Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

In The Supreme Court of The State of Kansas: Appellee

Enviado por

api-2475268000 notas0% acharam este documento útil (0 voto)

45 visualizações21 páginasA district court may properly consider the weight of proffered evidence. The weight that an expert's opinion is to be given lies in the hands of the jury. Language "another trial would be a burden on both sides" in jury instructions is error.

Descrição original:

Título original

Untitled

Direitos autorais

© © All Rights Reserved

Formatos disponíveis

PDF, TXT ou leia online no Scribd

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoA district court may properly consider the weight of proffered evidence. The weight that an expert's opinion is to be given lies in the hands of the jury. Language "another trial would be a burden on both sides" in jury instructions is error.

Direitos autorais:

© All Rights Reserved

Formatos disponíveis

Baixe no formato PDF, TXT ou leia online no Scribd

0 notas0% acharam este documento útil (0 voto)

45 visualizações21 páginasIn The Supreme Court of The State of Kansas: Appellee

Enviado por

api-247526800A district court may properly consider the weight of proffered evidence. The weight that an expert's opinion is to be given lies in the hands of the jury. Language "another trial would be a burden on both sides" in jury instructions is error.

Direitos autorais:

© All Rights Reserved

Formatos disponíveis

Baixe no formato PDF, TXT ou leia online no Scribd

Você está na página 1de 21

1

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE STATE OF KANSAS

No. 101,054

STATE OF KANSAS,

Appellee,

v.

JOHN HENRY HORTON,

Appellant.

SYLLABUS BY THE COURT

1.

A district court may properly consider the weight of proffered evidence as a factor

in deciding whether to reopen the presentation of evidence after the party has rested its

case.

2.

Application of harmless error analysis does not impermissibly intrude on the

province of the jury.

3.

Under K.S.A. 60-456, the opinion testimony of experts on an ultimate issue is

admissible only so far as the opinion will aid the jury in interpreting technical facts or

understanding the material in evidence. An expert's opinion is admissible up to the point

where expressing the opinion requires the expert to pass upon the credibility of witnesses

or the weight of disputed evidence.

2

4.

The weight that an expert's opinion is to be given lies in the hands of the jury.

5.

Under K.S.A. 60-456(b), although the district judge controls expert opinion

evidence that has the potential to unduly prejudice or mislead a jury or confuse the

question at issue, it is generally preferred to allow the jury to resolve disputed evidence

by such tools as cross-examination, the submission of contrary evidence, and the use of

appropriate jury instructions.

6.

When a foundation in the expertise of a dog handler has been established,

including factors such as training, experience, and certification, as well as the reliability

of the dog, evidence stemming from a canine search may be admitted into evidence.

7.

An element of allowing such foundation evidence is whether the opposing party

has the opportunity to carry out adequate cross-examination of the witness.

8.

Inclusion of the language "another trial would be a burden on both sides" in the

instructions to a jury is error.

9.

It is not sufficient simply to lodge an objection in order to preserve an issue; the

articulated basis of the objection must be specific to the error asserted on appeal.

3

10.

On the facts of this case, inclusion of the language "[a]nother trial would be a

burden on both sides" in the jury instruction given, while erroneous, was not reversible

error. There was no real possibility the jury would have rendered a different verdict if the

error had not occurred.

Appeal from Johnson District Court; JAMES FRANKLIN DAVIS, judge. Opinion filed August 8,

2014. Affirmed.

Lydia Krebs, of Kansas Appellate Defender Office, argued the cause and was on the briefs for

appellant.

Stephen M. Howe, district attorney, argued the cause, and Steven J. Obermeier, assistant district

attorney, Steve Six, former attorney general, and Derek Schmidt, attorney general, were with him on the

briefs for appellee.

The opinion of the court was delivered by

ROSEN, J.: Following the reversal by this court of his conviction in his first trial,

John Henry Horton appealed from his conviction of first-degree felony murder at his

second trial. While retaining jurisdiction over the case, this court remanded the case to

the district court for evidentiary findings and conclusions relating to the narrow issue of

reopening the defense case based on evidence that came to light after the jury began its

deliberations. The district court ruled adversely to Horton on remand, and he reasserts

that issue before this court. All issues raised by the parties in the appeal from his second

trial are now ripe for decision.

In July 1974, 13-year-old L.W. disappeared on her way home from a public

swimming pool in Prairie Village. Skeletal remains were found in a nearby undeveloped

4

field several months later. In 2003, DNA confirmed that the remains were L.W.'s. The

State charged Horton with first-degree felony murder. More detailed facts underlying his

conviction are set out in the decision in the original appeal, State v. Horton, 283 Kan. 44,

151 P.3d 9 (2007), and the decision remanding for further proceedings, State v. Horton,

292 Kan. 437, 254 P.3d 1264 (2011). Facts necessary for determining specific issues will

be explained in our discussion of those issues below.

Reopening the Case After the Jury Began Its Deliberations

After hearing arguments on the second appeal, this court remanded the case for a

hearing limited to the issue of reopening the case based on the correct legal standards.

Following the hearing and judgment of the district court, the parties reargued the issue

before this court. The record is now sufficiently complete to allow appellate review.

Two inmates who were incarcerated at the same facility as Horton, Danny

Barnhouse and Sergio Castillo-Contreras, testified at the second trial. Barnhouse testified

that Horton had told him that he was in prison because he had accidentally killed a little

girl. Barnhouse said that Horton told him he abducted the girl and used chloroform on a

rag to render her unconscious. He then had intercourse with her until she woke up and

began fighting with him, scratching his face. He became angry and applied the

chloroform again until she stopped moving. Horton then said that he dumped her body in

a field.

Castillo-Contreras similarly testified that Horton had told him that Horton had

used a rag containing a chemical to make a girl unconscious and that he killed her when

she woke up during his sexual assault and fought with him. Castillo-Contreras also

testified that Horton said he should have chopped up the body to prevent it from being

found.

5

A third inmate, Michael Buddenhagen, testified that Barnhouse asked him for

assistance in looking up the opinion from Horton's first appeal on a computer legal

opinion data base. Buddenhagen testified that both Barnhouse and Castillo-Contreras

looked at the opinion in his presence. His testimony was introduced for the purpose of

suggesting that the other two inmates might have crafted their testimony based on what

they read instead of reporting what Horton really told them.

Following the testimony of other witnesses on a variety of topics, the parties rested

and made closing arguments to the jury. Then, on the morning of March 5, 2008, while

the jury was still deliberating, counsel for Horton made a motion to suspend jury

deliberations in order to allow counsel to procure an accurate translation of a recorded

telephone conversation of July 2007 between Castillo-Contreras and Castillo-Contreras'

mother. The defense requested a 2-day continuance in order to determine whether it

would be appropriate to ask to reopen the evidentiary presentation.

The defense had subpoenaed the telephone records in February 2008 before the

trial began. The phone records were received about a week later and were turned over

immediately to a translator. Unfortunately, problems arose in obtaining a translation

because the conversation involved a Chilean dialect of Spanish and because specific

software was required in order to listen to the conversation. Furthermore, the software

had idiosyncrasies that made it difficult for the translator to hear the speech.

As explained in Horton, 292 Kan. 437, the district court, operating under the belief

that it had no authority to reopen the presentation of evidence after the parties rested,

denied the motion to suspend jury deliberations. This court pointed out that Kansas has

long recognized the discretion of a district court to reopen cases under appropriate

circumstances and held that the district court abused its discretion by refusing to exercise

6

its lawful discretion. See 292 Kan. at 438-40. We suspended the appeal and remanded the

case to the district court for determination of the narrow issue of whether it should have

reopened the presentation of evidence to allow the jury to hear evidence relating to the

recording of Castillo-Contreras' telephone conversations and any rebuttal evidence

offered by the State. 292 Kan. at 441.

The task of the district court was to determine what it would have done at the time

of trial with the proffer of testimony if it had applied the proper legal principles in

making its decision. In making this determination on remand, the district court conducted

several hearings and reviewed translated transcripts of the telephone conversations that

triggered the motion as well as additional recorded conversations between Castillo-

Contreras and his family, even though the defense did not refer to these additional

conversations at the time it moved to reopen the case.

On remand, the district court had available the complete transcripts of the

telephone conversations. Of course, at the time of the motion at the original trial, the

district court did not have these transcripts available, and the contents of the

conversations were speculative at that time. A review of the transcribed conversations

reveals some statements by Castillo-Contreras that might lead a fact-finder to question his

veracity, but there is no point at which he expressly says or even strongly hints that his

testimony was perjured in exchange for a reduced term of incarceration. The transcripts

contain no direct confession of perjury.

The primary conversation is subjectively unclear and ambiguous; it refers to

unidentified people and it appears to assume that the participants already knew what is

going on. It apparently deals with two, possibly related topics: a deal that Castillo-

Contreras wanted to work out with the district attorney and with payments that were sent

to Castillo-Contreras' family, perhaps as a form of protection money extorted from

7

Horton's family in exchange for Horton's safety in prison. It appears from the

conversations that the prosecution did not originally want to use Castillo-Contreras as a

witness, but other witnesses were proving to be unreliable. Castillo-Contreras insisted

that he be released to Chilean jurisdiction in exchange for his testimony.

Two additional telephone conversations between Castillo-Contreras and his family

were transcribed, translated, and presented to the district court at the remand hearing.

They related to his hope for deportation in exchange for his testimony and his efforts to

communicate with an attorney.

In addition to reading the transcribed telephone conversations, the district court

heard the sworn testimony of several witnesses. Yolanda Bustamante, a court-certified

interpreter, informed the court that she received CDs of the telephone conversations

before the trial began and finished listening to them while the trial was in progress. She

was instructed by defense counsel to let him know if she heard anything "interesting,"

and it was her recommendation that the recordings be transcribed and translated.

Brad Cordts, a Kansas Bureau of Investigation agent assigned to work on the

Horton case in 2007, was called to the witness stand by the defense. Cordts had testified

at the trial that prosecutor Steve Maxwell told him about Castillo-Contreras and that

Maxwell was contacted by Robert Stevenson, chief investigator at Norton Correctional

Facility. Cordts then interviewed Castillo-Contreras at the Johnson County Jail. Cordts

also testified at the remand hearing but did not disclose any information calling into

question Castillo-Contreras' candor.

Stevenson, who was assigned to the case by the Kansas Department of Corrections

and whose name was mentioned in the transcribed conversations, testified about his

knowledge of Castillo-Contreras reliability as a jailhouse informant. Castillo-Contreras

8

was a jailhouse informant at Norton Correctional Facility and was used to help monitor

the Hispanic population. Stevenson testified that he had no memory of Castillo-Contreras

being used to target a particular person.

In Horton, 292 Kan. at 438-41, we directed the district court to apply the factors

set out in State v. Murdock, 286 Kan. 661, 672-73, 187 P.3d 1267 (2008). In Murdock,

this court, quoting from United States v. Blankenship, 775 F.2d 735, 741 (6th Cir. 1985),

explained the factors a trial court should consider in exercising its discretionary authority

to allow a party to reopen its case:

"'In exercising its discretion, the court must consider the timeliness of the motion, the

character of the testimony, and the effect of the granting of the motion. The party moving

to reopen should provide a reasonable explanation for fail[ing] to present the evidence in

its case-in-chief. The evidence proffered should be relevant, admissible, technically

adequate, and helpful to the jury in ascertaining the guilt or innocence of the accused.

The belated receipt of such testimony should not "imbue the evidence with distorted

importance, prejudice the opposing party's case, or preclude an adversary from having an

adequate opportunity to meet the additional evidence offered." [Citation omitted.]'"

Murdock, 286 Kan. at 672-73.

The district court took into account both the transcribed conversations and the

testimony of the witnesses. In reaching its decision on remand that it would be

inappropriate to reopen the case to allow Horton to bring in the telephone conversations,

the district court considered several factors.

First, the district court determined that the late introduction of the evidence would

overemphasize that particular testimony to the jury and would be prejudicial to the State

because the State would have to overcome the likely undue importance attached to the

evidence. Second, the character of the evidence did not strongly indicate dishonesty on

9

the part of Castillo-Contreras and did not offer information that was not available at trial.

While the transcription showed that he wanted a deal and was not testifying only

"because it was the right thing to do," the transcription did not show that a deal was

actually made. The transcription may have hinted that the prosecution coached Castillo-

Contreras on the facts of the case and what it wanted to hear him say. It was brought out

at trial that he had read the published opinion from the first appeal and understood the

facts from that trial. Third, the district court considered the practical effect of granting the

defense motion. As it turned out, the transcription and translation of the recording

required nearly 60 days and 250 hours to complete. Postponing jury deliberations for

such an extended time would have severely impaired the jury's ability to consider the

evidence fairly. Finally, the delay on the part of the defense in attempting to introduce the

telephone conversations was understandable and forgivable because technical problems

hindered the defense in ascertaining whether the conversations might be useful in

presenting its case. As soon as the defense was alerted that the conversations had content

that related to the case, it acted to inform the court.

The district court concluded that the transcribed telephone conversation met "the

low threshold of admissibility because it does affect Mr. Castillo-Contreras' credibility to

a certain extent." The court went on to decide, however, that the potential prejudice to the

State and the likely disruption to the trial proceedings outweighed the probative value of

the evidence and that reopening the case would have brought about an unjust result.

Horton argues that the prejudicial delay aspect of the Murdock criteria is negated

by an analysis of the reasons for the delay. The essence of his argument is that defendants

should not suffer prejudice because circumstances beyond their control compelled them

to wait until late in the trial process to present relevant evidence.

10

While Horton's argument has force, it should be kept in mind that the Murdock

factors represent a balancing of interests. Waiting until after the jury has begun

deliberating may prejudice the opposing party; and not allowing a defendant to present

substantial, relevant evidence may also create prejudice against a defendant. Furthermore,

strong justification for a party's failure to present the case during the regular statement of

the parties' cases may help excuse the failure to present the evidence in a timely manner.

An important additional factor, however, is the weight of the evidence. A district

court may, in its discretion, admit tangentially relevant evidence during a case-in-chief

that it would not allow after jury deliberations have begun, because the potential

prejudice against the State would be greater than the potential prejudice against the

defendant, even if the late admission were not the fault of the defendant. The defendant's

degree of fault may therefore become a nonissue under the Murdock factors, and the

district court was not required to address that as a factor in explaining why it reached its

decision.

Horton also challenges the district court's evaluation of the character of the

proffered evidence. The district court made passing reference to the inadmissibility of

hearsay statements by Castillo-Contreras' family members, which Horton challenges as

an inaccurate statement of the law. Because the statements were not being offered as

proof of the matters asserted, Horton argues the district court erred as a matter of law.

While Horton's argument is correct in the abstract, it does not present this court

with reversible error. The statements of the family members were of minor substance and

tended to repeat or confirm what Castillo-Contreras was presenting as either a monologue

or a series of directions. A review of the telephone conversations does not produce any

evidence beyond that which Castillo-Contreras himself stated and which the district court

considered in its ruling.

11

Horton then attacks the district court's analysis of the effect that admitting the

evidence would have had on the trial. The essence of his argument is that it should have

been left to the jury to evaluate whether the recordings undermined Castillo-Contreras'

testimony. Although it is true that to a limited extent the district court placed itself in the

jury's stead, we note that courts often step into the role of determining whether admitting

certain evidence would have made a difference to a jury. In a sense, the harmless error

doctrine invades the province of the jury, but appellate courts frequently engage in

weighing the possible effects of evidence on a jury. See, e.g., Fry v. Pliler, 551 U.S. 112,

116, 127 S. Ct. 2321, 168 L. Ed. 2d 16 (2007) (lower harmless error standard in federal

habeas corpus collateral review of state court decision); Washington v. Recuenco, 548

U.S. 212, 218, 126 S. Ct. 2546, 165 L. Ed. 2d 466 (2006) (Supreme Court has repeatedly

recognized that most constitutional errors can be harmless); State v. Sampson, 297 Kan.

288, 299-300, 301 P.3d 276 (2013) (abuse of discretion subject to harmless error standard

of review). Therefore, application of the harmless error standard does not impermissibly

intrude on the province of the jury.

As the district court noted, this court has held that newly discovered evidence

merely tending to impeach or discredit the testimony of a witness is not grounds for

granting a new trial. See, e.g., Baker v. State, 243 Kan. 1, 11, 755 P.2d 493 (1988). The

evidence that Horton sought to introduce after the jury began deliberating was not newly

discovered; at that point in time, the defense did not know whether it had anything to

present to the jury.

The telephone conversation evidence which Horton urges this court to send to a

jury as part of a retrial is very weak in terms of its probative value. In some ways, it

bolsters the State's caseCastillo-Contreras told his mother that he overheard Horton

acknowledging his crime. In other ways, the evidence merely adds additional emphasis to

12

what was already before the jury, such as information that Castillo-Contreras had read the

facts of the case before he spoke with prosecutors. And some of the evidence casts doubt

on his motives for testifying, such as his vehement insistence that he receive some sort of

deal in exchange for testifying, even though no deal was assured.

These statements are isolated examples extracted from a lengthy conversation in

which Castillo-Contreras explicitly and without any prompting told his mother that

Horton confessed to him that he had committed murder. While cross-examination based

on those statements might have opened up further doubt about his credibility, the defense

had already challenged that credibility at trial, especially by pointing out that Castillo-

Contreras had read the published opinion of this court before testifying. Horton asks this

court to find that the district court abused its discretion because it held that it would not

have interrupted jury deliberations to allow the defendant to introduce this marginally

relevant impeachment evidence. Such an appellate determination would substantially

lower the threshold for abuse of discretion.

We conclude that the district court performed the duty that we instructed it to carry

out on remand. It was thorough in creating and reviewing a record of the issue and

analyzing the law. We find no abuse of discretion in its conclusions.

Animated Reconstruction Video

Over Horton's objection, the State introduced into evidence an animated

reconstruction video of the relative locations and movements of L.W., Horton, and

witnesses. Horton argues on appeal that allowing the jury to view the video constituted

prejudicial error.

13

In the first appeal, Horton raised the issue of whether the State could introduce a

reconstruction report, including a diagram with a posited path of travel for the victim. We

declined to address the issue, citing the lack of a contemporaneous objection. Horton, 283

Kan. at 63. During the second trial, the State expanded on that reconstruction through an

animated video that it presented to the jury.

Before the second trial began, Horton moved to exclude the video. The district

court conducted an evidentiary hearing in limine and considered the testimony of John

Glennon, a forensic automotive technologist, who testified that the assumptions

underlying the reconstruction were speculative and flawed. The court nevertheless

elected to allow the State to present the video in support of its case.

Over Horton's repeated objections, the jury later watched the video reconstruction

and heard the testimony of Captain Dan Meyer, who provided data used in creating the

video, and Roy Buchanan, who created the video and explained to the jury what the video

purported to represent. According to the video reconstruction, based on their previously

observed speeds and directions of travel, Horton and L.W. would have found themselves

in the same place at a particular time, giving Horton the opportunity to abduct her.

Horton urges this court to reverse his conviction because the video assumed facts

not in evidence and permitted the jury to consider expert testimony that was speculative

in nature.

Under K.S.A. 60-456, the opinion testimony of experts on an ultimate issue is

admissible only so far as the opinion will aid the jury in interpreting technical facts or

understanding the material in evidence. An expert's opinion is admissible up to the point

where expressing the opinion requires the expert to pass upon the credibility of witnesses

14

or the weight of disputed evidence. State v. Bressman, 236 Kan. 296, Syl. 3, 5, 689

P.2d 901 (1984).

The weight that an expert's opinion is to be given lies in the hands of the jury.

State v. Johnson, 286 Kan. 824, 837, 190 P.3d 207 (2008); City of Mission Hills v.

Sexton, 284 Kan. 414, Syl. 8, 160 P.3d 812 (2007). Under K.S.A. 60-456(b), although

the district judge controls expert opinion evidence that has the potential to unduly

prejudice or mislead a jury or confuse the question at issue, it is generally preferred to

allow the jury to resolve disputed evidence. Cross-examination, the submission of

contrary evidence, and the use of appropriate jury instructions are the favored methods of

resolving factual disputes. Kuhn v. Sandoz Pharmaceuticals Corp., 270 Kan. 443, 461, 14

P.3d 1170 (2000).

We find no error in the decision by the district court to allow the State to play the

video for the jury. The video and accompanying testimony helped illustrate the State's

complex theory, and the video served as nothing more than an aid to the jury in

understanding that theory. Rather than proving that Horton and L.W. were in the same

place at the same time, the video may be understood as establishing the plausibility of the

State's theory that Horton and L.W. crossed paths. The jury had the opportunity to

evaluate the reliability of the video and its assumptions. Many of the assumptions

underlying the reconstruction were based on the statements of witnesses whose

credibility was already before the jury, such as the fact that L.W.'s younger brother was

running along a certain path and that Horton was standing by certain trees.

The Exclusion of Exculpatory Dog-Search Evidence

Administrative records showed that almost 3 weeks after L.W. disappeared, on

July 27, 1974, Tom McGinn, a dog handler from Pennsylvania, brought two dogs to

15

perform a search of the high school where L.W. was last seen. The dogs had been

exposed to and later alerted to L.W.'s clothes. The dogs alerted to the victim's scent on

steps leading from the lower parking lots to the upper parking lots south of the high

school. They did not alert to her presence in Horton's car or on his clothes.

At trial, however, Horton's counsel was unable to locate McGinn and was unable

to identify the authors of the Federal Bureau of Investigation report favorably referring to

the search. The district court elected to exclude the evidence because there was no basis

for establishing the reliability of the reports. On appeal, Horton challenges this exclusion.

When a foundation in the expertise of a dog handler has been established,

including factors such as training, experience, and certification, as well as the reliability

of the dog, evidence stemming from a canine search may be admitted into evidence. See,

e.g., State v. Brown, 266 Kan. 563, 573-74, 973 P.2d 773 (1999); State v. Netherton, 133

Kan. 685, 690-91, 3 P.2d 495 (1931); State v. Fixley, 118 Kan. 1, Syl. 1, 2, 233 P. 796

(1925); State v. Adams, 85 Kan. 435, Syl. 3, 116 P. 608 (1911). An element of allowing

such foundation evidence is whether the opposing party has the opportunity to carry out

adequate cross-examination of the witness. See Brown, 266 Kan. at 574; see also State v.

Barker, 252 Kan. 949, Syl. 6, 850 P.2d 885 (1993) (probable cause for vehicle search

based on canine sniff requires foundation testimony; minimum requirement includes

description of the dog's conduct, training, and experience by knowledgeable person who

can interpret the conduct as signaling the presence of a controlled substance).

In the present case, Horton was unable to produce the authors of the 35-year-old

FBI report relating to the dog search tending to exonerate him. He maintains, in essence,

that the probative value of the report outweighs its questionable reliability. He suggests

that because the report included police and FBI records, the report must be reliable.

16

In the first appeal, State v. Horton, 283 Kan. 44, 60-62, 151 P.3d 9 (2007), this

court held that the trial court did not err in allowing the State to present evidence tending

to show that hairs found in the high school, inside the passenger compartment of Horton's

car, and inside one of the canvas bags in Horton's trunk belonged to the victim, even

though the original hairs had been destroyed in the intervening years and could not be

positively tested for DNA compatibility. Horton argues that admitting testimony relating

to the hairs while excluding the canine-search report unfairly favored the State.

We held in the first appeal:

"The failure to positively identify a piece of evidence does not preclude the

admission of the evidence. The lack of positive identification affects the weight of the

evidence as opposed to its admissibility. [Citations omitted.] In this case, the State's

inability to positively and indisputably identify the source of every hair that was

compared does not preclude the admission of the evidence. Rather, the possibility for

contamination affects the weight to be given the evidence. The jury bears the

responsibility for weighing the evidence, resolving conflicts in the testimony, and

drawing reasonable inferences to determine the ultimate facts. [Citation omitted.]" 283

Kan. at 61.

The differences between the evidence of the hairs and the evidence of the dog

search lie in both the foundation that could be established for each and the cross-

examination to which each could be subjected. Even though the hairs taken from Horton's

car had been destroyed, the State provided a witness who had examined the hairs and

who testified about the procedures he used to compare the evidence from the car with

hairs taken from the victim's brush. The defense cross-examined the witness about his

conclusions and the reliability of the evidence.

17

Although the dog-scent evidence was relevant and material, in that it had a direct

bearing on a central question of whether Horton had physical contact with the victim, that

was not enough to make it admissible. Because the parties could not subject McGinn to

direct or cross-examination, the jury could have only speculated on how reliable the

search was. It is unknown what experience McGinn had with the particular dogs that

were used; it is unknown how the dogs were trained; it is unknown how they would alert

in different situations; it is unknown how consistent their alerting was; it is unknown

whether McGinn had problems with the dogs' reliability in other settings; and it is

unknown on what basis the FBI reporters evaluated McGinn's reliability.

For these reasons we conclude that the trial court did not err as a matter of law and

did not abuse its discretion in excluding the dog-search report.

The Jury Instruction

Horton objects on appeal to a jury instruction directing the jury to try to resolve

any differences of opinion and reach a consensus.

Jury Instruction 23 read in its entirety:

"Like all cases, this is an important case. If you fail to reach a decision on some

or all of the charges, that charge or charges are left undecided for the time being. It is

then up to the state to decide whether to resubmit the undecided charge(s) to a different

jury at a later time. Another trial would be a burden on both sides.

"This does not mean that those favoring any particular position should surrender

their honest convictions as to the weight or effect of any evidence solely because of the

opinion of other jurors or because of the importance of arriving at a decision.

18

"This does mean that you should give respectful consideration to each other's

views and talk over any differences of opinion in a spirit of fairness and candor. If at all

possible, you should resolve any differences and come to a common conclusion.

"You may be as leisurely in your deliberations as the occasion may require and

take all the time you feel necessary."

Horton's counsel offered a general objection, stating that the proposed jury

instruction was "unnecessary." He went on to say, "I believe it will be coercive on the

jury. I believe it would give them the impression that they don't have the freedom to

disagree and state their points." After taking the matter under advisement, the court

elected to give the proposed jury instruction.

When analyzing a properly preserved jury instruction issue on appeal, this court

follows a progressive step analysis:

"For jury instruction issues, the progression of analysis and corresponding

standards of review on appeal are: (1) First, the appellate court should consider the

reviewability of the issue from both jurisdiction and preservation viewpoints, exercising

an unlimited standard of review; (2) next, the court should use an unlimited review to

determine whether the instruction was legally appropriate; (3) then, the court should

determine whether there was sufficient evidence, viewed in the light most favorable to

the defendant or the requesting party, that would have supported the instruction; and (4)

finally, if the district court erred, the appellate court must determine whether the error

was harmless, utilizing the test and degree of certainty set forth in State v. Ward, 292

Kan. 541, 256 P.3d 801 (2011), cert. denied 132 S. Ct. 1594 (2012)." State v. Plummer,

295 Kan. 156, Syl. 1, 283 P.3d 202 (2012.)

In determining whether a specific jury instruction was erroneous, this court

considers the instructions as a whole without isolating any one instruction and reviews

the instruction to see whether it properly and fairly stated the law as applied to the facts

19

of the case and could not have reasonably misled the jury. State v. Appleby, 289 Kan.

1017, 1059, 221 P.3d 525 (2009).

The jury instruction at issue generally resembles that approved in Allen v. United

States, 164 U.S. 492, 17 S. Ct. 154, 41 L. Ed. 528 (1896). Until recently, a line of Kansas

cases upheld the language that is the subject of this appeal. See, e.g., State v. Nguyen, 285

Kan. 418, 436-37, 172 P.3d 1165 (2007); State v. Scott-Herring, 284 Kan. 172, 180-81,

159 P.3d 1028 (2007); State v. Makthepharak, 276 Kan. 563, 569, 78 P.3d 412 (2003);

State v. Noriega, 261 Kan. 440, 454, 932 P.2d 940 (1997); State v. Roadenbaugh, 234

Kan. 474, 483, 673 P.2d 1166 (1983); State v. Irving, 231 Kan. 258, 265-66, 644 P.2d

389 (1982).

Horton's second trial took place in March 2008. This court subsequently

determined that the language that "another trial would be a burden on both sides" is error

because it is misleading and inaccurate: "Contrary to this language, a second trial may be

burdensome to some but not all on either side of a criminal case. Moreover, the language

is confusing. It sends conflicting signals when read alongside [an] instruction that tells

jurors not to concern themselves with what happens after they arrive at a verdict." State v.

Salts, 288 Kan. 263, 266, 200 P.3d 464 (2009). We concluded, however, that the standard

of review was clear error, and we were firmly convinced that there was no real possibility

that the jury would have rendered a different verdict had the error not occurred. 288 Kan.

at 267.

While it is true that Horton objected to the instruction, his objection was based on

the allegedly coercive and superfluous nature of the instruction, not on the confusing

elements that formed the grounds for error that we found in Salts. It is not sufficient

simply to lodge an objection in order to preserve an issue; the articulated basis of the

objection must be specific to the error asserted on appeal. See K.S.A. 60-404 (objection

20

must be "so stated as to make clear the specific ground of objection"); State v. McCaslin,

291 Kan. 697, 707-08, 245 P.3d 1030 (2011) (while there may be some overlap of

objections, that overlap does not satisfy the specificity requirement of the objection);

State v. Bryant, 272 Kan. 1204, 1208, 38 P.3d 661 (2002) (hearsay objection at trial not

sufficient to raise issue of Confrontation Clause violation on appeal).

In the absence of a sufficiently specific objection, this court will review the

instruction for clear error. See K.S.A. 22-3414(3) (party may not assign error to

instruction unless party objects "stating distinctly the matter to which the party objects

and the grounds of the objection unless the instruction . . . is clearly erroneous"); State v.

Williams, 295 Kan. 506, Syl. 3, 286 P.3d 195 (2012).

If a jury instruction that was not adequately preserved for appeal is erroneous, then

this court inquires into reversibility and assesses whether it is firmly convinced that the

jury would not have reached a different verdict had the instruction error not occurred.

The party asserting a clearly erroneous jury instruction has the burden of establishing the

degree of prejudice necessary for reversal. Williams, 295 Kan. 506, Syl. 5.

In his brief, Horton points to various statements made by jurors in voir dire and by

witnesses at trial that referred to the previous trial and conviction. Horton argues that

there was a real possibility that the jury was influenced by language reminding it of the

burden of a subsequent trial.

Nothing in the record suggests, however, that the jury was confused by the

instruction or that the jury was close to a deadlock. The jury did not submit questions

relating to its burden or inform the judge that it was having difficulty reaching a decision.

Furthermore, witnesses from the time of the murder linked Horton to the victim, and

witnesses who spoke with him while he was incarcerated testified that Horton

21

acknowledged committing the crime. For these reasons, we are not firmly convinced that

the jury would have returned a different verdict if the instruction had not been given. The

instruction was therefore not clearly erroneous. See State v. King, 297 Kan. 955, 985-86,

305 P.3d 641 (2013) (in the absence of evidence of deadlock and in the presence of

compelling evidence of guilt, no clearly reversible error in giving Allen-type instruction).

While the jury instruction was not legally appropriate, the objection was not

sufficiently specific to avoid a clear error harmlessness test. The record simply does not

support reversal on this issue.

Finding no reversible error, we affirm the conviction.

MORITZ, J., not participating.

MICHAEL J. MALONE, District Judge, assigned.

1

1

REPORTER'S NOTE: District Judge Malone was appointed to hear case No. 101,054

vice Justice Moritz pursuant to the authority vested in the Supreme Court by art. 3, 6(f)

of the Kansas Constitution.

Você também pode gostar

- 01 Beat ANY - ALL Speeding Tickets in Washington StateDocumento6 páginas01 Beat ANY - ALL Speeding Tickets in Washington StateLuis Ewing90% (10)

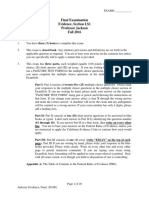

- Final Examination Evidence, Section LS1 Professor Jackson Fall 2016Documento28 páginasFinal Examination Evidence, Section LS1 Professor Jackson Fall 2016steph.hernan6704100% (1)

- Steven Downs Motion For Acquittal or New TrialDocumento10 páginasSteven Downs Motion For Acquittal or New TrialAlaska's News SourceAinda não há avaliações

- Hale v. Henkel, 201 U.S. 43 (1906)Documento27 páginasHale v. Henkel, 201 U.S. 43 (1906)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- Dungo vs. People, G.R. No. 209464, July 1, 2015 (761 SCRA 375, 427-431)Documento1 páginaDungo vs. People, G.R. No. 209464, July 1, 2015 (761 SCRA 375, 427-431)Multi PurposeAinda não há avaliações

- Cir V Spouses Manly Digest (Tax)Documento1 páginaCir V Spouses Manly Digest (Tax)Erika Bianca ParasAinda não há avaliações

- People v. ParejaDocumento2 páginasPeople v. Parejadylabolante921Ainda não há avaliações

- 999 - People vs. Macam - L-91011-12Documento2 páginas999 - People vs. Macam - L-91011-12Brian Kelvin PinedaAinda não há avaliações

- Procunier v. Atchley, 400 U.S. 446 (1971)Documento7 páginasProcunier v. Atchley, 400 U.S. 446 (1971)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- United States v. Charles A. Harrington, 490 F.2d 487, 2d Cir. (1973)Documento19 páginasUnited States v. Charles A. Harrington, 490 F.2d 487, 2d Cir. (1973)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- Stuart W. Newsom v. W. Frank Smyth, JR., Superintendent of The Virginia State Penitentiary, 261 F.2d 452, 4th Cir. (1958)Documento4 páginasStuart W. Newsom v. W. Frank Smyth, JR., Superintendent of The Virginia State Penitentiary, 261 F.2d 452, 4th Cir. (1958)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- United States v. Tracy Coy Poe, Leroy Dale Hines, Carla Florentine Hines, Anna Mae Hines, Paul E. Neal, William R. Gibbs and Edward E. Harma, 713 F.2d 579, 10th Cir. (1983)Documento7 páginasUnited States v. Tracy Coy Poe, Leroy Dale Hines, Carla Florentine Hines, Anna Mae Hines, Paul E. Neal, William R. Gibbs and Edward E. Harma, 713 F.2d 579, 10th Cir. (1983)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- Buck Wilcoxon v. United States, 231 F.2d 384, 10th Cir. (1956)Documento6 páginasBuck Wilcoxon v. United States, 231 F.2d 384, 10th Cir. (1956)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- Jorge M. Herrera v. New Mexico Department of Corrections Attorney General of The State of New Mexico, 82 F.3d 426, 10th Cir. (1996)Documento3 páginasJorge M. Herrera v. New Mexico Department of Corrections Attorney General of The State of New Mexico, 82 F.3d 426, 10th Cir. (1996)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- Thomas P. Bowling v. George A. Vose, Director of The Department of Corrections, State of Rhode Island, 3 F.3d 559, 1st Cir. (1993)Documento6 páginasThomas P. Bowling v. George A. Vose, Director of The Department of Corrections, State of Rhode Island, 3 F.3d 559, 1st Cir. (1993)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- Furr v. Brady, 440 F.3d 34, 1st Cir. (2006)Documento12 páginasFurr v. Brady, 440 F.3d 34, 1st Cir. (2006)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- United States Court of Appeals Third CircuitDocumento19 páginasUnited States Court of Appeals Third CircuitScribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- United States Ex Rel. Alton Cannon v. Harold J. Smith, Superintendent, Attica Correctional Facility, Attica, New York, 527 F.2d 702, 2d Cir. (1975)Documento10 páginasUnited States Ex Rel. Alton Cannon v. Harold J. Smith, Superintendent, Attica Correctional Facility, Attica, New York, 527 F.2d 702, 2d Cir. (1975)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- Ray TAYLOR, Petitioner, v. IllinoisDocumento32 páginasRay TAYLOR, Petitioner, v. IllinoisScribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- Samuel G. Townes v. C. C. Peyton, Superintendent of The Virginia State Penitentiary, 404 F.2d 456, 4th Cir. (1968)Documento8 páginasSamuel G. Townes v. C. C. Peyton, Superintendent of The Virginia State Penitentiary, 404 F.2d 456, 4th Cir. (1968)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- United States v. Kelvin Brown, 4th Cir. (2016)Documento9 páginasUnited States v. Kelvin Brown, 4th Cir. (2016)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- Filed: Patrick FisherDocumento24 páginasFiled: Patrick FisherScribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- Michael John Bell v. Wayne K. Patterson, 402 F.2d 394, 10th Cir. (1968)Documento8 páginasMichael John Bell v. Wayne K. Patterson, 402 F.2d 394, 10th Cir. (1968)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- United States v. Mark Christopher Poe, 81 F.3d 152, 4th Cir. (1996)Documento5 páginasUnited States v. Mark Christopher Poe, 81 F.3d 152, 4th Cir. (1996)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- United States v. Edith Evelyn Young, A/K/A Sister, 974 F.2d 1346, 10th Cir. (1992)Documento9 páginasUnited States v. Edith Evelyn Young, A/K/A Sister, 974 F.2d 1346, 10th Cir. (1992)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- Filed: Patrick FisherDocumento24 páginasFiled: Patrick FisherScribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- Ernest John Dobbert, Jr. v. Louie L. Wainwright, Secretary, Department of Corrections of the State of Florida, R.L. Dugger, Superintendent of Florida State Prisons, Respondents, 742 F.2d 1274, 11th Cir. (1984)Documento5 páginasErnest John Dobbert, Jr. v. Louie L. Wainwright, Secretary, Department of Corrections of the State of Florida, R.L. Dugger, Superintendent of Florida State Prisons, Respondents, 742 F.2d 1274, 11th Cir. (1984)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- Carlos (Charlie) Sanchez v. Harold A. Cox, 357 F.2d 260, 10th Cir. (1966)Documento5 páginasCarlos (Charlie) Sanchez v. Harold A. Cox, 357 F.2d 260, 10th Cir. (1966)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- Henry Martinez Porter v. Dan v. McKaskle Acting Director, Texas Department of Corrections, 466 U.S. 984 (1984)Documento5 páginasHenry Martinez Porter v. Dan v. McKaskle Acting Director, Texas Department of Corrections, 466 U.S. 984 (1984)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- Soulia v. O'brien, Warden, 188 F.2d 233, 1st Cir. (1951)Documento3 páginasSoulia v. O'brien, Warden, 188 F.2d 233, 1st Cir. (1951)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- United States v. Angel Manuel Lopez, 611 F.2d 44, 4th Cir. (1979)Documento5 páginasUnited States v. Angel Manuel Lopez, 611 F.2d 44, 4th Cir. (1979)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- United States v. Richard Mark Clinger and Charles Edward Harmon, 681 F.2d 221, 4th Cir. (1982)Documento5 páginasUnited States v. Richard Mark Clinger and Charles Edward Harmon, 681 F.2d 221, 4th Cir. (1982)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- United States v. Gene Stipe and Red Ivy, 653 F.2d 446, 10th Cir. (1981)Documento5 páginasUnited States v. Gene Stipe and Red Ivy, 653 F.2d 446, 10th Cir. (1981)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- United States Court of Appeals, Fourth CircuitDocumento14 páginasUnited States Court of Appeals, Fourth CircuitScribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- United States v. Clarence Smith, A/K/A "Texas Shorty,", 521 F.2d 374, 10th Cir. (1975)Documento5 páginasUnited States v. Clarence Smith, A/K/A "Texas Shorty,", 521 F.2d 374, 10th Cir. (1975)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- Robert L. Jones v. Lanson Newsome, 846 F.2d 62, 11th Cir. (1988)Documento5 páginasRobert L. Jones v. Lanson Newsome, 846 F.2d 62, 11th Cir. (1988)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- United States v. Ronald W.jordan, 466 F.2d 99, 4th Cir. (1972)Documento14 páginasUnited States v. Ronald W.jordan, 466 F.2d 99, 4th Cir. (1972)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- United States v. Marcelo Jose Suarez, 380 F.2d 713, 2d Cir. (1967)Documento6 páginasUnited States v. Marcelo Jose Suarez, 380 F.2d 713, 2d Cir. (1967)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- Cedrick S. Barriner v. Secretary, Department of Corrections, 11th Cir. (2015)Documento14 páginasCedrick S. Barriner v. Secretary, Department of Corrections, 11th Cir. (2015)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- William Langton v. Louis Berman, 667 F.2d 231, 1st Cir. (1981)Documento6 páginasWilliam Langton v. Louis Berman, 667 F.2d 231, 1st Cir. (1981)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- David Dao Criminal ComplaintDocumento7 páginasDavid Dao Criminal ComplaintChrisAinda não há avaliações

- United States Ex Rel. James Brennan, Relator-Appellant v. Hon. Edward M. Fay, As Warden of Green Haven Prison, Stormville, New York, 353 F.2d 56, 2d Cir. (1965)Documento6 páginasUnited States Ex Rel. James Brennan, Relator-Appellant v. Hon. Edward M. Fay, As Warden of Green Haven Prison, Stormville, New York, 353 F.2d 56, 2d Cir. (1965)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- Rule 110 Case DigestsDocumento15 páginasRule 110 Case DigestsDamie Emata LegaspiAinda não há avaliações

- United States Ex Rel. Cooper, Relators-Appellants v. Wilfred L. Denno, Warden of Sing Sing Prison, 221 F.2d 626, 2d Cir. (1955)Documento8 páginasUnited States Ex Rel. Cooper, Relators-Appellants v. Wilfred L. Denno, Warden of Sing Sing Prison, 221 F.2d 626, 2d Cir. (1955)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- Everett C. McKethan v. United States, 439 U.S. 936 (1978)Documento4 páginasEverett C. McKethan v. United States, 439 U.S. 936 (1978)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- Jose Martinez High, Cross-Appellant v. Ralph Kemp, Warden, Georgia Diagnostic and Classification Center, Respondent - Cross-Appellee, 819 F.2d 988, 11th Cir. (1987)Documento12 páginasJose Martinez High, Cross-Appellant v. Ralph Kemp, Warden, Georgia Diagnostic and Classification Center, Respondent - Cross-Appellee, 819 F.2d 988, 11th Cir. (1987)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- United States Ex Rel. Charles Glinton, Relator-Appellant v. Wilfred L. Denno, Warden of Sing Sing Prison, and The People of The State of New York, 291 F.2d 541, 2d Cir. (1961)Documento2 páginasUnited States Ex Rel. Charles Glinton, Relator-Appellant v. Wilfred L. Denno, Warden of Sing Sing Prison, and The People of The State of New York, 291 F.2d 541, 2d Cir. (1961)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- Murray v. Giarratano, 492 U.S. 1 (1989)Documento28 páginasMurray v. Giarratano, 492 U.S. 1 (1989)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- John D. Wade v. Howard Yeager, Warden, New Jersey State Prison, and State of New Jersey, 415 F.2d 570, 3rd Cir. (1969)Documento6 páginasJohn D. Wade v. Howard Yeager, Warden, New Jersey State Prison, and State of New Jersey, 415 F.2d 570, 3rd Cir. (1969)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- State v. Strong, Ariz. Ct. App. (2014)Documento11 páginasState v. Strong, Ariz. Ct. App. (2014)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- United States Ex Rel. Smith v. Baldi, 344 U.S. 561 (1953)Documento9 páginasUnited States Ex Rel. Smith v. Baldi, 344 U.S. 561 (1953)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- United States v. Victor Ernesto Bosch, United States of America v. Victor Correa Gomez, 584 F.2d 1113, 1st Cir. (1978)Documento14 páginasUnited States v. Victor Ernesto Bosch, United States of America v. Victor Correa Gomez, 584 F.2d 1113, 1st Cir. (1978)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- Jeffrey Allen Muehleman v. Florida, 484 U.S. 882 (1987)Documento5 páginasJeffrey Allen Muehleman v. Florida, 484 U.S. 882 (1987)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- Jesse Woodruff Jones v. Leonard R. Dugger, and Robert A. Butterworth, 888 F.2d 1340, 11th Cir. (1989)Documento5 páginasJesse Woodruff Jones v. Leonard R. Dugger, and Robert A. Butterworth, 888 F.2d 1340, 11th Cir. (1989)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- Raleigh Porter v. Harry K. Singletary, Secretary Florida Department of Corrections, 14 F.3d 554, 11th Cir. (1994)Documento12 páginasRaleigh Porter v. Harry K. Singletary, Secretary Florida Department of Corrections, 14 F.3d 554, 11th Cir. (1994)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- United States v. Kenneth M. Johnson, A/K/A President, 846 F.2d 75, 4th Cir. (1988)Documento5 páginasUnited States v. Kenneth M. Johnson, A/K/A President, 846 F.2d 75, 4th Cir. (1988)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- Vizconde MotionDocumento10 páginasVizconde MotionRechel De TorresAinda não há avaliações

- Paul Searing and Joann Searing v. Edward B. Hayes, 684 F.2d 694, 10th Cir. (1982)Documento5 páginasPaul Searing and Joann Searing v. Edward B. Hayes, 684 F.2d 694, 10th Cir. (1982)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- United States v. Mutulu Shakur, A/K/A "Doc", A/K/A "Jerel Wayne Williams", and Marilyn Jean Buck, A/K/A "Carol Durant", A/K/A "Nina Lewis", A/K/A "Diana Campbell", A/K/A "Norma Miller", 888 F.2d 234, 2d Cir. (1989)Documento6 páginasUnited States v. Mutulu Shakur, A/K/A "Doc", A/K/A "Jerel Wayne Williams", and Marilyn Jean Buck, A/K/A "Carol Durant", A/K/A "Nina Lewis", A/K/A "Diana Campbell", A/K/A "Norma Miller", 888 F.2d 234, 2d Cir. (1989)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- Ralph E. Rogers v. Norman Carver, Etc., 833 F.2d 379, 1st Cir. (1987)Documento11 páginasRalph E. Rogers v. Norman Carver, Etc., 833 F.2d 379, 1st Cir. (1987)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- Peter F. Lafrance v. George H. Bohlinger, Iii, Etc., 499 F.2d 29, 1st Cir. (1974)Documento10 páginasPeter F. Lafrance v. George H. Bohlinger, Iii, Etc., 499 F.2d 29, 1st Cir. (1974)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- John Turner, Warden, Utah State Prison v. Fay Ward, JR., 321 F.2d 918, 10th Cir. (1963)Documento5 páginasJohn Turner, Warden, Utah State Prison v. Fay Ward, JR., 321 F.2d 918, 10th Cir. (1963)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- United States Ex Rel. Alton Cannon v. Ernest L. Montanye, Superintendent, Attica Correctional Facility, 486 F.2d 263, 2d Cir. (1973)Documento11 páginasUnited States Ex Rel. Alton Cannon v. Ernest L. Montanye, Superintendent, Attica Correctional Facility, 486 F.2d 263, 2d Cir. (1973)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- Frank Jimmy Snider, Jr. v. W. K. Cunningham, JR., Superintendent of The Virginia State Penitentiary, 292 F.2d 683, 4th Cir. (1961)Documento5 páginasFrank Jimmy Snider, Jr. v. W. K. Cunningham, JR., Superintendent of The Virginia State Penitentiary, 292 F.2d 683, 4th Cir. (1961)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- Goldstein v. United States, 316 U.S. 114 (1942)Documento12 páginasGoldstein v. United States, 316 U.S. 114 (1942)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- UntitledDocumento1 páginaUntitledapi-247526800Ainda não há avaliações

- UntitledDocumento3 páginasUntitledapi-247526800Ainda não há avaliações

- State of Kansas Tenth Judicial District Steve Howe, District AttorneyDocumento1 páginaState of Kansas Tenth Judicial District Steve Howe, District Attorneyapi-247526800Ainda não há avaliações

- UntitledDocumento1 páginaUntitledapi-247526800Ainda não há avaliações

- UntitledDocumento1 páginaUntitledapi-247526800Ainda não há avaliações

- State of Kansas Tenth Judicial District Steve Howe, District AttorneyDocumento1 páginaState of Kansas Tenth Judicial District Steve Howe, District Attorneyapi-247526800Ainda não há avaliações

- UntitledDocumento2 páginasUntitledapi-247526800Ainda não há avaliações

- State of Kansas Tenth Judicial District Steve Howe, District AttorneyDocumento1 páginaState of Kansas Tenth Judicial District Steve Howe, District Attorneyapi-247526800Ainda não há avaliações

- State of Kansas Tenth Judicial District Steve Howe, District AttorneyDocumento1 páginaState of Kansas Tenth Judicial District Steve Howe, District Attorneyapi-247526800Ainda não há avaliações

- Office of District Attorney: Press Release - For Immediate ReleaseDocumento1 páginaOffice of District Attorney: Press Release - For Immediate Releaseapi-247526800Ainda não há avaliações

- UntitledDocumento1 páginaUntitledapi-247526800Ainda não há avaliações

- State of Kansas Tenth Judicial District Steve Howe, District AttorneyDocumento1 páginaState of Kansas Tenth Judicial District Steve Howe, District Attorneyapi-247526800Ainda não há avaliações

- State of Kansas Tenth Judicial District Steve Howe, District AttorneyDocumento1 páginaState of Kansas Tenth Judicial District Steve Howe, District Attorneyapi-247526800Ainda não há avaliações

- State of Kansas Tenth Judicial District Steve Howe, District AttorneyDocumento1 páginaState of Kansas Tenth Judicial District Steve Howe, District Attorneyapi-247526800Ainda não há avaliações

- Complaint: Clerk of The District Court, Johnson County Kansas 08/03/15 10:50am JLDocumento3 páginasComplaint: Clerk of The District Court, Johnson County Kansas 08/03/15 10:50am JLapi-247526800Ainda não há avaliações

- State of Kansas Tenth Judicial District Steve Howe, District AttorneyDocumento1 páginaState of Kansas Tenth Judicial District Steve Howe, District Attorneyapi-247526800Ainda não há avaliações

- State of Kansas Tenth Judicial District Steve Howe, District Attorney Updated: (Olathe, KS)Documento1 páginaState of Kansas Tenth Judicial District Steve Howe, District Attorney Updated: (Olathe, KS)api-247526800Ainda não há avaliações

- UntitledDocumento3 páginasUntitledapi-247526800Ainda não há avaliações

- Office of District Attorney: Press Release - For Immediate ReleaseDocumento1 páginaOffice of District Attorney: Press Release - For Immediate Releaseapi-247526800Ainda não há avaliações

- State of Kansas Tenth Judicial District Steve Howe, District AttorneyDocumento1 páginaState of Kansas Tenth Judicial District Steve Howe, District Attorneyapi-247526800Ainda não há avaliações

- UntitledDocumento3 páginasUntitledapi-247526800Ainda não há avaliações

- State of Kansas Tenth Judicial District Steve Howe, District AttorneyDocumento1 páginaState of Kansas Tenth Judicial District Steve Howe, District Attorneyapi-247526800Ainda não há avaliações

- UntitledDocumento2 páginasUntitledapi-247526800Ainda não há avaliações

- Free Training: Featuring Chayo ReyesDocumento1 páginaFree Training: Featuring Chayo Reyesapi-247526800Ainda não há avaliações

- Press Release - For Immediate ReleaseDocumento1 páginaPress Release - For Immediate Releaseapi-247526800Ainda não há avaliações

- State of Kansas Tenth Judicial District Office of District Attorney Steve Howe, District AttorneyDocumento1 páginaState of Kansas Tenth Judicial District Office of District Attorney Steve Howe, District Attorneyapi-247526800Ainda não há avaliações

- State of Kansas: Press Release - For Immediate ReleaseDocumento1 páginaState of Kansas: Press Release - For Immediate Releaseapi-247526800Ainda não há avaliações

- Free Training: Featuring Chayo ReyesDocumento1 páginaFree Training: Featuring Chayo Reyesapi-247526800Ainda não há avaliações

- State of Kansas Tenth Judicial District Office of District Attorney Steve Howe, District AttorneyDocumento1 páginaState of Kansas Tenth Judicial District Office of District Attorney Steve Howe, District Attorneyapi-247526800Ainda não há avaliações

- UntitledDocumento1 páginaUntitledapi-247526800Ainda não há avaliações

- Pico vs. Combong - AM No. RTJ 91-764Documento3 páginasPico vs. Combong - AM No. RTJ 91-764blessaraynesAinda não há avaliações

- Keeton AppealDocumento3 páginasKeeton AppealJason SmathersAinda não há avaliações

- United States District Court Southern District of New YorkDocumento24 páginasUnited States District Court Southern District of New YorkMatt TroutmanAinda não há avaliações

- Young v. Huntsville Hospital (1992, Supreme Court of Alabama)Documento8 páginasYoung v. Huntsville Hospital (1992, Supreme Court of Alabama)Alyssa HennigAinda não há avaliações

- US v. Punsalan PDFDocumento1 páginaUS v. Punsalan PDFdats_idjiAinda não há avaliações

- 6 Wild ReleaseDocumento6 páginas6 Wild ReleaseChristopher RobbinsAinda não há avaliações

- 17 Brief Seeking Judgment and Sanction Re TerminixDocumento14 páginas17 Brief Seeking Judgment and Sanction Re TerminixThomas F CampbellAinda não há avaliações

- People v. Dacudao, 170 SCRA 489Documento4 páginasPeople v. Dacudao, 170 SCRA 489JAinda não há avaliações

- Agreed MTN For Dismissal W Prejudice - FinalDocumento6 páginasAgreed MTN For Dismissal W Prejudice - FinalGameDaily.bizAinda não há avaliações

- Benton Murder Case ReplyDocumento36 páginasBenton Murder Case ReplyKGW NewsAinda não há avaliações

- Bascos Vs CADocumento3 páginasBascos Vs CAlovekimsohyun89Ainda não há avaliações

- United States v. Morgan, 4th Cir. (2003)Documento3 páginasUnited States v. Morgan, 4th Cir. (2003)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- CA Civ Pro OutlineDocumento58 páginasCA Civ Pro OutlineDakota SmithAinda não há avaliações

- 10 Temporary Restraining OrderDocumento5 páginas10 Temporary Restraining OrderGuy Hamilton-SmithAinda não há avaliações

- LABOR RELATIONS Sutherland Global Services vs. LabradorDocumento7 páginasLABOR RELATIONS Sutherland Global Services vs. LabradormarieAinda não há avaliações

- Go V CADocumento2 páginasGo V CAJohn BasAinda não há avaliações

- Vakalatnama IN THE COURT OFDocumento2 páginasVakalatnama IN THE COURT OFSachin DhamijaAinda não há avaliações

- James Edwards Motion ResponseDocumento49 páginasJames Edwards Motion ResponseJames EdwardsAinda não há avaliações

- G.R. No. 180677 February 18, 2013: Code), To WitDocumento4 páginasG.R. No. 180677 February 18, 2013: Code), To WitAngelette BulacanAinda não há avaliações

- Picart vs. SmithDocumento2 páginasPicart vs. SmithKrisel MonteraAinda não há avaliações

- Picart Vs Smith 37 Phil 809Documento3 páginasPicart Vs Smith 37 Phil 809Manz Edam C. JoverAinda não há avaliações

- United States v. Patrick Ganim, 4th Cir. (2016)Documento4 páginasUnited States v. Patrick Ganim, 4th Cir. (2016)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- Affidavit of Lehoan T. Pham in Response To Deirdre Evavold's Letter Dated September 27, 2019Documento6 páginasAffidavit of Lehoan T. Pham in Response To Deirdre Evavold's Letter Dated September 27, 2019mikekvolpeAinda não há avaliações

- UP Board of Regents Vs LigotDocumento2 páginasUP Board of Regents Vs LigotArmy PadillaAinda não há avaliações