Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

CE Byrd Leverman Nabors Aff Ghill Round1

Enviado por

DwaynetherocTítulo original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

CE Byrd Leverman Nabors Aff Ghill Round1

Enviado por

DwaynetherocDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Hark, thee, great horizon, and beyond to the endless seas. And so we explore.

One

does not explore the ocean to map the waters: one explores the ocean to map

themselves, to understand an innate pull to the desert island. The vigorous energy,

the uncertain force, the lan, of the ocean and its islands pulls us towards them:

succumbing to this pull is the first step of a great exploration.

Make no mistake: we explore the ocean in search of desert islands and we will find

them, for they have always been there, existing in two forms. In the first form we

project the island against the backdrop of nothingness, the immaculate island,

deserted only because we have drawn it up that way. The island takes its second form

immediately following as we populate it with the flora and fauna of our own inner

selves.

As we search for islands, they search back for us. We may find them, but somewhere

along the way we lose ourselves. Somewhere along the way the island, too,

transforms into something else. Much as the island represents the conflict between

sea and land, our exploration reveals that we too exist in conflict. Conflict with the

island, its seductive promise of isolation and freedom juxtaposed to the security of the

molar collective. As we drift within this tension, becoming takes place.

Deleuze 2004 (Gilles, "Desert Islands," Desert Islands and Other Texts (1953-1974), Semiotext(e),

Murray)

Geographers say there are two kinds of islands. This is valuable information for the imagination because it confirms what the imagination

already knew. Nor is it the only case where science makes mythology more concrete, and mythology makes science more vivid. Continental islands

are accidental, derived islands. They are separated from a continent, born of disarticulation, erosion, fracture;

they survive the absorption of what once contained them. Oceanic islands are originary, essential

islands. Some are formed from coral reefs and display a genuine organism. Others emerge from underwater

eruptions, bringing to the light of day a movement from the lowest depths. Some rise slowly; some disappear and then return,

leaving us no time to annex them. These two kinds of islands, continental and originary, reveal a profound

opposition between ocean and land. Continental islands serve as a reminder that the sea is on top of the earth, taking advantage of the

slightest sagging in the highest structures; oceanic islands, that the earth is still there, under the sea, gathering its strength to punch through to the surface. We

can assume that these elements are in constant strife, displaying a repulsion for one another. In this we

find nothing to reassure us. Also, that an island is deserted must appear philosophically normal to us. Humans cannot live, nor live

in security, unless they assume that the active struggle between earth and water is over, or at least contained.

People like to call these two elements mother and father, assigning them gender roles according to the whim of their fancy. They must somehow persuade

themselves that a struggle of this kind does not exist, or that it has somehow ended. In one way or another, the very existence of islands is the

negation of this point of view, of this effort, this conviction. That England is populated will always come as a surprise; humans can live

on an island only by forgetting what an island represents. Islands are either from before or for after

humankind. But everything that geography has told us about the two kinds of islands, the imagination

knew already on its own and in another way. The lan that draws humans toward islands extends the double movement that produces islands in

themselves. Dreaming of islandswhether with joy or in fear, it doesn't matteris dreaming of pulling away, of

being already separate, far from any continent, of being lost and aloneor it is dreaming of starting from scratch,

recreating, beginning anew. Some islands drifted away from the continent, but the island is also that toward

which one drifts; other islands originated in the ocean, but the island is also the origin, radical and absolute. Certainly, separating and creating are not

mutually exclusive: one has to hold one's own when one is separated, and had better be separate to create anew; nevertheless, one of the two tendencies always

predominates. In this way, the movement of the imagination of islands takes up the movement of their

production, but they don't have the same objective. It is the same movement, but a different goal. It is

no longer the island that is separated from the continent, it is humans who find themselves separated from the world when on an island. It is no longer

the island that is created from the bowels of the earth through the liquid depths, it is humans who

create the world anew from the island and on the waters. Humans thus take up for themselves both movements of the island

and are able to do so on an island that, precisely, lacks one kind of movement: humans can drift toward an island that is nonetheless originary, and they can create

on an island that has merely drifted away. On closer inspection, we find here a new reason for every island to be and remain in theory deserted. An island doesn't

stop being deserted simply because it is inhabited. While it is true that the movement of humans toward and on the island takes up the movement of the island

prior to humankind, some people can occupy the islandit is still deserted, all the more so, provided they are sufficiently, that is, absolutely separate, and provided

they are sufficient, absolute creators. Certainly, this is never the case in fact, though people who are shipwrecked approach such a condition. But for this to be the

case, we need only extrapolate in imagination the movement they bring with them to the island. Only in appearance does such a movement put an end to the

island's desertedness; in reality, it takes up and prolongs the lan that produced the island as deserted. Far from compromising it, humans bring the desertedness to

its perfection and highest point. In certain conditions which attach them to the very movement of things, humans do not put an end to desertedness, they make it

sacred. Those people who come to the island indeed occupy and populate it; but in reality, were they sufficiently separate, sufficiently creative, they would give the

island only a dynamic image of itself, a consciousness of the movement which produced the island, such that through them the island would in the end become

conscious of itself as deserted and unpeopled. The island would be only the dream of humans, and humans, the pure

consciousness of the island. For this to be the case, there is again but one condition: humans would have to reduce

themselves to the movement that brings them to the island, the movement which prolongs and takes

up the lan that produced the island. Then geography and the imagination would be one. To that question so

dear to the old explorers"which creatures live on deserted islands?"one could only answer: human beings live there

already, but uncommon humans, they are absolutely separate, absolute creators, in short, an Idea of humanity, a

prototype, a man who would almost be a god, a woman who would be a goddess, a great Amnesiac, a pure Artist, a

consciousness of Earth and Ocean, an enormous hurricane, a beautiful witch, a statue from the Easter Islands. There you have a human being who

precedes itself. Such a creature on a deserted island would be the deserted island itself, insofar as it

imagines and reflects itself in its first movement. A consciousness of the earth and ocean, such is the deserted island, ready to begin

the world anew. But since human beings, even voluntarily, are not identical to the movement that puts them on the

island, they are unable to join with the lan that produces the island; they always encounter it from

the outside, and their presence in fact spoils its desertedness. The unity of the deserted island and its inhabitant is thus

not actual, only imaginary, like the idea of looking behind the curtain when one is not behind it. More importantly, it is doubtful whether the

individual imagination, unaided, could raise itself up to such an admirable identity; it would require the collective imagination, what is most profound in it, i.e. rites

and mythology.

There is no name for the islands which draw us other than Death. The islands, the

world itself, appears once only to be reborn its death is inextricably sewn to life, and

it is this rebirth which creates meaning. The island is always death, always the re-

articulation of a second life transposed over the first, the projection over the map

which reveals the meaning of the first.

We must return to an imaginative model of the island. Welcome our exploration of

the ocean in search of desert islands as an affirmation of the subject constituted

throughout that search. Welcome the death of the first life as part of the inevitable

transformation to another. Do not affirm the first world, instead welcome the

process of its rebirth.

Deleuze 2004 (Gilles, "Desert Islands," Desert Islands and Other Texts (1953-1974), Semiotext(e),

Murray)

What must be recovered is the mythological life of the deserted island. However, in its very failure, Robinson gives us some indication: he first

needed a reserve of capital. In Suzanne's case, she was first and foremost separate. And neither the one nor the other could be part of a couple.

These three indications must be restored to their mythological purity. We have to get back to the movement of the

imagination that makes the deserted island a model, a prototype of the collective soul. First, it is true that

from the deserted island it is not creation but re-creation, not the beginning but a re-beginning that

takes place. The deserted island is the origin, but a second origin. From it everything begins anew. The

island is the necessary minimum for this re-beginning, the material that survives the first origin, the

radiating seed or egg that must be sufficient to re-produce everything. Clearly, this presupposes that the

formation of the world happens in two stages, in two periods of time, birth and re-birth, and that the

second is just as necessary and essential as the first, and thus the first is necessarily compromised,

born for renewal and already renounced in a catastrophe. It is not that there is a second birth because

there has been a catastrophe, but the reverse, there is a catastrophe after the origin because there

must be, from the beginning, a second birth. Within ourselves we can locate the source of such a

theme: it is not the production of life that we look for when we judge it to be life, but its

reproduction. The animal whose mode of reproduction remains unknown to us has not yet taken its place among living beings. It is not

enough that everything begin, everything must begin again once the cycle of possible combinations has come

to completion. The second moment does not succeed the first: it is the reappearance of the first when

the cycle of the other moments has been completed. The second origin is thus more essential than the

first, since it gives us the law of repetition, the law of the series, whose first origin gave us only

moments. But this theme, even more than in our fantasies, finds expression in every mythology. It is well known as the myth of the flood.

The ark sets down on the one place on earth that remains uncovered by water, a circular and sacred place, from which the world begins anew.

It is an island or a mountain, or both at once: the island is a mountain under water, and the mountain, an island that is still dry. Here we see

original creation caught in a re-creation, which is concentrated in a holy land in the middle of the ocean. This second origin of the world is more

important than the first: it is a sacred island. Many myths recount that what we find there is an egg, a cosmic egg. Since the island is a second

origin, it is entrusted to man and not to the gods. It is separate, separated by the massive expanse of the flood. Ocean and water

embody a principle of segregation such that, on sacred islands, exclusively female communities can

come to be, such as the island of Circe or Calypso. After all, the beginning started from God and from a

couple, but not the new beginning, the beginning again, which starts from an egg: mythological maternity is

often a parthenogenesis. The idea of a second origin gives the deserted island its whole meaning, the survival

of a sacred place in a world that is slow to re-begin. In the ideal of beginning anew there is something

that precedes the beginning itself, that takes it up to deepen it and delay it in the passage of time. The

desert island is the material of this something immemorial, this something most profound.

As we search for desert islands we lose ourselves, we die so we can be reborn on the

island. Not dissimilar from the survivor of a shipwreck reconstituting their lives on the

island, we retain parts of ourselves but others are cast away and others still are

transformed to become unrecognizable. Nothing about our bodies changes through

exploration, but the subjective I leading the charge is irrevocably altered

populated by all we encounter along the way.

Ballantyne 2007 (Andrew, Tectonic Cultures Research Group at Newcastle University , "Deleuze and

Guattari for Architects" 78-79, Murray)

Landscape reappears with another role in imaging the schizoanalytic subject, if a subject remains. Just as Lenz found himself in

machinic engagement with his surroundings, so that there was no sense of separateness between his self and the snowflakes, stars and

mountain peaks, so Deleuze and Guattari describe themselves as deserts, inhabited by concepts that wander across them and move on

their way, so they are being continually reconstituted and remade. We are deserts, said Deleuze but populated by

tribes, flora and fauna. We pass our time in ordering these tribes, arranging them in other ways, getting

rid of some and encouraging others to prosper. And all these clans, all these crowds, do not undermine the

desert, which is our very ascesis; on the contrary they inhabit it, they pass through it, over it. In Guattari there has

always been a sort of wild rodeo, in part directed against himself. The desert, experimentation on oneself, is our only

identity, our single chance for all the combinations which inhabit us. (Deleuze and Parnet, 1977, 11) The

individual here is explicitly seen as multiple and political, and the process of subjectification is presented as dynamic

and continuing, never as something that has reached or could reach a satisfactory conclusion. For Deleuze

and Guattari living is always a process of becoming, never of contemplating an achieved being. Deleuze

describes Guattari as a man of the group, of bands or tribes, and yet he is a man alone, a desert populated by all these groups and all his

friends, all his becomings (Deleuze and Parnet, 1977, 16). There is something of the fluidity of identity of the man of the crowd in

Edgar Allen Poes story, where the man participates in the identities of the various tribes and crowds that swarm through the city

(Ballantyne, 2005, 2049). He takes to an extreme, and embodies a principle in a way that only a fictional character can: the principle

that we are not formed in isolation, but socially, and we are constituted by way of ideas and practices that

do not originate in us but which pass through us and inhabit us and influence the things we do,

occasionally perhaps consciously, but for the most part without our having any particular awareness of it

happening. So the individual is seen as not so much a political entity as a politics (a micropolitics) populated

and engaged, harmonious or conflicted. The image is always of lines and intensities, intersecting planes and

multiple colours, atmospheres, flows never hard dry objects, bounded forms or clear contours. And the

face, this white screen/black hole assemblage, is a means of engaging with others, a way of putting into circulation certain sorts of

signification that our little parliament, our pandaemonium, feels will help it on its way.

Exploring the ocean is always death. Death of the domestic life, the family, the

familiar. Indeed, we are always dying, always in the process of losing one life and

beginning anew. Death resides in every moment, every intensity, and we risk death

every time we strike out for the islands beyond our comprehension. We welcome

these little deaths as a means of liberating the self from the death of fixed

subjectivity.

Deleuze and Guattari 1972, Anti-Oedipus, 330-39, Murray

But it seems that things are becoming very obscure, for what is this distinction between the experience of death and the model of death? Here

again, is it a death desire? A being-far-death? Or rather an investment of death, even if speculative? None of the above.

The experience of death is the most common of occurrences in the unconscious, precisely because it occurs

in life and for life, in every passage or becoming, in every intensity as passage or becoming. It is in the

very nature of every intensity to invest within itself the zero intensity starting from which it is

produced, in one moment, as that which grows or diminishes according to an infinity of degrees (as Klossowski

noted, "an afflux is necessary merely to signify the absence of intensity"). We have attempted to show in this respect how the relations of

attraction and repulsion produced such states, sensations, and emotions, which imply a new energetic conversion and form the third kind of

synthesis, the synthesis of conjunction. One might say that the unconscious as a real subject has scattered an apparent

residual and nomadic subject around the entire compass of its cycle, a subject that passes by way of all the

becomings corresponding to the included disjunctions: the last part of the desiring-machine, the adjacent part.

These intense becomings and feelings, these intensive emotions, feed deliriums and hallucinations. But in themselves, these

intensive emotions are closest to the matter whose zero degree they invest in itself. They control the unconscious experience of

death, insofar as death is what is felt in every feeling, what never ceases and never finishes

happening in every becoming-in the becoming-another-sex, the becoming-god, the becoming-a-

race, etc., forming zones of intensity on the body without organs. Every intensity controls within its

own life the experience of death, and envelops it. And it is doubtless the case that every

intensity is extinguished at the end, that every becoming itself becomes a becoming-death!

Death, then, does actually happen. Maurice Blanchot distinguishes this twofold nature dearly, these two irreducible aspects

of death; the one, according to which the apparent subject never ceases to live and travel as a One-"one never stops and never has done with

dying"; and the other, according to which this same subject, fixed as I, actually dies-which is to say it finally ceases to die

since it ends up dying, in the reality of a last instant that fixes it in this way as an I, all the while undoing the

intensity, carrying it back to the zero that envelops it. From one aspect to the other, there is not at all a personal deepening, but

something quite different: there is a return from the experience of death to the model of death, in the cycle of the

desiring-machines. The cycle is closed. For a new departure, since this I is another? The experience of death must have

given us exactly enough broadened experience, in order to live and know that the desiring-machines do not die.

And that the subject as an adjacent part is always a "one" who conducts the experience, not an I who receives the

model. For the model itself is not the I either, but the body without organs. And I does not rejoin the model without the

model starting out again in the direction of another experience. Always going from the model to the experience, and starting

out again, returning from the model to the experience, is what schizophrenizing death amounts to, the exercise of

the desiring-machines (which is their very secret, well understood by the terrifying authors). The machines tell us this, and make us live it,

feel it, deeper than delirium and further than hallucination: yes, the return to repulsion will condition other attractions, other functionings, the

setting in motion of other working parts on the body without organs, the putting to work of other adjacent parts on the periphery that have as

much a right to say One as we ourselves do. "Let him die in his leaping through unheard-of and unnamable

things: other horrible workers will come; they will begin on the horizons where the other

collapsed !"29 The Eternal Return as experience, and as the deterritorialized circuit of all the cycles of desire. How

odd the psychoanalytic venture is. Psychoanalysis ought to be a song of life, or else be worth nothing at all. It ought, practically, to teach us to

sing life. And see how the most defeated, sad .song of death emanates from it: eiapopeia. From the start, and because of his stubborn dualism

of the drives, Freud never stopped trying to limit the discovery of a subjective or vital essence of desire as libido. But when the dualism passed

into a death instinct against Eros, this was no longer a simple limitation, it was a liquidation of the libido. Reich did not go wrong here, and was

perhaps the only one to maintain that the product of analysis should be a free and joyous person, a carrier of the life flows, capable of carrying

them all the way into the desert and decoding them-even if this idea necessarily took on the appearance of a crazy idea, given what had

become of analysis. He demonstrated that Freud, no less than lung and Adler, had repudiated the sexual position: the fixing of the death

instinct in fact deprives sexuality of its generative role on at least one essential point, which is the genesis of anxiety, since this genesis becomes

the autonomous cause of sexual repression instead of its result; it follows that sexuality as desire no longer animates a social critique of

civilization, but that civilization on the contrary finds itself sanctified as the sale agency capable of opposing the death desire. And how. does. it

do this? By in principle turning death against death, by making this turned-back death (la mort ret

aurneev into a force of desire by putting it in the service of a pseudo life through an entire

culture of guilt feeling. There is no need to tell all over how psychoanalysis culminates in a theory of culture that takes up again the

age-old task of the ascetic ideal Nirvana, the cultural extract, judging life, belittling life, measuring life against death, and only retaining from life

what the death of death wants very much to leave us with - a sublime resignation. As Reich says, when psychoanalysis began to speak of Eros,

the whole world breathed a sigh of relief': one knew what this meant, and that everything was going to unfold within a mortified life, since

Thanatos was now the partner of Eros, for worse but also for better. Psychoanalysis becomes the training ground of a new kind of priest, the

director of bad conscience: bad conscience has made us sick, but that is what will cure us! Freud did not hide what was really at

issue with the introduction of the death instinct: it is not a question of any fact whatever, but merely of a principle, a question of principle. The

death instinct is pure silence, pure transcendence, not givable and not given in experience. This very point IS remarkable:

It IS because death, according to Freud, has neither a model nor an experience, that he makes of it a transcendent principle."! So that the

psychoanalysts who refused the death instinct did so for the same reasons as those who accepted it: some said that there was no death instinct

since there was no model or experience in the unconscious; others, that there was a death instinct precisely because there was no model or

experience. We say, to the contrary, that there is no death instinct because there is both the model and the experience of

death in the unconscious. Death then is a part of the desiring-machine, a part that must itself be judged, evaluated

in the functioning of the machine and the system of its energetic conversions, and not as an abstract principle. If

Freud needs death as a principle, this is by virtue of the requirements of the dualism that maintains a qualitative opposition between the drives

(you will not escape the conflict): once the dualism of the sexual drives and the ego drives has only a topological scope, the qualitative or

dynamic dualism passes between Eros and Thanatos. But the same enterprise is continued and reinforced-

eliminating the machinic element of desire, the desiring-machines. It is a matter of eliminating the

libido, insofar as it implies the possibility of energetic conversions in the machine (Libido-Nurnen-Voluptas). It is a

matter of imposing the idea of an energetic duality rendering the machinic transformations impossible, with

everything obliged to pass by way of an indifferent neutral energy, that energy emanating from Oedipus and capable of being

added to either of the two irreducible forms neutralizing, mortifying life.* The purpose of the topological and dynamic dualities is to thrust

aside the point of view of functional multiplicity that alone is economic. (Szondi situates the problem clearly: why two kinds of drives qualified

as molar, functioning mysteriously, which is to say Oedipally, rather than n genes of drives-eight molecular genes, for example-functioning

machinically") If one looks in this direction for the ultimate reason why Freud erects a transcendent death instinct as a principle, the reason will

be found in Freud's practice itself. For if the principle has nothing to do with the facts, it has a lot to do with the psychoanalyst's conception of

psychoanalytic practice, a conception the psychoanalyst wishes to impose. Freud made the most profound discovery of the abstract subjective

essence of desire-Libido. But since he re-alienated this essence, reinvesting it in a subjective system of representation of the ego, and since he

receded this essence on the residual territoriality of Oedipus and under the despotic signifier of castration, he could no longer conceive the

essence of life except in a form turned back against itself, in the form of death itself. And this neutralization, this turning against life, is also the

last way in which a depressive and exhausted libido can go on surviving, and dream that it is surviving: "The ascetic ideal is an

artifice for the preservation of life ... even when he wounds himself, this master of destruction, of

self-destructing-the very wound itself compels him to live. . . ."32 It is Oedipus, the marshy earth, that

gives off a powerful odor of decay and death; and it is castration, the pious ascetic wound, the

signifier, that makes of this death a conservatory for the Oedipal life . Desire is in itself not a

desire to love, but a force to love, a virtue that gives and produces, that engineers. (For how

could what is in life still desire life? Who would want to call that a desire?) But desire must turn back against itself

in the name of a horrible Ananke, the Ananke of the weak and the depressed, the contagious neurotic

Ananke; desire must produce its shadow or its monkey, and find a strange artificial force for vegetating in the void, at the heart of its own

Jack. For better days to come? It must-but who talks in this way? What abjectness-become a desire to be loved, and worse, a sniveling desire to

have been loved, a desire that is reborn of its own frustration: no, daddy-mommy didn't love me enough. Sick desire stretches out on the

couch, an artificial swamp, a little earth, a little mother. "Look at you, stumbling and staggering with no use in your legs .... And it's nothing but

your wanting to be loved which does it. A maudlin crying to be loved, which makes your knees go all ricky."33 Just as there are two stomachs

for the ruminant, there must also exist two abortions, two castrations for sick desire: once in the family, in the familial scene, with the knitting

mother; another time in an asepticized clinic, in the psychoanalytic scene, with specialist artists who know how to handle the death instinct and

"bring off" castration, "bring off" frustration.

All sailors welcome death. All sailors side with death. Given sufficient time the ocean

can and will absorb us all. The sailor recognizes the inevitability of their return to the

ocean. We find joy in this inevitability, and from the certainty of our own deaths

emerges bountiful value. We affirm the certainty in the deaths which result from

exploration, both the little deaths inherent in every becoming and the one true death

in which we return to the loam.

McGowan 13 (Todd, Assoc. Prof. of Film and Television Studies @ U. of Vermont, Enjoying What We

Dont Have: The Political Project of Psychoanalysis, pp. 223-227)

On the level of common sense, this opposition is not symmetrical. What thinking person would not want to side with

those who love life rather than death.3 Everyone can readily understand how one might love life, but the love of death is a

counterintuitive phenomenon. It seems as if it must be code language for some other desire, which is how Western leftists often view it.

Interpreting terrorist attacks as an ultimately life-affirming response to imperialism and

impoverishment, they implicitly reject the possibility of being in love with death. But this type of

interpretation can't explain why so many suicide bombers are middle-class, educated subjects and not

the most downtrodden victims of imperialist power. 4 We must imagine that for subjects such as these there

is an appeal in death itself. Those who emphasize the importance of death at the expense of life do so because death is the

source of value.5 The fact that life has an end, that we do not have an infinite amount of time to experience every possibility,

means that we must value some things above others. Death creates hierarchies of value, and these

hierarchies are not only vehicles for oppression but the pathways through which what we do matters

at all. Without the value that death provides, neither love nor ice cream nor friendship nor anything

that we enjoy would have any special worth whatsoever. Having an infinite amount of time, we would

have no incentive to opt for these experiences rather than other ones. We would be left unable to

enjoy what seems to make life most worth living. Even though enjoyment itself is an experience of the

infinite, an experience of transcending the limits that regulate everyday activity, it nonetheless depends on the limits of

finitude. When one enjoys, one accesses the infinite as a finite subject, and it is this contrast that renders

enjoyment enjoyable. Without the limits of finitude, our experience of the infinite would become as tedious as our everyday lives (and in fact

would become our everyday experience). Finitude provides the punctuation through which the infinite emerges as such. The struggle to

assert the importance of death the act of being in love with death, as bin Laden claims that the Muslim youths are

is a mode of avowing ones allegiance to the infinite enjoyment that death doesn't extinguish but

instead spawns.6 This is exactly why Martin Heidegger attacks what he sees as our modern inauthentic relationship to death. In

Being and Time Heidegger sees our individual death as an absolute limit that has the effect of creating value

for us. As he puts it, "With death, Dasein stands before itself in its ownmost potentiality-for-being. This is a possibility in which the issue is

nothing less than Dasein's Being-in-the-world.7 Without the anticipation of our own death, we flit through the world and fail to take up fully

an attitude of care, the attitude most appropriate for our mode of being, according to Heidegger. Nothing really matters to those who have not

recognized the approach of their own death. By depriving us of an authentic relationship to death, an ideology that

proclaims life as the only value creates a valueless world where nothing matters to us. But of course

the partisans of life are not actually eliminating death itself. They simply privilege life over death and

see the world in terms of life rather than death, which would seem to leave the value-creating power of death

intact. But this is not what happens. By privileging life and seeing death only in terms of life, we

change the way we experience the world. Without the mediation that death provides, the system of

pure life becomes a system utterly bereft of value.8 We can see this in the two great systems of modernity science and

capitalism. Both modern science and capitalism are systems structured around pure life.9 Neither

recognizes any ontological limit but instead continually embarks on a project of constant change and

expansion. The scientific quest for knowledge about the world moves forward without regard for humanitarian or ethical concerns, which

is why ethicists incessantly try to reconcile scientific discoveries with morality after the fact. After scientists develop the ability to clone, for

instance, we realize what cloning portends for our sense of identity and attempt to police the practice. After Oppenheimer helps to

develop the atomic bomb, he addresses the world with pronouncements of its evil. But this rearguard

action has nothing to do with science as such. Oppenheimer the humanist is not Oppenheimer the

scientist.10 The same dynamic is visible with capitalism. As an economic system, it promotes constant evolution and

change just as life itself does. Nothing can remain the same within the capitalist world because the production of value depends on the creation

of the new commodity, and even the old commodities must be constantly given new forms or renewed in some way.11 Capitalism

produces crises not because it can't produce enough crises of scarcity dominate the history of the

noncapitalist world, not the capitalist one but because it produces too much. The crisis of capitalism is always

a crisis of overproduction. The capitalist economy suffocates from too much life, from excess, not from

scarcity or death. Both science and capitalism move forward without any acknowledged limit, which is why they are synonymous with

modernity.12 Modernity emerges with the bracketing of death's finitude and the belief that there is no barrier to human possibility. The

problem with the exclusive focus on life at the expense of death is that it never finds enough life and thus remains perpetually dissatisfied.

The limit of this project is, paradoxically, its own infinitude. It evokes what Hegel calls the bad infinite an infinite that is

wrongly conceived as having no relation at all to the finite. We succumb to the bad infinite when we pursue an

unattainable object and fail to see that the only possible satisfaction rests in the pursuit itself. The

bad infinite -the infinite of modernity- depends on a fundamental misrecognition. We continue on this path only as long

as we believe that we might attain the final piece of the puzzle, and yet this piece is constitutively denied us by the structure of the system

itself. We seek the commodity that would finally bring us complete satisfaction, but dissatisfaction is

built into the commodity structure, just as obsolescence is built into the very fabric of our cars and computers. Like capitalism,

scientific inquiry cannot find a final answer: beneath atomic theory we find string theory, and beneath

string theory we find something else. In both cases, the system prevents us from recognizing where our satisfaction

lies; it diverts our focus away from our activity and onto the goal that we pursue. In this way, modernity produces the dissatisfaction that

keeps it going. But it also produces another form of dissatisfaction that wants to arrest its forward movement. The further the project

of modernity moves in the direction of life, the more forcefully the specter of fundamentalism will

make its presence felt. The exclusive focus on life has the effect of producing eruptions of death. As the

life-affirming logic of science and capitalism structures all societies to an increasing extent, the space for the creation of value

disappears. Modernity attempts to construct a symbolic space where there is no place for death and the limit that death represents. As

opposed to the closed world of traditional society, modernity opens up an infinite universe.14 But this infinite universe is

established through the repression of finitude. Explosions of fundamentalist violence represent the

return of what modernity's symbolic structure cannot accommodate. As Lacan puts it in his seminar on psychosis,

"Whatever is refused in the symbolic order, in the sense of Verwerfung, reappears in the real.15 Fundamentalist violence is

blowback not simply in response to imperialist aggression, as the leftist common sense would have it.

This violence marks the return of what modernity necessarily forecloses.

Our search for islands is a performance of becoming. As we project ourselves into the

ocean, the ocean and its islands reflect back into us. We become less sedimentary,

more free-flowing. Welcome the little death necessary for this process the death of

fear, the death of inhibition, and the death of those calcifying regimes which

discourage our own processes of liberation.

Steeves 14 (Toby Steeves, Uttering towards otherwise: Students as rhizomatic nomad assemblages

[JNabs and Leonard])

Whereas popular visions of education reform terrorize students with neoliberal normatives and

institutional dividing practices that seek to objectify, shape, and control subjects , a competing

vision for educational programs would be to construe students as rhizomatic nomad assemblages

converging the ideas of Foucault and Deleuze to provide a more constructive vision of students as subjects. While it

must be acknowledged that figurations occlude and distort, they are also useful critical device[s] by which theoretical

forms of understanding are generated and transformed. [While many educationists are loathe to connect concepts like

terror or war with compulsory schooling, the comparisons may not be altogether inappropriate. Speaking to the suffusion of terror in

postmodern society, Lyotard writes: By terror I mean the efficiency gained by eliminating, or threatening to eliminate, a player from the

language game one shares with him [sic]. He is silenced or consents, not because he has been refuted, but because his ability to participate has

been threatened. The decision makers arrogance consists in the exercise of terror. It says: Adapt your aspirations to our ends or else. In

schools students quickly learn to adapt their aspirations and to fear the or else. Speaking directly to this

concern, John Gatto, for instance, writes of schools as sites where weapons of mass instruction are deployed on

students so that they become convinced of their powerlessness to effect change.] Nomadic students

are not sedentary. Rather, they like all things are in constant motion, perpetual unfolding. This

indeterminate dynamism fuels creativity, innovation, and the horizons of possibility: Deleuze often talks of

nomads and minorities. He contrasts nomads with sedentaries Deleuze throws in his lot with the nomads, with those whose restlessness

sends them on strange adventures, even when those adventures happen in a single place, as they do for writers and philosophers. Nomads do

not know. They seek. They seek not to find something, because there is not a something to be found. There is no transcendence to comfort

them. They seek not to discover but to connect. Which is to say they seek to create They are not afraid to throw the dice, and are not fearful

of the dice that fall back. Educational paradigms which conceptualize students as nomadic subjects would, by

necessity, privilege stochastic becomings rather than homogenizing classificatory schemata like

standardized tests and planes of normativity . To put it another way, students as nomadic subjects resist

representation by being in motion. While students may appear to be at rest or to have hit a plateau, this is a creative fiction. In all

aspects of their being, students are moving, transgressing, and diffracting. From their biological constituents to their

conceptual topographies, their networks of affect to their internalizations of desire, and from their

docility under technologies of power to their agency through technologies of the self, students are in

perpetual states of unfolding. This accepted, trying to anchor nomadic students to static, quantifiable

representations becomes dishonest and destructive. It is critical that educationists acknowledge

requiring students to perform limited versions of themselves in order to be academically

successful often results in schooling experiences that are, at best, cynical . Instead, if students were

construed as nomadic subjects school ecologies could be engineered so that educational obtainments

were measured according to motion rather than identity. In so doing, schools would become more

democratic, innovative, and pragmatic while simultaneously becoming less hegemonic, exclusionary,

and deforming . To interpret students as rhizomatic means to acknowledge them as emergent

irreducible multiplicities. Broadly speaking, this means that students development is not linear and cannot be predicted: Rhizomes

are contrasted to trees or arborescent systems; whereas trees are vertically ordered, rhizomes tend to be nonhieratic, laterally connected

multiplicities that do not feature linear development. Like tubers and mosses, they grow laterally and entangled, and like knowledge, they are

messy; any point in a rhizome can be connected to any other point, making such a structure open and dependent on emergent relations.

Rhizomes can be interrupted at any point only to start up again, proliferating lines of flight that sprout in contingently, not according to fixed

pathways. They thrive in irregular and in-between spaces, and have no specific starting or ending point; they are always in the middle, in

transition, on the verge of becoming something else. If an educational program were to adopt a vision of students as rhizomes, the

accountability-driven deficit model of education could be replaced with a more hospitable and compelling vision of education reform. Since

students would no longer be understood as autonomous or homogeneous, the horizons of inclusion

and the potential for innovation would be much greater. First, since rhizomes are not amendable to

any structural or generative model, construing students as rhizomatic would help mitigate or prevent

them from being boxed into identities. [Students who were previously identified as at risk or in need of remediation, for

example, could instead be seen as capable subjects with educational needs no more or less unique from anyone else. Rhizomatic students

cannot be classified according to what they are because they are continually becoming.] Second, seeing students as rhizomatic

subjects gives space for educational outcomes to emerge envisioning classrooms with vastly

different relational dynamics than possible when educational outcomes are imposed by external

agents via technologies of power. Third, rhizomes have no specific starting or ending point ; they are

always in the middle, so students who are seen as rhizomatic must be engaged in situ which might

be an altogether different topography or axiology than pre-fabricated educational outcomes are

capable of broaching. In summary, imagining students as rhizomatic subjects simultaneously rejects

objectification while enabling the release of singularities trapped within. While a vision of students as

autonomous subjects presumes them capable of making decisions outside all contexts, a rendering of

students as assemblages acknowledges them as inextricably entangled within chains of affect. According

to De Landas reading of Deleuze, assemblages are wholes whose properties emerge from the interaction between the parts. Thus, a bodys

function or potential or meaning becomes entirely dependent on which other bodies or machines it forms an assemblage with. Deleuze

describes assemblages as multiplicities, and points out that a multiplicity has neither subject nor object, only

determinations, magnitudes, and dimensions that cannot increase in number without the multiplicity

changing in nature. Seeing students as assemblages, then, requires educationists to address long-standing aporias over students

motivation to study. By that I mean that if students are multiplicities bound by affect, then their desire to study becomes a necessity rather

than a luxury for effective and ethical educational relationships. Furthermore, for classroom teachers to see students as assemblages means

recognizing educational encounters as nested within relational networks, opening the floor for students to meaningfully influence the course of

their studies, and construing success as a cooperative endeavour. Contrasted with prevailing visions of students as autonomous subjects

engaged in consuming knowledge, skills, or affect, seeing students as assemblages leaves space for and calls upon teachers to engage in the

production of affect. In other words, seeing students as assemblages re-maps the terrain of possibility and

reconceptualizes the processes and effects of teaching. Linking Deleuzes nomad, rhizome, and

assemblage together offers a bold new vision for 21st- century education one which resists

representation, rejects homogenized identities, and seeks to produce difference, and thereby

articulate new worlds. For teachers this insinuates the need for not merely a separate set of skills, but new lenses through which to

rethink curriculum as a whole. In order to operationalize this alternative vision of students a new conceptual repertoire is needed. The

rhizomatic nomad assemblage consolidates, translates and extends aspects of Foucaults and Deleuzes theorizations of the subject to convey a

framework for understanding students as dynamic processes. While rhizomatic nomad assemblages are understood as lacking in essentialist

identities, there is undeniably an I which endures and can resist technologies of power with technologies of the self. [To clarify, the I which

endures is not reducible or describable. Rather, it is the unspeakable seat of being which renders the self a self. While a theorization of the I lies

beyond the scope of this study it may be instructional to consider all sorrows are but as shadows; they pass and are done; but there is that

which remains.+ This I is symbolized by an unblinking eye which animates and distinguishes each rhizomatic nomad assemblage. Enclosing

each I are the uneven horizons of fractured identities, symbolized by variously colored partitions. These fractured identities are bisected by

waves of force which represent discourses historically, culturally, politically, and socially generated patterns of thinking, speaking, acting, and

interacting that are sanctioned by a particular group of people. *Deleuze writes of various forces and lines (e.g., flight, molarity,

segmentarity); however, I have drawn on quantum mechanics understanding of the collapse of the wave function and elected to reterritorialize

Deleuzes lines as waves. This reconceptualization retains the denotation of lines as pure difference that lies beneath and within . . .

constituted identities and adds new dimensions of explanatory power: (i) waves directly insinuate diffraction; (ii) waves have different

vibrations and intensities; (iii) waves bisect horizons unevenly.] Some of these waves of force are rejected by the horizons of our identities,

while others penetrate to the I. Each rhizomatic nomad assemblage is capable of (dis)affiliation, and this is represented by smooth or jagged

borders. In instances where waves of force are affiliative, some semblance of reciprocity and (pseudo)intersubjectivity may be said to occur.

However, disaffiliative waves of force may also penetrate the horizons of identities, and when this occurs a relationship can be said to be

asymmetrical or hegemonic. Institutions, symbolized by large block letters, project powerful waves of force and are typically disinterested in

reciprocity. Institutions play dominant roles in the process of subjection, and as a result their waves of force are represented as

disproportionately potent. Finally, since rhizomatic nomad assemblages are constantly in flux elements of motion and temporality must be

addressed. With this in mind, I have given each rhizomatic nomad assemblage spin and vibration. The rhizomatic nomad

assemblage is not merely an abstract theoretical device. It offers an accessible rebuttal for

educational frameworks which attempt to objectivize the subject by rendering students insipid and

uniform while pretending to liberate [their] true, inner selves. Many current education reform

initiatives, for instance, idealize competition, economic nationalism, and career readiness. From

this set of priorities acts of discipline, power, and violence technologies of power are

rationalized by educationists and policymakers as the way the world works or harsh reality.

Educational programs guided by a vision of students as rhizomatic nomad assemblages, in contrast,

would normalize difference, encourage interdependence, and democratize access to agency. Some of the likely

benefits of this emphasis on difference and alterity include: increased innovation, decreased concerns over behavior management, and less

stress for everyone involved. [Heavily competitive or accountability-driven school environments are fraught with stressed-out students, teachers

and administrators. One unavoidable consequence of high-stress learning environments is that students and teachers often become locked into

a relationship that often struggles to be educational and enters the domain of power. Another troublesome effect is teacher burn-out, which

can lead to sub-par learning outcomes in students, fragmented communities of practice, and high rates of attrition.] It is also possible that

schools populated by rhizomatic nomad assemblages might tend to be more hospitable. For instance, rather than emphasizing

standardized learning outcomes schools could create a worldly space, a space of plurality and

difference, a space where freedom can appear and where singular, unique individuals can come into

the world. Finally, if it is accepted that young people are increasingly at risk of . . . not developing the moral

attitudes necessary to recognize the humanity of those who live in starkly different circumstances

than themselves and that it no longer holds that, whatever we do, history will carry on, a shift towards viewing students as rhizomatic

nomad assemblages may help lead us out of these end times. Educationists interested in engaging students as rhizomatic nomad

assemblages can begin from the text within which they find themselves. For instance, community-wide discussions might begin over what it

means to be a good student in a particular educational environment. Some teachers and administrators might stress courtesy, studiousness,

or maturity, while others are likely to emphasize cognitive competencies, participation, or honesty. From this cacophony of values the good

student can be problematized and grounded in Derridas ordeal of undecidability tentative, contextual, interventionist, unfinished. After

the subject has been undone, the question then becomes how to conceive of our ethos our modes of being in a manner no longer based

in identity. From this foundational aporia, Foucaults technologies of the self can be used to provide an effective means of operationalizing the

development of rhizomatic nomad assemblages.

Você também pode gostar

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (121)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (266)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (400)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5794)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (895)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- Laffitte 2nd Retrial Motion DeniedDocumento6 páginasLaffitte 2nd Retrial Motion DeniedJoseph Erickson100% (1)

- Chapter 4 - TaxesDocumento28 páginasChapter 4 - TaxesabandcAinda não há avaliações

- (Onassis Series in Hellenic Culture) Lefkowitz, Mary R-Euripides and The Gods-Oxford University Press (2016)Documento321 páginas(Onassis Series in Hellenic Culture) Lefkowitz, Mary R-Euripides and The Gods-Oxford University Press (2016)HugoBotello100% (2)

- SyllabusDocumento2 páginasSyllabusDwaynetherocAinda não há avaliações

- Word PICs Bad UpdatedDocumento7 páginasWord PICs Bad UpdatedDwaynetherocAinda não há avaliações

- Aff Uco FinalsasdfDocumento15 páginasAff Uco FinalsasdfDwaynetherocAinda não há avaliações

- A Thank You From 2 Mello + TracklistDocumento1 páginaA Thank You From 2 Mello + TracklistRutenbündelbälle McschmalzAinda não há avaliações

- Dummy PDFDocumento1 páginaDummy PDFDwaynetherocAinda não há avaliações

- At Boehner DA AkashDocumento2 páginasAt Boehner DA AkashDwaynetherocAinda não há avaliações

- Carthage B - 1ACDocumento10 páginasCarthage B - 1ACDwaynetherocAinda não há avaliações

- Climate DealDocumento1 páginaClimate DealDwaynetherocAinda não há avaliações

- West Des Moines Valley Dahm Basler Neg Wake Forest Round1Documento9 páginasWest Des Moines Valley Dahm Basler Neg Wake Forest Round1DwaynetherocAinda não há avaliações

- A Door Into Ocean Negative - Wave 1 - HSS14Documento55 páginasA Door Into Ocean Negative - Wave 1 - HSS14DwaynetherocAinda não há avaliações

- Wake Forest Athanasopoulos Dean Aff Harvard Round2Documento7 páginasWake Forest Athanasopoulos Dean Aff Harvard Round2DwaynetherocAinda não há avaliações

- Guest Workers Critical 1ncDocumento18 páginasGuest Workers Critical 1ncDwaynetherocAinda não há avaliações

- 2ac vs. SchopenhauerDocumento14 páginas2ac vs. SchopenhauerDwaynetheroc100% (1)

- Reps FirstDocumento2 páginasReps FirstDwaynetherocAinda não há avaliações

- Attorney Client LD TopicDocumento122 páginasAttorney Client LD TopicDwaynetherocAinda não há avaliações

- Fear Discourse N StkjdsafjuffDocumento3 páginasFear Discourse N StkjdsafjuffDwaynetherocAinda não há avaliações

- DNG Aff 2acDocumento15 páginasDNG Aff 2acDwaynetherocAinda não há avaliações

- Criteria O VS S F NI Remarks: St. Martha Elementary School Checklist For Classroom EvaluationDocumento3 páginasCriteria O VS S F NI Remarks: St. Martha Elementary School Checklist For Classroom EvaluationSamantha ValenzuelaAinda não há avaliações

- SSL-VPN Service: End User GuideDocumento19 páginasSSL-VPN Service: End User Guideumer.shariff87Ainda não há avaliações

- 4.2.2 Monopolistic CompetitionDocumento6 páginas4.2.2 Monopolistic CompetitionArpita PriyadarshiniAinda não há avaliações

- Cadet Basic Training Guide (1998)Documento25 páginasCadet Basic Training Guide (1998)CAP History LibraryAinda não há avaliações

- AMGPricelistEN 09122022Documento1 páginaAMGPricelistEN 09122022nikdianaAinda não há avaliações

- Cases:-: Mohori Bibee V/s Dharmodas GhoseDocumento20 páginasCases:-: Mohori Bibee V/s Dharmodas GhoseNikhil KhandveAinda não há avaliações

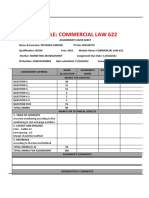

- Claw 622 2022Documento24 páginasClaw 622 2022Priyanka GirdariAinda não há avaliações

- Malimono Campus Learning Continuity PlanDocumento7 páginasMalimono Campus Learning Continuity PlanEmmylou BorjaAinda não há avaliações

- Best Loved Aussie Poems Ballads SongsDocumento36 páginasBest Loved Aussie Poems Ballads SongsMartina BernieAinda não há avaliações

- Bangalore & Karnataka Zones Teachers' Summer Vacation & Workshop Schedule 2022Documento1 páginaBangalore & Karnataka Zones Teachers' Summer Vacation & Workshop Schedule 2022EshwarAinda não há avaliações

- Wonder 6 Unit 7 ConsolidationDocumento1 páginaWonder 6 Unit 7 ConsolidationFer PineiroAinda não há avaliações

- Maptek FlexNet Server Quick Start Guide 4.0Documento28 páginasMaptek FlexNet Server Quick Start Guide 4.0arthur jhonatan barzola mayorgaAinda não há avaliações

- 4 Socioeconomic Impact AnalysisDocumento13 páginas4 Socioeconomic Impact AnalysisAnabel Marinda TulihAinda não há avaliações

- Endodontic Treatment During COVID-19 Pandemic - Economic Perception of Dental ProfessionalsDocumento8 páginasEndodontic Treatment During COVID-19 Pandemic - Economic Perception of Dental Professionalsbobs_fisioAinda não há avaliações

- 10 Biggest LiesDocumento12 páginas10 Biggest LiesJose RenteriaAinda não há avaliações

- CresumeDocumento2 páginasCresumeapi-315133081Ainda não há avaliações

- Educ 60 ReviewerDocumento6 páginasEduc 60 ReviewerJean GuyuranAinda não há avaliações

- Endole - Globe Services LTD - Comprehensive ReportDocumento20 páginasEndole - Globe Services LTD - Comprehensive ReportMoamed EliasAinda não há avaliações

- Art Martinez de Vara - Liberty Cities On DisplaysDocumento16 páginasArt Martinez de Vara - Liberty Cities On DisplaysTPPFAinda não há avaliações

- Identity Mapping ExerciseDocumento2 páginasIdentity Mapping ExerciseAnastasia WeningtiasAinda não há avaliações

- The Dawn of IslamDocumento2 páginasThe Dawn of IslamtalhaAinda não há avaliações

- Em Registered FormatDocumento288 páginasEm Registered FormatmanjushreyaAinda não há avaliações

- GeM Bidding 2062861Documento6 páginasGeM Bidding 2062861ManishAinda não há avaliações

- Manpower Planning, Recruitment and Selection AssignmentDocumento11 páginasManpower Planning, Recruitment and Selection AssignmentWEDAY LIMITEDAinda não há avaliações

- Food Court ProposalDocumento3 páginasFood Court ProposalJoey CerenoAinda não há avaliações

- 3.5G Packages - Robi TelecomDocumento2 páginas3.5G Packages - Robi TelecomNazia AhmedAinda não há avaliações

- De Thi Anh Ngu STB Philosophy 2022Documento4 páginasDe Thi Anh Ngu STB Philosophy 2022jhsbuitienAinda não há avaliações