Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Lynching

Enviado por

amangondalDireitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Lynching

Enviado por

amangondalDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

History Compass 12/1 (2014): 8499, 10.1111/hic3.

12121

Lynching and Power in the United States: Southern, Western,

and National Vigilante Violence

Kathleen Belew

*

Northwestern University

Abstract

Lynching has shaped U.S. history and identity from the colonial era to the present. Recent scholarship

has expanded the periodization and geographical denition of lynching to encompass not only the South

from 1880 to 1930, but also acts of vigilante violence in the West that span a much longer history. New

scholarship treats the terrorizing and regulatory functions of lynching, but also the work that such

violence does in creating and upholding different kinds of power. Such attention to the constitutive

power of violence signals a momentous turn in the historiography, one that promises to connect histories

of vigilantism with those of empire, torture, war, rape, and other kinds of violence.

Vigilante violence has shaped the history and identity of the United States since the era of

British colonization. Lynching emerged at the same moment as the nation itself, concurrently

with its founding documents. Writing on the eve of the 1976 bicentennial, historian of

vigilantism Richard Maxwell Brown declared, Our nation was conceived and born in

violence. More recently, historian W. Fitzhugh Brundage called the act of lynching

peculiarly American. Although new transnational scholarship reveals that both lynching

and vigilantism occur in countries around the world, lynching remains as intrinsic to the

American nation as the ideas of democracy, popular sovereignty, and freedom.

1

Historians have documented incidences of vigilante violence from the late colonial period

through the twentieth century. Commonly referenced examples range from the violence of

state and state-sanctioned forces to those of private citizens. They include violence against

outlaws and criminals, social outcasts, and entire racial groups. They appear over large regions

of the United States.

2

Brundage estimated that some 4,0005,000 people have been lynched

over the course of United States history, but this number does not fully measure lynchings

impact.

3

It does not include those cases that escaped historical documentation. Neither does

it tally the victims who survived nor the communities and populations terrorized through the

lynching of particular individuals.

4

Despite its reoccurrence in U.S. history, the historiography of lynching has only recently

come into full fruition. In 1993, Brundage described the historiography of lynching in the

United States as having only recently moved beyond its infancy. This lapse extended far

beyond the discipline of history.

5

Sociologists Stewart E. Tolnay and E.M. Beck, authors

of an award-winning 1995 work on lynching, quoted historian Edward Ayers to express

their dismay at the dearth of scholarship: the triggers of lynching, for all the attention de-

voted to it by contemporaries, sociologists, and historians, are still not known.

6

The remarkable delay in fully theorized work about lynching results, in large part, from

disagreement over its denition. Until recently, the historiography focused almost entirely

on the epidemic of lynching that swept the South between 1880 and 1930.

7

The spectacle

lynchings of this period, in which black victims were most commonly tortured and hanged

before large crowds, continue to dene the act in the American imagination. Nevertheless,

2014 John Wiley & Sons Ltd

the chronological and geographic story of lynching far extends far beyond the Jim Crow

South. Not only did the triggers and histories of lynching evade thorough study for the better

part of the twentieth century, but the very denition of the act also remained contested.

Recently, however, a new generation of scholars has expanded their scale of analysis to build

upon early foundational works of lynching and vigilantism.

The Challenges of Dening Lynching

Historian Christopher Waldrep has argued, Imagining the beginnings of lynching is a

political act, one with direct repercussions for the national narrative of the United States.

8

Activists and scholars have struggled to dene what acts of violence constitute lynching

and in what regional contexts lynching is best understood.

The problem of dening lynching arises even in histories of its origins. The most cohesive

long-view work on lynching in particular, Waldreps The Many Faces of Judge Lynch: Punishment

and Extralegal Violence in America (Palgrave Macmillan, 2002), presents an overview of how

people used the word from early America until 1991, when black Supreme Court nominee

Clarence Thomas described his contentious conrmation hearings as a high-tech lynching.

Waldrep explores a longer periodization of lynching by examining two possible origin stories.

In the rst, Colonel Charles Lynch used whipping, violent interrogation, and other forceful

tactics to break miners strikes between 1776 and 1782. Waldrep describes Colonel Lynchs

activities as establishment violence carried out directly by the governing elite to protect the

wealth of Virginia. In the second, Virginia farmer WilliamLynch responded to a string of crimes

carried out by an aptly named outlaw and Tory ringleader, Benjamin Lawless, for some three

years in the early 1780s. Lynch had a personal stake in Lawlesss prosecution, and testied against

him frequently over these years, but the local court failed to deliver a conviction. William

Lynch held no position of power and was not part of the militia that eventually arose to put

down the insurrection of Lawless and the lower rank of people. Nevertheless, he became a

character in popular culture, which ascribed torture of prisoners, mock courts, and execution

to his history.

9

As evident in these twin origin myths, the denition of lynching has always been

slippery. The term has referred to the anti-labor violence of wealthy elites, the righteous

revenge of the common man, and the efforts of ordinary frontier dwellers to assert the rule of law.

The challenge of denition troubled early scholarship on vigilantism. Richard Maxwell

Brown established the eld with his foundational Strain of Violence: Historical Studies of

American Violence and Vigilantism (New York: Oxford University Press, 1975), a synthesis that

presented vigilantism as native to America. Brown argued that a shift occurred during the

Civil War: lynching ceased to signify simply the iniction of corporal punishment and became

synonymous, mainly, with hanging or killing by illegal group action.

10

Brown who pointed

out that lynching occurred in all parts of the country located this deadly shift in the transition of

the United States from a rural, agrarian nation to an urban, industrial one. He also noted that

after the Civil War, lynch mobs, which had formerly targeted petty criminals and outlaws, began

to assail a new and larger variety of victims.

11

However, Brown excluded most lynchings from his denition of vigilantism. Vigilantes, he

explained, were organized in command and often bound by a constitution or manifesto.

Lynch mobs, by contrast, he characterized as unorganized and ephemeral. Whereas

vigilantes subjected a criminal or other social outcast to what was by their lights, a fair but

speedy trial, lynch mobs simply tortured and killed their victims with little gesture toward

due process or law. Brown aligned vigilante violence, then, not with the lynch mob but rather

with a romantic ideal of frontier justice in which American men took the law into their own

hands only in places where the law and the courts could guarantee neither justice nor safety.

Lynching and Power in the United States 85

2014 John Wiley & Sons Ltd History Compass 12/1 (2014): 8499, 10.1111/hic3.12121

The aws in Browns analysis become evident in the often-blurred distinction between

organized and unorganized mobs, and in their easy substitution of social outcasts and racial

others for criminals. The lynch mobs Brown designated as ephemeral frequently staged sham

trials before carrying out executions, demonstrating adherence to a cultural idea of lynching.

12

More recent works have criticized Browns false distinction and have instead treated lynching as

a subcategory of vigilantism.

Southern, Western, and National Lynching

SOUTH

In addition to disputing which acts constitute lynching, historians have also grappled with

what geographical and chronological boundaries best dene the phenomenon. To conne

the denition of lynching to the 18801930s South serves not only to stereotype that region

as backward and corrupt, but also to romanticize Western violence and cloak the suffering of

its victims. Likewise, to begin the story in the 1880s or even in the 1840s is to elide a

longer history of violence as a constitutive power in the American nation.

The modern study of lynching emerged from contemporary activism works penned by

anti-lynching crusaders such as Ida B. Wells and Walter white and by groups like the

National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. Indeed, the very act of telling

stories about lynching led rst to organized black anti-lynching activism, and then, through

pan-generational organizing, to the long civil rights movement, as Kidada E. Williams has

recently demonstrated.

13

Both Wells and white made early claims linking lynching with

power. Wells established that criminal behavior had very little correlation with the mobs

choice of targets: the mob regularly lynched the falsely accused but only occasionally offered

an alleged crime as rationale for lynching. Both Wells and white noted the relationship

between outbursts of mob violence and economic competition, documented through the

volatile rise and fall of cotton prices from the 1890s to the 1920s.

14

Activist accounts

continued into the post-World War II period, most particularly with William L. Pattersons

edited volume We Charge Genocide: The Crimes of the Government Against the Negro People

(New York: International Publishers, 1951). Patterson invoked an emergent human rights

discourse following World War II to establish the humanity of black lynching victims and

condemned the state for failing to prevent their torture and death.

While activists analyzed relations of power, the rst professional historians to study

lynching dismissed such broad perspectives in favor of narrow, regional explanations. In

The Tragedy of Lynching (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1933), Arthur

Raper leaned heavily on bias against the South rather than offering historical argumentation.

Raper attributed Southern mob violence to backwards poor whites and blamed white elites

for failing to stop the rabble. He ignored the fact that elite whites often actively participated

in lynching. At times, he also blamed black lynching victims for their own deaths by alleging

their involvement in criminality and vice. Contrary to Wellss careful documentation, Raper

essentially attributed lynching to black crime and lax regulation of poor whites. C. Vann

Woodward began to unravel these arguments with his pivotal work The Origins of the New

South, 18771913 (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1951), which linked

populism, racism, and the idea of the South as a colony in order to explore a long period

of Southern disempowerment and its relationship to violence.

Beginning in the early 1970s, historians of Reconstruction, the Ku Klux Klan, and the Jim

Crow South advanced a still more nuanced set of arguments about Southern mob violence

than Raper had presented. In his 1984 book Vengeance and Justice, Ayers traced the sweep

of Southern lynching as it emerged from existing regional traditions of Regulator vigilantism

86 Lynching and Power in the United States

2014 John Wiley & Sons Ltd History Compass 12/1 (2014): 8499, 10.1111/hic3.12121

and problematized its periodization by studying it in tandem with other forms of Southern

violence such as dueling and whitecapping, which is to say, vigilantism ordinarily carried

out to maintain existing power structures in remote farming communities.

15

Ayers described

the South as uniquely, inherently violent even as he challenged prevailing ideas about the

periodization of lynching. Everyone today agrees on the obvious, even banal, causes of

lynching: racism, frustration, poverty, submerged political conict, irrational white fears,

and a weak state, Ayers observed.

These forces, though, were constants in the postwar South. They surely existed during Reconstruc-

tion, and yet lynching did not sweep through the region; they did not end in 1900, yet lynching

declined throughout the early twentieth century.

16

Ayers contended that lynching began as a symptom of widespread Southern crisis in the

1880s and 1890s, a period marked not only by the implementation of the new Jim Crow

racial order but also by multiple economic depressions, entry into an international market

economy, and a crime wave. Ayers identied several characteristics that had long dened

Southern society: moralism, racism, sexual tension, honor, rurality, and localistic republicanism.

After the Civil War, these traditional elements of Southern culture coupled with a declining

faith in legal systems and antagonism toward a new racial order. The result was a spree of

lynching that contributed to and exacerbated social instability in the South.

Ayers singled out the Souths entry into an international market economy, specically the

large-scale movement of white labor into cash-crop agriculture (especially cotton); the need

for large, docile labor pools for many of the Souths new industries; the emergence of

sharecropping; and the volatile rise and fall of cotton prices as contributors to the lynching

epidemic. In this way, Ayers reprised analyses about the cotton market and economic

competition rst offered by anti-lynching activists, and also retained the idea of the South

as a singular case from early historiographies of lynching.

17

However, as Brundage notes,

Ayerss frustration-aggression model elided specic local contexts: some Southern

lynchings occurred when cotton prices were good or in communities that did not produce

cotton. Ayerss model also failed to illuminate the history of U.S. lynching outside of the

South or within Southern locales that did not rely upon cotton and other cash crops.

In the late 1970s, several Southern historians began to focus on the gendered nature of

lynching. A new model inuenced by the womens rights movement and by psychoanalytic

theory located the roots of lynching more fully in white anxiety about gender and sexuality,

most particularly in the perceived threat of the archetypal black rapist to the pure white

female body. Jacquelyn Dowd Halls Revolt Against Chivalry: Jesse Daniel Ames and the

Womens Campaign Against Lynching (New York: Columbia University Press, 1979) opened

this discussion, and she soon followed with the inuential article The Mind that Burns

in Each Body: Women, Rape and Racial Violence in Powers of Desire: The Politics of

Sexuality, 1983. Hall compared lynching with rape, noting that neither act of violence has

yet been given its history and arguing that each has functioned to subjugate particular

groups of people. Hall contended that both lynching and rape have worked as instruments

of racial subordination: both became institutionalized under slavery and both found new life

as political weapons following the Civil War. She further established that the lynching wave

in the South, marked by tacit ofcial consent, corresponded to social uncertainty: Once a

new system of disenfranchisement, debt peonage, and segregation was rmly in place, mob

violence gradually declined.

18

Joel Williamsons The Crucible of Race: black/white Relations in the American South Since

Emancipation (New York: Oxford University Press, 1984) extended this gender analysis,

Lynching and Power in the United States 87

2014 John Wiley & Sons Ltd History Compass 12/1 (2014): 8499, 10.1111/hic3.12121

tracing tension about race and sexuality from 1880 to 1915. He noted that lynching most

often occurred in areas where it had happened before, in districts undergoing rapid economic

change, and in places with frequent and unpunished murders.

19

Like Ayers, he connected

lynching with other kinds of vigilantism, particularly white riots that targeted black victims

in Wilmington (1898), New Orleans (1900), and Atlanta (1906). Excellent recent accounts

have built on Williamsons work by more closely examining gender and class in relationship

to lynching. Glenda Elizabeth Gilmores cornerstone article Murder, Memory, and the

Flight of the Incubus (1998) examined the specic case of the Wilmington riot, demonstrat-

ing how the fear of the archetypal black rapist ignited white male vigilantism. Crystal

Feimsters Southern Horrors focused on womens roles in anti-lynching activism, particularly

in the life work of Ida B. Wells. Elsa Barkley Browns landmark Negotiating and

Transforming the Public Sphere: black Political Life in the Transition from Slavery to Free-

dom (Public Culture, 1994) made strikingly plain that black women, too, found themselves

victims of lynch mobs and other sorts of oppressive violence.

20

Although this brief overview essay cannot outline all of the scholarship on gender and its

relationship to vigilante violence, such work is extensive. As Mia Bay and Lisa Arellano have

argued, Ida B. Wellss anti-lynching activism succeeded precisely because of her gender; she

purposefully used her womanhood to dismantle the lynching narrative.

21

Other works on

gender explore the fraternalism of lynch mobs much-invoked chastity of white women as

justication for violence and, most recently, the participation of women in lynching and

vigilantism.

22

As the scholarship on gender developed, a new generation of revisionist historians began

to challenge the older paradigms by which Ayers and others had explained the prevalence

of Southern vigilantism between 1880 and 1930, drawing provocative new conclusions

about its causes and consequences. Their rst innovation was to recognize the disparate

and uneven nature of lynching, an act that often differed profoundly among local iterations.

Brundages Lynching in the New South: Georgia and Virginia, 18801930 (Champaign: University

of Illinois Press, 1993) attended closely both to the particularities of specic lynchings and to the

power relationships that linked and dened all such acts. Brundage, focusing on Georgia and

Virginia with admirable detail, nevertheless offered a widely applicable explanation: lynching,

he argued, was designed to preserve the status quo but varied widely from place to place. It

did not always enact a community consensus. As long as lynchings are interpreted as a

ritualized expression of the values of united white communities, Brundage noted, the task

of explaining both the great variations in the form and the ebb and ow of lynchings across

space and time will remain incomplete.

23

For Brundage, then, Southern lynching hewed

closely to articulations of local, rather than state, power. It ended, he argued, when the

Great Depression radically changed Southern agricultural systems, upending local power

structures and ushering in big government, massive labor migration, and the mechanization

of cash-crop farming.

Jacqueline Goldsbys A Spectacular Secret: Lynching in American Life and Literature (Chicago:

University of Chicago Press, 2006) further advances the study of lynching by incorporating

cultural history. Goldsby uses literature and photography because, as she notes, lynching

is both act and sign to examine Southern lynchings, pushing much further than had

earlier scholars in her consideration of culture and technology.

24

While her study remains

situated in the familiar Jim Crow era, Goldsby upends the historiography with three new

contributions. First, she describes lynching as intrinsically linked to technologies of circula-

tion and spectacle particularly photography, which became popularized around World

War I, at the same moment that photographic images of lynching were widely circulated.

25

Lynching, she further argues, should not be conceptualized as extralegal violence, but was

88 Lynching and Power in the United States

2014 John Wiley & Sons Ltd History Compass 12/1 (2014): 8499, 10.1111/hic3.12121

rather tied closely to state power over life and death, and particularly to the states denial of

black citizenship.

26

By nullifying African Americans rights of citizenship and, with them,

the afrmative duty to protect black people from unjust harm, Goldsby explains, the fed-

eral government effectively granted mobs a license to kill.

27

Finally, she cast lynching as part

of the United States transition into modernity, locating it within the economic system that

launched Americas emancipation in the twentieth century: corporate-commodity capital-

ism. Modernity, Goldsby asserts, demanded violence: lynching worked to codify particular

labor and racial orders that signied progress.

28

Rather than reading lynching as a rural, backwater,

or reactionary phenomenon, as had many other scholars, Goldsby positions it as an instrument of

state modernization.

In other words, Goldsbys interdisciplinary method rendered legible several ways in which

people who held state, racial, and economic power directly benetted from spectacle

lynchings in the 18801930 South. Not only did Southern whites benet from the racial or-

der created by lynching: but the act also worked to nullify black claims to citizenship, and

both the state and capitalism benetted from the lynchings that maintained cheap and docile

black labor. Rebecca N. Hills Men, Mobs, and Law: Anti-Lynching and Labor Defense in U.S.

Radical History (Durham: Duke University Press, 2008) created a comparative and rich history

of the interplay between vigilantism and resistance, examining anti-lynching and labor

defense violence in concert throughout American history. These revisions of Southern

exceptionalism set the stage for an even wider approach to lynching, one that would yield

rich new analyses.

WEST

A denition of lynching that includes Western vigilante violence has proven indispensable to

a comprehensive understanding of the phenomenon and a full accounting of its victims. As

historians began to dismantle Richard Maxwell Browns early division of organized

vigilantism and lynching, noticing the overlap between both categories, they also began to

study lynching outside of the 18801930 South. This shift most impacts Western historiog-

raphy, which until recently dened vigilantism as a sort of noble rough justice that was part

and parcel of settlement on the frontier. Instead, recent scholarship and photographic and

documentary collections reveal both organized and impromptu lynching in the West. These

accounts do include lynchings used to enforce law and morality, especially on the frontier,

where the state failed to deliver justice. However, they also show the repeated use of

Western lynching to police social outsiders along the lines of race, class, and gender.

By tracing the use of the word lynching itself, Waldrep delivers a particularly strong study of

lynching in California in the mid-1800s. Waldrep uses the word as it was used in that

moment, to mean an act of violence legitimate only when it represented the will of the

whole country implicitly, that is, the white male community.

29

He focuses on the San

Francisco Vigilance Committee, which purportedly endeavored to enforce the law but which

often targeted Chinese, Mexican, and other immigrant scapegoats. This committee eventually

included such numbers, and established such local power, that the governor of California

attempted to put it down as an armed revolt. After local militias added their strength to the

Committee, however, and after its members won several ofces, the San Francisco Vigilance

Committee became synonymous with local political power. By 1850, Waldrep writes, the

Western vigilante had already emerged as a stock character in ction, well on his way to

becoming a national icon. According to popular rhetoric, lynch mobs only targeted unprinci-

pled and vile men who mocked the law. No courts existed that could properly convict these

Lynching and Power in the United States 89

2014 John Wiley & Sons Ltd History Compass 12/1 (2014): 8499, 10.1111/hic3.12121

irredeemable persons, the logic went, so the burden fell on the public to exercise its popular

sovereignty through lynching.

30

Waldreps characterization of vigilantism indirectly confronts Brundages notion that

lynching did not always represent the will of a cohesive community. In California, Waldrep

claims, in the turmoil of economic competition and frontier lawlessness that surrounded the

Gold Rush, lynching frequently did nd this kind of broad community support. Indeed, the

San Francisco Vigilance Committee eventually counted more than 10,000 members, and it

created an extensive organization of the kind used by Brown to distinguish it from Southern

lynch mobs.

31

Nevertheless, Waldrep denes its activities as lynching by analyzing contempo-

rary language. While Southern and Western lynching might vary, as Arellano adds, they should

still be understood as two qualitatively different versions of the same act (emphasis added).

32

Waldrep argues that Western vigilante violence preceded Southern violence and that

Southern lynch mobs consciously followed its form. This argument problematically obscures

the early Southern history of vigilantism.

33

For instance, in Rural Radicals: Righteous Rage in

the American Grain (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1996.), Stock argues that in 1767, South

Carolina Regulators committed violence against Native Americans, religious minorities, rap-

ists, gamblers, and domestic abusers, other social outcasts in order to create and sustain power

within their own communities. These episodes occurred long before the example of Western

vigilantism could shape them.

34

Linda Gordons The Great Arizona Orphan Abduction (Cambridge: Harvard University

Press, 2001) attempted to draw connections between Southern and Western lynching,

focusing closely on violence motivated by race and labor animosities. Gordon dened

lynching as a subsection of vigilantism that served to punish and terrorize labor in order to

keep it cheap and pliant. In this way, lynching functioned either to defend systems of power,

or, especially on the frontier, to implement them. Gordon also argued that the line between

state power and vigilante violence frequently blurred, particularly during the Indian wars, in

which there was no way to distinguish military from vigilante actions.

35

NATIONWIDE

New historical works have moved beyond differentiating Southern and Western vigilantism

and have begun instead to conceptualize a broad, national history of lynching as concurrent

with the formation and expansion of the United States. In Rural Radicals, Stock examines

vigilantism as a tradition of rural life in the United States. She divides vigilantism into

three broad, overlapping categories. First, Americans on the frontier attacked deviants,

criminals, poor people, and others whose behaviors or beliefs threatened the physical safety

and/or economic stability of the community. Second, settlers and other rural Americans

targeted people whose racial heritage they deemed intolerable. Third, communities turned

violent against those they saw as un-American because of religious or ethnic heritage or

political beliefs.

36

Stocks central argument that vigilantism is an inherently rural phenomenon tied to the

isolation and deprivation of the frontier, the enforced homogeneity of the small town, and

the wide availability [of] and reverence for guns runs counter to Goldsbys argument

about the simultaneous development of lynching, modernism, and technology between

1890 and 1915. It also clashes with the assertions of Southern historians that the

18801930 lynching peak coincided with dramatic decreases in both isolation and deprivation,

especially in the South. By 1890, 90% of Southerners lived in counties with railroads,

signaling an unprecedented level of connection.

37

Furthermore, as Ayers noted, lynching

90 Lynching and Power in the United States

2014 John Wiley & Sons Ltd History Compass 12/1 (2014): 8499, 10.1111/hic3.12121

victims were usually traveling laborers or transients: their lynching resulted in part from the

circulation of strangers created by technologies like the railroad rather than from isolation.

38

Stock not only contradicts Ayerss and Goldsbys notions about lynching as a consequence

of modernity and Southern transformation, but also disputes Brundages assertion that

lynching did not signify community consensus. Stock asserts that lynching was

supported and sustained over many years by most or all members of the white community,

including women. Lynch mobs were not sudden, irrational actions provoked by years of frontier

assault and revenge, nor were they organizations that took on an immediate problem and then

(sometimes at least) disbanded.

Stock describes all vigilante violence as a product of the community, but lynching as a

coherent form of crowd violence that included members of the elite. Lynching, she

argues, served to shore up local structures of power over the span of several years. Like

Goldsby, she emphasizes the spectacular nature of such events in creating fear among

victimized populations.

39

New periodizations of lynching have led to new ideas about why lynching occurred.

Michael J. Pfeifers Rough Justice: Lynching and American Society: 18741947 (University of

Illinois, 2004) utilizes a slightly condensed version of Waldreps timeline but offers a statistical

analysis of vigilantism. Like Waldrep, Pfeifer draws hard lines between Southern and Western

episodes, or in Pfeifers terms, between Southern lynching and Western mob violence. He

argues that both resulted from a nationwide transition from rural rough justice to urban-

and middle-class due process, a movement that incorporated regions sporadically: rst the West

and then the South lagging behind. While his data are impressive, his analysis is necessarily lim-

ited by his case studies. Louisiana, for instance, stands in for the entire South. His decision to

include only lethal lynchings regrettably foreshortens discussions of a complex form of crowd

violence: as other scholars have documented, lynching did not always prove fatal. Like

Waldrep, Pfeifer gestures to the present moment by arguing that the death penalty is now

disproportionately employed in the same communities that most recently used lynching to

preserve the order of dominant power systems. Capital punishment, Pfeifer provocatively

concludes, has signaled a bureaucratization, rather than tempering, of American violence.

40

While early works on Western lynching worked on a regional model, demarcating the

border between Western and Southern mob violence, Lisa Arellano advances a much

broader argument about geography. In Vigilantes and Lynch Mobs: Narratives of Community

and Nation (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2012), she argues that scholars have until

recently drawn a false distinction between Western and Southern lynching. In so doing, they

have remained complicit in the veneration of potentially legitimate and order-making

extralegal violence in its Western shape, even while decrying the same phenomenon in

the South. For Arellano, Browns early distinction between vigilantism and lynching thus

created ethical concerns. Arellano also demonstrates that academic historians were only a

few of the many voices that informed popular understandings of lynching over the course

of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Perpetrators of mob violence, who justied their

actions in written accounts, shaped this discourse as well.

Arellanos book is the most notable example of a new turn in the historiography of

lynching, one that seeks to more thoroughly interrogate power within the act itself. She sees

lynching as a set of violent practices made recognizable by a constellation of formulaic

narrative practices. Arellano argues that a lynching is discernable by the claims of its

perpetrators, who allege that their acts served to punish criminals. She identies ve

narrative attributes that distinguish lynchers accounts of their deeds: overwhelming

Lynching and Power in the United States 91

2014 John Wiley & Sons Ltd History Compass 12/1 (2014): 8499, 10.1111/hic3.12121

crime, failure of the state, valorous action, pursuit of orderliness, and public popular-

ity.

41

Lynching, Arellano argues, was the same in the nineteenth century as in the

twentieth and more similar than different in the South and in the West. Rather than

trying to formulate distinctions between mob violence in various regions or even

within these regions, as did Brundage Arellano advances a broader denition and

periodization of lynching. In so doing, she enables new consideration of the relationship

between vigilantism and power.

Accounts of lynching that follow a broader denition and periodization have opened rich

terrain for further study. The popular photography exhibit and eponymous folio book

Without Sanctuary: Lynching Photography in America (Santa Fe: Twin Palms Publishers, 2000)

displays images of lynchings conducted in the Souths iconic 18901930 period alongside

those from other times and places. Waldreps edited collection Lynching in America: A History

in Documents (New York: New York University Press, 2006) follows suit by presenting

documents that span the new periodization and broader map of U.S. lynching. In both

collections, striking resemblances between Southern and Western lynching, and between

pre- and post-Reconstruction lynching, work to create a longer and fuller perspective on

the act.

42

Vigilantism and Power

Collectively, these and other works document a fuller history of lynching and its many

perpetrators, victims, and consequences. They also raise challenging questions about the

complicated relationship between vigilante violence and several forms of power. The

question of how to describe this relationship resonates throughout the historiography.

Perhaps vigilantism can be most clearly understood as group violence that serves systemic

power. I borrow systemic from George Lipsitz, who uses the term to identify not only

overt power wielded by the state but also subtle power exerted by the many informal

structures that uphold it.

43

When the state is weak, sytemic power often patriarchal, racial,

or religious commonly prevails. Historically, systemic power in the United States has

tended to privilege white men with property. Only persons who claim systemic power, I

argue, can carry out vigilante violence such as lynching. Extralegal political violence carried

out by persons who do not possess systemic power is not properly understood as vigilantism

because it typically seeks to negate, undermine, or overthrow the power of the state. The

violence of systematically disempowered persons is frequently better understood as resistance,

self-defense, or revolution.

44

Similarly, extralegal personal violence vengeance can

function without relation to power, often under its own set of governing principles. While

vengeance is frequently invoked to justify vigilantism, the latter is distinguished by its effect:

shoring up or constituting systemic power.

Several recent works on lynching have also illuminated the constitutive power of vigilante

violence that is, the way that lynching works to create power rather than merely uphold it.

In The Only Badge Needed Is Your Patriotic Fervor: Vigilance, Coercion, and the Law in

World War I America (The Journal of American History, March 2002, 13541382),

Christopher Capozzola argues that vigilantism, rather than being an exercise of violent

power, is instead about law. In his study of popular mobilization for World War

I, he demonstrates that vigilantism functioned to establish social order. During that war, the

U.S. government brought citizen policing under state authority and in line with state

objectives, thereby transforming the nature of vigilantism during and after war.

45

Because the

historical record offers myriad examples of vigilantism that benetted the state both in times

of war and during long periods of peace, Capozzolas argument might be fruitfully expanded:

there is space at this juncture for further scholarship. Capozzola nonetheless makes the case that

92 Lynching and Power in the United States

2014 John Wiley & Sons Ltd History Compass 12/1 (2014): 8499, 10.1111/hic3.12121

the U.S. government has used vigilantism to regulate its populace during wartime, turning

lynching into one element of state power.

Likewise, Goldsby elucidates the difference between lynching as mere social regulation

and lynching as the systematic terrorization of a particular racialized subject, meant to stand

in for state oppression of an entire racial group. She sees Reconstruction, rather than the

1890s, as the crucible in which lynching turned deadly. She argues,

By the end of Reconstruction, the nature and aim of lynching had changed perceptibly. What had

once been an exacting and painful measure of social regulation became a mortal tactic of political

terrorism, targeted to reverse the gains won by blacks because of emancipation.

46

In other words, Goldsby identies a shift from the use of lynching to police criminals and

social outcasts to the use of lynching to designate entire racial groups as vulnerable to

violence. Goldsby argues that lynching worked both to establish and to maintain a racial

hierarchy understood here as inexorably tied to state power.

Here, the historiography of lynching dovetails with excellent emerging work in Latina/o

studies, history, and anthropology about the U.S.Mexico border, most particularly on the

violent project of subjugating Mexicans and Mexican Americans in Texas, together

referred to as Tejanos following the Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo in 1848. New histories

of vigilantism in South Texas bridge the geographical divide between Southern and Western

studies of lynching. These accounts reveal a blurry line between state-sanctioned and

extralegal violence, recognizing a long continuum between the actions of private citizens

and those of the Texas Rangers and other public authorities. Benjamin Heber Johnsons

pivotal work Revolution in Texas: How a Forgotten Rebellion and Its Bloody Suppression Turned

Mexicans into Americans (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2003) details the attempted

191516 revolution by ethnic Mexicans in South Texas under the Plan de San Diego, and

the far bloodier counterinsurgency carried out by Texas Rangers, law and order leagues,

and private mobs that killed between 300 and 5,000 Tejanos in the same period. During

World War I, this violence rose to such a nationalistic fervor that the military intervened

to reclaim the rule of law from lynch mobs and posses. After the war, in the 1920s, the

anti-Mexican Ku Klux Klan revived local vigilantism.

47

Johnsons argument, in fact, identies many of the same factors that contributed to

Southern lynching. For instance, when South Texas shifted from cattle ranching to cotton

production in the years just before its vigilante period, many Tejanos became eld laborers.

The region therefore shared a similarly volatile commercial agriculture system with the

South. And as in the South, vigilantism worked to install a system of harsh racial segregation

and to deliver a massive and tightly managed labor force.

48

Claiming that existing legal systems could not stop Mexican bandits or revolutionaries,

white South Texans justied their lynchings much as Western vigilantes did. Texas lynch

mobs made lists targeting not only rebels and bandits but also all Tejanos of bad character,

including unruly women and other social outcasts.

49

By intimidating voters and breaking

strikes, Texas vigilantes helmed in large part by the Texas Rangers delivered full political

power and racial privilege to Anglo residents.

50

William D. Carrigans The Making of a Lynching Culture: Violence and Vigilantism in Central

Texas, 18361916 (University of Illinois Press, 2004) more directly takes Texas as a case

study of the intersection of Southern and Western histories. He analyzes a regional tolerance

of mob violence, tailoring his account around four major developments: the rhetoric of self-

defense along the expanding frontier; the day-to-day violence of slavery; the resistance and

suppression of ethnic, political, and racial minorities; and the tacit consent of the courts.

Lynching and Power in the United States 93

2014 John Wiley & Sons Ltd History Compass 12/1 (2014): 8499, 10.1111/hic3.12121

All of these factors, Carrigan shows, contributed to the culture of mob violence in Central

Texas. Carrigans work expands ideas of lynching from those used to structure Southern

history, calling early attention to the lynching of Mexicans and Mexican Americans and

Indians and social outcasts.

Carrigan and Clive Webbs new Forgotten Dead: Mob Violence against Mexicans in the United

States, 18481928 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013) widens its scope of analysis

beyond Texas to the larger borderlands region. Carrigan and Webb create a new list of

documented lynchings of Mexicans and Mexican Americans, lling in the archival gaps left

by the absence of such activist organizations, in the West, as the National Association for the

Advancement of Colored People and Tuskegee University that collected data on black

lynching victims in the South. They also focus on attempts at transnational justice for lynching.

They draw on previously un- and under-used sources, including oral histories, photography,

and Mexican diplomatic records, to recongure the periodization of lynching: most Mexican

and Mexican American victims were lynched prior to the beginning of the Southern epidemic.

New work by Monica Muoz Martinez deepens the study of Mexican American lynching

by revealing the spectacle of dead and mutilated bodies on the South Texas physical and

cultural landscape. She discovers that postcards depicting the lynchings of Tejanos circulated

through the region, mirroring the phenomenon Goldsby documented in the South.

Muoz Martinez also examines the lived memory of lynching in South Texas for instance,

the display, to the present day, of lynching photographs in local restaurants and asks how

such images continue to shape race and gender relations. Finally, as do Carrigan and Webb,

Muoz Martinez examines transnational attempts to secure justice for the victims of

vigilante violence, particularly in the case of Tejano families who crossed the border to seek

advocacy from the Mexican government, and sometimes won damages from the United

States government for the lynching of their loved ones. She therefore extends our

understanding of both the people impacted by lynching and the actors responsible,

revealing how vigilante violence stretches across generations and continues to shape local

and national histories.

51

Conclusion

Lynching, its denitions, and its periodization remain pressing problems both for historians of

the United States and for those who hope to understand the current political moment.

Clarifying lynching as an act intrinsically tied to the creation and maintenance of power

has opened broad spaces for new scholarship. Expanding chronological and geographical

denitions made possible by the use of interdisciplinary methods and the advent of new

elds such as cultural history, performance studies, and postcolonial studies has revealed

the constitutive, regulatory, and terrorizing capacity of lynching violence not only in the

Jim Crow South but also in the West and on the U.S.Mexico border. Viewed historically,

lynching may be understood as a national form of violence that has shaped the United States

from colonization through the twentieth century. Hill and Pfeifer both connect lynching

to the death penalty; the burgeoning eld of carceral studies calls for the continued

examination of violence and systemic power. Further work might problematize relation-

ships of power within acts of vigilantism and more fully explore the interplay between

lynching and American identity. Recent transnational studies continue to belie the notion

that lynching is peculiarly American, but its peculiar place in American history is now

well documented.

The study of lynching is as important to an understanding of the workings of the state as is

scholarship on empire, war, torture, and other forms of state violence. Indeed, understanding

94 Lynching and Power in the United States

2014 John Wiley & Sons Ltd History Compass 12/1 (2014): 8499, 10.1111/hic3.12121

vigilante violence as a state-sanctioned activity shows how power has constituted and

regulated particular communities and how it has subjugated and terrorized specic peoples.

Such an understanding brings violence committed by the United States against foreign

peoples in the Philippines, Korea, and Vietnam, for instance into conversation with

the subjugation of black, Mexican American, Chinese, female, and queer bodies by domestic

vigilantes. Properly understood, vigilante violence serves as a nexus connecting histories of

race, empire, gender, class, and sexuality.

Even now, lynching and the confusion around its denition continue to shape politics. In

the heady early days of the Occupy Wall Street movement in 2011 and 2012, police ofcers

arrested two protesters, one in Los Angeles and another in Oakland, and charged them with

lynching. Section 405(a) of the California penal code dened lynching as the taking by

means of a riot of any person from the lawful custody of any peace ofcer. Police ofcers

alleged that Sergio Ballasteros had interfered in the arrest of a third party and that Tiffany

Tran, upon her arrest, had cried for help. As California police interpreted the law, Ballasteros

and Tran had lynched; Tran had lynched herself. While these felony charges were quickly

dropped, their use to suppress democratic protest shows a continued intertwinement of

lynching and power. The charges wholly obscured the legislative history of Section 405(a)

and the broader history of lynching violence in the state. Whereas in the 1850s, private

California citizens purportedly used lynching to enforce the law, and in the 1930s,

Section 405(a) attempted to stop mobs from taking suspects from police custody in

order to lynch them, in the 2010s, California law enforcement ofcials charged private

citizens with lynching in order to suppress civil disobedience carried out in legal political

protests.

52

The long entanglement between state power and vigilantism continues, demanding

further scholarly attention.

Short Biography

Kathleen Belew (PhD in American Studies, Yale University, 2011) specializes in the history

of the United States after the Vietnam War, examining the wars long aftermath on the

American home front. As a postdoctoral fellow in History at Northwestern University,

she teaches courses on the American Vigilante, Histories of Violence in the United States,

the Vietnam War, Twentieth Century U.S. History, and Comparative Race and Racism.

Her work has received the support of the Andrew W. Mellon and Jacob K. Javits Founda-

tions and Albert J. Beveridge and John F. Enders support for her transnational research in

Mexico and Nicaragua.Her rst book, Bring the War Home: How Vietnam Veterans Ignited

the Radical Right (under contract, Harvard University Press), traces the circulation of vio-

lence from the Vietnam War, to Central America, to the United States, following a small

but inuential group of veterans who became mercenary soldiers and then joined racist right

groups at home. Their white power movement united Klansmen, neo-Nazis, skinheads,

proponents of Christian Identity, and more declared war on the government in 1983 and

reshaped itself as the purportedly nonracist militia movement in the 1990s. Belew examines

the relationship between veterans and vigilante movements throughout the twentieth cen-

tury, circulations of military weapons and technology, and connections between seemingly

disparate racist groups. Originally from Colorado, Belew earned her BA in Comparative

History of Ideas from the University of Washington in 2005, where she was named Deans

Medalist in the Humanities. She has also taught at Yale University, Rutgers University, and

the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. Her second project, a long cultural history of the

American vigilante from early America to the present, emphasizes the constitutive power of

violence in nation-building.

Lynching and Power in the United States 95

2014 John Wiley & Sons Ltd History Compass 12/1 (2014): 8499, 10.1111/hic3.12121

Notes

* Correspondence: Department of History, Northwestern University, Evanston, IL, USA. Email: k-belew@northwestern.edu.

1

Special thanks to Simeon Man, Beth Lew-Williams, Geraldo Cadava, Kate Masur, Dylan Penningroth, Benjamin Heber

Johnson, and especially Bejamin H. Irvin for their generous feedback on this essay.Waldrep, The Many Faces of Judge Lynch,

10, 21; Brown, Strain of Violence, vii, 5; Brundage, Lynching in the New South, 3. On a transnational approach to lynching schol-

arship, see, for instance, Godoy, Lynchings and the Democratization of Terror in Postwar Guatemala: Implications for Human

Rights, 640661.

2

Stock, Rural Radicals: Righteous Rage in the American Grain; Gordon, The Great Arizona Orphan Abduction; Brown, Strain

of Violence; Waldrep, Many Faces of Judge Lynch. Adding other massacres to this list, see also blackhawk, Violence over the

Land; Jacoby, Shadows at Dawn.

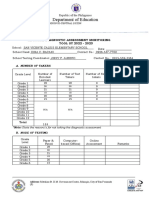

Table of commonly referenced incidents of vigilante violence in U.S. history

Time Place Perpetrators Victims

1676 Colonies Settlers (Bacons Rebellion) Native Americans

1763 Pennsylvania Paxton Boys Native Americans

17671769 Carolinas The Regulators Outlaws, social outcasts

17761780 Virginia piedmont Colonel Lynch and mob Striking coal miners

1820twentieth

century

Texas Texas Rangers Mexicans, Mexican Americans,

and Indians

1832 Missouri State militias, townspeople Mormons

1835 Vicksburg, Mississippi Townspeople Gamblers

18541861 Bleeding Kansas Supporters of slavery Abolitionists

1856 California San Francisco Vigilance

Committee

Mexicans, Chinese, social outcasts

1863 Montana Masons Outlaws

1864 Colorado Mob and military men

(Sand Creek Massacre)

Indians

1866present South, then

nationwide

Ku Klux Klan blacks, foreigners, deviants, social

outcasts, Jews, scapegoats

1887 Indiana white Caps Social outcasts

19151920s Nationwide WWI Vigilance Committees Immigrants and communists

19041917 Arizona and Colorado Mining companies Non-whites, labor activists, striking

workers

3

Brundage, Lynching in the New South, 259.

4

Herman, Trauma and Recovery, 187.

5

Brundage, Lynching in the New South, 8.

6

Tolnay and Beck, A Festival of Violence, 246, quoting Ayers, Vengeance and Justice, 238.

7

Brundage, Lynching in the New South, 8.

8

Waldrep, Many Faces of Judge Lynch, 13.

9

Waldrep, Many Faces of Judge Lynch, 1923.

10

Brown, Strain of Violence, 21.

11

Brown also included explicit links between vigilantism and state power, noting Andrew Jacksons condonement of vigi-

lantism in Iowa and Teddy Roosevelts unsuccessful attempt to join a vigilante group in North Dakota Strain of Violence, 23.

12

Brown, 109110.

13

Williams, They Left Great Marks on Me.

14

Wells, Southern Horrors and Other Writings; white, Rope and Faggot; Feimster, Southern Horrors, 90. On the economic

volatility of this period, see also Jacobson, Barbarian Virtues, Chapter 1.

15

Ayers, Vengeance and Justice, 164.

16

Ayers, Vengeance and Justice, 238.

17

Ayers, Vengeance and Justice, 250252, 4, 1589, 225.

18

Hall, The Mind that Burns in Each Body: Women, Rape and Racial Violence, 328349. Here, too, historians

built on earlier works by activists, particularly the body of writings produced by Lillian Smith in the late 1940s and early

1950s. Hall also notes that the study of lynching was immediately familiar to feminists who worked in the anti-rape

movements of the 1970s and 1980s.

96 Lynching and Power in the United States

2014 John Wiley & Sons Ltd History Compass 12/1 (2014): 8499, 10.1111/hic3.12121

19

Williamson, The Crucible of Race, Chapter 6.

20

Gilmore, Murder, Memory and the Flight of the Incubus, 7393; Feimster, Southern Horrors; Barkley Brown,

Negotiating and Transforming the Public Sphere.

21

Arellano, Vigilantes and Lynch Mobs; Bay, To Tell the Truth Freely.

22

On the participation of women in vigilante violence, see Irvin, Tar, Feathers, and the Enemies of American

Liberties, 17681776; Waldrep, Lynching in America: A History in Documents; Gordon, Great Arizona Orphan Abduction;

McLure, I Suppose You Think Strange the Murder of Women and Children: The American Culture of Collective Violence,

16521930. On the defense of white female bodies as justication for racial violence, see also Pascoe, What Comes Naturally.

23

Brundage, Lynching in the New South, 13, 19.

24

Goldsby, A Spectacular Secret, 42.

25

Goldsby, A Spectacular Secret, 5, 218.

26

Goldsby, A Spectacular Secret, 283.

27

Goldsby, A Spectacular Secret, 17.

28

Goldsby, A Spectacular Secret, 216.

29

Waldrep, Many Faces of Judge Lynch.

30

Waldrep, Many Faces of Judge Lynch, 24, 50.

31

Waldrep, Many Faces of Judge Lynch, 55.

32

Arellano, Vigilantes and Lynch Mobs, 120.

33

Arellano, Vigilantes and Lynch Mobs 723; see, for instance, Brown, The South Carolina Regulators.

34

Stock, Rural Radicals, 9395.

35

Gordon, Great Arizona Orphan Abduction, 2612.

36

Stock, Rural Radicals, 89.

37

Ayers, Southern Crossings, Chapter 1.

38

Stock, Rural Radicals; Ayers, Southern Crossings.

39

Stock, Rural Radicals, 126.

40

Pfeifer, Rough Justice, 3, 10, 14950.

41

Arellano, Vigilantes and Lynch Mobs, 2425.

42

See also Apel, On Looking: Lynching Photographs and Legacies of Lynching after 9/11, American Quarterly, Vol. 55,

No. 3 (September 2003) pp. 457478.

43

Lipsitz, The Possessive Investment in whiteness, 381.

44

There are some exceptions, such as black lynch mobs, see Hill, black Vigilantism: The Rise and Decline of black

Lynch Mob Activity in the Mississippi and Arkansas Deltas, 18831923. Further, one disempowered group could lynch

someone from another, if it were still in the service of systemic power. The difference is the relationship to power rather

than the positionality of the actor.

On revolutionary violence, see Fanon, Wretched of the Earth, Chapter 1; Benjamin, Critique of Violence. On armed

self-defense, see also Tyson, Radio Free Dixie.

45

Capozzola, The Only Badge Needed Is Your Patriotic Fervor: Vigilance, Coercion, and the Law in World War I

America, 13611379.

46

Goldsby, Spectacular Secret, 230.

47

The historiography of the Ku Klux Klan as a particular vigilante group falls out of the scope of this brief essay. See, for

instance, Wade, The Fiery Cross, 219; Schlatter, Aryan Cowboys, 64; Woodward, Origins of the New South, 110;

Kantrowitz, Ben Tillman and the Reconstruction of white Supremacy; MacLean, Behind the Mask of Chivalry, xii, 184, 188.

48

Johnson, Revolution in Texas, 15, 3, 335, 40, 1634.

49

On unruly women as targets of lynch mobs, see also Gordan, Great Arizona Orphan Abduction, 263.

50

Johnson, Revolution in Texas, 1089, 115, 86, 178, 173. See also Gordon, Great Arizona Orphan Abduction, 271.

51

Martinez, Inherited Loss: Tejanas and Tejanos Contesting State Violence and Revising Public Memory, 1910-Present.

52

Albrecht, Lynching Not Always about Racial Violence; Mikultran, Occupier Charged with Lynching Herself;

Huus, Prosecutors Aim New Weapon at Occupy Activists: Lynching Allegation; California Penal Code Section 405

(a); jpmassar, Occupied Oakland: Now Come the Low-tech Lynchings.

Bibliography

Albrecht, Leslie, Lynching Not Always about Racial Violence, Merced Sun-Star, 5 April, 2009. Retrieved on 9 July 2012

from: http://www.mercedsunstar.com/2009/04/02/775031/lynching-not-always-about-racial.html#storylink=cpy

Allen, James, et al.,Without Sanctuary: Lynching Photography in America, (Santa Fe, New Mexico: Twin Palms, 2000).

Apel, Dora, On Looking: Lynching Photographs and Legacies of Lynching after 9/11, American Quarterly, 55(3) (2003):

457478.

Lynching and Power in the United States 97

2014 John Wiley & Sons Ltd History Compass 12/1 (2014): 8499, 10.1111/hic3.12121

Arellano, Lisa, Vigilantes and Lynch Mobs: Narratives of Community and Nation (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2012).

Ayers, Edward L., Southern Crossings: AHistory of the American South, 18771906 (NewYork: Oxford University Press, 1995).

Ayers, Edward L., Vengeance and Justice: Crime and Punishment in the 19th-Century American South (Oxford: Oxford

University Press, 1984).

Barkley Brown, Elsa, Negotiating and Transforming the Public Sphere: black Political Life in the Transition fromSlavery to

Freedom, Public Culture, 7(1) (Fall 1994): 107146.

Bay, Mia, To Tell the Truth Freely: The Life of Ida B. Wells (New York: Hill and Wang, 2010).

Benjamin, Walter, Critique of Violence, Selected Writings Volume 1 (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1996).

Blackhawk, Ned, Violence over the Land: Indians and Empires in the Early American West (Cambridge: Harvard University

Press, 2008).

Brown, Richard Maxwell, Strain of Violence: Historical Studies of American Violence and Vigilantism (New York: Oxford

University Press, 1975).

Brown, Richard Maxwell, The South Carolina Regulators (Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University

Press, 1963).

Brundage, W. Fitzhugh, Lynching in the New South: Georgia and Virginia, 18801930 (Urbana and Chicago: University of

Illinois Press, 1993).

California Penal Code Section 405(a). Retrieved on 9 July 2012 from: http://law.onecle.com/california/penal/405a.

html

Capozzola, Christopher, The Only Badge Needed Is Your Patriotic Fervor: Vigilance, Coercion, and the Law in

World War I America, Journal of American History, 88:4 (2002): 13541382.

Carrigan, William D., and Webb, Clive, Forgotten Dead: Mob Violence against Mexicans in the United States, 18481928

(Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013).

Carrigan, William D., The Making of a Lynching Culture: Violence and Vigilantism in Central Texas, 18361916 (Urbana:

University of Illinois Press, 2004).

Fanon, Frantz, On Violence, Wretched of the Earth, Chapter 1 (New York: Grove Press, reprint 2005).

Feimster, Crystal N., Southern Horrors: Women and the Politics of Rape and Lynching (Cambridge: Harvard University

Press, 2011).

Gilmore, Glenda Elizabeth, Murder, Memory and the Flight of the Incubus, in David S. Cecelski and Timothy B. Tyson

(eds.), Democracy Betrayed: The Wilmington Race Riot and Its Legacy (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1998).

Godoy, Angelina Snodgrass Godoy, Lynchings and the Democratization of Terror in Postwar Guatemala: Implications

for Human Rights, Human Rights Quarterly, 24(3) (2002): 640661.

Goldsby, Jacqueline, ASpectacular Secret: Lynching in American Life and Literature (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2006).

Gordon, Linda, The Great Arizona Orphan Abduction (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2001).

Hall, Jacqueline Dowd, Revolt Against Chivalry: Jesse Daniel Ames and the Womens Campaign Against Lynching.

(New York: Columbia University Press, 1979).

Hall, Jacqueline Dowd, The Mind that Burns in Each Body: Women, Rape and Racial Violence, in Ann Snitow,

Christine Stansell, and Sharon Thompson (eds.), Powers of Desire: The Politics of Sexuality (New York: Monthly

Review Press, 1983), 328349.

Herman, Judith, Trauma and Recovery (New York: Basic Books, 1997).

Hill, Karlos K., Black Vigilantism: The Rise and Decline of black Lynch Mob Activity in the Mississippi and Arkansas

Deltas, 18831923, The Journal of African American History, 95(1) (Winter 2010): 2643.

Hill, Rebecca N, Men, Mobs, and Law: Anti-lynching and Labor Defense in U.S. Radical History (Durham: Duke

University Press, 2008).

Huus, Kari, Prosecutors Aim New Weapon at Occupy Activists: Lynching Allegation, MSNBC, 17 January, 2012.

Retrieved on 9 July 2012 from: http://www.mercedsunstar.com/2009/04/02/775031/lynching-not-always-

about-racial.html#storylink=cpy

Irvin, Benjamin H., Tar, Feathers, and the Enemies of American Liberties, 17681776, The New England Quarterly, 76(2)

(2003): 197238.

Jacobson, Matthew Frye, Barbarian Virtues: The United States Encounters Foreign Peoples at Home and Abroad, 18761917

(New York: Hill and Wang, 2000).

Jacoby, Karl, Shadows at Dawn: An Apache Massacre and the Violence of History (New York: Penguin, 2009).

Johnson, Benjamin Heber, Revolution in Texas: How a Forgotten Rebellion and Its Bloody Suppression Turned Mexicans into

Americans (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2003).

jpmassar, Occupied Oakland: Now Come the Low-tech Lynchings, The Daily Kos, 7 January, 2012. Retrieved on 17 July

2013 from: http://www.dailykos.com/story/2012/01/07/1052484/-Occupied-Oakland-Now-Come-the-Low-Tech-

Lynchings

Kantrowitz, Stephen, Ben Tillman and the Reconstruction of white Supremacy (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina

Press, 2000).

98 Lynching and Power in the United States

2014 John Wiley & Sons Ltd History Compass 12/1 (2014): 8499, 10.1111/hic3.12121

Lipsitz, George, The Possessive Investment in whiteness: How white People Prot From Identity Politics (Philadelphia: Temple

University Press, 1998).

MacLean, Nancy, Behind the Mask of Chivalry: The Making of the Second Ku Klux Klan (New York: Oxford University

Press, 1994).

Martinez, Monica Muoz, Inherited Loss: Tejanas and Tejanos Contesting State Violence and Revising Public

Memory, 1910-Present, Doctoral Dissertation, Yale University, 2012.

McLure, Helen, I Suppose You Think Strange the Murder of Women and Children: The American Culture of

Collective Violence, 16521930, Doctoral Dissertation, Southern Methodist University, 2009.

Mikultran, Occupier Charged with Lynching Herself, The Shrine of Dreams, (January 2012) Retrieved on 9 July 2012

from: http://shrineodreams.wordpress.com/2012/01/02/occupier-charged-with-lynching-herself/

Pascoe, Peggy, What Comes Naturally: Miscegenation Law and the Making of Race in America (Oxford: Oxford University

Press, 2009).

Patterson, William L, We Charge Genocide: The Historic Petition to the United Nations for Relief From a Crime of the United

States Government Against the Negro People (The Civil Rights Congress, 1951).

Pfeifer, Michael J., Rough Justice: Lynching and American Society: 18741947 (Urbana: University of Illinois, 2004).

Raper, Arthur F, The Tragedy of Lynching (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1933).

Schlatter, Evelyn A., Aryan Cowboys: white Supremacy and the Search for a New Frontier, 19702000 (Austin: University of

Texas Press, 2006).

Stock, Catherine McNichol, Rural Radicals: Righteous Rage in the American Grain (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1996).

Tolnay, Stewart, and Beck, E. M., A Festival of Violence: An Analysis of Southern Lynchings, 18821930 (Urbana and

Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1995).

Tyson, Timothy B., Radio Free Dixie: Robert F. Williams & the Roots of black Power (Chapel Hill: University of North

Carolina Press, 1999).

Wade, Wyn Craig, The Fiery Cross: the Ku Klux Klan in America (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1987).

Waldrep, Christopher, Lynching in America: A History in Documents (New York: New York University Press, 2006).

Waldrep, Christopher, The Many Faces of Judge Lynch: Punishment and Extralegal Violence in America (New York: Palgrave

Macmillan, 2002).

Wells, Ida B., Southern Horrors and Other Writings (New York: Bedford/St. Martins, 1997).

White, Walter, Rope and Faggot: A Biography of Judge Lynch (Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame, 2001).

Williams, Kidada E., They Left Great Marks on Me (New York: New York University Press, 2012).

Williamson, Joel, The Crucible of Race: black/white Relations in the American South Since Emancipation (New York: Oxford

University Press, 1984).

Woodward, C. Vann, The Origins of the New South, 18771913 (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1951).

Lynching and Power in the United States 99

2014 John Wiley & Sons Ltd History Compass 12/1 (2014): 8499, 10.1111/hic3.12121

Você também pode gostar

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5783)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (119)

- Variety July 19 2017Documento130 páginasVariety July 19 2017jcramirezfigueroaAinda não há avaliações

- 50 Compare Marine Insurance and General InsuranceDocumento1 página50 Compare Marine Insurance and General InsuranceRanjeet SinghAinda não há avaliações

- What Does The Bible Say About Hell?Documento12 páginasWhat Does The Bible Say About Hell?revjackhowell100% (2)

- Phoenix Journal 042Documento128 páginasPhoenix Journal 042CITILIMITSAinda não há avaliações

- Understanding Risk and Risk ManagementDocumento30 páginasUnderstanding Risk and Risk ManagementSemargarengpetrukbagAinda não há avaliações

- How Companies Can Flourish After a RecessionDocumento14 páginasHow Companies Can Flourish After a RecessionJack HuseynliAinda não há avaliações

- English Final Suggestion - HSC - 2013Documento8 páginasEnglish Final Suggestion - HSC - 2013Jaman Palash (MSP)Ainda não há avaliações

- Evolution of Local Bodies in IndiaDocumento54 páginasEvolution of Local Bodies in Indiaanashwara.pillaiAinda não há avaliações

- A History of Oracle Cards in Relation To The Burning Serpent OracleDocumento21 páginasA History of Oracle Cards in Relation To The Burning Serpent OracleGiancarloKindSchmidAinda não há avaliações

- Green BuildingDocumento25 páginasGreen BuildingLAksh MAdaan100% (1)

- Joint Admissions and Matriculation Board: Candidate DetailsDocumento1 páginaJoint Admissions and Matriculation Board: Candidate DetailsShalom UtuvahweAinda não há avaliações

- Tax Invoice / Receipt: Total Paid: USD10.00 Date Paid: 12 May 2019Documento3 páginasTax Invoice / Receipt: Total Paid: USD10.00 Date Paid: 12 May 2019coAinda não há avaliações

- UCSP Exam Covers Key ConceptsDocumento2 páginasUCSP Exam Covers Key Conceptspearlyn guelaAinda não há avaliações

- New General Education Curriculum Focuses on Holistic LearningDocumento53 páginasNew General Education Curriculum Focuses on Holistic Learningclaire cabatoAinda não há avaliações

- Tata Securities BranchesDocumento6 páginasTata Securities BranchesrakeyyshAinda não há avaliações

- Revised Y-Axis Beams PDFDocumento28 páginasRevised Y-Axis Beams PDFPetreya UdtatAinda não há avaliações

- Huling El Bimbo Musical Inspired ReactionDocumento3 páginasHuling El Bimbo Musical Inspired ReactionMauriz FrancoAinda não há avaliações

- Regional Diagnostic Assessment Report SY 2022-2023Documento3 páginasRegional Diagnostic Assessment Report SY 2022-2023Dina BacaniAinda não há avaliações

- Mulla Nasiruddin and The TruthDocumento3 páginasMulla Nasiruddin and The TruthewfsdAinda não há avaliações

- BUSINESS ETHICS - Q4 - Mod1 Responsibilities and Accountabilities of EntrepreneursDocumento20 páginasBUSINESS ETHICS - Q4 - Mod1 Responsibilities and Accountabilities of EntrepreneursAvos Nn83% (6)

- Symptomatic-Asymptomatic - MedlinePlus Medical EncyclopediaDocumento4 páginasSymptomatic-Asymptomatic - MedlinePlus Medical EncyclopediaNISAR_786Ainda não há avaliações

- Document 6Documento32 páginasDocument 6Pw LectureAinda não há avaliações

- Dismantling My Career-Alec Soth PDFDocumento21 páginasDismantling My Career-Alec Soth PDFArturo MGAinda não há avaliações

- Wires and Cables: Dobaindustrial@ethionet - EtDocumento2 páginasWires and Cables: Dobaindustrial@ethionet - EtCE CERTIFICATEAinda não há avaliações

- Ecommerce Product: Why People Should Buy Your Product?Documento3 páginasEcommerce Product: Why People Should Buy Your Product?khanh nguyenAinda não há avaliações

- Selected Candidates For The Post of Stenotypist (BS-14), Open Merit QuotaDocumento6 páginasSelected Candidates For The Post of Stenotypist (BS-14), Open Merit Quotaامین ثانیAinda não há avaliações

- 2012 - Chapter 14 - Geberit Appendix Sanitary CatalogueDocumento8 páginas2012 - Chapter 14 - Geberit Appendix Sanitary CatalogueCatalin FrincuAinda não há avaliações

- 2024 Appropriation Bill - UpdatedDocumento15 páginas2024 Appropriation Bill - UpdatedifaloresimeonAinda não há avaliações

- PersonalEditionInstallation6 XDocumento15 páginasPersonalEditionInstallation6 XarulmozhivarmanAinda não há avaliações