Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Loadstar Shipping Vs CA - G.R. No. 131621. September 28, 1999

Enviado por

Ebbe Dy0 notas0% acharam este documento útil (0 voto)

34 visualizações9 páginasTransportation Law

Full Text with Syllabus

Título original

Loadstar Shipping vs CA - G.R. No. 131621. September 28, 1999

Direitos autorais

© © All Rights Reserved

Formatos disponíveis

DOCX, PDF, TXT ou leia online no Scribd

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoTransportation Law

Full Text with Syllabus

Direitos autorais:

© All Rights Reserved

Formatos disponíveis

Baixe no formato DOCX, PDF, TXT ou leia online no Scribd

0 notas0% acharam este documento útil (0 voto)

34 visualizações9 páginasLoadstar Shipping Vs CA - G.R. No. 131621. September 28, 1999

Enviado por

Ebbe DyTransportation Law

Full Text with Syllabus

Direitos autorais:

© All Rights Reserved

Formatos disponíveis

Baixe no formato DOCX, PDF, TXT ou leia online no Scribd

Você está na página 1de 9

FIRST DIVISION

[G.R. No. 131621. September 28, 1999.]

LOADSTAR SHIPPING CO., INC., petitioner, vs. COURT OF APPEALS and THE MANILA INSURANCE CO., INC.,

respondents.

King Capuchino Tan & Associates for petitioner.

Zapa Law Office for private respondent.

SYNOPSIS

When LOADSTAR's M/V "Cherokee" sank off Limasawa Island, Manila Insurance, Co., Inc., as insurer of its wood

shipment, paid the total loss thereof, then filed a complaint against LOADSTAR. The trial court ruled in favor of

MIC, and the Court of Appeals affirmed the same. Hence, this appeal with the issue: whether M/V "Cherokee" is a

public carrier and, whether LOADSTAR observed due diligence in the premises. HcaDTE

LOADSTAR is a common carrier under Art. 1732 of the Civil Code. It is not necessary that the carrier be issued a

certificate of public convenience and that the carriage of the goods was periodic or unscheduled. Further, on that

fateful day, the vessel was not chartered for a special cargo or to a special person only. It was carrying a particular

type of cargo for one shipper, but that is no reason to convert the vessel from a common to a private carrier,

especially as it was also carrying passengers. On the second issue, the Court found M/V "Cherokee" not seaworthy

as it was not even sufficiently manned at the time. The Court affirmed the decision of the Court of Appeals.

SYLLABUS

1. CIVIL LAW; SPECIAL CONTRACTS; COMMON CARRIERS; ELUCIDATED. LOADSTAR is a common carrier. It

is not necessary that the carrier be issued a certificate of public convenience, and this public character is not

altered by the fact that the carriage of the goods in question was periodic, occasional, episodic or unscheduled. In

the case of De Guzman v. Court of Appeals, the Court juxtaposed the statutory definition of "common carriers"

with the peculiar circumstances of that case, viz: The Civil Code defines "common carriers" in the following terms:

"Article 1732. Common carriers are persons, corporations, firms or associations engaged in the business of carrying

or transporting passengers or goods or both, by land, water, or air for compensation, offering their services to the

public." The above article makes no distinction between one whose principal business activity is the carrying of

persons or goods or both, and one who does such carrying only as an ancillary activity (in local idiom, as "a

sideline." Article 1732 also carefully avoids making any distinction between a person or enterprise offering

transportation service on a regular or scheduled basis and one offering such service on an occasional, episodic or

unscheduled basis. Neither does Article 1732 distinguish between a carrier offering its services to the "general

public," i.e., the general community or population, and one who offers services or solicits business only from a

narrow segment of the general population. We think that Article 1733 deliberately refrained from making such

distinctions. SacTCA

2. ID.; ID.; ID.; CASE OF HOME INSURANCE CO. V. AMERICAN STEAMSHIP AGENCIES, INC. [23 SCRA 24

(1968)]; NOT APPLICABLE IN ABSENCE OF EVIDENCE THAT VESSEL WAS SPECIALLY CHARTERED. LOADSTAR relied

on the 1968 case of Home Insurance Co. v. American Steamship Agencies, Inc., where this Court held that a

common carrier transporting special cargo or chartering the vessel to a special person becomes a private carrier

that is not subject to the provisions of the Civil Code. However, the records do not disclose that the M/V

"Cherokee," on the date in question, undertook to carry a special cargo or was chartered to a special person only.

There was no charter party. The bills of lading failed to show any special arrangement, but only a general provision

to the effect that the M/V "Cherokee" was a "general cargo carrier." Further, the bare fact that the vessel was

carrying a particular type of cargo for one shipper, which appears to be purely coincidental, is not reason enough

to convert the vessel from a common to a private carrier, especially where, as in this case, it was shown that the

vessel was also carrying passengers.

3. ID.; ID.; ID.; FAILURE TO KEEP VESSEL SEAWORTHY. M/V "Cherokee" was not seaworthy when it

embarked on its voyage on 19 November 1984. The vessel was not even sufficiently manned at the time. "For a

vessel to be seaworthy, it must be adequately equipped for the voyage and manned with a sufficient number of

competent officers and crew. The failure of a common carrier to maintain in seaworthy condition its vessel

involved in a contract of carriage is a clear breach of its duty prescribed in Article 1755 of the Civil Code."

4. ID.; ID.; ID.; DOCTRINE OF LIMITED LIABILITY; NOT APPLICABLE WHERE THERE WAS NEGLIGENCE ON PART

OF THE VESSEL OWNER. The doctrine of limited liability does not apply where there was negligence on the part

of the vessel owner or agent. LOADSTAR was at fault or negligent in not maintaining a seaworthy vessel and in

having allowed its vessel to sail despite knowledge of an approaching typhoon. In any event, it did not sink because

of any storm that may be deemed as force majeure, inasmuch as the wind condition in the area where it sank was

determined to be moderate. Since it was remiss in the performance of its duties, LOADSTAR cannot hide behind

the "limited liability" doctrine to escape responsibility for the loss of the vessel and its cargo. DcCITS

5. ID.; ID.; ID.; STIPULATION OF SHIPMENTS MADE AT OWNER'S RISK; VOID. The stipulation in the case at

bar effectively reduces the common carrier's liability for the loss or destruction of the goods to a degree less than

extraordinary (Articles 1744 and 1745), that is, the carrier is not liable for any loss or damage to shipments made

at "owner's risk." Such stipulation is obviously null and void for being contrary to public policy. It has been said:

Three kinds of stipulations have often been made in a bill of lading. The first is one exempting the carrier from any

and all liability for loss or damage occasioned by its own negligence. The second is one providing for an unqualified

limitation of such liability to an agreed valuation. And the third is one limiting the liability of the carrier to an

agreed valuation unless the shipper declares a higher value and pays a higher rate of freight. According to an

almost uniform weight of authority, the first and second kinds of stipulations are invalid as being contrary to public

policy, but the third is valid and enforceable. Since the stipulation in question is null and void, it follows that when

MIC paid the shipper, it was subrogated to all the rights which the latter has against the common carrier,

LOADSTAR.

6. ID.; ID.; ID.; PRESCRIPTION OF CLAIMS FOR LOSS. MIC's cause of action had not yet prescribed at the

time it was concerned. Inasmuch as neither the Civil Code nor the Code of Commerce states a specific prescriptive

period on the matter, the Carriage of Goods by Sea Act (COGSA) which provides for a one-year period of

limitation on claims for loss of, or damage to, cargoes sustained during transit may be applied suppletorily to

the case at bar. This one-year prescriptive period also applies to the insurer of the goods. In this case, the period

for filing the action for recovery has not yet elapsed. Moreover, a stipulation reducing the one-year period is null

and void; it must, accordingly, be struck down. STcADa

D E C I S I O N

DAVIDE, JR., C.J p:

Petitioner Loadstar Shipping Co., Inc. (hereafter LOADSTAR), in this petition for review on certiorari under Rule 45

of the 1997 Rules of Civil Procedure, seeks to reverse and set aside the following: (a) the 30 January 1997 decision

1 of the Court of Appeals in CA-G.R. CV No. 36401, which affirmed the decision of 4 October 1991 2 of the Regional

Trial Court of Manila, Branch 16, in Civil Case No. 85-29110, ordering LOADSTAR to pay private respondent Manila

Insurance Co. (hereafter MIC) the amount of P6,067,178, with legal interest from the filing of the complaint until

fully paid, P8,000 as attorney's fees, and the costs of the suit; and (b) its resolution of 19 November 1997, 3

denying LOADSTAR's motion for reconsideration of said decision.

The facts are undisputed. LLjur

On 19 November 1984, LOADSTAR received on board its M/V "Cherokee" (hereafter, the vessel) the following

goods for shipment:

a) 705 bales of lawanit hardwood;

b) 27 boxes and crates of tilewood assemblies and others; and

c) 49 bundles of mouldings R & W (3) Apitong Bolidenized.

The goods, amounting to P6,067,178, were insured for the same amount with MIC against various risks including

"TOTAL LOSS BY TOTAL LOSS OF THE VESSEL." The vessel, in turn, was insured by Prudential Guarantee &

Assurance, Inc. (hereafter PGAI) for P4 million. On 20 November 1984, on its way to Manila from the port of

Nasipit, Agusan del Norte, the vessel, along with its cargo, sank off Limasawa Island. As a result of the total loss of

its shipment, the consignee made a claim with LOADSTAR which, however, ignored the same. As the insurer, MIC

paid P6,075,000 to the insured in full settlement of its claim, and the latter executed a subrogation receipt

therefor.

On 4 February 1985, MIC filed a complaint against LOADSTAR and PGAI, alleging that the sinking of the vessel was

due to the fault and negligence of LOADSTAR and its employees. It also prayed that PGAI be ordered to pay the

insurance proceeds from the loss of the vessel directly to MIC, said amount to be deducted from MIC's claim from

LOADSTAR.

In its answer, LOADSTAR denied any liability for the loss of the shipper's goods and claimed that the sinking of its

vessel was due to force majeure. PGAI, on the other hand, averred that MIC had no cause of action against it,

LOADSTAR being the party insured. In any event, PGAI was later dropped as a party defendant after it paid the

insurance proceeds to LOADSTAR.

As stated at the outset, the court a quo rendered judgment in favor of MIC, prompting LOADSTAR to elevate the

matter to the Court of Appeals, which, however, agreed with the trial court and affirmed its decision in toto.

In dismissing LOADSTAR's appeal, the appellate court made the following observations:

1) LOADSTAR cannot be considered a private carrier on the sole ground that there was a single shipper on

that fateful voyage. The court noted that the charter of the vessel was limited to the ship, but LOADSTAR retained

control over its crew. 4

2) As a common carrier, it is the Code of Commerce, not the Civil Code, which should be applied in

determining the rights and liabilities of the parties.

3) The vessel was not seaworthy because it was undermanned on the day of the voyage. If it had been

seaworthy, it could have withstood the "natural and inevitable action of the sea" on 20 November 1984, when the

condition of the sea was moderate. The vessel sank, not because of force majeure, but because it was not

seaworthy. LOADSTAR'S allegation that the sinking was probably due to the "convergence of the winds," as stated

by a PAGASA expert, was not duly proven at the trial. The "limited liability" rule, therefore, is not applicable

considering that, in this case, there was an actual finding of negligence on the part of the carrier. 5

4) Between MIC and LOADSTAR, the provisions of the Bill of Lading do not apply because said provisions bind

only the shipper/consignee and the carrier. When MIC paid the shipper for the goods insured, it was subrogated to

the latter's rights as against the carrier, LOADSTAR. 6

5) There was a clear breach of the contract of carriage when the shipper's goods never reached their

destination. LOADSTAR's defense of "diligence of a good father of a family" in the training and selection of its crew

is unavailing because this is not a proper or complete defense in culpa contractual. cdll

6) "Art. 361 (of the Code of Commerce) has been judicially construed to mean that when goods are delivered

on board a ship in good order and condition, and the shipowner delivers them to the shipper in bad order and

condition, it then devolves upon the shipowner to both allege and prove that the goods were damaged by reason

of some fact which legally exempts him from liability." Transportation of the merchandise at the risk and venture

of the shipper means that the latter bears the risk of loss or deterioration of his goods arising from fortuitous

events, force majeure, or the inherent nature and defects of the goods, but not those caused by the presumed

negligence or fault of the carrier, unless otherwise proved. 7

The errors assigned by LOADSTAR boil down to a determination of the following issues:

(1) Is the M/V "Cherokee" a private or a common carrier?

(2) Did LOADSTAR observe due and/or ordinary diligence in these premises?

Regarding the first issue, LOADSTAR submits that the vessel was a private carrier because it was not issued a

certificate of public convenience, it did not have a regular trip or schedule nor a fixed route, and there was only

"one shipper, one consignee for a special cargo."

In refutation, MIC argues that the issue as to the classification of the M/V "Cherokee" was not timely raised below;

hence, it is barred by estoppel. While it is true that the vessel had on board only the cargo of wood products for

delivery to one consignee, it was also carrying passengers as part of its regular business. Moreover, the bills of

lading in this case made no mention of any charter party but only a statement that the vessel was a "general cargo

carrier." Neither was there any "special arrangement" between LOADSTAR and the shipper regarding the shipment

of the cargo. The singular fact that the vessel was carrying a particular type of cargo for one shipper is not

sufficient to convert the vessel into a private carrier.

As regards the second error, LOADSTAR argues that as a private carrier, it cannot be presumed to have been

negligent, and the burden of proving otherwise devolved upon MIC. 8

LOADSTAR also maintains that the vessel was seaworthy. Before the fateful voyage on 19 November 1984, the

vessel was allegedly dry docked at Keppel Philippines Shipyard and was duly inspected by the maritime safety

engineers of the Philippine Coast Guard, who certified that the ship was fit to undertake a voyage. Its crew at the

time was experienced, licensed and unquestionably competent. With all these precautions, there could be no

other conclusion except that LOADSTAR exercised the diligence of a good father of a family in ensuring the vessel's

seaworthiness.

LOADSTAR further claims that it was not responsible for the loss of the cargo, such loss being due to force majeure.

It points out that when the vessel left Nasipit, Agusan del Norte, on 19 November 1984, the weather was fine until

the next day when the vessel sank due to strong waves. MIC's witness, Gracelia Tapel, fully established the

existence of two typhoons, "WELFRING" and "YOLING," inside the Philippine area of responsibility. In fact, on 20

November 1984, signal no. 1 was declared over Eastern Visayas, which includes Limasawa Island. Tapel also

testified that the convergence of winds brought about by these two typhoons strengthened wind velocity in the

area, naturally producing strong waves and winds, in turn, causing the vessel to list and eventually sink. LibLex

LOADSTAR goes on to argue that, being a private carrier, any agreement limiting its liability, such as what

transpired in this case, is valid. Since the cargo was being shipped at "owner's risk," LOADSTAR was not liable for

any loss or damage to the same. Therefore, the Court of Appeals erred in holding that the provisions of the bills of

lading apply only to the shipper and the carrier, and not to the insurer of the goods, which conclusion runs counter

to the Supreme Court's ruling in the case of St. Paul Fire & Marine Insurance Co. v. Macondray & Co., Inc., 9 and

National Union Fire Insurance Company of Pittsburgh v. Stolt-Nielsen Phils., Inc. 10

Finally, LOADSTAR avers that MIC's claim had already prescribed, the case having been instituted beyond the

period stated in the bills of lading for instituting the same suits based upon claims arising from shortage,

damage, or non-delivery of shipment shall be instituted within sixty days from the accrual of the right of action.

The vessel sank on 20 November 1984; yet, the case for recovery was filed only on 4 February 1985.

MIC, on the other hand, claims that LOADSTAR was liable, notwithstanding that the loss of the cargo was due to

force majeure, because the same concurred with LOADSTAR's fault or negligence.

Secondly, LOADSTAR did not raise the issue of prescription in the court below; hence, the same must be deemed

waived.

Thirdly, the "limited liability" theory is not applicable in the case at bar because LOADSTAR was at fault or

negligent, and because it failed to maintain a seaworthy vessel. Authorizing the voyage notwithstanding its

knowledge of a typhoon is tantamount to negligence.

We find no merit in this petition.

Anent the first assigned error, we hold that LOADSTAR is a common carrier. It is not necessary that the carrier be

issued a certificate of public convenience, and this public character is not altered by the fact that the carriage of

the goods in question was periodic, occasional, episodic or unscheduled.

In support of its position, LOADSTAR relied on the 1968 case of Home Insurance Co. v. American Steamship

Agencies, Inc., 11 where this Court held that a common carrier transporting special cargo or chartering the vessel

to a special person becomes a private carrier that is not subject to the provisions of the Civil Code. Any stipulation

in the charter party absolving the owner from liability for loss due to the negligence of its agent is void only if the

strict policy governing common carriers is upheld. Such policy has no force where the public at large is not

involved, as in the case of a ship totally chartered for the use of a single party. LOADSTAR also cited Valenzuela

Hardwood and Industrial Supply, Inc. v. Court of Appeals 12 and National Steel Corp. v. Court of Appeals, 13 both

of which upheld the Home Insurance doctrine. LLjur

These cases invoked by LOADSTAR are not applicable in the case at bar for the simple reason that the factual

settings are different. The records do not disclose that the M/V "Cherokee," on the date in question, undertook to

carry a special cargo or was chartered to a special person only. There was no charter party. The bills of lading failed

to show any special arrangement, but only a general provision to the effect that the M/V "Cherokee" was a

"general cargo carrier." 14 Further, the bare fact that the vessel was carrying a particular type of cargo for one

shipper, which appears to be purely coincidental, is not reason enough to convert the vessel from a common to a

private carrier, especially where, as in this case, it was shown that the vessel was also carrying passengers.

Under the facts and circumstances obtaining in this case, LOADSTAR fits the definition of a common carrier under

Article 1732 of the Civil Code. In the case of De Guzman v. Court of Appeals, 15 the Court juxtaposed the statutory

definition of "common carriers" with the peculiar circumstances of that case, viz.:

The Civil Code defines "common carriers" in the following terms:

"ARTICLE 1732. Common carriers are persons, corporations, firms or associations engaged in the business of

carrying or transporting passengers or goods or both, by land, water, or air for compensation, offering their

services to the public."

The above article makes no distinction between one whose principal business activity is the carrying of persons or

goods or both, and one who does such carrying only as an ancillary activity (in local idiom, as "a sideline". Article

1732 also carefully avoids making any distinction between a person or enterprise offering transportation service

on a regular or scheduled basis and one offering such service on an occasional, episodic or unscheduled basis.

Neither does Article 1732 distinguish between a carrier offering its services to the "general public," i.e., the general

community or population, and one who offers services or solicits business only from a narrow segment of the

general population. We think that Article 1733 deliberately refrained from making such distinctions.

xxx xxx xxx

It appears to the Court that private respondent is properly characterized as a common carrier even though he

merely "back-hauled" goods for other merchants from Manila to Pangasinan, although such backhauling was done

on a periodic or occasional rather than regular or scheduled manner, and even though private respondent's

principal occupation was not the carriage of goods for others. There is no dispute that private respondent charged

his customers a fee for hauling their goods; that that fee frequently fell below commercial freight rates is not

relevant here.

The Court of Appeals referred to the fact that private respondent held no certificate of public convenience, and

concluded he was not a common carrier. This is palpable error. A certificate of public convenience is not a requisite

for the incurring of liability under the Civil Code provisions governing common carriers. That liability arises the

moment a person or firm acts as a common carrier, without regard to whether or not such carrier has also

complied with the requirements of the applicable regulatory statute and implementing regulations and has been

granted a certificate of public convenience or other franchise. To exempt private respondent from the liabilities of

a common carrier because he has not secured the necessary certificate of public convenience, would be offensive

to sound public policy; that would be to reward private respondent precisely for failing to comply with applicable

statutory requirements. The business of a common carrier impinges directly and intimately upon the safety and

well being and property of those members of the general community who happen to deal with such carrier. The

law imposes duties and liabilities upon common carriers for the safety and protection of those who utilize their

services and the law cannot allow a common carrier to render such duties and liabilities merely facultative by

simply failing to obtain the necessary permits and authorizations.

Moving on to the second assigned error, we find that the M/V "Cherokee" was not seaworthy when it embarked

on its voyage on 19 November 1984. The vessel was not even sufficiently manned at the time. "For a vessel to be

seaworthy, it must be adequately equipped for the voyage and manned with a sufficient number of competent

officers and crew. The failure of a common carrier to maintain in seaworthy condition its vessel involved in a

contract of carriage is a clear breach of its duty prescribed in Article 1755 of the Civil Code." 16

Neither do we agree with LOADSTAR's argument that the "limited liability" theory should be applied in this case.

The doctrine of limited liability does not apply where there was negligence on the part of the vessel owner or

agent. 17 LOADSTAR was at fault or negligent in not maintaining a seaworthy vessel and in having allowed its

vessel to sail despite knowledge of an approaching typhoon. In any event, it did not sink because of any storm that

may be deemed as force majeure, inasmuch as the wind condition in the area where it sank was determined to be

moderate. Since it was remiss in the performance of its duties, LOADSTAR cannot hide behind the "limited liability"

doctrine to escape responsibility for the loss of the vessel and its cargo.

LOADSTAR also claims that the Court of Appeals erred in holding it liable for the loss of the goods, in utter

disregard of this Court's pronouncements in St. Paul Fire & Marine Ins. Co. v. Macondray & Co., Inc., 18 and

National Union Fire Insurance v. Stolt-Nielsen Phils., Inc. 19 It was ruled in these two cases that after paying the

claim of the insured for damages under the insurance policy, the insurer is subrogated merely to the rights of the

assured, that is, it can recover only the amount that may, in turn, be recovered by the latter. Since the right of the

assured in case of loss or damage to the goods is limited or restricted by the provisions in the bills of lading, a suit

by the insurer as subrogee is necessarily subject to the same limitations and restrictions. We do not agree. In the

first place, the cases relied on by LOADSTAR involved a limitation on the carrier's liability to an amount fixed in the

bill of lading which the parties may enter into, provided that the same was freely and fairly agreed upon (Articles

1749-1750). On the other hand, the stipulation in the case at bar effectively reduces the common carrier's liability

for the loss or destruction of the goods to a degree less than extraordinary (Articles 1744 and 1745), that is, the

carrier is not liable for any loss or damage to shipments made at "owner's risk." Such stipulation is obviously null

and void for being contrary to public policy. 20 It has been said:

Three kinds of stipulations have often been made in a bill of lading. The first is one exempting the carrier from any

and all liability for loss or damage occasioned by its own negligence. The second is one providing for an unqualified

limitation of such liability to an agreed valuation. And the third is one limiting the liability of the carrier to an

agreed valuation unless the shipper declares a higher value and pays a higher rate of freight. According to an

almost uniform weight of authority, the first and second kinds of stipulations are invalid as being contrary to public

policy, but the third is valid and enforceable. 21

Since the stipulation in question is null and void, it follows that when MIC paid the shipper, it was subrogated to all

the rights which the latter has against the common carrier, LOADSTAR.

Neither is there merit to the contention that the claim in this case was barred by prescription. MIC's cause of

action had not yet prescribed at the time it was concerned. Inasmuch as neither the Civil Code nor the Code of

Commerce states a specific prescriptive period on the matter, the Carriage of Goods by Sea Act (COGSA) which

provides for a one-year period of limitation on claims for loss of, or damage to, cargoes sustained during transit

may be applied suppletorily to the case at bar. This one-year prescriptive period also applies to the insurer of the

goods. 22 In this case, the period for filing the action for recovery has not yet elapsed. Moreover, a stipulation

reducing the one-year period is null and void; 23 it must, accordingly, be struck down.

WHEREFORE, the instant petition is DENIED and the challenged decision of 30 January 1997 of the Court of Appeals

in CA-G.R. CV No. 36401 is AFFIRMED. Costs against petitioner.

SO ORDERED.

Puno, Kapunan, Pardo and Ynares-Santiago, JJ., concur.

Você também pode gostar

- 20 Loadstar Shipping Co., Inc. v. Court of Appeals, G.R. No. 131621, (September 28, 1999)Documento14 páginas20 Loadstar Shipping Co., Inc. v. Court of Appeals, G.R. No. 131621, (September 28, 1999)Cyrene Joy MoranoAinda não há avaliações

- LOADSTAR Shipping's Liability for Sunken CargoDocumento8 páginasLOADSTAR Shipping's Liability for Sunken CargoRoji Belizar HernandezAinda não há avaliações

- Carrier Liability for Sunken CargoDocumento10 páginasCarrier Liability for Sunken CargoMary Louise R. ConcepcionAinda não há avaliações

- SUNK CARGODocumento11 páginasSUNK CARGOEm-em DomingoAinda não há avaliações

- Loadstar Shipping Co., Inc. vs. Court of Appeals (1999)Documento14 páginasLoadstar Shipping Co., Inc. vs. Court of Appeals (1999)Angelette BulacanAinda não há avaliações

- Traffic Code Case ReviewDocumento3 páginasTraffic Code Case ReviewIyah RoblesAinda não há avaliações

- Loadstar Shipping v. CA (G.R. No.131621)Documento3 páginasLoadstar Shipping v. CA (G.R. No.131621)Rache GutierrezAinda não há avaliações

- Loadstar Shipping Co V CADocumento2 páginasLoadstar Shipping Co V CAAnonymous cRzv1YJWMAinda não há avaliações

- 11 Loadstar Shipping Co. vs. CA, 315 SCRA 339Documento13 páginas11 Loadstar Shipping Co. vs. CA, 315 SCRA 339blessaraynesAinda não há avaliações

- Transportation Law NotesDocumento25 páginasTransportation Law NotesNovern Irish PascoAinda não há avaliações

- Loadstar Shipping Co Vs CADocumento2 páginasLoadstar Shipping Co Vs CAKaren Gina DupraAinda não há avaliações

- Loadstar Shipping Vs CADocumento2 páginasLoadstar Shipping Vs CARocky C. BaliaoAinda não há avaliações

- Transportation Law Case DigestDocumento4 páginasTransportation Law Case DigestCelina TanAinda não há avaliações

- Transportation Law CasesDocumento7 páginasTransportation Law CasesChicklet ArponAinda não há avaliações

- Court Rules Loadstar Shipping Co. Liable for Sunken CargoDocumento2 páginasCourt Rules Loadstar Shipping Co. Liable for Sunken CargoNina100% (1)

- 8 Phil General InsuranceDocumento7 páginas8 Phil General InsuranceMary Louise R. ConcepcionAinda não há avaliações

- Supreme Court rules carrier a common carrier liable for cargo lossDocumento7 páginasSupreme Court rules carrier a common carrier liable for cargo lossEmary GutierrezAinda não há avaliações

- Coastwise Carrier Liability for Damaged CargoDocumento14 páginasCoastwise Carrier Liability for Damaged CargoEj CalaorAinda não há avaliações

- Transportation Law Case Digest VeeDocumento25 páginasTransportation Law Case Digest VeeJoshua Cabaccan0% (1)

- Transpo Cases Week 1Documento19 páginasTranspo Cases Week 1Raiza SarteAinda não há avaliações

- Loadstar Shipping Co Inc Vs CA - 131621 - September 28, 1999 - C. J. Davide Jr. - First DivisionDocumento6 páginasLoadstar Shipping Co Inc Vs CA - 131621 - September 28, 1999 - C. J. Davide Jr. - First DivisionGloria Diana DulnuanAinda não há avaliações

- Test of Common Carrier Vlasons ShippingDocumento4 páginasTest of Common Carrier Vlasons ShippingMarkyHeroiaAinda não há avaliações

- Asia Lighterage and Shipping Inc. v. CADocumento17 páginasAsia Lighterage and Shipping Inc. v. CAJoshua ParilAinda não há avaliações

- PHILAMGEN v. PKS ShippingDocumento2 páginasPHILAMGEN v. PKS ShippingWilliam AzucenaAinda não há avaliações

- Home Insurance Company vs. American Steamship and Luzon Stevedoring G.R. No. L-25599 April 4, 1968Documento7 páginasHome Insurance Company vs. American Steamship and Luzon Stevedoring G.R. No. L-25599 April 4, 1968MJ DecolongonAinda não há avaliações

- Petitioner-Appellant vs. vs. Respondents Appellees: Second DivisionDocumento9 páginasPetitioner-Appellant vs. vs. Respondents Appellees: Second DivisionNicole HinanayAinda não há avaliações

- Asia Lighterage & Shipping Vs CA - G.R. No. 147246. August 19, 2003Documento6 páginasAsia Lighterage & Shipping Vs CA - G.R. No. 147246. August 19, 2003Ebbe DyAinda não há avaliações

- G.R. No. 114167 July 12, 1995 Coastwise Lighterage Corporation, Petitioner, Vs - Court of Appeals and The Philippine General Insurance Company, RespondentsDocumento1 páginaG.R. No. 114167 July 12, 1995 Coastwise Lighterage Corporation, Petitioner, Vs - Court of Appeals and The Philippine General Insurance Company, RespondentsJIEZFA100% (1)

- Compilation of Digests TranspoDocumento107 páginasCompilation of Digests Transpomonmonmonmon21Ainda não há avaliações

- Common CarriersDocumento92 páginasCommon CarriersAdrian Mika AdriaticoAinda não há avaliações

- LOADSTAR SHIPPING CO., INC., Petitioner, vs. COURT OF APPEALS and THE MANILA INSURANCE CO., INC., Respondents.Documento4 páginasLOADSTAR SHIPPING CO., INC., Petitioner, vs. COURT OF APPEALS and THE MANILA INSURANCE CO., INC., Respondents.lexxAinda não há avaliações

- Loadstar Vs CA GR No. 131621Documento5 páginasLoadstar Vs CA GR No. 131621Anonymous KZEIDzYrOAinda não há avaliações

- Insurance Firm Appeals Cargo Loss RulingDocumento5 páginasInsurance Firm Appeals Cargo Loss RulingshaneAAshaneAinda não há avaliações

- CasesDocumento32 páginasCasesOpal P ManaogAinda não há avaliações

- 1.) G.R. No. 149038 April 9, 2003 Philippine American General Insurance Company, Petitioner, vs. PKS SHIPPING COMPANY, RespondentDocumento104 páginas1.) G.R. No. 149038 April 9, 2003 Philippine American General Insurance Company, Petitioner, vs. PKS SHIPPING COMPANY, RespondentLio de LeonAinda não há avaliações

- Coastwise Lighterage v. CADocumento10 páginasCoastwise Lighterage v. CAMonica Bolado-AsuncionAinda não há avaliações

- G.R. No. 149038 April 9, 2003 Philippine American General Insurance Company, Petitioner, PKS SHIPPING COMPANY, Respondent. Vitug, J.Documento4 páginasG.R. No. 149038 April 9, 2003 Philippine American General Insurance Company, Petitioner, PKS SHIPPING COMPANY, Respondent. Vitug, J.KMAinda não há avaliações

- Transportation Law Outline With Statutory Provisions and Case DoctrinesDocumento27 páginasTransportation Law Outline With Statutory Provisions and Case DoctrinesRandy Nier Garete SaladeroAinda não há avaliações

- Lastimoso v. DolienteDocumento3 páginasLastimoso v. DolienteMikkaEllaAncla100% (1)

- Transpo Digest PoolDocumento96 páginasTranspo Digest PoolNeil Owen Deona100% (3)

- TRANSPO Case Digests - 3BBDocumento56 páginasTRANSPO Case Digests - 3BBFrancois Amos PalomoAinda não há avaliações

- Held:: First Philippine Industrial Corp. v. Court of AppealsDocumento7 páginasHeld:: First Philippine Industrial Corp. v. Court of AppealsCiena MaeAinda não há avaliações

- Loadstar vs. CADocumento2 páginasLoadstar vs. CAJustin Luis JalandoniAinda não há avaliações

- Loadstar Shipping Co., Inc., Petitioner, vs. Court of Appeals and THE MANILA INSURANCE CO., INC., RespondentsDocumento5 páginasLoadstar Shipping Co., Inc., Petitioner, vs. Court of Appeals and THE MANILA INSURANCE CO., INC., RespondentsKiz AndersonAinda não há avaliações

- Common Carrier ResponsibilitiesDocumento38 páginasCommon Carrier ResponsibilitiesJuvylynPiojo100% (1)

- Case Digest (Transpo)Documento91 páginasCase Digest (Transpo)Leo Estaniel100% (1)

- Loadstar Shipping Vs CADocumento6 páginasLoadstar Shipping Vs CAmelAinda não há avaliações

- 4th Set Digests FINALDocumento15 páginas4th Set Digests FINALLouiegie Thomas San JuanAinda não há avaliações

- Transportation CasesDocumento36 páginasTransportation CasesAna AltisoAinda não há avaliações

- NDC v. CaDocumento10 páginasNDC v. CaJanicaAinda não há avaliações

- TRANSPORTATION - Case CompendiumDocumento36 páginasTRANSPORTATION - Case CompendiumkatAinda não há avaliações

- Singa Ship Management Phils Vs NLRCDocumento34 páginasSinga Ship Management Phils Vs NLRCRhows BuergoAinda não há avaliações

- Transpo CD 2Documento15 páginasTranspo CD 2Japheth CuaAinda não há avaliações

- 1 National Development Company v. CADocumento10 páginas1 National Development Company v. CAStephen CabalteraAinda não há avaliações

- Transpo Notes PrelimsDocumento36 páginasTranspo Notes PrelimsAzeAinda não há avaliações

- Court upholds charter party exemption of liabilityDocumento44 páginasCourt upholds charter party exemption of liabilityKatherine KatherineAinda não há avaliações

- Admiralty Law for the Maritime ProfessionalNo EverandAdmiralty Law for the Maritime ProfessionalNota: 1 de 5 estrelas1/5 (1)

- Shipping Practice - With a Consideration of the Law Relating TheretoNo EverandShipping Practice - With a Consideration of the Law Relating TheretoAinda não há avaliações

- The Letters of Gracchus on the East India QuestionNo EverandThe Letters of Gracchus on the East India QuestionAinda não há avaliações

- Digest Executive Secretary Vs CA and Asian Recruit CouncilDocumento2 páginasDigest Executive Secretary Vs CA and Asian Recruit CouncilEbbe Dy100% (2)

- Reyna Vs Commission On Audit - G.R. No. 167219. February 8, 2011Documento15 páginasReyna Vs Commission On Audit - G.R. No. 167219. February 8, 2011Ebbe DyAinda não há avaliações

- AnnexC4 Affidavit of Inability To PayDocumento2 páginasAnnexC4 Affidavit of Inability To PayJerome MansibangAinda não há avaliações

- Bankard Union Vs NLRC DigestDocumento2 páginasBankard Union Vs NLRC DigestEbbe Dy100% (3)

- Sahali Vs Comelec - G.R. No. 201796. January 15, 2013Documento8 páginasSahali Vs Comelec - G.R. No. 201796. January 15, 2013Ebbe Dy100% (1)

- Wack Wack Golf & Country Vs Workmens - G.R. No. L-9641. May 24, 1957Documento3 páginasWack Wack Golf & Country Vs Workmens - G.R. No. L-9641. May 24, 1957Ebbe DyAinda não há avaliações

- Digest Sangalang Vs IacDocumento3 páginasDigest Sangalang Vs IacEbbe Dy100% (4)

- Digest Province of Rizal Vs Exec SecDocumento3 páginasDigest Province of Rizal Vs Exec SecEbbe Dy100% (4)

- Digest Santulan Vs Exec SecretaryDocumento2 páginasDigest Santulan Vs Exec SecretaryEbbe DyAinda não há avaliações

- Dela Llana Vs Alba - G.R. No. 57883. March 12, 1982Documento62 páginasDela Llana Vs Alba - G.R. No. 57883. March 12, 1982Ebbe DyAinda não há avaliações

- Pasricha Vs Don Luis Dison Realty - G.R. No. 136409. March 14, 2008Documento8 páginasPasricha Vs Don Luis Dison Realty - G.R. No. 136409. March 14, 2008Ebbe DyAinda não há avaliações

- Edades Vs Edades - G.R. No. L-8964. July 31, 1956Documento2 páginasEdades Vs Edades - G.R. No. L-8964. July 31, 1956Ebbe DyAinda não há avaliações

- Digest - Serrano Vs NLRC G.R. No. 117040. January 27, 2000Documento3 páginasDigest - Serrano Vs NLRC G.R. No. 117040. January 27, 2000Ebbe Dy100% (1)

- Bank of Commerce Vs Planters Developmet - G.R. Nos. 154470-71. September 24, 2012Documento22 páginasBank of Commerce Vs Planters Developmet - G.R. Nos. 154470-71. September 24, 2012Ebbe DyAinda não há avaliações

- Imbong Vs Ochoa - G.R. No. 204819. April 8, 2014Documento234 páginasImbong Vs Ochoa - G.R. No. 204819. April 8, 2014Ebbe DyAinda não há avaliações

- Macabago Vs Comelec - G.R. No. 152163. November 18, 2002Documento8 páginasMacabago Vs Comelec - G.R. No. 152163. November 18, 2002Ebbe DyAinda não há avaliações

- Reblora Vs AFP - G.R. No. 195842. June 18, 2013Documento6 páginasReblora Vs AFP - G.R. No. 195842. June 18, 2013Ebbe DyAinda não há avaliações

- Cagas Vs Comelec - G.R. No. 194139. January 24, 2012Documento7 páginasCagas Vs Comelec - G.R. No. 194139. January 24, 2012Ebbe DyAinda não há avaliações

- Tolentino Vs Board of Accountancy - G.R. No. L-3062. September 28, 1951Documento5 páginasTolentino Vs Board of Accountancy - G.R. No. L-3062. September 28, 1951Ebbe DyAinda não há avaliações

- Ocampo Vs Tirona - G.R. No. 147812. April 6, 2005Documento8 páginasOcampo Vs Tirona - G.R. No. 147812. April 6, 2005Ebbe DyAinda não há avaliações

- Limkaichong Vs Comelec - G.R. Nos. 178831-32. April 1, 2009Documento18 páginasLimkaichong Vs Comelec - G.R. Nos. 178831-32. April 1, 2009Ebbe DyAinda não há avaliações

- Almeda vs. BathalaDocumento10 páginasAlmeda vs. BathalaPearl Angeli Quisido CanadaAinda não há avaliações

- RCBC Vs Metro Container Corp - G.R. No. 127913. September 13, 2001Documento5 páginasRCBC Vs Metro Container Corp - G.R. No. 127913. September 13, 2001Ebbe DyAinda não há avaliações

- Ibrahim Vs Comelec - G.R. No. 192289. January 8, 2013Documento8 páginasIbrahim Vs Comelec - G.R. No. 192289. January 8, 2013Ebbe DyAinda não há avaliações

- Pates Vs Comelec - G.R. No. 184915. June 30, 2009Documento5 páginasPates Vs Comelec - G.R. No. 184915. June 30, 2009Ebbe DyAinda não há avaliações

- Osmena Vs COA - G.R. No. 188818. May 31, 2011Documento6 páginasOsmena Vs COA - G.R. No. 188818. May 31, 2011Ebbe DyAinda não há avaliações

- Office of The Ombudsman Vs Ibay - G.R. No. 137538. September 3, 2001Documento5 páginasOffice of The Ombudsman Vs Ibay - G.R. No. 137538. September 3, 2001Ebbe DyAinda não há avaliações

- Limkaichong Vs Comelec - G.R. Nos. 178831-32. July 30, 2009Documento6 páginasLimkaichong Vs Comelec - G.R. Nos. 178831-32. July 30, 2009Ebbe DyAinda não há avaliações

- Malana Vs Tappa - G.R. No. 181303. September 17, 2009Documento5 páginasMalana Vs Tappa - G.R. No. 181303. September 17, 2009Ebbe DyAinda não há avaliações

- Maglente Vs Hon Baltazar-Padilla - G.R. No. 148182. March 7, 2007Documento3 páginasMaglente Vs Hon Baltazar-Padilla - G.R. No. 148182. March 7, 2007Ebbe DyAinda não há avaliações

- Teacher Commitment and Dedication to Student LearningDocumento8 páginasTeacher Commitment and Dedication to Student LearningElma Grace Sales-DalidaAinda não há avaliações

- Cuplock Scaffold 18mPHx1.6mx2.5m SafetyDocumento1 páginaCuplock Scaffold 18mPHx1.6mx2.5m SafetyDIGITAL SIRAinda não há avaliações

- Machine Tools Cutting FluidsDocumento133 páginasMachine Tools Cutting FluidsDamodara MadhukarAinda não há avaliações

- SWOT AnalysisDocumento6 páginasSWOT Analysishananshahid96Ainda não há avaliações

- Value Chain AnalysisDocumento4 páginasValue Chain AnalysisnidamahAinda não há avaliações

- Clinical Indications, Treatment and Current PracticeDocumento14 páginasClinical Indications, Treatment and Current PracticefadmayulianiAinda não há avaliações

- Ohta, Honey Ren R. - Activity 7.2 (Reflection Agriculture and Religion)Documento5 páginasOhta, Honey Ren R. - Activity 7.2 (Reflection Agriculture and Religion)honey ohtaAinda não há avaliações

- Monitoring Tool in ScienceDocumento10 páginasMonitoring Tool in ScienceCatherine RenanteAinda não há avaliações

- Irc SP 65-2005 PDFDocumento32 páginasIrc SP 65-2005 PDFAjay Kumar JainAinda não há avaliações

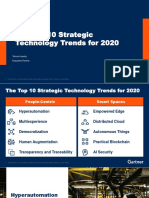

- The Top 10 Strategic Technology Trends For 2020: Tomas Huseby Executive PartnerDocumento31 páginasThe Top 10 Strategic Technology Trends For 2020: Tomas Huseby Executive PartnerCarlos Stuars Echeandia CastilloAinda não há avaliações

- Insert BondingDocumento14 páginasInsert BondingHelpful HandAinda não há avaliações

- Project Final Report: Crop BreedingDocumento16 páginasProject Final Report: Crop BreedingAniket PatilAinda não há avaliações

- Badminton Lesson 1 4 - 5 Grade: TH THDocumento31 páginasBadminton Lesson 1 4 - 5 Grade: TH THLoxcey LopezAinda não há avaliações

- 7 Equity Futures and Delta OneDocumento65 páginas7 Equity Futures and Delta OneBarry HeAinda não há avaliações

- Assessment of Benefits and Risk of Genetically ModDocumento29 páginasAssessment of Benefits and Risk of Genetically ModSkittlessmannAinda não há avaliações

- Assignment 2: Lesson Plan Analysis, Revision and Justification - Kaitlin Rose TrojkoDocumento9 páginasAssignment 2: Lesson Plan Analysis, Revision and Justification - Kaitlin Rose Trojkoapi-408336810Ainda não há avaliações

- EE114-1 Homework 2: Building Electrical SystemsDocumento2 páginasEE114-1 Homework 2: Building Electrical SystemsGuiaSanchezAinda não há avaliações

- IS 2848 - Specition For PRT SensorDocumento25 páginasIS 2848 - Specition For PRT SensorDiptee PatingeAinda não há avaliações

- Deep Learning Based Eye Gaze Tracking For Automotive Applications An Auto-Keras ApproachDocumento4 páginasDeep Learning Based Eye Gaze Tracking For Automotive Applications An Auto-Keras ApproachVibhor ChaubeyAinda não há avaliações

- Gamma World Character SheetDocumento1 páginaGamma World Character SheetDr8chAinda não há avaliações

- Strategy GlossaryDocumento15 páginasStrategy GlossaryMahmoud SaeedAinda não há avaliações

- PSAII Final EXAMDocumento15 páginasPSAII Final EXAMdaveadeAinda não há avaliações

- Rev F AvantaPure Logix 268 Owners Manual 3-31-09Documento46 páginasRev F AvantaPure Logix 268 Owners Manual 3-31-09intermountainwaterAinda não há avaliações

- Project On International BusinessDocumento18 páginasProject On International BusinessAmrita Bharaj100% (1)

- Talon Star Trek Mod v0.2Documento4 páginasTalon Star Trek Mod v0.2EdmundBlackadderIVAinda não há avaliações

- BE 510 Business Economics 1 Problem Set 5 SolutionsDocumento5 páginasBE 510 Business Economics 1 Problem Set 5 SolutionsCreative Work21stAinda não há avaliações

- Online Music QuizDocumento3 páginasOnline Music QuizGiang VõAinda não há avaliações

- 2113T Feasibility Study TempateDocumento27 páginas2113T Feasibility Study TempateRA MagallanesAinda não há avaliações

- Control Systems Engineering by S C Goyal U A Bakshi PDFDocumento3 páginasControl Systems Engineering by S C Goyal U A Bakshi PDFShubham SinghAinda não há avaliações

- MR15 Mechanical Engineering SyllabusDocumento217 páginasMR15 Mechanical Engineering Syllabusramji_kkpAinda não há avaliações