Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

In Darkest Africa - Part One: by CHRIS PEERS (With A Painting Guide by Mark Copplestone)

Enviado por

Spanishfury100%(1)100% acharam este documento útil (1 voto)

273 visualizações6 páginasThis document provides an introduction and historical background for a set of wargaming rules and campaign system for skirmishes in Central Africa in the late 19th century. It describes the different troop types that would be represented in such games, including Europeans, Askaris, native musketeers, archers, and subclasses like elite Askaris and Baluchis. The rules are intended to recreate the large skirmishes between forces of varying technology and organization, representing explorers, slavers, ivory traders, and native armies of the time period.

Descrição original:

The first in a series of excellent and informative articles supporting a set of rules for wargaming colonial adventures in Africa from the middle to the end of the 19th Century using miniatures figures.

Título original

In Darkest Africa (1)

Direitos autorais

© © All Rights Reserved

Formatos disponíveis

PDF, TXT ou leia online no Scribd

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoThis document provides an introduction and historical background for a set of wargaming rules and campaign system for skirmishes in Central Africa in the late 19th century. It describes the different troop types that would be represented in such games, including Europeans, Askaris, native musketeers, archers, and subclasses like elite Askaris and Baluchis. The rules are intended to recreate the large skirmishes between forces of varying technology and organization, representing explorers, slavers, ivory traders, and native armies of the time period.

Direitos autorais:

© All Rights Reserved

Formatos disponíveis

Baixe no formato PDF, TXT ou leia online no Scribd

100%(1)100% acharam este documento útil (1 voto)

273 visualizações6 páginasIn Darkest Africa - Part One: by CHRIS PEERS (With A Painting Guide by Mark Copplestone)

Enviado por

SpanishfuryThis document provides an introduction and historical background for a set of wargaming rules and campaign system for skirmishes in Central Africa in the late 19th century. It describes the different troop types that would be represented in such games, including Europeans, Askaris, native musketeers, archers, and subclasses like elite Askaris and Baluchis. The rules are intended to recreate the large skirmishes between forces of varying technology and organization, representing explorers, slavers, ivory traders, and native armies of the time period.

Direitos autorais:

© All Rights Reserved

Formatos disponíveis

Baixe no formato PDF, TXT ou leia online no Scribd

Você está na página 1de 6

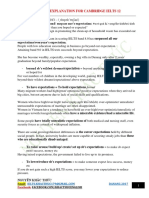

IN DARKEST AFRICA - Part One

A GUIDE TO WARGAMING CENTRAL AFRICA IN THE LATE NINETEENTH CENTURY

WITH A SET OF SKIRMISH RULES AND CAMPAIGN SYSTEM.

by CHRIS PEERS (with a painting guide by Mark Copplestone).

As most wargamers have learned from experience, it is a

sensible policy to plan our figure collecting around the rules

that we enjoy playing, rather than buying figures because we

like the look of them, and then worrying about what to do with

them later. But of course, it usually doesn't happen that way.

The latest temptation to shake my resolve in this respect is

Mark Copplestone's new 25mm. Darkest Africa range from

Guernsey Foundry. I have always been interested in events in

Africa during the period of exploration, but until now I had

never thought much about it as a subject for wargaming. But

having decided that the figures were going to be irresistible -

and having seen how many other members of my local club

were infected with the same enthusiasm - it was obvious that

we would need a game we could play with them.

The following ideas are an amalgamation of several different

influences: notably Peter Pig's AK-47 Republic Modern

African rules and the campaign system which I devised for

them, and my own, half-forgotten, Cheap and Nasty Indian

Mutiny Skirmish Rules, as revived and revised by Mark

Copplestone and John French. I wrote the latter quite a few

years ago, for the usual reason - I had painted up some of

Wargames Foundry's Mutiny figures, but had no game which I

could use them for - and Duncan was kind enough to publish

them in WI at the time. To judge from the feedback from

readers this must have been the most popular article I have ever

written, which is a bit embarrassing as I threw the rules together

in about half an hour, between finishing the figures on Sunday

and playing the game on the following Tuesday. No one was

more surprised than I was to find that, incredibly basic though

they were, they actually worked! Nevertheless, they

languished largely forgotten for quite a while, until out of the

blue Mark and John asked if I minded if they adapted them for

their African game at Partizan this May. Of course I didn't

mind: they had solved my problem as well as their own. After

all, the rules were intended specifically for large 19th century

skirmishes between forces at different levels of technology and

organisation, and with a few obvious changes, they appeared to

work for Africa just as well as for India.

Skirmish games are all very well for an occasional light-

hearted encounter, but I find that people tend to lose interest in

them after a while, unless they are built into some more durable

structure. No one wants to buy a few hundred figures, put them

on the table once or twice, and then shove them to the back of a

drawer. Obviously, what was needed was an equally simple

campaign. And once again, the solution was already to hand. I

have explained in a previous article the stylised campaign

system which we (ie. the October Club in Birmingham) are

using for our current Modern African campaign, The

Dagomban Civil War. Well, it turns out that long-suffering

(but fortunately fictional) Dagomba was also a scene of

conflict about a hundred and thirty years ago. The system I

have used here is not identical to the modern version, because

the aims of the different factions are different, but the basic

snakes and ladders principle is the same, and basing it on the

map of Dagomba saved me the bother of finding or inventing a

new set of place-names.

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND.

By the third quarter of the 19th century, East and Central Africa

had become something of a playground for explorers and

adventurers from Europe. For the people living there, on the

other hand, this was a time of disaster. Not only Europeans, but

Arab slavers and almost equally ruthless ivory traders

rampaged across the continent, dragging off the natives for sale

abroad or conscripting them as porters. At the same time

warlike tribes such as the Ngoni from the south and the

Karamojong from the north, set in motion by other upheavals

beyond their homelands, migrated or raided into the region.

The local tribes of course fought back, and in the vast region

between the Congo River and the Indian Ocean all sorts of

different armies allied or clashed with each other in what must

have seemed at times like a gigantic multi-cornered fight. As if

this was not enough, some tribes - notably the Masai - kept

themselves busy with bloody civil wars.

The fighting was seldom over conventional territorial

objectives. For the European explorers, the ultimate goal might

be the unknown source of a river, or a semi-mythical lake or

mountain. The Arabs would be trying to collect enough slaves

or ivory to make the trip inland worthwhile, and then get their

cargo safely back to the coast. The native cattle-herding tribes

would be doing basically the same thing with other people's

cattle. Other native chiefs might aim to be recognised or

confirmed as a "divine" king (according to traditional African

notions of kingship), through a combination of material wealth

and success in battle. The farmers and hunters, on the other

hand, were strategically fairly passive - although they might try

to fight off slavers, or obstruct the passage of armies through

their territory - and would generally be happy if they remained

in control of the land they started with.

These rules, therefore, are based around the existence of a

number of different types of force, each composed of differing

proportions of the various types of troops available (with

acknowledgements to Peter Pig, who have used a similar

approach in their AK-47 Republic Modern rules). For game

purposes, I have reduced the enormous variety of real-life

troop-types to the following broad categories:

TROOP TYPES:

Europeans

Pretty obvious really. In this period

they are mostly explorers and big-

game hunters, rather than the

commanders of convent i onal

military expeditions. Armed with the

latest military or sporting guns,

practiced shots, convinced of their

absolute superiority over the

savages - and with nowhere to run

to if they don't stand and fight - they

are the most effective troops in the

game. However, they are only

available in very small numbers.

Askaris

Askari is an Arabic word meaning

soldier. For our purposes, it embraces all professional Arab

and African troops, armed with firearms of various types, and

having a reasonable amount of confidence in their ability to use

them. This includes Zanzibari and Sudanese slavers, and

native auxiliaries recruited and equipped by Europeans. Also

covered under this heading are the better equipped followers of

some native chiefs - such as the Ruga-Ruga employed by

warlords like Mirambo of the Nyamwezi tribe and his

contemporary Nyungu of the Kimbu - and professional slave

and ivory-traders like the pombeiros whom Livingstone

discovered operating along the upper Zambesi in the 1850s.

There are 2 sub-classes of Askaris, in addition to the standard

type:

Elite Askaris

Until the late 1860s,

these men will be dis-

tinguished mainly by

their better training

and morale. Thereaf-

ter, they might carry

breech-loading rifles

or repeating carbines

instead of the more

common muzzl e-

loaders. They will generally be a small minority of any force -

forming, for example, the bodyguards of Zanzibari leaders.

Baluchis

These were mercenaries, recruited mainly from the Indian

sub-continent, who were frequently found in the service of

the Zanzibaris. They continued to favour obsolete matchlock

muskets, backed up by sword and shield, and so are treated

here as less effective when firing, although better at hand-to-

hand combat, than standard Askaris.

Native Musketeers

Warriors from traditional African societies, armed with

firearms which were generally old-fashioned and badly-

maintained. These weapons had been supplied in very large

numbers over the preceding couple of centuries to native

agents of the ivory and slave trades. They were seldom,

however, used with any great skill. In warfare the noise they

made was often considered to be as important as any actual

damage they might do, and so ancient large-calibre muzzle-

loaders were often preferred, even when more modern

weapons were available. Ammunition was frequently

grapeshot made from nails, bits of pottery etc. (It was not

unknown for warriors to go to the trouble of filing off the rifling

from the insides of the barrels of modern rifles so that they

could be used to fire such improvised projectiles.)

Native Archers

The bow was less commonly used in warfare in the 19th

century than it had been formerly. This was at least partly due to

the prestige which had come to be attached to firearms,

although in fact skilled archers were often more effective than

their compatriots equipped with muskets which they had not

been trained to use properly. Some peoples - notably

pastoralists like the Masai - despised the bow, and restricted its

use to youths not yet qualified as warriors, and old men left to

guard the camp. However, some forest tribes who relied

heavily on hunting could still field numerous archers, many of

whom used poisoned arrows. There is 1 sub-class of this

category:

Pygmies

In the dense Congo rain forests, a few tribes of Pygmies still

lived as hunter-gatherers. They were exceptionally skilled in

fieldcraft and archery, and specialised in shooting poisoned

arrows from ambush. They usually preferred to avoid other

people, but in many cases had been lured or forced into a close

relationship with neighbouring farming tribes. The farmers

often thought of themselves as owning "their" Pygmies, but the

latter no doubt saw it differently. In fact, many other Africans

were secretly terrified of the deadly little hunters.

Native Spearmen

Other tribal warriors, whether armed with spears (by far the

most common) or other hand-to-hand weapons such as swords

and axes. Swords were popular in East Africa and areas under

Arab influence, but less so in the Congo. There are 2 sub-

classes, apart from standard Spearmen:

Agile Spearmen

The younger warriors of some pastoral or semi-pastoral

societies, whose lifestyle and training for war made them

exceptionally fleet of foot, and who were expected to prove

themselves in battle before they could progress to full adult

status within the tribe. Among some peoples, like the Masai,

this distinction was formalised by a traditional system of

organised age-classes, members of which fought together.

Warrior Spearmen

Comprising a small elite of the older, more experienced men in

most societies, but the bulk of the mature warriors of a few

notably warlike peoples, such as the Masai or Ngoni. These

men might be slightly less mobile than their juniors, but are

exceptionally deadly in close combat.

FORCE TYPES:

The above troop-types, in varying proportions, may be

combined into any of the following force types. Like the troop

categories they are necessarily over-simplified, but it should

be possible to fit most historical examples into one or other of

them. The numbers given are of course only suggestions, and

could for example be halved (or doubled!) depending on the

number of figures available. Relative strengths are intended to

produce a rough balance between the different forces, but this

depends on a lot of other factors (such as the terrain), and so

cannot be guaranteed.

European-led Expedition

In this period Europeans came to tropical Africa not so much as

conquerors as explorers, whether private or government-

backed. Some of them had a genuine (if usually misguided)

interest in helping the Africans, by spreading civilisation or

suppressing the slave trade. For others, the motive was

scientific curiosity, career advancement, or the desire to get

rich. They would not usually launch unprovoked attacks on

native forces, but would insist on going wherever they liked,

and would be inclined to take drastic action if this was

disputed. Sometimes they would intervene in local disputes.

British expeditions, in particular, might be under instructions

to attack slavers. Some explorers managed to avoid conflict

with the natives, while others - Stanley and Peters being among

the worst examples - fought their way ruthlessly through

anything resembling opposition. Expeditions could vary

greatly in size, but for our purposes a typical force looks like

this:

16 figures: 1 - 3 Europeans.

6 - 12 Askaris. (Up to 1/3 may

be Elite.)

0 - 8 Native Musketeers or

Archers.

0 - 8 Native Spearmen.

3 of the above figures are officers. At least 1 of them must be

European. Up to 2 may be Elite Askaris.

Arabs

During the 19th century, Arab expeditions penetrated East

Africa from two different directions. The Zanzibaris - heirs to

the Omani expansion down the coast which had replaced the

Portuguese - came from the east coast, while Egyptians and

Sudanese moved down from the north. The latter were often

referred to as Turks, because they came from areas which

had once been under the control of the Ottoman Sultans. The

Zanzibaris had a bad reputation as slave-raiders, although most

of their victims were in fact captured for them by native allies.

They also engaged in more legitimate trade, especially in ivory.

The "Turks" were even more rapacious, as they were mainly

interested in seizing recruits for the Egyptian army, and carried

no goods for peaceful trading. However, they seldom

penetrated further south than the north of what is now Uganda.

In their operations in the Sudan (both East and West) they often

relied on cavalry, but horses were unsuited to the tsetse-fly

infested regions of East and Central Africa, and so are not

catered for in these rules. Arab factions often fought not only

native peoples, but also each other. They were also at various

times allies and enemies of various European expeditions. A

notional force of this type will consist of:

32 figures: 12 - 24 Askaris. (Any may be

Baluchis. Up to 4 Askari

figures may be Elite.)

0 - 12 Native Musketeers.

0 - 4 Native Archers.

8 - 20 Native Spearmen.

4 Askari figures (of any sub-type) are officers.

Native Chiefdom

Some East African peoples were either already highly

organised under traditional rulers - like the Buganda of Lake

Victoria - or organised themselves in response to outside

influences - like the Nyamwezi in Tanzania, who made so

much profit from their employment as porters that they became

slave-owners themselves. Such people could afford fair

numbers of firearms, and often managed to look after

themselves quite well. This force represents both the

traditional chiefdoms, and the more ephemeral regimes of men

like Mirambo

and Nyungu.

T h e

a s ka r i s ,

particularly in

the latter type

o f f o r c e ,

would include

the colourful

Ruga-Ruga irregulars, whose discipline sometimes left

something to be desired, but who were full-time soldiers with

good weapon-handling skills:

44 figures: 8 - 16 Askaris.

8 - 16 Native Musketeers.

0 - 10 Native Archers.

8 - 16 Native Spearmen. (Up to

1/4 may be Warrior

Spearmen.)

5 Askari figures are officers.

Tribal Farmers

Many Africans - especially those far from the coast - still lived

in small farming communities, largely isolated from the great

trading routes, and so cut off from a supply of modern

Tribal Farmers

Many Africans - especially those far from the coast - still lived

in small farming communities, largely isolated from the great

trading routes, and so cut off from a supply of modern

weapons. In reality they seldom managed to resist

PAINTING GUIDE:

EXPLORERS

Early European explorers tended to wear clothes of a cut and

colour popular at home, or a specially made, often

idiosyncratic, travelling costume. Later a white or pale khaki

"uniform" with a tropical helmet or wide-brimmed hat became

the norm. Some of the more famous explorers were associated

with a particular costume:

Livingstone - a red smock and a blue peaked cap with a gold

band.

Baker - a loose smock and trousers, dyed in natural shades,

with a peaked cap with neckflap.

Speke - light brown trousers, a greenish tweed waistcoat with

many pockets, and a check shirt.

Stanley - a frogged jacket and curious hat of his own devising,

in a pale shade of khaki.

Flags - expeditions starting in Zanzibar usually carried the

Sultan's plain red flag, and often a national flag too.

ASKARIS

Skin - could vary from yellowish bronze to dark brown.

Askaris would not wear warpaint, although some would have

tribal scars.

Loincloths - most commonly off-white cotton, sometimes

dyed yellow-brown, indigo (all shades from blue-black to

faded denim) or white with a narrow reddish border. Other

more colourful fabrics included blue with a broad red stripe,

dark blue with a red or yellow border, multi-coloured checks

and sometimes plain red. In practice these best clothes would

be kept for special occasions, and everyday loincloths would

be ragged and stained.

Waistcoats - blue or red in imitation of the Zanzibaris.

Coats and Shirts - if worn at all, could represent a rudimentary

uniform eg the white coats with red or blue cuffs and a

matching 1' square between the shoulders worn by Imperial

British East Africa Company troops in 1890.

Hats - either fezzes and caps, in red or white, or turbans,

usually white.

BEARERS

Dressed more poorly than askaris in plain fabrics or animal

skins.

ZANZIBARI ARABS

Skin - varied, from olive to dark brown, with the number of

generations a family had been settled in East Africa.

Gown - a long shirt with full-length sleeves. Originally this

was a dull yellow, but by the 1870s was usually white, its

brightness increasing with status. At the waist there was

usually a sash, often white although any colour could be used.

A shorter shirt, in a striped or patterned fabric, was sometimes

worn over the gown.

Waistcoats and Jackets - dark blue or red zouave style with

contrasting edging and decoration.

Overmantles - in dark blue or red, worn by leaders.

Hats - white fezzes or turbans. Wealthier Arabs often used

multicoloured, striped silks for their turbans.

European or Arab incursions, but for the sake of game balance

we will give them a large enough force to stand a chance:

64 figures: 0 - 16 Native Musketeers.

0 - 24 Native Archers. (Up to

12 f i gur es may be

Pygmies.)

32 - 64 Native Spearmen. (Up to

1/4 may be Warrior

Spearmen.)

6 figures (not Pygmies) are officers.

Tribal Herdsmen

Some African societies in the drier savannah regionsrejected

farming, and lived mainly or exclusively from the products of

their cattle. They tended to be very warlike, conservative, and

convinced of their own superiority over both farmers and

hunters. In some cases they instituted a virtual reign of terror

over their neighbours, though in others the relationship was

more peaceful. The most famous example from East Africa is

the Masai, but similar herdsmen dominated much of the

southern Sudan. The Ngoni, who migrated into East Africa

from the south early in the 19th century and brought with them

a military system derived from that of the Zulus, may also be

placed in this category. A popular pastime among the warriors

of these tribes was stealing cattle, from the farmers or each

other. (According to Masai legend, all the cattle in the world

originally belonged to them, although some had been

temporarily misappropriated by lesser peoples. It was

obviously a warrior's duty to help return them to the fold.) They

fought very effectively against other traditional Africans, but

their rash courage, and their tendency to despise guns and

skirmishing tactics, made them terribly vulnerable to modern

firearms.

64 figures: 0 - 4 Native Archers.

60 - 64 Native Spearmen. (Up to

1/ 2 ma y be Agi l e

Spearmen, 1/5 to 3/4 are

Warrior Spearmen.)

6 Warrior Spearman figures are officers.

Tribal Hunters

By the 19th century, this ancient lifestyle survived only in a few

isolated pockets, which were too dry or too densely forested

for agriculture. Thus hunters were seldom troubled much by

slavers, being too few and too elusive to be worth chasing.

Most - though not all - of the specialist hunters were pygmies

living in the rainforests of the Congo. This type of force will be

quite effective in thick cover, but perhaps less useful

elsewhere:

48 figures if Pygmies; 60 if not:

All or none may be Pygmies. If Pygmy, all count as Pygmy

Native Archers. If not, up to 24 figures may be Native

Spearmen, and the rest standard Native Archers.

5 figures are officers if Pygmies, 6 if not.

Flags - a blood-red flag was the sign of a caravan from

Zanzibar, although the contingents of individual leaders

carried their own flags. These were probably simple vertical or

horizontal stripes in blue, red and white, although patterned

fabrics may have been used.

RUGA-RUGA

Clothing - a mixture of askari, Zanzibari and tribal styles. Red

cloaks were sometimes worn. Officers wore Zanzibari-style

white gowns with red or blue coats.

Hats - large turbans with feathers, feathered tribal headdresses

and probably fezzes.

Ornaments - hung with charms, lots of ivory bangles, brass or

copper wire around wrists and ankles.

CENTRAL AFRICAN TRIBES

Skin - from light to very dark brown, fairly uniform within a

particular tribe

Loincloths - animal skins, bark cloth (pale red-brown) and

later imported cloth.

Hair and Headgear - huge variety of hairstyles, which were

often the distinguishing feature of a tribe. Feathers could be

fixed in hair - ostrich feathers (long white and short black) in

East Africa, and parrot feathers (long crimson and short grey)

in the Congo basin. Feathers could also be attached to animal

skin or basketwork caps.

Warpaint - not always used, but when it was red and white

were the usual colours. Patterns usually involved painting

parts of the body in solid colours (eg white arms and legs or red

upper body). Sometimes the entire body could be painted, half

red and half white. A tribe might use a common style, but

would not be painted absolutely uniformly.

Shields - in East Africa, when used, were round or oval and

made of hide. They were often unpainted, although at least one

tribe painted theirs half red and half black. Any combination

of red, white and black is possible. In the damper Congo,

where hide was unavailable or would rot too fast, shields were

made of basketwork or light wood. Both types were

commonly painted black, either plain or with geometric

patterns left in the natural cane colour. Shields were held by a

central hand-grip.

Skirmish Rules and Campaign System to follow in

Part Two ....

Você também pode gostar

- In Darkest Africa (9) A Masai ArmyDocumento7 páginasIn Darkest Africa (9) A Masai ArmySpanishfuryAinda não há avaliações

- In Darkest Africa (8) Nyasaland I887 1895Documento6 páginasIn Darkest Africa (8) Nyasaland I887 1895Spanishfury100% (1)

- East Africa: Tribal and Imperial Armies in Uganda, Kenya, Tanzania and Zanzibar, 1800 to 1900No EverandEast Africa: Tribal and Imperial Armies in Uganda, Kenya, Tanzania and Zanzibar, 1800 to 1900Ainda não há avaliações

- In Darkest AfricaDocumento5 páginasIn Darkest AfricaSpanishfuryAinda não há avaliações

- The Armies of Rei BoubaDocumento6 páginasThe Armies of Rei BoubaFaustnikAinda não há avaliações

- 12 Groan of Thrones HOTT Army ListsDocumento7 páginas12 Groan of Thrones HOTT Army ListsTyler KusterAinda não há avaliações

- HoTE Colonials3Documento6 páginasHoTE Colonials3Blake RadetzkyAinda não há avaliações

- Hordes in The Trenches Version 2Documento10 páginasHordes in The Trenches Version 2John Donovan0% (1)

- Sun King 17thDocumento20 páginasSun King 17thVaggelisAinda não há avaliações

- THE TARASCAN ARMY OF THE CONQUESTDocumento11 páginasTHE TARASCAN ARMY OF THE CONQUESTArespon Caballero Herrera100% (1)

- Normans of Sicily Army ListDocumento3 páginasNormans of Sicily Army Listrobert franz100% (1)

- Flintloque Journals of Valon JOV01 Tuscan ElvesDocumento1 páginaFlintloque Journals of Valon JOV01 Tuscan Elvesjasc0_hotmail_itAinda não há avaliações

- Shako and Musket 1815Documento16 páginasShako and Musket 1815airfix1999Ainda não há avaliações

- OHW – House Rules and Unit StatsDocumento5 páginasOHW – House Rules and Unit StatsIan100% (1)

- Part One: Gun & SpearDocumento14 páginasPart One: Gun & Spearbinkyfish100% (1)

- DBA3 House Rules - A Personal VersionDocumento4 páginasDBA3 House Rules - A Personal VersionJames FlywheelAinda não há avaliações

- United Provinces V2Documento8 páginasUnited Provinces V2UnluckyGeneralAinda não há avaliações

- DBSA Fast Play RulesDocumento3 páginasDBSA Fast Play RulesHarold_GodwinsonAinda não há avaliações

- Seven SamuraiDocumento6 páginasSeven SamuraiMagnus JohanssonAinda não há avaliações

- Successors Army List Basic ImpetusDocumento2 páginasSuccessors Army List Basic ImpetusduguqiubaiAinda não há avaliações

- Hoplomachia ListsDocumento41 páginasHoplomachia ListsVaggelis100% (5)

- Kiss Blitzkrieg PDFDocumento4 páginasKiss Blitzkrieg PDFA Jeff ButlerAinda não há avaliações

- New Armati Army Lists2Documento15 páginasNew Armati Army Lists2junkyardbcnAinda não há avaliações

- CaliverDocumento12 páginasCaliverTakedaVasiljevicIgorAinda não há avaliações

- (Wab) Successor Empire Armies (265-46 BC) - Jeff JonasDocumento8 páginas(Wab) Successor Empire Armies (265-46 BC) - Jeff JonasLawrence WiddicombeAinda não há avaliações

- WAB 100 Years WarDocumento20 páginasWAB 100 Years WarThe Rude1Ainda não há avaliações

- DBA Book 1Documento19 páginasDBA Book 1JoseSilvaLeite0% (1)

- Trench Assault: The Race To The Parapet 1916Documento4 páginasTrench Assault: The Race To The Parapet 1916Joshua ReyesAinda não há avaliações

- Hordes in The Trenches Version 2Documento10 páginasHordes in The Trenches Version 2A Jeff ButlerAinda não há avaliações

- Wilson's Last StandDocumento4 páginasWilson's Last StandFaustnikAinda não há avaliações

- SAND5Documento2 páginasSAND5Kevin LepleyAinda não há avaliações

- 2 by 2 Napoleonic's 2LrvhDocumento11 páginas2 by 2 Napoleonic's 2LrvhjohnAinda não há avaliações

- Lions LammentDocumento5 páginasLions LammentPeterBrown100% (1)

- Tricorn 1690Documento27 páginasTricorn 1690doorman46100% (1)

- Distinctive Features of Ila Warriors in Death on the Dark ContinentDocumento2 páginasDistinctive Features of Ila Warriors in Death on the Dark Continentgrimsi_groggsAinda não há avaliações

- GLC - "El Hombre, Sin Nombre"Documento6 páginasGLC - "El Hombre, Sin Nombre"Pete GillAinda não há avaliações

- Solo Coioniai - Ii: by Mark R. ElwenDocumento4 páginasSolo Coioniai - Ii: by Mark R. ElwenFranck Yeghicheyan100% (2)

- Ten Rounds Rapid Basics PDFDocumento21 páginasTen Rounds Rapid Basics PDFJames Tiberius HenkelAinda não há avaliações

- Div Tac: Playing RulesDocumento11 páginasDiv Tac: Playing RulesVinny CarpenterAinda não há avaliações

- Old Trousers Ii: Battalion Level Napoleonic WarfareDocumento37 páginasOld Trousers Ii: Battalion Level Napoleonic WarfareNigel WhitmoreAinda não há avaliações

- Rules Clarifications Part 1: AW vs MW DifferencesDocumento20 páginasRules Clarifications Part 1: AW vs MW DifferencesTSEvansAinda não há avaliações

- Shako 1812Documento15 páginasShako 1812Dalibor DobrilovicAinda não há avaliações

- Pikemen RampantDocumento7 páginasPikemen RampantPeterBrownAinda não há avaliações

- Bohemian Revolt-Army ListsDocumento9 páginasBohemian Revolt-Army Listsaffe240% (1)

- Scenarıos To Tercıos Volume I Travlos DRAFTDocumento36 páginasScenarıos To Tercıos Volume I Travlos DRAFTGiorgio Briozzo100% (1)

- Ottoman ListDocumento3 páginasOttoman ListmisfirekkAinda não há avaliações

- De Bellis Fictionalis - Tolkien Army ListsDocumento40 páginasDe Bellis Fictionalis - Tolkien Army ListsNeill HendersonAinda não há avaliações

- To The Strongest Army Lists - Kingdoms of The EastDocumento55 páginasTo The Strongest Army Lists - Kingdoms of The EastMiguel Angel Martinez FernandezAinda não há avaliações

- Battleplan Magazine 7Documento72 páginasBattleplan Magazine 7jmw082Ainda não há avaliações

- Comfortable War Gaming: Reflections From An Old Timer': (Part The First) by Stuart AsquithDocumento9 páginasComfortable War Gaming: Reflections From An Old Timer': (Part The First) by Stuart AsquithMauricio Miranda AlbarranAinda não há avaliações

- Sand!: by Ray TrochimDocumento2 páginasSand!: by Ray TrochimKevin LepleyAinda não há avaliações

- d3h2 DBA Hott FusionDocumento18 páginasd3h2 DBA Hott FusionNeill Henderson100% (1)

- The Wargame by Charles GrantDocumento6 páginasThe Wargame by Charles GrantA Jeff Butler100% (3)

- Warhammer Ancient Battles Chariot Wars Updated 30 Oct 2012Documento51 páginasWarhammer Ancient Battles Chariot Wars Updated 30 Oct 2012RiccardoCiliberti100% (1)

- Thermopylae: Defend the Pass as a Spartan in this Solo WargameDocumento6 páginasThermopylae: Defend the Pass as a Spartan in this Solo WargameazzAinda não há avaliações

- French Basing Convention V1Documento4 páginasFrench Basing Convention V1UnluckyGeneralAinda não há avaliações

- Warmaster Nippon Trial RulesDocumento5 páginasWarmaster Nippon Trial RuleslardieladAinda não há avaliações

- DBRDocumento143 páginasDBRsdkfz259Ainda não há avaliações

- Hot TrodDocumento28 páginasHot TrodSpanishfuryAinda não há avaliações

- WWII DBA Guide Provides Rules for Miniatures BattlesDocumento18 páginasWWII DBA Guide Provides Rules for Miniatures BattlesJoseSilvaLeiteAinda não há avaliações

- Ot NavalDocumento19 páginasOt NavalSpanishfuryAinda não há avaliações

- Saving The GunsDocumento8 páginasSaving The GunsSpanishfuryAinda não há avaliações

- Valiant Britons: Tribal Warfare in Celtic BritainDocumento11 páginasValiant Britons: Tribal Warfare in Celtic BritainSpanishfuryAinda não há avaliações

- YUTY CardsDocumento1 páginaYUTY CardsSpanishfuryAinda não há avaliações

- Hot TrodDocumento28 páginasHot TrodSpanishfuryAinda não há avaliações

- PhalanxDocumento37 páginasPhalanxSpanishfuryAinda não há avaliações

- Foreign DevilsDocumento4 páginasForeign DevilsSpanishfuryAinda não há avaliações

- Braves GensDocumento9 páginasBraves GensSpanishfuryAinda não há avaliações

- Border Reiver War RulesDocumento11 páginasBorder Reiver War RulesSpanishfuryAinda não há avaliações

- Buffalo SoldiersDocumento4 páginasBuffalo SoldiersSpanishfuryAinda não há avaliações

- East Africa WW1Documento5 páginasEast Africa WW1SpanishfuryAinda não há avaliações

- PhalanxDocumento37 páginasPhalanxSpanishfuryAinda não há avaliações

- Shipka Pass, 1877 (Solo Game)Documento3 páginasShipka Pass, 1877 (Solo Game)SpanishfuryAinda não há avaliações

- Alma Zouaves: Aperitif Crimean Scenarios For Belle Epoque by Pierre LaporteDocumento6 páginasAlma Zouaves: Aperitif Crimean Scenarios For Belle Epoque by Pierre LaporteSpanishfuryAinda não há avaliações

- RCWDocumento15 páginasRCWSpanishfuryAinda não há avaliações

- In Darkest AfricaDocumento6 páginasIn Darkest AfricaSpanishfuryAinda não há avaliações

- Belle Epoque Aperitif GameDocumento6 páginasBelle Epoque Aperitif GameSpanishfuryAinda não há avaliações

- YUTY CardsDocumento1 páginaYUTY CardsSpanishfuryAinda não há avaliações

- In Darkest AfricaDocumento7 páginasIn Darkest AfricaSpanishfury100% (1)

- "Abomey, 1892" (Solo Game) : : Even When Leaving Rough TerrainDocumento4 páginas"Abomey, 1892" (Solo Game) : : Even When Leaving Rough TerrainSpanishfuryAinda não há avaliações

- Big Table Little MenDocumento28 páginasBig Table Little MenSpanishfuryAinda não há avaliações

- Russian Civil War Army Lists IIDocumento55 páginasRussian Civil War Army Lists IISpanishfuryAinda não há avaliações

- Napoleonic DBA RulesDocumento3 páginasNapoleonic DBA RulesSpanishfuryAinda não há avaliações

- Rough Wooing Early 16th Century RulesDocumento7 páginasRough Wooing Early 16th Century RulesJoshua ReyesAinda não há avaliações

- In Darkest Africa (7) Nyasaland 1887 1895Documento8 páginasIn Darkest Africa (7) Nyasaland 1887 1895Spanishfury100% (1)

- In Darkest AfricaDocumento6 páginasIn Darkest AfricaSpanishfuryAinda não há avaliações

- Instagram Dan Buli Siber Dalam Kalangan Remaja Di Malaysia: Jasmyn Tan YuxuanDocumento13 páginasInstagram Dan Buli Siber Dalam Kalangan Remaja Di Malaysia: Jasmyn Tan YuxuanXiu Jiuan SimAinda não há avaliações

- Bluetooth Home Automation Using ArduinoDocumento25 páginasBluetooth Home Automation Using ArduinoRabiAinda não há avaliações

- DSE61xx Configuration Suite Software Manual PDFDocumento60 páginasDSE61xx Configuration Suite Software Manual PDFluisAinda não há avaliações

- Product CycleDocumento2 páginasProduct CycleoldinaAinda não há avaliações

- Emergency Room Delivery RecordDocumento7 páginasEmergency Room Delivery RecordMariel VillamorAinda não há avaliações

- Identifying The TopicDocumento2 páginasIdentifying The TopicrioAinda não há avaliações

- Key formulas for introductory statisticsDocumento8 páginasKey formulas for introductory statisticsimam awaluddinAinda não há avaliações

- Practice Like-Love - Hate and PronounsDocumento3 páginasPractice Like-Love - Hate and PronounsangelinarojascnAinda não há avaliações

- Job Description Support Worker Level 1Documento4 páginasJob Description Support Worker Level 1Damilola IsahAinda não há avaliações

- Environmental Technology Syllabus-2019Documento2 páginasEnvironmental Technology Syllabus-2019Kxsns sjidAinda não há avaliações

- WhatsoldDocumento141 páginasWhatsoldLuciana KarajalloAinda não há avaliações

- IELTS Vocabulary ExpectationDocumento3 páginasIELTS Vocabulary ExpectationPham Ba DatAinda não há avaliações

- A General Guide To Camera Trapping Large Mammals in Tropical Rainforests With Particula PDFDocumento37 páginasA General Guide To Camera Trapping Large Mammals in Tropical Rainforests With Particula PDFDiego JesusAinda não há avaliações

- Health Education and Health PromotionDocumento4 páginasHealth Education and Health PromotionRamela Mae SalvatierraAinda não há avaliações

- Quiz-Travel - Beginner (A1)Documento4 páginasQuiz-Travel - Beginner (A1)Carlos Alberto Rodriguez LazoAinda não há avaliações

- Machine Spindle Noses: 6 Bison - Bial S. ADocumento2 páginasMachine Spindle Noses: 6 Bison - Bial S. AshanehatfieldAinda não há avaliações

- Vehicle Registration Renewal Form DetailsDocumento1 páginaVehicle Registration Renewal Form Detailsabe lincolnAinda não há avaliações

- Artificial IseminationDocumento6 páginasArtificial IseminationHafiz Muhammad Zain-Ul AbedinAinda não há avaliações

- English Week3 PDFDocumento4 páginasEnglish Week3 PDFLucky GeminaAinda não há avaliações

- Positioning for competitive advantageDocumento9 páginasPositioning for competitive advantageOnos Bunny BenjaminAinda não há avaliações

- Single-Phase Induction Generators PDFDocumento11 páginasSingle-Phase Induction Generators PDFalokinxx100% (1)

- Piping MaterialDocumento45 páginasPiping MaterialLcm TnlAinda não há avaliações

- Reservoir Rock TypingDocumento56 páginasReservoir Rock TypingAffan HasanAinda não há avaliações

- Easa Ad Us-2017-09-04 1Documento7 páginasEasa Ad Us-2017-09-04 1Jose Miguel Atehortua ArenasAinda não há avaliações

- The Product Development and Commercialization ProcDocumento2 páginasThe Product Development and Commercialization ProcAlexandra LicaAinda não há avaliações

- 2.4 Avogadro's Hypothesis+ Equivalent MassesDocumento12 páginas2.4 Avogadro's Hypothesis+ Equivalent MassesSantosh MandalAinda não há avaliações

- 5 Dec2021-AWS Command Line Interface - User GuideDocumento215 páginas5 Dec2021-AWS Command Line Interface - User GuideshikhaxohebkhanAinda não há avaliações

- S2 Retake Practice Exam PDFDocumento3 páginasS2 Retake Practice Exam PDFWinnie MeiAinda não há avaliações

- Emerson Park Master Plan 2015 DraftDocumento93 páginasEmerson Park Master Plan 2015 DraftRyan DeffenbaughAinda não há avaliações

- Wacker Neuson RTDocumento120 páginasWacker Neuson RTJANUSZ2017100% (4)