Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

64 701 1 PB

Enviado por

awuahboh0 notas0% acharam este documento útil (0 voto)

15 visualizações6 páginasDiabetic foot ulcers (DFU) are among the most costly complications of diabetes. A nutritional supplement containing arginine, glutamine and beta-hydroxy-beta-methylbutyrate dramatically improved the healing of these lesions.

Descrição original:

Título original

64-701-1-PB

Direitos autorais

© © All Rights Reserved

Formatos disponíveis

PDF, TXT ou leia online no Scribd

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDiabetic foot ulcers (DFU) are among the most costly complications of diabetes. A nutritional supplement containing arginine, glutamine and beta-hydroxy-beta-methylbutyrate dramatically improved the healing of these lesions.

Direitos autorais:

© All Rights Reserved

Formatos disponíveis

Baixe no formato PDF, TXT ou leia online no Scribd

0 notas0% acharam este documento útil (0 voto)

15 visualizações6 páginas64 701 1 PB

Enviado por

awuahbohDiabetic foot ulcers (DFU) are among the most costly complications of diabetes. A nutritional supplement containing arginine, glutamine and beta-hydroxy-beta-methylbutyrate dramatically improved the healing of these lesions.

Direitos autorais:

© All Rights Reserved

Formatos disponíveis

Baixe no formato PDF, TXT ou leia online no Scribd

Você está na página 1de 6

Original Article

J Endocrinol Metab 2012;2(1):26-31

Press Elmer

Articles The authors | Journal compilation J Endocrinol Metab and Elmer Press | www.jofem.org

The Use of a Specialized Nutritional Supplement for Diabetic

Foot Ulcers Reduces the Use of Antibiotics

Patrizio Tatti

a, c

, Annabel Elisabeth Barber

b

Abstract

Background: Diabetic foot ulcers (DFU) are among the most in-

validating and costly complications of diabetes. We evaluated the

effect of a blend of arginine, glutamine and -hydroxy-methyl-

butyrate on the healing of these lesions in a group of 22 diabetic

subjects who served as their own control. A nutritional supplement

containing arginine, glutamine and beta-hydroxy-beta-methylbu-

tyrate (Ar-Gl-HMB) dramatically improved the healing of diabetic

foot ulcers in two studies. Glutamine and Arginine have an antibac-

terial and immunopotentiating action and should reduce the use of

antibiotics. We evaluated the use and the cost of antibiotics using

the data from two case controlled studies of diabetic subjects with

recurrent neuropathic diabetic foot ulcers.

Methods: We identifed 22 subjects with type-2 diabetes who had

been treated in the past for neuropathic ulcers of the foot (Event 1,

E1), and who subsequently suffered recurrent ulcers with similar

characteristics (E2). In E2 the treatment was the same but the sub-

jects received a supplementation of Ar-Gl-HMB, and experienced

50% reduction of time to healing.

Results: During E1 we used 83 courses of antibiotics, versus 36

during E2 (Wilcoxon SR test = 0.002). The cost for treatment E1

was 17123.77 , versus 8537.8 in E2. The difference persists also

adding the cost of the supplement of 2586 (8537.8 +171223.77

= 1123.8 ).

Conclusions: The cost of the antibiotic treatment was reduced by

50% with the use of the formula. Because the time to healing was

shortened, both the direct costs (medication, surgery, nursing time,

etc) and the indirect costs (hospitalization, days of work lost) were

decreased .The use of a highly specialized nutrition reduces the

cost of the antibiotic treatment by about 50% and the auxiliary eco-

nomic and social burden of disease.

Keywords: Diabetic foot ulcer; Infection; Antibiotics

Introduction

Diabetic foot ulcers (DFU) are among the most invalidat-

ing and costly complications of diabetes [1]. These ulcers

appear in the diabetic environment and should be kept sepa-

rated from the ulcers appearing in non diabetics. Since this

environment is the sine qua non for the appearance of these

lesions, we suggest that the term treatment of the DFU is

a misnomer and should be substituted with treatment of

the diabetic subject with a foot ulcer [2]. These ulcers are

of two main types, of vascular and neuropathic origin, and

in many cases, there may be an overlap of these conditions

[3]. The initiating cause of the ulcers may be any event that

occurs also in nondiabetics, like trauma, pressure or burn.

Independent of their origin these ulcers share the common

characteristic of a delayed healing in comparison with the

same lesions appearing in nondiabetic individuals.

DFUs have a high social and personal cost [4]. There

are limited data in the literature on the topic of the economic

cost. Furthermore, the biology and the nutritional status of

the patient may interfere with the healing process. Because

of this complexity any economic evaluation is a generaliza-

tion. A retrospective study of men 40 - 64 years of age in a

managed care population found that the attributable cost for

foot ulcer care was $27,987 [5]. According to another study,

the total direct costs for healing of infected ulcers not requir-

ing amputation were 17500 $; the costs for lower extremity

Manuscript accepted for publication February 3, 2012

a

Department of Surgery, University of Nevada School of Medicine, Las

Vegas, USA

b

Department of Diabetes and Endocrinology, ASL RMH, Roma, Italy

c

Corresponding author: Patrizio Tatti. Email: info@patriziotatti.it

doi:10.4021/jem64w

26 27

J Endocrinol Metab 2012;2(1):26-31 Tatti et al

Articles The authors | Journal compilation J Endocrinol Metab and Elmer Press | www.jofem.org

amputation were 30000-35000 $ [6].

The present paper focuses on the neuropathic DFU in a

population of longstanding diabetic patients in an age range

of 45 - 70 years. The data of 12 subjects included for this

economic analysis were described in a 2010 paper [7], other

10 were presented in 2011 at the EWMA meeting in Brus-

sels [8].

Aim

We decided to evaluate the cost-beneft ratio of a blend of

arginine, glutamine and HMB used to improve the healing

of diabetic foot ulcers. In a previous study we demonstrated

that this blend could reduce the time to healing in diabetic

subjects with neuropathic foot ulcers from247 days to 83

days [7].

Summary of previous studies

We analyzed the data on the outcome of 22 longstanding

diabetic subjects with peripheral neuropathy and a relapsing

diabetic foot ulcer from two previous studies [7, 8]. These

subjects suffered in the past a DFU treated conventionally

(Event 1, Fig. 1) with curettage, local antisepsis and antibi-

otics. After the healing, either spontaneous or following a

surgical procedure, the ulcer recurred in the same location

and was treated with an oral blend of Arginine, glutamine

and -hydroxy--methylglutarate added on top of the same

care used for the previous Event (Event 2). The data of the

two events (E1 and E2) were compared. We considered these

subjects eligible for this study if the size of the recurring

ulcer was the same 1 mm. Each ulcer was accurately pho-

tographed at the different stages of evolution. The choice of

this protocol was based on some considerations: (1) this de-

sign is refective of what happens in clinical practice. (2) the

use of the same subject with a recurring lesion with identical

characteristics allows a perfect biologic match for a condi-

tion with an enormous number of variables.

All these subjects were treated with one or more of three

different antibiotics according to the clinical judgment and a

protocol included in the ISO manual of Accreditation, Ed 3.1

for internal use. In all these patients the time to healing and

the use of antibiotics was accurately recorded.

The male to female ratio was 7/15, the age range was

45 - 71, mean = 64. Fifteen of these subjects were retired, the

others actively working in commerce or manual work.

First ulcer

Recurring ulcer

Age (ys) 64.8 11 65.2 7

HbA1c (mmol/mol) at the time of presentation of

the ulcer

77.04 15 78.1 0.18 (P = NS)

Duration of the ulcer 215 48 81 16 (P 0.01)

BCMI

a

8.15 0.21 9.27 0.24 (P 0.05)

Table 1. Main Results

The data were analyzed with the SPSS Stat software ver 17 with the t-test for paired data.

a

data logarithmically

transformed for calculation.

Figure 1. Description of the study.

26 27

J Endocrinol Metab 2012;2(1):26-31 Use of Specialized Nutritional Supplement

Articles The authors | Journal compilation J Endocrinol Metab and Elmer Press | www.jofem.org

Materials and Methods

Before each period of treatment all patients underwent a

general physical examination and a routine check for blood

glucose,HbA1c, serum creatinine, complete blood count,

protein electrophoresis, electrolytes, and overnight (12 h)

urinary protein excretion. They also monitored their blood

glucose levels regularly. At the frst visit, the ulcer was pho-

tographed and measured. Body composition was also mea-

sured using bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA) with the

Akern Analyzer BIA 101 using the method described by

Dittmar. Among the BIA parameters we weekly monitored

the Body Cell Mass Index (BCMI). The medications were

adjusted to improve diabetes management and hyperten-

sion as needed. Curettage was performed if deemed appro-

priate by the physician. Wounds were cultured and infected

wounds were treated with appropriate antibiotics. Follow up

visits were scheduled at weekly intervals. At each visit the

treatment was further adjusted if indicated. In addition the

patients were referred to the dietician who determined their

energy needs based on age and activity level. For the over-

weight or obese patients, a slightly hypo-caloric diet, with

20% reduction of total intake was prescribed, and a highly

nutritional formula was added. The recommended protein

content of the diet was at least 20% taken at the three daily

meals. The dietary prescriptions were the same as for the

previous ulcer event (treatment 1, Fig. 1). The patients were

followed up weekly until their wounds were closed. For the

treatment of recurring DFU (Treament 2), the formula was

started at the second visit. Thus the only difference between

the treatment periods (treatment 1 vs 2) was the addition of

HMB, glutamine and arginine supplementation during treat-

ment 2. All the clinical data were recorded in the patients

electronic records together with the laboratory values and the

results of the body composition analysis. The time when the

patients frst observed the presence of wounds was used to

calculate the time of the frst medical evidence of the disease.

The details of these studies have already been presented.

Since the protocols used for both studies were identical

we created a single database of 22 subjects. The data on the

antibiotics used were obtained from the electronic medical

records and cross checked with the pharmacy records. The

data reported in Table 1 were analyzed with the T test for

paired samples (SPSS 19 package). The data on the use of

antibiotics that are pertinent to this study are in Table 2. The

data were analyzed per valuable cohort (per protocol), not

ITT since the compliance was 100%. The compliance was

regularly evaluated since 90% of the treatments were in day

hospital setting, and for the remaining 10% the subjects in

treatment retuned the empty boxes/vials of antibiotics.

Use of antibiotics

In our institution whenever needed we use three antibiotics

in courses according to what is stated in the ISO protocol ver

3.1 for internal use which was the same during treatment 1

and 2.

Results

The main results reported in table 1 are the reduction in

time to healing from 215 to 81 days (1/3), P = 0.001, and

the increased Body Cell Mass Index (BCMI). The BCMI is

a measure derived from the BIA and is the normalization of

the Body cell mass for the height of the subject. The number

of cycles of antibiotics and the cost of the treatments were

reduced to nearly one third (Table 2). In monetary terms

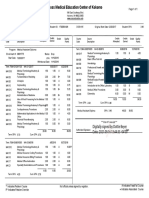

Table 2. Antibiotics Used and the Relative Cost per Course

Legend: Cost per cycle of the three antibiotics used: A = 89.48 ; B = 138.8 ; C = 624.15 .

Without Ar-G-B With Ar-G-B

Total number of cycles of antibiotics 83 36

Total number of cycles of antibiotic A 34 (3042 ) 20 (1789.6 )

Total number of cycles of antibiotic B 34 (4719.2 ) 12 (1665.6 )

Total number of cycles of antibiotic C 15 (9362.25 ) 4 (2496.6 )

Total cost of antibiotics 17123.77 5951.8

Cost of the nutritional supplement 0 2586

Total cost of treatment (antibiotics + supplement) 17123.77 8537.8

28 29

J Endocrinol Metab 2012;2(1):26-31

Tatti et al

Articles The authors | Journal compilation J Endocrinol Metab and Elmer Press | www.jofem.org

8537.8 vs. 17123.77 . Throughout the treatment 2 there

was also shift towards the less potent and less expensive

drugs. As reported in table 2 the number of cycles of anti-

biotic 1, with the minor cost was only slightly reduced from

34 to 20, while the cycles of the other two were reduced to

less than 1/3.

The compliance of the patient was evaluated by the

nurses in the hospital setting and by the empty boxes re-

turned in the outpatient setting. The need for antibiotics was

evaluated by the same two physicians who treated the previ-

ous infection and according to the laboratory results of the

antibiotic sensitivity tests Table 2 is a summary of the actual

use of antibiotics. To these should be added the direct costs

(medication, surgical interventions and dressings, nursing

time, etc) and the indirect costs (hospitalization, days of

work lost for the patient and the relatives). The reduction

in antibiotic usage can be only partially explained by the re-

duction in time to healing. During the treatment period there

was a shift towards the antibiotic A, of lower cost and minor

spectrum and power, since the infectious process was less

aggressive. This is entirely consistent with the antibacterial

and immunogenic properties of the blend we used and with

the improved nutrition.

Quality of life

To evaluate the change in quality of life we asked the patients

and their family members to fll a series of EQ-5D ques-

tionnaires (http://www.euroqol.org/fleadmin/user_upload/

Documenten/PDF/Languages/Sample_UK__English__EQ-

5D-3L.pdf) in the Day Hospital setting. The questionnaires

were auto administered with the help of a nurse only when

required. According to the results we considered the pres-

ence of an ulcer of the foot a reduction in quality of life of

0.4. Due to the wide variety of ulcers and the role of social/

working context this fgure is obviously an average. Since

the healing process started after the frst month in the treated

group (E2) we estimated an initial increase to 0.6 and a f-

nal increase to 0.9 in the second month. Although there was

complete healing the need for a continuous effort to prevent

the recurrences fxed this improvement to 0.9 rather than 1

(Fig. 2). The delayed and incomplete healing in the off treat-

ment period explains the fnal QUOL = 0.7. Since the period

of observation is calculated in months and not in years we

used the term QUOLm, where m = month.

We also calculated the cost: effectiveness ratio of the

treatment with the formula. The formula was qualy months

of extra time to healing of treatment 1 vs treatment 2. Treat-

ment 1: 0.4 4 = 1.6; Treatment 2: 0.9 4 = 3.2.

In other words treatment 2 allowed a gain of 4 extra

months at a quasi normal state

Since the average cost per patient in treatment 1 is

1426.917 (1723.77)/12 and for treatment 2 is 711.4833

(8537.8/12) the net difference is a saving of 178 per month

for the antibiotic treatment while obtaining a 0.9 QOL. The

extra costs for the medications of a nonhealing ulcers and the

time lost are not included in this calculation.

Discussion

During the period of treatment of the recurring ulcers (treat-

ment 2) with the addiction of a blend of Arginine, Glurtamine

and HMB, we used nearly 1/3 of the antibiotics used in ab-

sence of the blend (treatment 1). Notably in treatment 2 we

shifted towards the oral treatment and the less costly and less

Figure 2. Quality of life/month.

28 29

J Endocrinol Metab 2012;2(1):26-31 Use of Specialized Nutritional Supplement

Articles The authors | Journal compilation J Endocrinol Metab and Elmer Press | www.jofem.org

powerful antibiotics. Such difference probably refects a re-

duced aggressiveness of the infection, and a more powerful

immune host response. This also led to a consistent reduction

in costs of the antibiotics and all the accessory therapy (nurs-

ing, requirements for the injections) [9]. Of course the rapid

healing of the ulcer during treatment 2 allowed for a consid-

erable saving in costs of local medications and the hospital

personnel, and time lost both for the patient and his family,

and should be added to the economic advantage. In summary

the addiction of the blend reduced the economic and social

costs of the ulcer both shortening the time to healing and

allowing for the use of less, and less costly antibiotics. This

result is probably due to the interaction of many factors (Fig.

3). We think that argine in the blend reduced the bacterial

load and potentiated the immunologic process [10-12], thus

reversing the infection/infammation and allowing the repair

of the tissue. Arginine also has a vasodilator action [13] that

was exploited for male erectile dysfunction before the intro-

duction of the phosphodiesterase inhibitors. Glutamine also

has a spectrum of positive effects [14], notably stimulation

of protein synthesis, support of the immune function [15,

16] and of the intestinal mucosal integrity [17]. HMB is

normally present in the muscle, is an active leucine metabo-

lite and a potent stimulator of mTOR (Mammalian Target

of Rapamycin), an intracellular protein controlling protein

synthesis [18, 19]. Due to its anabolic property, the substance

is widely used by the athletes worldwide and to reverse the

effects of aging [20]. In our experience the use of this blend

reduced to 1/3 the time to healing in a group of 12 diabetic

patients while improving the lean body mass [21].

This study has both weaknesses and strengths. This is

not a Randomized Controlled Study (RCS). However the

RCTs that are considered the gold standard have enormous

diffculties with ulcers appearing in diabetic subjects, be-

cause the evolution of the ulcers is conditioned by a variety

of factors that are extremely diffcult to keep under control

[22]. Among them the intrinsic variability of the wound, the

presence of infections, the location of the wound, the use of

ill ftting shoes, time spent with the shoes, the general medi-

cal condition of the subjects and the blood glucose control.

This diversity can be partially reduced by the use of one of

the many classifcations available in the literature, but no one

of them accounts for the wide spectrum of concomitant con-

ditions that can interfere with the healing process. One of the

most important and often overlooked among these factors

is the glycemic control. HbA1c is considered the gold stan-

dard in evaluating glycaemic control in a diabetic patient,

but may be variably infuenced by both fasting and postpran-

dial blood glucose levels, and each of these has a different

pathophysiological meaning. Currently we do not even know

if and to what extent these phenomena can interfere with the

healing of the ulcer. It is also probable that we ignore some

of the individual genetic or acquired characteristics that can

interfere with the tissue repair. Thus is extremely diffcult

to fnd a population with the same characteristics and an ef-

fective randomization would require a very large number of

subjects. Consequently our choice of subjects affected by a

recurring ulcer with the same characteristics allows to keep

Figure 3. Economic impact of the ulcer.

30 31

J Endocrinol Metab 2012;2(1):26-31

Tatti et al

Articles The authors | Journal compilation J Endocrinol Metab and Elmer Press | www.jofem.org

under control most of the biologic variability of the ulcer.

The incidence of DFUs is very high. In a recent study,

among 8,905 patients identifed with type 1 or type 2 diabe-

tes, 514 developed a foot ulcer over 3 years of observation

(cumulative incidence 5.8%) [22], and a reduction of nearly

50% in the cost has an important bearing of the national

health system. The use of this blend may help reduce these

costs while improving the well being of the diabetic subjects.

References

1. Ortegon MM, Redekop WK, Niessen LW. Cost-effec-

tiveness of prevention and treatment of the diabetic foot:

a Markov analysis. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(4):901-907.

2. Tatti P, Barber A , Role of nutrition in ulcer healing . In

Diabetic Foot. ISBN 978-953-307-717-8.

3. American Diabetes Association. Clinical Care of the

diabetic Foot, 2nd Edition (2010).

4. Holzer SE, Camerota A, Martens L, Cuerdon T, Crystal-

Peters J, Zagari M. Costs and duration of care for lower

extremity ulcers in patients with diabetes. Clin Ther.

1998;20(1):169-181.

5. Ramsey SD, Newton K, Blough D, McCulloch DK,

Sandhu N, Reiber GE, Wagner EH. Incidence, out-

comes, and cost of foot ulcers in patients with diabetes.

Diabetes Care. 1999;22(3):382-387.

6. Ragnarson Tennvall G, Apelqvist J. Health-economic

consequences of diabetic foot lesions. Clin Infect Dis.

2004;39 Suppl 2:S132-139.

7. Tatti P, Barber A . The use of a specialized nutritional

supplement for diabetic foot ulcers reduces the use of

antibiotics and the cost of treatment. Presented at the

EWMA 2011, 25-27 May, Brussels.

8. Tatti P, Barber A. EWMA Journal, Nutritional Supple-

ment is Associated with a Reduction in Healing Time

and Improvement of Fat Free Body Mass in Patients

with Diabetic Foot Ulcers.Vol 10(3), Oct 2010:13-18.

9. Standards of medical care in diabetes--2011. Diabetes

Care. 2011;34 Suppl 1:S11-61.

10. Wanasen N, Soong L. L-arginine metabolism and its

impact on host immunity against Leishmania infection.

Immunol Res. 2008;41(1):15-25.

11. Barbul A, Lazarou SA, Efron DT, Wasserkrug HL, Efron

G. Arginine enhances wound healing and lymphocyte im-

mune responses in humans. Surgery. 1990;108(2):331-

336; discussion 336-337.

12. Witte MB, Barbul A. Arginine physiology and its im-

plication for wound healing. Wound Repair Regen.

2003;11(6):419-423.

13. Rhodes P, Barr CS, Struthers AD. Arginine, lysine and

ornithine as vasodilators in the forearm of man. Eur J

Clin Invest. 1996;26(4):325-331.

14. Peng X, Yan H, You Z, Wang P, Wang S. Clinical and

protein metabolic effcacy of glutamine granules-sup-

plemented enteral nutrition in severely burned patients.

Burns. 2005;31(3):342-346.

15. Wilmore DW. The effect of glutamine supplementation

in patients following elective surgery and accidental in-

jury. J Nutr. 2001;131(9 Suppl):2543S-2549S; discus-

sion 2550S-2541S.

16. Mocchegiani E, Nistico G, Santarelli L, Fabris N. Ef-

fect of L-arginine on thymic function. Possible role of

L-arginine: Nitric oxide (no) pathway. Arch Gerontol

Geriatr. 1994;19 Suppl 1:163-170.

17. van der Hulst RR, van Kreel BK, von Meyenfeldt MF,

Brummer RJ, Arends JW, Deutz NE, Soeters PB. Glu-

tamine and the preservation of gut integrity. Lancet.

1993;341(8857):1363-1365.

18. Manzano M, et Al. Is -hydroxy--methylbutyrate

(HMB) the bioactive metabolite of L-leucine (LEU) in

muscle? Molecular evidence and potential implications.

Abstract presented at: European Society for Clinical Nu-

trition and Metabolism 31st Congress; Vienna, Austria;

August 29-September 1, (2009). Abstract P267.

19. Baxter J et Al. 4th cachexia conference 2007, Abstract

1.18.

20. Wilson GJ, Wilson JM, Manninen AH. Effects of beta-

hydroxy-beta-methylbutyrate (HMB) on exercise per-

formance and body composition across varying levels of

age, sex, and training experience: A review. Nutr Metab

(Lond). 2008;5:1.

21. Tatti P, Barber AB. Nutritional supplement is associated

with a reduction in healing time and improvement of

fat-free body mass in patients with diabetic foot ulcers.

EWMA Journal vol 10 no 3(2010): 13-17.

22. Armstrong DG, Lavery LA. Diabetic foot ulcers: pre-

vention, diagnosis and classifcation. Am Fam Physi-

cian. 1998;57(6):1325-1332, 1337-1328.

30 31

Você também pode gostar

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (344)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- ATLS Post TestDocumento1 páginaATLS Post Testanon_57896987836% (56)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (120)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- Nurse Brain Sheet Telemetry Unit SBARDocumento1 páginaNurse Brain Sheet Telemetry Unit SBARvsosa624Ainda não há avaliações

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- Epidemiology Triangle of MalariaDocumento3 páginasEpidemiology Triangle of MalariaArslan Bashir100% (8)

- NCLEX Random FactsDocumento34 páginasNCLEX Random FactsLegnaMary100% (8)

- Drugs NclexDocumento30 páginasDrugs Nclexawuahboh100% (1)

- King Rush MoreDocumento1 páginaKing Rush MoreawuahbohAinda não há avaliações

- Article For JournalDocumento6 páginasArticle For JournalawuahbohAinda não há avaliações

- Oop Say You Know MeDocumento1 páginaOop Say You Know MeawuahbohAinda não há avaliações

- The BSN Job Search: Interview Preparation: Telling Your StoryDocumento25 páginasThe BSN Job Search: Interview Preparation: Telling Your StoryawuahbohAinda não há avaliações

- HandOff SampleToolsDocumento9 páginasHandOff SampleToolsOllie EvansAinda não há avaliações

- Massachusetts Department of Public HealthDocumento24 páginasMassachusetts Department of Public HealthawuahbohAinda não há avaliações

- Middle Age Adult Health History Assignment Guidelines N315 Fall 2013Documento23 páginasMiddle Age Adult Health History Assignment Guidelines N315 Fall 2013awuahbohAinda não há avaliações

- Pharm NclexDocumento9 páginasPharm NclexawuahbohAinda não há avaliações

- Article For CET CHFDocumento5 páginasArticle For CET CHFawuahbohAinda não há avaliações

- PolypharmacyDocumento24 páginasPolypharmacySurina Zaman HuriAinda não há avaliações

- Probability of A or B and A and B-1Documento2 páginasProbability of A or B and A and B-1awuahbohAinda não há avaliações

- EBP Article 1Documento11 páginasEBP Article 1awuahbohAinda não há avaliações

- Random FactsDocumento338 páginasRandom Factscyram81100% (1)

- STDA VaricealDocumento8 páginasSTDA VaricealDeisy de JesusAinda não há avaliações

- Therapeutic CommunicationDocumento1 páginaTherapeutic CommunicationawuahbohAinda não há avaliações

- EBP Article 3Documento6 páginasEBP Article 3awuahbohAinda não há avaliações

- Critical Thinking StrategiesDocumento3 páginasCritical Thinking StrategiesawuahbohAinda não há avaliações

- Tips On Answering NclexDocumento4 páginasTips On Answering NclexawuahbohAinda não há avaliações

- ENT Throat and EsophagusDocumento41 páginasENT Throat and EsophagusMUHAMMAD HASAN NAGRAAinda não há avaliações

- Debate 3 Youth Incarceration in Adult PrisonsDocumento6 páginasDebate 3 Youth Incarceration in Adult PrisonsawuahbohAinda não há avaliações

- Patient Report FormDocumento1 páginaPatient Report FormawuahbohAinda não há avaliações

- Does Prospective Payment Increase Hospital (In) Efficiency? Evidence From The Swiss Hospital SectorDocumento24 páginasDoes Prospective Payment Increase Hospital (In) Efficiency? Evidence From The Swiss Hospital SectorawuahbohAinda não há avaliações

- Article For CET CHFDocumento5 páginasArticle For CET CHFawuahbohAinda não há avaliações

- Article For JournalDocumento6 páginasArticle For JournalawuahbohAinda não há avaliações

- Article For Journal 4-18-14Documento8 páginasArticle For Journal 4-18-14awuahbohAinda não há avaliações

- Med Surg BurnsDocumento8 páginasMed Surg BurnsawuahbohAinda não há avaliações

- Article For Jouranal 2 (498P)Documento5 páginasArticle For Jouranal 2 (498P)awuahbohAinda não há avaliações

- Lecture - Maternal Health Concerns (Part 1)Documento1 páginaLecture - Maternal Health Concerns (Part 1)Rovilyn DizonAinda não há avaliações

- A03 - Sangita Singh - FPSC Naini 641A, Chak Raghunath, Mirzapur Road, ALLAHABAD, UP 211008Documento2 páginasA03 - Sangita Singh - FPSC Naini 641A, Chak Raghunath, Mirzapur Road, ALLAHABAD, UP 211008mohd arkamAinda não há avaliações

- Birla Institute of Technology & Science, Pilani Work Integrated Learning Programmes DigitalDocumento10 páginasBirla Institute of Technology & Science, Pilani Work Integrated Learning Programmes DigitalAAKAinda não há avaliações

- Pokemon 5th Edition - Gen I, II, & IIIDocumento265 páginasPokemon 5th Edition - Gen I, II, & IIIJames TonkinAinda não há avaliações

- Ethics Case StudyDocumento4 páginasEthics Case StudycasscactusAinda não há avaliações

- Title: Anthrax: Subtitles Are FollowingDocumento14 páginasTitle: Anthrax: Subtitles Are FollowingSyed ShahZaib ShahAinda não há avaliações

- How To Dominate The Ventilator: Spinning DialsDocumento5 páginasHow To Dominate The Ventilator: Spinning DialsIgnacia Cid PintoAinda não há avaliações

- ĐỀ THI THỬ 2021 - THPT QUẢNG XƯƠNG - THANH HOÁDocumento11 páginasĐỀ THI THỬ 2021 - THPT QUẢNG XƯƠNG - THANH HOÁNguyen NhanAinda não há avaliações

- Explant Sterilization TechniqueDocumento4 páginasExplant Sterilization TechniqueHaripriya88% (8)

- Motility and Fertility CorrelationDocumento14 páginasMotility and Fertility CorrelationvetlakshmiAinda não há avaliações

- Surgical DressingDocumento7 páginasSurgical DressingGabz GabbyAinda não há avaliações

- Criteria-Based Return To SprintingDocumento7 páginasCriteria-Based Return To SprintingJorge Aguirre GonzalezAinda não há avaliações

- Airway Publish Irfan AltafDocumento3 páginasAirway Publish Irfan AltafTAUSEEFA JANAinda não há avaliações

- Loads of Continuous Mechanics For Uprighting The Second Molar On The Second Molar and PremolarDocumento8 páginasLoads of Continuous Mechanics For Uprighting The Second Molar On The Second Molar and PremolarAlvaro ChacónAinda não há avaliações

- Goodman, Ashley SignedDocumento1 páginaGoodman, Ashley SignedAshley GoodmanAinda não há avaliações

- Ieltsfever Academic Reading Practcie Test 50 PDFDocumento11 páginasIeltsfever Academic Reading Practcie Test 50 PDFLOAinda não há avaliações

- Philadelphia Adventist ChurchDocumento2 páginasPhiladelphia Adventist ChurchMETALAinda não há avaliações

- Itm Dosage FormsDocumento15 páginasItm Dosage FormsArun Singh N JAinda não há avaliações

- Viva Q-Ans Class XiiDocumento10 páginasViva Q-Ans Class Xiipavani pavakiAinda não há avaliações

- Psychology Project CbseDocumento17 páginasPsychology Project CbseJiya GeorgeAinda não há avaliações

- The Power of ConflictDocumento4 páginasThe Power of Conflictapi-459276089Ainda não há avaliações

- Kel 3 A Midwifery Model of Care ForDocumento13 páginasKel 3 A Midwifery Model of Care ForWawa KurniaAinda não há avaliações

- Daily Lesson Log Week 2Documento7 páginasDaily Lesson Log Week 2Jolie Ann De GuzmanAinda não há avaliações

- Communicable Disease QuizDocumento2 páginasCommunicable Disease QuizPlacida Mequiabas National High SchoolAinda não há avaliações

- Resume Fall 2022 PDFDocumento2 páginasResume Fall 2022 PDFapi-663012445Ainda não há avaliações

- Master Summary of Parenting - I Read 16 Parenting Books To Create This Master SummaryDocumento16 páginasMaster Summary of Parenting - I Read 16 Parenting Books To Create This Master SummarySaurabh Jain CAAinda não há avaliações

- Testicular Cancer (Teratoma Testis)Documento7 páginasTesticular Cancer (Teratoma Testis)Witha Lestari AdethiaAinda não há avaliações

- Good Morning Class! February 10, 2021: Tle-CarpentryDocumento57 páginasGood Morning Class! February 10, 2021: Tle-CarpentryGlenn Fortades SalandananAinda não há avaliações