Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Gad

Enviado por

lazylawstudentDireitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Gad

Enviado por

lazylawstudentDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

[G.R. No. 147080. April 26, 2005]CAPITOL MEDICAL CENTER, INC.

,

petitioner, vs

. NATIONAL LABOR RELATIONS COMMISSION, JAIME IBABAO, JOSE

BALLESTEROS, RONALDCENTENO, NARCISO SARMIENTO, EDUARDO

CANAVERAL, SHERLITO DELA CRUZ, SOFRONIO COMANDAO, MARIANO

GALICIA, RAMONMOLOD, CARMENCITA SARMIENTO, HELEN MOLOD,

ROSA COMANDAO, ANGELITO CUIZON, ALEX MARASIGAN, JESUS CEDRO,

ENRICOROQUE, JAY PERILLA, HELEN MENDOZA, MARY GLADYS

GEMPEROSO, NINI BAUTISTA, ELENA MACARUBBO, MUSTIOLA

SALVACIONDAPITO, ALEXANDER MANABE, MICHAEL EUSTAQUIO, ROSE

AZARES, FERNANDO MANZANO, HENRY VERA CRUZ, CHITO

MENDOZA,FREDELITA TOMAYAO, ISABEL BRUCAL, MAHALKO LAYACAN,

RAINIER MANACSA, KAREN VILLARENTE, FRANCES ACACIO,

LAMBERTOCONTI, LORENA BEACH, JUDILAH RAVALO, DEBORAH NAVE,

MARILEN CABALQUINTO, EMILIANA RIVERA, MA. ROSARIO

URBANO,ROWENA ARILLA, CAPITOL MEDICAL CENTER EMPLOYEES

ASSOCIATION-AFW, GREGORIO DEL PRADO, ARIEL ARAJA, and JESUS

STA.BARBARA, JR.,

FACTS: The Union filed a Notice of Strike with the (NCMB), The Union alleged as

grounds for the projected strike the following acts of the petitioner: (a) refusal

tobargain; (b) coercion on employees; and (c) interference/ restraint to self-

organization.

A series of conferences was conducted before the NCMB but no agreement was

reached. the petitioner even filed a Letter with the Board requesting that thenotice of

strike be dismissed;

the Union had apparently failed to furnish the Regional Branch of the NCMB with a

copy of a notice of the meeting where the strikevote was conducted.On November 20,

1997, the Union submitted to the NCMB the minutes of the alleged strike vote

purportedly held on November 10, 1997 at the parking lot infront of the peti

tioners premises.

It appears that 178 out of the 300 union members participated therein, and the results

were as follows: 156 members voted to strike;14 members cast negative votes; and eight

votes were spoiled.

On November 28, 1997, the officers and members of the Union staged a

strike. Subsequently, the Union filed An ex parte motion with the DOLE, praying for its

assumption of jurisdiction over the dispute. The SOLE assumed jurisdiction over the

labor disputes, Consequently, all striking workers are directed to return towork within

twenty-four (24) hours from the receipt of this Order and the management to resume

normal operations and accept back all striking workers under thesame terms and

conditions prevailing before the strike.In obedience to the order of the SOLE, the

officers and members of the Union stopped their strike and returned to work.The

Regional Director of the DOLE rendered a Decision denying the petition for the

cancellation of the respondent

Unions certift

cate of registration. In aparallel development, Labor Arbiter Leda rendered a Decision

in favor of the petitioner, and declared the strike staged by the respondents illegal.The

Labor Arbiter ruled that no voting had taken place on November 10, 1997; moreover,

no notice of such voting was furnished to the NCMB at least twenty-four (24) hours

prior to the intended holding of the strike vote.

According to the Labor Arbiter, the affidavits of the petitioners 17 employees who

alleged that

no strikevote was taken, and supported by the affidavit of the overseer of the parking

lot and the security guards, must prevail as against the minutes of the strike

votepresented by the respondents. The Labor Arbiter also held that in light of Article

263(9) of the Labor Code, the respondent Union should have filed a motion for a writof

execution of the resolution of Undersecretary Laguesma which was affirmed by this

Court instead of staging a strike.The respondents appealed the decision to the NLRC

which granted their appeal and reversing the decision of the Labor Arbiter. The NLRC

also denied the

petitioners petition to declare the strike illegal.

In resolving the issue of whether the union members held a strike vote on November

10, 1997, the NLRC ruled asfollows:

We find untenable the Labor Arbiters finding that no actual strike voting took place on

November 10, 1997, claiming that thi

s is supported by the affidavit of Erwin Barbacena, the overseer of the parking lot across

the hospital, and the sworn statements of nineteen (19) (

sic

) union members. While it is true that no strikevoting took place in the parking lot

which he is overseeing, it does not mean that no strike voting ever took place at all

because the same was conducted in theparking lot immediately/directly fronting, not

across, the hospital building. Further, it is apparent that the nineteen (19) (

sic

) hospital employees, who recanted their participation in the strike voting, did

so involuntarily for fear of loss of employment, considering that their Affidavits are

uniform and

pro forma

.The NLRC ruled that under Section 7, Rule XXII of DOLE Order No. 9, Series of 1997,

absent a showing that the NCMB decided to supervise the conduct of asecret balloting

and informed the union of the said decision, or that any such request was made by any

of the parties who would be affected by the secret ballotingand to which the NCMB

agreed, the respondents were not mandated to furnish the NCMB with such notice

before the strike vote was conducted.ISSUE: WHETHER RESPONDENTS COMPLIED

WITH THE LEGAL REQUIREMENTS FOR STAGING THE SUBJECT

STRIKE.HELD: No. We agree with the petitioner that the respondent Union failed to

comply with the second paragraph of Section 10, Rule XXII of the Omnibus Rules of

theNLRC which reads:Section 10. Strike or lockout vote.

A decision to declare a strike must be approved by a majority of the total union

membership in the bargaining unit concernedobtained by secret ballot in meetings or

referenda called for the purpose. A decision to declare a lockout must be approved by

a majority of the Board of Directors of the employer, corporation or association or the

partners obtained by a secret ballot in a meeting called for the purpose.The regional

branch of the Board may, at its own initiative or upon the request of any affected party,

supervise the conduct of the secret balloting. In every case, theunion or the employer

shall furnish the regional branch of the Board and notice of meetings referred to in the

preceding paragraph at least twenty-four (24) hoursbefore such meetings as well as the

results of the voting at least seven (7) days before the intended strike or lockout, subject

to the cooling-off period provided in thisRule. Although the second paragraph of

Section 10 of the said Rule is not provided in the Labor Code of the Philippines,

nevertheless, the same was incorporated inthe Omnibus Rules Implementing the Labor

Code and has the force and effect of law.

Aside from the mandatory notices embedded in Article 263, paragraphs (c) and (f) of

the Labor Code, a union intending to stage a strike is mandated to notifythe NCMB of

the meeting for the conduct of strike vote, at least twenty-four (24) hours prior to such

meeting. Unless the NCMB is notified of the date, place and timeof the meeting of the

union members for the conduct of a strike vote, the NCMB would be unable to

supervise the holding of the same, if and when it decides toexercise its power of

supervision. In

National Federation of Labor v. NLRC

,

[25]

the Court enumerated the notices required by Article 263 of the Labor Code and

theImplementing Rules, which include the 24-hour prior notice to the NCMB:1) A

notice of strike, with the required contents, should be filed with the DOLE, specifically

the Regional Branch of the NCMB, copy furnished the employer of theunion;2) A

cooling-off period must be observed between the filing of notice and the actual

execution of the strike thirty (30) days in case of bargaining deadlock andfifteen (15)

days in case of unfair labor practice.

However, in the case of union busting where the unions existence is threatened, the

cooling

-off period need not beobserved.

4)

Before a strike is actually commenced, a strike vote should be taken by secret balloting,

with a 24-hour prior notice to NCMB

. The decision to declare a strikerequires the secret-ballot approval of majority of the

total union membership in the bargaining unit concerned.

STAMFORD MARKETING CORP., ET AL. VS. JOSEPHINE JULIAN, ET AL.

G.R. No. 145496. February 24, 2004

Facts: On November 2, 1994, Zoilo de la Cruz, president of the Philippine Agricultural

Commercial and Industrial Workers Union (PACIWU-TUCP), sent a letter to Rosario

Apacible, treasurer and general manager of Stamford Marketing Corporation, GSP

Manufacturing Corporation, Giorgio Antonio Marketing Corporation, Clementine

Marketing Corporation and Ultimate Concept Phils., Inc. The letter informed her that

the rank-and-file employees of the said companies had formed the Apacible Enterprises

Employees Union-PACIWU-TUCP and demanded that it be recognized. After such

notice, the following three cases arose:

In the First Case, Josephine Julian, president of PACIWU-TUCP, Jacinta Tejada and

Jecina Burabod, a Board Member and a member of the said union, were dismissed.

They filed a suit with the Labor Arbiter alleging that their employer had not paid them

with their overtime pay, holiday pay/premiums, rest day premium, 13th month pay for

the year 1994 salaries for services actually rendered, and that illegal deduction had been

made without their consent from their salaries for a cash bond. Stamford alleged that

the three were dismissed for not reporting for work when required to do so and for not

giving notice or explanation when asked.

In the Second Case, PACIWU-TUCP filed, on behalf of 50 employees allegedly

dismissed illegally for union membership by the petitioners, a case for unfair labor

practice against GSP which denied such averments. GSP countered that the BLR did not

list Apacible Enterprises Employees Union as a local chapter of PACIWU or TUCP.

Thus, the strike that said union organized after the GSP refused to negotiate with them

was illegal and that they refused to return to work when asked.

The Third Case was filed for claims of the 50 employees dismissed in the second case.

Petitioner corporations, however, maintained that they have been paying complainants

the wages/salaries mandated by law and that the complaint should be dismissed in

view of the execution of quitclaims and waivers by the private respondents.

The Labor Arbiter ordered the three cases consolidated as the issues were interrelated

and the respondent corporations were under one management.

First Case: The dismissal was illegal and Stamford was ordered to reinstate the

complainants as well as pay the backwages and other benefits claimed. It was held that

the reassignment and transfer of the complainants were forms of interference in the

formation and membership of a union, an unfair labor practice. Stamford also failed to

substantiate their claim that the said employees abandoned their employment. It also

failed to prove the necessity of the cash deposit of P2,000 and failed to furnish written

notice of dismissal to any complainants. Further, it failed to prove payments of the

amounts being claimed.

Second Case: The strike was illegal and the officers of the union have lost their

employment status, thus terminating their employment with GSP. GSP is however

ordered to reinstate the complainants who were members of the union without

backwages, save some employees specified. It was established that the union was not

registered, and thus had staged an illegal strike. The officers of the union should be

liable and dismissed, but the members should not, as they acted in good faith in the

belief that their actions were within legal bounds.

Third Case: GSP was ordered to pay each complainant their claims, as computed by

each individual. All other claims were dismissed for lack of merit. The Labor Arbiter

found petitioners liable for salary differentials and other monetary claims for

petitioners failure to sufficiently prove that it had paid the same to complainants as

required by law. It was also ordered to return the cash deposits of the complainants,

citing the same reasons as in the First Case.

On appeal, the NLRC affirmed the decision in the First and Third Cases, but set aside

the judgment of the Second Case for further proceedings in view of the factual issues

involved.

On May 14, 1996, a Petition to Declare the Strike Illegal was filed which was decided in

favor of Stamford, upholding the dismissal of the union officers. The officers made no

prior notice to strike, no vote was taken among union members, and the issue involved

was non-strikable, a demand for salary increases

On elevation to the appellate court, it was ruled that the officers should be given

separation pay, and that Jacina Burabod and the rest of the members should be

reinstated without loss of seniority, plus backwages. It provided for the payment of the

backwages despite the illegality of the strike because the dismissals were done prior to

the strike. Such is considered an unfair labor practice as there was lack of due process

and valid cause. Thus, the dismissed employees were still entitled to backwages and

reinstatement, with exception to the union officers who may be given separation pay

due to strained relations with their employers.

Issues: (1) Whether or not the respondents union officers and members were validly

and legally dismisses from employment considering the illegality of the strike.

(2) Whether or not the respondents union officers were entitled to backwages,

separation pay and reinstatement, respectively.

Held: (1) The termination of the union officers was legal under Article 264 of the Labor

Code as the strike conducted was illegal and that illegal acts attended the mass action.

Holding a strike is a right that could be availed of by a legitimate labor organization,

which the union is not. Also, the mandatory requirements of following the procedures

in conducting a strike under paragraph (c) and (f) of Article 263 were not followed by

the union officers.

Article 264 provides for the consequences of an illegal strike, as well as the distinction

between officers and members who participated therein. Knowingly participating in an

illegal strike is a sufficient ground to terminate the employment of a union officer but

mere participation is not sufficient ground for termination of union members. Thus,

absent clear and substantial proof, rank-and-file union members may not be terminated.

If he is terminated, he is entitled to reinstatement.

The Court affirmed the ruling of the CA on the illegal dismissal of the union members,

as there was non-observance of due process requirements and union busting by

management. It also affirmed that the charge of abandonment against Julian and Tejada

were without credence. It reversed the ruling that the dismissal was unfair labor

practice as there was nothing on record to show that Julian and Tejada were

discouraged from joining any union. The dismissal of the union officers for

participation in an illegal strike was upheld. However, union officers also must be given

the required notices for terminating employment, and Article 264 of the Labor Code

does not authorize immediate dismissal of union officers participating in an illegal

strike. No such requisite notices were given to the union officers.

The Court upheld the appellate courts ruling that the union members, for having

participated in the strike in good faith and in believing that their actions were within

the bound of the law meant only to secure economic benefits for themselves, were

illegally dismissed hence entitled to reinstatement and backwages.

(2) The Supreme Court declared the dismissal of the union officers as valid hence, the

award of separation pay was deleted. However, as sanction for non-compliance with

the notice requirements for a lawful termination, backwages were awarded to the union

officers computed from the time they were dismissed until the final entry of the

judgment.

ST. SCHOLASTICAS COLLEGE VS. TORRES

210 SCRA 565GR. NO 100158 JUNE 29, 1992

FACTS:

The Union and College initiated negotiations fora first ever

CBA which resulted in a deadlockand prompted the union to file a notice of strikewith

the DOLE.

Union declared a strike which paralyzed theoperations of the College and public

respondentSec. of Labor immediately assumed jurisdictionover the labor dispute.

Instead of returning to work, the union filed amotion for reconsideration of the return

towork order.

The college sent individual letters to the strikingemployees requiring them to return to

work. Inresponse union presented demands, the mostimportant of which is the

unconditionalacceptance back to work of the strikingemployees. But these were

rejected.

Sec. of Labor denied the motion forreconsideration for his return to work order

andsternly warned striking employees to complywith its terms.

Conciliation meetings were held but this provedfutile as the college remained steadfast

in itsposition that any return to work order shouldbe unconditional.

The College manifested to respondent Sec. thatthe union continued to defy his return to

workorder.

The College sent termination letters toindividual strikers and filed a complaint forillegal

strike against the union.

nforcement of thereturn to work order before the Sec.

The Sec. issued an order directingreinstatement of striking union members andholding

union officers responsible for theviolation of the return to work order and

werecorrespondingly terminated.

Both parties moved for the partial considerationof the return to work order.

Hence tis petition.

ISSUE:

WON striking union members, terminated forabandonment of work after failing to

comply with thereturn to work order of Sec. of labor, reinstated.

HELD:

The Labor Code provides that if a strike hasalready taken place at the time of

assumption, allstriking employees should immediately return to work.This means that

a return to work order is immediatelyeffective and executory, notwithstanding the

filing of amotion for reconsideration. It must be strictly compliedwith even during the

pendency of any petitionquestioning its validity. After all, the assumption

and/orcertification order issue

d in the exercise of the Sec.s

compulsive power of arbitration and until set aside,must therefore be complied with

immediately.The college correspondingly had every right toterminate the services of

those who chose to disregardthe return to work order issued by the Sec. of Labor

inorder to protect the interest of the students who formpart of the youth of the land.

MSF Tire and Rubber vs CA

GR 128632

Facts:

Respondent Union filed a notice of strike in the NCMB charging (Phildtread) with

unfair labor

practice. Thereafter, they picketed and assembled outside the gate of Philtreads plant.

Philtread,

on the other hand, filed a notice of lockout. Subsequently, the Secretary of Labor

assumed

jurisdiction over the labor dispute and certified it for compulsory arbitration.

During the pendency of the labor dispute, Philtread entered into a Memorandum of

Agreement

with Siam Tyre whereby its plant and equipment would be sold to a new company,

herein

petitioner, 80% of which would be owned by Siam Tyre and 20% by Philtread, while the

land on

which the plant was located would be sold to another company, 60% of which would be

owned

by Philtread and 40% by Siam Tyre.

Petitioner then asked respondent Union to desist from picketing outside its plant. As

the

respondent Union refused petitioners request, petitioner filed a complaint for

injunction with

damages before the RTC. Respondent Union moved to dismiss the complaint alleging

lack of

jurisdiction on the part of the trial court.

Petitioner asserts that its status as an innocent bystander with respect to the labor

dispute

between Philtread and the Union entitles it to a writ of injunction from the civil courts.

Issue: WON petitioner has shown a clear legal right to the issuance of a writ of

injunction under

the innocent bystander rule.

Held:

In Philippine Association of Free Labor Unions (PAFLU) v. Cloribel, this Court, through

Justice

J.B.L. Reyes, stated the innocent bystander rule as follows:

The right to picket as a means of communicating the facts of a labor dispute is

a phase of the freedom of speech guaranteed by the constitution. If peacefully

carried out, it cannot be curtailed even in the absence of employer-employee

relationship.

The right is, however, not an absolute one. While peaceful picketing is entitled to

protection as

an exercise of free speech, we believe the courts are not without power to confine or

localize the

sphere of communication or the demonstration to the parties to the labor dispute,

including those

with related interest, and to insulate establishments or persons with no industrial

connection or

having interest totally foreign to the context of the dispute. Thus the right may be

regulated at

the instance of third parties or innocent bystanders if it appears that the inevitable

result of its

exercise is to create an impression that a labor dispute with which they have no

connection or

interest exists between them and the picketing union or constitute an invasion of their

rights.

Thus, an innocent bystander, who seeks to enjoin a labor strike, must satisfy the court

it is

entirely different from, without any connection whatsoever to, either party to the

dispute and,

therefore, its interests are totally foreign to the context thereof.

In the case at bar, petitioner cannot be said not to have such connection to the dispute.

We find that the negotiation, contract of sale, and the post transaction between

Philtread, as vendor, and Siam Tyre, as vendee, reveals a legal relation between them

which, in the interestof petitioner, we cannot ignore. To be sure, the transaction

between Philtread and Siam Tyre,

was not a simple sale whereby Philtread ceased to have any proprietary rights over its

sold

assets. On the contrary, Philtread remains as 20% owner of private respondent and 60%

owner

of Sucat Land Corporation which was likewise incorporated in accordance with the

terms of the

Memorandum of Agreement with Siam Tyre, and which now owns the land were

subject plant

is located. This, together with the fact that private respondent uses the same plant or

factory;

similar or substantially the same working conditions; same machinery, tools, and

equipment; and

manufacture the same products as Philtread, lead us to safely conclude that private

respondents

personality is so closely linked to Philtread as to bar its entitlement to an injunctive writ.

Petition denied.

from Atty. Alba^^

Labor Law Reviewer Part IV (p.79 of 309)

In PLDT vs. NLRC and Abucay, [164 SCRA 671], it was declared that while it would be

compassionate to give separation pay to a salesman if he were dismissed for his

inability to fill his quota, surely, however, he does not deserve such generosity if his

offense is the misappropriation of the receipts of his sales.

In Gustilo vs. Wyeth Phils., Inc., [G. R. No. 149629, October 4, 2004], the Court of

Appeals, despite its finding that the dismissal was legal, still awarded the complainant

separation pay of P106,890.00 allegedly by reason of several mitigating factors

mentioned in its assailed Decision. The Supreme Court, however, reversed said award

based on the afore-mentioned case of PLDT. It ruled that an employee who was legally

dismissed from employment is not entitled to an award of separation pay. Despite this

holding, however, the Supreme Court was constrained not to disturb the award of

separation pay in this case because respondent company did not interpose an appeal

from said award. Hence, no affirmative relief can be extended to it. A party in a case

who did not appeal is not entitled to any affirmative relief. chanrobles virtual law

library

The San Miguel test.

In line with the 2002 case of San Miguel [supra], it is now a matter of established rule

that the question of whether separation pay should be awarded depends on the cause of

the dismissal and the circumstances of each case.

National Federation of Labor vs. National Labor Relations Commission

G.R. No. 127718 (March 2, 2000)

Facts:

Petitioners are employees of the Patalon Coconut Estate in Zamboanga. With the advent

of the RA No. 6657 or the Comprehensive Agrarian Reform Law, the government

sought the compulsory acquisition of the land for agrarian reform. Because of this, the

private respondents who are owners of the estate decided to shut down its operation.

Petitioners did not receive any separation pay. Now, the petitioners pray, with the

representation of their labor group, claiming that they were illegally dismissed. They

cite Article 283 of the Labor code where an employer may terminate the employment

of any employee due to the installation of labor saving devices, redundancy,

retrenchment to prevent losses or the closing or cessation of operation.

Issue:

Whether or not the Court should apply the legal maxim verbal legis in construing

Article 283 of the Labor Code as regards its applicability to the case at bar.

Held:

Yes, the legal maxim is applicable in this case. The use of the word may, in its plain

meaning, denotes that it is directory in nature and generally permissive only. Also,

Article 283 of the Labor Code does not contemplate a situation where the closure of the

business establishment is forced upon the employer and ultimately for the benefit of the

employees. The Patalon Coconut Estate was closed down because a large portion of the

said estate was acquired by the DAR pursuant to the CARP. The severance of employer-

employee relationship between the parties came about involuntarily, as a result of an

act of the State. Consequently, complainants are not entitled to any separation pay.

Reasoning:

Where the words of a statute are clear, plain and free from ambiguity, it must be given

its literal meaning and applied without attempted interpretation.

Policy:

Article 283 of the Labor Code applies in cases of closures of establishment and

reduction of personnel. The peculiar circumstances in the case at bar, however, involves

neither the closure of an establishment nor a reduction of personnel as contemplated

under the article.

Você também pode gostar

- BDO PersonalLoanAKAppliFormDocumento4 páginasBDO PersonalLoanAKAppliFormAirMan ManiagoAinda não há avaliações

- T-FORCE BLITZ ManualDocumento12 páginasT-FORCE BLITZ ManuallazylawstudentAinda não há avaliações

- Decentralization in The PhilippinesDocumento27 páginasDecentralization in The Philippineslazylawstudent75% (4)

- Fy 2011 LBP Form No. 3 - SBDocumento2 páginasFy 2011 LBP Form No. 3 - SBlazylawstudentAinda não há avaliações

- Fy 2011 LBP Form No. 3 - MeoDocumento2 páginasFy 2011 LBP Form No. 3 - MeolazylawstudentAinda não há avaliações

- Crimes Committed by Public Officers (Book II, Title VII, Revised Penal Code) Anti-Graft and Corrupt Practices ActDocumento34 páginasCrimes Committed by Public Officers (Book II, Title VII, Revised Penal Code) Anti-Graft and Corrupt Practices ActlazylawstudentAinda não há avaliações

- Fy 2011 LBP Form No. 3 - Public MarketDocumento3 páginasFy 2011 LBP Form No. 3 - Public MarketlazylawstudentAinda não há avaliações

- Fy 2011 LBP Form No. 3 - MSWDDocumento5 páginasFy 2011 LBP Form No. 3 - MSWDlazylawstudentAinda não há avaliações

- "I Told Myself I Can Pass Any Test A Man Can Pass.": - Jake SullyDocumento2 páginas"I Told Myself I Can Pass Any Test A Man Can Pass.": - Jake SullylazylawstudentAinda não há avaliações

- Fy 2011 LBP Form No. 3 - MSWDDocumento5 páginasFy 2011 LBP Form No. 3 - MSWDlazylawstudentAinda não há avaliações

- YAS Digests LatestDocumento83 páginasYAS Digests LatestDann NixAinda não há avaliações

- Public INternational LawDocumento18 páginasPublic INternational Lawlazylawstudent100% (1)

- AlmanDocumento3 páginasAlmanlazylawstudentAinda não há avaliações

- Fy 2011 LBP Form No. 3 - NoeDocumento2 páginasFy 2011 LBP Form No. 3 - NoelazylawstudentAinda não há avaliações

- 2006 METROBANK-MTAP-DepED MATH CHALLENGE SOLUTIONS (LESS THAN 40 CHARACTERSDocumento6 páginas2006 METROBANK-MTAP-DepED MATH CHALLENGE SOLUTIONS (LESS THAN 40 CHARACTERSlazylawstudentAinda não há avaliações

- Antonio S. Samson S.JDocumento1 páginaAntonio S. Samson S.JlazylawstudentAinda não há avaliações

- Alman 5Documento3 páginasAlman 5lazylawstudentAinda não há avaliações

- PIL ReportDocumento14 páginasPIL ReportlazylawstudentAinda não há avaliações

- Agrarian Reform CasesDocumento9 páginasAgrarian Reform CasesMancelottiJarloAinda não há avaliações

- New Code of Judicial ConductDocumento7 páginasNew Code of Judicial ConductYohanna J K GarcesAinda não há avaliações

- Assignments For AttachmentsDocumento2 páginasAssignments For AttachmentslazylawstudentAinda não há avaliações

- Fy 2011 Besf Form No. 1Documento12 páginasFy 2011 Besf Form No. 1lazylawstudentAinda não há avaliações

- Jurisdiction Brownwell v. Sun Life Assurance Company: P. Settlement of DisputesDocumento3 páginasJurisdiction Brownwell v. Sun Life Assurance Company: P. Settlement of DisputeslazylawstudentAinda não há avaliações

- Norman Gabin L. Namla Ab-Is 2: A.) Internal WatersDocumento2 páginasNorman Gabin L. Namla Ab-Is 2: A.) Internal WaterslazylawstudentAinda não há avaliações

- Norman Gabin L. Namla Ab-Is 2: A.) Internal WatersDocumento2 páginasNorman Gabin L. Namla Ab-Is 2: A.) Internal WaterslazylawstudentAinda não há avaliações

- Assignments For AttachmentsDocumento2 páginasAssignments For AttachmentslazylawstudentAinda não há avaliações

- Tax CasesDocumento15 páginasTax CaseslazylawstudentAinda não há avaliações

- Succession NotesDocumento1 páginaSuccession NoteslazylawstudentAinda não há avaliações

- MSA Letter To CMDocumento1 páginaMSA Letter To CMlazylawstudentAinda não há avaliações

- Code of Commerce of The PhilippinesDocumento6 páginasCode of Commerce of The PhilippinesYosef_dAinda não há avaliações

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (399)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (344)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (266)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (120)

- Export Promotion Capital Goods Scheme PresentationDocumento32 páginasExport Promotion Capital Goods Scheme PresentationDakshata SawantAinda não há avaliações

- SGLGB ImplementationDocumento47 páginasSGLGB ImplementationDILG Maragondon CaviteAinda não há avaliações

- Topic 2Documento9 páginasTopic 2swathi thotaAinda não há avaliações

- COST - State-Of-The-Art Review On Design, Testing, Analysis and Applications of Polymeric Composite ConnectionsDocumento122 páginasCOST - State-Of-The-Art Review On Design, Testing, Analysis and Applications of Polymeric Composite ConnectionsDavid MartinsAinda não há avaliações

- QZ Brand GuideDocumento8 páginasQZ Brand GuideahmaliicAinda não há avaliações

- Automation Studio User ManualDocumento152 páginasAutomation Studio User ManualS Rao Cheepuri100% (1)

- Supply Chain Analysis of PRAN GroupDocumento34 páginasSupply Chain Analysis of PRAN GroupAtiqEyashirKanakAinda não há avaliações

- How To Remove Letters From Stringsnumberscells in ExcelDocumento1 páginaHow To Remove Letters From Stringsnumberscells in ExcelharshilAinda não há avaliações

- Hotel Room Booking System Use-Case DiagramDocumento5 páginasHotel Room Booking System Use-Case DiagramCalzita Jeffrey0% (1)

- Harty Vs Municipality of VictoriaDocumento1 páginaHarty Vs Municipality of VictoriaArah Mae BonillaAinda não há avaliações

- German Truck CheatDocumento3 páginasGerman Truck Cheatdukagold11Ainda não há avaliações

- Local and Global TechnopreneursDocumento25 páginasLocal and Global TechnopreneursClaire FloresAinda não há avaliações

- RwservletDocumento3 páginasRwservletNick ReismanAinda não há avaliações

- Mining Gate2021Documento7 páginasMining Gate2021level threeAinda não há avaliações

- When To Replace Your Ropes: Asme B30.30 Ropes For Details On The Requirements For Inspection and Removal CriteriaDocumento2 páginasWhen To Replace Your Ropes: Asme B30.30 Ropes For Details On The Requirements For Inspection and Removal CriteriaMike PoseidonAinda não há avaliações

- Managing People and OrganisationsDocumento50 páginasManaging People and OrganisationsOmkar DesaiAinda não há avaliações

- Digitech's s100 ManualDocumento24 páginasDigitech's s100 ManualRudy Pizzuti50% (2)

- 1536-Centrifugial (SPUN), FittingsDocumento23 páginas1536-Centrifugial (SPUN), FittingsshahidAinda não há avaliações

- MAD Lab Manual - List of ExperimentsDocumento24 páginasMAD Lab Manual - List of Experimentsmiraclesuresh67% (3)

- In 002756Documento1 páginaIn 002756aljanaAinda não há avaliações

- Level 3 Repair: 8-1. Components LayoutDocumento50 páginasLevel 3 Repair: 8-1. Components LayoutManuel BonillaAinda não há avaliações

- RESOLUTION (Authorize To Withdraw)Documento2 páginasRESOLUTION (Authorize To Withdraw)Neil Gloria100% (4)

- 809kW Marine Propulsion Engine SpecificationsDocumento2 páginas809kW Marine Propulsion Engine SpecificationsRoberto StepankowskyAinda não há avaliações

- Alfornon Joshua Madjos. Strategic Management Bsba 3FDocumento7 páginasAlfornon Joshua Madjos. Strategic Management Bsba 3FJoshua AlfornonAinda não há avaliações

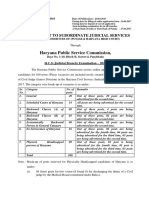

- HPSC Haryana Civil Service Judicial ExamDocumento6 páginasHPSC Haryana Civil Service Judicial ExamNDTV100% (1)

- Sachin Vinod Nahar: SVKM's Usha Pravin Gandhi College of ManagementDocumento3 páginasSachin Vinod Nahar: SVKM's Usha Pravin Gandhi College of ManagementSachin NaharAinda não há avaliações

- SEZOnline SOFTEX Form XML Upload Interface V1 2Documento19 páginasSEZOnline SOFTEX Form XML Upload Interface V1 2శ్రీనివాసకిరణ్కుమార్చతుర్వేదులAinda não há avaliações

- TOtal Quality ControlDocumento54 páginasTOtal Quality ControlSAMGPROAinda não há avaliações

- Form 16 - IT DEPT Part A - 20202021Documento2 páginasForm 16 - IT DEPT Part A - 20202021Kritansh BindalAinda não há avaliações

- Field Experience B Principal Interview DardenDocumento3 páginasField Experience B Principal Interview Dardenapi-515615857Ainda não há avaliações