Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Levin-Richardson - Graffiti and Masculinity in Pompeii PDF

Enviado por

Paqui Fornieles MedinaDescrição original:

Título original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Levin-Richardson - Graffiti and Masculinity in Pompeii PDF

Enviado por

Paqui Fornieles MedinaDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

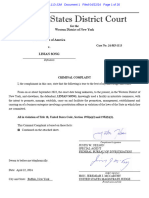

Facilis hic futuit: Graffiti and Masculinity in Pompeii's 'Purpose-Built'

Brothel

Sarah Levin-Richardson

Helios, Volume 38, Number 1, Spring 2011, pp. 59-78 (Article)

Published by Texas Tech University Press

DOI: 10.1353/hel.2011.0001

For additional information about this article

Access Provided by Universidad de Malaga at 12/12/12 6:10PM GMT

http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/hel/summary/v038/38.1.levin-richardson.html

d

Facilis hic futuit

Grafti and Masculinity in Pompeiis

Purpose-Built Brothel

SARAH LEVIN- RICHARDSON

Phoebus / bonus futor (Phoebus is a good fukr, CIL IV 2248, Add. 215);

Froto plane / lingit cun/num (Froto openly licks cunt, CIL IV 2257); Mur-

tis felatris (Murtis is a blow-job babe, CIL IV 2292). Long overlooked

by scholarship as obscene recordings of sexual encounters, the 135 graf-

ti of the purpose-built brothel at Pompeii (VII 12 1820; CIL IV

217396 and 3101a; Add. 2156 and Add. 465) form a rich corpus

that illuminates daily interactions among clients and prostitutes in the

Roman world.

1

In this paper, I demonstrate through these grafti the

multiple ways in which male clients, individually and collectively, negoti-

ated male sexuality. Specically, I analyze how male clients both created

a hierarchy among themselves and solidied communal, normative mas-

culinity in opposition to nonnormative males and marginalized females.

I. Introduction

In the past fteen years, the grafti of the purpose-built brothel (here-

after referred to simply as the brothel) have entered the scholarly arena,

usually as part of works devoted to surveying or analyzing erotic grafti

at Pompeii. For example, some of the brothels sexual grafti were treated

by Antonio Varones Erotica pompeiana: Iscrizioni damore sui muri di Pompei

(1994; translated into English in 2002 as Erotica pompeiana: Love Inscrip-

tions on the Walls of Pompeii). Varone surveys a wide range of erotic and love

grafti from all over Pompeii, grouping them into motifs like Preghiere

damore and Larma damore. Through this typology, Varone draws out

common themes in a diverse body of material. Francesco Paolo Maulucci

Vivolos Pompei: I grafti damore (1995) presents samples of erotic grafti

from Pompeii, including some from the brothel, evoking how prolic this

type of grafti was. Taking a more analytic approach, Matthew Pancieras

dissertation, Sexual Practice and Invective in Martial and Pompeian

Inscriptions (2001), compares the different meanings and implications of

sexual practices in the corpus of Martials epigrams and Pompeiis grafti.

HELIOS, vol. 38 no. 1, 2011 Texas Tech University Press 59

These scholars have shed light on various features of erotic grafti at

Pompeii, but do not address how these grafti may have worked in each

specic locale or in concert with nonerotic grafti. Varones article,

Nella Pompei a luci rosse: Castrensis e lorganizzazione della prosti-

tuzione e dei suoi spazi (2005), however, adds a new perspective to the

study of the brothels grafti. Varone analyzes the status and sexual prac-

tices of the individuals in the brothel through close reading of its grafti,

demonstrating the potential gains of a contextual or locus-specic

approach.

2

In this article, I follow Varone in exploring the brothels graf-

ti together as a corpus, but ask different questions of the material.

Specically, I seek to illuminate the underlying structure of the corpuss

rhetoric. The grafti, I argue, are more than just records of sexual liaisons

or advertisements of the services of prostitutes; they represent an inter-

active discourse concerning masculinity. Clients and prostitutes could

and did add their thoughts to the corpus over time, which encouraged

multiple viewings. In addition, even illiterate viewers could be exposed to

the grafti through someone elses recitation.

3

It may not be surprising

that boasts and defamation are constituent elements of this dialogue; but

as I will show, the ways in which boasts and defamation are deployed

and against whom, and the implications this has for a rhetoric of mas-

culinity, reveal a discourse far different from the intra-elite masculine

invective seen in the poetry of Catullus and Martial.

II. Contextualizing the Brothel and its Grafti

At the intersection of the north-south Vicolo del Lupanare and the east-

west Vicolo del Balcone Pensile, located to the east of Pompeiis forum,

lies a modest, two-story structure.

4

The bottom oor contains ve small

rooms, each with a masonry bed, opening off a central hallway. Erotic

frescoes, most showing a male-female pair engaged in penile-vaginal

intercourse, line the register above the doorways in the hallway.

5

The

grafti, on the other hand, are found mostly (88%) within the small

cubicula. The terminus post quem of both the grafti and frescoes is 72 C.E.,

when the brothel was remodeled and a coin was pressed into the fresh

plaster of one of the rooms (La Rocca et al. 1981, 303). Nearly half the

grafti list only a name, about one-third are explicitly sexual, and the rest

are of nonsexual content or are indecipherable.

Of the approximately fty male names recorded, only a few present

more than an isolated cognomen (CIL IV 2240, Add. 215; CIL IV 2255;

CIL IV 2297, Add. 216; potentially CIL IV 2250, Add. 215; and CIL IV

60 HELIOS

R

d

d

2286). Many are of Greek origin, such as Phoebus (CIL IV 2182; CIL IV

2184, Add. 215; CIL IV 2194; CIL IV 2207; CIL IV 2248, Add. 215),

Hyginus (CIL IV 2249, Add. 215), and Hermeros (CIL IV 2249, Add.

215). The grafti also contain the titles of a perfumer (unguentarius: CIL

IV 2184, Add. 215), one or two soldiers (castrensis: CIL IV 2180; CIL IV

2290), and a guild-member (sodalis: CIL IV 2230).

6

Based on the types

of names and professions, many of the males at the brothel were most

likely of lower status (slaves, freedmen, and the free poor),

7

perhaps

reecting that others had the nancial means to satisfy their sexual urges

with their male and female slaves at home.

8

Many of the female names likewise suggest lower status. Some are of

Greek origin, such as Nica Creteissiane (Nica from Crete, CIL IV 2178a;

see also CIL IV 2278) and Panta (CIL IV 2178b). Others have an ironic

or descriptive character typical of slaves, such as Fortunata (CIL IV

2224; CIL IV 2259; CIL IV 2266; CIL IV 2275) and Victoria (CIL IV

2225; CIL IV 2226; CIL IV 2257).

9

Many of the brothels grafti rely on a vocabulary of sexually explicit

terms.

10

Futuere and binei`n most often describe male-female vaginal inter-

course, although they could encompass male-male anal sex as well. Pedi-

care and irrumare refer to the penetration of the anus and mouth,

respectively; the latter often involves an element of force and aggression.

Fellare and cunnum lingere describe oral sex performed respectively on a

male and female. As Amy Richlin (1992, 131, 645) explains, these

terms were considered primary obscenities by the standards of Roman

culture and can be found only in particular authors and genres.

In Latin literature, sexual obscenities were deployed most often in

invective that diminished the standing of the impugned party and sec-

ondarily in boasts that increased the standing of the subject. Indeed,

Richlin (1992) and David Wray (2001) have argued that violence and

aggression were often key elements in how sexual obscenities were

employed in Latin invective, and as is commonly known, their use relied

on the ways in which Romans conceptualized different sexual acts.

11

First, the moral implications of penetration differed for the penetrator

and the penetrated. The act of penetration was seen as (1) normative for

free males, (2) a masculine act, and (3) honorable. Being penetrated was

seen as (1) normative for females and slaves, (2) an effeminate or servile

act, and (3) shameful. That being penetrated was simultaneously nor-

mative and shameful for females is an important component of the

analysis in the latter half of this article. Sexual acts were also judged

according to the potential for them to pollute the participants. As such,

LEVIN- RICHARDSONFacilis hic futuit 61

performing oral sex was stigmatized as particularly reprehensible for the

pollution it was thought to bring upon the performer (Richlin 1992, 27,

69; Williams 2010, 21824). In fact, accusations of performing oral sex

were more powerful and defamatory than accusations of being the pene-

trated partner in anal sex (Williams 2010, 2212). In the brothels graf-

ti, the concepts of penetration and pollution are essential to how

masculinity was dened and contested. As will be shown in the next sec-

tions, the particular congurations of the brothels rhetoric of masculin-

ity differed in signicant ways from the rhetoric of masculinity seen in

Latin invective.

III. Male Rivalry

One way in which masculinity was negotiated in the brothel was through

boasts. Boasts take a wide range of forms, from laconic, one-word state-

ments to more elaborate variations. In addition, the role of sexual objects

in these boasts is minimal; rather, attention is often placed on the male

subjects and their penetrative masculinity. As I will show, these two

trends have interesting implications for how males engaged in rivalry

with other male patrons.

In what follows, I group boasts by formula (many of the grafti

adhere to patterns), beginning with basic formulas and continuing

through more complex ones. Within each formula, I present variations

starting with less inventive and moving to more inventive prose. The

hierarchy that I establish for these grafti is not absolute, and readers

may feel free to disagree with my assessment of one grafto as more or

less elaborate than another. Rather than tracing a straight line from the

simplest to the most ornate grafto, the image I would like to convey is

more like a scatter plot, with a large amount of individual variation that

nevertheless indicates a general spectrum from less to more sophisticated

boasts.

At the most basic end of the spectrum are the numerous solitary male

names inscribed into the brothels walls. These grafti leave the reader to

infer what brought the named person to the brothel. I would suggest that

these are, in an abbreviated form, a type of boast. Inscribing a name, in

essence, stands in for x was here, and in the context of the brothel,

gains the added implication of x fucked here. One grafto makes the

sexual nature of these names clear: in CIL IV 2181 (Add. 215), the name

Iarinus has been written together with an inscribed phallus, turning the

grafto into a visual representation of Iarinus hic futuit.

12

A sample of

62 HELIOS

R

d

d

these solitary male names includes: Neptunalis (CIL IV 2214), Swvvsas

(CIL IV 2234), Fructus (CIL IV 2244, CIL IV 2245a), L. Annius (CIL

IV 2255), Liberavli~ (CIL IV 2270), Ampliatus (CIL IV 2271), and

Romanus (CIL IV 2281). In total, between thirty and forty grafti pres-

ent a male name in isolation. Indeed, the inscription of just a name

may have been a way for less literate clients to take part in the brothels

discourse.

Some grafti include both a male name and a conjunction or adverb

that further implies sexual activity of some sort. So, for example, Victor /

cum (Victor with, CIL IV 2209) and the fragmentary Felix . . . / cum

(Felix . . . with, CIL IV 2232) imply that Victor and Felix were engaged

in sexual activities with another party. Another grafto claries one of

Felixs partners: Felix cum / Fortunata (Felix with Fortunata, CIL IV 2224).

A certain Marcus bested Victor and Felix by calling attention to the

wide variety of locations in which he presumably partook in sexual activ-

ities: Marcus Scepsini ubique . . . (Marcus of Scepsus everywhere, CIL IV

2201).

Other grafti state a male name and a sexually derived title. For exam-

ple, one grafto records Epaga/thus fututor / . . . (Epagathus the fucker . . . ,

CIL IV 2242).

13

For some writers, the title alone was insufcient, and an

adverb was added to differentiate good fututores from just regular futu-

tores: Phoebus / bonus futor (Phoebus is a good fukr, CIL IV 2248, Add.

215). In this particular case, the male subject is emphasized by a draw-

ing of a face (presumably meant to resemble Phoebus) next to the text.

14

Either this same client, or one of the same name, chose to differentiate

himself with a more specic title, writing: Phoebus pedico (Phoebus the

butt-fucker, CIL IV 2194, Add. 465).

15

Other grafti build from a base of I fucked. One, indeed, laconically

records futui (I fucked, CIL IV 2191). Variations on this formula include

the addition of objects, as in Felicla ego f (I f-ed Felicla, CIL IV 2199); if

there was any doubt about the sexual nature of this grafto, another graf-

to immediately below it states: Felicla ego hic futue (I focked Felicla here,

CIL IV 2200, Add. 215).

16

Of the same type is futui Mula hic (I fucked

Mula here, CIL IV 2203, Add. 215) and possibly Beronice / . . . / futuere

(To fuck Beronice . . . , CIL IV 2198, Add. 215).

17

In my reading, none of

these boasts names the (presumably male) subjects, thus reducing the

power of the grafti as proclamations of masculinity tied to a particular

client. If we remember, however, that reading was often conducted aloud

in antiquity, any reader of these grafti could become the appropriately

masculine subject.

LEVIN- RICHARDSONFacilis hic futuit 63

Another group of grafti plays with the prevalent formula x fucked

here. In its simplest incarnations, the verb is left out. For example, one

grafto states Sollemnes hic (Sollemnes here, CIL IV 2218a), and a simi-

lar one, Asbestus hic (Asbestus here, CIL IV 2222). Others include a

verb, such as Facilis hic futuit (Facilis fucked here, CIL IV 2178), Her-

meros hic futuit (Hermeros fucked here, CIL IV 2195), Mouai`o~ ejnqavde

beinei` (Mouaios fucks here, CIL IV 2216, Add. 215), and Posphorus / hic

futuit (Posphorus fucked here, CIL IV 2241).

18

Another grafto speci-

es the profession of the client and uses a superlative adverb: Phoebus

unguentarius / optume futuit (Phoebus the perfumer fucks best, CIL IV

2184, Add. 215). The superlative in this grafto differentiates Phoebus

from other clients, allowing him to claim a pinnacle of masculinity.

Adding to this formula, some grafti mention other participants. If

the names of the clients and their sexual partners are stated, a verb of

sexual congress is not always needed. So, for example, Hyginus cum Mes-

sio hic (Hyginus with Messius here, CIL IV 2249, Add. 215) implies sex-

ual contact.

19

The same goes for the fragmentary Rusatia . . hic / Coruenius

(Coruenius here [with] Rusatia, CIL IV 2262, Add. 465). Some grafti

include other participants and a verb. So, for example, there is Bellicus hic

futuit quendam (Bellicus fucked here a certain one, CIL IV 2247, Add.

215) and Victor cum Attine / hic fuit (Victor fukt here with Attine, CIL IV

2258).

20

Another grafto describes a group of male participants, and

even includes a date: XVII K Jul / Hermeros / cum Phile/tero et Caphi/so hic

futu/erunt (17 days before the Kalends of July, Hermeros with Phileteros

and Caphisus fucked here, CIL IV 2192, Add. 215). The addition of an

adverb in the following grafto, Synethus / Faustillam / futuit / obiquerite

(Synethus fucked Faustilla evirywhereyly, CIL IV 2288) allows Synethus

to stand out in comparison to the others and draws attention to his mas-

culine vigor in having sex in many locales. One grafto refers to the

name of the client and the prostitute, and to the (outrageous) cost of her

services: Arphocras hic cum Drauca / bene futuit denario (Arphocras fucked

well here with Drauca for a denarius, CIL IV 2193). The high cost might

even imply that Arphocras (= Harpocras) engaged in a sexual activity

other than relatively inexpensive penile-vaginal sex.

21

Other variations allowed patrons to display their masculinity by aunt-

ing the number of their sexual partners. One grafto reads, hic ego puellas

multas / futui (Here I fucked many girls, CIL IV 2175).

22

Placidus goes

one better, including his name and emphasizing his masculinity with the

arbitrariness of the object: Placidus hic futuit quem voluit (Placidus fucked

here whom he wished, CIL IV 2265), but his grafto lacks the humorous

64 HELIOS

R

d

d

punch of the following: Scordopordonicus hic bene / fuit quem voluit

(Garliquefarticus fukt well here whom he wished, CIL IV 2188).

23

Seven grafti follow the format x, you fuck well: Felix / bene futuis

(Felix, you fuck well, CIL IV 2176); Sollemnes / bene futues (Sollemnes,

you fock well, CIL IV 2185 and 2186); Vitalio / bene futues (Vitalio,

you fock well, CIL IV 2187); Victor bene futuis . . . (Victor, you fuck

well . . . , CIL IV 2218); December bene futuis (December, you fuck well,

CIL IV 2219); and Sunevrw~ kalo;~ binei`~ (Syneroos, you fuck good, CIL

IV 2253).

24

One grafto bests them all with a variation on a common

love grafto seen around Pompeii, quisquis amat valeat: Victor bene / valeas

qui bene futues (Victoryou who fock well, may you fare well!, CIL IV

2274, Add. 216; CIL IV 2260, Add. 216 has a slightly different word

order).

25

The use of the second and third person in the grafti lends an

authoritative quality to these statements. A reader might not believe

what a male patron says about himselfof course he says he is a good

fucker!but might nd the same statement more believable if it seemed

to come from a third party, especially if that source were a prostitute who

had rst-hand experience with the patron.

26

Finally, there are a few grafti that defy type, and these, too, range in

both inventiveness and degree of masculinity. Standing out both for its

unique formula and for the relatively rare reference to pedicare, one brief

grafto states, pedicare volo (I want to butt-fuck, CIL IV 2210). Another

unique example begins with a fairly standard rst line, but then adds a

humorous coda: hic ego cum veni futui / deinde redei domi (When I came

here, I fucked and then returned home, CIL IV 2246, Add. 465). Last

but not least, one boast, though much of the meaning remains uncertain,

mentions both the client and prostitute, uses an adverb, and seems to

refer to two sexual practices: Pdic Aplonia . . . / bene dat Nonius /

futere . . . (He butt-fucks Aplonia . . . gives it good, Nonius, fucking . . . ,

CIL IV 2197, Add. 215).

27

Male sexual boasts come in many forms. The variations on standard

formulaeHere I fucked many girls, Phoebus is a good fukr, Placidus

here fucked whom he wishedimply a competitive atmosphere of men

outdoing one another (literally and guratively). These boasts, then, cre-

ated a hierarchy among the male clients. Clients who boasted to have

fucked better or in more places, or with more women or boys than other

clients, laid claim to a more masculine sexuality. Furthermore, the type of

rivalry seen in the boasts did not rely on an oppositional structure of

masculine versus nonmasculine; this was not a zero-sum game. Phoebuss

and Placiduss claims to masculine sexuality were about which client was

LEVIN- RICHARDSONFacilis hic futuit 65

more masculinea friendly competition taking place in degrees rather

than absolutes.

In addition, the grafti demonstrate a wide range of options in (1)

naming the other partner in these sexual acts (12 grafti), (2) mention-

ing a general category of partner (puellas, for example, or quem voluit; 4

grafti), or (3) eliding mention of any other participant (25 grafti plus

3040 names).

28

The variable role of sexual objects ultimately will reveal

the underlying rhetoric of these boasts. Eve Kosofsky Sedgwicks (1985)

analysis of homosocial relationships through the rubric of erotic trian-

gles and David Wrays (2001) examination of gendered dynamics in

Catulluss love poetry can help illuminate the boasts structure.

Sedgwick argues that Victorian literature often used women symboli-

cally, with communication routed through them from one male partici-

pant to the other. In the Victorian context, the effect was that men

expressed homosocial desire for each other through heterosexual desire

directed towards a woman, ultimately using women to strengthen the

bonds between men. Wray (2001, 64112), building on Sedgwick, argues

that in the case of Catulluss poems, sexual acts with women were meant

to be proclamations of manhood to other men rather than declarations

of love for, or sexual acts with, a woman. Wray sees this especially in Cat-

ulluss Lesbia poems. Take Catullus 39, for example, where Catulluss

rival, Egnatius, is irting with Catulluss puella. Traditionally, as Wray

(2001, 83) puts it, this poem has been conscripted into service as a

(minor) moment in the tale of impassioned anguish that is the Lesbia

novel. Wrays reading, however, is that

the exchange or message . . . is homosocial: an affair between men,

between Catullus and the contubernales, and ultimately between Catul-

lus and Egnatius. What the Catullus of Poem 37 has lost is chiey exis-

timatio (face) and only secondarily the puella; his manhood has been

impugned, and it is for that reason that the loss of the puella smarts.

(2001, 87)

Thus, even poems of Catullus that appear on the surface to discuss the

narrators relationship with women (especially Lesbia) were overwhelm-

ingly about the performative display of manhood for other men. In these

poems, the woman serves as a coin of exchange passed between the

sender and receiver of the poem, both adult males . . . (2001, 723).

In the brothel, boasts were not addressed to a specic male rival, but

were proclamations meant to be read (aloud) by anyone and everyone.

66 HELIOS

R

d

d

In addition, this male rivalry was publicized and the audience/reader

invited to judge the competing claims to masculinity and even to partic-

ipate. Indeed, grafti without a named subject occur only in the rst per-

son; when read aloud, they would have turned the reader of the grafto

into the subject of the boast. This would have allowed any reader, by iter-

ating a rst-person boast, to take part in the competitive discourse on

masculinity that was carried out through the grafti. The coins of

exchange were the named prostitutes: Fortunata, Felicla, Beronice,

Rusatia, Faustilla, Drauca, and Aplonia. They need not necessarily be

female, either; male prostitutes were equally useful in this matter.

29

In

addition, it seems not to have mattered for boasts of masculinity that the

clients were paying prostitutes to have sex with them, that the coins of

exchange used in their boasts were bought with their own coin. The

underlying structure of grafti with named objects was a triangle in

which the male clients communicated their masculinity to other clients

through boasts of sexual acts with prostitutes (see gure 1a).

The rest of the boasts, howeverthose with a generalized object or no

expressed objectreveal the true nature of the structure to and rhetoric

behind these boasts. In boasts with a generalized direct object, the posi-

tion occupied by a specic, named prostitute was replaced with the cate-

gory or symbol of a prostitute. What had formerly been a triangle with a

prostitute as a coin of exchange between males becomes a triangle with

a weakened or symbolic third pole (see gure 1b). The boasts without

any objects go further, eliminating the sexual object altogether. With this

last category of boasts, the third pole has been weakened to the point of

being superuous; male clients simply engaged directly with each other.

The triangle, then, has become a horizontal line between males of

(roughly) equivalent status (see gure 1c).

The option to frame a masculine discourse without a triangular rela-

tionship, I argue, illuminates and contextualizes the entire corpus of

boasts. That is, even in the grafti that do name the boasts sexual object,

the object is already/nevertheless superuous, the rhetorical line between

the client and the prostitute dotted rather than solid. The ultimate effect

of the symbolic and superuous nature of the third pole of the triangle

was to reinforce the ideological primacy of the active male subjects and

their (competitive) connections with other male clients.

LEVIN- RICHARDSONFacilis hic futuit 67

IV. Us versus Them

The grafti discussed above reveal that male clients asserted their mas-

culinity vis--vis other male clients through increasingly elaborate, detailed,

or superlative boasts of penetrative sexual prowess. In the following sec-

tions, I will examine how the rhetoric of masculinity not only used boasts

to ne-tune a hierarchy among male clients, but also solidied commu-

nal masculine identity in opposition to two sets of Others: penetrated or

polluted males, and sexualized female prostitutes.

Penetrated or Polluted Males

While Latin literature abounds with invective slurs against males who

are penetrated and polluted (through oral sex), only a few grafti in the

brothel follow suit. One grafto says, ratio mi cum ponis / Batacare te pidicaro

(When you hand over the money, Batacarus, Ill butt-fock you, CIL IV

68 HELIOS

R

d

Figure 1: Structure of the Boasts

d

2254, Add. 216).

30

Batacarus, as the one handing over the money, must

have been a client at the brothel. The grafto-writer, then, used this graf-

to to portray Batacarus as a penetrated (and therefore emasculated)

male. A sketched phallus at the beginning of the grafto may have added

an element of violence and aggression, turning the grafto into a poten-

tial threat. In addition, prominence is given to the name of the impugned

partyBatacarus is the rst word of the second linerather than to the

name of the writer, who is anonymous. Indeed, the rst-person perspec-

tive of the grafto allowed every reader to become the masculine pene-

trator, and reinforced the superior status of the reader(s) vis--vis the

penetrated Batacarus.

31

The collective quality of this statement is an

important aspect of how masculinity was dened in the brothel.

Another emasculating, potentially violent grafto occurs in the frag-

mentary irrumo . . . (I face-fuck . . . , CIL IV 2277). Unfortunately, only a

few letters can be discerned in the latter part of the grafto, making

interpretation difcult. As irrumare often has an element of force behind

it, this grafto may have been a threat against a male or female prosti-

tute, or perhaps another male client. It is impossible to determine which

of the aforementioned scenarios might be correct, but if the grafto

named a male sexual object, it would effectively render that male both

penetrated and polluted. In addition, as in the previous grafto, the rst-

person verb form would have made any and all readers the subject of the

sentence. By voicing the grafto out loud, a reader would have afrmed

his virile masculinity.

The last instance of defamation, unlike the rst two, lacks an element

of aggression. The grafto claims, Froto plane / lingit cun/num (Froto clearly

licks cunt, CIL IV 2257).

32

This attack against Froto (= Fronto) calls

into question his status as a penetrating male; indeed, cunnum lingere was

often conceptualized as penetration of the mouth (Parker 1997, 512).

Furthermore, this grafto calls attention to Frontos polluted status and

implies that Fronto has no shame, since he has made no secret of his cun-

num lingere.

33

Unlike the boasts seen above, sexuality in these grafti is presented as

a zero-sum game in which the degradation of one male leads to the

responsive elevation in masculine sexuality of another. In these grafti,

however, it is not simply one male client who can benet at the expense

of Batacarus, Fronto, or whoever was the object of irrumare in CIL IV

2277. Rather, the lack of named accusers allows any, and potentially

every, male to rise in status compared to Batacarus and Fronto. Batacarus

and Fronto become the fall guys against whom the rest of the clients

LEVIN- RICHARDSONFacilis hic futuit 69

unite, and in the process, the rest of the clients reafrm their own nor-

mative male sexuality.

These defamatory grafti seem to take the shape of a triangle, with

a male writer communicating with a male reader through a male object

of derision (see gure 2a); however, the alignment of the writers and

readers interests against a mutual ideological Other draws these two

poles of the triangle together (see gure 2b). Moreover, the ways in

which this dialogue invited all male clients to participate through rst-

person boasts resulted in a structure amassing normative male clients at

the top of a now-vertical line, with Fronto, Batacarus, and any other pen-

etrated or polluted males at the bottom (see gure 2c). This structure in

many ways parallels Freuds A-B-C model of humor, which Richlin

(1992) has shown is appropriate to the context of Roman sexual humor.

In Freuds model, A tells a joke about B to C, thus drawing A and C

closer together (Richlin 1992, 601). Indeed, as Richlin explains, All

join together in laughing at B . . . The more pertinent a victim B isthe

greater the number of Cs who are normally vexed by such a Bthe

70 HELIOS

R

d

Figure 2: The Structure of Rhetoric against Penetrated or

Polluted Males

d

greater the audiences solidarity (1992, 61). In both models, the end

result is an increase in group cohesion. In the brothel, moreover, the

structure was reifying, reactive, and zero-sum: the boundaries around

normative and nonnormative male sexuality were strengthened by this

vertical and absolute polarity; to strengthen or solidify one pole was to

do the same, reactively, to the other; and nally, for normative males to

gain, nonnormative males had to lose.

Sexualized Female Prostitutes

Many of the rhetorical strategies employed by grafti concerning pene-

trated or polluted males are also found in grafti about female prosti-

tutes. The role of female prostitutes in the brothels grafti is not

restricted to appearances as the (symbolic) objects of male boasts, as

described above. A number of grafti conceptualize female prostitutes in

the role of sexual subjects as well. These grafti often draw attention to

the sexual acts in which the prostitute engages, or the prowess with

which she does so. These grafti may be seen as boasts written by the

prostitutes themselves, as compliments written by appreciative clients, or

as advertisements meant to drum up service.

34

Ultimately, we cannot

know who wrote the grafti and which, if any, of these possible interpre-

tations the writer intended (a good guess would be a combination of all

three). In this section I focus not on the intentions of the writers, but on

the impact of these grafti as a group for a rhetoric of masculinity.

The overwhelming effect of grafti in which females are the subjects

is to stress their sexuality.

35

As mentioned above, being penetrated was

seen as simultaneously normative for females and shameful. Likewise,

performing sexual acts was normative for prostitutes but could neverthe-

less incur societal shame; indeed, this latter facet of prostitutes sexuality

will be shown to be useful ideologically for solidifying masculinity.

A few of the grafti play with the idea of the female prostitute as pen-

etrated in the act of fututio. One grafto, for example, states, fututa sum

hic (I was fucked here, CIL IV 2217), calling attention to the female

prostitutes state of having been penetrated.

36

Another grafto reads

Movla foutou`tri~ (Mola the fucktress, CIL IV 2204).

37

This rare title

gains a sense of monumentality and (humorously) honorable status by

the large size of the letters and by the interpunct, which often divides

words in stone-cut inscriptions. Not only is Mola (presumably) pene-

trated in the act of fututio, as is the unnamed female of the previous graf-

to, but with the agentive tri~ ending, Mola appears to revel in her

sexualness. Another grafto perhaps serves as commentary, resolving any

LEVIN- RICHARDSONFacilis hic futuit 71

potential doubt that Mola is the penetrated partner in the sexual act, by

having a phallus penetrate her name: Mola (phallus) / . . . (CIL IV 2237,

Add. 215).

38

Like the foutou`tri~ grafto, another grafto suggests a cer-

tain promiscuity or pride that seems to go beyond the normal call of

duty: Ias cum Mag/no ubique (Ias with Magnus everywhere, CIL IV 2174)

stresses the frequency with which, or the multitude of locations in which,

Ias has had sexual relations with Magnus. Indeed, by presenting Iass

name rst, where one would expect the male clients name (see, e.g., CIL

IV 2209 and CIL IV 2224, discussed above), the grafto shifts the focus

away from Magnuss normative and acceptable sexual act towards Iass

excessive sexuality.

Most of the grafti with a female subject, however, tie her to the act

of fellatio. These grafti, then, highlight the prostitutes condition as

both penetrated and polluted. The barest incarnation, x sucks, can be

seen in the following description of Nice: Nice fellat (Nice sucks, CIL IV

2278).

39

The same formula was used in two identical grafti: Fortunata

fellat (Fortunata sucks, CIL IV 2259; CIL IV 2275). Fortunata seems to

reappear, with a shortened or misspelled name, in the grafto Fortuna sic

(Fortuna in this way, CIL IV 2266), which may be a clarication of the

grafto above it in another hand, vere / felas (You truly suk, CIL IV

2266).

40

Other grafti add details that make the portrayal more sexualized.

One grafto, Myrtale / Cassacos / fellas (Myrtale, you suck the Cassaci,

CIL IV 2268), suggests that a prostitute fellated an entire branch of

someones family tree!

41

Whether or not this grafto might also imply

that Myrtale fellated more than one person at a time, or in rapid succes-

sion, is left to the imagination of the (ancient and modern) reader.

Another grafto on the same wall, Murtale / Ccassi (Murtale [you suck?]

the Ccassi, CIL IV 2271) would probably have been read in light of the

rst, thus conveying a similarly sexualized portrayal. Another grafto

enhances the standard formula with an adverb: Murtis bene / felas (Mur-

tis, you suk well, CIL IV 2273, Add. 216); and another turns the prac-

tice of fellatio into a title: Murtis felatris (Murtis is a blow-job babe, CIL

IV 2292).

42

The grafti discussed in this section highlight the sexualness of

female prostitutes, in part by the prominent placement of the prosti-

tutes names and acts, and in part by the elision of sexual partners. In

addition to depicting prostitutes as hypersexual, these grafti present a

model of female sexuality that stands in marked contrast to the pudicitia

and verecundia of respectable femininity.

43

While male patrons could rein-

72 HELIOS

R

d

d

force their claims to proper masculinity in their boasts, this set of grafti

would only call attention to prostitutes non-adherence to societal norms.

In addition to prostitutes being, by denition, practitioners of disre-

spectable sexuality, these nonnormative depictions of femininity repli-

cated, reinforced, and permanently inscribed prostitutes marginalized

social standing.

Furthermore, as with the grafti concerning penetrated or polluted

males, the sexualized portrayal of female prostitutes was ideologically use-

ful in the brothels discourse on masculinity. On the surface, these graf-

ti seem to take the form of a horizontal linea communiqu between

grafto writer and prostitute (see gure 3a). This structure is clearest in

the second-person grafti, such as Murtis bene / felas (Murtis, you suk

well, CIL IV 2273). When employed in the service of a rhetoric of mas-

culinity, however, the structure takes the form of a vertical line with

female prostitutes at the bottom and normative male clients at the top,

regardless of the original intent or structure of the grafti (see gure 3b).

More precisely, it is the shame-inducing, communal hypersexuality of the

prostitutes that forms the bottom pole, rather than any individual pros-

titute. Communal masculine identity was solidied by the polarized dis-

tinction propagated by the grafti between socially respectable (i.e., male

client) and disrespectable (i.e., female prostitute) sexuality.

In sum, even when females were the subjects of the grafti, they nev-

ertheless lled a symbolic role in a male-dominated discourse. In the end,

female prostitutes were exploited not only sexually, but also ideologically.

LEVIN- RICHARDSONFacilis hic futuit 73

Figure 3: The Structure of Rhetoric against Sexualized

Female Prostitutes

V. Final Considerations

These grafti form the backbone of an interactive discourse in which

masculinity was proclaimed and contested. Boasts about male sexuality

functioned in an atmosphere of rivalry to establish a relative hierarchy

among (normative) male clients, while an oppositional attitude towards

nonnormative males and sexualized females consolidated communal

masculinity and elevated the male clients, through their normativity, to

a superior status. Boasts comprise the majority of this discourse (41 graf-

ti, plus 3040 names), contrasting with the preponderance of invective

in the discourse of masculinity seen in Latin literature, and illustrat-

ing the specicity of how masculinity was negotiated in the brothel.

Although the male clients were low-status and consequently had little to

lose in terms of political, economic, or social power, they nevertheless

used the brothel and its grafti as a competitive arena.

44

Works Cited

Adams, J. N. 1982. The Latin Sexual Vocabulary. Baltimore.

Bain, D. 1991. Six Greek Verbs of Sexual Congress (binw`, kinw`, pugivzw, lhkw`, oi[fw,

laikavzw). CQ 41: 5177.

Baird, J., and C. Taylor, eds. 2010. Ancient Grafti in Context. London.

Beard, M., et al. 1991. Literacy in the Roman World. Journal of Roman Archaeology Sup-

plementary Series, 3. Ann Arbor.

Beneel, R. R. 2010a. Dialogues of Ancient Grafti in the House of Maius Castricius

in Pompeii. AJA 114: 59101.

. 2010b. Dialogues of Grafti in the House of the Four Styles at Pompeii (Casa

dei Quattro Stili, I.8.17, 11). In Baird and Taylor 2010, 2048.

Bradley, K. R. 1984. Slaves and Masters in the Roman Empire: A Study in Social Control.

Brussels.

Bragantini, I. 1997. VII 12, 1820: Lupanare. In G. P. Carratelli, ed., Pompei: pitture

e mosaici. Volume 7. Rome. 52039.

Cantarella, E. 1998. Pompei: I volti di amore. Milan.

Clarke, J. R. 1998. Looking at Lovemaking: Constructions of Sexuality in Roman Art

100 B.C.A.D. 250. Berkeley.

. 2003. Roman Sex: 100 B.C. to A.D. 250. New York.

Edwards, C. 1993. The Politics of Immorality in Ancient Rome. Cambridge.

Flemming, R. 1999. Quae Corpore Quaestum Facit: The Sexual Economy of Female

Prostitution in the Roman Empire. JRS 89: 3861.

Franklin, J. L., Jr. 1986. Games and a Lupanar: Prosopography of a Neighborhood in

Ancient Pompeii. CJ 81: 31928.

. 1987. Pantomimists at Pompeii: Actius Anicetus and His Troupe. AJP 108:

95107.

Hallett, J., and M. Skinner, eds. 1997. Roman Sexualities. Princeton.

74 HELIOS

R

d

d

Harris, W. V. 1989. Ancient Literacy. Cambridge, MA.

Henderson, J. 1991. The Maculate Muse: Obscene Language in Attic Comedy. Second edi-

tion. New York.

Johnson, W. A., and H. N. Parker, eds. 2009. Ancient Literacies: The Culture of Reading in

Greece and Rome. New York.

Kamen, D., and S. Levin-Richardson. Forthcoming. Lusty Ladies in the Roman Imag-

inary. In R. Blondell and K. Ormand, eds., New Essays in Ancient Sexuality.

Columbus.

Kaster, R. A. 2005. Emotion, Restraint, and Community in Ancient Rome. New York.

La Rocca, E., et al. 1981. Guida archeologica di Pompei. Milan.

Langlands, R. 1996. Sexual Morality in Ancient Rome. Cambridge.

Levin-Richardson, S. 2009. Roman Provocations: Interactions with Decorated Spaces

in Early Imperial Rome and Pompeii. Ph.D. dissertation, Stanford University.

. Forthcoming. Female Uses of Obscenity in Pompeian Grafti. In D. Dutsch

and A. Suter, eds., Ancient Obscenities.

Maulucci Vivolo, F. P. 1995. Pompei: I grafti damore. Foggia.

McGinn, T. 2002. Pompeian Brothels and Social History. In Pompeian Brothels, Pom-

peiis Ancient History, Mirrors and Mysteries, Art and Nature at Oplontis, & the Hercu-

laneum Basilica. Journal of Roman Archaeology Supplementary Series, 47. Ann

Arbor. 746.

Milnor, K. 2009. Literary Literacy in Roman Pompeii: The Case of Vergils Aeneid. In

Johnson and Parker 2009, 288319.

Myerowitz, M. 1992. The Domestication of Desire: Ovids Parva Tabella and the The-

ater of Love. In A. Richlin, ed., Pornography and Representation in Greece and Rome.

New York. 13157.

Panciera, M. 2001. Sexual Practice and Invective in Martial and Pompeian Inscrip-

tions. Ph.D. dissertation, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Parker, H. N. 1997. The Teratogenic Grid. In Hallett and Skinner 1997, 4765.

. 2007. Free Women and Male Slaves, or Mandingo Meets the Roman

Empire. In A. Serghidou, ed., Fear of SlavesFear of Enslavement in the Ancient

Mediterranean. Franche-Comt. 28198.

Richlin, A. 1992. The Garden of Priapus: Sexuality and Aggression in Roman Humor.

Revised edition. New York.

Sedgwick, E. 1985. Between Men: English Literature and Male Homosocial Desire. New York.

Solin, H. 2003. Die griechischen Personennamen in Rom: Ein Namenbuch. Second edition.

Berlin.

Vnnen, V. 1959. Le latin vulgaire des incriptions pompiennes. Berlin.

Varone, A. 1994. Erotica pompeiana: Iscrizioni damore sui muri di Pompei. Rome.

. 2001. Eroticism in Pompeii. Los Angeles.

. 2002. Erotica pompeiana: Love Inscriptions on the Walls of Pompeii. English transla-

tion by R. P. Berg. Rome. (Originally published as Erotica Pompeiana: Iscrizioni

damore sui muri di Pompei [Rome 1994])

. 2005. Nella Pompei a luci rosse: Castrensis e lorganizzazione della prosti-

tuzione e dei suoi spazi. Rivista di studi pompeiani 16: 93109.

Wallace-Hadrill, A. 1995. Public Honour and Private Shame: The Urban Texture of

Pompeii. In T. J. Cornell and K. Lomas, eds., Urban Society in Roman Italy. Lon-

don. 3962.

LEVIN- RICHARDSONFacilis hic futuit 75

Walters, J. 1997. Invading the Roman Body: Manliness and Impenetrability in

Roman Thought. In Hallett and Skinner 1997, 2943.

Williams, C. 2010. Roman Homosexuality. Second edition. New York.

Wray, D. 2001. Catullus and the Poetics of Roman Manhood. Cambridge.

Notes

1. For the appellation purpose-built, and other names for this structure, see

McGinn 2002, 13. I count grafti co-listed under the same number (e.g., CIL IV

2178a and 2178b) separately, which may result in a slightly higher total number of

grafti than other scholars counts.

2. For other contextual approaches to grafti, see, e.g., Franklin 1986, Milnor

2009, Baird and Taylor 2010, Beneel 2010a and 2010b.

3. For ancient literacy, see, e.g., Harris 1989, Beard et al. 1991, and Johnson and

Parker 2009; for reading aloud in antiquity, Harris 1989, 226.

4. Since the upper story has none of Wallace-Hadrills (1995) criteria of an ancient

brothel (masonry beds, erotic frescoes, and erotic grafti; see also McGinn 2002), I

will not address it in this article. I would like to thank the Soprintendenza Archeolo-

gica di Pompei for permission to enter and photograph the upper story. For documen-

tation of the upper story, see Bragantini 1997, plates 3243.

5. For scholarship on the brothels frescoes, see Myerowitz 1992, Clarke 1998,

Varone 2001, Clarke 2003, and Levin-Richardson 2009.

6. For the Greek names, see also Solin 2003, 55, 3036, 7346. For analysis of

these identities, see Varone 2005. For other interpretations of castrensis in CIL IV

2180, see Franklin 1987, 99100 and Varone 2005.

7. Ascertaining status from names is not unproblematic; see, e.g., Beneel 2010b, 26.

8. See also Clarke 1998, 199. It is unclear whether some of the males were prosti-

tutes rather than clients (see Cantarella 1998, 1024, 1135). The grafti might not

exactly mirror the workers and patrons of the brothel; certain groups of individuals

(perhaps higher-status males, or females) might not have wanted to record their visit

to the brothel, and others may have been illiterate. For brothel patrons in Latin litera-

ture, see Flemming 1999, 45. For sex between masters and slaves, see Bradley 1984,

1158; Walters 1997, 39; and Varone 2001, 1558. For a literary treatment of sex

between slaves and mistresses, see Edwards 1993, 4953 and Parker 2007.

9. For the overlap of prostitutes names in the brothel and other locales, see

Cantarella 1998, 912 and Varone 2005.

10. For Greek and Latin sexual obscenities, see Adams 1982, Bain 1991, Hender-

son 1991, Richlin 1992, and Panciera 2001.

11. For a summary of Roman sexual mores, see Parker 1997.

12. Zangemeister (at CIL IV 2181, Add. 215), however, voiced uncertainty about

whether the gure is indeed a phallus.

13. The third line of the grafto is unclear.

14. See Zangemeister at CIL IV 2248.

15. The rarity of a name with a rst-person verb leads me to take pedico as a noun

rather than a verb.

76 HELIOS

R

d

d

16. The lack of nal m need not indicate the nominative case: Vnnen

1959, 73.

17. CIL IV 2203 lists a fragmentary second line, but I am not convinced that it is

in the same hand as the rst line of the grafto. The second line of CIL IV 2198 is

indecipherable, being variously transcribed as //abenda by Zangemeister and valentes by

Fiorelli (both at CIL IV 2198).

18. For more on Mou<s>ai`o~, see Franklin 1986, 327.

19. One could categorize these grafti also as elaborations of the names discussed

above. Whether these grafti indicate that the named persons had sexual activities

with each other, or with a third party, remains unclear; see the discussion in Panciera

2001, 21720.

20. CIL IV 2247 contains a second line, but I agree with Zangemeister (at CIL IV

2247) that it has been composed in another hand.

21. This grafto might function as invective, if we take it in light of Martials epi-

grams (see especially 9.4) that associate a high cost for sexual service with marginal

sexual acts (being penetrated or performing oral sex; see Panciera 2001, 468).

22. This grafto could also fall under the formula involving boasts of futui.

23. Scordopordonicus: see Zangemeister at CIL IV 2188. Adams (1982, 121) suggests

that these examples of quem might be symptomatic of the encroachment of the mas-

culine forms of the relative on the feminine. Given that futuere could refer to male-

male sex, and that the penetrative party in homoerotic as well as heteroerotic sex did

not suffer any social disapproval, I do not nd his explanation convincing. It seems

equally plausible, if not more so, that these grafti reected the arbitrariness of the

object of the actthat is, Scordopordonicus and Placidus were properly masculine

whether they had sex with females or males. See also CIL IV 2247.

24. In the latter part of CIL IV 2218, there are a few letters after futuis that are

indecipherable. In CIL IV 2253, kalov~ may agree with the proper name, although

given the fairly consistent structure of name-adverb-verb in the corpus, I would argue

that the author mistakenly wrote omicron in place of the adverbial omega. Bain (1991,

56) likewise emended kalov~ to kalw`~. For more on Syneros, see CIL IV 2252 and

Franklin 1986, 3256.

25. For quisquis amat valeat, see, e.g., CIL IV 4091; Varone 1994, 60 (= Varone

2002, 62); and Milnor 2009, 3012.

26. This may suggest that other parties, including female prostitutes, had an active

role in writing praise for male clients. For potential female authorship of grafti, see,

e.g., Varone 1994, 81 (= Varone 2002, 83) and Levin-Richardson, Forthcoming. How-

ever, male patrons were probably aware of the added credibility gained by second- and

third-person testimonials, and may have written such grafti themselves. The question

of authorship remains unanswerable, but given that male clients had a greater stake in

their reputation than did prostitutes, it seems more likely that the male clients were

the authors.

27. The end of the rst line has been rendered unreadable by damage, while the

last line has not been deciphered satisfactorily.

28. Boasts with named other participants (all in CIL IV): 2192, 2193, 2197, 2198,

2199, 2200, 2203, 2224, 2249, 2258, 2262, 2288. Boasts with a general object (all in

CIL IV): 2175, 2188, 2247, 2265. Boasts with no direct object (not including isolated

LEVIN- RICHARDSONFacilis hic futuit 77

names) (all in CIL IV): 2176, 2178, 2184, 2185, 2186, 2187, 2191, 2194, 2195,

2201, 2209, 2210, 2216, 2218, 2218a, 2219, 2222, 2232, 2241, 2242, 2246, 2248,

2253, 2260, 2274.

29. Grafti stating that Scordopordonicus or Placidus could fuck quem voluit, or

that Bellicus could fuck quendam, suggest that male prostitutes were available and

acceptable sexual objects. However, all of the grafti with a named potential male

object use the formula x with y, as in Hyginus cum Messio hic (CIL IV 2249) rather

than an accusative direct object. Few grafti use this formula to refer to a female (e.g.,

Felix cum Fortunata: CIL IV 2224).

30. I agree with Fiorelli (at CIL IV 2254) that the third line seems to have been

written in a different hand, and thus I have not included it above. I have taken pidicaro

as a misspelling of pedicabo, although it could also be the syncopated future perfect.

31. The hierarchy between the grafto reader and Batacarus is complicated, how-

ever, by the readers seeming status as someone who has accepted money for sex (as

one of the referees has brought to my attention).

32. For other examples, see CIL IV, s.v. cunnum lingere.

33. For the added shame of committing transgressive acts in public, see, e.g., Cic-

ero, Cael. 47 and Martial 1.34.

34. For female uses of obscenity in grafti, see Levin-Richardson, Forthcoming.

35. The two exceptions are CIL IV 2202: Restituta bellis horibus (Restituta with

the pretty face; cf. Add. 465, however) and Victoria invicta hic (Victoria was uncon-

quered here, CIL IV 2226).

36. For fututa, see also CIL IV 2006 and CIL IV 8897.

37. For another fututrix, see CIL IV 4196.

38. The meaning of the latter part of the grafto is unclear. For female sexual

agents in the Roman imaginary, see Kamen and Levin-Richardson, Forthcoming.

39. Zangemeister (at CIL IV 2278) reports that the rst four of ve letters of the

grafto before Nice have been erased.

40. Another possible reading of the grafto Fortuna sic is Fortuna likewise. I fol-

low Fiorellis reading of the rst line of the latter grafto as vere (at CIL IV 2266).

41. Cassacos may refer to several men with the name Cassacus (we unfortunately do

not know who the Cassaci were).

42. The more common form of the name is Myrtis (Solin 2003, 117880). For

other fellatrices, see CIL IV 1388, CIL IV 1389, CIL IV 1510, CIL IV 4192, and CIL

IV 9228.

43. For the role of these virtues in elite femininity, see, e.g., Kaster 2005, 1365

and Langlands 2006.

44. I would like to thank Deborah Kamen and Rebecca Beneel for commenting on

drafts of this article, as well as the two anonymous referees for their feedback. A ver-

sion of this paper was given at the University of Leicesters 2008 conference, Ancient

Grafti in Context. I have chosen not to correct any orthographic or grammatical

mistakes made in the grafti, and translate accordingly. All translations are my own

unless otherwise noted.

78 HELIOS

R

d

Você também pode gostar

- The 10 000 BlowjobDocumento93 páginasThe 10 000 BlowjobEdmond100% (4)

- Fuck FoucaultDocumento65 páginasFuck Foucaultlidiaglass100% (1)

- Pop-Enlightenment Sexual AnthropologyDocumento33 páginasPop-Enlightenment Sexual AnthropologyfantasmaAinda não há avaliações

- Gnosis Undomesticated Archon-Seduction D PDFDocumento25 páginasGnosis Undomesticated Archon-Seduction D PDFÁtila100% (1)

- Fetish in LiteratureDocumento12 páginasFetish in LiteratureMarcos Lampert VarnieriAinda não há avaliações

- Introduction To The Prostitute's BodyDocumento17 páginasIntroduction To The Prostitute's BodyPickering and Chatto100% (1)

- De Lauretis Teresa Queer Theory Lesbian and Gay Sexualities IntroductionDocumento17 páginasDe Lauretis Teresa Queer Theory Lesbian and Gay Sexualities IntroductionSusanisima Vargas-Glam93% (15)

- BoethiusDocumento157 páginasBoethiusBarıs Basaran100% (2)

- Rome: Sex & Freedom: Peter Brown December 19, 2013 IssueDocumento9 páginasRome: Sex & Freedom: Peter Brown December 19, 2013 IssueVz JrgeAinda não há avaliações

- Homoeroticism - CaragounisDocumento126 páginasHomoeroticism - CaragounisAnonymous mNo2N3Ainda não há avaliações

- Lesbian and Gay Historical FictionsDocumento296 páginasLesbian and Gay Historical FictionsTheodore StephenAinda não há avaliações

- NG Lap Seng ReportDocumento68 páginasNG Lap Seng ReportInvestigative Reporting Program100% (4)

- Women CrossDressing - IntroductionDocumento34 páginasWomen CrossDressing - Introductionxristina740% (1)

- Homosexuality in Egypt PDFDocumento21 páginasHomosexuality in Egypt PDFIvan Rodríguez LópezAinda não há avaliações

- NHH 16 Real Men and Mincing Queans - Homosexuality in Ancient RomeDocumento10 páginasNHH 16 Real Men and Mincing Queans - Homosexuality in Ancient Romeeng.tahasuliman100% (2)

- David Carr, Gender and The Shaping of Desire in The Song of Songs and Its InterpretationDocumento17 páginasDavid Carr, Gender and The Shaping of Desire in The Song of Songs and Its InterpretationJonathanAinda não há avaliações

- Cabaret 1 PDFDocumento26 páginasCabaret 1 PDFMariana Ortiz Martinezortiz MarianaAinda não há avaliações

- Children Welfare Code of Davao City - ApprovedDocumento27 páginasChildren Welfare Code of Davao City - ApprovedALLAN H. BALUCAN67% (3)

- People v. Sayo y Reyes, G.R. No. 227704, (April 10, 2019)Documento25 páginasPeople v. Sayo y Reyes, G.R. No. 227704, (April 10, 2019)Olga Pleños ManingoAinda não há avaliações

- Street Corner Secrets by Svati ShahDocumento71 páginasStreet Corner Secrets by Svati ShahDuke University Press100% (2)

- Projdoc Work PlanDocumento24 páginasProjdoc Work PlanDenis Felix DrotiAinda não há avaliações

- 100 Countries and Their Prostitution PoliciesDocumento44 páginas100 Countries and Their Prostitution PoliciesMuhammad A. A. MamunAinda não há avaliações

- Calos Graffiti and Infames at Pompeii.Documento10 páginasCalos Graffiti and Infames at Pompeii.jfmartos2050Ainda não há avaliações

- GlobalizationDocumento11 páginasGlobalizationvic100% (1)

- Writers on... Sex: A Book of Quotes, Poems and Literary ReflectionsNo EverandWriters on... Sex: A Book of Quotes, Poems and Literary ReflectionsAinda não há avaliações

- 07 Chapter 2 PDFDocumento43 páginas07 Chapter 2 PDFmanilaAinda não há avaliações

- Ways of Being Roman: Discourses of Identity in the Roman WestNo EverandWays of Being Roman: Discourses of Identity in the Roman WestAinda não há avaliações

- The Myth of The Heterosexual: Anthropology and Sexuality For ClassicistsDocumento51 páginasThe Myth of The Heterosexual: Anthropology and Sexuality For ClassicistsVelveretAinda não há avaliações

- The Dancing Lares and the Serpent in the Garden: Religion at the Roman Street CornerNo EverandThe Dancing Lares and the Serpent in the Garden: Religion at the Roman Street CornerAinda não há avaliações

- Levin Richardson - Graffiti and Masculinity in Pompeii PDFDocumento21 páginasLevin Richardson - Graffiti and Masculinity in Pompeii PDFPaqui Fornieles MedinaAinda não há avaliações

- Paiderastia PDFDocumento314 páginasPaiderastia PDFBrahim MegherbiAinda não há avaliações

- Facilis Hic Futuit Graffiti and MasculinDocumento20 páginasFacilis Hic Futuit Graffiti and MasculinAndré SimõesAinda não há avaliações

- A New Entity in The History of Sexuality: The Respectable Same-Sex CoupleDocumento9 páginasA New Entity in The History of Sexuality: The Respectable Same-Sex CoupleAmari SanfordAinda não há avaliações

- Vergil and Founding Violence: Michèle LowrieDocumento32 páginasVergil and Founding Violence: Michèle LowrieUrsusAinda não há avaliações

- Eunucos en AntigDocumento18 páginasEunucos en AntigMaria Ruiz SánchezAinda não há avaliações

- A Very British Carnival: Women, Sex and Transgression in Fiesta MagazineDocumento17 páginasA Very British Carnival: Women, Sex and Transgression in Fiesta MagazineRam SeyAinda não há avaliações

- 8 ST Louis ULJ279Documento81 páginas8 ST Louis ULJ279Fer Gom BAinda não há avaliações

- Family Nomenclature and Same-Name Divinities in Roman Religion and MythologyDocumento17 páginasFamily Nomenclature and Same-Name Divinities in Roman Religion and MythologyhAinda não há avaliações

- An Atypical Affair Alexander The Great HephaistionDocumento16 páginasAn Atypical Affair Alexander The Great HephaistionNagy BernadettAinda não há avaliações

- Book Edcoll 9789004196131 B9789004196131 005-PreviewDocumento2 páginasBook Edcoll 9789004196131 B9789004196131 005-PreviewJohan FernándezAinda não há avaliações

- Burning (1991) and The Laundrette in My Beautiful Laundrette (1985) Act As IdentityDocumento11 páginasBurning (1991) and The Laundrette in My Beautiful Laundrette (1985) Act As IdentityVarsha GuptaAinda não há avaliações

- Leahy WalcottArticle FinalPublishedVersion May2015 PDFDocumento22 páginasLeahy WalcottArticle FinalPublishedVersion May2015 PDFRimi ghoshAinda não há avaliações

- Leahy WalcottArticle FinalPublishedVersion May2015 PDFDocumento22 páginasLeahy WalcottArticle FinalPublishedVersion May2015 PDFRimi ghoshAinda não há avaliações

- This Content Downloaded From 138.51.92.33 On Thu, 02 Dec 2021 00:23:35 UTCDocumento54 páginasThis Content Downloaded From 138.51.92.33 On Thu, 02 Dec 2021 00:23:35 UTCalexfelipebAinda não há avaliações

- Dean Gender and Insult BolognaDocumento16 páginasDean Gender and Insult BolognaPuchoAinda não há avaliações

- Sinful Wives and Queens ALFIEDocumento36 páginasSinful Wives and Queens ALFIEjordi.martin.alonsoAinda não há avaliações

- The Complicated Terrain of Latin American Homosexuality: Mar Tin NesvigDocumento41 páginasThe Complicated Terrain of Latin American Homosexuality: Mar Tin NesvigFrancisca Monsalve C.Ainda não há avaliações

- Meyer FortesDocumento22 páginasMeyer Fortesmister.de.bancada01Ainda não há avaliações

- Representations and Realities Cemeterie PDFDocumento33 páginasRepresentations and Realities Cemeterie PDFEm RAinda não há avaliações

- The Invention of PornographyDocumento3 páginasThe Invention of PornographyHidayat PurnamaAinda não há avaliações

- Reviewsicritique Litteraire: The Bourgeois Experience: Victoria To FreudDocumento3 páginasReviewsicritique Litteraire: The Bourgeois Experience: Victoria To FreudmfernandasandovalAinda não há avaliações

- COLD WAR FEMME Lesbian Visibility in Joseph L. Mankiewicz's All 2023-08-17 04-07-16-1Documento23 páginasCOLD WAR FEMME Lesbian Visibility in Joseph L. Mankiewicz's All 2023-08-17 04-07-16-1DFW 2002Ainda não há avaliações

- Valerie Traub EssayDocumento13 páginasValerie Traub EssayArunava MisraAinda não há avaliações

- The Social History of Western Sexuality: General Introduction To Theories of Gender and SexDocumento17 páginasThe Social History of Western Sexuality: General Introduction To Theories of Gender and SexmatyasorsiAinda não há avaliações

- Wolfson, Nicholas. Hate Speech, Sex Speech Free SpeechDocumento21 páginasWolfson, Nicholas. Hate Speech, Sex Speech Free SpeechTheoAinda não há avaliações

- Why Were The Vestals Virgins or The Chastity of Women and The Safety of The RomanState by Holt N. ParkerDocumento40 páginasWhy Were The Vestals Virgins or The Chastity of Women and The Safety of The RomanState by Holt N. ParkerAtmavidya1008Ainda não há avaliações

- Dwayne Meisner - Livy and The BacchanaliaDocumento41 páginasDwayne Meisner - Livy and The BacchanaliaedinjuveAinda não há avaliações

- ACE - CAT - Practice Module - 1Documento64 páginasACE - CAT - Practice Module - 1umangabhi13Ainda não há avaliações

- Anguissola JournalRomanStudies 2016Documento3 páginasAnguissola JournalRomanStudies 2016elisabethtanghe321Ainda não há avaliações

- A Comparison of Ancient Roman and Greek Norms Regarding SexualityDocumento28 páginasA Comparison of Ancient Roman and Greek Norms Regarding SexualityParthaSahaAinda não há avaliações

- Couperin - MoralisteDocumento33 páginasCouperin - MoralisteRadoslavAinda não há avaliações

- Practice Module - For CATDocumento60 páginasPractice Module - For CATcheemsji14Ainda não há avaliações

- What Could Marcus Aurelius Feel For FrontoDocumento7 páginasWhat Could Marcus Aurelius Feel For Frontoaik34036Ainda não há avaliações

- Hunter HenryIVElizabethan 1954Documento14 páginasHunter HenryIVElizabethan 1954George ConcannonAinda não há avaliações

- Sexuality in The History of "Westernesotericism, Leiden and Boston: Brill 2008Documento5 páginasSexuality in The History of "Westernesotericism, Leiden and Boston: Brill 2008Josip Solomon JanešAinda não há avaliações

- Incontinentia Licentia Et LibidoDocumento8 páginasIncontinentia Licentia Et LibidodsagemaverickAinda não há avaliações

- Cambridge University Press Cambridge Opera JournalDocumento22 páginasCambridge University Press Cambridge Opera JournalsummerludlowAinda não há avaliações

- Lyric Audibility in PublicDocumento15 páginasLyric Audibility in PublicTom AllenAinda não há avaliações

- Begun and Held in Metro Manila, On Monday, The Twenty-Third Day of July, Two Thousand TwelveDocumento11 páginasBegun and Held in Metro Manila, On Monday, The Twenty-Third Day of July, Two Thousand TwelveArellano AureAinda não há avaliações

- United States District Court: For The Western District of New YorkDocumento20 páginasUnited States District Court: For The Western District of New YorkWGRZ-TVAinda não há avaliações

- Research Paper Rough DraftDocumento4 páginasResearch Paper Rough DraftadityaAinda não há avaliações

- Arikel IJICC1 - Halal Sex TourismDocumento14 páginasArikel IJICC1 - Halal Sex TourismLoka HendraAinda não há avaliações

- Prathana PatelDocumento14 páginasPrathana PatelRiya TayalAinda não há avaliações

- Red Light District - Official Documentary TranscriptionDocumento50 páginasRed Light District - Official Documentary TranscriptionJanice DollosaAinda não há avaliações

- Riminology Roject: T: Legalizing ProstitutionDocumento9 páginasRiminology Roject: T: Legalizing ProstitutionAbhishekKuleshAinda não há avaliações

- Just A John?Documento5 páginasJust A John?HJAinda não há avaliações

- Sita and The Prostitute - On The Indian Prostitution StigmaDocumento27 páginasSita and The Prostitute - On The Indian Prostitution StigmaJocelyn BellAinda não há avaliações

- La DominicanaDocumento18 páginasLa DominicanaRudraniAinda não há avaliações

- Escorts in Mahipalpur - 9718077047Documento6 páginasEscorts in Mahipalpur - 9718077047Massage Massage centreAinda não há avaliações

- Cyber Hate CrimesDocumento22 páginasCyber Hate CrimesRandom ShitAinda não há avaliações

- 22 2 PhoenixDocumento23 páginas22 2 PhoenixPete DoughtonAinda não há avaliações

- CCCH9013 Course Outline 2019Documento15 páginasCCCH9013 Course Outline 2019Chou Zen HangAinda não há avaliações

- FFJF Annual Report 2017 - Final PDFDocumento21 páginasFFJF Annual Report 2017 - Final PDFAtifAinda não há avaliações

- A Constellation of Stigmas Intersectional Stigma Management and The Professional Dominatrix-2Documento22 páginasA Constellation of Stigmas Intersectional Stigma Management and The Professional Dominatrix-2Lucia MarinelliAinda não há avaliações

- Gender and SocietyDocumento6 páginasGender and SocietyMichie TolentinoAinda não há avaliações

- Immoral Traffic Prevention ActDocumento3 páginasImmoral Traffic Prevention ActManas Ranjan SamantarayAinda não há avaliações

- List of Red-Light Districts: Jump To Navigation Jump To SearchDocumento32 páginasList of Red-Light Districts: Jump To Navigation Jump To SearchsudeepomAinda não há avaliações

- UntitledDocumento15 páginasUntitledapi-219628328Ainda não há avaliações

- Trafficking of Women in Nepal and Their Vulnerabilities: Clark Digital CommonsDocumento47 páginasTrafficking of Women in Nepal and Their Vulnerabilities: Clark Digital CommonsKristin MonavikAinda não há avaliações