Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

U.S. Policy on Portuguese Colonialism

Enviado por

Tracy Johnson0 notas0% acharam este documento útil (0 voto)

32 visualizações9 páginasThis document summarizes the United States' voting record and policy positions regarding Portuguese colonialism at the United Nations over the past decade. It finds that while the US often expresses commitment to self-determination, it has consistently voted against and refused to support UN resolutions calling for actions to achieve independence for Portugal's colonies in Africa. The document analyzes several key UN votes and argues the US has tacitly supported Portuguese rule in Africa through its actions, despite rhetoric about hoping for peaceful change.

Descrição original:

Título original

American Committee on Africa -- US Policy and Portuguese Colonialism -- The United Nations Facade

Direitos autorais

© © All Rights Reserved

Formatos disponíveis

PDF, TXT ou leia online no Scribd

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoThis document summarizes the United States' voting record and policy positions regarding Portuguese colonialism at the United Nations over the past decade. It finds that while the US often expresses commitment to self-determination, it has consistently voted against and refused to support UN resolutions calling for actions to achieve independence for Portugal's colonies in Africa. The document analyzes several key UN votes and argues the US has tacitly supported Portuguese rule in Africa through its actions, despite rhetoric about hoping for peaceful change.

Direitos autorais:

© All Rights Reserved

Formatos disponíveis

Baixe no formato PDF, TXT ou leia online no Scribd

0 notas0% acharam este documento útil (0 voto)

32 visualizações9 páginasU.S. Policy on Portuguese Colonialism

Enviado por

Tracy JohnsonThis document summarizes the United States' voting record and policy positions regarding Portuguese colonialism at the United Nations over the past decade. It finds that while the US often expresses commitment to self-determination, it has consistently voted against and refused to support UN resolutions calling for actions to achieve independence for Portugal's colonies in Africa. The document analyzes several key UN votes and argues the US has tacitly supported Portuguese rule in Africa through its actions, despite rhetoric about hoping for peaceful change.

Direitos autorais:

© All Rights Reserved

Formatos disponíveis

Baixe no formato PDF, TXT ou leia online no Scribd

Você está na página 1de 9

ACOA BACKGROUND PAPER:

U.S. POLICY AND PORTUGUESE COLONIALISM: THE UNITED NATIONS FACADE

Introduction:

American attitudes towards Portuguese colonialism as expressed in policy state

ments and voting records at the United Nations are but an externalization of

the multiple policy factors which make up the substance of continued U.S.

support for Portugal. This paper outlines basically these United Nations

facets of U.S. policy. In subsequent ACOA reports we will investigate

American economic and military policy with particular attention to the U.S.

imports of Angolan coffee and the role of American oil corporations in the

Portuguese colonies, as well as the various forms of military aid to the

Portuguese war effort.

The U.S. Voting Record at the United Nations

America has often proclaimed its abhorrence of colonialism, its rooted

commitment to self-determination and freedom for all the peoples of the world,

To the millions of Africans struggling for freedom and independence in the

Portuguese-dominated territories in Africa, this must appear a commitment in

words only. A glance at the U.S.o voting record at the United Nations on the

position of these Portuguese territories reveals the very limited practical

meaning of this commitment. True, the United States voted "yes" to the

early 'declaratory' resolutions which affirmed the rights of all peoples

in the Portuguese-ruled territories in Africa and elsewhere to self-determin

ation. But it has consistently refused to support any resolution which

attempted action to achieve such self-determination for the people of Angola,

Guinea (Bissau) and Mozambique.

The U.S. voted "No" when the General Assembly called on all Member

States to "refrain forthwith from offering the Portuguese govern

ment any assistance that would enable it to continue its repression

of the peoples of the territories under its administration and for

this purpose to take all measures to prevent the sale and supply of

arms and military equipment to the Portuguese government." (Res. 1807 c/!962)

It has never subsequently given support to such a resolution.

The U.S. voted "No" when the General Assembly asked the Security

Council to take appropriate measures, including sanctions, to secure

Portugal's compliance with the demand for the granting of freedom

and independence to its colonies. (Res. 1819 c/1962) It has voted

"No" to all subsequent specific sanctions calls.

The U.S. voted "No" when the General Assembly condemned the role of

foreign economic interests which act as "an impediment to the African

people in the realization of their aspirations to freedom and inde

pendence" and called on all Member States to "prevent such activities

on the part of their nationals" (Res 2107 c/ 1965). It has not support

ed any of the subsequent condemnatory resolutions on foreign economic

aid to colonialism.

It has consistently refused to support all those resolutions which

called on NATO members (Portugal and the U.S. are allies in the North

Atlantic Treaty Organization) to refuse military aid and assistance to

Portugal for its colonial wars.

may, 1969

- 2 -

The arguments which the U.S. has used during the past ten years have varied,

but the effect has been the same -- continued tacit support for the Portuguese

in their defense of an African empire -- support for the colonialist rulers,

not for the colonial people,

Thus the U.S. supplies arms and money in the form of loans to Portugal and

defends such action at UN. meetings. The proviso to the Portuguese, on thq

basis of which the U.S. makes such defense, is that the American military and

financial aid may not be used for the prosecution of the colonial war in

Africa. This can be scant comfort to Africans fighting in Angola who now

face a non-American gun bought with escudos made available for guns. in

Africa because dollars helped pay for the butter in Portugal.

A clearer picture of the factors involved in the weak U.S. stance on Portu

guese colonialism emerges from a closer examination of the major resolutions

and debates at the United Nations in the last decade.

But lest the argunent be raised, 'that was the past, today is different', it

seems just to begin with the statement made on April 17, by U.S. Ambassador

Seymour M. Finger at a meeting of the Preparatory Committee for the 10th

Anniversary of the Declaration on the Granting of Independence to Colonial

Peoples and Countries.

Having recalled that in less than three decades, 65 former dependent territor

ies, 1/3 of the world's people, have become new independent states, he goes on:

"this massive surge of independence

took place largely without violence and

essentially through voluntary action by the former administering power. 5here

appeared to be a general recognition that colonialism had seen its day and

that the independence of colonial territories was not only the right of the.

peoples in those territories but also was beneficial to the world in general,

including the former administering powers."

Looking to the future he admits the existence of a "hard-core" problem in

southern Africa, but proceeds: "Nevertheless, we believe that the problems

of southern Africa do require more patience -- patience but not resignation

First of all, it is clear that countries outside southern Africa are in general

not prepared to wage the major and probably catastrophic war which would be'

required to dislodge the regimes now in power. Secondly, as odious as the

denial of human rights and self-determination in this area is, we do not

believe that the situation in Namibia and the Portuguese territories repre-7

sents a threat to international peace end security. Thirdly, we recall that

most of the members of the United Nations became independent through peace

ful means and, while such peaceful change remains possible -- however slow it

may be -- we are convinced that such peaceful means are in the best interest

of everyone concerned.

"Let us not proceed obstinately with tactics of the past -- of repeating

year after year resolutions which are known to be ineffectual on the day thpy

are adopted -- of adopting resolutions based on myths such as the red herrigigs

of foreign military bases and foreign economic investment. Such outworn

shibboleths cannot substitute for the hard thought we must all give to the

solution of the remaining hard-core problems. Though it may appear elemen-.

tary to say so, it would as o be wise not to slander those countries whose

cooperation is considered important in achieving the objectives of resolutions

- 3 -

to be adopted. This does not mean that there cannot be legitimate and constructive

criticism; indeed, there must be. But it does mean that we should keep our eye on

the real problems and act responsibly in terms of the real interests of dependent

peoples."

Thus the Ambassador and the government which he represents appear willing to con

sign millions oppressed by Portuguese colonialism to a further indefinite period

of such subjugation while they wait for the processes of peaceful change "however'

slow".

In fact,the African people of Angola, Mozambique and Guinea have already fought

long bitter years of war because the Portuguese met their legitimate demands for

self-determination and independence with brutality and violence. The Portuguese now

have more than 120,000 soldiers, a network of vicious secret security police (PIDE)

and thousands of armed settlers defending their empire in Africa. The U.S. position

which insists that peaceful change, however slow, is in the best interests of every

one concerned appears to ignore this completely, as it also ignores the fact that

the people of Angola, Mozambique and Guinea have already begun to exercise their

right to self-determination,

They have chosen to determine the nature of their

future by fighting for their freedom now rather than accepting more years of

colonial domination,

It is also ironic that the U.S. Ambassador should speak of "resolutions which are

known to be ineffectual on the day they are adopted" when it is precisely U.S.

refusal to support by word or deed such resolutions that frequently makes them

ineffectual.

WHAT THE VOTES MEAN

Demands of time and space limit the extent of this review of expressed U.S. policy:

detailed discussion of the reasons underlying particular U.S. positions must be

postponed to later papers. This description is confined to what was said, extract

ing from that record a picture of the predominant characteristics of the U.S. posture

of the last decade.

1. The U.S. has consistently adopted a "go slow" attitude which has alm6st

inevitably led it to adopting a 'soft' position vis-a-vis Portugal. This stance

has most often been phrased in terms of the American hope for peaceful change in

stead of a "blood bath". As we have pointed out above, it is the Portuguese deter

mination to maintain their African possessions that invalidates this hope. Yet

despite the evidence of eight years of conflict, the U.S. has clung to its original

position, and the language has changed very little since Adlai Stevenson spoke at

the first Security Council Meeting after the March 1961 rising in Angola. He said

then that he felt sure that "Portugal recognizes that it has a solemn obligation

to undertake the systematic and rapid improvement of the people of its territories".

He also spoke of the need to avoid a Congo situation by "step by step planning" or

change. (S.C., March 15, 1961)

Even when the U.S. voted for Resolution 1742 (Jan. 1962) which affirmed the right4

to "self-determination

and independence" and condemned "repressive measures",

arguments were raised against the use of "repressive" as "too strong" and "unwarranted",

- 4 -

despite strong evidence of Portuguese violence. Further, the U.S. was unhappy

about the inclusion of "independence", arguing that possibly the peoples of the

territories would choose to continue a close association with Portugal, thus the

U.N. should not pre-judge the issue.

In other debates at that time (Res. 1699, 1962), the U.S. delegate defended Portu

gal, which was under fire for not complying with the resolutions requiring it to

report on its Non-Self-Governing Territories to the Secretary General. The U.S.

position was that as Portugal claimed that the status of the Territories was such

that the reporting provisions were not applicable, there was no purpose in "singling

out Portugal for destructive criticism . It had instituted some reforms...which"

were not unwelcome..oit should be given more time."

This theme of Portuguese reform was echoed by Ambassador Adlai Stevenson at the

1963 Security Council Debates on the Portuguese Territories. Having stressed hip

belief in peaceful change, he continued, "The core of the problem is the accept

ance and the application of the right of self-determination

.... Mr. Nogueira, the

Foreign Minister of Portugal, has contended that the criteria and procedure de- 1

fined by the United Nations cannotooobe considered the only criteria for a valid.

and real self-determination.

I hope that he does not fear that any of us are

seeking to deprive Portugal of its proper place in Africa.... Portugal's role in

Africa will be ended only if it refuses to collaborate in the great and inevitable

changes which are taking place. If it does collaborate, its continuing rble is

assured, and I for one, sitting here, on my own behalf, would like to express with

pride the gratitude of my Government for the progress that Portugal is attempting

to make to improve the conditions of life among the inhabitants of its territories."

(S/PV.lo45, 26 July 1963)

2. The U.S. Opposes Sanctions.

Closely linked to this argument that Portugal was amenable to reason and would gradu

ally introduce change peacefully is the consistent U.S. opposition to any form of

sanctions, military or economic. (See voting chart) When the Committee of 24 on

Decolonization, seeking ways to make effective previous General Assembly and

Security Council resolution on the right of the people of the Portuguese terri

tories to self-determination

and independence, recommended that the Security Coun

cil should make military, economic and other sanctions mandatory, the U.S. opposed

the suggestion, strongly preferring to adopt the position that as a result of

negotiations in good faith, Portugal would be persuaded to put the provisions of

the resolutions into effect,

Two other issues which may help to explain this position of extreme caution must be

briefly referred to: the American stand on military involvement with Portugal and

its attitude to foreign economic involvement in the Portuguese territories.

3. Military Involvement and the Role of N.A.T.O.

As will be seen from reference to the attached voting record and explanations, the

U.S. cast a "No" vote for the first time on December 14, 1962, the crucial issue

at that point being the following paragraph of the Resolution (1807). Paragraph

7 called on member states to "refrain forthwith from offering the Portuguese

- 5

government any assistance that would enable it to continue its repression of the

peoples of the territories under its administration and for this purpose to take

all measures to prevent the sale and supply of arms and military equipment to the

Portuguese government." The first part of this paragraph was a type of formula

that had already twice been accepted by the U.S. Government (Resolution 1699 of

1961, and 1742 of 1962). Only the second section was new, and it met with a

very hostile response from the Americans

Since Res. 1807, much attention has been fucused on the continued ability of Portu

gal to find weapons with which to continue its colonial wars. The attack on countries

which supply arms has sharpened over the years, and a spotlight has been thrown on

the role of the NATO countries in this respect.

The U.S. has adopted the position that it does not supply arms for use in Africa,

and in fact obtains an understanding from the Portuguese government that all mili

tary assistance supplied in terms of the NATO alliance will only be used outside

Africa. To do more and apply a total arms ban to Portugal would amount to inter

ference in Portugal's internal security.

The main arguments developed by the protagonists of a total (instead of partial) arms

and aid ban can be briefly si-marized as follows:

i. Arms supplied to Portugal tend to spill over into African territories.

Much equipment is borderline in definition: heavy-duty trucks, for instance,

can be supplied as trucks, but are easily converted into troop carriers.

Most important of all, advice and training are indivisible. A man once

trained cannot seriously be expected to forget his knowledge as he steps

onto African soil. Yet the U.S., apart from its physical aid to Portugal

as a NATO member, also maintains a permanent Advisory Military Mission

(M.A.A.G.) in Portugal, and, as recently as February 1969, the Portuguese

press reported a visit by the U.S. military attache in Lisbon to Guinea,

Angola, and Mozambique.

ii. The Portuguese government now spends more than 45% of the annual

national budget on military and security expenditure, primarily for the

wars in Africa. Any aid in the form of guns, airplanes, ships or money

given for use outside Africa releases resources which it can then devote

to prosecuting the war. In November 1968 a new frigate, built in the

Portuguese shipyards and 50% UoS. financed under a NATO agreement, was

launched in the presence of Ambassador T. Bennett.

The U.S, contention that its military aid to Portugal in no way

helps that country in its wars on the African people looks less and

less convincing as the years pass, for America appears to be shaping its

policy primarily in response to a concern for a stable Portugal which

will serve as a friendly ally in the defense of Europe. Secondly, it

places much weight on the maintenance of its bases in the Azores -

another reason for remaining on amicable terms with Portugal, despite

the cost of such friendship. Thus in 1967, the Portuguese newspaper

Primeiro de Janeiro (15.4.67) reported a statement made by Robert

McNamara before a Committee in Congress: "The amount proposed for

U.S. military support for Portugal is justified by the use of Portu

guese bases which are of the greatest importance to American interests."

In effect, the preservation of these friendly relations and of the military

alliance means support for the Portuguese colonial wars.

-6-

4. The role of foreign investors in the Portuguese Territories.

The U.S. has totally rejected as untenable the belief held by an increasing

number of African, Asian and other countries that the participation of foreign

capital in the colonial territories tends to support and strengthen the colonial

rulers, and impedes the African people in the realization of their aspirations.

Yet, for example, such companies all join in the profit benefits derived

from using cheap African Labor. (In Angola, wages are often as low as

$23 a month for unskilled labor, may reach $116 a month for skilled

workers.

Foreign investors in plantations are a party to the continued land dis

possession of the African people.

All corporations pay taxes, including special defense allocations; tax

proceeds are used by the Portuguese to fight the colonial wars.

Foreign investors often provide strategic products or foreign exchange

which strengthens the Portuguese colonial econvmy.

American investment in Portugal and the Portuguese territories has grown

spectacularly since Portugal relaxed foreign investment controls in 1965,

much of this investment concentrating in mineral exploitation. The maj6r

oil and petroleum-producing company in Angola, for instance, is a Gulf

subsidiary -- 'Cabinda Gulf Oil Co.' which has a 50o profit-sharing

arrangement with the Portuguese government. The importance of Gulf to the

Portuguese is indicated by the recent statement of Premier Caetano to the

Portuguese press that his government's income from Angolan oil in 1969

would be 500,000,000 esc. ($17 million, appx.) and that oil production

would double in the next two years. In fact, Portugal expects to be

self-sufficient in oil and petroleum by 1970.

So vital is Gulf Oil that a large contingent of Portuguese troops has bebn

stationed in Cabinda since 1967 to protect the installations, and even '

Portuguese war communiques admit increasing guerilla pressure in the area

in 1968 and early 1969. Thus one giant American corporation depends on

the Portuguese colonial army to defend it against the African people.

In effect, the Umited States is at present supporting Portugal in its attempts

to maintain an African empire, despite the rebellion of its subjects in every

area and the opposition of most of the world. The U.S. is allied militarily

with Portugal; its economic interests in the African territories are growing;

and its influence has already prevented meaningful United Nations action to

aid the nationalist struggles for freedom.

American Committee on Africa

164 Madison Avenue

New York, New York, 10016

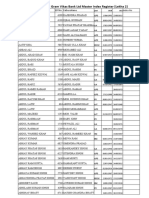

I~ID~C/0t7rLINE

('~F GENERAL ASS~24BLY BES0WI~IONE

Res. 1514

Res. 1541

Res. 1542

Res. 1603

Res. 1699

Res. 1742

* Res. 1807

* Res. 1819

Res. 1913.

Declaration on the granting of independence to colonial

countries and peoples.

General principles determining obligation of a member state

to transmit information re Non-Self-Governing Territories

to the Secretary General and definition of such Non-Self

Governing Territories.

Decision that Angola, Guinea and Mozambique are non-self

governing territories and there there is therfore an oblig

ation on the government of Portugal to submit information

to the Secretary General in accordance with Article 73 e

of the Charter.

Following Angola mass resistance and violent Portuguese re

pression, called on the Portuguese government to introduce

reforms leading to "transfer of all powers to the people of

these territories...without

any conditions...or

distinctions...

in order to enable them to enjoy complete independence and

freedom."

Deplored non-compliance

of the Portuguese government with

either the Charter or General Assembly resolution 1542.

Established Special Committee to collect information.

"Requests member-states to deny Portugal any support or

assistance which it may use for the suppression of the peoples

of its non-self-governing

territories."

Re-affirmation

of the right of the Angolan peoples to self

determination,

deplores "repressive measures"; called for re

form and for no support and assistance. (similar to 1699)

Reaffirmed peoples' rights, called on Portugal to grant in

dependence and negotiate with political parties for transfer

of power. Noting Portugal's non-compliance

with previous reso

lutions and the extensive use of Portuguese military and other

forms of repression, calls on member states "to prevent the

sale and supply of arms and military equipment to the Portu

guese government" that would enable it to continue repression.

Condemned mass exte-rnation in Angola, affirmed self-determin

ation, again called for end of all aid and assistance which

might be used for suppression, particularly "to terminate the

supply of arms to Portugal". Further requested the "Security

Council to take appropriate measures, including sanctions,

to secure Portugal' s compliance."

Similar to and confirming earlier resolutions - called on

Security Council to give effect to its own and the General

Assembly's resolutions.

-- 7 --

IBDEX/0UTLINE (W GENERAL ASSEMBLY RESOLUTIONS

- 8 -

Res. 2105 Broad resolution on colonialism, noted effect of ongoing immigration

and simultaneous dispossession of indigenous population--violation of

rights. Deplored continued co-operation with Portugal and South Africa,

requested all colonial powers to dismantle military bases, re-affirmed

the right to self-determination.

* Res. 2107 Much extended resolution, noting activities of foreign economic in

terests that acted as an impediment to the African struggle for free

dom. Detailed call. for sanctions -- including closure of ports and

airports to Portuguese transport, and a boycott of all trade. Called

on all states and particularly NATO members to stop the supply of

arms and military equipment.

* Res. 2184 Again condemned policy of dispossession, role of foreign economic

interests. Called on Security Council to make Res. 2107 sanctions

Mandatory.

Res. 2189

Res. 2240

Res. 2288

Res. 23U

Res. 2395

Noted grave consequences of Entente (Portugal, Southern Rhodesia, and

South Africa), called on member-states to withhold aid to the Entente,

strong stand against role of foreign economic interests.

Characterized Portuguese colonial wars as "crime against humanity".

Renewed condemnation of foreign economic interests, mnd called for

mandatory Security Council sanctions.

Condemned foreign economic exploitation which is impeding the imple

mentation of the Declaration on the Granting of Independence. (First

time this issue is on General Assembly Agenda as a separate item.)

Requests specialized agencies of the U.N. and international institu

tions to effectively assist the people's struggle and grant no assist

ance at all to Portugal and South Africa.

Re-affirmed rights of colonial people, expressed concern at continued

non-compliance of Portugal and continued destructive aetivities of

foreign economic powers. Called on all members to end the supply of

arms and aid for the colonial war. (This may be regarded as a 'soft

ened' resolution. It limited the cessation of supply of arms section

to "arms and aid for colonial war". It contained no specific sanctions

call. Canada, Norway and Sweden all reacted by voting Yes, but the

U.S. did not.

cr

LX

CA

--

p

Você também pode gostar

- (David Williamson) Access To History - IB Diploma - The Cold WarDocumento329 páginas(David Williamson) Access To History - IB Diploma - The Cold WarRustom Jariwala100% (8)

- Johnson El Statutory DeclarationDocumento12 páginasJohnson El Statutory DeclarationCorey ManningAinda não há avaliações

- International Law CasesDocumento3 páginasInternational Law Casessriram-chakravarthy-167775% (4)

- Golden Tara: Corazon Aquino's Contributions and ChallengesDocumento54 páginasGolden Tara: Corazon Aquino's Contributions and ChallengesAngelQueen Potter100% (1)

- Falklands War: Countdown & Conflict 1982Documento150 páginasFalklands War: Countdown & Conflict 1982Roger Lorton100% (1)

- U.S.-Portuguese Relations and African Liberation MovementsDocumento27 páginasU.S.-Portuguese Relations and African Liberation MovementsTracy JohnsonAinda não há avaliações

- Manning El Statutory DeclarationDocumento12 páginasManning El Statutory DeclarationCorey ManningAinda não há avaliações

- Fietas, Vea Bianca, V.Documento3 páginasFietas, Vea Bianca, V.Vea Bianca FietasAinda não há avaliações

- Neutral Rights and Obligations in the Anglo-Boer WarNo EverandNeutral Rights and Obligations in the Anglo-Boer WarAinda não há avaliações

- Home Missionary Society Claim (US Vs Great Britain) 1920Documento4 páginasHome Missionary Society Claim (US Vs Great Britain) 1920Ivy ZaldarriagaAinda não há avaliações

- Ebook Crafting and Executing Strategy Concepts and Cases The Quest For Competitive Advantage 21St Edition Thompson Solutions Manual Full Chapter PDFDocumento24 páginasEbook Crafting and Executing Strategy Concepts and Cases The Quest For Competitive Advantage 21St Edition Thompson Solutions Manual Full Chapter PDFclasticsipperw8g0100% (8)

- DISEC Study GuideDocumento10 páginasDISEC Study GuideammaraharifAinda não há avaliações

- Lol PeaceDocumento6 páginasLol PeaceEric DongAinda não há avaliações

- Sil Individual Reaction Paper - JulianDocumento3 páginasSil Individual Reaction Paper - JulianDiane JulianAinda não há avaliações

- Merrill and Patterson 2010Documento12 páginasMerrill and Patterson 2010MikeAinda não há avaliações

- Boerbritisherins 00 NeviialaDocumento578 páginasBoerbritisherins 00 Neviialadkbradley100% (1)

- Self-Determination and The FalklandsDocumento14 páginasSelf-Determination and The FalklandspunktlichAinda não há avaliações

- Hans J. Morgenthau: April 1967Documento13 páginasHans J. Morgenthau: April 1967Michael RossiterAinda não há avaliações

- The Fathers of the Constitution; a chronicle of the establishment of the UnionNo EverandThe Fathers of the Constitution; a chronicle of the establishment of the UnionAinda não há avaliações

- 70 YEARS of The United NationsDocumento7 páginas70 YEARS of The United Nationscss aspirantAinda não há avaliações

- McKinley War MessageDocumento1 páginaMcKinley War MessageSamael MorningstarAinda não há avaliações

- TestDocumento3 páginasTestDora PavkovicAinda não há avaliações

- Boerbritisherins 00 NeviuoftDocumento600 páginasBoerbritisherins 00 NeviuoftdkbradleyAinda não há avaliações

- Task 3 PILDocumento15 páginasTask 3 PILPatrick LealAinda não há avaliações

- q3m1l4 Kontrasabenevolentassimilation 130919191209 Phpapp02Documento27 páginasq3m1l4 Kontrasabenevolentassimilation 130919191209 Phpapp02Honiel Pagobo100% (1)

- Histo 12 - 2Documento2 páginasHisto 12 - 2Aimar ChidiAinda não há avaliações

- Philippine American WarDocumento69 páginasPhilippine American WarBeejay Raymundo100% (1)

- The Roots of Crisis - A NeoColonial StateDocumento6 páginasThe Roots of Crisis - A NeoColonial StateBert M DronaAinda não há avaliações

- This Content Downloaded From 136.158.35.208 On Sat, 15 Oct 2022 12:03:26 UTCDocumento20 páginasThis Content Downloaded From 136.158.35.208 On Sat, 15 Oct 2022 12:03:26 UTCMichael DalogdogAinda não há avaliações

- Constitutional Arrangements of the Republic of Ghana and the Federal Republic of Nigeria: 1844 – 1992 Third EditionNo EverandConstitutional Arrangements of the Republic of Ghana and the Federal Republic of Nigeria: 1844 – 1992 Third EditionAinda não há avaliações

- Writtten-Output-Number-1 (Joahna Mallorca)Documento8 páginasWrittten-Output-Number-1 (Joahna Mallorca)Joahna MallorcaAinda não há avaliações

- United Nations Conference On Political Disasters in AfricaDocumento44 páginasUnited Nations Conference On Political Disasters in AfricaMundo CmcAinda não há avaliações

- The Abolition Crusade and Its Consequences: Four Periods of American HistoryNo EverandThe Abolition Crusade and Its Consequences: Four Periods of American HistoryAinda não há avaliações

- The Dawn of A New New International Economic OrderDocumento32 páginasThe Dawn of A New New International Economic OrderWajid AliAinda não há avaliações

- 6th World Cultures Student Handout - RA ConflictDocumento8 páginas6th World Cultures Student Handout - RA ConflictAryan PatelAinda não há avaliações

- Latin America and the United States: Addresses by Elihu RootNo EverandLatin America and the United States: Addresses by Elihu RootAinda não há avaliações

- I. Assistance To States For Curbing The Illicit Traffic in Small Arms and Collecting ThemDocumento7 páginasI. Assistance To States For Curbing The Illicit Traffic in Small Arms and Collecting ThemBaka EroAinda não há avaliações

- Principle, For at The Time That They Were Determined Not To Be Slaves Themselves, TheyDocumento5 páginasPrinciple, For at The Time That They Were Determined Not To Be Slaves Themselves, TheyJbingfa Jbingfa XAinda não há avaliações

- AP Mutharika Role of International Law in 21st CenturyDocumento15 páginasAP Mutharika Role of International Law in 21st CenturyMwaba PhiriAinda não há avaliações

- Outline: 1) Introduction 2) The UN Peace Preserver? 3) U N Charter Remains Unexecuted 4) Successes: Prevention of Third World WarDocumento4 páginasOutline: 1) Introduction 2) The UN Peace Preserver? 3) U N Charter Remains Unexecuted 4) Successes: Prevention of Third World WarAnonymous 9Asxqe5fAinda não há avaliações

- From Isolation to Leadership, Revised A Review of American Foreign PolicyNo EverandFrom Isolation to Leadership, Revised A Review of American Foreign PolicyAinda não há avaliações

- Philippine Senate Rejects US Bases Treaty Extension in 1991Documento13 páginasPhilippine Senate Rejects US Bases Treaty Extension in 1991Lory Mae AlcosabaAinda não há avaliações

- Sambiaggio Case Short SummaryDocumento10 páginasSambiaggio Case Short SummaryJean Jamailah TomugdanAinda não há avaliações

- Morgenthau To Intervene PDFDocumento12 páginasMorgenthau To Intervene PDFMárcio Do ValeAinda não há avaliações

- Policy of Imperialism & Platform of The American Anti-Imperialist League - 1899Documento29 páginasPolicy of Imperialism & Platform of The American Anti-Imperialist League - 1899Bert M DronaAinda não há avaliações

- What if Latin America Ruled the World?: How the South Will Take the North Through the 21st CenturyNo EverandWhat if Latin America Ruled the World?: How the South Will Take the North Through the 21st CenturyAinda não há avaliações

- This Content Downloaded From 112.203.226.171 On Mon, 10 Mar 2014 07:33:23 AM All Use Subject ToDocumento6 páginasThis Content Downloaded From 112.203.226.171 On Mon, 10 Mar 2014 07:33:23 AM All Use Subject ToJeremy RhodesAinda não há avaliações

- Thesis Statement For The French and Indian WarDocumento8 páginasThesis Statement For The French and Indian Warfjh1q92b100% (2)

- Africa Freedom Day Rally 17, 1961Documento5 páginasAfrica Freedom Day Rally 17, 1961Matin SabinAinda não há avaliações

- Army Talks 10/27/43Documento16 páginasArmy Talks 10/27/43CAP History Library100% (1)

- History of The Filipino People, Teodoro Agoncillo Pages 2 Pages 1 Pages 2Documento67 páginasHistory of The Filipino People, Teodoro Agoncillo Pages 2 Pages 1 Pages 2John Carlo SandroAinda não há avaliações

- Maj. Gen. George S. Prugh, Law at War - Vietnam 1964-1973, Department of The Army, Washington, D.C., 1974Documento180 páginasMaj. Gen. George S. Prugh, Law at War - Vietnam 1964-1973, Department of The Army, Washington, D.C., 1974Mộng Huỳnh ThanhAinda não há avaliações

- Unit 18Documento11 páginasUnit 18Misbah EduAinda não há avaliações

- Ushc 1.3 - The Declaration of IndependenceDocumento33 páginasUshc 1.3 - The Declaration of Independencemancalleduncle57Ainda não há avaliações

- Position Paper For The First Committee of The General Assembly PlenaryDocumento5 páginasPosition Paper For The First Committee of The General Assembly PlenaryIorgus-Serghei CicalaAinda não há avaliações

- Human Rights Law CasesDocumento343 páginasHuman Rights Law CasesDia Mia BondiAinda não há avaliações

- American Committee On Africa - Statement of Mr. Holden Roberto, President of The Union of The Populations of AngolaDocumento5 páginasAmerican Committee On Africa - Statement of Mr. Holden Roberto, President of The Union of The Populations of AngolaTracy JohnsonAinda não há avaliações

- Constructive Speech FinalDocumento4 páginasConstructive Speech Finalsalvadoramaribeth635Ainda não há avaliações

- 5thGEWEXConf J.adamDocumento27 páginas5thGEWEXConf J.adamTracy JohnsonAinda não há avaliações

- De Las Antiguas Gentes Del PeruDocumento367 páginasDe Las Antiguas Gentes Del PeruTracy JohnsonAinda não há avaliações

- American Committee On Africa - Statement of Mr. Holden Roberto, President of The Union of The Populations of AngolaDocumento5 páginasAmerican Committee On Africa - Statement of Mr. Holden Roberto, President of The Union of The Populations of AngolaTracy JohnsonAinda não há avaliações

- American Committee On Africa - Power To The Portugese Empire From General ElectricDocumento5 páginasAmerican Committee On Africa - Power To The Portugese Empire From General ElectricTracy JohnsonAinda não há avaliações

- American Committee On Africa - Why We Protest Gulf's Operations in Portuguese AfricaDocumento4 páginasAmerican Committee On Africa - Why We Protest Gulf's Operations in Portuguese AfricaTracy JohnsonAinda não há avaliações

- American Committee On Africa - Portuguese-American Committee On Foreign AffairsDocumento3 páginasAmerican Committee On Africa - Portuguese-American Committee On Foreign AffairsTracy Johnson100% (1)

- American Committee On Africa - The Status of The Liberation Struggle in AfricaDocumento3 páginasAmerican Committee On Africa - The Status of The Liberation Struggle in AfricaTracy JohnsonAinda não há avaliações

- The Present Situation in AngolaDocumento7 páginasThe Present Situation in AngolaTracy JohnsonAinda não há avaliações

- American Committee On Africa - Statement On The Assassination of Amilcar CabralDocumento2 páginasAmerican Committee On Africa - Statement On The Assassination of Amilcar CabralTracy JohnsonAinda não há avaliações

- American Committee On Africa - Protest Portuguese Pressure On Ford FoundationDocumento2 páginasAmerican Committee On Africa - Protest Portuguese Pressure On Ford FoundationTracy JohnsonAinda não há avaliações

- American Committee On Africa - Southern Africa Bulletin 9Documento7 páginasAmerican Committee On Africa - Southern Africa Bulletin 9Tracy JohnsonAinda não há avaliações

- American Committee On Africa - Portugal's African Wards - A First Hand Report On Labor and Education in MocambiqueDocumento40 páginasAmerican Committee On Africa - Portugal's African Wards - A First Hand Report On Labor and Education in MocambiqueTracy JohnsonAinda não há avaliações

- American Committee On Africa - Portugals Wars in AfricaDocumento21 páginasAmerican Committee On Africa - Portugals Wars in AfricaTracy JohnsonAinda não há avaliações

- American Committee On Africa - NATO Ministers Council in Lisbon CondemnedDocumento2 páginasAmerican Committee On Africa - NATO Ministers Council in Lisbon CondemnedTracy JohnsonAinda não há avaliações

- American Committee On Africa - Non-Interference With Captured Cruiseship Urged On KennedyDocumento2 páginasAmerican Committee On Africa - Non-Interference With Captured Cruiseship Urged On KennedyTracy JohnsonAinda não há avaliações

- American Committee On Africa - NATO and Southern AfricaDocumento7 páginasAmerican Committee On Africa - NATO and Southern AfricaTracy JohnsonAinda não há avaliações

- American Committee On Africa - Portugal in AfricaDocumento8 páginasAmerican Committee On Africa - Portugal in AfricaTracy JohnsonAinda não há avaliações

- American Committee On Africa - More American Bases in Portugal - at What PriceDocumento3 páginasAmerican Committee On Africa - More American Bases in Portugal - at What PriceTracy JohnsonAinda não há avaliações

- American Committee On Africa - Memorandum On MPLA-FNLA UnityDocumento2 páginasAmerican Committee On Africa - Memorandum On MPLA-FNLA UnityTracy JohnsonAinda não há avaliações

- American Committee On Africa - Exxon Stay Out of AngolaDocumento2 páginasAmerican Committee On Africa - Exxon Stay Out of AngolaTracy JohnsonAinda não há avaliações

- American Committee On Africa - Massacre in MozambiqueDocumento12 páginasAmerican Committee On Africa - Massacre in MozambiqueTracy JohnsonAinda não há avaliações

- American Committee On Africa - Eduardo Chivambo Mondlane June 1920 - February 1969Documento6 páginasAmerican Committee On Africa - Eduardo Chivambo Mondlane June 1920 - February 1969Tracy JohnsonAinda não há avaliações

- American Committee On Africa - MAKONDE ART SHOW For The Benefit of FRELIMODocumento6 páginasAmerican Committee On Africa - MAKONDE ART SHOW For The Benefit of FRELIMOTracy JohnsonAinda não há avaliações

- American Committee On Africa - Examination of Portugal's Announced ReformsDocumento8 páginasAmerican Committee On Africa - Examination of Portugal's Announced ReformsTracy JohnsonAinda não há avaliações

- American Committee On Africa - Azores Agreement MeansDocumento4 páginasAmerican Committee On Africa - Azores Agreement MeansTracy JohnsonAinda não há avaliações

- American Committee On Africa - Independence of Guinea-BissauDocumento6 páginasAmerican Committee On Africa - Independence of Guinea-BissauTracy JohnsonAinda não há avaliações

- American Committee On Africa - Dr. F. Ian Gilchrist and The Situation in AngolaDocumento3 páginasAmerican Committee On Africa - Dr. F. Ian Gilchrist and The Situation in AngolaTracy JohnsonAinda não há avaliações

- American Committee On Africa - Charges Made by The Portuguese American Committee On Foreign AffairsDocumento2 páginasAmerican Committee On Africa - Charges Made by The Portuguese American Committee On Foreign AffairsTracy JohnsonAinda não há avaliações

- Allocation Sheet-ESE-2016-CivilDocumento23 páginasAllocation Sheet-ESE-2016-CivilAbhay KumarAinda não há avaliações

- Missing/Mismatch Set Code Category-List of Candidates Who Are DisqualifedDocumento41 páginasMissing/Mismatch Set Code Category-List of Candidates Who Are Disqualifedharshit tharejaAinda não há avaliações

- Statistik D1-D6 PHGDocumento40 páginasStatistik D1-D6 PHGAminuddin Abu BakarAinda não há avaliações

- Z G E 2021 P - E S A: Ambia Eneral Lections RE Lections Ituational NalysisDocumento45 páginasZ G E 2021 P - E S A: Ambia Eneral Lections RE Lections Ituational NalysisMulenga stevenAinda não há avaliações

- 50 Years After Our Independence: What Is The Buganda Question?Documento7 páginas50 Years After Our Independence: What Is The Buganda Question?Sam KAinda não há avaliações

- Chapter 13Documento14 páginasChapter 13s7rxfv6f66Ainda não há avaliações

- Clinton Email PDFDocumento1 páginaClinton Email PDFAlexa SchwerhaAinda não há avaliações

- Register of Members Interests Dáil TD 2005Documento94 páginasRegister of Members Interests Dáil TD 2005lostexpectationAinda não há avaliações

- AP Election Survey - 2024Documento7 páginasAP Election Survey - 2024Tarun Kumar ReddyAinda não há avaliações

- Activity 2Documento3 páginasActivity 2Jembie TanayAinda não há avaliações

- SGPD 2023 GuideDocumento5 páginasSGPD 2023 GuideRaunak LumdeAinda não há avaliações

- UCSP LAS 1 Quarter 2Documento4 páginasUCSP LAS 1 Quarter 2Janna GunioAinda não há avaliações

- Class IX Writing Tasks - Bio SketchDocumento2 páginasClass IX Writing Tasks - Bio SketchPta PAinda não há avaliações

- DBQ EssayDocumento3 páginasDBQ Essayapi-319153490Ainda não há avaliações

- Imperialism in Southeast AsiaDocumento9 páginasImperialism in Southeast AsiaBattle MedicAinda não há avaliações

- 7ma AvandadaDocumento20 páginas7ma AvandadaJhoseph DuranAinda não há avaliações

- Nouns in AppositionDocumento2 páginasNouns in AppositionHsu Myat Yee80% (5)

- LWR Module 8 The Propaganda Movement and La SolidaridaDocumento2 páginasLWR Module 8 The Propaganda Movement and La SolidaridaSandreiAngelFloresDuralAinda não há avaliações

- The Role of Bureaucracy in PakistanDocumento5 páginasThe Role of Bureaucracy in PakistanNouman HabibAinda não há avaliações

- Epf No ListDocumento181 páginasEpf No ListsalmanAinda não há avaliações

- Vincent Final DocumentDocumento70 páginasVincent Final Documenttrust alpha chiromoAinda não há avaliações

- Prime Ministers of IndiaDocumento28 páginasPrime Ministers of IndiaRudraksh KhariwalAinda não há avaliações

- Type of SettlementDocumento8 páginasType of SettlementBayyinah ManjooAinda não há avaliações

- Generation X Midterm ResultsDocumento28 páginasGeneration X Midterm ResultsTon LazaroAinda não há avaliações

- Article Vi - Legislative Department: Section 1Documento4 páginasArticle Vi - Legislative Department: Section 1Derick BalangayAinda não há avaliações

- Soal Essay RecountDocumento4 páginasSoal Essay RecountNunik Setiyani100% (1)

- Reflection On Lecture 5Documento2 páginasReflection On Lecture 5Minh quang PhạmAinda não há avaliações

- None 136d0737Documento10 páginasNone 136d0737Dhiya AldilaAinda não há avaliações