Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

EEG Findings in Dementia With Lewy Bodies and Alzheimer's Disease

Enviado por

Leni Lukman0 notas0% acharam este documento útil (0 voto)

12 visualizações3 páginashmm

Título original

v066p00401

Direitos autorais

© © All Rights Reserved

Formatos disponíveis

PDF, TXT ou leia online no Scribd

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentohmm

Direitos autorais:

© All Rights Reserved

Formatos disponíveis

Baixe no formato PDF, TXT ou leia online no Scribd

0 notas0% acharam este documento útil (0 voto)

12 visualizações3 páginasEEG Findings in Dementia With Lewy Bodies and Alzheimer's Disease

Enviado por

Leni Lukmanhmm

Direitos autorais:

© All Rights Reserved

Formatos disponíveis

Baixe no formato PDF, TXT ou leia online no Scribd

Você está na página 1de 3

SHORT REPORT

EEG ndings in dementia with Lewy bodies and

Alzheimers disease

R C G Briel, I G McKeith, W A Barker, Y Hewitt, R H Perry, P G Ince, A F Fairbairn

Abstract

ObjectivesTo evaluate the role of the

EEG in the diagnosis of dementia with

Lewy bodies (DLB).

MethodsStandard EEG recordings from

14 patients with DLB conrmed at post-

mortem were examined and were com-

pared with the records from 11 patients

with Alzheimers disease conrmed at

postmortem

ResultsSeventeen of the total of 19

records from the patients with DLB were

abnormal. Thirteen showed loss of alpha

activity as the dominant rhythm and half

had slow wave transient activity in the tem-

poral lobe areas. This slow wave transient

activity correlated with a clinical history of

loss of consciousness. The patients with

Alzheimers disease were less likely to show

transient slow waves and tended to have

less marked slowing of dominant rhythm.

ConclusionsThe greater slowing of the

EEG in DLB than in Alzheimers disease

may be related to a greater loss of choline

acetyltransferase found in DLB. Temporal

slow wave transients may be a useful diag-

nostic feature in DLB and may help to

explain the transient disturbance of con-

sciousness which is characteristic of the

disorder.

(J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1999;66:401403)

Keywords: electroencephalography, dementia, Lewy

body

Dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) has

recently been described as the second most

common pathological type of dementia, ac-

counting for up to 20% of elderly hospitalised

patients coming to postmortem.

1 2

Many pa-

tients with DLB, however, are probably often

erroneously misdiagnosed as having senile

dementia of Alzheimer type (SDAT) or toxic

delirium.

3

This diYculty in clinical diagnosis

may now be partly overcome given the growing

consensus about clinical diagnostic criteria

4

;

however, their prospective utility and the role

of investigative methods in enhancing accuracy

of clinical diagnosis have yet to be evaluated.

The EEG is often carried out as part of the

clinical assessment of patients with dementia as

a non-invasive, widely available procedure

which is generally well tolerated, even by

patients with cognitive impairment. The EEG

ndings, which may support a diagnosis of

Alzheimers disease are slowing of alpha activ-

ity and an increase in slow frequency activity.

5

These ndings may also diVerentiate dement-

ing disorders from metabolic or toxic confu-

sional states. Findings of EEG previously

reported in a few patients with DLB

611

suggested that in addition to generalised slow-

ing, sharp or triphasic waves may be character-

istic features useful in clinical diagnosis.

There are pragmatic reasons to predict focal

EEG abnormalities of the temporal lobe in

DLB. The predilection sites for neuropatho-

logical change in DLB are in subcortical and

temporal lobe structures and in addition, the

hallucinations and loss of consciousness which

are seen in some cases are often reminiscent of

temporal lobe dysfunction, as seen, for exam-

ple, in temporal lobe epilepsy.

The purpose of this study was to describe the

characteristic EEG ndings in a group of cases

of DLB conrmed by postmortem, specically

looking for evidence of focal abnormalities in the

temporal lobes, or for triphasic or sharp waves,

and to compare these records with those from

cases of SDAT conrmed by postmortem.

Subjects and methods

Fourteen cases of DLB conrmed by postmor-

tem were selected on the basis of the availabil-

ity of EEG records and 11 patients with SDAT

were similarly available for comparison. The

patients, who were aged between 64 and 89 at

the time of EEG, were all from Newcastle hos-

pitals and had died between 1984 and 1991.

Neuropathological diagnosis was made accord-

ing to previously published methods.

12

All of

the patients had been comprehensively as-

sessed in a specialist psychogeriatric unit where

EEGs are carried out on all patients as part of

a routine dementia assessment. Standard EEG

techniques were used.

The EEG records were examined blind to

diagnosis on two occasions by three raters. The

raters knew that the patients had dementia but

had no other clinical details. The EEGs were

assessed on the following criteria: dominant

frequency, presence of other frequencies, left/

right asymmetry, mean amplitude, and pres-

ence of focal abnormalities including spikes,

sharp waves, triphasic waves or transient slow

wave activity.

J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1999;66:401403 401

Institute for the Health

of the Elderly,

Newcastle General

Hospital, Westgate

Road, Newcastle upon

Tyne NE4 6BE, UK

R C G Briel

I G McKeith

R H Perry

P G Ince

A F Fairbairn

Department of

Neuropsychiatry,

Hadrian Clinic,

Newcastle General

Hospital, Newcastle

upon Tyne NE4 6BE,

UK

W A Barker

Department of Clinical

Neurophysiology,

Royal Victoria

Inrmary and

Associated Hospitals

NHS Trust, Queen

Victoria Road,

Newcastle upon Tyne,

UK

Y Hewitt

Correspondence to:

Dr R Briel, Institute for

Health of the Elderly,

Newcastle General Hospital,

Westgate Road, Newcastle

upon Tyne NE4 6BE, UK.

Telephone 0044 191 256

3018; fax 0044 191 273

1156.

Received 6 November 1998

and in nal form

28 August 1998

Accepted 11 September 1998

Case notes were examined using a specially

designed standardised schedule to record spe-

cic clinical features. The duration of illness

was identied as being the time between rst

onset of symptoms, as reported by the care

giver and the date of the EEG, given in

months. The timing of the EEG was also

expressed as a percentage of the total period

from onset to death. It was noted whether the

patients either experienced episodic loss of

consciousness, or hallucinations. A global rat-

ing scale of severity at the time of the EEGs

was made using the clinical dementia rating

(CDR) of Hughes et al

13

(a score of 0 indicates

no dementia, 0.5 indicates possible dementia,

1 indicates mild dementia, 2 indicates moder-

ate dementia, and 3 indicates severe demen-

tia).

Finally, clinical symptoms were examined for

correlations with pathological diagnosis and

EEG ndings. The data were analysed using

the statistical package for the social sciences

(SPSS). When more than one variable was

compared, correlation coeYcients and t values

are given.

Results

The DLBgroup contained seven men and seven

women, the SDAT group ve men and six

women. Individual case details are given in the

table. Three (21%) of the patients with DLB

had been diagnosed as having Parkinsons

disease before developing dementia (Parkinsons

disease+DLB). The two groups were similar in

age distribution (SDAT mean 73.4 (SD 10.21)

years, DLB mean 78.1 (SD 7.24) years).

The DLB group had a slightly shorter dura-

tion of illness at the time of EEG ( DLB mean

20.1 (SD 16.9) months), SDAT mean 31.4

(SD15.6) months (p=0.100). When the timing

of the EEG was expressed as the time of onset

to EEG divided by time of onset to death, the

two groups were similar (DLB mean (SD 25.2)

59.3%, SDAT mean (SD 22.9) 52.9%, Mann

Whitney U = 64 (NS)). The distribution of

CDR scores was similar at the time of EEG

suggesting an equivalent degree of impairment

between the two groups. No patient had a his-

tory suggestive of clinical seizures.

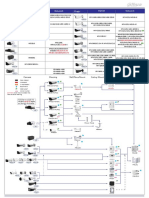

The EEG records of these 25 patients were

examined and are referred to by the case num-

Electroencephalographic and clinical features of patients with dementia with Lewy bodies and senile dementia of Alzheimer type

Case No

Age at

EEG

(y)

Time from onset

of clinical

symptoms to

death (months)

Clinical

dementia

rating Hallucinations

Episodic loss of

consciousness

Time from onset

of clinical

symptoms to date

of EEG recording

(months)

Time of onset

to EEG as %

onset to death

Dominant

activity

Other

frequencies TLSWT

SDAT Patients:

1 80 99 1 No No 60 61 Alpha Beta Theta No

2 76 108 0.5 No No 36 33 Alpha Theta Beta No

3

1

64 96 2 No Yes 47 49 Delta Theta Yes L/R

4 76 19 2 Auditory No 16 84 Alpha Theta

(minimal)

No

5 77 50 1 No No 36 72 Alpha Theta Beta

Delta

No

6 80 54 1 No No 39 72 Alpha/

Theta

Nil No

7 65 21 3 No No 15 71 Delta Theta Alpha Yes

8 92 36 2 Yes, visual No 4 11 Alpha Theta Delta No

9 76 63 2 No No 30 48 Theta Delta Alpha No

10 54 128 1 No No 29 23 Alpha Theta Delta No

11 67 57 2 No No 33 58 Delta Theta Beta No

DLB Patients:

12 85 107 2 No No 17 16 Alpha Theta Delta No

13 82 32 2 Visual Yes 20 63 Alpha Beta Yes L

14 Record 1 84 31 2 Visual Yes 24 77 Theta Delta Beta No

Record 2 Theta Delta No

15

2

84 6 1 No Yes 5 83 polyrhythmic Alpha Theta

Delta

Yes L

16 72 15 0.5 No No 4 27 Theta Beta No

17 Record 1 64 41 1 Visual Yes 24 59 Alpha Delta Theta

beta

Yes L

Record 2 Alpha Beta Theta Yes L/R*

Record 3 Polyrhythmic Delta Theta No

18

3

84 2 2 Visual and

Auditory

No 1 50 Delta Theta No

19 68 20 2 Visual and

Auditory

No 11 55 Alpha Theta Delta Yes L/R

20

4

89 22 1 Visual No 16 73 Theta Delta No

21 79 27 0.5 No Yes 11 41 Theta Nil Yes L/R

22 Record 1 71 32 1 Visual Yes 20 63 Delta Theta Yes L/R

Record 2

5

Delta Theta Yes L

23

6

77 24 2 Visual/olfactory/

gustatory

Yes 23 96 Delta Theta No

24 Record 1 79 70 2 No No 69 99 Alpha Theta Delta No

Record 2 Theta Alpha Yes L

25 76 120 0.5 No No 36 30 Alpha

Theta

Delta No

TLSWT = Temporal lobe slow wave transients.

*Increased in number from record 1.

Sharp waves and other EEG features:

1

Sharp waves on left + right.

2

Left posterior sharp wave.

3

Slow waves anteriorly.

4

Delta dominant anteriorly.

5

Suggestion of sharp + slow wave complex.

6

Sharp wave on left side.

402 Briel, McKeith, Barker, et al

bers in the table. The eleven cases of

Alzheimers disease had a single EEG recorded

for each patient. A total of 19 records from 14

patients in the DLB group were examined,

because three patients had two records each

and one patient had three records. All but

patients 2 and 4 (both SDAT) were clearly

abnormal with alpha activity decreased outside

the normal frequency. Preservation of alpha

activity was more common in SDAT (55%)

than in DLB (36%) (p=0.45). One (9%)

patient with SDAT and seven (50%) patients

with DLB had no remaining alpha activity. Six

(55%) patients with SDAT and 11 (79%) with

DLB had delta components. Overall, this

suggests that patients with DLB show a greater

tendency towards slowing of both dominant

and non-dominant rhythms.

TEMPORAL LOBE SLOW WAVE TRANSIENTS

Temporal lobe slow wave transients were

dened as episodes of delta or theta often asso-

ciated with sharply contoured components but

not strictly fullling the criteria for spikes

(monophasic waves of duration <80 ms) or

sharp waves (duration 80200 ms). They had a

duration <1 second and occurred in the

temporal lobe areas only.

Temporal lobe transients were seen much

more often in patients with DLB (seven out of

14 (50%)) whereas only two (18%) of the

patients with SDAT showed this abnormality

(p=0.11). Nine of the 19 DLB records showed

this abnormality.

There was no signicant correlation between

temporal slow wave transients and either sym-

metry (p=0.57) or alpha dominance (p=0.19).

CORRELATION BETWEEN CLINICAL FEATURES AND

TEMPORAL LOBE SLOW WAVE TRANSIENTS

Temporal lobe slowwave transients were highly

correlated with reported episodes of loss of

consciousness, both in the total group

(p=0.01) and within the DLB group (p=0.05)

whereas hallucinations (p=0.5), duration of ill-

ness (p=0.59), and global severity as measured

by CDR (p=0.51) were not.

Discussion

Electroencephalographic ndings in DLB have

previously been described only for a few cases.

A comprehensive review of the literature found

only 13 descriptions of EEGs in DLB con-

rmed by postmortem.

69 11 14

In this study 19 records from 14 patients

with DLB conrmed by postmortem were

examined. Seventeen of these records were

abnormal. The key ndings were a loss of alpha

activity as the dominant rhythm in 13 of the

records, presence of temporal lobe slow wave

transients in 50% of cases, and a strong corre-

lation between the presence of these temporal

lobe slow wave transients and a clinical history

of loss of consciousness.

Previous reports have commented on this

slowing of dominant rhythm

5 7 11 14

and one

author has described a case in which triphasic

waves were present.

9

Periodic synchronous dis-

charges have been described

8

as have the pres-

ence of sharp waves.

6 7

No evidence of triphasic waves was found in

the records examined, suggesting that this is

not a frequent nding in DLB. Only two of the

cases described here (5 and 19) had frontal

slowing. No cases showed periodic synchro-

nous discharges. Two patients with DLB in this

study did had denite sharp waves, in addition

to which patient 18 had a single sharp wave,

which was not included in the analysis as it was

unlikely to have been regarded as relevant in

clinical practice.

Episodic loss of consciousness in now

considered a supportive feature of DLB in the

consensus criteria. The nature of these epi-

sodes of loss of consciousness is not clear. Pro-

posed mechanisms

14

include gait and balance

disorder, autonomic instability including pos-

tural hypotension, or an epileptic phenom-

enon. The nding in this paper of a relation

between temporal lobe slow wave activity and a

clinical history of loss of consciousness is

indicative of a primary cerebral dysfunction.

This study is largely a descriptive account of

the major EEG ndings in DLB. The next step

in this work should involve prospective serial

EEG examinations from clinically diagnosed

patients with DLB followed up to postmortem,

with a larger group of patients with SDAT for

comparison. An alternative and complimen-

tary approach would be to investigate the role

of quantitative EEG analysis in DLB.

We thank Yvonne Wilkin for her help in obtaining EEG records

and Maureen Middlemist for typing the manuscript.

1 Perry RH, Irving D, Blessed G, et al. Clinically and

pathologically distinct form of dementia in the elderly.

Lancet 1989;166.

2 Lennox G, Lowe J, Landon M, et al. DiVuse Lewy body

disease: correlative neuropathology using anti-ubiquitin

immunocytochemistry. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1989;

52:123647.

3 McKeith IG, Fairbairn AF, Perry RH, et al. The clinical

diagnosis and misdiagnosis of senile dementia of Lewy

body type (SDLT) - do the diagnostic systems for demen-

tia need to be revised? Br J Psychol 1994;305:32432.

4 McKeith IG, Galasko D, Kosaka K, et al. Consensus guide-

lines for the clinical and pathological diagnosis of dementia

with Lewy bodies (DLB). Neurology 1996;47:111324.

5 Soininen H, Reikkinen PJ. EEG in diagnostics and

follow-up of Alzheimers disease. Acta Neurol Scand

1992;(suppl 139):369.

6 Crystal HA, Dickson DW, Lizardi JE, et al. Antemortem

diagnosis of diVuse Lewy body disease. Neurology 1990;40:

15238.

7 Gibb WR, Luthert PJ, Janota I, et al. Cortical Lewy body

dementia: clinical features and classication. J Neurol Neu-

rosurg Psychiatry 1989;52:18592.

8 Yamamoto T, Imai T. A case of diVuse Lewy body and

Alzheimers diseases with periodic synchronous discharges.

J Neuropathol Exp Neurology 1988;47:53648.

9 Byrne EJ, Lennox G, Lowe J, et al. DiVuse Lewy body

disease: clinical features in 15 cases. J Neurol Neurosurg

Psychiatry 1989;52:70917.

10 Byrne EJ, Lowe J, Godwin-Austin RB, et al. Dementia and

Parkinsons disease associated with diVuse cortical Lewy

bodies. Lancet 1987;i:501.

11 Hely MA, Reid WGJ, Halliday GM, et al. DiVuse Lewy body

disease: clinical features in nine cases without coexistent AD.

J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1996;60:5318.

12 Perry RH, Irving D, Blessed G, et al. Senile dementia of

Lewy body type: a clinically and neuropathologically

distinct form of Lewy body dementia in the elderly. J Neu-

rol Sci 1990;95:11939.

13 Hughes PH, Berg L, Danziger WL, et al. A new clinical scale

for the staging of dementia. Br J Psychol 1982;140:56672.

14 McKeith IG, Perry RH, Fairbairn AF, et al. Operational cri-

teria for senile dementia of Lewy body type (DLB). Psychol

Med 1992;22:91122.

EEG ndings in dementia with Lewy bodies and Alzheimers disease 403

Você também pode gostar

- Non-Alzheimer's and Atypical DementiaNo EverandNon-Alzheimer's and Atypical DementiaMichael D. GeschwindNota: 5 de 5 estrelas5/5 (1)

- Clinical and Imaging Correlates of EEG Patterns in Hospitalized Patients With EncephalopathyDocumento12 páginasClinical and Imaging Correlates of EEG Patterns in Hospitalized Patients With EncephalopathyPallab Kanti RoyAinda não há avaliações

- EEG in Dementia and EncephalopathyDocumento19 páginasEEG in Dementia and EncephalopathyDumitruAuraAinda não há avaliações

- Ene 12372Documento7 páginasEne 12372Andres Rojas JerezAinda não há avaliações

- Neuropsiquiatria: Pet Y Spect: Revista Chilena de Radiología. Vol. 8 #2, Año 2002Documento7 páginasNeuropsiquiatria: Pet Y Spect: Revista Chilena de Radiología. Vol. 8 #2, Año 2002pau_sebAinda não há avaliações

- Hossein If Ard 2013Documento7 páginasHossein If Ard 2013Abhishek ParasharAinda não há avaliações

- Neuropsiquiatria Pet y Spect PDFDocumento7 páginasNeuropsiquiatria Pet y Spect PDFidrilparadiseAinda não há avaliações

- History Syndrome: Natural of Down'sDocumento5 páginasHistory Syndrome: Natural of Down'sfara asifaAinda não há avaliações

- Hyperperfusion in The Thalamus On Arterial Spin Labelling Indicates Non-Convulsive Status Epilepticus - 2020Documento16 páginasHyperperfusion in The Thalamus On Arterial Spin Labelling Indicates Non-Convulsive Status Epilepticus - 2020Reny Wane Vieira dos SantosAinda não há avaliações

- Roberts Psychiatric 1992Documento3 páginasRoberts Psychiatric 1992Drashua AshuaAinda não há avaliações

- Utility of N Terminal Pro Brain Natriuretic Peptide in Elderly PatientsDocumento4 páginasUtility of N Terminal Pro Brain Natriuretic Peptide in Elderly PatientssufaAinda não há avaliações

- Convulsiones Recurrentes en Pacientes Con DemenciaDocumento3 páginasConvulsiones Recurrentes en Pacientes Con DemenciaHumberto1988Ainda não há avaliações

- Differentiating Alzheimer's Disease - LewyDocumento9 páginasDifferentiating Alzheimer's Disease - LewyIcaroAinda não há avaliações

- Cerebral SLE Case Report and Diagnostic Test EvaluationDocumento9 páginasCerebral SLE Case Report and Diagnostic Test EvaluationrandyardinalAinda não há avaliações

- Alzheimer's Disease, and Apolipoprotein E - (Epsilon) 4/4 Genotype Decreased Melatonin Levels in Postmortem Cerebrospinal Fluid in Relation To AgingDocumento6 páginasAlzheimer's Disease, and Apolipoprotein E - (Epsilon) 4/4 Genotype Decreased Melatonin Levels in Postmortem Cerebrospinal Fluid in Relation To AgingLonkesAinda não há avaliações

- Posterior Reversible Encephalopathy Syndrome (PRES) : Electroencephalographic Findings and Seizure PatternsDocumento7 páginasPosterior Reversible Encephalopathy Syndrome (PRES) : Electroencephalographic Findings and Seizure PatternsJasper CubiasAinda não há avaliações

- Journal Late - NC DementiaDocumento25 páginasJournal Late - NC DementiaOYEYEMI AFOLABIAinda não há avaliações

- Interpretación Del EEG en Estupor y Coma.Documento14 páginasInterpretación Del EEG en Estupor y Coma.DrGonsal8519Ainda não há avaliações

- Ehara 1997Documento9 páginasEhara 1997jahfdfgsdjad asdhsajhajdkAinda não há avaliações

- Cidp Nejm PDFDocumento14 páginasCidp Nejm PDFFebrianaAinda não há avaliações

- Phi RythmDocumento6 páginasPhi RythmStanley IgweAinda não há avaliações

- Misdiagnosis and Treatment Delays in Juvenile Myoclonic EpilepsyDocumento4 páginasMisdiagnosis and Treatment Delays in Juvenile Myoclonic EpilepsyPutu Filla JfAinda não há avaliações

- Schmitt 2012Documento8 páginasSchmitt 2012nurdiansyahAinda não há avaliações

- Importance of Long-Term EEG in Seizure-Free PatienDocumento5 páginasImportance of Long-Term EEG in Seizure-Free PatienChu Thị NghiệpAinda não há avaliações

- Alteraciones Neuropsicológicas en La Esclerosis Lateral Amiotrófica - No Existen o No Se Detectan PDFDocumento6 páginasAlteraciones Neuropsicológicas en La Esclerosis Lateral Amiotrófica - No Existen o No Se Detectan PDFsandraAinda não há avaliações

- Correlation Between Clinical Stages and EEG Findings in SSPEDocumento6 páginasCorrelation Between Clinical Stages and EEG Findings in SSPEKota AnuroopAinda não há avaliações

- POLG1 Mutations Cause A Syndromic Epilepsy With Occipital Lobe PredilectionDocumento11 páginasPOLG1 Mutations Cause A Syndromic Epilepsy With Occipital Lobe Predilectionn.parthasarathyAinda não há avaliações

- Rett CriteriaDocumento7 páginasRett CriteriaAlina AndreiAinda não há avaliações

- Entropy 18 00008Documento17 páginasEntropy 18 00008Sergio TalegónAinda não há avaliações

- J Clinph 2013 03 031Documento7 páginasJ Clinph 2013 03 031Andres Rojas JerezAinda não há avaliações

- Plasma Glutamate Levels Higher in ALS PatientsDocumento5 páginasPlasma Glutamate Levels Higher in ALS PatientsLiemAinda não há avaliações

- Syncope Vs Seizure - A Tawakul 07 14 10Documento31 páginasSyncope Vs Seizure - A Tawakul 07 14 10akanksha nagarAinda não há avaliações

- Eeg Rett SyndromeDocumento8 páginasEeg Rett SyndromeBagus Ngurah MahasenaAinda não há avaliações

- Clinical Factors Ischaemic Stroke: Associated With Dementia inDocumento5 páginasClinical Factors Ischaemic Stroke: Associated With Dementia inarif 2006Ainda não há avaliações

- Accepted Manuscript: SeizureDocumento21 páginasAccepted Manuscript: SeizureAhmad Harissul IbadAinda não há avaliações

- FTPDocumento325 páginasFTPKim Chwin KhyeAinda não há avaliações

- Pleds 2009 JamaDocumento7 páginasPleds 2009 JamaRosiane Da Silva FontanaAinda não há avaliações

- Autonomic Dysfunction in Guillain-Barre Syndrome: and Baroreflex Sensitivity, (3) 100/min and AbnormalDocumento8 páginasAutonomic Dysfunction in Guillain-Barre Syndrome: and Baroreflex Sensitivity, (3) 100/min and Abnormalsrajan sahuAinda não há avaliações

- Bf30ea Analysis of Electroencephalograms in Alzheimers DDocumento16 páginasBf30ea Analysis of Electroencephalograms in Alzheimers DtourfrikiAinda não há avaliações

- PLED Aetiology and Association with EEG SeizuresDocumento2 páginasPLED Aetiology and Association with EEG SeizuresChandra DarusmanAinda não há avaliações

- Early-Onset Alzheimer - S Disease May Be Associated With Sortilin-Related Receptor 1 Gene Mutation - A Family Report and ReviewDocumento5 páginasEarly-Onset Alzheimer - S Disease May Be Associated With Sortilin-Related Receptor 1 Gene Mutation - A Family Report and Reviewhaiqal muzzakirAinda não há avaliações

- Use of Electroencephalography (EEG) in The Management of Seizure DisordersDocumento62 páginasUse of Electroencephalography (EEG) in The Management of Seizure DisordersSai ManojAinda não há avaliações

- Lennox Gastaut SyndromeDocumento12 páginasLennox Gastaut SyndromedulcejuvennyAinda não há avaliações

- Jur DingDocumento7 páginasJur DingRegina CaeciliaAinda não há avaliações

- Making DX PT With BlackoutDocumento12 páginasMaking DX PT With Blackoutidno1008Ainda não há avaliações

- 472 1466 1 PB - 2Documento6 páginas472 1466 1 PB - 2Nazlia LarashitaAinda não há avaliações

- 62-Year-Old Farmer with Progressive Limb WeaknessDocumento48 páginas62-Year-Old Farmer with Progressive Limb WeaknessSamapriya Pasan HewawasamAinda não há avaliações

- 4 November 2004 DR - Supparearg DisayabutrDocumento38 páginas4 November 2004 DR - Supparearg DisayabutrDonnaya KrajangwittayaAinda não há avaliações

- American Academy of Neurology Key PointsDocumento193 páginasAmerican Academy of Neurology Key Pointszayat13Ainda não há avaliações

- Assessment of Palpitation Complaints Benign Paroxysmal Positional VertigoDocumento6 páginasAssessment of Palpitation Complaints Benign Paroxysmal Positional VertigoHappy PramandaAinda não há avaliações

- Eeg MigraineDocumento20 páginasEeg MigraineAkhmad AfriantoAinda não há avaliações

- Clinical of Todd's Paralysis: FeaturesDocumento3 páginasClinical of Todd's Paralysis: FeaturesJeanna SalimaAinda não há avaliações

- tmpC377 TMPDocumento3 páginastmpC377 TMPFrontiersAinda não há avaliações

- Visual Evoked Potentials in Guillain-Barré Syndrome: MethodsDocumento6 páginasVisual Evoked Potentials in Guillain-Barré Syndrome: MethodsYulianti PurnamasariAinda não há avaliações

- Miyagawa Et Al-2015-Human Genome VariationDocumento4 páginasMiyagawa Et Al-2015-Human Genome Variationece142Ainda não há avaliações

- Leitinger 2016Documento9 páginasLeitinger 2016succa07Ainda não há avaliações

- DementiaDocumento60 páginasDementiaRuaa HdeibAinda não há avaliações

- Jurnal AE 2Documento3 páginasJurnal AE 2Mira Mariana UlfahAinda não há avaliações

- Annals of Neurology - 2023 - Mesulam - Frontotemporal Degeneration With Transactive Response DNA Binding Protein Type C atDocumento12 páginasAnnals of Neurology - 2023 - Mesulam - Frontotemporal Degeneration With Transactive Response DNA Binding Protein Type C atLucia BrignoniAinda não há avaliações

- 04 - Differences in Quantitative EEG Between Frontotemporal Dementia and Alzheimer's Disease - GOODDocumento8 páginas04 - Differences in Quantitative EEG Between Frontotemporal Dementia and Alzheimer's Disease - GOODheineken2012Ainda não há avaliações

- Cachexia in Cancer Patient PDFDocumento6 páginasCachexia in Cancer Patient PDFLeni LukmanAinda não há avaliações

- Instruction Manual For The ILAE 2017Documento12 páginasInstruction Manual For The ILAE 2017Prabaningrum DwidjoasmoroAinda não há avaliações

- Cachexia in Cancer PatientDocumento6 páginasCachexia in Cancer PatientLeni LukmanAinda não há avaliações

- Effect of Phototherapy With Alumunium Foil Reflectors On Neonatal HyperbilirubinemiaDocumento5 páginasEffect of Phototherapy With Alumunium Foil Reflectors On Neonatal HyperbilirubinemiaBunga Tri AmandaAinda não há avaliações

- HypospadiaDocumento18 páginasHypospadiaLeni LukmanAinda não há avaliações

- Fitness of BabyDocumento7 páginasFitness of BabyLeni LukmanAinda não há avaliações

- Adjustment Disorder 4Documento13 páginasAdjustment Disorder 4Anonymous Af24L7Ainda não há avaliações

- Pediatrics 2013 Klein Peds.2012 3836Documento9 páginasPediatrics 2013 Klein Peds.2012 3836Leni LukmanAinda não há avaliações

- Protocol 3Documento46 páginasProtocol 3Leni LukmanAinda não há avaliações

- Free CV TemplateDocumento2 páginasFree CV TemplatemegaAinda não há avaliações

- Volume40 Number1 Fall2014-Article5Documento9 páginasVolume40 Number1 Fall2014-Article5Leni LukmanAinda não há avaliações

- SplintingDocumento7 páginasSplintingLeni LukmanAinda não há avaliações

- Hypospadia UpdateDocumento7 páginasHypospadia UpdateLeni LukmanAinda não há avaliações

- Pi Is 0161642009014523Documento2 páginasPi Is 0161642009014523Leni LukmanAinda não há avaliações

- 12-Narang 176141122Documento3 páginas12-Narang 176141122Leni LukmanAinda não há avaliações

- Help Pedsurgeryafrica94Documento13 páginasHelp Pedsurgeryafrica94Leni LukmanAinda não há avaliações

- EMBRYOLOGY - The External Genitalia in The Two Sexes Develop From Common Anlagen (Genital TubercleDocumento2 páginasEMBRYOLOGY - The External Genitalia in The Two Sexes Develop From Common Anlagen (Genital TubercleLeni LukmanAinda não há avaliações

- HypospadiasDocumento12 páginasHypospadiasLeni LukmanAinda não há avaliações

- Vancouver Style PDFDocumento25 páginasVancouver Style PDFwewwewAinda não há avaliações

- Sony HCD-GTX999 PDFDocumento86 páginasSony HCD-GTX999 PDFMarcosAlves100% (1)

- Screenshot 2023-01-03 at 9.25.34 AM PDFDocumento109 páginasScreenshot 2023-01-03 at 9.25.34 AM PDFAzri ZakwanAinda não há avaliações

- Pemanfaatan Limbah Spanduk Plastik (Flexy Banner) Menjadi Produk Dekorasi RuanganDocumento6 páginasPemanfaatan Limbah Spanduk Plastik (Flexy Banner) Menjadi Produk Dekorasi RuanganErvan Maulana IlyasAinda não há avaliações

- Tennis BiomechanicsDocumento14 páginasTennis BiomechanicsΒασίλης Παπατσάς100% (1)

- Ca2Documento8 páginasCa2ChandraAinda não há avaliações

- BELL B40C - 872071-01 Section 2 EngineDocumento38 páginasBELL B40C - 872071-01 Section 2 EngineALI AKBAR100% (1)

- Fendering For Tugs: Mike Harrison, Trelleborg Marine Systems, UKDocumento5 páginasFendering For Tugs: Mike Harrison, Trelleborg Marine Systems, UKRizal RachmanAinda não há avaliações

- Lesson 1 - Simple StressDocumento5 páginasLesson 1 - Simple StressJohn Philip NadalAinda não há avaliações

- Cutter Wheel - H1140Documento4 páginasCutter Wheel - H1140Sebastián Fernando Canul Mendez100% (2)

- Dahua Pfa130 e Korisnicko Uputstvo EngleskiDocumento5 páginasDahua Pfa130 e Korisnicko Uputstvo EngleskiSaša CucakAinda não há avaliações

- Abb 60 PVS-TLDocumento4 páginasAbb 60 PVS-TLNelson Jesus Calva HernandezAinda não há avaliações

- Three Bucket Method & Food ServiceDocumento4 páginasThree Bucket Method & Food Servicerose zandrea demasisAinda não há avaliações

- Nitocote WP DDocumento4 páginasNitocote WP DdaragAinda não há avaliações

- UPSC IFS Botany Syllabus: Paper - IDocumento3 páginasUPSC IFS Botany Syllabus: Paper - IVikram Singh ChauhanAinda não há avaliações

- Abiotic and Biotic Factors DFDocumento2 páginasAbiotic and Biotic Factors DFgiselleAinda não há avaliações

- College of Medicine & Health SciencesDocumento56 páginasCollege of Medicine & Health SciencesMebratu DemessAinda não há avaliações

- r05320202 Microprocessors and Micro ControllersDocumento7 páginasr05320202 Microprocessors and Micro ControllersSri LalithaAinda não há avaliações

- Ebrosur Silk Town PDFDocumento28 páginasEbrosur Silk Town PDFDausAinda não há avaliações

- Semen RetentionDocumento3 páginasSemen RetentionMattAinda não há avaliações

- SAMMAJIVA - VOLUME 1, NO. 3, September 2023 Hal 235-250Documento16 páginasSAMMAJIVA - VOLUME 1, NO. 3, September 2023 Hal 235-250Nur Zein IzdiharAinda não há avaliações

- Exercise Stress TestingDocumento54 páginasExercise Stress TestingSaranya R S100% (2)

- Sanchez 07 Poles and Zeros of Transfer FunctionsDocumento20 páginasSanchez 07 Poles and Zeros of Transfer FunctionsYasmin KayeAinda não há avaliações

- AS 1418.2 Cranes, Hoists and Winches Part 2 Serial Hoists and WinchesDocumento31 páginasAS 1418.2 Cranes, Hoists and Winches Part 2 Serial Hoists and WinchesDuy PhướcAinda não há avaliações

- Director's Report Highlights Record Wheat Production in IndiaDocumento80 páginasDirector's Report Highlights Record Wheat Production in Indiakamlesh tiwariAinda não há avaliações

- DCI-2 Brief Spec-Rev01Documento1 páginaDCI-2 Brief Spec-Rev01jack allenAinda não há avaliações

- GT ĐỀ 04Documento39 páginasGT ĐỀ 04Cao Đức HuyAinda não há avaliações

- Porta by AmbarrukmoDocumento4 páginasPorta by AmbarrukmoRika AyuAinda não há avaliações

- Heradesign Brochure 2008Documento72 páginasHeradesign Brochure 2008Surinder SinghAinda não há avaliações

- Computational Kinematics Assignment 2021Documento2 páginasComputational Kinematics Assignment 2021Simple FutureAinda não há avaliações

- Ch3 XII SolutionsDocumento12 páginasCh3 XII SolutionsSaish NaikAinda não há avaliações

- LIT: Life Ignition Tools: Use Nature's Playbook to Energize Your Brain, Spark Ideas, and Ignite ActionNo EverandLIT: Life Ignition Tools: Use Nature's Playbook to Energize Your Brain, Spark Ideas, and Ignite ActionNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (402)

- The Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityNo EverandThe Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (13)

- Why We Die: The New Science of Aging and the Quest for ImmortalityNo EverandWhy We Die: The New Science of Aging and the Quest for ImmortalityNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2)

- The Ritual Effect: From Habit to Ritual, Harness the Surprising Power of Everyday ActionsNo EverandThe Ritual Effect: From Habit to Ritual, Harness the Surprising Power of Everyday ActionsNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (3)

- Think This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeNo EverandThink This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeAinda não há avaliações

- Summary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedNo EverandSummary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedNota: 5 de 5 estrelas5/5 (78)

- The Obesity Code: Unlocking the Secrets of Weight LossNo EverandThe Obesity Code: Unlocking the Secrets of Weight LossNota: 5 de 5 estrelas5/5 (3)

- Raising Good Humans: A Mindful Guide to Breaking the Cycle of Reactive Parenting and Raising Kind, Confident KidsNo EverandRaising Good Humans: A Mindful Guide to Breaking the Cycle of Reactive Parenting and Raising Kind, Confident KidsNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (169)

- Raising Mentally Strong Kids: How to Combine the Power of Neuroscience with Love and Logic to Grow Confident, Kind, Responsible, and Resilient Children and Young AdultsNo EverandRaising Mentally Strong Kids: How to Combine the Power of Neuroscience with Love and Logic to Grow Confident, Kind, Responsible, and Resilient Children and Young AdultsAinda não há avaliações

- Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisNo EverandOutlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1)

- Techniques Exercises And Tricks For Memory ImprovementNo EverandTechniques Exercises And Tricks For Memory ImprovementNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (40)

- Daniel Kahneman's "Thinking Fast and Slow": A Macat AnalysisNo EverandDaniel Kahneman's "Thinking Fast and Slow": A Macat AnalysisNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (130)

- The Ultimate Guide To Memory Improvement TechniquesNo EverandThe Ultimate Guide To Memory Improvement TechniquesNota: 5 de 5 estrelas5/5 (34)

- Roxane Gay & Everand Originals: My Year of Psychedelics: Lessons on Better LivingNo EverandRoxane Gay & Everand Originals: My Year of Psychedelics: Lessons on Better LivingNota: 5 de 5 estrelas5/5 (4)

- Mindset by Carol S. Dweck - Book Summary: The New Psychology of SuccessNo EverandMindset by Carol S. Dweck - Book Summary: The New Psychology of SuccessNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (327)

- Troubled: A Memoir of Foster Care, Family, and Social ClassNo EverandTroubled: A Memoir of Foster Care, Family, and Social ClassNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (22)

- The Happiness Trap: How to Stop Struggling and Start LivingNo EverandThe Happiness Trap: How to Stop Struggling and Start LivingNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1)

- Roxane Gay & Everand Originals: My Year of Psychedelics: Lessons on Better LivingNo EverandRoxane Gay & Everand Originals: My Year of Psychedelics: Lessons on Better LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (31)

- The Body Keeps the Score by Bessel Van der Kolk, M.D. - Book Summary: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of TraumaNo EverandThe Body Keeps the Score by Bessel Van der Kolk, M.D. - Book Summary: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of TraumaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (266)

- The Garden Within: Where the War with Your Emotions Ends and Your Most Powerful Life BeginsNo EverandThe Garden Within: Where the War with Your Emotions Ends and Your Most Powerful Life BeginsAinda não há avaliações

- Dark Psychology & Manipulation: Discover How To Analyze People and Master Human Behaviour Using Emotional Influence Techniques, Body Language Secrets, Covert NLP, Speed Reading, and Hypnosis.No EverandDark Psychology & Manipulation: Discover How To Analyze People and Master Human Behaviour Using Emotional Influence Techniques, Body Language Secrets, Covert NLP, Speed Reading, and Hypnosis.Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (110)

- The Courage Habit: How to Accept Your Fears, Release the Past, and Live Your Courageous LifeNo EverandThe Courage Habit: How to Accept Your Fears, Release the Past, and Live Your Courageous LifeNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (253)

- Summary: It Didn't Start with You: How Inherited Family Trauma Shapes Who We Are and How to End the Cycle By Mark Wolynn: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisNo EverandSummary: It Didn't Start with You: How Inherited Family Trauma Shapes Who We Are and How to End the Cycle By Mark Wolynn: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisNota: 5 de 5 estrelas5/5 (3)