Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Tozan Ryokai (Dongshan Liangjie) - Song of The Jewel Mirror Samadhi PDF

Enviado por

SKYHIGH444Descrição original:

Título original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Tozan Ryokai (Dongshan Liangjie) - Song of The Jewel Mirror Samadhi PDF

Enviado por

SKYHIGH444Direitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Song of Precious Mirror Samadhi

Pao-ching San-mei-ko

By Ch'an Master Tung-shan Liang-chieh

Contents

Title of the Text

Author of the Text

The Pao-ching San-mei-ko

The Original Chinese Text

The Chinese Text with Japanese "Current Characters"

Variant Characters in Different Versions of the Text

Translation of the Text

Japanese Transcription of the Text

Bibliography

Title of the Text

Pao-ching San-mei-ko (Wade-Giles)

Baojing Sanmeige (Pinyin) Bao

3

jing

4

San

1

mei

4

ge

1

Hky Zanmaika (Japanese)

Literally, Treasure Mirror Samdhi Song/Poem

The poem is usually known as Hky

Zammai (Precious Mirror Samdhi ).

Various Translations of the Title

1. The Song of the Jeweled Mirror Samadhi (Toshu John Neatrour, Sheng-

yen, Kazu Tanahashi)

2. Song of the Jewel Mirror Samadhi

3. Sacred Mirror Samadhi (Daisetsu Teitar Suzuki)

4. Samadhi of the Invaluable Mirror

5. Song of the Bright Mirror Samadhi

Author of the Text

Tung-shan Liang-chieh (Wade-Giles)

Dongshan Liangjia (Pinyin) Dong

4

shan

1

Liang

2

jia

4

Tzan Rykai (Japanese)

Tung-shan Liang-chieh (Tzan Rykai, 807-869) is the founder of

the Ts'ao-tung (St) School of Zen Buddhism. He was a contemporary

of Lin-chi I-hsan(Rinzai Gigen, d.866 ).

Tung-shan Liang-chieh is also known as Wu-pen Ta-shih (Gohon

Daishi ).

In Japanese, his name (Tung-shan) is pronounced either as Tzan or

as Tsan.

His sayings and teaching were compiled in Tung-shan Ch'an-shih Liang-

chieh Y-lu (Tzan Rykai Zenji Goroku ) (Dainihon

Zokuzky, vol. 2 No. 24 ).

"Tsan Rykai practiced first under Nansen

1

and Isan

2

, but it was from the

master Ungan Donj

3

that he finally received the Seal. His manner of

instructing and leading his disciples was mild, without stick or shout. In

silent introspection they were to seek the enlightenment which must

manifest itself in the activities of daily life."

(The Development of Chinese Zen After the Sixth Patriarch 25)

"While Tung-shan Liang-chih was still a boy a Vinaya teacher made him

study the Hridaya Stra

4

, and tried to explain the sentence, 'There is no

eye, no nose, . . .' But Liang-chih surveyed his teacher scrutinizingly with

his eye, and then touched his own body with his hand, and finally said,

'You have a pair of eyes, and the other sense-organs, and I am also

provided with them. Why does the Buddha tell us that there are no such

things?' The Vinaya teacher was surprised at his question and told him: 'I

am not capable of being your teacher. You be ordained by a Zen master,

for you will some day be a great teacher of the Mahyna.' "

(Essays in Zen Buddhism Third Series 237-8)

"Yun-mn

5

asked Tung-shan: 'Whence do you come?' 'From Chia-tu.'

'Where did you pass the summer session?' 'At Pao-tzu, in Hu-nan.' 'When

did you come here?' 'August the twenty-fifth.' Yun-mn concluded, 'I

release you from thirty blows [though you rightly deserve them].'

On Tung-shan's interview with Mn, Tai-hui comments:

How simple-hearted Tung-shan was! He answered the master

straightforwardly, and so it was natural for him to reflect, 'What fault did I

commit for which I was to be given thirty blows when I replied as

truthfully as I could?' The day following he appeared again before the

master and asked, 'Yesterday you were pleased to release me from thirty

blows, but I fail to realize my own fault?' Said Yun-mn, 'Oh you rice-bag,

this is the way you wander from the West of the river to the south of the

Lake!' This remark all of a sudden opened Tung-shan's eye, and yet he had

nothing to communicate, nothing to reason about. He simply bowed, and

said, 'After this I shall build my little hut where there is no human

habitation; not a grain of rice will be kept in my pantry, not a stalk of

vegetable will be growing on my farm; and yet I will abundantly treat all

the visitors to my hermitage from all parts of the world; and I will even

draw off all the nails and screws [that are holding them to a stake]; I will

make them part with their greasy hats and ill-smelling clothes, so that they

are thoroughly cleansed of dirt and become worthy monks.' Yun-mn

smiled and said, 'What a large mouth you have for a body no larger than a

coconut!' " (Essays in Zen Buddhism Second Series 28)

"While scholars of the Avatamsaka School

6

were making use of the

intuitions of Zen in their own way, the Zen masters were drawn towards

the philosophy of Indentity and Interpenetration advocated by the

Avatamsaka, and attempted to incorporate it into their own discourses. For

instance, Shih-t'ou

7

in his 'Ode on Identity'

8

depicts the mutuality of Light

and Dark as restricting each other and at the same time being fused in each

other; Tung-shan in his metrical composition called 'Sacred Mirror

Samadhi' discourses on the mutuality of P'ien

9

, 'one-sided', and Chng

10

,

'correct', much to the same effect as Shih-t'ou in his Ode, for both Shih-t'ou

and Tung-shan belong to the school of Hsing-szu known as the Ts'ao-

tung

11

branch of Zen Buddhism. This idea of Mutuality and Indentity is no

doubt derived from Avatamsaka philosophy, so ably formulated by Fa-

tsang. As both Shih-t'ou and Tung-shan are Zen masters, their way of

presenting it is not at all like that of the metaphysician." (Essays in Zen

Buddhism Third Series 19)

"Tung-shan's poem, which was composed when he saw his reflection in the

stream which he was crossing at the time, may give us some glimpse into

his inner experience of the Prajpramit:

Beware of seeking [the Truth] by others,

Further and further he retreats from you;

Alone I go now all by myself,

And I meet him everywhere I turn.

He is no other than myself,

And yet I am not he.

When thus understood,

I am face to face with Tathat."

(Essays in Zen Buddhism Third Series 238)

Long seeking it through others,

I was far from reaching it.

Now I go by myself;

I meet it everywhere.

It is just I myself,

And I am not itself.

Understanding this way,

I can be as I am.

(Two Zen Classics 267)

Do not seek from another,

Or you will be estranged from self.

I now go on alone,

Finding I meet It everywhere.

It now is I,

I now am not It.

One should understand in this way

To merge with suchness as is.

(Transmission of Light 38)

Don't seek from others,

Or you'll be estranged from yourself.

I now go on alone

Everywhere I encounter It.

It now is me, I now am not It.

One must understand in this way

To merge with being as is.

(Transmission of Light 167)

Wu-men Kuan (Mumonkan) Case 15 Tung-shan's Sixty Blows

Tung-shan came to study with Yn-men (Unmon). Yn-men asked, "Where

are you from?"

"From Cha-tu (Sato)," Tung-shan replied.

"Where were you during the summer?"

"Well, I was at the monastery of Pao-tz'u (Hzu), south of the lake."

"When did you leave there," Yn-men asked.

"On August 25" was Tung-shan's reply.

"I spare you sixty blows," Yn-men said.

The next day Tung-shan came to Yn-men and said, "Yesterday you said

you spared me sixty blows.

I beg to ask you, where was I at fault?"

"Oh, you rice bag!" shouted Yn-men. "What makes you wander about,

now west of the river, now south of the lake?"

Tung-shan thereupon came to a mighty enlightenment experience.

Wu-men's Comment

If Yn-men had given Tung-shan the true food of Zen and encouraged him

to develop an active Zen spirit, his school would not have declined as it

did.

Tung-shan had an agonizing struggle through the whole night, lost in the

sea of right and wrong. He reached a complete impasse. After waiting for

the dawn, he again went to Yn-men, and Yn-men again made him a

picture book of Zen.

(Two Zen Classics 61-2)

Wu-men Kuan (Mumonkan) Case 18 Tung-shan's "Ma san chin"

A monk asked Tung-shan, "What is Buddha?"

Tung-shan replied, "Ma san chin!" (Masagin) [three pounds of flax].

(Two Zen Classics 71)

Notes

1

Nan-ch'an P'u-yan (Nansen Fugan, 748-834 )

2

Wei-shan Ling-yu (Isan Reiy 771-853 )

3

Yn-yen T'an-cheng (Ungan Donj 782-841 )

4

The Heart Stra (Hannya Shingy )

Maka Hannya Haramita Shingy (

)

"Heart Sutra (Skt. Mahprajapramit-hridaya-stra, Jap., Maka

hannyaharamita shingy, roughly "Heartpiece of the

'Prajapramit-stra'); shortest of the forty stras that constitute

the Prajapramit-stra."

(The Encyclopedia of Eastern Philosophy and Religion 128)

5

Yn-men Wen-yen (Unmon Bun'en, 864?-949 )

Also known as K'uang-chen Ch'an-shih (Kyshin Zenji )

6

Hua-yen-tsung (Kegonsh )

7

Shih-t'ou Hsi-ch'ien (Sekit Kisen, 700-790 )

8

Ts'an-t'ung-ch'i (Sandkai )

9

One-sided (p'ien, hen )

10

Correct (cheng, sh )

11

Ts'ao-tung (St )

The Pao-ching San-mei-ko

The Pao-ching San-mei-ko is one of the most famous Zen poems. The

poem is regarded a stra in the St Sect, within which it occupies an

important position as a scripture. The text is found in Taish Daizky, vol.

47, No. 515 a-b ().

"One of the Five Classics, I Jing

1

(Book of Changes) is a system of

divination based on the permutations of yin and yang, examining present

tendencies toward change as represented through the use of six-line

combinations of broken and unbroken lines, called hexagrams. Dongshan

Liangjie refers expressly to this work in his famous poem, Baojing sanmei

ke (Song of the Jewel Mirror Samadhi), a core-text of Cao-Dong

2

: "It is

like the six lines of the double split hexagram; the relative and absolute

integrate piled up, they make the three; the complete transformation

makes five."

3

Indeed, Dongshan's teaching of the Five Ranks

4

can also be

understood as a diagrammatic explanation of the interaction between yin

and yang, transposed into a Buddhist context."

Notes

1

I Ching (Ekiky )

2

Ts'ao-tung (St )

3

4

Wu-wei (Goi )

The Original Chinese Text

The Chinese Text with Japanese "Current Characters"

In the following text, the obsolete characters in the original text are

replaced with newer, simplified or slightly altered characters used in

contemporary Japanese, known as Ty Kanji. These newer characters are

indicated with gray color. Also, in the Japanese versions of the text, some

Chinese characters are replaced with similar characters. These characters

are indicated with blue color.

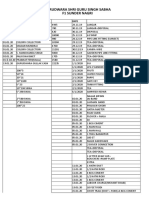

Variant Characters in Different Versions of the Text

Line Japanese Version Chinese Version

X Code: &C3-325B

2

3

4

7

10

12

13

14

19

30

31

40

41

46

47

Translation of the Text

Song of Precious Mirror Samadhi

The dharma of thusness is intimately

transmitted by buddhas and ancestors.

Now you have it; preserve it well.

A silver bowl filled with snow, a heron hidden

in the moon.

Taken as similar, they are not the same; not

distinguished, their places are known.

The meaning does not reside in the words, but a

pivotal moment brings it forth.

Move and you are trapped, miss and you fall

into doubt and vacillation.

Turning away and touching are both wrong, for

it is like a massive fire.

Just to portray it in literary form is to stain it

with defilement.

In darkest night it is perfectly clear; in the light

of dawn it is hidden.

It is a standard for all things; its use removes all

suffering.

Although it is not constructed, it is not beyond

words.

Like facing a precious mirror; form and

reflection behold each other.

You are not it, but in truth it is you.

Like a newborn child, it is fully endowed with

five aspects:

No going, no coming, no arising, no abiding;

P'o-p'o han-han is anything said or not?

In the end it says nothing, for the words are not

yet right.

In the hexagram "double fire," when main and

subsidiary lines are transposed,

Piled up they become three; the permutations

make five.

Like the taste of the five-flavored herb, like the

five-pronged vajra.

Wondrously embraced within the complete,

drumming and singing begin together.

Penetrate the source and travel the pathways,

embrace the territory and treasure the roads.

You would do well to respect this; do not

neglect it.

Natural and wondrous, it is not a matter of

delusion or enlightenment.

Within causes and conditions, time and season,

it is serene and illuminating.

So minute it enters where there is no gap, so

vast it transcends dimension.

A hairsbreadth's deviation, and you are out tune.

Now there are sudden and gradual, in which

teachings and approaches arise.

With teachings and approaches distinguished,

each has its standard.

Whether teachings and approaches are mastered

or not, reality constantly flows.

Outside still and inside trembling, like tethered

colts or cowering rats.

The ancient sages grieved for them, and offered

them the dharma.

Led by their inverted views, they take black for

white.

When inverted thinking stops, the affirming

mind naturally accords.

If you want to follow in the ancient tracks,

please observe the sages of the past.

One on the verge of realizing the Buddha Way

contemplated a tree for ten kalpas.

Like a battle-scarred tiger, like a horse with

shanks gone grey.

Because some are vulgar, jeweled tables and

ornate robes.

Because others are wide-eyed, cats and white

oxen.

With his archer's skill, Yi hit the mark at a

hundred paces.

But when arrows meet head-on, how could it be

a matter of skill?

The wooden man starts to sing, the stone

woman gets up dancing.

It is not reached by feelings or consciousness,

how could it involve deliberation?

Ministers serve their lords, children obey their

parents.

Not obeying is not filial, failure to serve is no

help.

With practice hidden, function secretly, like a

fool, like an idiot.

Just to continue in this way is called the host

within the host.

The Song of the Jeweled Mirror Samadhi

Translated by Toshu John Neatrour, Sheng-yen, and Kazu Tanahashi

The teaching of suchness, is given directly,

through all buddha ancestors,

Now that it's yours, keep it well.

A serving of snow in a silver bowl, or herons

concealed in the glare of the moon

Apart, they seem similar, together, they're

different.

Meaning cannot rest in words, it adapts itself to

that which arises.

Tremble and you're lost in a trap, miss and

there's always regrets.

Neither reject nor cling to words, both are

wrong; like a ball of fire,

Useful but dangerous. Merely expressed in fine

language, the mirror will tarnish.

At midnight truly it's most bright, by daylight it

cannot still be seen.

It is the principle that regulates all, relieving

every suffering.

Though it doesn't act it is not without words.

In the most precious mirror form meets

reflection:

You are not It, but It is all you.

Just as a baby, five senses complete,

Neither going or coming, nor arising or staying,

Babbles and coos: speech without meaning,

No understanding, unclearly expressed.

Six lines make the double li trigram, where

principle and appearances interact.

Lines stacked in three pairs yet transform in

five ways.

Like the five flavors of the hyssop plant or the

five branches of the diamond scepter,

Reality harmonizes subtly just as melody and

rhythm, together make music.

Penetrate the root and you fathom the branches,

grasping connections, one then finds the road.

To be wrong is auspicious, there's no

contradiction.

Naturally pure and profoundly subtle, it touches

neither delusion nor awakening,

At each time and condition it quietly shines.

So fine it penetrates no space at all, so large its

bounds can never be measured.

But if you're off by a hair's breadth all

harmony's lost in discord.

Now there are sudden and gradual schools with

principles, approaches so standards arise.

Penetrating the principle,

Mastering the approach, the genuine constant

continues outflowing.

A tethered horse, a mouse frozen in fear,

outwardly still but inwardly whirling:

Compassionate sages freed them with teaching.

In upside down ways folks take black for white.

When inverted thinking falls away they realize

mind without even trying.

If you want to follow the ancient path then

consider the ancients:

The buddha, completing the path, still sat for

ten eons.

Like a tiger leaving a trace of the prey, like a

horse missing the left hind shoe,

For those whose ability is under the mark, a

jeweled footrest and brocaded robe.

For others who still can manifest wonder

there's a house cat and cow.

Yi the archer shot nine of ten suns from the sky,

saving parched crops, another bowman hit targets at hundreds of paces:

These skills are small to compare with that in

which two arrow points meet head on in mid air.

The wooden man breaks into song, a stone

maiden leaps up to dance,

They can't be known by mere thought or

feelings, so how can they be analyzed?

The minister still serves his lord, the child

obeys his parent.

Not obeying is unfilial, not serving is a useless

waste.

Practicing inwardly, functioning in secret,

playing the fool, seemingly stupid,

If you can only persist in this way, you will see

the lord within the lord.

Japanese Transcription of the Text

Hky Zanmaika

Nyoze no h Busso mitsu ni fusu.

Nanji ima kore o etari, yoroshiku yoku hgo

subeshi.

Ginwan ni yuki o mori, meigetsu ni ro o

kakusu.

Rui shite hitoshikarazu. Konzuru tokinba

tokoro o shiru.

Kokoro koto ni arazareba, raiki mata

omomuku.

Dzureba kakyu o nashi, tagaeba kocho ni otsu.

Haisoku tomo ni hi nari. Daijaku no gotoshi.

Tada monsai ni arawaseba, sunawachi zenna ni

zokusu.

Yahan shmei, tengy furo.

Mono no tame ni nori to naru. Moichiite shku

o nuku.

Ui ni arazu to iedomo, kore go naki ni arazu.

Hky ni nozonde, gyy aimiru ga gotoshi.

Nanji kore kare ni arazu, kare masa ni kore

nanji.

Yo no yji no gos gangu suru ga gotoshi.

Fukyo, furai, fuku, fuj.

Ba-ba wa-wa, uku, muku,

Tsui ni mono o ezu, go imada tadashikarazaru

ga yue ni.

Juri rikk, hensh ego,

Tatande san to nari, henji tsukite go to naru.

Chis no ajiwai no gotoku, kong no sho no

gotoshi.

Shch myky, ksh narabi agu.

Sh ni tsji to ni tszu, kytai kyro.

Shakunen naru tokinba kitsu nari. Bongo

subekarazu.

Tenshin ni shite my nari. Meigo ni zoku sezu.

Innen jisetsu, jakunen to shite shcho su.

Sai ni wa muken ni iri, dai ni wa hjo o zessu.

Gkotsu no tagai, ritsuryo ni zezu.

Ima tonzen ari, shshu o rissuru ni yotte.

Shshu wakaru, sunawachi kore kiku nari.

Sh tsji shu kiwamaru mo, shinj ruch.

Hoka jaku ni uchiogoku wa, tsunageru koma,

fukuseru nezumi.

Sensh kore o kanashinde h no dando to naru.

Sono tend ni shitagatte shi o motte so to nasu.

Tend smetsu sureba kshin mizukara yurusu.

Kotetsu ni kanawan to yseba k zenko o

kanzeyo.

Butsud o jzuru ni nannan to shite jukk ju o

kanzu.

Tora no kaketaru ga gotoku, uma no yome no

gotoshi.

Geretsu aru o motte hki chingyo,

Kyi aru o motte rinu byakko.

Gei wa gyriki o motteite hyappo ni atsu,

Senp aiau, gyriki nanzo azukaran.

Bokujin masa ni utai, sekijo tatte mau.

Jshiki no itaru ni arazu, mushiro shiryo o iren

ya.

Shin wa kimi ni bushi, ko wa chichi ni junzu.

Junzezareba k ni arazu, busezareba ho ni

arazu.

Senk mitsuy wa gu no gotoku, ro no gotoshi.

Tada yoku szoku suru o shuch no shu to

nazuku.

____________________________________________________________

_________________________________________

Bibliography

The Development of Chinese Zen After the Sixth Patriarch. Heinrich

Dumoulin. SMC Publishing, Inc. Taipei, n.d..

The Encyclopedia of Eastern Philosophy and Religion. Ingrid Fischer-

Schreiber, et al. Shambhala Publications. New York, 1994.

Essays in Zen Buddhism, 3 vols. Daisetsu Teitaro Suzuki. Rider and

Company. London, 1949-53.

Two Zen Classics. Katsuki Sekida. Weatherhill. New York, 1995.

Zen Essence: The Science of Freedom. Ed. and trans. by Thomas Cleary.

Shambhala Publications. New York, 1989.

Você também pode gostar

- Song of Precious Mirror Samadhi Pao-Ching San-Mei-Ko by Ch'an Master Tung-Shan Liang-ChiehDocumento24 páginasSong of Precious Mirror Samadhi Pao-Ching San-Mei-Ko by Ch'an Master Tung-Shan Liang-ChiehformlessFlowerAinda não há avaliações

- Ksitigarbha SutraDocumento46 páginasKsitigarbha SutraSiegfried SchwaigerAinda não há avaliações

- Zen PoemsDocumento26 páginasZen PoemssiboneyAinda não há avaliações

- Final Updated Yamantaka With Story, Prayer, Practice, and Commentary-EDITEDDocumento137 páginasFinal Updated Yamantaka With Story, Prayer, Practice, and Commentary-EDITEDUrgyan Tenpa Rinpoche100% (13)

- Reflections on Silver River: Tokme Zongpo's Thirty-Seven Practices of a BodhisattvaNo EverandReflections on Silver River: Tokme Zongpo's Thirty-Seven Practices of a BodhisattvaNota: 5 de 5 estrelas5/5 (3)

- Biography of Kunga PaldenDocumento9 páginasBiography of Kunga PaldenJon DilleyAinda não há avaliações

- The Life of Sri Ramana MaharshiDocumento11 páginasThe Life of Sri Ramana MaharshiDeepa HAinda não há avaliações

- Yoga Spandakarika: The Sacred Texts at the Origins of TantraNo EverandYoga Spandakarika: The Sacred Texts at the Origins of TantraNota: 5 de 5 estrelas5/5 (5)

- Who Taught Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche TsaluDocumento10 páginasWho Taught Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche TsaluJon DilleyAinda não há avaliações

- BIOGRAPHY Jamyang Khyentse Chokyi Lodro 1893Documento4 páginasBIOGRAPHY Jamyang Khyentse Chokyi Lodro 1893Thubten KönchogAinda não há avaliações

- A Glimpse Into The Ishopanishad - Swami Abhiramananda-RK Institute of Culture Aug. 2018Documento11 páginasA Glimpse Into The Ishopanishad - Swami Abhiramananda-RK Institute of Culture Aug. 2018muruganarAinda não há avaliações

- Reflections of Ajahn ChahDocumento176 páginasReflections of Ajahn ChahrokantasAinda não há avaliações

- Zen Sayings & PoemsDocumento34 páginasZen Sayings & Poemsmorefaya2006Ainda não há avaliações

- Hek 001Documento7 páginasHek 001david smithAinda não há avaliações

- Shodoka Harada RoshiDocumento4 páginasShodoka Harada RoshiJordana Myōkō GlezAinda não há avaliações

- The Life of Sri Ramana MaharshiDocumento19 páginasThe Life of Sri Ramana MaharshiKasarla ShivakumarAinda não há avaliações

- Empty Cloud, The Teachings of Zen Master Xu YunDocumento92 páginasEmpty Cloud, The Teachings of Zen Master Xu YunbatcavernaAinda não há avaliações

- Biography of Sunlun Sayadaw Thynn ThynnDocumento183 páginasBiography of Sunlun Sayadaw Thynn ThynndhammapiyaAinda não há avaliações

- Biography of Jamgön Ju MiphamDocumento6 páginasBiography of Jamgön Ju MiphamBLhundrupAinda não há avaliações

- 101 Powerful Zen Sayings and Proverbs - BuddhaimoniaDocumento28 páginas101 Powerful Zen Sayings and Proverbs - BuddhaimoniaLokesh Kaushik100% (2)

- Issue 4Documento64 páginasIssue 4rhvenkatAinda não há avaliações

- Unmon Medicine and SicknessDocumento7 páginasUnmon Medicine and SicknessmetaltigerAinda não há avaliações

- Supreme Being in A MomentDocumento5 páginasSupreme Being in A Momentmahendrachjoshi100% (1)

- Tiantong Mountain, Jingde Temple, Chan Teacher Rujing's Continuing Record of SayingsDocumento6 páginasTiantong Mountain, Jingde Temple, Chan Teacher Rujing's Continuing Record of SayingsNicolas CevennesAinda não há avaliações

- A Conversation With Hsü YünDocumento4 páginasA Conversation With Hsü YünsevyAinda não há avaliações

- The Gathering of Intentions: A History of a Tibetan TantraNo EverandThe Gathering of Intentions: A History of a Tibetan TantraNota: 5 de 5 estrelas5/5 (1)

- The Finger and the Moon: Zen Teachings and KoansNo EverandThe Finger and the Moon: Zen Teachings and KoansAinda não há avaliações

- "Small Boat, Great Mountain", by Amaro BikkhuDocumento218 páginas"Small Boat, Great Mountain", by Amaro BikkhuNathan RosquistAinda não há avaliações

- Zen Poetry Selected Quotations I: - Layman Pang-Yun (740-808)Documento32 páginasZen Poetry Selected Quotations I: - Layman Pang-Yun (740-808)ljubichAinda não há avaliações

- Turning The Light Around and Shining BackDocumento2 páginasTurning The Light Around and Shining BackTest4DAinda não há avaliações

- Song of the Road: The Poetic Travel Journal of Tsarchen Losal GyatsoNo EverandSong of the Road: The Poetic Travel Journal of Tsarchen Losal GyatsoAinda não há avaliações

- A Garland of White LotusesDocumento83 páginasA Garland of White LotusesHoang LinhAinda não há avaliações

- Nyingtik YabshyiDocumento5 páginasNyingtik YabshyiWalker Sky88% (8)

- Song EnlightenmentDocumento57 páginasSong EnlightenmentAnonymous 5SUTrLIKRoAinda não há avaliações

- Garchen Rinpoche's History of Giving RefugeDocumento8 páginasGarchen Rinpoche's History of Giving RefugeHelbert de OliveiraAinda não há avaliações

- Blue Cliff Record Case 5 - John TarrantDocumento4 páginasBlue Cliff Record Case 5 - John TarrantPapy Rys100% (1)

- Master Nan Huai-Chin Provides A Practice Lesson On Qigong, Pranayama, Anapana and Breathing Exercises - Part 1Documento5 páginasMaster Nan Huai-Chin Provides A Practice Lesson On Qigong, Pranayama, Anapana and Breathing Exercises - Part 1Varadrajan MudliyarAinda não há avaliações

- A Zen Harvest: Japanese Folk Zen Sayings (Haiku, Dodoitsu, and Waka)No EverandA Zen Harvest: Japanese Folk Zen Sayings (Haiku, Dodoitsu, and Waka)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (4)

- The Mind of Clover: Essays in Zen Buddhist EthicsNo EverandThe Mind of Clover: Essays in Zen Buddhist EthicsNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (5)

- 01 - Huatou - Dahui Zonggao - PPT v.2 - KopyaDocumento18 páginas01 - Huatou - Dahui Zonggao - PPT v.2 - KopyaHaşim LokmanhekimAinda não há avaliações

- White Tara Long PDFDocumento20 páginasWhite Tara Long PDFВалерий Кулагин100% (5)

- Records of The Life of Tripitaka Master HuaDocumento2 páginasRecords of The Life of Tripitaka Master HuaGede GiriAinda não há avaliações

- Ramana Maharshi - Arunachala PancharatnaDocumento18 páginasRamana Maharshi - Arunachala PancharatnakevaloAinda não há avaliações

- Paths To The Lotus PondDocumento50 páginasPaths To The Lotus Pondtankonghui954Ainda não há avaliações

- Vajrasattva SadhanaDocumento8 páginasVajrasattva Sadhanaweyer100% (2)

- Shenpen Osel - Issue 4Documento64 páginasShenpen Osel - Issue 4Robb RiddelAinda não há avaliações

- Etri Bib MaitreyaDocumento0 páginaEtri Bib MaitreyaStephane CholletAinda não há avaliações

- Ramana MaharshiDocumento18 páginasRamana MaharshiMp Sunil100% (4)

- Alone With DhammaDocumento27 páginasAlone With DhammaAlan Weller100% (1)

- Yoga AsanasDocumento200 páginasYoga Asanascrsz88% (42)

- Buddhistlegends02burluoft BWDocumento370 páginasBuddhistlegends02burluoft BWAndy FrancisAinda não há avaliações

- Journal of The Buddhist ViharaDocumento8 páginasJournal of The Buddhist Viharaccol777Ainda não há avaliações

- Book1 Mahasiddha ManifestationsDocumento791 páginasBook1 Mahasiddha ManifestationsTùng Hoàng100% (1)

- Shikantaza ReaderDocumento69 páginasShikantaza ReaderCarolBhagavatiMcDonnell100% (1)

- The Role of Vitamin D in Your Body and Your Muscles - Brian Fulton - Registered Massage TherapistDocumento4 páginasThe Role of Vitamin D in Your Body and Your Muscles - Brian Fulton - Registered Massage TherapistSKYHIGH444Ainda não há avaliações

- Gay Guide To Belgrade 2010Documento10 páginasGay Guide To Belgrade 2010SKYHIGH444Ainda não há avaliações

- Face To Face With Sri Ramana MaharshiDocumento500 páginasFace To Face With Sri Ramana MaharshiRamakrishna Mukkamala100% (4)

- Fat - How Much Do We Need? - Brian Fulton - Registered Massage TherapistDocumento8 páginasFat - How Much Do We Need? - Brian Fulton - Registered Massage TherapistSKYHIGH444Ainda não há avaliações

- Are You Eating Too Much Protein? - Brian Fulton - Registered Massage TherapistDocumento6 páginasAre You Eating Too Much Protein? - Brian Fulton - Registered Massage TherapistSKYHIGH444Ainda não há avaliações

- Fat - How Much Do We Need? - Brian Fulton - Registered Massage TherapistDocumento5 páginasFat - How Much Do We Need? - Brian Fulton - Registered Massage TherapistSKYHIGH444Ainda não há avaliações

- Twenty Good Reasons To Not Eat From Within Your Own Kingdom - Brian Fulton - Registered Massage TherapistDocumento11 páginasTwenty Good Reasons To Not Eat From Within Your Own Kingdom - Brian Fulton - Registered Massage TherapistSKYHIGH444Ainda não há avaliações

- William Samuel - A Gentle Teaching of Tranquility and Awareness PDFDocumento4 páginasWilliam Samuel - A Gentle Teaching of Tranquility and Awareness PDFSKYHIGH444Ainda não há avaliações

- Testing The Waters: Gellert Baths, Budapest - Hungary, Europe - BootsnAll PDFDocumento3 páginasTesting The Waters: Gellert Baths, Budapest - Hungary, Europe - BootsnAll PDFSKYHIGH444Ainda não há avaliações

- Are You Eating Too Much Protein? - Brian Fulton - Registered Massage TherapistDocumento6 páginasAre You Eating Too Much Protein? - Brian Fulton - Registered Massage TherapistSKYHIGH444Ainda não há avaliações

- The Role of Vitamin D in Your Body and Your Muscles - Brian Fulton - Registered Massage TherapistDocumento4 páginasThe Role of Vitamin D in Your Body and Your Muscles - Brian Fulton - Registered Massage TherapistSKYHIGH444Ainda não há avaliações

- Twenty Good Reasons To Not Eat From Within Your Own Kingdom - Brian Fulton - Registered Massage TherapistDocumento11 páginasTwenty Good Reasons To Not Eat From Within Your Own Kingdom - Brian Fulton - Registered Massage TherapistSKYHIGH444Ainda não há avaliações

- Fat - How Much Do We Need? - Brian Fulton - Registered Massage TherapistDocumento8 páginasFat - How Much Do We Need? - Brian Fulton - Registered Massage TherapistSKYHIGH444Ainda não há avaliações

- William Samuel - A Gentle Teaching of Tranquility and Awareness PDFDocumento4 páginasWilliam Samuel - A Gentle Teaching of Tranquility and Awareness PDFSKYHIGH444Ainda não há avaliações

- Vito Russo - The Celluloid Closet-Homosexuality in The MoviesDocumento240 páginasVito Russo - The Celluloid Closet-Homosexuality in The MoviesSKYHIGH44492% (13)

- Library: Leonard Cohen's Tale of Redemption: Maclean's (Magazine), October 22, 2012 PDFDocumento4 páginasLibrary: Leonard Cohen's Tale of Redemption: Maclean's (Magazine), October 22, 2012 PDFSKYHIGH444Ainda não há avaliações

- First Listen: Leonard Cohen, 'Popular Problems': NPR PDFDocumento2 páginasFirst Listen: Leonard Cohen, 'Popular Problems': NPR PDFSKYHIGH444Ainda não há avaliações

- Top 10 Tips To Enjoy Széchenyi Thermal Baths in Budapest My Traveling Joys PDFDocumento5 páginasTop 10 Tips To Enjoy Széchenyi Thermal Baths in Budapest My Traveling Joys PDFSKYHIGH444Ainda não há avaliações

- Underground Budapest: Caverns, Churches and Bunkers PDFDocumento5 páginasUnderground Budapest: Caverns, Churches and Bunkers PDFSKYHIGH444Ainda não há avaliações

- Spas in Budapest - Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia PDFDocumento4 páginasSpas in Budapest - Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia PDFSKYHIGH444Ainda não há avaliações

- The Best of Gay Budapest PDFDocumento5 páginasThe Best of Gay Budapest PDFSKYHIGH444Ainda não há avaliações

- Top Five Medicinal Baths in Budapest - Worldette PDFDocumento3 páginasTop Five Medicinal Baths in Budapest - Worldette PDFSKYHIGH444Ainda não há avaliações

- Taking To The Waters in Budapest PDFDocumento2 páginasTaking To The Waters in Budapest PDFSKYHIGH444Ainda não há avaliações

- Etiquette 101: Baths, Saunas, Spa Treatments - Condé Nast Traveler PDFDocumento7 páginasEtiquette 101: Baths, Saunas, Spa Treatments - Condé Nast Traveler PDFSKYHIGH444Ainda não há avaliações

- Budapest Baths - Paradise Apartments in The City Center of Budapest PDFDocumento4 páginasBudapest Baths - Paradise Apartments in The City Center of Budapest PDFSKYHIGH444Ainda não há avaliações

- Letter From Hungary: Soaking in The History in The Bathhouses of Budapest - Gadling PDFDocumento6 páginasLetter From Hungary: Soaking in The History in The Bathhouses of Budapest - Gadling PDFSKYHIGH444Ainda não há avaliações

- Practical Facts: How To Visit Budapest's Baths PDFDocumento5 páginasPractical Facts: How To Visit Budapest's Baths PDFSKYHIGH444Ainda não há avaliações

- Getting The Best Out of Budapest's Baths PDFDocumento2 páginasGetting The Best Out of Budapest's Baths PDFSKYHIGH444Ainda não há avaliações

- Gay Guide Article PDFDocumento2 páginasGay Guide Article PDFSKYHIGH444Ainda não há avaliações

- Baths in Budapest: Exploring Budapest's Thermal Baths PDFDocumento6 páginasBaths in Budapest: Exploring Budapest's Thermal Baths PDFSKYHIGH444Ainda não há avaliações

- Srimad Bhagavatam PuranaDocumento148 páginasSrimad Bhagavatam PuranaJayadhvaja Dasa100% (3)

- Spiritually and Mystical Religion in Contemporary SocietyDocumento19 páginasSpiritually and Mystical Religion in Contemporary SocietykarlgutylopscribdAinda não há avaliações

- Magical Knot PDFDocumento21 páginasMagical Knot PDFKishoreBijja100% (1)

- Tourism in IndiaDocumento30 páginasTourism in IndianehaseththedonAinda não há avaliações

- A Critical Examination of The Life and Teachings of Mohammed (1873) - Syed Ameer AliDocumento368 páginasA Critical Examination of The Life and Teachings of Mohammed (1873) - Syed Ameer AliRizwan JamilAinda não há avaliações

- Jesus Christ The Bearer of The Water of Life A Christian Reflection On The "New Age"Documento66 páginasJesus Christ The Bearer of The Water of Life A Christian Reflection On The "New Age"jstadlasAinda não há avaliações

- The Doctrine of The Mithraic Mysteries PDFDocumento14 páginasThe Doctrine of The Mithraic Mysteries PDFPaul VelhoAinda não há avaliações

- Cultural Heritage Vol VIDocumento598 páginasCultural Heritage Vol VIAlejandro SanchezAinda não há avaliações

- Certificate: 5th Mahamana Malaviya National Moot Court Competition - 2017Documento2 páginasCertificate: 5th Mahamana Malaviya National Moot Court Competition - 2017Shekhar ShumanAinda não há avaliações

- Vedanta in ManagementDocumento7 páginasVedanta in ManagementRaja SubramaniyanAinda não há avaliações

- Inner War and PeaceDocumento382 páginasInner War and Peaceyaminisreevalli100% (8)

- The Five NiyamasDocumento2 páginasThe Five NiyamasScottAinda não há avaliações

- Khilji DynastyDocumento26 páginasKhilji DynastynikAinda não há avaliações

- Kaveri MahimaDocumento32 páginasKaveri MahimaKarthik KumarAinda não há avaliações

- How To Tackle Sade-Sathi? - Remedies For Saturn's (Shani) Unfavourable Transit (Gochaara)Documento5 páginasHow To Tackle Sade-Sathi? - Remedies For Saturn's (Shani) Unfavourable Transit (Gochaara)bhargavasarma (nirikhi krishna bhagavan)100% (2)

- Dharmashashtra National Law University, Jabalpur: Subject-History-2 Project - CAD - Freedom of ReligionDocumento21 páginasDharmashashtra National Law University, Jabalpur: Subject-History-2 Project - CAD - Freedom of ReligionAbhishek Kumar ShahAinda não há avaliações

- E-Book Bali My Love A Journey of Peace-1Documento130 páginasE-Book Bali My Love A Journey of Peace-1Ginanjar Surya RamadhanAinda não há avaliações

- Astrology-10th House Karma Bhava (Documento20 páginasAstrology-10th House Karma Bhava (puneetAinda não há avaliações

- Rice SopDocumento4 páginasRice SopKaustubh Das DehlviAinda não há avaliações

- World History-Chapter 3 India and China PDFDocumento13 páginasWorld History-Chapter 3 India and China PDFJonathan Daniel KeckAinda não há avaliações

- The Genesis of The Five Aggregate TeachingDocumento26 páginasThe Genesis of The Five Aggregate Teachingcrizna1Ainda não há avaliações

- Dibya Upadesh of King Prithivi Narayan S PDFDocumento10 páginasDibya Upadesh of King Prithivi Narayan S PDFabiskarAinda não há avaliações

- Shat Chakra BhedaDocumento3 páginasShat Chakra BhedaPhalgun BalaajiAinda não há avaliações

- The Sauptikaparvan of The Mahabharata: The Massacre at NightDocumento185 páginasThe Sauptikaparvan of The Mahabharata: The Massacre at NightTeodora IoanaAinda não há avaliações

- Kali Kaula A Manual of Tantric Magick HardbackDocumento3 páginasKali Kaula A Manual of Tantric Magick Hardbackalintuta20% (1)

- His Mothers Wish by Promodini Parayitam Indian Review Short StorDocumento7 páginasHis Mothers Wish by Promodini Parayitam Indian Review Short StorgollakotiAinda não há avaliações

- RanaDocumento34 páginasRanaSudhir YadavAinda não há avaliações

- A Yoga-OutlineDocumento3 páginasA Yoga-Outlineshreevinekar100% (1)

- Kundalini Kriya Auric BalanceDocumento1 páginaKundalini Kriya Auric BalanceNatalina Dass Tera LodatoAinda não há avaliações

- Courses of Studies For Master Degree in YogaDocumento14 páginasCourses of Studies For Master Degree in YogaViroopaksha V JaddipalAinda não há avaliações