Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Distorción de La Pirámide Alimenticia en Programas para Niños-Análisis Del Contenido de La Publicidad Televisiva Observada en Suiza

Enviado por

larst220 notas0% acharam este documento útil (0 voto)

21 visualizações6 páginasA content analysis of the commercials aired during the kids programmes of six Swiss, one German and one Italian stations was conducted in 2006. The commercials were collected over a 6-month period in 2006 and 1365h of kids programme were recorded. 3061 commercials (26.4%) for food, 2696 (23.3%) promoting toys, followed by those of media, cleaning products and cosmetics.

Descrição original:

Título original

Distorción de La Pirámide Alimenticia en Programas Para Niños-Análisis Del Contenido de La Publicidad Televisiva Observada en Suiza

Direitos autorais

© © All Rights Reserved

Formatos disponíveis

PDF, TXT ou leia online no Scribd

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoA content analysis of the commercials aired during the kids programmes of six Swiss, one German and one Italian stations was conducted in 2006. The commercials were collected over a 6-month period in 2006 and 1365h of kids programme were recorded. 3061 commercials (26.4%) for food, 2696 (23.3%) promoting toys, followed by those of media, cleaning products and cosmetics.

Direitos autorais:

© All Rights Reserved

Formatos disponíveis

Baixe no formato PDF, TXT ou leia online no Scribd

0 notas0% acharam este documento útil (0 voto)

21 visualizações6 páginasDistorción de La Pirámide Alimenticia en Programas para Niños-Análisis Del Contenido de La Publicidad Televisiva Observada en Suiza

Enviado por

larst22A content analysis of the commercials aired during the kids programmes of six Swiss, one German and one Italian stations was conducted in 2006. The commercials were collected over a 6-month period in 2006 and 1365h of kids programme were recorded. 3061 commercials (26.4%) for food, 2696 (23.3%) promoting toys, followed by those of media, cleaning products and cosmetics.

Direitos autorais:

© All Rights Reserved

Formatos disponíveis

Baixe no formato PDF, TXT ou leia online no Scribd

Você está na página 1de 6

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .. . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Distorted food pyramid in kids programmes:

A content analysis of television advertising

watched in Switzerland

Simone K. Keller, Peter J. Schulz

Institute of Communication and Health, Universita` della Svizzera italiana, Lugano, Switzerland

Correspondence: Simone K. Keller, Institute of Communication and Health, Faculty of Communication,

Universita` della Svizzera italiana, Via Giuseppe Buffi 13, 6904 Lugano, tel: +41-58-6664488,

fax: +41-58-6664647, e-mail: simone.keller@lu.unisi.ch

Received 13 November 2009, accepted 21 April 2010

Background: In the light of increasing childhood obesity, the role of food advertisements relayed on

television (TV) is of high interest. There is evidence of food commercials having an impact on childrens

food preferences, choices, consumption and obesity. We describe the product categories advertised

during kids programmes, the type of food promoted and the characteristics of food commercials

targeting children. Methods: A content analysis of the commercials aired during the kids

programmes of six Swiss, one German and one Italian stations was conducted. The commercials were

collected over a 6-month period in 2006. Results: Overall, 1365h of kids programme were recorded and

11 613 advertisements were found: 3061 commercials (26.4%) for food, 2696 (23.3%) promoting toys,

followed by those of media, cleaning products and cosmetics. Regarding the broadcast food advertise-

ments, 55% were for fast food restaurants or candies. Conclusion: The results of the content analysis

suggest that food advertising contributes to the obesity problem: every fourth advertisement is for

food, half of them for products high in sugar and fat and hardly any for fruit or vegetables. Long-term

exposure to this distortion of the pyramid of recommended food should be considered in the discussion

of legal restrictions for food advertising targeting children.

Keywords: advertising, children, content analysis, food, television

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Introduction

T

he World Health Organization (WHO) announced, as early

as 1998, that obesity should be regarded as todays

principal neglected public health problem.

1

In Europe, the

prevalence of childhood obesity is today 10-times than that

in the 1970s.

2

Recent data from the International Obesity

Taskforce show that in Europe 11 million children between

5 and 17 years of age are overweight and 3 million are obese.

There is a notable difference between the southern,

Mediterranean countries, where the prevalence of overweight

at 2035% is the highest, and the northern countries with a

prevalence of 1020%.

3

In Switzerland, data from 2004

indicate that 18% of the Swiss girls between 6 and 12 years

of age and 20% of the boys are overweight.

4

The causes of this epidemic are less clear. According to

Livingstone,

5

individual, social, environmental and cultural

factors influence childrens diet, and these multiple factors

interact in complex ways not yet well understood. TV

watching and food advertising have to be counted among

these factors. A causal association between TV and body

weight was first reported in 1985 by Dietz and Gortmaker

6

who found an increase of 2% in the prevalence of

overweight among American children for every additional

hour per day spent viewing TV. With regard to food

advertising on TV, children gained without any doubt

increased importance as a target group.

7

They dispose of a

growing amount of money they can spend on their own, and

their role as future consumers is already considered.

8

In 2004,

the US food, beverage and restaurant industry spent US$5

billion on TV advertising, including about US$1 billion to

target children directly.

9

Several reports have reviewed the impact of advertising on

childrens food preferences, choices, consumption and obesity/

health.

5,911

As Livingstone underlines in the most recent

review, it remains unclear whether the association between

overall TV exposure and obesity reflects the specific influence

of exposure to TV advertising or whether it is due to increased

snacking while viewing or to a sedentary lifestyle with reduced

exercise.

5

Nevertheless she concludes that there is a growing

consensus among experts that food advertisements influence

childrens food preferences, diet and health.

A recent study found that advertisements for nutritious

foods promote selected positive attitudes and beliefs

concerning these foods.

12

There is also evidence that

exposure to food advertisements increases food intake in

children, and that obese and overweight children are more

alert to food-related cues.

13,14

Several studies have analysed the composition and content

of advertising broadcast during childrens TV programmes.

They found an elevated amount of food advertisements, with

foods high in fat and sugar and low in fibre being the most

promoted categories.

1519

In Switzerland, no similar study has

been conducted so far. The aim of the present research is to

investigate the composition of product categories advertised

during kids programmes in Switzerland, the types of

promoted food and the strategies used in food commercials

targeted to children.

Methods

A content analysis of commercials of the six major TV

networks in Switzerland as well as one German and one

Italian network over the period from March to August 2006

European Journal of Public Health, Vol. 21, No. 3, 300305

The Author 2010. Published by Oxford University Press on behalf of the European Public Health Association. All rights reserved.

doi:10.1093/eurpub/ckq065 Advance Access published on 16 May 2010

b

y

g

u

e

s

t

o

n

A

u

g

u

s

t

2

4

,

2

0

1

3

h

t

t

p

:

/

/

e

u

r

p

u

b

.

o

x

f

o

r

d

j

o

u

r

n

a

l

s

.

o

r

g

/

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

f

r

o

m

was conducted. The sample includes 11 613 commercials. The

networks and programmes were chosen by means of two

criteria: most popular kids programmes had to be included

in the sample and the time slots when TV use among

children is high had to be covered. The kids programmes

Swiss children watch most were identified with the search

engine of publisuisse (http://www.publisuisse.ch/de/

research/mediennutzung/tv/top-sendungen.cfm). The 10 top

broadcasts were detected for the third week of January 2006;

criteria for the ranking were Kids and Youths as programme

type, and Children 316 years as target category. The analysis

was run separately for every language region. Among the 10

most watched kids programmes during this week, there were

also shows aired on two foreign channels, SuperRTL (In

Switzerland, SuperRTL broadcasts a Swiss advertising

window) in the German and Italia1 in the Italian language

region. Those channels were added to the sample. The

identified top programmes were not distributed over all day

times. Hence, to cover all the time slots when TV use among

children was identified to be high,

20

the kids programmes aired

during these slots were included for every channel, even if they

were not among the most popular broadcasts.

The final sample included only kids and no adults

programmes. Obviously, this does not correspond to the

total amount of childrens exposure to TV, as they also

watch adults programmes. The study, however, aimed at

analysing what kind of advertisement children are exposed to

when watching the programmes claimed to be suitable for

them.

Eight HDDDVD recorders registered the selected

programmes every second week on hard-disk; in the

alternate week, three coders, trained students of

Communication Science at the University of Lugano, coded

the recorded programme and the commercials broadcast

within the programmes. This method permitted us to

maintain a reasonable, yet workable sample; furthermore, to

maximize our sample of different food commercials, we

preferred a larger variety of different commercials over a

high number of repeats of commercials. The 6-month time

period allowed us to ascertain that properties of advertise-

ments during the kids programmes were more than just

phenomena that happened to occur in an arbitrarily selected

week. In fact, the proportion and composition of food adver-

tisement during kids programmes remained unvaried during

the 6 months.

A total of 1365 h containing 11 613 broadcast commercials

were recorded and analysed with a standardized codebook.

The codebook was developed specifically for this study

and consisted of four parts: the first three parts concerned

all recorded commercials, while the last part focused on

a deeper analysis of food advertisements. All 11 613 spots

were analysed according to their technical attributes, the

formal characteristics of the advertisement block and for

the product. The product categories were based on the

official classification used by the marketing research

company Mediafocus (www.mediafocus.ch/de/methodik/

marktsystematik). Additionally, every new food advertisement

was further coded with the fourth part of the codebook.

Examples of variables in this part are the specific type of

food (classification was again made according to the aforemen-

tioned classification), as well as the presentational styles, the

technique, the actors or the presence of jingles. In a final step,

the promised gratifications in the commercials were examined.

To allow comparison between advertisements targeted to

children and those targeted to adults, a general target was

assigned to every ad. In case of overlapping or doubt, the

commercial was coded as undefined target. Assignment

criteria for an advertisement targeted to children was a

global judgement of the main thrust of the advertisement,

including the presence of children, cartoon figures or famous

people as protagonists, fast pace, colours, easy language and

the nature of the persuasive appeal.

17,21

Not included in the

coding judgement was the target of the product, as some foods

targeted to kids (e.g. chocolate bars for school breaks) were

advertised in commercials targeted to adults (e.g. to the

mother).

The three coders were trained to analyse the commercials.

Initially, each coder viewed a first sample of advertisements

independently, and the responses of each coder to each item

were compared. Coding discrepancies were resolved through

discussion before analysis continued. Since each item

produced either unanimous or near-unanimous agreement

among the coders, the codebook was judged reliable.

Results

Between March and August 2006, 1365 h of kids TV

programme were recorded and 11 613 commercials were

found and analysed. Of them, 3061 were for food (26%)

consisting of 335 different commercials, 2696 promoted toys

(23%), followed by those of media, cleaning products,

cosmetics and other goods. There is, however, a big

difference between the six public channels in Switzerland and

the two private channels from Germany and Italy. Analysing

only the Swiss channels, the percentage of food advertisements

showed during the kids programmes was 37%. On the German

channel SuperRTL, the amount was lower with 32%, whereas

the Italian channel Italia1 had only a 15% rate of food adver-

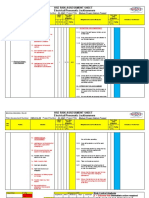

tisement, due to the many advertisements for toys (see table 1).

In a next step, we examined what food advertisements a

child is exposed to when watching the kids programmes

broadcast on the selected channels. The results are represented

in a food pyramid: the left half of the pyramid represents all

the broadcast food advertisements (n =3061), the right half is

based only on food advertisements targeting children

(n =1344) (see figure 1).

The left side of the pyramid shows what Swiss children really

see advertised during the kids programmes: fast food restaur-

ants (24%) or candies (31%), followed by cereals (13%) and

sweet beverages (14%), hardly any vegetables or fruits (3%).

Considering just the food advertisements targeted to children

on the right side of the pyramid, the share of the rather

unhealthy food categories like fast food restaurants (47%),

candies (24%) or sugared cereals (23%) was even higher.

Regarding advertising strategies, 35% of those advertisements

used a jingle, 39% contained cartoons or elements of cartoons,

42% showed children consuming the product and 29%

presented a fantasy world situation. Among the most

common appeals promised in the food commercials

targeting children we found fun (46%), sport/action (21%),

adventure (15%) and taste (8%). Of them 54% offered

premiums like toys, stickers or small games included in the

package.

In table 2, results are calculated for an average hour of TV

watching. A child watching exclusively the kids programmes

on Swiss channels sees five advertisements on average; an hour

watching kids programmes on Italia1 means 24.6 advertise-

ments and an hour of watching SuperRTL amounts to 8.7

advertisements. On the Swiss channels, 1.5 of the spots are

for foods high in sugar/salt and fat like, for example, fast

food, candies, sweet beverages, sugared cereals and salty

snacks; on Italia1 there are 2.6 such advertisements and on

SuperRTL 2.7/h. Furthermore, in table 2 the average number

of advertisements seen by children in Switzerland during 1 year

is calculated. The results are valid for kids with a daily amount

of TV consumption corresponding to the Swiss average of

110 min, and watching exclusively programmes labelled as

Distorted food pyramid in television advertisements 301

b

y

g

u

e

s

t

o

n

A

u

g

u

s

t

2

4

,

2

0

1

3

h

t

t

p

:

/

/

e

u

r

p

u

b

.

o

x

f

o

r

d

j

o

u

r

n

a

l

s

.

o

r

g

/

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

f

r

o

m

kids programmes. The number was computed by multiplica-

tion of the average number of advertisements per hour

with the average daily amount of TV viewing in hours,

times 365.

Discussion

Advertising during kids TV programmes

Food commercials dominate TV advertisement during kids

programmes (table 1). On the Swiss channels, over one-third

of advertisements broadcast were for food. This fits with the

results of a study conducted in 1996 among 13 OECD

countries.

22

In more than half of the countries, 40% of the

commercials were for food. The amount of food advertise-

ments ranged from 84% (Netherlands) to 12% (Sweden).

Regarding the different food categories, figure 1 shows a

food pyramid with completely inversed layers, with respect

to the recommended food pyramid.

23

In fact, looking at the

total amount of food advertisements in the left part of the

pyramid, candies and fast food restaurants (55%) are at the

basis, vegetables and fruits (3%) at the top. This misrepresen-

tation of the food pyramid could also be found in numerous

similar studies, which have scrutinized the composition of

food categories during kids programmes in the UK, USA or

Australia.

2428

On average, candies, breakfast cereals and

restaurants (virtually all for fast food restaurants) accounted

for more than half of all food advertisements.

With regard to frequency of occurrence, in the present

study commercials for food are followed by toys (23.2%)

mainly showed on Italia1, and media/entertainment (9.7%).

As table 1 shows, besides such commercials for products

targeted to children, also products targeted to adults

are promoted, such as computers, cosmetics or cleaning

agents.

Food commercials targeting children

As this gives evidence that advertisers expect not only kids but

also their parents to watch the kids programmes, we can

assume that also food advertisement is targeting both kids

and adults. For a further analysis it therefore makes sense to

subdivide the sample according to target groups (kids vs.

adults) and look just at the food advertisements designed for

children.

Under the assumption that the attention of children is

caught particularlyif not exclusivelyby commercials

targeted to kids, a more pertinent pyramid was created,

showing only the foods that were promoted in spots targeted

to children (right side of the pyramid in figure 1). Out of all

3061 broadcast food commercials, 1344 were judged to target

exclusively children. The advertised food pyramid changes

radically: fast food restaurants, candies and cereals

Table 1 Distribution of product categories broadcast during the selected kids programmes collected over 6 months

Product category Swiss channels Italia1 SuperRTL Total

n (%) n (%) n (%) n (%)

Food 1762 (36.6) 779 (15.1) 520 (31.8) 3061 (26.4)

High in sugar/salt and fat (percentage of food advertisements) 1459 (82.8) 546 (70.1) 509 (97.9) 2514 (82.1)

Toys 763 (15.9) 1782 (34.5) 151 (9.2) 2696 (23.2)

Media 500 (10.4) 486 (9.4) 137 (8.4) 1123 (9.7)

Computer/office 111 (2.3) 688 (13.3) 152 (9.3) 951 (8.2)

Cosmetics 296 (6.2) 166 (3.2) 366 (22.4) 828 (7.1)

Clothing 133 (2.8) 459 (8.9) 41 (2.5) 633 (5.5)

Cleaning agents 402 (8.4) 55 (1.1) 75 (4.6) 532 (4.6)

Other 843 (17.6) 752 (14.6) 194 (11.9) 1789 (15.4)

Total 4810 (100) 5167 (100) 1636 (100) 11 613 (100)

24% 47% Fastfood

1% 0% Snacks

11% 0% Other

4% 1% Fruits

3% 0% Instant Meals

13% 23% Cereals

14% 5% Sweet Beverages

31% 24% Candy

Figure 1 Percentage distribution of food categories of the broadcast advertisement

302 European Journal of Public Health

b

y

g

u

e

s

t

o

n

A

u

g

u

s

t

2

4

,

2

0

1

3

h

t

t

p

:

/

/

e

u

r

p

u

b

.

o

x

f

o

r

d

j

o

u

r

n

a

l

s

.

o

r

g

/

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

f

r

o

m

compromised >90% of all the 1344 broadcast commercials

exclusively targeting children. None of them was for fruit or

vegetables. These results are comparable with a recent US

study,

17

where 34% of food advertisements targeting children

and teens were for candies, 28% for cereals and 10% for fast

food, whereas 1% was for fruit juice and none was for fruits or

vegetables.

Advertisements seen in 1 year

According to cultivation theory,

29

heavy TV viewing and

long-term exposure can cultivate peoples perception of the

world. Therefore, if children (and their parents) are continu-

ally exposed to food advertisements as those aired on Swiss TV,

they could change their ideas of what is a normal diet. If we

assume a link between food advertisement and childrens

behaviour and consider the implications of cultivation

theory, then the results of the present study are cause for

concern, as the order of the layers in the presented nutrition

pyramid is the opposite of the advised food pyramid. To relate

the frequency of advertisements aired with the average TV

consumption of Swiss kids, the amount of advertisements

viewed per year of regular TV watching is estimated. In an

international comparison, Swiss children are not heavy TV

viewers; on average they watch 1.5 h of TV a day.

20

Only

24% of Swiss kids (1016 years) watch >3 h daily. In

Germany, 38.5% and in Italy 42.7% of the children spend

>3 h daily in front of the TV.

30

If a Swiss child with an average TV consumption of

110 min a day watches exclusively kids programmes, it is

exposed to 1232 advertisements for foods every year

(table 2). The average length of food advertisements in our

sample was 21 s. Consequently, a Swiss child spends 7.11 h

every year watching food commercials, if the average

110 min a day are spent on programmes labelled as kids

programmes.

Due to the high amount of advertisement and the high

amount of TV consumption in the USA, the average number

of food advertisements seen every day on kids programmes in

the the USA is 17, which amounts to 6045 every year corres-

ponding to 40 h of watching food advertisements

year-by-year.

17

Legal restrictions

In the light of cultivation theory and considering the evidence

of successful food advertising targeting children, the results put

the spotlight on legal restrictions for food advertisements

during kids programmes. Such restrictions could concern the

amount of advertisement, the products shown or the marketing

strategies used in advertisements targeting kids.

Some food industry advertisers and opponents of restric-

tions for food advertisements argue that there is no causal

link between advertising and obesity because advertising, in

the long term, has no persuasive effect.

31

But as Ehrenberg

stresses out in his weak theory of advertising, advertising

does not work only through persuasion. Its main role is to

reinforce and maintain existing behaviour patterns.

32

Hence,

supporting the continuation of unhealthy behaviour patterns,

advertising reduces the likelihood that individuals will

recognize the behaviours as unhealthy or seek to change

these.

33

Of course restrictions alone would not eliminate the obesity

problem but support other interventions: Hoek and Gendall

claim the need of paying more attention to a regulatory

environment, which will enable the success of social

marketing and education programmes in the field of obesity

prevention.

33

From a psychological point of view, restrictions

are supported by the evidence that children below the age of

78 years are a special audience with narrowed information-

processing capabilities. Therefore, advertising targeting

kids can be considered inherently unfair and should be

regulated.

34

It is difficult to ascertain the effectiveness of regulation in

countries, which have introduced such measures, as it is hard

to determine unequivocally possible effects of restrictions

in a reality with unstable obesity rates and with cross-border

TV broadcasts. While testing the effects on a practical level

will remain a difficult task, a recent literature review by

Veerman et al.

35

tried it on a theoretical level. With a math-

ematical simulation model, they estimated that a complete ban

on food advertising on TV may reduce the prevalence of

obesity among US children by 2.5%.

These findings can legitimize the numerous efforts made in

recent years regarding restrictions for food advertisements in

TV. In Switzerland, the discussion has not yet led to decisions

on a regulation level. In the near future, further research could

repeat the study in order to ascertain whether the amount of

advertisements for foods high in sugar and fat remains stable

over time.

Conclusions

In view of the rising epidemic of childhood obesity, TV kids

programmes presenting an inverted food pyramid during the

advertising break give reason to discuss the role and effects of

food advertising on TV. Of course, given the multiple channels

like in-school marketing, product placements in movies or the

internet, TV is just one of many sources of food advertisement

that can influence the childrens purchase behaviour. But TV

viewing has been firmly linked to childhood obesity. It is not

yet clear how much of this accepted effect is due to advertising

exposure and how much is due to reduced energy expenditure

during TV watching, but some evidence suggests that the latter

does not play a significant role.

36,37

Considering the development of childhood obesity and the

gravity of the health effects connected with it, regulation of

food advertisement targeting children during TV kids

programmes has to be considered. The precautionary

principle recommends that in presence of a threat of serious

damage to human health, a lack of full scientific knowledge

about the situation should not be allowed to delay contain-

ment or remedial steps. Hence, until scientific evidence

about the direct effect of food advertisements on childhood

obesity is available, the ban of commercials for foods

high in sugar/salt and fat could be seen as a precautionary

measure.

Table 2 Average number of advertisements in TV-kids programme in Switzerland compared with Italy and Germany

Swiss channels Italia1 SuperRTL TOTAL

n n n n

Advertisements per hour (per year

a

) 5 (3376) 24.6 (16 611) 8.7 (5875) 8.5 (5740)

Food advertisements per hour (per year

a

) 1.8 (1232) 3.7 (2505) 2.8 (1858) 2.2 (1514)

High in sugar/salt and fat per hour (per year

a

) 1.5 (1013) 2.6 (1756) 2.7 (1823) 1.8 (1215)

a: Exposure of Swiss children with an average daily TV consumption of 111min, watching exclusively shows labelled as kids

programmes. The number was computed by multiplication of the average number of advertisements per hour with the

average daily amount of TV viewing in hours, times 365.

Distorted food pyramid in television advertisements 303

b

y

g

u

e

s

t

o

n

A

u

g

u

s

t

2

4

,

2

0

1

3

h

t

t

p

:

/

/

e

u

r

p

u

b

.

o

x

f

o

r

d

j

o

u

r

n

a

l

s

.

o

r

g

/

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

f

r

o

m

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the FOPH for the support.

Part of the work was presented at the 58th Annual Conference

of the International Communication Association (ICA) 2008,

Montreal (Canada).

Funding

Federal Office of Public Health FOPH, Switzerland.

Conflicts of interest: None declared.

Key points

There is evidence that food commercials influence

childrens food preferences, choices and consumption,

suggesting a link to childhood obesity.

This study presents results from a content analysis of

the TV kids programmes broadcast by six Swiss, one

German and one Italian stations, collected over 6

months.

Out of 11 613 recorded commercials, 26.4% were for

food, of which more than half promoted fast food

restaurants or candies, but virtually none promoted

fruits or vegetables. This represents a distortion of

the recommended food pyramid.

Long-term exposure to such advertising damages

childrens diets. For this reason, legal restrictions for

food advertising targeting children should be

considered.

References

1 World Health Organization. Obesity: preventing and managing the Global

Epidemic-Report of a WHO Consultation on Obesity, Geneva, 35 June 1997.

Geneva: World Health Organization, Document WHO/NUT/NCD/98.1,

1998.

2 Branca F, Nikogosian H, Lobstein T. The challenge of obesity in the WHO

European region and the strategies for response. Copenhagen: World Health

Organization, 2007.

3 International Obesity Taskforce IOTF. EU childhood obesity out of control

2004; Available at: http://www.iotf.org/media/IOTFmay28.pdf (8 March

2010, date last accessed).

4 Zimmermann MB, Gubeli C, Puntener C, Molinari L. Overweight and

obesity in 612-year-old children in Switzerland. Swiss Med Wkly

2004;134:5238.

5 Livingstone S. Television advertising of food and drink products to children:

research Annexes 911. An Update Review of the literature prepared for the

Research Department of the Office of Communications (OFCOM) 2006;

Available at: http://www.ofcom.org.uk/consult/condocs/foodads/foodad-

sprint/annex9.pdf. (8 March 2010, date last accessed).

6 Dietz WH, Gortmaker SL. Do we fatten our children at the TV set?

Television viewing and obesity in children and adolescents. Pediatrics

1985;75:80712.

7 Wilcox BL, Cantor J, Dowrick P, et al. Report of the APA task force on

advertising and children. Washington, DC: American Psychological

Association, 2004.

8 The Henry J Kaiser Family Foundation. The role of media in Childhood

Obesity 2004; Available at: http://www.kff.org/entmedia/upload/The-Role-

Of-Media-in-Childhood-Obesity.pdf (8 March 2010, date last accessed).

9 McGinnis JM, Gootman JA, Kraak VI, editors, editors. Food marketing to

hildren and youth: Threat or opportunity? Committee on food marketing and

the diets of children and youth, institute of medicine of the national academies.

Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2006.

10 Hastings G, Stead M, McDermott L, et al. Review of research on the effects of

food promotion to children. Final Report to the UK Food Standards Agency.

Strathclyde: Centre for Social Marketing, 2003.

11 Livingstone S, Helsper E. Advertising foods to children: understanding

promotion in the context of childrens daily lives. A review of the literature

prepared for the Research Department of the Office of Communications

(OFCOM) 2004. Available at: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/21757/1/Advertising_

foods_to_children.pdf (8 March 2010, date last accessed).

12 Dixon H, Scully ML, Wakefield MA, et al. The effects of television

advertisements for junk food versus nutritious food on childrens food

attitudes and preferences. Soc Sci Med 2007;65:131123.

13 Halford JCG, Gillespie J, Brown V, et al. Effect of television

advertisements for foods on food consumption in children. Appetite

2004;42:2215.

14 Halford JCG, Boyland EJ, Hughes G, et al. Beyond-brand effect of television

(TV) food advertisements/commercials on caloric intake and food choice of

57-year-old children. Appetite 2007;49:2637.

15 Kunkel D, Gantz W. Childrens television advertising in the multi-channel

environment. J Comm 1992;42:13452.

16 Harrison K, Marske AL. Nutritional content of foods advertised

during the TV programs children watch most. Am J Public Health

2005;95:156874.

17 Gantz W, Schwartz N, Angelini JR, Rideout V. Food for thought: television

food advertising to children in the United States. Menlo Park, CA: Kaiser

Family Foundation, 2007.

18 Kotz K, Story M. Food advertisements during childrens Saturday morning

television programming: Are they consistent with dietary recommendations?

J Am Diet Ass 1994;94:1296300.

19 Taras HL, Gage M. Advertised foods on childrens television. Arch Pediatr

Adolesc Med 1995;149:64952.

20 Forschungsdienst SRGSSR. Die Mediennutzung von Kindern in der Schweiz -

gemessen und erfragt. Schweizerische Radio- und Fernsehgesellschaft

SRG SSR idee suisse, Bern 2004. Available at: http://www.publisuisse.

ch/media/pdf/research/zielgruppen/de/14228-Die_Mediennutzung_von_

Kindern_-_SRG_Studie_2004.pdf (8 March 2010, date last accessed).

21 Coalition of Food Advertising for Children CFAC. Childrens

health or corporate wealth? The case for banning television food

advertising to children. 2nd edn, Available at: http://www.cancercouncil.

com.au/cfac/downloads/briefing_paper.pdf (8 March 2010, date last

accessed), 2007.

22 Dibb S. A spoonful of sugar: television food advertising aimed at

children: an international comparative survey. London: Consumers

International, 1996.

23 Walter P, Infanger E, Muhlemann P. Food Pyramid of the Swiss Society for

Nutrition. Ann Nutr Metab 2007;51(Suppl 2):1520.

24 Chapman K, Nicholas P, Supramaniam R. How much food

advertising is there on Australian television? Health Promot Int 2006;

21:17280.

25 Chestnutt IG, Ashraf FJ. Television advertising of foodstuffs potentially

detrimental to oral healtha content analysis and comparison of

childrens and primetime broadcasts. Community Dent Health

2002;19:8689.

26 Powell LM, Szczypka G, Chaloupka FJ. Exposure to food advertising on

television among US children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2007;161:55360.

27 Rodd HD, Patel V. Content analysis of childrens television advertising in

relation to dental health. Br Dent J 2005;199:7102.

28 Morgan M, Fairchild R, Phillips A, et al. A content analysis of childrens

television advertising: focus on food and oral health. Publ Health Nutr

2009;12:74855.

29 Gerbner G, Gross L, Morgan M, et al. Growing up with television:

cultivation processes. In: Bryant J, Zillman D, editors. Media effects: advances

in theory and research. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 2002,

4367.

30 Janssen I, Katzmarzyk P, Boyce W, et al. Comparison of overweight and

obesity prevalence in school-aged youth from 34 countries and their

relationships with physical activity and dietary patterns. Obes Rev

2005;6:12332.

31 Young B. Does food advertising make children obese? Int J Advert Market

Child 2003;4:1925.

32 Ehrenberg A. Repetitive advertising and the consumer. J Advert Res

1974;14:2534.

304 European Journal of Public Health

b

y

g

u

e

s

t

o

n

A

u

g

u

s

t

2

4

,

2

0

1

3

h

t

t

p

:

/

/

e

u

r

p

u

b

.

o

x

f

o

r

d

j

o

u

r

n

a

l

s

.

o

r

g

/

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

f

r

o

m

33 Hoek J, Gendall P. Advertising and obesity: a behavioral perspective. J Health

Comm 2006;11:40923.

34 Kunkel D, Gantz W. Assessing compliance with industry self-regulation

of television advertising to children. J Appl Comm Res 1993;21:14862.

35 Veerman JL, Van Beeck EF, Barendregt JJ, Mackenbach JP. By how much

would limiting TV food advertising reduce childhood obesity? Eur J Publ

Health 2009;19:3659.

36 Epstein LH, Roemmich JN, Robinson JL, et al. A randomized trial

of the effects of reducing television viewing and computer use on

body mass index in young children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med

2008;162:23945.

37 Jackson DM, Djafarian K, Stewart J, Speakman JR. Increased television

viewing is associated with elevated body fatness but not with lower total

energy expenditure in children. Am J Clin Nutr 2009;89:16.

Distorted food pyramid in television advertisements 305

b

y

g

u

e

s

t

o

n

A

u

g

u

s

t

2

4

,

2

0

1

3

h

t

t

p

:

/

/

e

u

r

p

u

b

.

o

x

f

o

r

d

j

o

u

r

n

a

l

s

.

o

r

g

/

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

f

r

o

m

Você também pode gostar

- BF TSEK Slide Kit - 5july2012Documento31 páginasBF TSEK Slide Kit - 5july2012azuredreamAinda não há avaliações

- Holistic Centre: Case Study 1 - Osho International Meditation Centre, Pune, IndiaDocumento4 páginasHolistic Centre: Case Study 1 - Osho International Meditation Centre, Pune, IndiaPriyesh Dubey100% (2)

- Policy Brief Advertising New Media OnlineDocumento5 páginasPolicy Brief Advertising New Media Onlineapi-267120287Ainda não há avaliações

- PHP Listado de EjemplosDocumento137 páginasPHP Listado de Ejemploslee9120Ainda não há avaliações

- Job Description: Jette Parker Young Artists ProgrammeDocumento2 páginasJob Description: Jette Parker Young Artists ProgrammeMayela LouAinda não há avaliações

- TestertDocumento10 páginasTestertjaiAinda não há avaliações

- Television Food AdvertisingDocumento15 páginasTelevision Food AdvertisingNelly TejedaAinda não há avaliações

- Policy Brief Food Advertising To ChildrenDocumento4 páginasPolicy Brief Food Advertising To Childrenapi-267120287Ainda não há avaliações

- How Much Food Advertising Is There On AustralianDocumento9 páginasHow Much Food Advertising Is There On AustralianManish SharmaAinda não há avaliações

- Synopsis Content AnalysisDocumento26 páginasSynopsis Content AnalysisRavNeet KaUrAinda não há avaliações

- Int J Obest 2009 Magnus A Et AlDocumento9 páginasInt J Obest 2009 Magnus A Et AlINSTITUTO ALANAAinda não há avaliações

- Kapita Selekta The King B.Inggris 12 SMADocumento10 páginasKapita Selekta The King B.Inggris 12 SMAFathimah AuliaAinda não há avaliações

- Childhood Obesity: Causes and Consequences, Prevention and Management.No EverandChildhood Obesity: Causes and Consequences, Prevention and Management.Ainda não há avaliações

- Kompsiko ReviewDocumento96 páginasKompsiko ReviewDwinita Ayuni LarasatiAinda não há avaliações

- TV Food Advertising Increases Children's Preference For Unhealthy Foods, Study FindsDocumento1 páginaTV Food Advertising Increases Children's Preference For Unhealthy Foods, Study Findstcn93Ainda não há avaliações

- Health E-News Bulletin February 09Documento8 páginasHealth E-News Bulletin February 09Health LibraryAinda não há avaliações

- Clase 4 Food and Drinks Advertising Directed at Children oDocumento2 páginasClase 4 Food and Drinks Advertising Directed at Children oDaniel Alejandro BerraAinda não há avaliações

- A Content Analysis of Children's Television Advertising: Focus On Food and Oral HealthDocumento8 páginasA Content Analysis of Children's Television Advertising: Focus On Food and Oral HealthCristian OneaAinda não há avaliações

- Exposure To Food Advertising On Television, Food Choices and Childhood ObesityDocumento29 páginasExposure To Food Advertising On Television, Food Choices and Childhood ObesityAzam Ali ChhachharAinda não há avaliações

- New Insights Into The Field of Children and Adolescents' Obesity: The European PerspectiveDocumento9 páginasNew Insights Into The Field of Children and Adolescents' Obesity: The European PerspectiveAudio TechnicaAinda não há avaliações

- Pediatric Highlight Prevention of Overweight in Preschool Children: Results of Kindergarten-Based InterventionsDocumento9 páginasPediatric Highlight Prevention of Overweight in Preschool Children: Results of Kindergarten-Based InterventionsRiftiani NurlailiAinda não há avaliações

- Effect of Television Food Advertisement On Children's Food Purchasing RequestsDocumento8 páginasEffect of Television Food Advertisement On Children's Food Purchasing RequestsImran RafiqAinda não há avaliações

- Jurnal Obesitas RemajaDocumento8 páginasJurnal Obesitas RemajaDyah Annisa AnggrainiAinda não há avaliações

- Policies To Prevent Childhood Obesity in The European Union: T. Lobstein, L. A. BaurDocumento4 páginasPolicies To Prevent Childhood Obesity in The European Union: T. Lobstein, L. A. BaurruxandraplAinda não há avaliações

- Scientific Evidence On Preventive Interventions in Childhood ObesityDocumento8 páginasScientific Evidence On Preventive Interventions in Childhood ObesityRYANTI MARANATAAinda não há avaliações

- Viewpoint Article: Childhood Obesity - Looking Back Over 50 Years To Begin To Look ForwardDocumento5 páginasViewpoint Article: Childhood Obesity - Looking Back Over 50 Years To Begin To Look ForwardichalsajaAinda não há avaliações

- Introduction: The First Forum On Child Obesity InterventionsDocumento2 páginasIntroduction: The First Forum On Child Obesity InterventionsSiti SabariahAinda não há avaliações

- Foodmarketing AbroadDocumento2 páginasFoodmarketing AbroadAnne RomeAinda não há avaliações

- You Should Spend About 20 Minutes On Questions 1-13 Which Are Based On Reading Passage 1 BelowDocumento12 páginasYou Should Spend About 20 Minutes On Questions 1-13 Which Are Based On Reading Passage 1 BelowPhương VõAinda não há avaliações

- Breastfeeding and Dental Caries. Review of The Literature.: Geanina Besliu - Rosu OanaDocumento12 páginasBreastfeeding and Dental Caries. Review of The Literature.: Geanina Besliu - Rosu OanaAnamaria RagoscaAinda não há avaliações

- Case 2 7 McDonalds and ObesityDocumento4 páginasCase 2 7 McDonalds and ObesityZarlish Khan0% (1)

- Nurturing a Healthy Generation of Children: Research Gaps and Opportunities: 91st Nestlé Nutrition Institute Workshop, Manila, March 2018No EverandNurturing a Healthy Generation of Children: Research Gaps and Opportunities: 91st Nestlé Nutrition Institute Workshop, Manila, March 2018Ainda não há avaliações

- Võ Kiều Trang Mid-term TestDocumento6 páginasVõ Kiều Trang Mid-term TestTrang Võ KiềuAinda não há avaliações

- Reading 2Documento72 páginasReading 2Ng HoaAinda não há avaliações

- Childhood - Obesity Revision FullDocumento12 páginasChildhood - Obesity Revision FullHum NjorogeAinda não há avaliações

- Breastfeeding Rates and Programs in Europe: A Survey of 11 National Breastfeeding Committees and RepresentativesDocumento8 páginasBreastfeeding Rates and Programs in Europe: A Survey of 11 National Breastfeeding Committees and RepresentativesAdrian KhomanAinda não há avaliações

- Television and Children's Consumption Patterns A Review of The LiteratureDocumento15 páginasTelevision and Children's Consumption Patterns A Review of The LiteratureishaAinda não há avaliações

- Obesity Research Paper ThesisDocumento7 páginasObesity Research Paper Thesishmnxivief100% (2)

- Research ProposalDocumento13 páginasResearch Proposalapi-276849892Ainda não há avaliações

- Fast Food Advertising Should Be BannedDocumento6 páginasFast Food Advertising Should Be BannedNagalakshmy IyerAinda não há avaliações

- CLS WP 201716-Prevalence and Trend in Overweight and Obesity in Childhood and AdolescenceDocumento22 páginasCLS WP 201716-Prevalence and Trend in Overweight and Obesity in Childhood and Adolescencejustified13Ainda não há avaliações

- Research Highlight 34Documento2 páginasResearch Highlight 34alikaaasaAinda não há avaliações

- Part B 26 OutOfTheBox Q&ADocumento6 páginasPart B 26 OutOfTheBox Q&Afernanda1rondelliAinda não há avaliações

- Article ABP 2 Primer Torn (2020-21)Documento9 páginasArticle ABP 2 Primer Torn (2020-21)Rachel Sotolongo PiñeroAinda não há avaliações

- 062 PDFDocumento4 páginas062 PDFAlisha SinghAinda não há avaliações

- Buja 2017 Parental GamblingDocumento2 páginasBuja 2017 Parental GamblingvitorperonaAinda não há avaliações

- RCT Dimenhydrinate in Children With Infectious Gastroenteritis: A ProspectiveDocumento13 páginasRCT Dimenhydrinate in Children With Infectious Gastroenteritis: A ProspectiveNamira AhmedAinda não há avaliações

- According To Cooke and RomweberDocumento2 páginasAccording To Cooke and RomweberSheldon BazingaAinda não há avaliações

- Materna Child NutritionDocumento121 páginasMaterna Child NutritionArpon FilesAinda não há avaliações

- Literature Review Childhood Obesity PreventionDocumento5 páginasLiterature Review Childhood Obesity Preventiongihodatodev2100% (1)

- Childhood Obesity Research Paper ExampleDocumento5 páginasChildhood Obesity Research Paper Examplecakvaw0q100% (1)

- National School Food Policies: Mapping of Across The EU28 Plus Norway and SwitzerlandDocumento46 páginasNational School Food Policies: Mapping of Across The EU28 Plus Norway and SwitzerlandLindsey FletcherAinda não há avaliações

- IBFANDocumento11 páginasIBFANlrodríguez_309124Ainda não há avaliações

- Breastfeeding Initiation Commercial: Grant ProposalDocumento13 páginasBreastfeeding Initiation Commercial: Grant Proposallaurenkay20Ainda não há avaliações

- tmpAFA8 TMPDocumento85 páginastmpAFA8 TMPFrontiersAinda não há avaliações

- Doh ProgramsDocumento8 páginasDoh ProgramsClara CentineoAinda não há avaliações

- Briefing Causes of Childhood ObesityDocumento3 páginasBriefing Causes of Childhood ObesityHafiz hanan Hafiz hananAinda não há avaliações

- Tie Book - BeatrizDocumento12 páginasTie Book - BeatrizGuilherme OliveiraAinda não há avaliações

- Community JournalDocumento2 páginasCommunity Journalj2x5h4ffbbAinda não há avaliações

- Amit Kumar KumawatDocumento9 páginasAmit Kumar KumawatAmit Kumar kumawatAinda não há avaliações

- TB in Children ReferencesDocumento14 páginasTB in Children ReferencesJayson-kun LopezAinda não há avaliações

- Cause and Effect in Childhood ObesityDocumento17 páginasCause and Effect in Childhood ObesitySharon V.Ainda não há avaliações

- Action Against Hunger (Spain) The Sharing ExperimentDocumento5 páginasAction Against Hunger (Spain) The Sharing ExperimentPiu ChatterjeeAinda não há avaliações

- Awake! - 1964 IssuesDocumento769 páginasAwake! - 1964 Issuessirjsslut100% (1)

- W1 MusicDocumento5 páginasW1 MusicHERSHEY SAMSONAinda não há avaliações

- 12c. Theophile - de Divers ArtibusDocumento427 páginas12c. Theophile - de Divers Artibuserik7621Ainda não há avaliações

- Fundamental of Transport PhenomenaDocumento521 páginasFundamental of Transport Phenomenaneloliver100% (2)

- Bos 22393Documento64 páginasBos 22393mooorthuAinda não há avaliações

- Group Work, Vitruvius TriadDocumento14 páginasGroup Work, Vitruvius TriadManil ShresthaAinda não há avaliações

- Minneapolis Police Department Lawsuit Settlements, 2009-2013Documento4 páginasMinneapolis Police Department Lawsuit Settlements, 2009-2013Minnesota Public Radio100% (1)

- Thd04e 1Documento2 páginasThd04e 1Thao100% (1)

- Lecture 4 - Consumer ResearchDocumento43 páginasLecture 4 - Consumer Researchnvjkcvnx100% (1)

- Etsi en 300 019-2-2 V2.4.1 (2017-11)Documento22 páginasEtsi en 300 019-2-2 V2.4.1 (2017-11)liuyx866Ainda não há avaliações

- RBConcept Universal Instruction ManualDocumento19 páginasRBConcept Universal Instruction Manualyan henrique primaoAinda não há avaliações

- Bruce and The Spider: Grade 5 Reading Comprehension WorksheetDocumento4 páginasBruce and The Spider: Grade 5 Reading Comprehension WorksheetLenly TasicoAinda não há avaliações

- The Invisible Museum: History and Memory of Morocco, Jewish Life in FezDocumento1 páginaThe Invisible Museum: History and Memory of Morocco, Jewish Life in FezmagnesmuseumAinda não há avaliações

- Multigrade Lesson Plan MathDocumento7 páginasMultigrade Lesson Plan MathArmie Yanga HernandezAinda não há avaliações

- LPP-Graphical and Simplex MethodDocumento23 páginasLPP-Graphical and Simplex MethodTushar DhandeAinda não há avaliações

- Phil. Organic ActDocumento15 páginasPhil. Organic Actka travelAinda não há avaliações

- Lesson PlansDocumento9 páginasLesson Plansapi-238729751Ainda não há avaliações

- Dampak HidrokarbonDocumento10 páginasDampak HidrokarbonfikririansyahAinda não há avaliações

- The Municipality of Santa BarbaraDocumento10 páginasThe Municipality of Santa BarbaraEmel Grace Majaducon TevesAinda não há avaliações

- Vistas 1-7 Class - 12 Eng - NotesDocumento69 páginasVistas 1-7 Class - 12 Eng - Notesvinoth KumarAinda não há avaliações

- Laser For Cataract SurgeryDocumento2 páginasLaser For Cataract SurgeryAnisah Maryam DianahAinda não há avaliações

- Essential Nutrition The BookDocumento115 páginasEssential Nutrition The BookTron2009Ainda não há avaliações

- 9 Electrical Jack HammerDocumento3 páginas9 Electrical Jack HammersizweAinda não há avaliações

- Bar Waiter/waitress Duties and Responsibilities Step by Step Cruise Ship GuideDocumento6 páginasBar Waiter/waitress Duties and Responsibilities Step by Step Cruise Ship GuideAmahl CericoAinda não há avaliações

- Miraculous MedalDocumento2 páginasMiraculous MedalCad work1Ainda não há avaliações

- Solar SystemDocumento3 páginasSolar SystemKim CatherineAinda não há avaliações