Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Labor Relations Cases

Enviado por

Rcl ClaireDescrição original:

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Labor Relations Cases

Enviado por

Rcl ClaireDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

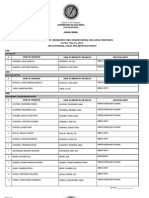

Republic of the Philippines

SUPREME COURT

Manila

FIRST DIVISION

G.R. No. 75321 June 20, 1988

ASSOCIATED TRADE UNIONS (ATU), petitioner,

vs.

HON. CRESENCIO B. TRAJANO, in his capacity as Director of the Bureau of

Labor Relations, MOLE, BALIWAG TRANSIT, INC. and TRADE UNIONS OF THE

PHILIPPINES AND ALLIED SERVICES (TUPAS)-WFTU, respondents.

Puerto, Nunez & Associates for petitioner.

Tupaz and Associates for respondent Union.

Jose C. Espinas collaborating counsel for private respondent.

Agapito S. Mendoza for respondent Baliwag Transit, Inc.

The Solicitor General for public respondent.

CRUZ .J,:

The resolution of this case has been simplified because it has been, in Justice Vicente

Abad Santos's felicitous phrase, "overtaken by events."

This case arose when on March 25, 1986, the private respondent union (TUPAS) filed

with the Malolos labor office of the MOLE a petition for certification election at the

Baliwag Transit, Inc. among its rank-and-file workers. 1 Despite opposition from the

herein petitioner, Associated Trade Unions (ATU), the petition was granted by the

med-arbiter on May 14, 1986, and a certification election was ordered "to determine

the exclusive bargaining agent (of the workers) for purposes of collective bargaining

with respect to (their) terms and conditions of employment." 2 On appeal, this order

was sustained by the respondent Director of Labor Relations in his order dated June

20, 1986, which he affirmed in his order of July 17, 1986, denying the motion for

reconsideration. 3 ATU then came to this Court claiming that the said orders are

tainted with grave abuse of discretion and so should be reversed. On August 20, 1986,

we issued a temporary restraining order that has maintained the status quo among the

parties. 4

In support of its petition, ATU claims that the private respondent's petition for

certification election is defective because (1) at the time it was filed, it did not contain

the signatures of 30% of the workers, to signify their consent to the certification

election; and (2) it was not allowed under the contract-bar rule because a new

collective bargaining agreement had been entered into by ATU with the company on

April 1, 1986. 5

TUPAS for its part, supported by the Solicitor General, contends that the 30% consent

requirement has been substantially complied with, the workers' signatures having

been subsequently submitted and admitted. As for the contract-bar rule, its position is

that the collective bargaining agreement, besides being vitiated by certain procedural

defects, was concluded by ATU with the management only on April 1, 1986 after the

filing of the petition for certification election on March 25, 1986. 6

This initial sparring was followed by a spirited exchange of views among the parties

which insofar as the first issue is concerned has become at best only academic now.

The reason is that the 30% consent required under then Section 258 of the Labor Code

is no longer in force owing to the amendment of this section by Executive Order No.

111, which became effective on March 4, 1987.

As revised by the said executive order, the pertinent articles of the Labor Code now

read as follows:

Art. 256. Representation issue in organized establishments. In organized

establishments, when a petition questioning the majority status of the incumbent

bargaining agent is filed before the Ministry within the sixty-day period before the

expiration of the collective bargaining agreement, the Med-Arbiter shall automatically

order an election by secret ballot to ascertain the will of the employees in the

appropriate bargaining unit. To have a valid election, at least a majority of all eligible

voters in the unit must have cast their votes. The labor union receiving the majority of

the valid votes cast shall be certified as the exclusive bargaining agent of all the

workers in the unit. When an election which provides for three or more choices results

in no choice receiving a majority of the valid votes cast, a runoff election shall be

conducted between the choices receiving the two highest number of votes.

Art. 257. Petitions in unorganized establishments. In any establishment where there

is no certified bargaining agent, the petition for certification election filed by a

legitimate labor organization shall be supported by the written consent of at least

twenty (20%) percent of all the employees in the bargaining unit. Upon receipt and

verification of such petition, the Med-Arbiter shall automatically order the conduct of a

certification election.

The applicable provision in the case at bar is Article 256 because Baliwag transit, Inc.

is an organized establishment. Under this provision, the petition for certification

election need no longer carry the signatures of the 30% of the workers consenting to

such petition as originally required under Article 258. The present rule provides that as

long as the petition contains the matters 7 required in Section 2, Rule 5, Book V of the

Implementing Rules and Regulations, as amended by Section 6, Implementing Rules of

E.O. No. 111, the med-arbiter "shall automatically order" an election by secret ballot

"to ascertain the will of the employees in the appropriate bargaining unit." The consent

requirement is now applied only to unorganized establishments under Article 257, and

at that, significantly, has been reduced to only 20%.

The petition must also fail on the second issue which is based on the contract-bar rule

under Section 3, Rule 5, Book V of the Implementing Rules and Regulations. This rule

simply provides that a petition for certification election or a motion for intervention can

only be entertained within sixty days prior to the expiry date of an existing collective

bargaining agreement. Otherwise put, the rule prohibits the filing of a petition for

certification election during the existence of a collective bargaining agreement except

within the freedom period, as it is called, when the said agreement is about to expire.

The purpose, obviously, is to ensure stability in the relationships of the workers and

the management by preventing frequent modifications of any collective bargaining

agreement earlier entered into by them in good faith and for the stipulated original

period.

ATU insists that its collective bargaining agreement concluded by it with Baliwag

Transit, Inc, on April 1, 1986, should bar the certification election sought by TUPAS as

this would disturb the said new agreement. Moreover, the agreement had been ratified

on April 3, 1986, by a majority of the workers and is plainly beneficial to them because

of the many generous concessions made by the management. 8

Besides pointing out that its petition for certification election was filed within the

freedom period and five days before the new collective bargaining agreement was

concluded by ATU with Baliwag Transit, Inc. TUPAS contends that the said agreement

suffers from certain fatal procedural flaws. Specifically, the CBA was not posted for at

least five days in two conspicuous places in the establishment before ratification, to

enable the workers to clearly inform themselves of its provisions. Moreover, the CBA

submitted to the MOLE did not carry the sworn statement of the union secretary,

attested by the union president, that the CBA had been duly posted and ratified, as

required by Section 1, Rule 9, Book V of the Implementing Rules and Regulations.

These requirements being mandatory, non-compliance therewith rendered the said

CBA ineffective. 9

The Court will not rule on the merits and/or defects of the new CBA and shall only

consider the fact that it was entered into at a time when the petition for certification

election had already been filed by TUPAS and was then pending resolution. The said

CBA cannot be deemed permanent, precluding the commencement of negotiations by

another union with the management. In the meantime however, so as not to deprive

the workers of the benefits of the said agreement, it shall be recognized and given

effect on a temporary basis, subject to the results of the certification election. The

agreement may be continued in force if ATU is certified as the exclusive bargaining

representative of the workers or may be rejected and replaced in the event that TUPAS

emerges as the winner.

This ruling is consistent with our earlier decisions on interim arrangements of this kind

where we declared:

... we are not unmindful that the supplemental collective bargaining contract, entered

into in the meanwhile between management and respondent Union contains provisions

beneficial to labor. So as not to prejudice the workers involved, it must be made clear

that until the conclusion of a new collective bargaining contract entered into by it and

whatever labor organization may be chosen after the certification election, the existing

labor contract as thus supplemented should be left undisturbed. Its terms call for strict

compliance. This mode of assuring that the cause of labor suffers no injury from the

struggle between contending labor organization follows the doctrine announced in the

recent case of Vassar Industries Employees v. Estrella (L-46562, March 31, 1978). To

quote from the opinion. "In the meanwhile, if as contended by private respondent

labor union the interim collective bargaining agreement which it engineered and

entered into on September 26, 1977 has, much more favorable terms for the workers

of private respondent Vassar Industries, then it should continue in full force and effect

until the appropriate bargaining representative is chosen and negotiations for a new

collective bargaining agreement thereafter concluded." 10

It remains for the Court to reiterate that the certification election is the most

democratic forum for the articulation by the workers of their choice of the union that

shall act on their behalf in the negotiation of a collective bargaining agreement with

their employer. Exercising their suffrage through the medium of the secret ballot, they

can select the exclusive bargaining representative that, emboldened by their

confidence and strengthened by their support shall fight for their rights at the

conference table. That is how union solidarity is achieved and union power is increased

in the free society. Hence, rather than being inhibited and delayed, the certification

election should be given every encouragement under the law, that the will of the

workers may be discovered and, through their freely chosen representatives, pursued

and realized.

WHEREFORE, the petition is DENIED. The temporary restraining order of August 20,

1986, is LIFTED. Cost against the petitioner.

SO ORDERED.

Republic of the Philippines

SUPREME COURT

Manila

FIRST DIVISION

G.R. No. 85085 November 6, 1989

ASSOCIATED LABOR UNIONS (ALU), petitioner,

vs.

HON. PURA FERRER-CALLEJA, DIRECTOR, BUREAU OF LABOR RELATIONS,

DEPARTMENT OF LABOR AND EMPLOYMENT, NATIONAL FEDERATION OF

LABOR UNIONS (NAFLU), respondents.

GANCAYCO, J.:

Is the contract bar rule applicable where a collective bargaining agreement was hastily

concluded in defiance of the order of the med-arbiter enjoining the parties from

entering into a CBA until the issue on representation is finally resolved? This is the

primary issue in this special civil action for certiorari.

The Philippine Associated Smelting and Refining Corporation (PASAR) is a corporation

established and existing pursuant to Philippine laws and is engaged in the manufacture

and processing of copper cathodes with a plant operating in Isabel, Leyte. It employs

more or less eight hundred fifty (850) rank-and-file employees in its departments.

Petitioner Associated Labor Union (ALU) had a collective bargaining agreement (CBA)

with PASAR which expired on April 1, 1987. Several days before the expiration of the

said CBA or on March 23, 1987, private respondent National Federation of Labor

Unions (NAFLU) filed a petition for certification election with the Bureau of Labor

Relations Regional Office in Tacloban City docketed as MED-ARB-RO VII Case No. 3-

28-87, alleging, among others, that no certification election had been held in PASAR

within twelve (12) months immediately preceding the filing of the said petition.

Petitioner moved to intervene and sought the dismissal of the petition on the ground

that NAFLU failed to present the necessary signatures in support of its petition. In the

order dated April 21, 1987, 1 Med-Arbiter Bienvenido C. Elorcha dismissed the

petition. However, the order of dismissal was set aside in another order dated May 8,

1987 and the case was rescheduled for hearing on May 29, 1987. The said order

likewise enjoined PASAR from entering into a collective bargaining agreement with any

union until after the issue of representation is finally resolved. In the order dated June

1, 1987, 2 the petition for certification was dismissed for failure of NAFLU to solicit

20"7c of the total number of rank and file employees while ALU submitted 33 pages

containing the signatures of 88.5% of the rank and file employees at PASAR.

Private respondent appealed the order of dismissal to the Bureau of Labor Relations.

While the appeal was pending, petitioner ALU concluded negotiations with PASAR on

the proposed CBA. On July 24, 1987, copies of the newly concluded CBA were posted

in four (4) conspicuous places in the company premises. The said CBA was ratified by

the members of the bargaining unit on July 28, 1987. 3 Thereafter, petitioner ALU

moved for the dismissal of the appeal alleging that it had just concluded a CBA with

PASAR and that the said CBA had been ratified by 98% of the regular rank-and-file

employees and that at least 75 of NAFLU's members renounced their membership

thereat and affirmed membership with PEA-ALU in separate affidavits.

In a resolution dated September 30, 1987, the public respondent gave due course to

the appeal by ordering the conduct of a certification election among the rank-and-file

employees of PASAR with ALU, NAFLU and no union as choices, and denied petitioner

's motion to dismiss. 4

Both parties moved for reconsideration of the said resolution. However, both motions

were denied by public respondent in the order dated April 22, 1988.

Hence, the present petition. 5

The petition is anchored on the argument that the holding of certification elections in

organized establishments is mandated only where a petition is filed questioning the

majority status of the incumbent union and that it is only after due hearing where it is

established that the union claiming the majority status in the bargaining unit has

indeed a considerable support that a certification election should be ordered,

otherwise, the petition should be summarily dismissed. 6 Petitioner adds that public

respondent missed the legal intent of Article 257 of the Labor Code as amended by

Executive Order No. 111. 7

In effect, petitioner is of the view that Article 257 of the Labor Code which requires the

signature of at least 20% of the total number of rank-and-file employees should be

applied in the case at bar.

The petition is devoid of merit.

As it has been ruled in a long line of decisions, 8 a certification proceedings is not a

litigation in the sense that the term is ordinarily understood, but an investigation of a

non-adversarial and fact-finding character. As such, it is not covered by the technical

rules of evidence. Thus, as provided under Article 221 of the Labor Code, proceedings

before the National Labor Relations Commission (NLRC) are not covered by the

technical rules of procedure and evidence. The Court had previously construed Article

221 as to allow the NLRC or the labor arbiter to decide the case on the basis of

position papers and other documents submitted without resorting to technical rules of

evidence as observed in regular courts of justice. 9

On the other hand, Article 257 is applicable only to unorganized labor organizations

and not to establishments like PASAR where there exists a certified bargaining agent,

petitioner ALU, which as the record shows had previously entered into a CBA with the

management. This could be discerned from the clear intent of the law which provides

that

ART. 257. Petitions in unorganized establishments. In any

establishment where there is no certified bargaining agent, the

petition for certification election filed by a legitimate labor

organization shall be supported by the written consent of at least

twenty per cent (20%) of all the employees in the bargaining unit.

Upon receipt and verification of such petition, the Med-Arbiter shall

automatically order the conduct of a certification election.

Said article traverses the claim of the petitioner that in this case there is a need for a

considerable support of the rank-and-file employees in order that a certification

election may be ordered. Nowhere in the said provision does it require that the petition

in organized establishment should be accompanied by the written consent of at least

twenty percent (20%) of the employees of the bargaining unit concerned much less a

requirement that the petition be supported by the majority of the rank-and-file

employees. As above stated, Article 257 is applicable only to unorganized

establishments.

The Court reiterates that in cases of organized establishments where there exists a

certified bargaining agent, what is essential is whether the petition for certification

election wasfiled within the sixty-day freedom period. Article 256 of the Labor Code, as

amended by Executive Order No. 111, provides:

ART. 256. Representation issue in organized establishments. In

organized establishments, when a petition questioning the majority

status of the incumbent bargaining agent is filed before the

Department within the sixty-day period before the expiration of the

collective bargaining agreement, the Med-Arbiter shall automatically

order an election by secret ballot to ascertain the will of the

employees in the appropriate bargaining unit. To have a valid

election, at least a majority of all eligible voters in the unit must

have cast their votes. The labor union receiving the majority of the

valid votes cast shall be certified as the exclusive bargaining agent of

all the workers in the unit. When an election which provides for three

or more choices results in no choice receiving a majority of the valid

votes cast, a run-off election shall be conducted between the choices

receiving the two highest number of votes.

Article 256 is clear and leaves no room for interpretation. The mere filing of a petition

for certification election within the freedom period is sufficient basis for the respondent

Director to order the holding of a certification election.

Was the petition filed by NAFLU instituted within the freedom period? The record

speaks for itself. The previous CBA entered into by petitioner ALU was due to expire on

April 1, 1987. The petition for certification was filed by NAFLU on March 23, 1987, well

within the freedom period.

The contract bar rule is applicable only where the petition for certification election was

filed either before or after the freedom period. Petitioner, however, contends that since

the new CBA had already been ratified overwhelmingly by the members of the

bargaining unit and that said CBA had already been consummated and the members of

the bargaining unit have been continuously enjoying the benefits under the said CBA,

no certification election may be conducted, 10 citing, Foamtex Labor Union-TUPAS vs.

Noriel, 11 and Trade Unions of the Phil. and Allied Services vs. Inciong. 12

The reliance on the aforementioned cases is misplaced. In Foamtex the petition for

certiorari questioning the validity of the order of the Director of Labor Relations which

in turn affirmed the order of the Med-Arbiter calling for a certification election was

dismissed by the Court on the ground that although a new CBA was concluded

between the petitioner and the management, only a certified CBA would serve as a bar

to the holding of a certification election, citing Article 232 of the Labor Code.

Foamtex weakens rather than strengthens petitioner's stand. As pointed out by public

respondent, the new CBA entered into between petitioner on one hand and by the

management on the other has not been certified as yet by the Bureau of Labor

Relations.

There is an appreciable difference in Trade Unions of the Phil. and Allied Services

(TUPAS for short). Here, as in Foamtex the CBA was not yet certified and yet the Court

affirmed the order of the Director of the Bureau of Labor Relations which dismissed the

petition for certification election filed by the labor union. In TUPAS, the dismissal of the

petition for certification, was based on the fact that the contending union had a clear

majority of the workers concerned since out of 641 of the total working force, the said

union had 499 who did not only ratify the CBA concluded between the said union and

the management but also affirmed their membership in the said union so that

apparently petitioners therein did not have the support of 30% of all the employees of

the bargaining unit.

Nevertheless, even assuming for the sake of argument that the petitioner herein has

the majority of the rank-and-file employees and that some members of the NAFLU

even renounced their membership thereat and affirmed membership with the

petitioner, We cannot, however, apply TUPAS in the case at bar. Unlike in the case of

herein petitioner, in TUPAS, the petition for certification election was filed nineteen

(19) days after the CBA was signed which was well beyond the freedom period.

On the other hand, as earlier mentioned, the petition for certification election in this

case was filed within the freedom period but the petitioner and PASAR hastily

concluded a CBA despite the order of the Med-Arbiter enjoining them from doing so

until the issue of representation is finally resolved. As pointed out by public respondent

in its comment, 13 the parties were in bad faith when they concluded the CBA. Their

act was clearly intended to bar the petition for certification election filed by NAFLU. A

collective bargaining agreement which was prematurely renewed is not a bar to the

holding of a certification election. 14 Such indecent haste in renewing the CBA despite

an order enjoining them from doing so 15 is designed to frustrate the constitutional

right of the employees to self-organization. 16 Moreover, We cannot countenance the

actuation of the petitioner and the management in this case which is not conducive to

industrial peace.

The renewed CBA cannot constitute a bar to the instant petition for certification

election for the very reason that the same was not yet in existence when the said

petition was filed. 17 The holding of a certification election is a statutory policy that

should not be circumvented. 18

Petitioner posits the view that to grant the petition for certification election would open

the floodgates to unbridled and scrupulous petitions the objective of which is to

prejudice the industrial peace and stability existing in the company.

This Court believes otherwise. Our established jurisprudence adheres to the policy of

enhancing the welfare of the workers. Their freedom to choose who should be their

bargaining representative is of paramount importance. The fact that there already

exists a bargaining representative in the unit concerned is of no moment as long as

the petition for certification was filed within the freedom period. What is imperative is

that by such a petition for certification election the employees are given the

opportunity to make known who shall have the right to represent them thereafter. Not

only some but all of them should have the right to do so. 19 Petitioner's contention

that it has the support of the majority is immaterial. What is equally important is that

everyone be given a democratic space in the bargaining unit concerned. Time and

again, We have reiterated that the most effective way of determining which labor

organization can truly represent the working force is by certification election. 20

Finally, petitioner insists that to allow a certification election to be conducted will

promote divisiveness and eventually cause polarization of the members of the

bargaining unit at the expense of national interest. 21

The claim is bereft of merit. Petitioner failed to establish that the calling of certification

election will be prejudicial to the employees concerned and/or to the national interest.

The fear perceived by the petitioner is more imaginary than real. If it is true, as

pointed out by the petitioner, that it has the support of more than the majority and

that there was even a bigger number of members of NAFLU who affirmed their

membership to petitioner-union, then We see no reason why petitioner should be

apprehensive over the issue. If their claim is true, then most likely the conduct of a

certification election will strengthen their hold as any doubt will be erased thereby.

With the resolution of such doubts, fragmentation of the bargaining unit will be

avoided, and hence coherence among the workers will likely follow.

Petitioner's claim that the holding of a certification election will be inimical to the

national interest is far fetched. The workers are at peace with one another and their

working condition is smooth. There has been no stoppage of work or an occurrence of

a strike. With these facts on hand, to order otherwise will be repugnant to the well-

entrenched right of the workers to unionism.

WHEREFORE, premises considered, the instant petition is DISMISSED for lack of merit.

The temporary restraining order issued by the Court in the resolution dated October

10, 1988 22 is hereby lifted. This decision is immediately executory. No costs.

SO ORDERED.

SECOND DIVISION

[G.R. No. 146728. February 11, 2004]

GENERAL MILLING CORPORATION, petitioner, vs. HON. COURT OF APPEALS,

GENERAL MILLING CORPORATION INDEPENDENT LABOR UNION (GMC-ILU),

and RITO MANGUBAT, respondents.

D E C I S I O N

QUISUMBING, J.:

Before us is a petition for certiorari assailing the decisioni[1] dated July 19, 2000, of

the Court of Appeals in CA-G.R. SP No. 50383, which earlier reversed the decisionii[2]

dated January 30, 1998 of the National Labor Relations Commission (NLRC) in NLRC

Case No. V-0112-94.

The antecedent facts are as follows:

In its two plants located at Cebu City and Lapu-Lapu City, petitioner General Milling

Corporation (GMC) employed 190 workers. They were all members of private

respondent General Milling Corporation Independent Labor Union (union, for brevity),

a duly certified bargaining agent.

On April 28, 1989, GMC and the union concluded a collective bargaining agreement

(CBA) which included the issue of representation effective for a term of three years.

The CBA was effective for three years retroactive to December 1, 1988. Hence, it

would expire on November 30, 1991.

On November 29, 1991, a day before the expiration of the CBA, the union sent GMC a

proposed CBA, with a request that a counter-proposal be submitted within ten (10)

days.

As early as October 1991, however, GMC had received collective and individual letters

from workers who stated that they had withdrawn from their union membership, on

grounds of religious affiliation and personal differences. Believing that the union no

longer had standing to negotiate a CBA, GMC did not send any counter-proposal.

On December 16, 1991, GMC wrote a letter to the unions officers, Rito Mangubat and

Victor Lastimoso. The letter stated that it felt there was no basis to negotiate with a

union which no longer existed, but that management was nonetheless always willing to

dialogue with them on matters of common concern and was open to suggestions on

how the company may improve its operations.

In answer, the union officers wrote a letter dated December 19, 1991 disclaiming any

massive disaffiliation or resignation from the union and submitted a manifesto, signed

by its members, stating that they had not withdrawn from the union.

On January 13, 1992, GMC dismissed Marcia Tumbiga, a union member, on the ground

of incompetence. The union protested and requested GMC to submit the matter to the

grievance procedure provided in the CBA. GMC, however, advised the union to refer

to our letter dated December 16, 1991.iii[3]

Thus, the union filed, on July 2, 1992, a complaint against GMC with the NLRC,

Arbitration Division, Cebu City. The complaint alleged unfair labor practice on the part

of GMC for: (1) refusal to bargain collectively; (2) interference with the right to self-

organization; and (3) discrimination. The labor arbiter dismissed the case with the

recommendation that a petition for certification election be held to determine if the

union still enjoyed the support of the workers.

The union appealed to the NLRC.

On January 30, 1998, the NLRC set aside the labor arbiters decision. Citing Article

253-A of the Labor Code, as amended by Rep. Act No. 6715,iv[4] which fixed the

terms of a collective bargaining agreement, the NLRC ordered GMC to abide by the

CBA draft that the union proposed for a period of two (2) years beginning December 1,

1991, the date when the original CBA ended, to November 30, 1993. The NLRC also

ordered GMC to pay the attorneys fees.v[5]

In its decision, the NLRC pointed out that upon the effectivity of Rep. Act No. 6715,

the duration of a CBA, insofar as the representation aspect is concerned, is five (5)

years which, in the case of GMC-Independent Labor Union was from December 1, 1988

to November 30, 1993. All other provisions of the CBA are to be renegotiated not later

than three (3) years after its execution. Thus, the NLRC held that respondent union

remained as the exclusive bargaining agent with the right to renegotiate the economic

provisions of the CBA. Consequently, it was unfair labor practice for GMC not to enter

into negotiation with the union.

The NLRC likewise held that the individual letters of withdrawal from the union

submitted by 13 of its members from February to June 1993 confirmed the pressure

exerted by GMC on its employees to resign from the union. Thus, the NLRC also found

GMC guilty of unfair labor practice for interfering with the right of its employees to

self-organization.

With respect to the unions claim of discrimination, the NLRC found the claim

unsupported by substantial evidence.

On GMCs motion for reconsideration, the NLRC set aside its decision of January 30,

1998, through a resolution dated October 6, 1998. It found GMCs doubts as to the

status of the union justified and the allegation of coercion exerted by GMC on the

unions members to resign unfounded. Hence, the union filed a petition for certiorari

before the Court of Appeals. For failure of the union to attach the required copies of

pleadings and other documents and material portions of the record to support the

allegations in its petition, the CA dismissed the petition on February 9, 1999. The

same petition was subsequently filed by the union, this time with the necessary

documents. In its resolution dated April 26, 1999, the appellate court treated the

refiled petition as a motion for reconsideration and gave the petition due course.

On July 19, 2000, the appellate court rendered a decision the dispositive portion of

which reads:

WHEREFORE, the petition is hereby GRANTED. The NLRC Resolution of October 6,

1998 is hereby SET ASIDE, and its decision of January 30, 1998 is, except with

respect to the award of attorneys fees which is hereby deleted, REINSTATED.vi[6]

A motion for reconsideration was seasonably filed by GMC, but in a resolution dated

October 26, 2000, the CA denied it for lack of merit.

Hence, the instant petition for certiorari alleging that:

I

THE COURT OF APPEALS DECISION VIOLATED THE CONSTITUTIONAL RULE THAT

NO DECISION SHALL BE RENDERED BY ANY COURT WITHOUT EXPRESSING

THEREIN CLEARLY AND DISTINCTLY THE FACTS AND THE LAW ON WHICH IT IS

BASED.

II

THE COURT OF APPEALS COMMITTED GRAVE ABUSE OF DISCRETION IN

REVERSING THE DECISION OF THE NATIONAL LABOR RELATIONS COMMISSION

IN THE ABSENCE OF ANY FINDING OF SUBSTANTIAL ERROR OR GRAVE ABUSE

OF DISCRETION AMOUNTING TO LACK OR EXCESS OF JURISDICTION.

III

THE COURT OF APPEALS COMMITTED SERIOUS ERROR IN NOT APPRECIATING

THAT THE NLRC HAS NO JURISDICTION TO DETERMINE THE TERMS AND

CONDITIONS OF A COLLECTIVE BARGAINING AGREEMENT.vii[7]

Thus, in the instant case, the principal issue for our determination is whether or not

the Court of Appeals acted with grave abuse of discretion amounting to lack or excess

of jurisdiction in (1) finding GMC guilty of unfair labor practice for violating the duty to

bargain collectively and/or interfering with the right of its employees to self-

organization, and (2) imposing upon GMC the draft CBA proposed by the union for two

years to begin from the expiration of the original CBA.

On the first issue, Article 253-A of the Labor Code, as amended by Rep. Act No. 6715,

states:

ART. 253-A. Terms of a collective bargaining agreement. Any Collective

Bargaining Agreement that the parties may enter into shall, insofar as the

representation aspect is concerned, be for a term of five (5) years. No petition

questioning the majority status of the incumbent bargaining agent shall be entertained

and no certification election shall be conducted by the Department of Labor and

Employment outside of the sixty-day period immediately before the date of expiry of

such five year term of the Collective Bargaining Agreement. All other provisions of the

Collective Bargaining Agreement shall be renegotiated not later than three (3) years

after its execution....

The law mandates that the representation provision of a CBA should last for five years.

The relation between labor and management should be undisturbed until the last 60

days of the fifth year. Hence, it is indisputable that when the union requested for a

renegotiation of the economic terms of the CBA on November 29, 1991, it was still the

certified collective bargaining agent of the workers, because it was seeking said

renegotiation within five (5) years from the date of effectivity of the CBA on December

1, 1988. The unions proposal was also submitted within the prescribed 3-year period

from the date of effectivity of the CBA, albeit just before the last day of said period. It

was obvious that GMC had no valid reason to refuse to negotiate in good faith with the

union. For refusing to send a counter-proposal to the union and to bargain anew on

the economic terms of the CBA, the company committed an unfair labor practice under

Article 248 of the Labor Code, which provides that:

ART. 248. Unfair labor practices of employers. It shall be unlawful for an

employer to commit any of the following unfair labor practice:

. . .

(g) To violate the duty to bargain collectively as prescribed by this Code;

. . .

Article 252 of the Labor Code elucidates the meaning of the phrase duty to bargain

collectively, thus:

ART. 252. Meaning of duty to bargain collectively. The duty to bargain

collectively means the performance of a mutual obligation to meet and convene

promptly and expeditiously in good faith for the purpose of negotiating an

agreement....

We have held that the crucial question whether or not a party has met his statutory

duty to bargain in good faith typically turn$ on the facts of the individual case.viii[8]

There is no per se test of good faith in bargaining.ix[9] Good faith or bad faith is an

inference to be drawn from the facts.x[10] The effect of an employers or a unions

actions individually is not the test of good-faith bargaining, but the impact of all such

occasions or actions, considered as a whole.xi[11]

Under Article 252 abovecited, both parties are required to perform their mutual

obligation to meet and convene promptly and expeditiously in good faith for the

purpose of negotiating an agreement. The union lived up to this obligation when it

presented proposals for a new CBA to GMC within three (3) years from the effectivity

of the original CBA. But GMC failed in its duty under Article 252. What it did was to

devise a flimsy excuse, by questioning the existence of the union and the status of its

membership to prevent any negotiation.

It bears stressing that the procedure in collective bargaining prescribed by the Code is

mandatory because of the basic interest of the state in ensuring lasting industrial

peace. Thus:

ART. 250. Procedure in collective bargaining. The following procedures shall be

observed in collective bargaining:

(a) When a party desires to negotiate an agreement, it shall serve a written notice

upon the other party with a statement of its proposals. The other party shall make a

reply thereto not later than ten (10) calendar days from receipt of such notice.

(Underscoring supplied.)

GMCs failure to make a timely reply to the proposals presented by the union is

indicative of its utter lack of interest in bargaining with the union. Its excuse that it felt

the union no longer represented the workers, was mainly dilatory as it turned out to

be utterly baseless.

We hold that GMCs refusal to make a counter-proposal to the unions proposal for CBA

negotiation is an indication of its bad faith. Where the employer did not even bother to

submit an answer to the bargaining proposals of the union, there is a clear evasion of

the duty to bargain collectively.xii[12]

Failing to comply with the mandatory obligation to submit a reply to the unions

proposals, GMC violated its duty to bargain collectively, making it liable for unfair labor

practice. Perforce, the Court of Appeals did not commit grave abuse of discretion

amounting to lack or excess of jurisdiction in finding that GMC is, under the

circumstances, guilty of unfair labor practice.

Did GMC interfere with the employees right to self-organization? The CA found that

the letters between February to June 1993 by 13 union members signifying their

resignation from the union clearly indicated that GMC exerted pressure on its

employees. The records show that GMC presented these letters to prove that the

union no longer enjoyed the support of the workers. The fact that the resignations of

the union members occurred during the pendency of the case before the labor arbiter

shows GMCs desperate attempts to cast doubt on the legitimate status of the union.

We agree with the CAs conclusion that the ill-timed letters of resignation from the

union members indicate that GMC had interfered with the right of its employees to

self-organization. Thus, we hold that the appellate court did not commit grave abuse

of discretion in finding GMC guilty of unfair labor practice for interfering with the right

of its employees to self-organization.

Finally, did the CA gravely abuse its discretion when it imposed on GMC the draft CBA

proposed by the union for two years commencing from the expiration of the original

CBA?

The Code provides:

ART. 253. Duty to bargain collectively when there exists a collective

bargaining agreement. ....It shall be the duty of both parties to keep the status

quo and to continue in full force and effect the terms and conditions of the existing

agreement during the 60-day period [prior to its expiration date] and/or until a new

agreement is reached by the parties. (Underscoring supplied.)

The provision mandates the parties to keep the status quo while they are still in the

process of working out their respective proposal and counter proposal. The general

rule is that when a CBA already exists, its provision shall continue to govern the

relationship between the parties, until a new one is agreed upon. The rule necessarily

presupposes that all other things are equal. That is, that neither party is guilty of bad

faith. However, when one of the parties abuses this grace period by purposely delaying

the bargaining process, a departure from the general rule is warranted.

In Kiok Loy vs. NLRC,xiii[13] we found that petitioner therein, Sweden Ice Cream

Plant, refused to submit any counter proposal to the CBA proposed by its employees

certified bargaining agent. We ruled that the former had thereby lost its right to

bargain the terms and conditions of the CBA. Thus, we did not hesitate to impose on

the erring company the CBA proposed by its employees union - lock, stock and barrel.

Our findings in Kiok Loy are similar to the facts in the present case, to wit:

petitioner Companys approach and attitude stalling the negotiation by a series of

postponements, non-appearance at the hearing conducted, and undue delay in

submitting its financial statements, lead to no other conclusion except that it is

unwilling to negotiate and reach an agreement with the Union. Petitioner has not at

any instance, evinced good faith or willingness to discuss freely and fully the claims

and demands set forth by the Union much less justify its objection thereto.xiv[14]

Likewise, in Divine Word University of Tacloban vs. Secretary of Labor and

Employment,xv[15] petitioner therein, Divine Word University of Tacloban, refused to

perform its duty to bargain collectively. Thus, we upheld the unilateral imposition on

the university of the CBA proposed by the Divine Word University Employees Union.

We said further:

That being the said case, the petitioner may not validly assert that its consent should

be a primordial consideration in the bargaining process. By its acts, no less than its

action which bespeak its insincerity, it has forfeited whatever rights it could have

asserted as an employer.xvi[16]

Applying the principle in the foregoing cases to the instant case, it would be unfair to

the union and its members if the terms and conditions contained in the old CBA would

continue to be imposed on GMCs employees for the remaining two (2) years of the

CBAs duration. We are not inclined to gratify GMC with an extended term of the old

CBA after it resorted to delaying tactics to prevent negotiations. Since it was GMC

which violated the duty to bargain collectively, based on Kiok Loy and Divine Word

University of Tacloban, it had lost its statutory right to negotiate or renegotiate the

terms and conditions of the draft CBA proposed by the union.

We carefully note, however, that as strictly distinguished from the facts of this case,

there was no pre-existing CBA between the parties in Kiok Loy and Divine Word

University of Tacloban. Nonetheless, we deem it proper to apply in this case the

rationale of the doctrine in the said two cases. To rule otherwise would be to allow

GMC to have its cake and eat it too.

Under ordinary circumstances, it is not obligatory upon either side of a labor

controversy to precipitately accept or agree to the proposals of the other. But an

erring party should not be allowed to resort with impunity to schemes feigning

negotiations by going through empty gestures.xvii[17] Thus, by imposing on GMC the

provisions of the draft CBA proposed by the union, in our view, the interests of equity

and fair play were properly served and both parties regained equal footing, which was

lost when GMC thwarted the negotiations for new economic terms of the CBA.

The findings of fact by the CA, affirming those of the NLRC as to the reasonableness of

the draft CBA proposed by the union should not be disturbed since they are supported

by substantial evidence. On this score, we see no cogent reason to rule otherwise.

Hence, we hold that the Court of Appeals did not commit grave abuse of discretion

amounting to lack or excess of jurisdiction when it imposed on GMC, after it had

committed unfair labor practice, the draft CBA proposed by the union for the remaining

two (2) years of the duration of the original CBA. Fairness, equity, and social justice

are best served in this case by sustaining the appellate courts decision on this issue.

WHEREFORE, the petition is DISMISSED and the assailed decision dated July 19,

2000, and the resolution dated October 26, 2000, of the Court of Appeals in CA-G.R.

SP No. 50383, are AFFIRMED. Costs against petitioner.

SO ORDERED.

Republic of the Philippines

SUPREME COURT

Manila

SECOND DIVISION

G.R. No. L-54334 January 22, 1986

KIOK LOY, doing business under the name and style SWEDEN ICE CREAM

PLANT, petitioner,

vs.

NATIONAL LABOR RELATIONS COMMISSION (NLRC) and PAMBANSANG

KILUSAN NG PAGGAWA (KILUSAN), respondents.

Ablan and Associates for petitioner.

Abdulcadir T. Ibrahim for private respondent.

CUEVAS, J.:

Petition for certiorari to annul the decision 1 of the National Labor Relations

Commission (NLRC) dated July 20, 1979 which found petitioner Sweden Ice Cream

guilty of unfair labor practice for unjustified refusal to bargain, in violation of par. (g)

of Article 249 2 of the New Labor Code, 3 and declared the draft proposal of the Union

for a collective bargaining agreement as the governing collective bargaining agreement

between the employees and the management.

The pertinent background facts are as follows:

In a certification election held on October 3, 1978, the Pambansang Kilusang Paggawa

(Union for short), a legitimate late labor federation, won and was subsequently

certified in a resolution dated November 29, 1978 by the Bureau of Labor Relations as

the sole and exclusive bargaining agent of the rank-and-file employees of Sweden Ice

Cream Plant (Company for short). The Company's motion for reconsideration of the

said resolution was denied on January 25, 1978.

Thereafter, and more specifically on December 7, 1978, the Union furnished 4 the

Company with two copies of its proposed collective bargaining agreement. At the same

time, it requested the Company for its counter proposals. Eliciting no response to the

aforesaid request, the Union again wrote the Company reiterating its request for

collective bargaining negotiations and for the Company to furnish them with its

counter proposals. Both requests were ignored and remained unacted upon by the

Company.

Left with no other alternative in its attempt to bring the Company to the bargaining

table, the Union, on February 14, 1979, filed a "Notice of Strike", with the Bureau of

Labor Relations (BLR) on ground of unresolved economic issues in collective

bargaining. 5

Conciliation proceedings then followed during the thirty-day statutory cooling-off

period. But all attempts towards an amicable settlement failed, prompting the Bureau

of Labor Relations to certify the case to the National Labor Relations Commission

(NLRC) for compulsory arbitration pursuant to Presidential Decree No. 823, as

amended. The labor arbiter, Andres Fidelino, to whom the case was assigned, set the

initial hearing for April 29, 1979. For failure however, of the parties to submit their

respective position papers as required, the said hearing was cancelled and reset to

another date. Meanwhile, the Union submitted its position paper. The Company did

not, and instead requested for a resetting which was granted. The Company was

directed anew to submit its financial statements for the years 1976, 1977, and 1978.

The case was further reset to May 11, 1979 due to the withdrawal of the Company's

counsel of record, Atty. Rodolfo dela Cruz. On May 24, 1978, Atty. Fortunato

Panganiban formally entered his appearance as counsel for the Company only to

request for another postponement allegedly for the purpose of acquainting himself

with the case. Meanwhile, the Company submitted its position paper on May 28, 1979.

When the case was called for hearing on June 4, 1979 as scheduled, the Company's

representative, Mr. Ching, who was supposed to be examined, failed to appear. Atty.

Panganiban then requested for another postponement which the labor arbiter denied.

He also ruled that the Company has waived its right to present further evidence and,

therefore, considered the case submitted for resolution.

On July 18, 1979, labor arbiter Andres Fidelino submitted its report to the National

Labor Relations Commission. On July 20, 1979, the National Labor Relations

Commission rendered its decision, the dispositive portion of which reads as follows:

WHEREFORE, the respondent Sweden Ice Cream is hereby declared

guilty of unjustified refusal to bargain, in violation of Section (g)

Article 248 (now Article 249), of P.D. 442, as amended. Further, the

draft proposal for a collective bargaining agreement (Exh. "E ")

hereto attached and made an integral part of this decision, sent by

the Union (Private respondent) to the respondent (petitioner herein)

and which is hereby found to be reasonable under the premises, is

hereby declared to be the collective agreement which should govern

the relationship between the parties herein.

SO ORDERED. (Emphasis supplied)

Petitioner now comes before Us assailing the aforesaid decision contending that the

National Labor Relations Commission acted without or in excess of its jurisdiction or

with grave abuse of discretion amounting to lack of jurisdiction in rendering the

challenged decision. On August 4, 1980, this Court dismissed the petition for lack of

merit. Upon motion of the petitioner, however, the Resolution of dismissal was

reconsidered and the petition was given due course in a Resolution dated April 1,

1981.

Petitioner Company now maintains that its right to procedural due process has been

violated when it was precluded from presenting further evidence in support of its stand

and when its request for further postponement was denied. Petitioner further contends

that the National Labor Relations Commission's finding of unfair labor practice for

refusal to bargain is not supported by law and the evidence considering that it was

only on May 24, 1979 when the Union furnished them with a copy of the proposed

Collective Bargaining Agreement and it was only then that they came to know of the

Union's demands; and finally, that the Collective Bargaining Agreement approved and

adopted by the National Labor Relations Commission is unreasonable and lacks legal

basis.

The petition lacks merit. Consequently, its dismissal is in order.

Collective bargaining which is defined as negotiations towards a collective agreement,

6 is one of the democratic frameworks under the New Labor Code, designed to

stabilize the relation between labor and management and to create a climate of sound

and stable industrial peace. It is a mutual responsibility of the employer and the Union

and is characterized as a legal obligation. So much so that Article 249, par. (g) of the

Labor Code makes it an unfair labor practice for an employer to refuse "to meet and

convene promptly and expeditiously in good faith for the purpose of negotiating an

agreement with respect to wages, hours of work, and all other terms and conditions of

employment including proposals for adjusting any grievance or question arising under

such an agreement and executing a contract incorporating such agreement, if

requested by either party.

While it is a mutual obligation of the parties to bargain, the employer, however, is not

under any legal duty to initiate contract negotiation. 7 The mechanics of collective

bargaining is set in motion only when the following jurisdictional preconditions are

present, namely, (1) possession of the status of majority representation of the

employees' representative in accordance with any of the means of selection or

designation provided for by the Labor Code; (2) proof of majority representation; and

(3) a demand to bargain under Article 251, par. (a) of the New Labor Code . ... all of

which preconditions are undisputedly present in the instant case.

From the over-all conduct of petitioner company in relation to the task of negotiation,

there can be no doubt that the Union has a valid cause to complain against its

(Company's) attitude, the totality of which is indicative of the latter's disregard of, and

failure to live up to, what is enjoined by the Labor Code to bargain in good faith.

We are in total conformity with respondent NLRC's pronouncement that petitioner

Company is GUILTY of unfair labor practice. It has been indubitably established that

(1) respondent Union was a duly certified bargaining agent; (2) it made a definite

request to bargain, accompanied with a copy of the proposed Collective Bargaining

Agreement, to the Company not only once but twice which were left unanswered and

unacted upon; and (3) the Company made no counter proposal whatsoever all of

which conclusively indicate lack of a sincere desire to negotiate. 8 A Company's refusal

to make counter proposal if considered in relation to the entire bargaining process,

may indicate bad faith and this is specially true where the Union's request for a

counter proposal is left unanswered. 9 Even during the period of compulsory

arbitration before the NLRC, petitioner Company's approach and attitude-stalling the

negotiation by a series of postponements, non-appearance at the hearing conducted,

and undue delay in submitting its financial statements, lead to no other conclusion

except that it is unwilling to negotiate and reach an agreement with the Union.

Petitioner has not at any instance, evinced good faith or willingness to discuss freely

and fully the claims and demands set forth by the Union much less justify its

opposition thereto. 10

The case at bar is not a case of first impression, for in the Herald Delivery Carriers

Union (PAFLU) vs. Herald Publications 11 the rule had been laid down that "unfair

labor practice is committed when it is shown that the respondent employer, after

having been served with a written bargaining proposal by the petitioning Union, did

not even bother to submit an answer or reply to the said proposal This doctrine was

reiterated anew in Bradman vs. Court of Industrial Relations 12 wherein it was further

ruled that "while the law does not compel the parties to reach an agreement, it does

contemplate that both parties will approach the negotiation with an open mind and

make a reasonable effort to reach a common ground of agreement

As a last-ditch attempt to effect a reversal of the decision sought to be reviewed,

petitioner capitalizes on the issue of due process claiming, that it was denied the right

to be heard and present its side when the Labor Arbiter denied the Company's motion

for further postponement.

Petitioner's aforesaid submittal failed to impress Us. Considering the various

postponements granted in its behalf, the claimed denial of due process appeared

totally bereft of any legal and factual support. As herein earlier stated, petitioner had

not even honored respondent Union with any reply to the latter's successive letters, all

geared towards bringing the Company to the bargaining table. It did not even bother

to furnish or serve the Union with its counter proposal despite persistent requests

made therefor. Certainly, the moves and overall behavior of petitioner-company were

in total derogation of the policy enshrined in the New Labor Code which is aimed

towards expediting settlement of economic disputes. Hence, this Court is not prepared

to affix its imprimatur to such an illegal scheme and dubious maneuvers.

Neither are WE persuaded by petitioner-company's stand that the Collective

Bargaining Agreement which was approved and adopted by the NLRC is a total nullity

for it lacks the company's consent, much less its argument that once the Collective

Bargaining Agreement is implemented, the Company will face the prospect of closing

down because it has to pay a staggering amount of economic benefits to the Union

that will equal if not exceed its capital. Such a stand and the evidence in support

thereof should have been presented before the Labor Arbiter which is the proper forum

for the purpose.

We agree with the pronouncement that it is not obligatory upon either side of a labor

controversy to precipitately accept or agree to the proposals of the other. But an

erring party should not be tolerated and allowed with impunity to resort to schemes

feigning negotiations by going through empty gestures. 13 More so, as in the instant

case, where the intervention of the National Labor Relations Commission was properly

sought for after conciliation efforts undertaken by the BLR failed. The instant case

being a certified one, it must be resolved by the NLRC pursuant to the mandate of P.D.

873, as amended, which authorizes the said body to determine the reasonableness of

the terms and conditions of employment embodied in any Collective Bargaining

Agreement. To that extent, utmost deference to its findings of reasonableness of any

Collective Bargaining Agreement as the governing agreement by the employees and

management must be accorded due respect by this Court.

WHEREFORE, the instant petition is DISMISSED. The temporary restraining order

issued on August 27, 1980, is LIFTED and SET ASIDE.

No pronouncement as to costs.

SO ORDERED.

Republic of the Philippines

SUPREME COURT

Baguio City

THIRD DIVISION

G.R. No. 127422 April 17, 2001

LMG CHEMICALS CORPORATION, LMG CHEMICALS CORPORATION, petitioner,

vs.

THE SECRETARY OF THE DEPARTMENT OF LABOR AND EMPLOYMENT, THE

HON. LEONARDO A. QUISUMBING, and CHEMICAL WORKER'S UNION,

respondents.

SANDOVAL-GUTIERREZ, J.:

Before us is a petition certiorari with prayer for a temporary restraining order and a

writ of preliminary injunction under Rule 65 of the 1997 Rules of Civil Procedure, as

amended, seeking to nullify the orders dated October 7, 1996 and December 17,

1996, issued by the then Secretary of Labor and Employment, Hon. Leonardo A.

Quisumbing,1 in OS-AJ-05-10(1)-96, "IN RE: LABOR DISPUTE AT LMB CHEMICALS

CORPORATION"

The facts as culled from the records are:

LMG Chemicals Corporation, (petitioner) is a domestic corporation engaged in the

manufacture and sale of various kinds of chemical substances, including aluminum

sulfate which is essential in purifying water, and technical grade sulfuric acid used in

thermal power plants. Petitioner has three divisions, namely: the Organic Division,

Inorganic Division and the Pinamucan Bulk Carriers. There are two unions within

petitioner's Inorganic Division. One union represents the daily paid employees and the

other union represents the monthly paid employees. Chemical Workers Union,

respondent, is a duly registered labor organization acting as the collective bargaining

agent of all the daily paid employees of petitioner's Inorganic Division.

Sometime in December 1995, the petitioner and the respondent started negotiation for

a new Collective Bargaining Agreement (CBA) as their old CBA was about to expire.

They were able to agree on the political provisions of the new CBA, but no agreement

was reached on the issue of wage increase. The economic issues were not also settled.

The positions of the parties with respect to wage issue were:

"Petitioner Company

P40 per day on the first year

P40 per day on the second year

P40 per day on the third year

Respondent Union

P350 per day on the first 18 months, and

P150 per day for the next 18 months"

In the course of the negotiations, respondent union pruned down the originally

proposed wage increase quoted above to P215 per day, broken down as follows:

"P142 for the first 18 months

P73 for the second 18 months"

With the CBA negotiations at a deadlock, on March 6, 1996, respondent union filed a

Notice of Strike with the National Conciliation and Mediation Board, National Capital

Region. Despite several conferences and efforts of the designated conciliator-mediator,

the parties failed to reach an amicable settlement.

On April 16, 1996, respondent union staged a strike. IN an attempt to end the strike

early, petitioner, on April 24, 1996, made an improved offer of P135 per day, spread

over the period of three years, as follows:

"P55 per day on the first year;

P45 per day on the second year;

P35 per day on the third year."

On May 9, 1996, another conciliation meeting was held between the parties. In that

meeting, petitioner reiterated its improved offer of P135 per day which was again

rejected by the respondent union.

On May 20, 1996, the Secretary of Labor and Employment, finding the instant labor

dispute impressed with national interest, assumed jurisdiction over the same.

In compliance with the directive of the Labor Secretary, the parties submitted their

respective positive papers both dated June 21, 1996.

In its position paper, petitioner made a turn-around, stating that it could no longer

afford to grant its previous offer due to serious financial losses during the early months

of 1996. It then made the following offer:

Zero increase in the first year;

P30 per day increase in the second year; and

P20 per day increase in the third year.

In its reply to petitioner's position paper, respondent union claimed it had a positive

performance in terms of income during the covered period.

On October 7, 1996, the Secretary of Labor and Employment issued the first assailed

order, pertinent portions of which read:

"xxx. In the light of the Company's last offer and the Union's last

position, We decree that the Company's offer of P135 per day wage

increase be further increased to P140 per (day), which shall be

incorporated in the new CBA, as follows:

P90 per day for the first 18 months, and

P50 per day for the next 18 months.

After all, the Company had granted its supervisory employees an

increase of P4,500 per month or P166 per day, more or less, if the

period reckoned is 27 working days.

In regard to the division of the three-year period into two sub-periods

of 18 months each, this office take cognizance of the same practice

under the old CBA.

2. Other economic demands

Considering the financial condition of the Company, all other

economic demands except those provided in No. 3 below are rejected.

The provisions in the old CBA as well as those contained in the

Company's Employee's Primer of Benefits as of Aug. 1, 1994 shall be

retained and incorporated in the new CBA.

3. Effectivity of the new CBA

Article 253-A of the Labor Code, as amended, provides that when no

new CBA is signed during a period of six months from the expiry date

of the old CBA, the retroactivity period shall be according to the

parties' agreement, Inasmuch as the parties could not agree on this

issue and since this Office has assumed jurisdiction, then this matter

now lies at the discretion of the Secretary of labor and Employment.

Thus the new Collective Bargaining Agreement which the parties will

sign pursuant to this Order shall retroact to January 1, 1996.

x x x

Forthwith, petitioner filed a motion for reconsideration but was denied by the Secretary

in his order dated December 16, 1996.

Petitioner now contends that in issuing the said orders, respondent Secretary gravely

abused his discretion, thus:

I

"THE HONORABLE SECRETARY OF LABOR COMMITTED GRAVE ABUSE OF

DISCRETION AMOUNTING TO LACK OF JURISDICTION IN DISREGARDING

THE EVIDENCE OF PETITIONER'S FINANCIAL LOSSES AND IN GRANTING A

P140.00 WAGE INCREASE TO THE RESPONDENT UNION.

II

THE HONORABLE SECRETARY OF LABOR COMMITTED GRAVE ABUSE OF

DISCRETION AMOUNTING TO LACK OF JURISDICTION IN DECREEING THAT

THE NEW COLLECTIVE BARGAINING AGREEMENT TO BE SIGNED BY THE

PARTIES SHALL RETROACT TO JANUARY 1, 1996."

Anent the first ground, petitioner asserts that the decreed amount of P140 wage

increase has no basis in fact and in law. Petitioner insists that public respondent

Secretary whimsically presumed that the company can survive despite the losses being

suffered by its Inorganic Division and its additional losses caused by the strike held by

respondent union. Petitioner further contends that respondent Secretary disregarded

its evidence showing that for the first part of 1996, its Inorganic Division suffered

serious losses amounting to P15.651 million. Hence, by awarding wage increase

without any basis, respondent Secretary gravely abused his discretion and violated

petitioner's right to due process.

We are not persuaded.

As aptly stated by the Solicitor General in his comment on the petition dated July 1,

1996, respondent Secretary considered all the evidence and arguments adduced by

both parties. In ordering the wage increase, the Secretary ratiocinated as follows:

"xxx

In the Company's Supplemental Comment, it says that it has three

divisions, namely: the Organic Division, Inorganic Division and the

Pinamucan Bulk Carriers. The Union in this instant dispute represent

the daily wage earners in the Inorganic Division. The respective

income of the three divisions is shown in Annex B to the Company's

Supplemental Comment. The Organic Division posted an income of

P369,754,000 in 1995. The Inorganic Division realized an income of

P261,288,000 in the same period. The tail ender is the Pinamucan

Bulk Carriers Division with annual income of P11,803,000 for the

same period. Total Company income for the period was P642,845,000.

It is a sound business practice that a Company's income from all

sources are collated to determine its true financial condition.

Regardless of whether one division or another losses or gains in its

yearly operation is not material in reckoning a Company's financial

status. In fact, the loss in one is usually offset by the gains in the

others. It is not a good business practice to isolate the employees or

workers of one division, which incurred an operating loss for a

particular period. That will create demoralization among its ranks,

which will ultimately affect productivity. The eventual loser will be

the company.

So, even if We believe the position of the company that its Inorganic

Division lost last year and during the early months of this year, it

would not be a good argument to deny them of any salary increase.

When the Company made the offer of P135 per day for the three year

period, it was presumed to have studied its financial condition

properly, taking into consideration its past performance and

projected income. In fact, the Company realized a net income of

P10,806,678 for 1995 in all its operations, which could be one factor

why it offered the wage increase package of P135 per day for the

Union members.1wphi1.nt

Besides, as a major player in the country's corporate field, reneging

from a wage increase package it previously offered and later on

withdrawing the same simply because this Office had already

assumed jurisdiction over its labor dispute with the Union cannot be

countenanced. It will be worse if the employer is allowed to withdraw

its offer on the ground that the union staged a strike and

consequently subsequently suffered business setbacks in its income

projections. To sustain the Company's position is like hanging the

proverbial sword of Damocles over the Union's right to concerted

activities, ready to fall when the latter clamors for better terms and

conditions of employment.

But we cannot also sustain the Union's demand for an increase of

P215 per day. If we add the overload factors such as the increase in

SSS premiums, medicare and medicaid, and other multiplier costs, the

Company will be saddled with additional labor cost, and its projected

income for the CBS period may not be able to absorb the added cost

without impairing its viability. xxx"

Verily, petitioner's assertion that respondent Secretary failed to consider the evidence

on record lacks merit. It was only the Inorganic Division of the petitioner corporation

that was sustaining losses. Such incident does not justify the withholding of any salary

increase as petitioner's income from all sources are collated for the determination of its

true financial condition. As correctly stated by the Secretary, "the loss in one is usually

offset by the gains in the others."

Moreover, petitioner company granted its supervisory employees, during the pendency

of the negotiations between the parties, a wage increase of P4,500 per month or P166

per day, more or less. Petitioner justified this by saying that the said increase was

pursuant to its earlier agreement with the supervisions. Hence, the company had no

choice but to abide by such agreement even if it was already sustaining losses as a

result of the strike of the rank-and-file employees.

Petitioner's actuation is actually a discrimination against respondent union members. If

it could grant a wage increase to its supervisors, there is no valid reason why it should

deny the same to respondent union members. Significantly, while petitioner asserts

that it sustained losses in the first part of 1996, yet during the May 9, 1996

conciliation meeting, it made the offer of P135 daily wage to the said union members.

This Court, therefore, holds that respondent Secretary did not gravely abuse his

discretion in ordering the wage increase. Grave abuse of discretion implies whimsical

and capricious exercise of power which, in the instant case, is not obtaining.

On the second ground, petitioner contends that public respondent committed grave

abuse of discretion when he ordered that the new CBA which the parties will sign shall

retroact to January 1, 1996, citing the cases of Union of Filipro Employees vs. NLRC,2

and Pier 8 Arrastre and Stevedoring Services, Inc. vs. Roldan Confesor.3

Invoking the provisions of Article 253-A of the Labor Code, petitioner insists that public

respondent's discretion on the issue of the date of the effectivity of the new CBA is

limited to either: (1) leaving the matter of the date of effectivity of the new CBA is

limited to either: (1) leaving the matter of the date of effectivity of the new CBA to the

agreement of the parties or (2) ordering that the terms of the new CBA be

prospectively applied.

It must be emphasized that respondent Secretary assumed jurisdiction over the

dispute because it is impressed with national interest. As noted by the Secretary, "the

petitioner corporation was then supplying the sulfate requirements of MWSS as well as

the sulfuric acid of NAPOCOR, and consequently, the continuation of the strike would

seriously affect the water supply of Metro Manila and the power supply of the Luzon

Grid." Such authority of the Secretary to assume jurisdiction carries with it the power

to determine the retroactivity of the parties' CBA.

It is well settled in our jurisprudence that the authority of the Secretary of Labor to

assume jurisdiction over a labor dispute causing or likely to cause a strike or lockout in

an industry indispensable to national interest includes and extends to all questions and

controversies arising therefrom. The power is plenary and discretionary in nature to

enable him to effectively and efficiently dispose of the primary dispute.4

In St. Luke's Medical Center, Inc. vs. Torres5, a deadlock developed during the CBA

negotiations between the management and the union. The Secretary of Labor assumed

jurisdiction and ordered that their CBA shall retroact to the date of the expiration of

the previous CBA. The management claimed that the Secretary of Labor gravely

abused his discretion. This Court held:

"xxx

Finally, the effectivity of the Order of January 28, 1991, must retroact

to the date of the expiration of the previous CBA, contrary to the

position of the petitioner. Under the circumstances of the case, Art.

253-A cannot be properly applied to herein case. As correctly stated

by public respondent in his assailed Order of April 12, 1991

'Anent the alleged lack of basis for retroactivity provisions

awarded, We would stress that the provision of law invoked

by the Hospital, Article 253-A of the Labor Code, speaks of

agreement by and between the parties, and not arbitral

awards.'

Therefore in the absence of the specific provision of law prohibiting

retroactivity of the effectivity of the arbitral awards issued by the

Secretary of Labor pursuant to Article 263(g) of the Labor Code, such

as herein involved, public respondent is deemed vested with plenary

powers to determine the effectivity thereof."

Finally, to deprive respondent Secretary of such power and discretion would run

counter to the well-established rule that all doubts in the interpretation of labor laws

should be resolved in favor of labor. In upholding the assailed orders of respondent

Secretary, this Court is only giving meaning to this rule. Indeed, the Court should help

labor authorities in providing workers immediate benefits, without being hampered by

arbitration or litigation processes that prove to be not only nerve-wracking but

financially burdensome in the long run.

As we said in Maternity Children's Hospital vs. Secretary of Labor6:

"Social Justice Legislation, to be truly meaningful and rewarding to

our workers, must not be hampered in its application by long winded-

arbitration and litigation. Rights must be asserted and benefits

received with the least inconvenience. Labor laws are meant to

promote, not to defeat, social justice."

WHEREFORE, the instant petition is DENIED. The assailed orders of the Secretary of

Labor dated October 7, 1996 and December 16, 1996 are AFFIRMED. Costs against

petitioner.

SO ORDERED.

Republic of the Philippines

SUPREME COURT

Manila

THIRD DIVISION

G.R. No. 121227 August 17, 1998

VICENTE SAN JOSE, petitioner,

vs.

NATIONAL LABOR RELATIONS COMMISSION and OCEAN TERMINAL

SERVICES, INC., respondent.

PURISIMA, J.:

Before the Court is a Petition for Certiorari seeking to annul a Decision of the National

Labor Relations Commission dated April 20, 1995 in NLRC-NCR-CA-No. 00671-94