Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Ronquillo Vs CA

Enviado por

abethzkyyyyDescrição original:

Título original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Ronquillo Vs CA

Enviado por

abethzkyyyyDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

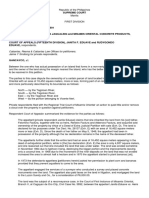

Republic of the Philippines

SUPREME COURT

Manila

SECOND DIVISION

G.R. No. L-43346 March 20, 1991

MARIO C. RONQUILLO, petitioner

vs.

THE COURT OF APPEALS, DIRECTOR OF LANDS, DEVELOPMENT

BANK OF THE PHILIPPINES, ROSENDO DEL ROSARIO, AMPARO DEL

ROSARIO and FLORENCIA DEL ROSARIO, respondents.*

Angara, Abello, Concepcion, Regala & Cruz for petitioner.

REGALADO, J .:p

This petition seeks the review of the decision

1

rendered by respondent Court of

Appeals on September 25, 1975 in CA-G.R. No. 32479-R, entitled "Rosendo del

Rosario, et al., Plaintiffs-Appellees, versus Mario Ronquillo, Defendant-Appellant,"

affirming in toto the judgment of the trial court, and its amendatory resolution

2

dated

January 28, 1976 the dispositive portion of which reads:

IN VIEW OF THE FOREGOING, the decision of this Court dated

September 25, 1975 is hereby amended in the sense that the first

part of the appealed decision is set aside, except the last portion

"declaring the plaintiffs to be the rightful owners of the dried-up

portion of Estero Calubcub which is abutting plaintiffs' property,"

which we affirm, without pronouncement as to costs.

SO ORDERED.

The following facts are culled from the decision of the Court of Appeals:

It appears that plaintiff Rosendo del Rosario was a registered

owner of a parcel of land known as Lot 34, Block 9, Sulucan

Subdivision, situated at Sampaloc, Manila and covered by Transfer

Certificate of Title No. 34797 of the Registry of Deeds of Manila

(Exhibit "A"). The other plaintiffs Florencia and Amparo del

Rosario were daughters of said Rosendo del Rosario. Adjoining

said lot is a dried-up portion of the old Estero Calubcub occupied

by the defendant since 1945 which is the subject matter of the

present action.

Plaintiffs claim that long before the year 1930, when T.C.T. No.

34797 over Lot No. 34 was issued in the name of Rosendo del

Rosario, the latter had been in possession of said lot including the

adjoining dried-up portion of the old Estero Calubcub having

bought the same from Arsenio Arzaga. Sometime in 1935, said

titled lot was occupied by Isabel Roldan with the tolerance and

consent of the plaintiff on condition that the former will make

improvements on the adjoining dried-up portion of the Estero

Calubcub. In the early part of 1945 defendant occupied the eastern

portion of said titled lot as well as the dried-up portion of the old

Estero Calubcub which abuts plaintiffs' titled lot. After a relocation

survey of the land in question sometime in 1960, plaintiffs learned

that defendant was occupying a portion of their land and thus

demanded defendant to vacate said land when the latter refused to

pay the reasonable rent for its occupancy. However, despite said

demand defendant refused to vacate.

Defendant on the other hand claims that sometime before 1945 he

was living with his sister who was then residing or renting

plaintiffs' titled lot. In 1945 he built his house on the disputed

dried-up portion of the Estero Calubcub with a small portion

thereof on the titled lot of plaintiffs. Later in 1961, said house was

destroyed by a fire which prompted him to rebuild the same.

However, this time it was built only on the called up portion of the

old Estero Calubcub without touching any part of plaintiffs titled

land. He further claims that said dried-up portion is a land of

public domain.

3

Private respondents Rosendo, Amparo and Florencia, all surnamed del Rosario (Del

Rosarios), lodged a complaint with the Court of First Instance of Manila praying,

among others, that they be declared the rightful owners of the dried-up portion of

Estero Calubcub. Petitioner Mario Ronquillo (Ronquillo) filed a motion to dismiss

the complaint on the ground that the trial court had no jurisdiction over the case since

the dried-up portion of Estero Calubcub is public land and, thus, subject to the

disposition of the Director of Lands. The Del Rosarios opposed the motion arguing

that since they are claiming title to the dried-up portion of Estero Calubcub as

riparian owners, the trial court has jurisdiction. The resolution of the motion to

dismiss was deferred until after trial on the merits.

Before trial, the parties submitted the following stipulation of facts:

1. That the plaintiffs are the registered owners of Lot 34, Block 9,

Sulucan Subdivision covered by Transfer Certificate of Title No.

34797;

2. That said property of the plaintiffs abuts and is adjacent to the

dried-up river bed of Estero Calubcub Sampaloc, Manila;

3. That defendant Mario Ronquillo has no property around the

premises in question and is only claiming the dried-up portion of

the old Estero Calubcub, whereon before October 23, 1961, the

larger portion of his house was constructed;

4. That before October 23, 1961, a portion of defendant's house

stands (sic) on the above-mentioned lot belonging to the plaintiffs;

5. That the plaintiffs and defendant have both filed with the Bureau

of Lands miscellaneous sales application for the purchase of the

abandoned river bed known as Estero Calubcub and their sales

applications, dated August 5, 1958 and October 13, 1959,

respectively, are still pending action before the Bureau of Lands;

6. That the parties hereby reserve their right to prove such facts as

are necessary to support their case but not covered by this

stipulation of facts.

4

On December 26, 1962, the trial court rendered judgment the decretal portion of

which provides:

WHEREFORE, judgment is hereby rendered ordering the

defendant to deliver to the plaintiffs the portion of the land covered

by Transfer Certificate of title No. 34797 which is occupied by him

and to pay for the use and occupation of said portion of land at the

rate of P 5.00 a month from the date of the filing of the complaint

until such time as he surrenders the same to the plaintiffs and

declaring plaintiffs to be the owners of the dried-up portion of

estero Calubcub which is abutting plaintiffs' property.

With costs to the defendant.

SO ORDERED.

5

On appeal, respondent court, in affirming the aforequoted decision of the trial court,

declared that since Estero Calubcub had already dried-up way back in 1930 due to

the natural change in the course of the waters, under Article 370 of the old Civil

Code which it considers applicable to the present case, the abandoned river bed

belongs to the Del Rosarios as riparian owners. Consequently, respondent court

opines, the dried-up river bed is private land and does not form part of the land of the

public domain. It stated further that "(e)ven assuming for the sake of argument that

said estero did not change its course but merely dried up or disappeared, said dried-

up estero would still belong to the riparian owner," citing its ruling in the case

of Pinzon vs. Rama.

6

Upon motion of Ronquillo, respondent court modified its decision by setting aside

the first portion of the trial court's decision ordering Ronquillo to surrender to the

Del Rosarios that portion of land covered by Transfer Certificate of Title No. 34797

occupied by the former, based on the former's representation that he had already

vacated the same prior to the commencement of this case. However, respondent

court upheld its declaration that the Del Rosarios are the rightful owners of the dried-

up river bed. Hence, this petition.

On May 17, 1976, this Court issued a resolution

7

requiring the Solicitor General to

comment on the petition in behalf of the Director of Lands as an indispensable party

in representation of the Republic of the Philippines, and who, not having been

impleaded, was subsequently considered impleaded as such in our resolution of

September 10, 1976.

8

In his Motion to Admit Comment,

9

the Solicitor General

manifested that pursuant to a request made by this office with the Bureau of Lands to

conduct an investigation, the Chief of the Legal Division of the Bureau sent a

communication informing him that the records of his office "do not show that Mario

Ronquillo, Rosendo del Rosario, Amparo del Rosario or Florencia del Rosario has

filed any public land application covering parcels of land situated at Estero Calubcub

Manila as verified by our Records Division.

The position taken by the Director of Lands in his Comment

10

filed on September 3,

1978, which was reiterated in the Reply dated May 4, 1989 and again in the

Comment dated August 17, 1989, explicates:

5. We do not see our way clear to subscribe to the ruling of the

Honorable Court of Appeals on this point for Article 370 of the

Old Civil Code, insofar as ownership of abandoned river beds by

the owners of riparian lands are concerned, speaks only of a

situation where such river beds were abandoned because of a

natural change in the course of the waters. Conversely, we submit

that if the abandonment was for some cause other than the natural

change in the course of the waters, Article 370 is not applicable

and the abandoned bed does not lose its character as a property of

public dominion not susceptible to private ownership in

accordance with Article 502 (No. 1) of the New Civil Code. In the

present case, the drying up of the bed, as contended by the

petitioner, is clearly caused by human activity and undeniably not

because of the natural change of the course of the waters

(Emphasis in the original text).

In his Comment

11

dated August 17, 1989, the Director of Lands further adds:

8. Petitioner herein and the private respondents, the del Rosarios,

claim to have pending sales application(s) over the portion of the

dried up Estero Calubcub, as stated in pages 4-5, of the Amended

Petition.

9. However, as stated in the Reply dated May 4, 1989 of the

Director of Lands, all sales application(s) have been rejected by

that office because of the objection interposed by the Manila City

Engineer's Office that they need the dried portion of the estero for

drainage purposes.

10. Furthermore, petitioner and private respondents, the del

Rosarios having filed said sales application(s) are now estopped

from claiming title to the Estero Calubcub (by possession for

petitioner and by accretion for respondents del Rosarios) because

for (sic) they have acknowledged that they do not own the land and

that the same is a public land under the administration of the

Bureau of Lands (Director of Lands vs. Santiago, 160 SCRA 186,

194).

In a letter dated June 29, 1979

12

Florencia del Rosario manifested to this Court that

Rosendo, Amparo and Casiano del Rosario have all died, and that she is the only one

still alive among the private respondents in this case.

In a resolution dated January 20, 1988,

13

the Court required petitioner Ronquillo to

implead one Benjamin Diaz pursuant to the former's

manifestation

14

that the land adjacent to the dried up river bed has already been sold

to the latter, and the Solicitor General was also required to inquire into the status of

the investigation being conducted by the Bureau of Lands. In compliance therewith,

the Solicitor General presented a letter from the Director of Lands to the effect that

neither of the parties involved in the present case has filed any public land

application.

15

On April 3, 1989, petitioner filed an Amended Petition for Certiorari,

16

this time

impleading the Development Bank of the Philippines (DBP) which subsequently

bought the property adjacent to the dried-up river bed from Benjamin Diaz. In its

resolution dated January 10, 1990,

17

the Court ordered that DBP be impleaded as a

party respondent.

In a Comment

18

filed on May 9, 1990, DBP averred that "[c]onsidering the fact that

the petitioner in this case claims/asserts no right over the property sold to Diaz/DBP

by the del Rosarios; and considering, on the contrary, that Diaz and DBP

claims/asserts (sic) no right (direct or indirect) over the property being claimed by

Ronquillo (the dried-up portion of Estero Calubcub), it follows, therefore, that the

petitioner Ronquillo has no cause of action against Diaz or DBP. A fortiorifrom the

viewpoint of the classical definition of a cause of action, there is no legal

justification to implead DBP as one of the respondents in this petition." DBP

thereafter prayed that it be dropped in the case as party respondent.

On September 13, 1990, respondent DBP filed a Manifestation/Compliance

19

stating

that DBP's interest over Transfer Certificate of Title No. 139215 issued in its name

(formerly Transfer Certificate of Title No. 34797 of the Del Rosarios and Transfer

Certificate of Title No. 135170 of Benjamin Diaz) has been transferred to Spouses

Victoriano and Pacita A. Tolentino pursuant to a Deed of Sale dated September 11,

1990.

Petitioner Ronquillo avers that respondent Court of Appeals committed an error of

law and gross abuse of discretion, acted arbitrarily and denied petitioner due process

of law (a) when it declared private respondents Del Rosarios the rightful owners of

the dried-up portion of Estero Calubcub by unduly relying upon decisional law in the

case of Pinzon vs. Rama, ante, which case was decided entirely on a set of facts

different from that obtaining in this case; and (b) when it ignored the undisputed

facts in the present case and declared the dried-up portion of Estero Calubcub as a

private property.

The main issue posed for resolution in this petition is whether the dried-up portion of

Estero Calubcub being claimed by herein petitioner was caused by a natural change

in the course of the waters; and, corollary thereto, is the issue of the applicability of

Article 370 of the old Civil Code.

Respondent court, in affirming the findings of the trial court that there was a natural

change in the course of Estero Calubcub declared that:

The defendant claims that Article 370 of the old Civil Code is not

applicable to the instant case because said Estero Calubcub did not

actually change its course but simply dried up, hence, the land in

dispute is a land of public domain and subject to the disposition of

the Director of Land(s). The contention of defendant is without

merit. As mentioned earlier, said estero as shown by the relocation

plan (Exhibit "D") did not disappear but merely changed its course

by a more southeasternly (sic) direction. As such, "the abandoned

river bed belongs to the plaintiffs-appellees and said land is private

and not public in nature. Hence, further, it is not subject to a

Homestead Application by the appellant." (Fabian vs. Paculan CA-

G.R. Nos. 21062-63-64-R, Jan. 25 1962). Even assuming for the

sake of argument that said estero did not change its course but

merely dried up or disappeared, said dried-up estero would still

belong to the riparian owner as held by this Court in the case

of Pinzon vs. Rama (CA-G.R. No. 8389, Jan. 8, 1943; 2 O.G.

307).

20

Elementary is the rule that the jurisdiction of the Supreme Court in cases brought to

it from the Court of Appeals in a petition for certiorari under Rule 45 of the Rules of

Court is limited to the review of errors of law, and that said appellate court's finding

of fact is conclusive upon this Court. However, there are certain exceptions, such as

(1) when the conclusion is a finding grounded entirely on speculation, surmises or

conjectures; (2) when the inference made is manifestly absurd, mistaken or

impossible; (3) when there is grave abuse of discretion in the appreciation of facts;

(4) when the judgment is premised on a misapprehension of facts; (5) when the

findings of fact are conflicting; and (6) when the Court of Appeals in making its

findings went beyond the issues of the case and the same is contrary to the

admissions of both appellant and

appellee.

21

A careful perusal of the evidence presented by both parties in the case at bar will

reveal that the change in the course of Estero Calubcub was caused, not by natural

forces, but due to the dumping of garbage therein by the people of the surrounding

neighborhood. Under the circumstances, a review of the findings of fact of

respondent court thus becomes imperative.

Private respondent Florencia del Rosario, in her testimony, made a categorical

statement which in effect admitted that Estero Calubcub changed its course because

of the garbage dumped therein, by the inhabitants of the locality, thus:

Q When more or less what (sic) the estero fully dried up?

A By 1960 it is (sic) already dried up except for a little rain that

accumulates on the lot when it rains.

Q How or why did the Estero Calubcub dried (sic) up?

A It has been the dumping place of the whole neighborhood. There

is no street, they dumped all the garbage there. It is the dumping

place of the whole community, sir.

22

In addition, the relocation plan (Exhibit "D") which also formed the basis of

respondent court's ruling, merely reflects the change in the course of Estero

Calubcub but it is not clear therefrom as to what actually brought about such change.

There is nothing in the testimony of lone witness Florencia del Rosario nor in said

relocation plan which would indicate that the change in the course of the estero was

due to the ebb and flow of the waters. On the contrary, the aforequoted testimony of

the witness belies such fact, while the relocation plan is absolutely silent on the

matter. The inescapable conclusion is that the dried-up portion of Estero Calubcub

was occasioned, not by a natural change in the course of the waters, but through the

active intervention of man.

The foregoing facts and circumstances remove the instant case from the applicability

of Article 370 of the old Civil Code which provides:

Art. 370. The beds of rivers, which are abandoned because of a

natural change in the course of the waters, belong to the owners of

the riparian lands throughout the respective length of each. If the

abandoned bed divided tenements belonging to different owners

the new dividing line shall be equidistant from one and the other.

The law is clear and unambiguous. It leaves no room for interpretation. Article 370

applies only if there is a natural change in the course of the waters. The rules on

alluvion do not apply to man-made or artificial accretions

23

nor to accretions to

lands that adjoin canals or esteros or artificial drainage systems.

24

Considering our

earlier finding that the dried-up portion of Estero Calubcub was actually caused by

the active intervention of man, it follows that Article 370 does not apply to the case

at bar and, hence, the Del Rosarios cannot be entitled thereto supposedly as riparian

owners.

The dried-up portion of Estero Calubcub should thus be considered as forming part

of the land of the public domain which cannot be subject to acquisition by private

ownership. That such is the case is made more evident in the letter, dated April 28,

1989, of the Chief, Legal Division of the Bureau of Lands

25

as reported in the Reply

of respondent Director of Lands stating that "the alleged application filed by

Ronquillo no longer exists in its records as it must have already been disposed of as a

rejected application for the reason that other applications "covering Estero Calubcub

Sampaloc, Manila for areas other than that contested in the instant case, were all

rejected by our office because of the objection interposed by the City Engineer's

office that they need the same land for drainage purposes". Consequently, since the

land is to be used for drainage purposes the same cannot be the subject of a

miscellaneous sales application.

Lastly, the fact that petitioner and herein private respondents filed their sales

applications with the Bureau of Lands covering the subject dried-up portion of

Estero Calubcub cannot but be deemed as outright admissions by them that the same

is public land. They are now estopped from claiming otherwise.

WHEREFORE, the decision appealed from, the remaining effective portion of which

declares private respondents Del Rosarios as riparian owners of the dried-up portion

of Estero Calubcub is hereby REVERSED and SET ASIDE.

SO ORDERED.

Republic of the Philippines

SUPREME COURT

Manila

EN BANC

G.R. No. L-31163 November 6, 1929

URBANO SANTOS, plaintiff-appellee,

vs.

JOSE C. BERNABE, ET AL., defendants.

PABLO TIONGSON and THE PROVINCIAL SHERIFF OF

BULACAN, appellants.

Arcadio Ejercito and Guevara, Francisco and Recto for appellants.

Eusebio Orense And Nicolas Belmonte for appellee.

VILLA-REAL, J .:

This appeal was taken by the defendants Pablo Tiongson and the Provincial Sheriff

of Bulacan from the judgment of the Court of First of said province, wherein said

defendant Pablo Tiongson was ordered to pay the plaintiff Urbano Santos the value

of 778 cavans and 38 kilos of palay, at the rate of P3 per cavan, without special

pronouncement as to costs.

In support of their appeal, the appellants assign the following alleged errors

committed by the lower court in its judgment, to wit:

1. The court erred in holding that it has been proved that in the cavans of

palay attached by the herein defendant Pablo Tiongson from the defendant

Jose C. Bernabe were included those claimed by the plaintiff in this cause.

2. The court erred in ordering the defendant Pablo Tiongson to pay the

plaintiff the value of 778 cavans and 38 kilos of palay, the refund of which

is claimed by said plaintiff.

3. The court erred in denying the defendants' motion for a new

trial.1awphil.net

The following facts were conclusively proved at the trial:

On March 20, 1928, there were deposited in Jose C. Bernabe's warehouse by the

plaintiff Urbano Santos 778 cavans and 38 kilos of palay and by Pablo Tiongson

1,026 cavans and 9 kilos of the same grain.

On said date, March 20, 1928, Pablo Tiongson filed with the Court of First Instance

of Bulacan a complaint against Jose C. Bernabe, to recover from the latter the 1,026

cavans and 9 kilos of palay deposited in the defendant's warehouse. At the same

time, the application of Pablo Tiongson for a writ of attachment was granted, and the

attachable property of Jose C. Bernabe, including 924 cavans and 31 1/2 kilos of

palay found by the sheriff in his warehouse, were attached, sold at public auction,

and the proceeds thereof delivered to said defendant Pablo Tiongson, who obtained

judgment in said case.

The herein plaintiff, Urbano Santos, intervened in the attachment of the palay, but

upon Pablo Tiongson's filing the proper bond, the sheriff proceeded with the

attachment, giving rise to the present complaint.

It does not appear that the sacks of palay of Urbano Santos and those of Pablo

Tiongson, deposited in Jose C. Bernabe's warehouse, bore any marks or signs, nor

were they separated one from the other.

The plaintiff-appellee Urbano Santos contends that Pablo Tiongson cannot claim the

924 cavans and 31 kilos of palay attached by the defendant sheriff as part of those

deposited by him in Jose C. Bernabe's warehouse, because, in asking for the

attachment thereof, he impliedly acknowledged that the same belonged to Jose C.

Bernabe and not to him.

In the complaint filed by Pablo Tiongson against Jose C. Bernabe, civil case No.

3665 of the Court of First Instance of Bulacan, it is alleged that said plaintiff

deposited in the defendant's warehouse 1,026 cavans and 9 kilos of palay, the return

of which, or the value thereof, at the rate of P3 per cavan was claimed therein. Upon

filing said complaint, the plaintiff applied for a preliminary writ of attachment of the

defendant's property, which was accordingly issued, and the defendant's property,

including the 924 cavans and 31 kilos of palay found by the sheriff in his

warehouse, were attached.

It will be seen that the action brought by Pablo Tiongson against Jose C. Bernabe is

that provided in section 262 of the Code of Civil Procedure for the delivery of

personal property. Although it is true that the plaintiff and his attorney did not follow

strictly the procedure provided in said section for claiming the delivery of said

personal property nevertheless, the procedure followed by him may be construed as

equivalent thereto, considering the provisions of section 2 of the Code of Civil

Procedure of the effect that "the provisions of this Code, and the proceedings under

it, shall be liberally construed, in order to promote its object and assist the parties in

obtaining speedy justice."

Liberally construing, therefore, the above cited provisions of section 262 of the Code

of Civil Procedure, the writ of attachment applied for by Pablo Tiongson against the

property of Jose C. Bernabe may be construed as a claim for the delivery of the sacks

of palay deposited by the former with the latter.

The 778 cavans and 38 kilos of palay belonging to the plaintiff Urbano Santos,

having been mixed with the 1,026 cavans and 9 kilos of palay belonging to the

defendant Pablo Tiongson in Jose C. Bernabe's warehouse; the sheriff having found

only 924 cavans and 31 1/2 kilos of palay in said warehouse at the time of the

attachment thereof; and there being no means of separating form said 924 cavans and

31 1/2 of palay belonging to Urbano Santos and those belonging to Pablo Tiongson,

the following rule prescribed in article 381 of the Civil Code for cases of this nature,

is applicable:

Art. 381. If, by the will of their owners, two things of identical or dissimilar

nature are mixed, or if the mixture occurs accidentally, if in the latter case

the things cannot be separated without injury, each owner shall acquire a

right in the mixture proportionate to the part belonging to him, according to

the value of the things mixed or commingled.

The number of kilos in a cavan not having been determined, we will take the

proportion only of the 924 cavans of palay which were attached and sold, thereby

giving Urbano Santos, who deposited 778 cavans, 398.49 thereof, and Pablo

Tiongson, who deposited 1,026 cavans, 525.51, or the value thereof at the rate of P3

per cavan.

Wherefore, the judgment appealed from is hereby modified, and Pablo Tiongson is

hereby ordered to pay the plaintiff Urbano Santos the value of 398.49 cavans of

palay at the rate of P3 a cavan, without special pronouncement as to costs. So

ordered.

Você também pode gostar

- G.R. No. L-43346 March 20, 1991Documento8 páginasG.R. No. L-43346 March 20, 1991Kael de la CruzAinda não há avaliações

- Property-Cases 6Documento32 páginasProperty-Cases 6Rizza MoradaAinda não há avaliações

- Ron QuilloDocumento6 páginasRon QuilloLorielyn BrionesAinda não há avaliações

- Ronquillo DigestDocumento3 páginasRonquillo DigestMama MiaAinda não há avaliações

- Meneses Vs CADocumento7 páginasMeneses Vs CAPaolo Antonio EscalonaAinda não há avaliações

- Jagualing V CA 194 Scra 607 (1991)Documento5 páginasJagualing V CA 194 Scra 607 (1991)Breth1979Ainda não há avaliações

- Sta. Monica Industrial and Development Corporation vs. Court of Appeals (189 SCRA 792)Documento8 páginasSta. Monica Industrial and Development Corporation vs. Court of Appeals (189 SCRA 792)dondzAinda não há avaliações

- Vargas and Vargas V CA L 35666Documento3 páginasVargas and Vargas V CA L 35666gongsilogAinda não há avaliações

- Fierro v. Seguiran G.R. No. 152141Documento3 páginasFierro v. Seguiran G.R. No. 152141rodel talabaAinda não há avaliações

- Palomo v. CA GR No. 95608, Jan. 21, 1997Documento5 páginasPalomo v. CA GR No. 95608, Jan. 21, 1997Jawa B LntngAinda não há avaliações

- G.R. No. 94283Documento5 páginasG.R. No. 94283orionsrulerAinda não há avaliações

- Maximo Jagualing Et Al Vs Court of Appeals Et AlDocumento6 páginasMaximo Jagualing Et Al Vs Court of Appeals Et Allailani murilloAinda não há avaliações

- Property 2 1-5Documento3 páginasProperty 2 1-5Di Ako Si SalvsAinda não há avaliações

- Custom Search: Judicial Issuances Other Issuances Jurisprudence International Legal Resources AUSL ExclusiveDocumento5 páginasCustom Search: Judicial Issuances Other Issuances Jurisprudence International Legal Resources AUSL ExclusiveAnonymous hMaKmCCMAinda não há avaliações

- Cases in Property - OwnershipDocumento38 páginasCases in Property - OwnershipSusie VanguardiaAinda não há avaliações

- Heirs of Emiliano Navarro, Petitioner, vs. Intermediate Appellate Court and Heirs of Sinforoso PascualDocumento12 páginasHeirs of Emiliano Navarro, Petitioner, vs. Intermediate Appellate Court and Heirs of Sinforoso PascualJanileahJudetteInfanteAinda não há avaliações

- 3 - Ownership - CasesDocumento53 páginas3 - Ownership - CasesJoie MonedoAinda não há avaliações

- Francisco vs. IAC 177 SCRA 527Documento5 páginasFrancisco vs. IAC 177 SCRA 527FranzMordenoAinda não há avaliações

- Palomo V CADocumento5 páginasPalomo V CAMario MauzarAinda não há avaliações

- 3-1 Javier Vs ConcepcionDocumento7 páginas3-1 Javier Vs ConcepcionjunaAinda não há avaliações

- Sub-Surface and Hidden TreasureDocumento25 páginasSub-Surface and Hidden TreasureMa Tiffany CabigonAinda não há avaliações

- Rev. 2.11. 135056-1985-Escaler - v. - Court - of - Appeals PDFDocumento6 páginasRev. 2.11. 135056-1985-Escaler - v. - Court - of - Appeals PDFMilane Anne CunananAinda não há avaliações

- Cases - OwnershipDocumento38 páginasCases - OwnershipSusie VanguardiaAinda não há avaliações

- Accession CasesDocumento98 páginasAccession CasesMark Joseph Delima100% (2)

- PROPERTY Accession NaturalDocumento52 páginasPROPERTY Accession NaturalfecretaryofftateAinda não há avaliações

- Benito Ylarde Et Al. V Crisanto Lichauco, Et AlDocumento4 páginasBenito Ylarde Et Al. V Crisanto Lichauco, Et AlJohn YeungAinda não há avaliações

- Montano vs. Insular Government (G.R. No. 3714, January 26, 1909)Documento104 páginasMontano vs. Insular Government (G.R. No. 3714, January 26, 1909)Alelojo, NikkoAinda não há avaliações

- Civil Procedure - CasesDocumento17 páginasCivil Procedure - CasesCherry May SanchezAinda não há avaliações

- Jaugaling vs. CADocumento6 páginasJaugaling vs. CAEmAinda não há avaliações

- Untitled 41Documento4 páginasUntitled 41Cherry UrsuaAinda não há avaliações

- 1PROPERTY CASES-Concept of OwnershipDocumento45 páginas1PROPERTY CASES-Concept of OwnershipizaAinda não há avaliações

- Javier V ConcepcionDocumento9 páginasJavier V ConcepcionRomar John M. GadotAinda não há avaliações

- Del Fierro vs. SeguiranDocumento8 páginasDel Fierro vs. SeguiranMj BrionesAinda não há avaliações

- Land Titles Case DigestsDocumento11 páginasLand Titles Case DigestsJoanne Rosaldes Ala100% (1)

- Escaler Vs CADocumento4 páginasEscaler Vs CAjessapuerinAinda não há avaliações

- CaseDocumento10 páginasCaseBlue RoseAinda não há avaliações

- Del Fierro Vs SeguiranDocumento3 páginasDel Fierro Vs SeguiranChris Ronnel Cabrito CatubaoAinda não há avaliações

- Imperial Vs CADocumento10 páginasImperial Vs CAIvan Montealegre ConchasAinda não há avaliações

- First Division G.R. No. 94283, March 04, 1991: Supreme Court of The PhilippinesDocumento11 páginasFirst Division G.R. No. 94283, March 04, 1991: Supreme Court of The PhilippinesRenceAinda não há avaliações

- 022 Hilario V City of ManilaDocumento8 páginas022 Hilario V City of ManilaJunior DaveAinda não há avaliações

- Republic of The Philippines Manila Third Division: Supreme CourtDocumento6 páginasRepublic of The Philippines Manila Third Division: Supreme CourtMyra Mae J. DuglasAinda não há avaliações

- Reynante Vs CA FulltextDocumento4 páginasReynante Vs CA FulltextWii-la MentinoAinda não há avaliações

- 1 Republic vs. Heirs of SinDocumento6 páginas1 Republic vs. Heirs of SinCrisDBAinda não há avaliações

- 2nd Set Property CasesDocumento29 páginas2nd Set Property CasesJayla JocsonAinda não há avaliações

- Javier vs. Concepcion, Jr.Documento6 páginasJavier vs. Concepcion, Jr.Mj BrionesAinda não há avaliações

- Palomo Vs CA LTDDocumento5 páginasPalomo Vs CA LTDJanela LanaAinda não há avaliações

- Property Full Text Cases - OwnershipDocumento40 páginasProperty Full Text Cases - OwnershipyourjurisdoctorAinda não há avaliações

- GR No 68166Documento10 páginasGR No 68166Mary Fatima BerongoyAinda não há avaliações

- Heirs of Emiliano Navarro vs. Intermediate Appellate Court 268 SCRA 74, February 12, 1997Documento20 páginasHeirs of Emiliano Navarro vs. Intermediate Appellate Court 268 SCRA 74, February 12, 1997juan dela cruzAinda não há avaliações

- Caro v. Court of Appeals20210424-14-I8lwdwDocumento10 páginasCaro v. Court of Appeals20210424-14-I8lwdwMaegan Labor IAinda não há avaliações

- Supreme Court: Lorenzo J. Liwag For Petitioner. Dominador Ad Castillo For Private RespondentsDocumento9 páginasSupreme Court: Lorenzo J. Liwag For Petitioner. Dominador Ad Castillo For Private RespondentsMico GutierrezAinda não há avaliações

- LTD CasesDocumento38 páginasLTD CasesEunice EsteraAinda não há avaliações

- Ankron V Gov't. G.R. 14213Documento5 páginasAnkron V Gov't. G.R. 14213Gladys Laureta GarciaAinda não há avaliações

- Case NR 41 G.R. No. 95907 April 8, 1992Documento4 páginasCase NR 41 G.R. No. 95907 April 8, 1992Prime DacanayAinda não há avaliações

- G.R. No. L-46145Documento3 páginasG.R. No. L-46145Bianca BncAinda não há avaliações

- Sec of Vs CaDocumento6 páginasSec of Vs CamalouAinda não há avaliações

- RIBAYADocumento86 páginasRIBAYACristina SurchAinda não há avaliações

- Heirs of Navarro vs. IACDocumento11 páginasHeirs of Navarro vs. IACBea BaloyoAinda não há avaliações

- 03 Leonidas V VargasDocumento14 páginas03 Leonidas V VargasSheenAinda não há avaliações

- Report of the Decision of the Supreme Court of the United States, and the Opinions of the Judges Thereof, in the Case of Dred Scott versus John F.A. Sandford December Term, 1856.No EverandReport of the Decision of the Supreme Court of the United States, and the Opinions of the Judges Thereof, in the Case of Dred Scott versus John F.A. Sandford December Term, 1856.Ainda não há avaliações

- Admin LawDocumento61 páginasAdmin LawabethzkyyyyAinda não há avaliações

- Arbit Part II-AdditionalDocumento21 páginasArbit Part II-AdditionalabethzkyyyyAinda não há avaliações

- PoliDocumento26 páginasPoliabethzkyyyyAinda não há avaliações

- PoliDocumento3 páginasPoliabethzkyyyyAinda não há avaliações

- Republic VSDocumento6 páginasRepublic VSabethzkyyyyAinda não há avaliações

- Arbit Part IIIDocumento74 páginasArbit Part IIIangelescrishanneAinda não há avaliações

- Poli Public Officer DIGESTDocumento7 páginasPoli Public Officer DIGESTabethzkyyyyAinda não há avaliações

- ST. MARTIN FUNERAL HOME, Petitioner, National Labor Relations Commission and Bienvenido ARICAYOS, Respondents. Regalado, J.Documento24 páginasST. MARTIN FUNERAL HOME, Petitioner, National Labor Relations Commission and Bienvenido ARICAYOS, Respondents. Regalado, J.abethzkyyyyAinda não há avaliações

- La Suerte Cigar Vs CaDocumento21 páginasLa Suerte Cigar Vs CaabethzkyyyyAinda não há avaliações

- La Suerte Cigar Vs CADocumento96 páginasLa Suerte Cigar Vs CAabethzkyyyyAinda não há avaliações

- 28 Republic Vs Drugmakers LaboratoriesDocumento3 páginas28 Republic Vs Drugmakers LaboratoriesJoyceAinda não há avaliações

- Arbit Digests August 24Documento17 páginasArbit Digests August 24abethzkyyyyAinda não há avaliações

- Pract CourtDocumento3 páginasPract CourtabethzkyyyyAinda não há avaliações

- Consti Law Case DigestsDocumento90 páginasConsti Law Case DigestsabethzkyyyyAinda não há avaliações

- LTD 10Documento12 páginasLTD 10abethzkyyyyAinda não há avaliações

- Partnership DigestsDocumento7 páginasPartnership DigestsabethzkyyyyAinda não há avaliações

- BANAT V COMELEC G.R. No. 179271 April 21, 2009Documento2 páginasBANAT V COMELEC G.R. No. 179271 April 21, 2009abethzkyyyyAinda não há avaliações

- Goquiolay Vs SycipDocumento1 páginaGoquiolay Vs Sycipabethzkyyyy100% (1)

- Partnership GoquiolayDocumento9 páginasPartnership GoquiolayabethzkyyyyAinda não há avaliações

- PartnershipDocumento27 páginasPartnershipRomel Gregg TorresAinda não há avaliações

- Tiro vs. HontanosasDocumento1 páginaTiro vs. HontanosasabethzkyyyyAinda não há avaliações

- PartnershipDocumento27 páginasPartnershipRomel Gregg TorresAinda não há avaliações

- 1 - Agency Partnership and TrustDocumento35 páginas1 - Agency Partnership and TrustabethzkyyyyAinda não há avaliações

- GSIS Vs KMGDocumento1 páginaGSIS Vs KMGabethzkyyyyAinda não há avaliações

- Digest Art6 Part2'Documento8 páginasDigest Art6 Part2'abethzkyyyyAinda não há avaliações

- People Vs SalasDocumento2 páginasPeople Vs Salasabethzkyyyy100% (2)

- Partnership DigestsDocumento7 páginasPartnership DigestsabethzkyyyyAinda não há avaliações

- Tupaz VS UlepDocumento1 páginaTupaz VS UlepabethzkyyyyAinda não há avaliações

- Municipality Vs IAC - GDocumento1 páginaMunicipality Vs IAC - GC.J. EvangelistaAinda não há avaliações

- People Vs CabilesDocumento1 páginaPeople Vs Cabilesabethzkyyyy100% (1)

- The ReformationDocumento20 páginasThe ReformationIlyes FerenczAinda não há avaliações

- Polynomials Level 3Documento17 páginasPolynomials Level 3greycouncilAinda não há avaliações

- Behaviour of Investors in Indian Equity Markets: Submitted byDocumento26 páginasBehaviour of Investors in Indian Equity Markets: Submitted byDibyanshu AmanAinda não há avaliações

- Middle Grades ReportDocumento138 páginasMiddle Grades ReportcraignewmanAinda não há avaliações

- Clinimetrics Single Assessment Numeric EvaluationDocumento1 páginaClinimetrics Single Assessment Numeric EvaluationNicol SandovalAinda não há avaliações

- Professional Education Pre-Licensure Examination For TeachersDocumento12 páginasProfessional Education Pre-Licensure Examination For TeachersJudy Mae ManaloAinda não há avaliações

- Final Research ReportDocumento14 páginasFinal Research ReportAlojado Lamuel Jesu AAinda não há avaliações

- Week 6 Starbucks Leading Change 2023Documento10 páginasWeek 6 Starbucks Leading Change 2023Prunella YapAinda não há avaliações

- Organigation DeveDocumento3 páginasOrganigation Devemerin sunilAinda não há avaliações

- PsychFirstAidSchools PDFDocumento186 páginasPsychFirstAidSchools PDFAna ChicasAinda não há avaliações

- Tender Documents-Supply and Installation of TVET Equipment and Tools (4) (23) Feb FinalDocumento166 páginasTender Documents-Supply and Installation of TVET Equipment and Tools (4) (23) Feb Finalracing.phreakAinda não há avaliações

- India Marine Insurance Act 1963Documento21 páginasIndia Marine Insurance Act 1963Aman GroverAinda não há avaliações

- Vocabulary Task Harry PotterDocumento3 páginasVocabulary Task Harry PotterBest FriendsAinda não há avaliações

- Design of Experiments: I. Overview of Design of Experiments: R. A. BaileyDocumento18 páginasDesign of Experiments: I. Overview of Design of Experiments: R. A. BaileySergio Andrés Cabrera MirandaAinda não há avaliações

- This Study Resource Was: Interactive Reading QuestionsDocumento3 páginasThis Study Resource Was: Interactive Reading QuestionsJoshua LagonoyAinda não há avaliações

- Sales OrganizationsDocumento12 páginasSales OrganizationsmohitmaheshwariAinda não há avaliações

- Nin/Pmjay Id Name of The Vaccination Site Category Type District BlockDocumento2 páginasNin/Pmjay Id Name of The Vaccination Site Category Type District BlockNikunja PadhanAinda não há avaliações

- CV AmosDocumento4 páginasCV Amoscharity busoloAinda não há avaliações

- Baltimore Catechism No. 2 (Of 4)Documento64 páginasBaltimore Catechism No. 2 (Of 4)gogelAinda não há avaliações

- NorthStar 5th Edition Reading-Writing SKILLS 3-4Documento265 páginasNorthStar 5th Edition Reading-Writing SKILLS 3-4Hassan JENZYAinda não há avaliações

- Analysis of Low-Frequency Passive Seismic Attributes in Maroun Oil Field, IranDocumento16 páginasAnalysis of Low-Frequency Passive Seismic Attributes in Maroun Oil Field, IranFakhrur NoviantoAinda não há avaliações

- Grade 5 Forces Acting On Structures and Mechanisms CirriculumDocumento3 páginasGrade 5 Forces Acting On Structures and Mechanisms Cirriculumapi-2072021750% (1)

- Reading İzmir Culture Park Through Women S Experiences Matinee Practices in The 1970s Casino SpacesDocumento222 páginasReading İzmir Culture Park Through Women S Experiences Matinee Practices in The 1970s Casino SpacesAta SagirogluAinda não há avaliações

- Character Formation 1: Nationalism and PatriotismDocumento11 páginasCharacter Formation 1: Nationalism and Patriotismban diaz100% (1)

- ThesisDocumento58 páginasThesisTirtha Roy BiswasAinda não há avaliações

- Unsaturated Polyester Resins: Influence of The Styrene Concentration On The Miscibility and Mechanical PropertiesDocumento5 páginasUnsaturated Polyester Resins: Influence of The Styrene Concentration On The Miscibility and Mechanical PropertiesMamoon ShahidAinda não há avaliações

- Biblehub Com Commentaries Matthew 3 17 HTMDocumento21 páginasBiblehub Com Commentaries Matthew 3 17 HTMSorin TrimbitasAinda não há avaliações

- Radiopharmaceutical Production: History of Cyclotrons The Early Years at BerkeleyDocumento31 páginasRadiopharmaceutical Production: History of Cyclotrons The Early Years at BerkeleyNguyễnKhươngDuyAinda não há avaliações

- Drug Distribution MethodsDocumento40 páginasDrug Distribution MethodsMuhammad Masoom Akhtar100% (1)

- Entity-Level Controls Fraud QuestionnaireDocumento8 páginasEntity-Level Controls Fraud QuestionnaireKirby C. LoberizaAinda não há avaliações