Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Innovation Growth, Ecosytem and Knowledge EconomiesReport

Enviado por

Soumya SahuDireitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Innovation Growth, Ecosytem and Knowledge EconomiesReport

Enviado por

Soumya SahuDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Creating an Innovation

Ecosystem: Governance

and the Growth of

Knowledge Economies

The Frederick S. Pardee Center

for the Study of the Longer-Range Future

A PAR DE E C E NT E R R E S E AR C H R E P OR T

Azatuhi Ayrikyan and

Muhammad H. Zaman

October 2012

Creating an Innovation

Ecosystem: Governance

and the Growth of

Knowledge Economies

The Frederick S. Pardee Center

for the Study of the Longer-Range Future

Azatuhi Ayrikyan and

Muhammad H. Zaman

October 2012

A PAR DE E C E NT E R R E S E AR C H R E P OR T

The Pardee Center serves as a catalyst for studying the improvement of the human condition through

an increased understanding of complex trends, including uncertainty, in global interactions of politics,

economics, technological innovation, and human ecology.The Pardee Centers perspectives include

the social sciences, natural science, and the humanities vision of the natural world.The Centers

focus is dened by its longer-range vision. Our work seeks to identify, anticipate, and enhance the

long-term potential for human progresswith recognition of its complexity and uncertainties.

67 Bay State Road tel +1 617.358.4000 www.bu.edu/pardee

Boston MA 02215 fax +1 617.358.4001 @BUPardeeCenter

USA pardee@bu.edu

The Frederick S. Pardee Center

for the Study of the Longer-Range Future

2012 Trustees of Boston University

ISBN 978-1-936727-07-0

The ndings and views expressed in this report are strictly those of the author(s) and should not be assumed to represent

the position of Boston University, or the Frederick S. Pardee Center for the Study of the Longer-Range Future.

This report was printed using 100% wind-energy on partially recycled paper.

Report design: www.neutra-design.com

Table of Contents

PAGE

Section 1 Introduction 1

Section 2 Methodology 2

2.1 Sample Selection 4

Section 3 Results 5

3.1 Improving Innovation through R&D Expenditures 5

3.2 Investing in Human Capital through Education 6

3.3 Encouraging Business Expenditures in R&D through Good Governance 8

3.4 Encouraging Innovation through Good Governance 10

3.5 Enhancing Exportation of High Tech Products through Good Governance 11

Section 4 Consideration of Confounding Values 14

Section 5 Conclusions 14

References 16

Acronyms

GI 1: Governance Indicator 1, Voice and Accountability

BERD: Business Expenditures in Research and Development

GERD: Government Expenditures in Research and Development

GDP: Gross Domestic Product

STEM: Science Technology Engineering and Mathematics

UNESCO: United Nations Educational, Scientic and Cultural Organization

WB: World Bank

WIPO: World Intellectual Property Organization

List of Figures and Tables

PAGE

Table 1 Input Variables for Government Inuence on Growth of Knowledge Economies 2

Table 2 Measures of Knowledge Economy Growth 3

Table 3 Role of Government and Business Expenditures on Patent Filings

as Measure of Innovation by State 5

Table 4 Government Spending and Growth of Knowledge Economies 6

Figure 1 Education Expenditures and the Growth of Knowledge Economies 7

Figure 2 Positive Inuence of Governance on BERD 8

Figure 3 Negative Inuence of Governance on BERD 9

Figure 4 Positive Inuence of Governance on Patent Filings 10

Figure 5 Positive Inuence of Governance on High Tech Exports 11

Figure 6 Negative Inuence of Governance on High Tech Exports 13

Cr e a t i ng a n I nnova t i on Ec os ys t e m: Gove r na nc e a nd t he Gr owt h of Knowl e dge Ec onomi e s

P A R D E E C E N T E R R E S E A R C H R E P O R T | O C T O B E R 2 0 1 2 | P A G E 1

Section 1: Introduction

The role of innovation in economic growth of countries across the globe has been an important part

of the conversation in many academic and policy circles (Julien 2007). Silicon Valley in California,

Koreas Digital Media City, Japans Kansai Science City, the Otigba Computer Village Cluster in

Nigeria, Indias IT hub of Bangalore, and Nairobis Silicon Savannah all serve as models of economic

development founded on innovation.

1

In recent years, many regions have shifted their economies to

more knowledge-based wealth creation as their more traditional means of livelihood have become

unsustainable (Volinets 2006). Such regions include the Catalonian region of Spain, where a biotech

hub has emerged in the last 20 years while its tourism industry has been overshadowed by newer

members of the European Union such as Croatia (Mas 2009). Several emerging economies have

also invested large amounts of government resources on the development of a knowledge economy,

including Chile, whose investment in public education is a model in Latin America (Perez-Aleman

2005), and Ethiopia, where in order to meet the medical needs of its population the government is

building generic drug fabrication facilities and plans to turn this production facility into a driver of

economic growth by eventually being a producer of generic drugs for the rest of sub-Saharan Africa

(Sbhatu 2010).

The examples above demonstrate a trend

that has inspired many questions about

the growth of knowledge economies,

including how much governments

can inuence their growth. What

does it take to create a successful

knowledge economy? What can national

governments and international organizations do to ensure success of this mission that has clearly

taken on global importance? And in the long run, how is good government connected to the growth

of knowledge economies? How are knowledge economies better for a nation than an economy based

on tourism or raw material resources such as oil? In Development as Freedom, Amartya Sen argues that

economic development is more than an increase in GDP per capita, and that the wealth of a nation is

not measured by the contents of its cofers, but by the freedom of its citizens. It is our hypothesis that

this freedom, measured by the Voice and Accountability indicators as established by the World Bank,

forms an integral part of both the growth of knowledge economies and the strength of a free society.

To test this hypothesis, we have examined the correlation between the growth of knowledge

economies and improvements in governance. Knowledge economies are dened generally as an

economy whose development relies on the ability to create and use knowledge. This denition

was rst employed by Virginier (2002) in his work on the evolution of a knowledge economy in

France, wherein the term knowledge economy was crystallized. We further narrow this denition

to a state where scientic research and development provide jobs and create wealth for a nation.

In particular we examine the factors that can be controlled by government policies, which include

but are not limited to political freedom, government spending on research and development (R&D),

and government spending on tertiary education. We examine the bi-directional interaction between

these factors and their efect on knowledge economies.

... how is good government connected to

the growth of knowledge economies?

1

Sources for these examples include MIT Center for Real Estate Studies; Zhihua Zeng 2008; Dahlman and Utz 2005; and

The Economist 2012.

Section 2: Methodology

In this analysis, we test the hypothesis that the growth of knowledge economies is afected by

governance; that is, knowledge economies are a function of good governance, where governance is

the input variable that can result in the growth of knowledge economies as the output variable. We

acknowledge there are other factors that can also be deemed independent variables in the growth

of knowledge economies. If these variables, when increased, result in an increase of knowledge

economy indicators, they may serve as counter-hypotheses to our original claim. The two other

variables examined in this paper are government expenditure on R&D and tertiary education

expenditures. These two indicators are the more generally accepted methods of measuring a

governments investment in its knowledge economy.

To track governance over time, we used the Governance Indicator for Voice and Accountability

established by the World Bank. According to the World Bank, Voice and Accountability captures

perceptions of the extent to which a countrys citizens are able to participate in selecting their

government, as well as freedom of expression, freedom of association, and a free media. This

indicator is determined for each country annually by aggregating a large set of data collected by

outside parties. These organizations include: other governments; non-governmental organizations

(NGOs) such as Freedom House and Reporters without Borders; academic research institutions

such as Vanderbilt University; international organizations such as the World Bank, the European

Bank for Reconstruction and Development, and African Development Bank; and a variety of others.

For more information about how this indicator is measured, please see the report by Kaufman et al

(2010) cited in the References section.

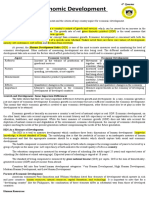

Table 1 shows the indicators for government input used in this analysis.

Table 1: Input Variables for Government Inuence on Growth of Knowledge Economies

Government Input indicator Value and Scale Data Source

Governance Indicator: Voice and Accountability 2.5 to 2.5 World Bank

Tertiary Education Expenditures % GDP UNESCO

Government Investment in R&D (GERD) % GDP World Bank

Our goal was to determine whether the variables outlined above correlate to changes in established

indicators for knowledge economies. The primary indicator for knowledge economy growth was

business expenditure in R&D. If we dene a national economy by the strength of non-government (i.e.

private sector) institutions involvement in wealth creation, business investment in R&D (BERD) is

a useful form of knowledge economies; that is, the creation of wealth through knowledge. However,

BERD data is limited primarily to Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD)

member states. In addition to BERD, we examine the level of patent lings as a potential indicator

of growth in knowledge economies. This demonstrates the level of innovation occurring in a nations

economy. It also indicates a protection of intellectual property for potential commercial gain,

Cr e a t i ng a n I nnova t i on Ec os ys t e m: Gove r na nc e a nd t he Gr owt h of Knowl e dge Ec onomi e s

P A R D E E C E N T E R R E S E A R C H R E P O R T | O C T O B E R 2 0 1 2 | P A G E 2

which in turn points to the belief by a population that there will be possible wealth creation through

knowledge. While ideally this indicator would be examined only for patent lings by the private

sector, in most cases data availability required us to examine all patent lings from each examined

state. Another indicator for knowledge economies is the translation of R&D eforts through high tech

product manufacturing and export. This indicates more than hope for potential commercial gain, in

comparison to patent lings; rather, it demonstrates existent success in the global market through

the accumulation of wealth by knowledge creation and translation. It is important to note that BERD

is also a variable in the growth or decline of the other two variables we have indicated above, patent

lings and high-tech exports. We explore this relationship in our analysis as well.

The indicators used for measurement of knowledge economies are shown in Table 2. In addition to

the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) and the World Bank (WB),

data sources include the United Nations Educational, Scientic and Cultural Organization (UNESCO)

and the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO). Data for most developing countries came

from UNESCOs Institute for Statistics.

Table 2: Measures of Knowledge Economy Growth

Knowledge Economy Indicator Value and Scale Data Source

Business Enterprise Investment in R&D (BERD) % GDP OECD/UNESCO

Patent Filings Number of annual lings UNESCO/WB/

WIPO

High Tech Exports As percentage of overall

manufactured exports

World Bank

Having established the two sets of input and output variables we examine, we then track the growth

of knowledge economies from 1996 to 2010 and their correlation to the input variables we have

outlined above: governance, government expenditure on R&D and tertiary education expenditures.

Our time range is limited by data availability, but we anticipate that prior data will not signicantly

change our ndings.

P A R D E E C E N T E R R E S E A R C H R E P O R T | O C T O B E R 2 0 1 2 | P A G E 3

Cr e a t i ng a n I nnova t i on Ec os ys t e m: Gove r na nc e a nd t he Gr owt h of Knowl e dge Ec onomi e s

2.1 SAMPLE SELECTION

To test our hypothesis, we examined emerging economies and emerging democracies. Countries

that have an established knowledge economy such as Singapore and Israel (Cook and Loet 2006)

served as a positive control for factors such as high GERD and resultant high levels of high tech

exports and patent lings. In the category of emerging economies, we examined Russia and India as

our sample cases. Lower income countries with targeted economic growth in the last 10 years were

also included in the study, subject to data

availability. We also examined emerging

democracies. By this we mean states that

have transitioned from dictatorships to

democracies in the last 20 to 30 years. The

most obvious group of nations that fall under

this category are the post-Soviet states

as well as other countries behind the Iron

Curtain during the cold war such as Estonia,

Slovakia, Romania and Poland. In addition,

several sub-Saharan states fall under this

category, namely Ethiopia, Uganda and South Africa. The cross section of emerging economies with

emerging democracies is precisely the grouping within which emerging knowledge economies can

be found.

Our choice of states to test this hypothesis was greatly inuenced by data availability. For this

reason, OECD states are a large majority of the nations examined.

Cr e a t i ng a n I nnova t i on Ec os ys t e m: Gove r na nc e a nd t he Gr owt h of Knowl e dge Ec onomi e s

P A R D E E C E N T E R R E S E A R C H R E P O R T | O C T O B E R 2 0 1 2 | P A G E 4

The cross section of emerging economies

with emerging democracies is precisely

the grouping within which emerging

knowledge economies can be found.

Section 3: Results

The data demonstrates that our hypothesis is not relevant to established democracies. This is to be

expected. The rise of knowledge economies is in line with a trend driven not by governments but

by crowd-sourcing and popular movements. In a state that is transitioning from a state-controlled

to a free market economy, many people yearn to act on the inspiration of the worlds examples of

success purely from intellectual endeavors. This predilection towards technology entrepreneurship

has risen to the forefront only in the last 20 years. The efect of being allowed to pursue ones

passions can only truly be measured in countries where that right is newly established. In states

where a free-market economy has been the norm, the growth of any particular sector is unlikely to

be afected.

3.1 IMPROVING INNOVATION THROUGH R&D EXPENDITURES

Our data shows across the board

that patent lings increased with

increased government spending in

R&D (GERD). In the cases where

governance decreases but government

spending increases, the patent lings

are unafected.

However, when a government spends

less on R&D, but BERD increases,

the patent lings still increase. We

examine how the government creates

an environment conducive to private

sector support of R&D by testing our

hypothesis of the role good governance

can play in enhancing BERD.

Later in this report, we demonstrate

that patent lings may increase

without increased government or

business expenditures in R&D, as is

apparent from the data for Slovakia in

Table 1. This exception supports our

hypothesis that governance can play as

important a role as spending on R&D in

the creation of knowledge economies.

Cr e a t i ng a n I nnova t i on Ec os ys t e m: Gove r na nc e a nd t he Gr owt h of Knowl e dge Ec onomi e s

P A R D E E C E N T E R R E S E A R C H R E P O R T | O C T O B E R 2 0 1 2 | P A G E 5

Table 3: Role of Government and Business Expenditures

on Patent Filings as Measure of Innovation by State

N/A

Country GERD BERD Patent Filings

Estonia

France

Israel

Mexico

Poland

Romania

Russian

Singapore

Slovakia

South Africa

3.2 INVESTING IN HUMAN CAPITAL THROUGH EDUCATION

We can isolate the cases in which knowledge economies have certainly grown by examining solely

those states in which all three indicators, (patent lings, BERD, and high tech exports) have risen

from 1996 to 2010. In those cases, we observe that there has always been an increase in governance.

This increase in governance indicators is always accompanied by either an increase in GERD or an

increase in tertiary education expenditures.

Table 4: Government Spending and Growth of Knowledge Economies

Country GERD Tertiary

Education

Expenditures

Governance High Tech

Exports

Patent

Filings

BERD

Estonia

+ + + + +

France

+ + + + +

Greece

+ + + + +

India

+ + + + +

Portugal

+ + + + + +

It appears that government spending on education, when coupled with either increased government

expenditures on R&D or increased Business expenditures in R&D, results in increased high tech

exports. The investment in human capital through spending on tertiary education, combined with

either private or public sector investment in R&D capacity, clearly has an efect on the improvement

of knowledge economy indicators such as high tech exports. This occurred in France, and in Portugal

until 2008, where we see a drop in high tech exports in that year. This drop may be attributed to the

global nancial crisis that began in 2008, which hit certain members of the European Union with

less established high tech industries such as Portugal and Spain.

Cr e a t i ng a n I nnova t i on Ec os ys t e m: Gove r na nc e a nd t he Gr owt h of Knowl e dge Ec onomi e s

P A R D E E C E N T E R R E S E A R C H R E P O R T | O C T O B E R 2 0 1 2 | P A G E 6

Figure 1: Education Expenditures and the Growth of Knowledge Economies

Cr e a t i ng a n I nnova t i on Ec os ys t e m: Gove r na nc e a nd t he Gr owt h of Knowl e dge Ec onomi e s

P A R D E E C E N T E R R E S E A R C H R E P O R T | O C T O B E R 2 0 1 2 | P A G E 7

Left axis:

GERD:

Government

Investment

in R&D

BERD:

Business

Expenditures

in R&D

Right axis:

Tertiary

Education

Expenditures,

in terms of

% GDP

High Tech

Exports, as

percentage

of overall

manufactured

exports

0%

2.7%

2010 2008 2006 2004 2002 2000 1998 1996

FRANCE

2010 2008 2006 2004 2002 2000 1998 1996

PORTUGAL

2010 2008 2006 2004 2002 2000 1998 1996

SLOVAKI A

0%

40%

When tertiary education expenditures were reduced along with government expenditures in R&D,

we observe a decrease in BERD. This occurred in Slovakia.

(

T

e

r

t

i

a

r

y

e

d

u

c

a

t

i

o

n

e

x

p

e

n

d

i

t

u

r

e

s

a

s

%

G

D

P

,

h

i

g

h

t

e

c

h

e

x

p

o

r

t

s

a

s

%

o

f

a

l

l

e

x

p

o

r

t

s

)

(

B

E

R

D

,

G

E

R

D

,

a

s

%

G

D

P

)

3.3 ENCOURAGING BUSINESS EXPENDITURES IN R&D THROUGH GOOD GOVERNANCE

We observe that improved governance and higher BERD from 1996 to 2006 occurs in Estonia,

Uganda and Mexico. This correlation occurring in three diferent continents with countries having

no connection each other gives strong support to our hypothesis that governance can improve

knowledge economies. Estonia has recently emerged from the Soviet rule, attaining its independence

in 1991. Mexico was under single party rule from 1929 to 1988. President Vicente Fox was the rst

elected President not to come from the institutional Revolutionary party since 1929. Uganda was

under dictatorship of Idi Amin until 1979, followed by single party rule until 2005. Although its

President, Yoweri Museveni, has been in power since 1986, improvements in Ugandas electoral

policies have resulted in higher evaluation of its voice and accountability in recent years. The only

commonality among these three states is their emergent democracies.

Figure 2: Positive Inuence of Governance on BERD

0.0

2010 2008 2006 2004 2002 2000 1998 1996 2010 2008 2006 2004 2002 2000 1998 1996

ESTONI A MEXI CO UGANDA

2010 2008 2006 2004 2002 2000 1998 1996

4.5%

-1.0

0.0

1.6

Cr e a t i ng a n I nnova t i on Ec os ys t e m: Gove r na nc e a nd t he Gr owt h of Knowl e dge Ec onomi e s

P A R D E E C E N T E R R E S E A R C H R E P O R T | O C T O B E R 2 0 1 2 | P A G E 8

Left axis:

GI 1:

Governance

Indicator

Voice and

Accountability,

scaled from

2.5 to 2.5

Right axis:

BERD:

Business

Expenditures

in R&D, in

terms of

% GDP

We observe a reduction in governance indicators and a reduction in BERD from 1996 to 2006 in the

following states: Russia, Singapore, South Africa, Poland (until 2003).

The same correlation discussed above occurred with the reduction of governance resulting in reduced

BERD in three diferent continents. The commonality among these states can also be found in their

recent transitions from authoritarian rule to electoral democracies. However, the commonality also

extends to the fact that in all of these states, this transition has been marred by reductions in political

(

G

I

1

)

(

B

E

R

D

)

and civil liberties. Russia seceded from the Soviet Union in 1992, but over the years has seen curtailing

of the democratic reforms rst introduced by Boris Yeltsin. Similarly, recent laws in Singapore have

further reduced the freedom of assembly through the Public Order Act of 2009 (Human Rights

Watch, 2010). Censorship of media outlets is also widespread in Singapore (Lee and Willnat, 2006).

Although South Africa doesnt have the same history of political repression in the last 20 years, its

large income disparities are often attributed to an absence of economic freedom and possibilities of

upward mobility. The number of people living in extreme poverty has risen 20.2 million in 1995 to 21.9

million in 2002. South Africa also has one of the most unequal distribution of incomes in the world:

60 percent of the population earns less than R42,000 per annum (about US$7,000), whereas 2.2

percent of the population earn more than R360,000 per annum (about US$50,000) (Leibbrandt

2010). Despite widespread calls to nationalize the natural resources of South Africa, the vast majority

of resources in the state are held by the private sector and the wealth generated thereof does not

provide signicant benets to most South Africans. (Motsoeneng, Lakmidas 2012). Poland was a

nascent democracy, having held its rst democratic elections in 1990. Its democratically-elected

government was marred by accusations of corruption throughout the 1990s (Wolsczak 2010).

This implies that if a government does not have the nancial resources to invest directly in an inno-

vation ecosystem, it can still create an environment conducive to private sector investment in R&D.

Figure 3: Negative Inuence of Governance on BERD

0.0

4.5% 1.6

2010 2008 2006 2004 2002 2000 1998 1996 2010 2008 2006 2004 2002 2000 1998 1996 2010 2008 2006 2004 2002 2000 1998 1996 2010 2008 2006 2004 2002 2000 1998 1996

-1.0

0.0

SOUTH AFRI CA POLAND SI NGAPORE RUSSI A

Cr e a t i ng a n I nnova t i on Ec os ys t e m: Gove r na nc e a nd t he Gr owt h of Knowl e dge Ec onomi e s

P A R D E E C E N T E R R E S E A R C H R E P O R T | O C T O B E R 2 0 1 2 | P A G E 9

Left axis: GI 1: Governance Indicator Voice and Accountability, scaled from 2.5 to 2.5

Right axis:

BERD: Business Expenditures in R&D, in terms of % GDP

(

G

I

1

)

(

B

E

R

D

)

3.4 ENCOURAGING INNOVATION THROUGH GOOD GOVERNANCE

We also observe that there are some cases where patent lings rise despite reductions in GERD and

BERD. This phenomenon was observed in Slovakia before 2003. Patent lings rise with the rise in

good governance. This may be due to an enhanced trust in the government and its legal institutions,

thereby encouraging inventors to le patents with their national patent ofce rather than seeking

intellectual property (IP) protection elsewhere through lings in regional IP organizations or directly

to World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) through the Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT).

Mistrust of government institutions may lead inventors to not le patents at all and instead protect

intellectual property through secrecy. We observe a similar phenomenon in Kenya, where despite an

absence of data on GERD and BERD, we can see an increase in patent lings along with an increase

in governance indicators. The sharpest increase in governance indicators in Kenya occurred between

2002 and 2004, when the National Rainbow Coalition came to power in the 2002 elections. In June

of 2003, the newly-elected government put in place an Economic Recovery Strategy whose mission

was to be achieved through sound governance structures that addresses the countrys vulnerabilities

(African Development Bank/OECD 2004).

Figure 4: Positive Inuence of Governance on Patent Filings

2010 2008 2006 2004 2002 2000 1998 1996

2010 2008 2006 2004 2002 2000 1998 1996

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

110

120

130

140

150

160

170

180

190

200

210

220

230

240

250

260

-1.0

0.0

1.6

1

9

5

2

1

3

2

3

6

2

5

9

2

1

5

1

9

3

1

6

7

2

3

4

1

5

2

7

2

6

2

4

3

9

5

4

6

7

8

1

SLOVAKI A KENYA

Cr e a t i ng a n I nnova t i on Ec os ys t e m: Gove r na nc e a nd t he Gr owt h of Knowl e dge Ec onomi e s

P A R D E E C E N T E R R E S E A R C H R E P O R T | O C T O B E R 2 0 1 2 | P A G E 1 0

Left axis:

GI 1:

Governance

Indicator

Voice and

Accountability,

scaled from

2.5 to 2.5

Right axis:

Annual Patent

Filings

(

G

I

1

)

(

A

n

n

u

a

l

P

a

t

e

n

t

F

i

l

i

n

g

s

)

0

65%

2010 2008 2006 2004 2002 2000 1998 1996

UGANDA

2010 2008 2006 2004 2002 2000 1998 1996

SLOVAKI A

-1.0

0.0

1.6

2010 2008 2006 2004 2002 2000 1998 1996

KENYA*

3.5 ENHANCING EXPORT OF HIGH TECH PRODUCTS THROUGH GOOD GOVERNANCE

We observe in several states a relationship between the rise in governance indicators and the rise

in percentage of exports being based on high tech manufacturing. Although a drop in governance

generally doesnt result in a drop in these exports, the initial increase is almost always correlated to

an increase in governance indicators. We indicated earlier in this paper that high tech exports are an

excellent indicator of the development of knowledge economies because they provide data on actual

commercialization and prots generated by the ability to create and use knowledge, whereas

patents simply indicate potential commercial opportunities through the demarcation of knowledge

that may be an asset.

Figure 5: Positive Inuence of Governance on High Tech Exports

Cr e a t i ng a n I nnova t i on Ec os ys t e m: Gove r na nc e a nd t he Gr owt h of Knowl e dge Ec onomi e s

P A R D E E C E N T E R R E S E A R C H R E P O R T | O C T O B E R 2 0 1 2 | P A G E 1 1

Left axis:

GI 1:

Governance

Indicator

Voice and

Accountability,

scaled from

2.5 to 2.5

Right axis:

GERD:

Government

Investment

in R&D

BERD:

Business

Expenditures

in R&D

High Tech

Exports, as

percentage

of overall

manufactured

exports

* BERD and GERD

data for Kenya

was unavailable.

(

B

E

R

D

,

G

E

R

D

,

a

s

%

G

D

P

a

n

d

h

i

g

h

t

e

c

h

e

x

p

o

r

t

s

a

s

%

o

f

a

l

l

e

x

p

o

r

t

s

)

(

G

I

1

)

Our analysis has shown that a rise in governance frequently occurs just before a sharp peak in the

percentage of exported high tech goods. This is particularly true in emerging markets as indicated

by two examples, namely Slovakia and Uganda. Slovakias increase in governance indicators were in

part due to the improvement of democratic institutions following the fall of the Iron Curtain. The fall

in its governance indicators from 2004 on may be in part due to reduced freedom of the press since

the elections in 2006, which were followed by government policies that reduced freedom of the

press and minority rights (Kneuer et al 2011).

In Uganda we observe a dramatic increase in the value of governance indicators from 2002 to

2006. Immediately at the end of this period of improvement in governance, we observe a peak in

high tech exports. In the period of 2002 to 2006, Ugandas government put tremendous eforts

into peace building and constitutional reform. From 2001 to 2005, the Ugandan government

implemented a Constitutional Review Process, which was concluded with the Constitutional

Amendment Act of 2005. This Act enabled increased political participation by the opposition

parties, limited terms of ofce for most executive positions in government. The Political Parties and

Organizations Act of 2005 further reformed democratic institutions and enabled improvements

in political expression and government accountability to citizens (Republic of Uganda Ministry

of Finance, 2010). We also observe a sharp increase in high tech exports from 2004 to 2006.

This observed growth is due to the increase in exports of electronic goods from Uganda starting

in 2006. The overlap in the period of democratic reform and growth of a knowledge economy in

Uganda serves as an excellent case in point to corroborate our central hypothesis on the correlation

between governance and economies based on technological innovation.

On the other hand, a reduction in the accountability of the government to its citizens appears

to correlate with a drop in high tech exports. We also note that a drop in high tech exports is

simultaneous with a drop in governance, despite BERD and GERD increasing during that period.

This is the case in Portugal, Singapore and South Africa.

In Portugal, we observe a decline of high tech exports from 4.3 percent to nearly 3 percent after a

growth of almost 9 percent over the time period of 1996 to 2010. This rise and then dramatic fall

is paralleled by the changes in governance indicators over the same period; during that time, the

Portuguese government heavily invested in R&D, as is clear by its GERD data, and its private sector

also focused most of its investments in R&D. Despite these eforts, the high tech exports rate fell

dramatically.

In Singapore, we observe a drop in high tech exports from 55 percent in 1996 to a drop to 49

percent in 2010, (which included a rise up to 62 percent in 1998 in the intervening time frame)

that is simultaneous with a drop both in BERD (from .33 to .29 percent GDP) and in governance

indicators ( from .266 to .299). This is despite a rise in GERD (from 1.33 percent GDP to 2.66

percent GDP and a dramatic rise in patent lings (from 224 patents to 895 patents) over the

period from 1996 to 2010. This implies that both BERD and high tech exports were afected by

the drop in governance.

In South Africa, we note a sharp drop in high tech exports from 1998 (8.75 percent) to 2002

(5.16 percent). This is despite an overall increase in GERD from .49 percent to .73 percent and

an increase in patent lings. BERD data for this period is not available. During that period, the

governance dropped more than .2 points, from .84 to .62.

Cr e a t i ng a n I nnova t i on Ec os ys t e m: Gove r na nc e a nd t he Gr owt h of Knowl e dge Ec onomi e s

P A R D E E C E N T E R R E S E A R C H R E P O R T | O C T O B E R 2 0 1 2 | P A G E 1 2

Cr e a t i ng a n I nnova t i on Ec os ys t e m: Gove r na nc e a nd t he Gr owt h of Knowl e dge Ec onomi e s

P A R D E E C E N T E R R E S E A R C H R E P O R T | O C T O B E R 2 0 1 2 | P A G E 1 3

Figure 6: Negative Inuence of Governance on High Tech Exports

2010 2008 2006 2004 2002 2000 1998 1996

-1.0

0.0

1.6

2010 2008 2006 2004 2002 2000 1998 1996 2010 2008 2006 2004 2002 2000 1998 1996

0%

65%

PORTUGAL SI NGAPORE SOUTH AFRI CA

Left axis:

GI 1:

Governance

Indicator

Voice and

Accountability,

scaled from

2.5 to 2.5

Right axis:

GERD:

Government

Investment

in R&D

BERD:

Business

Expenditures

in R&D

High Tech

Exports, as

percentage

of overall

manufactured

exports

(

B

E

R

D

,

G

E

R

D

,

a

s

%

G

D

P

a

n

d

h

i

g

h

t

e

c

h

e

x

p

o

r

t

s

a

s

%

o

f

a

l

l

e

x

p

o

r

t

s

)

(

G

I

1

)

Cr e a t i ng a n I nnova t i on Ec os ys t e m: Gove r na nc e a nd t he Gr owt h of Knowl e dge Ec onomi e s

P A R D E E C E N T E R R E S E A R C H R E P O R T | O C T O B E R 2 0 1 2 | P A G E 1 4

Section 4: Consideration of Confounding Variables

For emerging democracies in Eastern Europe seeking to join the European Union, we have excluded

the data after their EU accession referendum was passed. The incentive for improved governance

(EU membership) was removed and creates a discontinuity in tracking good governance. It also

removes the direct relationship between national governments and the strength of their knowledge

economies due to a more open relationship with established democracies. Specically, we applied

this rule to Estonia, Slovakia, Poland and Romania.

Section 5: Conclusions

Our primary aim in this work was to determine the ways in which governments can encourage

the growth of knowledge economies. We have successfully shown that even without increasing

government spending on R&D, the rate of innovation in a country can grow when the political

freedoms associated with voice and accountability are improved. We have shown this in

a quantitative manner, using indicators established and measured by leaders in economic

development such as the World Bank and the Organization for Economic Cooperation and

Development. The results of our analysis show the role that good governance (in the form of

political liberties) plays in determining the outcome of investments in a knowledge economy. The

results also show the means to boost the growth of a knowledge economy even for those states

with limited capacity for government investment in R&D.

This conclusion opens the door to a deeper exploration

of other ways good governance and investment in civil

society and social welfare can impact the growth of

knowledge economies.

The investment a government makes in its national

infrastructure, for example, can have dramatic efects

on capacity building. Telecommunications, clean

water, transportation and resource extraction are all

infrastructures that play a signicant role in the capacity of a country to develop a knowledge

economy. The cases of both the Indian and Kenyan government investing in its telecommunications

infrastructure and the resultant boom of the IT sector is an excellent case in point (Dahlman and

Utz 2005; The Economist 2012). A further case in point is the Danish governments investment

in resource extraction for the acquisition of oil, which it transformed into a domestic industry of

polymer fabrication (Danish Research Agency 2002). These examples demonstrate the merit of

a detailed investigation of the correlation between investments in infrastructure and the growth

of knowledge economies. The health care needs of a country can also inuence the development

of industry around high tech products. The dramatic rise in Ethiopias high tech manufacturing in

2004 (World Bank b) came from the governments role in increasing production as well as demand

for generic drugs to treat the AIDS pandemic (Tadesse 2004).

... governments investment in its

intellectual capital is paramount to

the growth of knowledge economies.

Cr e a t i ng a n I nnova t i on Ec os ys t e m: Gove r na nc e a nd t he Gr owt h of Knowl e dge Ec onomi e s

P A R D E E C E N T E R R E S E A R C H R E P O R T | O C T O B E R 2 0 1 2 | P A G E 1 5

The government also plays a signicant role in encouraging knowledge economies by having a legal

system that enables and encourages technology entrepreneurship. These incentive structures can

include tax cuts for technology startups, patent laws that reduce barriers to individual patent lers

both domestically and in foreign patent lings, and the facilitation of high tech exports through

trade agreements that support domestic industry. A more rigorous examination of these measures

would also shed further light on how governments can encourage the growth of knowledge

economies with little scal expenditure.

Perhaps most signicantly, the governments investment in its intellectual capital is paramount

to the growth of knowledge economies. In addition to tertiary education expenditures, which

have been examined in this report, funding for training of researchers beyond college as well as

facilitation of international collaborations and knowledge transfer may serve as factors to the

growth of knowledge economies.

The ability of a countrys brilliant minds to exercise and

implement their ideas in a way that enhances its national

wealth and welfare is based on the quality of governance

under which those brilliant minds can operate. A nation

with freedom of expression and assembly, where the

government is accountable to its citizens, fosters an

environment in which innovation can occur. It also creates

an environment where entrepreneurship and innovation

meet to create knowledge economies. The direct correlation

between increases in BERD and governance can be further

investigated by qualitative assessments and interviews of

business leaders and technology entrepreneurs in states

in democratic transitions. We are cognizant that many of these stakeholders will argue that the

increased trust in the government enables them to invest in long term projects such as STEM-

based research and development, as well as trust in the institutions meant to support technology

entrepreneurship, such as intellectual property protection and support of domestic industries in

foreign markets through trade agreements that enable exports of high tech goods. A government

that is accountable to its people can dynamically respond to the needs of technology entrepreneurs

in a way that totalitarian regimes cannot. Our results support this conclusion, and our hope is that

those nations striving to rise with the tide of economic growth based on knowledge will incorporate

better governance into their policies.

A nation with freedom of

expression and assembly, where

the government is accountable to

its citizens, fosters an environment

in which innovation can occur.

Cr e a t i ng a n I nnova t i on Ec os ys t e m: Gove r na nc e a nd t he Gr owt h of Knowl e dge Ec onomi e s

P A R D E E C E N T E R R E S E A R C H R E P O R T | O C T O B E R 2 0 1 2 | P A G E 1 6

References

African Development Bank, Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. 2004.

African Economic Outlook: Kenya. Available at:

http://www.oecd.org/dev/europemiddleeastandafrica/40578108.pdf

Cooke, Philip and Leydesdorf, Loet. 2006. Regional Development in the Knowledge-Based Economy:

The Construction of Advantage. The Journal of Technology Transfer 31(1): 5-15.

Dahlman, Carl and Utz, Anuja. 2005. India and the Knowledge Economy: Leveraging Strengths and

Opportunities. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Human Rights Watch. 2010. World Report Chapter: Singapore Country Summary, January. Available

at: http://www.hrw.org/sites/default/les/related_material/singapore_0.pdf

Julien, Pierre-Andre. 2007. A Theory of Local Entrepreneurship in the Knowledge Economy. London:

Edward Elgar Publishing.

Kaufmann, Daniel; Kraay, Aart and Mastruzzi, Massimo. 2010. The Worldwide Governance

Indicators: Methodology and Analytical Issues. World Bank Policy Research, Working Paper No. 5430.

Available at http://ssrn.com/abstract=1682130

Kneuer, Marianne; Malova, Darina; Bonker, Frank. 2011. Sustainable Governance Indicators 2011, Slovakia

Report. Gtersloh, Germany: Verlag Gertelsmann Stiftung. Available at:

http://www.sgi-network.org/pdf/SGI11_Slovakia.pdf

Lee, Terence and Willnat, Lars. 2006. Media Research and Political Communication in Singapore.

Murdoch, Western Australia: Asia Research Centre, Murdoch University.

Leibbrandt, Murray et al. 2010. Trends in South African Income Distribution and Poverty since the

Fall of Apartheid, OECD Social, Employment and MigrationWorking Papers, No. 101, OECD Publishing,

OECD. doi:10.1787/5kmms0t7p1ms-en

Mas, Nuria. 2009. Biotechnology in Catalonia: Industry Analysis. IESE Business School Working Paper

805. Available at SSRN: http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1482994

MIT Center for Real Estate Studies. New Century Cities: Case Studies Seoul Digital Media City.

http://web.mit.edu/cre/research/ncc/casestudies/seoul.html (Accessed September 14, 2012).

Motsoeneng, Tilseto and Lakmidas, Sheriliee. 2012. South Africas Zuma squashes mine

nationalization talk. Reuters, Johannesburg, February 10.

OECD. 2012. Main Science and Technology Indicators. OECD Science, Technology and R&D Statistics

http://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/science-and-technology/data/oecd-science-technology-and-r-d-

statistics/main-science-and-technology-indicators_data-00182-en (Accessed August 2012).

Perez-Aleman, Paola. 2005. CLUSTER formation, institutions and learning: the emergence of clusters

and development in Chile. Industrial and Corporate Change 14(4):651-677.

Republic of Uganda Ministry of Finance, Planning and Economic Development. 2010. Uganda National

Report For the Implementation of the Programme of Action for the Least Developed Countries for the

Decade 2001-2010. Submitted to the United Nations Ofce of the High Representative for the Least

Developed Countries and Small Island Developing States (UN-OHRLLS), January 2010.

Available at: http://www.un.org/wcm/webdav/site/ldc/shared/Uganda.pdf

Sbhatu, Desta Berhe. 2010. Ethiopia: Biotechnology for development. Journal of Commercial

Biotechnology 16(1).

Cr e a t i ng a n I nnova t i on Ec os ys t e m: Gove r na nc e a nd t he Gr owt h of Knowl e dge Ec onomi e s

P A R D E E C E N T E R R E S E A R C H R E P O R T | O C T O B E R 2 0 1 2 | P A G E 1 7

Sen, Amartya. 2000. Development as Freedom. New York: Anchor Books.

Tadesse, Tsegaye. 2004. Ethiopia: Aids-drug production started. Independent Online, September 17,

Africa section.

The Danish Research Agency, Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation. 2002. Evaluation of the

Danish Polymer Centre. Copenhagen: Danish Technical Research Council.

The Economist. 2012. Innovation in Africa: Upwardly mobile-Kenyas technology start-up scene is about

to take of. August 25.

UNESCO Institute for Statistics (a). Table 28: GERD by source of funds.

http://stats.uis.unesco.org/unesco/TableViewer/tableView.aspx?ReportId=2658

(Accessed August 2012 via http://www.uis.unesco.org/Pages/default.aspx).

UNESCO Institute for Statistics (b). Table 26: GERD as a percentage of GDP and GERD per capita.

http://stats.uis.unesco.org/unesco/TableViewer/tableView.aspx?ReportId=2656

(Accessed August 2012 via http://www.uis.unesco.org/Pages/default.aspx).

UNESCO Institute for Statistics (c). Table 5: Researchers by sector of employment (FTE and HC).

http://stats.uis.unesco.org/unesco/TableViewer/tableView.aspx?ReportId=2661

(Accessed August 2012 via http://www.uis.unesco.org/Pages/default.aspx).

Viginier, Pacal; Paillard, Sandrine; Lallement Remi; Har Mohamed; Mouhoud El Mouhoub; Sominin

Bernard. 2002. La France dans lconomie du savoir : pour une dynamique collective. Commissariat gnral

du plan, Paris, La Documentation franaise.

Volinets, Alexey. 2006. Case Study: Koreas Transition towards Knowledge Economy. Washington, D.C.:

World Bank.

WIPO. 2011. Patent applications by patent ofce and country of origin, 1995-2010. World Intellectual

Property Indicators, 2011 edition. Geneva: World Intellectual Property Organization.

http://www.wipo.int/ipstats/en/statistics/patents/

Wolszcak, Grzegorz. 2010. Civil Society Against Corruption: Poland European Research Centre for

Anti-Corruption and State-Building, September.

World Bank (a). Data table: High-technology exports (% of manufactured exports).

http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/TX.VAL.TECH.MF.ZS/countries (Accessed August 2012).

World Bank (b). Data table: Patent applications, residents.

http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/IP.PAT.RESD/countries (Accessed August 2012).

Zhihua Zeng, Douglas. 2008. Knowledge, Technology, and Cluster-Based Growth in Africa. Washington,

DC: World Bank.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to acknowledge the Pardee Center for its support of this work. We would also like to

acknowledge Tamar Hayrikyan of PODER, Ermias Biadgleng of the UN Commission on Trade and

Development, and William Guyster of MITs Legatum Center for their valuable input. We would also

like to thank our friends and colleagues who have served as sounding boards throughout the writing

of this report, in particular Rui Nunes, Andrea Fernandes, Darash Desai, and Grace Wu.

67 Bay State Road tel +1 617.358.4000 www.bu.edu/pardee

Boston MA 02215 fax +1 617.358.4001 @BUPardeeCenter

USA pardee@bu.edu

The Frederick S. Pardee Center

for the Study of the Longer-Range Future

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Azatuhi Ayrikyan is a Ph.D. candidate in Materials Science and Engineering at Boston University,

where she is developing technologies for global health in the Laboratory for Engineering Education

and Development. Ayrikyan also serves as a consultant on intellectual property to the World

Health Organization on local production of medical products in developing countries. She is

a commercialization analyst for Foresight Science and Technology, a pioneering technology

transfer consulting rm whose mission is to help bring early stage technologies to market. She

has extensive experience in technology development in emerging markets through her work as

an intellectual property consultant for technology startups in Armenia. Ayrikyan served as a

technology development analyst for Boston University, where she developed a program for global

dissemination of university inventions. In addition to her academic training, she has a long-standing

interest and involvement in human rights advocacy, having served as a national coordinator for

several campaigns run by Amnesty International USA.

Muhammad H. Zaman is Director of the Laboratory for Engineering Education and Development,

Associate Professor of Biomedical Engineering, and Innovative Engineering Education Faculty

Fellow at Boston University. He also holds appointments in the Department of Medicine and the

Department of International Health at Boston University School of Medicine, and is a Pardee Center

Faculty Fellow. Zaman currently serves as a technical member of the United Nations Economic

Commission for Africa (UNECA) and is a co-Director of the UNECA Biomedical Engineering

Initiative. Zaman is involved in developing robust and afordable diagnostic technologies for the

developing world and is working on capacity building and engineering education in these countries

as well. At BU, his research team develops robust, cheap, and terrain-ready medical devices and

diagnostics that have already begun to be implemented throughout sub-Saharan Africa.

ISBN 978-1-936727-07-0

Você também pode gostar

- SSRN Id3526909Documento38 páginasSSRN Id3526909Disyacitta CameliaAinda não há avaliações

- Econ 7030 PPTDocumento11 páginasEcon 7030 PPTMaryam KhanAinda não há avaliações

- Government Size and Economic Growth Evidence FromDocumento7 páginasGovernment Size and Economic Growth Evidence FromDecoy1 Decoy1Ainda não há avaliações

- Econ7030-Speach DraftDocumento2 páginasEcon7030-Speach DraftMaryam KhanAinda não há avaliações

- Article PDI September 2014Documento21 páginasArticle PDI September 2014Igor SemenenkoAinda não há avaliações

- Module 4-Economic DevelopmentDocumento3 páginasModule 4-Economic Developmentjessafesalazar100% (1)

- NIS BookDocumento186 páginasNIS BookRadhika PerrotAinda não há avaliações

- Assessing The Role of Public Spending For Sustainable Growth Empirical Evidence From NigeriaDocumento8 páginasAssessing The Role of Public Spending For Sustainable Growth Empirical Evidence From NigeriaAlexander DeckerAinda não há avaliações

- Science and Technology and Nation BuildingDocumento18 páginasScience and Technology and Nation BuildingResty Obina Jr.100% (1)

- KBE Strategy Final DocumentDocumento84 páginasKBE Strategy Final DocumentMaria MidiriAinda não há avaliações

- Mashup Indices of Development World Bank Research Paper No. 5432Documento5 páginasMashup Indices of Development World Bank Research Paper No. 5432fyswvx5bAinda não há avaliações

- Research Proposal: Impact of Historical Level of HDI On Contribution of R&D Expenditure Towards Labour ProductivityDocumento3 páginasResearch Proposal: Impact of Historical Level of HDI On Contribution of R&D Expenditure Towards Labour ProductivitysomeshAinda não há avaliações

- Vu Tien Dung - 20211699 - K3TCTA01 - Internship ReportDocumento24 páginasVu Tien Dung - 20211699 - K3TCTA01 - Internship ReportLan PhamAinda não há avaliações

- EditedDocumento7 páginasEditedWild WestAinda não há avaliações

- Paper GuíaDocumento18 páginasPaper GuíaRicardo AlvarezAinda não há avaliações

- 1.1 Introduction To The Subject: Role of Human Development and Governance in Economic Growth of A NationDocumento47 páginas1.1 Introduction To The Subject: Role of Human Development and Governance in Economic Growth of A NationsiddharthramanAinda não há avaliações

- Development EconomicsDocumento4 páginasDevelopment EconomicsSamita ChunaraAinda não há avaliações

- The Relationship Between Aid and FDI and Its Effect On Economic GrowthDocumento52 páginasThe Relationship Between Aid and FDI and Its Effect On Economic GrowthahmedAinda não há avaliações

- Innovation: Applying Knowledge in DevelopmentDocumento3 páginasInnovation: Applying Knowledge in DevelopmentdianatarrilloAinda não há avaliações

- PHD Thesis On Financial Development and Economic GrowthDocumento5 páginasPHD Thesis On Financial Development and Economic Growthvetepuwej1z3100% (1)

- Hdi ThesisDocumento7 páginasHdi Thesisgbvexter100% (2)

- KefelaDocumento7 páginasKefelashariqwaheedAinda não há avaliações

- Future of Government Smart Toolbox (World Economic Forum)Documento84 páginasFuture of Government Smart Toolbox (World Economic Forum)mahdi sanaeiAinda não há avaliações

- MPRA Paper 37293Documento10 páginasMPRA Paper 37293hasanmougharbelAinda não há avaliações

- Rethinking Investment Incentives: Trends and Policy OptionsNo EverandRethinking Investment Incentives: Trends and Policy OptionsAinda não há avaliações

- Public Governance Indicators: A Literature Review: Department of Economic and Social AffairsDocumento61 páginasPublic Governance Indicators: A Literature Review: Department of Economic and Social Affairshaa2009Ainda não há avaliações

- DF FD GrowthDocumento15 páginasDF FD GrowthMinh PhươngAinda não há avaliações

- International Trade PHD ThesisDocumento8 páginasInternational Trade PHD Thesisbrendatorresalbuquerque100% (1)

- SSRN Id402480 PDFDocumento39 páginasSSRN Id402480 PDFfariz amrilahAinda não há avaliações

- YN and ESSAY QUESTIONSDocumento18 páginasYN and ESSAY QUESTIONSLưu Tố UyênAinda não há avaliações

- U5 Case Study Difference in Development Between Different Countries NotesDocumento9 páginasU5 Case Study Difference in Development Between Different Countries Notessharmat1963Ainda não há avaliações

- Govt. Spending TanzaniaDocumento10 páginasGovt. Spending TanzaniaAhmed Ali HefnawyAinda não há avaliações

- Value Innovation & The Ethiopian EconomyDocumento22 páginasValue Innovation & The Ethiopian Economytadesse-w100% (1)

- Term Paper (Dev - Econ-2)Documento17 páginasTerm Paper (Dev - Econ-2)acharya.arpan08Ainda não há avaliações

- WEF HumanCapitalReport 2013Documento547 páginasWEF HumanCapitalReport 2013Eduardo CGAinda não há avaliações

- Reachers Paper11Documento11 páginasReachers Paper11Ambreen RabnawazAinda não há avaliações

- General Studies Class 12Documento6 páginasGeneral Studies Class 12rpcoolrahul73100% (1)

- UN E Government SurveyDocumento237 páginasUN E Government SurveyMujahed TaharwhAinda não há avaliações

- Impact of Remittances and FDI On Economic Growth: A Panel Data AnalysisDocumento20 páginasImpact of Remittances and FDI On Economic Growth: A Panel Data AnalysisBrendan LanzaAinda não há avaliações

- Infraestructura, Crecimiento Económico y Pobreza Una Revisión SSRN-id3612420Documento43 páginasInfraestructura, Crecimiento Económico y Pobreza Una Revisión SSRN-id3612420Steev Vega GutierrezAinda não há avaliações

- Econ 7030 ProposalDocumento12 páginasEcon 7030 ProposalMaryam KhanAinda não há avaliações

- Corruption and Transformation in a Developing EconomyNo EverandCorruption and Transformation in a Developing EconomyAinda não há avaliações

- Topic 2Documento6 páginasTopic 2Anna VytushynskaAinda não há avaliações

- Block 1 MEC 008 Unit 1Documento12 páginasBlock 1 MEC 008 Unit 1Adarsh Kumar GuptaAinda não há avaliações

- EconomicsDocumento5 páginasEconomicsPauline PauloAinda não há avaliações

- Chapter 1 Economic Growth and DevelopmentDocumento14 páginasChapter 1 Economic Growth and DevelopmentHyuna KimAinda não há avaliações

- International Business Assignment WongDocumento15 páginasInternational Business Assignment WongEleasa ZaharuddinAinda não há avaliações

- Globalization and Economic GrowthDocumento8 páginasGlobalization and Economic GrowthHiromi YukiAinda não há avaliações

- Determinants of Economic Growth in Ethiopia: Evidence From ARDL Approach AnalysisDocumento4 páginasDeterminants of Economic Growth in Ethiopia: Evidence From ARDL Approach Analysismisganawgetachew453Ainda não há avaliações

- Thesis Statement On Economic GrowthDocumento5 páginasThesis Statement On Economic Growthvictoriathompsonaustin100% (2)

- Human Welfare Development Theory GR12i 1Documento11 páginasHuman Welfare Development Theory GR12i 1shilmisahinAinda não há avaliações

- Capital and Collusion: The Political Logic of Global Economic DevelopmentNo EverandCapital and Collusion: The Political Logic of Global Economic DevelopmentAinda não há avaliações

- MPRA Paper 115220Documento34 páginasMPRA Paper 115220usmanshaukat311Ainda não há avaliações

- Impactofpopulationgrowth AprogressorregressDocumento7 páginasImpactofpopulationgrowth AprogressorregressLeo Federick M. AlmodalAinda não há avaliações

- The China Effect On Global Innovation: Research BulletinDocumento32 páginasThe China Effect On Global Innovation: Research BulletinRecep VatanseverAinda não há avaliações

- Me Assignment 1Documento33 páginasMe Assignment 1sreekanthAinda não há avaliações

- The Digital Divide and Its Impact On The Development of Mediterranean CountriesDocumento2 páginasThe Digital Divide and Its Impact On The Development of Mediterranean CountriesMARIA KARINA HURTADO ALOMIAAinda não há avaliações

- Mis Assignment: Concept Report On Business IntelligenceDocumento32 páginasMis Assignment: Concept Report On Business IntelligenceSoumya SahuAinda não há avaliações

- Cost Accounting MitticoolDocumento10 páginasCost Accounting MitticoolSoumya SahuAinda não há avaliações

- Acquisition 1Documento37 páginasAcquisition 1Soumya SahuAinda não há avaliações

- CommonwealthScholarships Prospectus 2015 JH Update 06.10.14Documento14 páginasCommonwealthScholarships Prospectus 2015 JH Update 06.10.14Soumya SahuAinda não há avaliações

- Dashman CompanyDocumento2 páginasDashman CompanySoumya SahuAinda não há avaliações

- Barton Enron CaseDocumento9 páginasBarton Enron CaseMohammad Delowar HossainAinda não há avaliações

- The Role of Business Incubators in DevelopingDocumento199 páginasThe Role of Business Incubators in DevelopingSoumya Sahu100% (2)

- Paul TrottDocumento13 páginasPaul TrottSoumya Sahu17% (6)

- Case Study of Ross Abernathy ANANYA AM1911Documento7 páginasCase Study of Ross Abernathy ANANYA AM1911Soumya SahuAinda não há avaliações

- 1 - Super Final Outline of China-2Documento14 páginas1 - Super Final Outline of China-2RichieNiiHansAinda não há avaliações

- 347-Article Text-704-1-10-20230619Documento13 páginas347-Article Text-704-1-10-20230619WISNU SUKMANEGARAAinda não há avaliações

- Global Business EnvironmentDocumento5 páginasGlobal Business EnvironmentLu XiyunAinda não há avaliações

- Ch27 Rural Transformation Berdegue Et Al 2013Documento44 páginasCh27 Rural Transformation Berdegue Et Al 2013Luis AngelesAinda não há avaliações

- A Project Report On Mutual Fund As An Investment Avenue at NJ India InvestDocumento16 páginasA Project Report On Mutual Fund As An Investment Avenue at NJ India InvestYogesh AroraAinda não há avaliações

- Boeing Current Market Outlook 2013Documento37 páginasBoeing Current Market Outlook 2013VaibhavAinda não há avaliações

- Vegi Sree Vijetha (1226113156)Documento6 páginasVegi Sree Vijetha (1226113156)Pradeep ChintadaAinda não há avaliações

- Project Report: Economic Growth in AsiaDocumento35 páginasProject Report: Economic Growth in AsiaVaibhav GuptaAinda não há avaliações

- Cement Industry in IndiaDocumento23 páginasCement Industry in IndiaPurnendu SinghAinda não há avaliações

- Unit 42 Planning For GrowthDocumento27 páginasUnit 42 Planning For GrowthPrajjwal Singh63% (8)

- Nigeria's Security Challenges and The Crisis of DevelopmentDocumento10 páginasNigeria's Security Challenges and The Crisis of DevelopmentAliyu Mukhtar Katsina, PhD100% (3)

- 4a CREATING AND STARTING THE VENTUREDocumento22 páginas4a CREATING AND STARTING THE VENTUREIsha SinghAinda não há avaliações

- Winning in Growth Cities: A Cushman & Wakefield Global Capital Markets ReportDocumento54 páginasWinning in Growth Cities: A Cushman & Wakefield Global Capital Markets ReportCheungWaiChungAinda não há avaliações

- EOS Annual Report 2018 2019 PDFDocumento224 páginasEOS Annual Report 2018 2019 PDFbrkinjoAinda não há avaliações

- Dependency TheoryDocumento8 páginasDependency TheorySkip GoldenheartAinda não há avaliações

- ST Andrews Investment Society: SM Prime Holdings, IncDocumento5 páginasST Andrews Investment Society: SM Prime Holdings, IncMary EdsylleAinda não há avaliações

- Fluctuations and Business Cycles in Indian Business EnvironmentDocumento13 páginasFluctuations and Business Cycles in Indian Business EnvironmentRonal MukherjeeAinda não há avaliações

- Egyptian NIS Engl-Web VersionDocumento180 páginasEgyptian NIS Engl-Web VersionMetalloyAinda não há avaliações

- World Population Growth - World Bank ReportDocumento6 páginasWorld Population Growth - World Bank ReportShaina SmallAinda não há avaliações

- Mexico Canada Two Nations in A North American Partnership CompressedDocumento248 páginasMexico Canada Two Nations in A North American Partnership CompressedYesica Yossary Gonzalez CanalesAinda não há avaliações

- The Imperialist World System - Paul Baran's Political Economy of Growth After Fifty Years by John Bellamy Foster - Monthly ReviewDocumento15 páginasThe Imperialist World System - Paul Baran's Political Economy of Growth After Fifty Years by John Bellamy Foster - Monthly ReviewStorrer guyAinda não há avaliações

- Status of Digital Agriculture in 47 Sub-Saharan African CountriesDocumento364 páginasStatus of Digital Agriculture in 47 Sub-Saharan African CountriesadaAinda não há avaliações

- Human GeographyDocumento29 páginasHuman GeographySheena Fe VecinaAinda não há avaliações

- 11 Economics Notes Ch15 Human Capital FormationDocumento7 páginas11 Economics Notes Ch15 Human Capital FormationAnonymous NSNpGa3T93Ainda não há avaliações

- Bba 6th Sem Dissertion ProjectDocumento54 páginasBba 6th Sem Dissertion ProjectSubhabrataMahapatra100% (3)

- Macroeconomics 9Th Edition Abel Solutions Manual Full Chapter PDFDocumento36 páginasMacroeconomics 9Th Edition Abel Solutions Manual Full Chapter PDFjames.coop639100% (12)

- Section 2: Influence of Access To Finance, Infrastructure, Market, Government Policy, Entrepreneurial Influence and Technology On The Growth of SmesDocumento7 páginasSection 2: Influence of Access To Finance, Infrastructure, Market, Government Policy, Entrepreneurial Influence and Technology On The Growth of SmesaleneAinda não há avaliações

- Jahanzeb ThesisDocumento31 páginasJahanzeb ThesisJahanzeb Khan Nizamani100% (1)

- Corporate Governance Practices in The Banking Sector: Ankit KatrodiaDocumento8 páginasCorporate Governance Practices in The Banking Sector: Ankit KatrodiaVikas VickyAinda não há avaliações

- Business Environment Chapter 5Documento5 páginasBusiness Environment Chapter 5Muneeb SadaAinda não há avaliações