Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Vatne Hoem 2007

Enviado por

Anomalie123450 notas0% acharam este documento útil (0 voto)

31 visualizações10 páginasThis paper is a report of a study to develop milieu therapists' acknowledging communication in their relationships with patients. The core concept in acknowledging communication, mutuality, was described as inter-subjective sharing of feelings and beliefs in a respectful way. Participants presented their process of development as a movement from knowing what was best for the patient to appreciating diversity and stubborn talk.

Descrição original:

Direitos autorais

© © All Rights Reserved

Formatos disponíveis

PDF, TXT ou leia online no Scribd

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoThis paper is a report of a study to develop milieu therapists' acknowledging communication in their relationships with patients. The core concept in acknowledging communication, mutuality, was described as inter-subjective sharing of feelings and beliefs in a respectful way. Participants presented their process of development as a movement from knowing what was best for the patient to appreciating diversity and stubborn talk.

Direitos autorais:

© All Rights Reserved

Formatos disponíveis

Baixe no formato PDF, TXT ou leia online no Scribd

0 notas0% acharam este documento útil (0 voto)

31 visualizações10 páginasVatne Hoem 2007

Enviado por

Anomalie12345This paper is a report of a study to develop milieu therapists' acknowledging communication in their relationships with patients. The core concept in acknowledging communication, mutuality, was described as inter-subjective sharing of feelings and beliefs in a respectful way. Participants presented their process of development as a movement from knowing what was best for the patient to appreciating diversity and stubborn talk.

Direitos autorais:

© All Rights Reserved

Formatos disponíveis

Baixe no formato PDF, TXT ou leia online no Scribd

Você está na página 1de 10

Acknowledging communication: a milieu-therapeutic approach in

mental health care

Solfrid Vatne & Elisabeth Hoem

Accepted for publication 1 November 2007

Correspondence to S. Vatne:

e-mail: solfrid.vatne@himolde.no

Solfrid Vatne PhD RN

Associate Professor

Department of Health and Social Science,

Molde University College, Molde, Norway

Elisabeth Hoem RN

Postgraduate student

Department of Adult Psychiatry, Nordmre

and Romsdal Health Trust, Molde, Norway

VATNE S. & HOEM E. ( 2008) VATNE S. & HOEM E. ( 2008) Acknowledging communication: a milieu-

therapeutic approach in mental health care. Journal of Advanced Nursing 61(6),

690698

doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04565.x

Abstract

Title. Acknowledging communication: a milieu-therapeutic approach in mental

health care

Aim. This paper is a report of a study to develop milieu therapists acknowledging

communication in their relationships with patients.

Background. Gundersons therapeutic processes in milieu therapy have come into

use in a broad range of mental health contexts in many countries. Research in

nursing indicates that validation needs a more concrete development for use in

clinical work.

Methods. Schibbyes theory, Intersubjective relational understanding, formed

the theoretical foundation for a participatory action research project in 20042005.

The data comprised the researchers process notes written during participation in

the group of group leaders every second week over a period of 18 months, clinical

narratives presented by participants in the same group, and eight qualitative inter-

views of members of the reection group.

Findings. The core concept in acknowledging communication, mutuality, was

described as inter-subjective sharing of feelings and beliefs in a respectful way.

Participants presented their process of development as a movement from knowing

what was best for the patient (acknowledging patients as competent persons, a

milieu-therapy culture based on conformity), to appreciating diversity and stubborn

talk, to reective wondering questions. Misunderstanding of acknowledgement

occurred, for instance, in the form of always being supportive and afrmative

towards patients.

Conclusion. The concrete approaches in acknowledging communication presented

in this article could be a fruitful basis for educating in and developing milieu

therapy, both for nursing and in a multi-professional approach in clinical practice

and educational institutions. Future research should focus on broader development

of various areas of acknowledging communication in practice, and should also

include patients experiences of such approaches.

Keywords: acknowledging communication, mental health, milieu therapy, nursing,

participatory action research, relational understanding

ORI GI NAL RESEARCH

JAN

690 2007 The Authors. Journal compilation 2007 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Introduction

In the international literature, it seems to be accepted that a

therapeutic milieu is an important phenomenon in mental

health nursing (Peplau 1952, Gunderson 1978, Geanellos

2000). Gundersons (1978) ve therapeutic processes

structure, containment, support, involvement and validation

have become commonly used in many countries and in a

broad range of clinical contexts, independent of size, patients

length of stay, stafng and philosophy (Lawson 1998,

Thomas et al. 2002, Norton & Bloom 2004, Thorgaard &

Haga 2006). However, there appears to be little published

research evaluating the impact of these approaches in this

area of practice (Geanellos 2000). Some studies conrm that

containment and structure are practised in nursing; this is

also the case, to some extent, with support and involvement

(Thomas et al. 2002). The myth of a positive effect of

structure seems to have dominated the discussion, placing

emphasis on the physical milieu and rules for interaction

between patients and therapist and between therapists

(Norton & Bloom 2004, Vatne & Fagermoen 2007). The

fth process, validation, appears to need a more concrete

development for use in the clinical area (Thomas et al. 2002,

Vatne & Fagermoen 2007). Validation, as described by

Gunderson, is the afrmation of and respect for a patients

individuality through interaction with staff.

The purpose of the work presented in this paper was to

give more substance to the concept of validation in clinical

work. Schibbyes (2002) theory of intersubjective relational

understanding was the theoretical foundation for the

study.

Theoretical framework

Therapeutic relationship in challenging encounters

The reason for the strong emphasis on a therapeutic

relationship in milieu therapy is that the patients often have

relational traumas that make it difcult for them to form

positive relationships with other people (Peplau 1952).

Trauma-related symptoms can be understood as manifesta-

tions of the anxious, avoidant, aggressive and disorganized

feelings, often expressed by disruptive behaviour that chal-

lenges interaction in daily relationships with other people

(Lawson 1998).

A search in CINAHL, PsycInfo and MEDLINE, using the

keywords difcult and manipulative behaviour combined

with mental health care yielded a large number of studies.

They generally showed that patients characterized as chal-

lenging are those who do not stay within traditional

boundaries in society (Hepworth 1993, Breeze & Repper

1998, Lowry 1998, Bowers 2003a,b, Hayward et al. 2005).

Often they were described by the staff as non-compliant,

manipulatingsplitting, cantankerous, attention getting

and so on. Patients with aggressive, acting out and self-

harming behaviour belonged to the same category (Vatne &

Fagermoen 2007). They challenged professionals feelings,

for example, of powerlessness, shame, fear and anger. They

were also experienced as a threat to nurses competence and

feelings of control (Breeze & Repper 1998).

Use of milieu therapy is suggested to meet the treatment

needs of people who are recovering from traumatic experi-

ences by offering opportunities to develop more constructive

thoughts and behaviour in managing their distress and

vulnerability (Norton & Bloom 2004). However, we found

little concrete evidence in the research literature that might

help guide milieu therapists during challenging encounters

while also meeting the therapeutic need of traumatized

patients. The interventions suggested were rm limit-setting

and non-judicial approaches (Hepworth 1993, Breeze &

Repper 1998, Mason 2000, Laskowski 2001, Bowers

2003a,b), which often are contradictory demands (Vatne &

Holmes 2006, Vatne & Fagermoen 2007).

Psychotherapy research over the past decades has identied

the therapist-client relationship, especially therapeutic

alliance as of the greatest importance, along with thera-

peutic techniques. There is evidence for the positive benets

of conditions such as giving support, attention to patients

experiences, reection and exploration and facilitation of

affects (Roth & Fonagy 2005). Basing their claim on reviews

of controlled studies, Asay and Lambert (1999) propose that

so- called common factors have the clearest implications for

psychotherapeutic practice, i.e. equality, acceptance, empa-

thy, warmth and understanding, perceived trustworthiness,

condence and investment in the relationship. Therapists

perceived to be rigid, uncertain, critical and uninvolved are

more likely to be valued as less effective therapists (Roth &

Fonagy 2005). It is reasonable to assume that such common

factors also are a fundamental premise of milieu therapy. In a

qualitative interview study with patients support was

reported for a good and helping relationship characterized

by treating the patient as a valued person, displaying warmth

and empathy, and carrying on normal conversations that

enable the patient to have some meaningful control over the

situation (Breeze & Repper 1998). According to Gunderson

(1978), validation has to be carried out through respect for

patients individuality and acceptance of their symptoms as

meaningful expressions; for example, hallucination may be

understood as an expression of some unclear but important

aspects of the patients self. We suggest that common factors

JAN: ORIGINAL RESEARCH Acknowledging communication

2007 The Authors. Journal compilation 2007 Blackwell Publishing Ltd 691

and Gundersons concept of validation can be combined

through the theory of acknowledging communication.

Acknowledging communication

Although the importance of being acknowledged is recog-

nized as a contributing factor in helping people who suffer

from mental illness (Stern 1985, Schibbye 2002), acknowl-

edging communication is a concept not previously used in the

international mental health literature. Communication that

focuses on acknowledgement comprises an attitude, but also

concrete approaches that emphasize the subjective, experien-

tial aspect of what is shared by staff and patients during

communication. Inter-subjectivity is the sharing of common

experiences, for example being open to the subjective

opinions or feelings of someone else. When patients experi-

ence that their feelings are being regarded as important and

valid, they may also experience that they become subjects in

their own lives. By being acknowledged as thinking and

feeling individuals, they can regain their ability to engage in

self-reection and self-delimitation (Schibbye 2002). To-

gether, those theoretical concepts draw on concrete strategies

which could provide an important supplement to Gunder-

sons concept of validation.

Self-delimitation and self-reection

Schibbye (2002) describes self-delimitation as the ability to

sort out and distinguish between ones own opinions,

feelings, values and assessments and those of others; this

ability is fundamental in acknowledging oneself and others.

It is concerns maintaining boundaries when engaging in

dialogue with others (Schibbye 2002, p. 78). She describes

self-reection as a specic human quality whereby one is

able to relate to oneself by observing oneself from an

outside position. Self-reection is our ability to have

thoughts about our thoughts and to be aware of our

feelings, i.e. the fact that we can have a relationship with or

access to processes within our selves (Schibbye 2002, p. 77)

concurs with how Gunderson (1978) describes the concept

of introspection.

In a clinical context, self-delimitation requires that both

therapist and patient develop clear boundaries in the treat-

ment relationship; the therapist does not control the patient.

Engaging in reective processes means to wonder together

about what is happening in concrete situations. In turn,

wondering questions can be helpful in increasing self-reec-

tivity. Additionally, it involves emotional empathy by being

emotionally present, i.e. tuning in on the other persons

feelings.

The study

Aim

The aim of the study was to develop milieu therapists

acknowledging communication in their relationships with

patients. The following research question was asked: What

changes occurred in the milieu therapists clinical work

during participating in the process of developing acknowl-

edging communication?

Design

The project presented was an empirical study carried out at

the Nordmre and Romsdal Health Trust, Norway, a

medium-sized public Norwegian psychiatric hospital. The

rationale for this project was to offer patients a better process

of self-development by building staffs ability to behave in

more acknowledging ways.

The project was based on a participatory action research

design founded in critical theory (Holter & Schwartz-Barcott

1993, Hart & Bond 1996, Polit & Beck 2004), and the

assumption that development of practical knowledge in a

professional community calls for an inquiry that fosters

enlightened self-knowledge which involves self-reection in

dialogues (Polit & Beck 2004).

The setting

The study unit, which has a total of 17 young patients, is

divided into two wards with approximately 50 staff

members. The unit provides treatment for young people

between the ages of 16 and 30 who suffer from various

mental disorders: some have self-control problems, often

related to trauma and abuse, and some have developed

symptoms that are consistent with a diagnosis of schizo-

phrenia. The length of stay varies from 6 to 30 months.

The staff varies in professional background (psychiatrists,

psychologists, nurses, mental health nurse specialists, social

workers, occupational therapists, nursing assistants) and

age (2565 years).

Methods

The researcher in this study interacted in reection arenas

with the study participants. The reection was based on

analyses of taken-for-granted assumptions in concrete clinical

narratives from the unit presented by the staff, and transla-

tion of the theories of acknowledging communication into

concrete actions related to those narratives.

S. Vatne and E. Hoem

692 2007 The Authors. Journal compilation 2007 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Staff in the unit (about 50) were divided into a total of

eight multi-disciplinary groups, named reection groups,

with two of the staff as group leaders. Additionally, the two

group leaders in each reection group participated in a

leader support group 16 group leaders in total. This group

was led by an internal experienced professional and an

external researcher (the rst author). A total of 27 meetings,

15 hours each, were held in the reection groups and the

group leaders group; the meetings were held every second

week over a period of 18 months. Reection also took part at

project seminars (eight in total), in which the theory of

acknowledging communication was presented and discussed.

Data collection methods in action research can vary, but

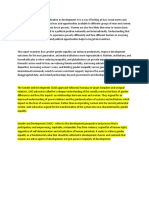

follow the action taking place. Figure 1 gives an overview of

the data collection methods related to the different arenas of

reection, and shows that data were collected in form of

researchers (rst authors) process notes (reections and

narratives) written during participation in the leader support

group and project seminars. Because of transfer of informa-

tion by the leaders between the reection and leader support

groups, this became a main data source. In the leader support

group, data were collected over an 18-month period in 2004

2005. Using qualitative interviews (lasting 2 hours each),

data about experiences of participating in various arenas and

the whole project were collected (tape-recorded and tran-

scribed verbatim). A strategic sample comprising eight

members, one from each reection group, was recruited to

take part in the interviews. To achieve broadness and

variation in the data, participants with different professional

backgrounds and length of experience were selected. The

interviews were carried out after the conclusion of the project

(JanuaryFebruary 2006), by a researcher who had not taken

part in the group reections but was familiar with the

projects theoretical foundation. They were based on a semi-

structured interview guide that dealt with staff members

experiences of the action process, opinions about the essence

of an acknowledging approach, and possible changes in

themselves and in the unit during the process.

Ethical considerations

The project was approved by the Norwegian Regional

Committee for Medical Research Ethics and the Norwegian

Data Inspectorate. Participants were each given information

sheets about the study, were informed that they could

withdraw from the study at any time without explanation,

and were reassured that their contributions in groups and in-

depth interviews would be treated condentially.

Data analysis

The interviews were analysed using Kvales (1996) theory on

qualitative thematic content analysis. Each case was carefully

analysed and interpreted by both authors to identify units of

meaning. The method involved systematic structuring,

detailed analysis and coding of the text data from all

interviews by creating themes and subthemes that reected

the essential meaning in the text, and reecting distinctions

Project seminars (8)

All participants

Documents in researchers process note

8 Reflection groups, 16 meetings

6-8 participants, 2 group leaders

Interviews

8 Informants

1 from each

reflection group

Leader support group

2 group leaders form each reflection group

Researchers and supervisors

Researchers process notes

Narratives

Figure 1 Data-collection methods (in bold)

related to reection arenas.

JAN: ORIGINAL RESEARCH Acknowledging communication

2007 The Authors. Journal compilation 2007 Blackwell Publishing Ltd 693

and contradictions inherent in the data. In a nal analysis,

data from all participants were analysed together and in

conjunction with the researchers process notes and narra-

tives from the group of group-leaders. Through this process,

an inclusive and reduced text was created to facilitate further

theoretical analysis related to the theory of acknowledging

communication.

Rigour

In action research, rigour is related to use of learning cycles

and focus is placed on factors that are signicant and useful

for the organization (Coghlan & Brannick 2005). This

studys specic strength was the assembling and analysing

of data from different reection and teaching arenas over a

relatively long period (15 years). This made it possible to

include interviews of participants from the reection groups

together with the researchers process notes from the leader

support group so that experiences and knowledge developed

in both arenas of reection were represented. The reliability

of the study was ensured by tape recordings the interviews

and by the research journal containing systematic notes taken

during the leader support groups.

Findings

Participants

The eight participants in the interviews represented different

professional backgrounds: four mental health nurse special-

ists, two whom were leaders of the unit; two occupational

therapists; two nursing assistants. The interviewees ranged in

age from 35 to 55 years. The members of the group of group

leaders (16) were mental health nurse specialists (7), nursing

assistants (2), occupational therapists (2), psychiatrists (2)

and psychologists (2), physiotherapist (1). They ranged in age

from 35 to 60.

Three major themes emerged from the data: core condi-

tions for acknowledging communication, the process of

change in staff practice, and misunderstanding of acknowl-

edgement in practice.

Core conditions for acknowledging communication

Known but still unknown

Theoretically, the participants were familiar with the basic

philosophy of acknowledgment. Mental health nurse spe-

cialists described acknowledgement as a basic attitude in their

professional education, e.g. to acknowledge the patient as a

valuable person. However, it was not an philosophy that was

consciously settled in the units everyday practice. How to

practise acknowledgement was an unknown area of compe-

tence. All participants said that they found the theory difcult

to put into practice in their actual encounters with patients.

One said, It feels like my tongue gets tied. Before exploring

more thoroughly the ndings, these are rst illustrated with

an abridged narrative. The story was discussed rst in the

reection group and then in the leader support group.

A story about and not about acknowledging

communication

Lisa, a 19-year-old, is on leave of absence during a discharge

process from the ward where she has been an inpatient the

last 2 years; she is living in her own apartment in the com-

munity, attending high school. Her main care professional

network in the community is a local medical practitioner and

a mental health community nurse.

This story starts when Lisa makes contact with the

community mental health nurse because she feels an urge to

cut herself. To verbalize her feelings instead of cutting herself

is a strategy learned in the ward. The nurse immediately calls

the medical practitioner. Together they decide to send Lisa to

the hospital in an ambulance, in spite of the fact that Lisa tells

them that she wants to stay at home.

Arriving at the ward, staff asks Lisa why she is returning

and what the problem is. Lisa whispers that she wants to go

home and withdraws to her room. When staff members

speak to her, she remains silent. Since they nd it difcult to

get her version of the situation, they are not happy about

letting her go. Lisas former primary nurse, having a good

relationship with Lisa, knocks on her door and waits for an

answer; but Lisa is still silent. She knocks once more, at

the same time saying that she is entering the room. Lisa is in

the bed covered by the sheets. The nurse asks if it is OK if

she sits on her bed, and Lisa nods. Both keep silent, but

after a while Lisa rises to a sitting position. The nurse gives

Lisa a slight hug while she says that she thinks it must have

been awful and dramatic for Lisa to be transported in an

ambulance. Lisa nods. The nurse continues by saying that

she feels it is difcult to know what to believe about Lisas

opinions, since she says that she wants to go home but non-

verbal signals say, Leave me alone. She therefore asks Lisa

to help her, because she thinks that Lisa must be the one

who knows what her need is at this time.

The nurse then suggests taking a walk. During the walk

Lisas voice is clear and her posture is straight. She speaks

plainly about her admission, which she felt was unnecessary,

and how the transport in the ambulance was horrifying. She

wants to go home and be with her friend. The same afternoon

she goes home alone by bus.

S. Vatne and E. Hoem

694 2007 The Authors. Journal compilation 2007 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

In the rst part of the story, the professionals in the

community acted based on their own point of view. Later,

the story illustrates how a nurse takes the patients perspec-

tive and makes it visible to the patient by sharing her feelings

about the situation. Study participants named such an

approach creating a mutual relationship.

Mutuality: a core theme in acknowledging patients

The participants presented mutuality as the essence in

acknowledging communication; they described it as an inter-

subjective sharing of good and bad feelings and beliefs in a

respectful way. Through mutuality, both patients and pro-

fessionals were allowed to appear as distinct persons. In

various fashions they stated inter-subjectivity to be an

important aspect of a therapeutic relationship:

Trying to understand the stories patients tell us, and their

subjective reality, is necessary to attain a therapeutic change.

In a collaborating relationship I have to respect the

patients point of view.

It is about sharing good and bad experiences.

The participants thought this manner of mutual sharing

could make a change in both parties of the relationship.

The process of change in staff

From knowing best to acknowledging patients as competent

Participants explained that one consequence of respecting

patients subjective points of view were that therapists have

to take the patients expressions seriously and to accept and

dare to show diversity in behaviour and opinions among

patients and colleagues. For the participants this change in-

volved a role-shift away from what they called a traditional

role of a professional expert, i.e. the role in which the pro-

fessional always knows what is best for the patients like

the professionals in the start of the story of Lisa. The expert

role was described as involving behaviour like stubborn talk

and assertive manners, for example dening the patients by

ascribing negative attributes to them, and performing a role

of disciplining the patients. If staff relate deviation only to

the persons negative qualities, this is a diagnostic approach

(Lchen 1971, Vatne & Holmes 2006) which can prevent

staff from understanding the situation and their own contri-

bution to it, for example the way they interact (Breeze &

Repper 1998, Vatne & Fagermoen 2007). According to

Schibbye (2002), disciplinary interactions can easily occur

during clinical activities and are characterized by therapists

dening patients behaviour, problems, experiences and

solutions. Often such attitudes can contribute to deadlock in

the treatment relationship. When staff nd themselves in

challenging encounters, it is recommended that they try to

view the situation from the patients perspectives (Wright

1999) and examine their own behaviours and responses

(Harris & Morison 1995). Our participants described such a

change in their perspective and actions during the project, but

the new approaches were yet not totally integrated, either in

themselves or in the practice of the unit: Such dramatic

changes in communicating with the patients takes time.

According to participants, respecting the patients view

implied that they had to undress from a distanced profes-

sional role, and stand out as independent persons having

their own opinions about patients and treatment. It also

involved reecting about the language used and speaking to

them in a way that opens up, giving the patients a possibility

to reect upon themselves, and their relationships with

others.

From a culture of conformity to appreciating diversity

To show diversity was perceived by participants as a big

step from the units former philosophy to act identical and

conform, in accordance with the units informal rules. By

practising self-disclosure, the professionals were allowed to

develop a closer relationship to the patient, being a profes-

sional acting self-delimitated through self-reection, and

more like a friend. The statement about being both a pro-

fessional and a friend is worth examining. For example, in a

study by Hem and Heggen (2003), nurses described being

professional and being human as contradictory demands

that produced difcult role conicts.

Self-delimitation and self-reection in practice

Our participants talked about self-delimitation and self-

reection as concepts that had to be translated into concrete

actions in clinical encounters. They described self-delimita-

tion as consciousness about their own thoughts and feel-

ings, and regarded their previous lack of consciousness as

being a possible background for serious conict with pa-

tients. In order to behave differently, they felt it was

important to distinguish verbally between the therapists

and patients experiences of the situation. To behave in a

self-delimited way assumed that they practised self-reec-

tion, explained in terms such as reecting about our own

feelings in the concrete situation and what we think might

be the individual patients feelings. Practising self-reection

in groups through discussion and role-playing clinical situ-

ations became the arena for developing ways of verbalizing

self-reection and self-delimitation. When practising self-

reection, one participant said that he came to see himself

from another perspective. Others reported that they found

it important to investigate experiences together with the

patients.

JAN: ORIGINAL RESEARCH Acknowledging communication

2007 The Authors. Journal compilation 2007 Blackwell Publishing Ltd 695

When we reected on the researchers narrative in the

group and role-played the interaction, she suddenly saw

herself in a new light and realized that it was her own shame

she had placed upon the patient. This shows that it is

important for nurses to look into their selves and we are not

used to doing this. It is important to investigate our

experiences and beliefs with patients and to ask them about

their feelings and thoughts because our interpretations of

what is happening inside patients from an outside position

can be wrong.

Similar to our ndings, other researchers have demon-

strated that critical reection through dialogues, combined

with narratives helped to transform nursing practice by

bridging the gap between theoretical ideals and the realities of

daily care-giving practice (Kim 1999, Forneris & Peden-

McAlpine 2007).

According to Gunderson (1978), staff working with

validation should be able to combine introspection with

involvement with patients (Gunderson 1978, p 331).

Validation depends on professionals empathic skills and

sensitivity, and also on the ability to tolerate uncertainty.

Looking at the narrative about Lisa, it is obvious that the

nurse is practising empathic skills and emotional presence

when she verbalizes the dramatic feeling for Lisa caused by

being transported in an ambulance. The nurse shows self-

delimitation when she verbalizes what she sees from her

own position, saying that it is difcult to know what to

believe about Lisas experiences from what Lisa expresses

verbally and non-verbally. When she asks Lisa about help,

she is acknowledging Lisa as a competent person who

knows what is best for her. Additionally, she shows her

own limitations of understanding, which is self-delimita-

tion. When she claries her uncertainty she demonstrates

self-reection and disclosure of her own feelings. Partici-

pants proposed these processes as possible and important

actions in their daily work: When I reect, I help the

patients to reect about themselves, then the patients can

be more distinct for themselves.

Norton and Bloom (2004) also describe the main form of

validation to be validating clients negative experiences and

providing a framework to start viewing themselves as parties

who can participate actively in recovering, rather than as

sick, bad or disruptive individuals. Validation supports

individuality and differentiation of self, characterized by the

ability to separate thinking and feeling. By sharing feelings

with patients in a self-reective and self-delimitating manner,

our participants described their behaviour as professional,

with a closer relationship to the patient and sometimes also

becoming a friend. MacGillivary and Nelson (1998) found

that mutual trust and respect, sustained by self-disclosure,

friendships and relationships, emerged strongly as a core

value of partnership, which seems to be a more professional

concept than friendship.

From authoritarian talk to wondering reective questions

Our participants explained their changes in communication

with patients as a shift from authoritarian messages to using

wondering reective questions, based on emotional listening

to patients expressions, as was demonstrated by Lisas nurse.

It also involved a change in approach from walking ahead of

the patient, trying to drag him from behind, to pushing to-

gether in collaboration. In contrast, they pointed out that

their previous focus was on reality of facts, and motivating

patients to change opinions and behaviour in accordance

with the professionals view. Often such advice from staff

could end in closing up the talk. When shifting to

acknowledging approaches, participants described their work

as more meaningful but also as more difcult and uncertain:

It is tough to put focus on our self and strenuous to be

conscious of oneself all the time.

Misunderstanding of acknowledgement in practice

Some participants claimed that misunderstood acknowledge-

ment could take place in practice; for example, It is easy to

think that you always have to agree with the patients. An

example of misunderstood acknowledgement is illustrated

below.

A story about misunderstood acknowledgment

Martin, a 26-year-old inpatient, has symptoms consistent

with schizophrenia. On his own initiative he has acted to

arrange for a rafting tour combined with a weekend slee-

pover. It is also known that Martin is extremely careful with

his money. One afternoon he tells one of the nurses that he

does not want to participate, because the cost of the tour is 50

dollars. The following conversation takes place:

Nurse: Why dont you want to participate, Martin?

Martin: It is too expensive.

Nurse: But what do you want to spend your money on then?

Martin: I want to save money to buy furniture and appliances for my

new apartment. I have thought a lot about it the past few days, and it

has been a big problem to make a decision.

Nurse: I understand - you take very good care of your money. You

are the one to decide what to do, not me.

Martin decided not to participate on the rafting trip, but when he

walked away he did not look very happy. The nurse said that she felt

disappointed about the outcome of the talk and that the situation

ended puzzled.

S. Vatne and E. Hoem

696 2007 The Authors. Journal compilation 2007 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

The story illustrates that a process of shifting perspective

from being authoritarian and rule-governed can move in the

opposite direction, to thinking that one has to be kind and

supportive to everything the patient says. The consequence of

such a passive approach could be that the professionals

become vague and indistinct. In the story, the nurse gives no

correctives that can help the patient to appear as a distinctive

person for himself. The following solutions to this problem

were introduced in the leader support group: If the nurse,

instead of letting Martin take the decision, says, It seems to

me that you want me to agree with you, she can possibly

match the feeling Martin has by getting the nurse to take his

side. The nurse can also reect the conict she thinks Martin

experiences by saying, I am really surprised; I thought you

wanted to participate. The nurse can also continue: Now, I

am a little uncertain. How do you think we can nd a

solution? The last sentence opens up the possibility for

Martin to suggest a solution that he probably already has in

his mind.

From the discussion of the story, a difference between

afrmation and acknowledging, which is not clear in Gun-

dersons conceptualization, became visible: afrmation of

patients can take place, without acknowledging, when the

mutual sharing of distinct opinions is not done. Afrmation

itself can, according to Schibbye (2002), be one-sided when a

professional afrms the patient in accordance with what they

think the patient needs. In contrast, respectful sharing of

opinions contributes to challenging the patients point of

view, which is important in therapy (Peplau 1952).

Study limitations

As the data have been drawn from only one study site, the

study has limited transferability. It is also a weakness that no

data on patients experiences of changes in collaboration with

the staff were collected. Patients were invited to participate in

interviews but they declined.

It is a challenge for leaders in mental health care to arrange

for processes which foster awareness of the therapeutic

outcomes of nursepatient relationships and which build a

caring culture of acknowledgment. Our experiences are that

the many education programmes do not involve students in

concrete training in therapeutic communication. We believe

that the concrete approaches to acknowledging communica-

tion and reection presented in this paper can be a fruitful basis

for educating staff in and developing milieu therapy both for

nursing and in a multi-professional approach in clinical

practice and educational institutions. Future research should

focus on more in-depth and broader development of various

areas of acknowledging communication in practice, and

should also include patients experiences of such approaches.

Author contributions

SV and EH were responsible for the study conception and

design and SV was responsible for the drafting of the

manuscript. EH performed the data collection and SV and

EH performed the data analysis. EH obtained funding and

provided administrative support. EH made critical revisions

to the paper.

References

Asay T.P. & Lambert M.J. (1999) The empirical case for the common

factors in therapy. Quantitative findings. In The Heart & Soul of

Change. What Works in Therapy (Hubble M.A., Duncan B.L. &

Miller S.D., eds), American Psychological Association, Washington,

DC, pp. 3335.

Bowers L. (2003a) Manipulation: description, identification and

ambiguity. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing 10,

323328.

Bowers L. (2003b) Manipulation: searching for an understanding.

Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing 10, 329334.

Breeze J. & Repper J. (1998) Struggeling for control: The care

experiences of difficult patients in mental health services. Journal

of Advanced Nursing 28(6), 301311.

What is already known about this topic

Acknowledging patients is an ideal in mental health

nursing that needs concrete development for use in

clinical work.

Mutuality, through inter-subjective sharing of feelings

and beliefs, is an important aspect of therapeutic

relationships.

Being professional and being human are contradictory

demands, producing difcult role conicts in nursing

practice.

What this paper adds

Acknowledging patients involves a shift from

authoritarian messages to using wondering, reective

questions based on emotional listening.

Self-disclosure through self-reection and self-delimi-

tation allows professionals to develop closer relation-

ships with patients, being more like a friend.

Afrmation can take place without acknowledgement

when professionals afrm patients in accordance with

what they think the patients need.

JAN: ORIGINAL RESEARCH Acknowledging communication

2007 The Authors. Journal compilation 2007 Blackwell Publishing Ltd 697

Coghlan D. & Brannick T. (2005) Doing Action Research in Your

Own Organization. Sage Publication Ltd., London.

Forneris S.G. & Peden-McAlpine C. (2007) Evaluation of a reflective

learning intervention to improve critical thinking in novice nurses.

Journal of Advanced Nursing 57(4), 410421.

Geanellos R. (2000) The milieu and milieu therapy in adolescent

mental health nursing. The International Journal of Psychiatric

Nursing Research 5(3), 638648.

Gunderson J.G. (1978) Defining the therapeutic processes in psy-

chiatric milieu. Psychiatry 41, 327335.

Harris D. & Morrison F. (1995) Managing violence without coer-

cion. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing 9(4), 203210.

Hart E. & Bond M. (1996) Making sense of action research

through the use of a typology. Journal of Advanced Nursing 23,

152159.

Hayward P., Tilley F., Derbyshire C., Kuipers E. & Grey S. (2005)

The ailment revisited: Are manipulative patients really the most

difficult? Journal of Mental Health 14(3), 291303.

Hem M.H. & Heggen K. (2003) Rejection - a neglected phenomenon

in psychiatric nursing. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health

Nursing 11, 5563.

Hepworth D. (1993) Managing manipulative behavior in the helping

relationship. Social Work 38, 674682.

Holter I.M. & Schwartz-Barcott D. (1993) Action research: what is

it? How has it been used and how can it be used in nursing?

Journal of Advanced Nursing 18, 298304.

Kim H.S. (1999) Critical reflective inquiry for knowledge develop-

ment in nursing practice. Journal of Advanced Nursing 29(5),

12051212.

Kvale S. (1996) Interviews: An Introduction to Qualitative Research

Interviewing. SAGE Publications, London.

Laskowski C. (2001) The mental health clinical nurse specialist and

the difficult patient: evolving meaning. Issues in Mental Health

Nursing 22, 522.

Lawson L. (1998) Milieu management of traumatized youngster.

Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing 11(3), 99

106.

Lchen Y. (1971) Idealer og realiteter i et psykiatrisk sykehus: En

sosiologisk fortolkning. Universitetsforlaget, Oslo.

Lowry D. (1998) Issues of non-compliance in mental health. Journal

of Advanced Nursing 17, 12261232.

MacGillivary M.A. & Nelson G. (1998) Partnership in mental

health: what is it and how to do it. Canadian Journal of Rehabil-

itation 12(2), 7183.

Mason T. (2000) Managing protest behaviour: from coercion to

compassion. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing 7,

269275.

Norton K. & Bloom S.L. (2004) The art and challenge of long-term

and short-term therapeutic communities. Psychiatric Quarterly

75(3), 249261.

Peplau H. (1952) Interpersonal Relations in Nursing. Putnam, New

York.

Polit D.F. & Beck C.T. (2004) Nursing Research. Principles and

Methods. Lippingcott, Williams and Wilkens, Philadelphia.

Roth A. & Fonagy P. (2005) What Works for Whom?: A Critical

Review of Psychotherapy Research, 2nd edn. The Guilford Press,

New York.

Schibbye A.L.L. (2002) A Dialectic Understanding of Relations in

Psychotherapy with Individuals, Couples and Families. University

Press, Oslo.

Stern D. (1985) The Interpersonal World of the Infant. Basic Books,

New York.

Thomas S.P., Shatell M. & Martin T. (2002) Whats therapeutic

about the therapeutic milieu? Archives of Psychiatric Nursing

16(3), 99107.

Thorgaard L. & Haga E. (2006) Relationsbehandlere i psykiatrien.

Gode relationsbehandlere og god miljterapi. Bind I Stiftelsen

Psykiatrisk Opplysning. Hertervig Forlag, Stavanger.

Vatne S. & Fagermoen M.S. (2007) To correct and to acknowledge:

two simultaneous and conflicting perspectives of limit-setting in

mental health nursing. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental health

Nursing 14, 4148.

Vatne S. & Holmes C. (2006) Limit setting in mental health: his-

torical factors and suggestions as to its rationale. Journal of Psy-

chiatric and Mental Health Nursing 13, 588597.

Wright S. (1999) Physical restraints in the management of violence

and aggression in in-patients settings: a review of issues. Journal of

Mental Health 8(5), 459472.

S. Vatne and E. Hoem

698 2007 The Authors. Journal compilation 2007 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Você também pode gostar

- Health Design Thinking An Innovative Approach in PDocumento6 páginasHealth Design Thinking An Innovative Approach in PElena AlnaderAinda não há avaliações

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5794)

- Long Test in DIASSDocumento2 páginasLong Test in DIASSRonalyn Cajudo100% (2)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (895)

- Final Assessment PaperDocumento11 páginasFinal Assessment PaperKevlyn HolmesAinda não há avaliações

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- Jamila Chapter 2 and 3 With CorrectionsDocumento18 páginasJamila Chapter 2 and 3 With CorrectionsFAGAS FoundationAinda não há avaliações

- GE 1 (Activities) Understanding SelfDocumento28 páginasGE 1 (Activities) Understanding Selfbethojim0% (1)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (400)

- 05b6-1714:documents (1) /gender Development (Reflection)Documento3 páginas05b6-1714:documents (1) /gender Development (Reflection)Queenie Carale0% (1)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- Elder Sharmaine 15166272 Ede101 Assessment2Documento10 páginasElder Sharmaine 15166272 Ede101 Assessment2api-240004103Ainda não há avaliações

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- Project Management CapstoneDocumento251 páginasProject Management CapstoneDSunte WilsonAinda não há avaliações

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2259)

- Tiếng anh 6 Friends Plus - Unit 4 - Test 2Documento4 páginasTiếng anh 6 Friends Plus - Unit 4 - Test 2dattuyetnhimsocAinda não há avaliações

- IPBT Introductory SessionDocumento57 páginasIPBT Introductory SessionZaldy TabugocaAinda não há avaliações

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- NURS FPX 6011 Assessment 1 Evidence-Based Patient-Centered Concept MapDocumento4 páginasNURS FPX 6011 Assessment 1 Evidence-Based Patient-Centered Concept MapCarolyn HarkerAinda não há avaliações

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- Solutionbank C1: Edexcel Modular Mathematics For AS and A-LevelDocumento62 páginasSolutionbank C1: Edexcel Modular Mathematics For AS and A-LevelMomina ZidanAinda não há avaliações

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- Universidad de Sta Isabel Pili CampusDocumento7 páginasUniversidad de Sta Isabel Pili CampusGlenn VergaraAinda não há avaliações

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (266)

- Lesson 4 - Developing The Non-Dominant HandDocumento6 páginasLesson 4 - Developing The Non-Dominant HandBlaja AroraArwen AlexisAinda não há avaliações

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (345)

- Miss Bhagyashri Patil SIP ReportDocumento71 páginasMiss Bhagyashri Patil SIP ReportDr. Sanket CharkhaAinda não há avaliações

- Psycolinguistic - Ahmad Nur Yazid (14202241058)Documento3 páginasPsycolinguistic - Ahmad Nur Yazid (14202241058)Galih Rizal BasroniAinda não há avaliações

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- Program Evaluation RubricDocumento13 páginasProgram Evaluation RubricShea HurstAinda não há avaliações

- The Five Models of Organizational Behavior: - Autocratic - Custodial - Supportive - Collegial - SystemDocumento6 páginasThe Five Models of Organizational Behavior: - Autocratic - Custodial - Supportive - Collegial - SystemWilexis Bauu100% (1)

- 2012 Introducing Health and Well-BeingDocumento24 páginas2012 Introducing Health and Well-BeingvosoAinda não há avaliações

- Proverbs 1: Prov, Christ's Death in TheDocumento24 páginasProverbs 1: Prov, Christ's Death in TheO Canal da Graça de Deus - Zé & SandraAinda não há avaliações

- Articles Training GuideDocumento156 páginasArticles Training GuidescribdgiridarAinda não há avaliações

- AAA Test RequirementsDocumento3 páginasAAA Test RequirementsjnthurgoodAinda não há avaliações

- Department of Civil Engineering College of Engineering University of SulaimaniDocumento233 páginasDepartment of Civil Engineering College of Engineering University of SulaimaniAhmad PshtiwanAinda não há avaliações

- Poptropica English AmE TB Level 3Documento227 páginasPoptropica English AmE TB Level 3Anita Magaly Anita100% (1)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- Objectively Summarize The Most Important Aspects of The StudyDocumento2 páginasObjectively Summarize The Most Important Aspects of The StudyNasiaZantiAinda não há avaliações

- Why Should White Guys Have All The Fun? Reginald F. Lewis, African American EntrepreneurDocumento25 páginasWhy Should White Guys Have All The Fun? Reginald F. Lewis, African American EntrepreneurJim67% (3)

- Ethics Report GRP 3Documento3 páginasEthics Report GRP 3MikaAinda não há avaliações

- Dental Anxiety - FullDocumento14 páginasDental Anxiety - FullTJPRC PublicationsAinda não há avaliações

- Unit 3 - Professional Practice PDFDocumento8 páginasUnit 3 - Professional Practice PDFMaheema RajapakseAinda não há avaliações

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (121)

- Numl Lahore Campus Break Up of Fee (From 1St To 8Th Semester) Spring-Fall 2016Documento1 páginaNuml Lahore Campus Break Up of Fee (From 1St To 8Th Semester) Spring-Fall 2016sajeeAinda não há avaliações