Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Paper ITG

Enviado por

SergyLukrasovtDireitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Paper ITG

Enviado por

SergyLukrasovtDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

http://www.cepis.

org

CEPIS, Council of European Professional Informatics

Societies, is a non-profit organisation seeking to improve and

promote high standards among informatics professionals in

recognition of the impact that informatics has on

employment, business and society.

CEPIS unites 37 professional informatics societies over

33 European countries, representing more than 400,000

ICT professionals.

CEPIS promotes

http://www.eucip.com http://www.ecdl.com

http://www.upgrade-cepis.org

* This monograph will be also published in Spanish (full version printed; summary, abstracts, and some

articles online) by Novtica, journal of the Spanish CEPIS society ATI (Asociacin de Tcnicos de

Informtica) at <http://www.ati.es/novatica/>.

UPGRADE is the European J ournal for the

Informatics Professional, published bimonthly

at <http://www.upgrade-cepis.org/>

Publisher

UPGRADE is published on behalf of CEPIS (Council of European

Professional Informatics Societies, <http://www.cepis.org/>) by

Novtica <http://www.ati.es/novatica/>, journal of the Spanish

CEPIS society ATI (Asociacin de Tcnicos de Informtica, <http://

www.ati.es/>)

UPGRADE monographs are also published in Spanish (full version

printed; summary, abstracts and some articles online) by Novtica

UPGRADE was created in October 2000 by CEPIS and was first

published by Novtica and INFORMATIK/INFORMATIQUE, bi-

monthly journal of SVI/FSI (Swiss Federation of Professional

Informatics Societies, <http://www.svifsi.ch/>)

UPGRADE is the anchor point for UPENET (UPGRADE European

NETwork), the network of CEPIS member societies publications,

that currently includes the following ones:

Informatik-Spektrum, journal published by Springer Verlag on

behalf of the CEPIS societies GI, Germany, and SI, Switzerland

ITNOW, magazine published by Oxford University Press on behalf

of the British CEPIS society BCS

Mondo Digitale, digital journal fromthe Italian CEPIS society AICA

Novtica, journal from the Spanish CEPIS society ATI

OCG Journal, journal from the Austrian CEPIS society OCG

Pliroforiki, journal from the Cyprus CEPIS society CCS

Pro Dialog, journal from the Polish CEPIS society PTI-PIPS

Editorial Team

Chief Editor: Lloren Pags-Casas, Spain, <pages@ati.es>

Associate Editor: Rafael Fernndez-Calvo, Spain, <rfcalvo@ati.es>

Editorial Board

Prof. Wolffried Stucky, CEPIS Former President

Prof. Nello Scarabottolo, CEPIS Vice President

Fernando Piera Gmez and Lloren Pags-Casas, ATI (Spain)

Franois Louis Nicolet, SI (Switzerland)

Roberto Carniel, ALSI Tecnoteca (Italy)

UPENETAdvisory Board

Hermann Engesser (Informatik-Spektrum, Germany and Switzerland)

Brian Runciman (ITNOW, United Kingdom)

Franco Filippazzi (Mondo Digitale, Italy)

Lloren Pags-Casas (Novtica, Spain)

Veith Risak (OCG Journal, Austria)

Panicos Masouras (Pliroforiki, Cyprus)

Andrzej Marciniak (Pro Dialog, Poland)

Rafael Fernndez Calvo (Coordination)

English Language Editors: Mike Andersson, David Cash, Arthur

Cook, Tracey Darch, Laura Davies, Nick Dunn, Rodney Fennemore,

Hilary Green, Roger Harris, Jim Holder, Pat Moody, Brian Robson

Cover page designed by Concha Arias Prez

"Strategos" / ATI 2008

Layout Design: Franois Louis Nicolet

Composition: Jorge Llcer-Gil de Ramales

Editorial correspondence: Lloren Pags-Casas <pages@ati.es>

Advertising correspondence: <novatica@ati.es>

UPGRADENewslist available at

<http://www.upgrade-cepis.org/pages/editinfo.html#newslist>

Copyright

Novtica 2008 (for the monograph)

CEPIS 2008 (for the sections UPENET and CEPIS News)

All rights reserved under otherwise stated. Abstracting is permitted

with credit to the source. For copying, reprint, or republication per-

mission, contact the Editorial Team

The opinions expressed by the authors are their exclusive responsibility

ISSN 1684-5285

Monograph of next issue (April 2008)

"Model-Driven Software Development"

(The full schedule of UPGRADE is available at our website)

Vol. IX, issue No. 1, February 2008

2 Presentation. IT Governance: Fundamentals and Drivers Ddac

Lpez-Vias, Antonio Valle-Salas, Aleix Palau-Escursell, and

Willem-Joep Spauwen

5 This is NOT IT Governance Jan van Bon

14 ITIL V3: The Past and The Future. The Evolution Of Service Man-

agement Philosophy Troy DuMoulin

16 PMBOK and PRINCE 2 for the Management of ITIL Implementa-

tion Projects Grupo de Metodologas de Gestin de Proyectos of

the itSMF Spain under the coordination of Javier Garca-Arcal

23 Business Intelligence Governance, Closing the IT/Business Gap

Jorge Fernndez-Gonzlez

31 IT Project Portfolio Management: The Strategic Vision of IT Projects

Albert Cubeles-Mrquez

37 ISO20000 An Introduction Lynda Cooper

40 COBIT as a Tool for IT Governance: between Auditing and IT

Governance Juan-Ignacio Rouyet-Ruiz

44 Implementing IT Governance Ad@pting CobiT, ITIL and Val IT: A

Respectful Caricature Ricardo Bra-Menndez and Manuel Palao

Garca-Suelto

48 What Governance Isnt Rob England

52 From Pro Dialog (PTI-PIPS, Poland)

Software Engineering

A View on Aspect Oriented Programming Konrad Billewicz

57 CEPIS Working Groups

Authentication Approaches for Online Banking CEPIS Legal

and Security Special Interest Network

CEPIS NEWS

UPENET (UPGRADE European NETwork)

Monograph: IT Governance (publ i shed j oi nt l y wi t h Novt i ca*)

Guest Editors: Ddac Lpez-Vias, Antonio Valle-Salas, Aleix Palau-Escursell, and

Willem-Joep Spauwen

2 UPGRADE Vol. IX, No. 1, February 2008 Novtica

IT Governance

Presentation

IT Governance: Fundamentals and Drivers

Ddac Lpez-Vias, Antonio Valle-Salas, Aleix Palau-Escursell, and Willem-Joep Spauwen

The Guest Editors

Ddac Lpez-Vias is the Director of IT Services at the Girona

University (Universitat de Girona UdG-, Spain), Director of

ICT at the Science and Technology Park of the UdG, and

consultant at UOC (Universitat Oberta de Catalunya) for

postgraduate courses in technology services management. He is

a graduate in Computer Science from UPC (Universitat

Politcnica de Catalunya), holds a postgraduate degree in IT

Management from ICT (Institut Catal de Tecnologia), another

in Enterprise Information Management (Infonoma, UPF), and

an MBA from Las Heures (UB). Before working in university IT

services he was a systems engineer at Hewlett Packard and

IECISA. He has played an active role on various boards of

governors of the ATI (the Spanish Association of Computer

Technicians) and has collaborated with the COEIC (Collegi Ofi-

cial dEnginyeria en Informtica de Catalunya) serving on the

Deans Council. He has been president of ATI Catalunya since

J anuary 2005. <didac.lopez@ati.es>.

Antonio Valle-Salas is Project Manager at Abast Systems and is

a specialist consultant in ITSM (Information Technology Service

Management) and IT Governance. He graduated as a Technical

Engineer in Management Informatics from UPC (Universitat

Politcnica de Catalunya) and holds a number of methodology

certifications such as ITIL Service Manager from EXIN

(Examination Institute for Information Science), Certified

Information Systems Auditor (CISA) from ISACA, and COBIT

Based IT Governance Foundations from IT Governance Network,

plus more technical certifications in the HP Openview family of

management tools. He is a regular collaborator with itSMF (IT

Service Management Forum) Spain and its Catalan chapter, and

combines consulting and project implementation activities with

frequent collaborations in educational activities in a university

setting (such as UPC or the Universitat Pompeu Fabra) and in

In recent years there has been much talk about IT Gov-

ernance and the management of organizations in general,

which has captured the interest of all those involved in ICT

management.

After a number of decades during which ICT has been

applied in organizations in an non-harmonized manner, with

different aims in each organization, there was a growing

realization that, while such technologies should be at the

service of business, that is not always the case.

If we were talking about another functional area, such

as Human Resources or Accounting, rather than ICT, we

would take it for granted that the activities undertaken by

those departments were aligned with the goals of the or-

ganization they belonged to, and we would not feel the need,

although such a need may exist, to create reference models

and methodologies to ensure that they were aligned. How-

ever, in many organizations ICT is not adequately aligned

with the organizations goals, which may lead to project

deviations (negative return on investment, uncontrolled

expenses, etc.), or unmanaged risks. This is what has given

rise to the concept we know today as IT Governance.

Organizations may be thought of as a coordinated set of

the world of publishing in which he has collaborated on such

publications as IT Governance: a Pocket Guide, Metrics in IT

Service Organizations, Gestin de Servicios TI. Una introduccin

a ITIL, and the translations into Spanish of the booksITIL V2 Service

Support and ITIL V2 Service Delivery. <avalle@abast.es>.

Aleix Palau-Escursell is a partner and Commercial Director of

NETMIND, a company engaged in IT training, consultancy, and

management. Aleix holds a Higher Diploma in Management

Informatics, a Master in Sales Management from EADA, and a

Master in ICT Management from La Salle (Universitat Pompeu

Fabra). His entire professional career to date has been in NETMIND

where he has led the companys commercial expansion and

established it as one of the pioneers in the provision of training and

consultancy services for Project Management, ITIL, and ISO 20000.

In recent years he has played an active role in disseminating best

practices and methodologies for Project Management and IT Service

Management, collaborating with organizations such as PMI (Project

Management Institute), itSMF (IT Service Management Forum),

ATI, and La Salle, among others. <aleix@netmind.es>.

Willem-Joep Spauwen is a senior consultant at Quint Wellington

Redwood Iberia. He graduated in Business Administration at the

University of Groningen, Netherlands. He has specialized in ICT

Governance and added value provided by business management

and organization related Information Systems. His career began in

the IT Department of Royal Dutch Airlines KLM, where he played

an active role in the field of IT-Business alignment. At Quint

Wellington Redwood he works as an international consultant in the

field of IT management. He has taken part in several projects

undertaken by multinationals in the Netherlands, the USA, Mexico,

and Spain. He also participates regularly in a number of international

forums. <w.j.spauwen@quintgroup.com>.

UPGRADE Vol. IX, No. 1, February 2008 3

Novtica

IT Governance

information systems in which human and material resources

participate, but the key to successful organizations resides

in the information per se and the way it is automated. Here

is where the managers of organizations may question the

manner in which that information is processed and the risks

they are taking, both as a result of mistakes that may be

made and in terms of the cost of not having that informa-

tion.

Meanwhile, the strategic opportunities afforded to or-

ganizations by ICT have given rise to difficulties concern-

ing the management of those technologies. Many compa-

nies do not hesitate to describe their ICT departments as

strategic or critical to their core activities while at the same

time recognizing that ICT causes problems that they hesi-

tate to describe as unmanageable.

Thus ICT departments are often perceived as a pure ex-

pense rather than a value-adding resource. They are seldom

considered as an opportunity, and investment in ICT is of-

ten seen as a technologists whim, always to be questioned.

Part of the problem lies in the difficulty that managers

have in seeing ICT in the company as part of their responsi-

bility and in acquiring the basic knowledge required to take

on that responsibility. But the CIOs are also to blame for

not understanding organizations and their business objec-

tives, for not taking managerial language on board, for not

listening to the real problems of functional managers, and

for focusing their goals on technology and not on the prac-

tical exploitation of that technology.

We can sum up this general problem as being a diffi-

culty to integrate and align ICT departments operations and

internal organization within the greater organization and its

technological goals. The problem also stems from the mis-

conception that general managers have of ICT departments

as separate and almost unrelated units due to the techno-

logical nature of their role.

Companies and organizations in general need to close

this gap between general management and ICT departments

by applying management methodologies that will integrate

ICT departments within the greater organization and align

their operations with corporate goals.

If this gap is to be closed, the managers of organizations

need to understand that the ICT department must be man-

aged within the context of business objectives as an insepa-

rable part of the business, and that they need to learn ICT

management methodologies. Meanwhile the managers of

the ICT department should understand their mission within

the context of the companys corporate goals. ICT manage-

ment should not be seen as a separate goal or discipline, but

rather as a cross-functional process affecting the entire or-

ganization, one in which everyone should play an active

role.

Many organizations are now getting the most out of ICT

by understanding and managing the benefits and risks in-

volved, by successfully aligning their ICT strategy with

corporate strategy to form a single integrated strategy, by

putting in place mechanisms and processes to implement

that strategy, including mechanisms to monitor and control

ICT systems, and by using metrics to measure ICT manage-

ment performance. The set of methodologies that allows us

to achieve the above objectives is what we now call IT

Governance.

IT Governance draws on a number of different fields

(monitoring and control, audit, metrics, service management,

and quality management) to create models identified by such

trendy terms as ITIL, Cobit, Val IT, ISO 20.000, etc., and

their pertinent certifications. This same trend has also given

rise to a great deal of confusion and management by fad

with regard to the concepts involved.

The aim of the ensuing monograph is to bring readers

up to speed with the latest trends, to show how such trends

may be reasonably applied, and to try and explain just what

IT Governance is, and what it is not.

4 UPGRADE Vol. IX, No. 1, February 2008 Novtica

IT Governance

The following references, along with those included in

the articles this monograph consists of, will help our read-

ers to dig deeper into this field.

Books

Koen Brand, Harry Boonen. IT Governance based

on CobiT 4.0. A management guide. ITSM Library.

Van Haren Publishing, 2007. ISBN: 9087530218.

J an Van Bon et al. IT Service Management An

Introduction. Van Haren Publishing. ISBN:978908

7530518.

Office of Government Commerce. Best practice for

Service Support. ITIL the key to managing IT Serv-

ices. TSO Books, 2001. ISBN: 9780113300150 /

0113300158.

Office of Government Commerce. Best practice for

Service Delivery. ITIL the key to managing IT Serv-

ices. TSO Books, 2001. ISBN: 9780113300174 /

0113300174.

Office of Government Commerce. ITIL Small-scale

Implementation. TSO Books, 2005. ISBN: 978011

3309801/0113309805.

Mark D. Lutchen. Managing IT as a Business: A Sur-

vival Guide for CEOs. McGraw-Hill, 2006. ISBN:

0471471046.

Gary Case, Troy DuMoulin, George Spalding, Anil C.

Dissanayake. Service Management Strategies that Work.

Van Haren Publishing, 2007. ISBN: 9789087530488.

Peter Brooks. Metrics for IT Service Management. Van

Haren Publishing, 2006. ISBN: 9789077212691.

IT Governance Institute. IT Governance Implemen-

tation Guide: Using COBIT and Val IT. 2nd Edi-

tion. ISACA, 2007. ISBN: 9781933284750.

IT Governance Institute. Cobit 4.1. ISACA, 2007.

ISBN: 9781933284729.

Office of Government Commerce. ITIL Version 3

Core Titles: The Official Introduction to the ITIL

Service Lifecycle; Continual Service Improvement

(CSI); Service Design (SD); Service Operation

(SO); Service Strategy (SS); Service Transition (ST).

<http://www.itsmf.es/books.asp?Class=3411>.

Useful References on IT Governance

Associations

IT Governance Institute <http://www.itgi.org>.

Information Systems Audit and Control Association

<http://www.isaca.org>.

IT Infrastructure Library <http://www.itil.co.uk>.

Information Technology Service Management Forum

<http://www.itsmf.es>.

ITSM Portal <http://en.itsmportal.net>.

Articles

ISACA. Val IT Overview <http://www.isaca.org/Template.

cfm?Section=Home&CONTENTID=21569& SECTION=

COBIT6&TEMPLATE=/ContentManagement/Content

Display.cfm>.

Mark Toomey. AS8015 Corporate Governance of

ICT Practical Application <http://www.usq.edu.au/

resources/as8015corporategovernanceofict.pdf>.

Pink Elephant. ITIL v3: What You Need To Know

<https://www.pinkelephant.com/NR/rdonlyres/

94D620D8-0351-4F9E-82D8-CF033200E8DA/

765/ITILv3WhatYouNeedToKnowNA1.pdf>.

ITIL.org. ITIL V3-V2 Mapping <http://www.itil. org/en/

itilv3-servicelifecycle/itilv3-v2mapping.php>.

Web Sites

The Val IT framework <http://itgovernance.pbwiki.

com/ValIT>, <http://www.isaca.org/valit/>.

COBIT 4.1 news <http://www.isaca.org/cobit>.

Enabling IT Governance <http://erp4it.typepad.com/

erp4it>.

History of I TI L <http://www.itilv3launch.com/

pages/index.html>.

ITSMWatch <http://www.itsmwatch.com>.

ITIL Training Zone <http://www.itiltrainingzone.com>.

Troy DuMoulins blog <http://blogs.pinkelephant.com/

troy>.

The IT Skeptic <http://www.itskeptic.org>.

Serge Thorns blog <http://sergethorn. blogspot.com>.

ICT Governance <http://www.gobiernotic.es>(in Span-

ish).

UPGRADE Vol. IX, No. 1, February 2008 5

Novtica

IT Governance

Keywords: Decision Making, Executive, Frameworks,

Information Management, IT, ITIL, IT Governance, Man-

agement, Model Enhanced, Organization, Planning and

Control, Strategic Alignment.

1 Introduction

IT Governance is important to CEOs and to CIOs -

but what is it, and what is it NOT? This article provides

some insight into that question, using a number of mod-

ern management frameworks

2 What is IT Governance about?

With the ever growing role of information in the Busi-

ness, it is hard to deny that this world has become totally

dependent upon information management. Many organiza-

tions wouldnt even survive for more than a few days if

their information systems would discontinue. This is the

first and main reason for the existence of IT Governance;

you need to be in control of your information supporting

systems. But there are other significant reasons as well.

First of all: organizations need to make sure they com-

ply to external regulatory requirements. We all know the

examples of what happens if this is not taken care of. Enron

and Worldcom have shown the consequences of bad gov-

ernance and each country will have had its own local finan-

cial disasters as well. Sarbanes-Oxley

1

, Basel II

2

, IFRS

3

,

and many local regulations were the answer to this. All these

regulations are aimed at ensuring that organizations are in

control of decision making processes and have transparent

administrations.

A second crucial sponsor of IT Governance is the fact

that organizations are more and more managed from the

perspective of the shareholder and other stakeholders. Or-

ganizations need to provide added value in terms of finan-

cial revenues or other values. Hedge funds are taking over

many companies and splitting them up for better financial re-

turns. Individual shareholders are getting organized and their

influence is growing. Other stakeholders like employees and

society are gaining recognition and extending their influence

on the decisions and performance of an organization.

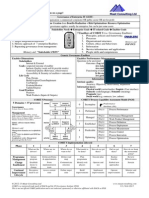

These aspects illustrate some of the core elements of a

generally accepted view on corporate governance, as illus-

trated in the CIMA (Chartered Institute of Management

Accountants) Enterprise Governance Framework (see Fig-

ure 1). This framework emphasizes the role of two key is-

sues in governance: "Conformance" and "Performance".

This is NOT IT Governance

Jan van Bon

IT is a business like any other line of business, so why dont we run it as a business? If we look at other disciplines, we can find

excellent examples of the application of governance principles. In the IT market, however, we seem to have forgotten to apply

some of the most elementary business policies. Recent developments have shown the catastrophical effects that may follow from

this. So lets have a closer look at this, and take the first elementary step by answering What is IT Governance and what is it

NOT? The answer may come as a surprise. And IT Governance may be less difficult than it seemed.

Author

Jan van Bon (Inform-IT.org) has been involved with the

development and publication of a large number of I T

Management frameworks. After a decade of academic research

he started his work in IT in the late 1980s, in the Netherlands.

He launched the Dutch itSMF (IT Service Management Forum)

in 1994 and was involved in itSMF projects ever since. He has

produced more than 50 books, in 14 languages, with expert

authors from all over the world, on a broad range of IT

management topics <j.van.bon@bhvb.nl>.

Figure 1: The CIMA Enterprise Governance Framework.

1

"The Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 is a United States federal

law enacted on J uly 30, 2002 in response to a number of major

corporate and accounting scandals including those affecting

Enron, Tyco International, Adelphia, Peregrine Systems and

WorldCom". <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sarbanes-oxley>.

2

"Basel II is the second of the Basel Accords, which are recom-

mendations on banking laws and regulations issued by the Basel

Committee on Banking Supervision. The purpose of Basel II, which

was initially published in J une 2004, is to create an international

standard that banking regulators can use when creating regula-

tions about how much capital banks need to put aside to guard

against the types of financial and operational risks banks face"

<http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Basel_ii>.

3

"International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) are stand-

ards and interpretations adopted by the International Accounting

Standards Board (IASB)" <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ifrs>.

6 UPGRADE Vol. IX, No. 1, February 2008 Novtica

IT Governance

Table 1: Some Definitions of IT Governance (based on [1]).

3 Definition(s) of IT Governance

A Google search for the meaning of IT Governance will

easily show over 50 different definitions. There still is no

single authorative source that has gained the power to set

any of these as the universal and official definition. Table1

presents some of the most familiar definitions.

Lately, experts in the field show some convergence towards

common elements in the definitions they use. Key elements in

the governance definitions are the organization and the distri-

bution of rights. Governance tends to deal with organizational

elements that are accountable for decision making, in a trans-

parent way. This immediately points out the second important

element, which always is about decisions.

However, governance is mostly restricted to only pro-

viding the infrastructure for making these decisions, and

the decision making process itself is not included. Making

decisions is generally accepted to be an aspect of manage-

ment, which is separated from governance. Sohal and

Fitzpatrick [2] have illustrated that in their research on gov-

ernance in Australian government (see Figure 2).

So there is a clear distinction between governance and

management, suggesting that governance enables the crea-

tion of a setting in which others can manage their tasks ef-

fectively. Which makes IT Governance and IT Management

two separated entities. Although many frameworks such as

COBIT (Control Objectives for Information and related

Technology) and ITIL (Information Technology Infrastruc-

ture Library) are characterized as "IT Governance frame-

works", most of them are in fact management frameworks.

4 What Is Not IT Governance

To be able to understand what IT Governance is all about,

Researchers IT Governance Definition

Brown and

Magill

(1994)

IT governance describes the locus of responsibility for IT functions.

Luftman

(1996)

IT governance is the degree to which the authority for making IT

decisions is defined and shared among management, and the

processes managers in both IT and Business organizations apply in

setting IT priorities and the allocation of IT resources.

Sambamurthy

and Zmud (1999)

IT governance refers to the patterns of authority for key IT activities.

Van Grembergen

(2002)

IT governance is the organizational capacity by the board, executive

management and IT management to control the formulation and

implementation of IT strategy and in this way ensure the fusion of

Business and IT.

Weill and Vitale

(2002)

IT governance describes a firms overall process for sharing decision

rights about IT and monitoring the performance of IT investments.

Schwarz and

Hirschheim

(2003)

IT governance consists of IT-related structures or architectures (and

associated authority patterns), implemented to successfully

accomplish (IT-imperative) activities in response to an enterprises

environment and strategic imperatives.

IT Governance

Institute

(2004)

IT governance is the responsibility of the board of directors and

executive management. It is an integral part of enterprise governance

and consists of the leadership and organizational structures and

processes that ensure that the organizations IT sustains and extends

the organizations strategies and objectives.

Weill and Ross

(2004) [5]

IT governance is specifying the decision rights and accountability

framework to encourage desirable behavior in using IT.

AS8015:2005

The system by which the current and future use of ICT is directed

and controlled. It involves evaluating and directing the plans for the

use of ICT to support the organisation and monitoring this use to

achieve plans. It includes the strategy and policies for using ICT

within an organisation.

UPGRADE Vol. IX, No. 1, February 2008 7

Novtica

IT Governance

Figure 2: IT Governance versus IT Management (Sohal & Fitzpatrick [2]).

it would be very helpful to understand what it is not. E.g.,

as we saw in the previous paragraph, management is not

governance. To be able to understand what is excluded from

the field of IT Governance, it therefore is useful to under-

stand what IT Management is.

We are discussing IT Governance and not corporate

governance, which automatically means that we have to

involve the discipline of Information Support in this. Infor-

mation Support is widely recognized as a supporting disci-

pline for the other Business processes.

The best way to manage a domain properly, according

to the principle of Separation of Concerns, is by dividing

that domain into a control subdomain and a realization

subdomain. That way, the realization domain does not con-

trol itself. Once applied to Information Support, this pro-

vides us with two separate responsibility domains: Infor-

mation Management (IM), where information support sys-

tems are designed and controlled, and Information Tech-

nology (IT), where the information systems are built and

run (see Figure 3).

Two opposite forces make this interactive system work:

1) Pull. The organization controls the quality of the In-

formation Support, based upon requirements that follow

directly from the information demand of the primary Busi-

ness activities. In addition, other supporting (Business) ac-

tivities also influence the demand for information. The IM

domain acts as the next link in the chain from the Business

domain perspective.

2) Push. Based on both possibilities and impossibilities,

and problems from the IT domain, the organization adjusts

the set-up of the Information Support.

Another widely used management paradigm (Planning

and Control) explains that in each domain we should al-

ways have Strategic, Tactical and Operational levels of

management (see Figure 4).

This also supports an interactive system based upon two

opposite forces:

1) Pull (top-down). Strategic plans and goals are speci-

fied at a tactical level and realized at an operational level.

But plans and goals can be adjusted, market forces can re-

quire adjustments, new partnerships can lead to new goals,

new ruling can require new preconditions, and each of these

will have its effect downstream towards the operational level.

2) Push (bottom-up). The organization adjusts objectives

and goals by evaluating the realization processes, adding op-

erational experiences to the decision processes. Again this will

show both the new possibilities as well as the impossibilities

and problems that an organization will run into.

Combining the views described above results in a 3x3

model for managing Business, Information and Technol-

ogy, as expressed in the SAME Model (see Figure 5).

The SAME model can be used as the "basic pattern" for

managing Information Support issues in organizations. It

still describes the responsibility and process elements, but

once we understand the structure of this 3x3 matrix, we can

use it to tackle organizational issues. Issues that can be ad-

dressed include:

The organization of the Information Support. This

deals with effectivity and efficiency:

- Setting up responsibilities, role descriptions and

RACI (Responsible, Accountable, Consulted, Informed)

matrices in the Information Management domain, and allo-

cating these to the various cells of the 3x3 matrix.

- Decisions on outsourcing of one or more activities

or functions, once they are understood and positioned in

the 3x3 matrix.

8 UPGRADE Vol. IX, No. 1, February 2008 Novtica

IT Governance

- Setting up the control organization for the management

of outsourced activities or functions, managing external sup-

pliers, setting up agreements, creating reporting policies.

- Auditing the organization.

Cross-references. Positioning and scoping of exist-

ing management frameworks, finding white spots in the

management system.

Process models. Allocating processes to specific man-

agement levels or domains, setting up process models based

on the given interactions between cells in the 3x3 model, com-

pleting process models based on the 3x3 model interactions.

Although the model can be used to tackle lots of man-

agement issues, it is quite useful as a base for discussing

governance issues. After all, if IT Governance is about the

organization of rights and decisions, we could now focus

on the allocation of these in the 3x3 matrix. The matrix pro-

vides us with a structured model of responsibilities and ac-

tivities. Allocating these to a specific organization actually

comes down to determining your IT Governance system.

Example 1: Organizing the IM Domain

Note that the dimension in the SAME Model is process

(managing Information Support activities, responsibilities,

tasks) and not organization. If we want to apply the com-

mon factors of the above definitions of IT Governance, we

will thus have to allocate the process domains of the SAME

Figure 3: Separation of Concerns in the Information Support Discipline (Van Bon & Hoving [3]).

Figure 4: The Planning and Control Paradigm for Strategy, Tactics and Operations (Van Bon & Hoving [3]).

UPGRADE Vol. IX, No. 1, February 2008 9

Novtica

IT Governance

model to an organizational structure. We can do this by tak-

ing the organizational dimension as an overlay over the proc-

ess dimension in the SAME model. And since organiza-

tions tend to differ in their organizational models, we can

find many different solutions for that. A few simple exam-

ples for the organizational allocation of Information Sup-

port responsibilities are described in Figure 6.

This highlights the question of where the responsibility

for IM and IT is positioned in the organization, which typi-

cally is an IT governance issue. Basically this comes down

to a question of where the IM domain is positioned:

a) Stuck-in-the-middle. IM is positioned at equal distance

from the Business and the IT domain, in many instances em-

blematic for organizations trying to implement IM as a liaison

function. The result is fairly often an IM function "stuck in the

middle": missionaries talking to a brick wall at the Business

side, renegades for the Technology side, and peacekeeping

troops in the middle, missing a clear identity in their own

mindset. In this scenario, IM will be an independent Demand

Organization, loosely coupled with the Business.

b) As an extension of the IT function. The IM respon-

sibilities of the organization have largely been delegated to

the Technology domain, where the IT services are produced.

Although still often found in practice, this approach is not

recommended: management tends to be expressing itself in

terms of technology, not in terms of Business values. And

the information service provider is now controlling itself,

which leaves the Business vulnerable in its relationships

Figure 5: The Strategic Alignment Model Enhanced (Van Bon & Hoving [3]).

Figure 6: The Position of the Information Management Domain, between Business and Information

Technology in the SAME Model (Akker [4]).

10 UPGRADE Vol. IX, No. 1, February 2008 Novtica

IT Governance

with suppliers. The organization has set IM at a distance,

making it highly vulnerable to misalignment between Tech-

nology and the Business.

c) As an extension of the Business function. Here,

information is considered to be a Business asset, and the

relationship with Technology can be a contractual one: IT

is a supportive function, to be managed as such, and con-

ceivably governed via outsourcing. Moreover, IM is a shared

Business responsibility, while IM as a separate function is

only accommodating and stimulating, but never leading. IM

and Business responsibilities are tightly bound and IT can

be regarded as a replaceable commodity, to be provided by

any adequate supplier.

Example 2: Service Contracting

If the Business wants to contract specific information

support, it will contract the IM domain for the provision of

information services. This agreement can be called an In-

formation Services Agreement (ISA).

The IM domain will then have to contract an IT service

providing function, to provide the technology elements of

the information services. That agreement will be between

IM and IT, and can be called an IT Services Agreement

(ITSA), also known as the Service Level Agreement (SLA)

in ITIL (see Figure 7).

Example 3: Organizing a Service Desk

The IM domain will have to provide operational support

for the user in the Business domain. This refers to the func-

tionality and the actual delivery of the agreed information serv-

ices and is aimed at supporting the use of these information

services by the Business. The IT domain will have to provide

Figure 7: Service Contracting in the SAME Model.

Figure 8: Example of an Integrated Service Desk, as an Organizational Layer over the SAME Framework.

UPGRADE Vol. IX, No. 1, February 2008 11

Novtica

IT Governance

the operational support for the user, under the control of the

IM domain, but the IM domain itself will have to provide the

support for functionality and specification issues.

For both types of support activities a Service Desk unit

may be installed. Instead of creating two separate Service

Desks, an organization may decide to create just one inte-

grated Service Desk (see Figure 8). This Integrated Service

Desk should then be prepared and educated to solve both

information issues as well as IT service issues.

Example 4: Position of Frameworks

An organization wants to use widely accepted frame-

works for its management approach. It already has ITIL V2

largely in place. The organization now considers the adop-

tion of ITIL V3, and wonders whether this will cover the

entire Information Support domain.

The answer is "no". Both ITIL V2 and V3 are largely

located in the Technology domain and cover only some

minor aspects of the IM domain. The organization will have

to adopt additional frameworks to cover the entire Informa-

tion Support domain (see Figure 9).

5 So What Is IT Governance

Based on the previous considerations, a recommendable

definition for IT Governance would be:

"IT Governance is the assigning of accountability and

responsibility and the design of the IT organization, aimed

at an efficient and effective use of IT within the Business

processes, and conforming to internal and external rules."

This definition is built on the following terms:

Accountability: the principle that individuals, organi-

sations and the community are responsible for their actions

Table 2: Examples of Organizational Decision Making Structures (based on [1]).

Decision Making Roles, Groups Description

Executive Board Decision making board of managers

Executive Manager Single decision making person

Business Board Decision making board of managers,

managing a single Business domain

Business Manager Single decision making person, managing

a single Business domain

Unit manager Single decision making person, managing

a single unit, e.g. of an expert domain

IT Board Decision making board of IT involved

managers, usually reinforced with experts

Committee Permanent decision making board of

experts, handling a single expertise,

knowledge domain, area, process of shared

interest

Advisory Board Delivery of input to support decision

making

Task force Temporarily decision making board of

experts, handling a single task usually of

shared interest

Chief Information Officer Highest ranking decision making manager

in the Information Support domain

IT Manager Highest ranking decision making manager

in the IT domain

Service Manager Decision making representative, managing

a service or service domain on behalf of

the IT department

Employee Empowered employee that is authorized to

take certain (usually process related)

decisions

12 UPGRADE Vol. IX, No. 1, February 2008 Novtica

IT Governance

and may be required to explain them to others.

Responsibility: to be entrusted with or assigned a

duty or charge.

Organizational design: the structure and relations

between departments, the grouping of tasks, and the flow

of work in organizations.

Business Processes: the workflows within a company

and the processes involved in inter-company transactions.

Rules: policies and principles guiding action.

And a recommendable definition of management would be:

"Management is making decisions within a set of as-

signed accountabilities and responsibilities and for a

clearly defined organizational area."

Allocating the responsibilities and rights to an organi-

zational management system, as explained in the above

examples, is typically the kind of issue that is handled in IT

Governance. Other issues that IT Governance is concerned

with could be:

Ensure authority and responsibility in IT: How

do I stay in control? Which (in)formal planning and report-

ing shall be required? Who shall determine budgets? Shall

we have a centralized or a distributed organization?

Ensure IT complies with regulatory authorities:

Which body shall consider the relevant and required regu-

lations and certifications? How shall risks be managed?

Ensure IT is organized and ready for change: How

shall the IM and the IT organizations be organized? Hierar-

chy, project-based, flat, team-based, etc? Which remunera-

tion policies shall be applied? Bonus rules, performance

related salaries, variable salaries, annual raise, etc? How

shall competences be managed and developed?

Ensure IT is aligned to fit Business/organizational

Figure 9: An Example of Positioning Management Frameworks in the SAME Framework.

Govern

Direct Monitor

Business

Pressure

Business

Needs

Plans

Pol ici es

Accountabi li ty

Responsibil ity

Performance of ICT

Conformance of ICT

Conformance Performance

IT Projects IT Operations

Business

IT

Govern

Direct Monitor

Business

Pressure

Business

Needs

Plans

Pol ici es

Accountabi li ty

Responsibil ity

Performance of ICT

Conformance of ICT

Conformance Performance

IT Projects IT Operations

Business

IT

Figure 10: AS8015, Corporate Governance of Information and Communication Technology.

UPGRADE Vol. IX, No. 1, February 2008 13

Novtica

IT Governance

needs: How shall an optimal fit between IT and Business

be realized? How do we deal with SLAs and service cata-

logues? Who decides on Service Levels?

Ensure IT delivers value for money: How shall

performance be measured? Shall IT performance be

benchmarked? Which cost model shall be applied?

IT Governance can also be concerned with issues like

Leadership, Culture, Risk management, Policies and pro-

cedures, Financial management, IT architecture, Procure-

ment and Sourcing.

6 The Organizational Aspects of IT Governance

If IT Governance is about organizing the decision mak-

ing structures, and the Information Support activities should

then be managed in these structures, the last question would

be: "what organizational structures could be applied in IT

Governance?"

These organizational structures can vary from organi-

zation to organization. Table 2 shows a number of possible

decision making roles or groups:

The elements from Table 2 can now be used to build an

organizations governance structure. A number of control

loops should then be designed to make sure that the frame-

work is a comprehensive system that controls itself. This

means that reporting mechanisms should be added, as well

as communication protocols, policies and standards. When

building this governance framework for your organization,

both aspects of good governance (conformance and per-

formance) should continually be addressed, to make sure

that the system will realize its primary goals. Once com-

pleted, the relevant regulations and standards can be used

to test the system and continual improvement programs can

be planned to enhance the organizations performance.

7 A Standard for IT Governance

As explained before, frameworks like COBIT and ITIL

are management frameworks, not IT Governance frame-

works. This also means that ISO/IEC 20000 also is a man-

agement standard and not a governance standard. There is

only one standard available for IT Governance, which is

the Australian standard AS8015 (see Figure 10). This stand-

ard is currently under investigation by the ISO organization

to see whether it can be adopted or embedded in the ISO/

IEC 20000 standard. If that would happen, the resulting

standard would be a mix of governance and management

elements.

The AS8015 indeed contains a number of control loops,

as required. It also emphasizes the basic structures of Con-

formance and Performance. However, it is short on specifi-

cations of the organizational issues that IT Governance

should be about, and instead it deals with quite a few

straightforward management issues.

8 Conclusion

IT Governance basically comes down to the question

"who rules what". Management should then work within

the agreed space. If Management does that correctly, this

will create the desired result: conformance to internal and

external regulations and standards, and optimized perform-

ance for adding value to the stakeholders of the organiza-

tion. The frameworks that are availlable to support this are

largely limited to the Management domain. Even the only

available local standard for IT Governance is largely deal-

ing with Management issues instead of IT Governance is-

sues. It may take a while before a true IT Governance frame-

work will become available.

References

[1] ITGA. Work from the IT Governance Association, The

Netherlands, not published, 2005.

[2] A.S. Sohal, P. Fitzpatrick. IT governance and manage-

ment in large Australian organizations. International

J ournal of Production Economics, 75, 94-112, 2002.

[3] J . van Bon, W. Hoving. Strategic Alignment Model En-

hanced. BHVB white paper, 2007.

[4] R. Akker. In J . van Bon (ed.). Frameworks for IT Man-

agement, Van Haren Publishing for itSMF, 2006.

[5] P. Weill, J . Ross. IT Governance: How Top Performers

Manage IT for Superior Results, Harvard Business

School Press, 2004. ISBN: 1591392535.

14 UPGRADE Vol. IX, No. 1, February 2008 Novtica

IT Governance

ITIL V3: The Past and The Future.

The Evolution Of Service Management Philosophy

Troy DuMoulin

Although the contribution made to ITIL (Information Technology Infrastructure Library) by version 3 over version 2

cannot be considered as a radical change in direction, it does represent a step forward towards making ITIL not only a

frame of reference for operational matters but also a valuable IT Governance tool. Rather than rendering the previous

recommendations obsolete, the new version places them within a broader context. This article stresses the importance of

this step forward and describes its most significant implications.

Keywords: Governance, ITIL, Process Integration,

Product Lifecycle, Value Chain.

1 Introduction

It has often been said that the only constant is change!

In the dynamic world we live in, this is true of all organic

things and ITIL(Information Technology Infrastructure

Library) is no different. From its humble beginnings as an

internal UK government initiative, to its growth and adop-

tion as a global best practice and standard for Service Man-

agement, ITIL has taken many steps along the road of

progress and maturity.

The ITIL Refresh Publications & Newsletters published

by the TSO (The Stationery Office) have given us some

interesting insight into the future of IT Service Manage-

ment (ITSM) as documented by ITIL. You will find links to

these documents on Pink Elephants ITIL v3 - Information

Central webpage <https://www.pinkelephant.com/en-GB/>.

It is my view that ITIL v3 is definitely taking a major

step in the right direction. We can observe a glimpse of this

from Table 1 that was published as part of the ITIL Refresh

Newsletter, 1st Edition, Autumn 2006. I would like to call

your attention to that table.

2 Key Evolutions in ITSM

From Table 1, we can identify and interpret some key

evolutions in ITSM Philosophy.

2.1 Alignment vs. Integration

For many years, we have been discussing the topic of

how to align Business and IT objectives. We have done this

from the assumption that while they (business and IT) shared

the same corporate brand, they were somehow two sepa-

rate and very distinct functions.

However, when does the line between the business proc-

ess and its supporting technology begin to fade to a point

where there is no longer a true ability to separate or revert

back to manual options? If you consider banking as an ex-

ample, Financial Management business processes and their

supporting technologies are now so inter-dependent that they

are inseparable. It is due to this growing realization that the

term alignment is being replaced with the concept of inte-

gration.

2.2 Value Chain Management vs. Value Service

Network Integration

When reading ITIL v2, you get the perception that the

business and IT relationship is primarily about a business

customer being supported by a single internal IT Service

Provider (Value Chain Management). Little acknowledge-

ment or guidance is provided about the reality of life never

being quite that simple. Todays business and IT relation-

ship for service provision is much more complicated and

complex than the concept of a single provider meeting all

business needs.

We need to consider that yes, there are internal IT func-

tions, but some are found within a business unit structure

where others are providing a shared service model to multi-

ple business units. Add to this the option of using different

external outsourcing options or leveraging software as a

service model and what you end up with is what ITIL v3

refers to as an Integrated Value Service Network.

Author

Troy DuMoulin is Director of Product Strategy and Executive

Consultant at Pink Elephant. He is an experienced Executive

Consultant with a solid and rich background in business process

re-engineering. Troy holds the Management Certificate in ITIL

and has extensive experience in leading Service Management

programs with a regional and global scope. His main focus at

Pink Elephant is to deliver strategic and tactical level consulting

services to clients based upon a demonstrated knowledge of

organizational transformation issues. Troy is a frequent speaker at

ITSM events and is a contributing Author for the ITIL "Planning

to Implement IT Service Management Book." He also works with

ISACA on COBIT v4 development <http://www.linkedin.com/

pub/0/235/148>.

UPGRADE Vol. IX, No. 1, February 2008 15

Novtica

IT Governance

2.3 Linear Service Catalogues vs. Dynamic Service

Portfolios

While ITIL has always been referred to as an IT Service

Management Framework, the primary focus up until now

has been on the ten Service Support and Delivery processes.

In previous versions of ITIL, the concept of a service has

almost been an afterthought or at least something you would

get to later. Consider that in ITIL v2 the process of Service

Level Management has, as one of its many deliverables, a

Service Catalogue which can be summarized from the theory

as a brochure of IT Services where IT publishes the serv-

ices it provides with their default characteristics and at-

tributes or Linear Service Catalogue.

In contrast to this, a Dynamic Service Portfolio can be

interpreted as the product of a strategic process where serv-

ice strategy and design conceive of and create services that

are built and transitioned into the production environment

based on business value. From this point, an actionable serv-

ice catalogue represents the published services and is the

starting point or basis for service operations and ongoing

business engagement. The services documented in this cata-

logue are bundled together into fit-for-purpose offerings

which are then subscribed to as a collection and consumed

by business units.

2.4 Collection Of Integrated Processes vs. Service

Management Lifecycle

Based on publicly available information, we know that

the ITIL v3 core books are structured around a Service

Lifecycle. This new structure organizes the processes we

understand from ITIL v2 with additional content and proc-

esses we are waiting to hear more about within the context

of the life span of IT Services. From this observation, we

can see that the primary focus is shifting from process to IT

Service. While processes are important, they are secondary

and only exist to plan for, deliver and support services. This

moves the importance and profile of the Service Catalogue

from being an accessory of the Service Level Management

process to being the corner stone of ITSM.

As organizations evolve from a technology focus to a

service orientation focus, these core changes to ITIL pro-

vide the context and ability to support this emerging reality.

Table 1: Key Evolutions in ITSM Philosophy.

ITIL v2 ITIL v3

Business & IT Alignment Business & IT Integration

Value Chain Management Value Service Network Integration

Linear Service Catalogues Dynamic Service Portfolios

Collection of Integrated Processes Service Management Lifecycle

2007. Pink Elephant. All rights reserved. ITILis a Regis-

tered Trade Mark and a Registered Community Trade Mark of the

Office of Government Commerce, and is Registered in the US Pat-

ent and Trademark Office.

16 UPGRADE Vol. IX, No. 1, February 2008 Novtica

IT Governance

PMBOK and PRINCE 2 for the Management of

ITIL Implementation Projects

Grupo de Metodologas de Gestin de Proyectos of the

itSMF Spain under the coordination of Javier Garca-Arcal

In this article we analyse a compilation of tools and techniques produced by a working group coordinated by itSMF Spain

with a view to providing professionals involved in projects implementing ITIL best practices with a range of project

management tools and techniques (based on PMBOK and PRINCE2 methodologies) to facilitate project management and

ensure a successful implementation of ITIL.

Keywords: Best Practices, CSF, Implementation, ITIL,

ITSMF, PMBOK, PRINCE2, Project Management, Success

Factor, Tools.

1 Introduction

The purpose of this article is to develop and dissemi-

nate tools that will ensure the successful execution of ITIL

implementation projects and help the parties involved meet

the challenge of implementing ITIL.

First we will give a brief explanation of the acronyms

used to refer to these methodologies:

ITIL (Information Technologies Infrastructure Library) is

a set of best practices for the administration and management

of IT services in terms of the people, processes and technol-

ogy employed, developed by the UK government agency, the

OGC (Office of Government Commerce). ITIL provides rec-

ommendations and guidelines for IT management aimed at

achieving alignment between technology and business.

The Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK)

is a compilation of knowledge acquired in project manage-

ment. It belongs to the PMI, Project Management Institute,

whose members are professionals from various fields, such as

law, finance, etc. The PMI encompasses both traditional and

more innovative practices.

PRINCE2, on the other hand, is a structured method of

project management which seeks to develop the organiza-

tion, administration, and control of projects based on project

management best practices.

In order to implement ITIL in an organization or depart-

ment we first need to make a study of potential advantages and

how those advantages can be gained by the end of the project.

The work performed by our group has resulted in an eminently

practical approach for ITIL implementation projects.

2 Work Methodology

A work methodology based on brainstorming was de-

signed and it was decided to apply decomposition techniques

to the analysis of information sources.

In addition to brainstorming, we used information from

PMBOK, PRINCE2, and the ITIL V2 and V3 books, as well

as the know-how of each member of the group.

In the first stage of the work we established the critical

success factors for an ITIL implementation, while in the

second stage we analysed each of the tools and techniques

proposed by PMBOK and PRINCE2 with a view to seeing

just how useful these tools and techniques were for imple-

menting ITIL. In the third stage of our work we considered

how to maximize the usefulness of the results for those in-

volved in ITIL implementations. It was decided to use a

graphical method based on hierarchical relationships simi-

lar to the one used by the metrics group of itSMF Spain [1].

3 Results

We go on to show some of the results obtained from this

study for both PMBOK and PRINCE2. We have explained

the methodology used to obtain results; now we will ex-

plain the content of each "tree" in which these results are

represented, and show how to use these trees to extract prac-

tical and useful information for the management of ITIL

implementation projects.

Authors

Grupo de Metodologas de Gestin de Proyectos (Project

Management Methodologies Group) of the itSMF (IT Service

Management Forum) is a multidisciplinary working group which

was convened following a directive from the standards

committee of itSMF Spain to create a line of research into project

management methodologies applied to the management of ITIL

implementation projects. It is coordinated by Javier Garca-Arcal.

Javier Garca-Arcal is a Doctor of Engineering by the Univer-

sidad Politcnica de Madrid. He works as a consulting mana-

ger at IT Deusto and as a lecturer in Project Management at the

Escuela Tcnica de Ingeniera Informtica and at the Escuela

de Ingeniera Tcnica Industrial of the Universidad Antonio de

Nebrija. He has collaborated in the review of the books ITIL V3

Service Operation and Fundamentos en ITIL V2. J avier has

pursued his career in process consulting, defining ITIL processes

for major multinationals in the Consulting, Retail, Telephony,

and Public Administrations sectors. He has worked in twelve

countries in IT Governance coordination, administration, and

project management, in software development in IT departments

of various consulting firms (Secuenzia, Citi Technologies, etc.),

and in service companies such as Sermicro, and multinationals

such as Chep and Telefnica I+D <javier.arcal@gmail.com>.

UPGRADE Vol. IX, No. 1, February 2008 17

Novtica

IT Governance

The analysis of the trees can be performed bottom-up,

from the tool to be used to the CSF (Critical Success Fac-

tor) on which it impacts, or top-down, from the CSF that

we want to improve/reach to the tools. The top-down method

will be used to give greater emphasis to the tools used and

to make it easier to trace the process through the tree. As we

can see, level 1 is the CSF itself which in turn is related to

all the PMBOK stages forming level 2 of the tree.

Each PMBOK stage has a number of activities which

may have or suffer from some degree of dependence with

the CSF which it is evaluating. Only those activities which,

in the course of our work, have been seen to contribute added

value in the achievement of the CSF in question will appear

on the tree. These activities comprise level 3 of the tree.

Finally, on level 4 will be all the tools, techniques, inputs

and/or outputs related to a PMBOK activity which is useful

to the CSF and may also contribute to the success of the

CSF.

Figure 1: Tree for PMBOK-CSF 10 Having the necessary resources and budget.

Figure 2: RACI Matrix.

18 UPGRADE Vol. IX, No. 1, February 2008 Novtica

IT Governance

Figure 3: Work Breakdown Structure.

Figure 4: Pareto Diagram.

Therefore, if we wish a certain CSF to be achieved, we

can use the tools that figure in the tree, concentrating on

those that are easier to use in our project or those that most

benefit our project.

If we apply this analysis to CSF 10, "Having the neces-

sary resources and budget", the purpose of which is to en-

sure that the team carrying out the project has all the re-

sources necessary to complete it successfully, we get the

tree shown in Figure 1. To achieve this CSF the following

tools can be used, among others: RACI, WBS, and Pareto

diagrams.

The horizontal rows of the RACI matrix set out in Fig-

ure 2 show project activities while the vertical columns rep-

resent all the people involved in the project. The idea is to

obtain detailed knowledge of each persons degree of in-

volvement in each activity and this is done by assigning

each person a role in each task he or she is involved in. The

roles defined for a RACI matrix are:

The WBS or Work Breakdown Structure shows how

project outcomes are subdivided into work packages (see

Figure 3). This representation provides us with a clear idea

of what outcomes the project will produce.

The last tool that can be used to achieve this CSF is the

Pareto Diagram, which is designed to show any defects that

have been produced by grouping them together according to

their origin/cause (see Figure 4). This technique allows us to

identify potential deviations in the success of the project be-

fore they occur, or as soon as possible after they appear.

UPGRADE Vol. IX, No. 1, February 2008 19

Novtica

IT Governance

Figure 5: Tree for PMBOK-CSF 5 Project closeout and transfer.

Figure 6: RBS, Risk Breakdown Structure.

20 UPGRADE Vol. IX, No. 1, February 2008 Novtica

IT Governance

Figure 7: Diagram SWOT.

In Figure 5 shows the tree for the PMBOK correspond-

ing to CSF5, "Project closeout and transfer", which is about

closing the project in the best possible manner. To increase

the effectiveness of this CSF the following tools can be used,

among others: Communications Management Plan, RBS,

SWOT, and even the Pareto diagrams mentioned earlier.

The Communications Management Plan contains all

the information deemed necessary to ensure that the project

stakeholders can perform their functions efficiently. This

information includes: distribution frequency, format, respon-

sibility, purpose of information, etc. Meanwhile RBS (Risk

Breakdown Structure), an example of which can be seen in

Figure 6, is a hierarchical description of project risks of the

project, identified and organized by risk category and

subcategory, which pinpoints various areas of risk and po-

tential causes.

The SWOT (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and

Threats) diagram helps us analyse these factors by provid-

ing the answers to the questions posed in Figure 7.

We go on to describe two CSFs and how they relate to

Figure 8. Tree for PRINCE2-CSF 2 Highlight, communicate and maintaining business alignment.

UPGRADE Vol. IX, No. 1, February 2008 21

Novtica

IT Governance

Figure 9: Gantt Diagram.

PRINCE2 methodology.

Figure 8 shows the tree for PRINCE2 corresponding to

CSF 2, "Highlight, communicate and maintaining business

alignment", which is about adopting a number of measures

to deliver value to business through ITIL implementation.

This tree focuses on the following tools/techniques: Project

Initiation Document or PID, Gantt diagrams, baseline, les-

sons learned file, and configuration item report.

The Project Initiation Document, or PID, establishes

the reference terms of the project, project role definitions,

and a communication plan in order to ensure that the ap-

proach, work plan, functions, and scope are clear. A well

put together PID lends visibility to the project while main-

taining business alignment.

The Gantt diagram (seeFigure 9) is a graphical tool

for showing expected time dedication for the different tasks

or activities over a given total time period. In spite of the

fact that, in principle, a Gantt diagram does not show rela-

tionships between activities, the position of each task over

time makes it possible to identify these relationships and

interdependencies.

A baseline is a way to store project-related information

such as starting dates, costs or resources so as to be able to

compare interim adjustments with the initial schedule or

budget and so measure the degree of progress of the project.

The lessons learned file contains previous project man-

agement resolutions while configuration item reports keep

version control of the elements and processes being imple-

mented so as to be able to align them with business and

keep track of which versions are current.

Finally we will take a look at CSF 10, "Having the nec-

essary resources and budget" as it relates to PRINCE2 meth-

odology.

As can be seen in Figure 10, to achieve this CSF the

following tools may be used: business case, matrix role-

responsibility and matrix role-competency.

Business case consists of ensuring that there is an ap-

propriate balance between revenues and resource costs,

based on expected return on project parameters for each

company or entity. This will include the following content,

among other: information on revenues such as invoicing

and collection schedule, all sources of expected income,

etc., and information on costs; for example, contingency

risks, internal and external costs.

The purpose of the role-responsibility matrix is to en-

sure that the responsibilities and competencies needed for

the proper performance of each role in the project are ap-

propriately defined. In order to build this matrix we need a

general list of applicable roles, responsibilities for each role,

and competencies for each role. By using the matrix we can

obtain a detailed definition of responsibilities and compe-

tencies, with the expected degree of competency required

by each role, which provides the organization with a cata-

logue of the resources required by the project.

The role-competency matrix provides the organization

with information on project resource requirements in terms

of responsibilities and competencies, and on how appropri-

ate those resources are to the needs of the project. Based on

a project-specific role-responsibility matrix we can build

other matrices with the following information:

Role-candidate resource matrix, with the candi-

date resources for each role and a comparison of require-

ment compliance for each candidate.

Role-allocated resource matrix, containing the

name of the resource for each role and the degree of re-

quirement compliance for each role.

General gap between roles-responsibilities-com-

petencies and the baseline resource evolution plan.

4 Conclusions

In the journey from a theoretical model of ITIL best

practices to the proper integration of that model into the

processes and culture of the business organization, the

implementation stage is all important. This is why we need

project management to control and coordinate project ac-

tivities within the pre-established constraints of time, cost

and resources. We can consider each ITIL process as a

project or, conversely, all ITIL processes as a single project.

Our research into Critical Success Factors (CSF) for

ITIL implementation and how they relate to the processes

and tools of the two methodologies we have compared,

PRINCE2 and PMBOK, defines a number of specific proc-

esses and techniques in each methodology for the achieve-

ment of those CSF and, therefore, for the successful imple-

mentation of ITIL processes. An inappropriate approach to

project management is one of the main reasons for the fail-

ure of ITIL implementations in organizations.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Luis Morn, Mona Biegstraaten and

Marlon Molina (coordinators of the standards, marketing, and

publications committees of itSMF Spain) for their support and

encouragement during this work, and thanks also go to the

members of the Grupo de Metodologas de Gestin de

Proyectos (Project Management Methodologies Group):

Juan Carlos Vigo, ATI <juancarlosvigo@ati.es>.

Eduardo Prida, AUSAPE <eduardo.prida@ausape.es>.

22 UPGRADE Vol. IX, No. 1, February 2008 Novtica

IT Governance

David Aguilera, SERMICRO <d.aguilera@sermicro.com>.

Nicoletta Calamita, MORSE <Niccoletta.calamita@morse.com>.

Eva Linares Pileno, STERIA <eva-pilar.linares@steria.es>.

Rafael de la Torre, QINT <r.delatorre@quintgroup.com>.

Julio Cesar Alvarez, STERIA <julio-cesar.alvarez@steria.es>.

Ramn Batista Berroteran, SERMICRO <rjbatistab@gmail.com>.

Rafael Pastor, ACCENTURE

<rafael.pastor.exts@juntadeandalucia.es>.

Ins Lpez Alvarez, SERMICRO <ineslopezalvarez@gmail.com>.

Ana Rengel Baralo, IT DEUSTO <a.rengel@itdeusto.com>.

References

[1] A. Garca-Almuzara, J. Garca-Arcal, F. Alcedo. Estudios

de mtricas ITIL-COBIT para Gestin de Configuracin

y Gestin de Cambios. In: ITSMF. 1st Annual itSMF Spain

Congress, Madrid, November 26, 2006.

Bibliography

R. Bovee, M. Ruwaard. Operations Management, a new

process. Second edition, April 2004. Nederland.

Mansystems, 2004. 89 pages. ISBN 90-440-0201-5.

J. Garca-Arcal, O. Ruano, J.A. Maestro. "PRINCE2 vs.

PMBOK". In: Universidad Antonio Nebrija. LS5168

Gestin de Proyectos Tecnolgicos, Madrid, June 21,

2005.

IT Governance Institute. COBIT 4.1. Rolling Meadows,

USA: IT Governance Institute, 2007.196 pages. ISBN 1-

933284-72-2.

Office of Government Commerce. ITIL Service Deliv-

ery. 2nd Version. United Kingdom: The Stationery Of-

fice Books, 2001. 300 pages. ISBN 978-011-330017-4.

Office of Government Commerce. ITIL Service Support.

2nd Version. United Kingdom: The Stationery Office

Books, 2001. 300 pages. ISBN 978-011-330017-4.

Office of Government Commerce. Managing Successful

Projects with PRINCE2. 4th edition. United Kingdom:The

Stationery Office, 2005. 456 pages. ISBN 0113309465.

Project Management Institute. A Guide to the Project

Management Body of Knowledge (PMBoK Guide, 3rd

Edition). PMI, 2004. ISBN: 1-930699-50-6.

S. Taylor, D. Cannon, D. Whelldon. ITIL Service Opera-

tion. 3rd Version. United Kingdom: The Stationery Of-

fice, 2007. 263 pages. ISBN 978-0-11-331046-3.

S. Taylor, G. Case, G. Spalding. ITIL Continual Service

Improvement. 3rd. Version. United Kingdom: The Sta-

tionery Office Books, 2007. 221 pages. ISBN 978-0-11-

331049-4.

S. Taylor, S. Lacy, I. Macfarlane. ITIL Service Transi-

tion. 3rd. Version. United Kingdom: The Stationery Of-

fice Books, 2007. 261 pages. ISBN 978-0-11-331048-7.

S. Taylor, V. Lloyd, C. Rudd. ITIL Service Design. 3rd.

Version. United Kingdom: The Stationery Office Books,

2007. 334 pages. ISBN 978-0-11-331047-0.

S. Taylor, M. Lobal, M. Nieves. ITIL Service Strategy.

3rd. Version. United Kingdom: The Stationery Office

Books, 2007. 264 pages. ISBN 978-0-11-331045-6.

Figure 10: Tree for PRINCE2-CSF 10 Having the necessary resources and budget.

UPGRADE Vol. IX, No. 1, February 2008 23

Novtica

IT Governance

Business Intelligence Governance, Closing the IT/Business Gap

Jorge Fernndez-Gonzlez

The need of IT departments to create value for their organizations business has given rise to a large number of tools (IT

Governance), which to a greater or lesser extent have been closing the gap between IT and Business, but have failed when

applied to Business Intelligence systems. This article demonstrates the need to create a dedicated BI Governance struc-

ture over and above IT Governance, a structure based on agility, versatility, and human relations which is specifically

designed to provide information to decision makers.

Keywords: Business Intelligence, Decision-making, IT/

Business Gap, IT Governance, Value.

1 Introduction

When I was in my teens people used to ask me about

whether I intended to study "science" or "arts". The ques-

tion always irritated me, so I would put on my most serious

expression and answer that I did not understand the ques-

tion because the "love of knowledge" (i.e. philosophy) had

never made any such distinction. I am similarly irritated

when people ask me whether I am an IT or a business con-

sultant. Once again, I cannot see the difference.

In this article I will be looking into how we can govern

our decision-making support systems, and we will also see

how it is impossible to separate "Business" from "IT" in

this context.

2 Defining Concepts

Figure 1, adapted from Webb, Pollard & Ridley [2],

shows how the BI Governance concept has evolved.

BI Governance is rooted in corporate governance, which

established the first practices of strategic management, risk

management, performance management, plans and controls,

and in the strategic plans of information systems, while

Executive Information Systems (EIS) and Decision Sup-

port Systems provided the basis for the creation of Busi-

ness Intelligence as we know it today.

Controlling the organization and controlling informa-

tion systems are two sides of the same coin which converge

in BI Governance.

But before going on, we should first define the two key

areas of influence that converge to produce Business Intel-

ligence Governance: Business Intelligence, and IT Govern-

ance.