Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Addison Disease: Diagnosis and Initial Management

Enviado por

Teguh RahTítulo original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Addison Disease: Diagnosis and Initial Management

Enviado por

Teguh RahDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

834 Reprinted from AUSTRALIAN FAMILY PHYSICIAN VOL. 39, NO.

11, NOVEMBER 2010

Background

Adrenal insufficiency is a rare disease caused by either

primary adrenal failure (Addison disease) or by impairment

of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. Steroid

replacement therapy normalises quality of life, however,

adherence can be problematic.

Objective

This article provides information on adrenal insufficiency

focusing on awareness of initial symptoms and on

risk scenarios, emergency management and baseline

investigations, complete investigations and long term

management.

Discussion

Early recognition of adrenal insufficiency is essential

to avoid associated morbidity and mortality. Initial

diagnosis and decision to treat are based on history and

physical examination. Appropriate management includes

emergency resuscitation and steroid administration. Initial

investigations can include sodium, potassium and blood

glucose levels. However, complete investigations can be

deferred. Specialist advice should be obtained and long

term management includes a Team Care Arrangement. For

patients, an emergency plan and emergency identification

are essential.

Keywords: Addison disease; diagnosis, differential;

fludrocortisone; hydrocortisone; patient care planning

Susan OConnell

Aris Siafarikas

Addison disease

Diagnosis and initial management

Primary adrenal insufficiency was first described

by the English physician Thomas Addison in 1855.

1

Addison disease is a rare condition with an estimated

prevalence of 411 per 100 000 and an incidence of 0.8

per 100 000 population/year.

2,3

In children, boys constitute

approximately 75% of patients in contrast to adults, where

the majority (70%) are women.

4

The underlying pathology is

a destruction of the cortex of the adrenal gland.

5

Secretion

of cortisol is reduced or absent, with or without associated

reduction or absence of aldosterone. Adrenocorticotrophic

hormone (ACTH) levels are increased.

2

Historically, tuberculosis was the most common cause of Addison

disease.

4,5

Today however, 7080% of all cases of Addison disease

in the Western world are due to autoimmune adrenalitis;

4,6

whereas

worldwide infectious diseases such as tuberculosis,

7

fungal

infections (histoplasmosis, cryptococcus), and cytomegalovirus are

still important causes. Acute haemorrhage (ie. in meningococcal

septicaemia) although uncommon, is also a cause of primary adrenal

insufficiency.

5

Overall, Addison disease in the paediatric population is most

commonly attributed to primary adrenal insufficiency, which occurs in

approximately one in 15 000 births and usually presents in the neonatal

period or early childhood.

8

Ninety-five percent of cases are due to

deficiency of an enzyme (21 hydroxylase) involved in the steroidogenesis

pathway, which also results in impaired aldosterone synthesis. In

contrast to Addison disease, the adrenal cortex is not destroyed and

hence increased ACTH stimulation causes adrenal hyperplasia.

5

Concomitant autoimmune disease is seen in 50% of patients with

Addison disease. These include thyroid disease, hypoparathyroidism

and type 1 diabetes mellitus.

5

More complex associations can be found

in two recognised polyglandular autoimmune syndromes (PGA).

5,8,9

Secondary forms of adrenal insufficiency, characterised by low

ACTH levels, are caused by hypopituitarism due to pituitary disease,

or suppression of the hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal axis (HPA)

following steroid therapy or endogenous steroid excess (ie. tumour).

The role of inhaled steroids is controversial. It has been suggested

that therapy with more than 800 g/day over a prolonged period of

time might result in HPA suppression.

10

In secondary adrenal insufficiency, secretion of aldosterone is

not affected. However, with acute hypopituitarism, other hormone

Traps for the unwary

Reprinted from AUSTRALIAN FAMILY PHYSICIAN VOL. 39, NO. 11, NOVEMBER 2010 835

What should I do?

In every scenario the initial diagnosis of acute adrenal insufficiency

and decision to treat are based on history, physical examination, and

occasionally, laboratory findings (hyponatraemia, hyperkalaemia,

hypoglycaemia).

12

Delay in treatment while attempting to confirm

this diagnosis can result in poor outcomes and must be avoided

(Table 1).

13

Management of adrenal crisis

This is a medical emergency.

12,13

Acute management is based

on emergency resuscitation: restoring and maintaining circulation,

administration of IV hydrocortisone, detection and treatment of

hypoglycaemia, and identification and treatment of precipitating

causes. A specialist should be contacted early. In many cases

admission to an intensive care unit will be required.

12,13

Management of the subacute or chronic

presentation

In most cases patients are cardiovascularly stable. Electrolyte

imbalances and hypoglycaemia can be present. Therapy will focus

on steroid replacement and fluid resuscitation. Basic laboratory

investigations include sodium, potassium and blood glucose levels.

Urea, creatinine, calcium and full blood count can be added to

specify underlying causes. Referral to an endocrinologist for further

investigations will be required to confirm primary adrenal insufficiency.

Optional investigations are: serum cortisol, serum ACTH and

24 hour urinary cortisol. If considered necessary, a synacthen (ACTH

stimulation) test can be performed but this should never result in

delayed administration of steroids and should only be performed under

controlled circumstances in the hospital setting.

Education of the patient, and their family, on the diagnosis,

importance of adherence, and an emergency management plan must

be initiated.

Long term management

Long term management may include a Team Care Arrangement

involving a general practitioner, endocrinologist and clinical nurse

specialist. Assistance by social workers and psychologists can be

important. Medical management includes replacement of

cortisol aldosterone. Regular specialist reviews are needed to

optimise therapy.

12,1416

These include: assessment of growth

and pubertal development, looking for clinical signs of adrenal

insufficiency, biochemical analyses of electrolytes, cortisol levels and,

depending on the underlying pathology, ACTH, and monitoring for

other autoimmune conditions.

5

Emphasis will be on the importance

of adherence with medication and adjustments for illness and stress

situations to achieve a good quality of life.

11,13

As steroid replacement

therapy is associated with an increased risk of osteoporosis, further

investigations including dual energy X-ray absorptiometry scans and

preventive strategies such as adequate dietary calcium, exercise and

vitamin D/sun exposure should be considered.

deficiencies including growth hormone, thyroxine, oestradiol or

testosterone, must be identified and treated.

When should I consider an adrenal

crisis?

Adrenal crisis is a medical emergency and should be considered in any

patient presenting with one or more of the following symptoms:

altered consciousness

circulatory collapse

hypoglycaemia

hyponatraemia

hyperkalaemia

seizures

history of steroid use/withdrawal, or

any clinical features of Addison disease.

Adrenal crisis may be precipitated by stress, sepsis, dehydration or

trauma; clinical features may be modified accordingly. In patients with

known adrenal insufficiency, nonadherence with therapy, inappropriate

cortisol dose reduction or lack of stress related cortisol dose

adjustment can cause adrenal crisis.

11

When should I consider Addison

disease?

Addison disease can manifest with adrenal crisis. Chronic symptoms

result from cortisol deficiency, aldosterone deficiency and excess ACTH:

cortisol deficiency results in weakness (99%), fatigue, weight loss

(97%), anorexia progressing to nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea (20%),

constipation (19%), flank or abdominal pain (34%), low blood

glucose levels and hyperthermia.

2,4,5

Fasting hypoglycaemia is

common and occurs because of loss of the gluconeogenic effects of

cortisol.

5

In patients with pre-existing type 1 diabetes, deterioration

of glycaemic control with recurrent hypoglycaemia can be the

presenting sign of adrenal insufficiency

2

aldosterone deficiency causes hyponatraemia, hyperkalaemia,

acidosis, tachycardia and hypotension. Low voltage

electrocardiogram (ECG) and a small heart on chest X-ray are

not necessarily present.

4,5

Suggestive symptoms are postural

hypotension and salt cravings

2,11

excess ACTH is only present in primary adrenal insufficiency. It

causes increased melanin production resulting in generalised

hyperpigmentation.

4,5

Because this resembles a suntan, it is

essential to inspect areas not exposed to the sun for diffuse

hyperpigmentation which can be more obvious in recent scars

and in areas such as the axillae, nipples, pressure points,

palmar creases, and mucous membranes. Some patients with

autoimmune mediated adrenal insufficiency also present with

vitiligo.

2,5

Chronic unrecognised Addison disease can cause psychiatric symptoms

such as memory impairment, confusion, apathy, depression and

psychosis.

5

These features regress on treatment with replacement

corticosteroids.

FOCUS

836 Reprinted from AUSTRALIAN FAMILY PHYSICIAN VOL. 39, NO. 11, NOVEMBER 2010

Addison disease diagnosis and initial management

5.5 mmol/L. He was given a bolus of 10% dextrose followed

by normal saline. He then had a generalised tonic clonic

seizure, was treated with anticonvulsants and intubated,

ventilated and transferred to the intensive care unit.

In his background history he had an admission at 11 months

of age with profound hypoglycaemia (BGL 0.6 mmol/L)

following an episode of gastroenteritis. He had presented to

the ED unresponsive and pale following 18 hours of profuse,

watery diarrhoea and vomiting. At that time, sodium was

recorded at 126 mmol/L with potassium 4.3 mmol/L. He

became alert and interactive after 10% dextrose bolus.

On the second admission, the boy was noted to have

hyperpigmentation of the buccal mucosa (Figure 1) and

appeared diffusely suntanned.

Plasma cortisol was <30 mmol/L with a raised ACTH of

492 pmol/L (normal range 2.010). A diagnosis of acute

Addisonian crisis was made and he was treated with 50 mg

IV hydrocortisone 4 hourly. He made a full recovery.

He was discharged on oral maintenance hydrocortisone

with an emergency plan. A MedicAlert bracelet and

ambulance cover were organised. Further investigations

revealed normal aldosterone levels, negative adrenal

Emergency plan

An up-to-date emergency plan and practical teaching in administering

emergency medication are of paramount importance. At each

consultation the physician must ensure that the patient and carer(s)

are well versed in the emergency plan and that their ready-to-use vial

of emergency hydrocortisone is in-date and available for use at any

time.

11,14

In growing children, the dose may require adjustment and a

new appropriate prescription should be issued where indicated. It is

recommended that patients wear a MedicAlert bracelet or pendant and

have ambulance cover.

Case study 1 An acute presentation

Paramedics attended a boy, aged 21 months, at his home. His

Glasgow Coma Scale was 8/15. He was poorly perfused, with

Sp0

2

of 76% and capillary blood glucose <2 mmol/L. He had

been unwell at home with symptoms of an upper respiratory

tract infection for the previous 24 hours. He was given oral

glucose gel and IM glucagon with no effect. On arrival at

the hospital emergency department he had spontaneous

respirations with a heart rate of 126 bpm and cool peripheries.

Investigations showed a metabolic acidosis, blood glucose

level (BGL) of 1.6 mmol/L, sodium 134 mmol/L and potassium

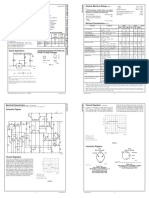

Table 1. Summary of the management and prevention of acute adrenal insufciency

5,11,14

Clinical findings

Cortisol deficiency: weakness, anorexia, nausea

and/or vomiting, hypoglycaemia, hypotension

(particularly postural) and shock

Aldosterone deficiency: dehydration, hyperkalaemia,

hyponatraemia, acidosis, low blood pressure

Investigations

Blood sugar level; serum glucose, urea, sodium and

potassium; blood gas analysis

Keep extra blood for analysis of ACTH and cortisol

if possible

Do not wait for results to start therapy

Intravenous fluids

Initial fluid resuscitation: NaCl 0.9% 20 mL/kg (severe

dehydration); 10 mL/kg (moderate dehydration)

repeat until circulation restored

Maintenance fluids: 510% dextrose

Steroid replacement (hydrocortisone)

If intravenous (IV) access is difficult, give

intramuscularly (IM) while establishing IV line

Neonates (1 year): 25 mg stat, then 1025 mg

46 hourly

Toddlers (13 years): 2550 mg stat, then 2550 mg

46 hourly

Children (412 years): 5075 mg stat, then 5075 mg

46 hourly

Adolescents and adults: 100150 mg stat, then 100 mg

46 hourly

Correction of hypoglycaemia

Neonates or infants: 10% dextrose 5 mL/kg (IV bolus)

Older children, adolescents and adults: 25% dextrose

2 mL/kg (IV bolus)

Correction of hyperkalaemia

Potassium usually normalises with fluid and electrolyte

replacement

If K+ >6 mmol/L perform ECG and apply cardiac monitor

as arrhythmias and cardiac arrest may occur

Identify and treat potential precipitating causes

Admit to appropriate inpatient facility

When patient tolerates oral intake

Reduce IV hyrocortisone dose, then switch to triple

dose oral hydrocortisone therapy, gradually reducing to

maintenance levels (1015 mg/m

2

/day)

Patients with aldosterone deficiency: start fludrocortisone

at maintenance doses (usually 0.1 mg/day)

11

Prevention

Emergency plan for susceptible patients, emergency

identification (MedicAlert)

Triple normal oral maintenance dose for 23 days during

stress (ie. fever, fracture)

Administer IM hydrocortisone if oral medication not

tolerated (eg. vomiting)

Increase parenteral hydrocortisone (12 mg/kg) before

anaesthesia, consider increased dose postoperatively

Ensure patients have ambulance cover and ready-to-use

IM hydrocortisone preparation (Act-o-vial

) for emergencies

FOCUS

Reprinted from AUSTRALIAN FAMILY PHYSICIAN VOL. 39, NO. 11, NOVEMBER 2010 837

Addison disease diagnosis and initial management

Why is Addison disease easily missed?

Addison disease is easily missed due to nonspecific symptoms and

presentations, rarity of the condition, and low index of suspicion.

The consequences of delayed diagnosis and treatment are increased

morbidity, mortality and medicolegal risk.

12,13

Outcomes may be

improved with a higher index of diagnostic suspicion, prompt emergency

management with IM or IV hydrocortisone as indicated, early referral,

and good patient education.

11,13

Key points in management

Physical findings are subtle and nonspecific; hyperpigmentation

may be seen, particularly in sun exposed areas or pressure points.

Circulatory compromise can range from mild signs of sodium and

volume depletion to shock.

If in doubt give oral/IM/IV hydrocortisone.

Dont delay treatment while awaiting laboratory results.

Authors

Susan OConnell MB, MRCPI, MD, is Fellow in Paediatric

Endocrinology, Princess Margaret Hospital for Children, Western

Australia. susanmary.oconnell@health.wa.gov.au

Aris Siafarikas MD, FRACP, is Consultant Paediatric Endocrinologist,

Princess Margaret Hospital for Children, Clinical Associate Professor,

Institute of Health and Rehabilitation Research, University of Notre

Dame, and Senior Clinical Lecturer, School of Paediatrics and Child

Health, University of Western Australia, Perth, Western Australia.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

References

1. Addison T, editor. On the constitutional and local effects of disease of the supra-

renal capsules. London: Highley, 1855.

2. Arlt W, Allolio B. Adrenal insufficiency. Lancet 2003;361:188193.

3. Laureti S, Vecchi L, Santeusanio F, et al. Is the prevalence of Addisons disease

underestimated? J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1999;84:1762.

4. Brook GD, Brown RS, editors. Handbook of clinical pediatric endocrinology. 1st

edn. Malden, Mass: Blackwell Publishing, 2008.

5. Kronenburg, editor. Williams textbook of endocrinology. 11th edn. Philadelphia:

Saunders Elsevier, 2008.

6. Oelkers W. Adrenal insufficiency. N Engl J Med 1996;335:120612.

7. Soule S. Addisons disease in Africa a teaching hospital experience. Clin

Endocrinol (Oxf) 1999;50:11520.

8. Perry R, Kecha O, Paquette J, et al. Primary adrenal insufficiency in children:

twenty years experience at the Sainte-Justine Hospital, Montreal. J Clin

Endocrinol Metab 2005;90:324350.

9. Ahonen P, Myllarniemi S, Sipila I, et al. Clinical variation of autoimmune

polyendocrinopathy-candidiasis-ectodermal dystrophy (APECED) in a series of 68

patients. N Engl J Med 1990;322:182936.

10. Greenfield JR, Samaras K. Suppression of HPA axis in adults taking inhaled corti-

costeroids. Thorax 2006;61:2723.

11. Arlt W. The approach to the adult with newly diagnosed adrenal insufficiency. J

Clin Endocrinol Metab 2009;94:105967.

12. Klauer KM. Adrenal insufficiency and adrenal crisis: differential diagnoses and

workup, 2009. Available at http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/765753-

diagnosis [Accessed 21 October 2010].

13. Erichsen MM, Lovas K, Fougner KJ, et al. Normal overall mortality rate in

Addisons disease, but young patients are at risk of premature death. Eur J

Endocrinol 2009;160:2337.

14. The Royal Childrens Hospital Melbourne. Adrenal crisis. 2010. Available at

www.rch.org.au/clinicalguide/cpg.cfm?doc_id=5121 [Accessed 24 June 2010].

15. Nieman L. Patient information: adrenal insufficiency (Addisons disease).

UpToDate, (internet serial), 2010.

16. Grant DB, Barnes ND, Moncrieff MW, et al. Clinical presentation, growth, and

pubertal development in Addisons disease. Arch Dis Child 1985;60:9258.

antibodies and normal, very long chain fatty acids (to

exclude adrenoleukodystrophy). Investigations to exclude

other endocrinopathies were normal, and no cause for

Addison disease identified.

Ongoing management

Ongoing management in this boy includes oral

hydrocortisone maintenance treatment and growth

monitoring. An emergency plan with instructions to increase

his dose of hydrocortisone in the event of illness is in place.

In the event of unresponsiveness or persistent vomiting his

parents have been instructed on the administration of IM

hydrocortisone and to call the emergency numbers listed

on the emergency plan. The importance of adherence with

regular medications is reiterated and the boys emergency

plan reviewed at each clinic attendance.

Case study 2 Issues in management

A girl, 15 years of age, with a diagnosis of Addison disease

made 3 years previously (anti-adrenal antibodies positive)

attended her routine endocrinology clinic appointment with

her father. She had a history of poor adherence. Regular

medications were: prednisolone 4 mg morning and evening

and fludrocortisone 100 g/day. She denied missing her

medications. She had regular menses. She described fair

energy levels.

On examination she looked well but appeared diffusely

suntanned, not confined to, but more obvious in sun

exposed areas. Her BP was normal. Records showed that

she had not gained weight for the past year.

The patient was intermittently living between her parents

homes. On review of her emergency plan she was unsure

of what to do should she become unwell. Her father

appeared to be well informed in the management of any

illness, however it was revealed that the ready-to-use IM

hydrocortisone was only available at her mothers house.

New prescriptions for IM hydrocortisone were issued for

both homes and for school, and copies of the emergency

plan were also made. The importance of adherence with

regular medication was reiterated.

Figure 1. Hyperpigmentation of the buccal mucosa

Você também pode gostar

- Addison Disease: Diagnosis and Initial ManagementDocumento5 páginasAddison Disease: Diagnosis and Initial ManagementI Gede SubagiaAinda não há avaliações

- Adrenal InsufficiencyDocumento11 páginasAdrenal InsufficiencyAustine OsaweAinda não há avaliações

- Jurnal Krisis AdrenalDocumento4 páginasJurnal Krisis AdrenalMelda IndrawatiAinda não há avaliações

- Causes of Diffuse Hyperpigmentation EndocrinopathiesDocumento9 páginasCauses of Diffuse Hyperpigmentation EndocrinopathiesAbdul QuyyumAinda não há avaliações

- MRCPass Notes For MRCP 1 - EnDOCRINOLOGYDocumento12 páginasMRCPass Notes For MRCP 1 - EnDOCRINOLOGYsabdali100% (1)

- Your Online Nursing Notes : Addison'S Disease Basic InfoDocumento4 páginasYour Online Nursing Notes : Addison'S Disease Basic InfoseigelysticAinda não há avaliações

- Addison's DseDocumento9 páginasAddison's DseKath RubioAinda não há avaliações

- Adrenocortical DisordersDocumento73 páginasAdrenocortical DisordersReunita ConstantiaAinda não há avaliações

- Adrenal Insufficiency: DR - Abbas Mansour Senior Consultant Internal MedicineDocumento24 páginasAdrenal Insufficiency: DR - Abbas Mansour Senior Consultant Internal Medicineraed faisalAinda não há avaliações

- Adrenal Diseases: Types Aetiology Diagnosis Complications TreatmentDocumento29 páginasAdrenal Diseases: Types Aetiology Diagnosis Complications Treatmentgani7222Ainda não há avaliações

- Wernicke Encephalopathy: EtiologyDocumento6 páginasWernicke Encephalopathy: EtiologyDrhikmatullah SheraniAinda não há avaliações

- Adrenal Gland DisordersDocumento31 páginasAdrenal Gland DisordersThe AbyssinicansAinda não há avaliações

- Insuficiencia AdrenalDocumento5 páginasInsuficiencia AdrenalLuciana RafaelAinda não há avaliações

- Endocrinology NotesDocumento12 páginasEndocrinology Notesrandiey john abelleraAinda não há avaliações

- Adrenal Gland: Adrenal Insufficiency, Addison Disease, Cushing SyndromeDocumento46 páginasAdrenal Gland: Adrenal Insufficiency, Addison Disease, Cushing Syndromeyuyu tuptupAinda não há avaliações

- Addisons DiseaseDocumento12 páginasAddisons DiseaseChinju CyrilAinda não há avaliações

- AddisonsdiseaseDocumento5 páginasAddisonsdiseasenessimmounir1173Ainda não há avaliações

- 6 Mary Lou Sole, Deborah Goldenberg Klein, Marthe J. Moseley - EndokrinDocumento56 páginas6 Mary Lou Sole, Deborah Goldenberg Klein, Marthe J. Moseley - EndokrinyaminmuhAinda não há avaliações

- Thyroid Disorder NCPDocumento9 páginasThyroid Disorder NCPKen RegalaAinda não há avaliações

- Adrenal Crisis: Risk FactorsDocumento25 páginasAdrenal Crisis: Risk Factorspwinzizitah063Ainda não há avaliações

- Adrenal Insufficiency in The Intensive Care Unit: Samir El Ansary Icu Professor Ain Shams CairoDocumento49 páginasAdrenal Insufficiency in The Intensive Care Unit: Samir El Ansary Icu Professor Ain Shams CairoGebby MamuayaAinda não há avaliações

- Adrenal CrisisDocumento4 páginasAdrenal CrisisRichie Marie BajaAinda não há avaliações

- Cushings, Addisons and Acromegaly: DR J Storrow FY2Documento38 páginasCushings, Addisons and Acromegaly: DR J Storrow FY2abdalkhalidAinda não há avaliações

- ENDO - Adrenal CrisisDocumento8 páginasENDO - Adrenal CrisisHajime NakaegawaAinda não há avaliações

- Tanpa JudulDocumento14 páginasTanpa JudulAsrapia HubaisyingAinda não há avaliações

- Endocrinology Course Content: Semester (5) Clinical Pharmacy CourseDocumento91 páginasEndocrinology Course Content: Semester (5) Clinical Pharmacy CourseSadigMukhAinda não há avaliações

- Subclinical Hyperthyroidism Case ReportDocumento26 páginasSubclinical Hyperthyroidism Case ReportkapanjddokterAinda não há avaliações

- 22 MetabolicEncephalopathies FinalDocumento19 páginas22 MetabolicEncephalopathies FinalShravan BimanapalliAinda não há avaliações

- Autoimmune Polyglandular Syndrome ReviewDocumento3 páginasAutoimmune Polyglandular Syndrome ReviewIan AlvaradoAinda não há avaliações

- Adrenal Crisis FinalDocumento10 páginasAdrenal Crisis FinalAmanda Scarlet100% (1)

- REPORTDocumento13 páginasREPORTEarlou MagbanuaAinda não há avaliações

- Addison's DiseaseDocumento3 páginasAddison's Diseaseavinash dhameriyaAinda não há avaliações

- Endocrinology Teaching CasesDocumento47 páginasEndocrinology Teaching CasesBinta BaptisteAinda não há avaliações

- EndokrinDocumento27 páginasEndokrinSarah Putri AbellysaAinda não há avaliações

- Canine Hypoadrenocorticism Overvew Diagnosis and Treatment LolattiDocumento6 páginasCanine Hypoadrenocorticism Overvew Diagnosis and Treatment LolattiAna Clara SevasteAinda não há avaliações

- 20 Endocrine Disease and AnaesthesiaDocumento0 página20 Endocrine Disease and AnaesthesiajuniorebindaAinda não há avaliações

- 2 Bvab048.1976Documento1 página2 Bvab048.1976Anca LunguAinda não há avaliações

- Case Study: MYXEDEMATOUS COMADocumento5 páginasCase Study: MYXEDEMATOUS COMAjisooAinda não há avaliações

- Adrenal Senior 1Documento12 páginasAdrenal Senior 1mohammad saifuddinAinda não há avaliações

- Stunted Growth: Addison DiseaseDocumento32 páginasStunted Growth: Addison DiseaseAshim AbhiAinda não há avaliações

- ENDOCRINE DISORDERS (Autosaved)Documento81 páginasENDOCRINE DISORDERS (Autosaved)Princewill SeiyefaAinda não há avaliações

- Adrenal and Pitutary Disoreders Adigrat LecDocumento144 páginasAdrenal and Pitutary Disoreders Adigrat Lecbereket gashuAinda não há avaliações

- Addison's Disease:: Clinical IntelligenceDocumento3 páginasAddison's Disease:: Clinical Intelligencemira tianiAinda não há avaliações

- Adrenal InsufficiencyDocumento2 páginasAdrenal InsufficiencyTracy NwanneAinda não há avaliações

- Flashcards - QuizletDocumento7 páginasFlashcards - QuizletNEsreAinda não há avaliações

- Addison DiseaseDocumento23 páginasAddison DiseaseKompari EvansAinda não há avaliações

- Pituitary &thyroid NotesDocumento7 páginasPituitary &thyroid NotesAli salimAinda não há avaliações

- Addison's DiseaseDocumento15 páginasAddison's DiseaseRonald A. Ogania50% (4)

- NCMB316 Rle 2-10-7addison's DiseaseDocumento4 páginasNCMB316 Rle 2-10-7addison's DiseaseMaica LectanaAinda não há avaliações

- Parathyroid DisordersDocumento44 páginasParathyroid DisordersBIAN ALKHAZMARIAinda não há avaliações

- Research Paper On Addisons DiseaseDocumento8 páginasResearch Paper On Addisons Diseasetug0l0byh1g2100% (1)

- Geriatric Anesthesia & Analgesia: ComplicationsDocumento4 páginasGeriatric Anesthesia & Analgesia: ComplicationsWilly Victorio CisnerosAinda não há avaliações

- adrenal presentation - صیادیDocumento39 páginasadrenal presentation - صیادیRazyAinda não há avaliações

- Summary of Medical EmergenciesDocumento24 páginasSummary of Medical Emergenciesbasharswork99Ainda não há avaliações

- Addisonian Crisis: Manish K Medical Officer IgmhDocumento47 páginasAddisonian Crisis: Manish K Medical Officer IgmhNaaz Delhiwale100% (1)

- Reye'S Syndrome: Mrs. Smitha.M Associate Professor Vijaya College of Nursing KottarakkaraDocumento7 páginasReye'S Syndrome: Mrs. Smitha.M Associate Professor Vijaya College of Nursing KottarakkarakrishnasreeAinda não há avaliações

- Endocrine DiseasesDocumento64 páginasEndocrine DiseasesshobanaaaradhanaAinda não há avaliações

- Thyrotoxicosis Ischaemic Heart Disease Hypertension Alcohol Excess Lone Atrial FibrillationDocumento5 páginasThyrotoxicosis Ischaemic Heart Disease Hypertension Alcohol Excess Lone Atrial FibrillationZhao Xuan TanAinda não há avaliações

- 351 UN 1824 Sodium Hydroxide SolutionDocumento8 páginas351 UN 1824 Sodium Hydroxide SolutionCharls DeimoyAinda não há avaliações

- Celltac MEK 6500Documento3 páginasCelltac MEK 6500RiduanAinda não há avaliações

- Presentasi Evaluasi Manajemen Risiko - YLYDocumento16 páginasPresentasi Evaluasi Manajemen Risiko - YLYOPERASIONALAinda não há avaliações

- Withania DSC PDFDocumento6 páginasWithania DSC PDFEfsha KhanAinda não há avaliações

- Qualitative Tests Organic NotesDocumento5 páginasQualitative Tests Organic NotesAdorned. pearlAinda não há avaliações

- Ams - 4640-C63000 Aluminium Nickel MNDocumento3 páginasAms - 4640-C63000 Aluminium Nickel MNOrnella MancinelliAinda não há avaliações

- Sociology/Marriage PresentationDocumento31 páginasSociology/Marriage PresentationDoofSadAinda não há avaliações

- PMEGP Revised Projects (Mfg. & Service) Vol 1Documento260 páginasPMEGP Revised Projects (Mfg. & Service) Vol 1Santosh BasnetAinda não há avaliações

- (ISPS Book Series) Yrjö O. Alanen, Manuel González de Chávez, Ann-Louise S. Silver, Brian Martindale - Psychotherapeutic Approaches To Schizophrenic Psychoses - Past, Present and Future-Routledge (20Documento419 páginas(ISPS Book Series) Yrjö O. Alanen, Manuel González de Chávez, Ann-Louise S. Silver, Brian Martindale - Psychotherapeutic Approaches To Schizophrenic Psychoses - Past, Present and Future-Routledge (20Manuel100% (1)

- Women and International Human Rights Law PDFDocumento67 páginasWomen and International Human Rights Law PDFakilasriAinda não há avaliações

- GeoSS Event Seminar 12 July 2012 - SlidesDocumento15 páginasGeoSS Event Seminar 12 July 2012 - SlidesNurmanda RamadhaniAinda não há avaliações

- 2008 03 20 BDocumento8 páginas2008 03 20 BSouthern Maryland OnlineAinda não há avaliações

- Additional Activity 3 InsciDocumento3 páginasAdditional Activity 3 InsciZophia Bianca BaguioAinda não há avaliações

- Shoulder Joint Position Sense Improves With ElevationDocumento10 páginasShoulder Joint Position Sense Improves With ElevationpredragbozicAinda não há avaliações

- HDFC Life Insurance (HDFCLIFE) : 2. P/E 58 3. Book Value (RS) 23.57Documento5 páginasHDFC Life Insurance (HDFCLIFE) : 2. P/E 58 3. Book Value (RS) 23.57Srini VasanAinda não há avaliações

- Defects Lamellar TearingDocumento6 páginasDefects Lamellar Tearingguru_terexAinda não há avaliações

- Cataloge ICARDocumento66 páginasCataloge ICARAgoess Oetomo100% (1)

- Vocab PDFDocumento29 páginasVocab PDFShahab SaqibAinda não há avaliações

- LM 337Documento4 páginasLM 337matias robertAinda não há avaliações

- NASA ISS Expedition 2 Press KitDocumento27 páginasNASA ISS Expedition 2 Press KitOrion2015Ainda não há avaliações

- Ethnomedicinal Plants For Indigestion in Uthiramerur Taluk Kancheepuram District Tamilnadu IndiaDocumento8 páginasEthnomedicinal Plants For Indigestion in Uthiramerur Taluk Kancheepuram District Tamilnadu IndiaGladys DjeugaAinda não há avaliações

- Pescatarian Mediterranean Diet Cookbook 2 - Adele TylerDocumento98 páginasPescatarian Mediterranean Diet Cookbook 2 - Adele Tylerrabino_rojoAinda não há avaliações

- Allison Weech Final ResumeDocumento1 páginaAllison Weech Final Resumeapi-506177291Ainda não há avaliações

- Indirect Current Control of LCL Based Shunt Active Power FilterDocumento10 páginasIndirect Current Control of LCL Based Shunt Active Power FilterArsham5033Ainda não há avaliações

- Cisco - Level 45Documento1 páginaCisco - Level 45vithash shanAinda não há avaliações

- Leave of Absence Form (Rev. 02 072017)Documento1 páginaLeave of Absence Form (Rev. 02 072017)KIMBERLY BALISACANAinda não há avaliações

- Material: Safety Data SheetDocumento3 páginasMaterial: Safety Data SheetMichael JoudalAinda não há avaliações

- 1 Stra Bill FinalDocumento41 páginas1 Stra Bill FinalRajesh JhaAinda não há avaliações

- R. Nishanth K. VigneswaranDocumento20 páginasR. Nishanth K. VigneswaranAbishaTeslinAinda não há avaliações

- Ergo 1 - Workshop 3Documento3 páginasErgo 1 - Workshop 3Mugar GeillaAinda não há avaliações