Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

12 - 4 - JMP - 2006

Enviado por

Daniela Arsenova LazarovaTítulo original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

12 - 4 - JMP - 2006

Enviado por

Daniela Arsenova LazarovaDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

RESEARCH NOTE

Gender and age differences in

occupational stress and

professional burnout between

primary and high-school teachers

in Greece

A.-S. Antoniou

Research Centre of Psychophysiology and Education,

National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Athens, Greece

F. Polychroni

Department of Psychology, School of Philosophy,

National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Athens, Greece, and

A.-N. Vlachakis

Department of Psychology, Panteion University of Social and Political Sciences,

Athens, Greece

Abstract

Purpose To identify the specic sources of occupational stress and the professional burnout

experienced by teachers working in Greek primary and secondary schools. A special emphasis is given

to gender and age differences.

Design/methodology/approach A cross-sectional design was used. Two self-report measures

were administered to a sample of 493 primary and secondary school teachers, a self-report

rating scale of specic occupational stressors and the Maslach Burnout Inventory (education

version).

Findings The most highly rated sources of stress referred to problems in interaction with

students, lack of interest, low attainment and handling students with difcult behaviour.

Female teachers experienced signicantly higher levels of occupational stress, specically

with regard to interaction with students and colleagues, workload, students progress and

emotional exhaustion. Younger teachers experienced higher levels of burnout, specically in terms

of emotional exhaustion and disengagement from the profession, while older teachers

experienced higher levels of stress in terms of the support they feel they receive from the

government.

Practical implications The ndings will help to implement effective primary and secondary level

prevention programmes against occupational stress taking into account how males and females and

younger and older teachers perceive stress at work.

Originality/value The study is a signicant addition to the teacher stress and burnout literature,

especially in Greece where few relevant studies exist dealing with these problems.

Keywords Greece, Teachers, Stress, Gender, Discrimination

Paper type Research paper

The current issue and full text archive of this journal is available at

www.emeraldinsight.com/0268-3946.htm

JMP

21,7

682

Received May 2005

Revised April 2006

Accepted June 2006

Journal of Managerial Psychology

Vol. 21 No. 7, 2006

pp. 682-690

qEmerald Group Publishing Limited

0268-3946

DOI 10.1108/02683940610690213

Research on stress and burnout among teachers has recently received considerable

attention (Travers and Cooper, 1993). Numerous studies have explored the specic

conditions that make teaching stressful. These conditions can be categorised either as

exogenous (i.e. unfavourable occupational conditions, excessive workload, lack of

collaboration, etc.) or endogenous pressures (i.e. individual personality characteristics,

disappointment and frustration that probably stem from unrealistic expectations that

teachers hold, etc.). A long-term consequence of stress is occupational burnout, which

is dened as a syndrome that results from chronic and extended occupational stress,

characterised by physical, emotional and attitudinal exhaustion (Kyriacou, 1987).

In Firth-Cozenss and Paynes (1999) review of 43 studies carried out in the US between

1979 and 1998, teachers were classied rst in terms of levels of emotional exhaustion

compared with other professional groups of the study. The consequences of

occupational stress and burnout are particularly grave for individuals who work in

health and social services (Antoniou, 1999; Antoniou et al., 2003) and this has been a

major concern of human service and helping professionals.

A considerable number of studies both in mainstream (Brouwers and Tomic, 2000;

Jaoul et al., 2004) and in special education settings (Antoniou et al., 2000; Jennett et al.,

2003) and at primary and secondary level (Carlile, 1985; Cooper and Kelly, 1993) have

identied the major sources of teachers occupational stress. These can be categorized

as follows:

.

Factors that directly concern the nature of teaching profession. The major stress

factors are anchored in the in-class structure rather than in the organizational

structure. Disciplinary problems, class heterogeneity, and work overload (Male

and May, 1998; Lewis, 1999; Forlin, 2001) can affect the teachers.

.

Individual differences that inuence teachers vulnerability against stress. Stress

levels may differ in relation to age and gender. It is documented that younger

teachers present higher levels of emotional exhaustion and depersonalisation as

compared to their older colleagues. This reaction is probably related with the

young teachers difculty to activate the appropriate coping strategies in order to

reduce the occupational stress imposed by the difculties of their job (Byrne,

1991; Travers, n.d.). Moreover, female teachers experience higher levels of stress

and higher job dissatisfaction that generally stem from the negative conditions in

the classroom and the students behaviour, as well as work-family interface

(Georgas and Giakoumaki, 1984; Offerman and Armitage, 1993; Kantas, 2001).

.

Administrative factors that are related to the school organisation and

administration. Limited support from the government, inadequate training,

lack of information on contemporary educational issues, continuous changes in

the curriculum and excessive demands from school administration and difculty

in interacting with parents, constitute serious sources of stress and exhaustion

for teachers (Travers and Cooper, 1997; Forlin, 2001).

The limited available studies regarding the levels of occupational stress and burnout of

Greek teachers (Papastylianou, 1997; Antoniou et al., 2000; Kantas, 2001), have

indicated that Greek teachers experience considerably high levels of stress and

psychosomatic symptoms. In order to investigate the levels of stress and burnout in the

Greek population, the present study aimed to identify the specic sources of

occupational stress of Greek primary and secondary school teachers, to assess their

Occupational

and professional

burnout

683

levels of professional burnout and the way that stress and burnout vary in terms of age

and gender.

Methodology

About 493 Greek teachers (43.8 per cent males and 56.2 per cent females) of public

primary (49.7 per cent) and secondary (50.3 per cent) schools working in large cities

in Greece participated in the study. The teachers age ranged from 25 to 65 years

(34.7 per cent aged between 41 and 50 years). The majority of teachers were married

and the majority of the sample had been teaching from 1 to 10 years.

A questionnaire on the specic sources of teachers occupational stress was used,

which included 30 statements referring to particular stressful situations for teachers.

Teachers identify the level of stress that they experience at a six-point Likert-type scale

ranging from 1 it is not stressful at all to 6 it is very stressful (reliability was

calculated at a 0.92). Professional burnout was assessed by the Maslach Burnout

Inventory (MBI ED version for teachers) developed by Maslach and Jackson (1986).

This scale has been used before with Greek teaching populations (Antoniou et al., 2000;

Kantas, 2001). It consists of 22 statements where the respondents identify how often

they feel professional burnout at a six-point Likert-type rating scale ranging from 0

never to 6 every day (reliability was calculated at a 0.68). The three dimensions

of professional burnout assessed by this tool are:

(1) emotional exhaustion;

(2) depersonalisation; and

(3) reduced personal accomplishment.

Results

The teachers of the present study reported moderate to high levels of stress on average,

scoring from 3 and above (3 moderate stress, 4 high levels of stress) at the six-point

scale of the questionnaire in the majority of the statements. The most highly rated

sources of stress refer to problems in interaction with students such as the large

number of pupils in the classroom, the lack of interest from the part of the pupils,

handling students with difcult character and the slow progress of certain students.

Then followed lack of resources and equipment which constitutes a factor related to the

school environment.

The factorial structure of the sources of occupational stress after performing

principal components analysis with varimax rotation with eigenvalues . 1, extracted

six factors explaining 45.7 per cent of the total variance: in-class problems and

recognition by others included items that referred to discipline problems, time and

effort devoted to a limited number of students, lack of parental recognition of teachers

work, and work/family interface, interaction with students and colleagues consisted

of items that referred to the lack of involvement in school decisions, difcult

relationships with colleagues, inadequate training and the continuous need for

decision-making in the classroom, teachers workload consisted of items that

concerned chores over and above the teachers role, lack of teaching assistants, strict

adhesion to the program, students progress included items that referred to slow

progress and limited interest by pupils, limited time for one-to-one teaching,

government support consisted of items that referred to the lack of support by the

governement, and continuous demands from teaching consisted of items that

JMP

21,7

684

referred to the stress resulting by the continuous evaluation of students, and the feeling

of being responsible for students.

Regardingthe teachers levels of burnout, three groups were formed(high moderate

and low) ineachdimension of professional burnout, according to the categorisation used

by Maslach and Jackson using the actual scores of the distribution of the present study.

Scores in the upper range of the distribution formed the high emotional

exhaustion/depersonalisation/reduced personal accomplishment group, scores in the

lower range formed the low emotional exhaustion/depersonalisation/reduced personal

accomplishment group and scores in the middle range formed the moderate group. It is

worth noting that the levels of depersonalisation of this sample are lower in comparison

with the American norms. The intercorrelations among the study variables, means,

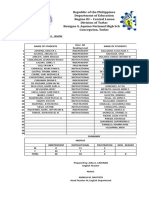

standard deviations, and Cronbach a coefcients are presented in Table I.

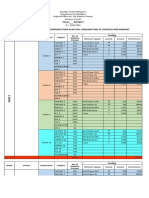

The effect of the independent variables (personal and job demographics) on the

sources of stress and the professional burnout was examined using univariate and

bivariate analysis of variance (Table II).

A signicant effect of gender was found in three stress factors namely, interaction

with students and colleagues F(1,491) 7,74, MSE 26,93, p , 0.01 (h

2

0.024),

teachers workload F(1,490) 11,94, MSE 24,40, p , 0.001, h

2

0.020,

students progress F(1,491) 16,43, MSE 16,13, p , 001, h

2

0.018. Female

teachers reported higher degree of stress compared to males on all three sources of

stress regardless of their chronological age and type of school they were teaching in

(primary or secondary). Despite the fact that the most highly rated sources of stress

differed for the two genders, these results indicated that both men and women teachers

agreed that problems in the classroom were the most serious. In terms of burnout,

emotional exhaustion differed signicantly between the two genders F(1,491) 7.53,

MSE 106,52, p , 0.01, h

2

0.015, with females reporting higher levels of

emotional exhaustion compared to their male counterparts.

Age was found to have a signicant effect on stress stemming from the lack of

government support F(3,490) 4,88, MSE 6,97, p , 0.001, h

2

0.029. Older

teachers scored higher on this source of stress, and according to the post-hoc tests,

signicant differences occurred between the three oldest age groups 31-40, 41-50 and

over 51 and the youngest group (teachers aged up to 30 years). Age had a signicant

effect on the two dimensions of burnout, i.e. emotional exhaustion F(3,490) 4,154,

MSE 105,902, p , 0.01, h

2

0.025 and depersonalisation F(3,490) 3,951,

MSE 24,024, p , 0.01, h

2

0.024. However, contrary to their stress levels,

younger teachers reported higher levels of burnout in terms of these dimensions

compared to their older colleagues (a signicant difference occurred between the

youngest up to 30 years group and the oldest over 51 group).

Discussion

The present study reveals that the main sources of stress experienced by Greek

teachers are related to discipline problems and interaction with students and

colleagues, in agreement with the documented sources of stress in the international

literature. The most frequently reported occupational stressors of the Greek teachers

refer to problems that are difcult to deal with in the classroom such as overcrowded

classrooms, students lack of motivation, poor achievement and students disciplinary

problems. It appears that these types of stressors are in accordance with a large body

Occupational

and professional

burnout

685

V

a

r

i

a

b

l

e

M

e

a

n

s

S

D

B

u

r

n

o

u

t

r

a

t

i

n

g

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

S

t

r

e

s

s

1

.

I

n

-

c

l

a

s

s

p

r

o

b

l

e

m

s

a

n

d

r

e

c

o

g

n

i

t

i

o

n

b

y

o

t

h

e

r

s

2

3

.

0

3

5

.

0

4

2

.

I

n

t

e

r

a

c

t

i

o

n

w

i

t

h

s

t

u

d

e

n

t

s

a

n

d

c

o

l

l

e

a

g

u

e

s

2

0

.

4

3

5

.

2

2

0

.

5

9

*

3

.

T

e

a

c

h

e

r

s

w

o

r

k

l

o

a

d

2

2

.

2

0

4

.

9

9

0

.

5

7

*

0

.

5

7

*

4

.

S

t

u

d

e

n

t

s

p

r

o

g

r

e

s

s

2

1

.

5

9

4

.

0

8

0

.

6

0

*

0

.

5

7

*

0

.

5

1

*

5

.

G

o

v

e

r

n

m

e

n

t

s

u

p

p

o

r

t

1

1

.

8

0

2

.

6

7

0

.

3

4

*

0

.

3

4

*

0

.

4

3

*

0

.

3

7

*

6

.

C

o

n

t

i

n

u

o

u

s

d

e

m

a

n

d

s

f

r

o

m

t

e

a

c

h

i

n

g

1

5

.

8

6

3

.

6

0

0

.

5

8

*

0

.

4

9

*

0

.

5

2

*

0

.

5

2

*

0

.

3

9

*

B

u

r

n

o

u

t

7

.

E

m

o

t

i

o

n

a

l

e

x

h

a

u

s

t

i

o

n

2

2

.

3

6

1

0

.

3

9

M

o

d

e

r

a

t

e

0

.

3

9

*

0

.

2

4

*

0

.

3

6

*

0

.

3

6

*

0

.

2

4

*

0

.

4

1

*

8

.

D

e

p

e

r

s

o

n

a

l

i

s

a

t

i

o

n

5

.

1

9

4

.

9

4

M

o

d

e

r

a

t

e

-

h

i

g

h

0

.

2

1

*

0

.

1

5

*

0

.

1

3

*

0

.

1

3

*

0

.

0

3

0

.

1

9

*

0

.

5

0

*

9

.

R

e

d

u

c

e

d

p

e

r

s

o

n

a

l

a

c

c

o

m

p

l

i

s

h

m

e

n

t

3

5

.

9

4

5

.

8

3

M

o

d

e

r

a

t

e

2

0

.

0

6

2

0

.

0

4

0

.

0

3

0

.

0

1

0

.

0

7

2

0

.

0

6

2

0

.

1

2

2

0

.

3

7

*

N

o

t

e

s

:

*

P

,

0

.

0

0

1

;

s

c

a

l

e

a

s

s

e

s

s

m

e

n

t

:

e

m

o

t

i

o

n

a

l

e

x

h

a

u

s

t

i

o

n

:

,

1

7

l

o

w

,

1

8

-

2

6

m

o

d

e

r

a

t

e

,

.

2

7

h

i

g

h

;

d

e

p

e

r

s

o

n

a

l

i

s

a

t

i

o

n

:

,

2

l

o

w

,

3

-

5

m

o

d

e

r

a

t

e

,

.

6

h

i

g

h

;

r

e

d

u

c

e

d

p

e

r

s

o

n

a

l

a

c

c

o

m

p

l

i

s

h

m

e

n

t

:

.

3

9

l

o

w

,

3

8

-

3

5

m

o

d

e

r

a

t

e

,

,

3

4

h

i

g

h

Table I.

Means, standard

deviations, and

intercorrelations among

study variables (N 493)

JMP

21,7

686

F

-

v

a

l

u

e

E

m

o

t

i

o

n

a

l

e

x

h

a

u

s

t

i

o

n

D

e

p

e

r

s

o

n

a

l

i

s

a

t

i

o

n

L

a

c

k

o

f

p

e

r

s

o

n

a

l

a

c

c

o

m

p

l

i

s

h

m

e

n

t

S

F

1

S

F

2

S

F

3

S

F

4

S

F

5

S

F

6

A

g

e

4

.

1

5

*

3

.

4

9

*

N

S

N

S

N

S

N

S

N

S

4

,

8

8

*

*

N

S

G

e

n

d

e

r

7

.

5

3

*

N

S

N

S

N

S

7

.

7

4

*

*

1

1

.

9

4

*

*

1

6

.

4

3

*

*

*

N

S

1

2

.

7

7

*

*

N

o

t

e

s

:

*

p

,

0

.

0

5

,

*

*

p

,

0

.

0

1

,

*

*

*

p

,

0

.

0

0

1

;

S

F

1

:

i

n

-

c

l

a

s

s

p

r

o

b

l

e

m

s

a

n

d

r

e

c

o

g

n

i

t

i

o

n

b

y

o

t

h

e

r

s

,

S

F

2

:

i

n

t

e

r

a

c

t

i

o

n

w

i

t

h

s

t

u

d

e

n

t

s

a

n

d

c

o

l

l

e

a

g

u

e

s

,

S

F

3

:

t

e

a

c

h

e

r

s

w

o

r

k

l

o

a

d

,

S

F

4

:

s

t

u

d

e

n

t

s

p

r

o

g

r

e

s

s

,

S

F

5

:

g

o

v

e

r

n

m

e

n

t

s

u

p

p

o

r

t

,

S

F

6

:

c

o

n

t

i

n

u

o

u

s

d

e

m

a

n

d

s

f

r

o

m

t

e

a

c

h

i

n

g

Table II.

Summary of one-way

ANOVA of the burnout

and sources of stress

scores by level of gender,

age, years of experience,

thoughts of leaving the

profession and school

type

Occupational

and professional

burnout

687

of evidence showing that in-class stressors rather than organisational stressors

constitute the major stressors affecting teachers and these can lead to feelings of low

self-efcacy and feelings that their job is meaningless (Male and May, 1998; Lewis,

1999; Forlin, 2001). It is worth pointing out that these particular sources of stress,

endogenous to the teaching profession were similarly reported in earlier studies carried

out with samples of Greek teachers working in special education (Antoniou et al., 2000).

Furthermore, the results also support the hypothesis that gender has an effect on

stress and burnout, demonstrating that female teachers experienced higher levels of

occupational stress compared to males, as regards the difculties they confront in the

classroom and the workload that often spills over to personal and family life and the

working conditions. These ndings are conrmed by the majority of international and

Greek studies exploring gender differences (Borrill et al., 1996; Georgas and

Giakoumaki, 1984; Papastylianou, 1997; Kantas, 2001) which indicate that female

teachers report higher levels of stress and higher dissatisfaction stemming from, what

they perceive, as adverse conditions in the classroom and students behaviour, as well

as work-family interface. A general tendency exists in the literature, according to

which females experience higher levels of occupational stress regarding

gender-specic stressors and have different ways of interpreting and dealing with

problems related to their work environment (Offerman and Armitage, 1993).

Moreover, females in the present study presented higher levels of emotional

exhaustion compared to their male counterparts, which probably suggests that either

they have not acquired or cannot utilise the suitable psychological-coping resources

geared to the demands of the profession. High levels of emotional exhaustion in

females have also been observed in earlier studies (Maslach and Jackson, 1986).

Nevertheless, interpreting these differences is a difcult task since there exists a

number of intervening factors, such as workload, position in the job hierarchy and

presence of social support (Greenglass, 1991; Borrill et al., 1996).

That age has an effect on the way teachers experience their job difculties, supports

the hypothesis that younger and relatively new in the profession teachers present

higher levels of stress and burnout (Byrne, 1991). As Pines and Aronson (1988) have

reported, teachers in the beginning of their career invest all their energy in order to

achieve their initial objectives, while they have to simultaneously deal with a number

of stressful and intense demands from their environment. Failing to decrease the gap

between their goals and their materialisation, this may have an adverse effect on their

job satisfaction and may lead them to decreased involvement and effort regarding their

job. This consequence can be interpreted through the young teachers difculty to

activate the appropriate coping strategies in order to reduce the occupational stress

imposed by difculties occurring in the job (Travers, n.d.). It can also be maintained

that the difculties presented at the beginning of young teachers career may be related

with their adaptation in the profession and they appear not to have long-lasting

repercussions (van Dick and Wagner, 2001).

While the cross-sectional design of the present study does not allow for causal

interpretation in any of these relationships, these ndings suggest that there might be

a connection between age and gender and the way stress is perceived by different

groups of teachers. Future studies can further investigate the specic personal, job

demographics and occupational sources of stress and burnout to specic groups of

teachers and suggest ways for prevention and intervention.

JMP

21,7

688

References

Antoniou, A.S. (1999), Personal traits and professional burnout in health professionals,

Archives of Hellenic Medicine, Vol. 16 No. 1, pp. 20-8.

Antoniou, A.S., Davidson, M.J. and Cooper, C.L. (2003), Occupational stress, job satisfaction and

health state in male and female junior hospital doctors in Greece, Journal of Managerial

Psychology, Vol. 18, pp. 592-621.

Antoniou, A.S., Polychroni, F. and Walters, B. (2000), Sources of stress and professional burnout

of teachers of special educational needs in Greece, Proceedings of the International

Conference of Special Education, ISEC 2000, Manchester, 24-28 July, UK.

Borrill, C., Wall, T. and West, M. (1996), Mental Health of the Workforce in NHS Trusts, Phase 1.

Final Report, Institute of Work Psychology, University of Shefeld and Department of

Psychology, University of Leeds, Leeds.

Brouwers, A. and Tomic, W. (2000), A longitudinal study of teacher burnout and perceived

self-efcacy in classroom management, Teaching and Teacher Education, Vol. 16,

pp. 239-53.

Byrne, B.M. (1991), Burnout: investigating the impact of background variables for elementary,

intermediate, secondary, and university educators, Teaching and Teacher Education,

Vol. 7, pp. 197-209.

Carlile, C. (1985), Reading teacher burnout: the supervisor can help, Journal of Reading, Vol. 28,

pp. 590-3.

Cooper, C. and Kelly, M. (1993), Occupational stress in head teachers: a national UK study,

British Journal of Educational Psychology, Vol. 63, pp. 130-43.

Firth-Cozens, J. and Payne, R. (1999), Stress in Health Professionals: Psychological and

Organisational Causes and Interventions, Wiley, Chichester.

Forlin, C. (2001), Inclusion: identifying potential stressors for regular class teachers,

Educational Research, Vol. 43, pp. 235-45.

Georgas, J. and Giakoumaki, E. (1984), Psychosocial stress, symptoms and anxiety of male and

female teachers in Greece, Journal of Human Stress, Vol. 10, pp. 191-7.

Greenglass, E.R. (1991), Burnout and gender: theoretical and organisational implications,

Canadian Psychology, Vol. 32, pp. 562-72.

Jaoul, G., Kovess, V. and Mgen, F.S.P. (2004), Le burnout dans la profession enseignante,

Annales Medico-Psychologiques, Revue Psychiatrique, Vol. 162, pp. 26-35.

Jennett, H.K., Harris, S.L. and Mesibov, G.B. (2003), Commitment to philosophy, teacher efcacy,

and burnout among teachers of children with autism, Journal of Autism and

Developmental Disorders, Vol. 33, pp. 583-93.

Kantas, A. (2001), Factors of stress and occupational burnout of teachers, in Vasilaki, E.,

Triliva, S. and Besevegis, kaiE. (Eds), Stress, Anxiety and Intervention, Ellinika

Grammata, Athens, pp. 217-29.

Kyriacou, C. (1987), Teacher stress and burnout: an international review, Educational Research,

Vol. 29 No. 2, pp. 146-52.

Lewis, R. (1999), Teachers coping with the stress of classroom discipline, Social Psychology of

Education, Vol. 3, pp. 155-71.

Male, D. and May, D. (1998), Stress and health, workload and burnout in learning support

coordinations in colleges of further education, Support for Learning, Vol. 13, pp. 134-8.

Maslach, C. and Jackson, S.E. (1986), Maslach Burnout Inventory (Manual), 2nd ed., Consulting

Psychologists Press, Palo Alto, CA.

Occupational

and professional

burnout

689

Offerman, L.R. and Armitage, M.A. (1993), Stress and the woman manager: sources, health

outcomes and interventions, in Fagenson, E.A. (Ed.), Women in Management: Trends,

Issues and Challenges in Managerial Diversity, Sage, Newbury Park, CA.

Papastylianou, A. (1997), Stress in secondary school teachers, in Anagnostopoulos, F.,

Kosmogianni, A. and Messini, V. (Eds), Current Psychology in Greece: Research and

Practice in Health, Education and Clinical Practice (in Greek), Ellinika Grammata, Athens.

Pines, A. and Aronson, E. (1988), Career Burnout. Causes and Cures, The Free Press, New York,

NY.

Travers, C. (n.d.), Stress in teaching: causes and consequences, in Antoniou, A-S. and

Cooper, C.L. (Eds), Research Companion to Organizational Health Psychology, Ion

Publishing Co., Athens.

Travers, C.J. and Cooper, C.L. (1993), Mental health, job satisfaction and occupational stress

among UK teachers, Work & Stress, Vol. 7, pp. 203-19.

Travers, C. and Cooper, C. (1997), Stress in teaching, in Shorrocks-Taylor, D. (Ed.), Directions in

Educational Psychology, Whurr, London.

van Dick, R. and Wagner, U. (2001), Stress and strain in teaching: a structural equation

approach, British Journal of Educational Psychology, Vol. 71, pp. 243-59.

Further reading

Burke, R.J. and Greenglass, E. (1995), A longitudinal study of psychological burnout in

teachers, Human Relations, Vol. 48, pp. 187-202.

Evans, K.B. and Fisher, G.D. (1993), The nature of burnout: a study of the three-factor model of

burnout in human service and non-human service samples, Journal of Occupational &

Organizational Psychology, Vol. 66, pp. 29-38.

Friedman, M. and Rosenman, R.H. (1974), Type A: Your Behavior and your Heart, Knopf, New

York, NY.

Corresponding author

A-S. Antoniou can be contacted at: asantoni@hol.gr

JMP

21,7

690

To purchase reprints of this article please e-mail: reprints@emeraldinsight.com

Or visit our web site for further details: www.emeraldinsight.com/reprints

Você também pode gostar

- Going AbroadDocumento1 páginaGoing AbroadDaniela Arsenova LazarovaAinda não há avaliações

- One of The Large Pieces of The Surface of The Earth That MoveseparatelyDocumento1 páginaOne of The Large Pieces of The Surface of The Earth That MoveseparatelyDaniela Arsenova LazarovaAinda não há avaliações

- Henry ViiiDocumento2 páginasHenry ViiiDaniela Arsenova LazarovaAinda não há avaliações

- Cambridge Proficiency 2013 Writing PaperDocumento4 páginasCambridge Proficiency 2013 Writing PaperpeasyeasyAinda não há avaliações

- Proficiency 2013 Listening Test Key PDFDocumento1 páginaProficiency 2013 Listening Test Key PDFana maria csalinasAinda não há avaliações

- The Three Wishes: 1001 NightsDocumento1 páginaThe Three Wishes: 1001 NightsDaniela Arsenova LazarovaAinda não há avaliações

- Dances Ballet Is A Type Of: Cante ToqueDocumento2 páginasDances Ballet Is A Type Of: Cante ToqueDaniela Arsenova LazarovaAinda não há avaliações

- Socio Cultural Factors and Its Impact On BusinessDocumento15 páginasSocio Cultural Factors and Its Impact On BusinessDivya.S.N83% (24)

- Leader-Manager Assessment Questionnaire: Self: InstructionsDocumento4 páginasLeader-Manager Assessment Questionnaire: Self: InstructionsDaniela Arsenova LazarovaAinda não há avaliações

- Erasmus+ ProgrammeDocumento315 páginasErasmus+ ProgrammezaimajAinda não há avaliações

- BJEP Paper March 2007Documento15 páginasBJEP Paper March 2007Daniela Arsenova LazarovaAinda não há avaliações

- Ruth ThesisDocumento77 páginasRuth ThesisDaniela Arsenova LazarovaAinda não há avaliações

- 1 Student CenteredDocumento33 páginas1 Student CenteredAllison FreimanAinda não há avaliações

- 2013 YT NPE Application Your NameDocumento3 páginas2013 YT NPE Application Your NameDaniela Arsenova LazarovaAinda não há avaliações

- Artikkeli 2Documento17 páginasArtikkeli 2Daniela Arsenova LazarovaAinda não há avaliações

- Psychology in The Schools, Vol. 47 (4), 2010 2010 Wiley Periodicals, Inc. DOI: 10.1002/pits.20478Documento12 páginasPsychology in The Schools, Vol. 47 (4), 2010 2010 Wiley Periodicals, Inc. DOI: 10.1002/pits.20478Daniela Arsenova LazarovaAinda não há avaliações

- 19Documento12 páginas19Daniela Arsenova LazarovaAinda não há avaliações

- 11 17Documento7 páginas11 17Daniela Arsenova LazarovaAinda não há avaliações

- 1 Student CenteredDocumento33 páginas1 Student CenteredAllison FreimanAinda não há avaliações

- BUS499 - Su07CastanedaDocumento21 páginasBUS499 - Su07CastanedaJohn ArthurAinda não há avaliações

- Are You Experiencing Teacher Burnout? A Synthesis of Research Reveals Conventional Prevention and Spiritual HealingDocumento7 páginasAre You Experiencing Teacher Burnout? A Synthesis of Research Reveals Conventional Prevention and Spiritual HealingDaniela Arsenova LazarovaAinda não há avaliações

- Burnout Syndrome in The Teaching Profession. SA Vilikazi PDFDocumento179 páginasBurnout Syndrome in The Teaching Profession. SA Vilikazi PDFDaniela Arsenova LazarovaAinda não há avaliações

- 04Documento29 páginas04Daniela Arsenova LazarovaAinda não há avaliações

- Burnout Syndrome in The Teaching Profession. SA Vilikazi PDFDocumento179 páginasBurnout Syndrome in The Teaching Profession. SA Vilikazi PDFDaniela Arsenova LazarovaAinda não há avaliações

- Teacher Burnout in Black and WhiteDocumento24 páginasTeacher Burnout in Black and WhiteDaniela Arsenova LazarovaAinda não há avaliações

- International Journals Call For Paper HTTP://WWW - Iiste.org/journalsDocumento12 páginasInternational Journals Call For Paper HTTP://WWW - Iiste.org/journalsAlexander DeckerAinda não há avaliações

- Krueger and Brazeal 1994Documento15 páginasKrueger and Brazeal 1994Daniela Arsenova Lazarova100% (1)

- Fullp 103Documento24 páginasFullp 103Viru JaniAinda não há avaliações

- Teacher Burnout, Perceived Self-Efficacy in Classroom Management, and Student Disruptive Behavior in Secondary EducationDocumento11 páginasTeacher Burnout, Perceived Self-Efficacy in Classroom Management, and Student Disruptive Behavior in Secondary EducationDaniela Arsenova LazarovaAinda não há avaliações

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5794)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (895)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (400)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (344)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (121)

- Swedish Health Care GlossaryDocumento8 páginasSwedish Health Care GlossaryVeronicaGelfgren100% (1)

- Immersion #1Documento3 páginasImmersion #1joy conteAinda não há avaliações

- Statistical TreatmentDocumento16 páginasStatistical TreatmentMaria ArleneAinda não há avaliações

- Importance of CommunityDocumento3 páginasImportance of Communitybizabt100% (1)

- Pre TestDocumento6 páginasPre TestAngie Diño AmuraoAinda não há avaliações

- Abin Azka 10DDocumento7 páginasAbin Azka 10DAziz Tanama1Ainda não há avaliações

- Education in Finland ReportDocumento17 páginasEducation in Finland ReportJoe BarksAinda não há avaliações

- Assignment 3 Case Study Critical Analysis: MandatoryDocumento7 páginasAssignment 3 Case Study Critical Analysis: MandatorykennedyAinda não há avaliações

- ALOHADocumento1 páginaALOHASangeetha NairAinda não há avaliações

- Action Plan in EnglishDocumento2 páginasAction Plan in EnglishJon Vader83% (6)

- Julia Sehmer Verdun Lesson 1Documento3 páginasJulia Sehmer Verdun Lesson 1api-312825343Ainda não há avaliações

- (Nkonko M. Kamwangamalu (Auth.) ) Language Policy ADocumento252 páginas(Nkonko M. Kamwangamalu (Auth.) ) Language Policy AUk matsAinda não há avaliações

- Newspaper 1Documento2 páginasNewspaper 1api-321772895Ainda não há avaliações

- Jose Maria Karl Arroyo Dy - SAS #12 - HIS 007Documento10 páginasJose Maria Karl Arroyo Dy - SAS #12 - HIS 007JM Karl Arroyo DYAinda não há avaliações

- A Software Maintenance Methodology For Small Organizations - Agile - MANTEMA - Pino - 2011 - Journal of Software - Evolution and Process - Wiley Online Library PDFDocumento3 páginasA Software Maintenance Methodology For Small Organizations - Agile - MANTEMA - Pino - 2011 - Journal of Software - Evolution and Process - Wiley Online Library PDFkizzi55Ainda não há avaliações

- E10tim106 PDFDocumento64 páginasE10tim106 PDFhemacrcAinda não há avaliações

- Innocent Heroes Foundation (IHF)Documento7 páginasInnocent Heroes Foundation (IHF)api-25886263Ainda não há avaliações

- Palo - District: Week School Grade Level Subject No. of Modules PrintedDocumento5 páginasPalo - District: Week School Grade Level Subject No. of Modules PrintedEiddik ErepmasAinda não há avaliações

- Dance 08 - Zumba Fitness - Choreo Task - Rubric Crit B Giang Nguyen 16fe2bvDocumento1 páginaDance 08 - Zumba Fitness - Choreo Task - Rubric Crit B Giang Nguyen 16fe2bvEunice GuillermoAinda não há avaliações

- Body and SoulDocumento11 páginasBody and SoulGraezelle GuintoAinda não há avaliações

- Teacher's and Student's CenterDocumento21 páginasTeacher's and Student's CenterNusrat Bintee KhaledAinda não há avaliações

- Sample WAP Lesson Plan With COTDocumento9 páginasSample WAP Lesson Plan With COTMarco MedurandaAinda não há avaliações

- Acr Ellen Digital Lesson 3Documento5 páginasAcr Ellen Digital Lesson 3Charles AvilaAinda não há avaliações

- Gerald Steyn - West African Influence On Various Projects by Le CorbusierDocumento17 páginasGerald Steyn - West African Influence On Various Projects by Le CorbusiersummerpavilionAinda não há avaliações

- Portable DIY Bluetooth Speaker MYP Personal Project 2015-2019Documento8 páginasPortable DIY Bluetooth Speaker MYP Personal Project 2015-2019Nrl MysrhAinda não há avaliações

- NS5e RW4 ckpt1 U02-1Documento2 páginasNS5e RW4 ckpt1 U02-1hekmatAinda não há avaliações

- Ebook Life CaochDocumento37 páginasEbook Life CaochArafath AkramAinda não há avaliações

- SLS Instructors Guidelines Manual 10-06Documento29 páginasSLS Instructors Guidelines Manual 10-06kshepard_182786911Ainda não há avaliações

- MIT Application Part 1Documento2 páginasMIT Application Part 1rothstemAinda não há avaliações