Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Ancient Greece

Enviado por

aquel1983Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Ancient Greece

Enviado por

aquel1983Direitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

9/11/2014 Ancient Greece - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ancient_Greece 1/15

The Parthenon, a temple

dedicated to Athena, located on

the Acropolis in Athens, is one of

the most representative symbols

of the culture and sophistication

of the ancient Greeks.

Ancient Greece

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Ancient Greece was a Greek civilization belonging to a period of Greek history that lasted

from the Archaic period of the 8th to 6th centuries BC to the end of antiquity (ca. AD 600).

Immediately following this period was the beginning of the Early Middle Ages and the

Byzantine era.

[1]

Included in ancient Greece is the period of Classical Greece, which flourished

during the 5th to 4th centuries BC. Classical Greece began with the repelling of a Persian

invasion by Athenian leadership. Because of conquests by Alexander the Great, Hellenistic

civilization flourished from Central Asia to the western end of the Mediterranean Sea.

Classical Greek culture, especially philosophy, had a powerful influence on the Roman Empire,

which carried a version of it to many parts of the Mediterranean Basin and Europe, for which

reason Classical Greece is generally considered to be the seminal culture which provided the

foundation of modern Western culture.

[2][3][4][5]

Contents

1 Chronology

2 Historiography

3 History

3.1 Archaic period

3.2 Classical Greece

3.2.1 5th century

3.2.2 4th century

3.3 Hellenistic Greece

3.4 Roman Greece

4 Geography

4.1 Regions

4.2 Colonies

5 Politics and society

5.1 Political structure

5.2 Government and law

5.3 Social structure

5.4 Education

5.5 Economy

5.6 Warfare

6 Culture

6.1 Philosophy

6.2 Literature and theatre

6.3 Music and dance

6.4 Science and technology

6.5 Art and architecture

6.6 Religion and mythology

9/11/2014 Ancient Greece - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ancient_Greece 2/15

7 Legacy

8 See also

9 References

10 Further reading

11 External links

Chronology

Classical Antiquity in the Mediterranean region is commonly considered to have begun in the 8th century BC (around the time of the

earliest recorded poetry of Homer) and ended in the 6th century AD.

Classical Antiquity in Greece is preceded by the Greek Dark Ages (c. 1200 c. 800 BC), archaeologically characterised by the

protogeometric and geometric styles of designs on pottery. This period is succeeded, around the 8th century BC, by the Orientalizing

Period during which a strong influence of Syro-Hittite, Assyrian, Phoenician and Egyptian cultures becomes apparent. Traditionally,

the Archaic period of ancient Greece is considered to begin with Orientalizing influence, which among other things brought the

alphabetic script to Greece, marking the beginning of Greek literature (Homer, Hesiod). The end of the Dark Ages is also frequently

dated to 776 BC, the year of the first Olympic Games.

[6]

The Archaic period gives way to the Classical period around 500 BC, in

turn succeeded by the Hellenistic period at the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC.

Ancient Periods

Astronomical year numbering

Dates are approximate, consult particular article for details

The history of Greece during Classical Antiquity may thus be subdivided into the following periods:

[7]

The Archaic period (c. 800 c. 500 BC), in which artists made larger free-standing sculptures in stiff, hieratic poses with the

dreamlike "archaic smile". The Archaic period is often taken to end with the overthrow of the last tyrant of Athens and the start

of Athenian Democracy in 508 BC.

The Classical period (c. 500 323 BC) is characterised by a style which was considered by later observers to be exemplary

i.e. "classical", as shown in for instance the Parthenon. Politically, the Classical Period was dominated by Athens and the

Delian League during the 5th century, but displaced by Spartan hegemony during the early 4th century BC, before power

shifted to Thebes and the Boeotian League and finally to the League of Corinth led by Macedon.

In the Hellenistic period (323146 BC) Greek culture and power expanded into the Near and Middle East. This period begins

with the death of Alexander and ends with the Roman conquest.

Roman Greece, the period between Roman victory over the Corinthians at the Battle of Corinth in 146 BC and the

establishment of Byzantium by Constantine as the capital of the Roman Empire in AD 330.

The final phase of Antiquity is the period of Christianization during the later 4th to early 6th centuries AD, sometimes taken to

be complete with the closure of the Academy of Athens by Justinian I in 529.

[8]

Historiography

9/11/2014 Ancient Greece - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ancient_Greece 3/15

Dipylon Vase of the late Geometric

period, or the beginning of the

Archaic period, ca. 750 BC.

Political geography of ancient Greece

in the Archaic and Classical periods

The historical period of ancient Greece is unique in world history as the first period attested directly in proper historiography, while

earlier ancient history or proto-history is known by much more circumstantial evidence, such as annals or king lists, and pragmatic

epigraphy.

Herodotus is widely known as the "father of history": his Histories are eponymous of the entire field. Written between the 450s and

420s BC, Herodotus' work reaches about a century into the past, discussing 6th century historical figures such as Darius I of Persia,

Cambyses II and Psamtik III, and alluding to some 8th century ones such as Candaules.

Herodotus was succeeded by authors such as Thucydides, Xenophon, Demosthenes, Plato and Aristotle. Most of these authors

were either Athenians or pro-Athenians, which is why far more is known about the history and politics of Athens than those of many

other cities. Their scope is further limited by a focus on political, military and diplomatic history, ignoring economic and social

history.

[9]

History

Archaic period

In the 8th century BC, Greece began to emerge from the Dark Ages which followed the

fall of the Mycenaean civilization. Literacy had been lost and Mycenaean script forgotten,

but the Greeks adopted the Phoenician alphabet, modifying it to create the Greek alphabet.

From about the 9th century BC written records begin to appear.

[10]

Greece was divided

into many small self-governing communities, a pattern largely dictated by Greek geography:

every island, valley and plain is cut off from its neighbours by the sea or mountain

ranges.

[11]

The Lelantine War (c.710c.650 BC) is the earliest documented war of the ancient Greek

period. It was fought between the important poleis (city-states) of Chalcis and Eretria over

the fertile Lelantine plain of Euboea. Both cities seem to have suffered a decline as result of

the long war, though Chalcis was the nominal victor.

A mercantile class arose in the first half of the 7th century, shown by the introduction of

coinage in about 680 BC.

[12]

This seems to have introduced tension to many city-states.

The aristocratic regimes which generally governed the poleis were threatened by the new-

found wealth of merchants, who in turn desired political power. From 650 BC onwards,

the aristocracies had to fight not to be overthrown and replaced by populist tyrants. This

word derives from the non-pejorative Greek tyrannos, meaning 'illegitimate

ruler', and was applicable to both good and bad leaders alike.

[13][14]

A growing population and a shortage of land also seem to have created internal strife

between the poor and the rich in many city-states. In Sparta, the Messenian Wars resulted

in the conquest of Messenia and enserfment of the Messenians, beginning in the latter half

of the 8th century BC, an act without precedent or antecedent in ancient Greece. This

practice allowed a social revolution to occur.

[15]

The subjugated population, thenceforth

known as helots, farmed and laboured for Sparta, whilst every Spartan male citizen became a soldier of the Spartan Army in a

permanently militarized state. Even the elite were obliged to live and train as soldiers; this commonality between rich and poor citizens

served to defuse the social conflict. These reforms, attributed to the shadowy Lycurgus of Sparta, were probably complete by 650

BC.

Athens suffered a land and agrarian crisis in the late 7th century, again resulting in civil strife. The Archon (chief magistrate) Draco

made severe reforms to the law code in 621 BC (hence "draconian"), but these failed to quell the conflict. Eventually the moderate

reforms of Solon (594 BC), improving the lot of the poor but firmly entrenching the aristocracy in power, gave Athens some stability.

9/11/2014 Ancient Greece - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ancient_Greece 4/15

A map showing the Greek territories

and colonies during the Archaic

period.

Early Athenian coin, depicting the

head of Athena on the obverse and

her owl on the reverse5th century

BC

By the 6th century BC several cities had emerged as dominant in Greek affairs: Athens, Sparta, Corinth, and Thebes. Each of them

had brought the surrounding rural areas and smaller towns under their control, and Athens and Corinth had become major maritime

and mercantile powers as well.

Rapidly increasing population in the 8th and 7th centuries had resulted in emigration of

many Greeks to form colonies in Magna Graecia (Southern Italy and Sicily), Asia Minor

and further afield. The emigration effectively ceased in the 6th century by which time the

Greek world had, culturally and linguistically, become much larger than the area of present-

day Greece. Greek colonies were not politically controlled by their founding cities, although

they often retained religious and commercial links with them.

The emigration process also determined a long series of conflicts between the Greek cities

of Sicily, especially Syracuse, and the Carthaginians. These conflicts lasted from 600 BC to

265 BC when Rome entered into an alliance with the Mamertines to fend off the hostilities

by the new tyrant of Syracuse, Hiero II and then the Carthaginians. This way Rome became the new dominant power against the

fading strength of the Sicilian Greek cities and the Carthaginian supremacy in the region. One year later the First Punic War erupted.

In this period, there was huge economic development in Greece, and also in its overseas colonies which experienced a growth in

commerce and manufacturing. There was a great improvement in the living standards of the population. Some studies estimate that the

average size of the Greek household, in the period from 800 BC to 300 BC, increased five times, which indicates a large increase in

the average income of the population.

In the second half of the 6th century, Athens fell under the tyranny of Peisistratos and then of his sons Hippias and Hipparchos.

However, in 510 BC, at the instigation of the Athenian aristocrat Cleisthenes, the Spartan king Cleomenes I helped the Athenians

overthrow the tyranny. Afterwards, Sparta and Athens promptly turned on each other, at which point Cleomenes I installed Isagoras

as a pro-Spartan archon. Eager to prevent Athens from becoming a Spartan puppet, Cleisthenes responded by proposing to his

fellow citizens that Athens undergo a revolution: that all citizens share in political power, regardless of status: that Athens become a

"democracy". So enthusiastically did the Athenians take to this idea that, having overthrown Isagoras and implemented Cleisthenes's

reforms, they were easily able to repel a Spartan-led three-pronged invasion aimed at restoring Isagoras.

[16]

The advent of the

democracy cured many of the ills of Athens and led to a 'golden age' for the Athenians.

Classical Greece

5th century

Athens and Sparta would soon have to become allies in the face of the largest external

threat ancient Greece would see until the Roman conquest. After suppressing the Ionian

Revolt, a rebellion of the Greek cities of Ionia, Darius I of Persia, King of Kings of the

Achaemenid Empire, decided to subjugate Greece. His invasion in 490 BC was ended by

the Athenian victory at the Battle of Marathon under Miltiades the Younger.

Xerxes I of Persia, son and successor of Darius I, attempted his own invasion 10 years

later, but despite his larger army he suffered heavy casualties after the famous rearguard

action at Thermopylae and victories for the allied Greeks at the Battles of Salamis and

Plataea. The Greco-Persian Wars continued until 449 BC, led by the Athenians and their

Delian League, during which time the Macedon, Thrace, the Aegean Islands and Ionia were all liberated from Persian influence.

The dominant position of the maritime Athenian 'Empire' threatened Sparta and the Peloponnesian League of mainland Greek cities.

Inevitably, this led to conflict, resulting in the Peloponnesian War (431-404 BC). Though effectively a stalemate for much of the war,

Athens suffered a number of setbacks. The Plague of Athens in 430 BC followed by a disastrous military campaign known as the

Sicilian Expedition severely weakened Athens. Around thirty per cent of the population died in a typhoid epidemic in 430-426

B.C..

[17]

9/11/2014 Ancient Greece - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ancient_Greece 5/15

Attic red-figure pottery, kylix by the

Triptolemos Painter, ca. 480 BC

(Paris, Louvre)

Delian League ("Athenian Empire"), immediately

before the Peloponnesian War in 431 BC

Sparta was able to foment rebellion amongst Athens's allies, further reducing the Athenian

ability to wage war. The decisive moment came in 405 BC when Sparta cut off the grain

supply to Athens from the Hellespont. Forced to attack, the crippled Athenian fleet was

decisively defeated by the Spartans under the command of Lysander at Aegospotami. In

404 BC Athens sued for peace, and Sparta dictated a predictably stern settlement: Athens

lost her city walls (including the Long Walls), her fleet, and all of her overseas possessions.

4th century

Greece thus entered the 4th century under a Spartan hegemony, but it was clear from the

start that this was weak. A demographic crisis meant Sparta was overstretched, and by

395 BC Athens, Argos, Thebes, and Corinth felt able to challenge Spartan dominance,

resulting in the Corinthian War (395-387 BC). Another war of stalemates, it ended with

the status quo restored, after the threat of Persian intervention on behalf of the Spartans.

The Spartan hegemony lasted another 16 years, until, when attempting to

impose their will on the Thebans, the Spartans suffered a decisive defeat at

Leuctra in 371 BC. The Theban general Epaminondas then led Theban

troops into the Peloponnese, whereupon other city-states defected from the

Spartan cause. The Thebans were thus able to march into Messenia and free

the population.

Deprived of land and its serfs, Sparta declined to a second-rank power. The

Theban hegemony thus established was short-lived; at the Battle of Mantinea

in 362 BC, Thebes lost its key leader, Epaminondas, and much of its

manpower, even though they were victorious in battle. In fact such were the

losses to all the great city-states at Mantinea that none could establish

dominance in the aftermath.

The weakened state of the heartland of Greece coincided with the Rise of

Macedon, led by Philip II. In twenty years, Philip had unified his kingdom,

expanded it north and west at the expense of Illyrian tribes, and then

conquered Thessaly and Thrace. His success stemmed from his innovative reforms to the Macedon army. Phillip intervened

repeatedly in the affairs of the southern city-states, culminating in his invasion of 338 BC.

Decisively defeating an allied army of Thebes and Athens at the Battle of Chaeronea (338 BC), he became de facto hegemon of all

of Greece, except Sparta. He compelled the majority of the city-states to join the League of Corinth, allying them to him, and

preventing them from warring with each other. Philip then entered into war against the Achaemenid Empire but was assassinated by

Pausanias of Orestis early on in the conflict.

Alexander, son and successor of Philip, continued the war. Alexander defeated Darius III of Persia and completely destroyed the

Achaemenid Empire, annexing it to Macedon and earning himself the epithet 'the Great'. When Alexander died in 323 BC, Greek

power and influence was at its zenith. However, there had been a fundamental shift away from the fierce independence and classical

culture of the poleisand instead towards the developing Hellenistic culture.

Hellenistic Greece

The Hellenistic period lasted from 323 BC, which marked the end of the Wars of Alexander the Great, to the annexation of Greece

by the Roman Republic in 146 BC. Although the establishment of Roman rule did not break the continuity of Hellenistic society and

culture, which remained essentially unchanged until the advent of Christianity, it did mark the end of Greek political independence.

During the Hellenistic period, the importance of "Greece proper" (that is, the territory of modern Greece) within the Greek-speaking

world declined sharply. The great centers of Hellenistic culture were Alexandria and Antioch, capitals of Ptolemaic Egypt and

Seleucid Syria respectively.

9/11/2014 Ancient Greece - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ancient_Greece 6/15

The major Hellenistic realms included the Diadochi

kingdoms:

Kingdom of Ptolemy I Soter

Kingdom of Cassander

Kingdom of Lysimachus

Kingdom of Seleucus I Nicator

Epirus

Also shown on the map:

Greek colonies

Carthage (non-Greek)

Rome (non-Greek)

The orange areas were often in dispute after 281

BC. The kingdom of Pergamon occupied some of

this area. Not shown: Indo-Greeks.

Territories and expansion of the Indo-

Greeks.

[18]

The conquests of Alexander had numerous consequences for the Greek city-

states. It greatly widened the horizons of the Greeks and led to a steady

emigration, particularly of the young and ambitious, to the new Greek empires

in the east.

[19]

Many Greeks migrated to Alexandria, Antioch and the many

other new Hellenistic cities founded in Alexander's wake, as far away as what

are now Afghanistan and Pakistan, where the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom and

the Indo-Greek Kingdom survived until the end of the 1st century BC.

After the death of Alexander his empire was, after quite some conflict,

divided amongst his generals, resulting in the Ptolemaic Kingdom (based upon

Egypt), the Seleucid Empire (based on the Levant, Mesopotamia and Persia)

and the Antigonid dynasty based in Macedon. In the intervening period, the

poleis of Greece were able to wrest back some of their freedom, although still

nominally subject to the Macedonian Kingdom.

The city-states formed themselves into two leagues; the Achaean League

(including Thebes, Corinth and Argos) and the Aetolian League (including

Sparta and Athens). For much of the period until the Roman conquest, these

leagues were usually at war with each other, and/or allied to different sides in

the conflicts between the Diadochi (the successor states to Alexander's

empire).

The Antigonid Kingdom became involved in a war with the Roman Republic

in the late 3rd century. Although the First Macedonian War was inconclusive,

the Romans, in typical fashion, continued to make war on Macedon until it

was completely absorbed into the Roman Republic (by 149 BC). In the east

the unwieldy Seleucid Empire gradually disintegrated, although a rump

survived until 64 BC, whilst the Ptolemaic Kingdom continued in Egypt until 30 BC, when

it too was conquered by the Romans. The Aetolian league grew wary of Roman

involvement in Greece, and sided with the Seleucids in the Roman-Syrian War; when the

Romans were victorious, the league was effectively absorbed into the Republic. Although

the Achaean league outlasted both the Aetolian league and Macedon, it was also soon

defeated and absorbed by the Romans in 146 BC, bringing an end to the independence of

all of Greece.

Roman Greece

The Greek peninsula came under Roman rule during the 146 BC conquest of Greece after

the Battle of Corinth. Macedonia became a Roman province while southern Greece came

under the surveillance of Macedonia's praefect; however, some Greek poleis managed to

maintain a partial independence and avoid taxation. The Aegean islands were added to this

territory in 133 BC. Athens and other Greek cities revolted in 88 BC, and the peninsula

was crushed by the Roman general Sulla. The Roman civil wars devastated the land even

further, until Augustus organized the peninsula as the province of Achaea in 27 BC.

Greece was a key eastern province of the Roman Empire, as the Roman culture had long been in fact Greco-Roman. The Greek

language served as a lingua franca in the East and in Italy, and many Greek intellectuals such as Galen would perform most of their

work in Rome.

Geography

Regions

9/11/2014 Ancient Greece - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ancient_Greece 7/15

Map showing the major regions of mainland

ancient Greece and adjacent "barbarian" lands.

Greek cities & colonies c. 550 BC.

The territory of Greece is mountainous, and as a result, ancient Greece consisted of many smaller regions each with its own dialect,

cultural peculiarities, and identity. Regionalism and regional conflicts were a

prominent feature of ancient Greece. Cities tended to be located in valleys

between mountains, or on coastal plains, and dominated a certain area around

them.

In the south lay the Peloponnese, itself consisting of the regions of Laconia

(southeast), Messenia (southwest), Elis (west), Achaia (north), Korinthia

(northeast), Argolis (east), and Arcadia (center). These names survive to the

present day as regional units of modern Greece, though with somewhat different

boundaries. Mainland Greece to the north, nowadays known as Central Greece,

consisted of Aetolia and Acarnania in the west, Locris, Doris, and Phocis in the

center, while in the east lay Boeotia, Attica, and Megaris. Northeast lay

Thessaly, while Epirus lay to the northwest. Epirus stretched from the Ambracian

Gulf in the south to the Ceraunian mountains and the Aoos river in the north, and

consisted of Chaonia (north), Molossia (center), and Thesprotia (south). In the

northeast corner was Macedonia,

[20]

originally consisting Lower Macedonia and

its regions, such as Elimeia, Pieria, and Orestis. Around the time of Alexander I

of Macedon, the Argead kings of Macedon started to expand into Upper

Macedonia, lands inhabited by independent Macedonian tribes like the

Lyncestae and the Elmiotae and to the West, beyond the Axius river, into

Eordaia, Bottiaea, Mygdonia, and Almopia, regions settled by Thracian

tribes.

[21]

To the north of Macedonia lay various non-Greek peoples such as the

Paeonians due north, the Thracians to the northeast, and the Illyrians, with whom the Macedonians were frequently in conflict, to the

northwest. Chalcidice was settled early on by southern Greek colonists and was considered part of the Greek world, while from the

late 2nd millennium BC substantial Greek settlement also occurred on the eastern shores of the Aegean, in Anatolia.

Colonies

During the Archaic period, the population of Greece grew beyond the capacity

of its limited arable land (according to one estimate, the population of ancient

Greece increased by a factor larger than ten during the period from 800 BC to

400 BC, increasing from a population of 800,000 to a total estimated population

of 10 to 13 million).

[22]

From about 750 BC the Greeks began 250 years of expansion, settling colonies

in all directions. To the east, the Aegean coast of Asia Minor was colonized first,

followed by Cyprus and the coasts of Thrace, the Sea of Marmara and south

coast of the Black Sea.

Eventually Greek colonization reached as far northeast as present day Ukraine

and Russia (Taganrog). To the west the coasts of Illyria, Sicily and Southern Italy were settled, followed by Southern France,

Corsica, and even northeastern Spain. Greek colonies were also founded in Egypt and Libya.

Modern Syracuse, Naples, Marseille and Istanbul had their beginnings as the Greek colonies Syracusae (), Neapolis

(), Massalia () and Byzantion (). These colonies played an important role in the spread of Greek

influence throughout Europe and also aided in the establishment of long-distance trading networks between the Greek city-states,

boosting the economy of ancient Greece.

Politics and society

Political structure

9/11/2014 Ancient Greece - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ancient_Greece 8/15

Cities and towns of ancient Greece

Inheritance law, part of the Law Code

of Gortyn, Crete, fragment of the

11th column. Limestone, 5th century

BC

Ancient Greece consisted of several hundred more or less independent city-states (poleis). This was a situation unlike that in most

other contemporary societies, which were either tribal or kingdoms ruling over

relatively large territories. Undoubtedly the geography of Greecedivided and sub-

divided by hills, mountains, and riverscontributed to the fragmentary nature of

ancient Greece. On the one hand, the ancient Greeks had no doubt that they were

"one people"; they had the same religion, same basic culture, and same language.

Furthermore, the Greeks were very aware of their tribal origins; Herodotus was able

to extensively categorise the city-states by tribe. Yet, although these higher-level

relationships existed, they seem to have rarely had a major role in Greek politics. The

independence of the poleis was fiercely defended; unification was something rarely

contemplated by the ancient Greeks. Even when, during the second Persian invasion

of Greece, a group of city-states allied themselves to defend Greece, the vast majority

of poleis remained neutral, and after the Persian defeat, the allies quickly returned to

infighting.

[23]

Thus, the major peculiarities of the ancient Greek political system were firstly, its

fragmentary nature, and that this does not particularly seem to have tribal origin, and

secondly, the particular focus on urban centres within otherwise tiny states. The

peculiarities of the Greek system are further evidenced by the colonies that they set up throughout the Mediterranean Sea, which,

though they might count a certain Greek polis as their 'mother' (and remain sympathetic to her), were completely independent of the

founding city.

Inevitably smaller poleis might be dominated by larger neighbours, but conquest or direct rule by another city-state appears to have

been quite rare. Instead the poleis grouped themselves into leagues, membership of which was in a constant state of flux. Later in the

Classical period, the leagues would become fewer and larger, be dominated by one city (particularly Athens, Sparta and Thebes);

and often poleis would be compelled to join under threat of war (or as part of a peace treaty). Even after Philip II of Macedon

"conquered" the heartlands of ancient Greece, he did not attempt to annex the territory, or unify it into a new province, but simply

compelled most of the poleis to join his own Corinthian League.

Government and law

Initially many Greek city-states seem to have been petty kingdoms; there was often a city

official carrying some residual, ceremonial functions of the king (basileus), e.g. the archon

basileus in Athens.

[24]

However, by the Archaic period and the first historical

consciousness, most had already become aristocratic oligarchies. It is unclear exactly how

this change occurred. For instance, in Athens, the kingship had been reduced to a

hereditary, lifelong chief magistracy (archon) by c. 1050 BC; by 753 BC this had become

a decennial, elected archonship; and finally by 683 BC an annually elected archonship.

Through each stage more power would have been transferred to the aristocracy as a

whole, and away from a single individual.

Inevitably, the domination of politics and concomitant aggregation of wealth by small

groups of families was apt to cause social unrest in many poleis. In many cities a tyrant (not

in the modern sense of repressive autocracies), would at some point seize control and

govern according to their own will; often a populist agenda would help sustain them in

power. In a system racked with class conflict, government by a 'strongman' was often the

best solution.

Athens fell under a tyranny in the second half of the 6th century. When this tyranny was ended, the Athenians founded the world's first

democracy as a radical solution to prevent the aristocracy regaining power. A citizens' assembly (the Ecclesia), for the discussion of

city policy, had existed since the reforms of Draco in 621 BC; all citizens were permitted to attend after the reforms of Solon (early

6th century), but the poorest citizens could not address the assembly or run for office. With the establishment of the democracy, the

assembly became the de jure mechanism of government; all citizens had equal privileges in the assembly. However, non-citizens, such

as metics (foreigners living in Athens) or slaves, had no political rights at all.

9/11/2014 Ancient Greece - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ancient_Greece 9/15

Gravestone of a woman with her

slave child-attendant, c. 100 BC

After the rise of the democracy in Athens, other city-states founded democracies. However, many retained more traditional forms of

government. As so often in other matters, Sparta was a notable exception to the rest of Greece, ruled through the whole period by

not one, but two hereditary monarchs. This was a form of diarchy. The Kings of Sparta belonged to the Agiads and the Eurypontids,

descendants respectively of Eurysthenes and Procles. Both dynasty founders were believed to be twin sons of Aristodemus, a

Heraclid ruler. However, the powers of these kings was trammeled by both a council of elders (the Gerousia) and magistrates

specifically appointed to watch over the kings (the Ephors).

Social structure

Only free, land owning, native-born men could be citizens entitled to the full protection of the law in a city-state (later Pericles

introduced exceptions to the native-born restriction). In most city-states, unlike the situation in Rome, social prominence did not allow

special rights. Sometimes families controlled public religious functions, but this ordinarily did not give any extra power in the

government. In Athens, the population was divided into four social classes based on wealth. People could change classes if they

made more money. In Sparta, all male citizens were given the title of equal if they finished their education. However, Spartan kings,

who served as the city-state's dual military and religious leaders, came from two families.

Slavery

Slaves had no power or status. They had the right to have a family and own property,

subject to their master's goodwill and permission, but they had no political rights. By 600

BC chattel slavery had spread in Greece. By the 5th century BC slaves made up one-third

of the total population in some city-states. Between forty and eighty per cent of the

population of Classical Athens were slaves.

[25]

Slaves outside of Sparta almost never

revolted because they were made up of too many nationalities and were too scattered to

organize.

Most families owned slaves as household servants and labourers, and even poor families

might have owned a few slaves. Owners were not allowed to beat or kill their slaves.

Owners often promised to free slaves in the future to encourage slaves to work hard.

Unlike in Rome, freedmen did not become citizens. Instead, they were mixed into the

population of metics, which included people from foreign countries or other city-states

who were officially allowed to live in the state.

City-states legally owned slaves. These public slaves had a larger measure of independence than slaves owned by families, living on

their own and performing specialized tasks. In Athens, public slaves were trained to look out for counterfeit coinage, while temple

slaves acted as servants of the temple's deity and Scythian slaves were employed in Athens as a police force corralling citizens to

political functions.

Sparta had a special type of slaves called helots. Helots were Messenians enslaved during the Messenian Wars by the state and

assigned to families where they were forced to stay. Helots raised food and did household chores so that women could concentrate

on raising strong children while men could devote their time to training as hoplites. Their masters treated them harshly (every Spartiate

male had to kill a helot as a right of passage), and helots often resorted to slave rebellions.

Education

For most of Greek history, education was private, except in Sparta. During the Hellenistic period, some city-states established public

schools. Only wealthy families could afford a teacher. Boys learned how to read, write and quote literature. They also learned to sing

and play one musical instrument and were trained as athletes for military service. They studied not for a job but to become an

effective citizen. Girls also learned to read, write and do simple arithmetic so they could manage the household. They almost never

received education after childhood.

Boys went to school at the age of seven, or went to the barracks, if they lived in Sparta. The three types of teachings were:

grammatistes for arithmetic, kitharistes for music and dancing, and Paedotribae for sports.

9/11/2014 Ancient Greece - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ancient_Greece 10/15

Mosaic from Pompeii depicting

Plato's academy

Greek hoplite and Persian warrior

depicted fighting, on an ancient kylix,

5th century BC

Boys from wealthy families attending the private school lessons were taken care of by a paidagogos, a household slave selected for

this task who accompanied the boy during the day. Classes were held in teachers' private houses and included reading, writing,

mathematics, singing, and playing the lyre and flute. When the boy became 12 years old the schooling started to include sports such

as wrestling, running, and throwing discus and javelin. In Athens some older youths attended academy for the finer disciplines such as

culture, sciences, music, and the arts. The schooling ended at age 18, followed by military training in the army usually for one or two

years.

[26]

A small number of boys continued their education after childhood, as in the Spartan agoge. A crucial part of a wealthy teenager's

education was a mentorship with an elder, which in a few places and times may have included pederastic love. The teenager learned

by watching his mentor talking about politics in the agora, helping him perform his public duties, exercising with him in the gymnasium

and attending symposia with him. The richest students continued their education by studying

with famous teachers. Some of Athens' greatest such schools included the Lyceum (the so-

called Peripatetic school founded by Aristotle of Stageira) and the Platonic Academy

(founded by Plato of Athens). The education system of the wealthy ancient Greeks is also

called Paideia.

Economy

At its economic height, in the 5th and 4th centuries BC, ancient Greece was the most

advanced economy in the world. According to some economic historians, it was one of the

most advanced preindustrial economies. This is demonstrated by the average daily wage of

the Greek worker which was, in terms of wheat, about 12 kg. This was more than 3 times

the average daily wage of an Egyptian worker during the Roman period, about 3.75 kg.

[27]

Warfare

At least in the Archaic Period, the fragmentary nature of ancient Greece, with many

competing city-states, increased the frequency of conflict but conversely limited the scale of

warfare. Unable to maintain professional armies, the city-states relied on their own citizens

to fight. This inevitably reduced the potential duration of campaigns, as citizens would need

to return to their own professions (especially in the case of, for example, farmers).

Campaigns would therefore often be restricted to summer. When battles occurred, they

were usually set piece and intended to be decisive. Casualties were slight compared to later

battles, rarely amounting to more than 5% of the losing side, but the slain often included the

most prominent citizens and generals who led from the front.

The scale and scope of warfare in ancient Greece changed dramatically as a result of the

Greco-Persian Wars. To fight the enormous armies of the Achaemenid Empire was

effectively beyond the capabilities of a single city-state. The eventual triumph of the Greeks

was achieved by alliances of city-states (the exact composition changing over time),

allowing the pooling of resources and division of labour. Although alliances between city-

states occurred before this time, nothing on this scale had been seen before. The rise of

Athens and Sparta as pre-eminent powers during this conflict led directly to the

Peloponnesian War, which saw further development of the nature of warfare, strategy and tactics. Fought between leagues of cities

dominated by Athens and Sparta, the increased manpower and financial resources increased the scale, and allowed the diversification

of warfare. Set-piece battles during the Peloponnesian war proved indecisive and instead there was increased reliance on attritionary

strategies, naval battle and blockades and sieges. These changes greatly increased the number of casualties and the disruption of

Greek society. Athens owned one of the largest war fleets in ancient Greece. It had over 200 triremes each powered by 170

oarsmen who were seated in 3 rows on each side of the ship. The city could afford such a large fleet-it had over 34,000 oars men-

because it owned a lot of silver mines that were worked by slaves.

Culture

Philosophy

9/11/2014 Ancient Greece - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ancient_Greece 11/15

The stadium of ancient Olympia,

home of the Ancient Olympic Games

The theatre of Epidauros, 4th century

BC

Ancient Greek philosophy focused on the role of reason and inquiry. In many ways, it had an important influence on modern

philosophy, as well as modern science. Clear unbroken lines of influence lead from ancient

Greek and Hellenistic philosophers, to medieval Muslim philosophers and Islamic scientists,

to the European Renaissance and Enlightenment, to the secular sciences of the modern day.

Neither reason nor inquiry began with the Greeks. Defining the difference between the

Greek quest for knowledge and the quests of the elder civilizations, such as the ancient

Egyptians and Babylonians, has long been a topic of study by theorists of civilization.

Some well-known philosophers of ancient Greece were Plato, Socrates, and many others.

They have aided in information about ancient Greek society through writings such as The

Republic, by Plato.

Literature and theatre

Ancient Greek society placed considerable emphasis upon literature. Many authors

consider the western literary tradition to have begun with the epic poems The Iliad and

The Odyssey, which remain giants in the literary canon for their skillful and vivid depictions

of war and peace, honor and disgrace, love and hatred. Notable among later Greek poets

was Sappho, who defined, in many ways, lyric poetry as a genre.

A playwright named Aeschylus changed Western literature forever when he introduced the

ideas of dialogue and interacting characters to playwriting. In doing so, he essentially

invented "drama": his Oresteia trilogy of plays is seen as his crowning achievement. Other

refiners of playwriting were Sophocles and Euripides. Sophocles is credited with skillfully

developing irony as a literary technique, most famously in his play Oedipus the King.

Euripedes, conversely, used plays to challenge societal norms and moresa hallmark of

much of Western literature for the next 2,300 years and beyondand his works such as

Medea, The Bacchae and The Trojan Women are still notable for their ability to challenge our perceptions of propriety, gender, and

war. Aristophanes, a comic playwright, defines and shapes the idea of comedy almost as Aeschylus had shaped tragedy as an art

formAristophanes' most famous plays include the Lysistrata and The Frogs.

Philosophy entered literature in the dialogues of Plato, who converted the give and take of Socratic questioning into written form.

Aristotle, Plato's student, wrote dozens of works on many scientific disciplines, but his greatest contribution to literature was likely his

Poetics, which lays out his understanding of drama, and thereby establishes the first criteria for literary criticism.

Music and dance

Music was present almost universally in Greek society, from marriages and funerals to religious ceremonies, theatre, folk music and

the ballad-like reciting of epic poetry. There are significant fragments of actual Greek musical notation as well as many literary

references to ancient Greek music. Greek art depicts musical instruments and dance. The word music derives from the name of the

Muses, the daughters of Zeus who were patron goddesses of the arts.

Science and technology

Ancient Greek mathematics contributed many important developments to the field of mathematics, including the basic rules of

geometry, the idea of formal mathematical proof, and discoveries in number theory, mathematical analysis, applied mathematics, and

approached close to establishing integral calculus. The discoveries of several Greek mathematicians, including Pythagoras, Euclid, and

Archimedes, are still used in mathematical teaching today.

The Greeks developed astronomy, which they treated as a branch of mathematics, to a highly sophisticated level. The first

geometrical, three-dimensional models to explain the apparent motion of the planets were developed in the 4th century BC by

Eudoxus of Cnidus and Callippus of Cyzicus. Their younger contemporary Heraclides Ponticus proposed that the Earth rotates

around its axis. In the 3rd century BC Aristarchus of Samos was the first to suggest a heliocentric system. Archimedes in his treatise

The Sand Reckoner revives Aristarchus' hypothesis that "the fixed stars and the Sun remain unmoved, while the Earth revolves

9/11/2014 Ancient Greece - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ancient_Greece 12/15

The Antikythera mechanism was an

analog computer from 150100 BC

designed to calculate the positions of

astronomical objects.

The Temple of Hera at Selinunte,

Sicily

Mount Olympus, home of the Twelve

Olympians

about the Sun on the circumference of a circle". Otherwise, only fragmentary descriptions of Aristarchus' idea survive.

[28]

Eratosthenes, using the angles of shadows created at widely separated regions, estimated the circumference of the Earth with great

accuracy.

[29]

In the 2nd century BC Hipparchus of Nicea made a number of contributions, including the first measurement of

precession and the compilation of the first star catalog in which he proposed the modern system of apparent magnitudes.

The Antikythera mechanism, a device for calculating the movements of planets, dates from about 80 BC, and was the first ancestor of

the astronomical computer. It was discovered in an ancient shipwreck off the Greek island of Antikythera, between Kythera and

Crete. The device became famous for its use of a differential gear, previously believed to have been invented in the 16th century, and

the miniaturization and complexity of its parts, comparable to a clock made in the 18th century. The original mechanism is displayed in

the Bronze collection of the National Archaeological Museum of Athens, accompanied by a replica.

The ancient Greeks also made important discoveries in the medical field. Hippocrates was

a physician of the Classical period, and is considered one of the most outstanding figures in

the history of medicine. He is referred to as the "father of medicine"

[30][31][32]

in recognition

of his lasting contributions to the field as the founder of the Hippocratic school of medicine.

This intellectual school revolutionized medicine in ancient Greece, establishing it as a

discipline distinct from other fields that it had traditionally been associated with (notably

theurgy and philosophy), thus making medicine a profession.

[33][34]

Art and architecture

The art of ancient Greece has exercised an enormous influence on the culture of many

countries from ancient times until the present, particularly in the areas of sculpture and

architecture. In the West, the art of the Roman Empire was largely derived from Greek

models. In the East, Alexander the Great's conquests initiated several centuries of exchange

between Greek, Central Asian and Indian cultures, resulting in Greco-Buddhist art, with

ramifications as far as Japan. Following the Renaissance in Europe, the humanist aesthetic

and the high technical standards of Greek art inspired generations of European artists. Well

into the 19th century, the classical tradition derived from Greece dominated the art of the

western world.

Religion and mythology

Greek mythology consists of stories belonging to the ancient Greeks concerning their gods

and heroes, the nature of the world and the origins and significance of their religious

practices. The main Greek gods were the twelve Olympians, Zeus, his wife Hera,

Poseidon, Ares, Hermes, Hephaestus, Aphrodite, Athena, Apollo, Artemis, Demeter, and

Dionysus. Other important deities included Hebe, Hades, Helios, Hestia, Persephone and

Heracles. Zeus's parents were Cronus and Rhea who also were the parents of Poseidon,

Hades, Hera, Hestia, and Demeter.

Legacy

The civilization of ancient Greece has been immensely influential on language, politics,

educational systems, philosophy, science, and the arts. It became the Leitkultur of the

Roman Empire to the point of marginalizing native Italic traditions. As Horace put it,

Graecia capta ferum victorem cepit et artes / intulit agresti Latio (Epistulae

2.1.156f.)

"Captive Greece took captive her fierce conqueror and instilled her arts in rustic Latium."

9/11/2014 Ancient Greece - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ancient_Greece 13/15

Via the Roman Empire, Greek culture came to be foundational to Western culture in general. The Byzantine Empire inherited

Classical Greek culture directly, without Latin intermediation, and the preservation of classical Greek learning in medieval Byzantine

tradition further exerted strong influence on the Slavs and later on the Islamic Golden Age and the Western European Renaissance. A

modern revival of Classical Greek learning took place in the Neoclassicism movement in 18th- and 19th-century Europe and the

Americas.

See also

Outline of ancient Greece

Regions of ancient Greece

Outline of ancient Rome

Outline of ancient Egypt

Outline of classical studies

Regions in Greco-Roman antiquity

Classical demography

History of science in classical antiquity

Citizenship in ancient Greece (article section)

Macedonia (ancient kingdom)

Toynbee's law of challenge and response.

References

Notes

1. ^ Carol G. Thomas (1988). Paths from ancient Greece (http://books.google.com/books?id=NAwVAAAAIAAJ&pg=PA27). BRILL.

pp. 2750. ISBN 978-90-04-08846-7. Retrieved 12 June 2011.

2. ^ Bruce Thornton, Greek Ways: How the Greeks Created Western Civilization, Encounter Books, 2002

3. ^ Richard Tarnas, The Passion of the Western Mind (http://books.google.com/books?

id=0n2C299jeOMC&lpg=PA25&pg=PP1#v=onepage&f=false) (New York: Ballantine Books, 1991).

4. ^ Colin Hynson, Ancient Greece (http://books.google.com/books?id=hmweq2TyxvsC&lpg=PT5&pg=PT5#v=onepage&f=false)

(Milwaukee: World Almanac Library, 2006), 4.

5. ^ Carol G. Thomas, Paths from Ancient Greece (http://books.google.com/books?

id=NAwVAAAAIAAJ&lpg=PA1&pg=PA1#v=onepage&f=false) (Leiden, Netherlands: E. J. Brill, 1988).

6. ^ Short, John R (1987), An Introduction to Urban Geography (http://books.google.com/books?

id=uGE9AAAAIAAJ&pg=PA10&dq=greek+dark+ages+776+BC&hl=en&sa=X&ei=nTfmT_uSIOek0QXhtOzoCA&sqi=2&ved=0CFI

Q6AEwBg#v=onepage&q=greek%20dark%20ages%20776%20BC&f=false), Routledge, p. 10.

7. ^ Pomeroy, Sarah B. (1999). Ancient Greece: a political, social, and cultural history (http://books.google.com/?id=INUT5sZku1UC).

Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-509742-9.

8. ^ Hadas, Moses (1950). A History of Greek Literature (http://books.google.com/books?

id=dOht3609JOMC&pg=PA273&dq=%22end+of+antiquity%22+%2B+%22529%22#v=onepage&q=%22end%20of%20antiquity%22

%20%2B%20%22529%22&f=false). Columbia University Press. p. 327. ISBN 0-231-01767-7.

9. ^ Grant, Michael (1995). Greek and Roman historians: information and misinformation (http://books.google.com/?

id=IUNxvi0kbd8C&dq=). Routledge, 1995. p. 74. ISBN 978-0-415-11770-8.

10. ^ Hall Jonathan M. (2007). A History of the Archaic Greek World, ca. 1200-479 BCE (http://books.google.com/?id=WGNH-

oxXiAUC&dq=). Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-631-22667-3.

11. ^ Sealey, Raphael (1976). A history of the Greek city states, ca. 700338 B.C. (http://books.google.com/?id=kAvbhZrv4gUC&dq=).

University of California Press. pp. 1011. ISBN 978-0-631-22667-3.

12. ^ Slavoj iek (18 April 2011). Living in the End Times (http://books.google.com/books?id=MIz6BPT23Q4C&pg=PA218). Verso.

9/11/2014 Ancient Greece - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ancient_Greece 14/15

Bibliography

Charles Freeman (1996). Egypt, Greece and Rome. Oxford University Press.

Paul MacKendrick (1962). The Greek Stones Speak: The Story of Archaeology in Greek Lands. St. Martin's Press.

Thomas Wardle (1835). The history of ancient Greece, its colonies and conquests from the earliest accounts till division of the

Macedonian Empire in the East (http://books.google.com/books?id=AktXAAAAYAAJ).

Further reading

12. ^ Slavoj iek (18 April 2011). Living in the End Times (http://books.google.com/books?id=MIz6BPT23Q4C&pg=PA218). Verso.

p. 218. ISBN 978-1-84467-702-3. Retrieved 12 June 2011.

13. ^ "Online Etymology Dictionary" (http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?term=tyrant). Etymonline.com. Retrieved 2009-01-06.

14. ^ "tyrantDefinitions from Dictionary.com" (http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/tyrant). Dictionary.reference.com. Archived

(https://web.archive.org/web/20090125013700/http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/Tyrant) from the original on 25 January 2009.

Retrieved 2009-01-06.

15. ^ Holland T. Persian Fire p69-70. ISBN 978-0-349-11717-1

16. ^ Holland T. Persian Fire p131-138. ISBN 978-0-349-11717-1

17. ^ Typhoid Fever Behind Fall of Athens (http://www.livescience.com/history/060123_athens_fall.html). LiveScience. January 23,

2006.

18. ^ Sources for the map: "Historical Atlas of Peninsular India" Oxford University Press (dark blue, continuous line), A.K. Narain "The

coins of the Indo-Greek kings" (dark blue, dotted line, see File:Indo-GreekWestermansNarain.jpg for reference), Westermans "Atlas

zur Weltgeschichte".

19. ^ Alexander's Gulf outpost uncovered (http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/europe/6930285.stm). BBC News. August 7, 2007.

20. ^ "Macedonia" (http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/354266/Macedonia). Encyclopdia Britannica. Encyclopdia Britannica

Online. 2008. Archived

(https://web.archive.org/web/20081208092317/http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/354266/Macedonia) from the original on

8 December 2008. Retrieved 2008-11-03.

21. ^ The Cambridge Ancient History: The fourth century B.C. edited by D.M. Lewis et al. I E S Edwards, Cambridge University Press,

D. M. Lewis, John Boardman, Cyril John Gadd, Nicholas Geoffrey Lemprire Hammond, 2000, ISBN 0-521-23348-8, pp. 723-724.

(http://books.google.com/books?id=vx251bK988gC&pg=RA6-PA750&dq=ancient+macedon&lr=&hl=bg#PRA6-PA719-IA4,M1)

22. ^ Population of the Greek city-states (http://www.umsystem.edu/upress/fall2006/hansen.htm)

23. ^ Holland, T. Persian Fire, Abacus, ISBN 978-0-349-11717-1

24. ^ Holland T. Persian Fire, p94 ISBN 978-0-349-11717-1

25. ^ Slavery in Ancient Greece (http://student.britannica.com/comptons/article-201729/ANCIENT-GREECE). Britannica Student

Encyclopdia.

26. ^ Angus Konstam: "Historical Atlas of Ancient Greece", pp. 94-95. Thalamus publishing, UK, 2003, ISBN 1-904668-16-X

27. ^ W. Schieder, "Real slave prices and the relative cost of slave labor in the Greco-Roman world", Ancient Society, vol. 35, 2005.

28. ^ Pedersen, Early Physics and Astronomy, pp. 55-6

29. ^ Pedersen, Early Physics and Astronomy, pp. 45-7

30. ^ Grammaticos, P. C.; Diamantis, A. (2008). "Useful known and unknown views of the father of modern medicine, Hippocrates and

his teacher Democritus". Hellenic journal of nuclear medicine 11 (1): 24. PMID 18392218

(https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18392218).

31. ^ Hippocrates (http://encarta.msn.com/encyclopedia_761576397/Hippocrates.html), Microsoft Encarta Online Encyclopedia 2006.

Microsoft Corporation. Archived (http://www.webcitation.org/5kwKKh4qP) 2009-10-31.

32. ^ Strong, W.F.; Cook, John A. (July 2007). "Reviving the Dead Greek Guys" (http://www.manipal.edu/gmj/issues/jul07/strong.php).

Global Media Journal, Indian Edition. ISSN: 1550-7521.

33. ^ Garrison, Fielding H. (1966). History of Medicine. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders Company. pp. 9293.

34. ^ Nuland, Sherwin B. (1988). Doctors. Knopf. p. 5. ISBN 0-394-55130-3.

9/11/2014 Ancient Greece - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ancient_Greece 15/15

Wikimedia Commons has

media related to Ancient

Greece.

Goodrich, S. G. (1849). A pictorial history of Greece (http://books.google.com/books?id=cxPPAAAAMAAJ): Ancient and

modern. New York: Huntington & Savage

External links

The Canadian Museum of CivilizationGreece Secrets of the Past

(http://www.civilization.ca/cmc/exhibitions/civil/greece/gr0000e.shtml)

Ancient Greece (http://www.ancientgreece.co.uk) website from the British Museum

Economic history of ancient Greece (http://eh.net/encyclopedia/article/engen.greece)

The Greek currency history (http://www.fleur-de-coin.com/currency/drachma-history)

Limenoscope (http://www.limenoscope.ntua.gr/index.cgi?lan=en), an ancient Greek ports database

The Ancient Theatre Archive (http://www.whitman.edu/theatre/theatretour/home.htm), Greek and Roman theatre architecture

Illustrated Greek History (http://people.hsc.edu/drjclassics/lectures/history/history.shtm), Dr. Janice Siegel, Department of

Classics, Hampden-Sydney College, Virginia

Retrieved from "http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Ancient_Greece&oldid=623970644"

Categories: Ancient Greece

This page was last modified on 3 September 2014 at 06:58.

Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License; additional terms may apply. By using this site,

you agree to the Terms of Use and Privacy Policy. Wikipedia is a registered trademark of the Wikimedia Foundation, Inc., a

non-profit organization.

Você também pode gostar

- Manipulation of Human Behavior (The) (Albert D. Biderman, Herbert Zimmer 1961)Documento349 páginasManipulation of Human Behavior (The) (Albert D. Biderman, Herbert Zimmer 1961)DELHAYE95% (19)

- About Ancient GreeceDocumento25 páginasAbout Ancient GreeceGost hunterAinda não há avaliações

- Ancient Greece: From Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaDocumento16 páginasAncient Greece: From Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopediaanku5108100% (1)

- Chronology Information Source:: Map of Map of Etruscan Etruscan Cities CitiesDocumento14 páginasChronology Information Source:: Map of Map of Etruscan Etruscan Cities CitiesAngel-Alex HaisanAinda não há avaliações

- Ancient Greek CivilizationDocumento50 páginasAncient Greek CivilizationSukesh Subaharan50% (2)

- Linguistic Evidence On The Macedonian Question (By Ioannis Kallianiotis)Documento22 páginasLinguistic Evidence On The Macedonian Question (By Ioannis Kallianiotis)Macedonia - The Authentic TruthAinda não há avaliações

- Greek and Roman MythologyDocumento31 páginasGreek and Roman MythologyCai04Ainda não há avaliações

- The Masked AssassinationDocumento12 páginasThe Masked AssassinationJaewon LeeAinda não há avaliações

- A Biographical Dictionary of Ancient EgyptDocumento206 páginasA Biographical Dictionary of Ancient Egyptساجدة لله50% (2)

- SekigaharaDocumento416 páginasSekigaharaxazgardx100% (2)

- Greek LiteratureDocumento31 páginasGreek LiteratureMiggy BaluyutAinda não há avaliações

- Western Civilization: Ch. 3Documento7 páginasWestern Civilization: Ch. 3LorenSolsberry67% (3)

- Minoan CivilizationDocumento21 páginasMinoan CivilizationVibhuti Dabrāl100% (1)

- Secret WorldDocumento2 páginasSecret WorldRaushan KumarAinda não há avaliações

- Greek Mythology: A Guide to Ancient Greece and Greek Mythology including Titans, Hercules, Greek Gods, Zeus, and More!No EverandGreek Mythology: A Guide to Ancient Greece and Greek Mythology including Titans, Hercules, Greek Gods, Zeus, and More!Ainda não há avaliações

- Yank 1943feb10 PDFDocumento24 páginasYank 1943feb10 PDFjohn obrien100% (1)

- Magpul 2012 Catalog Stocks, Sling System, GripsDocumento19 páginasMagpul 2012 Catalog Stocks, Sling System, GripsYaroslav Sergeev100% (1)

- Ancient GreeceDocumento39 páginasAncient GreeceSantiago Zurita100% (2)

- Cult of UlricDocumento7 páginasCult of Ulricdangerbunny23100% (1)

- C Programming LanguageDocumento20 páginasC Programming Languageaquel1983Ainda não há avaliações

- Snyder Security Dilemma in AllianceDocumento2 páginasSnyder Security Dilemma in AlliancemaviogluAinda não há avaliações

- Technical Skills ListDocumento17 páginasTechnical Skills Listaquel1983Ainda não há avaliações

- Ancient Greek CivilisationDocumento17 páginasAncient Greek CivilisationSanditi Gargya100% (1)

- Italian Early and High Renaissance ArtDocumento31 páginasItalian Early and High Renaissance ArtjillysillyAinda não há avaliações

- 1 Adventure Freeport The Freeport Trilogy Five Year Anniversary Edition 1Documento144 páginas1 Adventure Freeport The Freeport Trilogy Five Year Anniversary Edition 1Timothy Hamby50% (4)

- Ancient Greeks at War: Warfare in the Classical World from Agamemnon to AlexanderNo EverandAncient Greeks at War: Warfare in the Classical World from Agamemnon to AlexanderAinda não há avaliações

- Lecture 9 The Greek Civilization The Forming of Greek CivilizationDocumento53 páginasLecture 9 The Greek Civilization The Forming of Greek CivilizationIlmiat FarhanaAinda não há avaliações

- A Overview of Greek HistoryDocumento19 páginasA Overview of Greek Historynetname1100% (1)

- The Generation of Postmemeory - Marianne HirschDocumento26 páginasThe Generation of Postmemeory - Marianne Hirschmtustunn100% (2)

- Joseph Nye On Global Power ShiftsDocumento4 páginasJoseph Nye On Global Power ShiftsRaissa BonfimAinda não há avaliações

- Studies in Constantinian Chronology / by Patrick BruunDocumento140 páginasStudies in Constantinian Chronology / by Patrick BruunDigital Library Numis (DLN)100% (1)

- A History of the Classical World: The Story of Ancient Greece and RomeNo EverandA History of the Classical World: The Story of Ancient Greece and RomeAinda não há avaliações

- Chap 2 Prehistoric AgeDocumento19 páginasChap 2 Prehistoric AgeDan Lhery Susano GregoriousAinda não há avaliações

- General Bibliography About Alexander The GreatDocumento3 páginasGeneral Bibliography About Alexander The GreatPezanosAinda não há avaliações

- Topic 4.1. Greek Civilization-The City StateDocumento5 páginasTopic 4.1. Greek Civilization-The City StateNathaniaAinda não há avaliações

- Art App PPT Renaissance PaintingsDocumento15 páginasArt App PPT Renaissance PaintingsKarmina Santos100% (1)

- Semestre - G. Carlos P. Tatel, JRDocumento5 páginasSemestre - G. Carlos P. Tatel, JRStl JoseAinda não há avaliações

- AeschylusDocumento19 páginasAeschylusfrancesAinda não há avaliações

- Excerpts-Summary - A Handbook of Greek MythologyDocumento3 páginasExcerpts-Summary - A Handbook of Greek MythologyHalid LepanAinda não há avaliações

- HMNT 210 Chapter 19 Study Guide: Devotio ModernaDocumento3 páginasHMNT 210 Chapter 19 Study Guide: Devotio Modernagypsy90100% (1)

- History SyllabusDocumento5 páginasHistory SyllabusSojin Soman100% (1)

- Ancient Greece - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaDocumento17 páginasAncient Greece - Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopediasandra072353Ainda não há avaliações

- Ancient Greece (GreekDocumento22 páginasAncient Greece (GreekSashimiTourloublancAinda não há avaliações

- Ancient GreeceDocumento23 páginasAncient GreeceASDAinda não há avaliações

- Ancient GreeceDocumento21 páginasAncient GreeceTamer BhuiyannAinda não há avaliações

- Ancient Greece Was ADocumento17 páginasAncient Greece Was AFernán GaillardouAinda não há avaliações

- Ancient GreeceDocumento12 páginasAncient GreeceAngela PageAinda não há avaliações

- Ancient Greece (: Hellás) Was ADocumento2 páginasAncient Greece (: Hellás) Was AJack SwaggerAinda não há avaliações

- Ancient Greece (GreekDocumento22 páginasAncient Greece (GreekAndreGuilhermeAinda não há avaliações

- A Very Brief Outline of Greek History (To A.D. 1453) : The Prehistoric PeriodsDocumento4 páginasA Very Brief Outline of Greek History (To A.D. 1453) : The Prehistoric PeriodsPrincess kc DocotAinda não há avaliações

- Ancient Greece: Navigation SearchDocumento22 páginasAncient Greece: Navigation SearchashwinisathyaAinda não há avaliações

- Classical AntiquityDocumento11 páginasClassical Antiquityahmedzommit394Ainda não há avaliações

- Ancient Greece - WikipediaDocumento55 páginasAncient Greece - Wikipediaalapideeric75Ainda não há avaliações

- Classical Antiquity: (Note 1)Documento11 páginasClassical Antiquity: (Note 1)SashimiTourloublancAinda não há avaliações

- Classical Antiquity 54Documento12 páginasClassical Antiquity 54Ryan HoganAinda não há avaliações

- Classical Antiquity - WikipediaDocumento7 páginasClassical Antiquity - Wikipediavedprakashabhay500Ainda não há avaliações

- Ancient GreeceDocumento12 páginasAncient GreeceSWAPNILAinda não há avaliações

- Iron Age CivilizationDocumento48 páginasIron Age CivilizationThulla SupriyaAinda não há avaliações

- Ancient GreeceDocumento25 páginasAncient GreeceAdam Bin Mat RofiAinda não há avaliações

- Chronology: Ancient Greece (Documento2 páginasChronology: Ancient Greece (Azreen Anis azmiAinda não há avaliações

- Enmanuel Benavides MagazineDocumento14 páginasEnmanuel Benavides MagazineEnmanuel BenavidesAinda não há avaliações

- Ancient Greece: The World History (His205)Documento16 páginasAncient Greece: The World History (His205)salman kabirAinda não há avaliações

- Archaic PeriodDocumento18 páginasArchaic PeriodMiruna Maria CiuraAinda não há avaliações

- From The Earliest Settlements To The 3rd Century B.C.: Main ArticleDocumento45 páginasFrom The Earliest Settlements To The 3rd Century B.C.: Main Articleemmanuelosorio0207Ainda não há avaliações

- Hellenistic PeriodDocumento5 páginasHellenistic PeriodTerryAinda não há avaliações

- Hellenistic PeriodDocumento34 páginasHellenistic PerioddonAinda não há avaliações

- Crime and Punishment in Ancient Greece and Rome: The University of Western OntarioDocumento37 páginasCrime and Punishment in Ancient Greece and Rome: The University of Western OntarioJack SummerhayesAinda não há avaliações

- Classical PeriodDocumento7 páginasClassical PeriodDaniela OrtalAinda não há avaliações

- Dgtal PathwayDocumento7 páginasDgtal PathwayKelvin WinataAinda não há avaliações

- HellenisticDocumento8 páginasHellenisticToram JumskieAinda não há avaliações

- GreeceDocumento21 páginasGreeceapi-276881923Ainda não há avaliações

- Historico Legal Foundation of Education 20231015 121309 0000Documento70 páginasHistorico Legal Foundation of Education 20231015 121309 0000castromarkallien11Ainda não há avaliações

- World CivilizationsDocumento3 páginasWorld CivilizationsJaya ShankarAinda não há avaliações

- 第二章 希腊时期 识记要点Documento2 páginas第二章 希腊时期 识记要点svb128128128Ainda não há avaliações

- Mobile PhoneDocumento14 páginasMobile Phoneaquel1983Ainda não há avaliações

- Oregon Caves National Monument and PreserveDocumento12 páginasOregon Caves National Monument and Preserveaquel1983Ainda não há avaliações

- Schneider Electric - Uniflair-Direct-Expansion-InRow-Cooling - ACRD301Documento3 páginasSchneider Electric - Uniflair-Direct-Expansion-InRow-Cooling - ACRD301aquel1983Ainda não há avaliações

- 2017 Bahawalpur ExplosionDocumento3 páginas2017 Bahawalpur Explosionaquel1983Ainda não há avaliações

- Employee BenefitDocumento5 páginasEmployee Benefitaquel1983Ainda não há avaliações

- Human Resource ManagementDocumento10 páginasHuman Resource Managementaquel19830% (1)

- Salary PackagingDocumento2 páginasSalary Packagingaquel1983Ainda não há avaliações

- Donald J DrumpfDocumento5 páginasDonald J Drumpfaquel1983Ainda não há avaliações

- Competencias Digitales para El sXXI: Fomento de La Competitividad, El Crecimiento y El EmpleoDocumento10 páginasCompetencias Digitales para El sXXI: Fomento de La Competitividad, El Crecimiento y El EmpleoJoaquín Vicente Ramos RodríguezAinda não há avaliações

- Cassini HuygensDocumento28 páginasCassini Huygensaquel1983Ainda não há avaliações

- SaturnDocumento22 páginasSaturnaquel1983Ainda não há avaliações

- TitanDocumento28 páginasTitanaquel1983Ainda não há avaliações

- Knowledge ManagementDocumento9 páginasKnowledge Managementaquel1983Ainda não há avaliações

- JupiterDocumento28 páginasJupiteraquel1983Ainda não há avaliações

- UranusDocumento28 páginasUranusaquel1983Ainda não há avaliações

- Wikipedia For RobotsDocumento5 páginasWikipedia For Robotsaquel1983Ainda não há avaliações

- Tara Air Flight 193Documento3 páginasTara Air Flight 193aquel1983Ainda não há avaliações

- Youth On The Prow, and Pleasure at The HelmDocumento9 páginasYouth On The Prow, and Pleasure at The Helmaquel1983Ainda não há avaliações

- World War I MemorialsDocumento38 páginasWorld War I Memorialsaquel1983Ainda não há avaliações

- EITCI, The European IT Certification Institute - EITCIDocumento3 páginasEITCI, The European IT Certification Institute - EITCIaquel1983Ainda não há avaliações

- Digital Skills - PRINT 2Documento1 páginaDigital Skills - PRINT 2aquel1983Ainda não há avaliações

- Norwich War MemorialDocumento5 páginasNorwich War Memorialaquel1983Ainda não há avaliações

- From Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaDocumento12 páginasFrom Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopediaaquel1983Ainda não há avaliações

- 2015 Mina StampedeDocumento11 páginas2015 Mina Stampedeaquel1983Ainda não há avaliações

- Banksia MenziesiiDocumento11 páginasBanksia Menziesiiaquel1983Ainda não há avaliações

- William The ConquerorDocumento29 páginasWilliam The Conqueroraquel1983Ainda não há avaliações

- From Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaDocumento16 páginasFrom Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopediaaquel1983Ainda não há avaliações

- Bell Labs: For Buildings Named Bell Telephone Laboratories, See Bell Laboratories Building (Manhattan)Documento12 páginasBell Labs: For Buildings Named Bell Telephone Laboratories, See Bell Laboratories Building (Manhattan)aquel1983Ainda não há avaliações

- The Iliad: Heroes and VillainsDocumento9 páginasThe Iliad: Heroes and VillainsNatasha Marsalli100% (1)

- Zippy The Pinhead DatabaseDocumento19 páginasZippy The Pinhead DatabaseSamuel50% (2)

- Local Media5689674217973705000Documento42 páginasLocal Media5689674217973705000Wyndel RadaAinda não há avaliações

- Army Aviation Digest - Apr 1965Documento52 páginasArmy Aviation Digest - Apr 1965Aviation/Space History LibraryAinda não há avaliações

- Fia Past PapersDocumento8 páginasFia Past PapersMuazzam Yaqoob Muhammad YaqoobAinda não há avaliações

- AOB by Eye ManualDocumento13 páginasAOB by Eye Manualerik_xAinda não há avaliações

- Hoaxes Philippines HistoryDocumento14 páginasHoaxes Philippines HistoryDivine Via Daroy100% (1)

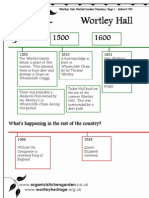

- Wortley Hall Walled Garden TimelineDocumento6 páginasWortley Hall Walled Garden TimelinejotownshendAinda não há avaliações

- Metamorphoses Reading PlanDocumento5 páginasMetamorphoses Reading PlanBrendanAinda não há avaliações

- Alencastro - South AtlanticDocumento26 páginasAlencastro - South AtlanticLeonardo MarquesAinda não há avaliações

- Dungeon Siege II ChantDocumento239 páginasDungeon Siege II ChantQuangHung TranAinda não há avaliações

- Twentieth Century British DramaDocumento20 páginasTwentieth Century British DramaElYasserAinda não há avaliações

- Winning The West: The U.S Army in The Indian Wars 1865-1890Documento8 páginasWinning The West: The U.S Army in The Indian Wars 1865-1890andreyAinda não há avaliações

- Singing of National Anthem in TamilDocumento4 páginasSinging of National Anthem in TamilThavam RatnaAinda não há avaliações

- Second Barons' War - WikipediaDocumento6 páginasSecond Barons' War - WikipediaJohn OrtizAinda não há avaliações

- Factors of French RevolutionDocumento8 páginasFactors of French RevolutionAkshatAinda não há avaliações

- Prova de Conhecimentos Específicos E Redação: Vestibular 2014 Acesso 2015Documento20 páginasProva de Conhecimentos Específicos E Redação: Vestibular 2014 Acesso 2015Ghueja HamedaAinda não há avaliações

- Military Synthesis in South Asia ArmiesDocumento67 páginasMilitary Synthesis in South Asia ArmiesStrategicus PublicationsAinda não há avaliações