Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Chew 1995 Confucian Perspective On Conflict Resolution

Enviado por

Tesis PeruDescrição original:

Título original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Chew 1995 Confucian Perspective On Conflict Resolution

Enviado por

Tesis PeruDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

The International Journal of Human Resource Management 6:1 February 1995

A Confucian perspective on conflict

resolution

Irene K.H. Chew and Christopher Lim

Abstract

Chinese business managers, in general, have been portrayed as valuing har-

mony and peace and having a tendency to avoid confrontation for fear of dis-

turbing relationships involving mutual dependence. This is held to be a

reflection of traditional Confucian cultural values.

This paper is an exploratory study which attempts to establish the relation-

ship between the traditional, C^onfucian cultural values and the modes of con-

flict resolution preferred by Chinese business managers. The Thomas-Kilmann

Conflict Mode Instrument was employed in this study to describe the preferred

conflict resolution modes of Chinese business managers. The results show that

compromising tend to be the most preferred conflict resolution mode of

Chinese business managers because of the latter's predominantly humanistic,

Confucian self-concept.

However, other modes, that is, collaborating, competing, avoiding and

accommodating, are also being employed by Chinese business managers as a

strategic and political variation of that Confucian self-concept.

Keywords

Confucian perspective, collectivism, conflict resolution, behaviour, harmony,

business managers

Introduction

Confiict has been viewed by Cosier and Ruble (1981) as an overt

behaviour arising out of a process in which one party seeks the

advancement of its own interests in its relationship with the other. In

somewhat similar terms, Thomas (1975, 1977) has defined confiict as a

dynamic process which goes through a chain of behaviour, namely the

latest, perceived, affective/felt, manifest and aftermath stages of

0958-5192 Routledge 1995

Irene K.H. Chew and Christopher Lim

psychosomatic behaviour. As a result, perceptions of competing objec-

tives emerge in the dynamic process. A conflict situation becomes

manifest and the competing parties engage in various forms of conflict

behaviour.

Conflict can be addressed through non-attention, suppression or

attempt at resolution. Non-attention involves what it implies: there is

no direct attempt to deal with manifest conflict. The conflict is left on

its own to emerge as a constructive or destructive force. Suppression

decreases the negative consequences of a conflict, but it does not

address or eliminate root causes. It is a surface solution that allows

the antecedent conditions constituting the original reasons for conflict

to remain in place. Conflict resolution only occurs when the underly-

ing reasons for a conflict are removed and no lingering conditions or

antagonism are left to rekindle conflict in the future.

While there are obviously numerous potential determinants of con-

flict behaviour, including non-cultural factors such as personality,

organizational culture and the legal environment, our focus in this

paper is on the influence of culture.

This paper is an exploratory study which attempts to establish how

certain traditional values may affect preferred Chinese conflict-

handling and resolution styles. The term 'Chinese' has ethnic connota-

tions in this paper. It embraces the ethnic Chinese in Singapore and

abroad.

The research context

There exists a large body of work on Chinese values in the philosoph-

ical, scientiflc and psychological literature, including Needham's (1954

to date) monumental work on the science and artefacts of the ancient

civilization of China. There has been a variety of empirical studies

including those by Lin (1911), Morris (1956), Robb (1959), Tseng

(1973), Bond (1986), Frankenstein (1986), Garratt (1981), Pye (1986)

and Lockett (1987). This paper focuses on those values and orienta-

tions which seem to have signiflcance for conflict handling and resolu-

tion. These values include certain Confucian values like (1)

conformity, (2) collectivism, (3) large power distance, (4) harmony in

interpersonal relationships and (5) trustworthiness, which are strongly

emphasized in the Analects (see Lau's 1979 translation) within the

Chinese communities of the world.

Conformity is a central value in Chinese societies. It is related to

the key humanistic Confucian values of // and jen. Li refers to the

rules of propriety which structure interpersonal relationships into hier-

144

A Confucian perspective on conflict resolution

archical dualities. Individuals have to orient their behaviour to those

interpersonal relations and not change their role system in the envi-

ronment. This role system is based on the concept of wu-lun where

roles and loyalties are prioritized in terms of the five basic social rela-

tionships: the love and respect between father and son, the loyalty and

duty between sovereign and subject, the affection between husband

and wife, the seniority of the old over the young and good faith

between friends. Jen, the core Confucian concept, indicates the virtue

of attaining a benevolent relationship between man and his followers,

and it emphasizes the idea of a proactive, holistic man or human

being who is not isolated or divorced from the world (Redding, 1980).

It is this value of human being that distinguishes Chinese society as

collectivist in comparison to the individualist Western societies

(Hofstede, 1980).

The value of conformity and collective orientation make individuals

consider the relationship between themselves and other parties a cru-

cial factor in a conflict situation. Thus, it is thought that the Chinese

tend to avoid confrontation for fear of disturbing their relationships

and mutual dependence. When the dispute is with a superior, it fol-

lows, the person's natural deference to authority may lead the Chinese

individual to accommodate the superior's wishes. Also, as most

Oriental societies are characterized by larger power distance between

managers and their subordinates (Hofstede, 1980), it is natural for

one to rationalize that the relative status and authority of the parties

can become a key issue in determining conflict behaviour. Here, it is

thought that subordination is a result of power distance, hierarchical

relationship and face. Because of the respect accorded to seniors and

social etiquette, it is thought that the Chinese individual is bound to

give 'face' to seniors and deference to the wishes of seniors may result

(Hwang, 1987; Yang, 1987; Redding and Ng, 1982). In fact, one could

be exposed to shame if respect for seniors is not practised. But

Confucius (see Lau, 1979: 85 Analects VI, 30 reinterpreted) thought

otherwise, since he sees that there is always not much of a conflict

between the ambition of the superior man of jen and those who are

provided assistance by the superior man:

Now a man ofjen or benevolence, wishing to be established himself, seeks also

to establish others; wishing to turn his own merits to account, helps others to

turn theirs to account as well . . .

In other words, the hierarchical level of relationship between superior

and subordinate is accepted as natural law.

The maintenance of proper relationships is not the only emphasis

of Confucianist thought as Confucianism stresses the necessity of

145

Irene K.H. Chew and Christopher Lim

keeping relationships in harmony and peace. Often, Chinese individu-

als are asked to adapt themselves to collective society, control their

own emotions and avoid dissension, competition and conflict. The

Confucian terminology for peace, namely ho-ping, is a compound of

two ideographs - harmony and equilibrium. As a result, Mencius (see

Lau, 1970: 53, Mencius, Book 1, Part A:6 interpreted) recommends

the use of empathy rather than physical force in order to bring unity

among the conflicting parties: 'Only he who abhors the taking of a

man's life may bring about unification, harmony and progress.'

The willingness to develop a trust, hsin-yi, for others depends on

such values as good faith and reciprocation. Confucius (see Lau,

1979, Analects XII, 10) does not know how a man or human being

without good faith can get on in life. In terms of a whole society,

Confucius (see Lau, 1979, Analects XII, 77) found that it is the trust

the people have in their government rather than the provision of food

to the people that formed the basis of good government. The govern-

ment which strives to be people or yew-centred, according to Mencius'

(see Lau, 1970, Mencius, Book VII: B14) contention, is not one that

betrays the confidence the people have in the government. Otherwise,

the people have the right to confront and overthrow a government

which breaks the contract of good faith when it ceases to promote

welfare and good relationship among people.

Method

In order to explore the influence of possible Confucian values and dif-

ferentiation in conflict-handling styles among the Chinese, a sample

group was used in this study. This sample comprises thirty-three

CEOs (Chief Executive Officers) in private business organizations

which cover a wide variety of industries: manufacturing, services,

trading, construction, etc. These subjects are of the Chinese ethnic

group and they reside in China, Taiwan, Indonesia and Singapore.

They all completed their primary and secondary school education in

Mandarin. All subjects were participants in a management training

course conducted by an institution of higher learning in Singapore.

Procedures

A questionnaire consisting of the Thomas-Kilmann Conflict Mode

Instrument and a Confucian Value Questionnaire in Mandarin to be

described later were administered to respondents who participated in

146

A Confucian perspective on conflict resolution

the management course that was conducted for three sessions. The

management course had a total enrolment of 100 participants, that is,

thirty participants in two sessions and forty participants in the last

session. Out of the 100 participants, only thirty-three CEOs

responded. Several styles of conflict management were derived from

the Thomas-Kilmann instrument and, from these styles, various inter-

correlations via Pearson's r were made with the subscale scores of the

Confucian Value Questionnaire. Cronbach's alpha was used to esti-

mate the reliability of the Thomas-Kilmann Conflict Mode Instrument

and the Kuder-Richardson Formula 21 was used for the Confucian

Value Questionnaire. The two instruments yielded a respective relia-

bility of 0.81 and 0.72.

Instruments and measures

For the first part of this study, the Thomas-Kilmann Conflict Mode

Instrument was employed. This instrument classifies conflict behav-

iours into five basic styles: namely competing, collaborating, compro-

mising, avoiding and accommodating, depending on different degrees

of assertiveness and co-operation (Thomas, 1975).

The competing style is assertive and uncooperative, a power-

orientated mode used by managers who defend their positions at the

expense of other persons. The collaborating style is both assertive and

co-operative, a team-orientated mode used by managers to solve prob-

lems. The compromising style is one where managers exchange conces-

sions and therefore it is middle-of-the road or intermediate in

assertiveness or co-operativeness. The avoiding style is both unassertive

and uncooperative, a power-vacuum mode used by managers to side-

step an issue or withdraw from a threatening situation. The accommo-

dating style is unassertive but co-operative, a sacriflcial mode where

the managers suppress their own concerns to satisfy the concerns of

others.

There are thirty questions in the Thomas-Kilmann Conflict Mode

Instrument. For each question, respondents are asked to select one

situation out of two that best describes their preferred behaviour;

these are either-or situations such as:

A. I am usually firm in pursuing my goals. (Competing Style)

B. I attempt to get all concerns and issues immediately out in the open.

(Collaborating Style)

A. I attempt to immediately work through our differences. (Collaborating

Style)

B. I try to find a fair combination of gains and losses for both of us.

(Compromising Style)

147

Irene K.H. Chew and Christopher Lim

A. I sometimes avoid taking positions that would create controversy.

(Avoiding Style)

B. If it makes the other person happy, I might let him maintain his views.

(Accommodating Style)

The second part of the survey used the Confucian Value

Questionnaire. Here certain Confucian cultural values and their

importance were ranked in terms of (a) the Chinese business man-

agers' own self-concept of Chinese values and (b) their perception of

values of other Chinese business managers. As indicated earlier, these

values include those core Confucian values of conformity, collec-

tivism, power distance and status, harmony and trustworthiness. The

first subscale, the business managers' self-concept of values, relates to

their own prioritization of the usefulness of the aforesaid values in

business dealings. In other words, this subscale focuses on the per-

sonal preferences and inner personality of the managers. The second

subscale, the business managers' perception of values of other busi-

ness managers, however, constitutes what the business managers per-

ceive are the shared values of the Chinese business community and

environment. This subscale therefore describes the managers' dynamic

assessment of the external, global Chinese values that are demanded

by their business colleagues and rivals in business dealings.

In an additional subscale of the Confucian Value Questionnaire,

potential areas of disagreement in business were solicited in terms of

benefits and profit sharing, company policies, differences in work atti-

tudes, partners' attempts to alter terms of contract, interpretation of

terms of contracts and unreliable delivery dates. The scores on this

subscale include ratings on the frequency and seriousness of these

areas of disagreement.

Analysis and results

As shown below, the responses to the questions raised under the

Thomas-Kilmann Conflict Mode Instrument show that the compro-

mising mode was most often used to handle conflicts:

Preferred conflict- Percentage of

handling mode respondents

Competing 18.00

Collaborating 22.20

Compromising 24.30

Avoiding 19.30

Accommodating 16.20

148

A Confucian perspective on conflict resolution

The collaborating mode seems to be preferred as well (this mode was

2 per cent below the compromising mode). The avoiding mode was

next on the list. Although the competing and accommodating models

were not strongly favoured, their percentage share of the responses

tend to be quite significant. The rank order of the conflict resolution

modes of the Chinese business manager, however, is not surprising.

The aim of Confucian traditional education has always been one that

is characterized by a love for moderation and restraint. That is the

doctrine of chung-yung which reminds us of the in medio stat virtus or

'nothing too much' ideal of the Greeks. The dominant compromising

mode of the Chinese business manager, as such, can be associated

with that kind of moderate chung-yung learning which specifies that

'to go beyond is as wrong as to fall short' (see Lau,. 1979: 108,

Analects XI, 16). But the Chinese approach to conflict management

may venture even further than the reaches of chung-yung compromise.

As the results show, other modes of conflict management were used

by the Chinese business managers as well. Using Confucian logic as it

is propounded by the I-Ching (see Wilhelm's 1967 translation), all

these modes seem to represent eclectic, ying-yang variations on the

compromise approach (i.e. the soft-hard approach). Here the soft yin

approaches of avoidance and accommodation and the hard yang

approaches of collaboration and competition exist in a conflict man-

agement continuum where there are no absolutes, only states of flux

of conflict modes that are relative to the diverse personality, values

and rationality of the Chinese business managers.

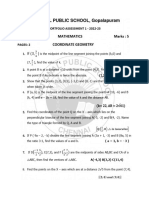

Table 1 shows the intercorrelations of the respondents' own value

and their conflict-handling mode preferences. As can be seen in Table

1, respondents who attached importance to collectivism were more

likely to use the compromising mode of handling conflicts.

Collectivism, rather than harmony as a personal value, has tended

to become the hallmark of this proactive compromise approach of the

Chinese business managers. Collectivism is the dominant Chinese

business managers' answer to the difficulties of practising the univer-

sal golden rule of love, which, as stated in the Analects XII, 2 (see

Fung, 1948: 43), runs as follows:

Do not do to others what you do not wish yourself. Do to others what you

wish others to do to yourself.

A significant collectivism -> compromise correlation (r = 0.58, p <

0.01), and not a significant conformity -^ collaboration or conformity

> avoidance correlation, has emerged to solve such moral dilemmas

in business. This connection between collectivism and compromise

indicates that there is a kind of affinity in the Chinese for teamwork

149

Irene K.H. Chew and Christopher Lim

I

I

5

I

I

I

I

o

J

I

2

8

I

I

1

I

II

o

VO oo

-H O

<N

r

. CO

ao

c

o

U

ao

a

a

t

i

o

.2

"o

U

00

c

I

c

a

a

ao

_c

3

'o

>

<

00

t

i

n

ca

i

J

p

V

*

o

V

a

*

150

A Confucian perspective on conflict resolution

and brotherhood, and this, as it is embodied in the Book of Rites

(Legge, 1900/1965: 364-5), points to a Utopian vision of Great

Brotherhood (Ta-Tung) where:

The worthy, sincere and able were promoted to office and the people practiced

good faith and lived in good neighbourliness. These people worked hard to

earn a living. They hated to see goods lying in waste, yet they did not hoard

them for themselves; they disliked the thought that their energies were not

fully used, yet they used them not for private gains.

Compare the conflict mode correlations of those respondents who val-

ued harmony. In the case of those respondents who valued harmony,

both compromise and competition were likely to be used to resolve

conflict. This implies that, even in competition, as it is embodied in

Sun Tzu's Art of War (see Giles, 1910: 17 translation), harmony or

diplomatic tactics may be desired in ultimate terms, for 'supreme excel-

lence consists in breaking the enemy's resistance without fighting'.

Table 2 shows the intercorrelations of the respondents' perception

of values held by Chinese business managers and the respondents'

conflict-handling mode preferences. The assumptions of Table 2 are

different from that of Table 1 where the emerging conflict modes

reflect the business managers' self-concept of traditional values. In

Table 2, the intercorrelations, ceteris paribus, tend to be seen as repre-

sentations of conflict modes that are modified by the Chinese business

managers' perception of others. As can be seen in Table 2, the avoid-

ing mode (r = 0.74, p< 0.01) was predominantly used by respondents

who perceived collectivism to be valued by Chinese business man-

agers. The collectivism -> avoiding stance recalls the logic of wu-wei

(non-action or non-interference) in Taoist philosophy. The term wu-

wei does not mean no-action that is contrary to the tao or goal-path

in which people reach their destination or objectives. In this case,

those business managers who used the avoidance mode were not tak-

ing a competitive stance to disrupt the status quo of other business

managers, whom they perceived to have a keen preference for a ta-

tung collectivism and teamwork. In the other case of respondents who

thought that Chinese business managers valued trustworthiness, it

may seem implausible that the competing mode (r = 0.56, p < 0.05)

was used to resolve conflict. Apparently, it was the dark, hijacked side

of Confucianism that tended to be portrayed in this case. Here a

number of Chinese business managers seemed to have applied the

competing mode to exploit or betray whatever trust or good faith

they think others have on them. They were probably the competing

xiao-jen (petty Machiavellian men and women), who, living in their

own world that was devoid of compromise, believed in the law of the

jungle and the survival of the fittest.

151

Irene K.H. Chew and Christopher Lim

J

I

I

I

S

-Ci

-5

2

I

I ^

8 s

S i ^

^

at st

I

I

=5

I

I

vo >o o^ u^ so

>/^ fS ro <N O

Tt OO ' u-1

f^ ^t C^ C^ f*^

oo o < t^

ro Tt Tt (N

s

o ^t f^

o t^ o

O -^ Ov <N

m r-4 o <N

&0

bO C

OO c

60 -3

S 2

c = E o

o o o >

U U U <

^B

o

V

a

o

V

152

A Confucian perspective on conflict resolution

Intercorrelations of the possible areas of disagreement and the

respondents' conflict-handling mode preferences are indicated in Table

3. Respondents who preferred the accommodating rather than the

compromise or collaboration modes of conflict, as expected, experi-

enced the least disagreements and these relate to policies (r = 0.46, p

< 0.05) and differences in work attitudes (r = - 0.45, p < 0.05). As for

respondents who preferred the avoiding modes, they seldom experi-

enced differences resulting from differences from unreliable dates

(r = - 0.43, p < 0.05) since they tended to be less affected by such

unreliability.

Although the sample size was not large and exploratory in this

study, the authors are of the opinion that the aforesaid signiflcant

results indicate that there are important culturological findings to be

made about the conflict management modes of Chinese business man-

agers. It is not, however, the intention of this paper to study all the

relationships and ramifications of Confucian culture and conflict man-

agement. Rather, the authors are able to summarize from this research

the basic influence of Confucian values on conflict management.

Discussion and summary

It is the Confucian concept of collectivism, that is of self as a centre

of ever-widening relations embodying family, society, nation and

being-with-others in the universe, that has created a social pressure

for Chinese business to be less openly aggressive and emotional in

conflict situations. Such a concept of collectivism, as shown in this

study, naturally leads to the possession of high compromising and

avoiding styles and relatively lower preference for competing behav-

iour.

The influence and operation of conformity, power distance, har-

mony and trustworthiness are most complicated. The correlations

between the various conflict modes and the Confucian values of con-

formity and power distance tend to be non-significant and inexplica-

ble. They are inexplicable, perhaps, in the sense that the conflict

modes of the Chinese business managers do not quite corroborate the

conformity -> accommodating and power distance -^ competing para-

digms of the democratic system. A reasonable explanation for such

non-significant correlations, however, lies in the fact that conformity

and power distance are taken for granted by Chinese business as nat-

ural laws of socialization whereas, in the democratic Aristotelian sense

(see Sinclair, 1981: 181, Aristotle: The Politics, III iv, 1277 a33-b7),

these same values may be critical, bargainable rule-of-law concerns:

153

Irene K.H. Chew and Christopher Lim

1

!

I

I

I

I

I

a

..?i

I

I

I

I

5

I

I

a

I

I

I

in o

O O (N

t3 8

2 a

I '^

O a

u O

154

A Confucian perspective on conflict resolution

For there is such a thing as rule by a master, which we say is concerned with

necessary tasks: but the master has no necessity to know more than how to use

such labour. Anything else, I mean to be able actually to be a servant and to

do the chores, is simply slave-like. . . . But there is another kind of rule - that

exercised over men who are free, and similar in birth. This we call rule by a

statesman.

Though ironical, the humanistic values of harmony and trustworthi-

ness can, among other things, be associated with the competing mode

of Chinese business managers. Here, the latter mode can be practised

as a utilitarian form of legalism to ensure peace and harmony among

the conflicting parties or, alternatively, as a malevolent form of utili-

tarianism to exploit the trust and good faith of other business man-

agers.

The Chinese business managers' form of conflict management can

be likened to the changing colours of the chameleon. According to the

findings of this research, several forms were utilized on different occa-

sions but these styles also reflected an explanation of thinking that is

characteristically Confucian. The following are some possible

Confucian logic or managerial justifications that support the conflict

responses of Chinese business managers:

7. Reframing as a locus of thinking The compromise approach

tends to be the dominant Chinese business managers' tactic to reframe

or neutralize any unfavourable outcome that may arise from a conflict

situation. Apparently, the internal locus of thinking of the Chinese

manager is that: To get something, one must give first. This is a well-

known compromise tactic that may be employed by many Chinese

business managers when they negotiate to market their goods and ser-

vices. That tactics are a product of reciprocal determination whenever

two or more parties are involved in a conflict situation.

2. Postponement motives as external locus In order to respond to

another party or business competitor in a conflict situation, the

Chinese manager should be able to extricate himself from difficulties

by avoiding a confrontation with his opponent. The Chinese manager

should be able to modify and postpone his or her plans to suit chang-

ing circumstances in order to achieve the best results. The external

locus of thinking of the Chinese business manager is opportunist and

recalls the Art of War as it is propounded by Sun Tzu (see Giles,

1910): Know your opponent and know yourself. If you are unsure about

nature and the situation, do not force a triumph. Those who can wait,

and can follow the opponent's transformations and then triumph when

the iron is hot, can be called genius.

3. Receptivity as an exonerative action In order to absolve himself

or herself from being labelled as uncooperative in a conflict situation,

155

Irene K.H. Chew and Christopher Lim

the Chinese business manager must be able to empathize with the

view of his or her business opponents. The logic of the Chinese man-

ager tends to be as follows: Whenever one yields, resistance becomes

less. If one becomes more sympathetic and accommodates the needs of

our opponents, they become more forthcoming. This prevents the escala-

tion of conflict. If however one does not know how to exercise authority

or is overly solicitous to the needs of the opponent, the conflict will end

up as a lose-win situation. The idea is to be receptive and at the same

time exercise restraint in one's accommodation.

As it is used in this paper, the Thomas-Kilmann Conflict Mode

Instrument has been a useful construct in deciphering Chinese conflict

management style. Yet, as a self-report instrument it can measure

only reported preferences and not actual conflict behaviour. It follows

that more qualitative research and content interviews have to be con-

ducted to map out the actual conflict behaviour of Chinese business

managers if more cross-cultural learning in conflict behaviour is to be

unravelled.

Irene K.H. Chew

School of Accountancy and Business

Nanyang Technological University

Christopher Lim

Nanyang Polytechnic

School of Business Management

Singapore

References

Bond, M.H. (ed.) (1986) The Psychology of the Chinese People. Hong Kong:

Oxford University Press.

Cosier, R.A. and Ruble, T.L. (1981) 'Research on Conflict-Handling Behaviour:

An Experimental Approach', Academy of Management Journal, 24: 816-32.

Frankenstein, J. (1986) 'Trends in Chinese Business Practice: Changes in the

Beijing Wind', California Management Review, 29(1): 148-60.

Fung, Y.L. (1948) A Short History of Chinese Philosophy. New York: Macmillan.

Garratt, ? (1981) 'Contrasts in Chinese and Western Management Thinking'

LODJ, 2(1).

Giles, L. (1910) Sun Tzu on the Art of War. Singapore: Graham Brash.

Hofstede, G. (1980) 'Motivation, Leadership, and Organization: Do American

Theories Apply Abroad?', Organizational Dynamics, Summer.

Hwang, K.K. (1987) 'Face and Favour: The Chinese Power Game' , American

Journal of Sociology, 92(4): 944-74.

Lau, D.C. (trans.) (1970) Mencius. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

156

A Confucian perspective on conflict resolution

Lau, D.C. (trans.) (1979) The Anatects. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

Legge, J. (trans.)/Muller, F.M. (ed.) (1900/1965) The Sacred Books of the East, W.

27, Pt III. Delhi: Montilal Banarsidass.

Lin, Y.T. (1911) My Country and My Peopte. Hong Kong: Heinemann.

Lockett, M. (1987) 'China's Special Economic Fares: The Cultural and

Managerial Challenges', Journat of Generat Management, 12(3): 21-31.

Morris, C.W. (1956) Varieties of Human Vatues. Chicago: University of Chicago

Press.

Needham, J. (1954-date) Science and Civitization in China. Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press.

Pye, L. (1986) Chinese Commercial Negotiating Styles. New York: Oelgeschlager,

Gunn & Hain.

Redding, S.G. (1980) 'Cognition as an Aspect of Culture and its Relation to

Management Processes: An Exploratory View of the Chinese Case', Journal of

Management Studies, 17: 127-48.

Redding, S.G. and Casey, T. (1976) 'Managerial Beliefs among Asian Managers',

Academy of Management Proceedings, 351-5.

Redding, S.G. and Ng, M. (1982) 'The Role of "Face" in the Organisational

Perceptions of Chinese Managers', Organisational Studies, 3(3): 201-19.

Robb, W.G. (1959) 'Cross-cultural Use of the Study of Values', Psychologia, 2:

157-64.

Sinclair, T.A. (trans.)/Saunders, T.J. (rev.) (1981) Aristotle: The Politics.

Harmondsworth: Penguin.

Thomas, K. (1975) 'Conflict and Conflict Management'. In Dunnette, M. (ed.)

Handbook of Industrial and Organisational Psychology. Chicago: Rand

McNally.

Thomas, K.W. (1977) 'Towards Multidimensional Values in Teaching: The

Example of Conflict Management', Academy of Management Review, 2.

Tseng, W.S. (1973) 'The Concept of Personality in Confucian Thought',

Psychiatry, 36: 191-202.

Wilhem, R. (trans.)/Baynes, C.F. (trans, into English) (1967) The I-Ching or Book

of Changes. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Yang, K.S. (1986) 'Chinese Personality and Its Change'. In Bond, M.H. (ed.) The

Psychology of the Chinese People. Hong Kong: Oxford University Press.

Yang, L.S. (1957) 'The Concept of Pao as a Basis for Social Relations in China'

In Fairbank, J.K. (ed.) Chinese Thought and Institutions. Chicago: University of

Chicago Press, pp. 291-9.

157

Você também pode gostar

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (265)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (119)

- AQA-7131-7132-SP-2023Documento42 páginasAQA-7131-7132-SP-2023tramy.nguyenAinda não há avaliações

- Palpation and Assessment SkillsDocumento305 páginasPalpation and Assessment SkillsElin Taopan97% (34)

- Dapat na Pagtuturo sa Buhangin Central Elementary SchoolDocumento14 páginasDapat na Pagtuturo sa Buhangin Central Elementary SchoolKATHLEEN CRYSTYL LONGAKITAinda não há avaliações

- G10 - Portfolio Assessment 1 - 2022-2023Documento2 páginasG10 - Portfolio Assessment 1 - 2022-2023ayush rajeshAinda não há avaliações

- 2nd Sem Result MbaDocumento2 páginas2nd Sem Result MbaPrem KumarnAinda não há avaliações

- Lesson Plan 7e's Sea BreezeDocumento3 páginasLesson Plan 7e's Sea BreezeMark Joel Macaya GenoviaAinda não há avaliações

- Exercises - Nominal and Relative ClausesDocumento23 páginasExercises - Nominal and Relative ClausesRoxana ȘtefanAinda não há avaliações

- PMP Training 7 2010Documento5 páginasPMP Training 7 2010srsakerAinda não há avaliações

- Group CohesivenessDocumento26 páginasGroup CohesivenessRaviWadhawanAinda não há avaliações

- The Effect of Peer Pressure To The Grade 10 Students of Colegio San Agustin Makati 2018-2019 That Will Be Choosing Their Respective Strands in The Year 2019-2020Documento5 páginasThe Effect of Peer Pressure To The Grade 10 Students of Colegio San Agustin Makati 2018-2019 That Will Be Choosing Their Respective Strands in The Year 2019-2020Lauren SilvinoAinda não há avaliações

- Punjabi MCQ Test (Multi Choice Qus.)Documento11 páginasPunjabi MCQ Test (Multi Choice Qus.)Mandy Singh80% (5)

- My Daily Journal ReflectionDocumento4 páginasMy Daily Journal Reflectionapi-315648941Ainda não há avaliações

- Chem237LabManual Fall2012 RDocumento94 páginasChem237LabManual Fall2012 RKyle Tosh0% (1)

- Unit 4 Assignment 4.2Documento8 páginasUnit 4 Assignment 4.2arjuns AltAinda não há avaliações

- Collaboration and Feeling of Flow With An Online Interactive H5P Video Experiment On Viscosity.Documento11 páginasCollaboration and Feeling of Flow With An Online Interactive H5P Video Experiment On Viscosity.Victoria Brendha Pereira FelixAinda não há avaliações

- Lucena Sec032017 Filipino PDFDocumento19 páginasLucena Sec032017 Filipino PDFPhilBoardResultsAinda não há avaliações

- Thesis Ideas (List of Titles)Documento13 páginasThesis Ideas (List of Titles)kimberl0o0% (2)

- SteelDocumento23 páginasSteelMelinda GordonAinda não há avaliações

- LP - CELTA TP7 READING - FaziDocumento6 páginasLP - CELTA TP7 READING - FaziPin juAinda não há avaliações

- Shaurya Brochure PDFDocumento12 páginasShaurya Brochure PDFAbhinav ShresthAinda não há avaliações

- Hang Out 5 - Unit Test 8Documento2 páginasHang Out 5 - Unit Test 8Neila MolinaAinda não há avaliações

- Cspu 620 Fieldwork Hours Log - Summary SheetDocumento2 páginasCspu 620 Fieldwork Hours Log - Summary Sheetapi-553045669Ainda não há avaliações

- Dijelovi Kuće-Radni ListićDocumento10 páginasDijelovi Kuće-Radni ListićGise Cerutti Pavić100% (1)

- Grade 7 - 10 Class Program Sy 2022 2023Documento4 páginasGrade 7 - 10 Class Program Sy 2022 2023Niel Marc TomasAinda não há avaliações

- Early Warning System RevisitedDocumento4 páginasEarly Warning System RevisitedViatorTheonAinda não há avaliações

- Architecture Literature Review SampleDocumento7 páginasArchitecture Literature Review Samplec5pnw26s100% (1)

- Resume PDFDocumento1 páginaResume PDFapi-581554187Ainda não há avaliações

- Weekly Report, Literature Meeting 2Documento2 páginasWeekly Report, Literature Meeting 2Suzy NadiaAinda não há avaliações

- Landscape Architect Nur Hepsanti Hasanah ResumeDocumento2 páginasLandscape Architect Nur Hepsanti Hasanah ResumeMuhammad Mizan AbhiyasaAinda não há avaliações

- Erasmus Module CatalogueDocumento9 páginasErasmus Module Catalogueelblaco87Ainda não há avaliações