Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Draw Better Sample

Enviado por

Simona Dumitru0 notas0% acharam este documento útil (0 voto)

68 visualizações26 páginasi

Direitos autorais

© © All Rights Reserved

Formatos disponíveis

PDF, TXT ou leia online no Scribd

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoi

Direitos autorais:

© All Rights Reserved

Formatos disponíveis

Baixe no formato PDF, TXT ou leia online no Scribd

0 notas0% acharam este documento útil (0 voto)

68 visualizações26 páginasDraw Better Sample

Enviado por

Simona Dumitrui

Direitos autorais:

© All Rights Reserved

Formatos disponíveis

Baixe no formato PDF, TXT ou leia online no Scribd

Você está na página 1de 26

draw better

Learn to Draw with Confdence

Dominique Audette

isbn 978-1-929565-40-5

All drawings copyright by the author.

2013 Brynmorgen Press

Brunswick, Maine 04011 usa

Dominique Audete Illustration & Text

Tim McCreight Design & Layout

Jay McCreight Editing

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be repro-

duced or transmited in any form or by any means, electronic

or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any

storage and retrieval system except by a reviewer who wishes

to quote brief passages in connection with a review writen for

inclusion in a magazine, newspaper, web posting, or broadcast.

Draw Beter

by Dominique Audete

Brynmorgen Press

contents

CONCEPTS

Geometric Solids 6

Orthographic Projection 10

Perspective 12

Light & Shadow 20

APPLICATIONS

Cubes & Boxes 34

Prisms 44

Pyramids 48

Curves 52

Ovals 58

Ellipses 60

Cylinders 65

Domes 82

Cones 88

Ribbons 93

COMBINATIONS 97

SPECIAL CASES 109

TECHNIQUE 117

1

3

4

2

5

about this book

INTRODUCTION

Te goal of this book is to allow anyone to improve their skills in draw-

ing. Beginners will learn the basic concepts of drawing and then be

able to apply these ideas to simple projects. Intermediate drafspeople

will fnd new challenges and insights. Troughout the book, everyday

objects are used to demonstrate specifc techniques. Part One presents

basic concepts of drawing, while Part Two suggests some drawing proj-

ects based on these concepts. Every project is is presented with step-

by-step drawings that visually explain the construction of the object.

Understanding that the people who use this book are visual learners,

images are the primary component here, with text kept to a minimum.

CONCEPTS

Draw Beter systematically presents fundamental concepts, starting

with the idea that even complicated shapes can be reduced to basic

geometric forms such as spheres, boxes, and cones. A description of or-

thographic projection teaches how to visualize an object in space. Tis

standard technique allows us to imagine an object from all angles, and

quickly provides a summary of the information that will be used to make

a fnished drawing. From there we move on to perspective, a trick that

allows us to make a two-dimensional image mimic a three-dimensional

reality. Te fnal concept is the addition of shading to enhance contrast

and increase the sense of volume within a drawing.

concepts

part one

1

geometric solids: basics

6

Basics:

Any object can be reduced to a geometric shape, as illustrated with these common objects.

Light bulb

Layout circles and rectangles.

Draw two curves by following

the circles.

Add the screw as shown,

using diagonals in the smalll

rectangle.

Cup

Draw a rectangle and two

concentric circles as shown.

Taper the base of the cup.

Round the corners and erase

a part of the larger circle.

Earthenware pot

Draw two long triangles, one

inside the other.

Cut the triangle as shown to

create the lip of the pot.

Erase most of the triangles to

leave the shape of the pot.

7

Spinning Top

Draw a circle with a rectangle

at the top and a triangle at

the base.

Connect the circle to the

triangle where the two

shapes meet (blue dots).

Round the edges of the rect-

angle and add ornamentation.

Watering can

Complex objects can be

constructed with a group of

geometric forms. Here circles,

rectangles and triangles are

needed.

Use the small circles to guide

the lines that connect the

handle to the body.

Use theoverlapping triangles

to form the spout.

Lamp

Circles, rectangles, and a

triangle are organized within a

large square for this lamp.

Cut the large circle horizontally

and draw lines on both sides

of the initial triangle lines to

give mass to the arm of the

lamp.

Add details.

geometric solids: advanced

8

Brush

Draw two rectangles, two circles

and a triangle, as shown.

Draw the shape of the handle

and use the circles to connect

the handle to the brush. Hori-

zontal lines represent details in

the ferrule (the metal part of

the brush).

Draw vertical lines to represent

the bristles and stretch the

triangle with random curves to

indicate fuid paint.

Teapot

Draw a primary circle with smaller

circles and ovals around it. Tese

will be used to determine the

location and shape of the handle

and spout.

Use the small geometric forms

to inform the shapes and

transitions between parts, as

shown in blue.

Connect the spout to the body

of the teapot and add details..

Advanced:

Te concept is the same for more complex forms, which might require more shapes to construct.

9

Traditional Chinese Figurine

Draw rectangles and triangles to

start the form.

Add other geometric shapes

and curves to locate details such

as the hat, face, shoulders, hands

and robe.

Complete the drawing by add-

ing details and indications

of shading.

Classical Building

Draw geometric solids as

showna circle, a triangle and

rectangles.

Draw additional lines along the

roof and add a small circle and

rectangles to indicate a door.

Draw vertical lines for the col-

umns and curves on the dome.

Use the center of the small circle

and the corners of the large

square to defne the outlines of

a staircase.

Complete the drawing

with shading.

10

orthographic projection

Orthographic projection refers to a single drawing that shows several

views of an objecttypically the top, front, and side views. In addition

to providing detailed information about the object, it also helps us

understand where to place lights and shadows.

Side view: Project all dimensions

horizontally from the front view.

From the top view, project informa-

tion horizontally, then redirect the

projectors vertically using the 45

line. Tese projectors intersect

those from the front view to defne

the outline of the cup. Usually,

three views are enough

to depict an object.

Imagine an object

placed inside a transparent box.

Each face of the object is parallel to the

surfaces of the box and visible through it. Now imagine

the outlines of the object drawn on the faces of the box,

each face showing what is directly in front of it.

Te box can be

unfolded to show all the

sides of the box at the same

timea two-dimensional view show-

ing many views of the object.

Tis approach is called the

Orthographic Projection.

Te word orthographic

comes from the Greek

orthos, meaning straight

and graphia, meaning writing.

Front view: Draw the

outlines of the cup.

Top view: Project all

dimensions up from the

front view, using dashed

lines to depict hidden

features. Te lines used

for projection are called

projectors.

45 line

11

orthographic projection

Front View

Chair

Imagine a chair inside a glass

box, then imagine tracing the

shapes of the chair onto each

glass panel, shown here in blue.

Front view: Draw the outlines

of the chair, front legs, thickness

of the seat and the back.

Side view: Draw projectors

from the front view, including

the thickness of the seat.

Top view: Project all dimen-

sions up from the front and

side views.

Side View

Top View

As shown, the side view dimensions

need to be bent at 90 on the seg-

ment at 45 to complete the top view.

perspective: introduction

12

Basics

Perspective is a drawing technique that allows a

three-dimensional object to be reproduced on pa-

per as the observer sees it in space with a life-like

appearance. To say it another way, the top, front,

and side views (orthographic projection), can all

be seen in the same image. Te concepts underly-

ing perspective provide an understanding of the

mechanisms that make it work. We will begin with

a series of exercises that illustrate these concepts,

creating drawings of surfaces (i.e., fat planes) and

volumes (e.g., boxes) that will then be sliced and

divided as needed to make other shapes.

One Vanishing Point

Perspective drawing that uses just one vanishing point is good

for a simple object and gives the appearance of distance.

Start with a rectangle (A).

Draw a horizon line at the top of the page to represent

the eye level of the observer. Place a vanishing point

on this line. For now, the location of this point can be

random.

Draw vanishing lines from each corner to the vanishing

point (B).

Draw a second square, further along, touching each of

the vanishing lines (C).

Boxes of any size can be made this way,

depending of the size of the frst rectangle

and the distance to the second rectangle.

vanishing

point

A B C

horizon line

vanishing line

Te vanishing

point can be in

the middle of the

page. When the

boxes are above

the vanishing

point, it appears

that the observer

is below the box.

One or Two Vanishing Points?

Use one vanishing point when an object presents a plane facing the front. One-

point perspective is a good way to get started in perspective drawing, but it cant

be used for every object in every position.

In drawings A and B below, the houses seem to be represented correctly because

the front of the house is facing the observer. In the drawing labeled C we start to see

some distortion. In D, the distortion is clearly visible because it is impossible to see

the front face of the house, represented with angles at 90, and the side of the house

on the same drawing. Te drawing at the botom looks more natural. When a front

corner is facing the viewer, two-point perspective should be used. Tis presents the

front and the side of the house at an angle as they will appear in reality.

A B C D

horizon line

horizon line

13

One-Point

Perspective

Two-Point

Perspective

perspective basics

14

Using a ruler, draw two vanishing lines that cross from the

right side to the lef point and vice versa. Tey meet at

the point D to complete the surface ABCD.

Highlight these lines (or erase the vanishing lines, which

are no longer needed) and the result is a square or

rectangular plane shown in perspective.

Basics: Quadrilateral

Te most basic form drawn in perspective

is a rectangle as seen from a front edge.

Draw the horizon line at the top of the page and

place the vanishing points at the ends of it. Te lef

vanishing point will be called LVP and the right one RVP.

Place the point A below the horizon line. Tis point rep-

resents the botom corner of the quadrilateral.

From this point, run a vanishing line toward LVP and

another toward RVP. To depict the object realistically,

angle A of the corner formed by the frst two vanishing

lines should be greater than 90.

horizon line

vanishing line

vanishing line

vanishing line

LVP

LVP

LVP

RVP

RVP

A

A

D

Make two marks on the angled lines, shown here as

B and C. Te dimensions are arbitrary. Tese will become

the outside corners of the resulting rectangle (technically

called a quadrilateral).

B

B

C

C

RVP

horizon line

perspective basics

15

RVP

Point of View: To create diferent shapes,

change the location of the two side points

(B & C). To change the angle of viewing, place

the botom point of any quadrilateral closer or

further from the horizon line. To change the view

as if seen from below, place the quadrilateral

above the horizon line.

Counter example: When the angle A is too

narrow the result is an unrealistic distorted look.

To create a more believable perspective, place

the two vanishing points far apart and keep

point A relatively close to the horizon line.

Square: To accurately depict a perfect square, locate

the point A equidistant from the two vanishing points

and the two side points (B) and (C) equidistant from the

botom point. Tis should automatically place the upper

crossing point (D) directly above the botom point.

D

A

A

B

B

C

C

A

less than 90

horizon line

horizon line

horizon line

vanishing line

LVP

perspecti ve: quadrilaterals

16

From the intersection with the

diagonal, draw a line toward

the lef vanishing point. Te two

interior lines are now equidistant

from the center.

Start with a quadrilateral, then draw

the diagonals corner to corner.

Draw a line that connects the inter-

section of the diagonals with the

right vanishing point.

Te fgure can also be divided in

the other direction, creating four

equal parts.

Each part can also be divided.

Tere is no limit to the number

of subdivisions.

Finding

Centerlines

Dividing

Symmetrically

Choose any point on the quadrilat-

eral and draw a line from there to

the lef vanishing point.

At the intersection of the vanish-

ing line with a diagonal (A), draw

another line toward the right

vanishing point.

Perspective drawings, by defnition, play games with

measurement. Parts that in reality are of equal length are

drawn as unequal, which is what makes them appear to

exist in space. To make measurements within this

invented space, we use diagonals.

A

Quadrilaterals

within

Quadrilaterals

Using this technique, any number

of smaller quadrilaterals can be

created within the original.

and redirect these vanishing

lines until they meet the diagonals.

Choose a location for the frst cor-

ner of the smaller quadrilateral and

run two vanishing lines until they

meet the diagonals

17

Boxes can be created in other shapes

and dimensions by changing the pro-

portions of the quadrilateral and the

length of the verticals.

From Planes to Boxes

To draw a volume from a

surface, start with a quadri-

lateral, then draw verticals

from each corner.

Determine the height of the box by

marking a point on the front edge

(arrow). Draw lines from this point to

the lef and right vanishing points

to establish the top of the box.

Using the diagonals of the

previous exercise, draw lines

to both vanishing points.

Draw diagonals on the lef side of a box

to determine the center point. Using this

point, draw a vertical line (AB), and from

the top and botom of this line, connect

to the vanishing points.

Draw diagonals on the right side of

the box and proceed the same way,

using the lef vanishing point.

Bisecting Boxes

B

A

To make the interior box slice all the way

through the larger box, draw diagonals

on the opposite face. Draw a vertical

from the place where the vanishing line

meets the diagonal (arrow).

Internal

Boxes

To draw a box within a box, create

diagonals as above, draw two

vertical lines, and from the top and

botom of those, draw lines to the

lef vanishing point.

Draw lines from each corner to the

right vanishing point. Determine

the depth of the interior box with a

vertical (A), then draw a line to the

lef vanishing point.

A

perspecti ve: boxes

vanishing points

18

Boxes are important because they provide a structure for other forms.

Draw diagonals on the top

and botom of the box

then connect the points

with smooth curves.

Draw vertical lines to

connect the outer points

of the two ellipses to

form a cylinder.

To make a cone, create an

ellipse on the base of a

box, then connect the outer

points to the intersection of

the top diagonals.

Cylinders & Cones

Complex Forms

A square box seen from the

top would contain a circle that

touches the midpoint of each

of the four sides.

In each of these forms, the preliminary drawing in the upper corner shows

how familiar geometric forms were used to construct complex forms.

perspecti ve: cylinders & cones

19

Adding light and shadow to the outline of an object helps to give it volume. Tis

makes the drawing more lifelike and therefore more efective. Light and shadow

go hand in handeach one exists through its contrast with the other.

Light and shadow are so important in a draw-

ing that they can almost depict an object even

without outlines. In this example for instance, the

shadow is sufcient to recognize the object.

When both light and shadow are rep-

resented the object comes to life. Tis

efect is so powerful that outlines are not

absolutely necessary for simple objects.

In the same way, light alone can ofen

describe an object. Light is rendered here

with white pencil on colored paper.

light & shadow: introduction

When we start including shadows, it

is helpful to use pencils of diferent

hardness. Draw the outlines with a

hard graphite pencil (e.g. 4H) and de-

pict the shadows with a sofer graph-

ite such as HB or 2B. Because the 4H

graphite is hard, it will not blend when

the stump is used to spread the sofer

graphite in a gradation. Tis means that

the outlines will stay in place.

Tip:

light & shadow basics

Te placement of the light

source must create sufcient

contrast to emphasize the

object. Placing the source

behind the object usually

creates the best environ-

ment for this light/dark

dynamic to occur.

Te source and quality of light afects objects and should be considered in every drawing.

An artifcial light

source, a light bulb

for instance, projects

divergent rays

toward an object.

Natural light of the sun is pro-

jected in parallel rays toward an

object. Tis natural source will

be used in this book. It is easier

to pinpoint areas of light and

shadow on objects with natural

rather than with artifcial light.

Drawings require that we choose

a direction from which the

light is coming. In general, it is

accepted practice to place the

light source above and to the

lef of the object, but the rays

can come from any direction, as

shown here.

Form shadow occurs

on the surfaces away

from the light source,

that is, in areas the light

rays cannot reach. More

on page 25.

Light zones are surfaces

that are struck directly by

the light rays. Te rays strike

the object at precise loca-

tions to create these zones.

Elsewhere, the rays miss the

object, leaving shadow.

Te highlight is the pre-

cise location of a light zone

where the light strikes the

object directly, that is, at a

90 angle to the surface.

Tis is the most brightly lit

area of an object.

Refected light is light that

bounces back from neigh-

boring surfaces onto the

shadow side of the object.

20

21

Te formal defnition of a cast shadow is the shaded area produced

when a raised non-transparent object blocks the light from striking

the surface on which it lies or an adjacent surface. Or simply, When

you block light, you create shadow. In drawing, shadows help us

communicate the size and solidness of objects.

A sketch of the profle helps to envision

where the cast shadows will fall.

In a three-quarter view,

the light rays (A) and their traces (B)

are integrated into one single view. Te cast

shadow is darker than the form shadow.

cast shadow basics

B

B

B

A

A

Te top view has an over-

head view with a profle.

Te cast shadow in the top view is depicted

the same way as a form shadow on complex

shapes, using the rays (A) and their traces (B)

with two separate drawings.

cast shadow: top view

Te cast shadow is shown on the top view using the same procedure

as the Form Shadow on a Complex Shape, page 26.

On the top view, draw traces on

each side of the box to locate the

edges of the cast shadow.

Te height of the light source above the object

determines the length of the shadow.

Tese two sketches show the same information

conveyed above, this time in three-quarter view.

An overhead view with a profle

provides placement details.

Use the ray from the drawing at

the right to determine the length

of the cast shadow.

We know that the shadows we cast at midday are

shorter than those we cast in the morning and evening.

22

ray

rays

trace

rays

(in the air)

ray

trace

traces

(on the ground)

cast shadow: perspecti ve & volume

A cast shadow is infuenced by the height and direction of the light source. Te

light rays and their traces on the ground are integrated into one single view.

Place the light source (A) at the upper lef, and

project a ray through the upper point of the rod.

Te ray determines the length of the cast shadow.

Place the foot of the source (B) by dropping a verti-

cal from the light source on the ground, and project

a trace through the lower point of the rod. Te foot

of the light source determines the direction of the

cast shadow. Te meeting point (C) of the ray and

its trace determine the far end of the cast shadow.

A

A

B

B

C

C

E

D

Rod Surface

Drawing the shadow cast by

a surface is similar to the rod

example. Place the light source at A

as before and project a line through the top edge of the

surface. Drop a line from A and project a line from there

through the lower corner of the surface to fnd point (C).

Draw a line that is parallel to the frst one (AC), this one go-

ing through D. Tey will meet at the point (E) to determine

the shape and length of the cast shadow.

In this example, the light source is not at a right angle to the

box so the shadow is cast toward the viewer. Start as before

to locate the main shadow, then project a line from A to the

top corners of the volume to locate points B and C. Darken

the cast shadow zone and give it very sharp edges. Note

that the form shadow on the volume is lighter and smooth-

er than the cast shadow.

Here the light source is somewhat near the viewer,

of to the lef. Notice how this increases the dramatic

impact. Te process is the same as before: darken the

cast shadow and give it sharp edges. Again, the form

shadow is lighter and smoother than the cast shadow.

A

B

C

C

23

Volume

24

Shortcut to Make a Cast Shadow for a Complex Shape

will develop a cast

shadow in a recessed shape.

Sliding the sheet of

tracing paper away

from the light source

Te area between the original

fgure and the repositioned one

corresponds to the shadow zone.

Te result shows the object as

raised up and casting a shadow.

3. Slide the tracing paper sheet

toward the light source and

copy the complex curves.

2. Reproduce the drawing

on tracing paper.

Te shape of a cast shadow always mirrors the form that generates

iteven a form with a complex and irregular shape. Here is a simple

way to draw the cast shadow of a complex shape.

1. Draw a complex curve

on a piece of paper.

cast shadow: top view

To help visualize where the form

shadow occurs on an object,

sketch a top view of the object

(top row). Indicate the direction

of light with an arrow, (as shown

in blue). On fat planes (seen in

the box and pyramid), the light

falls evenly on the surface facing

the light. On curved forms such as

a cylinder, cone and sphere, the

light gradually fades to shadows,

again indicated by the shorthand

of arrows. Tese sketches provide

maps that help determine where

the shadows will fall.

For fat surfaces, use a uniform

gray to indicate shadows. To

create the gradiation as light falls

across a curved surface, use a

cardboard stump to spread the

graphite dust of the pencil lines.

Note that on rounded surfaces,

the shadow doesnt touch the

edges of the shape because those

areas are illuminated by light

refecting of the surrounding

surfaces.

As shown here, the light falling on the tops of these objects is

more intense because we are following the convention that

the light comes from above and to the lef of the object. For

example, the top of the cube is lighter than its side.

form shadow: introduction

25

26

When working on

colored paper, high-

lights are added. In

this case, it is a circle

of white, moved to-

ward the light source.

Sometimes the top view is insuf-

cient to pinpoint the shadow zones,

such as in a volumetric object like

this donut. In these cases, a side

view should be used. On the top

view, project a light ray through the

center to the far edge. Te ray (A)

identifes the location of the shadow

zone, but not its extent.

Project a side view (B) by creating

lines perpendicular to the light ray.

Te efect is like cuting the donut in

half then geting down to eye level to

see where the light hits.

Mark where the light will hit the object.

At the areas marked C, the rays strike

the curves. Te areas marked D indicate

where the light no longer touches the

object, i.e., the shadow zone. Carry this

information down the arrows to indicate

where shadows will fall on the object.

Tis shows the original top view

and below it, a new drawing

that uses the shadow placement

information gained in the preced-

ing sketches. Shading is done with a

sof pencil and a stump.

Adding a Form Shadow to a Complex Shape

Tis example shows a process that clarifes the

shape and cross section of an object, registers the

angle of illumination, and then follows through

with shading and highlights. Tis process will be

used frequently throughout the rest of this book,

so it will be helpful to study it here.

ray

B

C

C

D

D

form shadow: complex shape

ray

A

Você também pode gostar

- 8 FD - Week 1 - Adonis CaraDocumento15 páginas8 FD - Week 1 - Adonis CaraRamlede Benosa100% (1)

- Draw Better Learn To Draw With Confidence Dominique AudetteDocumento26 páginasDraw Better Learn To Draw With Confidence Dominique Audettesaioa plastikaAinda não há avaliações

- Sketch Like An ArchitectDocumento6 páginasSketch Like An ArchitectJohn Mark MarquezAinda não há avaliações

- Perspective Drawing DemoDocumento33 páginasPerspective Drawing DemoJOHN ALFRED MANANGGITAinda não há avaliações

- Lesson Plan For Basic Art ClassDocumento11 páginasLesson Plan For Basic Art ClasstiggmanjeAinda não há avaliações

- Compositional Devises Including Linear and Aerial PerspectivesDocumento28 páginasCompositional Devises Including Linear and Aerial Perspectivesjohan shane carsidoAinda não há avaliações

- Drawing - SmileDocumento8 páginasDrawing - SmileIsabella De SantisAinda não há avaliações

- Freehand Sketching ExerciseDocumento1 páginaFreehand Sketching ExerciseChitteshs100% (2)

- 01 Basics, PencilTechnique PDFDocumento24 páginas01 Basics, PencilTechnique PDFMarietta Fragata RamiterreAinda não há avaliações

- Drawing TipsDocumento48 páginasDrawing Tipsamsula_1990Ainda não há avaliações

- When Comparing These Two Pictures, Nametwo Things On The Left That Are Out Ofproportion?Documento24 páginasWhen Comparing These Two Pictures, Nametwo Things On The Left That Are Out Ofproportion?RogerGalangueAinda não há avaliações

- Shading Basic Shapes Into FormsDocumento10 páginasShading Basic Shapes Into FormsPeter SteelAinda não há avaliações

- Chapter 1 - Perspective DrawingDocumento23 páginasChapter 1 - Perspective DrawingryanAinda não há avaliações

- Art Appreciation MidtermmmmDocumento104 páginasArt Appreciation MidtermmmmRodney MendozaAinda não há avaliações

- HowtodrawperspectiveDocumento33 páginasHowtodrawperspectiveCybrewspace Computer SalesAinda não há avaliações

- One-Point Perspectiv E: Just A Walk in The Park!"Documento39 páginasOne-Point Perspectiv E: Just A Walk in The Park!"ValerieAinda não há avaliações

- Techniques in Still-Life DrawingDocumento19 páginasTechniques in Still-Life DrawingCharmaine Janelle Samson-QuiambaoAinda não há avaliações

- PQG 21 - 30 Drawing - Made - EasyDocumento10 páginasPQG 21 - 30 Drawing - Made - EasyFernandes ManoelAinda não há avaliações

- Drawing FlowersDocumento89 páginasDrawing Flowerscaitlin loveAinda não há avaliações

- Drawing Mentor 11-13 Still Life Landscape & Portrait Drawing (PDFDrive)Documento156 páginasDrawing Mentor 11-13 Still Life Landscape & Portrait Drawing (PDFDrive)Siva Ranjani 12th A1Ainda não há avaliações

- Perspective: How Perspective Affects Your Drawings and Art?Documento10 páginasPerspective: How Perspective Affects Your Drawings and Art?Christian Dela Cruz100% (2)

- Pictorial DrawingDocumento15 páginasPictorial DrawingDharam JagroopAinda não há avaliações

- Pitcherof Lilies: Step 1Documento10 páginasPitcherof Lilies: Step 1Fernandes ManoelAinda não há avaliações

- 2 Point Perspective How To: Learn The Basics of Two Point Perspective With These BoxesDocumento21 páginas2 Point Perspective How To: Learn The Basics of Two Point Perspective With These BoxesAmaka NicholasAinda não há avaliações

- Which of These Paintings Has A More Realistic Setting and Why? How Has The Artist Created A Sense of Distance /depth?Documento47 páginasWhich of These Paintings Has A More Realistic Setting and Why? How Has The Artist Created A Sense of Distance /depth?Terry TanAinda não há avaliações

- Drawing & ShadingDocumento24 páginasDrawing & ShadingSaiful IdrisAinda não há avaliações

- Perspective Theory PDFDocumento14 páginasPerspective Theory PDFCassio MarquesAinda não há avaliações

- Another Way To Look at Things: 2 Point PerspectiveDocumento22 páginasAnother Way To Look at Things: 2 Point PerspectiveDean JezerAinda não há avaliações

- How To Draw A Portrait in Three Quarter View, Part 6Documento11 páginasHow To Draw A Portrait in Three Quarter View, Part 6Soc Rua NguyenAinda não há avaliações

- 0713 SampleDocumento37 páginas0713 SampleWorawan SuwansakornkulAinda não há avaliações

- Brenda Hoddinott: 11 Pages - 27 IllustrationsDocumento11 páginasBrenda Hoddinott: 11 Pages - 27 IllustrationsDaniela Alexandra DimacheAinda não há avaliações

- 8 Art GradationDocumento13 páginas8 Art GradationserenaasyaAinda não há avaliações

- Lesson 2 Shading TechniquesDocumento23 páginasLesson 2 Shading TechniquesAila AgapitoAinda não há avaliações

- Best of SketchessDocumento45 páginasBest of SketchessAlejandro Torres PorrasAinda não há avaliações

- Size, Scale and Overall Proportion of Form, Basic Understanding of Various Shapes, Inter-Relationship of Visual FormsDocumento17 páginasSize, Scale and Overall Proportion of Form, Basic Understanding of Various Shapes, Inter-Relationship of Visual FormsJabbar AljanabyAinda não há avaliações

- Basic DrawingDocumento17 páginasBasic DrawingMaridel FloridaAinda não há avaliações

- Lesson 2: DrawingDocumento34 páginasLesson 2: DrawingAvrilAinda não há avaliações

- How To Draw A Portrait in Three Quarter View, Part 5Documento10 páginasHow To Draw A Portrait in Three Quarter View, Part 5Soc Rua NguyenAinda não há avaliações

- Nature Drawing - To Study Form and Structure and Various Shapes Basic FormsDocumento32 páginasNature Drawing - To Study Form and Structure and Various Shapes Basic FormsJabbar AljanabyAinda não há avaliações

- Pictorial Drawing: Ivan T. Dolleson Instructor 1Documento47 páginasPictorial Drawing: Ivan T. Dolleson Instructor 1ivan dollesonAinda não há avaliações

- Sketching: Ms. Janice Magbujos-Florida Instructor IDocumento25 páginasSketching: Ms. Janice Magbujos-Florida Instructor ImythonyAinda não há avaliações

- Module 2 (Lesson 1) Id 1Documento3 páginasModule 2 (Lesson 1) Id 1Queenie Belle A. DuhaylongsodAinda não há avaliações

- 2art First Grading Educ Lesson 2 - Value and ColorDocumento102 páginas2art First Grading Educ Lesson 2 - Value and Colorapi-288938459Ainda não há avaliações

- Perpective and LineDocumento20 páginasPerpective and Linemario c. salvadorAinda não há avaliações

- How To Draw A Portrait in Three Quarter View, Part 7Documento9 páginasHow To Draw A Portrait in Three Quarter View, Part 7Soc Rua NguyenAinda não há avaliações

- One Point and Two Point Perspective Worksheet PacketDocumento20 páginasOne Point and Two Point Perspective Worksheet PacketAsia Winter-Sinnott100% (1)

- Watercolour TechniquesDocumento7 páginasWatercolour TechniquesJesmond TayAinda não há avaliações

- How To Draw A Portrait in Three Quarter ViewDocumento12 páginasHow To Draw A Portrait in Three Quarter ViewSoc Rua NguyenAinda não há avaliações

- Final Topics Drawing Perspectives: Methods of ConstructionDocumento9 páginasFinal Topics Drawing Perspectives: Methods of ConstructionNasrea Galmak Hadji Mohammad0% (1)

- PERSPETIVE - Three Point PerspectiveDocumento89 páginasPERSPETIVE - Three Point PerspectiveAdarsh PatilAinda não há avaliações

- 100 SketchbookpromptsDocumento3 páginas100 Sketchbookpromptsapi-341624585Ainda não há avaliações

- How To Draw A Portrait in Three Quarter View, Part 9Documento10 páginasHow To Draw A Portrait in Three Quarter View, Part 9Soc Rua NguyenAinda não há avaliações

- 2 Point PerspectiveDocumento16 páginas2 Point Perspectiveapi-261439685Ainda não há avaliações

- Perspective For 2d ArtDocumento48 páginasPerspective For 2d Artapi-293964578100% (2)

- Two Point Perspective-1Documento23 páginasTwo Point Perspective-1LaudeaaartAinda não há avaliações

- Line ArtDocumento37 páginasLine ArtJanine DefanteAinda não há avaliações

- 2-Point Perspective Tutorial: Creating A Simple Perspective GridDocumento5 páginas2-Point Perspective Tutorial: Creating A Simple Perspective Gridmemelo20% (1)

- LESSON 5 Drawing Lines, Curves, Arch, Ellipse and Circles. - Teachers ManualDocumento11 páginasLESSON 5 Drawing Lines, Curves, Arch, Ellipse and Circles. - Teachers ManualBarb Gonzales Acebedo100% (1)

- How Hovercrafts WorkDocumento10 páginasHow Hovercrafts WorkHarish VermaAinda não há avaliações

- Y 9 P 1 1stT F E 2023Documento14 páginasY 9 P 1 1stT F E 2023Josi BelaAinda não há avaliações

- Cbse Class - 6 SyllabusDocumento9 páginasCbse Class - 6 SyllabusAnkita SrivastavaAinda não há avaliações

- Cambridge IGCSE: Mathematics 0580/31Documento20 páginasCambridge IGCSE: Mathematics 0580/31Rehab NagaAinda não há avaliações

- Detailed Lesson Plan in Arts 2Documento6 páginasDetailed Lesson Plan in Arts 2Jeanrose CavanillaAinda não há avaliações

- SwordMaster Maya PDFDocumento101 páginasSwordMaster Maya PDFResiariPutriBatami100% (1)

- Published-Pdf-0140-6-Reviewing Visual Elements of Rhythm, Balance and Movement of Forms and Motifs in Filigree Work of Zanjan PDFDocumento9 páginasPublished-Pdf-0140-6-Reviewing Visual Elements of Rhythm, Balance and Movement of Forms and Motifs in Filigree Work of Zanjan PDFDaniel GoffAinda não há avaliações

- Grade 8 ArtsDocumento112 páginasGrade 8 ArtsHydee Samonte Trinidad100% (2)

- Archi Heritage and Seismic Design of TemplesDocumento6 páginasArchi Heritage and Seismic Design of TemplesJigyasushodhAinda não há avaliações

- Module 3 Math Topic 2 For UploadDocumento129 páginasModule 3 Math Topic 2 For UploadSan Rafael National HSAinda não há avaliações

- Turn, Flip Slide Resize: RotationDocumento8 páginasTurn, Flip Slide Resize: Rotationpatric bethelAinda não há avaliações

- Symmetry of 3d ShapesDocumento37 páginasSymmetry of 3d ShapesChidume Nonso100% (1)

- The-Self-Made-Tapestry-Pattern-Formation-in-Nature VVV PDFDocumento657 páginasThe-Self-Made-Tapestry-Pattern-Formation-in-Nature VVV PDFUčim Pref100% (2)

- Net of Cubes and CuboidsDocumento10 páginasNet of Cubes and CuboidsGilbert ContrerasAinda não há avaliações

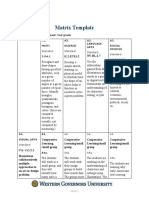

- Matrix Template: K-2-ETS1-2 NV - RL.2.7Documento15 páginasMatrix Template: K-2-ETS1-2 NV - RL.2.7Willie HarringtonAinda não há avaliações

- Vastu Software ManualDocumento109 páginasVastu Software ManualNaresh Muttavarapu100% (2)

- Art and Craft Guia de Primaria TEACHER S BOOKDocumento44 páginasArt and Craft Guia de Primaria TEACHER S BOOKFélix Bello Rodríguez40% (5)

- Jean Piaget Genetic EpistemologyDocumento88 páginasJean Piaget Genetic Epistemologyelhorimane16Ainda não há avaliações

- L2 - Let's Draw Shapes - Teacher Notes - British English PDFDocumento17 páginasL2 - Let's Draw Shapes - Teacher Notes - British English PDFdorinaAinda não há avaliações

- MATH3 Q3 Mod 8 SymmetryDocumento9 páginasMATH3 Q3 Mod 8 SymmetryLouie Raff Michael EstradaAinda não há avaliações

- Assignment 7Documento2 páginasAssignment 7Vaibhav ChaudharyAinda não há avaliações

- Book 7 Lesson 1Documento22 páginasBook 7 Lesson 1IsmaelAhmadAinda não há avaliações

- Mathematics For UsersDocumento222 páginasMathematics For UsersbongoherbertAinda não há avaliações

- Third Space Learning Enlargement GCSE WorksheetDocumento17 páginasThird Space Learning Enlargement GCSE Worksheetyxmi403Ainda não há avaliações

- Sacred Geometry 2023Documento49 páginasSacred Geometry 2023xAinda não há avaliações

- Contour Detection Using Freeman Chain CodeDocumento2 páginasContour Detection Using Freeman Chain CodelahariAinda não há avaliações

- Translation and Text Transfer موسوعة ترجماني - المترجم هاني البداليDocumento213 páginasTranslation and Text Transfer موسوعة ترجماني - المترجم هاني البداليLouti KhadrAinda não há avaliações

- Why Colors and Shapes MatterDocumento3 páginasWhy Colors and Shapes MatterAlifa ImamaAinda não há avaliações

- Packing Oblique 3D ObjectsDocumento16 páginasPacking Oblique 3D Objectsjojo sijoAinda não há avaliações

- Babao, Gwyneth M. (Melcs)Documento4 páginasBabao, Gwyneth M. (Melcs)Gwyneth BabaoAinda não há avaliações