Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Admin 27-29

Enviado por

MJ Ferma0 notas0% acharam este documento útil (0 voto)

22 visualizações3 páginasadmin case 27-29

Título original

ADMIN 27-29

Direitos autorais

© © All Rights Reserved

Formatos disponíveis

DOCX, PDF, TXT ou leia online no Scribd

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoadmin case 27-29

Direitos autorais:

© All Rights Reserved

Formatos disponíveis

Baixe no formato DOCX, PDF, TXT ou leia online no Scribd

0 notas0% acharam este documento útil (0 voto)

22 visualizações3 páginasAdmin 27-29

Enviado por

MJ Fermaadmin case 27-29

Direitos autorais:

© All Rights Reserved

Formatos disponíveis

Baixe no formato DOCX, PDF, TXT ou leia online no Scribd

Você está na página 1de 3

ADMIN 27-29

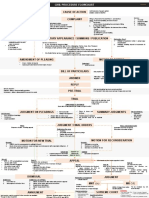

27. PANAMA REFINING VS RYAN

Facts:

Congress enacted a provision of the National Industrial Act (NIRA) that gave the President the power to prohibit the

transportation of petroleum products in excess of the amount permitted by state law. Based on this provision, the President

made an Executive Order enacting such a prohibition. The Plaintiff, Panama Refining Co. (Plaintiff) brought suit to enjoin the

Defendants, certain government officials (Defendant), from enforcing the Executive Order. The District Court granted a

permanent injunction against enforcement, but the Court of Appeals reversed.

Issue:

May Congress delegate unrestricted law-making authority to the President?

Held:

No, congressional delegation of power to the executive branch must be specific and limited. The NIRA did not include any

policy guidelines for prohibiting or not prohibiting the transportation of petroleum production in excess of state allowances.

The President was granted unfettered discretion. Congress let the matter to him to be dealt with as he pleased. Under the

United States Constitution (Constitution) Congress is not allowed to abdicate or transfer its essential legislative powers.

Congress simply left the matter to the President (in deciding the circumstances and conditions under which the transportation

of petroleum products should be prohibited) without setting standards or rules to be followed. Congress cannot delegate to

others the essential legislative functions with which it was vested. If the Supreme Court of the United States (Supreme Court)

were to hold the legislation valid, Congress would be free to delegate authority at will to the President, another officer, or an

administrative body. The delegation of authority was unlawful and invalid.

28. ABAKADA vs ERMITA

Facts: On May 24, 2005, the President signed into law Republic Act 9337 or the VAT Reform Act. Before the law took effect on

July 1, 2005, the Court issued a TRO enjoining government from implementing the law in response to a slew of petitions for

certiorari and prohibition questioning the constitutionality of the new law. The challenged section of R.A. No. 9337 is the

common proviso in Sections 4, 5 and 6: That the President, upon the recommendation of the Secretary of Finance, shall,

effective January 1, 2006, raise the rate of value-added tax to 12%, after any of the following conditions has been satisfied:

(i) Value-added tax collection as a percentage of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) of the previous year exceeds two and four-fifth

percent (2 4/5%); or (ii) National government deficit as a percentage of GDP of the previous year exceeds one and one-half

percent (1%)

Petitioners allege that the grant of stand-by authority to the President to increase the VAT rate is an abdication by Congress of

its exclusive power to tax because such delegation is not covered by Section 28 (2), Article VI Consti. They argue that VAT is a

tax levied on the sale or exchange of goods and services which cant be included within the purview of tariffs under the

exemption delegation since this refers to customs duties, tolls or tribute payable upon merchandise to the government and

usually imposed on imported/exported goods. They also said that the President has powers to cause, influence or create the

conditions provided by law to bring about the conditions precedent. Moreover, they allege that no guiding standards are made

by law as to how the Secretary of Finance will make the recommendation.

Issue: Whether or not the RA 9337's stand-by authority to the Executive to increase the VAT rate, especially on account of the

recommendatory power granted to the Secretary of Finance, constitutes undue delegation of legislative power? NO

Held: The powers which Congress is prohibited from delegating are those which are strictly, or inherently and exclusively,

legislative. Purely legislative power which can never be delegated is the authority to make a complete law- complete as to the

time when it shall take effect and as to whom it shall be applicable, and to determine the expediency of its enactment. It is the

nature of the power and not the liability of its use or the manner of its exercise which determines the validity of its delegation.

The exceptions are:

(a) delegation of tariff powers to President under Constitution

(b) delegation of emergency powers to President under Constitution

(c) delegation to the people at large

(d) delegation to local governments

(e) delegation to administrative bodies

For the delegation to be valid, it must be complete and it must fix a standard. A sufficient standard is one which defines

legislative policy, marks its limits, maps out its boundaries and specifies the public agency to apply it.

In this case, it is not a delegation of legislative power BUT a delegation of ascertainment of facts upon which enforcement and

administration of the increased rate under the law is contingent. The legislature has made the operation of the 12% rate

effective January 1, 2006, contingent upon a specified fact or condition. It leaves the entire operation or non-operation of the

12% rate upon factual matters outside of the control of the executive. No discretion would be exercised by the President.

Highlighting the absence of discretion is the fact that the word SHALL is used in the common proviso. The use of the word

SHALL connotes a mandatory order. Its use in a statute denotes an imperative obligation and is inconsistent with the idea of

discretion.

Congress does not abdicate its functions or unduly delegate power when it describes what job must be done, who must do it,

and what is the scope of his authority; in our complex economy that is frequently the only way in which the legislative process

can go forward.

There is no undue delegation of legislative power but only of the discretion as to the execution of a law. This is constitutionally

permissible. Congress did not delegate the power to tax but the mere implementation of the law.

REVIEW CENTER ASSOCIATION OF THE PHIL VS ERMITA

Facts: There was a report that handwritten copies of two sets of 2006 Nursing Board examination were circulated during the

examination period among examinees reviewing at the R.A. Gapuz Review Center and Inress Review Center. The examinees

were provided with a list of 500 questions and answers in two of the examinations five subjects, particularly Tests III

(Psychiatric Nursing) and V (Medical-Surgical Nursing). The PRC later admitted the leakage and traced it to two Board of Nursing

members. Exam results came out but Court of Appeals restrained the PRC from proceeding with the oath-taking of the

successful examinees.

President GMA ordered for a re-examination and issued EO 566 which authorized the CHED to supervise the establishment

and operation of all review centers and similar entities in the Philippines. CHED Chairman Puno approved CHED Memorandum

Order No. 49 series of 2006 (Implementing Rules and Regulations). Review Center Association of the Philippines (petitioner), an

organization of independent review centers, asked the CHED to "amend, if not withdraw" the IRR arguing, among other things,

that giving permits to operate a review center to Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) or consortia of HEIs and professional

organizations will effectively abolish independent review centers. CHED Chairman Puno however believed that suspending the

implementation of the IRR would be inconsistent with the mandate of EO 566.

Issues: 1. Whether EO 566 is an unconstitutional exercise by the Executive of legislative power as it expands the CHEDs

jurisdiction *Yes, it expands CHEDs jurisdiction, hence unconsititutional+; and Whether the RIRR is an invalid exercise of the

Executives rule-making power. [Yes, it is invalid.]

Held: 1. The scopes of EO 566 and the RIRR clearly expand the CHEDs coverage under RA 7722. The CHEDs coverage under RA

7722 is limited to public and private institutions of higher education and degree-granting programs in all public and private

post-secondary educational institutions. EO 566 directed the CHED to formulate a framework for the regulation of review

centers and similar entities.

The definition of a review center under EO 566 shows that it refers to one which offers "a program or course of study that is

intended to refresh and enhance the knowledge or competencies and skills of reviewees obtained in the formal school setting

in preparation for the licensure examinations" given by the PRC. It does not offer a degree-granting program that would put it

under the jurisdiction of the CHED. A review course is only intended to "refresh and enhance the knowledge or competencies

and skills of reviewees." Thus, programs given by review centers could not be considered "programs x x x of higher learning"

that would put them under the jurisdiction of the CHED. "Higher education," is defined as "education beyond the secondary

level or "education provided by a college or university."

Further, the "similar entities" in EO 566 cover centers providing "review or tutorial services" in areas not covered by licensure

examinations given by the PRC, which include, although not limited to, college entrance examinations, Civil Services

examinations, and tutorial services. These review and tutorial services hardly qualify as programs of higher learning.

2. ) The exercise of the Presidents residual powers under Section 20, Title I of Book III of EO (invoked by the OSG to justify

GMAs action) requires legislation; as the provision clearly states that the exercise of the Presidents other powers and

functions has to be "provided for under the law." There is no law granting the President the power to amend the functions of

the CHED. The President has no inherent or delegated legislative power to amend the functions of the CHED under RA 7722.

The line that delineates Legislative and Executive power is not indistinct. Legislative power is "the authority, under the

Constitution, to make laws, and to alter and repeal them." The Constitution, as the will of the people in their original,

sovereign and unlimited capacity, has vested this power in the Congress of the Philippines. Any power, deemed to be legislative

by usage and tradition, is necessarily possessed by Congress, unless the Constitution has lodged it elsewhere.

The President has control over the executive department, bureaus and offices. Meaning, he has the authority to assume

directly the functions of the executive department, bureau and office, or interfere with the discretion of its officials. Corollary

to the power of control, he is granted administrative power. Administrative power is concerned with the work of applying

policies and enforcing orders as determined by proper governmental organs. It enables the President to fix a uniform standard

of administrative efficiency and check the official conduct of his agents. To this end, he can issue administrative orders, rules

and regulations. An administrative order is an ordinance issued by the President which relates to specific aspects in the

administrative operation of government. It must be in harmony with the law and should be for the sole purpose of

implementing the law and carrying out the legislative policy.

Since EO 566 is an invalid exercise of legislative power, the RIRR is also an invalid exercise of the CHEDs quasi-legislative

power. Administrative agencies exercise their quasi-legislative or rule-making power through the promulgation of rules and

regulations. The CHED may only exercise its rule-making power within the confines of its jurisdiction under RA 7722. But The

RIRR covers review centers and similar entities.

Você também pode gostar

- A Letter From Albert Einstein To His DaughterDocumento2 páginasA Letter From Albert Einstein To His DaughterMJ Ferma100% (3)

- 3RD Case - BO IIDocumento1 página3RD Case - BO IIMJ FermaAinda não há avaliações

- Hmo CzncellationDocumento1 páginaHmo CzncellationMJ FermaAinda não há avaliações

- Admin 36 37 38Documento6 páginasAdmin 36 37 38MJ FermaAinda não há avaliações

- East Timor Case DigestDocumento9 páginasEast Timor Case DigestMJ FermaAinda não há avaliações

- Tax On Individuals (Table)Documento1 páginaTax On Individuals (Table)MJ FermaAinda não há avaliações

- People vs. AgojoDocumento15 páginasPeople vs. AgojoMJ FermaAinda não há avaliações

- Disqualification For LGCDocumento32 páginasDisqualification For LGCMJ FermaAinda não há avaliações

- G.R. No. L-20569 October 29, 1923 THE PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINE ISLANDS, Plaintiff-Appellee, J. J. KOTTINGER, Defendant-AppellantDocumento6 páginasG.R. No. L-20569 October 29, 1923 THE PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINE ISLANDS, Plaintiff-Appellee, J. J. KOTTINGER, Defendant-AppellantMJ FermaAinda não há avaliações

- Lutz Vs Araneta DigestDocumento1 páginaLutz Vs Araneta DigestMJ Ferma100% (2)

- SPL Cases 65-75Documento12 páginasSPL Cases 65-75MJ FermaAinda não há avaliações

- Samar Mining CoDocumento3 páginasSamar Mining CoMJ FermaAinda não há avaliações

- Disqualification For LGCDocumento32 páginasDisqualification For LGCMJ FermaAinda não há avaliações

- Deeds Relating To Real Estate Not Registered Under Act Numbered Four Hundred and Ninety-Six or Under The Spanish Mortgage Law. - NoDocumento4 páginasDeeds Relating To Real Estate Not Registered Under Act Numbered Four Hundred and Ninety-Six or Under The Spanish Mortgage Law. - NoMJ FermaAinda não há avaliações

- G.R. No. L-29146 August 5, 1985 Application For Registration of Title. Benita Salao, Applicant-Appellee, BENITO CRISOSTOMO, Oppositor-AppellantDocumento37 páginasG.R. No. L-29146 August 5, 1985 Application For Registration of Title. Benita Salao, Applicant-Appellee, BENITO CRISOSTOMO, Oppositor-AppellantMJ FermaAinda não há avaliações

- Employee'S Compensation and State Insurance Fund PurposeDocumento4 páginasEmployee'S Compensation and State Insurance Fund PurposeMJ FermaAinda não há avaliações

- Esmeraldo Rivera Vs People of The PhilippinesDocumento2 páginasEsmeraldo Rivera Vs People of The PhilippinesMJ FermaAinda não há avaliações

- Case On Line For Civil ProcedureDocumento5 páginasCase On Line For Civil ProcedureMJ FermaAinda não há avaliações

- Malaga vs. Penachos (Digest)Documento16 páginasMalaga vs. Penachos (Digest)MJ FermaAinda não há avaliações

- Group 2 - Ferma People vs. Nicolas, 387 SCRA 638, (G.R. No. 135877) FactsDocumento1 páginaGroup 2 - Ferma People vs. Nicolas, 387 SCRA 638, (G.R. No. 135877) FactsMJ FermaAinda não há avaliações

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (400)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (895)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (266)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (345)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (121)

- Intern at Ubadvocate Email-Ra Jkumarmeena 352080612Documento2 páginasIntern at Ubadvocate Email-Ra Jkumarmeena 352080612RajkumarAinda não há avaliações

- CPC and Limitation by MP Jain PDFDocumento3.145 páginasCPC and Limitation by MP Jain PDFDevansh Malhotra50% (2)

- Sumilao Case Opinion and ResolutionDocumento6 páginasSumilao Case Opinion and ResolutionAreeAinda não há avaliações

- Ungria Vs CA DigestDocumento1 páginaUngria Vs CA DigestAziel Marie C. GuzmanAinda não há avaliações

- Preliminary Consideration (5 Cases)Documento238 páginasPreliminary Consideration (5 Cases)Mayrll SantosAinda não há avaliações

- 11 CUA vs. TANDocumento4 páginas11 CUA vs. TANRicardo100% (1)

- Miller FlyerDocumento1 páginaMiller Flyerthe kingfishAinda não há avaliações

- Newsounds Broadcasting Network Inc. v. DyDocumento20 páginasNewsounds Broadcasting Network Inc. v. Dyjaieleigh0% (1)

- Insurance - 2014 - de Leon Book Digest PDFDocumento69 páginasInsurance - 2014 - de Leon Book Digest PDFMiley LangAinda não há avaliações

- United States of America, Ex Rel., Frank Earl Senk, S-0026 v. J. R. Brierley, Superintendent, 471 F.2d 657, 3rd Cir. (1973)Documento6 páginasUnited States of America, Ex Rel., Frank Earl Senk, S-0026 v. J. R. Brierley, Superintendent, 471 F.2d 657, 3rd Cir. (1973)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- Family Law II 2nd Year Sem-IV Roll No 4 Pratiksha BhagatDocumento28 páginasFamily Law II 2nd Year Sem-IV Roll No 4 Pratiksha Bhagatpratiksha lakdeAinda não há avaliações

- Jaka Investment Vs CirDocumento3 páginasJaka Investment Vs CirStephanie Mariz KhanAinda não há avaliações

- Law245 Malaysia Legal System - Tort of DefamationDocumento3 páginasLaw245 Malaysia Legal System - Tort of DefamationMyrain ImendyAinda não há avaliações

- Merit Vs Federal Express-SP119658Documento16 páginasMerit Vs Federal Express-SP119658Jason CabreraAinda não há avaliações

- Gsis v. CA DigestDocumento2 páginasGsis v. CA DigestKian Fajardo67% (3)

- March Free Chapter - Until The End of Time by Danielle SteelDocumento37 páginasMarch Free Chapter - Until The End of Time by Danielle SteelRandomHouseAU75% (4)

- Ca PDFDocumento670 páginasCa PDFRyan WaltersAinda não há avaliações

- Sam Zherka, Strip Club Owner, Named To Phantom Mount Vernon Police BoardDocumento4 páginasSam Zherka, Strip Club Owner, Named To Phantom Mount Vernon Police BoardTimothy O'ConnorAinda não há avaliações

- Heirs of Augusto L. Salas, Jr. vs. Laperal Realty Corporation, Et Al. G.R. NO. 135362Documento4 páginasHeirs of Augusto L. Salas, Jr. vs. Laperal Realty Corporation, Et Al. G.R. NO. 135362Edwin Villa100% (1)

- Aicpa Reg 6Documento170 páginasAicpa Reg 6Natasha Declan100% (1)

- Ja Anne GazaDocumento8 páginasJa Anne GazaRhows BuergoAinda não há avaliações

- Bolinao Electronics Corporation Vs Brigido ValenciaDocumento2 páginasBolinao Electronics Corporation Vs Brigido ValenciaShiela PilarAinda não há avaliações

- 2 Sps. Aboitiz vs. Sps. Po 2017Documento2 páginas2 Sps. Aboitiz vs. Sps. Po 2017krizzledelapenaAinda não há avaliações

- The Victorian Court HierarchyDocumento18 páginasThe Victorian Court HierarchyLencesiAinda não há avaliações

- Province of Zamboanga v. City of ZamboangaDocumento4 páginasProvince of Zamboanga v. City of Zamboangajrvyee100% (1)

- Tacuboy: Original Jurisdiction Appellate JurisdictionDocumento2 páginasTacuboy: Original Jurisdiction Appellate JurisdictionReuel Realin93% (96)

- BDO Unibank Vs Sps LocsinDocumento8 páginasBDO Unibank Vs Sps LocsinAlvin HalconAinda não há avaliações

- Sample Opposition To Motion For New Trial in California DivorceDocumento3 páginasSample Opposition To Motion For New Trial in California DivorceStan BurmanAinda não há avaliações

- Demand NoteDocumento4 páginasDemand NoteLuke CooperAinda não há avaliações

- Motion For Summary Judgment - File Stamped - 12-10-18 (00679927)Documento12 páginasMotion For Summary Judgment - File Stamped - 12-10-18 (00679927)lamzAinda não há avaliações