Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

American Journal of Archaelology

Enviado por

Ivan MarjanovicDireitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

American Journal of Archaelology

Enviado por

Ivan MarjanovicDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

AMERICAN JOURNAL

OF ARCHAEOLOGY

THE JOURNAL OF THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL INSTITUTE OF AMERICA

Volume 106

No. 1 January 2002

ARCHAEOLOGICAL INSTITUTE OF AMERICA

2001

OFFICERS

Nancy C. Wilkie, President

Jane C. Waldbaum, First Vice President

Ricardo J. Elia, Vice President for Professional Responsibilities

Naomi J. Norman, Vice President for Publications

Cameron Jean Walker, Vice President for Societies

Jeffrey A. Lamia, Treasurer

Stephen L. Dyson, Past President

Hector Williams, President, AIA Canada

HONORARY PRESIDENTS

Frederick R. Matson, Robert H. Dyson, Jr.,

Machteld J. Mellink, James R. Wiseman,

Martha Sharp Joukowsky, James Russell

GOVERNING BOARD

TRUSTEES EMERITI

Jacqueline Rosenthal, Executive Director

Leonard V. Quigley, of Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton & Garrison, General Counsel

Elie M. Abemayor

Karen Alexander

Patricia Rieff Anawalt

Elizabeth Bartman

Mary Beth Buck

Eric H. Cline

Michael Cosmopoulos

Susan Downey

Alfred Eisenpreis

Neathery Batsell Fuller

Kevin Glowacki

Eleanor Guralnick

James R. James, Jr.

Charles S. La Follette

Richard Leventhal

Jodi Magness

Carol C. Mattusch

Francis P. McManamon

Andrew M.T. Moore

Dorinda J. Oliver

Kathleen A. Pavelko

Alice S. Riginos

John J. Roche

Anne H. Salisbury

Catherine Sease

John H. Stubbs

Barbara Tsakirgis

Patty Jo Watson

Michael Wiseman

MEMBERSHIP IN THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL INSTITUTE OF AMERICA

AND SUBSCRIPTION TO THE AMERICAN JOURNAL OF ARCHAEOLOGY

The American Journal of Archaeology is published by the Archaeological Institute of America in January,

April, July, and October. Membership in the AIA, including a subscription to AJA, is $85 per year (C$123).

Student membership is $40 (C$58); proof of full-time status required. A brochure outlining membership

benefits is available upon request from the Institute. An annual subscription to AJA is $75 (international,

$95); the institutional subscription rate is $250 (international, $290). Institutions are not eligible for

individual membership rates. All communications regarding membership, subscriptions, and back issues

should be addressed to the Archaeological Institute of America, located at Boston University, 656 Beacon

Street, Boston, Massachusetts 02215-2006, tel. 617-353-9361, fax 617-353-6550, email aia@aia.bu.edu.

Richard H. Howland Norma Kershaw

AMERICAN JOURNAL

OF ARCHAEOLOGY

THE JOURNAL OF THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL INSTITUTE OF AMERICA

EDITORS

R. Bruce Hitchner, University of Dayton

Editor-in-Chief

Paul Rehak & John G. Younger, University of Kansas

Co-editors, Book Reviews

ADVISORY BOARD

Naomi J. Norman, ex officio

University of Georgia

EDITORIAL ASSISTANTS

Kathryn Armstrong, Trina Arpin, Krithiga Sekar

Susan E. Alcock

University of Michigan

Roger Bagnall

Columbia University

Larissa Bonfante

New York University

Joseph C. Carter

University of Texas at Austin

John F. Cherry

University of Michigan

Stephen L. Dyson

State University of New York at Buffalo

Jonathan Edmondson

York University

Elizabeth Fentress

Rome, Italy

Timothy E. Gregory

Ohio State University

Julie M. Hansen

Boston University

Kenneth W. Harl

Tulane University

Sharon C. Herbert

University of Michigan

Ann Kuttner

University of Pennsylvania

Claire Lyons

The Getty Research Institute

John T. Ma

Princeton University

David Mattingly

University of Leicester

Ian Morris

Stanford University

Robin Osborne

Cambridge University

Curtis N. Runnels

Boston University

Mary M. Voigt

College of William and Mary

Marni Blake Walter

Editor

Kevin Mullen

Electronic Operations Manager

THE AMERICAN JOURNAL OF ARCHAEOLOGY, the journal of the Archaeological Institute of America,

was founded in 1885; the second series was begun in 1897. Indexes have been published for

volumes 111 (18851896), for the second series, volumes 110 (18971906) and volumes 1170

(19071966). The Journal is indexed in the Humanities Index, the ABS International Guide to Classical

Studies, Current Contents, the Book Review Index, the Avery Index to Architectural Periodicals, Anthropological

Literature: An Index to Periodical Articles and Essays, and the Art Index.

MANUSCRIPTS and all communications for the editors should be addressed to Professor R. Bruce

Hitchner, Editor-in-Chief, AJA, Archaeological Institute of America, located at Boston University, 656

Beacon Street, Boston, Massachusetts 02215-2006, tel. 617-353-9364, fax 617-353-6550, email

aja@aia.bu.edu. The American Journal of Archaeology is devoted to the art and archaeology of ancient

Europe and the Mediterranean world, including the Near East and Egypt, from prehistoric to late

antique times. The attention of contributors is directed to Editorial Policy, Instructions for Contributors,

and Abbreviations, AJA 104 (2000) 324. Guidelines for AJA authors can also be found on the World

Wide Web at www.ajaonline.org. Contributors are requested to include abstracts summarizing the

main points and principal conclusions of their articles. Manuscripts, including photocopies of

illustrations, should be submitted in triplicate; original photographs, drawings, and plans should not

be sent unless requested by the editors. In order to facilitate the peer-review process, all submissions

should be prepared in such a way as to maintain anonymity of the author. As the official journal of

the Archaeological Institute of America, AJA will not serve for the announcement or initial

scholarly presentation of any object in a private or public collection acquired after 30 December

1970, unless the object was part of a previously existing collection or has been legally exported

from the country of origin.

BOOKS FOR REVIEW should be sent to Professors Paul Rehak and John G. Younger, Co-editors, AJA

Book Reviews, Classics Department, Wescoe Hall, 1445 Jayhawk Blvd., University of Kansas, Lawrence,

Kansas 66045- 2139, tel . 785- 864- 3153, fax 785- 864- 5566, emai l prehak@ukans. edu and

jyounger@ukans.edu (please use both addresses for all correspondence). The following are excluded

from review and should not be sent: offprints; reeditions, except those with great and significant

changes; journal volumes, except the first in a new series; monographs of very small size and scope;

and books dealing with the archaeology of the New World.

THE AMERICAN JOURNAL OF ARCHAEOLOGY (ISSN 0002-9114) is published four times a year in

January, April, July, and October by the Archaeolgocial Institute of America, located at Boston Uni-

versity, 656 Beacon Street, Boston, Massachusetts 02215-2006, tel. 617-353-9361, fax 617-353-6550,

email aia@aia.bu.edu. Subscriptions to the American Journal of Archaeology may be addressed to the

Institute headquarters in Boston. An annual subscription is $75 (international, $95); the institutional

rate is $250 (international, $290). Membership in the AIA, including a subscription to AJA, is $85 per

year (C$123). Student membership is $40 (C$58); proof of full-time status required. International

subscriptions and memberships must be paid in U.S. dollars, by a check drawn on a bank in the U.S.

or by money order. No replacement for nonreceipt of any issue of AJA will be honored after 90 days

(180 days for international subscriptions) from the date of issuance of the fascicle in question. When

corresponding about memberships or subscriptions, always give your account number, as shown on

the mailing label or invoice. A microfilm edition of the Journal, beginning with volume 53 (1949), is

issued after the completion of each volume of the printed edition. Subscriptions to the microfilm

edition, which are available only to subscribers to the printed edition of the Journal, should be sent

to ProQuest Information and Learning (formerly Bell & Howell Information and Learning), 300

North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106. Back numbers of AJA and the Index 19071966 may be

ordered from the Archaeological Institute of America in Boston. Exchanged periodicals and

correspondence relating to exchanges should be directed to the AIA in Boston. Periodicals postage

paid at Boston, Massachusetts and additional mailing offices. Postmaster: send address changes to the

American Journal of Archaeology, Archaeological Institute of America, located at Boston University, 656

Beacon Street, Boston, Massachusetts 02215-2006.

The opinions expressed in the articles and book reviews published in the American Journal of Archaeology

are those of the authors and not of the editors or of the Archaeological Institute of America.

Copyright 2002 by the Archaeological Institute of America

The American Journal of Archaeology is composed in ITC New Baskerville

at the Journals editorial offices, located at Boston University.

The paper in this journal is acid-free and meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the

Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources.

AMERICAN JOURNAL OF ARCHAEOLOGY

Volume 106

No. 1 January 2002

ARTICLES

Eileen Murphy, Ilia Gokhman, Yuri Chistov, and Ludmila Barkova:

Prehistoric Old World Scalping: New Cases from the Cemetery of

Aymyrlyg, South Siberia 1

Gloria Ferrari: The Ancient Temple on the Acropolis at Athens 11

Ezequiel M. Pinto-Guillaume: Mollusks from the Villa of Livia at

Prima Porta, Rome: The Swedish Garden Archaeological Project,

19961999 37

Rabun Taylor: Temples and Terracottas at Cosa 59

ESSAY

Christina Riggs: Facing the Dead: Recent Research on the Funerary

Art of Ptolemaic and Roman Egypt 85

NECROLOGY

Nancy C. Wilkie: William Donald Edward Coulson, 19422001 103

REVIEWS

Review Article

Barbara Burrell: Out-Heroding Herod 107

Book Reviews

Blench and Spriggs, eds., Archaeology and Language. Vol. 1, Theoretical

and Methodological Orientations (J.S. Smith) 111

Gove, From Hiroshima to the Iceman: The Development and Applications of

Accelerator Mass Spectrometry (R.A. Housley) 112

Ramage and Craddock, King Croesus Gold: Excavations at Sardis and the

History of Gold Refining (D. Killick) 113

Pye and Allen, Coastal and Estuarine Environments: Sedimentology,

Geomorphology and Geoarchaeology (P. Goldberg) 114

Borbein, Hlscher, and Zanker, eds., Klassische Archologie:

Eine Einfhrung (W.M. Calder III) 115

Hrke, ed., Archaeology, Ideology and Society: The German Experience

(R. Bernbeck) 116

Chamay, Courtois, and Rebetez, Waldemar Deonna: Un archologue

derrire lobjectif de 1903 1939 (A. Szegedy-Maszak) 118

Donald and Hurcombe, eds., Gender and Material Culture in

Archaeological Perspective, and

Donald and Hurcombe, eds., Gender and Material Culture in Historical

Perspective (J. Gero) 118

Price, ed., Europes First Farmers (K.J. Fewster) 120

Barclay and Harding, eds., Pathways and Ceremonies: The Cursus

Monuments of Britain and Ireland,

Ruggles, Astronomy in Prehistoric Britain and Ireland, and

Burl, Great Stone Circles (K. Jones-Bley) 121

Hitchcock, Minoan Architecture: A Contextual Analysis (J.C. Mcenroe) 123

Hallager and Hallager, eds., The Greek-Swedish Excavations at the

Agia Aikaterini Square Kastelli, Khania 19701987. Vol. 2, The Late

Minoan IIIC Settlement (L.P. Day) 124

Bowman and Rogan, eds., Agriculture in Egypt from Pharaonic to Modern

Times (C.E.P. Adams) 125

Potts, The Archaeology of Elam: Formation and Transformation of an Ancient

Iranian State (P. Amiet) 126

Burns, Monuments of Syria: An Historical Guide (A.H. Joffe) 127

Coleman and Walz, eds., Greeks and Barbarians: Essays on the Interactions

between Greeks and Non-Greeks in Antiquity and the Consequences for

Eurocentrism (I. Malkin) 128

Fossey, ed., Boeotia Antiqua. Vol. 6, Proceedings of the 8th International

Conference on Boiotian Antiquities (Loyola University of Chicago, 2426 May

1995) (D.W. Roller) 130

Splitter, Die Kypseloslade in Olympia: Form, Funktion und Bildschmuck.

Eine archologische Rekonstruktion. Mit einem Katalog der Sagenbilder in der

korinthischen Vasenmalerei und einem Anhang zur Forschungsgeschichte

(M.D. Stansbury-ODonnell) 131

Radt, Pergamon: Geschichte und Bauten einer antiken Metropole, and

Wulf, Altertmer von Pergamon. Vol. 15, Die Stadtgrabung, pt. 3, Die

hellenistischen und rmischen Wohnhuser von Pergamon: Unter besonderer

Bercksichtigung der Anlagen zwischen der Mittel- und der Ostgasse

(B.A. Ault) 132

Vlizos, Der thronende Zeus: Eine Untersuchung zur statuarischen Ikonographie

des Gottes in der sptklassischen und hellenistischen Kunst (G. Waywell) 134

Neils and Walberg, Corpus Vasorum Antiquorum. USA 35: The Cleveland

Museum of Art 2 (J.M. Padgett) 135

Tomei, Scavi francesi sul Palatino: Le indagini di Pietro Rosa per Napoleone

III (18611870) (L. Richardson, jr) 137

Steinby, ed., Lexicon topographicum urbis Romae. Vol. 5, TZ. Addenda et

corrigenda (L. Richardson, jr) 138

Bejor, Vie colonnate: Paesaggi urbani del mondo antico (A.B. Griffith) 139

Bergmann, Chiragan, Aphrodismas, Konstantinopel: Zur mythologischen

Skulptur der Sptantike (N. Hannestad) 140

Gilli, I materiali archeologici della raccolta Nyry del Museo Civico Correr di

Venezia (P. Biagi) 141

Cabanes, ed., LIllyrie mridionale et lpire dans lantiquit. Vol. 3, Actes du

3

e

colloque international de Chantilly (1619 octobre 1996)

(V.R. Anderson-Stojanovic) 142

Davidson, Roles of the Northern Goddess (N.L. Wicker) 144

Sasse, Westgotische Grberfelder auf der iberischen Halbinsel am Beispiel der

Funde aus El Carpio de Tajo (Torrijos, Toledo) (S. Noack-Haley) 145

BOOKS RECEIVED 146

American Journal of Archaeology 106 (2002) 110

1

Abstract

Evidence for three definitive cases of scalping have

been identified among the corpus of human skeletal

remains excavated from the Iron Age south Siberian cem-

etery of Aymyrlyg in Tuva. The osteological evidence for

scalping that is apparent in these individuals is presented

here, as are the results of a recent reexamination of a

previously known south Siberian case from the royal burial

in Kurgan 2 at Pazyryk. These four Iron Age Siberian

cases of scalping are important in part because they sup-

port the literary references pertaining to the practice

contained in Herodotuss Histories, written in the fifth

century B.C. Osteological evidence for scalping in pre-

historic Old World contexts, including cases previously

reported only in German and Russian publications, is also

reviewed.*

The term Scythian world is applied to a group

of archaeological cultures that date from approxi-

mately the seventh to the second centuries B.C. and

are located in the zone of the steppes, forest-

steppes, foothills, and mountains of the Ukraine,

Russia, Kazakhstan, Mongolia, and the northern

part of China.

1

The cultures comprising the Scyth-

ian world are, therefore, wide ranging. The Greeks

referred to the nomads of Eurasia and Central Asia

as the Scythians, while the Persians designated all

nomadic tribes of the Eurasian steppes (including

the Scythians) as the Saka.

2

The Scythian period

culture in Tuva is called the Uyuk Culture, a name

that derived from the Uyuk river basin, where the

first scientific excavations of monuments of this

culture occurred.

3

The Uyuk Culture was bordered

by two other Scythian period cultures, the Pazyryk

Culture to the west, and the Tagar Culture to the

north.

4

The history of the Central Asian nomads is in-

separable from that of the nomadic and semino-

madic tribes of the Eurasian steppes. Their materi-

al culture and political and economic practices were

markedly similar.

5

The common material culture

apparent among all the tribes of the Scythian world

is known as the Scythian Triad, and consists of weap-

ons, horse harnesses, and objects decorated in the

Animal style of artwork.

6

Although the artifacts of

the Scythian Triad display marked similarities, oth-

er components of the Scythian world (such as dwell-

ings, burial customs, ceramics, and adornments)

differ considerably among the various cultures.

Consequently, it is not possible to envisage a single

Scythian culture but rather a variety of cultures of

the Scythian world,

7

and the Scythian empire was

not a centralized state, but rather a confederation

of powerful nomadic clans.

8

During the late third and early second century

B.C. several significant social changes occurred

among the nomadic tribes of the steppes. In the

west the Sarmatians succeeded the Scythians, while

in the east the Xiongnu, who are often presumed

to be the ancestors of the later Huns, had emerged

as a strong nomadic power. This period in the his-

tory of the steppe nomads thus is referred to as the

Hunno-Sarmatian period.

9

As a result of their in-

creased prosperity from pastoralism, the develop-

ment of an iron industry, and military prowess, the

24 Xiongnu tribes dramatically rose in strength,

resulting in the emergence of the powerful Xiong-

nu empire.

10

According to the historical sources

the Xiongnu initially engaged in a lengthy strug-

Prehistoric Old World Scalping:

New Cases from the Cemetery of Aymyrlyg,

South Siberia

EILEEN MURPHY, ILIA GOKHMAN, YURI CHISTOV, AND LUDMILA BARKOVA

*

We would like to acknowledge Dr. Colm Donnelly, School

of Archaeology and Palaeoecology, Queens University Belfast,

for his comments on the text. We are also grateful to Professor

Don Brothwell, Department of Archaeology, University of York,

for drawing our attention to the Alvastra case in Sweden. We

would also like to thank Dr. Rupert Breitwieser, Institute for

Ancient History, University of Salzburg, for informing us of

the case of scalping from Regensburg-Harting in Bavaria.

1

Clenova 1994, 499.

2

Abetekov and Yusupov 1994, 24.

3

Mannai-Ool 1970, 8.

4

Mandelshtam 1992, 179.

5

Abetekov and Yusupov 1994, 23.

6

Moskova 1994, 231.

7

Clenova 1994, 5001.

8

Vernadsky 1943, 51.

9

Zadneprovskiy 1994, 457.

10

Ishjamts 1994, 153.

EILEEN MURPHY ET AL. 2 [AJA 106

gle against other nomadic tribes, particularly the

Wu-sun and the Yeh-chih, as well as with the Chi-

nese,

11

and for several centuries the Xiongnu em-

pire acted as a rival power to the Han empire of

China. At its greatest extent the Xiongnu empire

is thought to have stretched from Korea to the Al-

tai, and from the border of China to Transbaika-

lia.

12

At the end of the third and the beginning of

the second century B.C. the populations of Tuva,

the Transbaikalia area, the Minusinsk Basin, and

the Altai are all considered to have experienced

the impact of Xiongnu military force.

13

The Hunno-Sarmatian period culture in Tuva is

referred to as the Shurmak Culture. The older

Scythian period Uyuk Culture in Tuva does not

appear to have totally disappeared from the archae-

ological record, however, and a large proportion of

its characteristicsits funerary monuments, burial

rituals, and grave goodsseem to have become as-

similated into the new Shurmak Culture.

14

Artifacts recovered from Scythian period funer-

ary monuments in Tuva indicate that the economy

of the highland-steppe peoples was based upon a

seminomadic form of pastoralism, which was com-

bined with land cultivation and hunting and gath-

ering. The Scythian period tribes of the mountain-

steppe regions of Tuva would have made vertical

shifts seasonally, with the construction of perma-

nent structures undertaken in the lowlands dur-

ing the winter months.

15

This form of economy

would have involved regular repeated seasonal

migrations within the borders of a relatively defined

territory.

16

The Shurmak Culture in Tuva is consid-

ered to have had a similar seminomadic pastoralist

economy to that of the preceding Uyuk Culture but

with a greater degree of mobility.

As was the case for

the Scythian period, the existence of tribal burial

grounds in Tuva of Hunno-Sarmatian period date

indicates that cyclic migration continued in this

era; tribes alternately moved through their land

along fixed routes and maintained set camp sites

during winters.

17

A large variety of weaponry was

contained in the burials of both the Uyuk and Shur-

mak Cultures, indicating the important role that

warfare played in society.

the cemetery of aymyrlyg

The cemetery complex of Aymyrlyg is situated in

the Ulug-Khemski region of the Republic of Tuva

in south Siberia (fig. 1). The site was excavated

between 1968 and 1984 by archaeologists of the

Sayano-Tuvinskaya expedition team from the Insti-

tute for the History of Material Culture in St. Pe-

tersburg. Dr. A.M. Mandelshtam directed the exca-

vations from 1968 to 1978, and Dr. E.U. Stambulnik

continued the research until the mid 1980s. The

majority of burials excavated by Mandelshtam were

from the Uyuk Culture of the Scythian period (ca.

seventhsecond centuries B.C.), with the greatest

proportion dating to the third and second centu-

ries B.C. Most of the burials from the later years of

the program, under the direction of Stambulnik,

originated from the Hunno-Sarmatian period (ca.

first century B.C.A.D. second century).

The most common form of interior structure in

Scythian period funerary monuments was the rect-

angular log house tomb. Invariably, the numbers of

individuals buried within an Aymyrlyg log house

tomb could be considerable, with as many as 15 skel-

etons being recovered from individual examples.

Stone cists of Scythian period date were also com-

monly encountered at Aymyrlyg.

18

Burial in a com-

posite wooden coffin or, less frequently, in a hollowed

out log or wooden block was characteristic for the

Hunno-Sarmatian period. The majority of these buri-

als contained a single individual, although several

double and triple burials were discovered.

19

Some 1,000 human skeletons were recovered

from the Aymyrlyg cemetery, and the skeletal re-

mains are now stored in the Department of Physi-

cal Anthropology of the Peter the Great Museum

of Anthropology and Ethnography (Kunstkammer)

in St. Petersburg. A recent paleopathological ex-

amination of the skeletal remains identified three

cases of scalping in this corpus.

20

The osteological

characteristics of these three cases and a further

Scythian period example from Kurgan 2 at Pazyryk,

also in south Siberia, are analyzed below.

siberian cases of scalping

Scalping may be defined as the forcible removal

of all or part of the scalp from the head. The proce-

dure involves the incision of the skin overlying the

skull with a sharp object in a circular pattern

21

to

enable the easy removal of the soft tissues from the

cranial vault.

22

The practice has been undertaken

throughout the past among different world cul-

tures, usually in order to retrieve human trophies

11

Litvinsky and Guang-da 1996, 29.

12

Phillips 1965, 112.

13

Davidova 1996, 159.

14

Mannai-Ool 1970, 108.

15

Vainshtein 1980, 51.

16

Mandelshtam 1992, 193.

17

Vainshtein 1980, 96.

18

Mandelshtam 1983, 26.

19

Stambulnik 1983, 347.

20

Murphy 1998.

21

Axtell and Sturtevant 1980, 467.

22

Hamperl 1967, 630.

PREHISTORIC OLD WORLD SCALPING 3 2002]

as indicators of success and bravery in warfare. It

has also been suggested that scalping may have

been undertaken for therapeutic or magico-reli-

gious reasons.

23

The first case from the Aymyrlyg cemetery with

clear evidence for scalping is a Scythian period male

with an age at death of 2535 years. Healed frac-

tured nasal bones were apparent. Unfortunately,

the context for this case was uncertain, and only

the skull was available for analysis. Numerous small

sharp cut marks, with an appearance that was indic-

ative they had been made using a metal tool, were

apparent on the surface of the cranial vault. The

cut marks ranged in length from 4 mm to 62 mm,

and followed the circumference of the skull. The

characteristics of the cut marks suggest that the

objective of the scalper had been to carefully re-

move a circular area of skin from the superior and

posterior aspects of the cranium. The cut marks on

the occipital and the posterior regions of the pari-

etals ran in a horizontal direction, parallel to one

another. The superior margins of the cut marks

were generally beveled, which may indicate that the

person who had made the marks had been posi-

tioned superior to the skull, and that the skin had

been peeled off in an anterior direction. No signs

of healing were associated with the scalping cut

marks, and it is therefore probable that the proce-

dure may have occurred either immediately prior

to death or during the perimortem period.

23

Owsley 1994, 3378.

CHINA

KAZAKHSTAN

MONGOLIA

RUSSIA

Aymyrlyg

Pazyryk

Ob

Yenisey

Km

0 100 200

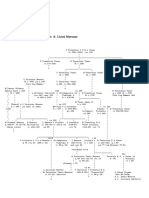

Fig. 1. Map showing the location of Aymyrlyg and Pazyryk

EILEEN MURPHY ET AL. 4 [AJA 106

Two Hunno-Sarmatian period individuals exca-

vated from the Aymyrlyg cemetery also displayed

clear evidence of scalping. Both individuals were

buried in the same tomb, and it is therefore proba-

ble that they had been scalped concomitantly. The

cut marks apparent in Skeleton XXXI. 87. Sk. 1, a

1725 year old male individual, and in Skeleton

XXXI. 87. Sk. 2, a 3545 year old male, were practi-

cally identical in morphology and location (figs. 2

3; hereafter termed Sk. 1 and Sk. 2). This may indi-

cate that a single individual had carried out both

procedures. In both cases numerous small sharp

cut marks were apparent on the surface of the cra-

nial vault. The cut marks again followed the cir-

cumference of the skull, and their morphology sug-

gested that the objective of the scalpers had been

to carefully remove a circular area of skin from the

superior and posterior aspects of the cranium. The

cut marks on the occipital and the posterior regions

of the parietals ran in a horizontal direction, paral-

lel to one another. The superior margins of the cut

marks were generally beveled, which may indicate

that the individuals responsible for making them

had been positioned superior to the skull, and that

the skin had been peeled off in an anterior direc-

tion. The cut marks on the frontal bone and the

anterior aspect of the right parietal also displayed

beveled superior margins, which may suggest they

had been made in the opposite direction.

Evidence of sword injuries was also present in

the remains of both Hunno-Sarmatian period indi-

viduals. A sword cut was present on the neural arch-

es of the 11th and 12th thoracic vertebrae in Sk. 1,

which indicates that the attacker had been posi-

tioned behind the individual. A sword cut was also

apparent on the right femur of Sk. 2. It is probable,

therefore, that both individuals had been em-

broiled in a single episode of violence, which pos-

sibly involved armed combat and, perhaps follow-

ing their defeat, they had been deliberately and

methodically scalped. Based on the clear evidence

for weapon injuries and lack of signs of healing

associated with the scalping cut marks of either in-

dividual, it is possible that the scalping procedures

occurred immediately prior to death or during the

perimortem period; the victors of the attack may

then have taken the scalps as war trophies. A spear-

head and a variety of knives were recovered from

the burial, possibly indicating the warrior status of

the two men. The circumstances of the formal buri-

al accorded to the two individuals also suggest that

the bodies had been retrieved by their relatives and

friends and had then been buried as befitted their

status in life.

A high status male individual with battle-axe in-

juries from Kurgan 2 at Pazyryk in the High Altai

also displayed evidence for scalping (fig. 4). Ser-

gei Rudenko, the excavator of the kurgan, provid-

ed a detailed description of the mummified indi-

vidual. He concluded that the scalp had been re-

moved from the cranium after death, and stated

that the skin above the forehead had been cut

through from ear to ear and then torn backward to

expose the skull as far as the neck. Prior to burial a

scalp from another individual had been attached

to the anterior aspect of the cranium with horse-

hair.

24

Three perforations caused by blows from a

battle-axe were visible on the parietals. Similar bat-

tle-axe injuries were apparent on numerous Scyth-

ian period individuals from Aymyrlyg and, in prac-

tically all cases, these injuries would have resulted

in death.

25

The Pazyryk mummy is currently housed in the

Department of Archaeology in the State Hermit-

age Museum of St. Petersburg. A recent reexami-

nation of the mummy by the current authors has

identified the injuries and postmortem alterations

described by Rudenko. In addition, however, a

number of small cut marks, clearly indicative of

scalping, were also discovered to be present on the

skull. As has been postulated for the two Hunno-

Sarmatian period individuals from Aymyrlyg, it is

probable that the Pazyryk male had been scalped

in the aftermath of an incident of combat, with his

scalp removed as a war trophy. Again, it would seem

that his body had been retrieved and formally bur-

ied by his kith and kin.

Within the New World, the remains of a number

of scalped individuals have been discovered asso-

ciated with grave goods. In contrast to the Siberian

examples, these individuals show no signs of hav-

ing met a violent end but were given mortuary treat-

ment and deliberate burial. This finding may sug-

gest that their scalps had been removed for other

cultural purposes apart from warfare. It is known

that a number of Native American tribes regarded

a scalp to have a supernatural or religious signifi-

cance.

26

Among the Pueblo tribes, scalps were re-

lated to sacrifices and ceremonies conducted to

bring rain. Scalps were also used for therapeutic

reasons among Native American tribes; the Nava-

ho, for example, believed that chewing on a scalp

24

Rudenko 1970, 221.

25

Murphy 1998.

26

Owsley 1994, 337.

PREHISTORIC OLD WORLD SCALPING 5 2002]

would cure a toothache.

27

Conversely, however, the

retention of the scalps of dead warriors as battle

trophies appears to have been widely practiced

throughout many geographic regions of the world

including Europe, America, and Africa.

28

Numer-

ous individuals from both the Scythian and Hun-

no-Sarmatian periods formally buried in tombs at

Aymyrlyg displayed evidence of weapon trauma, a

finding that further attests to the warfaring nature

of these tribes.

29

osteological evidence for scalping in

the old world during prehistory

A number of scholars have provided overviews of

the historical references to scalping, which indi-

cate that scalping was practiced throughout both

the Old and New Worlds.

30

Historical references to

the activity in the Old World are contained in a

number of classical sources, perhaps the earliest

and most quoted of which is Herodotuss descrip-

tion of scalping among the Scythians, written in the

fifth century B.C.

31

The majority of the archaeologi-

cal evidence for scalping, however, has been ob-

tained from New World contexts,

32

and a large cor-

pus of material has been investigated.

33

This evi-

dence indicates that scalping was practiced in the

Americas as early as the fifth or sixth centuries A.D.

34

Osteological evidence for Old World scalping is

much less frequent. In addition to the four cases

from Siberia reported here, a small but significant

corpus of cases has been discussed in English, Rus-

sian, and German reportscases that indicate that

scalping has occurred during prehistory at a range

of geographic locations across the Old World. Indi-

vidual case studies

35

and reviews of scalping evi-

dence in both northern Europe

36

and Russia

37

have

Fig. 2. Cut marks indicative of scalping on the frontal bone and right parietal of Sk. 1. (Photo by E. Murphy)

27

Allen et al. 1985.

28

Burton 1864.

29

Murphy 1998.

30

Reese 1940; Anger and Diek 1978.

31

Reese 1940, 7.

32

Roberts and Manchester 1995, 85.

33

Larsen 1997, 119.

34

Owsley 1994, 337.

35

Glob 1969, 93; Fischer 1988, 3940; During and Nilsson

1991; Ortner and Ribas 1997.

36

Anger and Diek 1978.

37

Mednikova 2000.

EILEEN MURPHY ET AL. 6 [AJA 106

been published, and this information is synthesized

below. The following literature-based review pre-

sents summaries of possible cases of scalping in

order to raise awareness of these little-known pur-

ported cases of prehistoric Old World scalping. The

current authors have not physically examined these

crania and, as such, it is difficult to be certain of

their authenticity. This is particularly true for ex-

amples that are not accompanied by published il-

lustrations or photographs.

The earliest cases are of Neolithic date and in-

clude a cranium that dated to approximately 4500

B.C. and was recovered from Dyrholmen Bog, Rand-

ers in Denmark during excavations in the 1920s

and 1930s. The disarticulated remains of a variety

of animals and at least 20 individuals were retrieved,

including the cranial vaults of at least nine people.

A series of shallow cut marks were visible on the

frontal bone and on one of the parietals of a child

of approximately 10 years of age, and these marks

were interpreted as evidence for scalping.

38

A sec-

ond Neolithic cranium that displayed evidence of

scalping, dated to ca. 3000 B.C., was recovered from

the Alvastra pile-dwelling in Sweden during exca-

vations in 1917. The individual was male, aged ap-

proximately 20 years, and his head appeared to have

been decapitated since only the skull, atlas, and

axis were recovered. Cut marks were identified on

the cranium but were found to be restricted to the

frontal bone where they followed the curve of the

bone. The cut marks may have been made using a

stone tool.

39

Finally, the disarticulated remains of at

least three individuals associated with Neolithic

pottery sherds, stone tools, and animal bones were

recovered from Atzenbrugg in Austria, and a num-

ber of the human skull fragments displayed cut

marks that were interpreted as evidence for scalp-

ing.

40

A greater range of case studies has been report-

ed for the Bronze Age in Europe and the Middle

38

Anger and Diek 1978, 1667.

39

Anger and Diek 1978, 16872; During and Nilsson 1991.

40

Anger and Diek 1978, 173.

Fig. 3. Cut marks indicative of scalping on the occipital and left parietal of Sk. 1. (Photo by E. Murphy)

PREHISTORIC OLD WORLD SCALPING 7 2002]

East. The skull of an adult male, with an age at death

greater than 40 years, was recovered from a shaft

tomb at the Early Bronze Age (ca. 32003000 B.C.)

site of Bab-edh-Dhra in Jordan, and displayed evi-

dence of scalping associated with healing. The le-

sion extended from the mid-region of the frontal

through both parietals and onto the occipital. It

had an irregular margin and was associated with a

groove that was indicative of healing. No deliberate

cut marks appear to have been associated with the

lesion, and its irregular margin suggested that the

scalp was torn, rather than cut, from the skull. It has

been suggested that this damage may have been

caused by an animal predator, and that no human

agent was involved.

41

A number of German exam-

ples of scalping during this period have also been

reported. During the 1860s five bog bodies were

retrieved from the Tannenhausener Bog, near

Hamburg, associated with jewelry that was consid-

ered to be of Early Bronze Age date. Hair was visible

on the back and sides of each individuals head,

but in all cases it appeared to have been severed

from the anterior aspect of the skull where sharp

cuts were evident.

42

In addition, the remains of sev-

en scalped headsand in some cases their de-

tached scalpswere reported from among a cor-

pus of skulls discovered within a Bronze Age sanc-

tuary in Bentheim. A number of the heads displayed

cut marks that were considered to be definite evi-

dence of scalping.

43

Maria Mednikova has assembled a corpus of cas-

es of scalping from Bronze Age Russia. A cranium

41

Ortner and Ribas 1997.

42

Anger and Diek 1978, 175.

Fig. 4. View of the right side of the head of the scalped male individual from

Kurgan 2 at Pazyryk. The removal of the skin of the head and neck is clearly

evident, as are two perforations, which were made using a pointed battle axe.

(Photo by Y. Chistov)

43

Anger and Diek 1978, 1756.

EILEEN MURPHY ET AL. 8 [AJA 106

recovered from the Kalinovskaya Kurgan in the Al-

exandrovskova region of the Northern Caucasus

displayed cut marks on its surface that included a

variety of overlapping lines, geometrical patterns,

and triangular and rectangular shapes.

44

Two fur-

ther possible cases of Bronze Age Russian scalping

have been discovered in the Pepkino Kurgan, lo-

cated in the upper basin of the Volga River. The

remains of 27 individuals were discovered in the

kurgan, many of whom displayed injuries caused

by weapon trauma. Burials 12 and 26, both of whom

were adult males, displayed cut marks on their right

parietals.

45

A number of possible cases of scalping that date

to the Iron Age have been recorded in northern

Europe. These include the remains of three par-

tially preserved bodies recovered from Wennigst-

edt in Germany in 1866. None of the individuals

had retained their hair, and cut marks were visible

on their skulls, which were interpreted as evidence

for scalping.

46

A female bog body from Borremose

in Denmark is reported to have had her face crushed

and the back of her head scalped. Although no cut

marks were evident on the cranium, the scalp ap-

peared to display evidence of having been torn from

the skull.

47

Another possible case of scalping origi-

nated from Strandby in Denmark, where the crania

of an adult male and female were discovered. Cut

marks that ran vertical to the hairline were visible

on the female cranium, and were considered to be

indicative that the individual had been scalped.

48

A

human skull recovered from Karlstein in Germany

in 1886 was reported to have displayed sharp cut

marks on its frontal bone. A copper coin that dis-

played the Roman Emperor Hadrian, who reigned

from A.D. 117138, was retrieved from the mouth

region of the skull.

49

Finally, the skulls of a Roman

man and woman dating to the period between the

second and fourth centuries A.D. were recovered

from the well of a villa discovered at Regensburg-

Harting in Bavaria. Both skulls appeared to have

been bludgeoned on their frontal bones. In addi-

tion, the woman seems to have been killed by sever-

al sword blows. A series of cut marks were also evi-

dent on her frontal bone, and these have been in-

terpreted as evidence of scalping.

50

conclusion

The Greeks considered scalping to be so typical

an activity of the Scythians that they invented a spe-

cial verbaposkythizeinto denote the process.

51

Herodotuss description in his Histories, written in

the fifth century B.C., is generally accepted as the

earliest historical reference to the practice.

52

The

heads of vanquished enemies were carefully pro-

cessed with the skin being stripped from the head

by making a circular cut around the ears; the skull

would then have been shaken out. Herodotus also

related how the flesh was scraped from the skin

using an ox rib, cleaned and worked by the warrior

until supple, then used as a form of handkerchief.

The handkerchiefs were hung on the bridle of the

warriors horse as symbols of battle prowess.

53

This

description corresponds perfectly to the evidence

for scalping obtained from the remains of the Scyth-

ian and Hunno-Sarmatian period steppe nomads

from south Siberia discussed in this paper.

An understanding of the Greek fascination with

scalping may be gleaned from an examination of

another unusual practicecannibalismascribed

to the Scythians by Herodotus.

54

This practice was

viewed as a topos by Herodotus and a practice that

was to be associated with foreigners. In his discus-

sion of cannibalism, Arens has shown how the as-

signment of bestial practices to ones enemies or

even neighbors, to contrast their lack of culture with

ones own, is a nearly universal cultural practice,

especially when it also employs the usual dispar-

agement of the cannibal as sexually promiscuous.

55

Indeed, Herodotus combines incest with cannibal-

ism in his description of the Massagetae. It is there-

fore possible that Herodotus provided such a de-

tailed description of scalping in his Histories since

he was trying to dehumanize the Scythian tribes by

portraying them as violent and warfaring in nature.

Whereas it is possible that Herodotuss description

of cannibalism arose from a misunderstanding of a

funerary practice,

56

the cases of scalping from Ay-

myrlyg and Pazyryk are physical proof that the tribes

of the Scythian world did indeed practice scalping.

The four cases of Siberian scalping presented

here may not appear to reflect the apparent wide-

spread nature of this practice as described by Hero-

44

Mednikova 2000, 623.

45

Mednikova 2000, 634.

46

Anger and Diek 1978, 177.

47

Glob 1969, 93; Anger and Diek 1978, 1834.

48

Anger and Diek 1978, 1845.

49

Anger and Diek 1978, 185.

50

Fischer 1988, 3940.

51

Rolle 1989, 82.

52

Reese 1940, 7.

53

Slincourt and Burn 1972, 291.

54

Murphy and Mallory 2000; 2001, 16.

55

Arens 1979.

56

Murphy and Mallory 2000; 2001.

PREHISTORIC OLD WORLD SCALPING 9 2002]

dotus. This situation, however, may simply reflect

the approach of physical anthropologists working

on Russian material. With the exception of the cas-

es highlighted by Mednikova, the majority of Rus-

sian physical anthropologists have concentrated on

obtaining craniometrical and osteometrical infor-

mation from archaeological human remains, and

paleopathological analysis has only been undertak-

en by a small number of scientists. Indeed, the pa-

leopathological analysis on the human remains from

Aymyrlyg represents one of the few full studies of

this nature on a large cemetery population of Scyth-

ian period date.

57

It is quite probable that many

more cases of scalping will become apparent in the

remains of individuals from the Scythian period

when more of their skulls are carefully examined

for the characteristic pattern of cut marks.

The four cases of scalping evident among these

seminomadic pastoralists from south Siberia are

currently among the earliest definitive osteologi-

cal examples for this practice in the ancient world.

While confirming the accuracy of Herodotuss his-

torical account of scalping among the Eurasian

steppe nomads of the Scythian period, the osteoar-

chaeological information from Aymyrlyg has also

indicated that scalping continued into the suc-

ceeding Hunno-Sarmatian period of the Xiongnu.

Eileen Murphy

school of archaeology and palaeoecology

the queens university of belfast

belfast bt7 1nn

northern ireland

eileen.murphy@qub.ac.uk

Ilia Gokhman

department of physical anthropology

museum of anthropology and ethnography

(kunstkammer) russian academy of science

3 university embankment

st. petersburg 199034

russia

ilia.gokhman@pobox.spbu.ru

Yuri Chistov

department of physical anthropology

museum of anthropology and ethnography

(kunstkammer) russian academy of science

3 university embankment

st. petersburg 199034

russia

yuri.chistov@pobox.spbu.ru

Ludmila Barkova

department of archaeology

the state hermitage

34 dvortsovaya embankment

st. petersburg 193000

russia

ilia.gokhman@pobox.spbu.ru

Works Cited

Abetekov, A., and H. Yusupov. 1994. Ancient Iranian

Nomads in Western Central Asia. In History of Civili-

sations of Central Asia. Vol. II, The Development of Seden-

tary and Nomadic Civilisations: 700 BC to AD 250, edited

by J. Harmatta, 2333. Paris: UNESCO.

Allen, W.H., C.F. Merbs, and W.H. Birkby. 1985. Evi-

dence for Prehistoric Scalping at Nuvakwewtaqa

(Chavez Pass) and Grasshopper Ruin, Arizona. In

Health and Disease in the Prehistoric Southwest, edited by

C.F. Merbs and R.J. Miller, 2342. Arizona State Uni-

versity Anthropological Research Papers 34. Arizo-

na: Arizona State University Press.

Anger, S., and A. Diek. 1978. Skalpieren in Europa seit

dem Neolithikum bis um 1767 Nach Chr. - Eine Mate-

rialsammlung. Bonner Hefte zur Vorgeschichte 17:153

239.

Arens, W. 1979. The Man-Eating Myth: Anthropology and

Anthropophagy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Axtell, J., and W.C. Sturtevant. 1980. The Unkindest

Cut, or Who Invented Scalping? William and Mary

Quarterly 37:45172.

Burton, R.F. 1864. Notes on Scalping. Anthropological

Review 2:4952.

Clenova, N.L. 1994. On the Degree of Similarity be-

tween Material Culture Components within the Scyth-

ian World. In The Archaeology of the Steppes: Methods

and Strategies, edited by B. Genito, 499540. Naples:

Instituto Universitario Orientale.

Davidova, A.V. 1996. Ivolginskii Arkheologicheskii Kompleks:

Tom 2, Ivolginskii Mogilnik. St. Petersburg: Centre for

Oriental Studies.

During, E.M., and L. Nilsson. 1991. Mechanical Sur-

face Analysis of Bone: A Case Study of Cut Marks and

Enamel Hypoplasia on a Neolithic Cranium from

Sweden. American Journal of Physical Anthropology

84:11325.

Fischer, T. 1988. Rmer und Germanen an der Donau.

In Die Bajuwaren, Von Severin bis Tassilo 488788, edit-

ed by W. Bachran, T. Fischer, F. Koller, and R. Wil-

flinger, 3946. Bavaria: Hermann Dannheimer and

Heinz Dopsch.

Glob, P.V. 1969. The Bog People. England: Faber and

Faber.

Hamperl, H. 1967. The Osteological Consequences of

Scalping. In Diseases in Antiquity, edited by D. Broth-

well and A.T. Sandison, 6304. Springfield: Charles C.

Thomas.

Ishjamts, N. 1994. Nomads in Eastern Central Asia. In

History of Civilisations of Central Asia. Vol. II, The Devel-

opment of Sedentary and Nomadic Civilisations: 700 BC to

57

Murphy 1998.

10 EILEEN MURPHY ET AL., PREHISTORIC OLD WORLD SCALPING

AD 250, edited by J. Harmatta, 15169. Paris: UNESCO.

Larsen, C.S. 1997. Bioarchaeology: Interpreting Behaviour

from the Human Skeleton. Cambridge: Cambridge Uni-

versity Press.

Litvinsky, B.A., and Guang-da, Z. 1996. Historical Intro-

duction. In History of Civilisations of Central Asia. Vol.

III, The Crossroads of Civilisations: AD 250 to 750, edited

by B.A. Litvinsky, Z. Guang-da, and R. Shabani

Samghabadi, 1933. Paris: UNESCO.

Mandelshtam, A.M. 1983. Issledovaniye na mogilnom

polye Aymyrlyg: Nekotoriye itovi i perspektii. In

Drevniye Kulturi Euraziiskih Stepei, edited by V.M. Mas-

son, D.G. Savinov, and L.P. Khlobystin, 2533. Lenin-

grad: Nauka.

. 1992. Ranniye kochevniki Skifskova perioda na

territorii Tuvi. In Stepnaya Polosa Aziatskoi Chasti SSSR

v Skifo-Sarmatskoye Vremya, edited by M.G. Moshkova,

17896. Moscow: Nauka.

Mannai-Ool, M.H. 1970. Tuva v Skifskoye Vremya (Uyuk-

skaya Kultura). Moscow: Nauka.

Mednikova, M.B. 2000. Skalpirovaniye na Euraziiskom

Kontinentye. Rossiskaya Arkheologiya 10:5968.

Moskova, M.G. 1994. On the Nature of the Similarity

and Difference in the Nomadic Cultures of the Eur-

asian Steppes of the 1st Millennium BC. In The Ar-

chaeology of the Steppes: Methods and Strategies, edited by

B. Genito, 23141. Naples: Instituto Universitario

Orientale.

Murphy, E.M. 1998. An Osteological and Palaeopatho-

logical Study of the Scythian and Hunno-Sarmatian

Period Populations from the Cemetery Complex of

Aymyrlyg, Tuva, South Siberia. Ph.D. diss., Queens

University Belfast.

Murphy, E.M., and J.P. Mallory. 2000. Herodotus and

the Cannibals. Antiquity 74:38894.

. 2001. Herodotus and the Cannibals. Discov-

ering Archaeology 3:16.

Ortner, D.J., and C. Ribas. 1997. Bone Changes in a

Human Skull from the Early Bronze Site of Bab Edh-

Dhra, Jordan, Probably Resulting from Scalping.

Journal of Paleopathology 9:13742.

Owsley, D. 1994. Warfare in Coalescent Traditional

Populations of the Northern Plains. In Skeletal Biolo-

gy of the Great Plains: Migration, Warfare, Health and Sub-

sistence, edited by D.W. Owsley and R.L. Jantz, 33343.

Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press.

Phillips, E.D. 1965. The Royal Hordes: Nomad Peoples of the

Steppes. London: Thames and Hudson.

Reese, H.H. 1940. The History of Scalping and Its Clin-

ical Aspects. Yearbook of Neurology, Psychiatry and En-

docriminology:319.

Roberts, C., and K. Manchester. 1995. The Archaeology of

Disease. 2nd ed. Stroud: Alan Sutton.

Rolle, R. 1989. The World of the Scythians. London: B.T.

Batsford.

Rudenko, S.I. 1970. Frozen Tombs of Siberia: The Pazyryk

Burials of Iron Age Horsemen. London: J.M. Dent & Sons.

Slincourt, A. de, and A.R. Burn. 1972. Herodotus: The

Histories. Rev. ed. Middlesex: Penguin Books.

Stambulnik, E.U. 1983. Noviye Pamyatniki Gunno-Sar-

matskova Vremeni B Tyvye: Nekotoriye Itogi Rabot.

In Drevniye Kulturi Euraziiskih Stepei, edited by V.M.

Masson, D.G. Savinov, and L.P. Khlobystin, 3441.

Leningrad: Nauka.

Vainshtein, S.I. 1980. Nomads of South Siberia: The Pastoral

Economies of Tuva. Cambridge: Cambridge University

Press.

Vernadsky, G. 1943. Ancient Russia. London: Oxford

University Press.

Zadneprovskiy, Y.A. 1994. The Nomads of Northern

Central Asia after the Invasion of Alexander. In His-

tory of Civilisations of Central Asia. Vol. II, The Develop-

ment of Sedentary and Nomadic Civilisations: 700 BC to

AD 250, edited by J. Harmatta, 45772. Paris: UNESCO.

American Journal of Archaeology 106 (2002) 1135

11

The Ancient Temple on the Acropolis at Athens

GLORIA FERRARI

Abstract

This article concerns the Archaic temple of Athena

that was set on fire in the Persian sack of Athens and its

function in the monumental reconstruction of the

Acropolis under Pericles. A new analysis of archaeologi-

cal, epigraphical, and historical sources leads to the con-

clusion that the temple was neither destroyed in the

assault nor taken down at a later date, but that, as Drpfeld

argued, it remained standing until well into the Roman

period. Further, it is argued that the old temple was the

core of an extensive choreography of ruins that is the

background against which the new Periclean buildings

acquire their meaning.*

It is in that golden stain of time, that we are to look

for the real light, and colour, and preciousness of

architecture; and it is not until a building has assumed

this character, till it has been entrusted with the fame,

and hallowed by the deeds of men, till its walls have

been witnesses of suffering, and its pillars rise out of

the shadows of death, that its existence, more lasting

as it is than that of the natural objects of the world

around it, can be gifted with even so much as these

possess of language and of life.

1

The discovery of the archaic temple of Athena

on the vast empty terrace at the center of the Acrop-

olis came as a surprise.

2

In 1885 Wilhelm Drpfeld

recognized in the structure at the northeastern end

of the terrace, whose massive retaining wall runs

under the Porch of the Maidens of the Erechtheum,

a large poros temple. What remained after the work

of clearing the area, which had begun in earnest

with Ross in 1834, was completed by Kavvadias in

1886,

3

were its foundations, preserved, in one point,

to the level of the stylobate (fig. 1). Apparently, no

building ever had encroached on the place of the

temple in antiquity, except for the Porch of the

Maidens, perched on the north foundation of its

peristyle (fig. 2). Drpfeld immediately recognized

in the great Doric building the temple of Athena

Polias, which had stood on the Acropolis at the time

of the Persian invasion and sack of Athens in 480

B.C.E., and identified it with the arkhaios naos men-

tioned in literary and epigraphical sources.

4

There

finally was an answer to the question of the origin of

pieces of entablature built into the north wall of

the citadel, in correspondence to the foundations:

this was the temple to which they had once be-

longed.

5

But the discovery also played havoc with

the understanding of the sacred topography of the

Acropolis that was current, as enshrined in Jahn

and Michaelis, Arx Athenarum.

6

On the basis of Stra-

bo (9.16), who mentions only two temples on the

Acropolis, it had long been assumed that those two

were the Parthenon and the Erechtheum and that

the latter was the reconstruction of the archaic tem-

ple of Athena Polias, which the Persians had de-

stroyed.

7

One had to reckon now with the fact that

the archaic temple was not rebuiltnot on the same

*

I thank T. Jenkins for calling my attention to the Ruskin

passage and for much assistance besides in both technical and

scholarly matters. A. Cohen, P.E. Easterling, M. Flower, A.

Hollman, M. Jameson, N. Luraghi, G. Nagy, and J.C. Wright

contributed valuable suggestions and corrected mistakes. I am

especially grateful to my colleagues at the University of Chica-

go, T. Cummins, L.M. Slatkin, and Wu Hung, for insights into

the relationship of monuments to social memory. My greatest

debt is to D.H. Sanders, who brought to the project exacting

standards, immense patience, and commitment.

1

Ruskin 1849, 172.

2

That the area occupied by the temple was the site of a struc-

ture, however, had been seen before. In Michaelis (1871, pl.

1) its perimeter is drawn in outline and tentatively identified

as that of the Cecropium; see Korres 1996, 78. Burnouf (1877,

1634, pl. XII) describes the structure as a terrace in blocks of

Acropolis limestone: Lautre moiti est remblaye jusq la

base de lrechthum au moyen dun pav (18) compos de

plusieurs assises de blocs polygonaux superposs. [. . .] Les

blocs dont se compose le pav proviennent du rocher mme

de lAcropole et ont d tre obtenues quand on a form les

diverses esplanades consacres Minerve ou Diane. A ouest

de lrechthum, ce pav se termine par un mur de vingt-qua-

tre mtres de longueur, dont langle sest croul et qui se

continue en retour dans la direction de langle occidental du

Parthnon. According to Harrison (Harrison and Verrall 1980,

496) Btticher discovered this pavement in 1862. I thank M.

Jameson for this reference.

3

On the work of clearing the Acropolis of post-ancient struc-

tures, see Mallouchou-Tufano 1994. For earlier records of Athe-

nian monuments, see Korres 1998.

4

Drpfeld 1885, 275; 1886a; 1886c; Kavvadias and Kawerau

1906, col. 32.

5

On the discoveries and the debate over the assignment of

architectural members in poros found on the Acropolis to the

Old Temple of Athena and the archaic predecessor of the

Parthenon, see Korres 1997, 21825.

6

Jahn and Michaelis 1880.

7

See the comments in Dinsmoor 1942, 185. As Jeppesen

(1987, 1112) observes, the communis opinio, which prevails to

this day, was founded as early as 1676 by Jacob Spon.

GLORIA FERRARI 12 [AJA 106

site, which, moreover, was left untouched by the

comprehensive reconstruction undertaken by Per-

icles. This was clearly a case such as the one Dins-

moor envisioned, where archaeology turns up a

piece of the past that does not fit neatly within the

given current historical reconstruction:

8

The archaeologist, engaged primarily in the study and

interpretation of the material products rather than

the verbal records of mans past, that is, the illustra-

tions of the written text rather than the text itself, the

monuments rather than the documents, often finds

that he is in the enviable position of dealing with the

unbiased evidence of contemporary witnessespro-

vided that he can interpret itas contrasted with the

textual tradition which is so often retrospective and

sometimes mistaken or willfully prejudiced. Yet illus-

trations and text form an inseparable whole; the one

must fit the other; and the arbitration of differences

is often delicate.

In the figure of the unbiased contemporary wit-

ness, Dinsmoor evoked the old hope of the anti-

quarian that the truth about the past lies precisely

in its tangible, unprocessed remains. In the event,

the case of the Drpfeld temple, as some call it still,

demonstrated instead the tenacity of established

constructs and their ability to resist intrusions that

would threaten their very foundation. Drpfeld took

his discovery to show that the archaic temple was

repaired in the years immediately following the

Persian sack and that it remained standing, al-

though without its peristyle, to the end of antiquity

and beyond.

9

His proposal found few, if distin-

guished, supporters.

10

Frazer and Michaelis stood

by the old explanation, arguing that the Drpfeld

temple was not the ancient temple of Athena Po-

lias but a new temple with respect to the arkhaios

naos, which lay still under the Erechtheum.

11

These

attempts to reestablish the orthodox view of the

matter were soon dismissed but, already in 1901,

Bates had offered an interpretation that accommo-

dated the new discovery and required only minor

Fig. 1. Plan of the arkhaios naos by W. Drpfeld. (After Wiegand 1904, fig. 117)

8

Dinsmoor 1942, 185.

9

Drpfeld 1887a; 1887b; 1890; 1897. Drpfelds final for-

mulation of the hypothesis of the survival of the temple is

briefly stated at the end of his 1919 article, p. 39: the Peri-

clean plan for a total reconstruction of the archaic temple and

adjacent buildings and shrines only got as far as the Erech-

theum; in actuality the temple was retained and repaired after

the fire in 406 (for which see infra, n. 26).

10

Harrison and Verrall 1890, 5029; Cooley 1899; F. Dm-

mler, RE II s.v. Athena, col. 1952; Schrader 1939, 3956.

11

Frazer 18921893, 16774; Michaelis 1902, 111.

THE ANCIENT TEMPLE ON THE ACROPOLIS AT ATHENS 13 2002]

adjustments to the traditional account.

12

The Drp-

feld temple was the temple of Athena Polias burned

by the Persians. This burned temple, he argued,

was never rebuilt, in keeping with the oath the al-

lied Greek forces took on the eve of the decisive

battle at Plataea, when they pledged never to re-

build the shrines of the gods destroyed by the bar-

barians.

13

Bates connected the provisions of the oath

to the fact that, after 479, some of the destroyed

temples were left in ruins for a generation and re-

built after 450. He found the explanation for this

state of affairs in the so-called Congress Decree,

mentioned in Plutarchs Life of Pericles (17.13). As

the Spartans grew wary of the growing power of Ath-

ens, Pericles introduced a bill to convene the Hel-

lenic states that had fought the Persians to a con-

gress in Athens. Its agenda would be to discuss what

to do about the sanctuaries that had been burned

by the barbarians, the sacrifices that had been vowed

to the gods in the course of the struggle, and the

peace among the Greek states and safe navigation.

It was his intention, according to Bates, to persuade

the allies to revoke the oath because the Acropolis

with its burnt ruins had come to be an eye-sore to

the Athenians, and Pericles desired to clear the

ground and build a new temple. When the initia-

tive failed, Pericles unilaterally took the decision

to rescind the part of the Oath of Plataea that con-

cerned the temples: at Athens the Acropolis was

cleared of its ruins and the Parthenon begun.

14

Batess reconstruction of events left substantially

intact the understanding of the history of the Acrop-

olis that existed before the discovery of the Drp-

feld temple. As before, the Erechtheum could be

seen to be the successor of the ancient temple of

the Polias, in name as well as in fact, and the place

where the ancient temple had stood continued to

be viewed as an empty terrace of no particular in-

terest. Thus by 1942the date of Dinsmoors sweep-

ing reconstruction of the historical topography of

the Acropolisthe waters had closed over Drp-

felds discovery. The questions it had raised remain

unanswered. Why, given the spirit of grandeur that

informed the Periclean rebuilding of the Acropo-

lis, was the principal cult of the city served by such

a small edifice, less than half the size of the archaic

12

Bates 1901.

13

Lycurg. Leoc. 81; Diodorus 11.29.3; cf. Isoc. Paneg. 4.156.

14

Bates 1901, 322, 326.

Fig. 2. Early 20th-century aerial view of the foundations from the south. (Courtesy of the Fine Arts Library, Harvard

College Library)

GLORIA FERRARI 14 [AJA 106

temple and lacking a peristyle, as well as pedimen-

tal sculptures? Why was the temple not rebuilt on

its original location, as customary? And why was the

terrace on which it had stood left unencumbered

by new construction? I wish to return here to the

most vital part of Batess argument, one that he sup-

pressed in the end, namely, that the ancient tem-

ple of Athena Polias was never rebuilt indicates

compliance with the Oath of Plataea. If the fact that

the site of the ruin was left untouched is given

appropriate emphasis, instead of being swept aside,

a different explanation of the Periclean architec-

tural plan and of the events surrounding it becomes

possible. The thesis of this article is that after the

Persian sack the temple was left standing and made

into a monument to barbarian sacrilege and Athe-

nian righteousness. Far from being unsightly rub-

ble, the ruin at the heart of the Acropolis func-

tioned as the point of relay to which the other build-

ings responded. The argument moves from a dis-

cussion of the Oath of Plataea to consider literary

and archaeological evidence for the existence of

the war memorial.

The debate over the authenticity of the Oath

began in antiquity. In the fourth century B.C.E.

Theopompus of Chios, who was no friend of the

Athenians, denounced it as a sham, of a piece with

other Athenian claims, such as the Peace with the

Mede, the decisive role of Athens at Marathon, and

other impostures the city of the Athenians perpe-

trates and fools the Hellenes.

15

Indeed, a recita-

tion of ancestral glories, with a pronounced anti-

Peloponnesian flavor, is the context in which we

encounter the Oath of Plataea for the first time, in

Lycurguss prosecution of Leocrates for treason

(81).

16

The relevant section of the speech opens

with a reference to the attempt to withdraw the

night before the battle of Salamis by the Spartan,

Corinthian, and Aeginetan commanders (70).

Alone among the Hellenes, the Athenians forced

them to stay and fight, and prevail upon the barbar-

ians. The heroic sacrifice of Codrus for the city, in

the face of the first Peloponnesian invasion of Atti-

ca ever, is later recounted at length (8487). As

much as these stories, the Oath of Plataea lent it-

self to a self-aggrandizing, boastful discourse about

the Athenian past, and that is all that may be said

with confidence about it. But, in order to be effec-

tive, the Oath had to appear to be true. Its power to

bear witness to the piety and courage of those men

of old is stressed in the phrase, which in Lycurguss

speech follows its recitation (82): They stood by

this oath so firmly, fellow men, that they had the

favor of the gods on their side to help them; and,

though all the Hellenes proved courageous in the

face of danger, your city won the most renown. The

rhetorical force of this statement depends upon its

being common knowledge that, in the event, the

Athenians did what they said they would do: fol-

lowed leaders, buried dead comrades, punished

collaborators, and made war memorials of the

burned shrines. For this reason Lycurguss state-

ment is hard to reconcile with the current view that

the Acropolis was cleared of the debris of the Per-

sian destruction and the Oath of Plataea essential-

ly discarded. How could he say so boldly that the

ancestors had stood firmly by the oath, when it

would be so very apparent to anyone looking in the

direction of the Acropolis, the Parthenon towering

over it, that it was not so. How could the Oath of

Plataea play a role in the fourth century construc-

tion of the geste of Athens, unless the scarred walls

of the ancient temple of the Polias were there to

bear out the truth of the claim?

Most scholars of the Acropolis now would agree

that the ruin was part of the Acropolis landscape

for some time, if only as part of a temporary, make-

shift arrangement. Fifth- and fourth-century sourc-

es mention a structure called tout court Opisthodomos,

which housed the treasuries of Athena and of the

Other Gods.

17

The word normally signifies the rear

chamber of a temple, but this structure is called an

oikos, an oikema, and part of the Acropolis, as though

it were detached.

18

A decree dated around 420

B.C.E., which contains the provision that a column

be erected behind (or south of) the Opisthodomos,

15

FGrH 115 F 153. Connor (1968, 7881) pointed out that

the wording of the fragment does not justify the widespread

notion that Theopompus made an outright denial of the oath

and the peace. He further notes (88) that the Oath, the peace

with Persia, and Marathon each plays an important role in

Athenian panegyric and propaganda in the fourth century.

The debate continues in modern time, with scholars firmly

positioned on one side or the other, but those who believe in

the oaths historicity seem now to have the upper hand, after

Siewerts monograph on the subject. Siewert (1972, 1028),

however, argues that the promise to make memorials of the

burnt shrines was not part of the original oath, because that

clause is omitted in the Acharnae inscription and some tem-

ples were rebuilt immediately after the battle of Plataea.

16

Michael Flower points out to me that Diod. Sic. 11.29

indirectly may preserve the earliest surviving version of the

oath, which he drew from Ephorus of Cyme, although Styl-

ianou (1998, 4950, 11012) concludes that the publication

of Ephoruss history is contemporary or slightly later than Ly-

curguss speech, falling in the late 330s and the 320s.

17

Harris 1995, pt. II.

18

olo: Harpocration s.v. ooo; scholia to Demos-

thenes 13.14. o: Demosthenes 24.136, with scholia.

o do: Suidas, s.v. ooo.

THE ANCIENT TEMPLE ON THE ACROPOLIS AT ATHENS 15 2002]

seems to confirm that this Opisthodomos was a free-

standing building.

19

The solution to the puzzle of

how an independent structure might be called rear

chamber was proposed first by Ernst Curtius and is

still in favor: this was the western part of the archaic

temple of Athena, the one discovered by Kavvadias

and Drpfeld. After the Persian sack, only the

opisthodomos of the temple was repaired and con-

tinued to serve as treasury, retaining its old name.

20

Scholiasts and lexicographers tell us that the

opisthodomos was located precisely where one

would expect it to be if, indeed, it was once the rear

chamber of the temple of Athena Polias: behind

the temple of the Athena called Polias.

21

On the

unwarranted assumption that the cella of the ar-

chaic temple had been razed by the Persians or

torn down soon after the sack, the temple of Athe-

na mentioned in reference to the Opisthodomos

was identified in the Erechtheum. From no signif-

icant viewpoint on the Acropolis, however, this

Opisthodomos would appear to be behind the Ere-

chtheum and, in effect, anyone looking for it there

would find himself in the Pandroseum.

22

If the Cur-

tius hypothesis is correct, the temple in question

should be the eastern half of the Drpfeld temple,

the cella that housed the ancient image.

While there is no evidence that the archaic tem-

ple was ever taken down, there is some to the con-

trary. The temple of Athena Polias is last men-

tioned by Pausanias (1.27.1) in the second century

after Christ. Before him, Strabo had stated that there

were on the Acropolis the ancient temple of the

Polias, in which is the lamp that is never extin-

guished, and the Parthenon made by Ictinus, in

which is the Athena, the work of Pheidias in ivo-

ry.

23

Strabo may be using the expression ancient

temple, arkhaios naos, in a purely descriptive and

generic sense. In that case he draws a distinction

between an old and venerable structure (which,

therefore, cannot be the Erechtheum) and the Clas-

sical Parthenon. Or arkhaios naos has here a con-

ventional, nondescriptive meaning and functions

as the name of a particular building (which, in this

case, may be the Erechtheum). But the label

arkhaios naos to designate the temple of Athena

Polias occurs in sources concerning events that

range from the late sixth century to Hellenistic

times.

24

The earliest mention occurs in reference

to Cleomenes attempt to seize the Acropolis in

507/6 B.C.E. The penalties inflicted upon his Athe-

nian supporters were inscribed on a bronze stele

set up next to the arkhaios naos (Schol. Ar. Lys.

273). The most important testimony is given by the

decree of the Praxiergidae, containing the provi-

sion that a stele be set up behind the ancient tem-

ple.

25

This inscription dates to the years 460450,

that is, to the time intervening between the Persian

sack and the Periclean reconstruction, 30 years or

more before construction of the Erechtheum be-

gan. What might be called arkhaios naos on the

Acropolis at this time, except the temple of Athena

Polias in which the last defenders of the city had

taken refuge? And the old temple of Athena, the

palaios neos, which was set on fire in 406 B.C.E., can

hardly be any other.

26

The literary and epigraphical testimonia coher-

ently support Drpfelds contention that the archaic

temple continued to exist into late antiquity. If the

Opisthodomos continued to stand as a separate

structure, it is not only possible but likely that the

19

The earliest mention of the Opisthodomos occurs in a

decree dated 440420 B.C.E.,

IG 1

3

.207.1415: |o

: | o|| o ooo. In

AristophanesPlutus (119193) there is talk of restoring Plutus

to his old residence, always standing guard over the

opisthodomos of the goddess. The latest reference to the build-

ing is in a speech of Demosthenes of 353/2 (24, 136). Most of

the literary and epigraphical testimonia are collected and dis-

cussed by White 1895. See also Harris 1995, 401.

20