Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Media Law Outline

Enviado por

Ben BeezyDireitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Media Law Outline

Enviado por

Ben BeezyDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Media Law

Shield Laws:

California Constitution: A publisher, editor, reporter, or other person connected with or

employed upon a newspaper, magazine, or other periodical publication ... shall not be

adjudged in contempt ... for refusing to disclose the source of any information procured

while so connected or employed for publication in a newspaper, magazine or other

periodical publication, or for refusing to disclose any unpublished information obtained

or prepared in gathering, receiving or processing of information for communication to the

public. vidence Code section !"#", subdivision $a%, is to substantially the same effect.

&'(rady:

a% Are plaintiffs performing legitimate journalism) *e decline the implicit

invitation to embroil ourselves in +uestions of what constitutes legitimate

journalis,m-. .he shield law is intended to protect the gathering and

dissemination of news, and that is what petitioners did here. *e can thin/

of no wor/able test or principle that would distinguish legitimate from

illegitimate news. Any attempt by courts to draw such a distinction

would imperil a fundamental purpose of the 0irst Amendment, which is to

identify the best, most important, and most valuable ideas not by any

sociological or economic formula, rule of law, or process of government,

but through the rough and tumble competition of the memetic mar/etplace.

&1(rady v. 2uperior Court, !34 Cal. App. 5th !563, !57#, 55 Cal. 8ptr. 3d

#6, 4# $Cal. Ct. App. 6""9%

b% Does the shield cover the defendants) Are poster websites protected) .he

:egislature was aware that the inclusion of this language could e;tend the

statute1s protections to something as occasional as a legislator1s newsletter.

<f the :egislature was prepared to sweep that broadly, it must have intended

that the statute protect publications li/e petitioners1, which differ from

traditional periodicals only in their tendency, which flows directly from the

advanced technology they employ, to continuously update their content.

&1(rady v. 2uperior Court, !34 Cal. App. 5th !563, !599, 55 Cal. 8ptr. 3d

#6, !"5="7 $Cal. Ct. App. 6""9%

Intrusions into Sources:

Three part test to pierce:

substantial evidence,:-,!- that the challenged statement was published and is both

factually untrue and defamatory> ,6- that reasonable efforts to discover the information

from alternative sources have been made and that no other reasonable source is available>

and ,3- that /nowledge of the identity of the informant is necessary to proper preparation

and presentation of the case. ?rice v. .ime, <nc., 5!9 0.3d !36#, !353 as modified on

denial of reh1g, 567 0.3d !646 $!!th Cir. 6""7%.

====<f confidential source perjures his or himself about their identity, the reporter does not

have to disclose.

Lawyer Counseling:

@uestions:

!

a) *as the prepublication review a sham) (Harte Hanks)

b) *ere the defendant's communication with counsel conducted with the e;press

purpose of promoting or continuing criminal or fraudulent activity)

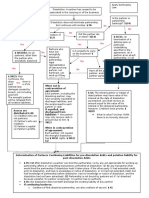

I. Defamation

<s damage an element) $element according to statute and CA 2C%

Aamages may be presumed if clear and convincing evidence of actual malice

CA says tendency to cause damage

Bnprivileged: another element or a defense)

.his is an affirmative defense

Affirmative defense=even if every element of cause of action is met we still win because

of defense

<s libel of the government possible)

Co, a government or government agency doesn't have agency to sue

<t's reputation will not be diminished

?olicy: we don't want to have the government or government agency to be

involved

Air Dimbawbe case: since majority of airline owned by country government then

libel laws don't apply

A% <s it defamation per se

$so basic to prove% $falsely impute criminal activity, impute an

offensive disease, would tend to injure a party1s trade, occupation or business, or impute

unchastity or homose;uality% or per !uod $a statement whose defamatory import can only

be ascertained by reference to facts not set forth in the publication. <f a defamatory

statement is not per se actionable, but is, per !uod, then plaintiff must plead special

damages in order to sustain the defamation action%)

E% <s it libel $includes the more permanent forms of defamatory matter> in California, it

consists of a writing, printing, picture, effigy, or other fi;ed representation to the eye.

$C.C. 57, infra, F734.% or slander $more transitory form, generally restricted to oral

statements and gestures. $2ee C.C. 59, infra, F77!%)

"lements:

1. A statement of fact

!

.o determine whether a statement is per se actionable, courts loo/ at whether the

character of the language used, in the conte;t of the entire publication as well as the

circumstances of its issuance, would naturally import one of the above mentioned charges

in the mind of an average person. ;trinsic facts may be considered in determining

whether a writing is libelous per se if the e;trinsic facts are presumably /nown to the

readers of the statement.

6

0ederal .est $4th Cir%: a% language used> b% conte;t $tenor of statement%> c%

susceptibility of being proven true or false

California .otality of Circumstances .est: California courts had employed a

totality of the circumstances test to differentiate between fact and opinion:

0irst, the language of the statement is e;amined. 0or words to be defamatory,

they must be understood in a defamatory sense .... Ce;t, the conte;t in which the

statement was made must be considered. ... .his conte;tual analysis demands that

the courts loo/ at the nature and full content of the communication and to the

/nowledge and understanding of the audience to whom the publication was

directed.Goyer v. Amador Halley I. Bnion Jigh 2ch. Aist., 667 Cal. App. 3d #6",

#65, 6#7 Cal. 8ptr. 545 $Cal. Ct. App. !44"%

a% &pinion is not a statement of fact unlessKven if the spea/er states

the facts upon which he bases his opinion, if those facts are either

incorrect or incomplete, or if his assessment of them is erroneous, the

statement may still imply a false assertion of fact. 2imply couching such

statements in terms of opinion does not dispel these implications> and the

statement $#ilkovich v$ %orain &ournal 'o$%

b% (upportable )nterpretation Test: .his supportable interpretation

standard provides that a critic1s interpretation must be rationall*

supportable by reference to the actual te;t he or she is evaluating, and thus

would not immunize situations analogous to that presented in #ilkovich,

in which a writer launches a personal attac/, rather than interpreting a

boo/. .his standard also establishes boundaries even for te;tual

interpretation. A critic1s statement must be a rational assessment or account

of something the reviewer can point to in the te+t, or omitted from the te+t,

being criti+ued. Goldea v. Cew Lor/ .imes Co., 66 0.3d 3!", 3!7 $A.C.

Cir. !445%

c% 8hetorical hyperbole=yes of a reasonable person

d% ?arody and 2atire=taste is not to be considered, *ould a reasonable

person believe that this is a statement of fact)

e% ?resentation of alternative events

f% @ueries= titles can be defamatory

2. That is u!lished

a% Jas the speech been communicated to a third person)

b% 2ingle publication rule= reissues of the same publication doesn't

lead to same publication> but new editions can $unclear e;actly

why%

c% 8epublication= very publisher in a chain can be held liable, if a

media source states something li/e :A .imes says M they can

still be held liable, not a defense to say < just heard it from

someone reputable

d% 8espondeat superior= employer can be held liable for employee

$AA8 v. 8olling 2tone= magazine can't be held liable for

independent author%

e% ?ublishers vs. distributors and vendors=a distributor can be liable

if they /now or should /now its defamatory

3

f% Compulsory self=defamation=comes up typically in the

employment conte;t, $e;ample: you have to repeat a defamatory

statement let's say if you are accused of stealing and didn't and

then you are applying for a new job%

,as it posted b* an )(- (internet service provider).Also websites

<mmunity

6

: lawsuits see/ing to hold a service provider liable for its

e;ercise of a publisher1s traditional editorial functions=such as

deciding whether to publish, withdraw, postpone or alter content=are

barred. Deran v. Am. &nline, <nc., !64 0.3d 36#, 33" $5th Cir. !44#%.

"+ception: immunity is lost when internet provider or user

materially contributes to defamatory nature of the

underlying communication

". That is #of and concerning$ the laintiff

Test: <s the statement certainly about the plaintiff)

According to Auvil: it re+uired a showing that the offending language

pertains directly to a particular individual or product whose

identity can be ascertained from the te;t $and conte;t% of the publication.

2tatements about a religious, ethnic, or political group could invite thousands of lawsuits

from disgruntled members of these groups claiming that the portrayal was inaccurate and

thus libelous. 2uch suits would be especially damaging to the media, and could result in

the public receiving less information about topics of general concern

*ho can't sue) i% government> ii% dead people> iii% people neither identified nor

named> $Elatty%

According to /indrim a fictional plaintiff may be able to sue

0roup of people: .he real test in weighing identification is whether some

ne;us e;ists between plaintiff and the allegedly defamatory language.

(ales. Also loo/ to how small or large the group is. Ceed

specificity of reference.

%. That is defamatory

"

6

2ection 63" $c%$!%= Co provider or user of an interactive computer service shall be treated as the publisher

or spea/er of any information provided by another information content provider.

3

Consider the following cast of characters:

Communist N Iohn Eirchers

=at a certain time it was defamatory

=maybe now more rhetorical hyperbole

=Gac:eod v. .ribune=

Iohn Eircher $*ashburn case%= that's not defamatory

*hat about homose;ual)

Bnethical attorneys

$Albertini case=yes%>$Iames=no%

Call girls $Gontandon=yes%, bitches, $Gartin% and s/an/s $2eelig%

2ons of bitches $not actually defamatory%

:ier=$Gil/ovich%

*hat about alterior motives)

;hibiting socipathic tendencies

Cot actually accusing people

*ea/ling or coward=

B0C fighter suggesting to settle claims defamation=

5

Test: Aoes the false statement of fact injure ,or tend to injure- the

plaintiff's reputation ,in a substantial and respectable segment of

the community-)

Defamation /* )mplication: Test

1

!. <s the alleged defamatory inference reasonably drawn by the

language and tenor of the publication)

i.e. in *hite: letters that said police officer initially failed

drug and test and then was given high position

might suggest bribery,

6. Aid the publisher do something to suggest that heOshe intended

or endorsed the alleged inference)

=in Chapin raising +uestions about something is not enough

for a cause of action, same with .homas

3. Aoes it matter whether the publisher actually intended the

inference)

a. Cot an aspect considered at least by the 5th circuit

b. 4th circuit says yes in .homas v. :A .imes $!"!3

Aodds%

a% Jeadlines can be defamatory

b% .rade :ibel= intentional disparagement of the +uality of property,

leading to pecuniary damage

&. That is false=<s it substantially true) $Gasson%

.o ensure that true speech on matters of public concern is not deterred,

we hold that the common=law presumption that defamatory speech is false

cannot stand when a plaintiff see/s damages against a media defendant for

speech of public concern. ?hiladelphia Cewspapers, <nc. v. Jepps, 5#7

B.2. #9#, ##9=##$!4P9%. Eecause such a chilling effect would be

antithetical to the 0irst Amendment1s protection of true speech on matters

of public concern, we believe that a private=figure plaintiff must bear the

burden of showing that the speech at issue is false before recovering

damages for defamation from a media defendant.

?hiladelphia Cewspapers, <nc. v. Jepps, 5#7 B.2. #9# $!4P9%.

a$ )s the substance, gist, and sting of the libel justified.

b$ ,ere !uotes altered. )f so2

*e conclude that a deliberate alteration of the words uttered by a

plaintiff does not e+uate with /nowledge of falsity for purposes of

2ocializing with &I 2impson=not defamatory

CA8C2 and snitches Qnever found to be defamatory. 6 reasons: !% <nforming police is a good thing, it is socially

constructive behavior in a good segment of society

5

<n California: 0irst, we loo/ at the statement in its broad conte;t, which includes the general tenor of the

entire wor/, the subject of the statements, the setting, and the format of the wor/ $li/e is it a review or not

where things are less factual%. Ce;t we turn to the specific conte;t and content of the statements, analyzing

the e;tent of figurative or hyperbolic language used and the reasonable e;pectations of the audience in that

particular situation $more hyperbole ma/es it less factual%. 0inally, we in+uire whether the statement itself

is sufficiently factual to be susceptible of being proved true or false. .homas v. :os Angeles .imes

Communications, ::C, !P4 0. 2upp. 6d !""7, !"!7.

7

3ew 4ork Times 'o$ v$ (ullivan, 3#9 B.2., at 6#4=6P", P5 2.Ct., at

#67=#69 and 0ert5 v$ 6obert ,elch, )nc$, supra, 5!P B.2., at 356,

45 2.Ct., at 3""P, unless the alteration results in a material change

in the meaning conveyed by the statement. .he use of +uotations

to attribute words not in fact spo/en bears in a most important

way on that in+uiry, but it is not dispositive in every case. Gasson

v. Cew Lor/er Gagazine, <nc., 7"! B.2. 549, 7!#, $!44!%

'. (or which the defendant is at fault

2teps in the fault elements:

!. *hat type of defamation plaintiff)

6. *hat is the appropriate level of fault)

3. Jas the plaintiff satisfied the burden of proof)

) ,hat t*pe of defamation plaintiff.

a% -ublic 7fficials: (overnment employees who have or appear to

have K substantial responsibility for or control over the conduct of

governmental affairs. 8osenblatt v. Eaer

a position in government ,who- has such apparent importance that

the public has an independent interest in the +ualifications and

performance of the person who holds it, beyond the general

public interest in the +ualifications and performance of all

government employees <d.

b% -ublic 8igures:

i% 0eneral -urpose -ublic 8igures: ?eople who have

general fame or notoriety in the community, and

pervasive involvement in the affairs of society (ertz

?eople who occupy such pervasive power and influence

that they are deemed public figures for all

purposes. 8osenblatt

ii% %imited -urpose: ?eople who have thrust themselves to

the forefront of a particular ,e;isting- controversy in order

to influence the resolution of the issues involved.

(ertz

iii% )nvoluntar*: ?eople who are drawn into pre=e;isting

controversies. (ertz

c% -rivate 8igures: .he rest of the world.

d% <s the speech a matter of public concern)

9) ,hat is the appropriate level of fault.

a% -ublic officials and general purpose public figures:

=Actual Galice by clear and convincing evidence $i.e.,

strong, positive and free from doubt%

b% %imited purpose and involuntar* public figures:

=Actual malice, by clear and convincing evidence, on the

statements pertaining to controversy

c% -rivate figures on matters of private concern:

9

=Co liability without fault Q i.e., no strict liability for

defamation

= .ypically, negligence by a preponderance of evidence

=Can recover punitive and presumed damages without

showing actual malice

d% Do private figures ever need to prove actual malice)

=Gatters of public concern

=?unitive or presumed damages $re statements that are

matter of public concern%

?olicy: .he first remedy of any defamation victim is self=help Q using available

opportunities to contradict the lie or correct the error and thereby to minimize its adverse

impact on reputation. ?ublic officials and public officials usually enjoy significantly

greater access to the channels of effective communication and hence have a more realistic

opportunity to counteract false statements than private individuals K ?rivate individuals

are therefore more vulnerable to injury, and the state interest in protecting them is

correspondingly greater. (ertz v. 8obert *elch, <nc.

==?ublic people have power and influence and invite attention and comment.

:) Has the plaintiff satisfied the burden of proof.

Actual #alice: Rnowledge of falsity of rec/less disregard of the

truth. Jigh degree of awareness of falsity $Harte Hanks%

or entertaining serious doubts about the truth $(t$ Amant%

8actors to be considered:

=urgency of story

=trustworthiness of source

=believability of the story

====loo/s to state of mind $subjective% of defendant

===measures attitude toward truth and not of plaintiff

"valuating Actual malice:

=Auty to consult with plaintiff or spea/ to sources favorable of

plaintiff)

=Bnfairness or bias in story

=<ll willOspite=common law malice

=8eliance in hostile source

valuating Actual Galice

Co duty to investigate truthfulness $even when a reasonably

prudent person would have% where:

=the source is trustworthy and

=the story is credible

8eliance on single source or confidential source $2t. Amant%

8eliance on reliable, previously published material

=6eaders Digest: Cal Case

Auty to consult with plaintiff or spea/ to sources favorable to

plaintiff)

Bnfairness or bias in story

=so long as he has no serious doubts concerning its truth he can present

#

but oneside of the story 8eaders Aigest

<ll will, spite, common law malice

<'ll get you and <'ll destroy you Jerbert v. :ando

8eliance in a hostile source not enough but can factor in

Co clear rule or definition

=fact=based analysis

=factors may add up to actual malice

=clear and convincing standard

Affirmative "vidence of %ack of Actual #alice:

=8eview by outside counsel

=?ublication of prompt correction

=Agreeing not to repeat statement

=8epeated attempts to interview plaintiff

=<nclusion of plaintiff's denials

=Aisclosure of bias

Damages

a% ActualO(eneralOCompensatory Aamages

=vidence of loss attributable to harm caused by defamation

=.ends to be imprecise

b% 2pecial Aamages=per +uad vs. per se p.6

=?laintiff must plead and provide evidence of precise monetary loss

attributable to defamation $a/a out=of=poc/et losses% $Civ. C. F

5Pa$5%$b%% $<n some cases, this is the only type of damages

recoverable%

c% ?resumed Aamages

=Aamages that may be recovered whether or not the plaintiff can prove

actual or special damages

=8e+uires proof of actual malice

=*e conclude that permitting recovery of presumed and punitive

damages in defamation cases absent a showing of actual malice does not

violate the 0irst Amendment when the defamatory statements do not

involve matters of public concern.Aun N Eradstreet, <nc. v. (reenmoss

Euilders, <nc., 5#6 B.2. #54 $!4P7%.

d% ?unitiveO;emplary Aamages

=Aamages that may be recovered whether or not the plaintiff can prove

actual or special damages

=8e+uires proof of actual malice

= <n CA, a plaintiff must establish actual malice and common law malice

and clear and convincing evidence to recover

-rivileges and Defenses:

a) Consent= best if clear or in writing or on tape

b) Civil Code F 5#: F5#$a%

?ublication in proper discharge of an official duty

P

;tends to high=level officials and lower=level officials acting in scope of

duties $Copp v. ?a;ton%

Absolute privilege

Civil Code F5# b= (tatements in legislative proceedings

Absolutely privileged if there is logical connection between

statement and proceeding

Civil Code F5#$b%6=(tatements in judicial proceedings (aka ;litigation

privilege)

Absolutely privileged if there is some connection to

e;isting proceedings or once

contemplatedOthreatened in good faith> Applies to any

claim arising from publication, e;cept malicious

prosecution 2plit: e;tent of application for out=of=court

statements to media

Civil Code F5#$b%$3%=(tatements in other official proceedings authori5ed b*

law

Absolutely privileged

&ther e;emptions

Civil Code F 5#$c%= rarel* invoked ;'ommon interest privilege<

Applies if statements is made to a person interested in the

communication:

$!% Ey one who is also interested in the communication

$6% Ey one who stands in such relation to the person interested

as to afford a reasonable ground for an innocent

motive for communication

$3% Ey one who is re+uired by the interested person to give the

information

@ualified privilege: defeated by common law maliceO just

malicious

Civil Code F 5#$d)=;8air and true report privilege<

A fair and true report by a public journal that captures the

gist or sting of public proceedings or documents

=0le;ibilityOliterary license

=6ule: .he report must be fair and true, not the underlying

material

Absolute privilege: can report even /now if it is underlying

information is false

=media merely conveying contents

Applies even to closed proceedings and partial documents

Communications to a public journal

Civil Code F 5#$e% 8air and true reports of the proceedings of a public

meeting and matters for the ;public benefit<

Absolute privilege

c) Ceutral 8eportage: Ceutral 8eportage

2uccinctly stated, when a responsible, prominent organization li/e the

4

Cational Audubon 2ociety ma/es serious charges against a public figure, the

0irst Amendment protects the accurate and disinterested reporting of those

charges, regardless of the reporter1s private views regarding their validity.

dwards v. Cat1l Audubon 2oc., <nc., 779 0.6d !!3, !6" $6d Cir. !4##%

0actors:

$!% Cewsworthy charges that create or are related to a public controversy

$6% Charges must be reported accurately and disinterestedly

='ianci: 0ailure to reveal facts can lead to failing this factor

$3% Accusation made by a responsible source

$5% .he charges are about a public official or public figure $/hawar%

d) *ire 2ervice Aefense: Cot fully recognized in California courts

,ire (ervice Defense>

0our factors:

$!% Gaterial from reputable news agency

$6% Co /nowledge of falsity

$3% 2tory appeared credible on its face

$5% ?ublished without substantial change

e) 0air Comment=superfluous now since 34 Times

Common :aw Aefense

0actors:

$!% 2tatements about people in positions of prominence $i.e., public officials

and public figures%

$6% Gade without actual malice

f) <nnocent Construction 8ule= 8ejected in CA

8ead in conte;t, if a statement can be given and innocent construction

then it cannot give rise to a defamation claim

8ejected in CA, but accepted in some other states li/e <llinois

g% :ibel ?roof ?laintiff=Cot good in CA

*ho is a libel proof plaintiff) 8eputation is so bad, it can't get worse

*hat is the incremental harm doctrine) 8eputation is so bad a little

defamation doesn't add to it

-rocedural )ssues:

Iurisdiction=

a% 0or defamation, jurisdiction is proper if effects of defamation are suffered in

forum state $Calder v. Iones%: 8ather, their intentional, and allegedly tortious,

actions were e;pressly aimed at California. ?etitioner 2outh wrote and petitioner

Calder edited an article that they /new would have a potentially devastating

impact upon respondent. And they /new that the brunt of that injury would be felt

by respondent in the 2tate in which she lives and wor/s and in which the 3ational

"n!uirer has its largest circulation. Bnder the circumstances, petitioners must

reasonably anticipate being haled into court there to answer for the truth of the

statements made in their article

!"

Calder v. Iones, 597 B.2. #P3, #P4=4"$!4P5%.

b% ?ublication, broadcast or circulation in a 2tate, gives courts of the 2tate

jurisdiction over the publisherObroadcaster $Reeton v. Justler%: here, as in this

case, respondent Justler Gagazine, <nc., has continuously and deliberately

e;ploited the Cew Jampshire mar/et, it must reasonably anticipate being haled

into court there in a libel action based on the contents of its magazine. ,orld=

,ide ?olkswagen 'orp$ v$ ,oodson, 555 B.2. 6P9, 64#=64P, !"" 2.Ct. 774, 79#,

96 :.d.6d 54" $!4P"%. And, since respondent can be charged with /nowledge of

the single publication rule, it must anticipate that such a suit will see/

nationwide damages. 8espondent produces a national publication aimed at a

nationwide audience. .here is no unfairness in calling it to answer for the contents

of that publication wherever a substantial number of copies are regularly sold and

distributed. Reeton v. Justler Gagazine, <nc., 597 B.2. ##", #P!, $!4P5%.

c% <nternet conte;t: j;n rests with the audience

!.*hether defendant purposefully conducted activities in the 2tate)

6.*hether the plaintiff's claims arise out of activities there)

3.*hether the e;ercise of j;n would be constitutionally reasonable)

d% <nternational considerations: lessons from Aow Iones v. (utnic/ $Australia%

:essons: chec/ location of subject, sense of self=censorship, how much assets do

we want in other countries

Aemands for 8etractionO CorrectionO Clarification=5P$a% <n any action for damages for

the publication of a libel in a newspaper, or of a slander by radio broadcastK.he court

first held that the protection against damages for libel that is afforded newspapers by Civ.

Code, F 5Pa, is limited to those who engage in the immediate dissemination of news, and

that the trial court properly concluded defendant publication was not a newspaper for

purposes of F 5Pa, since the evidence indicated it provided little or no coverage of

subjects such as politics, sports, or crime, that in general it did not ma/e reference to

time, and that normal lead time for its subject matter was one to three wee/s.

Eurnett v. Cat1l n+uirer, <nc., !55 Cal. App. 3d 44!, !43 Cal. 8ptr. 6"9 $Cal. Ct. App.

!4P3%

=*ithin 6" days of learning of publication or broadcast: $media gets special treatment%

?laintiff must serve written notice on publisher or broadcaster

2pecifying the defamatory statements

Aemanding a retractionO correctionO clarification

=*ithin 6! days after that, defendant may publish correction in as conspicuous a manner

as original publication or broadcast

=<f the correction is not published the plaintiff may recover actual and special

damages and may also recover punitive damages if he proves actual malice as

defined in Civ. Code. 5P $i.e. common law malice, with e;ception for good faith

belief in truth at the publication%

=<f the correction is published, then the plaintiff is limited to special damages

=<f the correction is not demanded, then the plaintiff is limited to special damages

!!

=Lou have to plead special damages with specificit* otherwise general claim wiil

fail: e;actly what happened, who defrauded, etc.

5P$a%= 8etract and demand, average person can't do this

2ingle ?ublication 8ule

8ule: 8eissues of the same publication do not give rise to a new cause of action,

but new versions or editions may give rise to anew rise of action

?urpose: sufficiently litigate all issues and damage claims arising out of

defamation in one proceeding

.his rule is an e;ception to the general rule that each communication of

defamatory matter is separate and distinct publication for which separate cause of

actions arises

Application in California)

=Civil Code 3567.!=3567.7=you have to fit under this

=Also applies to publication on <nternet

=3567.5: only once chance to sue

=3567.3: Co person shall have more than one cause of action for damages for

libel or slander or invasion of privacy or any other tort founded upon any single

publication or e;hibition or utterance, such as any one issue of a newspaper or boo/ or

magazine or any one presentation to an audience or any one broadcast over radio or

television or any one e;hibition of a motion picture. 8ecovery in any action shall include

all damages for any such tort suffered by the plaintiff in all jurisdictions.

2tatute of :imitations

=<n California, the 2&: for defamation is one year $Civ. C. F 35"$3%%

=2&: begins to run on first publication to the public $2hively v.

Eozanich%

=.he 2&: may be tolled where a defendant intentionally tries to hide his or her identity,

but only until the plaintiff learns, or through reasonable diligence could have learned, the

defendant's identity

=0or 2&: purposes:

.he distribution does not have to be in the forum state

.he rule of discovery does not apply to mass media defendants

.he rule of discovery applies when non=media defamation occurred such that

the plaintiff had no access, no cause to see/ access and there are no facts to

suggest that the plaintiff would have been put on in+uiry notice of the alleged

defamation $Jebrew Academy%

II. )ri*acy Torts

!6

A) 8alse %ight

@

= meant to protect how people feel, how they want to be portrayed to the

world

lements:

i. ?ublicizing

ii. 0alse 0acts

=2pahn: even good facts can cast a bad light

iii. About an identified individual

iv. <n a highly offensive manner

v. *ith fault

*hat are some of the difference between false light and defamation)

Corporations can't sue for false light> the don't have emotional interest in how

they are perceived

Gust be more publicity, needs to be more than ! person

/) -ublication of -rivate 8acts

i. -ublic disclosure (about the plaintiff)

=Aisclosure to the public in general or a large number of people as distinguished

from one individual or a few $?orten%

=*hat are the parameters)

=About the plaintiff)

=often not listed as a substantive element

=(hulman: not identified by full name or face, but the plaintiff was still

identifiable

ii. 7f ;private< (and true) information

A

=0acts that are already public or that leave plaintiff open to the public eye

are not private

==private facts seem to be se;, finances that would be highly offensive to a

reasonable person

iii. That would be highl* offensive to the reasonable person

B

7

(cope of 8alse %ight:

2hould the tort e;ist at all) 36 states recognize false light, !6 states reject

Time v$ Hill: alternate scenerio: what if person is raped

*hat about flattering, but false portrayals)

=2pahn: even flattery could suggest lying, or what if girl in time is raped)

Bnder California :aw>

Can't simultaneously claim false light and defamation on same set of facts

All defamation defenses apply

Aifference with statute of limitations, more time for false light

9

;amples: Gr. 2ipple=0ord's savior= homose;uality, not private because didn't

try to conceal, ?olice blotter, transgender $Aiaz v. &a/land .ribune%, /issing in

mar/etplace is not private, in a bathroom stall, military e;ercises, molested children

$vulnerable groups%, murder witness

#

*hat courts have found inoffensive)

=a report of a person's release after his arrest resulting from mista/en identity

!3

iv. And is not of legitimate concerns to the public (i$e$ not newsworth*)

=Congruent element and affirmative defense, but lac/ of newsworthiness

is an element $2hulman%

=<f a publication is newsworthy, it cannot serve as the basis for a

publication of private facts claim

=.est from (hulman:

a% the social value of the facts published

b% the depth of the article's intrusion into ostensibly private affairs

c% the e;tent to which the party voluntarily acceded to a position of

public notoriety

=paramount test from 2ipple: whether the matter is of legitimate public

interest, which in turn must be determined according to community

mores

= .here must be a logical relationship or ne;us between the events and the

person's notoriety $2hulman%

=.he standard is not necessity> the media has editorial discretion

$2hulman%

=does not constitute a morbid and sensational prying into private lives for

its own sa/e $2hulman 35"%

The press cant be held liable from truthful reporting of information lawfull*

obtained through government records unless there is interest of the highest

order $'o+ and 8lorida (tar case%

') )ntrusion

lements:

!. ?laintiff had a reasonable e;pectation of privacy

=?laintiff must show objectively reasonable e;pectation of seclusion or

solitude in the place, conversation or data source

= &f course legitimate countervailing social needs may warrant some

intrusion despite an individual1s reasonable e;pectation of privacy and

freedom from harassment. Jowever the interference allowed may be no

greater than that necessary to protect the overriding public interest. Grs.

&nassis was properly found to be a public figure and thus subject to news

coverage. (ee 2idis v. 0. 8. ?ublishing Corp., !!3 0.6d P"9 $6d Cir.%, cert.

denied, 3!! B.2. #!!, 9! 2.Ct. 343, P7 :.d. 596 $!45"%. Conetheless,

(alella1s action went far beyond the reasonable bounds of news

gathering. *hen weighed against the de minimis public importance of the

daily activities of the defendant, (alella1s constant surveillance, his

obtrusive and intruding presence, was unwarranted and unreasonable. <f

=a person returning S67","""

=a photograph of a postal employee at wor/

=article describing !6 year old giving birth

*hat courts have found to be offensive

= Article about woman with tapeworm

=display by protesters disclosing identities of planning aborting

=article that references child narcotic dude

!5

there were any doubt in our minds, (alella1s ine;cusable conduct toward

defendant1s minor children would resolve it. (alella v. &nassis, 5P# 0.6d

4P9, 447 $6d Cir. !4#3%

= to summarize, we conclude that in the wor/place, as elsewhere, the

reasonableness of a person1s e;pectation of visual and aural privacy

depends not only on who might have been able to observe the subject

interaction, but on the identity of the claimed intruder and the means of

intrusion. 0or this reason, we answer the briefed +uestion affirmatively: a

person who lac/s a reasonable e;pectation of complete privacy in a

conversation, because it could be seen and overheard by cowor/ers $but

not the general public%, may nevertheless have a claim for invasion of

privacy by intrusion based on a television reporter1s covert videotaping of

that conversation. 2anders v. Am. Eroad. Companies, <nc., 6" Cal. 5th

4"#, 463, 4#P ?.6d 9#, ## $!444%.

6. .he defendant intentionally intruded on plaintiff's private place, conversation or

matter

=unintended or mista/en foray does not give rise to liability

3. .he intrusion would be highly offensive to a reasonable person

=consider degree of intrusion, conte;t, conduct, motives of intruder and

e;pectations of plaintiff

=court determines in first instance

= courts must consider the e;tent to which the intrusion was, under the

circumstances, justified by the legitimate motive of gathering the news.

2hulman v. (roup * ?roductions, <nc., !P Cal. 5th 6"", 639=3#, 477

?.6d 594, 543 $!44P%

= .he mere fact the intruder was in pursuit of a story does not,

however, generally justify an otherwise offensive intrusion>

offensiveness depends as well on the particular method of investigation

used. At one e;treme, Troutine ... reporting techni+ues,' such as

as/ing +uestions of people with information $including those with

confidential or restricted information% could rarely, if ever, be deemed

an actionable intrusion. At the other e;treme, violation of well=

established legal areas of physical or sensory privacy = trespass into a

home or tapping a personal telephone line, for e;ample = could rarely, if

ever, be justified by a reporter1s need to get the story. 2uch acts would be

deemed highly offensive even if the information sought was of weighty

public concern> they would also be outside any protection the

Constitution provides to newsgathering.2hulman v. (roup *

?roductions, <nc., !P Cal. 5th 6"", 63#, 477 ?.6d 594, 545 $!44P%

?ublication is not an element hereUUU &nce you go through information you have

intruded

;amples:

0ilm crew accompanying paramedics into a house of person with heart attac/

!7

Adult daughter of heart attac/ victim who watch broadcast of father's ordeal

2e;y mom add in newspaper and people ended up showing up to house

2ecret recording of employee's conversations by cowor/er in employee=only

area $2anders 595%, yes=just because you're telling one person doesn't mean

whole world

2ecret recording of business discussion by stranger invited into bac/ office area

$Ged :abs= yes, business discussion and stranger%

(athering private information about a third person under false pretenses

8eporter secretly recording in person's living room

Co reasonable e;pectation in restaurant

D) ,iretappingC"avesdropping

0ederal :aw lements:=only need one=party consent

!. <ntentional

6. <nterception, disclosure, or use of

3. An oral, wire, or electronic communication or

5. <ntentional use of a device to intercept an oral communication

Aefense: one party consent beforehand, and not for criminal or tortuous

purpose

=Eartnic/i v. Hopper: media obtained secret recording from anonymous source

Jeld: disclosures of even illegally intercepted material is protected by the 0irst

Amendment if:

=Aefendant plays no part in the interception

=Aefendant obtains access to information lawfully

=<ntercepted matters relate to matter of public concern

2tate :aws:

Gost have one=party consent rule

About a dozen have all=party consent rule

Cal. ?enal Code F93!

.ypes of wiretapping:

Bnauthorized connection to telephone or telegraph

:earning or attempting to learn the contents of a wire transmission without the

consent of all parties

Ga/ing use of information obtained by such improper means

Aiding, abetting, or attempting to aidOabet any such conduct

Cal. ?enal Code F936

?rohibits

!. <ntentionally eavesdropping on or recording

6. Ey means of an electronic amplifying or recording device,

3. A confidential communication

V 8ecordings of contents of audible or symbol=based communications

$Arennan%

!9

V 2tatute says:

Q <ncludes communications that may reasonably indicate that any party to

the communication desires it to be confined to the parties thereto

Q ;cludes circumstance in which the parties to the communication may

reasonably e;pect that the communication may be

V &verheard or

V 8ecorded

Q ;cludes communications in public gathering or proceeding open to the

public

V 0lanagan resolved prior split in law, holding: a communication

is confidential where a party to the conversation has an objectively

reasonable e;pectation that the conversation is not being overheard

or recorded K regardless of whether the arty e+ects that the

content of the con*ersation may later !e con*eyed to a third

arty

V :ieberman defined overheard as listening without a spea/er's

/nowledge or intent that his speech be heard, as in eavesdropping,

which is to Tlisten secretly to what is said in private'

V Co 0irst AmendmentOnewsworthiness e;ception

5. *ithout the consent of all parties to the communication

= *hy does this matter)

=relevant to the +uestion of consent

=8elevant to the overheard +uestion

=:ieberman v. RC&?: 8eporter's friend was a party

=?atient's $reporter's% friends was a party

=A party to a communication need not spea/

=Bnli/e other privacy torts, corporations can sue $)on "!uip.%

*hat about calls from California to a one=party consent state) California law governs

Cal Civil Code F !#"P.P. ?hysical or constructive invasion of privacy> damages and

e+uitable remedies> employee=employer relationships> defenses: &nly pertains to personal

and familial activities

V Hiolations:

Q ?hysical trespass to capture personal or familial activity in a highly

offensive manner or

Q Capturing a person in a personal or familial activity in a private place

with an enhancing device $e.g., telephoto lens, parabolic microphone%

in a highly offensive manner, even if there is no physical trespass or

Q Airects, solicits or induces another to obtain such material

V ;ception: recording to e;pose unlawful behavior or business practice

threatening health or public welfare

V Aamages

Q .reble general and special damages

Q ?unitive damages

Q Aisgorgement of profits

Q 8ecently amended to provide civil fines of up to S7"/ for anyone who

!#

even solicits a violation

6ide Alongs:

*ith :aw nforcement:

Jere, law enforcement authority was used to assist commercial television, not to

further law enforcement objectivesK .he invited informer doctrine thus does not

shield the media from liability. *e recognized this more than twenty years ago

when we held that eavesdropping by the media for public broadcast, even in

conjunction with law enforcement, violates important privacy interests. Eerger v.

Janlon, !64 0.3d 7"7, 7!3 $4th Cir. !44#%

.he appropriate test in this case is the joint action test. .he 2upreme Court has

said it is satisfied when the plaintiff is able to establish an agreement, or

conspiracy between a government actor and a private party. Eerger v. Janlon, !64

0.3d 7"7, 7!5 $4th Cir. !44#%.

*e hold that it is a violation of the 0ourth Amendment for police to bring

members of the media or other third parties into a home during the e;ecution of a

warrant when the presence of the third parties in the home was not in aid of the

e;ecution of the warrant.

*ilson v. :ayne, 769 B.2. 9"3, 9!5, !!4 2. Ct. !946,

!944, !53 :. d. 6d P!P $!444%

,ight of )u!licity- the ,misappropriation of name tort- protects against intrusion upon

an individual1s private self=esteem and dignity, while the right of publicity protects

against commercial loss caused by appropriation of an individual1s ,identity- for

commercial e;ploitation. 5 I. .homas GcCarthy, GcCarthy on .rademar/s and Bnfair

Competition sec. 6P.9 $5th ed.6""3%Aoe v. .C< Cablevision, !!" 2.*.3d 393, 39P $Go.

6""3%

6est$ 7f Torts A@9'

7ne who appropriates to his own use or benefit the name or likeness of another is subject

to liabilit* to the other for invasion of his privac*$

Comment:

a$ .he interest protected by the rule stated in this 2ection is the interest of the individual

in the e;clusive use of his own identity, in so far as it is represented by his name or

li/eness, and in so far as the use may be of benefit to him or to others. Although the

protection of his personal feelings against mental distress is an important factor leading to

a recognition of the rule, the right created by it is in the nature of a property right, for the

e;ercise of which an e;clusive license may be given to a third person, which will entitle

the licensee to maintain an action to protect it.

b$ How invaded$ .he common form of invasion of privacy under the rule here stated is

the appropriation and use of the plaintiff1s name or li/eness to advertise the defendant1s

business or product, or for some similar commercial purpose. Apart from statute,

however, the rule stated is not limited to commercial appropriation. <t applies also when

the defendant ma/es use of the plaintiff1s name or li/eness for his own purposes and

benefit, even though the use is not a commercial one, and even though the benefit sought

to be obtained is not a pecuniary one. 2tatutes in some states have, however, limited the

liability to commercial uses of the name or li/eness.

!P

c$ Appropriation$ <n order that there may be liability under the rule stated in this 2ection,

the defendant must have appropriated to his own use or benefit the reputation, prestige,

social or commercial standing, public interest or other values of the plaintiff1s name or

li/eness. <t is not enough that the defendant has adopted for himself a name that is the

same as that of the plaintiff, so long as he does not pass himself off as the plaintiff or

otherwise see/ to obtain for himself the values or benefits of the plaintiff1s name or

identity. Bnless there is such an appropriation, the defendant is free to call himself by any

name he li/es, whether there is only one person or a thousand others of the same name.

Bntil the value of the name has in some way been appropriated, there is no tort.

d$ )ncidental use of name or likeness$ .he value of the plaintiff1s name is not appropriated

by mere mention of it, or by reference to it in connection with legitimate mention of his

public activities> nor is the value of his li/eness appropriated when it is published for

purposes other than ta/ing advantage of his reputation, prestige, or other value associated

with him, for purposes of publicity. Co one has the right to object merely because his

name or his appearance is brought before the public, since neither is in any way a private

matter and both are open to public observation. <t is only when the publicity is given for

the purpose of appropriating to the defendant1s benefit the commercial or other values

associated with the name or the li/eness that the right of privacy is invaded. .he fact that

the defendant is engaged in the business of publication, for e;ample of a newspaper, out

of which he ma/es or see/s to ma/e a profit, is not enough to ma/e the incidental

publication a commercial use of the name or li/eness. .hus a newspaper, although it is

not a philanthropic institution, does not become liable under the rule stated in this 2ection

to every person whose name or li/eness it publishes.

"lements of 'ommon %aw 'laim in 'alifornia: $this is more misappropriation%

!. Aefendant's use of plaintiff's for defendant's commercial advantage or otherwise

6. :ac/ of consent

3. 8esulting injury

Dachchini v. 2cripps=Joward Eroadcasting

2C&.B2 says human cannonball has cause of action because station broadcast

entire act without consent> the 0irst and 0ourteenth Amendments don't prohibit or

grant immunity to press

Guch of its economic value lies in the Tright of e;clusive control over the publicity

given to his performance'> if the public can see the act free on television, it will be

less willing to pay to see it at the fair. $39P%

Gontana Case:

Advertising for a protected publication using image is o/

Giddler Case:

Bni+ue voice presents an action

(tatutor* 'ause of Action

'ivil 'ode D ::11: <nter vivos statute

lements

!4

!. &ne who /nowingly uses

6. name, voice, signature, photograph, or li/eness of a

readily identifiable person

3. on or in products, merchandise, or goods, or for

purposes of advertising or selling, or soliciting

purchases of, products, merchandise, goods or

services

5. without such person1s prior consent

;ceptions:

K news, public affairs, or sports broadcast or

account, or any political campaign, shall not

constitute a use for which consent is re+uired

K Civ. C. 3355$d%

Gedia advertising e;ception $?age%

<ncidental use

W (roup shots

3355$b%$6% Q crowd at sporting event, crowd on street or

public building, audience at theater, glee club or

baseball team

W mployee photo

rebuttable presumption that use was not /nowing

Common law vs. statute

Complements one another

Aifferences:

Attorney's 0ees

2tatute X yes

Common law X no

Aescendability

Common law X no

2tatute X Les

California Civil Code F 3355.!

?ost mortem statute

(ives heirs who register a right to sue for use of deceased person's identity on or

in products, merchandise, goods or services $or advertising of same% if the

deceased person's identity had commercial value at the time of hisOher death and

if the deceased person was domiciled in California at the time of death

;ceptions:

?lay, boo/, magazine, newspaper, musical composition, audiovisual wor/, wor/

of political or newsworthy value, or an advertisement of the above if fictional or

nonfictional entertainment, or a dramatic, literary or musical wor/. 3355.!$a%$6%

Cews, public affairs, sports broadcast or account, political campaign. 3355.!$j%

6"

Aoes not apply to the medium of advertisements $e.g., newspapers, radio, etc.%

unless owners or employees had /nowledge use was unauthorized. $this is an

e;ception that gives immunities to newspaper and television station unless they

/new% 3355.!$l%.

;pires #" years after death. 3355.!$g%.

Aamages:

Any damages sustained:

=S#7" or actual damages and

Any profits not counted for

(eneral Aamages

?unitive Aamages

<njunctive 8elief= +uestionable

Defenses:

.ransformative use test: adds significant creative elements so as to be transformed into

something more than a mere celebrity li/eness or imitation $3 2tooges%

?redominant use test: speech with a predominant artistic purpose is protected while

speech with a predominant commercial purpose is not. $.wistelli%

8ogers .est $6nd Cir., 4th Cir., 22 Case%= 2o long as there is at least a minimal artistic

relevance, it's protected from right of publicity of trademar/, unless it is e;plicitly

misleading about endorsement or sponsorship. Bsed e;act names.

.ther Claims:

A) /reach of 'ontract

<t is, therefore, beyond dispute that ,t-he publisher of a newspaper has no

special immunity from the application of general laws. Je has no special privilege

to invade the rights and liberties of others. Associated -ress v$ 3%6/, supra, 3"!

B.2., at !36=!33, 7# 2.Ct., at 977=979. Accordingly, enforcement of such general

laws against the press is not subject to stricter scrutiny than would be applied to

enforcement against other persons or organizations. Cohen v. Cowles Gedia Co.,

7"! B.2. 993, 9#", !!! 2. Ct. 67!3, 67!P, !!7 :. d. 6d 7P9 $!44!%.

/) )ntentional )nfliction of "motional Distress>

*e conclude that public figures and public officials may not recover for

the tort of intentional infliction of emotional distress by reason of publications

such as the one here at issue without showing in addition that the publication

contains a false statement of fact which was made with actual malice, i$e$, with

/nowledge that the statement was false or with rec/less disregard as to whether or

not it was true. .his is not merely a blind application of the 3ew 4ork Times

standard, see Time, )nc$ v$ Hill, 3P7 B.2. 3#5, 34", P# 2.Ct. 735, 753, !# :.d.6d

579 $!49#%, it reflects our considered judgment that such a standard is necessary

to give ade+uate breathing space to the freedoms protected by the 0irst

Amendment. Justler Gagazine v. 0alwell, 5P7 B.2. 59, 79, !"P 2. Ct. P#9, PP6,

44 :. d. 6d 5! $!4PP%

6!

') Tresspass>

.he 0irst Amendment does not shield newspersons from liability for torts

and crimes committed in the course of news=gathering. .here is no threat to a free

press in re+uiring its agents to act within the law.2tahl v. 2tate, !4P3 &R C8 4",

997 ?.6d P34, P5!=56

0urther, the 0irst Amendment does not guarantee the press a constitutional

right of special access not available to the public generally. Goreover, this

property is not a traditional public forum such as public streets, sidewal/s, and

par/s, and there is no constitutional guarantee of access. 2tahl v. 2tate, !4P3 &R

C8 4", 997 ?.6d P34, P56

D) 8raud> 8ood %ion v$ A/'

Gaterial misrepresentation, suppression or omission of a fact, that induced

reasonable reliance, and that caused damage

Bnresolved: on S6 in damages against AEC in trespass and duty of loyalty

") Harassment

&f course legitimate countervailing social needs may warrant some

intrusion despite an individual1s reasonable e;pectation of privacy and

freedom from harassment. Jowever the interference allowed may be no

greater than that necessary to protect the overriding public interest. (alella v.

&nassis, 5P# 0.6d 4P9, 447 $6d Cir. !4#3%

8) 'onversion

lements: !% &wnership, possession, or right of possession at time of

interference> 6% Actual, substantial, and intentional interference> 3%

Aefendant's interferences was a substantial factor in damage to plaintiff

.he media is not above the law, bur routine newsgathering is o/

Gere publication of stolen information is o/ $Aodd%

0) )ncitement

Advocacy directed to inciting or producing imminent lawless action that is

li/ely to incite or produce such action $Erandenburg%

8ice v. ?aladin $Jit Gan% and Jerceg v. Justler $se;ual asphy;iation%

H) (on of (am %aws=distinction drawn by 2on of 2am law between income

derived from criminal1s descriptions of his crime and other sources has nothing to do

with 2tate1s interest in transferring proceeds of crime from criminals to victims

)) )llegal Activit*> /raun v$ (oldier of 8ortune #aga5ine

0acts: Advertisement for a for=hire hit man. <t is well=settled that the 0irst

Amendment does not protect commercial speech related to illegal activity, 'entral

Hudson, 55# B.2. at 795, and, thus, there is no constitutional interest in publishing

personal service ads that solicit criminal activityKwe conclude that the 0irst Amendment

permits a state to impose upon a publisher liability for compensatory damages for

66

negligently publishing a commercial advertisement where the ad on its face, and without

the need for investigation, ma/es it apparent that there is a substantial danger of harm to

the public.

Intellectual )roerty:

A) 'op*right=

&riginal wor/s of authorship in a tangible medium

(iving control to authors of the use, reproduction and distribution of original

wor/s

8ights:

Covers original wor/s of authorship fi;ed in a tangible medium

?rotects inter alia, right to reproduce, adapt, distribute, publicly perform and

publicly display

=individual authors, joint authors, employees and wor/s for hire

=:icenses

<nfringement

3ew 4ork Times v$ Tasini=0acts: freelance writers gave wor/s to CL .imes, .imes

put it on a searchable database independent of the collective wor/, 2C says does

violate copyright laws

8air Ese: Jarper 8ow and Acuff 8ose

0air Bse 0actors: =doesn't matter if license is rejected, taste shouldn't matter

!% ?urpose of the allegedly infringing use

=.ransformative XY adds something new, with a further purpose or difference

character, e.g. parody, criticism, commentary, news

6% Cature of the copyrighted wor/

=Creative wor/s have greater protection for factual wor/s

3% Amount and substantiality of the portion used

=0air use favors use of no more than necessary> not the heart of the wor/

=+uantitative and +ualititative evaluation

5% ffect on the mar/et of the wor/

=Aoes use ma/e mar/et less li/ely that consumers will buy original wor/)

After concluding that parody could be considered fair use, the Court

quickly qualifed its holding: if the new work has no critical bearing on

the substance or style of the original composition, which the alleged

infringer merely uses to get attention or to avoid the drudgery in

working

up something fresh, the work is less transformative, and other fair use

factors, such as whether the new work was sold commercially, loom

larger Id. at !"# $he Court e%plained further that while a parody

targets

and mimics the original work to make its point, a satire uses the work

63

to

critici&e something else, and therefore requires 'ustifcation for the very

act of borrowing See id. at !"( As a result, the Court appears to

favor

parody under the fair use doctrine, while devaluing satire

<n Los Angeles News Service v$ KCAL=TV Channel 9,3 the issue of whether the

rebroadcast of news footageZin this case, film clips of the beating of truc/ driver

8eginald Aenny during the :.A. riotsZconstitutes copyright infringement or [fair use.[

.he plaintiff, :os Angeles Cew 2ervice $:AC2%, shot the video of the beating from its

helicopter and licensed it to the various media. RCA: used the film without a license,

claiming that it was a fair use. <n an unpublished opinion, the district court found that the

defendants were e;cused under the fair use doctrine based upon [undisputed facts that the

Aenny Hideotape is a uni+ue and newsworthy videotape of significant public interest and

concern[ and granted summary judgment in favor of RCA:.3.!". .he Cinth Circuit

reversed the lower court1s summary judgment decision and remanded the case for trial.

De minimis Defense= so minimal and so fleeting it shouldn't give rise

/) Trademark=

Geant to protect proprietors of goods and services in the use of mar/s that

identify their products and services

?rotects consumers from being misled and confused

8ights:

2ource identifier

*ord, logo, design, phrase, etc.

Bsed in commerce or trade

Aistinctive

=more distinctive gets more protection> more descriptive gets less protection

Eurden of proving of li/elihood of confusion is on the party to prove li/elihood of

confusion

Ailution: by tarnishment $harm to reputation of famous mar/% and by blurring

:: Eean: parody is protected from dilution claim

8air Ese=

Trademark 8air Ese:

Cominative 0air Bse

?laintiff must show

?roduct was readily identifiable without the use of the mar/

Aefendant used more of the mar/ than necessary> and

Aefendant falsely suggested sponsorship holder

Classic fair use defense

Aefendant must show

Bse of the term is not as a trademar/ or service mar/

65

A uses the term fairly and in good faith and

A uses the term only to describe good

0irst Amendment Aefense

Aefendant must show:

Bse of trademar/ has some artistic relevance to the e;pressive wor/> and

Bse does not e;plicitly mislead as to the source or the content of the wor/

SLA))

,hat is (%A--.

Geritless lawsuits brought to chill the valid e;ercise of a defendant's

constitutional right of petition or free speech in connection with a public issue

2pecial motion to stri/e causes of action in a 2:A?? suit

,hen does it appl*.

.he defendant does not need to show that the plaintiff's cause of action was

intended to chill speech or petition rights

.he defendant bears the initial burden of ma/ing a prima facie showing that the

cause of action arises from defendant's petition

!. Defendants burden: $!% any written or oral statement or writing made before a legislative,

e;ecutive, or judicial proceeding, or any other official proceeding authorized by law, $6% any

written or oral statement or writing made in connection with an issue under consideration or

review by a legislative, e;ecutive, or judicial body, or any other official proceeding authorized by

law, $3% any written or oral statement or writing made in a place open to the public or a public

forum in connection with an issue of public interest, $e;amples of public forum: newspapers, press

conference, internet postings if other people can comment on it% or $5% any other conduct in

furtherance of the e;ercise of the constitutional right of petition or the constitutional right of free

speech in connection with a public issue or an issue of public interest.

?ublic <nterest test: all of these are or

$!% .he subject of the statement or activity precipitating the claim was a person

or entity in the public eye. $6ivero v$ American 8ederation of (tate, 'ount* and

#unicipal "mplo*ees, A8%=')7, supra, !"7 Cal.App.5th at p. 465, !3"

Cal.8ptr.6d P!, citing, inter alia, (ipple v$ 8oundation for 3at$ -rogress $!444%

#! Cal.App.5th 669, 634, P3 Cal.8ptr.6d 9## ,Gother Iones1 article on nationally

/nown political consultant-.%

$6% .he statement or activity precipitating the claim involved conduct that could

affect large numbers of people beyond the direct participants. $6ivero v$

American 8ederation of (tate, 'ount* and #unicipal "mplo*ees, A8%=')7,

supra, !"7 Cal.App.5th at p. 465, !3" Cal.8ptr.6d P!, citing, inter alia, Damon v$

7cean Hills &ournalism 'lub $6"""% P7 Cal.App.5th 59P, !"6 Cal.8ptr.6d 6"7

,statements in unofficial community paper about general manager of large senior

citizen community-.%

67

$3% .he statement or activity precipitating the claim involved a topic of

widespread public interest. $6ivero v$ American 8ederation of (tate, 'ount* and

#unicipal "mplo*ees, A8%=')7, supra, !"7 Cal.App.5th at p. 465, !3"

Cal.8ptr.6d P!, citing #$0$ v$ Time ,arner, )nc$ $6""!% P4 Cal.App.5th 963, 964,

!"# Cal.8ptr.6d 7"5 ,2ports <llustrated article on child molestation in youth

sports-.%

Commonwealth nergy Corp. v. <nvestor Aata ;ch., <nc., !!" Cal. App. 5th 69,

33, ! Cal. 8ptr. 3d 34", 345 $Cal. Ct. App. 6""3%

.ypical 2:A??: defamation, false light

9$ (hifts to -laintiffs burden

.he burden shifts to the plaintiff to establish a reasonable probability of

prevailing on the merits of each claim under attac/

<f the ?laintiff fails to meet its burden, the cause of action must be stric/en

from the Complaint

2tay on discovery:

=filing of notice of motion triggers automatic stay on all discovery in the

action

=.he court has the discretion to order specified: discovery upon noticed

motion and showing of good cause

Co :eave to Amend

=<f the anti=2:A?? statute applies, the plaintiff may not amend its

complaint

Jigh <nitial Eurdens on the ?laintiff:

=.he plaintiff must demonstrate a probability of prevailing with admissible

evidence

=?laintiffs have the burden of meeting all constitutional defenses as well

as non=constitutional defenses raised with admissible evidence

=<n cases where actual malice is an essential element of a defamation

claim the court must bear in mind the clear and convincing

standard of proof

Attorne*s 8ees:

<f defendant wins they get attorneys fees

A plaintiff can only get fees if they can show the 2:A?? was frivolous

8ight of Appeal

<mmediate right to appeal orders granting or denying an anti=2:A?? motion

?rocedural <ssue so can be used in federal court

8ederal 'ourts:

Gay be filed in federal court butK

!. Aoes not apply to federal +uestion claims

69

6. 2tay on discovery is +uestionable

3. Gay still get leave to amend

)rior ,estraints- A prior restraint is a government=imposed restriction on speech before the

speech has ta/en place

A. *hen, if ever, are prior restraints justified)

:ist from Cear:

=<n time of war=location of troops location $Cear=statute gives courts power to

enjoin scandalous and defamatory speech%

=Certain obscenity

=<ncitement to acts of violence

=&verthrow of an orderly government

E. Aefamation:

Are restraints on defamatory speech allowed after the trial on the merits)

a. .ory v. Cochran:

Aid a judge1s order that someone stop ma/ing defaming statements about a public figure,

even after that figure1s death, violate the 0irst Amendment right to free speech)

Les. <n a #=6 opinion delivered by Iustice 2tephen Ereyer, the Court held that

Cochran1s death diminished the grounds for the judge1s order and that the order

therefore amounted to an overly broad prior restraint on speech. .ory could no

longer try to force Cochran to pay him in e;change for desisting, the Court

reasoned, ending the order1s underlying justification.

b. E<H< v. :emen: 2ame as .ory e;cept speech concerned a public issue

Jolding: .he 2upreme Court of California followed suit by holding that a

properly limited injunction prohibiting defendant from repeating to third persons

statements about the Hillage <nn that were determined at trial to be defamatory

would not violate ,:emen's- right to free speech.

Cow, plaintiffs li/e the Hillage <nn have the option to see/ injunctions to prohibit

the repetition of statements that have been determined by a fact=finder to be

defamatory, without having to jump through 0irst Amendment hoops.

Concern that subject of defamatory speech will always have to bring lawsuits to

stop defamatory speech. Aamages are not an appropriate remedy in these cases.

C. ?rivacy

!. <n publication of private fact or false light cases: (ilbert v. Cational n+uirerOvans v.

vans

=Court will weigh competing constitutional rights of privacy and free speech in

deciding whether to issue injunction. 8elevant factors include:

whether the person is a public or private figure,

the scope of the prior restraint,

the nature of the private information,

whether the information is of legitimate public concern,

6#

the e;tent of the potential harm if the information is disclosed, and

the strength of the private and governmental interest in preventing

publication of the information.

=<n vans, Ct. of Appeal reversed an order preventing former wife from placing

any confidential personal information about e;=husband on the <nternet as

vague, overbroad, and not narrowly tailored

=?eople v. Eryant N Associated ?ress v. Aistrict Court

2tandard applied by the Colorado 2upreme Court:

$!% interest of the highest order $rape is of the highest order%

$6% restraint must be the narrowest available to protect that interest

$3% restraint must be necessary to protect against an evil that is great and

certain

$5% restraint cannot be mitigated by less intrusive measures

6. <ntrusion

(alella v. &nassis: Carrowed scope of injunction

*olfson v. :ewis: Court enjoined journalists because there is a public interest in

maintaining privacy

California harassment statute and Civil Code !#"P.P $prevents recording family

activities%

A. Cational 2ecurity

Cew Lor/ .imes v. B2:

/rennans 'oncurrence Test: &nly governmental allegation and proof that publication

must inevitably, directly and immediately cause the occurrence of an event /indred to

imperiling the safety of a transport already at sea can support even the issuance of an

interim order.

,hites concurrence: rejects government's grave and irreparable injury test and

reminds everyone of the potential conse+uences of subse+uent punishment for

publication

/lacks concurrence: absolutism

Harlans dissent: cabinet officers can assert irreparable impairment of national security

/lackmuns dissent: would have preferred more briefing

Bnited 2tates v. ?rogressive:

<n light of these factors, this Court concludes that publication of the technical

information on the hydrogen bomb contained in the article is analogous to

publication of troop movements or locations in time of war and falls within the

e;tremely narrow e;ception to the rule against prior restraint.

. .rade 2ecrets $Adidas%

(eneral rule is that press can't be enjoined for trade secrets

.he private litigants1 interest in protecting their vanity or their commercial self=

interest simply does not +ualify as grounds for imposing a prior restraint.

0. 0air .rials

6P

Cebras/a ?ress Ass'n v. 2tuart

8ecognized competing constitutional rights $fair trial v. free press%

.rial courts must e;amine evidence:

!. .he nature and e;tent of pre=trial news coverage

6. *hether other measures would be li/ely to mitigate the effects of

unrestrained pretrial publicity

Change of venue

?ostponement of trial

2earching +uestioning of prospective jurors

Bse of emphatic clear jury instructions

2e+uestration of jury

3. Jow effectively a restraining order would operate to prevent the

threatened danger

(. nforcing <njunctions that are prior restraints

B.2. v. Aic/inson:

Criminal contempt of even unconstitutional orders:

!. .he courts issuing the injunction must have subject and personal

jurisdiction

6. .here must be ade+uate and effective remedies available for orderly

review of the challenged ruling> and

3. .he order must not re+uire an irretrievable or irrevocable surrender of

constitutional guarantees $under lrod v. Eurns=even a moment can't

stand%

<n re ?rovidence Iournal Co.

transparently invalid order cannot form the basis for a contempt citation

Court said party should try to use appellate process, but if not available or ta/ing

to long they can still violate the order and still are its constitutionality in a

proceeding

,eorter/s )ri*ilege

?olicy:

2o people will come forward to furnish information

<ntegral to the news

<ndependence of the media

Eranzburg v. Jayes

&ustice ,hites #ajorit* 7pinion

Kreporter should not be forced to appear or testify until and unless

!. 2ufficient grounds are shown that reporter has relevant information

6. .he reporter's information is unavailable from other sources

3. .he need for the information is compelling to override 0irst Amendment

Cts. won't recognize a new privilege.

64

Cotes that it will be rare for journalists to be subpoenaed by grand juriesZ

only where the journalists are implicated in crime or possess relevant

information

Cotes how difficult it would be to define who +ualifies

8eporter's subject to general applicable laws

&ustice -owells 'oncurrence: @ualified ?rivilege

A reporter may +uash a subpoena where besides jury being in bad faith:

!. <nformation bears only a remote and tenuous relationship to the subject of the

investigation or

6. .estimony implicates confidential source without a legitimate need of law

enforcement

Douglas Dissent: Absolute 8ight not to appear before a grand jury

(tewarts Dissent> Ealancing .est=(overnment has the burden

$!% to show there is probable cause to show newsman has information that is clearly

relevant to a specific probably violation of law>

$6% show that the information cannot be sought by alternative means less destructive of

0irst Amendment rights> and

$3% demonstrate a compelling and overriding interest in the information

California 8eporter's 2hield :aw= Codified: Cal. Const. art. <, sec. 6$b% and vidence Code

section !"#"

$ ,ho is protected.: publishers, editors, reporters or other persons

connected with or employed by a newspaper, magazine, other

periodical publication, television station or networ/, radio station or

networ/, wire service or press association from contempt for

refusing to disclose sources or unpublished information

Cewspaper photographers $Cew Lor/ .imes v. 2uperior Ct.%

0reelance writer $?eople v. von Hillas and ?layboy nters., <nc. v. 2uperior Ct.%

Eoo/ author $2hoen v. 2hoen $4th Cir. !4PP%%

?ublishers, editors, reporters who gather, select, prepare, for purposes of

publication to a mass audience, information about current events of

interest and concern to that audience for an ongoing, recurring or

continuously update,d- <nternet website $&'(rady%

9$ ,hat information is protected.

<nformation obtained during newsgathering

2ource of information $confidential and non=confidential%

Bnpublished information

=<nformation obtained during newsgathering, but not disclosed to public

3"

=<ncludes notes, outlines, photographs, tapes or other data

=<ncludes newsgatherer's eyewitness observations in public place

:$-rotection involved> protection from contempt

Jow contempt wor/s:

=Gay involve jail andOor fines

=Criminal: up to 9 months in jail $meant to be punitive%

=0ederal: may be more than 9 months, but that re+uires a trial by jury

=Civil: unlimited jail time $until willing to abide by order% $meant to be coercive%

=0ederal: may not e;ceed life of proceeding or term of grand jury $6P B2C !P69%

=Iudge may switch civil contempt to criminal with a finding that the journalist has

an articulate moral principle and jail will not induce compliance $<nre0arr%

=Cot necessarily a protection from other types of sanctionsK.g., if a reporter is a

party to a lawsuit Q there can be monetary or procedural sanctions

1$ 7vercoming the shield law

Constitutionally=based so there must be a competing constitutional right

Absolute privilege for non=party reporter in civil proceeding or

subpoena by prosecution

@ualified privilege for non=party reporter when subpoenaed by criminal

defendant $or by prosecution when reporter testified for criminal defendant%

=Iournalist may be subject to contempt for not disclosing info if:

=Aefendant demonstrates a reasonable probability that the info will materially

assist the defense> and Aefendant's fair trial rights outweigh the reporter's

rights. 'ourt weighs>

a. *hether the unpublished information is confidential or sensitive

b. .he interests sought to be protected by the shield law

c. .he importance of the information to the criminal defendant $reasonable probability

the information will materially assist defense%

d. *hether there is an alternative source for the unpublished information

?rocedural aspects

=8eporter must get 7 days notice

=Court must issue written contempt order

3on=statutor* doctrine to protect confidential sources and unpublished information

=Although Cal. 2up. Ct. recognized +ualified privilege under the 0irst Amendment.

$Gitchell%

.ypically invo/ed where the shield law would not apply, e.g.:

0ederal law or law of state without a shield law

.hreatened sanction is something other than contempt