Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

A Review On The Regulation of Limited Liability

Enviado por

sotszngai0 notas0% acharam este documento útil (0 voto)

386 visualizações10 páginasThe document discusses the regulation of limited liability in Hong Kong law. It provides an overview of the current laws, including how the common law and statutes address piercing the corporate veil in certain situations like fraud. It also outlines problems with the status quo, such as a lack of coherent principles in court decisions on piercing the corporate veil. The document concludes by suggesting reforms are needed to address shortcomings in this area of law.

Descrição original:

Regulation of limited liability is a controversial subject. In the rest of this paper, I will outline the current laws in Hong Kong on this subject, followed by a discussion of the problems of the status quo and recommendations to address the shortcomings. I will then conclude with a suggestion for the necessary reforms.

Título original

A Review on the Regulation of Limited Liability

Direitos autorais

© © All Rights Reserved

Formatos disponíveis

PDF, TXT ou leia online no Scribd

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoThe document discusses the regulation of limited liability in Hong Kong law. It provides an overview of the current laws, including how the common law and statutes address piercing the corporate veil in certain situations like fraud. It also outlines problems with the status quo, such as a lack of coherent principles in court decisions on piercing the corporate veil. The document concludes by suggesting reforms are needed to address shortcomings in this area of law.

Direitos autorais:

© All Rights Reserved

Formatos disponíveis

Baixe no formato PDF, TXT ou leia online no Scribd

0 notas0% acharam este documento útil (0 voto)

386 visualizações10 páginasA Review On The Regulation of Limited Liability

Enviado por

sotszngaiThe document discusses the regulation of limited liability in Hong Kong law. It provides an overview of the current laws, including how the common law and statutes address piercing the corporate veil in certain situations like fraud. It also outlines problems with the status quo, such as a lack of coherent principles in court decisions on piercing the corporate veil. The document concludes by suggesting reforms are needed to address shortcomings in this area of law.

Direitos autorais:

© All Rights Reserved

Formatos disponíveis

Baixe no formato PDF, TXT ou leia online no Scribd

Você está na página 1de 10

1

A Review on the Regulation of Limited Liability

Implications for Reform

INTRODUCTION

The limited liability doctrine refers to the capping of the liabilities of members of

a company for the companys debts (Company Ord (Cap 32) s4(2) and s170(1))

as generally justified on economic basis. A related concept is the separate legal

entity doctrine as laid down under Salomon v Salomon [1897] AC 22. When the

aforesaid two doctrines are applied together, they can potentially be abused

which lead to unjust results to the companys creditors. The law has attempted

to correct such injustice through the doctrine of piercing the corporate veil - by

disregarding the separate entity of the company and imposing liability or

conferring rights of the company onto persons behind the company (e.g.

shareholders or directors).

Regulation of limited liability is a controversial subject. In the rest of this paper,

I will outline the current laws in Hong Kong on this subject, followed by a

discussion of the problems of the status quo and recommendations to address

the shortcomings. I will then conclude with a suggestion for the necessary

reforms.

CURRENT LAWS REGULATING LIMITED LIABILITY IN HONG KONG

Limited liability is mainly governed by common law together with some statutes

in Hong Kong.

Common Law

Common Law has pierced the corporate veil in the following scenarios

(1) Evading existing liabilities

Where a company is regarded as a sham or a mere device for evasion of an

existing legal obligation of another person or entity, the court will be ready to

pierce the corporate veil, as in Gilford Motor Co v Horne [1933] 1 Ch 935 and

Jones v Lipman [1962] 1 WLR 832. The same principle has been adopted in the

Hong Kong case of Liu Hon Ying v Hua Xin State Enterprise (Hong Kong) Ltd

[2003] 3 HKLRD 347. Nevertheless, avoiding contingent future liabilities is

2

permissible

as ruled in China Ocean Shipping Co v Mitrans Shipping Co Ltd [1995]

HKCA 604.

(2) Fraud

Use of a company to perpetrate fraud could lead the court to pierce the

corporate veil to impose liability where necessary, as illustrated in HKSAR v

Leung Yat Ming [1999] 2 HKLRD 402, HKSAR v Sin Law Yuk Lin & Another [2002]

HKEC 378 English Judgment and in Re Darby [1911] 1 KB 95.

(3) Corporate Groups

The corporate veil between companies in a group would not be pierced merely

because of the fact that the companies belong to a group (see e.g. Woolfson v

Strathclyde Regional Council 1978 SC (HL) 90, 1978 SLT 159). The court may,

however, pierce the corporate veil of a group of companies when one or more of

the following principles are applicable:

Agency

Sometimes the corporate veil is pierced on the basis of agency between the

subsidiary and its parent holding company (see e.g. discussion by Krishnaprasad,

K. V., Agency, Limited Liability and the Corporate Veil (2011) Comp. Law 163).

In Smith Stone and Knight Ltd v City of Birmingham [1939] 4 All ER 116 the

significant factors were that the parent company did not transfer the business to

the wholly owned subsidiary and the subsidiary profits were treated as those of

the parent company. The mere fact that a company is under the practical

control of a person does not give rise to an agency (Salomon v Salomon [1897]

AC 22, Adams v Cape Industries Plc [1990] 2 WLR 748).

Single Economic Unit

This principle is illustrated in DHN Food distribution Ltd v Tower Hamlets London

Borough Council [1976] 1 WLR 852, in which Lord Denning referred the parent

company and two wholly owned subsidiaries as virtually the same as a

partnership and the three companies should be treated as one.

A mere facade

One test suggested for veil piercing is where there are special circumstances

alleging that the company is a mere facade concealing the true facts: see e.g.

aforementioned cases like Woolfson, Adams and DHN, and the case of Toptrans

v Delta Resources Co Inc [2005] 1 HKLRD 635 CFI.

3

Note that justice may sometimes be considered as a factor in veil piercing rulings,

e.g. as in the case of DHN. Yet this factor is never solely decisive (Adams v

Cape Industries Plc [1990] 1 Ch 443 at 544; China Ocean Shipping Co v Mitrans

Shipping Co Ltd [1995] HKCA 604 at p.8).

Statutes

Limited liability is also governed by legislations. Examples are:

a. Company Ordinance (Cap 32)

Under s275, a person who is knowingly a party to carrying on the business with

intent to defraud any creditors, or for any fraudulent purpose, may be personally

liable with unlimited liability for the companys debts or other liabilities.

b. Transfer of Business (Protection of Creditors) Ordinance (Cap 49)

A transferee of a business will be liable for the debts and obligation of the

transferor arising out of the transferred business unless he is a bona fide

purchaser without notice of such liabilities (s3), or if he can rely on other

exemptions such as the limitation period of 1 year (s9) or other savings as

provided for in the Ordinance (s10). Thus, if a shareholder transfers a business

of his company to another company under his control, he will be deemed to have

constructive notice of the debts of the transferor and liability will likely be

imposed upon the transferee subject to the aforesaid exemptions.

c. Criminal Procedure Ordinance (Cap 221)

S101E provides that where a company has committed an offence under any

Ordinance with the consent or connivance of a director or other officer in the

management of the company (or any person purporting to act as such director

or officer), the director or other officer shall be guilty of the like offence (see R v

Mirchandani [1977] HKLRD 523). Thus a shareholder will be liable for the

statutory offences committed by the company if he is a director of the company

or the master-mind behind.

d. Inland Revenue Ordinance (Cap 112)

Where the Commissioner of Inland Revenue has reason to believe certain

transactions have the effect of evading tax, the corporate veil can be lifted (s61

and 61A).

RECENT DEVELOPMENT IN THE UK

4

A new principle in piercing the corporate veil has emerged recently in the UK.

In Ben Hashem v Ali Shavif [2008] EWHC 2380 (Fam), Munby J (as he then was)

after reviewing the available authorities in which the court has been willing to

pierce the corporate veil concluded (at para 199 of his judgment) that the

wrongdoing must exist dehors the company. Here the phrase dehors the

company means something outside the ordinary business of the company. This

new principle was applied by Flaux J, albeit obiter, in Lindsay v OLaughnane

[2010] EWHC 529 QB at 134. Yet in Antonio Gramsci Shipping v Stepanovs

[2011] 1 Lloyds Rep 647 at para 15, the necessity of such condition for piercing

decision was doubted by Burton J when the sole purpose of the corporate

structure is to perpetrate fraud.

PROBLEMS IN THIS AREA OF LAW

Despite many economic benefits such as reducing agency cost (Easterbrook, F. E.

and Fischel, D. R., Limited liability and the corporation, (1985) 52 U. Chi. L. Rev.,

89, at 92), promotion of investment (Posner, R. A., The rights of creditors of

affiliated corporations (1976) 43 U. Chi. L. Rev., at 503) and free transfer of

shares (Clark, R. C., The regulation of financial holding companies (1979) 92(4)

Harv. L. Rev., at 825), limited liability has occasionally led to injustice to creditors

as discussed early on. Yet the way the court acts to correct such injustices via

veil piercing have also attracted criticism, which are summarised in the following

categories:

1. Lack of coherent principles

Courts often explain their decision to pierce by describing the company as a

mere sham or facade (Vandekerckhove, Karen, Piercing the Corporate Veil,

(2007 Kluwer The Netherlands), at para 3.6.8 and 3.7.6), or as the defendants

alter ego (Vandekerchhove, Karen, above, at para 3.7.4). Yet labelling using

such vague and confusing terms do not convey a clear legal reasoning for the

piercing decision.

For example, inWoolfson the court did not follow ruling in a previous similar case

of DHN and held that the corporate veil between the group of companies did not

fall within the facade exception but offered no guidance on what would be

within. It has been suggested that the underlying reasons for a UK judge to lift

the corporate veil are probably his subjective perception of fairness or policy,

which is therefore difficult to predict (Hicks, Andrew and Goo, S. H., Cases &

Materials on Company Law (6

th

ed 2008 OUP Oxford), p.103).

5

The new and yet unsettled principle that the wrongdoing must exist dehors the

company in some recent UK cases, as discussed earlier, represents another

example of the lack of consistent principle in this area of law.

Situation in Hong Kong is no better. In Lee Sow Keng Janet v Kelly Mckenzie Ltd

[2004] 3 HKLRD 517 the defendants argument that the liquidator (but not the

plaintiff) would have the locus standi to sue was explicitly rejected by the Court

of Appeal, which regarded the defendant as a mere facade and affirmed the

lower courts piercing decision. However, in Horace Yao Yee Cheong & Ors v

Pearl Oriental Innovation Ltd [2010] HKEC 537 at para 16 and 37, the same

argument was accepted by the appeal court who commented the lower courts

finding of impropriety, wrongdoing, concealment, sham or fraud as lack of clear

guidance and overturned the lower courts piercing decision. Yet there is no

clear indication as to whether the ratio in Lee Sow Keng case has been overtaken

by the Horace Yao case as Lee Sow Keng was not considered in Horace Yao or

any subsequent cases.

The US courts in veil piercing cases have gone even further from the

instrumentality test (e.g. Powell rule, see Krendl, Cathy S. and Krendl, James R.,

Piercing the Corporate Veil: Focusing the Inquiry (1978) 55 Denver L.J. 1) to

adoption of a template approach by constructing a list of factors where prior

cases have been considered in piercing decisions (Gevurtz, Franklin A., Piercing

Piercing: An Attempt to Lift the Veil of Confusion Surrounding the Doctrine of

Piercing the Corporate Veil (1997) 76 Or. L. Rev., at p.875). The context of the

current case is then compared with the list and decision to pierce made if there

exists enough facts to fit the list. The major drawback of this template approach,

as commented by Gevurtz (above, at p. 857-858), is the indeterminacy as to how

many of the factors, if not all, must be proven before the piercing decision can

be affirm.

2. Differential treatment towards contract creditors and tort creditors

Many writers have advocated that courts should differentiate between piercing

claims raised by contract (voluntary) creditors and tort (involuntary) creditors of

the company. Such view is premised on the belief of freedom of contract

between the contract creditors and the limited company - if the contract

creditors so wish they can require a guarantee from the shareholders or charge a

higher interest rate to compensate for the risk exposure, and the court should be

slow to intervene in such veil piercing cases (Gevurtz, above, at p. 859). In

contrast, the tort claimants inability to self-protect ex ante against the insolvent

6

company renders their judgment nugatory. Thus tort claimants warrant more

sympathy from the courts in veil piercing claims. Empirical evidences, as will be

discussed later, have refuted such theoretical ideology.

3. Differential treatment towards an individual controlling shareholder and a

corporation controlling shareholder

Some commentators have avowed that the courts should be more ready in

piercing the veil of a company whose controlling shareholder is another company

rather than an individual (e.g. Easterbrook and Fischel, above, at 110 111).

Others have argued that there should be no reason to distinguish between

individual and controlling shareholders (Gevurtz, above, at 897). Many others

assert that the courts ought to be more ready in lifting the veil of companies with

an individual controlling shareholder as the limited liability for closely held

companies increases the chances of risky behaviour (Andersen, Helen, Piercing

The Veil on Corporate Groups in Australia: The Case For Reform (2009), 33 Melb.

U. L. Rev. 333, at 346). Apparently there is no consensus in this academic

debate.

INSIGHTS FROM EMPIRICAL STUDIES

While there is considerable support from the literatures for the various schools of

thoughts discussed in last two paragraphs, I would argue that some of them

cannot stand in light of the available empirical studies on veil piercing. For

instance, Thompson based on a study of 1600 cases found that (Thompson,

Robert B., Piercing the Corporate Veil: An Empirical Study (1990-91) 76 Cornell

L Rev., 1036):

courts pierce less than in tort than in contract contexts (contrary to

the theoretical construct of the voluntary creditors);

piercing is more likely in cases involving individual shareholders rather

than corporation shareholder (contrary to the theoretical

counter-argument that courts should be more ready to pierce the veils

of corporation shareholders than individual shareholders);

likelihood of piercing increases as the number of shareholders

decreases;

misrepresentation and undercapitalization (or other frauds) do make a

difference, but is more pronounced in contract settings than in tort or

statutory settings;

piercing only occurs within corporate groups or in private companies

7

but not in public companies;

reasoning of the courts in cases which piercing was effectuated varies

with the context.

Other empirical studies have affirmed the above results. (see e.g. Thompson,

Robert B., Piercing The Veil within Corporate Groups: Corporate Shareholders as

Mere Investors (1998-1999) 13 Conn. J. Int'l L. 379; Ramsay, Ian M. and Noakes,

David B., Piercing the Corporate Veil in Australia, (2001) 19 Com and Sec L. J.

250 271; Oh, Peter B., Veil-Piercing (2010-2011) 89 Tex L. Rev. 81). Matheson

in his independent empirical studies have provided additional insights (Matheson,

John H., The Modern Law of Corporate Groups: An Empirical Study of Piercing

the Corporate Veil in the Parent-Subsidiary Context (2008-2009) 87 N.C.L. Rev.

1091; Matheson, John H., Why Courts Pierce: An Empirical Study of Piercing the

Corporate Veil (2010) 7 Berkely Bus. L.J. 1):

appellate courts pierce twice as often as trial courts;

entity plaintiffs succeeded more than twice likely than individual

plaintiffs in piercing the subsidiarys veil.

although plaintiff category (i.e. individual or entity) and claim category

(tort, contract, etc) tell us when courts pierce, they do not explain why;

fraud, owner control and mixing of funds give the most significant and

predictive power on corporate veil piercing the presence or absence of

these factors alone is often deterministic of the piercing decision;

DISCUSSION BETWEEN THEORETICAL BELIEVES AND EMPIRICAL

FINDINGS

Although many theorists advocate that the courts should be more readily in

piercing the corporate veils in cases involving tort claimants than contract

claimants, and having corporate shareholders than individual shareholders, the

reverse is observed from the empirical findings. Apparently the doctrinal

analysis of the corporate veil piercing cannot give a satisfactory account of this

myth. Then how can it be explained?

I would like to offer an alternative explanation from a social jurisprudence

analysis. Galanter observed that the haves (those with richer resources and

competency in litigation) outperformed the have-nots (those underprivileged in

litigation), and concluded that legal reforms alone will not be a panacea in

8

reducing the gap between the two classes of players (Galanter, Marc, Why the

Haves Come Out Ahead: Speculation on the Limits of Legal Changes (1974) 9

Law & Society Rev. 1). His observation has been affirmed by a number of

subsequent empirical studies (See the literature review discussed in He, Xin and

Su, Yang, Do the Haves come out again in Shanghai courts?, paper presented

at the 2

nd

Int Conference on the New Haven School (23-24 Nov 2010) in Hong

Kong).

In the context of Galanters theory individual/tort plaintiffs and individual

shareholders are generally classified as the have-nots whereas entity/contract

plaintiffs and corporation shareholders are regarded as the haves. This view is

consistent with the empirical finding that the appellate courts are more likely to

pierce the corporate veils than the first instant courts e.g. an individual/tort

claimant (have-not) who lost the veil piercing case in the first instant may not

have the necessary resource to appeal, especially if he is financed by legal aid in

the first place, where as an entity/contract plaintiff in general has better

resource to support an appeal to the appellate court which has a higher

tendency to pierce the corporate veils than the lower courts. Applying

Galanters theory, any legal reforms alone, including judicial activism in reducing

the comparative disadvantage of the have-nots will be limited in its effectiveness

(Galanter, above, at p.44-48).

Furthermore, I would argue that attention on the above myth in company law is

actually mis-focus of the issue. It is in effect an example of the inequality

between the haves and have-nots in a much wider context, in which an effectual

remedy is to convert the have-nots into the haves, e.g. by forming clusters of

self-help association such as labour unions (Galanter, above, at p.50-52).

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR REFORM

From the previous discussion, it follows that any reform on the regulations of the

limited liability, or the veil piercing doctrine should be focused on the lack of

coherent legal principles in adjudicating veil piercing cases of the status quo,

rather than attempting to balance the inequality between the haves and

have-nots. One possible reform is thus to codify the generally accepted legal

principles into statutes, such as by embracing them in the current statutes

regulating limited liabilities discussed early on. Cupuano, for example,

9

identified (i) control; (ii) an act warranting the piercing of the veil; and (iii) mala

fides as the three general principles guiding veil piercing cases ( Cupuano,

Angelo, The Realists Guide to Piercing the Corporate Veil: Lessons from Hong

Kong and Singapore (2009) 14 Aus J. Corp Law 23), whereas only the third

principle is stipulated in our statutes as revealed from our earlier discussion on

statutes governing limited liability in Hong Kong. Another possibility is to fill the

loop-holes in the current law, such as a tort claimant can initiate an action for

compensation within 3 years for personal injury or 6 years otherwise (Limitation

Ord (Cap 347) s4 and 27) towards a corporate wrongdoer, whose window will be

curbed to only 1 year if the shareholder of that corporation transfer the business

to a third party (Transfer of Business (Protection of Creditors) Ord (Cap 40) s8).

In fact, similar codification reforms have been successfully introduced in some

other areas of the laws in Hong Kong, such as the codification of the common

law part-performance and resulting / constructive trust doctrines in the

Conveyances and Property Ordinance, codification of the common law nemo dat

rule and its exceptions in the Sales of Goods Ordinance, and the enactment of

the Misrepresentation Ordinance to enshrine common law principles on

misrepresentation in contract laws.

The major benefit of the proposed codification will be reduction in the

uncertainty in veil piercing rulings especially in the first instant courts. From

the empirical researches of Andersen and Thompson mentioned above, veil

piercing cases constitutes a highly litigious area in company law in the US.

Though I am unaware of any similar empirical data in Hong Kong, nonetheless

the proposed codification will result in saving of social resources in resolving

disputes in this area of claims. In addition, it will help deter corporate

mis-behaviours and decrease risk to creditors (both voluntary and involuntary)

and will thus be beneficial to the society at large.

CONCLUSIONS

Limited liability is a great privilege to shareholders of limited companies. Yet it

is a privilege which has to be exercised in a responsible manner. Currently it is

governed by common law via the doctrine of corporate veil piercing and by some

statutory provisions in Hong Kong. By referencing to literatures and empirical

studies I submit that current laws regulating the limited liabilities may lead to

uncertainty in judicial rulings. A proposed legal reform through codification of

the generally accepted legal principles in corporate veil piercing will address such

10

shortcoming and be beneficial to the society.

Dr Roger So

Fellow, Cheung Kong Centre for Negotiation and Dispute Resolution,

Law School of Shantou University

Você também pode gostar

- Limited LiabilityDocumento22 páginasLimited LiabilityAll Agreed CampaignAinda não há avaliações

- Agency LawDocumento9 páginasAgency LawWa HidAinda não há avaliações

- Assignment 3Documento5 páginasAssignment 3Winging FlyAinda não há avaliações

- Examiners' Reports 2019: LA3021 Company Law - Zone BDocumento17 páginasExaminers' Reports 2019: LA3021 Company Law - Zone BdaneelAinda não há avaliações

- COMPANY LAW LECTURE NOTES - Tracked - Nov15.2020Documento59 páginasCOMPANY LAW LECTURE NOTES - Tracked - Nov15.2020John Quachie100% (1)

- Minority Shareholder's Rights Under UK Company Law 2006 and Rights To Derivative Actions.Documento7 páginasMinority Shareholder's Rights Under UK Company Law 2006 and Rights To Derivative Actions.Raja Adnan LiaqatAinda não há avaliações

- Law Assignment IndividualDocumento7 páginasLaw Assignment IndividualMohamad WafiyAinda não há avaliações

- LW3902 Tutorial RevisionDocumento5 páginasLW3902 Tutorial RevisionWan Kam KwanAinda não há avaliações

- Company - Director Duties (Problems) 2017 ZA B Q7Documento5 páginasCompany - Director Duties (Problems) 2017 ZA B Q7Yip MfAinda não há avaliações

- ScribdDocumento6 páginasScribdjessicacheung090% (1)

- Article On Capital MaintenanceDocumento9 páginasArticle On Capital MaintenanceSamish Dhakal100% (1)

- Revitalising Gower's Legacy Reformingcompany Law in GhanaDocumento10 páginasRevitalising Gower's Legacy Reformingcompany Law in GhanaNana Kwaku Duffour KoduaAinda não há avaliações

- Articles of Association EssayDocumento4 páginasArticles of Association EssayChristopher HoAinda não há avaliações

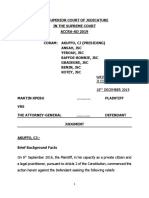

- Martin Kpebu Vrs The Attorney General-Valedictory JudgmentDocumento26 páginasMartin Kpebu Vrs The Attorney General-Valedictory Judgmentmyjoyonline.com100% (1)

- TABL2741 Case NoteDocumento7 páginasTABL2741 Case NotenessawhoAinda não há avaliações

- Sale of Goods Implied CoditionDocumento127 páginasSale of Goods Implied CoditionChaitanya PatilAinda não há avaliações

- Corporate Insolvency and Rescue in ZambiaDocumento4 páginasCorporate Insolvency and Rescue in ZambiaCHIMOAinda não há avaliações

- Notes On Economic TortsDocumento7 páginasNotes On Economic TortsMARY ESI ACHEAMPONGAinda não há avaliações

- Commercial LawDocumento32 páginasCommercial LawYUSHA-U YAKUBUAinda não há avaliações

- Unconscionability A Unifying Theme in EquitDocumento3 páginasUnconscionability A Unifying Theme in EquitshanicebegumAinda não há avaliações

- AgencyDocumento41 páginasAgencySimeony SimeAinda não há avaliações

- The Companies (Amendment) Act 2015Documento29 páginasThe Companies (Amendment) Act 2015Vikram PandyaAinda não há avaliações

- Promoters & Pre Incorporation ContractsDocumento4 páginasPromoters & Pre Incorporation ContractsKimberly TanAinda não há avaliações

- Commercial Law Lecture 1 Introduction To Sale of GoodsDocumento65 páginasCommercial Law Lecture 1 Introduction To Sale of GoodsDan Dan Dan DanAinda não há avaliações

- Veil of IncorporationDocumento2 páginasVeil of IncorporationShrestha Steve SalvatoreAinda não há avaliações

- Final Law Exam TipsDocumento6 páginasFinal Law Exam Tipsvivek1119Ainda não há avaliações

- Aberdeen Rail Co V Blaikie BrothersDocumento9 páginasAberdeen Rail Co V Blaikie BrothersYaw Mainoo100% (1)

- Retention of Title by The SellerDocumento5 páginasRetention of Title by The SellerDennis GreenAinda não há avaliações

- Company Law ProjectDocumento9 páginasCompany Law ProjectAmlan ChakrabortyAinda não há avaliações

- End of Sem Exam Prep - ImmovableDocumento87 páginasEnd of Sem Exam Prep - ImmovableKwame Annor100% (1)

- Freehold Covenants ADocumento3 páginasFreehold Covenants Aapi-234400353Ainda não há avaliações

- Piercing The Corporate Veil in Taxation Matters (Autosaved)Documento17 páginasPiercing The Corporate Veil in Taxation Matters (Autosaved)PRERNA BAHETIAinda não há avaliações

- Veil of IncorporationDocumento9 páginasVeil of IncorporationmfabbihaAinda não há avaliações

- Partnership and Company Law 148447820048447 PreviewDocumento3 páginasPartnership and Company Law 148447820048447 PreviewZati TyAinda não há avaliações

- Sample: Chapter 2: The Meaning of "Land"Documento5 páginasSample: Chapter 2: The Meaning of "Land"GabeyreAinda não há avaliações

- Case Study - Re Peveril Gold Mines LTDDocumento5 páginasCase Study - Re Peveril Gold Mines LTDRajat Kaushik100% (1)

- Company Law Midsem MCQ 2020 PDFDocumento11 páginasCompany Law Midsem MCQ 2020 PDFVeronica100% (1)

- Business Structures: Business Structures Tierney Kennedy FIN/571 David Binder April 13, 2015Documento7 páginasBusiness Structures: Business Structures Tierney Kennedy FIN/571 David Binder April 13, 2015tk12834966Ainda não há avaliações

- SharesDocumento9 páginasSharesIsaac Nortey AnnanAinda não há avaliações

- Assignment Partnership1Documento8 páginasAssignment Partnership1vivek1119100% (1)

- The Doctrine of Privity of Contract WikiDocumento4 páginasThe Doctrine of Privity of Contract WikiKumar Mangalam0% (1)

- Land LawDocumento11 páginasLand LawJoey WongAinda não há avaliações

- 1-Formation of A CompanyDocumento14 páginas1-Formation of A CompanyYwani Ayowe KasilaAinda não há avaliações

- Topic 6 - FlotationDocumento5 páginasTopic 6 - FlotationKeziah GakahuAinda não há avaliações

- Section 248 of Companies Act, 2013 - Power of Registrar To Remove Name of Company From Register of CompaniesDocumento6 páginasSection 248 of Companies Act, 2013 - Power of Registrar To Remove Name of Company From Register of Companiesmohammed ibrahim pashaAinda não há avaliações

- Chapter 6 Loan and DebenturesDocumento9 páginasChapter 6 Loan and DebenturesranunAinda não há avaliações

- Class Notes Business Entities, The ChoicesDocumento10 páginasClass Notes Business Entities, The ChoicesLydia.m. Asaba100% (1)

- Critically Assess The Rules On Capital Maintenance and Their Effectiveness in Protecting Creditors and ShareholdersDocumento24 páginasCritically Assess The Rules On Capital Maintenance and Their Effectiveness in Protecting Creditors and ShareholdersSidharth Shah100% (1)

- Company Law-1Documento244 páginasCompany Law-1kevoh1Ainda não há avaliações

- The Republic of Ghana Vs Charles Wereko-Brobbey and Kwadwo Okyere MpianiDocumento27 páginasThe Republic of Ghana Vs Charles Wereko-Brobbey and Kwadwo Okyere Mpianixebieso100% (2)

- Land LawDocumento40 páginasLand LawAnshul SinghAinda não há avaliações

- T3 Lifting The Veil of Incorporation AnswerDocumento16 páginasT3 Lifting The Veil of Incorporation AnswerEmy TanAinda não há avaliações

- Tort Law - Ryland V Fletcher Lecture NotesDocumento3 páginasTort Law - Ryland V Fletcher Lecture NotesAncellina ChinAinda não há avaliações

- Company Law Corporate VeilDocumento3 páginasCompany Law Corporate VeilKoye AdeyeyeAinda não há avaliações

- Salomon VS SalomonDocumento2 páginasSalomon VS SalomonCamillaAinda não há avaliações

- Transfer of Ownership by Non OwnerDocumento16 páginasTransfer of Ownership by Non OwnerYin Chien100% (1)

- HUNTER - v. - MOSS - (1993) - 1 - WLR - 934 (Chancery Division) PDFDocumento13 páginasHUNTER - v. - MOSS - (1993) - 1 - WLR - 934 (Chancery Division) PDFnur syazwinaAinda não há avaliações

- 5315 The Law of Shadow DirectorshipsDocumento31 páginas5315 The Law of Shadow DirectorshipsАлександр РумянцевAinda não há avaliações

- Crystallisation - JCLSDocumento19 páginasCrystallisation - JCLSamyorourke12Ainda não há avaliações

- Session 6 Extra Reading Piercing The VeilDocumento8 páginasSession 6 Extra Reading Piercing The VeilMasape ThomasAinda não há avaliações

- Future Generation Computer SystemsDocumento18 páginasFuture Generation Computer SystemsEkoAinda não há avaliações

- 1610-2311-Executive Summary-EnDocumento15 páginas1610-2311-Executive Summary-EnKayzha Shafira Ramadhani460 105Ainda não há avaliações

- Millets: Future of Food & FarmingDocumento16 páginasMillets: Future of Food & FarmingKIRAN100% (2)

- Application Form-Nguyen Huy CuongDocumento4 páginasApplication Form-Nguyen Huy Cuongapi-3798114Ainda não há avaliações

- Sample Pilots ChecklistDocumento2 páginasSample Pilots ChecklistKin kei MannAinda não há avaliações

- MAS-02 Cost Terms, Concepts and BehaviorDocumento4 páginasMAS-02 Cost Terms, Concepts and BehaviorMichael BaguyoAinda não há avaliações

- Mobilcut 102 Hoja TecnicaDocumento2 páginasMobilcut 102 Hoja TecnicaCAGERIGOAinda não há avaliações

- Final Answers Chap 002Documento174 páginasFinal Answers Chap 002valderramadavid67% (6)

- AFAR Problems PrelimDocumento11 páginasAFAR Problems PrelimLian Garl100% (8)

- DataBase Management Systems SlidesDocumento64 páginasDataBase Management Systems SlidesMukhesh InturiAinda não há avaliações

- The Perceived Barriers and Entrepreneurial Intention of Young Technical ProfessionalsDocumento6 páginasThe Perceived Barriers and Entrepreneurial Intention of Young Technical ProfessionalsAnatta OngAinda não há avaliações

- Factors Affecting The Rate of Chemical Reactions Notes Key 1Documento3 páginasFactors Affecting The Rate of Chemical Reactions Notes Key 1api-292000448Ainda não há avaliações

- DTDC Rate Quotation-4Documento3 páginasDTDC Rate Quotation-4Ujjwal Sen100% (1)

- Kilifi HRH Strategic Plan 2018-2021Documento106 páginasKilifi HRH Strategic Plan 2018-2021Philip OlesitauAinda não há avaliações

- Renvoi in Private International LawDocumento4 páginasRenvoi in Private International LawAgav VithanAinda não há avaliações

- General Electric/ Massachusetts State Records Request Response Part 3Documento673 páginasGeneral Electric/ Massachusetts State Records Request Response Part 3Gintautas DumciusAinda não há avaliações

- Audit Process - Performing Substantive TestDocumento49 páginasAudit Process - Performing Substantive TestBooks and Stuffs100% (1)

- Risk-Based IA Planning - Important ConsiderationsDocumento14 páginasRisk-Based IA Planning - Important ConsiderationsRajitha LakmalAinda não há avaliações

- Mercantile Law Zaragoza Vs Tan GR. No. 225544Documento3 páginasMercantile Law Zaragoza Vs Tan GR. No. 225544Ceasar Antonio100% (1)

- CIE Physics IGCSE: General Practical SkillsDocumento3 páginasCIE Physics IGCSE: General Practical SkillsSajid Mahmud ChoudhuryAinda não há avaliações

- TX Open RS232 - 485 Module (TXI2.OPEN)Documento8 páginasTX Open RS232 - 485 Module (TXI2.OPEN)harishupretiAinda não há avaliações

- Text That Girl Cheat Sheet NewDocumento25 páginasText That Girl Cheat Sheet NewfhgfghgfhAinda não há avaliações

- FC2060Documento10 páginasFC2060esnAinda não há avaliações

- Firmware Upgrade To SP3 From SP2: 1. Download Necessary Drivers For The OMNIKEY 5427 CKDocumento6 páginasFirmware Upgrade To SP3 From SP2: 1. Download Necessary Drivers For The OMNIKEY 5427 CKFilip Andru MorAinda não há avaliações

- Sage 200 Evolution Training JourneyDocumento5 páginasSage 200 Evolution Training JourneysibaAinda não há avaliações

- 4 FAR EAST BANK & TRUST COMPANY V DIAZ REALTY INCDocumento3 páginas4 FAR EAST BANK & TRUST COMPANY V DIAZ REALTY INCDanielleAinda não há avaliações

- Danais 150 ActuadoresDocumento28 páginasDanais 150 Actuadoresedark2009Ainda não há avaliações

- BSDC CCOE DRAWING FOR 2x6 KL R-1Documento1 páginaBSDC CCOE DRAWING FOR 2x6 KL R-1best viedosAinda não há avaliações

- Unit 1: Exercise 1: Match The Words With The Pictures. Use The Words in The BoxDocumento9 páginasUnit 1: Exercise 1: Match The Words With The Pictures. Use The Words in The BoxĐoàn Văn TiếnAinda não há avaliações

- Kolodin Agreement For Discipline by ConsentDocumento21 páginasKolodin Agreement For Discipline by ConsentJordan ConradsonAinda não há avaliações