Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Porter 1990 The Competitive Advantages of Natios 194770

Enviado por

Less GallardoDescrição original:

Título original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Porter 1990 The Competitive Advantages of Natios 194770

Enviado por

Less GallardoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

-

~

/f _

- ' . ~

. . ~::.

.. The Compet i t i ve Advant age

of Nat i ons

\

,

,

Michae) E. Porter

,

,

\ ' ~ H arvard B usiness R eview

90211

"

,

,

\

-~~~.-----

MARCH:tAPRlL 1990

The Compet i t i ve Advant age of Nat i ons

Michael E.Porter

\

\.

National prospcrity i8crcated, not inherited. It does

not growout of acountry's natural endowments, its

labor pool, its interest rates, or its currency's value,

ascla8sical economics msists.

Anation'scompetitiveness depcndsonthc capacity

of 1tsindustry to innovate andupgrade_Compames

gainadvantagc against the world's best competitors

because ofpressure andchaHenge.TheyheneHt from

havingstrongdomestic tivals,aggressivehome-based

suppliers, anddemanding local customcrs.

In aworld of increasingly global competition, na-

tions havebecome more, not less, important. Asthe

basis of competition has shifted more and more to

the creation andassimilation of knowledge, the role

of the O3tionhas grown.Competitive advantage is

createdandsustained tbrough ahighlylocalizcdpro-

cess_ Differences in national values, culture, eco~

nomic structures, institutions, and histories aIl

contribute tocompetitive success.Tbere arestriking

differences in the pattems of competitiveness in

cvery country no nation canor will becompetitive

ineveryor evenmost industries.lntimately, nations

succeed inparticular industries because their home

enYronment isthe most forward-Iooking, dynamic,

andchallenging.

Theseconclusions, thc product ofafour-year study

HUNard BU.~inessSchooI professm Mchn.eI E. Porter s the /lUthar

af Competitive StIategy (Free Press. 1980) and Competitive Arl-

vantage(Free PrtlSs. 1985)und will publish lbe Competitive Arl.

vantageof Nations (Fre)Press} in May 1990.

Aut1lOr's note: Michae1. Enright, who served as pro;ect coordI1fl-

tar tm ths study, has contributed vallluble .<mggesrions.

of the patlems of competitive success inten leading

tradingnations, contradlct theconventional wisdom

that guides the thinking o many companics andna-

tional governments-and that is pervasivc today in

the United States.(Formoreabout the study, seethe

insert "Pattems o National Competitivc Success.")

According to prevailing thinking. labor costs, inter-

est rates, exchange rates, andeconomies of scaleare

the most potent detenninants of competitivencss. In

companies, thewordsof thedayaremerger, alliance,

strategic partnerships, collaboration, and suprana-

tional globalization. Managers arepressing for more

govemment support forparticular industries.Among

govcrnments, thcrc is agrowingtendency to experi-

ment with vanous pollcies intended to promote na.

tional competitiveness-from efforts to manage

cxchange rates to newmeasures to manage trade to

pollcies to relax antitrust-which usually end up

only undermining it. (Seethe insert "What Is Na-

rional Compctitiveness?"l

Thesc approaches, now much in favor in both

companics andgovernments, areflawed.Theyfunda-

mentally misperceive the truc sourees of competi-

tive advantage.Pursuing them, with aHtheir short-

termappeal, 'will virtually guarantee that theUnited

States-or any other advanced nation-never

achievesreal andsustainable competitive advantage.

Weneedanewperspecrive andnewtools-an ap-

proach to competitiveness that growsdirectly out of

3D analysis of intemationally successful indlL.<;tries,

without regardfDI traditional ideologyor current in-

tellectual fashion. We need to know, very simply,

what works andwhy.Then we need to applyit.

Copyright o 1990by the President and FeUowso HarvardColJege.All rights reserved.

,

Patterns of National Competitive Success

To invl"$ugate why nations gnin compctitivc advan.

tagc in panicular induStries and the implications lar

comp.any stratcgy and O1ltional tt:onomies, I condueted

four-yar lttudy of ten imporunt trading natiaos: Den-

mark, Cerrosn)', Italy, lapao, Korca, Singaporc, Swedcn,

Switurland, the United Kingdoffi, and the United

States.1 wasassistcd by8tcamof morethan 30research-

Cl'B, mast 01 whnm were natives of and bascd in !he

nation they studicd. The resc.archcrs all used the samc

rncthodology.

Thrc:c nation&-thc United Sute:'!, 'apan, and (;tt.

many-llte thc world's lcading industrial poweOl. The

othCf nations represent a variety o population tiius,

govemment policics toward induSU)', social philoso-

phie.", ;eographical sizcs, and 100000tiona. Togcther, the

ten natinos acoounted orfully 50% of total world ot-

J 'Ons in 1985. thc MSCyear 1m slatistical 8nt1lysis.

MOStprevious .llnlllyseso nalional competitiveness

hltvefocused on single nation or bilateral comparisons.

Bystudying nations with widcly varying ch.a.raeteristics

and circumstanccs, thi5 lrtudy sought to separate tbe

fundamenul forces uoderlying nationa1 competitive Id.

vanugc fromthe idiosynetatic oncs.

Ineaeh nation, thc study consistcd of twOpart!!. The

first identHied all industries inwhich the na.tinn'scom-

panics wcre intcrn.ationally succcssful, using availahle

statistical data, supplc:mentary published sources, and

ficldintervicws. Wedcfincd anation's industry as inter-

nilltionllJ lysucccssful if itpossessed compelitiv~ advan-

lage relaliv~ lo tbe best wo[ldwid~ campeLiroIS. Many

mcasures of competitive advantagc, 5uch as rcportcd

profitability, can be misleading. We Ch05Cas thc best

indicatol'll the presente of subsuntial and 5ustained 0-

ports tO.l widt array of other nations and/or significant

outbound forcign invcstment based on llhlls and assets

cn:lIItcdin the homc COUntry.A n:ltion was considen:d

the home base far ocompany if it WlIScither o locally

owncd, indigcnou5 cntcrprisc or managcd autooo-

mousl)' although owncd byaforeign rompan)' or invest.

Ots. Wc thcn creatcd a profiJ e of all the industries in

which cach nation was intemationally 5uccessful at

three points in time: 1971, ]978, and 1985. Thepattern

of camtetitive industries ineach economy WIIS far &om

random: the tllsk was lo cxpIain it and how it hlld

changcd over time. Of particulu intcrest wcrc the con-

ncelians ar relationships among tbe nation's competi-

tive industries.

In the second part of the study, we cxnmincd the

history of competition inparticular industries tounder-

stand hnw competitive advanugc WllScrcated. On the

basis of nationaI profiles, we KI~cd over 100 indu.'l-

tries or industry groups lor detailcd studyJ weexamincd

many more in less dcuiJ . Wewent back as far4Sneces.

Uf)' to undcrsund how a.ndwhy the industry bcgan in

the nation, how it grew, whcn and why rompanic.~from

the nlltion dcvcIopcd intcrnational competitive advan-

tage, lInd the pr0ecs5 by which rompctitive advanuge

had bcen cither sustllined or Inst. The resulting case

histories faJ l shon o the work of a good historian in

thcir levc:l 01 detail, hut they do provide insight into

the dcvclopment of both the industry and the nation's

economy.

Wcchose asample of industries for cach nation that

represcntcd thc most important groups of competitivc

industries in the ecnnomy. The industries studied se-

counted for olargeShllrcof total exports incaeh nation:

more tblln 20%of total export!! in 'apan, Germllny, and

SwittcrLmd, for cx.arnple, and more than 40% inSouth

Rorea. We studicd some of the mast faffious and

imponant intcrnationsl SUCCC5S storics-Ccnnlln high-

pcrlonnancc autos and chcmicals, ,apanese serni-cnn-

ductors and VeRs, Swiss banking and pharmaccuticals,

Italian footwCllr and textiles, U.s. commcrcialairersft

and motion pietures-and sorne rclativcly obseure but

highly competitive ndwrtriC5-South Rarean pianos,

ltalian ski boots, and 8ritish hiscuits. We.11150 added a

kw industries bccause they Ilppcan:d tObeparlldoxes;

'apancse home demand far Weste:rn-charaetcr typcwrit-

en;isncarly nonexistent, for cxample, hut 'apan holds

8strong cxport IIndforcign investment position in the

indusU)'. Weavoidcd industries that wcrc highly depen-

dent on natural rc:sourccs: such industries do not forrn

thc backhonc of adv.anced cconomics, and the capllcity

to compete in them is more explicable using cillssical

thcory. We did, howcvcr, indude a nnmber of more

tcchnologically intcnsive, nlltural.rcsource-rclatcd in.

dustries such as newsprint llnd agricultural chc:micals.

The sample of nations and industries nfcn;a rieh

cmpiric:al foundation for devclopingand testing thenew

thcory of how rountnes gain rompctitive advantage.

The accompanying anide conccntratcs onthe dctenni.

nants of competitive advantagc inindividual industries

nndalso sketehcs out sorne of the study's overaIl impli-

cation! for gove:rnment poliey 8nd company strategy. A

fuJ ler treatment in my book, 71J ~Competitiv~ Advan-

tag~ 01 Nations, devclops the thcory and its impliCtl-

tion! in grcater depth snd provides many additional

examples. It aIso rontains dctailed descriptions of thc

na.tion! we studicd and the fnture prospccts for thcir

cconomics.

-Miehacl E. 'Poner

74

HARVARD BUSINESS RIMEW Msrch-April 1990

"

How Companies Succeed in

International Markets

Around the world, companies tbat have achieved

internationalleadership employ strategies that diffcr

froro each other in cvery respectoBut while evcry

successful company will employ its OWD particular

stratcgy, the underlying marle o operation-the

character and trajectory of a11succcssful compa-

nies--is fundamental1y the saroc.

Companies achicvc competitive advantage

through acts of innovatioo. They approach innova-

tion in its broadest serrse, including both new

technologies and new ways of doing things. They

perceive a new basis foy competing or fiud hetter

meaos for competing in oIdways. Innovaton can be

manifested in anewproduct design, anew produc*

tion process, anew marketing approach, or anew

way of conducting training. Much innovatan is

mundane andincremental, depenmng more 00acu~

mulation of small insights and advances than on a

single, major technological breakthrough. 1t oftcn

involvcs ideas that arenot evcn "new"~ideas tmt

have been around, but nevet vigotously pursued. It

always involves investments inskill andknowledge,

aswell asinphysical assets and brand reputations.

Sorneinnovations cteate competitiveadvantage by

petceiving anentirely newmarket opportunity orby

serving amarkct scgment that others have ignored.

Whencompctitors areslowtorespond, suchinnova-

tion yields compctitive advantage. For instance, in

industries such asautos andhome electronics, Tapa-

nesecompanies gainedtherr initial advantagc bycm-

phasizing smaller, more compact, lower capacity

models that forcign competitors disdained as less

profitable, lcss important, andless attraetive.

In intemational markcts, innovations that yield

competitive advaotage anticipate both domestic and

forcignneeds. For example, asintemational concern

for product safety has grown, Swcdish companies

like Volvo, Atlas Copco, and AGA have suceeeded

by aotieipating themarket opportunity in this area.

Onthe other hand, innovations that rcspond tocon-

cernsor crrcumstances that arepeculiar totbeborne

market canactually rctardinternational competitive

success. Thelureof thehugeU.S. defensemarket, for

instance, hasdiverted thc attention of U.S. materials

andmachine-tool companies romattractivc, global

commercial markets.

Information plays a large tole in thc process of

innovation and imptovement-informatioll that ei-

thet is not available to competitors or that tbey do

not seek. Sometimes it comes fromsimple invest-

ment in research and development or market re-

search more often, it comes romeffort and rom

openness and fromlooking inthe right place unen-

HARVARDBUSINESS REVIEW Marcn-Aprill990

cumbered by blinding assumptions or conventional

wisdom_

This iswhy innovators areoften outsidcrs froma

difierent industry or adifferent country. lnnovation

may comeromanewcompany, whose founder has

anontraditional background or was simply not ap-

preciated in an older, established company. Or the

capacity for innovation may come into ao existing

company through senior managers who arencw to

the particular industry and thus more able to per-

ceiveopportunities andmore likely topursue thero.

Or innovation may occur as acompany diversifics,

bringing newresources, skiIls, or perspectives to an-

other industry. Or innovations may come from

another nation with different circumstances or dif-

ferent ways of competing.

With fewexceptions, innovation is the tesuIt of

unusual effort. The company that successfully im-

plcments anewor better way of competing pursues

its approach with doggeddetermination, aftcn inthe

faeeof harsh criticism and tough obstacles. Infact,

tosucceerl, innovation usually requires prcssurc, oe-

cessity, and even adversity: the fear of loss oftcn

proves morc powerful than the hopeof gaio.

Once acompany achieves competitive advantage

through aninnovation, it cansustain it ooly through

relentless improvement. Almost any advantage

can be imitaterl. Korean companies have already

matched the ability of their Japaneserivals to mass-

producestandard color televisions andVCRsBrazil-

ian companies havc assembled technology and

designs comparable to Italian competitors in casual

leather footwear.

Competitors wiIl eventually and inevitably over-

takeanycompany that stopsimproving andinnovat-

ing. Sometimes early-mover advantages such as

customer relationships, scale economies inexisting

technologics, or the loyalty of distributioo channels

ate cnough to permit astagnant company to retain

its entrenched position foryearsorevendecades. But

sooner or later, more dynamic rivals will findaway

toinnovate around these advantages or create abet-

ter or cheaper way of doingthings. Italian appliance

producers, which competed successfully 00thebasis

of cost in selling midsize and compact appliances

through largeretail chains, restcd too long 00this

initial advantage. Bydeveloping more differentiated

products and creating strong brand franchises, Ger-

man competitors have begun to gaio gronnd.

Ultimately, theooly way to sustain acompetitive

advantageistoupgradeit~tomovetomore sophisti-

cated types. This is precisely what Tapancscauto-

makers have done. They initiaIly peoetrated foreigo

markets with small, inexpensivc compact carsof ad.

equatc quality and competed 00the basis of lower

labor costs. Even while their labor-cost advantage

pcrsisted, however, theJapanesecompanies wereup-

75

'.

What 15National Competitivene55?

National competitivcncss has bccome ane o the cen.

mI preoecupnions of govemment and industry incvcry

mltion. Yet fm11I1l tbe discusson, debJ Ite, snd writing

onmetapie, then: isStill nopcrsuasivc thcory toexplsin

nalinnal competitiveness. What 5mnre, there is 001

cven aa Bccqltcd ddlnition of the terro "compctirive-

nes!!" asapplied t08I1J Ition.While the notan of acomo

petitivc company is cleRt, thc notan of 8competitivc

oation is noto

Sorne see naton.1 compctitivcnC!l~ as a maeroeco-

nomic phenomenon, drivc::nby variables such as ex-

changc rates, interest r.;atcs,4tId government ddicits.

Rut llpan, luly, aad Soutb Rarea havc .11 e.n.foyedrapo

idly rising living 8tandards <k-lpitc hudgct dcficits Cer.

mllay and Switurland de!pitc apprttiating currencics

IIndItaly aad Korea dcspite high nterest rates.

Othcrs arguc tbat comprtitivcncss is 8 function of

cheap liad ahund:mt lahor. But Germany, Switurland,

and Swedcn have all prospered even with high WlIgcs

and labor shoJ UgCS. &sirles, shouldn't 8 nation seek

higbcr wages for its worlu::rs l1ISa goal of competitive-

n c s s !

Another view connect.c;compctitiveness with bounti.

fui naturnl ttSOurttS. But how, then, can one explain

the 5UCCl$Sof Ccnnl1lny, lapan, Switzerland, ltaly, lInd

South Korea-countries with J imited ruaturnl resourec:sr

More recently, tbe argument has gained favor that

c.ompetitiveness is driven by govemment poliey: tu-

geting, protection, import promotion, and ,ubsidies

have propclled J apanese aod South Rarean auto, stecl,

!lhipbuilding, and semiconduCtor industries iota global

prc:cminence. Hut a closer look revcals. spotty -record.

loItaly,govemment intervention hasbeen ineffectual-

but 118lyhas c::xperiencedaboomio world export share

sttond only tOJ aptlD. lo Germany. dim:t government

intervcntion io exponing industries is rnre. And even

in J apan and South Rorea, govcmment's role in such

important industries as faesimile machines, copiers, f'O.

botics, and advanecd matctials h,ssbecn modest 5OTT1e

of the mmt frequentJ y cited examples, sueh .s sew:ing

maehines, stccl, and shiphuilding. atenow quite dated.

A final popular cxp!l1Inarionfar nlltion,,1compctitivc-

ness is diffttttl.~ in management prnetiees, including

maoagement-Iabor rclations. The problem hete, how.

cver, is that diffen:nt industries rcquire:: diffcrent ap-

proaehes tOmanagemcnt. The sueecssful management

prnetiees goveming !mIall, private, and looscly Org!-

nized Itnlian family comp.llni~ in footwcar, textiles,

and jewelry, for CXlImple,would produce s managcment

disaster if applied to Cenosn chemical or auto rompa-

nies, Swiss phannaeeutical makers, or American airo

erah producers. Nor is it possible to genernIize about

managcment-Iabor rdations. Despite the eommonly

held view that powerful unions undermine competitive

advllntage, unions arestrong inCermany and Sweden-

llnd both rountnes boast intemationally pra:minent

companies.

Clearly, none of the..-lecxplamtions is fully satisfae.

tory none is sufficient by ltsclf to I'lltionalizc the com-

pctitive position of industries within anationa! border.

Eachconuins sorne truth but IIbreader, more complex

set of forces seem:'l to he .litwork.

11Iebek of IIclcar explamtion signals an even more::

fundamenu.1 qutstion. What is aHoompetitive" nation

in the first placer Is a"competitive" nlltion one where

every eompany or indu~try is competitive1 No nation

mectS this test. Even'apan has I.rge sector.'! o it.'lecon-

omy th.at fan far behind the world's he:lt competitors.

b a "competitive" nation one whose exehange rate

makes its goods pria: competitive inintemational mar-

km1 80th Gennany liadJ ap.onIuve enjoyed remarkable

gains in thcir SUlndardso living-and experieneed sus-

tained period.'1of strong curreney and rising priccs. 15a

"compc:titive

H

natian one with aIargc positive halanee

o trndd Switzerland has roughly balaneed trade Italy

has achmnie tntde ddicit-both nations enjay strongly

rising mtional income. Is ."rompctitive" nation one

with low labor OO5t.'llIndia and Mexico both have low

wages Bndlow labor costs-but ncithcr !leemsanaurae-

tive industrial model.

The only meaningful concept o competitiveness at

the nationallevel is produCljvily. The principal goal of

anation is toproduec ahigh and rising standard ofliving

or its citizens. The ability to do so depends on the

produetivity with which a nation'!! labor and capital

are::employed. Productivity is the vlllue of the output

produeed by aunit of labor or capital. Produetivity de-

pends on both the quality and features of produCts

(which dcte:noine the priees dut they ean command)

and the dficieney with which they are produced. Pro-

duetivity is the prime detcrmilUnt o a nation's long-

nm mandard of living: it is the root C8useof nariana}

per capita income. Theproduetivity of human re.'1ourees

dett:nnines employee wages thc produetivity with

whieh capital ia employed determines th\". retuen it

caens for its holders.

A nation's standard of living dcpend'l on the capacity

o its companics toachicve high levcls of pmduetivity-

.nd to increase produetivity over time. Sust4ined pro-

duCtivity gmwth rcquires tbat an economy continually

upgrade ftsell. A nation's companies must relentlessly

imprnve productivity in existing industries by raising

produet quality. adding desirable features, improving

product teehnology, or boosting produCtion effieieney.

They must devclop the nceessary ClI;pabilitiesto com-

pete inmore::and more sophistie.ated industry segments,

, .

HARVARD BUSINESS REVIEW March-April199Q

" . whc:reproductivity is genc:nlly high. Thcy must fin.ally

dcvdop thc capability to compete in cntirely ncw. so-

phisticated industrie:s.

Intemational tradc and forcign invcstrnttlt can both

improvc 8 nation'8 prnductivity as wcU as thn:aten it.

Thcy support rising national productivity hy allowing

8OJ Ition10speciJ l.lizein those industrie5 and segment.'!

of indu!ltries whcrc its companics are more productivc

and 10impon whcre its companics are Icss produetivc..

No nation can becompetitive in everything. The ideal

is to dcploy the nation's limitro pool o human and

other resources into the mast productivc uses. EvO!

thase nations with the highcst standards of living havc

man)' industries in which local companics are uncom-

petitive.

Ya intenultional uade and forcign investrncnt 11150

can thn:aten productivity growth. Thcy expose ra-

tion's industries to the te5t of intcmational standard

o pmductivity. An industry will lose out if its produc-

tivity is nm sufficicntly higbcr tluln forcign rivals' to

offset any advanugc.'1 in local wage rates. If a nation

loses the abilit)' tocompetein arnngeofhigh-produetiv-

ityfhigb.wage industries, its standard of living is threat-

encd.

Defining national compctitivcnCl'r.l as achicvi.ng a

tr.fIdesurplus or lulanced trade per se is inlllppmpriate.

TIte cxpansion of cxpo1'tSbecause of low wages and a

wcak curreney, littbe gametime that tbe nation imports

sophisticated good:- tbat it:- companics cannot produce

competitively, may bring tTlldeinto balance or surplu!I

but lowers tbe nation'!ll'ltandard of living.. Competitive.

ness ,dso does not mean jabs. )t's thc type of jobs, not

fust tbeability tOcmploy citizens llt lowwages, Wt is

decisivc for c:conomie pmspcrity.

Secking to cxplain ncompetitivcncs.'1" at the national

levcl, thcn, is to answcr tbe wrong question. What we

must undersUlnd instc:.adis tbe determinants mprodue.

tivity .nd tbc nnc of pmduetivity growth. To find .In-

SWCfS, wc mu.'!t focus nOi 00 tbc cconomy as II wbole

hut on speci/ie industries oDd industry segments. We

must underst.and bow IInd wb)' commcrcially viable

skills and teehnolngy are ereatcd,. which un only be

fully undcrstood at the levcl of particular industries. It

h theouteome of the thousand'l of suugglcs for compet-

itive advantage against orcign rivals in particular seg.

ments and industries, in whieh produets and pmccsses

are created and improvcd, that undcrpins the pmccss

of upgrading national produetivity.

When one looks dosely at any national cconomy,

there are striking differmce5 arnong 11nation's indus-

tries in competitive sua:ess. lntem:a.tional advantage

is mten conccntrated in particular industry llCgR1ents.

Cerman expons of c.arsare bcavily skcwed toward higb-

pc::rformancecar.;, whi1eK~n aponsareall cornpaets

and suhcomp,aets. In nUlny industries .lInd:,!cgmenl.'1o

industric.'1, tbe competitors with uue intemational

competitive advant.llgc Arebasw in only o ft.w omioos.

Our SClIreb,thcn, is for the dccisive charnetcnstle of

anatian that allows its compani~ to create and sustllin

campetitive advanugc in panicular fidds-the seareh

is fortbe C(Impetitive adv.antagc o nations. Wean::par-

ticularly coneemed with the dctenninants o inter.

nationAI liUcees!! in tecbnology- and skill-intensive

segments IIndindustries, which underpin high and riso

ing productivity.

CiassiC41 theory cxplains the !lueecss al nations in

partieular industries lused on so-called factor.; of pro-

duetion ~ch as land, bbor, and naturnl rcsourccS. Na-

tions gain factor-ha:'led compuative advantage in

industries th.at make intensive use of the faetol1l thcy

po!I!leSSin abundance. Classical thC(lry, howevcr, has

beco ovCl1lh4dowedin advanccd industries :!OdeCOno-

mi~ by theglohalization o competition and the power

al technology.

A ncw thoory must rccognize tMt in modem intema.

tional compctition, companies compete with global

strategies involving not only trade but abo forcign in.

vesnttent. What a ncw thcory must explain is wby a

nation providc.'1a favoTllblehorne base for companies

that compete intcmationally. The borne hase is the na-

tion in which the essential compctitive advantagcs of

the cntcrprisc are crc.ated and sustaincd. It is where 1I

company's sU1Itcgy is set, wb~ the core produet snd

pmcess tcchnology 15 cre.ued llnd maintained, and

where the mast produetive johs and most lldvanced

skills are located. The presente al tbe home base in a

ruatian has !he greatest positive influence on otber

Iinked domestie industries and leads to other bendits

in tbe nation's cconomy. While tbe owncrship of the

campan)' is ohen concenUated lit tbe horne hase, the

nationality al shareholdcrs is ltCCOndary.

A new thcory must move heyond cornl'arative lIdvan-

tagc tOtbe competitive advantage of a nation. lt must

rdIeet a rieh conception mcompetition !hat neludes

SegIDcntedmarkets, differentiated produet:'!, technology

differcnces, llndcconomies of sea1e. A new tbeory must

go bcyond COStand cxplain wh)' cornpanies from sorne

Mtions are bctter tblln otbers al cre.ating advantagcs

based en quality, ft::.lltures,Ilndnew produet innovation.

A new thcory must begin fmm thepremise thllt compe-

tition isdynamieand evolving; it must answer tbe ques-

rians: Why do some companies based in some nntions

innov.llte mon: tban othersr Why do sorne nations pro-

vide.llnenvironmcnt that cnables companics tOimprove

and innovate faster tban forcign riv21sr

-Michad E. Porter

HARVARD BUSINESS RVIEW Mlltth-Aprlll990 77

Determinants of National

Competitive Advantage

These detenninants crcate the national environ-

ment in which companies arebom and learn how

to compete. (Seethe diagram"Determinants of Na-

tionaI Competitive Advantage.") Eachpoint on the

""~"" Condilions

Reloredond

/

S~ling

In usfries

l. FactorConditions. Thenation's position infac-

tors of production, such as skilled labor or infra-

structure, necessary to compete in a given

industry.

2. Demand Conditions. Thc nature of horne-mar-

ket demand for the industry's product or service.

3. ReJated and Supporting Industries. The pres-

ence or abscnce io the natian of supplier indus-

tries and other related industries that are

intemationally competitive.

4. FirmStrategy. Structure. and Rivalry. TheCOD-

ditions in the nation goveming how companies

are crcated, organized,. and managed, as well as

the nature of domcstic rivalry.

FirmSlrofegy.

Slrudure,

/lo""Ri~I'YI~

I~~I

~

ruthlessly pursue improvements, seeking an ever-

moresophisticated soureeof competitive advantage?

Whyarethey abletoavercome thesubstantial barri-

ers t change and innovation that so often accom.

pany SllcceSS?

Theanswer hesinfOUTbroadattriblltcs ofanation,

attributes that individualIy andas asystem consti.

tute the diamond of nationaI advantage, theplaying

fieldthat eachnatian establishes audoperates forits

industries. These attributes are.

grading. They invested aggressively to build large

modemplants torcapeconomies of scalc. Thcn they

bccameinnovators inprocesstechnology, pioneering

just-in-time production and ahost of other quality

andproductivity practices. Thesc process improve-

ments ledtobetter product quality, bettcr repair re-

cords, andbetter customer.satisfaction ratings than

foreigncompetitors had. Mast recently, Japaneseau-

tomakers haveadvanced to thc vanguard of prodllct

technology andareintroducing new, premiumbrand

names tocompetewith thc world's most prestigious

passenger cars.

Theexampleof theJapaneseautomakers alsoillus-

trates two additional prerequisites for sustaining

competitive advantage. First, acompany must adopt

aglobal approach tstrategy. It must sell itsproduct

worldwide, under itsownbrandname, throughinter-

nationaI marketing channels that it contrals. Atruly

global approach may cvcn require the company to

locateproduction or R&Dfacilities inother nations

to take advantage of lowcr wage rates, to gain or

improve market access, or to take advantage of for-

eigntechnoIogy. Second, creating more sustainable

advantages oftenmeans that acompany must make

tsexisting advantageobsolete-even whileit isstill

an advantage. Japanese auto companies recognized

this; either they would make thcir advantage obso-

lete, or acompetitor would doit for them.

As this cxamplc suggests, innovation and change

areinextricablytied together. Butchangeis anunnat-

mal act, particularly insucccssful companies power-

ful forces are at work to avoid and defeat it. Past

approaches becomeinstitutionalized instandard op-

eratingprocedures andmanagcmcnt contraIs. Train-

ingemphasizes the ane correet way to doanything;

the construction of spccialized, dedieated facilities

solidifiespast practice into expcnsivebrick andmor-

tar; theexisting strategy takcs 00aoauraof invinci-

bility andbccomes rooted inthe company culture.

Successful companies tend to develop abias for

predictability andstability they work 00defeodiog

what they have. Changeistempercd bythc fear that

there ismuch to lose. Theorganization at allleveIs

filters out information that would suggest new

approaches, modifications, or dcpartures romthe

nonn. The intemal environment operates like an

immune systemtoisolateor expel "hostile" individ-

uals who challcngecurrent directions or established

thinking. Innovation ceases the company bccomcs

stagnant it isoo1yamatter of timebefareaggressivc

competitors overtake it.

TheDiamand al Natianal Advantage

Why are ccTtancompanies based in certain na-

tions capablc of consistent innovatioo? Whydothey

78 HARVARD BUSINESS REVIEW March-April1990

'.

damond~and thediamond asasystem-affects es-

sential ingrements for achievinginternabana1 COID-

petitivc Sllccess: the availability o resources and

skills necessary for competitive advantageinanin-

dustry the information that shapes the opportnni-

ties that companies perceive and the dircctions in

which they deploy their resources and skills the

goals oI thc owners, managers, and individuals in

companics; and mast important, tbe pressures on

companies to iovest and innovate. Scc thc insert

"HowtheDiamondWorks:TheItalianCeramic Tile

Industry.JI)

When anational envUonment permits 3nd sup-

parts the most rapid accllffiulation of specialized

assets and skills---sometimes simply bccause D

greater effort and commitment-companies gaio a

competitive advantage. When a oatiooal environ-

ment affarelsbetter ongoinginformaban andinsight

into product and process need<>,companies gain a

competitive advantage. Finally, when thc national

environment presswes companies to innovate and

invest, companiesbothgainacompetitive advantage

andupgradethose advantagcs over time.

Factor Conditions. According to standard eco-

oomie theory, factors of production-labor, land,

natural rcsources, capital, infrastructure-will deter-

mine the flowof trade. A nation will cxport those

goodsthat makemost useof thefactorswith which

it is relatively well endowed. This doctrine, whose

originsdatebacktoAdamSmithandDavidRicardo

andthat is embcdded in classical economics, is at

best incomplete andat worst incorrecto

Inthesophisticated industries that formtheback-

bone of any advanced econorny, anation does not

inherit but instead creates the most important fac-

torsofproduetion-such asskilledhumanresources

or ascientilic base. Moreover, the stock of factors

that anation enjoys at aparticular time islessim-

portant than the mte and efficiency with which it

creates, upgrades, anddcploystheminparticular in-

dustries.

Themost important factorsofproductionarethose

that involvesustained andheavyinvestment andare

specialized. BasiefaetoIS,such asapool of labor or

alocal raw-material source, donot constitute anad-

vantageinknowledge.intensive industries. Compa-

niescanaccessthemeasilythroughaglobal strategy

or eircumvent them through tcehnology. Cootrary

to conventional wisdom, simply having ageneral

work force that is high school or even college

educated rcpresents no competitive advantage in

modero intemational competition. Tosupport coro-

petitive advantage, afactor must behigh1yspecial-

izedto 3Dindustry's particular needs-a scientific

institute specializediooptics, apool ofventurecapi-

tal to fund software companies. These factors are

more scarce, more difficult far foreigncompetitors

HARVARD BUSINESS REVlEW Marcb-Aprill990

to imitate-and thcy requue sustained investment

to create.

Nations suceeedinindustries wherethey arepar-

ticularly goodat factor creation. Competitive advan-

tage resuIts from the presence of world-class

institutions that Rrst createspecializedfactoISand

thcn continually work to upgradethero. Denmark

has two hospitals that coocentrate in studying and

treating diabetes--and aworld-Ieadingexport posi-

tion ininsulin. HolIandhas premier research insti-

tutes inthecultivation, packaging, andshipping of

flowers, whereit is theworld's cxport lcader.

What isnot soobvious, however, isthat selective

disadvantages in the morebasic factors canproda

company to innovate andupgrade-a disadvantage

inastatic model of eompetition canbeeomeanad-

vantagc inadynamic ooe. Wben thcre Isanample

supply of cheap raw materials or abundant labor,

companics cansimply rest ontheseadvantages and

oftendcploytheminefficiently. Butwhencompanies

faceaselective disadvantage, like high land costs,

labor shortages, or the lack of local rawmaterials,

they must innovate andllpgradeto compete.

hnplicit in the oft-rcpeated Japanesc statement,

'Weareanislandnationwith nonatural resources,"

is the understanding that thesc deReieneies have

only servedto spur Japan'scompetitive innovation.

Just-in-timeproduction, orexample, cconomizedon

prohibitively expensivespace.Italianstecl producers

in the Bresciaarcafaeedasimilar set of disadvan-

tages: high capital costs, high energy costs, andno

local rawmaterials. LocatedinNorthem Lombardy,

these privately owned campanies faeedstaggering

logistics costs due to thcir distance romsouthern

portsandtheinefficienciesofthestate-owncdItalian

transportation system. The result: thcy pioneered

technologically advanced minimills that require

onlymodest capital investment, uselessenergy,ern-

play scrap metal as the feedstock, are efficient at

small scale, andpermit produeers to locatecloseto

sources of scrap and end-use customers. lo othcr

words,theyconvertedfactor disadvantagesintocomo

petitive advantage.

Disadvantages canbecomeadvantagesonIyunder

certain conditions. First, they must sendcompanies

proper signals abaut circumstances that wiUspread

toother oations, therebyequippingtherotoinnovate

inadvaneeof oreignrivals. Switzerland, thenation

that experiencedthefirst laborshortagcs after World

Warn, isacaseinpoint. Swisscompanies responded

tothe disadvantagebyupgradinglabor productivity

andseeking higher value, moresustainable market

segffients_Companies in most other parts of the

world, whcretherewerestill ampleworkers, focused

their attcntion 00 othcr issues, which resulted in

slower upgrading.

The secondcondition for transforming disadvan-

79

\

' .

Howthe DiamondWorks:

Theltalian Ceramiclile Industry

In 1987, (talun companies were world IClldersin thc

produetion and expon of ct:rlLIDicliles, a $10 biJ lion

industry. ltalian produccrs, concentrated in and.mnnd

the smaIl town of Sassuolo in the Emilia.Romagna re-

gion, accounted for .boUl 30% of world production and

almost 60% of worId apons. Tbc lulian trade surplus

that year in cuamic tilC!'lwas abont $1.4 bi1lion.

The development o the Italianct:ramic tileindustry's

competitivc advanuge iIIumratCll how thc diamond of

I\titional adv8ntage works. Sa1lsuolo'ssustllin.hlc com-

petitivc advanuge in ceramic liles grcw nOl from any

5UtiC or historical advantagt: bUI from dyn.amism and

change. Sophisticated and demandin; local buyers,

stmng and uDique distribution ehannels, and ntense

rivalry amo118local companics eteated consunt pres.

SIIn: lar nnovalioo. Knowlcdgc grcw quickly fmm con.

tinuous cxpcrimentation and cumulativc production

cxperienee. Private ownaship of the comp2nies and

loyalty tO the community 5ptwncd intense commit-

rncnt to invcst in the industry.

Tile producen; bendlted 8S wcll fmm a highly de-

vdoped Set o local machinery fluppliernand other su~

porting industries, producing materials, servioes, .nd

iofmstmcture. The presence of world-class, ltalian-

rc:lated industries also reinforced IUllian Sttcogth in

tiles. Finnlly, the geogrsphic conccntr"ation of the entirc

cluster supen:.harged the whole p~. Today foreign

companies cmnpete ag.tinst J lnentirc subculture. 111e

organie nature of this systc:mreprcsents the mOst sus-

tainable advantage of Sassuolo's ccramic tileeompanics.

Tbe Origim othe ltalian Industry

TIle production in Sss.'mologrew out of the canhen-

ware aod cnxkcry industry, whose hiS10rytraces back

tothe thineenth century. Immediately after World War

11,there wereonly ahandful of cccamie tile INInufaetur-

crs inand amund Ssssuolo, .1111 saving the 10000l market

c:xclusively.

Demand far ccramie tiles within Italy hq;an to grow

dram:nieally in the immedillte po5tWlIr yean;, as the

nxonstruction of ltaly ~ed aboomin building ma-

terials of all kinds. ltalian demand for ccramic tiJ es was

panicularly great due to the c1imate, local tastes, .nd

bui1din~techniques.

Bcausc Sassuolo was in a reLnivcly pmsperous ptrt

of J taly, there wcremany who could combine the modo

cst amount of capital and ncctSSllry organizational

skill!'l to S1art a tile com~ny. In ]955, there wcre 14

Sassunlo arca tile companicsl by 1962, there wcrc ]02-

Thc newtile com~nics bcndited fmm a10000l pool of

mcchanically uained workers. The regioo around Ssssu.

010was horne to J lc:rTlIri,M.scrati, Lamborghini, and

other tcchnically sophisticatcd companics. As thc tile

industry besan togrowandprosper, many coginccrs and

skillcd worlters gravitated to the 5uttesSfut companies.

Thc Emerging ltalian nle Cluster

Initially, ltaliao tile produccrs wcredependent on for-

ogo soun:cs al rawmaterials andproduetion tcchnology.

Inthe 19505, the principal raw m.aterials used to malte

rileswcre Molin (white}e1.y", $ince there werc red- but

no whitc-clay dt:pm;itSncar $assuolo, ltalian producers

hadtoimpon the e1aysfremthe United Kingdom. Tile.

making equipmcnt was 8150importcd in the 19505

and 19605: kilns from Ccrmany, America, and Francc

presses for formins tiles fmm Cermany. Sassuolo tile

maken; had toimpon evcn simple glazing m.llchnes.

Ovcr time, the Itatian tile produccrs lcarned how tO

modify imported equipment to lit local circumstance.'I:

redversus whitc e1ays, n.aturaI gasversus heavy oil. As

pt'OCCSstccbnicians frern rile companics leh to Stan

thcir own cquipment companics, alocal rn.achinery io.

dustry lrose in Sas..'Iuolo.By 1970, IUlIi.n companies

h.td emerged as world-cbs..'I producen; of kilm and

presscs the carlier situation had ex.actly reven;ed: they

wcrc cxporting thcir red-clay cquipment for forcigners

to use with white days.

The relarionship betwecn Italian tile and equipment

manufacturcrs was a mutually supporting one, made

cvcn mon:!lObyelose pmximity. Inthc rnid-1980s, there

wcrc sorne 200 Italian cquipment manufaeturcrs more

than 60% were located in the Sassuoln UCIl.111ecquip-

ment manufaeturas competed fien:ely for local busi.

ness, andtile msnufaeturcrs benefited fmmbetter prices

andmore lIdvanccd cquipmcnt than their foreign rivals.

As the emeJ ging tile cluster grcw and conccntrated

in the *suolo regioo, a pool of skilled worltcrs and

tcchnicians devclopcd, inc1uding enginccrs, production

spccialistS, nuintcnancc worlters, service teehnicians,

and design pel'!mnocl. The industry's gengraphie con.

centration ClIcouraged other supporting companies to

form, offering mold'l, paeuging INIterials, glazes, nnd

trnnsport1ltion (Ilerviccs.An amly of small, specialiud

consulting companies emerged to give advice to tile

producers on plant dcsign, logistics, and enmmadal,

adverti!ling. and fiscal manas.

With its membership concentrated in the $as!luolo

arca, Assopiastrelle, the cenmic tle ndustry associs-

tion, hegan offering serv1CC5in area!'lof common nter-

CS1: bulk purchasing.. foreign.market research, llnd

consulting onfiscal and legal matten;. The growing tile

cluster stimulated the formation of a new, l'lpCCializcd

flletor-crcating institution: in ]976, aconsortum of the

80

liARVARD BUSINESS REVlEW Mnrch-Aprill990

'.

University o Bologna, rq;ional agencies, IInd the ce-

runic indusuy assoc:iation founded the Centro Cera-

mico di Bologna, which c:onductcd prOttSs research and

product analysis.

Sophisticated Home Dem,nd

By me mid-J 960s, per-capita tile consumption inluly

was considerably highcr than in lhe TC5tuf the wortd.

Thc Italian marltet was.also the world's most sophisti-

cate<!. J ulian c:ustomers, who were gcncrally the first

to.adoptnew designs 3ndfCltu~, lIndItal iaoproduccrs,

who consuntly innov.ated to impmve manufactung

m~ods Bndcreate new designs, progressed in a mutu-

.lIy reinforcing pmccss.

The unique1y sophisticated charaeter ol domcstic de.

m.andl!Ilsoextended to retail OUtlet5. In the 196Cb,spe-

ciatizcd tileshowrooms hcgan openingin Itllly. By1985,

thm: wcrc roughly 7,600 specializcd showrooms han-

dling IIPJ lroximately 80% of dorncstic Slllcs, fu more

thaR in other nations. In 1976, the J tali.lln cornpany

Picmme intrnduccd tiles by famous designers to gaio

distrihutinn outlets aad tObuild hmnd IUmC.w'u'cness

.lmong consumcrs. This innovation drcw on anotht:r

related industry, desWJ , serviccs, in whiclJ J taIy wa!l

world J eader, with over $10 hillion in ocports.

Sassuolo Rivalry

TIte sheet numbcr o tile companics in thc Sassuolo

ara creatcd intense rivalry. News of product lIndpro-

CC5.'l innovationsllpread IlIpidly, and companics sr:cking

technological, design, and distribution 1eadcrship had

to impmve: conlltantly.

Proximity addeda pcr.on:alnote tothe intenseriv.l1ry.

AJ I of tbc produccrs were privatcly hdd, most wt:refllm-

ilr run. ThCDWncr.lllJ llived inthesarncarea,kncwcsch

othcr, aod were thc leading citizc:os of thc sarnc lOwnS.

PttSsuttS to Upgnde

J n the early J 9705, faced with ntense domestic ri-

valry, prcssure fmm m.-il customel1'l, .lod the shock of

the 1973 energy crisis, ltali.ln tile comIUnies struggled

to rmuce gas and l:abor ar.'Its. Thcse dlorts led to a

tcchoological brcakthrough, tbe: rapid singlc-firing pro-

ces!!, io which thc hardcnins; process, nuterial trans-

formation, and glazc:-fixing all occum:d in ooe pa~

through thc kilo. A proccss tbat too,", 225 cmployecs

using the double-firing methCMIneo:led ooly 90employ-

ces using singlc-firing mJ ler kilns. CyeJ e timc ciroppr:d

frnm 16to 20 hours tOonly SO lO55 minutt:S.

The ncw, smallcr, .nd lightcr cquipmcnt was .Iso

casicr lo export. By tbe early 19805,cxports fromltalian

cquiprnent rrulOuf.cturers exc:ccdcd dorncstic sales; in

1988, aports rcpresentcd almost 80% 01 total sales.

Working togethcr, tile manubcturcrs and cquipment

manufacturers nude tbe nen imponant brcakthrough

during thc mid- and la.tC 1970s; the devdopmcnt of

materials-handJ iog cquipmcnt trua transformcd tilc

manufacture roroabatch proccss to acontinuous pro-

cess. 111cinnovation rcduccd high labor cm;t....... wruch

luidbeen.a substanti.al sclcctive factor disadvllntage fac-

ing ltaliao tilc manuf.aetutc:rs.

111c cornmon pcn:c:ption is that J talian labor easts

were lowcr during this perind than tbasc in thc Unitcd

Sutes dod Ccrmany. In thosc two countries, bowcver,

diffcrcnt jobs had widcly diffcrent wagcs. InItaly, wages

for different skill catcgories wcre compres.'lcd, and work

rules constraincd manufacturcr.; from using overtime

or multiple shifts. Tbc rcstriction proved costly: once

conl, kiln!'l are cxpensivc to reheat nnd are bcst run

continuously. Bccause of this factor disadvantage, the

ltalian companic8 wcrc thc first to devdop continuous,

automatcd produC;tion.

Intcmationalization

By 1970, J ulian domestic dcmand bad matured. The

slsgnant J tali:m madct led companics to stcp up their

cfforts to pursue loreign madcts. The prescnce of re-

lated and supponing Italiao industries hclpcd in thc

expon drive. Individl.LA1 tile manufaeturers bcgan .lldvcr-

tising in ltalian and forcign homc-design and archi-

tectural magazines, publications with wide global

circullltion nmongarchitcets, dcsignen;, and consumcl1'l.

TItis hcightcnod awaren~'i rcinforced thcquality imngc

of ltali.n tiles. nlc makcrs wcre also able to apitalize

on ltaly's Ic.adingworld cxport positions in relsted in.

dunries Hitemarble, building stonc, sinb, washbasins,

fumiture, lamps, .lIndhome llpplianees.

Assopillstrcllc, the industry .SSocilltion, cstablished

tnufc-promotion officcs in thc Unitcd SUtes in 1980,

in Cermnny in 1984, .andin France in 1987. It organized

elaborate uadc ahows in cities ranging lrom Bolognll 10

Miami and nm!lOpbisticatcd advcnising. Bctwcen 1980

nnd 1987, thc associAtian spcnt roughly $8 million tO

promote Italma tilcs in thc Unitcd Ststes.

-Michael J . Enright snd Paolo Tcnti

MirlJad /. Enr1glrt. a doctora' Madent In lmsfru:,'t~t'.ronomfes

al tbelIarvmd BusIness School. PQformt'.d trtlmaflU.~rt'.$Mrch

attd sopervi.fory tlJSk.. fur Thc CompetitIve AdvlInuge of Na.

tions. PDOIo 'lentl was respoTl.Qble /or 1M. ltnlfnn pnrt of re.

setfrch ondml1ken fartbe book.lle Is tl con.rultant in strategy

ttnd {int1Tlu 1m Monitm eomp.my attd Ana1y:rfs F.A.-MilQn.

,

HARVARD BUSINESSREVlEW Marc:h-April 1990 81

tages into advantages is favorable circurnstances

elsewherein thediamond--a consideration that ap-

plies toalmost a11determinants. Toinnovate, com~

palies must haveaccesstopeoplewith appropriate

skiils andhavehome-demand conditions that send

theright signals. They must alsohaveactivedomes-

tic rivalswho createpressurc toinnovate_ Another

precondition iscompany goalsthat leadtosustained

commitment tothe industry. Without such acom-

rnitmcnt and thepresence of active rivalry, acorn-

pany may take an easy way around adisadvantage

rather than using it asaspur to innovation.

For example, U_S_consumer-electronics compa-

nies, facedwith high relative labor costs, chose to

lcavetheproduct andproduction processlargelyun-

changedandmave lahor.intensive activities to Tai-

wanandother Asianeountries. Instead of llpgrading

their sourcesofadvantagc, thcyscttlcd farlabor-cost

parity. Ontheather hand, Japane.<:;e rivals, confronted

with intense domestic competitian and a mature

hornemarket, chosetoeliminate labortbrough auta..

mation. Thisledtolower assemblycosts, toproducts

withfewercomponents andtoimprovedquality and

reliability. SoonJapanesecompanies were building

assemblyplants intheUnitcd $tatcs----theplaccu-s.

companies hadfled.

Demand Conditions. It might seem that the

globalization ofcompetition woulddiminish theim-

portance ofhomedemand_Inpractice, however, this

issimply not the case. Infact, the composition and

character of the home market usually has adispro-

portionate effect onhowcompanies perceive, inter-

pret, and respond to buyer needs. Nations gain

competitive advantageinindustries wherethehorne

demand gives their companies a clearer or earHer

picture of emerging buyer needs, and where de-

manding buyers pressure eompanies to innovate

faster and achieve more sophisticated competitive

advantagesthan their foreignrivals. The,sizeofhome

demandprovesfarlesssignificant than thecharacter

of hornedemando

Home~demandconditions help build competitive

advantage when a particular industry segment is

larger or more visible in the domestic market than

inforeigomarkets. Thelarger market segments ina

nation receivethe most attention &omthenation's

companies; companies accord smaller ar less desir-

ablesegments alower priority. A goodexample is

hydraulic cxcavators, wmch rcpresent the most

widely used typeof constru.ction equipment in the

Japaoesedomestic market-but which compriseafar

smaller proportion of the market in other advanced

nacioos. This segment isoueof thc fcwwhcrc there

arevigorousJapaneseintemational competitors and

whcre Caterpillar doesnot hold asubstancial share

of the worldmarket.

82

Moreimportant than thc rnixof segmentsper seis

thenature o domestic buyers_Anation'scompanies

gain competitive advantage if domestic buyers are

the world'smost sophisticated anddemanding buy-

ers for the product ar service. Sophisticatcd, de-

manding buyers provide awindow into advanced

customer needs; they pressure companies to meet

highstandards; they prodthemtoimprove, toinno-

vate, andto upgradeinto more advanced segments.

Aswith factor conditions, demand conditions pro-

videadvanta.gesby forcingcompanies to respondto

toughchallenges.

Especially stringent needs arise because of local

valu.es and circumstances. For example, Japanese

conswners, wholiveinsmal}.tight1ypackedhomes,

must contend with hot, humid surnrners and high.

cost electrical energy-a daunting combination of

crrcumstances. In response, Japanese companies

havepioneeredcompact, quiet air-conditioningunits

powercdbyencrgy-savingrotary compressors. Inin-

dustry atter industry, thetightly constrained require-

ments o theJapanesemarket haveforcedcompanies

toinnovate, yieldingproducts that arekei-haku-tan-

sho-light, thi~ short, small-and that areintema-

tionally accepted.

Local buyers can help anation's companies gain

advantage if their needs anticipate or even shape

those o other nations--- if their needsprovideongo-

ing "early~waming indicators" of global market

trends. Sometimes anticipatory needs emerge be-

cause anation's political values foreshadow nceds

that wiil grow elsewhere. Sweden's long-standing

concemior handicapped peoplehas spawned anin-

creasingly competitivc iodtL.try foctL.ed 00special

needs. Denmark's environrnentalism hasledtosuc-

cessforcompanies inwater-pollution control equip-

meot andwindmills.

Moregenerally, anation's companies can antici-

pateglobal trends if the nation's values arespread-

ing-that is, if the country is exporting its values

andtastes aswell asits products. The international

SllCceSSo U.$. compames in fast food and credit

cards, for example, reflects not only the American

desirefor convenience hut aIsothe spreado these

tastes tothe rest of the world. Natioos export their

values and tastes through media, through training

foreigners, through political influence, andthrough

theforeigoactivities oftheir citizens andcompanies.

Relared and Supporting Industries. The third

broad determinant of national advantage is the

presence inthe nation of related andsupporting in-

dustries that areinternationally competitive. Inter-

nationally competitive home-based suppliers create

advantages in downstream indtLtries in several

ways_First, they deliver the most cost.effcctive in-

puts inancfficient, early,rapid, andsometimes pref-

HARVARD BUSINESS REVlEW March-Apri11990

erential way. ItaHan gold and sil ver jewelry

companies lcad the world in that industry in part

because other Italian companies supply two-thirds

af thc world's jewelry-making and precious-metal

recyc1ingmachinery.

Far more significant than mere access to campo-

ncnts and macmnery, however, i8thc advantage that

home-based related and supporting industries pro-

vide in innovaton and upgrading-an advantage

based 00closeworking relationships. Suppliers and

end-users locatedncar eachother cantakeadvantage

of short lines of communicatioD, quick andconstant

flow af informatan, and aD ongoing exchange af

ideasandinnovatiollS. Campanies havetheopportu-

nity toinfluence their suppliers' technical effortsand

can serve as test sites for R&D work, accelerating

the paceof innovatioo.

Theillustration of "The Italian Footwear Cluster"

offersagraphic cxample of how agroupof close-by,

supporting industries crcatcs competitive advantage

in arange of intcrconnected industries that are a11

internationally competitive. Shoeproducers, fur in-

stanee, interaet regularly with leather manufacturcrs

on new styles and manufacturing tcchniques and

learn about newtextures andcolors of leather when

they arestill on the drawing board..Leather manu-

faeturers gainearlyinsights intofashiontrends, help-

ing them to plan new products. Thc interaction is

mutually advantageous and self-reinforcing, but it

does not happen automatically: it ishelped byprox-

imity, but occursonIyhecausecompanies andsuppli-

ers work at it.

Thc nation's companies benefit most when the

suppliers are, themselves, global competitors. It is

ultimately sel.defeating for acompany or country

to create "captive" suppliers who aretotally depen-

dent on the domestic industry and prevented rom

serving foreign eompetitors. Bythe same token, a

nation neednot becompetitivc inall supplier indus-

tries faritscompanies togaincompetitive advantage.

Companies eanreadilysowee fromabroadmaterials,

components, or technologies without amajor effect

oninnovation or performance of theindustry's prod-

uCS.The same is true of other generalized tech-

nologies---like eleetronics or software-where the

industry represents anarrow application area.

Home-based compctitiveness inrelated industries

provides similar benefits: information flowandtech-

nieal intcrchange speed the rate of innovation and

upgrading. A home-based related industry also in-

crea...e. the likelihood that companies will embrace

new skills, and it also provides asowee of entrants

who will bring anovel approach to competing. Thc

Swisssuccess inphannaceuticals emergedout ofpre-

vious intemational success in the dyc industry, for

exampIc; Japanesedominance in e1ectronic musical

HARVARD BUSINESS REVIEW March~Apri11990

keyboards grows out of success in acoustie instru-

mcnts combined with astrongposition inconsumer

electronics.

Firm StIategy, Structure, and Rivalry. National

circumstances and context create strong tcndencies

in how companies areercated, organized, and man-

aged, aswe11aswhat the natwe of domestic rivalry

will be.InltaIy, forcumple, successful international

competitors areoftensmall or medium-sized compa-

nies tbat areprivately owned and operated like ex-

tended families; inGermany, incontrast, companies

tend to be strictly hierarerncal in organization and

management practices, and top managers usually

have technical backgrounds.

No one managerial system is universally ap-

propriate-notwithstanding the cwrent fascination

with Japancse management. Competitiveness in a

specific industry results from convergence of the

management praetices andorganizational modes fa-

voredinthe country andthe sources of compctitive

advantageintheindustry.ln industries whereltalian

companies areworldleaders-such aslighting, furni.

ture, footwear, woolen fabrics, and packaging ma-

ehines-a company strategy that emphasizes foeus,

customized products, niehemarketing, rapidchange,

and breathtaking flexibility fits both the dynamics

of the industry andthe charneter of theltalian man-

agement system. The German management system,

in contrast, works well in technical or engineering-

oriented industries-opties, chemicals, complicated

maehinery-where complex products demand preci-

sion manufaeturing, aeareful development process,

after-saleservice, andthus ahighIy disciplined man-

agement structure. Gennan success ismuch rarer in

consumer goodsandserviceswhereimagemarketing

and rapid new-feature and model turnover are im-

portant to competition.

Countries also differ markedly in tbe goals that

companies and individuals seek to achieve. Com-

panygoalsreflect thecbaracteristies ofnational capi-

tal markets and the compensation praetices far

managers. For example, in Germany and Switzer-

land, wherebanks comprise asubstantial part of the

nation's shareholders, most shares areheld for long.

termappreciation and arerarely traded. Companies

dowell inmatute industries, where ongoing invest-

ment in R&D and new facilities is essential but re-

turns may be onIy moderate. The United States is

at the opposite extreme, with alarge pool of risk

capital but widespread trading of public companies

andastrong empbasis by invcstors onquarterly and

annual share-price appreciation. Managernent com-

pensation isheavily basedonannual bonuses tied to

individual resutts. America does well in relatively

new industries, like software and biotechnology, or

anes where equity funding of new companies feeds

83

" .

TheItalianFootwear Cluster

tnjedion-

I

. 6

nidding

Mochirtery

,

~

,

~" "

,

M,,""

,

,~

,

'""h

,

,

,

" " " " " " " ''''''

~

ModoI.

EJ

-

,

,

I ~~ I

_01

~

f -. ,. . f -. ,. .

@

Design

Scrvices

\

I.euttref ....orl,lng

~

Modllnery

active dorncstic rivalry, Iikc spccialty c1cctronics and

services. Strong prcs!'>urc.o; lcading to undcrinvcst.

ment, however, plague more matUTe industrics.

IndividU31motivation to work and cxpand skills

is also important to competitivc advantagc. Out-

standing talcnt is ascarcercsoUTCC in any narion.

A nation's success largely depends on the typcs of

cducation jts talcntcd pcople choose, where they

choosc to work, and thcir commitment and effort.

Thc goals anatioo's institutions and valucs sct far

individuals and comp.1nics, and thc prestigc it ato

taches to certain industries, guidc thc flow o capital

and human resourees--which, in turo, dircctIy a E .

fects the competitive performance of certain indus-

tries. Nations tend to becompetitive in activitics

that pcoplc admire or dcpcnd on-the activities froro

whic.h thc nation's hcrocs emerge_InSwitzerland, it

isbanking and pharmaccuticals. InIsrael, the highcst

callings havc bccn agriculturc and defense-related

fields. Soroctirocs it is hard to distinguish bctween

84

HARVARD BUSINESS REvmW Mareh-April 1990

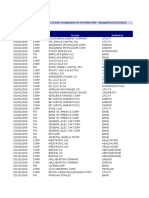

Estimated Number of Japanese Rivols in

Selected Industries

SoVn;"e$: Fieldintervi"""",;Nippon /(ogro Shinfxm, Nippon lCogyo

Nenkan, 1987; YonoReM!Orch, Morket5horeJiton, 1987; reseorchers'

estimotes.

*Thenumbe!"of componies varied by product orea. lhe smollest

number, 10, produced bulldozers. fifteen companies produced shavel

truoo, trua aones, and osphah-paving equipment. lhere werll 20

companies inhydruulic excovolors, o pmduct oroo where lepan wos

porticulcrly strong.

tSixcomponies had annuol production exports inexcess of 10,000

tons.

tInlegrutedcompanies.

cause and effect. Attaining international success can

make an industry prestigious, reinforcing it8 advan-

tagc.

The presence o strong local rivals i8a final, and

powerful, stimulus to thc creation and persistence

of competitive advantage. This is true of small coun-

tries, likc Switzerland, where the rivalry among its

pharmaceutical companies, Hoffmann-La Rache,

Ciba-Geigy, and Sanrloz, contributes to a leading

worldwidepositioo. lt i8true in the Unitcd Statcs

in thc computer and software industries. Nowhere

i8 the role of heree rivahy more apparent than in

J apan, where there are 112companies competing in

machine tools, 34 in semiconductors, 25 in audio

equipment, 15in cameras-in faet, there are usually

double figures in the industries in wmch Tapanboasts

global dominance. fSeethe table "Estimated Number

of J apanese Rivals in Selected Industries.'" Among

aH thc points 00 the diamond, domestic rivalry is

Air Conditioners

Audio Equipmenl

Automobiles

Cameros

Cor Audio

Carban Fibers

ConslrlJ etion Equipmenl*

Copiers

Focsimile Machines

large-scole Compufers

lift Trucks

Machine Tools

Microwove Equipment

Motorcydes

Musicollnsfruments

Personal Compulers

Semicondoctors

Sewing Mochines

Shipbuilding1

Steelt

Synthetic Fibers

Television Seis

Truck ond Bus Tires

Trucks

Typewrifers

Videocossetle Recorders

13

25

9

15

12

7

15

lA

10

6

B

112

5

A

A

16

3A

20

33

5

B

15

5

11

lA

10

arguably the most important heCalL,>eof thc power.

fully stimulating efcct it has on aHthe others.

Conventional wisdom argues that domestic com.

petition is wasteful: it leads to duplication of effort

and prevents companies romachieving ecooomies

of scalc. The "right solution" is to embrace one or

two national champions, companies with the sca1e

and strength to tack1e foreign competitors, and to

guarantee them the necessary resourccs, with the

govemment's hlessing. In fact, however, most na.

tional cbampions are uncompetitive, although heav.

ily subsidized and protceted hy their government. In

many of the prominent industries in which there is

onIy one national rival, such as aerospace and tele-

oommunications, govemment has playcd alargerole

in distorting competition.

Static efficiency is much Iess important than

dynamic improvement, which domestic rivalry

uniquely spurs. Domestic rivalry, like any rivalry,

creatcs pressure on oompanies to innovate and im.

proveo Local rivals push each othel to lower costs,

improve quality and service, and create new products

and proeesses. But unlike rivalries with foreigo como

petitors, which tend to be analytical and distaot,

local rivalries often gobeyond pure economic or busi.

ness competition and become intensely personaL

Domestic rivals engagein active feuds; they compete

not ooly fOI market share bnt also for people, for

technical excellence, and perhaps most important,

for "bragging rigbts." Qne domestic rival's success

proves to others that advancement is possible and

often attracts ncw rivals to the industry. Companies

often attrihute the success of foreign rivals to "un.

fair" advantages. With domestic rivals, there are no

excuses.

Geographic concentration magnifies the powcr of

domestic riva1ry. This pattem is strikingly common

around the world: Italian jewelry companies are lo.

cated around two towns, Arezzo and Valenza Po;

cutlcry companies in Solingen, West Germany and

Seki, Tapan; pharmaceutical companies in Basel,

Switzerland; motorcycles and musical instrumeots

inHamamatsu, Tapan.The more localized the rivalry,

the more intense. And the more intense, the hetter.

Another benefit of domestic rivalry is the pressure

it creates for constant upgrading of the sources of

competitive advantage. The prescncc of dorncstic

competitors automatically canccls the typcs of ad.

vantage that come romsimply being in aparticular

nation-factor costs, access to 01 preference in the

horne rnarkct, or costs to foreigo competitors who

import into the market. Companies are forced to

move beyond thero, and as arcsult, gain more sus.

tainahle advantages. Morcovcr, oompeting domestic

rivals will keep each othcr honcst in ohtaining gov.

crnment support. Companies are less likely to get

HARVARDBUSINESSREVIEW March-Aprill990 85

.

hooked onthe narcotic Di govemment contracts DI

creepingindustry protectionism. Instead, theindus-

try will seek~and bencit rom-more constructive

forms D i government support, such asassistance in

opening forcignmarkets, aswell as investments in

focusededucational institutions or other specialized

factars.

Ironically, iti8alsovigorousdornestic competition

that ultimate1y pressures domestic companies to

lookatglobal markets andtoughens therotosucceed

in thero. Particlllarly when there areeconomies n

scale, local competitors forceeachother tolaok out-

wardtoforeignmarkets tocapturegreatcr efficiency

andhigher profitability. Andhaving been testcd by

ficreedomestic competition, thestronger companies

arewell equippedtoWnabroad.IfDigital Equipmcnt

canholdits ownagainst IBM,DataGeneral, Prime,

;lndHewlett-Packard, going up against Siemem or

MachinesBull doesnot seemsodaunting aprospecto

The Diamond os a System

Each of these four attributcs defines apoint on

thediamondof national advantage theeffect ofQue

point oftendepends00thestateof othcrs. Sophisti-

cated buyers will not translate inta advancedprod-

ucts, for example, unless the quality of human

resources permits eompanies to meet buyer needs.

Seleetivedisadvantages infactorsofproduction will

not motivate innovation unless rivalry is vigorous

and company goals support sustained invcstment.

At thebroade.~tlevel, weaknesses in anyane deter-

minant will constrain anindustry's potential forad-

vancement andupgrading.

Butthepoints ofthediamondarealsoself~reinforc-

ing: they eonstitute asystem. Twoelemcnts, domes-

tic rivalry and geogr.aphie concentration, have

espeeiallygreatpowerto transformthediamondinto

asystem-domestic rivalry becauseit promotes im-

provement in all the other detenninants and gro-

graphic concentration because it e1evates and

magnifies theinteraction of the four separateinflu-

ences.

The role of domestic rivalry illustrates how the

diamondoperatesasaseH-reinforcingsystem. Vigor-

ous domestic rivalry stimulates tbedevclopment of

unique pools of specialized factors, particularly i

the rivals arealllocated in onecity or region: the

University of California at Davis has beoome the

world's leading center of winc-making research,

working closely with the California wine industry.

Active local rivals also upgrade domestic demand

in anindlL~try.Infumiture and shoes, for example,

Italian consumers haveleamed t cxpcct more and

betterproducts becauseoftherapidpaceofnewprod-

uct development that is drivenbyintense domestic

rivalry aIDonghundreds of Italian eompanies. 00-

mestic rivalryalsopromotes theformation ofrelated

and supporting industries. Japan's world-lcading

groupof semiconductor produeers, for instance, has

spawned world-leading Japanese semiconductor-

equipment manufacturers.

Theeffects canwork inall directions: sometimes

world-class suppliers become new entrants in the

industry theyhavebeensupplying_Or highlysophis-

ticated buyers may themselves enter asupplier in-

dustry, particularly when they havc relcvant skills

andviewthe newindustry asstrategic. Inthe case

of theJapaneserobotics industry, for example, Mat-

sushita andKawasaki originaUydesignedrobots for

interna! usebeforebeginningtoseUrobotstoothers.

Today they are strong competitors in the roboties

industry. InSweden, Sandvik movedfromspecialty

steel into rock drills, andSKFmovedfromspecialty

stecl into ball bearings.

Another effect of the diamond's systemic nature

isthat nations arerarely hornetojust onecompeti-

tive industry rather, the diamond creates an en-

vironment that promotes cJusters of competitive

indlL~tries_Competitive industries arenot scattered

helter-skelter throughout theeconomy but areusu-

allylinkedtogether through vertical jbuyer-seller) or

horizontal (common customers, teehnology, chan.

neis!relationships. Nor areclusters usually scattered

physicallYi they tend to beconcentrated geographi-

eally. Onecompetitive industry helps to create an-

other in a mutually reinforcing process. Japan's

strength ineonswner clectronics, forexample, drove

its success in semiconductors toward the memory

chipsandintegrated circuitstheseproduets use. Japa-

nese strength in laptop computers, wmeh contrasts

to limited success in other segrncnts, rcflects thc

baseof strength inother compact, portableproducts

andlcadingexpertise inliquid-crystal displaygained

inthe ca1cu1atorandwatch industries.

Onceacluster forms, thewholegroupofindustries

becomesmutually supporting_Benefitsflowforward,

baekward, andhorizontally. Aggressiverivalryinone

indlL~tryspreads to others in the cluster, through

spin-offs, through the exerciseof bargaining power,

and through diversification by established compa-

nies. Entry fromother industries within thecluster

spursupgradingbystimulating diversity inR&Dap-

proaches and facilitating the introduction of new

strategies andskills. Tbroughtheconduits of suppli-

ers or customers who have contaet with multiple

competitors, information flows freely and innova-

tions diffuse rapid.1y.Interconnections within the

cluster, aften unantieipated, lead to perceptions of

newwaysof competing andnewopportunities. The

HARVARDBUSINESSREVIEW March-Aprill990

,

cluster becomes avehiclc faI maintaining diversity

andovercomiogtheinwardfOCllS, inertia, inHexibil-

ity, andaccommodation amongrivals that slows or

blocks competitivc upgradingandnewentry.

The Role 01Government

Inthecontinuing debateover thecompetitiveness

o nations, no tapie engenders more argument ar

creates less unrlcrstanding than the roleo thc gov-

ernrncnt. Many see government as an essential

helper or supporter o industry, employing ahast

D E policies to contribute directly tothecompetitive

performance astrategic DI target industries. Others

accept the "frcemarket" viewthat the operation o

the economy should be left to the workings o the

invisible hand.

Both views areincorrecto Either, followed to its

logical outcome, would lead to thc permanent ero-

SiDO of acountrls competitive capabilities. Onone

hand, advocates of goveroment helpforindustry fre-

qucntly propose policies that would actually hurt

companies in the long ron nnd oruy create the de-

mandformorehelping. Onthc other hnnd, advocates

of a diminished government presence ignore the

legitimate role that government plays in shaping

the context andinstitutional structure surrounding

companies andincreatinganenviroomcnt that stim-

ulates companies togaincompctitive advnntage.

Government's proper roleisasacatalyst andchal-

leoger; it istoencourage-or evenpush-companies

tomisetheir aspirations andmovetohigher levelsof

compctitive performance, eventhough tbis process

maybeinherently unpleasant anddifficult. Gavera-

ment cannot create competitive industries; only

companies candotbat. Government playsarolethat

isinherently partial, that succeeds onlywhen work-

ingintandemwith favorableunderIyingconmtions

iothemamond. Still, government's roleof transmit+

ting and amplifying the forces of the diamond is a

powerful one. Government policies that succeedare

those that create an environment in whieh eompa-

nies can gain competitivc advantage rather !han

thosc that involve government direetIy in the pro-

eess, cxccptinnations earIyinthedevelopment pro-

cesS.It is anindireet, rather than amrcct, role.

Japan's government, at its best, understands tbis

role better than anyone- including the point that

nations pass through stagesof competitive develop-

ment and tbat govemment's appmpriate role shifts

asthc economy progresses. Bystimulating early de-

mandfor advancedproducts, confronting industries

with theneedtopioncer frontier technology through

symbolic cooperative projects, establishing prizes

HARVARDBUSINESSREVIEW March-Aptill990