Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Hcal000906 2000

Enviado por

pschilDescrição original:

Título original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Hcal000906 2000

Enviado por

pschilDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

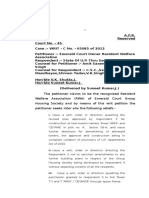

HCAL274, 376-382, 390-394, 396,

900-904, 906, 907, and 909915/2000

IN THE HIGH COURT OF THE

HONG KONG SPECIAL ADMINISTRATIVE REGION

COURT OF FIRST INSTANCE

CONSTITUTIONAL AND ADMINISTRATIVE LAW LIST

NOS. 274 of 2000, 376 of 2000, 377 of 2000, 378 of 2000,

379 of 2000, 380 of 2000, 381 of 2000, 382 of 2000, 390 of 2000,

391 of 2000, 392 of 2000, 393 of 2000, 394 of 2000 & 396 of 2000

----------------------

BETWEEN

LEUNG MAN CHEUNG

LEUNG KAM CHEUNG and OTHERS

Applicants

and

SECRETARY FOR PLANNING AND LANDS

LAND DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION

Respondent

Intervener

-----------------------

AND

CONSTITUTIONAL AND ADMINISTRATIVE LAW LIST

NOS. 900 of 2000, 901 of 2000, 902 of 2000, 903 of 2000,

904 of 2000, 906 of 2000, 907 of 2000, 909 of 2000, 910 of 2000,

911 of 2000, 912 of 2000, 913 of 2000, 914 of 2000 & 915 of 2000

----------------------

BETWEEN

LI TING CHUNG and OTHERS

Applicants

and

CHIEF EXECUTIVE IN COUNCIL

LAND DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION

Respondent

Intervener

- 2 -

-----------------------

(Consolidated pursuant to the Order of the

Honourable Mr Justice Cheung dated 23 June 2000)

Before : Hon Cheung J in Court

Dates of Hearing : 29 - 31 August, 1, 4 and 5 September 2000

Date of Judgment : 14 September 2000

---------------------JUDGMENT

---------------------APPLICATIONS FOR JUDICIAL REVIEW

These are the applications for judicial review by the owners of

15 properties (the properties) in Kennedy Town against first, the decision

of the Secretary for Planning and Lands (the Secretary) dated 10 March

2000 recommending to the Chief Executive in Council for the resumption

of their properties under the Lands Resumption Ordinance (LR

Ordinance), and, second against the decision of the Chief Executive in

Council on 2 May 2000 resuming the properties. The Land Development

Corporation (the Corporation) intervened as an interested party.

THE PROPERTIES

The particulars of the ownership and properties are set out

below :

HCAL NO. APPLICANT

PROPERTY

(1)

274/2000,

902/2000

Leung Man Cheung &

Leung Kam Cheung

4 Kin Man Street (whole

building)

(2)

376/2000,

904/2000

Wholly Earn Investment

Limited

G/F, 10A Davis Street

- 3 -

(3)

377/2000,

901/2000

Leung Pou Lan alias

Bolan Lu-Sheng

G/F, 105 Catchick Street

(4)

378/2000,

906/2000

Chiu Chut Fong

G/F & M/F, 107 Catchick

Street

(5)

379/2000,

909/2000

Lai An Chun

G/F, 1 Cadogan Street

(6)

380/2000,

903/2000

(7)

381/2000,

912/2000

Leong (or Leung)

G/F & Cockloft, 27

Man Po alias Leung Man Cadogan Street

Por

Toppy Year

G/F, 117 Catchick Street

Development Limited

(8)

382/2000,

913/2000

Toppy Year

Development Limited

G/F including cockloft

therein of 115 Catchick

Street

(9)

390/2000,

911/2000

Au Siu Ping, Au Yat On

David, Tang Mei Wan

G/F, 15 Cadogan Street &

G/F, 17 Cadogan Street

(10)

391/2000,

910/2000

Yiu Wai Sang

G/F, 2H Davis Street

(11)

392/2000,

900/2000

Li Ting Chung

G/F, 2A Davis Street

(12)

393/2000,

907/2000

Chan U Tong

G/F, 2C Davis Street

(13)

394/2000,

914/2000

Toppy Year

Development Ltd

G/F, 43 New Praya

Kennedy Town

(14)

396/2000,

915/2000

Toppy Year

Development Ltd

G/F, 42 New Praya

Kennedy Town

THE DEVELOPMENT PROPOSAL

- 4 -

The properties are situated in an area which is designated as a

Comprehensive Development Area (CDA) on the draft Kennedy Town

and Mount Davis Outline Zoning Plan No.S/HI/8. Initially, the Housing

Society was to implement the redevelopment scheme of these properties.

However, it was unable to do so and the Corporation was appointed by the

Government in March 1997 to proceed with the redevelopment. In

April 1997, the Secretary designated the CDA as an area which the

Corporation may purchase or otherwise acquire or hold land under

section 5(2)(a)(i) of the Lands Development Corporation Ordinance (the

LDC Ordinance).

The Corporation implements urban renewal projects either by

way of a development scheme under section 13 of the LDC Ordinance or

by a development proposal under section 5(2)(b) of the LDC Ordinance.

In a development proposal, no rezoning is required and no approval by the

Town Planning Board (the Board) under section 14 of the LDC

Ordinance is required. In this case, the project was being carried out as a

development proposal since the project area had already been zoned a

CDA, the Boards approval of a Master Layout Plan (MLP) was

required. The MLP was approved. The development proposal is

undertaken by the Corporation with a partner.

The project covers an area of about 6,072 square metres and is

located by the seafront of Kennedy Town. The area comprises run-down

and dilapidated buildings (built in the 1950s) containing substandard

domestic accommodation including caged apartments and ground floor

shops. The project is known as the H12 Project. In three months from the

start of this project, the Corporation made its first offer to all owners on

- 5 -

9 July 1997. By June 1998, the Corporation had successfully acquired by

agreement 247 out of 310 (or 80% of the premises affected by the project).

The rest was the subject of an application by the Corporation to the

Secretary for recommendation of resumption. The recommendation was

made on 15 March 2000. The Chief Executive in Council ordered

resumption on 2 May 2000.

STATUTORY FRAMEWORK

The operation of the statutory framework of the LDC

Ordinance, the Town Planning Ordinance and the LR Ordinance had been

considered by me in the recent decision of Kaisilk Development Ltd v.

Secretary for Planning Environment and Lands (HCAL148/1999). It is not

necessary for me to repeat them here. The only matter to note is that in

respect of a development proposal there is no requirement that an

application for recommendation to resume has to be made not later than

12 months after the approval by the Chief Executive in Council under

section 9 of the Town Planning Ordinance of a draft plan.

Recommendation for resumption

In respect of the development proposal, section 15(4) of the

LDC Ordinance provides that :

(4) The Secretary shall not make a recommendation in

pursuance of subsection (2)(b) (i.e. the Corporation has been

unable to acquire any land which it requires to implement a

development proposal authorized under section 5(2)(b) of this

Ordinance),

(a) unless the development proposal may lawfully be

implemented by virtue of the provisions of any draft

or approved plan for the purposes of the Town

Planning Ordinance (Cap.131) and, in the case where

- 6 -

by virtue of such plan, permission under section 16 of

that Ordinance is required for that implementation,

the permission required has been obtained;

(b) unless the application for resumption is accompanied

by a statement

(i) setting out how the Corporation intends that the

proposal will be implemented, including whether

implementation will be by the Corporation alone

or the Corporation in association with another

person and in relation to land within the

boundaries of the proposal, what portion of the

land is owned or leased by the Corporation and

what arrangements have been made or are

contemplated by the Corporation for the

acquisition of any land not so owned or leased;

(ii) containing an assessment by the Corporation as

to the likely effect of the implementation of the

proposal, including, in relation to the residential

accommodation of persons who will be displaced

by the implementation of the proposal, an

assessment as to whether or not, insofar as

suitable accommodation for such persons does

not already exist, arrangements can be made for

the provision of such residential accommodation

in advance of any such displacement which will

result as the proposal is implemented; and

(c) unless he is satisfied that the Corporation has been

taken all reasonable steps to otherwise acquire the

land including negotiating for the purchase

thereof on terms that are fair and reasonable.

(emphasis added)

(5)

For the purpose of this section, in considering whether or

not the Corporation has negotiated for the purchase of the land

on terms that are fair and reasonable, the Secretary may consult

any person not being a public officer whom he considers may be

able to assist him in forming an opinion on which to base his

decision in respect of that negotiation.

THE ISSUES

In these applications, the Applicants have, first of all,

identified the issues that are common to all the applications and then dealt

- 7 -

with issues that are unique to the individual Applicants. I will follow this

structure in my judgment.

CHALLENGE TO THE DECISION OF THE SECRETARY

The common issues

The Applicants complained that the decisions should be

quashed by reason of the following common issues :

(1)

The Corporations offers were too low.

(2)

The Corporation failed to disclose comparables of valuation.

(3)

The Corporation failed to really negotiate with the Applicants.

(4)

The Secretary had, in breach of section 15(5) of the LDC

Ordinance, consulted public officers in considering whether or

not the Corporation had negotiated for the purchase of land on

terms that are fair and reasonable.

(5)

The decisions are Wednesbury irrationally.

(6)

There are procedural impropriety involved in the

decision-making process in that the Secretary had failed to

give reasons for his decision.

(7)

The Lands Tribunal did not provide the Applicants with

adequate relief.

(8)

Is the High Court in judicial review an appropriate forum to

deal with valuation issues?

(9)

Courts discretion.

Issues unique to individual applications

- 8 -

The following are issues unique to individual applications :

(1)

Redevelopment potential not taking into account (this relates

only to HCAL No.274 of 2000).

(2)

An area of land over which there are private rights of passage

in favour of an adjoining occupier can be taken into account

for the purpose of determining the area of the site (this relates

to HCAL No.274 of 2000 only).

(3)

The Corporation failed to give Home Purchase Allowance

(HPA) (this relates to HCAL No.274 of 2000 only).

(4)

Unauthorised structures ought to be taken into account for

valuation (this relates to HCAL Nos.376, 377, 378, 379, 380,

381 and 392 of 2000).

(5)

The area of the cockloft (this relates to HCAL No.377 of

2000).

(6)

Inadequate response to counteroffers (this relates to HCAL

Nos.379, 380, 381, 382, 390, 392, 394 and 396 of 2000).

(7)

The Corporation failed to conduct measurements on site (this

relates to HCAL Nos.377, 378, 380, 381 and 382 of 2000).

(8)

The Corporation failed to deal timeously with business loss

(this relates to HCAL No.390 of 2000).

(9)

The Corporation should value a cockloft as a mezzanine floor

(this relates to HCAL No.380 of 2000).

CHALLENGE TO THE DECISION OF THE CHIEF EXECUTIVE IN

COUNCIL

The grounds which are common to all the applications against

the decision of the Chief Executive in Council are as follows :

- 9 -

(1)

The resumption orders were based on the recommendations of

the Secretary under section 15 of the LDC Ordinance and

would have no legs to stand on upon the recommendation

being quashed.

(2)

There were procedural impropriety in that the Chief Executive

in Council should have waited for the courts ruling on the

application against the Secretary before acting on the

recommendation, and that the Applicants had been deprived

of the opportunity to properly making representations to the

Chief Executive in Council.

(3)

The Lands Tribunal is not the proper forum.

(4)

Courts discretion.

The Applicants are also relying on the same issues unique to

individual applications.

THE FOCUS

Although I will follow the structure of the issues identified by

the Applicants, it is necessary to bear in mind that the challenge is against

the decision of the Secretary in making the recommendation to the Chief

Executive in Council and the latters decision to order resumption of the

properties. Hence, the focus must be on the decision and the

decision-making process of these two decision-makers.

Ambit of judicial review

In judicial review proceedings, the court is not concerned with

the merits of the decision : In re Amin [1983] 2 AC 818 per Lord Frazer at

- 10 -

829A. Furthermore, the court is not concerned with mistake of fact unless

facts are objective in the nature of independently ascertainable and

measurable and the decision-makers concept of the facts is plainly or

unassailably wrong : Chan Sau Mui v. Director of Immigration [1992]

6 HKPLR 479 at page 486 per Cons Ag CJ.

Under section 15(4)(c), the Secretary shall not make a

recommendation unless he is satisfied that the Corporation has taken all

reasonable steps to acquire the land including negotiating for the purchase

on terms that are fair and reasonable. Clearly, by this provision, it is the

Secretary who has to be satisfied with the requirements. Where the words

are satisfied are used, they leave the decision, on these issues of fact, to

the decision-maker; there is no appeal to a court against such a decision,

but it may be subject to judicial review for error of law including absence

of any material on which the decision could reasonably be reached : Din v.

Wandsworth L.B.C [1983] AC 657, at page 664 per Lord Wilberforce.

Where the existence or non-existence of the fact is left to the judgment and

discretion of a public body, and that fact involves a wide spectrum ranging

from the obvious to the debatable or to the just conceivable, it is the duty

of the court to leave the decision of that fact to the public body to whom

Parliament has entrusted the decision-making power save in a case where

it is obvious that the public body, consciously or unconsciously, are acting

perversely : Reg v. Hillingdon L.B.C , ex parte Puhlhofer [1986] AC 484,

at page 518 per Lord Brightman.

Judicial review and land resumption

It is necessary at the very beginning to set out the ambit of

judicial review in resumption cases. The principles are recently considered

- 11 -

by the Court of Appeal in Wong Tak Woon v. The Secretary for Planning,

Environment and Lands, CACV339, and approved by the Court of Final

Appeal in an application for leave to appeal against the decision of the

Court of Appeal (FAMV No.9 of 2000). Keith JA in the Court of Appeal

stated that :

it was not arguable that, in assessing the compensation for

land resumed pursuant to a recommendation to the Chief

Executive under the Land Development Corporation Ordinance

(Cap.15), account may be taken of the value of such property as

would be built on the land under any proposed development.

Ribeiro J (as he then was) stated that :

a judicial review of the offer of acquisition was precluded by

the Ordinance because it provides the intended machinery under

the Lands Resumption Ordinance for determining the value at

which land should be acquired when an offer of acquisition is

unacceptable to the land owner [and] this left no room for an

application for judicial review of an offer considered to be too

low.

it was entirely proper for the [Land Development

Corporation] to be guided by the amount of compensation

achievable under the prescribed [Lands Resumption Ordinance]

machinery when deciding what would be a fair and reasonable

offer since that was the fallback position if agreement could not

be reached.

It should be pointed out that when Keith JA referred to the

value of the property that would be built on the land under any proposed

development, he was not referring to the development value of the

property itself, but rather the value of redevelopment of the applicants

own property together with other properties resulting from the

implementation of the development scheme. Keith JA stated that he had

some reservations on the view expressed by Ribeiro J on whether a

challenge to the fairness and reasonableness of terms offered by the

Corporation as prima facie not the subject of judicial review because the

- 12 -

statutory regime for the assessment of compensation under the Lands

Resumption Ordinance only becomes relevant once the Secretary is

satisfied that the terms of the offer were fair and reasonable. He,

however, stated that it was not necessary for him to say any more about the

matter in view of his opinion on the case.

Mr Leongs submission

Mr Leong SC, counsel for the Applicants, accepted that no

case can be made out in a judicial review of the Secretarys

unreasonableness and unfairness based only on different views taken by

valuers on pure figures that are within their professional expertise to take.

However, he relied on the comment of Keith JA and submitted that the

statutory framework contemplated a two-stage process, and the court is

entitled to adjudicate on whether the Corporation had behaved fairly and

reasonably relating to matters more fundamental than just figures. These

matters affect whether the Secretary is justified in declaring himself

satisfied about the fairness and reasonableness of the Corporations offer

for the purposes of section 15(5). These matters include whether the

Corporation had fairly and reasonably engaged land owners by its manners

of conducting negotiations with them, and whether the approaches of

valuation were wrong in principle. The Applicants seek to distinguish

Tsang Kam Lan v. Secretary for Planning, Environment and Lands and

Governor-in-Council, HCMP325/1997 and Wong Tak Woon on the basis

that the owners there were seeking a compensation based on the marriage

value of the properties, i.e. the value of the owners property together with

other properties in the redevelopment scheme. As such their claim was

bound to fail, hence these two cases are not authority to exclude from

- 13 -

consideration matters of valuation in a judicial review if such matters

affect the principles of valuation.

Mr Leong submitted that the Lands Tribunal is the expert for

valuation of the affected properties but it has no jurisdiction to review

whether the valuations by the Corporation are fair and reasonable, or

whether the Secretary is legal, rational or procedurally proper in his

decision to make the recommendation. The Lands Tribunal cannot always

compensate the Applicants for loss suffered consequential upon an illegal,

irrational, procedurally improper decision of the Secretary. In this case,

property value had dropped since the offer was made by the Corporation.

Mr Leong submitted that only the court can bring about a fresh offer by the

Corporation based on a higher valuation at the time of the Corporations

offer by quashing the Secretarys decision to recommend resumption.

No further room for argument

Despite the reservation of Keith JA on this matter, what

Ribeiro J had stated was expressly approved by the Court of Final Appeal.

In my view, there really is no further room for argument on the issue of

valuation not being subject to judicial review. Many of the issues relied by

the Applicants fall within this ambit. On the so-called principles of

valuation, on analysis, some of them are really not principles as such. Of

the others, and on the manner of negotiation, the focus must be on whether

the Secretary had material on which his decision could reasonably be

reached.

The Applicants further argued that the compensation to be

decided by the Lands Tribunal would not provide them with adequate

- 14 -

relief because any valuation of the properties by the Lands Tribunal would

be based on the date of resumption and not on 23 June 1997, the valuation

date on which the Corporation made its offer. The current market value of

the properties is less than that on 23 June 1997.

This is also one of the arguments advanced before the Court

of Appeal in Wong Tak Woon. Nonetheless, Ribeiro J (as he then was) was

of the view that matters relating to valuation are not amiable to judicial

review.

THE OFFER BEING MADE TOO LOW

This is clearly a matter that falls outside the ambit of judicial

review. The Applicants retained two firms of valuers, namely, F. C. Tam

Surveyors Limited and First Pacific Davis (Hong Kong) Limited in valuing

their properties. The Corporation instructed two firms of valuers, namely,

Vigers (Hong Kong) Limited and Larry H.C. Tam & Associates Limited to

value the properties. The higher of the two valuations received by the

Corporation was used as the basis of its offer to the Applicants. On the

authority of Wong Tak Woon, the court is clearly precluded from going into

matters purely on the differences in the valuation of the experts.

In discharging his duty, the Secretary instructed a firm of

independent consultant, namely, Messrs James Ng Surveyor Limited (the

Government Consultant), to prepare a valuation of the properties. The

Applicants relied on a table provided to members of the Central and

Western District Board in about March 2000, showing a comparison of the

offers made by the Corporation and a valuation of the properties by the

Government Consultant. The assessment of the Government Consultant is

- 15 -

on the open market value of the properties. The Applicants contended that,

while each and every item of the Corporations offer is higher than the

valuation of the Government Consultant, the table is misleading in the

sense that the Corporations offers represented not only the market value of

the properties as at July 1997 but also an award of ex gratia payment on

top of the market value.

In my view, this is an argument which is difficult to accept.

The offer made by the Corporation was based on the open market value of

the properties plus an ex gratia payment. It must be the offer as a whole

which has to be judged in determining whether the offer is reasonable.

The Secretary had consulted an independent consultant whose valuation

showed that the offer made by the Corporation is higher than his own

valuation.

This is the basis on which he concluded that the term offered

was fair and reasonable. As Godfrey JA stated in Secretary for Justice v.

Prudential Hotel BVI Limited [1997] 3 HKC 244, it is not appropriate for

the judge to compare the evidence of the two experts and to express his

preference for one of the experts and disregarded the other. It is not the

function of the judge even to consider which of the two is to be preferred.

The function of a judge is simply to see whether there is evidence before

the decision-maker upon which he can legitimately and rationally draw the

conclusion. In the circumstances, there clearly is evidence on which the

Secretary can be legitimately and rationally satisfied that the statutory

requirement had been met.

Home purchase allowance

The offers made to No.2 and No.4 Kin Man Street

- 16 -

Related to the issue of the offers being made too low is the

payment of an ex gratia payment called Home Purchase Allowance

(HPA). In the majority of the cases, the Corporation had made

two offers to the Applicants, the first is on the basis of a sale of their

properties with vacant possession and the second offer is on the basis of a

sale subject to tenancy. In respect of shop premises an additional 5%

incentive payment was included. In certain cases, additional offers were

also made. The argument relied by the Applicants is the huge disparity in

the offer made to one of the properties, namely No.4 Kin Man Street

(No.4) and its immediate neighbour, No.2 Kin Man Street (No.2).

No.4 is a four-storey building. The Corporation made an offer of

$4.726 million to the owners for the whole building. However, the

Corporation acquired the ground floor of No.2 for the sum of $4.3 million.

The breakdown of this sum of $4.3 million showed that $1,667,000 was

for the open market value, $2,693,000 was for an ex gratia allowance, and

$100,000 was for other costs.

The policy and its rationale

The policy of the Corporation is that if the occupation permit

of the premises shows that the premises is for domestic use, then it will

pay the HPA to the owner irrespective of the actual use of the premises. If

the premises is owner-occupier, the HPA is the full 100%. If the premises

is tenanted, then the owner will receive between 50-70% of the HPA. HPA

is not provided to the owner if the owner owns the whole building. In such

a case, the offer will be the higher of the redevelopment value or the

existing use value of the building plus an ex gratia allowance of 10%.

No.4 is a single ownership building, and as a result, the owners were not

offered any HPA.

- 17 -

Although there is no written statement on this matter, it seems

that the rationale for excluding the payment of HPA to single ownership

building is because the owner can redevelop the whole of the building, and

therefore does not require HPA. The irony in this case is that the

redevelopment value of No.4 is lower than the existing use value. There is

no dispute that the area of the ground floor of both No.2 and No.4 is the

same size. While No.2 is owner-occupier, No.4 is tenanted. But apart

from this, if No.4 is not owned by a single owner, its owners will be

entitled to HPA although at a lower percentage. The question becomes

whether the difference in offers made in respect of these two adjoining

buildings are so anomalous that the decision of the Corporation can be

termed as an irrational decision. It follows from this whether the Secretary

can be satisfied that the Corporation had been negotiating for the purchase

on terms that are fair and reasonable.

Decision not unfair or unreasonable

Although, on the facts, No.4 may have received a much lower

offer because of the exclusion of HPA, I have come to the view, after some

initial hesitation, that the Applicants are precluded from contending

that the Corporation had negotiated on terms that are unfair and

unreasonable. First, the payment of HPA is based on a Government policy

which had been approved by the Legislative Council. The exclusion of

payment of HPA to single ownership buildings seems to be based on

rational grounds because of the redevelopment potential that is available to

the owner of the building. Until such a policy is changed, the Corporation

really has to abide by the policy. Second, as shown in cases such as

Chan Mok Yee and Cheung Fung Jan trading under the name of Ocean

- 18 -

Paper Products Factory v. The Attorney General, HCA6881/1980, and

Chan Sik Cheung v. The Director of Lands [1995] 3 HKC 199, an ex gratia

payment is a voluntary payment of a gratuitous nature and is not

justiciable. This by itself is not determinative of the issue because more

importantly, as Henry LJ said in R. v. Independent Television

Commissioners ex parte Virgin Television Limited [1996] EMLR 318 at

page 336, fairness means the decision-makers duty to be even-handed, to

treat all applications alike in the sense that the same rules are applied to

them and that each applicant receives or would receive the same treatment

under those rules ... they must be treated alike, in that the same criteria

for judgment under the Rules must be applied to each, even though

the results would be different. (emphasis added). This is precisely what

happened in the present case, the ex gratia payment was applied in

accordance with the same set of policy that was applicable to owners

affected by the redevelopment although the result was different. Third, the

owners of No.4 had never accepted that the redevelopment value of their

property is lower than the existing use value. On the contrary, their own

valuer assessed the redevelopment value at $9 million. The owners of

No.4 had never indicated that they were prepared to accept the HPA on the

basis that the existing use value is higher than the redevelopment value.

Had they so indicated, and if the Corporation had nonetheless refused to

grant them the HPA, then there may be some ground for saying that the

Corporation had not negotiated on terms that are fair and reasonable. This

is not the situation here.

The Applicants relied on a Singapore case : Seah Hong Say

(trading as Seah Heng Construction Co.) v. Housing and Development

Board [1993] ISLR in which land owners issued a writ claiming ex gratia

- 19 -

payment awarded in respect of a building compulsory acquired by the

government. The Court of Appeal of Singapore dismissed the application.

Lai Kew Chai J held that :

In our judgment there can, by definition, be no legal entitlement

to an ex gratia payment, though the potential recipient of such

payment might have a right to expect that the decision as to his

award should be properly made, and may enforce that right by

the process of judicial review, to ask, for example, that a decision

improperly arrived at be quashed by certiorari or that a proper

process be followed by mandamus.

Read in the context of the case, what the judge said clearly is not an

authority for saying that claim for ex gratia payment can be made in

judicial review proceedings. This case does not assist the Applicants.

FAILURE TO DISCLOSE COMPARABLES

The Applicants argument

The Applicants contended that the Corporation had acted

unfairly and unreasonably by failing to provide comparables on which the

Corporations surveyors had relied to value their properties. In the absence

of such comparables, they were unable to make worthwhile representations

to the Corporation during the negotiation. Mr Leong characterised this

complaint as one which relates to the manner in which the Corporation

carried out the negotiation. He submitted that the Secretary must not only

be concerned with the question of valuation, but also the manner in which

the negotiation was made in order to satisfy himself that the Corporation

has taken all reasonable steps to acquire the land including negotiating for

the purchase on terms that are fair and reasonable.

- 20 -

The factual disputes

To deal with this issue, it is first of all a matter of fact that the

valuation reports from the Corporations valuers were disclosed to the

Applicants and their valuers upon request. Mr Keen of the Corporation

stated that the Corporation does not normally provide comparables to

property owners directly since the interpretation of comparables more

often than not requires experts knowledge on valuation principles which

the owners may not possess. It is and has always been the Corporations

practice to provide copies of its valuers reports to property owners and

their valuers upon request, and to disclose comparables to the Applicants

valuers. As disclosed in the evidence of Mr Keen, comparables were

discussed at various meetings with the owners experts on the following

properties, namely :

(1)

2A, 10 and 10A Davis Street.

(2)

107 Catchick Street

(3)

1, 15, 17 and 27 Cadogan Street

As to the allegation of the Corporation failing to disclose

comparables, all that the Applicants had identified was one instance in

which the owner of No.2H Davis Street (No.2H) requested comparables

on 9 November 1998. The Corporation refused to provide the comparables

to this representative. The owner of No.2H had in fact at that stage

instructed a surveyor on his behalf. Clearly, if the surveyor considered that

comparables were required, he could have asked for them. In my view, the

Applicants had failed to make out a case on the facts that the Corporation

had failed to disclose comparables to them.

- 21 -

No obligation to discuss comparables

What is more important is whether the Applicants are entitled

to the comparables as of right. Under the LDC Ordinance, the Corporation

is required to conduct its business according to prudent commercial

principles : section 10(1). The task of the Corporation is to purchase the

properties of the owners in order to carry out the redevelopment scheme.

No lis between the parties

Mr Leong submitted that the role of the Corporation is unique

because once it is known that properties are to be resumed, then really the

owners cannot freely dispose of their properties except to the Corporation.

Even proceeding on the basis that the role of the Corporation is unique, the

fact remains that in negotiating for the purchase of the Applicants

properties, the Corporation is merely an intended purchaser of the

properties. Apart from a purchaser and buyer situation, there really is no

lis, or in modern language a suit, action, controversy or dispute between

them. This being the case, there is no question of the Applicants being

entitled to have comparables of valuation provided to them in order for

them to make representations. In Johnson & Co. (Builders), Ltd v.

Minister of Health [Aug 6, 1947] 2 All ER 395, the owners of land in a

compulsory purchase order applied to quash the order on a ground that the

Minister of Health, in considering objections to it, was bound to act in a

quasi judicial manner and that he had failed in that duty by not making

available to the objectors the contents of certain documents. It was held

that there was no obligation on the Minister to provide the material.

Lord Greene, MR stated that :

... Lis, of course, implies the conception of an issue joined

between two parties. The decision of a lis, in the ordinary use of

- 22 -

legal language, is the decision of that issue. The consideration of

the objections, in that sense, does not arise out of a lis at all.

What is described here as a lis the raising of the objections to

the order, the consideration of the matters so raised and the

representations of the local authority and the objectors is

merely a stage in the process of arriving at an administrative

decision.

Commercial dispute

In Mass Energy Ltd v. Birmingham City Council [1993]

Env. L.R.298, different parties submitted tenders for a contract to the local

authority. The local authority accepted one of the tenders. Another party

who had their tender rejected applied for judicial review against the

decision to accept the tender. It was held that it was open to the local

authority to choose one tenderer in preference to others. Glidewell LJ held

that, on its face, it is a commercial dispute between a successful and an

unsuccessful tenderer. The fact that the local authority is restricted by

statute on how to accept contracts does not make it a public law dispute.

Evans LJ stated that In commerce, life is not always fair. The authority

was entitled to act as a commercial animal at the stage when it was

considering the tenders they had received. I find it impossible to say more

than that the council were bound to act commercially. That unfortunately,

does not guarantee complete fairness and may be the plaintiffs did not

receive it, but that is not a ground, in my view, for complaining under the

Act.

Lord Ackner in Walford v. Miles [1992] 2 AC 128, at 138E

held that :

... However the concept of a duty to carry on negotiations in

good faith is inherently repugnant to the adversarial position of

the parties when involved in negotiations. Each party to the

- 23 -

negotiations is entitled to pursue his (or her) own interest, so

long as he avoids making misrepresentations.

In my view the opinions expressed in these cases are clearly

applicable to the present case. Mr Leong submitted that since the

Secretary was obliged to consider whether there was negotiation on terms

which are fair and reasonable, this means the Corporation could not simply

apply prudent commercial practice in its dealings with the Applicants.

I agreed with Mr Yu SC, counsel for the Corporation, that one has to focus

on the terms and asked whether they are fair and reasonable, and one must

not confuse with the notion of terms which are fair and reasonable with

any concept of duty to act fairly.

FAILURE TO REALLY NEGOTIATE WITH THE APPLICANTS

The complaint

The Applicants contended that the Corporation failed to really

negotiate with them to arrive at an offer agreeable to all parties, but

remained firm in its own stance throughout. They complained that the

offers made by the Corporation were simply on the basis of vacant

possession or subject to tenancy. In some cases, a further offer with an

additional 5% incentive was given. This demonstrated inflexibility on the

part of the Corporation. The Corporation rejected the counter-offers of the

Applicants without explanation, thus leaving no room for further

negotiations. The Corporation had further failed to provide comparables of

the valuation. This last matter is one I had already dealt with.

Falling market

- 24 -

In my view, there is no merit in this argument. According to

the Corporation, its position is that it does not offer at below market price

and bargain upwards. Its practice is to make offers according to the higher

of two independent valuations. The offers are open for acceptance for a

sufficient time to enable the owners to take advice and consider

acceptance. Once these offers lapsed, any new offers that the Corporation

makes would have to take into account the prevailing market condition. In

the present case, the Corporation made its first offers in July 1997. The

deadline for the first offer was three months which was subsequently

extended. These offers were left open until 8 January 1998 or 28 February

1998 despite the falling market. The Corporation in adopting the practice

had successfully acquired 90% of the properties affected by the

development proposal. In Silver Mountain v. Attorney General [1994] 2

HKLR 297, a number of offers were made in view of a rising market. It is

not the case here. The fact that the Corporation had in the majority of

cases only made two offers to the Applicants is not something that could be

held against it.

Failure to give reasons for rejecting the counter-offer

As to the failure by the Corporation to give reasons in

rejecting the counter-offer, there really is no duty on the Corporation to do

so. It was simply purchasing the properties from the owners.

Furthermore, a comparison of the Corporations offers and the Applicants

counter-offers in eight properties revealed that the majority of the

counter-offers in fact exceeded the offers by as much as two times. This

being the case, it would be unreal to demand the Corporation to give

reasons for rejecting the counter-offer.

- 25 -

A Comparison of the Corporations Offers and Applicants Counter-offers

The Corporations Offers

Applicants Counter-offers

37

9

2nd Offer (26.10.98)

HK$4,972,000

1 counter-offer on 19.5.98:

HK$7,389,900

38

0

Revised Offer (6.2.98)

HK$7,599,000

1 counter-offer on 2.9.97:

HK$19,029,100

38

1

3rd Offer on 12.2.98

HK$7,208,000

1st counter-offer on 29.5.98 at

2nd counter-offer on 22.8.98 at

HK$13,568,850

HK$12,890,407

38

2

2nd Offer on 13.1.98

3rd Offer on 26.10.98

HK$6,572,000

HK$4,830,000

1st counter-offer on 29.5.98 at

2nd counter-offer on 22.8.98 at

HK$13,838,175

HK$13,146,266

39

0

2nd Offer on 26.10.98 at:

No.15: (ET + ex-gratia)

No.17: (ET + ex-gratia)

HK$3,798,000

HK$3,832,000

1 counter-offer on 9.6.98 at

HK$13,725,000

No.15 (ET only)

HK$5,870,000

No.17 (ET only) Business loss: HK$5,870,000

HK$1,985,000

39

2

2nd Offer (25.10.97) (ET) HK$5,908,000

3rd Offer (6.2.98) (ET)

HK$6,203,000

4th Offer on 18.1.99 (VP) HK$5,295,000

1st counter-offer on 15.12.97 at HK$7,500,000 (ET)

2nd counter-offer on 10.7.98 at HK$7,500,000 (VP)

3rd counter-offer on 21.8.98 at HK$7,380,000 (VP)

39

4

2nd Offer on 13.1.98 at

3rd Offer on 26.10.98 at

4th Offer on 7.12.98 at

HK$4,149,000

HK$3,764,000

HK$4,696,000

1st counter-offer on 29.5.98 at

2nd counter-offer on 22.8.98 at

HK$10,831,500

HK$10,272,825

39

6

2nd Offer on 6.2.98 at

3rd Offer on 26.10.98 at

4th Offer on 7.12.98 at

HK$4,668,000

HK$3,764,000

HK$4,696,000

1st counter-offer on 29.5.98 at

2nd counter-offer on 22.8.98 at

HK$10,813,500

HK$10,272,825

BREACH OF SECTION 15(5) OF THE LDC ORDINANCE

In a letter dated 16 June 1999 from the Director of Lands

(the Director) of the Lands Department to the owners of No.4 Kin Man

Street, the Director referred to the assessment of the open market value of

the properties by the Government Consultant. He stated, among other

things, that :

Please be assured that the valuation assessment was

prepared by the Consultant and audited by the LDC Section of

the Lands Department. The assessment is to assist SPEL in

deciding if LDCs offer is fair and reasonable for the purpose of

handling the land resumption application submitted by LDC.

- 26 -

The Applicants seized on the word audited and argued that

by allowing the LDC Section to audit the valuation assessment prepared by

the Government Consultant, the Secretary was in breach of section 15(5)

of the LDC Ordinance. In Kaisilk, I stated that this section is both an

enabling and a prohibition section. The prohibition is against the Secretary

from consulting a public officer on matters such as valuation which are

relevant to determine whether a fair and reasonable offer had been made.

The Applicants argued that as the auditor of the Government

Consultant, the LDC Section was actively involved in matters of valuation

which are relevant to determining whether a fair and reasonable offer had

been made. It is natural and reasonable to assume that if the LDC

Sections auditing indicate that the valuation of the Government

Consultant is wrong, the Secretary would not have made the decision.

They also referred to the affirmation of Patrick Lau (Mr Lau), the

Deputy Secretary for Planning and Lands who held the position of the

Secretary for Planning and Lands (Acting). Mr Lau stated that on 2 March

2000, Mr Ho Siu Shun (Mr Ho) who is the Assistant Secretary in the

Urban Renewal Unit of the Planning and Lands Bureau, had reported to

him about all aspects of the Corporations application; after fully

considering all the materials submitted to him including the various

contentions of the Applicants, he (i.e. Mr Lau) was satisfied that, among

other things, Mr Ho, the LDCS and the government consultant had

thoroughly considered the representations from the owners and concluded

that the grounds of objection raised by the owners were unfounded to

which conclusion I have in agreement.

- 27 -

Mr Hos explanation

Mr Ho in his affirmation stated that the auditing of the

valuation assessments prepared by the consultant was meant to refer to

work of the LDC Section in checking the accuracy of the data, calculations

and measurements. The LDC Section could not and did not in any way

attempt to change, interfere with or overrule the consultants opinion on

valuation matters or on the terms of the Corporations offers. Mr Ho

explained that the LDC Section is a section of staff who possess expertise

in property valuation and market practices. Apart from collating and

summarising the representations made by the Applicants and the

Corporation in respect of the section 15 applications for the Secretarys

consideration, the LDC Section is entrusted with the work of instructing

the Government Consultant to give advice as to the value of the properties

and whether the Corporations offer had been reasonable in monetary

terms. The Director himself played no part in the section 15 applications

or the Secretarys decision to recommend resumption. In relation to the

processing of these applications, the LDC Section takes instructions from

and reports to the Secretary directly. The reason why the Director wrote to

the Applicants in June 1999 was because of specific complaints made to

him about the alleged misconduct of the LDC Section which had to be

replied to and addressed.

My view

- 28 -

In my view, what Mr Ho said must be the end of the matter.

The Applicants had read too much into the word auditing. Further, Lord

Diplock in Bushell v. Secretary of State for the Environment [1981] AC 75

had held that :

The collective knowledge, technical as well as factual, of the

civil servants in the department and their collective expertise is

to be treated as the Ministers own knowledge, his own expertise.

This is an integral part of the decision-making process itself.

It is not to be equiparated with the Minister receiving, expert

opinion or advice from sources outside the department

As I had said in Kaisilk, the Secretarys reliance on the assistance of the

LDC Section is not by way of consultation. The work of the LDC Section

is a necessary part of the process in order to enable the Secretary to reach a

decision on the matter. The Secretary is clearly entitled to rely on the

collective knowledge, experience and expertise of the government offices

serving directly or indirectly under his bureau. In my view, there is no

breach of section 15(5). This being my view, it is not necessary for me to

consider further the arguments of the Respondents and the Corporation that

since the Applicants had specifically asked the Lands Department to use its

expertise and knowledge of the property market in advising the Secretary,

they must have waived any breach of nature justice : Supperstone and

Goudie, Judicial Review, 2nd Edn. para.8.60. It is also not necessary to

revisit the arguments on the Carltona principle.

WEDNESBURY IRRATIONAL

The Applicants contended that in all the circumstances no

reasonable Secretary would have made the recommendation. It is not

necessary for me to repeat the general principles stated in cases such as

Associated Provincial Picture House Limited v. Wednesbury Corporation

- 29 -

[1948] 1 KB 223 or Secretary of State for Education and Service v.

Tameside Metropolitan Borough Council [1977] AC 1014. In my view the

Applicants clearly failed to make out a case of Wednesbury

unreasonableness.

THE SECRETARY FAILING TO GIVE REASONS FOR HIS DECISION

The correspondence

The Applicants complained to the Director by letter dated

26 May 1999. They said that they were dissatisfied with the unfair

handling of the relevant acquisition procedure by the Corporation, the

unfair valuation assessment by the surveyor of the Corporation and the

improper handling of their complaints by the Acquisition Department

LDC Section. A similar letter was written to the Secretary. In response,

the Director by letter dated 16 June 1999 wrote to the Applicants stating,

among other things, that if the Secretary is satisfied that a recommendation

for land resumption to the Executive Council can be made, you will be

informed of the reasons leading to this decision. On 10 March 2000, the

Director wrote to two of the Applicants stating that :

I am instructed to inform you that the Secretary has carefully

considered your representation together with all other relevant

information available, and he is now satisfied that the

Corporation has taken all reasonable steps to otherwise acquire

the land including negotiating for the purchase thereof on terms

that are fair and reasonable, and the Secretary has under

section 15 of Land Development Corporation Ordinance

(Cap.15) decided to recommend to the Chief Executive in

Council the resumption of your above property under the Lands

Resumption Ordinance (Cap.124).

The complaint

- 30 -

The Applicants complained that they were promised to be

given reasons for the decision. The letter of 10 March 2000 did not give

any reasons, instead the letter merely repeated the wording of section 15(4)

(c) of the LDC Ordinance without providing specific grounds. As a result,

they are precluded from making any useful representations to the Chief

Executive in Council. The Applicants argued that the promise by the

Director had given rise to a legitimate expectation on their part. The

statement which gives rise to the legitimate expectation is clear,

unambiguous and devoid of relevant qualification; further, it is not

necessary for the Applicants to have changed their position or to have

acted to their detriment in order to obtain the benefit of a legitimate

expectation : Hong Kong and China Gas Company Limited v. Director of

Lands [1997] 3 HKC 520. Procedural fairness will very often require that

a person affected be informed of the gist of the case which he has to

answer in order to make worthwhile representations : R v. Home Secretary,

ex parte Doody [1994] 1 AC 531, followed in Fok Lai Ying v. The

Governor-in-Council and others [1997] HKLRD 810.

Justification for legitimate expectation

The justification for the principle of legitimate expectation is

that when a public authority has promised to follow a certain procedure, it

is in the interest of good administration that it should act fairly and should

implement its promise, so long as implementation does not interfere with

its statutory duty. Further, when the promise is made, the authority must

have considered that it will be assisted in discharging its duty fairly by any

representation from interested parties : Attorney General of Hong Kong v.

Ng Yuen Shiu [1993] 2 AC 629 at page 638, per Lord Fraser of

Tully Belton. See further, the comment of Megarry J in John v. Rees

- 31 -

[1970] 1 Ch.345 at page 402 on the importance of the rule of natural

justice.

Obligation to give reasons

On the requirement to give reasons, the common law, which

encompasses the principle of natural justice, does not of itself require a

public law authority or tribunal always, or even usually, to give reasons for

its decision; nevertheless, circumstances might establish a special case in

which natural justice would require reasons to be given : Lau Tak Pui &

Others v. Immigration Tribunal [1992] 1 HKLR 374. The case reviewed

the authorities in this area including the decision of the High Court of

Australia in Public Service Board of New South Wales v. Osmond

[1985] 159 CLR 656. Lord Lane CJ in R. v. Immigration Appeal Tribunal

ex parte Khan [1983] 1 QB 790 stated that in respect of the issue which a

tribunal is determining and the basis upon which the tribunal had reached

its determination upon that issue, in many cases it may be quite obvious

without the necessity of stating it, in other cases it may not.

My view

The decision made by the Secretary to recommend

resumption is purely an administrative decision. As a general rule, he is

not obliged to give reasons for his decision. However, in this case, the

Director had informed the Applicants that if the Secretary should decide to

make the recommendation, he would give reasons. The Lands Department

is one of the departments under the Planning and Lands Bureau (the

Bureau) headed by the Secretary. The Bureau is responsible for policy

formulation. The departments under it, including the Lands Department,

are responsible for policy implementation : Kaisilk. It would be too much

- 32 -

to expect from the laymen that they should know precisely about the

hierarchy of the government structure. All that they were concerned with

is how their properties would be dealt with by the authority. Although the

promise to give reasons for the decision was not given by the Secretary

himself, in my view, the present case is one of the special cases, in which

the Secretary is required to give reasons for his decision because of the

earlier promise by the Director.

What is a special case depends on the facts of each case. It is

not necessary for me to rule whether with this promise, the right had

become crystallised. It is sufficient for me to say that as a matter of good

administration, the authority should observe what it had openly stated on

this issue. This is in fact what happened in this case : the reasons for the

decision were given in the letter dated 10 March 1999. In my view, the

reasons given by the Secretary were sufficient reasons. It identified the

issues in which the Secretary had to decide. This is not a case where the

Secretary was not aware of the concerns of the land owners prior to his

recommendation. The LDC Section had been in correspondence with the

land owners. The land owners had complained about the manner of

negotiation of the Corporation and its disregard of the valuation and

evidence produced by the owners surveyors. The LDC Section had called

for the Corporations comments, a summary of the owners complaints and

the comments were provided to the owners. In the letter dated 18 May

1999, the LDC Section informed the land owners that their comments and

the LDCs response would be presented to the Secretary for his

consideration under section 15 of the LDC Ordinance. The land owners

had made further representations to the Secretary.

- 33 -

Mr Wong, counsel for the Respondents, referred to Bolton

MDC v. Secretary for Environment [1995] 3 PLR 37 in which the House of

Lords was concerned with town planning rules which required the

Secretary of State to notify his decision and his reasons for it in writing to

persons affected. The regulation also required the Secretary of State to

have regard to the provisions of the development plan and to any other

material considerations. Lord Lloyd stated that there is nothing in the

statutory language which requires the Secretary of State, in stating his

reasons, to deal specifically with every material consideration, otherwise,

his task would never have been done and the decision letter would be as

long as the inspectors report; he has to have regard to every material

consideration but he needs not mention them all. Latham J stated in R v.

The Secretary of State for Education, ex parte G [1995] VLR 58 at

page 67G that : What might appear to the uninformed observer to be a

statement of a conclusion will be to the other person concerned with the

way in which a dispute has developed, a full and sufficient explanation of

the reason for the decision. The reasoning of the two cases apply equally

here. See also R. v. The Chief Constable of the Thames Valley Police

ex parte Cotton [1990] IRLR 344.

The letter of 10 March 2000 clearly provides a full and

sufficient explanation of the reasons for the decision bearing in mind the

history of the matter. In any event, Mr Ho had given detailed reasons of

the decision on affidavit. The authors of De Smith, Judicial Review of

Administrative Actions, 5th Edn. para.9-005 suggested that where a

decision-maker attempts to remedy a failure to give reasons by providing

justification of the decision in affidavit evidence on judicial review, the

court is unlikely to quash the decision or make any order unless the

- 34 -

reasons so disclosed are inadequate or unlawful. The reasons disclosed in

the affidavit clearly cannot be so described.

The Applicants complained that the failure to give reasons by

the Secretary at the time of the recommendation precluded them from

making any useful representation to the Chief Executive in Council. The

reality of the situation is that the Applicants had not indicated what new

representations they would have made in the light of all the reasons

disclosed.

The Applicants further relied on In re Le Tu Phuong and

Another [1993] 2 HKLR 303 where Liu J (as he then was) held that where

reasons are given, they must not be so vague, inadequate and unintelligible

as to cloud the issue and the evidential basis. Once given, the reasons

ought to measure up to the standard of administrative law principles. In

my view, the reasons given for the Secretarys decision, in the whole

context of the negotiation, clearly fulfill the obligations imposed by

administrative law principles.

MATTERS RELATING TO THE LANDS TRIBUNAL AND HIGH COURT

JUDICIAL REVIEW

I had already dealt with the arguments on these matters

earlier.

INDIVIDUAL CASES

REDEVELOPMENT VALUE OF NO.4 KIN MAN STREET

- 35 -

No.4 Kin Man Street is a four-storey building. The

Corporation obtained a valuation report from Vigers who assessed the

existing use value of the property at $5,101,000 and the redevelopment

value at $4 million. The redevelopment value was based on a plot ratio of

2.2. The offer made by the Corporation to the owners of No.4 Kin Man

Street was based on the higher of the two valuations plus an ex gratia

payment. Thereafter, there were discussions between the owners and the

Corporation regarding the plot ratio of the property. The owners argued

that the property could have attracted a much higher plot ratio and a

six-storey building could be built.

On 20 May 1998, Vigers prepared a further valuation of the

property using a plot ratio of 4.5 on the assumption that a six-storey

building could be built. The redevelopment value based on this

assumption came up to $5.2 million. However, after deducting domestic

tenant compensation of $948,000 and other adjustments, the

redevelopment value was assessed at $4,268,000. This is still lower than

the existing use value. By letter dated 28 May 1998, the Corporation

informed the expert instructed on behalf of the owners of No.4 Kin Man

Street that although it did accept the argument that the property could be

redeveloped to a six-storey building, it had obtained further valuation on

the redevelopment value of the property under this assumption. The value

that was assessed was still lower than the existing use value.

In January 1999, the expert for the owners asked the Building

Authority to determine the plot ratio of the property. The Building

Authority, on 12 February 1999, stated that it would allow a plot ratio of

4.37 for the redevelopment of the property. By then the offers made by the

- 36 -

Corporation had long lapsed and the Corporation had requested the

Secretary to make the recommendation.

Factually, the Applicants were wrong when they said that the

Corporation had not taken into account, the redevelopment potential of

their properties. Furthermore, the plot ratio used by the Corporation was in

fact higher than the one permitted by the Building Authority. The owners

complained that the valuation report of Vigers of May 1998 was not

supplied to them until much later in August 1999. I do not see how this

would assist the owners because the Corporation had clearly stated in the

letter of 28 May 1998 that a further assessment had been made by the

valuation consultants. Surely, the experts for the owners could have asked

for a copy of this report instead of making the request much later on.

Furthermore, on the authority of Wong Tak Woon, matters relating to the

actual calculation of plot ratio are valuation matters and are not subject to

judicial review. More importantly, the Secretary clearly had a rational

basis to make the recommendation because the Government Consultant

was of the view that the offers made by the Corporation were reasonable.

RIGHT OF WAY

The owners of No.4 Kin Man Street granted a right of way to

the adjoining property owner in respect of a side lane. The Applicants now

contended that the side lane should not be excluded from valuation.

Factually, the owners own experts had excluded the lane from the

calculation of the value of the property. The owners now relied on

two cases in support of their argument that the right of way should be

included for the purpose of calculating the property value. In Cinat

- 37 -

Company Ltd v. The Attorney General [1994-95] CPR 59 it was held by

the Privy Council that :

A development site might include some particular area of

land owned or controlled by the developer which was not

intended to be built on but which was necessary to enable the

proposed building to comply with regulations. There was no

basis for assuming that the unbuilt on part of land in a proposed

development was to be confined within some notional curtilage.

As rightly pointed out by Mr Yu, the question there was whether the

redevelopment could take place on a vacant piece of land once it had been

included as part of a site for the purpose of calculating permissible site

coverage and plot ratio of another development. It does not establish the

principle that land which is subject to a right of way can be included in the

site area for the purpose of assessing the plot ratio. In Lea Tai Property

Development Ltd v. Incorporated Owners of Leapoint Industrial Building

Ltd. [1996] 1 HKC 193, Godfrey JA (as he then was) held that in relation

to interference with an easement :

... the owner of the dominant tenement had no absolute right to

use each and every portion of the right of way. He was entitled

to complain only of substantial interference with that right by the

owner of the servient tenement. The owner of the servient

tenement was the owner of the land and was accordingly entitled

to use it for whatever purposes he liked, so long as he did not

substantially interfere with the use of the way by the owner of

the dominant tenement.

The issue there was whether one party to a deed granting mutual right of

way in respect of a driveway could restrain the other party from using the

driveway. Again, it does not support the Applicants contention that the

right of way should be included in calculating the plot ratio.

- 38 -

The position is governed by Regulation 23(2)(a) of the

Building (Planning) Regulations which provides :

In determining for the purposes of regulation 20, 21 or 22, the

area of the site on which a building is erected

(a) no account shall be taken of any part of any street or service

lane;

(b) there shall be included any area dedicated to the public for

the purposes of the passage.

Regulation 20 deals with permitted site coverage. Regulation 21 deals

with permitted plot ratio. Regulation 2 defines street to include any

footpath and private and public street.

The principle is that an area of land over which there are

private rights of passage in an adjoining occupier cannot be taken into

account for the purpose of determining the area of the site by reason of

regulation 23(2)(a); unless and until the rights of adjoining occupiers are

surrendered or extinguished, such an area remains as unavailable for

building purposes as an area dedicated for passage by the general public :

Hinge Well Co. Ltd v. The Attorney General [1988] 1 HKLR 32, per

Lord Oliver of the Privy Council.

TAKING ILLEGAL STRUCTURES INTO ACCOUNT FOR THE

VALUATION

The Applicants submitted that the Corporation in assessing

the valuation should take into account the existence of unauthorized

structures. The structures had existed in the properties for many years and

they had not been challenged by the Building Authority. The

Corporations stand is that in calculating the floor areas, it would only

- 39 -

adopt the latest approved building plans to measure the floor areas. The

reason is to discourage people from constructing unauthorized structures in

contravention of the Buildings Regulations.

The authorities

In my view, reliance on property cases such as Active Keen

Industries Ltd v. Fok Chi Keung [1994] 2 HKC 67 or the recent decision of

the Court of Appeal in Spark Rich (China) Ltd v. Valrose Ltd,

CACV249/1998 is not helpful. They are all concerned with the question of

whether illegal structures present in a property would constitute a defect in

title in conveyancing transactions.

It has been established by a series of land resumption cases

that unauthorized structures do not attract compensation : Cruden, Land

Compensation and Valuation Law in Hong Kong, 2nd Ed., page 81,

Director of Lands and Survey v. Lau Kin and Chan Yau and Others [1977]

HKLTR 95, Director of Lands and Survey v. Lee Yat Ping and Others

[1977] HKLTR 138, Cham Hon Chi v. Director of Lands (Crown Lands

Resumption Ref. No.8 of 1995).

Mr Leong relied on Linen Export Co. Ltd v. Director of Lands

(Crown Lands Resumption Ref. No.24 of 1994), in which the Lands

Tribunal was assessing a claim for compensation under the LR Ordinance.

It expressed the view that whether a cockloft is approved by the Building

Authority or not, such a cockloft affects the market price realized for

shops. This is clearly not a case which establishes that unauthorized

structures will attract compensation in land resumption. All that the

tribunal was concerned with was how the price of a property used as a

- 40 -

comparable could be affected by the presence of a cockloft. In

Chan Kai Yuen and Another v. The Director of Lands (Lands Resumption

Application No.LDLR8/1999), the Lands Tribunal recognized that the

established practice is that the value of unauthorized buildings is to be

excluded from the assessment of compensation. In that case, it enhanced

the unit rate in assessing the ground floor of the premises merely because

of the extra headroom space occupied by an unauthorized cockloft. In

other words, the height of the ground floor was higher than the normal

headroom height in calculating compensation. It does not show that a

cockloft is to be valued for compensation.

COUNTER-OFFER ARGUMENTS

I had already dealt with arguments on failure to give reasons

for rejecting the counter-offers.

FAILURE TO CONDUCT SITE MEASUREMENTS

The Applicants complained that the Corporation should

conduct actual site measurements instead of measuring from the building

plans. In my view as the Corporation is merely purchasing the properties

from the land owners on a commercial basis, there is no duty imposed on it

to conduct a site measurement. Unless it can be shown that the

measurement adopted by the Corporation is so substantially different from

that of the owners, this is hardly a ground of complaint. As a matter of fact

the Corporation was always willing to conduct a measurement of the

properties jointly with the Applicants or their valuers if requested to do so.

This had happened in No.27 Cadogan Street and Nos.105, 107, 115,

117 Catchick Street.

- 41 -

The Applicants stated that the LDC Section had in fact

arranged for a site inspection of the ground floor and cockloft of

No.27 Cadogan Street and there is no justifiable reason not to measure

other properties on site. As explained by Mr Ho, the LDC Section

attended No.27 Cadogan Street in response to repeated request by the

owners to visit the property. The LDC Section agreed to do so with a view

to ascertaining the owners contention on whether there was any

unauthorized structure in the cockloft which might trigger the difference

between the difference in measurement. It was never the LDC Sections

intention to take measurements of the floor area of the cockloft or other

parts of the property. The LDC Section had advised the owners at the site

that the latest approved building plans should be used and that site

measurements should not be relied on.

FAILURE TO TIMELY ADDRESS THE CLAIM FOR BUSINESS LOSS

This concerns Nos.15 & 17 Cadogan Street. A lard factory by

the name of Hoi Yau Lard Factory (the Factory) operated on the ground

floor of these two premises. The owners of these two premises claimed

that the Factory was operated as a family concern. The owners claimed

that it was not until 4 November 1999 that the Corporation agreed to take

the business loss into consideration.

The policy of the Corporation in buying business premises

would depend on whether the business is operated by the owner or by a

tenant. In respect of owner occupier, the Corporation will offer the

valuation plus a 35% ex gratia sum unless the owner can prove actual loss

of business exceeding 35% of valuation, in which case the Corporation

will compensate the owners for actual loss of business. Where the

- 42 -

premises is tenanted, the Corporation will offer valuation plus a 20%

ex gratia sum to the owner and the Corporation will deal with the tenant

separately to compensate him for business loss.

When the Corporation first made its offers to the owners of

these two premises, they were treated as separate properties because the

Corporation was not aware at that time that the owners were related or that

they were related to the proprietor of the Factory. The offers were not

accepted. On 30 December 1997, the owners first mentioned about the

claim for compensation for the business loss of the Factory. The

Corporation explained that it would pay the business loss if owners could

provide evidence to prove the business loss was over 35% of the market

value of the property. The owners surveyor agreed to provide evidence

for claiming business loss.

On 9 June 1998, the owners surveyor submitted a claim for

business loss to the Corporation. However, it was not possible for the

Corporation to assess any claim for business loss because it did not have

access to any audited accounts or tax returns to verify the information.

Then on 10 June 1998, the owners confirmed that they would want the

Corporation to treat the properties as subject to tenancies. However, they

changed their mind again in October 1999 when they informed the

Corporation that they would wish to deal with the acquisition of the

two properties and the question of business loss as one matter. In reply, the

Corporation, on 4 November 1999, asked the owners for the audited

accounts and tax returns of the Factory in order for it to consider the

business loss claim. However, the owners had not responded to this

request.

- 43 -

The owners explained that at the meeting on 10 June 1998,

the Corporation had suggested that the premises should be first sold to the

Corporation under existing tenancy and thereafter the Factory could still

claim business loss as the tenant of the two properties. It was also

suggested that this alternative would be an easier and quicker alternative

for the Corporation to handle. After a further discussion with the

Corporation, the owners were given the impression that if the claim for

business loss was to be separated, it would facilitate the Corporations

valuation of the overall compensation, including business loss of the

Factory, and would facilitate the Corporation to make a new offer. The

owners were led to believe that by picking this alternative, they might end

up with a greater compensation.

Irrespective of the reasons why the owners changed their

mind, the fact remains that after October 1999, when they wished to claim

for business loss, they had not provided proof of their loss. Without

providing the Corporation with such documents, I fail to see how it could

be argued that the Corporation had failed to deal timely with the matter of

business loss of the owners.

INDEPENDENT MEZZANINE FLOOR

In respect of the ground floor of No.27 Cadogan Street, the

Building Authority had approved the extension of a cockloft so that the

whole of the headroom space above the ground floor was covered by the

cockloft. The Applicants contended that the area had become an

independent mezzanine floor so that the salable area of the cockloft should

not be computed as a common cockloft being confined to the interior of

- 44 -

the four walls. They referred to Hinex Universal Design Consultants Co.

Ltd v. Chan Lai Hing [1998] 1 HKC 317, in which Le Pichon J held that a

subsequent owner had the same unfettered right as the developer in the

allocation of undivided shares vested in him, subject to any prior

prohibition which existed in the deed of mutual covenant or some other

documents. The deed of mutual covenant of No.27 Cadogan Street

enabled the owners to dispose of the whole or any part of their share in the

building and their right to use floor of the building allotted to them for

their exclusive use and enjoyment to any person they may think fit. They

further argued that the mezzanine floor had an independent entrance, hence

it should also attract HPA as well.

To deal with this problem, the starting point must be that the

owners had not formally subdivided their interest. There is no formal

documentation that a separate independent floor had come into existence.

In the circumstances, it is hardly reasonable for them to say that HPA

should have been given to them in respect of a separate independent floor

of the building. In any event, there was never any claim for extra HPA

until the matter was raised in these proceedings.