Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Detecting Fraud

Enviado por

hueyna0 notas0% acharam este documento útil (0 voto)

48 visualizações7 páginasDetecting fraud: what are auditors' responsibilities?

written by Gin Chong

Direitos autorais

© © All Rights Reserved

Formatos disponíveis

PDF, TXT ou leia online no Scribd

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDetecting fraud: what are auditors' responsibilities?

written by Gin Chong

Direitos autorais:

© All Rights Reserved

Formatos disponíveis

Baixe no formato PDF, TXT ou leia online no Scribd

0 notas0% acharam este documento útil (0 voto)

48 visualizações7 páginasDetecting Fraud

Enviado por

hueynaDetecting fraud: what are auditors' responsibilities?

written by Gin Chong

Direitos autorais:

© All Rights Reserved

Formatos disponíveis

Baixe no formato PDF, TXT ou leia online no Scribd

Você está na página 1de 7

47

2013 Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

Published online in Wiley Online Library (wileyonlinelibrary.com).

DOI 10.1002/jcaf.21829

f e

a

t

u

r

e

a

r

t

i

c

l

e

Gin Chong

I

n 2010, the Asso-

ciation of Certified

Fraud Examiners

(ACFE) estimated

that the IRS has lost

US$994 billion due to

fraud, and a whopping

US$2.9 trillion world-

wide was lost due to

fraudulent financial

statements, asset mis-

appropriation, and

corruption. The fraud-

related losses represent

approximately 7% of

the U.S. gross domes-

tic product (ACFE, 2008; ACFE,

2010). Based on the U.S. fiscal

year 2008 budget, losses result-

ing from fraud have exceeded

the combined net costs of the

Departments of Defense, Home-

land Security, Transportation, and

Education. Fraud is costly and

damages the reputation and cred-

ibility of the audit profession.

Stakeholders are pressuring audi-

tors to include detection of fraud

in the audit programs and audit

reports. In an effort to restore

public trust, accounting standard

setters, including the Public

Company Accounting Oversight

Board (PCAOB), require auditors

to adhere to the requirements of

Statement on Auditing Standards

(SAS) No. 99, Consideration of

Fraud in a Financial Statement

Audit (PCAOB, 2007).

The Standard requires audi-

tors to participate in brainstorm-

ing sessions and to consider

the possibility that a material

misstatement due to fraud could

be present (American Institute

of Certified Public Accoun-

tants [AICPA], 2002). Though

the PCAOB inspection reports

constantly paint disappointing

pictures, the findings are surpris-

ing. Financial statement auditors

are not fraud examiners, but

are to determine the

reliability of internal

control and the extent

of audit risk, and to

report whether the

financial statements

are presented fairly

in accordance with

generally accepted

accounting prin-

ciples (GAAP). Fraud

detections require

unique skill sets and

the development of

forensic techniques.

Specifically, individu-

als need to apply investigative

and analytical skills to gather

and evaluate audit evidence, to

interview all parties relating to

an alleged fraud situation, and to

serve as an expert witness. All

these involve resources in terms

of time, money, and, in many

cases, personal risk of being

persecuted even before a case

begins. But requiring auditors to

be aware of the possibility that

fraud may exist is not enough.

Waves of fraud emerge despite

professional bodies and standard

setters that formulate various

auditing standards as a response,

to restore public trust, and act

Detecting Fraud: What Are Auditors

Responsibilities?

High-profile fraud cases have continued to make

the news over the past few years. But exactly what

are auditors responsibilities when it comes to

detecting fraud? The author of this article reveals

that the auditing profession has come full circle

from being responsible to not being responsible for

detecting fraud. But the volume and critical nature

of fraud cases remain high, as do the number

of auditing standards addressing this issue. The

author explores this problem in depth, identifies

situations where fraud may take place, and sug-

gests various tools that auditors should use for

fraud detection. 2013 Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

48 The Journal of Corporate Accounting & Finance / January/February 2013

DOI 10.1002/jcaf 2013 Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

Audit firms responded by limit-

ing audit hours in an engagement

and reducing time and resources

on searching for fraud.

By the mid-1980s, the vol-

ume and dollar amounts involved

in fraud cases had increased

tremendously, making SAS No.

16 a redundant guideline. A

new wave of public concerns

and outcries forced Congress to

form the Treadway Commission.

The Commission was charged to

identify causal factors that lead

to fraudulent financial report-

ing and to recommend steps to

reduce its incidence. The Com-

mission concluded that at least

36% of the cases involved audi-

tors failure to recognize, or to

view with sufficient skepticism,

certain fraud-related warning

signs or red flags that would

have been noted had the audi-

tors been more diligent in their

audits. In response to the report,

the Accounting Standards Board

(ASB) issued nine statements of

auditing standards (SASs 53 61)

in 1988 to outline external audi-

tors role on fraud prevention and

detection and the potential illegal

activities of audit clients. Audi-

tors are required to apply pro-

fessional skepticism to assume

management is neither honest

nor dishonest (PCAOB, 1993).

Despite all these efforts,

there is no obvious decrease in

audit failures of fraud detection.

The Public Oversight Board

(POB) recognized that these new

SASs seemed to be having little

impact, as the auditors neither

consistently complied with these

standards nor applied the proper

degree of professional skepti-

cism to detect fraud (PCAOB,

2004). There was a widespread

public belief that while audi-

tors have a responsibility to

detect fraud, they were neither

willing nor capable of doing

so. Mounting criticisms of the

Examination of Financial State-

ments, in 1960. Although SAP

No. 30 acknowledged that audi-

tors should be aware of the pos-

sibility that fraud may exist dur-

ing an audit, it was so negatively

stated that auditors felt little or

no obligation to detect fraud.

The Equity Funding scandal

was the next major audit fail-

ure of fraud detection

2

(Seidler,

Andrews, and Epstein, 1977).

In response to the congressional

inquiry, the AICPA formed the

Cohen Commission to reexam-

ine auditors responsibility to

detect fraud. The Commission

recognized that while auditors

should actively consider the

potential for fraud, the inherent

limitations in an audit process

dampen auditors responsibility

for detecting all material frauds.

Specifically, the Commission

recognized that it is challeng-

ing for auditors to detect frauds

that are concealed and derived

from forgery or collusion by

members of management. In

response to Cohens report, the

AICPA issued SAS No. 16, The

Independent Auditors Responsi-

bility for the Detection of Errors

or Irregularities, to implicitly

acknowledge that auditors are

responsible for using a list of

red flags to detect fraud.

In the 1970s, the Department

of Justice and the Federal Trade

Commission (FTC) required pro-

fessional organizations including

the AICPA to eliminate elements

of their codes of professional

behavior that the government

deemed to violate federal anti-

trust statues. For example, the

codes had allowed audit firms to

engage in unrestricted advertis-

ing. The FTC also imposed a

ban on contingent fees and com-

missions for nonaudit clients.

Banning competitive bidding for

audit services has narrowed audit

firms profit margins on audits.

as reminders of their duties of

care. These reminders primarily

serve a symbolic function, but in

fact, the failure in fraud detec-

tion is due to differences in skill

sets and task objectives between

financial statement audits and

fraud detections.

HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE

With the passage of time,

auditors responsibility for

fraud detection has changed

dramatically. Prior to the 1500s,

the British auditing objectives

that centered on the discovery of

defalcations became the basis of

the American auditing approach.

The emphasis on fraud detection

gradually dissipated during

the period of the 1930s until

the infamous McKesson and

Robbins scandal in late 1938.

1

McKesson and Robbinss auditor,

Price Waterhouse & Company,

was under intense scrutiny for

its inability to detect and prevent

the massive accounting fraud. In

the aftermath of the McKesson

and Robbins scandal, audi-

tors were required to perform

additional audit procedures on

accounts receivable and inven-

tories while the audit profession

formulated Statement of Audit-

ing Procedures (SAP) No. 1,

Extension of Auditing Procedure

(AICPA, 1939) to shift auditors

focus away from fraud detection.

Instead, the focus became deter-

mining fairness of the financial

statements in accordance with

the accounting standards. Subse-

quent to SAP No. 1, the auditing

profession came under mounting

pressure from the public and the

Securities and Exchange Com-

mission (SEC) to clarify audi-

tors responsibility with respect

to fraud detection. As a result,

the AICPA issued SAP No. 30,

Responsibilities and Functions

of the Independent Auditor in the

The Journal of Corporate Accounting & Finance / January/February 2013 49

2013 Wiley Periodicals, Inc. DOI 10.1002/jcaf

FRAUD TRIANGLE

Both SAS No. 99 and ISA

240 identify three conditions

that generally present mate-

rial misstatements due to fraud

risk: (a) incentives/pressures,

(b) opportunities, and (c) atti-

tudes/rationalizations. Incentives

or pressure may arise due to

external conditions like eco-

nomic, industry, or entity operat-

ing conditions that threaten the

financial stability or profitability

of the client. Or management

may be under excessive pressure

to perform and meet the require-

ments or expectations of the

firms own sales or profitability

targets, or to meet the expecta-

tions of external parties, includ-

ing lenders, analysts, and stock-

holders. Opportunities for fraud

also arise due to inherent risk

within the industry. The nature or

complexity of the entitys opera-

tions also provides opportunities

to engage in fraudulent financial

reporting. This is exacerbated by

poor internal control systemsin

particular, ineffective accounting

and control of information sys-

temsa dominating management

style, and lack of segregation of

duties among the employees.

Attitudes of or rationaliza-

tions by board members, manage-

ment, or employees arise due to

many factors. They include a lack

of communication or ineffective

management communication;

ineffective implementation, sup-

port, or enforcement of the enti-

tys values or ethical standards;

nonfinancial managements

excessive participation in or pre-

occupation with the selection of

accounting policies or the deter-

mination of significant estimates;

a known history of violations of

securities laws or other laws and

regulations; excessive manage-

ment interest in maintaining or

increasing the entitys stock price

fraud. These procedures include

conducting surprise inventory

or cash counts and performing

substantive tests on potential

fraud risk areas. However, the

watchdogs failed to meet these

requirements and faced the con-

sequences of the Enron fiasco

and the demise of Arthur Ander-

sen. To restore public confidence

and to limit the auditors respon-

sibilities on fraud detection,

Congress passed the Sarbanes-

Oxley Act (SOX) and created

the PCAOB. Though the PCAOB

does not require the auditors to

detect fraud, it requires exter-

nal auditors to report specific

situations and events relating

to fraud and illegal acts to the

clients audit committee as well

as to the authorized authorities.

These authorized authorities

include relevant government

agencies like the IRS, fraud

investigators, and federal and

state governments. As the exter-

nal pressure mounted, the Inter-

national Auditing and Assur-

ance Standards Board issued

the International Standard on

Auditing (ISA) 240, The Audi-

tors Responsibilities Relating

to Fraud in an Audit of Finan-

cial Statements, in December

2009, stating that management

is responsible for detecting

fraud while the auditors are not.

This is in line with an auditors

objective: to conduct an audit in

accordance with ISAs to obtain

reasonable assurance that the

financial statements taken as

a whole are free from material

misstatement, whether caused

by fraud or error. Owing to the

inherent limitations of an audit,

there is an unavoidable risk that

some material misstatements

of the financial statements may

not be detected, even though the

audit is properly planned and

performed in accordance with

the ISAs.

audit profession over its failure

of fraud detection prompted the

POB to propose a number of rec-

ommendations to improve audi-

tors willingness to detect fraud.

The AICPA supported the POBs

recommendations to develop an

auditing standard that focused

solely on financial statement

fraud, and eventually formed

a fraud task force to formulate

SAS No. 82, Consideration of

Fraud in a Financial Statement

Audit, in February 1997. For the

first time, fraud was included in

the title of an auditing standard.

SAS No. 82 classifies

fraud into two distinct catego-

ries: intentional falsification of

financial statements and theft

of assets. It provides auditors

with a list of risk factors cov-

ering instances of fraudulent

financial reporting and misap-

propriation of assets that they

should assess during an audit,

and requires auditors to docu-

ment both the assessments on

fraud risk and modifications to

the audit plans. Though SAS No.

82 provides additional assurance

to the public that the external

auditors have taken extensive

steps to ensure that they did not

overlook any underlying fraud

and the financial statements are

free of material misstatements,

the Standard does not increase

the auditors responsibility for

detecting fraud beyond the key

concepts of materiality and rea-

sonable assurance.

In 2000, the SEC requested

POB to appoint a panel to

review firms audit effective-

ness. In the report, the panel

recommended that audit firms

hire forensic specialists to pro-

vide auditors with fraud-related

training, and that external

auditors perform forensic-type

procedures on every audit to

enhance the likelihood of detect-

ing material financial statement

50 The Journal of Corporate Accounting & Finance / January/February 2013

DOI 10.1002/jcaf 2013 Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

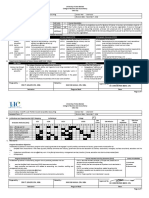

PCAOB Standing Advisory Groups Questions Related to Fraud

No. Questions

SAS No. 99 related

1 Is it appropriate for stockholders to expect auditors to detect fraud that could have a material effect on

the financial statements?

2 Does SAS No. 99 appropriately describe the auditors responsibility for detecting fraud?

Risk and Fraud Risk Factors related

3 Is this list [SAS No. 99] of fraud risk factors helpful to the auditor?

4 Are there other significant fraud risk factors?

Revenue Recognition related

5 Should auditors presume that revenue recognition is a higher risk area demanding that the auditor

perform more extensive procedures?

6 If so, to overcome this presumption, should auditors be required to identify and document persuasive

supporting reasons that the risk of material misstatement due to fraud is remote?

7 Should a proposed standard on fraud include specific procedures that auditors would be required to

perform with respect to revenue recognition?

8 Should auditors be required to inquire of sales and marketing personnel and internal legal counsel about

their knowledge of the companys customary and unusual customer terms or conditions of sales?

9 Are there other practice problems you are aware of in this area?

Significant or Unusual Accruals related

10 Should auditors presume that significant or unusual accruals are a higher risk area demanding that the

auditor perform more extensive procedures?

11 If so, to overcome this presumption, should auditors be required to identify and document persuasive

supporting reasons that the risk of material misstatement due to fraud is remote?

12 Should auditors be required to test the activity within accrual accounts during the period and not just

the ending balances?

13 Should auditors be required to apply substantive tests of details (that is, not rely on analytical proce-

dures only) to corroborate the support for managements judgments and assumptions?

14 Should a proposed standard on fraud include other specific procedures that auditors would be required

to perform with respect to significant or unusual accruals?

15 Are there other practice problems you are aware of in this area?

Related Parties related

16 Should auditors presume that transactions with related parties are a higher risk area demanding that

the auditor perform more extensive procedures?

17 If so, to overcome this presumption, should auditors be required to identify and document persuasive

supporting reasons that the risk of material misstatement due to fraud is remote?

18 Should auditors be required not only to inquire of management, but also the entire board of directors,

about related parties and transactions with those parties?

19 Are there other practice problems you are aware of in this area?

Exhibit 1

(Continues)

The Journal of Corporate Accounting & Finance / January/February 2013 51

2013 Wiley Periodicals, Inc. DOI 10.1002/jcaf

PCAOB Standing Advisory Groups Questions Related to Fraud (Continued)

No. Questions

Estimates of Fair Value related

20 Should auditors presume that assets or liabilities valued using pricing models or similar methods are a

higher risk area demanding that the auditor perform more extensive procedures?

21 Should a proposed standard on fraud include specific procedures that auditors would be required to

perform with respect to such fair value estimates?

22 Are there other practice problems you are aware of in this area?

Analytical Procedures related

23 In performing and evaluating the results of analytical procedures, should auditors be required to

identify key performance indicators of the issuer and the issuers industry?

24 Should auditors be required to compare the key performance indicators to the same measures in prior peri-

ods, to budgets, to the experience of the industry as well as principal competitors within the industry?

25 Should auditors be required to compare nonfinancial information (such as operating statistics) with the

audited financial information?

26 Do auditors overrely on analytical procedures when used as substantive tests? That is, should auditors

be provided definitive direction as to when analytical procedures are appropriate and when

analytical procedures should not be used?

27 Are there other practice problems you are aware of in this area?

Quarterly Financial Information related

28 Should auditors be required to perform certain procedures with respect to the higher risk audit areas (that is,

revenue recognition, related parties, and other high-risk audit areas) while performing quarterly reviews?

29 Should a proposed standard provide specific direction for auditors to follow up each quarter on mate-

rial matters from the prior annual audit and quarterly reviews? (For example, if during the annual

audit the auditor has been told that a significant receivable will be collected within 60 days, then the

auditor should follow up on that matter in the first quarter of the next period.)

30 Should auditors be required to audit significant or unusual transactions concurrently with a review of

the quarterly financial information?

31 Although financial statements are not formally prepared for the fourth quarter, should auditors perform

certain procedures with respect to the financial information for the fourth quarter?

32 Are there other practice problems you are aware of in this area?

Journal Entries related

33 Should a proposed standard on fraud contain explicit imperatives or expectations with respect to the

review of journal entries?

34 If so, should specific direction about the review of journal entries be focused primarily on the review of

nonstandard journal entries as opposed to all journal entries?

35 Should auditors be expected to review journal entries at the close of each reporting periodthat is,

quarterly as well as annual reporting periods?

36 Should auditors be required to review postclosing journal entries, including top-side entries, for each

reporting period?

37 Should auditors be required to review consolidating journal entries for each reporting period?

38 Are there other practice problems you are aware of in this area?

Exhibit 1

(Continues)

52 The Journal of Corporate Accounting & Finance / January/February 2013

DOI 10.1002/jcaf 2013 Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

PCAOB Standing Advisory Groups Questions Related to Fraud (Continued)

No. Questions

Discussions With the Audit Committee related

39 Should auditors be required to inquire of the audit committee about information on complaints and

concerns (from whistleblowers and others) that have been submitted to the board of directors or

audit committee?

40 Should auditors make such inquiries for each quarter and annual reporting period?

Detection of Illegal Acts related

41 Should a proposed standard on fraud include specific procedures for auditors to perform in discharging

their obligations under Section 10A?

42 Should a new standard on the auditors responsibility for the detection of illegal acts by their audit

clients also be considered?

43 Are there other practice problems you are aware of in this area?

Forensic Accountants in an Audit of Financial Statements related

44 Should a forensic specialist, whether employed by the auditors firm or engaged by the auditor, be

regarded as a member of the audit team? Would treating a forensic accountant as an SAS No.

73type specialist create an artificial distinction between the work necessary to detect fraud and the

work necessary to complete an audit?

45 What professional standards should apply to forensic accountants participating in an audit of financial

statements? Should auditors obtain the necessary skills to detect fraud, including forensic skills?

46 Is it acceptable for an auditor to assign responsibility to or otherwise use the work of a forensic spe-

cialist engaged by the company in an audit of financial statements and treat that persons work as

the work of a specialist under SAS No. 73, Using the Work of a Specialist (AU sec. 336)?

47 Can auditors obtain the reasonable assurance required by paragraph .02 of AU sec. 110, Responsibili-

ties and Functions of the Independent Auditor, without performing investigations to determine the

impact of alleged fraudulent activities on the financial statements?

48 What restrictions on the arrangements for the in-depth investigation would be necessary to avoid an

impairment of independence?

49 Does a forensic accountant employ an investigative mindset that is different from the professional

skepticism of an auditor of financial statements?

50 Are there other practice issues that should be addressed in an auditing standard on financial fraud?

beyond the three key conditions

including the need for forensic

specialists in an audit assignment.

CONCLUSION

The audit profession has

gone through a full circle of not

PCAOB on the development of

auditing and related professional

practice standards. This group

has compiled 50 questions that

help identify fraud and fraud risk

factors in the course of an audit

(see Exhibit 1) (PCAOB, 2004).

External auditors need to look

or earnings trend; and low morale

among senior management.

Apart from the preceding

audit guidance is the Standing

Advisory Group (SAG), a group

that consists of external audi-

tors, investors, and public com-

pany executives who advise the

Exhibit 1

The Journal of Corporate Accounting & Finance / January/February 2013 53

2013 Wiley Periodicals, Inc. DOI 10.1002/jcaf

statement audit. Statement on Audit-

ing Standards No. 99. New York, NY:

Author.

Association of Certified Fraud Examiners

(ACFE). (2008). Report to the nation

on occupational fraud abuse. Austin,

TX: Author.

Association of Certified Fraud Examiners

(ACFE). (2010). Report to the nations

on occupational fraud and abuse. Aus-

tin, TX: Author.

International Auditing and Assurance

Standards Board. (2009). The

auditors responsibilities relating to

fraud in an audit of financial state-

ments. International Standard on

Auditing (ISA) No. 240. New York,

NY: Author.

Public Oversight Board (POB). (1993).

In the public interest. Stamford, CT:

Author.

Public Company Accounting Oversight Board

(PCAOB). (2004, September 89).

PCAOB Standing Advisory Group meet-

ing: Financial fraud. Retrieved January

13, 2012, from http://pcaobus.org

/News/Events/Documents/09082004

_SAGMeeting/Fraud.pdf

Public Company Accounting Oversight

Board (PCAOB). (2007, January 22).

Observations on auditors implementa-

tion of PCAOB standards relating

to auditors responsibilities with

respect to fraud. PCAOB Release

No. 2007-001.

Seidler, L. J., Andrews, F., and Epstein, M.J.

(1977). The Equity Funding papers:

The Anatomy of a Fraud. New York,

NY: Wiley.

auditor and the client about fraud

detection and prevention.

NOTES

1. McKesson and Robbins was a wholesale

drug company acquired by F. Donald

Coster in 1926. Coster and his brothers

ran an elaborate accounting scheme to

inflate the companys reported assets for

more than a decade. By 1937, this trans-

lated into over $18 million of fictitious

sales and $19 million worth of nonexist-

ent assets.

2. The Equity Funding scandal involved

bookings of fictitious receivables and

income to inflate earnings per share to

net earnings expectations. Equity Fund-

ing sold insurance to fictitious customers

by selling phony policies. Although there

were sufficient red flags to cause audi-

tors to be more skeptical, they missed the

ongoing fraud including 64,000 phony

transactions with a face value of $2 bil-

lion, $25 million in counterfeit bonds, and

$100 million in missing assets.

REFERENCES

American Institute of Certified Public

Accountants (AICPA). (1939). Exten-

sion of auditing procedure. Statement

on Auditing Procedures No. 1. New

York, NY: Author.

American Institute of Certified Pub-

lic Accountants (AICPA). (2002).

Consideration of fraud in a financial

being responsible to being fully

responsible. Standard setters

and professional bodies have

responded to widely publicized

fraud cases. Standards are merely

guides to the profession, and the

auditors themselves need to exer-

cise due care and diligence in all

assignments. Though manage-

ment is responsible for design-

ing and implementing internal

control systems and detecting

fraud, the auditors need to assess

reliability of the control systems

and report fraud to appropriate

authorities. All these add value

to the audit reports and assure

the public that the reports are

doing what they were designed

to do.

Auditors need to constantly

review their resources, which

includes considering the needs

for forensic specialists and infor-

mation technology specialists in

major audits, and understanding

the clients business activities

by having interim audit visits

and holding regular meetings

with the clients. The two-way

exchanges help improve commu-

nications and educate both the

Gin Chong, professor of accounting at Prairie View A&M University (PVAMU) in Texas, is best known for

his research work on materiality and audit risk, fraud audits, firms performance measurements, and

governance and ethics. He has presented at various national and international conferences, published

over 100 scholarly publications, and is a recipient of several research awards. Professor Chong teaches

undergraduate and graduate courses on accounting, auditing, law and ethics, and accounting information

systems and control, and is a visiting professor of various universities in China and Europe. He has received

many teaching awards. His contact e-mail address is hgchong@pvamu.edu.

Você também pode gostar

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5784)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (119)

- SOA Spring Exam ScheduleDocumento1 páginaSOA Spring Exam ScheduleDormamun StrangeAinda não há avaliações

- DefondDocumento17 páginasDefondLaksmi Mahendrati DwiharjaAinda não há avaliações

- Core 1 - Journalize TransactionsDocumento14 páginasCore 1 - Journalize TransactionsCharlote MarcellanoAinda não há avaliações

- Accounts Payable Processes and Year-End ClosingDocumento5 páginasAccounts Payable Processes and Year-End ClosingNovita WardaniAinda não há avaliações

- KU MBA Syllabus 2013Documento4 páginasKU MBA Syllabus 2013Vinod JoshiAinda não há avaliações

- Write performance objectivesDocumento2 páginasWrite performance objectivesShruti KochharAinda não há avaliações

- Common Effluent Treatment Plants: Technical Eia Guidance ManualDocumento183 páginasCommon Effluent Treatment Plants: Technical Eia Guidance ManualGOWTHAM GUPTHAAinda não há avaliações

- Intosai Gov 9130 eDocumento39 páginasIntosai Gov 9130 enmsusarla999Ainda não há avaliações

- Dhofar Power CompanyDocumento37 páginasDhofar Power CompanylatifasaleemAinda não há avaliações

- 10+ Proven Finance Manager Interview Questions (+answers)Documento6 páginas10+ Proven Finance Manager Interview Questions (+answers)Shirsha NasirafghanAinda não há avaliações

- List of Various CommitteesDocumento8 páginasList of Various CommitteesRamprasad ThankaswamyAinda não há avaliações

- Ais Sarbanes Oxley Act of 2002wfaDocumento19 páginasAis Sarbanes Oxley Act of 2002wfaLeslie Ann ArguellesAinda não há avaliações

- Chapter 16 AnsDocumento7 páginasChapter 16 AnsDave Manalo100% (5)

- Group 7B Satyam MandelaDocumento17 páginasGroup 7B Satyam MandelaPrateek TaoriAinda não há avaliações

- Accounting Information System CH 1 - Systems An OverviewDocumento49 páginasAccounting Information System CH 1 - Systems An OverviewfyramadhanAinda não há avaliações

- TBChap 009Documento58 páginasTBChap 009trevor100% (2)

- Amal RajDocumento6 páginasAmal Rajdr_shaikhfaisalAinda não há avaliações

- Sultana Et Al - 2014 - Audit Committee Characteristics and Audit Report LagDocumento16 páginasSultana Et Al - 2014 - Audit Committee Characteristics and Audit Report LagthoritruongAinda não há avaliações

- Acctg 111B-Partnership and Corporation AccountingDocumento7 páginasAcctg 111B-Partnership and Corporation AccountingElein CodenieraAinda não há avaliações

- Guide Questions in The Study of Part B of Code of Ethics For Professional AccountantsDocumento4 páginasGuide Questions in The Study of Part B of Code of Ethics For Professional AccountantsAnifahchannie PacalnaAinda não há avaliações

- Assessment A - Short - QuestionsDocumento59 páginasAssessment A - Short - Questionsjoe joy0% (1)

- MBA SyllabusDocumento997 páginasMBA SyllabusswarnamaliniAinda não há avaliações

- CH 12 Fraud and ErrorDocumento28 páginasCH 12 Fraud and ErrorJoyce Anne GarduqueAinda não há avaliações

- Module No. 2 - Budget ProcessDocumento32 páginasModule No. 2 - Budget ProcessMon Rean Villaroza Juatchon100% (1)

- South Western Career College, Inc.: Quarter - Module 1Documento19 páginasSouth Western Career College, Inc.: Quarter - Module 1Gessel Ann AbulocionAinda não há avaliações

- Budgetary Cycle in IndiaDocumento4 páginasBudgetary Cycle in Indiasarayupedada1210Ainda não há avaliações

- Blackline Document QuestionsDocumento59 páginasBlackline Document QuestionsNaveed ArshadAinda não há avaliações

- Check List For Post Migration Data Audit of BranchesDocumento5 páginasCheck List For Post Migration Data Audit of BranchesAmitPatilAinda não há avaliações

- PepsiCo Changchun JV Capital AnalysisDocumento2 páginasPepsiCo Changchun JV Capital AnalysisLeung Hiu Yeung50% (2)

- Pillar3 ENGDocumento133 páginasPillar3 ENGInternal AuditAinda não há avaliações