Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

It's Ok, We'Re Not Cousins by Blood

Enviado por

Paul Miers0 notas0% acharam este documento útil (0 voto)

32 visualizações4 páginasCousin marriage

Título original

It’s Ok, We’Re Not Cousins by Blood

Direitos autorais

© © All Rights Reserved

Formatos disponíveis

PDF, TXT ou leia online no Scribd

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoCousin marriage

Direitos autorais:

© All Rights Reserved

Formatos disponíveis

Baixe no formato PDF, TXT ou leia online no Scribd

0 notas0% acharam este documento útil (0 voto)

32 visualizações4 páginasIt's Ok, We'Re Not Cousins by Blood

Enviado por

Paul MiersCousin marriage

Direitos autorais:

© All Rights Reserved

Formatos disponíveis

Baixe no formato PDF, TXT ou leia online no Scribd

Você está na página 1de 4

PLoS Biology | www.plosbiology.org PLoS Biology | www.plosbiology.

org 2627 December 2008 | Volume 6 | Issue 12 | e320

Historical and Philosophical Perspectives

I

n February, 2008, British

environment minister Phil Woolas

sparked a major row in the United

Kingdom when he attributed the high

rate of birth defects in the Pakistani

community to the practice of marriages

between first cousins. If you have a

child with your cousin, the likelihood

is therell be a genetic problem, he

told the Sunday Times [1]. Although

a Muslim activist group demanded

that Woolas be fired, he was instead

promoted in October to the racially

sensitive post of immigration minister.

Most of his constituents would surely

have shared Woolas view that the risk

to offspring from first-cousin marriage

is unacceptably highas would many

Americans. Indeed, in the United

States, similar assumptions about the

high level of genetic risk associated

with cousin marriage are reflected in

the 31 state laws that either bar the

practice outright or permit it only

where the couple obtains genetic

counseling, is beyond reproductive age,

or if one partner is sterile. When and

why did such laws become popular,

and is the sentiment that informs them

grounded in scientific fact?

US prohibitions on cousin

marriage date to the Civil War and

its immediate aftermath. The first

ban was enacted by Kansas in 1858,

with Nevada, North Dakota, South

Dakota, Washington, New Hampshire,

Ohio, and Wyoming following suit in

the 1860s. Subsequently, the rate of

increase in the number of laws was

nearly constant until the mid-1920s;

only Kentucky (1946), Maine (1985),

and Texas (2005) have since banned

cousins from marrying. (Several

other efforts ultimately failed when

bills were either vetoed by a governor

or passed by only one house of a

legislature; e.g., in 2000, the Maryland

House of Delegates approved a ban

by a vote of 82 to 46, but the bill died

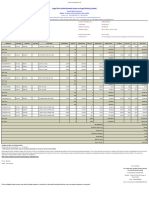

in the Senate.) The accompanying

map (Figure 1) illustrates both the

extent and the progress of legislation.

It demonstrates that western states

are disproportionately represented,

reflecting the fact that either as

territories or newly admitted states,

they were writing their marriage codes

from scratch and hence prompted to

explicitly confront the issue. For the

same reason, these states tended to be

the first to prohibit cousin marriage.

Perhaps surprisingly, these bans are

not attributable to the rise of eugenics.

Popular assumptions about hereditary

risk and an associated need to control

reproduction were widespread before

the emergence of an organized

eugenics movement around the turn

of the 20th century. Indeed, most

prominent American eugenists were, at

best, lukewarm about the laws, which

they thought both indiscriminate in

their effects and difficult to enforce

Its Ok, Were Not Cousins by Blood:

The Cousin Marriage Controversy

in Historical Perspective

Diane B. Paul, Hamish G. Spencer*

The Historical and Philosophical Perspectives series

provides professional historians and philosophers

of science with a forum to reflect on topical issues in

contemporary biology.

Series Editor: Evelyn Fox Keller, Massachusetts

Institute of Technology, United States of America

Citation: Paul DB, Spencer HG (2008) Its ok,

were not cousins by blood: The cousin marriage

controversy in historical perspective. PLoS Biol 6(12):

e320. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0060320

Copyright: 2008 Paul and Spencer. This is an

open-access article distributed under the terms

of the Creative Commons Attribution License,

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and

reproduction in any medium, provided the original

author and source are credited.

Diane B. Paul is Professor Emerita, Department of

Political Science, University of Massachusetts Boston,

Boston, Massachusetts and Research Associate,

Museum of Comparative Zoology, Harvard University,

Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States of America.

Hamish G. Spencer is Professor, Allan Wilson Centre

for Molecular Ecology and Evolution, National

Research Centre for Growth and Development,

Department of Zoology, University of Otago,

Dunedin, New Zealand.

* To whom correspondence should be addressed.

E-mail: h.spencer@otago.ac.nz

doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0060320.g001

Figure 1. Map of the United States Showing States with Laws Forbidding First-Cousin Marriage

Different colors reflect differences in the timing of passage of the laws. Colorado is shaded because

its law was repealed. White states never had such bans.

PLoS Biology | www.plosbiology.org PLoS Biology | www.plosbiology.org 2628 December 2008 | Volume 6 | Issue 12 | e320

[2]. In the view of many eugenists,

sterilization of the unfit would be a far

more effective means of improving the

race.

Nonetheless, in both the US and

Europe, the frequency of first-cousin

marriagea practice that had often

been favored, especially by elites

sharply declined during the second half

of the 19th century [3]. (The reasons

are both complex and contested, but

likely include improved transportation

and communication, which increased

the range of marriage partners; a

decline in family size, which limited the

number of marriageable cousins; and

greater female mobility and autonomy

[4,5].) The fact that no European

country barred cousins from marrying,

while many US states did and still do,

has often been interpreted as proof of

a special American animosity toward

the practice [6]. But this explanation

ignores a number of factors, including

the ease with which a handful of

highly motivated activistsor even

one individualcan be effective in

the decentralized American system,

especially when feelings do not run

high on the other side of an issue.

The recent Texas experience, where

a state representative quietly tacked

an amendment barring first-cousin

marriage onto a child protection bill, is

a case in point.

The laws must also be viewed in

the context of a new, postCivil War

acceptance of the need for state

oversight of education, commerce, and

health and safety, including marriage

and the family. Beginning in the 1860s,

many states passed anti-miscegenation

laws, increased the statutory age of

marriage, and adopted or expanded

medical and mental-capacity

restrictions in marriage law [7]. Thus,

laws prohibiting cousin marriage were

but one aspect of a more general

trend to broaden state authority in

areas previously considered private.

And unlike the situation in Britain

and much of Europe, cousin marriage

in the US was associated not with the

aristocracy and upper middle class but

with much easier targets: immigrants

and the rural poor. In any case, by the

late nineteenth century, in Europe as

well as the US, marrying ones cousin

had come to be viewed as reckless, and

today, despite its continued popularity

in many societies and among European

elites historically, the practice is highly

stigmatized in the West (and parts of

Asiathe Peoples Republic of China,

Taiwan, and both North and South

Korea also prohibit cousin marriage)

[811]. The ironic humor of a New

Zealand beer advertisement (Figure 2)

nicely reflects current opinion in much

of the world. But is the practice as risky

as many people assume?

Until recently, good data on which

to base an answer were lacking. As a

result, great variation existed in the

medical advice and screening services

offered to consanguineous couples

[12]. In an effort at clarification, the

National Society of Genetic Counselors

(NSGC) convened a group of experts

to review existing studies on risks to

offspring and issue recommendations

for clinical practice. Their report

concluded that the risks of a first-cousin

union were generally much smaller

than assumedabout 1.7%2% above

the background risk for congenital

defects and 4.4% for pre-reproductive

mortalityand did not warrant any

special preconception testing. In

the authors view, neither the stigma

that attaches to such unions in North

America nor the laws that bar them

were scientifically well-grounded.

When dealing with worried clients, the

authors advised genetic counselors to

normalize such unions by discussing

their high frequency in some parts

of the world and providing examples

of prominent cousin couples, such as

Charles Darwin and Emma Wedgwood

[13].

In the aftermath of controversies

ignited by Woolass comments and

similar remarks in 2005 by Labour

Member of Parliament Ann Cryer, who

asserted We have to stop this tradition

of first cousin marriages [14,15], the

NSGC report was cited by numerous

scientific, legal, and lay commentators

as testament to the low risk of cousin

marriage and hence the lack of any

compelling biological reason to avoid

it. (Literally dozens of authors also

asserted that the Darwins had ten

healthy childrendespite the deaths of

three of them in infancy or childhood

and Charles Darwins own worries

that consanguinity had affected the

health and fertility of the intermarried

Darwin and Wedgwood families,

and of his and Emmas offspring in

particular [2,16].) Although the report

warned against generalizing from

(and hence by implication to) more

inbred populations, many writers,

roughly averaging the statistics for birth

defects and pre-reproductive mortality,

noted that first-cousin marriage only

increases the risk of adverse events by

about 3%. But for several reasons, any

overall calculation of risk is in fact quite

complicated.

First, even assuming that the

deleterious phenotype arises solely

from homozygosity at a single locus,

the increased risk depends on the

frequency of the allele involved; it is

not an immediate consequence of

the degree of relatedness between

cousins. (Interestingly, despite the

British biometricians harsh criticism

of Mendelism, they were the first to

describe this dependency in 1911

[17,18].) If a deleterious recessive

allele has a frequency q, the ratio of the

recessive phenotype in the offspring

of first cousins relative to a panmictic

population is (1 + 15q)/16q, which

means the increase in risk is greater

for rarer conditions [19]. For example,

if q is 0.01, the ratio is 7.2; if q is 0.001,

it is 63.4. Consequently, statistics

on the risks associated with cousin

marriage are necessarily averages across

many traits, and they are likely to be

different for different populations,

which will often vary in the frequency

of particular deleterious alleles. In

the Pakistani immigrant population,

for example, the quoted high average

rate of birth defects may mask a single

trait (or small number of traits) at

very high frequency, a situation with

different medical consequences from

one characterized by a larger number

of less-frequent disorders.

Second, children of cousin

marriages are likely to manifest an

increased frequency of birth defects

showing polygenic inheritance and

interacting with environmental

variation. But as the NSGC report

notes, calculating the increased

frequency of such quantitative traits

doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0060320.g002

Figure 2. A Beer Advertisement from New

Zealand, Part of a Humorous Series

PLoS Biology | www.plosbiology.org PLoS Biology | www.plosbiology.org 2629 December 2008 | Volume 6 | Issue 12 | e320

is not straightforward, and properly

controlled studies are lacking.

Moreover, socio-economic and other

environmental influences will vary

among populations, which can easily

confound the effects of consanguinity.

Inbred populations, including British

Pakistanis, are often poor. The mother

may be malnourished to begin with,

and families may not seek or have

access to good prenatal care, which may

be unavailable in their native language

[20]. Hence it is difficult to separate

out genetic from socio-economic and

other environmental factors.

Third, as the report also notes, the

degree of increased risk depends on

the mean coefficient of inbreeding

for the population. That is, whether

first-cousin marriage is an occasional

or regular occurrence in the study

population matters, and it is thus

inappropriate to extrapolate findings

from largely outbred populations with

occasional first-cousin marriages to

populations with high coefficients of

inbreeding and vice-versa. Standard

calculations, such as the commonly

cited 3% additional risk, examine

a pedigree in which the ancestors

(usually grandparents) are assumed

to be unrelated. In North America,

marriages between consanguineal kin

are strongly discouraged. But such an

assumption is unwarranted in the case

of UK Pakistanis, who have emigrated

from a country where such marriage is

traditional and for whom it is estimated

that roughly 55%59% of marriages

continue to be between first cousins

[2123]. Thus, the usual risk estimates

are misleading: data from the English

West Midlands suggest that British

Pakistanis account for only ~4.1% of

births, but about 33% of the autosomal

recessive metabolic errors recorded at

birth [24]. However, for a variety of

reasons (including fear that a cousin

marriage would result in their being

blamed for any birth defects), UK

Pakistanis are less likely to use prenatal

testing and to terminate pregnancies

[20,25]. Thus the population

attributable risk of genetic diseases at

birth due to inbreeding may be skewed

by prenatal elimination of affected

fetuses in non-inbred populations.

Moreover, the consequences of

prolonged inbreeding are not always

obvious. The uniting of deleterious

recessives by inbreeding may also lead

to these alleles being purged from

the population. The frequency of

such deleterious alleles, then, may be

decreased, which (as shown above)

means the relative risk is greater, even as

the absolute risk decreases.

For all these reasons, the increased

population-level genetic risks arising

from cousin marriage can only be

estimated empirically, and those

estimates are likely to be specific to

particular populations in specific

environments. And of course for

particular couples, the risks depend

on their individual genetic makeup.

It is also worth noting that both the

increased absolute and relative risk

may be relevant to assessing the

consequences of consanguineous

marriage. If the background risk of a

particular genetic disorder were one

in a million, a ten-fold increase in

relative risk would likely be considered

negligible, because the absolute

increase is nevertheless minuscule.

Conversely, the doubling of an absolute

risk of 10% would surely be considered

unacceptable. But the doubling of

a background 3% risk may fall on a

borderline, with the increase capable of

being framed as either large or small.

In any case, different commentators

have certainly interpreted the same risk

of cousin marriage as both insignificant

and as alarmingly high.

Those who characterize it as slight

usually describe the risk in absolute

terms and compare it with other risks

of the same or greater magnitude that

are generally considered acceptable.

Thus it is often noted that women over

the age of 40 are not prevented from

childbearing, nor is anyone suggesting

they should be, despite an equivalent

risk of birth defects. Indeed, the

argument goes, we do not question

the right of people with Huntington

disease or other autosomal dominant

disorders to have children, despite a

50% risk to offspring [2629]. On the

other hand, those who portray the risk

as large tend to describe it in relative

terms. For example, geneticist Philip

Reilly commented: A 7 to 8% chance

is 50% greater than a 5% chance.

Thats a significant difference. They

also tend to compare the risk with

others that are generally considered

unacceptable. Thus a doctor asks

(rhetorically): Would anyone

knowingly take a medication that has

double the risk of causing permanent

brain damage? [30,31].

In closing, we note that laws barring

cousin marriage use coercive means

to achieve a public purpose and thus

would seem to qualify as eugenics even

by the most restrictive of definitions.

That they were a form of eugenics

would once have been taken for

granted. Thus J.B.S. Haldane argued

that discouraging or prohibiting cousin

marriage would appreciably reduce

the incidence of a number of serious

recessive conditions, and he explicitly

characterized measures to do so as

acceptable forms of eugenics [32]. But

Haldane wrote before eugenics itself

became stigmatized. Today, the term

is generally reserved for practices we

intend to disparage. That laws against

cousin marriage are generally approved

when they are thought about at all

helps explain why they are seemingly

exempt from that derogatory label.

It is obviously illogical to condemn

eugenics and at the same time favor

laws that prevent cousins from

marrying. But we do not aim to indict

these laws on the grounds that they

constitute eugenics. That would

assume what needs to be proved that

all forms of eugenics are necessarily

bad. In our view, cousin marriage laws

should be judged on their merits.

But from that standpoint as well, they

seem ill-advised. These laws reflect

once-prevailing prejudices about

immigrants and the rural poor and

oversimplified views of heredity,

and they are inconsistent with our

acceptance of reproductive behaviors

that are much riskier to offspring. They

should be repealed, not because their

intent was eugenic, but because neither

the scientific nor social assumptions

that informed them are any longer

defensible.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Richard Lewontin,

Museum of Comparative Zoology (MCZ),

Harvard University, for hosting Hamish

Spencer during a sabbatical visit. Invaluable

assistance in researching the history of

American state statutes was provided by

Mindy Roseman of Harvards Law School

and Terri Gallego ORourke of its Langdell

Law Library. Our efforts to locate and

interpret Asian legislation were assisted

by William Alford and librarian Nongii

Zhang at the Law School, by Mikyung

Kang and Wang Le (visiting from Fudan

University) at the Yenching Library, and

Jennifer Thomson of the MCZ. We are also

deeply grateful to Ken Miller of the Zoology

Department, University of Otago, for

PLoS Biology | www.plosbiology.org PLoS Biology | www.plosbiology.org 2630 December 2008 | Volume 6 | Issue 12 | e320

drawing the map; to Honor Dillon, Assistant

Brand Manager Tui, for permission to use

the Tui ad; and to Robert Resta, Swedish

Hospital, Seattle, for providing detailed

comments on a draft of the manuscript, thus

saving us from at least some errors.

Funding. This work was supported by the

Allan Wilson Centre for Molecular Ecology

and Evolution, which funded DBPs visit to

the University of Otago.

References

1. BBC News (2008) Birth defects warning sparks

row. Available: http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/

uk_news/7237663.stm. Accessed 17 September

2008.

2. Paul DB, Spencer HG (2008) Eugenics

without eugenists? Anglo-American critiques

of cousin marriage in the nineteenth and

early twentieth centuries. In: Mller-Wille S,

Brandt C, Rheinberger H-J, editors. Heredity

explored: Between public domain and

experimental science, 1850-1930. Cambridge

(Massachusetts): MIT Press. In press.

3. Sabean D (2007) From clan to kindred:

Kinship and the circulation of property in

premodern and modern Europe. In: Mller-

Wille S, Rheinberger H-J, editors. Heredity

produced: At the crossroads of biology,

politics, and culture, 1500-1870. Cambridge

(Massachusetts): MIT Press. pp. 37-59.

4. Anderson NF (1986) Cousin marriage in

Victorian England. J Family History 11: 285-

301.

5. Kuper A (2002). Incest, cousin marriage, and

the origin of the human sciences in nineteenth-

century England. Past and Present 174: 158-

183.

6. Ottenheimer M (1996) Forbidden relatives:

The American myth of cousin marriage.

Urbana: University of Chicago Press. 179 p.

7. Grossberg M (1985) Governing the hearth: Law

and the family in nineteenth-century America.

Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

417 p.

8. Marriage law of the Peoples Republic of

China; chapter II, marriage contract (2001)

Available: http://english.gov.cn/laws/2005-

09/25/content_70022.htm. Accessed 17

September 2008.

9. Law and regulations database of the Republic

of China [Taiwan]. Civil code part IV family.

Article 983 (19980617). As amended June 26,

2002. Available: http://law.moj.gov.tw/Eng/

Fnews/FnewsContent.asp?msgid=740&msgT

ype=en&keyword=civil+code+Part+IV+family.

Accessed 17 September 2008.

10. Hanguk minpo*pcho*n [South Korean civil

code], article 809

11. Choson Minjujuui Inmin Konghwaguk

Kojokpop [Peoples Republic of Korea family

law], article 10.

12. Bennett RL, Hudgins L, Smith CO, Motulsky

AG (1999) Inconsistencies in genetic

counseling and screening for consanguineous

couples and their offspring: The need for

practice guidelines. Genet Med 1: 286-292.

13. Bennett RL, Motulsky AG, Hudgins L, et al.

(2002) Genetic counseling and screening of

consanguineous couples and their offspring:

Recommendations of the National Society of

Genetic Counselors. J Genet Couns 11: 97-119.

14. Rowlatt J (2005) The risks of cousin marriage.

BBC News. Available: http://news.bbc.

co.uk/2/hi/programmes/newsnight/4442010.

stm. Accessed 17 September 2008.

15. Dyer O (2005) MP is criticised for saying that

marriage of first cousins is a health problem.

BMJ 331: 1292. Available: http://bmj.com/

cgi/content/full/331/7528/1292. Accessed 17

September 2008.

16. Moore J (2005) Good breeding: Darwin

doubted his own familys fitness. Natural

History 114: 45-46.

17. Jacobs SM (1911) Inbreeding in a stable simple

Mendelian population with special reference

to cousin marriage. Proc R Soc Lond Ser B 24:

23-42.

18. Elderton EM (1911) On the marriage of first

cousins. Eugenics Laboratory lecture series 4.

London: Dulau and Co.

19. Crow JF, Kimura M (1970) An introduction to

population genetic theory. New York: Harper

& Row. p. 74.

20. Shaw A (2005) Attitudes to genetic diagnosis

and to the use of medical technologies in

pregnancy: Some British Pakistani perspectives.

In: Unnithan-Kumar M, editor. Reproductive

agency, medicine and the State: Cultural

transformations in childbearing. Oxford:

Berghahn Books. pp. 25-42.

21. Hussain R, Bittles AH (1998) The prevalence

and demographic characteristics of

consanguineous marriages in Pakistan. J Biosoc

Sci 30: 261-279.

22. Darr A, Modell B (1988) The frequency of

consanguineous marriage among British

Pakistanis. J Med Genet 25: 186-190.

23. Shaw A (2001) Kinship, cultural preference

and immigration: Consanguineous marriage

among British Pakistanis. J Roy Anthrop Inst

7: 315-334.

24. Hutchesson ACJ, Bundey S, Preece MA, Hall

SK, Green A (1998) A comparison of disease

and gene frequencies of inborn errors of

metabolism among different ethnic groups

in the West Midlands, UK. J Med Genet 35:

366-370.

25. Shaw A, Hurst JA (2008) What is this genetics,

anyway? Understandings of genetics, illness

causality and inheritance among British

Pakistani users of genetic services. J Genet

Counsel 17: 373-383.

26. Grossman J (2002) Should the law be kinder

to kissin cousins?: A genetic report should

cause a rethinking of incest laws. FindLaw.

Available: http://writ.news.findlaw.com/

grossman/20020408.html. Accessed 17

September 2008.

27. Savage D (2007) Cousins marrying cousins.

Available: http://chemistry.typepad.com/the_

great_mate_debate/2007/08/cousins-marryin.

html. Accessed 17 September 2008.

28. King E (2002) Evolutions greatest advocate

did it, so why all the fuss over kissing cousins?

The Age (Melbourne, Australia). May 27, 2002.

p. 4.

29. Grady D (2002 April 4) Few risks seen to the

children of 1st cousins. The New York Times.

p. 1.

30. Willing R (2002 April 4) Research downplays

risk of cousin marriages. USA Today. p. 3A.

31. Gilliam M (2002 April 8) When cousins wed.

Letter to the editor. The New York Times. p.

A18.

32. Haldane JBS (1938) Heredity and politics. G.

Allen & Unwin ltd. pp. 89-91.

Você também pode gostar

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- Dispersion08 Seth PriceDocumento21 páginasDispersion08 Seth PriceaymerictaAinda não há avaliações

- Post Colonial Studies and The Discourse of Foucault: Survey of A Field of ProblematizationDocumento34 páginasPost Colonial Studies and The Discourse of Foucault: Survey of A Field of ProblematizationPaul MiersAinda não há avaliações

- Putting Knowledge To Work and Letting Information PlayDocumento290 páginasPutting Knowledge To Work and Letting Information PlayPaul MiersAinda não há avaliações

- Deleuze's Postscript On The Societies of ControlDocumento7 páginasDeleuze's Postscript On The Societies of ControlPaul MiersAinda não há avaliações

- Hito Steyerl, "A Thing Like You and Me"Documento7 páginasHito Steyerl, "A Thing Like You and Me"Paul MiersAinda não há avaliações

- L10021 CatalogueDocumento430 páginasL10021 CataloguePaul MiersAinda não há avaliações

- Constraint Interaction II: OT: - Strict Domination - "Grammars Can't Count"Documento6 páginasConstraint Interaction II: OT: - Strict Domination - "Grammars Can't Count"Paul MiersAinda não há avaliações

- CLST 307-1Documento1 páginaCLST 307-1Paul MiersAinda não há avaliações

- ICS Architecture (25 Slides)Documento26 páginasICS Architecture (25 Slides)Paul MiersAinda não há avaliações

- Afro Modern: Journeys Through The Black AtlanticDocumento22 páginasAfro Modern: Journeys Through The Black AtlanticPaul MiersAinda não há avaliações

- Visual CultureDocumento45 páginasVisual CulturePaul Miers67% (6)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (400)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (895)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (266)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (345)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (121)

- 7th Officers Meeting July 3, 2022Documento7 páginas7th Officers Meeting July 3, 2022Barangay CentroAinda não há avaliações

- Code of Ethics For Company SecretariesDocumento2 páginasCode of Ethics For Company SecretariesNoorazian NoordinAinda não há avaliações

- PS Vita VPK SuperArchiveDocumento10 páginasPS Vita VPK SuperArchiveRousseau Pierre LouisAinda não há avaliações

- 25 ConstituencyWiseDetailedResultDocumento197 páginas25 ConstituencyWiseDetailedResultdeepa.haas5544Ainda não há avaliações

- Angel One Limited (Formerly Known As Angel Broking Limited) : (Capital Market Segment)Documento1 páginaAngel One Limited (Formerly Known As Angel Broking Limited) : (Capital Market Segment)Kirti Kant SrivastavaAinda não há avaliações

- Belgian Overseas Vs Philippine First InsuranceDocumento6 páginasBelgian Overseas Vs Philippine First InsuranceMark Adrian ArellanoAinda não há avaliações

- Handbook For Coordinating GBV in Emergencies Fin.01Documento324 páginasHandbook For Coordinating GBV in Emergencies Fin.01Hayder T. RasheedAinda não há avaliações

- Torture 2009Documento163 páginasTorture 2009Achintya MandalAinda não há avaliações

- CPC Assignment 1Documento7 páginasCPC Assignment 1Maryam BasheerAinda não há avaliações

- Isa Na Lang para Mag 100Documento5 páginasIsa Na Lang para Mag 100Xave SanchezAinda não há avaliações

- Isenhardt v. Real (2012)Documento6 páginasIsenhardt v. Real (2012)Orlhee Mar MegarbioAinda não há avaliações

- International Hotel vs. JoaquinDocumento28 páginasInternational Hotel vs. JoaquinJosine Protasio100% (1)

- Maths QuestionsDocumento5 páginasMaths QuestionsjayanthAinda não há avaliações

- Arigo V SwiftDocumento21 páginasArigo V SwiftKristine KristineeeAinda não há avaliações

- The Solicitor General For Plaintiff-Appellee. Dakila F. Castro & Associates For Accused-AppellantDocumento6 páginasThe Solicitor General For Plaintiff-Appellee. Dakila F. Castro & Associates For Accused-AppellantEmily MontallanaAinda não há avaliações

- 2 People vs. Galacgac CA 54 O.G. 1027, January 11, 2018Documento3 páginas2 People vs. Galacgac CA 54 O.G. 1027, January 11, 2018Norbert DiazAinda não há avaliações

- Macedonians in AmericaDocumento350 páginasMacedonians in AmericaIgor IlievskiAinda não há avaliações

- Objectives: by The End of This Lesson, We WillDocumento17 páginasObjectives: by The End of This Lesson, We WillAlyssa Coleen Patacsil DoloritoAinda não há avaliações

- BasicBuddhism Vasala SuttaDocumento4 páginasBasicBuddhism Vasala Suttanuwan01Ainda não há avaliações

- PPG12 - Q2 - Mod10 - Elections and Political Parties in The PhilippinesDocumento14 páginasPPG12 - Q2 - Mod10 - Elections and Political Parties in The PhilippinesZENY NACUAAinda não há avaliações

- Castle On The HillDocumento6 páginasCastle On The HillEmilia Scarfo'Ainda não há avaliações

- Consti 2 Syllabus 2021Documento17 páginasConsti 2 Syllabus 2021Cookie MasterAinda não há avaliações

- Bank of Commerce v. Sps San Pablo, Jr.Documento13 páginasBank of Commerce v. Sps San Pablo, Jr.Cherish Kim FerrerAinda não há avaliações

- Riches v. Countrywide Home Loans Inc. Et Al - Document No. 3Documento1 páginaRiches v. Countrywide Home Loans Inc. Et Al - Document No. 3Justia.comAinda não há avaliações

- BulletDocumento5 páginasBulletStephen EstalAinda não há avaliações

- Sample Certificate of Authorship 1Documento2 páginasSample Certificate of Authorship 1Andy Myers100% (1)

- Judicial Affidavit - SampleDocumento5 páginasJudicial Affidavit - SampleNori Lola100% (4)

- Fotos Proteccion Con Malla CambiosDocumento8 páginasFotos Proteccion Con Malla CambiosRosemberg Reyes RamírezAinda não há avaliações

- Investigative Report of FindingDocumento34 páginasInvestigative Report of FindingAndrew ChammasAinda não há avaliações

- Chapter 27 - Summary & OutlineDocumento6 páginasChapter 27 - Summary & Outlinemirbramo100% (1)