdly, engaging with

the COMMUNALITY of the CEFR Common Reference Levels in relating assessments to it. The

second part of the paper focuses on good practice in such linking of assessments to the CEFR.

It outlines the recommended procedures published by the Council of Europe for linking

language examinations to the CEFR and the adaptation of those procedures for teacher

assessment in language schools that has recently been undertaken by EAQUALS. The paper

concludes by discussing certain aspects of criterion-referenced assessment (CR) and standard

setting that are relevant to the linking process.

1. Purpose of the Common European Framework of Reference

First, let us remind ourselves what the Common European Framework of Reference (CEFR)

(Council of Europe 2001) is about. Published in 2001 after a period of piloting, it consists of

a descriptive scheme, common reference points expressed as six prociency levels, descriptor

scales for many aspects of that descriptive scheme, advice on curriculum scenarios and

considerations for reection. The aim of the CEFR is to stimulate reection on current

practice and to provide common reference levels to facilitate communication, comparison of

courses and qualications, plus, eventually, personal mobility as a result. In this process, in

relation to assessment, the CEFR descriptors can be of help:

For the specication of the content of tests and WHAT IS ASSESSED

examinations:

For stating the criteria to determine the attainment of a HOW PERFORMANCE IS

learning objective: INTERPRETED

For describing the levels of prociency in existing HOW COMPARISONS

tests and examinations, thus enabling comparisons to CAN BE MADE

be made across different systems of qualications: (Council of Europe 2001: 178)

Revised version of a plenary address given at the seminar Putting the CEFR to good use held jointly by EALTA

(www.ealta.org) and the IATEFL TEA (Testing, Evaluation and Assessment) Special Interest Group, Barcelona, Spain,

29 October, 2010.

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 26 Jun 2014 IP address: 79.143.86.44

B R I A N N O R T H : P U T T I N G T H E C E F R T O G O O D U S E 229

Before the CEFRthere was a practical Tower of Babel problemin making sense of course

certicates and test scores. A teacher, school or examination body would carry out a test and

report a result in their own way as 19, 4.5, 516, B, Good, etc. It is no exaggeration to

say that twenty years ago a teacher of Spanish in a secondary school in southern France, a

teacher of French to Polish adults and a teacher of English to German businessmen would

have taken ten to twenty minutes to establish any common ground for a discussion. The

CEFR labels help.

In taking notice of the CEFR, most people therefore start with the levels. In contrast

to those used in other language prociency scales, the CEFR descriptors and levels are

the product of serious validation in pre-development studies (North 1995: 2000a; North

& Schneider 1998) and post-development studies (Jones 2002; Kaftandjieva & Takala

2002; North 2002). These conrmed that language teachers and learners interpret the

descriptors consistently across a sample of educational contexts, regions and target languages.

However, the existence of a scale of levels does not mean that situating learners, courses and

examinations on that scale is straightforward. Experimentation with the CEFR descriptors

contained in checklists for each level in the European Language Portfolio, of which

more than 100 versions have now been produced (Schneider, North & Koch 2000; Little

2005; www.coe.int/portfolio), has helped schools to become reasonably condent in their

judgement as to the level of their learners and courses. But relating examinations and

test scores to the levels is a more serious matter that people have had more difculty

with. Therefore, in response to requests from member states, the Council of Europe put

together a working party to develop a Manual for relating language qualications to the

CEFR, which after publication in pilot form in 2003 is now available on the Council of

Europes website (Council of Europe 2009) accompanied by further material on exploiting

the scaling of teacher assessments (North & Jones 2009), a reference supplement (Takala

2009), and sets of case studies from the piloting now published by CUP (Martyniuk

2010). I will come back to the procedures recommended in the Manual later in the

paper.

The pre-CEFR Tower of Babel problem masked a second, more theoretical problem: the

relation of assessment results to real-world practical language ability. Tests each reported

their own scale and left users to work out what different bands/scores on the scale

meant in terms of real-life ability. As Jones, Ashton & Walker (2010: 230) point out,

the CEFR Manual helps language testers to address this central concern of criterion-

referenced assessment. The CEFR promotes an ACTION-ORIENTED APPROACH: seeing the

learner as a language user with specic needs, who needs to ACT in the language in real-

world domains. The CEFR descriptor scales can provide the vertical continuum of real-

life ability needed as an external criterion for valid criterion-referenced assessment. The

Manual offers sets of procedures to help in this process. This point is returned to later the

paper.

However, it is important to remember that the prime function of the CEFR is not to get

all tests reporting to the same scale but to encourage reection on current practice, and thus

to stimulate improvement in language teaching and learning (and testing). The CEFR was

developed to contribute to reformand innovation and to encourage networking; it is certainly

not a harmonisation project, as we made very clear:

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 26 Jun 2014 IP address: 79.143.86.44

2 3 0 P L E N A R Y S P E E C H E S

We have NOT set out to tell practitioners what to do or howto do it. We are raising questions not answering

them. It is not the function of the CEF to lay down the objectives that users should pursue or the methods

they should employ. (CEFR 2001: xi)

Nor is the CEFR a panacea. It is a heuristic model intended to aid communication,

reection and focused research. This fact was recognised in various articles in the special issue

of the journal Language Testing on the CEFR, best summarised by Norris in his introduction:

. . .in Chapter 2, the principal intended uses of the CEFR are made clear: though arbitrary, prociency

descriptions and scales provide an essential heuristic for understanding and communicating about

language learning and use, and such a heuristic is needed in a contemporary Europe that seeks to

promote mutual understanding, tolerance and knowledge of its rich linguistic and cultural diversity.

(Norris 2005: 400)

Neither has the Council of Europe or any of the authors ever claimed the CEFR to be

perfect or complete. The Council has, in fact, repeatedly stated that all the lists and sets of

descriptors are open-ended. No descriptors at all were published for several important aspects

of the descriptive scheme and some 10% (40) of those that were published are not based on

research, half of those being at C2. I was in a position in which I just had to create most of

the descriptors for communicative language activities at C2. The English Prole Project is

currently focusing on bringing more precision to descriptors for the C levels. I personally nd

it disappointing that we have had to wait 15 years for a follow-up project to further extend

the calibrated descriptor bank.

In any case, as Alderson once pointed out (personal communication), the descriptors

are designed to describe learner behaviour, not test tasks. Operationalising them into

a specication for a test task requires a process of interpretation that is not always

straightforward. As Weir (2005) and Alderson (2007) state, a lot of work is involved in

that process and the CEFR (2001) is of only limited help in this respect. This need for further

specication, development and underpinning was underlined by various contributors to a

series of articles in a special edition of Perspectives in The Modern Language Journal (Byrnes 2007).

The CEFR cannot just be applied; it must be interpreted in a manner appropriate to the

context and further elaborated into a specication for teaching or testing.

Personally, I think that the two biggest dangers with the CEFR are, rstly, a simplistic

assumption that two examinations or courses placed at the same level are in some way

interchangeable and, secondly, a rigid adoption rather than adaptation of the descriptors.

A label such as A2 serves only as a convenient summary of a complex prole. The

CEFR/ELP descriptors are intended for orienting learning and PROFILING developing

competence, not just for determining what overall level someone is considered to be. Every

person and every test that is said to be A2 is said to be A2 for different reasons. As regards

the descriptors, I deliberately kept these as context-neutral as possible, so that the scale

value of each individual descriptor would be more stable across contexts. The descriptors

must be adapted and further elaborated to suit the context, as in the 100 versions of the

European Language Portfolio that have been endorsed by the Council of Europe. Fortunately,

adapting things is not something teachers are shy about doing. A rich bank of such adapted

descriptors is now available on the Council of Europes website as a source of inspiration

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 26 Jun 2014 IP address: 79.143.86.44

B R I A N N O R T H : P U T T I N G T H E C E F R T O G O O D U S E 231

(www.coe.int/portfolio). A recent project in EAQUALS (European Association for Quality

Language Services) reviewed that bank in order to further develop and ll the gaps in a set of

general language descriptors for the main levels (criterion levels) and for the plus levels (levels

between the main levels). The results are also available at the same web site.

2. Good uses of the CEFR

What might, then, be regarded as good use of the CEFR? Apart from the question of a

serious engagement with the COMMUNALITY of the reference levels, which is the subject of

the second half of this paper, I think there are two main points: rstly, taking as a starting

point the real world language ability that is the aim of all modern language learners and,

secondly, the exploitation of good descriptors as transparent learning objectives in order to

involve and empower the learners.

2.1 The real world criterion

The CEFR sees the learner as a language user with specic needs, who needs to act in the

language. It provides a descriptive scheme that, in what was at the time an innovative manner

(North 1997), encompasses both categories used by applied linguistics and categories familiar

to teachers. It outlines domains and communicative language activities (organised under

Reception, Interaction, Production and Mediation), with related communicative language

strategies, communicative language competences (organised under Linguistic, Pragmatic

and Socio-linguistic), and socio-/inter-cultural competences and skills. It is commonplace

to pay lip service to this idea of teaching towards communicative needs, but unfortunately

many teachers, publishers and testers still appear to think just in terms of Lados (1961)

pre-communicative and pre-applied linguistics model of the four skills plus three elements

(grammatical accuracy, vocabulary range and pronunciation), and pop a CEFR level label

on top. Such a perspective can lead to a continuation of the kind of airy-fairy statements of

communicative aims unconnected to classroom reality that were common before the CEFR.

In such a model, needs analysis tends to be interpreted only in terms of a decit model of

remedial linguistic problems, so teachers usually ignore the ofcial aims and just follow the

book, teaching the language.

It really is quite another matter to orient a curriculum consciously through a balanced

set of appropriate (partly CEFR-based) CAN DO DESCRIPTORS as communicative objectives

and then to provide opportunities for learners to acquire/learn the communicative language

competences and strategies necessary for success in the real-world tasks concerned. Keddle

(2004) hit a chord when she commented that whilst authentic materials were common in

EFL in the 1980s and early 90s, the MEGA COURSE BOOKS led to a decline in their use in

class during the 1990s. As she pointed out, the CEFR descriptors of reading and listening of

different types can motivate a selection of authentic materials for all levels. Fortunately, the

advent of YouTube, data projectors and interactive whiteboards is now starting to change

things again at a classroom level.

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 26 Jun 2014 IP address: 79.143.86.44

2 3 2 P L E N A R Y S P E E C H E S

However, there seems to be an unfortunately common misconception that descriptors form

some kind of teaching menu, that they are in some way discrete items that should be taught

one after another. That might possibly be true at A1, or in terms of emphasising the difference

between search reading (CEFR 2001 =Reading for Orientation) and careful reading (CEFR

2001 = Reading for Information and Argument), but otherwise it is simplistic nonsense.

Any real-world or classroom activity will almost certainly involve tasks and competences

represented by clusters of descriptors. One fruitful way of exploiting the CEFR descriptors in

this way is to design CEFR-scenarios. Scenarios are a way of working fromreal-world contexts

in order to integrate relevant descriptors, both as objectives for activities and as quality

criteria for performance, with the enabling aspects of pragmatic and linguistic competence

that underlie the performance, including target language points. This CEFR scenario model,

shown in Appendix 1, was developed by

Angeles Ortega (North, Ortega Calvo & Sheehan

2010: 1317; Ortega Calvo 2010: 72). It consists of two tables, each on an A4 landscape

page in North et al. (2010): the rst page (Appendix 1a to this page) a species the objectives

for a learning module and/or an assessment, and the second page (Appendix 1b) denes

a teaching sequence intended to help learners achieve those objectives. In the top row in

Appendix 1a, global aspects such as the domain, context, real-world tasks and language

activities involved are dened. On the left are listed CEFR-based descriptors appropriate

to the specic scenario, both CAN DO DESCRIPTORS selected or adapted from CEFR (2001)

Chapter 4 (Language use and the language user/learner) and CRITERIA, from CEFR (2001)

Chapter 5 (The competences of the user/learner). On the right-hand side are listed relevant

competences (strategic, pragmatic, linguistic, etc.). The advantage of the scenario concept is

the top-down analysis of the context in terms of the enabling competences needed, and the

promotion of the teaching and assessment of relevant aspects of those competences without

losing sight of their relationship to the overall framework offered by the scenario.

A scenario is not a test specication because concrete assessment tasks, expected responses

and assessment conditions are not dened. A teacher will probably not want to go into such

detail, preferring instead to focus on identifying the steps necessary for the acquisition of the

competences concerned and their integration into a pedagogic sequence. The sequencing

of such pedagogic steps is the subject of the second part of the scenario. In the example

reproduced here as Appendix 1b, developed by Howard Smith, a particular sequencing

model is employed (Harmer 1998). Different teachers will have different preferences for

operational sequencing and for how they describe it. In addition, different approaches suit

particular groups and different levels. The template for describing objectives (Appendix 1a)

is likely to be more standard than the description of how to achieve them (Appendix 1b).

That was certainly the case in the scenarios for different levels produced by members of the

EAQUALS project team. Whereas the scenario overviews all took the approach illustrated in

Appendix 1a, the teaching sequences differed radically. In that respect, I should emphasise

two points. Firstly, a scenario approach does not necessarily involve task-based teaching. The

target real-life activity might not be simulated in the classroom as it is in Smiths suggested

sequence of activities, shown in Appendix 1b. The purpose of the classroom role-play may be

only to give the learner the competences to be successful, rather than to simulate the actual

activity. Alternatively, the scenario may involve a chainof simulated real-world tasks, especially

at lower levels. Secondly, the degree of standardisation may be affected by whether or not

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 26 Jun 2014 IP address: 79.143.86.44

B R I A N N O R T H : P U T T I N G T H E C E F R T O G O O D U S E 233

the scenarios involve more formal assessment. Developing the scenario concept further into

task templates for such formal classroom assessment is the subject of the current EAQUALS

Special Interest Project in this area.

2.2 Learner empowerment

As demonstrated with the scenario model, descriptors are primarily a communication tool.

They are very useful in moderation for needs analysis and consultation with learners about

progress. Can Do descriptors (see CEFR 2001: Chapter 4 for inspiration) can be used as

signposts in syllabuses, course planning, needs analysis forms, classroom displays, evaluation

checklists, personal proles and certicates. In addition, transparent use of descriptors for

aspects of competence (see CEFR 2001: Chapter 5 for inspiration) as assessment criteria

helps learners to know what to focus on and facilitates tutorials, peer-assessment and self-

assessment. Self-directed learning can only start if you know roughly where you are from

reasonably accurate self-assessment. The scenario concept outlined above lends itself to

this approach. The teacher can focus the learners attention on the two different types of

descriptors (action; quality) plus, perhaps, the language of skills that he or she wants the

learners to pay attention to.

Many teachers have come across descriptor checklists for different levels in the European

Language Portfolio. Unfortunately, the rather heavy format of the Portfolio has, to my

mind, hindered its widespread adoption, but this may change in the age of Facebook, with

the web versions of portfolios that are starting to appear (for example, www.eelp.org and

www.ncss.org/links/index.php?linguafolio). It is also a shame that most Portfolios, unlike

the prototype, do not include descriptors for qualitative aspects of competence (Schneider,

North & Koch 2000), since this encourages a simplistic association of the CEFR with a

functional approach, while the CEFR is really a competence-based approach. In CEFR

terms, functional competence is one half of pragmatic competence, the other half being

discourse competence, with two other aspects of language competence (linguistic and socio-

linguistic), plus socio-cultural and intercultural competences. Descriptors are available for all

these aspects except the cultural ones. The conrmation and further elaboration of criterial

features in projects such as ENGLISH PROFILE (www.englishprole.org) will help to enrich the

model.

Such use of descriptors for SIGNPOSTING is common in EAQUALS, from a Greek primary

school (which makes use of an aims box on the whiteboard in each lesson, checklists

for teachers and report cards for parents), through language schools providing intensive

courses in-country and extensive courses at home (syllabus cross-referencing, checklists

for teacher/self-assessment), to a Turkish university (which denes exit levels and detailed

objectives, communication within faculty and with parents, and continuous teacher- and

self-assessment). Such signposting treats learners as partners in the learning and teaching

process. In Eurocentres intensive courses, every classroom has a standardised display of (a) the

scale of CEFRlevels, with dened sub-levels, (b) the detailed learning objectives for the CEFR

level in question (Our Aims) and (c) the communicative and related linguistic objectives of

the actual weeks work (Weekly Plan). The weekly plan is introduced by the teacher on the

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 26 Jun 2014 IP address: 79.143.86.44

2 3 4 P L E N A R Y S P E E C H E S

Monday, and a review lesson at the end of the week combines a quiz on the main linguistic

content with a small group discussion of achievement of the weeks objectives, and the need

for further class or individual work. At the end of the recent CEFR core inventory for general

English project that produced the scenario concept (North et al. 2010), the British Council

and EAQUALS team have summarised, for a similar purpose, using classroom posters, the

main descriptors, strategies, language points and sample exponents at each level.

3. Procedures for relating assessments to the CEFR

More and more schools and teachers are using the CEFRlevels to communicate with learners,

and examination boards increasingly refer to them. It is clear that what exactly is meant in

practice by a set of verbally dened levels of prociency like the CEFR Common Reference

Levels cannot be entirely separated from the current process of implementation, training

workshops, calibration of illustrative samples, adaptation of CEFR descriptors, and linking

of tests to the CEFR. However, the levels are not intended as a free-for-all for users to dene

as they wish. As was emphasised at the 2007 intergovernmental Language Policy Forum held

to take stock of the implementation of the CEFR, the levels should be applied responsibly,

especially if national systems and international certicates are being aligned to them(Council

of Europe 2007: 14). This means taking account of established sets of procedures, such as

those recommended in the Manual, when designing any linking project.

The fact that goodpractice guidelines are necessary for linking high-stakes assessment to the

CEFR can be demonstrated by a simple example. In response to the plethora of prociency

standards that have developed in the UK, two British researchers were commissioned to

produce a so-called alignment of all the different language prociency scales, including the

CEFR. The study, called Pathways to Prociency, claimed a relationship between CEFR

Level B1 and the British National Language Standards (BNLS) Level 2. As the authors state

(Department for Education and Skills 2003: 1214), this alignment was done on the basis of

no more research than placing the documents on a table next to each other and eyeballing

the descriptors. Even then, to my mind, the authors do not always seem to have selected

the most appropriate CEFR descriptor scales to compare to the British ones. If this rather

intuitive approach had been taken by a language education provider or publisher, this would

be a minor issue: their interpretation would be conrmed or adjusted over time. However, in

a nationally commissioned, high-stakes project, things are more serious. The English school-

leaving certicate, the GCSE, is placed at BNLS Level 2. The unsubstantiated suggestion

that BNLS Level 2 = GCSE = B1 is by no means entirely unconnected to the fact that in

February 2010 the UK Border Authority declared B1 to be the minimum for a UK student

visa (required for a stay of more than six months). As reported in the EL Gazette at the time,

GCSE was the comparison used in both the British Parliament and the press to justify the

measure. In fact a pass at GCSE (Grade C) is probably A2. The top Grade A supposedly

representing the standard of the previous O Level may be B1. Nobody knows exactly,

because nobody has bothered to do a study. However, the identication of GCSE with B1

helped to deny tens of thousands of language students the opportunity to come to the UK

and cost the British English Language teaching industry 10% of its business quite literally

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 26 Jun 2014 IP address: 79.143.86.44

B R I A N N O R T H : P U T T I N G T H E C E F R T O G O O D U S E 235

overnight and almost certainly erroneously. Even worse, the UKBorder Authority has since

proposed raising the minimum for a student visa from B1 to B2, a step which would have

dire consequences for the number of international students at UK universities.

The Manual recommends four sets of procedures for linking to the CEFR:

FAMILIARISATION, SPECIFICATION, STANDARDISATION and VALIDATION. In the context of

operational school assessment one could also put a special emphasis on MODERATION, to

limit and/or adjust for subjectivity in assessments by teachers.

3.1 Familiarisation

Familiarisation with the CEFR levels through training and awareness-raising exercises is

always necessary, as people tend to think they know the levels without consulting the

descriptors or ofcial illustrative samples. Instead they often associate the CEFR levels with

levels they already know. Familiarisation exercises normally involve descriptor sorting tasks,

but the most useful initial form of familiarisation is to see the levels in action in video

sequences such as those available online for English, French, Spanish, German and Italian

at www.ciep.fr/en/publi_evalcert/dvd-productions-orales-cecrl/index.php.

3.2 Specication

Specication in this context includes dening the coverage of the course or examination in

relation to the CEFR descriptor scales, in terms of both the curriculum and the assessment

tasks and criteria used to judge success in them. This involves selecting communicative

activities, perhaps guided by the descriptor scales in Chapter 4 of the CEFR (2001),

summarised in CEFR (2001: Table 2), designing tasks and writing items. Valid assessment

requires the sampling of a range of relevant discourse. For speaking, this normally means

combining interaction (spontaneous short turns) with production (prepared long turns); for

writing it may mean eliciting written-spoken language (interaction: email, SMS, personal

letter) as well as prose (production: essay, report). For listening and reading it may mean some

short pieces for identifying specic information (listening/reading for orientation) and one

or two longer pieces for detailed comprehension.

The formulation of criteria may or may not be related to the descriptors in Chapter 5 of

the CEFR (2001), which are summarised in CEFR (2001: Table 3). However, the criteria

should be balanced in terms both of extent of knowledge and degree of control and of

linguistic competence and pragmatic competence, as CEFR (2001: Table 3) attempts to do.

The assessment instrument might be a single grid of categories and levels, such as CEFR

(2001: Table 3), especially for standardisation training or a programme in which teachers

teach classes at different levels. Alternatively, it might focus only on the target level, with one

descriptor per chosen category; a simple example is given in Table 1. The advantage of this

approach is the ease with which the criteria can be explained to learners. This makes it easier

to highlight the COMPETENCES they must acquire for communicative success, rather than just

focusing on lists of things they CAN DO.

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 26 Jun 2014 IP address: 79.143.86.44

2 3 6 P L E N A R Y S P E E C H E S

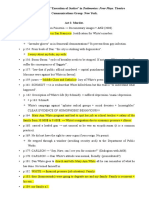

Table 1 Assessment at one level

Candidate A

RANGE & PRECISION: Can talk about familiar everyday

situations and topics, with searching for the words; sometimes has to

simplify.

1 2 3 4 5

ACCURACY: Can use some simple structures correctly in common

everyday situations.

1 2 3 4 5

FLUENCY: Can participate in a longer conversation about familiar

topics, but often needs to stop and think or start again in a different

way.

1 2 3 4 5

Note: 3 is the mark given if the learner exactly meets the criterion-descriptor; no more and no less.

3.3 Standardisation

Standardisation involves, rstly, training in a standard interpretation of the levels, using the

illustrative samples provided for that purpose and, secondly, the transfer of that standardised

interpretation to the benchmarking of local reference samples. It is important that these two

processes are not confused. In standardisation, participants are trainees being introduced

to or reminded of the levels, the criteria, the administration procedures, etc. External

authority is represented by the workshop leader, the ofcial criteria and the calibrated

samples. Standardisation training is not an exercise in democracy. The right answer, in

terms of standardising to an interpretation of the levels held in common internationally,

is not necessarily an arithmetic average of the opinions of those present, if they all come

from the same school or pedagogic culture. This is a tricky issue which needs to be handled

delicately. Personally, I have found it simplest to start by showing a calibrated, documented

video, allowing group discussion, handing out the documentation and then animating a

discussion of why (not whether) the learner is A2, B1 or whatever. The next stage can have

group discussions reporting views to a plenary session, and nally individual rating checked

with neighbours and then with the documentation.

In benchmarking, on the other hand, participants are valued, trained experts (although

very possibly the same people who did the standardisation training in the morning!). Here it

is important to record individual judgements before they are swayed in discussion by over-

dominant members of the group. Ideally, the weighted average of the individual judgements,

preferably corrected for inconsistency and severity/lenience with the IRTprogramFACETS,

(Linacre 1989; 2008) would yield the same result as the consensus reached in discussion. This

was the preferred method in the series of benchmarking seminars that produced most of the

CEFR illustrative video samples (Jones 2005; North & Lepage 2005).

3.4 Moderation

Moderation counteracts subjectivity in the process of rating productive skills. Even after

standardisation training has been implemented, moderation will always be necessary. Some

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 26 Jun 2014 IP address: 79.143.86.44

B R I A N N O R T H : P U T T I N G T H E C E F R T O G O O D U S E 237

assessors can be quite resistant to training, and, in any case, the effects of standardisation

also start to wear off immediately after the training. In addition, some assessors persist

in using personal concepts rather than the ofcial criteria as their reference. Many are

also unconsciously over-inuenced by one criterion (e.g. accuracy or pronunciation), and

most refuse to give a top or bottom grade (central tendency error). Moderation techniques

can be divided into collective and quality control techniques. Collective techniques involve

some form of double marking, perhaps of a structured sample of candidates (e.g. every

fth candidate, or (after rank ordering) the top three, middle three and bottom three

candidates. Rather than live double marking, recordings might be sent to chief examiners

for external monitoring. Administrative quality control techniques may involve studying

collateral information on the candidates on the one hand, or developing progress norms

from representative performance samples sent to the chief examiners on the other. Such

norms can then be used to identify classes whose grades differ signicantly from the norm,

for further investigation. These grades might genuinely be due to an unusually good/bad

teacher or an unusually strong/weak class but an apparent anomaly is worth following up.

Alternatively, scores from a standardised test may be used to smooth the results from teacher

assessment, in one form of statistical moderation.

3.5 EAQUALS Scheme

These techniques (familiarisation, specication, standardisation, moderation) have recently

been operationalised in a scheme under which EAQUALS-accredited language schools issue

EAQUALS CEFRCerticates of Achievement to learners at the end of a course. The scheme

requires the school to send the following materials for inspection by an expert panel, and the

schools assessment system is then checked in practice during the three-yearly EAQUALS

external inspections:

curriculum and syllabus documents with learning objectives derived from the CEFR

a coherent description of the assessment system

written guidelines for teachers

CEFR-based continuous assessment instruments

sample CEFR-based assessment tasks, tests and guidelines

CEFR-based criteria grids

a set of locally recorded, CEFR-rated samples to be double-checked by an EAQUALS

expert panel

samples of individual progress records

the content and schedule of staff CEFR standardisation training

details of the moderation techniques employed

3.6 Validation

Validation has two aspects: INTERNAL VALIDATION of the intrinsic quality of the assessment

and EXTERNAL VALIDATION of the claimed link to the vertical continuum of real-life language

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 26 Jun 2014 IP address: 79.143.86.44

2 3 8 P L E N A R Y S P E E C H E S

Table 2 A CEFR Manual Decision Table for validation of cut-scores on a Eurocentres item bank for

German (North 2000b)

Test (item bank)

A1

(1)

A2

(2 & 3)

B1

(4 & 5)

B2

(6 & 7)

C1

(8 & 9)

Total

A1

(1)

4 1 5

A2

(2 & 3)

14 4 18

B1

(4 & 5)

5 13 2 20

B2

(6 & 7)

3 16 19

C1

(8 & 9)

3 3 6

C

r

i

t

e

r

i

o

n

(

T

e

a

c

h

e

r

s

)

Total 4 20 20 21 3 68

ability operationalised in the CEFR descriptor scales. For reasons of space I shall only

discuss the latter, since the entire language testing literature concerns the former. Many

of the moderation techniques referred to above are simple forms of external validation:

the fundamental principle is to exploit collateral information and independent sources of

evidence. The advice in the Manual is to use two independent methods of setting the CUT

SCORES between levels. Then, if necessary, one can use a cyclical process of adjusting the cut

scores, examining them in the light of a DECISION TABLE like that shown in Table 2 in order to

arbitrate between two provisional results. The table shows a low-stakes (Eurocentres) worked

example cited in the Manual (Council of Europe 2009: 111113). Here the pattern was very

regular, with 73.5% matching classications, so no correction from the provisional cut scores

set for the item bank on the basis of item-writer intention seemed necessary.

This contrastive technique can be exploited in many different ways: for example,

contrasting the original claim based on item-writer intention against the result from formal

STANDARD SETTING (=ways of setting the cut scores); contrasting the results from two

independent standard-setting panels; contrasting the results from two different standard-

setting methods (e.g. between a test-centred and a candidate-centred method), and nally

conrming the result from standard-setting (or the original claim based on item-writer

intention) with a formal external validation study. For teacher assessment, the external

criterion could be operationalised in CEFR-related examination results for the same students;

for a test under study the external criterion could be ratings by CEFR-trained teachers of

the same students in relation to CEFR descriptors. In fact, many of the Manual case studies

recently published (Martyniuk 2010) did successfully use two methods in order to conrm

their claimto CEFRlinkage. Both the ECLstudy (Szabo 2010) and the TestDaf study (Kecker

& Eckes 2010) contrasted original item-writer intention with formal standard-setting; both

the City & Guilds study (OSullivan 2010) and the ECL study (Szabo 2010) contrasted

the mean average difculty of their own items with that of the illustrative items; both

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 26 Jun 2014 IP address: 79.143.86.44

B R I A N N O R T H : P U T T I N G T H E C E F R T O G O O D U S E 239

TestDaf study (Kecker & Eckes 2010) and the Bilkent COPE study (Thomas & Kantarcio glu

2009; Kantarcio glu et al. 2010) contrasted panel-based standard-setting results with external

teacher judgements of the candidates in relation to CEFR descriptors. The Surveylang study

(Verhelst 2009) contrasted results from a sophisticated data-based panel CITO BOOKMARK

METHOD (Council of Europe 2009: 8283) with external teacher CEFR judgements. Finally,

both the Pearson Test of English Academic (De Jong 2010) and the Oxford On-line Test

(Pollitt 2009) also contrasted item-writer intentions with external teacher judgements.

In contrast to these sensible approaches, Cizek & Bunch (2007), the current US text book

on standard-setting, explicitly advises against using two methods of standard-setting, because

these might yield different results. They state that a man with two watches is never sure and

use of multiple methods is ill advised (Cizek & Bunch 2007: 319320). Yet replication is the

basis of Western academic thought: if you cannot replicate a result you do not have a result.

Good practice would dictate corroboration of what is, for a high-stakes test, an important

decision that will affect many peoples lives.

4. Criterion-referencing and standard-setting

This reluctance to question the decision of a single panel highlights a general confusion

about standard-setting and criterion-referenced assessment. STANDARD-SETTING is very often

undertaken by a panel of experts who estimate the difculty level of items in order to set the

cut-score for pass/fail or different grades in a test. In EALTA, this conventional approach to

standard-setting seems to be considered essential for relating assessments to the CEFR. Eli

Moe, for example, in her paper at the EALTA standard-setting seminar in The Hague began

by saying:

Although everyone agrees that standard-setting is a must when linking language tests to the CEFR, we

hear complaints about the fact that standard-setting is expensive both in respect to time and money. In

addition, it is a challenge to judges not only because the CEFR gives little guidance on what characterises

items mirroring specic levels, but also because time seldom seems to increase individual judges chances

of success in assigning items to CEFR levels. (Moe 2009: 131)

However, neither I myself nor Neil Jones nor John De Jong, to name but three people

present, would agree that panel-based standard-setting is a must when linking tests to the

CEFR. The preliminary Manual (Council of Europe 2003) made it clear that it was perfectly

feasible to jump fromthe specicationphase direct to the kind of empirical, external validation

discussed in the previous section without bothering with panel-based standard-setting at all. It

recommended using the judgements of CEFR-trained teachers for validation and presented

box plots and bivariate decision tables provided by Norman Verhelst, the Cito statistical

expert from the DIALANG project, as useful tools in that process. When I met Norman

at the rst meeting of the Manual group, we actually had a one-hour discussion in which I

expressed my difculty in buying the idea that someone with his experience of ITEMRESPONSE

THEORY (Rasch modelling, henceforth IRT) could seriously believe that such guesstimation

by panels really worked.

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 26 Jun 2014 IP address: 79.143.86.44

2 4 0 P L E N A R Y S P E E C H E S

Validating the relationship of a test to the CEFR requires what is technically known as

LINKING to the continuum of ability acting as the criterion. In our current discussion, the

validated CEFR descriptor scale provides that continuum. Criterion-referenced assessment

(CR) places persons on such a continuum, independent of the ability of others. This is in

contrast to norm-referenced assessment, in which the ability of candidates is evaluated relative

to that of their peers, or to a standard set in relation to their peer cohorts over many years.

CR was developed by Robert Glaser in a seminal article from which the crucial passage is

the following:

Along . . . a continuum of attainment, a students score on a CR measure provides explicit information

as to WHAT THE INDIVIDUAL CAN AND CANNOT DO.

CR measures indicate (. . .) the correspondence between what an individual does and the UNDERLYING

CONTINUUM OF ACHIEVEMENT. Measures whichassess student achievement interms of a criterionstandard

thus provide information as to the degree of competence attained by a particular student which is

INDEPENDENT OF REFERENCE TO THE PERFORMANCE OF OTHERS. (Glaser 1963: 519520; emphasis added)

This is not at all where the conventional, US-style standard-setting represented by Cizek

& Bunch (2007) is coming from. In the US, CR started in the 1960s, at almost exactly the

same time as the behaviourist instructional objectives movement, so unfortunately the two

concepts merged in setting the PERFORMANCE STANDARD for MASTERY LEARNING in the US

MINIMUM COMPETENCE approach (Glaser 1994a: 6; 1994b: 9; Hambleton 1994: 22). Such a

performance standard is actually a norm: a denition of what it might be reasonable to expect

from a newly qualied professional, or from a ninth-year high school student in a specic

subject in a specic context. Over time that norm-referenced standard became confused

with the criterion which is supposed to be the continuum of real-world ability. This is an

important point, because it means that the referencing of the assessment became entirely

internal; the link to the continuum of ability in the area concerned in the world outside

had been lost. Standard-setting in North America then became the process of setting the

pass/fail norm for minimum competence on a multiple-choice test assessing a given body of

knowledge in the subject concerned for the particular school year or professional qualifying

exam.

Since it was the subject experts (panel of expert nurses; committee of ninth-year teachers)

who dened that body of knowledge, they were also in a position to give an authoritative

judgement on whether the test was fair. FAIRNESS relates to what such experts feel it is

reasonable to expect from a specic cohort of candidates in relation to the closed domain

of knowledge concerned. Whether an individuals result is considered to be good or bad

therefore depends entirely on how that result relates to the score set as the expected norm for

their cohort. This is fair enough. However, it is neither criterion-referenced assessment nor

PROFICIENCY ASSESSMENT in the sense in which the word prociency is used in the expression

LANGUAGE PROFICIENCY. There is no relationship to an external criterion: the continuum of

ability. The referencing is purely internal: to what is fair; to what was taught.

As Jones (2009: 36) pointed out in his paper at the EALTA standard-setting seminar, there

really is almost nothing in common between setting such a pass norm for a closed domain

of subject knowledge, on the one hand, and linking a language test to the continuum of

language prociency articulated by the CEFR, on the other. In addition, as Reckase (2009:

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 26 Jun 2014 IP address: 79.143.86.44

B R I A N N O R T H : P U T T I N G T H E C E F R T O G O O D U S E 241

18) suggested in his EALTA presentation, panel-based methods were not designed for the

multiple cut-scores necessary for linking results to different language prociency levels; there

is an inevitable dependency between the decisions.

Nevertheless, 23 out of the 26 articles on case studies of relating tests to the CEFR

in Martyniuk (2010) and Figueras & Noijons (2009) took a panel-based standard-setting

approach, mostly citing Cizek & Bunch (2007). Fortunately, as mentioned earlier, many also

replicated their panel-based ndings with a second method. However, the predominance of

panel-based standard-setting demonstrates the extent to which many language testers and

many people involved in linking assessments to the CEFR are not aware of the confusion

between criterion-referencing and mastery learning described above, nor that panel-based

standard-setting is a norm-referencing technique, nor that it is not innately suitable as a

means for setting multiple cut-scores on a test. Nor are many language testers aware that

there is 30 years of literature suggesting that such panel-based standard-setting is awed, even

within its own context (e.g. Glass 1978: 240242; Impara & Plake 1998: 79).

These problems with estimations by panels have recently been rediscovered in an EALTA

context (Kaftandjieva 2009) in the evaluation of the so-called BASKET METHOD used in the

DIALANG project and included in the preliminary, pilot version of the Manual. The basket

method is one of many variants on the classic ANGOFF METHOD of standard-setting through

estimation of itemdifculty by a panel. Whereas the Angoff Method asks panellists to estimate

percentages, the Basket Method takes a simpler approach. It asks each panel member to

decide which basket (A1, A2, etc.) to put the item in, by posing and answering a question

like At which CEFR level will a candidate rst be able to answer this question correctly?

Many variants of the Angoff method feed data to panellists between rounds of estimation.

Usually data is provided on ITEM DIFFICULTY (facility values or IRT theta values) and then

on IMPACT (How many people would fail if we said this?) and the provision of such data was

in fact recommended in the preliminary Manual. As Kaftandjieva (2009: 30) indicates, such

a modied basket method works much better. But to my mind this approach really amounts

to little more than an exercise in damage limitation. If people cannot accurately guess the

difculty of items without being given empirical data, why not use the empirical data to

determine difculty in the rst place? If, in order to avoid excessive strictness or leniency and

arrive at a sensible result, panellists need data on what percentage of the candidates fail as a

result of their guesswork, can one place any faith at all in the judgements?

This point is illustrated by the attempts made by ETS to relate TOEFL to the CEFR.

After a 2004 panel-based standard-setting project to relate ETS exams to the CEFR using

a classic Angoff method (Tannenbaum & Wylie 2004), TOEFL reported that 560 on the

paper-based TOEFL (PBT), the equivalent of 83 on the internet-based test (iBT), was the

cut-score for C1 (ETS 2004). On their website, ETS currently report equivalences based on

a second panel-based study (Tannenbaum & Wylie 2008) and state that iBT 5786 (PBT

487567) is B1 (ETS 2008). That is to say, according to the guesstimates of the rst panel,

PBT 560567 is B1 and according to the guesstimates of the second panel, PBT 560567

is C1. A similar switch occurs with the claimed equivalences for TOEIC. Common sense,

the corroboration technique from the CEFR Manual illustrated in Table 1, the comparative

scores that ETS publish on their website for IELTS (IELTS 6.5 =iBT 7993/PBT 550583)

and Eurocentres institutional experience of working with IELTS, TOEFL and the CEFR

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 26 Jun 2014 IP address: 79.143.86.44

2 4 2 P L E N A R Y S P E E C H E S

would all suggest that 560567 might well be somewhere between the two results, i.e. B2. But

Tannenbaum & Wylie are not interested in corroboration. They fail to mention the results of

the rst study, though they refer to its existence (2008: 11); they cite Cizek & Bunchs (2007)

dismissal of comparing two results as grounds for not undertaking an external validation study

using teacher ratings of CEFRprociency to obtain convergent evidence, as recommended in

CEFR Manual (2008: 30). They even see no need to demonstrate through the specication

procedures recommended in the CEFR manual that TOEFL has any content link to the

CEFR either (2008: 3).

The ETS approach to CEFR linking was heavily criticised at the EALTA meeting in

Sitges in 2007 because it completely ignored the procedures recommended in the Manual

(specication and external validation in addition to conventional standard-setting) and their

own experience of linking TOIEC to the American ILR (Interagency Language Roundtable)

scale through ratings of candidates with descriptors from the scale. This criticism appears

to have prompted the second study but not, unfortunately, an understanding of the need to

corroborate claims, lay open ndings and resolve contradictions. Above all there is a complete

failure to appreciate that CALIBRATING TO A COMMON CRITERIONrequires a different approach

from traditional US methods for setting a pass score on a test. In a context in which the UK

Border Authority is using the CEFR to set the prociency threshold needed in order to

receive a student visa to undertake higher education in the UK, knowing whether TOEFL

560567 is B1, B2 or C1 is not an academic matter.

5. Calibrating to a common criterion

The fundamental problem is that the panel-based approach normally estimates the difculty

of the items in a single form of the test by a single panel. Yet examination institutes should be

relating their REPORTING SCALE to the external criterion provided by the CEFR descriptor

scale so as to guarantee the link over different test administrations. They should not be relating

items on one particular test form on the basis of the views of one particular panel. This is

essentially the problem with the TOEFL projects. Best practice in linking a high-stakes test

to the CEFR involves CALIBRATING THE SCALE BEHIND THE TEST or suite of tests to the CEFR

with what is technically called VERTICAL SCALING or vertical equating using IRT. Simple

introductions to IRT are offered by Baker (1997), McNamara (1996) and Henning (1987).

Cizek & Bunch (2007), however, devote just 7% of their text to the issue of standards at

different stages on a continuum of ability only to then reject the concept. They discuss

what they describe as VERTICALLY MODERATED STANDARD-SETTING (VMSS), which is a way

of smoothing out infelicities when stringing together a series of norms for different school

years, each determined independently by standard-setting panels. They conclude that none

(of the VMSS methods) have any scientic or procedural grounding to provide strong support for

its use (Cizek & Bunch 2007: 297). Vertical scaling to a continuum of ability (IRT) they reject

out of hand on the basis of a study by Lissitz & Huynh (2003). Yet Lissitz & Huynh cited six

specic reasons why vertical scaling with IRT was inappropriate FOR THEIR CONTEXT. Only

one of them the fact that it is technically complicated actually applies to the context of

relating language assessments to the CEFR.

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 26 Jun 2014 IP address: 79.143.86.44

B R I A N N O R T H : P U T T I N G T H E C E F R T O G O O D U S E 243

There is a literature on linking assessments, and Angoffs (1971) article which initiated

conventional panel-based standard-setting was part of this literature. It was entitled Scales,

norms and equivalent scores. The so-called Angoff standard-setting method was in fact a

remark in a footnote. That footnote was written 1520 years before computer development

made practicable the scaling and the establishment of equivalent scores that IRT promised.

But there were other equating methods before IRT became widespread.

Before becoming involved in the development of the Manual, I wrote a modest article

(North 2000b) which described how over the years various people in Eurocentres had

addressed the question of equating tests and linking them to the Eurocentres scale of

prociency, a precursor of the CEFR descriptor scale. I had read most of the then standard-

setting literature in bibliographic research before the development of the CEFR descriptor

scale, but didnt see how panel-based, judgemental methods were relevant to a common

framework scale of levels, except for rating spoken and written samples. Even then it seemed

clear that the many-faceted variant of IRT scaling (Linacre 1989, 2008) would be needed to

handle inconsistency and subjectivity on the part of the experts operating as raters. This was

the approach applied after extensive qualitative research on the descriptors in the CEFR

research project (North 2000a) and in calibrating the CEFR illustrative spoken samples

(North & Lepage 2005; Breton, Lepage & North 2008).

I certainly think that the experience of participating in standard-setting seminars is a very

enriching one. It is good and very valuable practice for a team of test developers and item

writers to consciously evaluate and judge the difculty of items and then be confronted

with empirical data on item difculty. As Moe (2009: 137) suggests, this process may also

help make the levels more concrete by teasing out their criterial features. But why use

such guesstimation to set cut-scores? There is a data-based alternative that exploits vertical

scaling and the assessments of learners by CEFR-trained teachers. As mentioned above, the

technique has been used in several CEFR linking projects (Oxford Online Placement Test:

Pollitt 2009; Pearson Tests of English: De Jong 2010; the UKLanguages Ladder project: Jones

et al. 2010; the TestDaf study: Kecker & Eckes 2010; and the European Survey of Language

Competence: Verhelst 2009). The technique is explained in the Further Material (North &

Jones 2009) provided to accompany the Manual, which is buried in the small print on the

Council of Europes website (www.coe.int/lang), sandwiched between the link to the Report

of the CEFR Forum underneath the presentation of the Manual and the text introducing the

Reference Supplement. I thoroughly recommend it to you.

6. Conclusion

The CEFRis a useful heuristic tool, but it is not the answer to all problems. It is an inspiration,

not a panacea. It needs further exemplication, as in the banks of illustrative descriptors and

samples on the Council of Europes website and the more elaborated C2 descriptors that one

hopes will be provided by English Prole. It requires the elaboration of content for different

languages, as in the REFERENCE LEVELS for German, French, Spanish and Italian and in the

recently published British Council/EAQUALS Core Inventory for General English (North

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 26 Jun 2014 IP address: 79.143.86.44

2 4 4 P L E N A R Y S P E E C H E S

et al. 2010), not to mention the insights that one again hopes will be provided by the corpus-

based English Prole.

The CEFR is also considerably more than just a set of prociency levels, even though it is

the levels that tend to gain the most attention. In fact, whilst remaining as methodologically

neutral as possible, the CEFR presents a distinct philosophy of language teaching and

learning. This focuses on analysing the real-world future needs of the learner as a language

user and ondeveloping the different competences, including intercultural competences, which

will be helpful in meeting those needs. It further suggests treating learners as partners, rstly

by dening learning aims clearly in terms of the most relevant activities (CEFR2001: Chapter

4) and competences (CEFR 2001: Chapter 5) and, secondly, by discussing with learners their

priorities and achievement in relation to those communicated aims.

As regards the levels, there is no ofcial way of linking tests to them. There is a Manual;

there is what is in effect a minority report from the Manual team (see North & Jones 2009),

and there is a further impressive body of work undertaken by ALTE, by Cambridge ESOL

(e.g. Khalifa & Weir 2009; Khalifa, ffrench & Salamoura 2010) and by members of EALTA.

Fundamentally the CEFR, the Manual, the Further Material, the Reference Levels,

the descriptor banks and the illustrative samples are all reference tools TO BE CRITICALLY

CONSULTED, NOT TO BE APPLIED. The boxes at the end of each CEFR chapter invite users

to REFLECT on their current practice and how it relates to what is presented in the CEFR.

The authors of many of the case studies published in Martyniuk (2010) on relating tests to

the CEFR state that the activity of undertaking the project led them into such a process of

reection and reform. It is just such a process that the CEFR was designed to stimulate.

References

Alderson, J. C. (ed.) (2002). Case studies in the use of the Common European Framework. Strasbourg: Council

of Europe.

Alderson, J. C. (2007). The CEFR and the need for more research. The Modern Language Journal 91.4,

659662.

Angoff, W. H. (1971). Scales, Norms and Equivalent Scores. In R. L. Thorndike (ed.) Educational

measurement. Washington DC: American Council on Education, 508600.

Baker, R. (1997). Classical test theory and item response theory in test analysis. Extracts from an investigation of the

Rasch model in its application to foreign language prociency testing. Language Testing Update Special Report

No 2. Lancaster, CRILE, Department of Linguistics and Modern English Language.

Breton, G., S. Lepage & B. North (2008). Cross-language benchmarking seminar to calibrate examples of spoken

production in English, French, German, Italian and Spanish with regard to the six levels of the Common European

Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR). CIEP, S` evres, 2325 June 2008. Strasbourg: CIEP/Council

of Europe, www.coe.int/lang.

Byrnes, H. (ed.) (2007). The Common European Framework of Reference. The Modern Language Journal

91.4, 641685.

Cizek, G. J. & M. B. Bunch (2007). Standard setting: A guide to establishing and evaluating performance standards

on tests. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Council of Europe (2001). Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, teaching, assessment.

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Council of Europe (2003). Relating language examinations to the Common European Framework of Reference for

Languages: Learning, teaching, assessment (CEFR). DGIV/EDU/LANG (2003) 5, Strasbourg: Council of

Europe.

Council of Europe (2007). The Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR) and

the development of language policies: Challenges and responsibilities. Intergovernmental Language Policy

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 26 Jun 2014 IP address: 79.143.86.44

B R I A N N O R T H : P U T T I N G T H E C E F R T O G O O D U S E 245

Forum, Strasbourg, 68 February 2007. www.coe.int/t/dg4/linguistic/Forum07_webdocs_EN.

asp

Council of Europe (2009). Relating language examinations to the Common European Framework of Reference for

Languages: Learning, teaching, assessment (CEFR). Strasbourg: Council of Europe. www.coe.int/t/dg4/

linguistic/Manuel1_EN.asp

De Jong, J. (2010). Aligning PTE Academic score results to the Common European Framework of Reference for

Languages. http://pearsonpte.com/research/Documents/AligningPTEtoCEF.pdf

Department for Education and Skills (2003). Pathways to prociency: The alignment of language prociency scales

for assessing competence in English language. QCA/DfES Publications. http://rwp.excellencegateway.

org.uk/readwriteplus/bank.cfm?section=549

ETS(2004). Mapping TOEFL, TSE, TWE, and TOIECon the Common European Framework, Executive summary.

18 March, 2011. www.besig.org/events/iatepce2005/ets/CEFsummaryMarch04.pdf

ETS (2008). Mapping TOEFL iBT on the Common European Framework of Reference, Executive summary.

18 March, 2011. www.ets.org/toe/research

Figueras, N. & J. Noijons (eds.) (2009). Linking to the CEFR levels: Research perspectives. Arnhem: Cito-

EALTA.

Glaser, R. (1963). Instructional technology and the measurement of learning outcomes: Some

questions. American Psychologist 18.8, 519521.

Glaser, R. (1994a). Instructional technology and the measurement of learning outcomes: Some

questions. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice 13.4, 68.

Glaser, R. (1994b). Criterion-referenced tests: Part 1. Origins. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice

13.4, 911.

Glass, G. V. (1978). Standards and criteria. Journal of Educational Measurement 15.4, 237261.

Hambleton, R. K. (1994). The rise and fall of criterion-referenced measurement? Educational

Measurement: Issues and Practice 13.4, 2126.

Harmer, J. (1998). How to teach English. Harlow, UK: Longman.

Henning, G. (1987). A guide to language testing. Development, evaluation, research. New York: Newbury House.

Impara, J. C. &B. S. Plake (1998). Teachers ability to estimate itemdifculty: Atest of the assumptions

in the Angoff standard-setting method. Journal of Educational Measurement 35.1, 6981.

Jones, N. (2002). Relating the ALTE Framework to the Common European Framework of Reference.

In Alderson, (ed.), 167183.

Jones, N. (2005). Seminar to calibrate examples of spoken performance. CIEP, S` evres, 24 December, 2004.

Report on analysis of rating data, nal version. 1 March, 2005. www.coe.int/lang.

Jones, N. (2009). A comparative approach to constructing a multilingual prociency framework

constraining the role of standard-setting. In Figueras & Noijons, (eds.), 3544.

Jones, N., K. Ashton & T. Walker (2010). Asset languages: A case study of piloting the CEFR manual.

In Martyniuk, (ed.), 227248.

Kaftandjeva, F. (2009). Basket procedure: The breadbasket or the basket case of standard-setting

methods? In Figueras & Noijons, (eds.), 2134.

Kaftandjieva, F. & S. Takala (2002). Council of Europe scales of language prociency: A validation

study. In Alderson, (ed.), 106129.

Kantarcio gu, E., C. Thomas, J. ODwyer & B. OSullivan (2010). Benchmarking a high-stakes

prociency exam: The COPE linking project. In Martyniuk, (ed.), 102118.

Kecker, G. & T. Eckes (2010). Putting the manual to the test: The TestDafCEFR linking project. In

Martyniuk, (ed.), 5079.

Keddle, J. S. (2004). The CEF and the secondary school syllabus. In K. Morrow (ed.), Insights from the

Common European Framework. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 4354.

Khalifa, H. & C. Weir (2009). Examining reading: Research and practice in assessing second language reading.

Studies in Language Testing 29. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Khalifa, H., A. ffrench & A. Salamoura (2010). Maintaining alignment to the CEFR: The FCE case

study. In Martyniuk, (ed.), 80102.

Lado, R. (1961). Language testing. London: Longman.

Linacre, J. M. (1989). Multi-faceted measurement. Chicago: MESA Press.

Linacre, J. M. (2008). A users guide to FACETS, Rasch model computer program. www.winsteps.com.

Lissitz, R. W. & H. Huynh (2003). Vertical equating for state assessments: Issues and solutions in

determination of adequate yearly progress and school accountability. Practical Assessment: Research &

Evaluation 8.10. http://pareonline.net/getvn.asp?v=8&n=10.

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 26 Jun 2014 IP address: 79.143.86.44

2 4 6 P L E N A R Y S P E E C H E S

Little, D. (2005). The Common European Framework and the European Language Portfolio: Involving

learners and their judgements in the assessment process. Language Testing 22.3, 321336.

Martyniuk, W. (ed.) (2010). Aligning tests with the CEFR: Reections on using the Council of Europes draft manual.

Studies in Language Testing 33. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

McNamara, T. (1996). Measuring second language performance. London and New York: Longman.

Moe, E. (2009). Jack of more trades? Could standard-setting serve several functions? In Figueras &

Noijons, (eds.), 131138.

Norris, J. M. (2005). Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, teaching,

assessment. Language Testing 22.3, 399406.

North, B. (1995). The development of a common framework scale of descriptors of language prociency

based on a theory of measurement. System 23, 445465.

North, B. (1997). Perspectives on language prociency and aspects of competence. Language Teaching

30, 92100.

North, B. (2000a). The development of a common framework scale of language prociency. New York: Peter Lang.

North, B. (2000b). Linking language assessments: An example in a low stakes context. System 28,

555577.

North, B. (2002). A CEF-based self-assessment tool for university entrance. In Alderson, (ed.),

146166.

North, B. & N. Jones (2009). Relating language examinations to the Common European Framework of Reference

for Languages: Learning, teaching, assessment (CEFR): Further material on maintaining standards across languages,

contexts and administrations by exploiting teacher judgment and IRT scaling. Strasbourg: Council of Europe.

www.coe.int/t/dg4/linguistic/Manuel1_EN.asp

North, B. & S. Lepage (2005). Seminar to calibrate examples of spoken performances in line with the scales of the

Common European Framework of Reference for Languages. CIEP, S` evres, 24 December, 2004. Strasbourg:

Council of Europe, www.coe.int/lang.

North, B. & G. Schneider (1998). Scaling descriptors for language prociency scales. Language Testing

15.2, 217262.

North, B.,

A. Ortega Calvo & S. Sheehan (2010). British CouncilEAQUALS core inventory for General

English. London: British Council/EAQUALS. www.teachingenglish.org.uk and www.eaquals.org

Ortega Calvo,

A. (2010). Qu e son en realidad los niveles C? Desarrollo de sus descriptores en el

MCER y el PEL. In Ortega Calvo (ed.), Niveles C: Currculos, programaci on, ense nanza y certicaci on.

Madrid: IFIIE Ministerio de Educaci on, 2185.

OSullivan, B. (2010). The City & Guilds Communicator examination linking project: A brief overview

with reections on the process. In Martyniuk, (ed.), 3349.

Pollitt, A. (2009). The Oxford Online Placement Test: The meaning of OOPT scores. Oxford: Oxford University

Press. www.oxfordenglishtesting.com.

Reckase, M. D. (2009). Standard-setting theory and practice: Issues and difculties. In Figueras &

Noijons, (eds.), 1320.

Schneider, G., B. North & L. Koch (2000). A European language portfolio. Berne: Berner Lehrmittel- und

Medienverlag.

Szabo, G. (2010). Relating language examinations to the CEFR: ECL as a case study. In Martyniuk,

(ed.), 133144.

Takala, S. (2009) (ed.). Relating language examinations to the Common European Framework of Reference for

Languages: Learning, teaching, assessment (CEFR): Reference supplement. Strasbourg: Council of Europe.

www.coe.int/t/dg4/linguistic/Manuel1_EN.asp

Tannenbaum, R. J. &E. C. Wylie (2004). Mapping test scores onto the Common European Framework:

Setting standards of language prociency on the Test of English as a Foreign Language (TOEFL),

the Test of Spoken English (TSE), the Test of Written English (TWE) and the Test of English for

International Communication (TOEIC). Princeton NJ: Educational Testing Service, April 2004.

18 March, 2011. www.ets.org/Media/Tests/TOEFL/pdf/CEFstudyreport.pdf

Tannenbaum, R. J. & E. C. Wylie (2008). Linking English language test scores onto the Common

European Framework of Reference: An application of standard-setting methodology. Princeton NJ:

Educational Testing Service, TOEFL iBTResearch Report RR0834, June 2008. 18 March, 2011.

www.ets.org/Media/Research/pdf/RR-08-34.pdf

Thomas, C. & E. Kantarcio glu (2009). Bilkent University School of English language COPE CEFR

linking project. In Figueras & Noijons, (eds.), 119124.

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 26 Jun 2014 IP address: 79.143.86.44

B R I A N N O R T H : P U T T I N G T H E C E F R T O G O O D U S E 247

Verhelst, N. (2009). Linking multilingual survey results to the Common European Framework of

Reference. In Figueras & Noijons, (eds.), 4558.

Weir, C. (2005). Limitations of the CommonEuropeanFramework for developing comparable language

examinations and tests. Language Testing 22.3, 281300.

BRIAN NORTH is Head of Academic Development at Eurocentres, the Swiss-based foundation with

language schools in countries where the languages concerned are spoken. He was co-author of the

CEFR and prototype European Language Portfolio, developer of the CEFR descriptor scales and

coordinator of the CEFR Manual team. From 2005 to 2010 he was Chair of EAQUALS (European

Association for Quality Language Services). He has led the EAQUALS Special Interest Projects (SIPs)

in the areas of Curriculum and Assessment since 2007. Both EAQUALS and Eurocentres are NGO

consultants to the Council of Europe Language Policy Division.

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 26 Jun 2014 IP address: 79.143.86.44

2

4

8

P

L

E

N

A

R

Y

S

P

E

E

C

H

E

S

Appendix 1a Scenario: Business meeting

DOMAIN CONTEXT TASKS ACTIVITIES TEXTS

Occupational Organisation: Multinational

corporation

Location: Office

Persons: Colleagues

Attending meeting

Contributing opinion on other

proposal

Making own proposal

Listening as member of live

audience

Spoken Production

Spoken Interaction

Sustained monologue

PowerPoint presentation

Formal discussion

LEVEL B2 COMPETENCES

CAN-DOS* Follow the discussion on matters related to his/her field, and

understand in detail the points given prominence by the

speaker.

Contribute, account for and sustain his/her opinion, evaluate

alternative proposals, and make and respond to hypotheses.

Give clear, detailed descriptions and presentations on a wide

range of subjects related to his/her field of interest.

Develop a clear argument, expanding and supporting his/

her points of view at some length with subsidiary points and

relevant examples.

STRATEGIC Intervene appropriately, using a variety of expressions to do so.

Follow up what people say, relating contribution to those of others.

Overcome gaps in vocabulary with paraphrases and alternative expressions.

Monitor speech to correct slips and mistakes.

CRITERIA*

PRAGMATIC Functional Expressing abstract ideas

Giving precise information

Speculating

Developing an argument

Justification

APPROPRIATENESS Can express himself / herself appropriately in situations and

avoid crass errors of formulation.

COHERENCE Can use a variety of linking words efficiently to mark clearly

the relationships between ideas.

Discourse Formal Speech Markers

Complex sentences

Addition, sequence and contrast

(although; in spite of; despite; on the one hand)

Summarising

FLUENCY Can produce stretches of language with a fairly even tempo;

although he/she can be hesitant as he/she searches for

patterns and expressions, there are few noticeably long

pauses.

LINGUISTIC Grammatical Modals of deduction in the past

All passive forms

All conditionals

Collocation of intensifiers

Wide range of (complex) NPs

RANGE Has a sufficient range of language to be able to give clear

descriptions, express viewpoints and develop arguments

without much conspicuous searching for words, using some

complex sentence forms to do so.

Lexical Work-related collocations

Extended phrasal verbs

Phonological Intonation patterns

* Taken verbatim from the CEFR. Portfolio or schools adapted descriptors might be used.

Implementation: Howard Smith

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 26 Jun 2014 IP address: 79.143.86.44

B

R

I

A

N

N

O

R

T

H

:

P

U

T

T

I

N

G

T

H

E

C

E

F

R

T

O

G

O

O

D

U

S

E

2

4

9

Appendix 1b : Scenario implementation

Competence(s) Learning context Activity Materials

Engage

Formal speech markers.

Intervene appropriately, using a variety of expressions to do so.

Follow up what people say, relating contribution to those of others.

Classroom

whole class

/group discussion

Watch TV business reality show discussion discuss which contestant they

find more persuasive analyse language to identify features marking formal

discussion, relating contribution and persuasion.

Recorded/online episode

of reality show.

Grammar: conditionals

Speculating

Developing an argument

Justifying