Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

33 Article

Enviado por

jinny1_00 notas0% acharam este documento útil (0 voto)

8 visualizações3 páginasarticle

Título original

33article

Direitos autorais

© © All Rights Reserved

Formatos disponíveis

PDF, TXT ou leia online no Scribd

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoarticle

Direitos autorais:

© All Rights Reserved

Formatos disponíveis

Baixe no formato PDF, TXT ou leia online no Scribd

0 notas0% acharam este documento útil (0 voto)

8 visualizações3 páginas33 Article

Enviado por

jinny1_0article

Direitos autorais:

© All Rights Reserved

Formatos disponíveis

Baixe no formato PDF, TXT ou leia online no Scribd

Você está na página 1de 3

RESEARCH

BRITISH DENTAL JOURNAL VOLUME 201 NO. 1 JUL 8 2006 33

Does completing a dental anxiety questionnaire

increase anxiety? A randomised controlled trial

with adults in general dental practice

G. M. Humphris,

1

H. M. M. Clarke

2

and R. Freeman

3

The assessment of dental anxiety can be achieved by using brief multi-

item scales.

Objective To test the null hypothesis that completing the Modified

Dental Anxiety Scale had no immediate influence on patient state

anxiety.

Outcome measure Speilberger State Anxiety Inventory-6 item Short

Form.

Study design Randomised controlled trial.

Participants Patients (n = 1,028) attending 18 dental practices in

Northern Ireland were invited to participate.

Results Twenty-four patients refused (response rate 98%) providing

1,004 patients (mean age = 41 years, range = 16 to 90 years; 65%

female) for analysis. Patients who completed the dental anxiety scale

were found to have a virtually identical state anxiety score: mean (SD)

= 11.36 (4.33) compared to those who completed the state anxiety

assessment only: mean (SD) = 11.01 (4.35). The mean (CI95%) difference

was 0.35 (0.89 to -0.18), t = 1.29, df1002, p = 0.2.

Conclusion The completion of a brief dental anxiety questionnaire

before seeing the dentist has a non significant effect on state anxiety.

INTRODUCTION

The assessment of dental anxiety is important for two reasons:

first, to assist the dentist in the management of anxious patients

and secondly to provide evidence-based research into this psy-

chological construct which has been shown to predict dental

avoidance.

1

Various dental anxiety measures have been devel-

oped.

2,3

Previous work by Kent has shown that the completion

of a dental anxiety scale immediately prior to dental treatment

does not influence the patients pain experience.

4

Replication

1*

Professor, Bute Medical School, University of St Andrews, Fife KY16 9TS;

2

Southern

Health and Social Services Board, Armagh BT61 9DR;

3

Professor, Queens University,

Belfast, Dept of Paediatric, Preventive and Public Health Dentistry, School of Dentistry,

RGH, Grosvenor Road, Belfast, BT12 6BP

*Correspondence to: Professor Gerry Humphris

Email: gerry.humphris@st-andrews.ac.uk

Refereed paper

Accepted 28 June 2005

DOI: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4813772

British Dental Journal 2006; 201: 3335

of this study with eight to 14-year-old children supported this

finding.

5

The effect of completing these questions appeared to be

beneficial in reducing self-reported pain experience. The authors

argued that the encouragement of children to consider how anx-

ious they were about certain dental procedures and the prospect

of discomfort enabled them to prepare psychologically for their

dental treatment.

5

A recent survey of dentists with a special

interest in dental anxiety found that the routine use of formal

questionnaires to assess dental anxiety was very limited.

6

This

was disappointing when it was considered that dentists tended

not to recognise dentally anxious patients from their observa-

tions and contact with patients in their surgeries. Reasons for the

poor frequency of utilisation of questionnaires include lack of

time and expertise in their interpretation. It was for this reason

that the brief instrument: the Modified Dental Anxiety Scale

(MDAS) was advocated. The brief nature and ease of interpreta-

tion lent itself to use within general practice. Anecdotal reports

with dental practitioners has suggested another reason; that is,

that some dentists believe that asking patients about their dental

anxiety just before treatment would exacerbate anxiety. Hence

the aim of the study was to test the hypothesis that the com-

pletion of a dental anxiety scale prior to treatment would raise

situational anxiety (also known as state anxiety) in a general

practice patient population.

METHODS

Design of study

A randomised controlled trial used a convenience cluster sam-

pling of dental practices within a prescribed region of Northern

Ireland. A power analysis found that a sample size of approxi-

mately 430 patients in each group would have 90% power to

detect a small effect of a difference in mean of 1 (the difference

between a Group 1 mean of 11 and a Group 2 mean of 12)

assuming that the common standard deviation is 4.5 using a two

group t-test with a 0.05 two-sided significance level. Patients

were randomised by whole sessions (to avoid contamination)

so that all attendees in a single session (defined as the typi-

cal period when the practice was open for a series of patients)

were allocated to either the MDAS or no MDAS condition. The

I N BRI EF

The completion of a short dental anxiety questionnaire by adult patients immediately

before seeing their general dental practitioner does not raise anxiety.

Contrary to some expectations the answering of questions about dental anxiety does not

have a deleterious effect on patients.

Dentists are recommended to use dental anxiety questionnaires routinely as part of their

general assessment of patients.

VERIFIABLE

CPD PAPER

1p33-35.indd 33 3/7/06 11:24:24

RESEARCH

34 BRITISH DENTAL JOURNAL VOLUME 201 NO. 1 JUL 8 2006

researcher on arrival at the practice for the start of the session

opened an opaque sealed envelope in consecutive order from

the stack of envelopes prepared previously through computer

generated assignment for the study. Each envelope contained a

slip inside indicating if the MDAS questionnaire was or was not

to be employed in that session.

Sample

Eighteen practices were selected (32% of all general dental prac-

titioners) within the Southern Health and Social Services Board

(SHSSB) in Northern Ireland. The mean Noble deprivation index,

based upon the postcode of the practice, was 19.9 for partici-

pating dentists which compares closely to the average (20.14)

for the SHSSB area.

7

Approximately 50 eligible patients were

consecutively drawn from each practice within a maximum of

eight sessions per practice. Entry criteria included: aged 16 years

or above, gave written consent and English language spoken.

Visitors to the practice or relatives of patients were excluded.

All refusals were noted.

Measures

The Modified Dental Anxiety Scale (MDAS) consists of five ques-

tions, which assess dental anxiety, and consists of inviting the

respondent to report their dental anxiety prior to a dental visit,

while sitting in the waiting room, waiting to have teeth drilled,

waiting for scaling and waiting for local anaesthetic. This measure

is similar to Corahs Dental Anxiety Scale,

8

but includes an extra

question about a local anaesthetic injection, as well as a simplified

and consistent answering scheme across all questions. There are

five responses to each question which range from not anxious

(scoring 1) to extremely anxious (scoring 5). This gives a pos-

sible range of scores from 5 to 25 with scores of 19 and above as

indicative of dental phobia. Reliability for this measure was also

favourable (internal consistency = 0.89; test-retest = 0.82).

9,10

A short version of Speilbergers State Trait Anxiety Inventory

(STAI-S) was used.

11

The STAI-S is a self-report measure designed

to assess patient state anxiety at the time of completion. It is com-

prised of six statements depicting how the individual may feel,

for example, I am calm. The respondent chooses an answer from

four response categories ranging from not at all to very much.

Scores are summed (with some reverse scoring of individual items)

to give a range from six (not at all anxious) to 24 (very anxious).

The internal consistency for the six item scale is 0.82.

12

The test-

retest for a state anxiety measure tends not to be calculated as it

is typically low, however for the full form of the measure where it

has been quoted (seven articles) has been found to be reasonable

(mean = 0.70).

13

Procedure

Consecutive participants during study sessions were invited to

enter the study at the general dental practices on days where

non-specialist, that is routine service, was provided. Patients in

the MDAS condition completed the dental anxiety questionnaire

followed by the STAIS-S, whereas those in the non MDAS arm of

the study were invited to complete the STAIS-S only. Data were

collected from July to August 2004 by two trained interviewers.

Their role was to consent patients and hand the questionnaire to

the respondent. To eliminate interviewer bias the patients were

not guided through the questionnaire. Research protocol had

been authorised by the Local Research Ethics Committee.

Statistical analysis

Data were analysed by SPSS for Windows v12. Frequencies

and means were calculated on variables where appropriate.

Confidence intervals were calculated.

14

Cross-tabulations of

categorical variables were inspected to test for biased

assignment between the two groups. The t-test was applied

to the STAS-S data to determine difference between the two

study arms. Two tailed tests and an alpha level of 0.05 were

applied throughout.

RESULTS

Of the 1,028 patients who were approached, 24 refused (Fig. 1 ).

Respondents refused due to lack of interest (n = 6), non-possession

of glasses (n = 7), insufficient time (n = 5), or other miscellaneous

reasons (n = 6). The response rate was 98%. Drop-out analysis

revealed no difference between respondents and refusers, with the

exception that the refusers were older (mean (SD) years: refusers =

52(19) vs respondents = 41 (16), t = 3.09, df1, p = 0.002).

Complete data were obtained from 1,004 respondents. Their

mean (SD; range) age was 41 (16; 16 to 90) years; 649 (65%) were

female. Sixty-seven percent (n = 673) claimed to visit the dentist

at least every six months, and 47% (473) expected to receive a

check up rather than dental treatment. The randomisation proce-

dure resulted in approximately the same (p > 0.05) demographic

profile (age, sex), self-reported regularity of dental attendance and

expectations of treatment (Table 1). The mean (SD) level of dental

anxiety as reported by the MDAS (internal consistency = 0.90 for

this sample) was 10.7 (4.3), with 6% scoring 19 or above indicat-

ing high dental anxiety. The STAIS-S scores (internal consistency

= 0.86 for this sample) when pro-rated to the Full-form of 20 items

gave an overall mean (SD) of 37.3 (14.5).

The mean levels of state anxiety using the raw scores from the

six items (ie not pro-rated to the 20 item version) were the same

across the two groups (t = 1.28, df = 1002, p = 0.2; Table 2). The

mean difference (CI95%) was 0.35 (0.89 to -0.18). The analysis was

repeated with only those patients who claimed to visit the dentist

at greater than six month intervals (n = 331). The mean (SD) levels

of state anxiety were 12.3 (4.9) and 11.8 (4.8) for the MDAS and

non MDAS conditions respectively, confirming a non statistical

difference (t = 0.96, df = 329, p = 0.3)

DISCUSSION

This is the first study that has deliberately tested for the immedi-

ate negative effects of asking adult patients about their dental

Patients attending

18 general dental

practices

N = 1028

Patients entered

study

N = 1004

Refusers

N = 24

Reasons:

lack of interest (n=6)

no glasses (n=7)

no time (n=5)

other (n=6)

Randomisation by

session

STAIS-S completed

N = 471

MDAS, STAIS-S

N = 533

Fig. 1 Trial Profile

1p33-35.indd 34 3/7/06 11:10:33

RESEARCH

BRITISH DENTAL JOURNAL VOLUME 201 NO. 1 JUL 8 2006 35

have tended to assess the effect on the patients post-treatment

anxiety or pain perception level. An interesting extension of this

work has been the introduction of a dental anxiety question-

naire into the clinical case management of dental patients.

15

The

patient handing to their dentist their completed dental anxiety

questionnaire appeared to have a significant benefit on state

anxiety levels when leaving the surgery. The study had not how-

ever rated the state anxiety prior to entry into the surgery an

omission which this present investigation has addressed.

The level of participation was high in the study although of

those who refused there was an over-representation of older peo-

ple. The study is limited to patients residing in a region of North-

ern Ireland. Nevertheless, the study sample compared well to other

groups, as demonstrated by the mean dental anxiety level (10.7)

being comparable to the norm for general practice UK attendees

(mean = 10.8).

9

Therefore the recommendation of this brief report is that formal

assessment of dental anxiety prior to treatment can be used with

confidence as an adjunct to the treatment of adult patients attend-

ing general practice.

We would like to thank Aoibheann McGahan and Lisa Hall for their assistance

with the data collection and data entry. We would also like to acknowledge the

dental practitioners and their patients who participated in the study. Work

conducted within the geographical boundaries of the SHSSB, Northern Ireland.

1. Kent G. Dental phobias. In Davey G (Ed) Phobias a handbook of theory, research and

treatment. London: John Wiley and Sons Ltd, 1997.

2. Newton J, Buck D. Anxiety and pain measures in dentistry: a guide to their quality

and application. J Amer Dent Assoc 2000; 131: 1449-1457.

3. Schuurs A, Hoogstraten J. Appraisal of dental anxiety and fear questionnaires: a

review. Comm Dent Oral Epidemiol 1993; 21: 329-339.

4. Kent G. Effect of pre-appointment inquiries on dental patients post-appointment

ratings of pain. Br J Med Psych 1986; 59: 97-99.

5. Carlsen A, Humphris G M, Lee G T R, Birch R H. The effect of pre-treatment enquiries

on child dental patients post-treatment ratings of pain and anxiety. Psychology and

Health 1993; 8: 165-174.

6. Dailey Y, Humphris G, Lennon M. The use of dental anxiety questionnaires: a survey

of a group of UK dental practitioners. Br Dent J 2001; 190: 450-453.

7. Beatty R. Northern Ireland Multiple Deprivation Measure 2001 A users guide.

NISRA Occasional Paper. Belfast: Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency,

2004.

8. Corah N L. Development of a dental anxiety scale. J Dent Res 1969; 48: 596.

9. Humphris G M, Morrison T, Lindsay S J E. The Modified Dental Anxiety Scale: UK

norms and evidence for validity. Comm Dent Health 1995; 12: 143-150.

10. Humphris G M, Freeman R, Campbell J et al. Further evidence for the reliability and

validity of the Modified Dental Anxiety Scale. Int Dent J 2000; 50: 376-380.

11. Marteau T M, Bekker H. The development of a six-item short-form of the stale of scale of

the Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI). Br J Clin Psych 1992; 31: 301-306.

12. Speilberger C. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety STAI (Form Y). Palo Alto, CA:

Consulting Psychologists Press, 1983.

13. Barnes L, Harp D, Jung W. Reliability generalization of scores on the Speilberger

State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. Educ Psych Meas 2002; 62: 603-618.

14. Gardner M, Altman D. Statistics with confidence: confidence intervals and statistical

guidelines. London: British Medical Journal, 1989.

15. Dailey Y, Humphris G, Lennon M. Reducing patients state anxiety in general dental

practice: a randomized controlled trial. J Dent Res 2002; 81: 319-322.

anxiety at the time when they will be entering the dental surgery

for their appointment. This brief study has confirmed that the

adoption of a self-reported brief questionnaire to assess dental

anxiety immediately prior to entering the dental surgery did not

significantly increase the patients anxiety. When the sample was

restricted to those who reported less regular attendance the same

result was found. As patients who are irregular attendees report

higher levels of dental anxiety, this would suggest that the find-

ing of this study may be robust across a range of dental anxiety

levels. The result supports previous work that the introduction of

a brief self-report tool to assess dental anxiety has no measur-

able short term deleterious effects on patients.

4,5

Previous studies

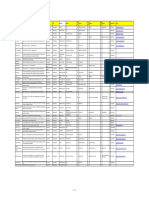

Table 1 Age, gender, self-reported regularity of dental attendance and

expected treatment across group assignment

No Dental anxiety

Questionnaire Group

Dental anxiety

Questionnaire Group

Age: Mean (SD) 41.3 (15.4) 41.5 (16.3)

N (%) N (%)

Gender

Male 159 (34) 196 (37)

Female 312 (66) 337 (63)

Self-reported regularity

of attendance

Every 6 months or more 312 (66) 361 (68)

Less than every 6 months 159 (34) 152 (32)

Expected treatment

Check up 209 (44) 262 (49)

Treatment 264 (56) 269 (51)

Table 2 Situational anxiety (STAIS-S) means, standard deviations and

confidence intervals for the two study groups

No Dental anxiety

Questionnaire Group

Dental anxiety

Questionnaire Group t p

Mean 11.01 11.36 1.29 0.20

SD 4.35 4.33

(95%CI) 10.62, 11.40 10.99, 11.73

1p33-35.indd 35 3/7/06 11:22:40

Você também pode gostar

- G - TMD-pedo MNGMT PDFDocumento6 páginasG - TMD-pedo MNGMT PDFjinny1_0Ainda não há avaliações

- GoldsDocumento11 páginasGoldsjinny1_0Ainda não há avaliações

- Pulp Therapy-Guideline AapdDocumento8 páginasPulp Therapy-Guideline Aapdjinny1_0Ainda não há avaliações

- Groper's ApplianceDocumento4 páginasGroper's Appliancejinny1_0Ainda não há avaliações

- Oral Mucosal Lesions Associated With The Wearing of Removable DenturesDocumento17 páginasOral Mucosal Lesions Associated With The Wearing of Removable DenturesnybabyAinda não há avaliações

- A Systematic Review of Impression Technique For ConventionalDocumento7 páginasA Systematic Review of Impression Technique For ConventionalAmar BhochhibhoyaAinda não há avaliações

- GicDocumento5 páginasGicmrnitin82Ainda não há avaliações

- E Adaproceedings-Child AbuseDocumento64 páginasE Adaproceedings-Child Abusejinny1_0Ainda não há avaliações

- AAPD Policy On - FluorideUseDocumento2 páginasAAPD Policy On - FluorideUsejinny1_0Ainda não há avaliações

- Mucosa in Complete DenturesDocumento4 páginasMucosa in Complete Denturesspu123Ainda não há avaliações

- EEL 7 SpeakingDocumento20 páginasEEL 7 SpeakingSathish KumarAinda não há avaliações

- Die HardnerDocumento4 páginasDie Hardnerjinny1_0Ainda não há avaliações

- Assertmodule 1Documento9 páginasAssertmodule 1Olivera Mihajlovic TzanetouAinda não há avaliações

- Article-PDF-Amit Kalra Manish Kinra Rafey Fahim-25Documento5 páginasArticle-PDF-Amit Kalra Manish Kinra Rafey Fahim-25jinny1_0Ainda não há avaliações

- Spacer Design Jips 2005 PDFDocumento5 páginasSpacer Design Jips 2005 PDFjinny1_0Ainda não há avaliações

- Afpam47 103v1Documento593 páginasAfpam47 103v1warmil100% (1)

- DisinfectionDocumento5 páginasDisinfectionjinny1_0Ainda não há avaliações

- KurthDocumento18 páginasKurthjinny1_0Ainda não há avaliações

- Patient-Assessed Security Changes When Replacing Mandibular Complete DenturesDocumento7 páginasPatient-Assessed Security Changes When Replacing Mandibular Complete Denturesjinny1_0Ainda não há avaliações

- 7Documento8 páginas7jinny1_0Ainda não há avaliações

- Implant AngulationDocumento17 páginasImplant Angulationjinny1_0Ainda não há avaliações

- ResinDocumento8 páginasResinjinny1_0Ainda não há avaliações

- Denture Base Resin CytotoxityDocumento7 páginasDenture Base Resin Cytotoxityjinny1_0Ainda não há avaliações

- Avg Vs NormalDocumento1 páginaAvg Vs Normaljinny1_0Ainda não há avaliações

- AlginateDocumento5 páginasAlginatejinny1_0Ainda não há avaliações

- Stress Fatigue PrinciplesDocumento12 páginasStress Fatigue Principlesjinny1_0Ainda não há avaliações

- 3Documento7 páginas3jinny1_0Ainda não há avaliações

- 11Documento7 páginas11jinny1_0Ainda não há avaliações

- Long-Term Cytotoxicity of Dental Casting AlloysDocumento8 páginasLong-Term Cytotoxicity of Dental Casting Alloysjinny1_0Ainda não há avaliações

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (399)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5794)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2219)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (344)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (265)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (119)

- OXYGEN INHALATION (Demo)Documento16 páginasOXYGEN INHALATION (Demo)Rinchin ChhotenAinda não há avaliações

- What Vaccines Do BC Adults NeedDocumento2 páginasWhat Vaccines Do BC Adults NeedCatalina VisanAinda não há avaliações

- 15-10-2019, Mr. Jamal, 50 Yo, V.Laceratum Cruris Dextra + Skin Loss + Fraktur Os Fibula, Dr. Moh. Rizal Alizi, M.Kes, Sp. OT-1Documento15 páginas15-10-2019, Mr. Jamal, 50 Yo, V.Laceratum Cruris Dextra + Skin Loss + Fraktur Os Fibula, Dr. Moh. Rizal Alizi, M.Kes, Sp. OT-1anon_893244902Ainda não há avaliações

- Bishop Score of PregnancyDocumento13 páginasBishop Score of PregnancydrvijeypsgAinda não há avaliações

- Name Clinic/Hosp/Med Name &address Area City Speciality SEWA01 Disc 01 SEWA02 DIS C02 SEWA03 Disc 03 SEWA04 DIS C04 Contact No. EmailDocumento8 páginasName Clinic/Hosp/Med Name &address Area City Speciality SEWA01 Disc 01 SEWA02 DIS C02 SEWA03 Disc 03 SEWA04 DIS C04 Contact No. EmailshrutiAinda não há avaliações

- Functions of Parotid GlandDocumento32 páginasFunctions of Parotid GlandAsline JesicaAinda não há avaliações

- Contoh Soal UKNiDocumento4 páginasContoh Soal UKNiNurhaya NurdinAinda não há avaliações

- Morning Report Case Presentation: APRIL 1, 2019Documento14 páginasMorning Report Case Presentation: APRIL 1, 2019Emily EresumaAinda não há avaliações

- Eric Wahlberg, Jerry Goldstone - Emergency Vascular Surgery - A Practical Guide-Springer-Verlag (2017)Documento216 páginasEric Wahlberg, Jerry Goldstone - Emergency Vascular Surgery - A Practical Guide-Springer-Verlag (2017)Conțiu Maria Larisa100% (4)

- Difficulties in Breastfeeding Easy Solution by OkeDocumento6 páginasDifficulties in Breastfeeding Easy Solution by OkewladjaAinda não há avaliações

- ACLM Benefits of Plant Based Nutrition SummaryDocumento1 páginaACLM Benefits of Plant Based Nutrition SummaryJitendra kumarAinda não há avaliações

- Nasogastric Tube (NGT)Documento31 páginasNasogastric Tube (NGT)annyeong_123Ainda não há avaliações

- Ap2 Safe ManipulationDocumento5 páginasAp2 Safe ManipulationDarthVader975Ainda não há avaliações

- Infectious Disease Project-NikkiDocumento13 páginasInfectious Disease Project-Nikkiuglyghost0514Ainda não há avaliações

- RCM: Revenue Cycle Management in HealthcareDocumento15 páginasRCM: Revenue Cycle Management in Healthcaresenthil kumar100% (5)

- Treating Ectopic Pregnancy With MethotrexateDocumento4 páginasTreating Ectopic Pregnancy With MethotrexateOx CherryAinda não há avaliações

- Pe 2 Week 6Documento2 páginasPe 2 Week 6Nicoleigh ArnejoAinda não há avaliações

- AFOMP Newsletter January 2022 Vol14 No.1 UpdatedDocumento48 páginasAFOMP Newsletter January 2022 Vol14 No.1 UpdatedparvezAinda não há avaliações

- Post Activity Report (Or Terminal Report)Documento14 páginasPost Activity Report (Or Terminal Report)luningning0007Ainda não há avaliações

- Clinical Dental Hygiene II 2021-2022 Course CatalogDocumento2 páginasClinical Dental Hygiene II 2021-2022 Course Catalogapi-599847268Ainda não há avaliações

- Revised WHO PneumoniaDocumento2 páginasRevised WHO Pneumoniaهناء همة العلياAinda não há avaliações

- Consent Form for SchoolDocumento4 páginasConsent Form for SchoolSwadesh GiriAinda não há avaliações

- Newborn Care: A Newborn Baby or Animal Is One That Has Just Been BornDocumento26 páginasNewborn Care: A Newborn Baby or Animal Is One That Has Just Been BornJenny-Vi Tegelan LandayanAinda não há avaliações

- Hunger and MulnutritionDocumento12 páginasHunger and MulnutritionKrishna Kant KumarAinda não há avaliações

- Combustio: DR - Dian SyahputraDocumento35 páginasCombustio: DR - Dian SyahputraYulliza Kurniawaty LAinda não há avaliações

- Shwachman-Diamond Syndrome - GeneReviews® - NCBI BookshelfDocumento23 páginasShwachman-Diamond Syndrome - GeneReviews® - NCBI Bookshelfgrlr0072467Ainda não há avaliações

- Clinical Profile and Outcome of Myasthenic CrisisDocumento13 páginasClinical Profile and Outcome of Myasthenic CrisissyahriniAinda não há avaliações

- CASE STUDY of HCDocumento3 páginasCASE STUDY of HCAziil LiizaAinda não há avaliações

- This Study Resource Was: Date of CompletionDocumento6 páginasThis Study Resource Was: Date of CompletionNicole AngelAinda não há avaliações

- Donning A Sterile Gown and GlovesDocumento3 páginasDonning A Sterile Gown and GlovesVanny Vien JuanilloAinda não há avaliações