Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

OECD Finance For Biodiversity Policy Highlights 2014

Enviado por

OECD_envTítulo original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

OECD Finance For Biodiversity Policy Highlights 2014

Enviado por

OECD_envDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Scaling

up nance

mechanisms

for biodiversity

POLICY HIGHLIGHTS

Scaling up nance

mechanisms for

biodiversity

2

.

OECD SCALING UP FINANCE MECHANISMS FOR BIODIVERSITY

Biodiversity loss is a major environmental challenge

facing humankind. Biodiversity - and associated

ecosystems - provide a range of invaluable services

to society that underpin human health, well-being

and economic growth. These include food, clean

water, flood protection and climate regulation.

However, the OECD Environmental Outlook to 2050

projects a further 10% loss in biodiversity by 2050

under business-as-usual, threatening the provision

of these services.

The OECD (2013) publication Scaling Up Finance Mechanisms for

Biodiversity considers the opportunities for scaling-up finance for

biodiversity from six so-called innovative financial mechanisms,

as classified under the Convention on Biological Diversity. These are:

l environmental fiscal reform;

l payments for ecosystem services;

l biodiversity offsets;

l markets for green products;

l biodiversity in climate change funding; and

l biodiversity in international development finance.

Drawing on literature and more than 40 case studies worldwide,

the book addresses the following questions:

l What are these mechanisms and how do they work?

l How much finance have they mobilised and what potential is

there to scale this up?

l What are the key design and implementation issues including

environmental and social safeguards that need to be addressed

so that governments can help ensure these mechanisms

are environmentally effective, economically efficient and

distributionally equitable?

P

O

L

I

C

Y

H

I

G

H

L

I

G

H

T

S

OECD SCALING UP FINANCE MECHANISMS FOR BIODIVERSITY

.

3

Biodiversity the diversity of living organisms and the ecosystems

of which they are a part provide critical lifesupport functions and

services to society. These include food, clean water, genetic resources,

flood protection, nutrient cycling and climate regulation, amongst many

others. These services in turn are essential to human health, security,

wellbeing and economic growth. Yet despite the significant economic,

social and cultural benefits provided by biodiversity and ecosystem

services, global biodiversity continues to decline. Projections indicate

that without renewed efforts to address this challenge, a further 10%

loss of global biodiversity is expected between 2010 and 2050.

Given that the costs of inaction are in many cases considerable, there is

an urgent need for both:

l broader and more ambitious application of policies and incentives

to address biodiversity and ecosystem service conservation and

sustainable use, including those that are able to mobilise finance for

biodiversity;

l more efficient use of existing financial resources for biodiversity.

The 2013 OECD publication on Scaling Up Finance Mechanisms for

Biodiversity considers opportunities for scaling-up finance for

biodiversity across six innovative financial mechanisms as classified by

the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD). These are: environmental

fiscal reform; payments for ecosystem services; biodiversity offsets;

markets for green products; biodiversity in climate change funding;

and biodiversity in international development finance. This brochure

highlights the key findings of this work.

Biodiversity loss a major

environmental challenge with

far-reaching adverse impacts

DID YOU KNOW

the finance needs for

implementing the twenty

Aichi Biodiversity Targets are

estimated to be USD 150-440

billion per year?

4

.

OECD SCALING UP FINANCE MECHANISMS FOR BIODIVERSITY

ENVIRONMENTAL FISCAL REFORM refers to the process of shifting the

tax burden from desirable economic activities to activities that entail

negative environmental externalities. There are relatively few examples

of tax shifting in the context of biodiversity, so this book looks more

broadly at a range of taxation and pricing measures that can raise fiscal

revenues while furthering environmental goals. This includes taxes and

charges on natural resource use or on pollution, on resource rents, and

the reform of subsidies harmful to environment. Biodiversityrelevant

taxes and charges include those on pesticides, fertilisers and other

sources of NO

X

, SO

2

and CO

2

emissions, natural resource extraction,

wastewater discharges and entrance fees to natural parks. Total revenue

from environmentally related taxes in OECD countries in 2010 amounted

to nearly USD 700 billion. However, revenues from taxes on pollution and

resources ( those most relevant for biodiversity) constitute a very small

fraction of this total. Further efforts are also needed to reform subsidies

that are harmful for biodiversity. This would also free up a considerable

amount of revenue.

PAYMENTS FOR ECOSYSTEM SERVICES (PES) are voluntary programmes

that provide direct incentives to enhance the provision of ecosystem

services. PES compensate individuals or communities whose land use

or other resource management decisions influence the provision of

ecosystem services for the additional costs of providing these services.

They have been defined as a voluntary, conditional agreement between

at least one seller and one buyer over a well defined environmental

service or a land use presumed to produce that service. PES

programmes have proliferated rapidly over the past decade, with more

than 300 programmes implemented around the world. It is estimated

that 5 national PES programmes alone channel more than USD 6 billion

per year. Another study estimates that payments for watershed services

in 2008 totalled over USD 9 billion.

BIODIVERSITY OFFSETS are instruments used to allow some continued

project development, within an overall objective of no net loss of

biodiversity. More specifically, biodiversity offsets are measurable

conservation outcomes resulting from actions designed to compensate

for significant residual adverse biodiversity impacts arising from project

How do these

finance mechanisms

work?

P

O

L

I

C

Y

H

I

G

H

L

I

G

H

T

S

OECD SCALING UP FINANCE MECHANISMS FOR BIODIVERSITY

.

5

development after appropriate prevention and mitigation measures

have been taken. They are intended to be carried out during the

final step of the environmental impact mitigation hierarchy avoid,

minimize, and mitigate (restore and offset) and are based on the

premise that impacts from development can be offset if sufficient

habitat can be protected, enhanced or established elsewhere. Interest

in these programmes has increased in recent years, with about

45 programmes in place today that require biodiversity offsets or

some form of compensatory conservation for particular types of

impacts. In 2011, these were estimated to have mobilised between

USD 2.4 and 4 billion.

MARKETS FOR GREEN PRODUCTS have developed for goods

and services that are based on sustainable use of biodiversity

and ecosystems (ecotourism and biotrade), goods that have been

produced with fewer impacts on biodiversity as a result of more

efficient or lower impact production methods (timber procured from

reduced impact logging), and goods whose consumption will have a

reduced environmental impact as a result of decreased pollution load

(biodegradable detergent). As some consumers may prefer to buy

and even pay a premium for green products, companies may have an

incentive to adopt more sustainable production practices. Markets

for certain green products have seen considerable growth (certified

timber and seafood products) and new markets are emerging

(sustainable soy and sugar). Price premiums for green products

appear to be low but can vary considerably.

BIODIVERSITY IN CLIMATE CHANGE FUNDING refers to the

potential to leverage biodiversity cobenefits within the increasing

flow of finance that is directed towards climate change mitigation

and adaptation. Notable examples of where synergies can be

harnessed include the mechanism for Reducing Emissions from

Deforestation and Degradation and ecosystembased adaptation.

Climate change finance flows have been estimated at USD

70-120 billion annually in 2009-10, with lower bound estimates of

biodiversityrelated climate change finance from multilateral sources

amounting to USD 8 billion.

BIODIVERSITY IN INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT FINANCE refers

to the opportunities to harness synergies and better mainstream

biodiversity in broader development objectives. Biodiversityrelated

bilateral Official Development Assistance (ODA), as tracked by

the OECD Development Assistance Committee, increased from an

average of USD 3.3 billion per year in 2005-06 to USD 5.7 billion per

year in 2009-10.

Finance Scope of Source of Direct vs. Indirect Impact on drivers Beneciary vs.

mechanism nance nance revenue raising of biodiversity loss Polluter pays

Environmental Local, national Private (and public) Direct Yes direct Polluter

Fiscal Reform

Payments for Local, national, Private and public Direct Yes direct Beneciary

Ecosystem Services international

Biodiversity offsets Local, national Private (and public) Direct Yes direct Polluter

Markets for Local, national, Public Indirect Yes indirect N/A

Green Products international

Biodiversity in Local, national, Public and private Indirect Depends Polluter

climate change international

funding

Biodiversity in International Public (and private) Indirect Depends N/A

international

development nance

6

.

OECD SCALING UP FINANCE MECHANISMS FOR BIODIVERSITY

There are three ways in which these nance

mechanisms can promote the conservation and

sustainable use of biodiversity: rst, by raising

additional revenue that can then be used to achieve

biodiversity objectives (e.g. payments for ecosystem

services). Second, by mainstreaming biodiversity in

the production and consumption landscape (e.g. via

green markets and biodiversity offsets when placed in

the broader mitigation hierarchy). Third, by reducing

the cost of achieving biodiversity conservation and

sustainable use (e.g. environmental scal reform).

Some mechanisms can work across more than one

of these areas. For example, scal instruments can

raise revenue and reduce the cost of undertaking

biodiversity conservation and sustainable use

measures, while also changing incentives that drive

conversion rather than conservation.

Elements that vary across the six nance mechanisms

include whether they are able to mobilise nance at

the local, national and/or international level; whether

the source of nance is public and/or private; whether

they raise revenue directly; the extent to which the

mechanisms impact on the drivers of biodiversity loss

and degradation; and whether they are based on the

polluter pays principle or a beneciary pays approach:

How do the finance mechanisms

compare?

Finance Scope of Source of Direct vs. Indirect Impact on drivers Beneciary vs.

mechanism nance nance revenue raising of biodiversity loss Polluter pays

Environmental Local, national Private (and public) Direct Yes direct Polluter

Fiscal Reform

Payments for Local, national, Private and public Direct Yes direct Beneciary

Ecosystem Services international

Biodiversity offsets Local, national Private (and public) Direct Yes direct Polluter

Markets for Local, national, Public Indirect Yes indirect N/A

Green Products international

Biodiversity in Local, national, Public and private Indirect Depends Polluter

climate change international

funding

Biodiversity in International Public (and private) Indirect Depends N/A

international

development nance

P

O

L

I

C

Y

H

I

G

H

L

I

G

H

T

S

OECD SCALING UP FINANCE MECHANISMS FOR BIODIVERSITY

.

7

Finance Mechanism Individual capacity Organisational capacity Enabling conditions

Environmental Fiscal Reform

Payments for Ecosystem Services

Biodiversity offsets

Markets for Green Products

Biodiversity in climate change funding

Biodiversity in international development

nance

Careful design and implementation of nance mechanisms is required

to ensure the environmental effectiveness, cost-effectiveness, and

distributional equity. Key design and implementation issues that

should be considered for a number of these mechanisms include the

use of biodiversity metrics and indicators, additionality (i.e. ensuring

that environmental outcomes are above business-as-usual), leakage

(i.e. when the reduction of biodiversity loss in one location leads to the

displacement of pressure to another location), permanence

(i.e. maintaining the biodiversity benets over time), robust monitoring,

reporting and verication, and the enforcement of sanctions in the case

of non-compliance.

Environmental as well as social safeguards play an important role

in preventing and mitigating undue harm to the environment or to

poor and vulnerable populations. The introduction of any new policy

instrument (e.g., economic, traderelated, or for environmental objectives)

can impact on other policy areas and sectors, creating both winners

and losers. These potential impacts need to be identied in advance,

with the appropriate safeguards put in place so as to address any

possible tradeoffs. Such safeguards include standards and performance

indicators, as well as processes such as project screening, environmental

and social assessments, and stakeholder participation to identify possible

concerns and impacts on local populations, exante. Monitoring, reporting

and evaluation of social impacts is another important safeguard and

is necessary to inform the management of existing projects as well

as the design of future policy and projects. Grievance mechanisms or

ombudsmen also need to be in place to enable stakeholders to voice their

concerns about the way in which a nance mechanism is implemented

and managed.

Design and implementation

issues and the role of

environmental and social

safeguards

8

.

OECD SCALING UP FINANCE MECHANISMS FOR BIODIVERSITY

Finance Mechanism Individual capacity Organisational capacity Enabling conditions

Skilled advocates to secure political

acceptance and public support for EFR

through e.g. awareness campaigns

Experts (external or internal) can identify

metrics and carry out assessments to

inform targeting of payments for public

PES programmes

Experts to select and apply metrics and

indicators to compare expected losses

and gains

Trained experts to carry out certication

and accreditation

Technical expertise and knowledge

related to green infrastructure and

ecosystem based adaptation approaches

Development support staff have a

thorough understanding of the local

level linkages between development,

biodiversity loss and poverty

Processes for dialogue and consultation,

information dissemination and advocacy

with key stakeholders (including via civil

society groups)

Systems in place to ensure that payments

are delivered efciently and to the

appropriate recipient avoiding elite

capture etc.

Market support services (e.g. assurance,

public registries, brokerage etc.)

Distribution channels to deliver certied

products in competitive manner

(particularly for local communities

marginalised from premium markets)

Systems to manage and distribute funds

in an efcient and equitable manner

Guidelines for the application of

environmental and social safeguards (e.g.

SEA and environmental screening tools)

Established tax system capable of levying,

collecting and redistributing revenues

Inclusion of ecosystem service provisions

in sector strategies, Poverty Reduction

Strategy Papers, etc. and coherency

between policies

Laws requiring developers to compensate

for their environmental damages

Green procurement policies (including

public procurement policies)

National climate change mitigation

and adaptation strategies explicitly

recognising REDD+ and ecosystem based

adaptation options

Development support providers have

commitment to environment strategy

linked to poverty reduction and the MDGs

Governance and capacity issues

for effective implementation

The governance and institutional capacity needed to

implement a chosen instrument must be carefully

considered, as without certain prerequisites in place,

it is unlikely that the mechanism will effectively

achieve its intended goal(s). For example, secure and

clearly dened property and land tenure rights are

needed for a range of these mechanisms; where these

CAPACI TY NEEDS

Examples of capacity needs for the six nance mechanisms

are not present, international development nance

can play an important role in helping to foster their

development. In many cases, it may be prudent to start

with smaller programmes, including pilots, ensuring that

the necessary capacity is in place to implement these

mechanisms effectively, rather than with larger scale,

but ill-designed programmes.

P

O

L

I

C

Y

H

I

G

H

L

I

G

H

T

S

OECD SCALING UP FINANCE MECHANISMS FOR BIODIVERSITY

.

9

Each of these mechanisms has an important role to

play in addressing the global biodiversity challenge.

While all of these mechanisms have the potential

to be scaled-up, this potential is likely to be greater

for those mechanisms that are able to mobilise

nance from the private sector. Governments will

have a critical role to play in providing the necessary

legislative framework so as to provide the appropriate

incentives for the private sector to engage in

biodiversity conservation and sustainable use.

Governments will need to draw on regulatory

approaches, as well as other economic, information

and voluntary instruments, and to identify the

most appropriate policy mixes. This is particularly

important in the case of biodiversity, as the drivers

of loss and degradation are often multiple and stem

from market and government failures prevalent in

An assessment framework

biodiversity policy, as well as policies in other sectors

of the economy. The appropriate choice of policy mix

will depend on:

l the nature of the environmental problem and

drivers of loss;

l socioeconomic, cultural and political circumstances;

l the governance and institutional capacity needed to

effectively implement instruments.

The assessment framework below provides a

simplied, birds-eye view of the types of issues that

policymakers may need to consider and the possible

sequencing of steps, prior to the introduction of

new instruments and mechanisms for biodiversity

conservation and sustainable use.

10

.

OECD SCALING UP FINANCE MECHANISMS FOR BIODIVERSITY

Assess

business-as-

usual

P I L O T P R O J E C T S A N D C O U N T R Y E X P E R I E N C E S

Identify

market/policy

failures

Develop

long-term

vision

Identify

least-cost

policy options

Identify

safeguards

Identify

capacity

needs

lWhat are the key proximate drivers of biodiversity and ecosystem service loss (recent and projected)?

This can be determined with an assessment of business-as-usual projections for biodiversity trends (taking

into account population and economic growth, demand for agiculture, and other variables). This would help to

determine the reference point (or baseline) against which future progress could be assessed.

lWhat are the key sources of market and policy failure for each of these drivers of biodiversity and ecosystem

service loss (e.g. externalities and imperfect information) at the local, national and international level.

lDevelop a long-term vision for green growth and biodiversity with a joint high-level task force so as to mainstream

biodiversity into other policy areas and sectors (e.g. agriculture; energy; climate change; development; nance).

This would aim to ensure a more co-ordinated and cohesive response to biodiversity objectives, capturing

available synergies and identifying potential trade-offs. High-level commitment is crucial at this stage.

lWhat instruments are most likely to meet the intended goals?

lIdentify least-cost policy options and mechanisms and areas for intervention to determine policy priorities and

sequencing.

lWhat are the potential environmental trade-offs? Put in place environmental safeguards to address these as

needed.

lWhat are the likely distributional implications of the instrument? Consider social safeguards to address these

as needed.

lWhat are the governance and capacity needs to effectively implement these instruments?

lAre the circumstances/conditions needed for these to be effective in place?

S

T

A

K

E

H

O

L

D

E

R

E

N

G

A

G

E

M

E

N

T

Assessment Framework for Biodiversity Instruments and Mechanisms

P

O

L

I

C

Y

H

I

G

H

L

I

G

H

T

S

OECD SCALING UP FINANCE MECHANISMS FOR BIODIVERSITY

.

11

BETTER POLICIES FOR BETTER LIVES

For more information:

www.oecd.org/env/biodiversity

Human impacts on biodiversity and ecosystem services

must be signicantly reduced. Continuing on a business-

as-usual trajectory will have wide-reaching adverse

implications, and undermine green growth. The OECD

publication Scaling Up Finance Mechanisms for

Biodiversity aims to contribute to discussions on resource

mobilisation under the Convention on Biological Diversity.

The book examines the six so-called innovative nancial

mechanisms, as identied under the Convention on

Biological Diversity. It identies a number of key issues that

should be considered when designing and implementing

these mechanisms.

This policy brief outlines the key messages in the book. It

introduces the mechanisms, providing an overview of how

they work and how they compare. It examines key design

and implementation features that need to be considered,

including environmental and social safeguards, and looks at

the governance and capacity needs for implementing nance

mechanisms. Finally, it proposes an assessment framework

which provides a simplied, birds-eye view of the types of

issues that policy makers may need to consider and the

possible sequencing of steps, prior to the introduction of new

instruments and mechanisms for biodiversity conservation

and sustainable use.

This work was carried

out with the nancial

assistance of the

European Commission,

Switzerland and the

United Kingdom.

The views expressed herein can in no way be taken to

reect the ofcial opinion of the European Union.

BETTER POLICIES FOR BETTER LIVES

Scaling

up nance

mechanisms

for biodiversity

POLICY HIGHLIGHTS

Você também pode gostar

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- WATER - Greening Household Behaviour 2014Documento4 páginasWATER - Greening Household Behaviour 2014OECD_envAinda não há avaliações

- Greening Household Behaviour Policy Paper 2014Documento36 páginasGreening Household Behaviour Policy Paper 2014OECD_envAinda não há avaliações

- WASTE - Greening Household Behaviour 2014Documento4 páginasWASTE - Greening Household Behaviour 2014OECD_envAinda não há avaliações

- Mobilising Private Investment in Clean Energy Infrastructure: What's Happening 2015Documento8 páginasMobilising Private Investment in Clean Energy Infrastructure: What's Happening 2015OECD_envAinda não há avaliações

- FOOD - Greening Household Behaviour 2014Documento4 páginasFOOD - Greening Household Behaviour 2014OECD_envAinda não há avaliações

- Infographic Cost of Air Pollution 2014Documento1 páginaInfographic Cost of Air Pollution 2014OECD_envAinda não há avaliações

- Mobilised Private Climate Finance 2014 - Policy PerspectivesDocumento12 páginasMobilised Private Climate Finance 2014 - Policy PerspectivesOECD_envAinda não há avaliações

- ENERGY - Greening Household Behaviour 2014Documento4 páginasENERGY - Greening Household Behaviour 2014OECD_envAinda não há avaliações

- Sustainable Transport Brochure POLICY PERSPECTIVES 2014Documento16 páginasSustainable Transport Brochure POLICY PERSPECTIVES 2014OECD_envAinda não há avaliações

- TRANSPORT - Greening Household Behaviour 2014Documento4 páginasTRANSPORT - Greening Household Behaviour 2014OECD_envAinda não há avaliações

- Fossil Fuels Infographic 2014 Gas Petrol CoalDocumento1 páginaFossil Fuels Infographic 2014 Gas Petrol CoalOECD_envAinda não há avaliações

- OECD Work On Climate Change 2014Documento76 páginasOECD Work On Climate Change 2014OECD_envAinda não há avaliações

- Japan 2010 Environmental Performance Review - HighlightsDocumento8 páginasJapan 2010 Environmental Performance Review - HighlightsOECD_envAinda não há avaliações

- Israel 2011 Environmental Performance Review - HighlightsDocumento8 páginasIsrael 2011 Environmental Performance Review - HighlightsOECD_envAinda não há avaliações

- Norway 2011 Environmental Performance Review - HighlightsDocumento8 páginasNorway 2011 Environmental Performance Review - HighlightsOECD_envAinda não há avaliações

- Slovak Republic 2011 Environmental Performance Review - HighlightsDocumento8 páginasSlovak Republic 2011 Environmental Performance Review - HighlightsOECD_envAinda não há avaliações

- South Africa Environmental Performance Review - HighlightsDocumento16 páginasSouth Africa Environmental Performance Review - HighlightsOECD_envAinda não há avaliações

- Portugal 2011 Environmental Performance Review - HighlightsDocumento8 páginasPortugal 2011 Environmental Performance Review - HighlightsOECD_envAinda não há avaliações

- Italy 2013 Environmental Performance Review - HighlightsDocumento8 páginasItaly 2013 Environmental Performance Review - HighlightsOECD_envAinda não há avaliações

- Slovenia 2012 Environmental Performance Review - HighlightsDocumento8 páginasSlovenia 2012 Environmental Performance Review - HighlightsOECD_envAinda não há avaliações

- Germany 2012 Environmental Performance Review - HighlightsDocumento8 páginasGermany 2012 Environmental Performance Review - HighlightsOECD_envAinda não há avaliações

- OECD Work On Environment 2013-14Documento42 páginasOECD Work On Environment 2013-14OECD_envAinda não há avaliações

- CIRCLE Brochure 2014Documento12 páginasCIRCLE Brochure 2014OECD_envAinda não há avaliações

- Austria 2013 Environmental Performance Review - HighlightsDocumento12 páginasAustria 2013 Environmental Performance Review - HighlightsOECD_envAinda não há avaliações

- Mexico 2013 Environmental Performance Review - HighlightsDocumento8 páginasMexico 2013 Environmental Performance Review - HighlightsOECD_envAinda não há avaliações

- Environment Health Safety Brochure 2013Documento36 páginasEnvironment Health Safety Brochure 2013OECD_envAinda não há avaliações

- Chemicals Green Growth 2014Documento8 páginasChemicals Green Growth 2014OECD_envAinda não há avaliações

- OECD Work On Modelling 2014Documento16 páginasOECD Work On Modelling 2014OECD_envAinda não há avaliações

- OECD Work On Biodiversity 2014Documento20 páginasOECD Work On Biodiversity 2014OECD_envAinda não há avaliações

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (890)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (399)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (344)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (265)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2219)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (119)

- EVS Project on Positives and Negatives of Small and Big DamsDocumento16 páginasEVS Project on Positives and Negatives of Small and Big Damskartik jain50% (2)

- Research 2. Rrl. PrettyDocumento4 páginasResearch 2. Rrl. PrettyJamal F. Lamag100% (1)

- Has Reintroducing Wolves Really Saved Yellowstone's EcosystemDocumento2 páginasHas Reintroducing Wolves Really Saved Yellowstone's EcosystemArianne GarciaAinda não há avaliações

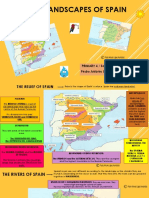

- Unit 3. The Landscapes of SpainDocumento7 páginasUnit 3. The Landscapes of SpainAnonymous pxoQu65t6xAinda não há avaliações

- Geography of IndiaDocumento49 páginasGeography of IndiaRamkrishna ChoudhuryAinda não há avaliações

- Midas Vent Rise EADocumento102 páginasMidas Vent Rise EAnevadablueAinda não há avaliações

- Population Biology of The Florida Manat'EeDocumento300 páginasPopulation Biology of The Florida Manat'EeAnonymous uuV9d4r3Ainda não há avaliações

- Aquino Issues EO 23 On Indefinite Log BanDocumento2 páginasAquino Issues EO 23 On Indefinite Log BanKen AliudinAinda não há avaliações

- 5-3 Retention and Detention BasinsDocumento7 páginas5-3 Retention and Detention Basinsnico ruhulessinAinda não há avaliações

- Giant PandaDocumento6 páginasGiant PandaJasvinder SinghAinda não há avaliações

- Why Should We Care About The EnvironmentDocumento2 páginasWhy Should We Care About The EnvironmentKyla Vama DeligeroAinda não há avaliações

- Why Biodiversity and The Interconnected Web of Life Are ImportantDocumento3 páginasWhy Biodiversity and The Interconnected Web of Life Are ImportantAzmi AlsayesAinda não há avaliações

- Climate Change Impact Assessment On Hydrology of IndianDocumento38 páginasClimate Change Impact Assessment On Hydrology of IndianarjunAinda não há avaliações

- Laporan Akhir - Perubahan Lahan Danau - 1996-2010Documento16 páginasLaporan Akhir - Perubahan Lahan Danau - 1996-2010ilo halidAinda não há avaliações

- Factors Causing FloodingDocumento13 páginasFactors Causing Floodingteuku afrianAinda não há avaliações

- Index: Project:-Sustainable DevelopmentDocumento17 páginasIndex: Project:-Sustainable DevelopmentSahil RajputAinda não há avaliações

- Biodiversity HotspotsDocumento11 páginasBiodiversity HotspotsChaitrali ChawareAinda não há avaliações

- Level 9 - Reading Task 2-Test PaperDocumento1 páginaLevel 9 - Reading Task 2-Test PaperBC EimorAinda não há avaliações

- Factsheet Man-Made FibresDocumento6 páginasFactsheet Man-Made FibresPrabaharan GunarajahAinda não há avaliações

- Case Study - United Nations Development Programme (Ver 1.1)Documento12 páginasCase Study - United Nations Development Programme (Ver 1.1)irmuhidinAinda não há avaliações

- Integrated Sustainable DesignDocumento161 páginasIntegrated Sustainable DesignDimitris Sampatakos100% (1)

- Forest Cover Change Detection Using Remote Sensing and GIS - A Study of Jorhat and Golaghat District, AssamDocumento5 páginasForest Cover Change Detection Using Remote Sensing and GIS - A Study of Jorhat and Golaghat District, AssamSEP-PublisherAinda não há avaliações

- Natural Resources Management IntroDocumento14 páginasNatural Resources Management IntroJoaquin David Magana100% (2)

- Bamboo and Climate ChangedDocumento30 páginasBamboo and Climate ChangedCu UleAinda não há avaliações

- Writing Polar BearDocumento4 páginasWriting Polar BearGaMesCaroLinaAinda não há avaliações

- Centre #1 SustainabilityDocumento6 páginasCentre #1 SustainabilityJolene ReneaAinda não há avaliações

- CLIMA OverheatedDocumento263 páginasCLIMA OverheatedClaudio TesserAinda não há avaliações

- Pros and Cons of Hydroelectric PowerDocumento4 páginasPros and Cons of Hydroelectric PowerVenugopal ReddyvariAinda não há avaliações

- Env QuizDocumento9 páginasEnv QuizKetan DhondeAinda não há avaliações

- The Issue's of Deforestation in Southern AfricaDocumento6 páginasThe Issue's of Deforestation in Southern AfricaVincent Madidimalo100% (6)